Heat and building strategy (accessible webpage)

Updated 1 March 2023

Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy by Command of Her Majesty

October 2021

CP 388

ISBN 978-1-5286-2459-6

E02666137 10/21

Chapter 1: Setting the scene

1.1. Ministerial foreword

In 2019 the UK became the first major economy to pass laws to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050. [footnote 1] In April 2021, we enshrined an ambitious target to reduce emissions by 78% by 2035 on 1990 levels into UK law. We must intensify our efforts and eliminate virtually all emissions arising from heating, cooling and energy use in our buildings. The UK has already shown that environmental action can go hand-in-hand with economic success, having grown our economy by more than three-quarters while cutting emissions by over 40 per cent since 1990. The sixth carbon budget is another indication of this government’s dedication to Britain’s green industrial revolution, positioning the UK as a global leader in the green technologies of the future. [footnote 2]

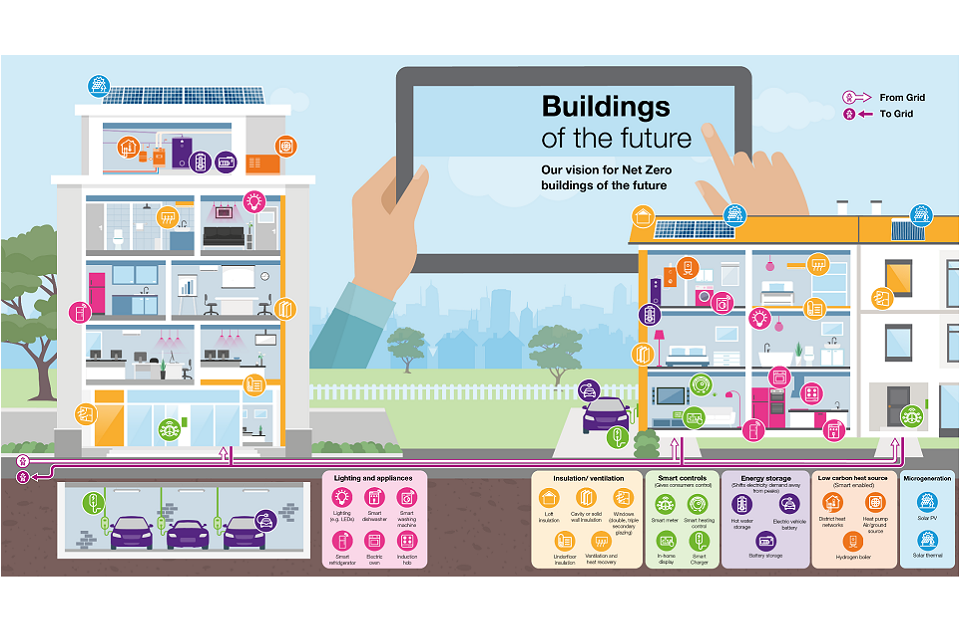

Decarbonising energy used in buildings is a key part of our Clean Growth Strategy [footnote 3] and underpins the Prime Minister’s Ten Point Plan [footnote 4] for a Green Industrial Revolution to “build back better and build back greener”. This means improving our buildings’ fabric efficiency, changing the way we heat and cool our buildings and improving the performance of energy-related products [footnote 5]. It will involve large-scale transformation and wide-ranging change to energy systems and markets, including the development of UK-based, green industrial capability and capacity. It is a challenging undertaking that has no single solution and will require a combination of leading-edge technologies and innovative consumer options. However, it also presents enormous opportunity.

The Confederation of British Industry, Climate Change Committee, National Infrastructure Commission, and International Energy Agency, and many others, have highlighted the importance of decarbonising buildings as part of a post-COVID economic response. We agree, decarbonising buildings will help the economy grow, create new green jobs and deliver greener, smarter, healthier homes and workplaces with lower bills. Delivering energy performance improvements and low-carbon heating systems will create new jobs in all parts of the UK – offering enormous potential to support our ‘levelling up’ agenda. The transition to low-carbon buildings could add £6 billion GVA (gross value added) and support 175,000 skilled, green jobs by 2030. It will create new markets and supply chains for innovative products fit for a Net Zero future, and as these markets grow, the UK may have greater export opportunities in sectors where we have particular knowledge, experience or expertise.

In driving this change, we are focusing support on the households and businesses that need it most. For example, in England we are delivering policies such as the Home Upgrade Grant and the Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund. These grants and funds are not only vital for meeting our Net Zero target, but also represent a key part of our strategy for tackling fuel poverty. We also announce the new £450 million Boiler Upgrade Scheme to support households who want to make the switch to low-carbon heat pumps with £5,000 grants.

Our ambition is to phase out the installation of natural gas boilers beyond 2035. Much like the move to electric vehicles, the move to low-carbon heating will be a gradual transition from niche product to mainstream consumer option. No-one will be forced to remove their existing boilers. Heat pumps are already a predominant technology in some other countries, and have high levels of customer satisfaction; however, work needs to be done to build UK supply chains and drive down costs. Meanwhile we will continue to invest in hydrogen heating through the neighbourhood and village trials, and the plan for the town pilot. This will allow us to take strategic decisions on the role of hydrogen in heating by 2026.

Across our diverse buildings landscape, we all have a role to play. The changes needed will be different depending on the type of building, building owner or occupier, and wider energy system considerations. An NHS hospital requires different solutions than a rented terraced home, and our policy package reflects this – tailoring our approach to different types of buildings and their occupants. This is the common-sense approach – putting consumers at the heart of our action to transform our buildings.

This strategy brings together the government’s work on energy efficiency and clean heat. It ensures that we have a consistent and coherent approach across different markets, buildings and occupancy types, and that we have robust plans which offer a credible pathway to achieving carbon budgets and lay the foundations for Net Zero buildings in the UK by 2050.

Rt Hon Kwasi Kwarteng MP

Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy

1.2. Our Heat and Buildings Strategy – at a glance

The strategy sets out the vision for a greener future, which creates hundreds of thousands of green, skilled jobs, drives the levelling up agenda and generates opportunities for the growth of British businesses. The transition to high-efficiency low-carbon buildings can and must take account of individual, local and regional circumstances. Interventions need to be tailored to the people and markets they serve. The strategy outlines a transition that focuses on reducing bills and improving comfort through energy efficiency, and building the markets required to transition to low-carbon heat and reducing costs, while testing the viability of hydrogen for heating. This will provide a huge opportunity for levelling up – supporting 240,000 skilled, green jobs by 2035, concentrated on areas of the UK where investment is needed most. This section sets out:

- the rationale behind our approach

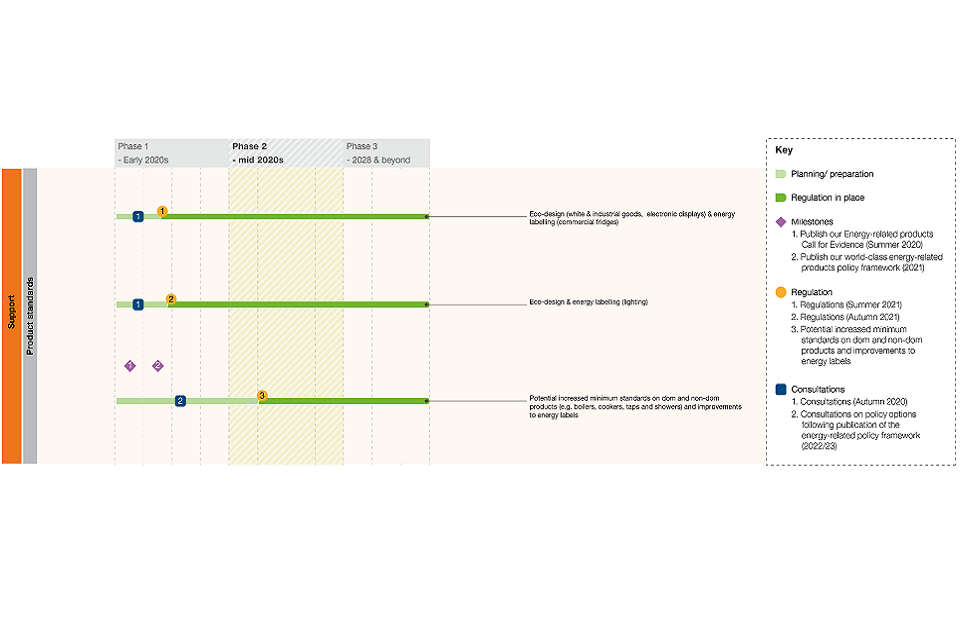

- the principles and phasing of the policy package that delivers them

- key commitments for action

To meet Net Zero virtually all heat in buildings will need to be decarbonised.

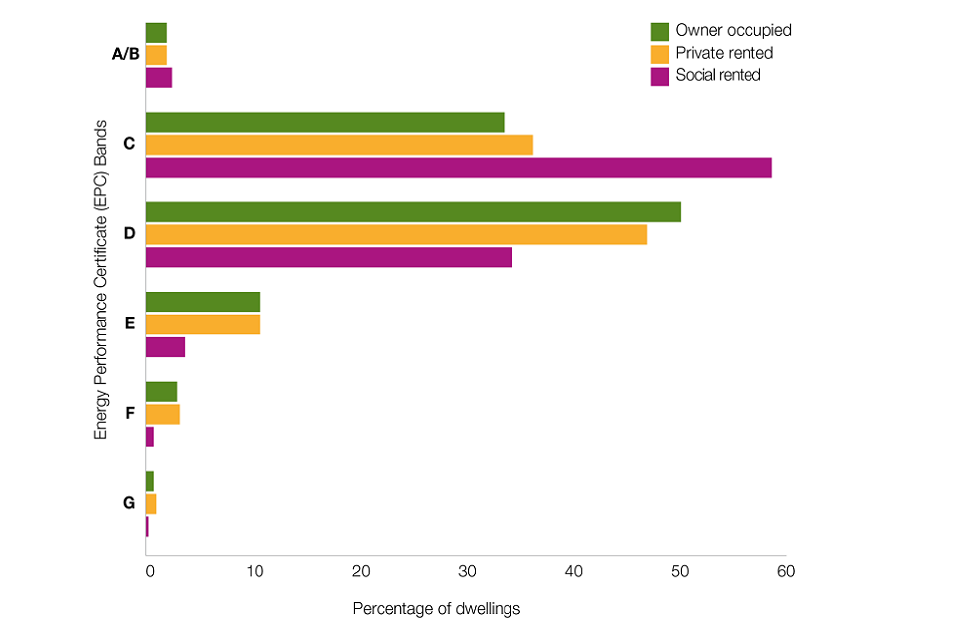

The benefits of more efficient, low-carbon buildings for consumers are clear: smarter, better performing buildings, reduced energy bills and healthier, more comfortable environments. Additionally, studies indicate that more energy efficient properties typically have a higher value than less efficient ones. Evidence from a study commissioned by BEIS indicated that properties with an EPC C rating were worth around 5% more than those currently at EPC D rating, after controlling for other factors such as property size and archetype. The 2020s will be key to delivering a step change in reducing emissions from buildings and establishing the foundations of a pathway to Net Zero. This means improving the efficiency and flexibility of our buildings, and developing the UK supply chains and technology options needed to save carbon throughout the decade and put us on a cost-effective pathway to Net Zero.

The buildings transition presents huge opportunities for jobs, growth and levelling up.

Decarbonising buildings can provide a major economic stimulus, creating new highly-skilled jobs, products, markets, and supply chains in the UK, fit for a Net Zero future. As building improvements are labour-intensive, upgrading our homes and workplaces could rapidly create new opportunities and support over 240,000 low-carbon jobs by 2035 across the sector (from manufacture to installation and modelling to project management) as part of a green recovery, while also reducing energy bills and delivering better, greener, and healthier homes and workplaces. [footnote 6] As the global market for low-carbon heat, smart products, and energy efficiency grows, UK businesses can make use of export opportunities in sectors where we have developed particular knowledge, experience and expertise. We are working to ensure that these opportunities are available across the UK, especially where they can help level up certain areas.

Fairness and affordability are at the heart of our approach.

Investing in energy efficiency will bring down bills for millions of households and businesses – with Government support for low income households to pay for improvements. Meanwhile we are acting to reduce the costs of low-carbon heat – with the ambition of working with industry to reduce the costs of heat pumps by at least 25-50% by 2025 and towards parity with boilers by 2030, and supporting consumers who switch early with £5,000 Boiler Upgrade Scheme grants. Alongside action to remove distortions in energy prices, heat pumps should be no more expensive to buy and run than existing boilers and we are investing in innovation to make them smaller, easier to install and beautiful in design.

Ultimately, Net Zero will mean gradually, but completely, moving away from burning fossil fuels for heating.

Which is why we are setting the ambition of phasing out the installation of new natural gas boilers from 2035. The future is likely to see a mix of low-carbon technologies used for heating: electrification of heat for buildings using hydronic (air-to-water or ground-to-water) heat pumps, heat networks and potentially switching the natural gas in the grid to low-carbon hydrogen. While there is work to be done to identify the best solutions for different buildings and regions, there are also areas where the solution is clear and we can take decisive, ‘no-regrets’ action now. No or low-regrets’ means actions that are cost-effective now and will continue to prove beneficial in future. For example, installing energy efficiency measures reduce consumer bills now, while making buildings warmer and comfier, but have the added benefit of making future installations of low-carbon heating more cost-effective. For example, hydronic heat pumps will be a key technology for new buildings and buildings not connected to the gas grid, and heat networks will be a key technology in areas of high-density heat demand and where there are large low-carbon heat sources. Consultations published alongside this strategy propose how regulations can encourage the transition in these segments

We will take major strategic decisions on the role of Hydrogen for heat by 2026.

The infrastructural and regulatory implications that will come with mass adoption of different low-carbon heat sources – such as new electricity generation capacity and network reinforcement and additional hydrogen production plants – will be transformational. Strategic decisions will be required to enable a co-ordinated, efficient, effective and affordable mass decarbonisation by 2050. These decisions will need to be informed by a comprehensive programme of research, development, planning and innovation over the coming years. In particular, we will explore the potential to use hydrogen for heating buildings in the next few years to inform a strategic decision on the role of hydrogen in decarbonising heat in 2026. Along our journey to Net Zero, we will need to take co-ordinated decisions across all levels – national, regional, local and individual – to ensure we deploy the most suitable low-carbon heat source for that area or building.

We need to act now to develop the market and bring down costs for energy efficient low-carbon heat.

Heat pumps and Heat Networks are proven scalable options for decarbonising heat and will play substantial roles in any Net Zero scenario, so we need to build the market for them now. A UK market with the capacity and capability to deploy at least 600,000 hydronic heat pump systems per year by 2028 can keep us on track to get to Net Zero and set us up for further growth if required. This means ramping up UK-based supply chain and deployment from approximately 35,000 heat pumps a year [footnote 7], to potentially being able to replace around 1.7 million fossil fuel boilers per year by the mid-2030s. [footnote 8] We are also working on and investing £338 million over 2022/23 to 2024/25 into a broader Heat Network Transformation Programme to scale up low-carbon heat network deployment and to enable local areas to deploy heat network zoning, which will create a step-change in low-carbon heat network market growth.

The journey to Net Zero buildings starts with better energy performance.

Increased awareness of energy use and the need for greater efficiency is the first stepping-stone to enabling consumer decisions to improve building energy performance and use smarter, more efficient products and systems. Improving energy efficiency by adopting a fabric-first approach is key in ensuring the transition to low-carbon heating is cost-effective and resilient. ‘Fabric-first’ means focusing on installing measures that upgrade the building fabric (e.g. walls/lofts) itself before making changes to the heating system. We are committed to supporting businesses and households to upgrade as many buildings as possible to higher levels of energy efficiency and flexibility, in a way that will ensure long-term compatibility with low-carbon heating systems.

We need to take a co-ordinated system-wide approach to decarbonise cost-effectively.

To deliver Net Zero in a way that delivers value to consumers, we need to consider the measures needed to decarbonise heat alongside the decarbonisation action needed in other sectors. This includes the generation, distribution and storage of energy (such as electricity and hydrogen), and the associated investment and reinforcement of infrastructure required. We will need to consider this at a national and local level. To minimise generation demand and thereby reduce costs, we need to create a smart and flexible energy system, and ensure buildings use energy in a smart and flexible way.

Our policy approach

We have developed a set of five core principles to guide action in the 2020s and longer-term transformation to Net Zero.

1. We need to take a whole-buildings and whole-system approach to minimise costs of decarbonisation - We will consider the heating system in the context of what is most appropriate for the whole building, as well as considering local and regional suitability and how best to manage system-level impacts (this is explored in Chapter 3). This will also deliver UK jobs across a variety of specialisms.

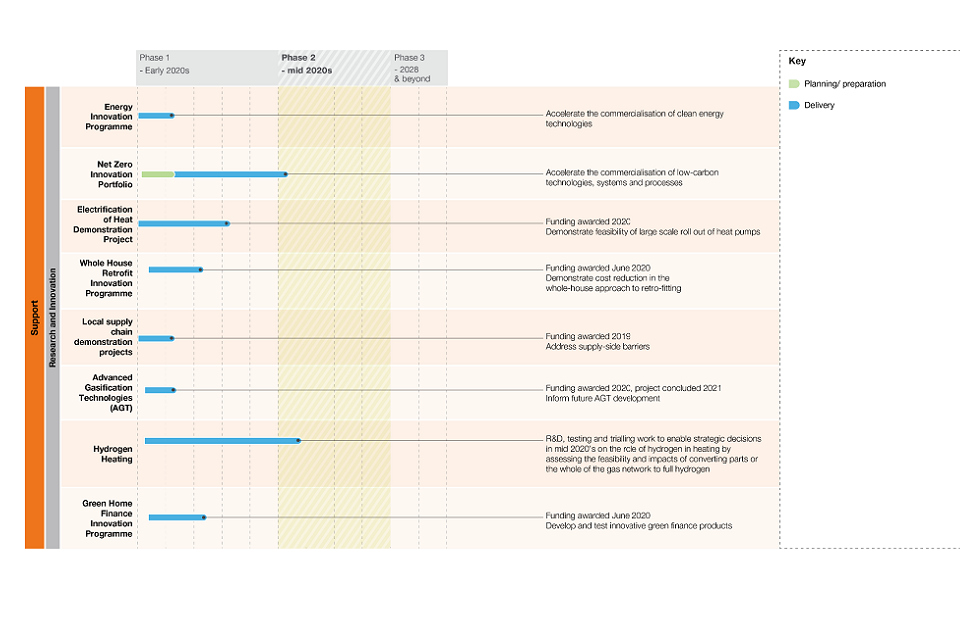

2. Innovation is essential to driving down costs, improving options and informing future decisions - We will ensure that regional, local and national decisions can be informed by the latest data and research and we will continue to work with industry to refine processes and technologies to deliver value for money and value for the UK economy (this is explored in Chapter 4).

3. In parallel, we need to accelerate ‘no- and low-regrets’ action now - Prioritising action to: improve buildings with low energy performance and high-carbon emissions, futureproof new-builds to avoid the need for later retrofitting, adopt a fabric-first approach to improve building thermal efficiency, increase the performance of products and appliances, ensuring climate change resilience by mitigating risks of overheating and poor air quality, build the market by developing our technical expertise, growing the workforce, and expanding the UK’s manufacturing capacity and capability. This includes building the market to install at least 600,000 hydronic heat pumps per year by 2028, which we know will be needed in all paths to Net Zero (this is explored in Chapter 5).

4. We will balance certainty and flexibility to provide both stability for investment and an enabling environment for different approaches to be taken to address different buildings - We will provide long-term signals to investment by setting requirements and embedding flexibility in how they are achieved, so businesses and the public can prepare to decarbonise in a way that suits them and maximise the opportunities this presents, including investing in training in greener skills (this is explored in Chapter 5).

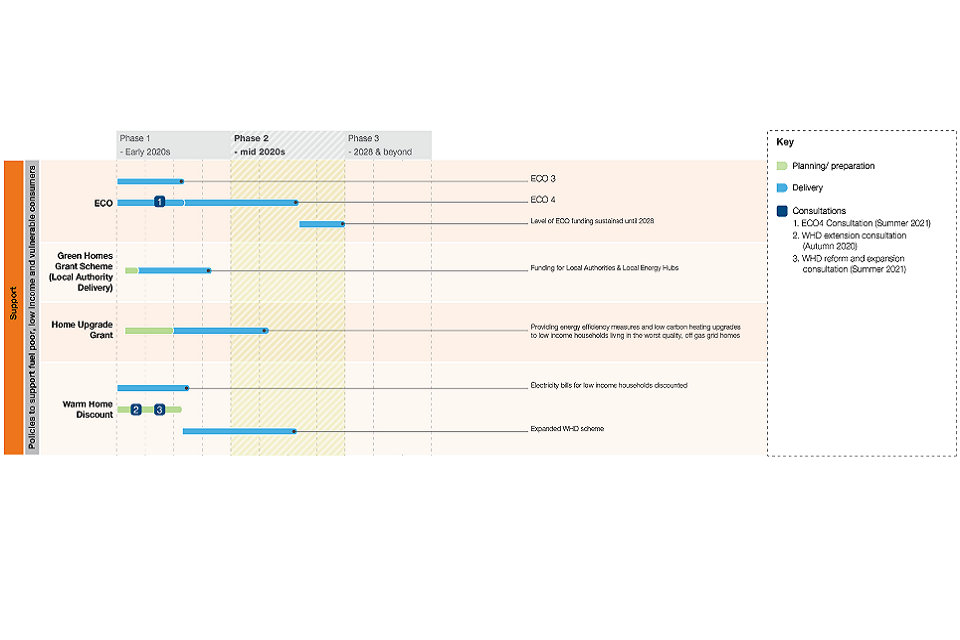

5. Government will target support to enable action for those in most need - We will make sure that our policies support those who are hardest hit by COVID-19, such as small businesses and the fuel poor. We will also use taxpayer money efficiently to transform public sector buildings and improve the support and protection available for consumers (this is explored in Chapter 6).

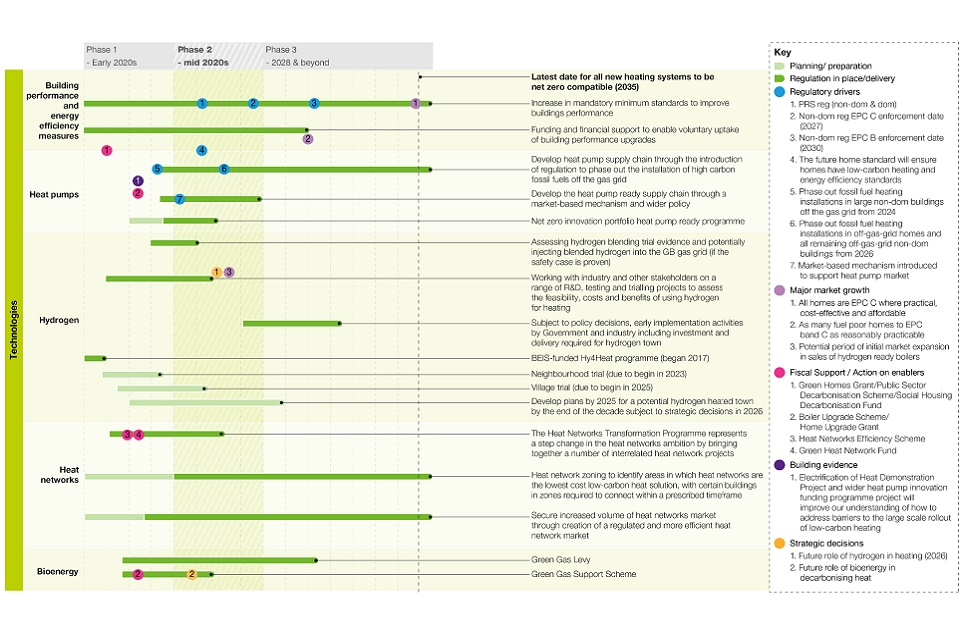

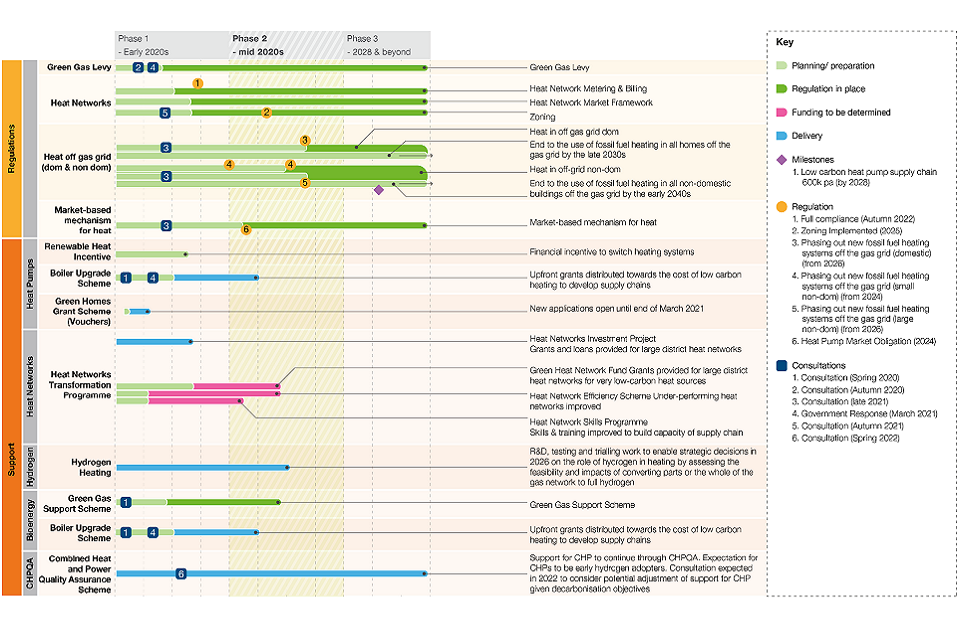

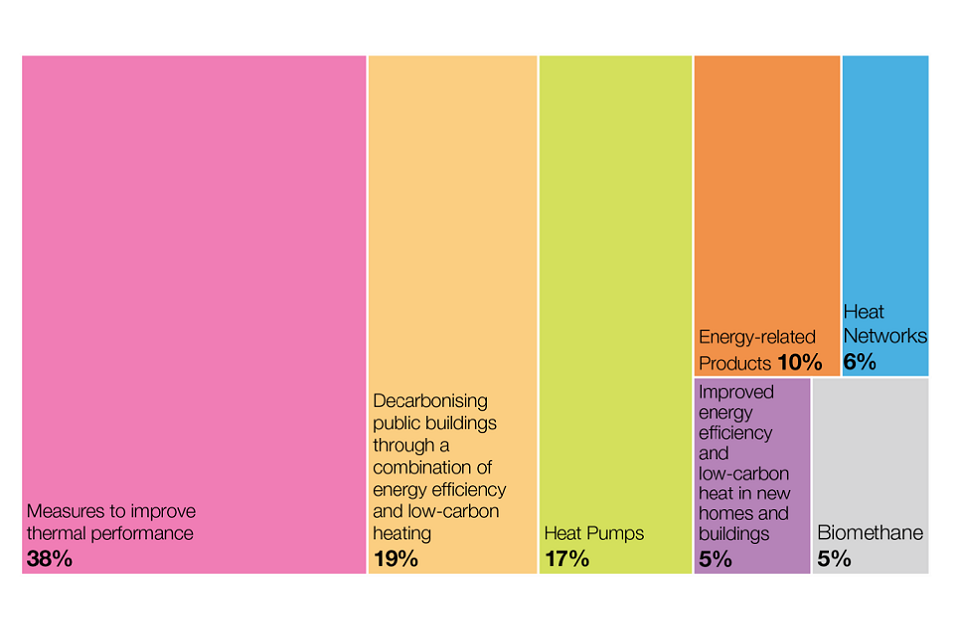

Figure 1: Our policy approach

Diagram showing breadth of activities for new decade

Open a larger version of the image

What we will do – key commitments

Upgrading our building stock will require a comprehensive package of measures to be implemented in the next decade. This strategy outlines how we plan to:

Deliver the Ten Point Plan [footnote 9] ambition to develop the markets and consumer choices required to achieve Net Zero heating:

1. Signalling our intention to phase out the installation of new natural gas boilers from 2035: Given the lifetime of a natural gas boiler is around 15 years, in order to reach Net Zero in a cost-effective consumer-friendly way, we aim to phase out the installation of new natural gas boilers beyond 2035, once costs of low-carbon alternatives have come down. No-one will be forced to remove their existing boilers. Instead, we will grow the market for heat pumps through incentivising early adopters through Boiler Upgrade Scheme grants, proposing introduction of a market-based regulation on manufacturers [footnote 10] similar to that which has been successful in growing the market for electric vehicles, and phasing out the installation of the dirtiest and most expensive fossil fuel systems and deployment in new buildings. This would be in line with the natural replacement cycle, including any hydrogen ready boiler in any areas not converting to hydrogen, to ensure all heating systems used in 2050 are compatible with Net Zero.

2. Setting a clear ambition for industry to reduce the costs of installing a heat pump by at least 25-50% by 2025 and to ensure heat pumps are no more expensive to buy and run than gas boilers by 2030: We understand that capital costs can act as a barrier and that investment to refine technologies, supply and installation requires clear signals and market certainty. Therefore, working with industry, we are setting out our ambition to see significant cost reductions. We know that industry is ready to back these ambitions in response to the package of measures in this strategy and accompanying publications.

3. Improving heat pump appeal by continuing to invest in research and innovation: Together with industry we must continue to innovate to reduce the barriers to installation, making heat pumps beautifully designed, smaller, and easier to install and use. We are investing in new innovation opportunities - as part of the Net Zero Innovation Portfolio - aimed at advancing heat electrification to support the decarbonisation of homes. The £60 million Net Zero Innovation Portfolio (NZIP) ‘Heat Pump Ready’ Programme will support the development of innovation across the heat pump sector, including to improve the consumer experience in installing and using a heat pump. This will build on our previous Energy Innovation Programme activities, such as the Electrification of Heat Demonstration Project and Green Home Finance Innovation Programme.

4. Ensuring affordability by providing financial support to meet capital costs: Our ambition is to ensure that the costs of decarbonising heat and buildings falls fairly across society. Consumers who choose to switch to a heat pump will be supported in making the transition to a heat pump. We have published our government response on a clean heat grant [footnote 11], called the Boiler Upgrade Scheme, to support deployment of low-carbon heat in existing buildings. This will provide households with £5,000 grants when they switch to an air source heat pump or £6,000 when they switch to a ground source one.

5. Rebalancing energy prices to ensure that heat pumps are no more expensive to buy and run than gas boilers: Clean, cheap electricity is an everyday essential. We have seen the impact of overreliance on gas pushing up prices for hardworking people but our plan to expand our domestic renewables will push down electricity wholesale prices. However, current pricing of electricity and gas does not incentivise consumers to make green choices, such as switching from gas boilers to electric heat pumps. We want to reduce electricity costs so when the current gas spike subsides we will look at options to shift or rebalance energy levies (such as the Renewables Obligation and Feed-in-Tariffs) and obligations (such as the Energy Company Obligation) away from electricity to gas over this decade. This will include looking at options to expand carbon pricing and remove costs from electricity bills while ensuring that we continue to limit any impact on bills overall. We know that in the long run, green products are more efficient and cheaper, and we are putting fairness and affordability at the heart of our approach. We will launch a Fairness and Affordability Call for Evidence on these options for energy levies and obligations to help rebalance electricity and gas prices and to support green choices, with a view to taking decisions in 2022.

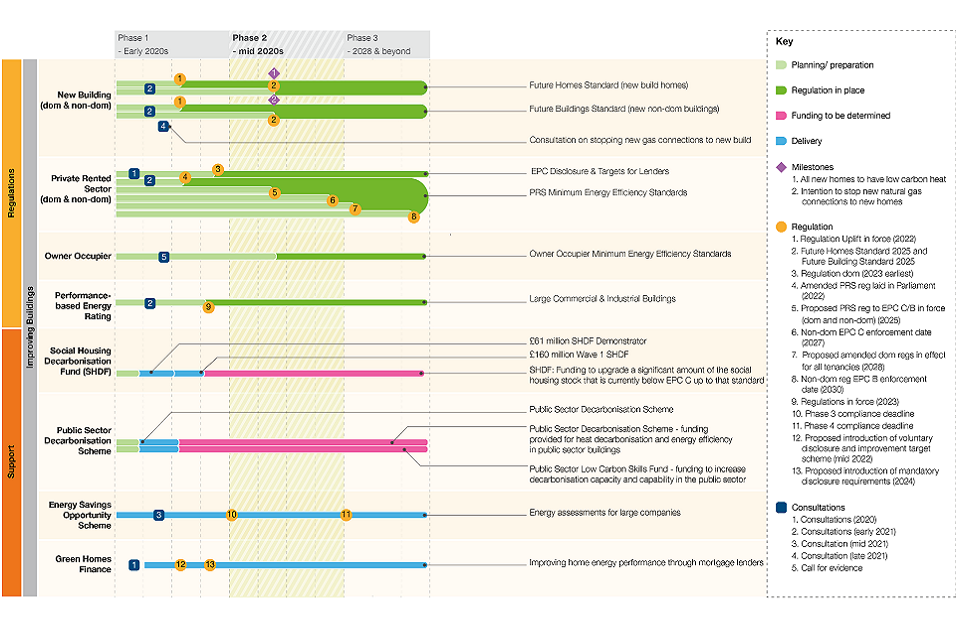

6. Significantly growing the supply chain for heat pumps to 2028: We will go from installing around 35,000 hydronic heat pumps a year [footnote 12] to a minimum market capacity of 600,000 per year by 2028. This will be supported by the introduction of a market-based mechanism to establish the incentives for industry to take the lead in transforming the consumer market in low-carbon heating, which we are consulting on alongside this Strategy. [footnote 13] In all future heat scenarios - including if hydrogen is proven to be feasible and preferable to use in heating some buildings - 600,000 hydronic heat pump installations per year is the minimum number that will be required by 2028 to be on track to deliver Net Zero. Hydronic heat pump systems will be the key technology for many properties in the future, including: properties that are not connected to the gas grid, new-builds requiring low-carbon heating, and existing buildings where consumers ultimately opt to switch to heat pumps in preference to other low-carbon heating options. To ensure we can build the UK low-carbon heat market sustainably towards the 1.7 million heating systems per year needed by 2035, further policy would be required to phase out installation of new fossil fuel heating. We could grow the heat pump market and transition consumers in stages, while continuing to follow natural replacement cycles to work with the grain of consumer behaviour.

7. Ensuring all new buildings in England are ready for Net Zero from 2025: [footnote 14] We are bringing in the Future Homes Standard and have consulted on the Future Buildings Standard for new-builds in England. Government’s ambition is to build 300,000 new homes a year by the mid-2020s. [footnote 15] We anticipate at least a third of our 2028 heat pump target to be installed in new build domestic properties annually. To enable this, we will introduce new standards through legislation (such as Building Regulations) to ensure new homes and buildings will be fitted with low-carbon heating and high levels of energy efficiency, so that new buildings do not have to be retrofitted in the future. We will also consult on ending new connections to the gas grid.

8. We intend to start by phasing out the installation of fossil fuel heating systems in properties not connected to the gas grid: Alongside this strategy, we are consulting on ending the installation of high-carbon fossil fuels to heat homes that are not connected to the gas grid in England from 2026 and non-domestic buildings not connected to the gas grid from 2024. Households will not be forced to remove their existing boilers, instead we will be taking an approach that goes with the grain of markets and consumer behaviour to minimise costs and disruption. We are keen to hear views on this approach, and in particular whether there are sectors or building types with specific needs that should be taken into account, for example, heritage buildings or those occupied by voluntary sector organisations.

9. Growing UK-manufactured technology and capabilities: We want manufacturers to scale-up UK production to help meet UK demand and we are aiming for a 30-fold increase in heat pumps manufactured and sold within the UK by the end of the decade. This ensures the UK gets the full economic benefit of investment including benefits to businesses and customers, through reduced costs and emissions from supply chains and shipping. Growing UK manufacture and supply of heat pumps to over 300,000 units a year by 2028 could increase the rate of installation, grow opportunities for exports, and create more than 10,000 manufacturing-related UK jobs. Recent investments into low-carbon technology manufacture and supply are welcome early steps in this direction.

10. Ensuring the electricity system can accommodate increased electricity demand and heat pumps can be quickly and affordably connected to the network: We will work with Ofgem, distribution network operators, and other local actors on the approach to planning the network in Great Britain and delivering smart, secure, cost-effective solutions. We will also consider carefully the role of flexibility within buildings, including the potential for storage and hybrid technologies in combination with flexible tariffs.

Deliver the Ten Point Plan [footnote 16] commitment to develop hydrogen for heating through:

11. Developing hydrogen for heating buildings by thoroughly assessing the feasibility, safety, consumer experience and other costs and benefits, by the middle of the decade: We will work in partnership with industry and other key stakeholders to test and evaluate the potential of hydrogen as an option for heating our homes and workplaces.

12. Establishing large-scale trials of hydrogen for heating: We will support industry to conduct first-of-a-kind 100% hydrogen heating trials, including a neighbourhood trial by 2023 and a village scale trial by 2025. We will also develop plans by 2025 for a possible hydrogen town that can be converted before the end of the decade. Earlier this year BEIS and Ofgem wrote to the gas distribution network operators inviting them to develop proposals for a village trial. [footnote 17] We also published a consultation on facilitating a grid conversion hydrogen heating trial [footnote 18] in August 2021.

13. Enabling blending of hydrogen in the gas grid: As stated in UK hydrogen strategy [footnote 19], we are engaging with industry and regulators to develop the safety case, technical and cost-effectiveness assessments of blending up to 20% hydrogen (by volume) into the existing gas network. This has the potential to deliver up to 7% emissions reductions from the grid, whilst supporting the development of the UK Hydrogen Economy. We aim to provide an indicative assessment of the value for money case for blending by autumn 2022, with a final policy decision likely to take place in 2023.

14. Consulting on hydrogen-ready boilers: soon, we aim to consult on the case for enabling, or requiring, new natural gas boilers to be easily convertible to use hydrogen (‘hydrogen-ready’) by 2026, in line with our timelines to take broader strategic decisions about the role of hydrogen in heating buildings. This would mean that new boilers would be fit for the future, minimising later disruption and costs to consumers. We will also use this consultation to test proposals on the future of broader boiler and heating system efficiency and explore the best ways to reduce carbon emissions from gas heating systems over the next decade.

15. Developing the evidence base necessary to take strategic decisions on the role of hydrogen for heating buildings in 2026: Local trials and planning work, together with the results of our wider research and development and testing programme, will inform and enable strategic decisions about the role of hydrogen for heating in delivering Net Zero, and the actions that will be required to support this. We anticipate that conclusions from our ongoing research will be available in the mid-2020s and we intend to take strategic decisions on the role of hydrogen in heating buildings in 2026.

Deliver the Ten Point Plan [footnote 20] commitment to Greener Buildings through:

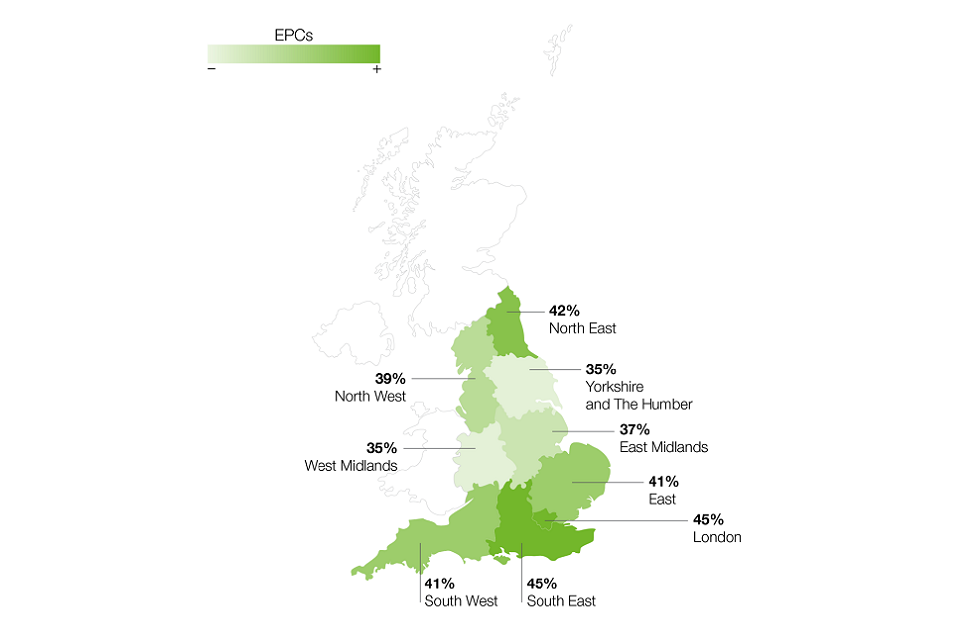

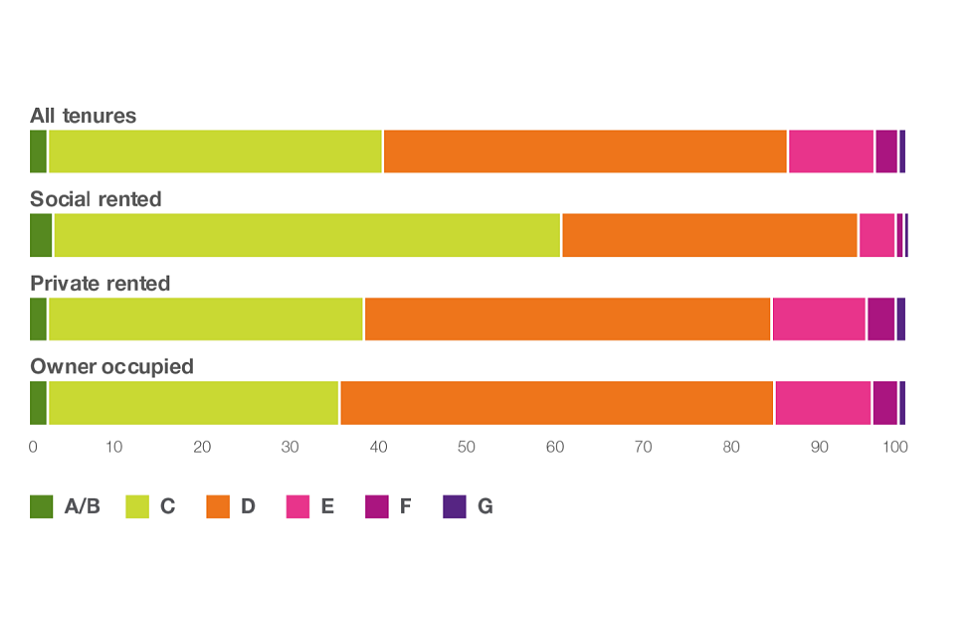

16. Improving the performance of existing homes: Continue to drive improvements to poorer performing homes throughout the 2020s, in line with the commitment we made in our Clean Growth Strategy [footnote 21] for as many homes as possible to achieve EPC band C by 2035 where cost-effective, practical and affordable, and our commitment to reduce fuel poverty by ensuring as many fuel poor homes in England, as reasonably practicable, achieve a minimum energy efficiency rating of band C by the end of 2030 [footnote 22], [footnote 23] We have also consulted on driving energy efficiency improvements in the private-rented sector and aim to publish a response before the end of the year. [footnote 24]

17. Supporting social housing, low income and fuel poor households: We will continue to ensure financial support is targeted to those who need it most, supporting the most vulnerable in society in switching to low-carbon heating and improving the energy efficiency of their homes. We are boosting funding for the Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund (investing a further £800 million over 2022/23 to 2024/25) and Home Upgrade Grant (investing a further £950 million over 2022/23 to 2024/25), which aim to improve the energy performance of low income households’ homes, support low-carbon heat installations, help to reduce fuel poverty and build the green retrofitting sector to benefit all homeowners.

18. Leading through the public sector: We aim to reduce direct emissions from public sector buildings by 75% against a 2017 baseline by the end of carbon budget 6. We will encourage public sector organisations to monitor and report their energy use, develop and deploy plans to decarbonise, including by applying for government funding, and to lead by example to build demand and encourage other sectors to decarbonise. We have already made available over £1 billion through the Public Sector Decarbonisation Scheme [footnote 25] which will provide critical support and drive whole-building interventions that deliver energy efficiency and low-carbon heating at the same time. We are investing a £1425 million into this scheme over 2022/23 to 2024/25.

19. Setting long-term direction and clear signals: We will build on our 2020 consultation on improving the energy performance of privately rented homes [footnote 26] using minimum standards to ensure the UK housing stock is on track to meet EPC band C by 2035 where practical, cost-effective and affordable. Our approach to raising minimum standards will work with the grain of the market, using natural trigger points to help minimise disruption to consumers. We will consider different segments of our building stock individually, helping to ensure we take a tailored pathway to improving our homes, workplaces and public spaces. There is no one-size-fits-all solution to heat decarbonisation, and our approach to regulation demonstrates this. For example, the Decent Homes Standard review will consider how the standard can work to support better energy efficiency and the decarbonisation of social homes, and we are also exploring opportunities to improve the energy performance of owner-occupier homes. We are considering how we can kick start the green finance market and have consulted on introducing mandatory disclosure requirements for mortgage lenders on the energy performance of homes on which they lend, and on setting voluntary improvement targets to be met by 2030. In addition, we will consider the case for setting a date to ensure that all homes meet a Net Zero minimum energy performance standard before 2050, where cost-effective, practical and affordable.

20. Significantly reducing energy consumption of commercial, and industrial buildings by 2030: This will deliver significant emissions reductions and deliver cost savings for businesses by: setting privately-rented commercial buildings a minimum efficiency standard of EPC band B by 2030 in England and Wales, introducing a new and innovative performance-based energy rating for large commercial and industrial buildings, over 1,000m2 which use more energy than all other commercial and industrial buildings, while only accounting for about 7% of the stock [footnote 27] and can deliver significant energy and emission reductions, consulting on regulating the owner-occupier sector later this year

21. Launch a new world-class policy framework for energy-related products: We will continue to pursue and explore policies that increase use of energy efficient, smart and sustainable products and maximise their associated benefits, following our departure from the EU. We plan to launch our new Energy Related Products Policy Framework which will be published in due course and include illustrative proposals on a range of products including cookers, boilers (including consideration of hybrids), showers, taps and heat emitters. The introduction of this new framework will reduce consumer bills, reduce energy consumption, and reduce emissions by ensuring that when consumers invest in new products, they are buying products that have been made to high efficiency standards.

22. Considering how to ensure flexible demand and supply (including through smart technologies and energy storage) is taken into account across the full range of energy performance, fuel poverty and heat policies, including regulation and subsidy schemes: We will build on existing work to consider how to recognise technologies in the Standard Assessment Procedure (SAP) methodology, so that buildings are decarbonised in a way that works for the consumer and the wider energy system.

23. Developing a workforce pipeline with the skills to meet the requirements of Net Zero transition: Government is working closely with industry to ensure that installers have up-to-date, high-quality training and that they are not undercut by installers who offer cheaper, low-quality installations. This involves developing new core competencies and agreed training criteria for installing low-carbon heating systems and ensuring energy efficiency improvements are delivered to high standards, using quality and certification schemes, and specification standards.

Deliver further critical carbon savings and Energy White Paper. [footnote 28] commitments through:

24. Accelerating growth of the low-carbon heat network market through a series of complementary measures: We will continue to provide funding through the Green Heat Network Fund and Heat Networks Investment Project to support current market growth, and develop the heat network zoning approach in England. [footnote 29] This is part of a broader Heat Network Transformation Programme, in which we are investing £338 million (over 2022/23 to 2024/25). We will develop regulations to drive decarbonisation and deliver better consumer protections, all as part of a comprehensive transformation programme for heat networks.

25. Increasing the proportion of biomethane in the gas grid in Great Britain: We will deliver the Green Gas Support Scheme (GGSS) to support the injection of biomethane from anaerobic digestion (expected to deliver 2.8TWh of renewable heat per year in 2030/31). In the long term, we will explore the development of commercial-scale gasification and a potential biomethane support scheme to replace the GGSS after 2025.

1.3. Background

This Heat and Buildings Strategy aims to set out the immediate actions and long-term signals required to reduce emissions from buildings to near zero (between 0 and 2 MtCO2e) by 2050.

This section:

- sets the context for decarbonising buildings

- introduces other key aims to be progressed in parallel when decarbonising buildings

In 2019, the UK government set out a target to achieve net zero greenhouse gas emissions across the whole UK by 2050. [footnote 30] This commitment, enshrined in the Climate Change Act (2008), means that we have 30 years to completely decarbonise the economy. But this presents substantial opportunities for the UK: to grow skills, build diverse job markets, level up across the country, reduce bills by improving efficiency, tackle fuel poverty, have warmer and better buildings, and ensure our energy system is secure and fit for the future. We will take a phased and targeted approach to ensure a gradual transition to Net Zero.

To ensure continued progress, we have set a series of targets to reduce near- and medium-term greenhouse gas emissions through our legally-binding carbon budgets. The fourth, fifth and sixth carbon budgets cover the periods 2023-2027, 2028-2032 and 2033-2037 respectively. In December 2020, the UK committed to an interim target to reduce economy-wide greenhouse gas emissions by at least 68% (compared to 1990 levels) by 2030 as part of our Nationally Determined Contribution towards delivering the goals of the Paris Agreement. [footnote 31]

Decarbonising buildings is central to that challenge. To meet our Net Zero goal, we urgently need to address the carbon emissions produced in heating and powering our homes, workplaces and public buildings. Energy is central to our lives, providing comfort and entertainment in our homes, as well as enabling healthy and productive workplaces. We use energy for heating and cooling, cooking, hot water, and other energy-using products. And while the electricity that powers our lighting and appliances is decarbonising fast, the majority of buildings still rely on burning fossil fuels for heating, hot water and cooking.

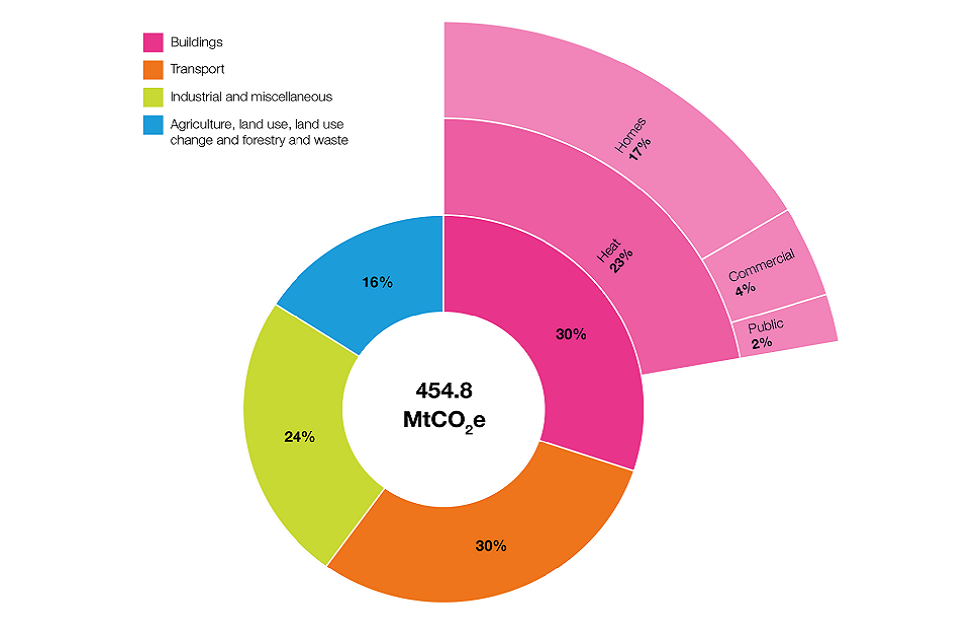

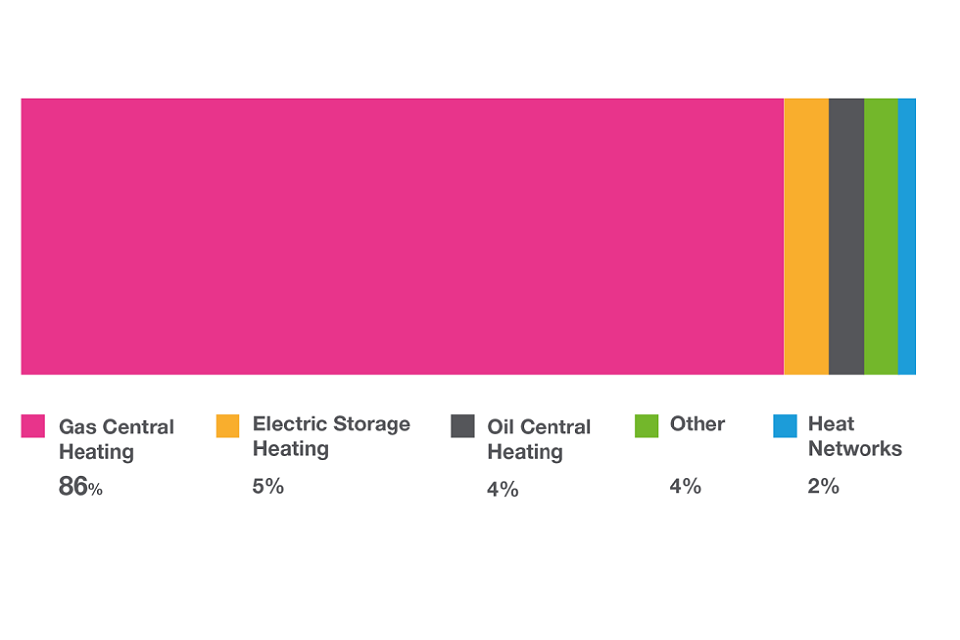

There are about 30 million buildings in the UK. [footnote 32] In total, these buildings are responsible for around 30% of our national emissions. [footnote 33] The vast majority of these emissions result from heating: 79% of buildings emissions and about 23% of all UK emissions. [footnote 34]

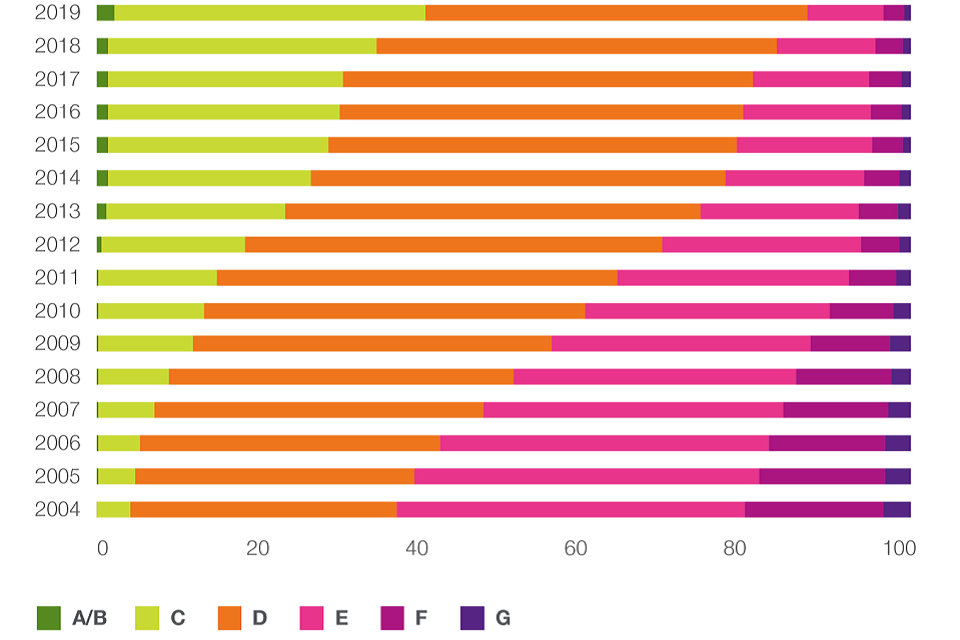

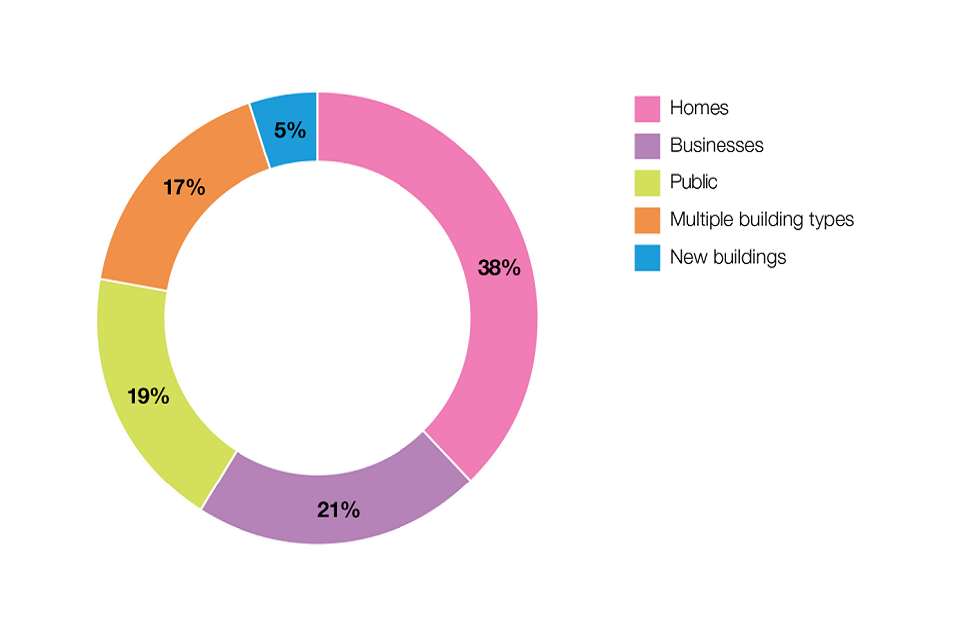

Figure 2: UK emissions in 2019

Proportion of emissions in 2019 from building explained further in text

Figure 2 shows the proportion of emissions in 2019 from buildings to the nearest whole number; of the 454.8 mega tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2e) total emissions, 23% were due to heating buildings, with the largest proportion of this stemming from homes. [footnote 35]

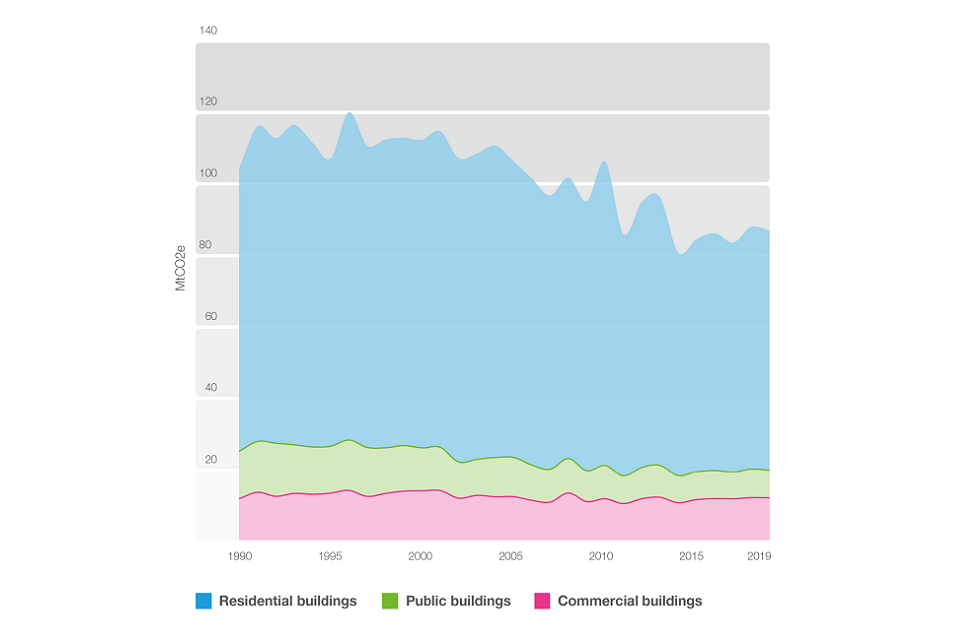

Figure 3: Direct emissions from heat in buildings (1990-2019)

Graph showing proportion of direct emissions from heat in buildings from 1990 to 2019 split by building type

Figure 3 shows the proportion of direct emissions from heat in buildings from 1990 to 2019 split by building type – commercial, public sector and residential. [footnote 36]

The Clean Growth Strategy [footnote 37], published in 2017, set out our high-level plans for meeting carbon budgets, and acknowledged the particular challenge posed by decarbonising heating. It set out a range of actions to reduce the energy use of buildings and deliver low-carbon heat through activities such as the Renewable Heat Incentive and the Heat Networks Investment Project.

We followed this in 2018 with Clean Growth: Transforming Heating [footnote 38], a review of the evidence and options available for decarbonising heat. The review concluded that it is unlikely that there will be a one-size-fits-all solution, so multiple technologies will play a role on our path to Net Zero. We identified major challenges and barriers that need to be addressed, and the need for strategic decisions for the future of heat infrastructure in the 2020s.

This Heat and Buildings Strategy fulfils the commitment made in Clean Growth: Transforming Heating [footnote 39] to produce a roadmap for heat policy, and acts as the UK’s Long Term Renovation Strategy. [footnote 40] As well as a roadmap, this document also takes a holistic approach to energy use in buildings, considering product and building efficiency as well as heat decarbonisation. This document builds on the Prime Minister’s Ten Point Plan [footnote 41] and the Energy White Paper [footnote 42] announced in 2020 to provide a clear direction of travel for the 2020s, demonstrating how we will meet our carbon targets, ensure we are on track for Net Zero and rapidly support jobs and levelling up. It also sets out how we are approaching the big strategic choices that need to be taken during this decade.

In this strategy, our primary focus is on reducing emissions from heating, which, given the UK’s climate, is the predominant source of emissions from buildings. However, we are mindful of the current and potential future demand of cooling, which we will look to consider further as we continue to develop our approach to long-term choices for low-carbon heating.

The strategy does not include our plans to decarbonise ‘process heat’ – the heating required for the manufacture of products – as this is included in our Industrial decarbonisation strategy [footnote 43], published in March 2021.

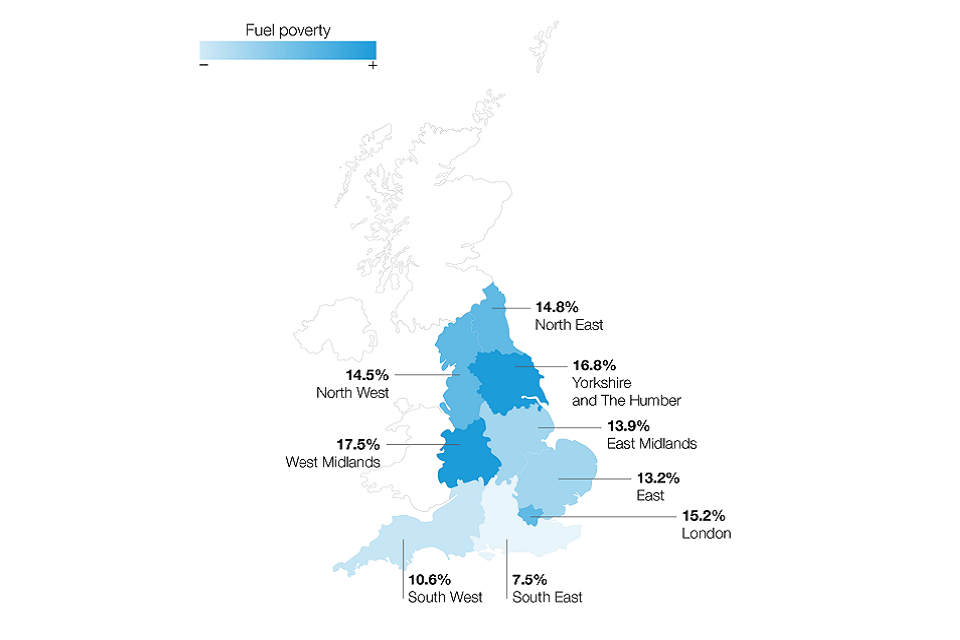

Improving our buildings goes beyond saving carbon. In 2014, government introduced a statutory fuel poverty target for England [footnote 44] to improve as many fuel poor homes as is reasonably practicable to a minimum energy efficiency rating of band C [footnote 45] by the end of 2030. This will mean warmer, healthier homes and lower energy bills. We have also set interim milestones for England, aiming to improve as many fuel poor homes as is reasonably practicable to band E by 2020 and band D by 2025, and in 2019 97.4% of low income households were living in properties with a fuel poverty energy efficiency rating of band E or better. [footnote 46] Our approach to drive energy efficiency improvements in fuel poor households recognises that improving efficiency can help those in fuel poverty afford to keep warm. We published an updated fuel poverty strategy on Sustainable warmth: protecting vulnerable households in England [footnote 47] in February 2021. In this Heat and Buildings Strategy, we consider how we can continue to reduce emissions from buildings while delivering economic and wider benefits, such as tackling fuel poverty and creating new jobs. This strategy builds upon the foundations set by the Ten Point Plan with initiatives such as the Public Sector Decarbonisation Scheme, already supporting 30,000 jobs across the sector since its launch.

The UK’s Presidency of the 26th Conference of the Parties (COP26) under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, which will be hosted in Glasgow in November 2021, provides an opportunity for the UK to showcase the pioneering work being taken forward in the buildings sector, demonstrating our leadership in this sector to other countries. As action to decarbonise the buildings and construction sector is critical to meeting our Paris Agreement goals, we have organised a dedicated Cities, Regions and Built Environment Day on 11 November at COP26, which will showcase ambitious best practice from around the world.

Leading up to COP26 we have published a comprehensive Net Zero Strategy [footnote 48] – a cross-sector strategy that will set out the Government’s vision for transitioning to a net zero economy and making the most of new growth and employment opportunities across the UK. We hope that this strategy, along with other documents that have been and will be released this year, will help to raise UK and global ambition to tackle climate change by decarbonising buildings.

1.4. Devolution and decarbonisation

Decarbonising heat and buildings will require joined-up change throughout the UK, but also represents different opportunities and challenges across the four nations. This section:

- introduces the current devolution arrangements across the UK

- highlights the work of devolved administrations that sit alongside this strategy

To tackle climate change while maximising economic and wider benefits across the UK, collaboration across England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland will be essential [footnote 49]. We will continue to work closely with the devolved administrations, and with local leaders and businesses across the UK, as we develop the policies and proposals set out in this strategy.

Decarbonising our heat and buildings is a joint endeavour across the United Kingdom.

The devolution settlements for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland [footnote 50] are all unique, including some matters relating to heat and buildings policy. [footnote 51]

Given the balance between devolved and reserved competencies, there are opportunities for collaboration and leadership across all nations. Working together and coordinating our efforts where appropriate will help us achieve shared objectives relating to local government, planning, housing, the environment, and electricity and gas policy. In developing this strategy, we recognise that there is great variation across the UK in terms of the building landscape, with differences in the housing mix and the proportion of public sector and commercial and industrial buildings, as well as the activities by businesses. The way we heat our buildings also differs, with a much higher proportion of buildings in England connected to the gas grid than in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. These differences bring different opportunities and challenges for decarbonisation.

In recognition of the different opportunities for emission reductions across the UK, in their publication Net Zero – The UK’s contribution to stopping global warming [footnote 52] (2019), the Climate Change Committee (CCC) recommended that the UK as a whole should reach net zero greenhouse gases by 2050 and that Scotland should reach net zero greenhouse gases by 2045. [footnote 53] In 2020 the CCC also provided a recommendation for Wales to reach net zero greenhouse gases by 2050. [footnote 54]

We have set out the geographic extent of the policies covered in this strategy in the Annex: Current and planned activities.

In addition to UK-wide strategies and policies, devolved administrations have previously developed, or are in the process of developing, their own strategies and detailed policy frameworks to best decarbonise their building stock.

Wales

Heating and cooling networks, but not the regulation of them, renewable energy incentive schemes, and encouragement of energy efficiency are devolved, therefore Wales is responsible for its own heat policy in relation to these matters. Wales’ net zero target is set in legislation alongside a series of 5-yearly carbon budgets (aligned with electoral cycles) and decadal targets.

The Welsh Government published the Energy Efficiency Strategy [footnote 55] in 2016, which set out the 10-year strategy for the period to 2026. The role of decarbonising buildings in delivering carbon targets for Wales is set out in the Welsh Government’s Low Carbon Delivery Plan, Prosperity for All: A Low Carbon Wales [footnote 56],[footnote 57] The next delivery plan for 2021-2025 will be published in November 2021. Welsh Government published a strategy on Tackling fuel poverty 2021 to 2035 [footnote 58] in March 2021.

Scotland

In 2018 the Scottish Government published the Energy Efficient Scotland: Route Map [footnote 59],which set out their plans for Scottish homes, businesses and public buildings to become more energy efficient over the period to 2040. Scottish Government agreed a new policy programme, which includes several actions to decarbonise buildings, [footnote 60] and published a Heat in Buildings Strategy [footnote 61] for Scotland in October 2021. This strategy sets out the longer-term vision and actions being taken to: deliver Scotland’s climate change commitments, maximise economic opportunities, and ensure a just transition which helps to address fuel poverty. The Fuel Poverty Act [footnote 62] (2019) sets statutory targets for reducing fuel poverty, introduces a new definition of fuel poverty, and requires Scottish ministers to produce a comprehensive strategy to show how they intend to meet the targets. The final Fuel Poverty Strategy will be published in due course.

Northern Ireland

In Northern Ireland, a consultation on policy options for a new Energy Strategy [footnote 63] concluded in July 2021. Responses from this consultation have supported the development of a new Energy Strategy, which is due to be published before the end of 2021. The new Northern Ireland Energy Strategy’s vision is to achieve net zero carbon and affordable energy by 2050. The strategy will also provide detail on the strategic direction for decarbonising buildings and heat. Northern Ireland published their Fuel Poverty Strategy [footnote 64] in 2011. The Department for Communities is responsible for developing a new Fuel Poverty Strategy, which will need to reflect a fair and just transition to net zero carbon and the role housing and energy efficiency plays in reducing carbon emissions. To ensure alignment with the content and timeframes of a number of new and emerging strategies in Northern Ireland, responses to the consultation on policy options for a new Energy Strategy [footnote 65], as well as a call for evidence for a new Housing Supply Strategy [footnote 66], will help inform future development of a new Fuel Poverty Strategy.

1.5. Why now?

Given the scale of infrastructural change, and the rate at which we typically renovate our buildings and replace our heating systems, meeting Net Zero by 2050 requires action now to:

- create new, green jobs to boost our economy, drive growth and level up all parts of the UK

- keep us on track to meet our carbon budget and fuel poverty commitments

- raise public awareness and buy-in to change

- build the capacity and capability of markets needed to achieve Net Zero

- drive the evidence and innovation required to inform key infrastructural decisions

Creating opportunities

As well as offering rapid job creation, action on buildings also offers sustained employment opportunities in areas that will be essential for the transition to Net Zero. It is estimated that the UK low-carbon economy could grow more than four times faster than the rest of the economy between 2015 and 2030 and support up to 2 million jobs. [footnote 67] Building on the projections stated in the Ten Point Plan, [footnote 68] we project that the heat and buildings domestic market could support over 175,000 direct and indirect jobs by 2030 and 240,000 by 2035.

We will see job creation across a range of sectors – from manufacturing to services, installation to research and development. While different technologies and different pathways to Net Zero can deliver different social and economic opportunities, in every scenario we expect significant levels of job creation across the whole of the UK.

Meeting targets

The more we can increase the energy efficiency of our buildings, and the sooner we make the switch to low-carbon heating, the greater the reduction in lifetime emissions we can achieve. Delaying action could prevent us from meeting near-term carbon budget and fuel poverty targets, making it harder to achieve our targets in later years by increasing the emissions reductions required.

We want our transition to low-carbon heating to provide social and economic benefits. Our policy paper on Sustainable warmth: protecting vulnerable households in England [footnote 69], published February 2021, sets out our plan to meet our fuel poverty targets while decarbonising housing. [footnote 70] This means that fuel poor households will be among the earliest to benefit from our transition to Net Zero.

Minimising disruption and using trigger points

We plan to transition to Net Zero in a way that minimises disruption and maximises consumer choice. For example, we will look to avoid scrappage and unnecessarily ripping out fully functional heating systems before they come to the end of their lifecycle. We will help smooth this transition by using natural trigger points where possible, such as:

- When people replace heating appliances as they come to the end of their life

- When there are changes to building use or occupancy or ownership

- When building and renovation works are carried out

We know that these trigger points vary across sectors, may not occur very frequently, and take time to produce results – traditional domestic heating systems last approximately 15 years and homes are sold on average every 18 years. Therefore, we need to act now if we are to make the most of these trigger points throughout the 2030s and 2040s.

From 2035, we intend to phase out the installation of new and replacement natural gas boilers [footnote 71] in line with replacement cycle timelines, to ensure that almost all heating systems used in 2050 are low-carbon. [footnote 72]

When a new technology is introduced, it can take time to understand how consumers interact with it, and therefore deployment can start slowly. Some technologies can take more than 30 years to reach near saturation. [footnote 73] Therefore, action to encourage uptake of low-carbon heating and energy efficiency measures (supported by enabling measures and regulation) is needed and are being put in place now, to encourage uptake of deployment by 2050. Whilst we are working on boosting deployment of existing low-carbon products, such as heat pumps and heat networks, in areas that are low-regrets (including new-builds and off gas grid properties), we are also researching whether hydrogen for heating is a viable consumer proposition. By 2026, following trials, we will have more certainty about whether hydrogen for heating is a suitable, low cost and attractive technology, and will take strategic decisions on its role. We will take a gradual approach to ramping up deployment will ensure that consumers have time to prepare themselves for the transition to low-carbon heating, and our long-sighted regulations will give consumers clarity about the direction of travel.

We will also need to introduce minimum building energy performance requirements and start to phase out the worst-polluting fossil fuel heating in the 2020s, so that we can prepare buildings for only installing low-carbon heating systems by the early to mid-2030s. We need to ensure that changes to minimum standards for buildings are communicated well in advance, so that businesses and households have time to prepare.

Building and preparing markets and infrastructure

Supply chains will need time to grow. This decade we will need to prepare and grow the market, so that low-carbon technologies can be deployed across all buildings in the 2030s and 2040s.

To help meet increasing UK demand, we need to begin to scale-up UK production, manufacture and supply. This may range from entire systems to specialised high-value components of low-carbon heating systems, such as heat pump housing and controls, valves and pipework. Growing UK manufacture and supply of heat pumps to over 300,000 units a year by 2028 could increase the rate of installation, grow opportunities for exports, and create more than 10,000 manufacturing-related UK jobs. In consultation with stakeholders, we have therefore identified an ambitious minimum market capacity – to be able to deploy at least 600,000 hydronic heat pumps [footnote 74] per year by 2028 – to galvanise industry to increase UK heat pump deployment. [footnote 75] This is a ‘no-regrets’ target as it is necessary even if hydrogen were to become the primary fuel source for heating buildings.

We also believe that developing the market for low-carbon heat networks will be a no-regrets action, in recognition of the Climate Change Committee’s recommendation for around 18% of UK heat to come from heat networks by 2050 as part of a least cost pathway to meeting net-zero.

Large-scale infrastructure, such as electricity, gas and heat networks, can take time to develop and install. Therefore, we need to take action early to prepare, develop and invest in this infrastructure.

With this preparation and growth, the UK aims to become a world-leader in low-carbon heat and building technologies, bringing new products to the market, industrialising and scaling-up production in the UK. We will look to grow our exports of goods and services, so that the rest of the world can also benefit from UK innovation and expertise.

Informing decisions and future policy

Leaving the decision to invest in hydrogen for heat later than the mid-2020s would bring considerable risk of limiting its potential role. This is because there is a likely need for both major construction and operation of new infrastructure. Therefore, we intend to make strategic decisions by 2026, including whether hydrogen is safe and feasible to use as a heat source and the key enabling steps required.

More broadly, the action we take in the 2020s can be used to test and evaluate different approaches to decarbonisation. This will inform our evidence base, from which we can develop new policies and make informed decisions regarding the best pathway to Net Zero.

We need to start the transition now to meet our emissions reductions targets cost-effectively, minimise disruption and maximise benefits for everyone.

Chapter 2: Economic and wider opportunities

Decarbonising how we heat our buildings will create significant demand for low-carbon technologies and skills. This demand will need to be matched by the key markets manufacturing, supplying and installing these materials and measures. The UK will look to industry to invest here in the UK, to scale-up UK manufacture and production and to share the rewards of UK investment through export opportunities, which will support global decarbonisation efforts and could support over 240,000 jobs across the sector in 2035.

This shift will enable:

- the creation of new specialist low-carbon roles suiting new entrants to the job market

- existing electrical and heating-related professionals, and those in high-carbon industries, to upskill and retrain to acquire jobs in the growing low-carbon market

- investment into increasing the capacity of existing UK-manufactured solutions

- forward-thinking investments into new UK facilities, bringing new technologies to the UK market, with a view to export

- investment into deprived UK regions as part of the levelling up agenda

- improvements to residents’ standard of living and health, reduced costs of bills, and reduced levels of unemployment

- UK leadership, sharing our expertise and technologies with countries across the world

2.1. Green recovery

Setting out the importance, urgency and scale of opportunity for buildings decarbonisation to drive green recovery. The transition to Net Zero represents a huge economic opportunity for the UK. We have the oldest building stock in Europe [footnote 76], which will need to be almost completely decarbonised to meet Net Zero.

We will need to deploy energy efficiency improvements and install new, low-carbon heating systems on an unprecedented scale, creating new employment opportunities across the country, new skills, new and expanded factories, and enabling the UK to seize the benefits of exporting our low-carbon goods and expertise. Work tends to be labour-intensive, so scaling-up delivery supports more jobs per pound spent than in most other areas of the transition.

Upgrading our building stock offers significant benefits beyond jobs and carbon savings: greater comfort, improved health outcomes, and reduced energy bills. These benefits will be felt by households and businesses in all corners of the UK.

The economic benefits of upgrading our building stock have been brought into sharp relief by the COVID-19 pandemic. The Confederation of British Industry [footnote 77], CCC [footnote 78], and International Energy Agency [footnote 79] have all highlighted the importance of decarbonising buildings as part of a post-COVID economic response. An Ipsos MORI survey in April 2020 found that 58% of respondents feel that UK government actions should prioritise climate change in the post-COVID recovery. [footnote 80]

We are dedicating significant government funding to tackle heat and energy efficiency in a way that will boost the economy, improve the lives of individuals, and maximise emission reduction – while minimising the overall public expenditure on Net Zero in the long run. Our full list of activities is included at the end of this strategy, in Annex 2: Current and planned activities for the 2020s.

In his Plans for Jobs speech in July 2020 [footnote 81], the Chancellor set out a suite of measures to support buildings upgrades. This included funding for the Green Homes Grant scheme (of which £500 million was for the Local Authority Delivery (LAD) scheme in England), £1 billion to decarbonise public sector buildings, including schools and hospitals, and £50 million to test innovative retrofitting approaches in social housing.

Further funding for action on buildings in 2021-22 has been made available through the 2020 Spending Review: investing £1 billion to make our homes and public sector buildings greener, warmer and more energy efficient; allocating funding to help some of the poorest households improve their building’s energy performance and switch to low-carbon heating through the Home Upgrade Grant (HUG) in England; and retrofitting social housing as part of the Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund (SHDF).

We also extended the Domestic Renewable Heat Incentive [footnote 82] for an additional year at Budget 2020. The scheme is now due to close at the end of March 2022.

We boosted energy efficiency spending to £1.3 billion [footnote 83], providing an additional £300 million extra funding for home energy efficiency and low-carbon heating upgrades to help lower income households cut emissions and save money on bills, in March 2021. This funding provides an additional £100 million for Wave 1 of the SHDF and £200 million for a third phase of LAD. LAD Phase 3 forms part of a single funding opportunity, alongside £150 million of funding for HUG Phase 1, through the Sustainable Warmth competition. [footnote 84] The competition was launched on 16 June 2021, and we are aiming to grant funding to successful Local Authorities towards the end of 2021, with delivery continuing through to March 2023.

We are boosting funding across schemes to help decarbonisation across the UK building stock, we are investing a further:

- £800 million into the SHDF over financial years 2022/23 to 2024/25

- £950 million into the HUG over 2022/23 to 2024/25

- £1425 million into the Public Sector Decarbonisation Scheme over 2022/23 to 2024/25

- £450 million into the new Boiler Upgrade Scheme over 2022/23 to 2024/25

- £338 million into the Heat Network Transformation Programme over 2022/23 to 2024/25

We remain committed to reviewing and improving our suite of schemes, to deliver the greatest overall benefits to the economy, society, and the environment.

2.2. Jobs

Investing in the green recovery can support up to 240,000 low-carbon buildings-related jobs by 2035, with a huge range of skills and opportunities for new entrants and experienced workers looking to transition to the green buildings sector.

As well as offering rapid job creation, action on buildings also offers sustained employment opportunities in areas that will be essential for the transition to Net Zero. It is estimated that the UK low-carbon economy could grow more than four times faster than the rest of the economy between 2015 and 2030 and support up to 2 million jobs. [footnote 85]

We will see job creation across a range of sectors – from manufacturing to services, installation to research and development. While different technologies and different pathways to Net Zero can deliver different social and economic opportunities, in every scenario we expect significant levels of job creation across the whole of the UK.

Building on the projections stated in the Ten Point Plan [footnote 86], we project that the decarbonisation of the heat and buildings sector, through installing energy efficiency measures, more efficient products and low-carbon heating systems, could support up to 240,000 direct and indirect jobs by 2035.

The efficient products sector already supports the largest number of full-time employment opportunities (about 114,000 FTE) of any sector in the low-carbon and renewable energy economy. [footnote 87] HM Government’s 2019 Energy Innovation Needs Assessment on building fabric estimated that the growth of UK exports in fabric efficiency alone could add over £720 million GVA per annum in the 2030s. [footnote 88]

The increase in deployment of low-carbon heating systems over the coming decade will require industry to rapidly increase the number of trained, high-quality installers. However, social research with installers of heating systems in off gas grid areas of England and Wales (May 2021) [footnote 89] has shown that existing heating installers are likely to retrain in response to growing demand. In addition, the Heat Pump Supply Chain Research Project published in December 2020 has shown how confidence in demand can create jobs by encouraging manufacturers to move operations to the UK or expand existing operations. [footnote 90]

We have demonstrated opportunities for job creation through some of our current policies and projects.

- BEIS estimates that the Local Authority Delivery (LAD) Scheme, Phases 1 and 2, will support on average 8,000 jobs per year in England between April 2020 – March 2022. The Sustainable Warmth competition, covering LAD Phase 3 and HUG Phase 1, will support almost 8,000 jobs between January 2022 and March 2023. [footnote 91]

- One of our whole-house retrofit projects (WHR-104) is estimated to require the equivalent of over 50 FTE to retrofit 100 homes by March 2022. This covers a variety of specialisms, including project management, production and construction, as well as any ongoing maintenance needs.

- The £1 billion Public Sector Decarbonisation Scheme is projected to support up to 30,000 jobs in the low-carbon and energy efficiency sectors. [footnote 92]

Government intends to create jobs by providing a long-term framework for transformational change, which will help UK markets grow. We will look to the market to drive this work forward, while government will seek to provide certainty and stability for businesses by setting clear and timely targets and standards. We will also continue to invest in the development of innovative approaches to decarbonisation, such as hydrogen, and employ a range of enablers to support delivery, including green finance and skills support.

2.3. Skills

Creating the low-carbon workforce we need will require investment in skills – both through retraining the existing workforce and developing the next generation of skilled workers. This section:

- highlights the case for investing in skills

- sets out the ways in which government and industry can work together to achieve it

There are over 140,000 plumbers and heating and ventilation engineers in the UK [footnote 93], there are 114,000 FTE jobs in the efficient products sector [footnote 94], and 2.4 million in construction [footnote 95]. Approximately 80% of people who will be working in the UK in 2030 are already working today. [footnote 96] We know that the transformational change needed to deliver the quantity and quality of building improvements by 2050 will impact those currently working in built environment and heating-related roles, including natural gas engineers.

We predict that, as low-carbon markets’ demand for specialist skills grows, the current need for natural gas boiler installers will reduce. Together with industry, we need to encourage current natural gas engineers, electricians, and those with transferrable skills in complementary sectors, to retrain and specialise in smarter, greener and cleaner technologies. As industry provides new training opportunities for key buildings-related sectors to learn ‘green skills’, this can help preserve and grow key sectors of the economy. [footnote 97] According to a recent Construction Industry Training Board (CITB) survey, approximately 90% of builders stated they would be willing to retrain, as demand for new roles and skills’ changes in the future.

We will use the findings of social research with installers of heating systems in off gas grid areas of England and Wales (May 2021) [footnote 98] and our Heat Network Skills Review Report (September 2020) [footnote 99] to better understand the existing skills base and how we can grow these skill reserves.

In response to advice from the CCC in their 25 June 2020 progress report [footnote 100], we are collaborating between departments and across administrations to ensure skills match the needs of Net Zero. We launched the independent Green Jobs Taskforce [footnote 101] with key industry bodies to deliver 2 million Net Zero jobs by 2030 by producing an action plan for Net Zero skills across a range of sectors. The taskforce will pinpoint the skills needed in the near and long term, create high-quality green jobs and a diverse workforce and manage the transition for those working in high-carbon industries. The action plan for England will be published next Spring.

In October 2020, the Department for Education announced that the National Retraining Scheme [footnote 102] would be integrated with the new £2.5 billion National Skills Fund [footnote 103]. The National Skills Fund will help adults to train and gain the valuable skills they need to improve their job prospects. It will support the immediate economic recovery and future skills needs by boosting the supply of skills that employers require. The National Retraining Scheme includes the Construction Skills Fund, which supports the development of construction onsite training hubs.

We have also made £18 million available to support technical bootcamps for training professionals in clean growth, electrotechnical, welding or engineering. An invitation to tender for skills bootcamps [footnote 104] across England was published in January 2021 and the available bootcamps can be found on our List of Skills Bootcamps [footnote 105].

We are delivering specific policies and funds to support high-quality training, which will enable energy efficient low-carbon heating to be deployed.

- Alongside the Green Homes Grant Voucher Scheme, the Government launched a £6.9 million Skills Training Competition [footnote 106], designed to get tradespeople professionally trained to deliver the Government’s current and future home decarbonisation schemes. Eighteen successful applicants have received funding to train individuals with existing skills and those new to the sector, along with support for installation companies to gain PAS 2030 or MCS accreditation and Retrofit Assessor and Coordinator training. [footnote 107]

- To support delivery of the £1 billion Public Sector Decarbonisation Scheme, we also launched a £32 million Public Sector Low Carbon Skills Fund [footnote 108] to ensure that public sector organisations have access to the expert skills needed to identify, develop and deliver decarbonisation projects.

- As part of BEIS’s £25 million Hy4Heat programme, Energy and Utility Skills has delivered a competence framework for training, accreditation, and registration of gas engineers working with hydrogen. [footnote 109]

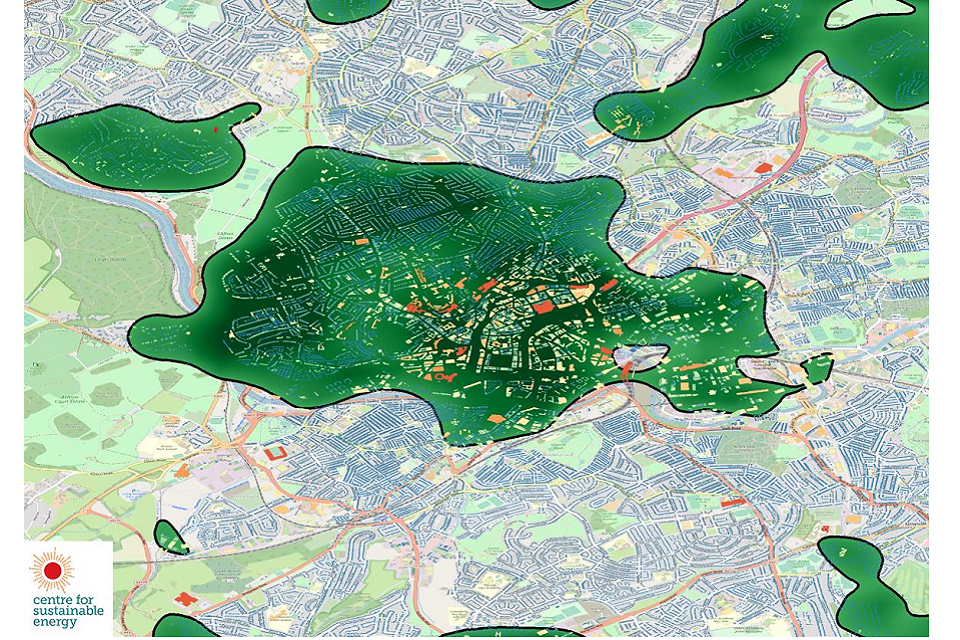

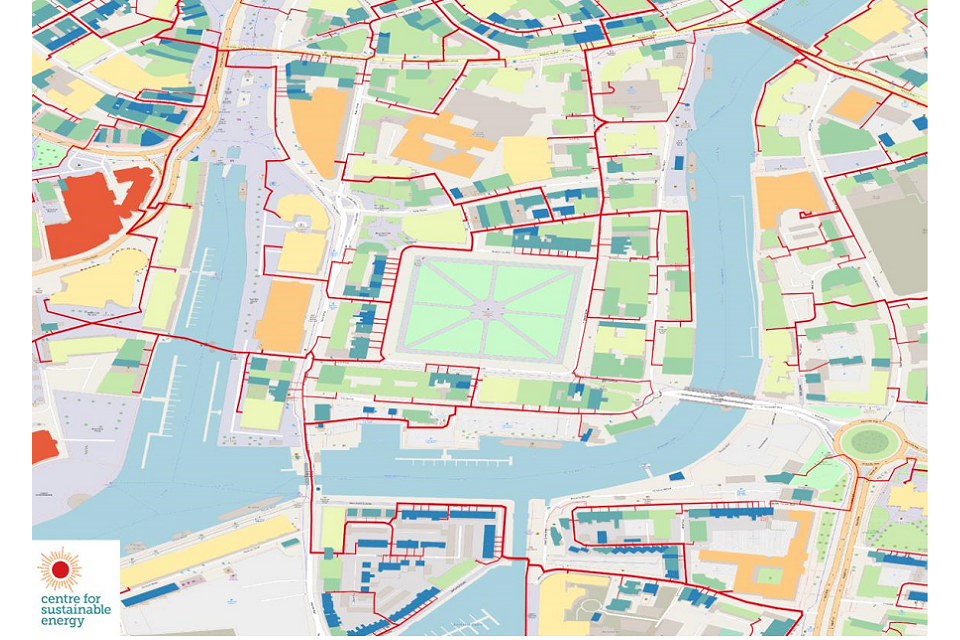

There are many factors we need to consider to ensure that this transition is as smooth as possible and tackle any barriers to training. We understand the importance of encouraging and incentivising attendance at training. The Centre for Sustainable Energy’s Future Proof pilot in Bristol (one of our selected local supply chain demonstration projects [footnote 110]) has partnered with the Green Register to produce a training programme that ensured individuals were paid when they attended training. It saw positive outputs as a result.

We will continue to set quality standards, that can guide and be embedded into training, and provide consumer protection by ensuring workers are sufficiently skilled and delivering the high-quality standard interventions required. Further information on quality standards is detailed in section 6.3 Consumer Protection.

We are committed to communicating signals for investment to provide certainty and stability for businesses to invest in training. We include projections for technology-specific skill demand in the tables on Skills demand per technology-type to provide a clear trajectory for demand.

We will also look to manufacturers to continue to provide quality training to installers. Examples of industry exemplifying the action needed to upskill the workforce include:

- Nordic Heat, LOGSTOR and the Swedish Energy Agency are sharing their expertise with the workforce of Stoke-on-Trent by training over 200 students a year in designing, supplying and installing district heating through a new academy. They are also working with Bridgend County Borough Council, Energy Systems Catapult, innovative heat businesses and the local college to develop an academy to support smart system and heat decarbonisation training and skills in the area. [footnote 111]

- In August 2021, the Heat Pump Association (HPA) launched a new heat pump installation training course for existing heating engineers [footnote 112]. This course can be completed in one week, including a low temperature heating and hot water qualification developed by the Chartered Institute of Plumbing and Heating Engineering (CIPHE). These courses have support from both heat pump and boiler manufacturers.

As well as upskilling the existing workforce, we will also need to attract new entry-level workers. This is partly because, according to the Gas Safe register Decade Review, a significant proportion of the current workforce are nearing retirement age and therefore may be less incentivised to change specialism. [footnote 113] Attracting new entrants to the sector also provides a great opportunity to diversify the workforce.

With this in mind, we are working with the Department for Education to review the existing apprenticeship framework for heating and plumbing and developing a Heat Network Skills Programme to increase the recruitment pool and capability of the workforce for Great Britain. We are working with the Institute for Apprenticeships and Technical Education to convene a sustainability advisory group to:

- encourage trailblazers to align apprenticeships to Net Zero and wider sustainability objectives

- identify which apprenticeships directly support the green agenda

- identify where there are opportunities to create new green apprenticeships

In September 2020, the Prime Minister announced the Lifetime Skills Guarantee. [footnote 114] This was launched in April 2021 and backed by £95 million in government funding in 2021/22. This will provide an opportunity for adults in England without an A-Level or equivalent qualification aged 19 and over to be offered a free, fully-funded college course – providing them with skills valued by employers. This represents a long-term commitment to remove the age constraints and financial barriers for adults looking for their first level 3 qualification. A list of available courses, eligibility and how to apply can be found on GOV.UK. [footnote 115]

Skills demand per technology-type

Building fabric – energy efficiency

| Where we are now | Sparse and inconsistent educational provision for new entrants as thermal efficiency retrofitting does not generally feature in formal skills training. [footnote 116] There are no Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) codes specific to the energy efficiency retrofit sector. A current lack of installers, retrofit assessors, and retrofit co-ordinators is a major barrier to decarbonising the UK’s building stock. According to a Construction Industry Training Board (CITB) survey, approximately 90% of builders stated they would be willing to retrain, as demand for new roles and skills’ changes in the future. [footnote 117] Although one-third of those surveyed stated that their business had not, to date, provided them with any decarbonisation-related training. [footnote 118] |

|---|---|

| Skills required for improving energy efficiency of building fabric | Retrofit jobs are typically undertaken by a combination of highly specialised professionals and generalist builders. Potential skills gap [footnote 119] - Energy efficiency installers, levels 2-4: 105,000 - Energy efficiency assessors, levels 2-4: 15,000 - Retrofit co-ordinators, level 5: 10,000 Estimated training demand timeline (according to CITB) [footnote 120] - 1-4 years: training facilities and courses to 12,000 people per year - 5-10 years: training to 30,000 people per year |

| How we plan to meet this demand | There are British Standards Institution (BSI) standards in place for energy efficiency retrofit. PAS 2030 and PAS 2035 for domestic buildings and PAS 2038 for non-domestic buildings. We will look to incentivise certification to this standard and will work with industry to support training and new routes of entry in key skills shortage areas. There are a wide variety of courses available, some examples include: - Nationally accredited Retrofit Co-ordinator course by the Retrofit Academy [footnote 121] - Online Carbonlite Retrofit course [footnote 122] by the Association for Environmentally Conscious Buildings - Energy Efficiency Measures for Older and Traditional Buildings course, by the Environment Study Centre (quality-assured by CITB, resulting in an award from the SQA) - Green Register also provide a range of ‘middle-level’ courses |

Heat pumps

| Where we are now | According to the Microgeneration Certification Scheme (MCS) database, the UK currently has approximately 1,100 qualified heat pump installing companies. [footnote 123] There are 50,000 F-gas certified installation engineers covering all sectors [footnote 124], however very few in the heat pump sector. To deploy more split heat pump systems [footnote 125], more heat pump installers will need F-gas certification. According to the Gas Safe Register [footnote 126], there are over 130,000 registered gas engineers and our analysis suggests 50% would be willing to retrain to install low-carbon heating systems, if there is sufficient demand. [footnote 127] |

|---|---|