How we regulate radiological and civil nuclear safety in the UK (webpage)

Published 20 April 2021

Foreword

Following the discovery of ionising radiation[footnote 1], and its uses for industrial, research and medical purposes, the United Kingdom (UK) has had a long history of utilising its benefits and protecting against its potential harms. The UK was one of the first countries to develop a legislative framework for radiological safety[footnote 2], in the form of the Radioactive Substances Act 1948 which enabled arrangements to be put in place to control the use of radioactive substances and irradiation apparatus in medicine, industry and research and the transport of such substances and apparatus.

As a pioneer of nuclear technology, the UK opened the world’s first commercial nuclear power station at Calder Hall in 1956. The aftermath of a fire in 1957 in Pile 1 on what is now the Sellafield site led to the development of the UK’s first nuclear regulator, the Inspectorate of Nuclear Installations in the then Ministry of Power. Since the 1950s regulation has evolved, incorporating best practice domestically and internationally, and the UK now has a comprehensive regulatory framework for radiological and civil nuclear safety.

Our regulatory framework for radiological and civil nuclear safety comprises regulatory bodies across England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland (NI) and can be broken down into the following broad areas:

- occupational exposures

- civil nuclear safety

- public exposures and environmental protection

- medical and non-medical exposures

- consumer products and radiation

- transport of radioactive material (RAM)

- emergency preparedness and response (EP&R)

The UK government and the devolved administrations work together and with bodies including the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)[footnote 3], the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP)[footnote 4], the Western European Nuclear Regulators Association (WENRA)[footnote 5], the Heads of the European Radiological Protection Competent Authorities (HERCA)[footnote 6], and the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR)[footnote 7]. This enables us to share our regulatory experience and support the continuous development of international safety standards to help ensure we continue to implement good practice.

We also participate in the IAEA’s expert peer reviews, as well as providing our own experts for overseas missions. Additionally, we work closely with the Nuclear Energy Agency of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD-NEA)[footnote 8], and the Radioactive Substances Committee of the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (the OSPAR Convention)[footnote 9].

The UK left the European Union (EU) and the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom)[footnote 10] on 31st January 2020. We are committed to putting in place all the necessary measures to ensure that the UK can continue to operate as an independent and responsible nuclear State. Given the potential of the civil nuclear sector - the combination of its key role in meeting our net zero target and in providing low-carbon energy to Great Britain (GB), its specialist skills, and wider work with ionising radiation- there is strong mutual interest in ensuring that the UK and Euratom continue to work closely together in the future, for example through WENRA and HERCA, which include both EU and non-EU States.

The purpose of this document is to provide an overview of the UK’s existing regulatory framework for radiological and civil nuclear safety, including the relevant legislation. It also sets out how we maintain our framework for safety and demonstrate regulatory transparency. It does not, however, introduce any new policies, or make changes to existing ones. A summary of the UK’s policies on radiological and civil nuclear safety is set out in chapter 2.

We are publishing this document to provide those with an interest in how the UK regulates radiological and civil nuclear safety access to this information in one place.

This document was produced with input from the UK’s regulators and in close cooperation with the devolved administrations. Together we strive to ensure that the UK’s regulatory framework for radiological and civil nuclear safety is in line with international safety standards.

1. Introduction

This document sets out the UK’s legislative and regulatory approach for radiological and civil nuclear safety.[footnote 11] It is intended to provide a guide to the UK’s comprehensive safety framework in one place.

It should be noted that the regulatory regimes for some areas in the document overlap. For example, the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974 (HSWA74) applies to occupational exposures wherever they occur and includes occupational exposures that are linked to medical and environmental exposures as well as occupational exposures at nuclear sites. Further information on these areas is set out in chapters 6, 7 and 8.

All legislation referred to in this document relates to legislation in force at the time of publication, unless otherwise stated.

Devolution

Health, the environment, and EP&R are devolved matters in the UK.[footnote 12] As a result, there are separate regulatory bodies covering these areas in England, Scotland, Wales and NI and distinct regulations for protecting people and the environment from radioactive substances. Although health and safety is reserved in relation to GB, it is an area where NI has competence. Further details on each of these devolved matters are set out in chapters 5, 7, 8 and 11 respectively.

The UK’s framework is set by multiple government departments, the devolved administrations and regulatory bodies. This document outlines the responsibilities of the various departments and bodies involved across the UK. It was prepared working closely with all the departments, devolved administrations, and key regulatory and advisory bodies with an interest in those areas. A full list of contributing organisations is available at Annex D.

Scope of the document

The document covers the regulation of radiological and civil nuclear safety. It does not include the regulation of radioactive material used for defence purposes. The default position is that within the UK, the Ministry of Defence (MoD) is required to comply with all applicable health, safety and environmental protection legislation. Where defence and security activities conflict with legislative requirements the MoD has derogations, exemptions or disapplications from UK law[footnote 13], the MoD maintains departmental arrangements that produce outcomes that are – so far as reasonably practicable – at least as good as those required by UK legislation.

Chapter 2 provides a summary of the UK’s national policies for radiological and civil nuclear safety.

The UK’s approach to regulation is set out in chapter 3. This provides details of each of the following aspects:

- safety as a top priority;

- justification (the justification principle is covered in more detail in chapter 4);

- optimisation;

- limitation (dose limits);

- the graded approach;

- the goal setting approach;

- independence of regulatory decisions; and

- stakeholder engagement

Chapters 5 to 11 cover the following areas in more detail:

- occupational exposures;

- civil nuclear safety;

- medical and non-medical exposures;

- public exposures and protection of the environment;

- consumer products and radiation;

- transport of radioactive material (RAM); and

- EP&R.

Chapter 12 sets out how the UK maintains its framework for radiological and civil nuclear safety and ensures its approach remains consistent with international good practice.

Finally, chapter 13 shows how the UK maintains its regulatory transparency. This includes how regulators engage with stakeholders, including those that they regulate, the public and other interested parties.

2. Summary of UK policies on radiological and civil nuclear safety

Introduction

The UK has a well-established radiological and civil nuclear safety regime which demonstrates a long-term commitment to safety as a top priority. Its fundamental objective is to ensure an efficient and effective safety framework which protects the public and the environment from the harmful risks of ionising radiation.[footnote 1] The UK is committed to this objective, thereby avoiding undue burden on future generations whilst allowing the safe use of ionising radiation, the safe operation of the nuclear industry and managing the legacy of this work in accordance with the graded approach. Nuclear power also contributes to the government’s leadership on sustainable development and the UK’s 2050 net zero target.

Set out below are the key elements of the UK’s policy for radiological and nuclear safety:

Adherence to IAEA Fundamental Safety Principles

UK policy is consistent with the IAEA’s Fundamental Safety Objective and Fundamental Safety Principles. These set out the basis for requirements and measures for the protection of people and the environment against radiation risks and for the safety of facilities and activities that give rise to those risks. Further details on how the UK implements the Fundamental Safety Principles is set out in Annex A.

Signatory to international conventions

The UK is a signatory to a number of international conventions that place legally binding obligations on contracting parties to effectively manage their domestic safety regimes and some require peer review to maintain international accountability. The UK was an early sponsor[footnote 14] and signatory of the relevant international legal instruments relating to nuclear and radiological safety including:

- The Convention on Nuclear Safety (CNS)

- The Convention on Early Notification of a Nuclear Accident

- The Convention on Assistance in the Case of a Nuclear Accident or Radiological Emergency

- The Joint Convention on the Safety of Spent Fuel Management and on the Safety of Radioactive Waste Management (JoC)

These conventions provide an effective and credible legal framework agreed by the international community, which the UK values and has played a key part in formulating. The UK plays an active role in the CNS[footnote 15] and JoC[footnote 16] regular review meetings to support and facilitate enhancement of the international safety regime and works closely with other IAEA member states to ensure we learn from experiences and take advantage of good international practices.

Alignment with international safety standards

The UK is committed to maintaining high levels of safety and contributes its expertise to the development of relevant international safety standards. Safety standards developed by international bodies such as the IAEA and ICRP are widely regarded as international good practice. The UK actively contributes to these and adopts them into its laws, regulations, and guidance. In so doing, the UK continues to demonstrate full compliance with the obligations in the relevant Conventions. The UK recognises the IAEA’s safety standards as the primary standards that its safety framework is measured against and routinely welcomes IAEA peer review missions. This independent benchmarking ensures the UK benefits from sharing good practice and learning across IAEA member states, demonstrating our commitment to high safety standards. Further information on IAEA peer review missions is set out in chapter 12.

Commitment to maintaining a legal framework for safety

The UK has established a legal framework for safety that ensures all its regulators have sufficient financial and human resources to carry out their functions efficiently and effectively. Government departments and devolved administrations work with regulators to regularly review the UK’s legal framework to ensure that it is effective and fit for purpose. The legal framework also gives regulators legal powers to take enforcement action and bring employers back into compliance. Enforcement action is made public to support learning and transparency. Regulators work closely with employers by providing guidance to ensure compliance with relevant regulations.

Effective coordination

To provide effective coordination of safety policy across a diverse range of stakeholders, the UK’s government departments, devolved administrations and regulators routinely collaborate and share information and issues through the Radiological Safety Group (RSG) and other key coordination groups[footnote 17]. These forums support the consistent enforcement of the regulations where powers are devolved.

The RSG is chaired by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) and consists of senior officials from the appropriate departments and regulatory bodies. It is designed to enhance collaboration and sharing of best practice to support key safety requirements including:

- monitoring and raising issues related to social and economic developments and their impacts on effective regulation and the government to regulator interface;

- the promotion of credible leadership and management for safety, including safety culture. The UK recognises the importance of a strong safety culture [see Chapter 3]. All regulators require employers to implement management systems that give due priority to safety; and

- discussing legislative and policy proposals across the UK’s radiological and civil nuclear safety regime.

The RSG, and its sub-group the Radiological Safety Working Group, also consider how IAEA standards should be implemented into the UK’s framework.

Providing international leadership

The UK takes its leadership role in radiological and civil nuclear safety seriously through its engagement and participation in the relevant international fora and organisations (e.g. IAEA, ICRP, OECD-NEA, UNSCEAR, OSPAR and the World Health Organisation (WHO)[footnote 18]) that cover radiological and nuclear safety. As one of the main contributors to the IAEA, both financially and through expert support, the UK works closely with like-minded IAEA Member States and partners to support the continuous improvement of the global safety regime, therefore enhancing the UK’s domestic regulatory framework. The UK also proudly contributes towards achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals as the key framework that ensures our efforts are tailored to wider development needs.

Commitment to research and development

The UK is internationally recognised for its leadership in research and the excellence of its scientific institutions. The UK government has made ambitious provisions for research and development (R&D). In March 2020, the Chancellor announced a record increase in public investment in R&D, committing to reaching £22 billion per year by 2024 to 2025[footnote 19]. The UK’s Nuclear Sector Deal ensures that the UK’s nuclear sector remains cost competitive with other forms of low-carbon technologies. It sets out the government’s commitment to support the development of skills (the Nuclear Sector Skills Strategy) to support the sector and the UK’s commitment to investing in innovation. This includes £180 million for the Nuclear Innovation Programme (NIP)[footnote 20].

In November 2020, the Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution announced further investment in the next generation of nuclear technology. Subject to value-for-money and future spending rounds, this commits up to £385 million in an Advanced Nuclear Fund. This will enable investment of up to £215 million into Small Modular Reactors to develop a domestic smaller-scale power plant technology design that could potentially be built in factories and then assembled on site and will unlock up to £300 million private sector match-funding. The Plan also commits up to £170 million for a research and development programme on Advanced Modular Reactors. Further information on enabling the regulation of new technologies is available in chapter 12.

The UK’s Nuclear Innovation and Research Office (NIRO) is responsible for providing advice to government, industry and other bodies on R&D and innovation opportunities in the nuclear sector under the guidance of the Nuclear Innovation and Research Advisory Board (NIRAB).

3. The UK’s approach to regulation

Every day in the UK, radioactive materials are used in a diverse range of processes including in energy generation, industrial, medical and research applications. These range from nuclear power plants to radiological techniques in, for example, cancer treatment and dentistry. Our key aim is to ensure that the necessary measures are in place to ensure the safety of the public, and the protection of patients, those that work with radiation on a day-to-day basis, third parties affected by work carried out and the environment.

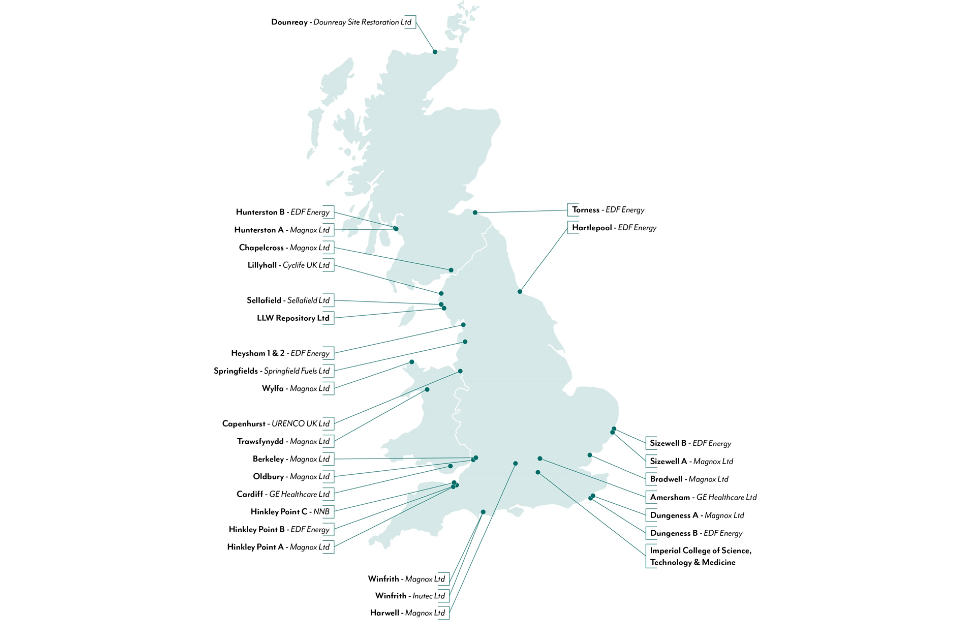

From the time that the UK started working with ionising radiation in an industrial and medical setting to the development of the first commercial power reactor in 1956, it has continued to develop and enhance its comprehensive legislative, regulatory and policy framework. This provides for the proportionate regulation of facilities and activities involving ionising radiation. The UK’s framework applies to 30 GB licensed civil nuclear sites[footnote 21] as set out in Annex C.[footnote 22] It also applies to thousands of employers working with ionising radiation, handling radioactive waste and the transport of radioactive material across the UK.

The UK’s approach incorporates the following aspects:

Safety as a top priority

For all uses of radioactive material the safety of the public, workers and patients is a top priority. This also applies to environmental protection, which provides protection to the public through the avoidance of environmental harm caused by radioactive material. The responsibility for radiological and nuclear safety rests with the employer. The UK legislative framework ensures that those who create the radiation risk must ensure that risks are removed or limited so far as reasonably practicable to ensure the safety of the public, patients and those who work with the radiation. This principle is enshrined in HSWA74 and the Health and Safety at Work (Northern Ireland) Order 1978 (HSW(NI)O78) and supports the development of a strong safety culture[footnote 23] across all sectors. The Act, the Order and the Ionising Radiations Regulations 2017 (IRR17) and the Ionising Radiations Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2017 (IRRNI17) that sit beneath them apply to all sectors. Protection of patients as a result of medical exposure is covered in more detail in chapter 7. Those that fail to meet their legal obligations in any sector may face enforcement action.

Justification

The IAEA Safety Fundamentals state that “Facilities and activities that give rise to radiation risks must yield an overall benefit.” In the UK, the justification process under the Justification of Practices Involving Ionising Radiation Regulations 2004 (JoPIIRR) (as amended[footnote 24]) requires that before any new class or type of practice involving ionising radiation can be introduced, the government must first assess it to determine whether the individual or societal benefit outweighs the health detriment it may cause. Further information on justification is set out in chapter 4.

Optimisation [footnote 25]

The optimisation principle requires that those who create the risk must demonstrate that they have done everything reasonably practicable to reduce it, balancing the level of risk posed by their activities against the cost and benefits of the measures needed to control that risk - whether in money, time or resources (or in the case of public exposures, the economic and societal benefits). Whilst the different regulatory regimes in the field of radiological protection in the UK use different terminology and have their own guidance on optimisation, they are all broadly equivalent.

These include reducing risks or exposure:

- as low as reasonably practicable (ALARP);

- so far as is reasonably practicable (SFAIRP)[footnote 26]; and

- as low as reasonably achievable (ALARA).

For environmental protection, employers demonstrate that exposures are ALARA through the use of best practicable means (BPM) and best practicable environment option (BPEO) in Scotland and NI; and in England and Wales, use of best available techniques (BAT), which is broadly equivalent to a combination of BPM and BPEO[footnote 27].

Limitation (dose limits and dose constraints)

A dose limit is the total radiation dose to an individual that must not be exceeded. Dose constraints are part of the system of radiological protection and are informed by a risk assessment. They are a tool to help restrict, as far as is reasonably practicable, an individual’s exposure to ionising radiation that might arise from a particular activity. These are especially useful at the planning stage and in relation to individuals who may be exposed to more than one source of radiation.

The IRR17 and IRRNI17 require that all employers must, in relation to any work with ionising radiation that they undertake, take all necessary steps to restrict radiation exposure so far as is reasonably practicable with an absolute duty not to exceed specified dose limits. Chapter 7 sets out further information on dose constraints in medical and non-medical exposures.

Graded approach

UK regulators take a graded approach when regulating. The use of a graded approach is intended to ensure that the necessary levels of analysis, documentation and actions are commensurate with, for example, the magnitudes of any radiological hazards and non-radiological hazards, the nature and the particular characteristics of a facility, and the stage in the lifetime of a facility.

Goal setting approach

In line with our wider approach to safety, the UK adopts an outcome-focussed, goal setting regime rather than the more prescriptive, standards-based regimes applied in some other countries. This means that UK regulations set out broad regulatory requirements, supported by relevant codes of practice and guidance, and it is for the employer to determine and justify how best to achieve them. This approach allows an employer to be innovative and to achieve the required high levels of radiological protection by adopting practices that meet its particular circumstances. It also encourages continuous improvement and the adoption of relevant good practices rather than simply meeting a prescribed standard.[footnote 28]

Independence of regulatory decisions

In line with international standards, UK regulatory bodies are set up to make independent, objective, regulatory decisions in line with applicable legislation and free from undue external influence e.g. from government and industry. Ministers can set direction, but they cannot overrule a regulatory decision.[footnote 29]

Stakeholder engagement

In the UK, regulators must pay careful attention to the Regulators’ Code, which provides a flexible, principles-based framework for regulatory delivery. This supports and enables regulators to design their service and enforcement policies in a manner that best suits the needs of businesses and other regulated entities. The Code states that “Regulators should have mechanisms in place to engage those that they regulate, the public and others to offer views and contribute to the development of their policies and service standards”. Further information on how regulatory bodies demonstrate compliance with the Regulators’ Code is available in chapter 13. Chapter 13 also includes detailed information on how regulators engage with other interested parties.

These aspects incorporate relevant international best practice and safety requirements that have been set by international organisations such as the IAEA. Chapter 12 sets out how the UK actively engages with the international community to support the development of robust safety standards.

4. The justification regime

As set out in chapter 3, the IAEA Safety Fundamentals state that “Facilities and activities that give rise to radiation risks must yield an overall benefit.” i.e. the justification principle. The JoPIIRR regulations, which apply across the UK, provide the regulatory framework for enabling the determination of whether an existing or proposed practice involving ionising radiation is justified. This takes into account the expected individual and societal benefits and the potential risks, including potential detriment to health. Only practices that are justified may be authorised by the regulatory bodies, such as the environmental regulators.

There are three ways in which activities that are the subject of these Regulations can be considered ‘existing’. These are listed in Annex 2 of the JoPIIRR guidance:

- If there is evidence to show that they were in existence prior to 13 May 2000 (the transposition deadline for the 1996 Basic Safety Standards Directive);

- Where a new class or type of practice is the subject of a positive justification decision, it becomes an existing class or type thereafter;

- For certain classes or types of practice that were only brought within the scope of JoPIIRR 2004 by the 2018 change to the definition of “practice”, the relevant date for distinguishing between new and existing classes or types of practice is 6 February 2018.

Anyone seeking to undertake a new type of practice must make an application for a justification decision. The Justifying Authority (the relevant Secretary of State (SoS), the Scottish ministers, NI ministers, or Welsh ministers as appropriate) will then make a decision regarding whether it is a justified practice.

As a result of transposition of the 2013 Euratom Basic Safety Standards Directive (BSSD13), the SoS making the justification decision under JoPIIRR cannot be the SoS proposing the activity. For example, the SoS for BEIS can no longer make the justification decision for new power reactors coming through the JoPIIRR process.

JoPIIRR covers a range of activities, some of which fall within devolved subject areas. However, to ensure consistency across the justification system, the UK government has to-date made single pieces of legislation covering all areas of the UK and all practices (including those that are devolved). The devolved administrations have to-date been content with that approach.

Classes and types of practice include nuclear reactor designs. Three of these, including the UK European Pressurised Water Reactor (EPR) currently under construction at Hinkley Point C, have been subject to regulatory justification decisions and have achieved a positive decision.

5. Occupational exposures

Ionising radiation is used throughout the UK in a diverse range of occupations including: industrial; medical and dental; veterinary; mining, drilling and quarrying; research; and non-destructive testing, as well as at licensed nuclear sites. These activities bring real benefits to people living and working in the UK, but it is vital that we have the necessary protections in place to ensure the safety of the public and those that work with radiation on a day-to-day basis.

Relevant legislation

HSWA74 and HSW(NI)O78 set the national framework for health and safety and apply to all employers in the UK. Failure to comply with the legislation and associated regulations can result in enforcement action being taken, including fines, imprisonment and disqualification of company directors.

Under HSWA74 and HSW(NI)O78 employers have a duty to ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, the health, safety and welfare at work of all their employees. The legislation also imposes a duty on every employer to conduct their undertaking in such a way as to ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, that those persons not in their employment who may be affected thereby are not exposed to risks to their health and safety.

The IRR17 regulations made under HSWA74, and IRRNI17 in NI, apply to all employers who work with ionising radiations. They also apply to work with naturally occurring radioactive materials, including work in which people are exposed to naturally occurring radon gas and its decay products (further information on this is provided in chapter 8).

Any employer who undertakes work with ionising radiation must comply with IRR17/IRRNI17, including the completion of a suitable and sufficient radiation risk assessment.[footnote 30] Employers are expected to regularly review their radiation risk assessments to ensure that this remains up-to-date and fit for purpose. Some examples of updates are a change of process, the introduction of a modified machine, or a revision required as the result of an accident that had occurred. Advice on how to comply with the regulations is included in an Approved Code of Practice (ACoP) and guidance.

Minimising exposure to ionising radiation

Regulations under HSWA74/HSW(NI)O78 and IRR17/IRRNI17 require employers to restrict exposure to ionising radiation so far as is reasonably practicable. Exposures must not exceed specified dose limits. Restriction of exposure should be achieved first by means of engineering control and design features. Where this is not reasonably practicable, employers should introduce safe systems of work and only rely on the provision of personal protective equipment as a last resort. Before commencing a new activity involving work with ionising radiation an employer must make a suitable and sufficient assessment of the risk to any employee and wider public and identify the measures needed to restrict exposure. Depending on the type of work involving ionising radiation (as specified in IRR17 and IRRNI17) and the location it is to be carried out, employers must either notify, register, or gain consent(s) from the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) for work on GB non-nuclear premises, the Health and Safety Executive Northern Ireland (HSENI) for work in NI, or the Office for Nuclear Regulation (the ONR) for work on nuclear licensed premises.

Under IRR17 and IRRNI17 and the Radiation (Emergency Preparedness and Public Information) Regulations 2019 (REPPIR19) or the Radiation (Emergency Preparedness and Public Information) Regulations (Northern Ireland) (REPPIRNI19), every employer engaged in work with ionising radiation must consult an appointed Radiation Protection Adviser (RPA), who will advise the employer on how to best comply with the regulations. The individual RPA or the RPA body[footnote 31] selected must meet the criteria of competence as set out in the HSE Statement on radiation protection advisers and must have the relevant experience to make them suitable to provide the advice needed.

Occupational exposure regulators and relevant government departments

Regulators

Enforcement of occupational health and safety legislation in GB is divided between the Health and Safety Executive (HSE), Local Authorities, the Office for Nuclear Regulation (the ONR) and the Office of Rail and Road (ORR)[footnote 32]. Regulation of work with ionising radiation is carried out by each of these regulatory bodies for those activities/premises for which they are the enforcing authority. For example, HSE is the enforcing authority for manufacturing activities and industrial radiography, Local Authorities (LAs) regulate X-ray machines located in warehouses or museums and ORR regulates within the rail industry. Detailed information on the ONR’s role is set out in Chapter 6.

In NI, the Health and Safety Executive Northern Ireland (HSENI) regulates occupational exposure and LAs have similar enforcing authority roles. HSE on request, can and do provide specialist health and safety support to HSENI, LAs and ORR, e.g. in support of investigations, which may include radiation.

Inspectors in all the above organisations carry out a range of functions including providing advice, review and assessment, inspection, investigation and enforcement in a proportionate way so that radiation exposure of employees and others, arising from work activities, is adequately controlled. Please refer to the Enforcement Policy Statement (EPS) and other relevant documentation, e.g. the Enforcement Management Model (EMM) for each regulatory body for more information.[footnote 33]

Government departments

The HSE is an executive non-departmental public body (NDPB)[footnote 34] of the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP). It devises its own policy and legislative proposals and reports directly to DWP ministers.[footnote 35]

HSENI is a non-departmental public body with crown status under the remit of the Department for the Economy.

6. Civil nuclear safety

The Office for Nuclear Regulation (the ONR) regulates nuclear safety at 30 licensed civil nuclear sites[footnote 36] in the UK, including the existing fleet of operating reactors and decommissioning power stations.[footnote 37] The UK currently has eight operating nuclear power stations, which consist of 14 Advanced Gas-cooled Reactors (AGR) and one Pressurised Water Reactor (PWR) contributing around 17% of the UK’s electricity generated in 2019. Alongside these nuclear sites, the UK has fuel cycle facilities and waste management and decommissioning sites.

While this chapter relates to civil nuclear sites, it should be noted that other areas of this document are also relevant to nuclear safety. For example, as set out in chapter 5 on occupational exposures, HSWA74 and IRR17 apply to nuclear sites, in addition to specific legislation governing nuclear safety at nuclear installations in England, Scotland and Wales.[footnote 38] Further information on the role of the environmental regulators on nuclear sites is available in chapter 8 (public exposures and protection of the environment).

Relevant legislation

The Nuclear Installations Act 1965 (NIA65) provides the legal framework for nuclear safety and nuclear third-party liability. The NIA65 sets out a system of regulatory control based on a robust licensing process administered by the regulator (the ONR). In addition to the nuclear site licensing regime, NIA65 requires that financial provision is in place to meet claims in the event of a nuclear incident, as required under international law on nuclear third-party liability.

NIA65 states that no site can be used for the purpose of installing or operating a nuclear installation (or other prescribed activities[footnote 39]) unless a nuclear site licence has been granted by the ONR and is currently in force. Only a corporate body, such as a registered company or a public body can hold a site licence and the licence is not transferable.

An important provision of NIA65 is that it requires the ONR to attach such conditions to a site licence as it considers necessary or desirable in the interests of safety and may attach such conditions to it at any other time. It is an offence under the law to not comply with a licence condition. There are 36 standard site licence conditions ranging from marking the site boundary to decommissioning. Licence holders must demonstrate compliance with the licence conditions in a manner appropriate to their particular operation, such as with a safety case to meet a stage in the plant’s life, or with arrangements and procedures to meet a licence condition.[footnote 40] The ONR ensures compliance with site licence conditions through a programme of inspections on site, and the licence conditions are supported by a framework of Safety Assessment Principles (SAPs), Technical Inspection Guides (TIGs) and Technical Assessment Guides (TAGs).

The NIA65 also allows the ONR to recover costs associated with licensing and enforcement of the licence conditions from licence holders.

The Nuclear Reactors (Environmental Impact Assessment for Decommissioning) Regulations 1999 (EIADR), as amended, require the potential environmental impacts of projects to decommission nuclear power stations and nuclear reactors (except research installations whose maximum power does not exceed 1 kilowatt continuous thermal load)[footnote 41] to be assessed before the ONR grants consent for the decommissioning project to commence. Decommissioning projects that commenced prior to the regulations coming into force in 1999, do not require retrospective consent.

However, for all decommissioning projects, regardless of when they started, any changes or extensions to the project which may have significant adverse effects on the environment cannot commence until the ONR has made a determination. This will determine whether the project shall be made subject to an environmental impact assessment, under Regulation 13 of the EIADR.

The EIADR require that the ONR consults the public and other relevant stakeholders, including the appropriate environmental regulator and the local highway and planning authorities, during the EIADR application process. This will take into account the environmental impacts of the options being considered for a proposed decommissioning project.

Nuclear safety regulators and relevant government departments

Regulators

The Office for Nuclear Regulation (the ONR), established by the Energy Act 2013 (TEA13), is the UK’s independent regulator for nuclear safety, security and conventional health and safety at nuclear sites and it is the enforcing body for all aspects of nuclear safety including emergency response. The ONR regulates nuclear safety at 30 licensed civil nuclear sites[footnote 42] in the UK including the existing fleet of operating reactors, fuel cycle facilities and nuclear installations undergoing decommissioning.[footnote 43]

The ONR seeks to maintain and, where appropriate, improve safety standards for work with ionising radiation at nuclear sites, through regulation of compliance with both relevant legislation and nuclear site licence conditions. It does so by using a range of approaches including on-site inspections and assessment of submissions by licensees. In addition, the ONR sets clear expectations in respect of the standards and outcomes expected. The ONR also contributes to the development of national and international radiological and nuclear safety standards and guidance in its work with, for example, the IAEA, OECD-NEA and WENRA.

It has a range of enforcement powers which arise from both the TEA13 and HSWA74. The ONR’s approach to enforcement decision making is set out in its Enforcement Policy Statement (EPS). This ranges from giving advice to instigating court proceedings (prosecution) or recommending proceedings in Scotland and is underpinned by its Enforcement Management Model (EMM).

It should be noted that for nuclear licensed sites in England and Wales (those which have / use nuclear matter) the accumulation and storage of radioactive waste is regulated by the ONR and disposal is regulated by the environmental regulators. The ONR works closely with the EA, NRW and the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA) at nuclear sites. Further information on this is set out in Chapter 8.

The ONR also regulates the transport of nuclear and radioactive materials within GB and works with the international inspectorates to ensure that the UK’s safeguard obligations are met. Further information on the transport of radioactive materials is available in chapter 10.

In addition, it works alongside the Environment Agency (EA) and Natural Resources Wales (NRW)[footnote 44] in a process called Generic Design Assessment (GDA). The objective for GDA is to provide confidence that the proposed design is capable of being constructed, operated and decommissioned in accordance with the standards of safety, security and environmental protection required in GB.

For the Requesting Party for a GDA, this offers a reduction in uncertainty and project risk regarding the design, safety, security and environmental protection cases, so as to be an enabler to future licensing, permitting, construction and regulatory activities.[footnote 45]

Government departments

The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) is responsible for ensuring that the ONR has access to the funds it needs to carry out its regulatory functions and purposes. DWP sponsorship of the ONR ensures the ONR’s functional separation from the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) which is responsible for establishing government policy in relation to the use of nuclear power, with BEIS ministers being responsible to Parliament for nuclear safety.[footnote 46]

7. Medical and non-medical exposures

Every day in the UK ionising radiation is used for the diagnosis and treatment of disease as well as for screening and research involving patients and individuals. This includes X-rays, radiotherapy and nuclear medicine. It is widely used in hospitals, dental surgeries, clinics and in research facilities such as universities and sports science institutes.

The UK’s regulatory framework also takes into account what are termed as non-medical exposures using medical radiological equipment. Exposures are undertaken using medical radiological equipment which do not confer a health benefit to the individual exposed, such as health assessments for employment purposes and identification of concealed objects within the body.

Devolution

Health is a devolved matter in the UK. This means that there are different medical and non-medical exposure regulators in England, Scotland, Wales and NI and separate regulations for protecting people against medical and non-medical exposures in GB and NI. Information on the relevant legislation and regulators is set out in this chapter.

Relevant legislation

Protection of patients, individuals and carers and comforters for medical and non-medical exposures are covered by the Ionising Radiation (Medical Exposure) Regulations 2017 (IR(ME)R) in GB and the Ionising Radiation (Medical Exposure) Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2018 in NI.

The regulations aim to make sure that ionising radiation is used safely to protect patients from the risk of harm when being exposed. They set out the responsibilities of employers for radiation protection and the basic safety standards that employers must meet.

Responsibilities include:

- minimising unintended, excessive or incorrect medical exposures;

- justifying each exposure to ensure the benefits outweigh the risks: and

- optimising diagnostic doses to keep them ’as low as reasonably practicable‘ for their intended use.

The regulations apply to both the independent and public sectors (the NHS).

Under IR(ME)R, employers who undertake medical and non-medical exposures must appoint a Medical Physics Expert (MPE)[footnote 47] for advice on complying with the regulations.

Optimisation

Dose limits are not applicable to IR(ME)R, but dose constraints must be established for medical or biomedical research programmes where no direct medical benefit to the individual is expected, and for carers and comforters. Dose constraints are restrictions set on prospective doses of individuals which may result from a given radiation source.

The regulations require that the doses arising from exposures are kept as low as reasonably practicable other than in radiotherapy. In radiotherapy, the dose to the tissue not being targeted must be kept as low as reasonably practicable.

Diagnostic reference levels

Diagnostic Reference Levels (DRLs) are radiation dose levels, or for nuclear medicine the administered activity, for typical diagnostic examinations on standard size adults and children for broadly defined types of equipment e.g. computerised tomography (CT) scans, fluoroscopy or general radiography. These levels should not be exceeded where good and normal practices exist but must be reviewed when consistently exceeded.

Quality assurance of equipment

The employer must establish a programme of quality assurance for the safe performance of radiological equipment used for medical and non-medical purposes. This includes frequency of testing and corrective actions required to improve inadequate or defective equipment.

Guidance

Guidance on compliance with IR(ME)R is produced by the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC). There is also guidance written and established by all regulatory bodies for health for statutory notifications of significant accidental and unintended exposures (SAUE). In addition, the Royal College of Radiologists has produced guidance relating to radiology and radiotherapy.

Public Health England (PHE)[footnote 48] and the medical societies have provided IR(ME)R guidance for diagnostic and radiotherapy exposures. Two documents, Ionising Radiation (Medical Exposure) Regulations: Implications for clinical practice in radiotherapy and Ionising Radiation (Medical Exposure) Regulations: Implications for clinical practice in diagnostic imaging, interventional radiology and diagnostic nuclear medicine explain how regulations should be interpreted in clinical practice. The latter document also extends to research laboratories, universities and sports facilities where medical and non-medical exposures are undertaken.

Medical and non-medical exposure regulators and relevant government departments

Regulators

The Care Quality Commission (CQC), established by the Health and Social Care Act 2008, is the ‘enforcing authority’ in England under HSWA74 in relation to the Ionising Radiation (Medical Exposure) Regulations 2017 (IR(ME)R). The CQC is an executive non-departmental public body[footnote 49]. CQC’s sponsoring government department is the Department for Health and Social Care.

The CQC regulates all health and social care services in England. Part of CQC’s role is to ensure that medical and non-medical use of ionising radiation is carried out in accordance with the regulations in order to minimise the risk to patients in hospitals, dentists, ambulances, and care homes.

In Wales, Welsh ministers have the function of ensuring compliance with IR(ME)R and this is exercised through Healthcare Inspectorate Wales (HIW), an operationally independent part of the Welsh Government.

Healthcare Improvement Scotland (HIS), established by the National Health Service (Scotland) Act 1978, has broad powers to inspect and monitor the quality of healthcare in the NHS and the independent sector. The Act allows Scottish ministers to delegate to HIS, by order, such of their functions relating to the health service as they consider appropriate, including ensuring compliance with IR(ME)R. Inspectors for IR(ME)R sit within HIS.

In NI, the Regulation and Quality Improvement Authority (RQIA) is the designated regulatory body for inspection and enforcement under the Ionising Radiation (Medical Exposure) Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2018. The RQIA is a non-departmental public body (NDPB) sponsored by the Northern Ireland Department of Health.

IR(ME)R provides relevant enforcement authorities with powers arising from the HSWA74 to enter premises, interview staff, and to access or obtain information for the purpose of checking compliance with the regulations, for investigating notifications of incidents relating to medical and non-medical ionising radiation, and to initiate enforcement action.

Government departments

The Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC) is a ministerial department, supported by 15 arm’s length bodies and a number of other agencies and public bodies. As part of its remit, it is responsible for radiological protection of those exposed to ionising radiation as part of their own medical diagnosis or treatment in England. DHSC is the sponsoring department for the CQC and Public Health England (PHE)[footnote 50] and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) who became the UK’s standalone medicines and medical devices regulator on 1 January 2021.

PHE is an executive agency[footnote 51] of the DHSC. It is the UK’s primary authority on health protection and carries out research to advance knowledge about protection from the risks of radiation across all sectors. PHE provides expert advice to government, national regulators in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, international organisations, the public and others.

PHE also provides the secretariat for the Administration of Radioactive Substances Advisory Committee (ARSAC). The committee advises the licensing authorities on the granting, amendment and renewal of licences to employers and practitioners for the administration of radioactive substances on people e.g. as part of medical treatment. ARSAC also provides general guidance and advice to the health departments and healthcare professionals on the use of radioactive substances in clinical medicine and research.[footnote 52]

The MHRA is an executive agency[footnote 51] of the DHSC. It regulates medicines, medical devices and blood components for transfusion in the UK. This includes medical radiological equipment.

Scotland: The Population Health Directorate of the Scottish Government has policy responsibility for public health protection aspects following a radiation event and for radon. The Scottish Government’s Healthcare Quality and Improvement Directorate is responsible for the sponsorship of HIS in respect of medical exposures regulation.

Wales: Ensuring compliance with the IR(ME)R in Wales is a function of the Welsh ministers, discharged through HIW.

NI: The Department of Health (Northern Ireland) has principal responsibility for the RQIA which is responsible for regulating medical radiological exposure (patients). RQIA inspections are undertaken with specialist advice from PHE[footnote 53].

Funding for each of the regulatory bodies in this area comes from their sponsoring government departments.

8. Public exposures and protection of the environment

Radioactive substances exist naturally in the environment and people can be exposed to this low-level radioactivity in their homes, through food and drinking water and from the atmosphere.

As set out in this document, radioactive substances are widely used by hospitals, universities and industry as well as in the nuclear power and defence industries. These activities may release radioactivity into the environment and to ensure that people and the environment are protected from the harmful effects of radioactive substances, activities involving radioactive substances are regulated.

Devolution

Environmental regulation is a devolved matter in the UK. This means that there are different environmental regulators in England, Scotland, Wales and NI and different regulations for protecting people and the environment from radioactive substances.

Radioactive substances are regulated by:

- The Environment Agency (EA) in England,

- The Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA) in Scotland,

- Natural Resources Wales (NRW) in Wales, and

- The Northern Ireland Environment Agency (NIEA) in NI

Collectively we refer to these agencies as the ‘environmental regulators’. Different regulations apply in different parts of the UK, but they all have the same purpose: to protect people and the environment from the harmful effects of radioactive substances.

The environmental regulators regulate planned uses of radioactive substances and radioactive contaminated land left from past practices.

Planned uses of radioactive substances

Planned uses of radioactive substances occur when an operator intends to use radioactive substances for a particular activity, e.g. generation of electricity using a nuclear reactor or assessing the integrity of pipework using a radioactive source. It also includes circumstances where the operator undertakes an activity that changes the way in which people may be exposed to radioactive substances, e.g. the accumulation of naturally occurring radioactive substances during the extraction of oil and gas.

Relevant legislation

The regulations for the planned use of radioactive substances are:

- The Environmental Permitting Regulations (England and Wales) 2016 (EPR16) for England and Wales;

- The Environmental Authorisations (Scotland) Regulations 2018 (EASR18) for Scotland; and

- The Radioactive Substances Act 1993 (RSA93) as amended[footnote 54] and the High-activity Sealed Radioactive Sources and Orphan Sources Regulations 2005 for NI.

If an operator wants to work with radioactive substances in a planned use, they need to be authorised under the relevant regulations to do so. This may involve making an application to the relevant environmental regulator who will assess the application and decide if the operator should be allowed to undertake that activity. If the regulator decides that the operator can undertake that activity, they will grant an authorisation[footnote 55] that will apply limits and conditions on the operator. It should be noted that for nuclear site licensees, the keeping and use of radioactive material and accumulation of radioactive waste is regulated by the ONR.

The environmental regulators carry out inspections to ensure that operators are complying with the limits and conditions applied to them and if the operator is not complying, the environmental regulators can take enforcement action to make the operator comply. If necessary, fines and in some cases, prison sentences, can be applied to the operator for non-compliance.

When an operator no longer wants to carry on the activity that has been authorised, they can apply to surrender their authorisation. The relevant environmental regulator will assess the environmental impact of ceasing the activity and ensure that the operator will leave their premises in a satisfactory state before surrender is granted.

There are some lower risk activities using radioactive substances that an operator can carry on without needing permission from the relevant environmental regulator, for example the management of low activity sealed radioactive sources[footnote 56], the use of low quantities of radioactive substances for medical and veterinary uses and the management of smoke detectors containing radioactive sources. For these activities, the operator must comply with the general requirements set out in legislation, but does not need permission from the environmental regulator to carry on the activity.

Radioactive contaminated land

Land may be contaminated with radioactive substances from past practices when the legislation and standards were not as strict as they are today, or it may be contaminated from accidents that involved the release of radioactive substances. If that land might cause harm to people, it is regulated under the Environmental Protection Act 1990 (EPA90) and associated regulations which provide a system for identifying land contaminated with radioactive substances and give the environmental regulators powers to require the land to be cleaned up.

Security of sealed radioactive sources on non-nuclear sites

The security of sealed radioactive sources on non-nuclear sites is regulated by the environmental regulators. The security requirements for sealed radioactive sources are based on standards set by the IAEA and are incorporated in UK requirements set by the National Counter Terrorism Security Office (NaCTSO). NaCTSO is a police unit that supports the government’s counter terrorism strategy. Conditions in environmental permits require operators to comply with the NaCTSO requirements and the environmental regulators work with Police Counter Terrorism Security Advisers (CTSAs) who advise on the adequacy of protective security measures for sealed radioactive sources.

Orphan sources

An orphan source is a radioactive source that should be regulated by the relevant environmental regulator but for some reason is not. This could be because the operator has failed to comply with the legislation, or because the source has been lost, abandoned or stolen. The government has duties to ensure that people working where an orphan source might be found, for example scrapyards, are aware that they may encounter them and that they have appropriate guidance issued to them. The environmental regulators have duties to ensure that advice and technical assistance is available to anyone who finds an orphan source. The environmental regulators also have powers to dispose of an orphan source or other radioactive waste if there is no-one else to do it legally.

International waste shipments

Whilst international conventions expect radioactive waste to be disposed of in the country in which it was generated, there are occasions when waste is imported and exported for treatment in another country.

Following the UK’s exit from the EU and the end of the transition period on 31 December 2020, the Transfrontier Shipment of Radioactive Waste and Spent Fuel (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 came into force to ensure the safe shipment of radioactive waste between countries. The Regulations lay down regulatory procedures for the supervision and control of shipments of radioactive waste and spent fuel between the UK and other countries in a manner consistent with the provisions of Article 27 of the Joint Convention on the Safety of Spent Fuel Management and on the Safety of Radioactive Waste Management. The regulations provide procedures for shipments to be authorised, consented to and appropriately documented, and for notification of arrival of shipments at their destination.

The environmental regulators are the competent authorities for authorising shipments into and out of their respective parts of the UK.

Imports of Radioactive Sources from the EU

The Transfrontier Shipment of Radioactive Waste and Spent Fuel (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 also ensure that imports of sealed radioactive sources into the UK from the EU are controlled and documented.

They provide that before a shipment of sealed sources can take place from the EU into the UK, consignees are required to make a prior written declaration demonstrating that they comply with national requirements for their safe storage, use and disposal. Declarations are sent by the consignee to the relevant competent authority in the UK, which acknowledge receipt of the declaration. The consignee will then forward the declaration and acknowledgment to the source holder before a shipment of sealed sources can take place. These prior written declarations will last up for to three years and may cover more than one shipment.

The appropriate regulators are the environmental regulators for non-nuclear sites, and the ONR for nuclear licenced sites.

Public exposures and protection of the environment regulators and relevant government departments

Regulators

The responsibility for protecting people and the environment from the harmful effects of radioactive substances lies with the environmental regulators:

- the Environment Agency (EA) in England;

- the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA) in Scotland;

- Natural Resources Wales (NRW) in Wales; and

- the Northern Ireland Environment Agency (NIEA) in NI

The environmental regulators work jointly where possible to ensure that consistent guidance is applied across the UK. At nuclear sites, the environmental regulators work closely with the ONR to ensure effective and efficient regulation. For example, the environmental regulators and the ONR carry out joint inspections and also consult each other on regulatory decisions that could have an impact on each other’s regulatory responsibilities.

Government departments

England: The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) has the principal responsibility for environmental protections in England and is the sponsoring department for the EA.

Scotland: The Environment and Forestry Directorate of the Scottish Government has policy responsibility for radioactive waste and nuclear decommissioning in Scotland other than on a nuclear licensed site (which is regulated by the ONR). The Directorate has principal responsibility for SEPA in respect of radioactive substances regulation.

Wales: The Environment and Rural Affairs Directorate of the Welsh Government has policy responsibility for radioactive waste and decommissioning in Wales other than on a nuclear licensed site (which is regulated by the ONR) and contingency planning for a radioactivity emergency. It also has principal responsibility for NRW.

NI: The Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA) has responsibility for regulating the keeping, use and disposal of radioactive substances; regulating radioactive transport by road, rail and inland waterway; emergency planning and response. The Northern Ireland Environment Agency (NIEA) is an Executive Agency within DAERA.

Radon

Radon is a radioactive gas that comes from the rocks and soils found everywhere in the UK. People can be exposed to radon by it entering buildings through cracks in the foundations, from building materials, water, natural gas and in underground environments such as mines, caves and tunnels. Long term exposure to radon increases the risk of lung cancer, especially when combined with tobacco smoking.

The Ionising Radiation (Basic Safety Standards) (Miscellaneous Provisions) Regulations 2018 require the government to set reference limits for indoor exposure to radon and require it to publish information on radon, its health risks, its measurement, and how radon levels may be reduced. The regulations also require the government to establish a national action plan that addresses the risks of buildings being penetrated by radon.

The UK National Radon Action Plan (NRAP) was published by PHE in December 2018. The NRAP describes the UK’s radon strategy from all significant radon sources, the arrangements that are in place for action on radon including reference levels, communications, measurements and mitigation in homes and workplaces, and identifies new topics for consideration.

Regulators for radon

Regulatory responsibility for radon lies with:

- The Health and Safety Executive (HSE) and local authorities

- Public Health England (PHE)[footnote 57] is the primary resource for advice about radon in the UK.

Radioactivity in food

Food (references to food include feed) can be contaminated with radioactive substances present in the environment. Therefore, the impact on food is considered by the environmental regulators working together with the food safety regulators.

Responsibility for regulating food safety lies with the Food Standards Agency (FSA) in England, Wales and NI and with Food Standards Scotland (FSS) in Scotland. In the UK, the environmental regulators consult the FSA and FSS where relevant on food safety as part of the process for determining applications for the use of radioactive substances.

The FSA conducts radiological monitoring of food in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. In Scotland, the radiological monitoring of food and the environment is undertaken by SEPA which works closely with the FSS to develop a holistic monitoring programme for radioactivity in food and the environment.

The FSA, FSS and environmental regulators’ food and environmental monitoring results are published annually in the joint Radioactivity in Food and Environment Report (RIFE)[footnote 58]. The FSA also publishes food monitoring data on its website.

Food may also be treated by exposure to ionising radiation in a process known as food irradiation. This may be used to reduce the presence of food poisoning and spoilage bacteria, to delay ripening or prevent the inadvertent transit of invasive insects.

A food irradiation facility must be authorised before it can treat food. The FSA in England, Wales and NI and the FSS in Scotland authorise and regulate food irradiation facilities. In addition, a food irradiation facility must be authorised by the appropriate environmental regulator for the use of radioactive substances.

Regulators for Food Safety

Regulatory responsibility for food safety lies with:

- the Food Standards Agency (FSA) in England, Wales and NI; and

- Food Standards Scotland (FSS) in Scotland.

The FSA and FSS work together with the environmental regulators to ensure food safety is considered when regulating the use of radioactive substances.

FSA in England, Wales and NI and FSS in Scotland authorise and regulate food irradiation facilities.

Radioactivity in drinking water

Responsibility for drinking water safety lies with the Drinking Water Inspectorates for England, Wales and NI and the Drinking Water Quality Regulator in Scotland. They regulate public supplies provided by water companies and licensed suppliers of water that is intended for human consumption including in cooking, drinking, food preparation and other domestic purposes as well as water used in food production undertakings.

Regulators for drinking water safety

Regulatory responsibility for drinking water safety lies with:

- the Drinking Water Inspectorate (DWI) in England and Wales,

- the Drinking Water Quality Regulator (DWQR) in Scotland, and

- the Drinking Water Inspectorate (DWI) in NI

9. Consumer products and radiation

Any business that makes, imports, distributes or sells consumer products in the UK is responsible for making sure that the products are safe for consumers to use. In the case of any potential hazard - including ionising radiation - a producer or seller of products is obliged to produce an assessment of the risks based on an expert assessment before offering a product for sale. This includes products which may contain small radioactive sources, such as smoke detectors.

Relevant legislation

As set out in chapter 4, the JoPIIRR regulations require that before any new class or type of practice involving ionising radiation can be introduced, the government must first assess it to determine whether the individual or societal benefit outweighs the health detriment it may cause.

The General Product Safety Regulations 2005 (GPSR) require all products to be safe in their normal or reasonably foreseeable usage and enforcement authorities have powers to take appropriate action when this obligation is not met. Since leaving the EU on 31 January 2020 the GPSRs, along with other EU-based product safety law, have been adopted into UK law and continue to apply to businesses providing consumer goods in the UK following the end of the transition period.

There are also specific regulations or guidance for some product sectors, setting out essential safety requirements. Where there is a crossover with the GPSR, the product-specific legislation will usually take precedence. For example, relevant building material[footnote 59] is covered by the Ionising Radiation (Basic Safety Standards) (Miscellaneous Provisions) Regulations 2018.

Demonstrating compliance with the relevant regulations

Manufacturers and importers placing products on the UK market need to demonstrate that they comply with relevant safety requirements. This involves:

- minimising the risks associated with the product

- generating and keeping records of associated technical documentation

- placing appropriate labelling on the product

- providing instructions on how to use it safely

The use of agreed standards covering aspects of the product or its production process – where these exist – is one way to demonstrate compliance.

Consumer products regulators and relevant government departments

Regulators

Local Authority Trading Standards in England, Scotland and Wales and Environmental Health services in NI provide advice and support to manufacturers and importers in their local areas. They are responsible for investigating allegations of non-compliance.

Trading Standards officers can buy or seize goods to check they are safe. They may enter premises to carry out inspections of goods or request that the business provides technical documents relating to products or its processes.

A business could face action if a product is found to be unsafe or causes harm to consumers; this could include legal action.

Under JoPIIR, Agency Agreements between the Department for Business and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) and the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) and the Health and Safety Executive Northern Ireland (HSENI) respectively delegate powers (during HSE and HSENI’s normal course of inspections e.g. of a factory producing of consumer products) to determine if any practices are being carried out that are not justified including the presence of radioactive substances in consumer products.[footnote 60]

Government departments

The Office for Product Safety and Standards (OPSS) is an office within BEIS. The OPSS provides information to consumers, businesses and regulators on product safety and enforces a range of technical, environmental and product legislation.

Public Health England (PHE)[footnote 61] is an executive agency[footnote 62] of the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC). It is the UK’s primary authority on health protection and carries out research to advance knowledge about protection from the risks of radiation across all sectors.

10. Transport of radioactive materials (RAM)

The widespread use of radioactive substances in the UK means that radioactive materials (RAM) are regularly transported around the UK and are also transported into and out of the UK. This includes radiopharmaceuticals needed for use in hospitals, sealed radioactive sources needed by the construction industry and in the non-destructive testing of North Sea oil rigs as well as the movement of spent nuclear fuel from operating and decommissioning nuclear reactors.

Unlike other areas of the UK’s safety framework, some RAM transport regulations are prescriptive and apply internationally. This is to enable the safe transport of packages containing RAM across international borders. The UK has developed specific transport regulations based on international agreements and IAEA safety standards[footnote 63].

The ALARP principle (see Chapter 3] still applies to transport regulations. The ONR’s inspectors seek ALARP solutions and encourage continuous improvements to safety during their assessment and inspection activities.

Regulations for the safe transport of RAM by road, rail and inland waterway

The regulatory framework for the transport of radioactive materials by road, rail and inland waterway in the UK is set out in:

- Part 3 of the Energy Act 2013;

- the Energy Act 2013 (Office for Nuclear Regulation) (Consequential Amendments, Transitional Provisions and Savings) Order 2014 (SI 2014 No. 469);

- the Carriage of Dangerous Goods and Use of Transportable Pressure Equipment Regulations 2009 (as amended)[footnote 64];

- the Carriage of Dangerous Goods (Amendment) Regulations 2019;

- the Carriage of Dangerous Goods and Use of Transportable Pressure Equipment Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2010 (as amended)[footnote 65];

- the Carriage of Dangerous Goods (Amendment) Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2019;

- the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974 and the Health and Safety at Work (Northern Ireland) Order 1978; and

- The Ionising Radiations Regulations 2017 and the Ionising Radiations Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2017

As well as implementing international agreements for the International Carriage of Dangerous Goods by Road (ADR), International Carriage of Dangerous Goods by Rail (RID)[footnote 66] (and limited provisions of European Agreement Concerning the International Carriage of Dangerous Goods by Inland Waterways (ADN)), these regulations set out requirements for preparing for and responding to potential radiological emergencies during the transport of radioactive material. The regulations place duties upon everyone involved in the carriage of dangerous goods to ensure that they know what they have to do to minimise the risk of incidents and guarantee an effective emergency response.

The Carriage of Dangerous Goods and Use of Transportable Pressure Equipment Regulations 2009 (as amended) and the Carriage of Dangerous Goods and Use of Transportable Pressure Equipment Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2010 (as amended) were further amended in 2019. This implemented the EP&R elements of the BSSD13.[footnote 67]

RAM transport by sea

The principal legislation for RAM transport for British registered ships and all other ships while in UK territorial waters is contained within the Merchant Shipping Act 1995 (MSA95) and associated regulations:

- Merchant Shipping (Dangerous Goods and Marine Pollutants) Regulations 1997 (SI 1997 No. 2367);

- The Merchant Shipping Notice (MSN) 1893 (M) The Carriage of Dangerous Goods and Marine Pollutants in Packaged Form: Amendment 39-18[footnote 68]; and

- The Merchant Shipping (Carriage of Packaged Irradiated Nuclear Fuel etc.) (INF Code) Regulations 2000, (SI 2000 No. 3216) covers the regulatory requirements for ships carrying spent fuel.[footnote 69]

The above regulations are enforced by the Maritime and Coastguard Agency (MCA). Under MSA95, MCA surveyors appointed by the SoS for Transport have powers, under separate legislation to board ships, survey vessels and consider the stowage and segregation requirements to ensure that they comply fully with the requirements of the International Maritime Dangerous Goods (IMDG) Code. MSA95 also provides the MCA with the powers to detain ships and issue Prohibition Notices and Improvement Notices. Where necessary the MCA can prosecute owners/charterers/Masters etc. if they do not comply with the applicable legislation.

Although responsibility for the approval of the packaging or containment systems for the carriage of radioactive material lies with the MCA. The ONR can carry out this function on MCA’s behalf under their Agency Agreement.[footnote 70] However, the ONR only approves higher hazard packages on behalf of the MCA i.e. those that legally require Competent Authority approval (e.g. Type B or fissile packages[footnote 71]). There are some packages e.g. Type A and below that do not require Competent Authority Approval.[footnote 72] Packaging not requiring Competent Authority approval is still required to comply with the applicable packaging requirements in the IMDG Code for the RAM being shipped.

The ONR also carries out a similar function of approving certain designs and shipments on behalf of the CAA and DAERA in respect of transport of RAM by air in the UK and by road in NI respectively under comparable agency agreements.[footnote 73]

The Merchant Shipping (Port State Control) Regulations 2011 and Merchant Shipping (Survey and Certification) Regulations 2015 provide a further framework for ship safety and provisions for inspections and surveys to be carried out on ships in UK waters.

RAM transport by air

The principal legislation for RAM transport for UK registered aircraft and all other flights, is contained within the Civil Aviation Act 1982 and associated regulations. These regulations apply to UK registered aircraft carrying dangerous goods whether the flight is wholly or partly within or wholly outside of the UK. All non-UK registered aircraft should have an approval, from the State of Operator[footnote 74], to carry dangerous goods by air, granted by the State of Operator. Additionally, they are required to comply with the UK regulations while flying in UK airspace.

The associated Regulations are:

- the Air Navigation Order 2016 (ANO) as amended;

- the Air Navigation (Dangerous Goods) Regulations 2002 (AN(DG)R);

- the Air Navigation (Dangerous Goods) (Amendment) Regulations 2017); and

- DOC 9284 International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) Technical Instructions for the Safe Transport of Dangerous Goods by Air (ICAO TI) as amended.

In addition, there are two EU regulations which regulate the transport of dangerous goods, including RAM, by air:

- Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 laying down technical requirements and administrative procedures related to air operations pursuant to Regulation (EC) No 216/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council (the Air Ops Regulation) as retained (and amended in UK domestic law) under the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018;

- Regulation (EU) No. 2018/1139 on common rules in the field of civil aviation and establishing a European Union Aviation Safety Agency (The Basic Regulation) (and amended in UK domestic law) under the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018

The above regulations are enforced by the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) and. under Section 60 of the Civil Aviation Act 1982 and the ANO (2016), an authorised person e.g. a CAA inspector or others that are authorised by the Competent Authority[footnote 75] has the right of access at all reasonable times to:

a) any aerodrome for the purpose of inspecting the aerodrome;

b) any aerodrome for the purpose of inspecting any aircraft on the aerodrome or any document which it or the authorised person has power to demand under this Order, or for the purpose of detaining any aircraft under the provision of this order;

c) any place where the aircraft has landed, for the purpose of inspecting the aircraft or any document which it or the authorised person has power to demand under this Order and for the purpose of detaining the aircraft under the provisions of this Order;

d) any equipment used or intended to be used in connection with the provision of a service to an aircraft in flight or on the ground; or

e) any document or record which the authorised person has power to demand under this Order.

The CAA is tasked by the Department for Transport (DfT) to conduct audits and inspections concerning all activities associated with dangerous goods in air transport including acceptance, packing, marking, documenting, loading and carriage by the aircraft operator, shippers, ground handling agents and freight forwarders.

It is further tasked to investigate and enforce in respect of apparent breaches of aviation safety rules, including dangerous goods offences. Where necessary the CAA can prosecute shippers/freight forwarders/ground handling agents and suspend or revoke dangerous goods approvals if they do not comply with the applicable legislation.