Advancing our health: prevention in the 2020s – consultation document

Published 22 July 2019

Presented to Parliament by the Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Public Health and Primary Care.

July 2019

CP 110

ISBN: 978-1-5286-1545-7

Executive summary

1. Opportunities

The 2020s will be the decade of proactive, predictive, and personalised prevention. This means:

- targeted support

- tailored lifestyle advice

- personalised care

- greater protection against future threats

New technologies such as genomics and artificial intelligence will help us create a new prevention model that means the NHS will be there for people even before they are born. For example, if a child had inherited a rare disease we might be able to diagnose and start treatment while they are still in the womb, so they are born healthy.

Using data held by the NHS, and generated by smart devices worn by individuals, we will be able to usher in a new wave of intelligent public health where everyone has access to their health information and many more health interventions are personalised.

In the 2020s, people will not be passive recipients of care. They will be co-creators of their own health. The challenge is to equip them with the skills, knowledge and confidence they need to help themselves.

We are:

-

embedding genomics in routine healthcare and making the UK the home of the genomic revolution

-

reviewing the NHS Health Check and setting out a bold future vision for NHS screening

-

launching phase 1 of a Predictive Prevention work programme from Public Health England (PHE)

2. Challenges

Over the decades, traditional public health interventions have led to significant improvements in the nation’s health.

Thanks to our concerted efforts on smoking, we now have one of the lowest smoking rates in Europe with fewer than 1 in 6 adults smoking. Yet, for the 14% of adults who still smoke, it’s the main risk to health. Smokers are disproportionately located in areas of high deprivation. In Blackpool, 1 in 4 pregnant women smoke. In Westminster, it’s 1 in 50.

Obesity is a major health challenge that we’ve been less successful in tackling. And clean air will continue to be challenging for the next decade. On mental health, we’ve improved access to services. In the 2020s, we need to work towards ‘parity of esteem’ not just for how conditions are treated, but also for how they are prevented. On dementia, we know ‘what’s good for your heart is also good for your head’. A timely diagnosis also enables people with dementia to access the advice, information, care and support that can help them to live well with the condition, and to remain independent for as long as possible.

The new personalised prevention model offers the opportunity to build on the success of traditional public health interventions and rise to these new challenges.

The NHS is also doing more on prevention. The Long Term Plan contained a whole chapter on prevention, and set out a package of new measures, including:

- all smokers who are admitted to hospital being offered support to stop smoking

- doubling the Diabetes Prevention Programme

- establishing alcohol care teams in more areas

- almost 1 million people benefiting from social prescribing by 2023 to 2024

These measures will help to shift the health system away from just treating illness, and towards preventing problems in the first place.

We are:

-

announcing a smoke-free 2030 ambition, including options for revenue raising to support action on smoking cessation

-

publishing Chapter 3 of the Childhood Obesity Strategy, including bold action on: infant feeding, clear labelling, food reformulation improving the nutritional content of foods, and support for individuals to achieve and maintain a healthier weight. In addition, driving forward policies in Chapter 2, including ending the sale of energy drinks to children

-

launching a mental health prevention package, including the national launch of Every Mind Matters

3. Strong foundations

When our health is good, we take it for granted. When it’s bad, we expect the NHS to do their best to fix it. We need to view health as an asset to invest in throughout our lives, and not just a problem to fix when it goes wrong. Everybody in this country should have a solid foundation on which to build their health.

This is particularly important in the early years of life. Most children are born into safe and loving homes that help them develop and thrive. But this is not always the case. We must help all children get a good start in life.

This ‘asset-based approach’ should then follow through to other stages of life, including adulthood and later life. It’s difficult to live a fulfilling life if you’re worried about money, live in cold or damp conditions, or feel cut-off from those around you.

At national level, we will lay the foundations for good health by pushing for a stronger focus on prevention across all areas of government policy. At local level, we expect different organisations to be working together on prevention. This means moving from dealing with the consequences of poor health to promoting the conditions for good health and designing services around user need, not just the way we’ve done things in the past.

We will:

-

launch a new health index to help us track the health of the nation, alongside other top-level indicators like GDP

-

modernise the Healthy Child Programme

-

consult on a new school toothbrushing scheme, and support water fluoridation

Conclusion

The commitments outlined in this green paper signal a new approach for the health and care system. It will mean the government, both local and national, working with the health and care system, to put prevention at the centre of all our decision-making. But for it to succeed, and for us to transform the NHS and improve the nation’s health over the next decade, individuals and communities must play their part too. Health is a shared responsibility and only by working together can we achieve our vision of healthier and happier lives for everyone.

Introduction

From life span to health span

Thanks to developments in public health and healthcare, we’ve made great progress in helping people to live longer lives. For example, life expectancy has increased by almost 30 years over the past century.[footnote 1] Cancer survival rates are up [footnote 2] and mortality rates from heart disease and stroke are down.[footnote 3]

However, these improvements in life expectancy are beginning to slow,[footnote 4] and over 20% of years lived are expected to be spent in poor health. On average, men born today can expect to live 16 years in poor health. For women, it’s 19 years.[footnote 5]

There is also a clear social gradient to healthy life expectancy. That is, people in deprived areas tend not only to live shorter lives, but they also spend more of those years in poor health. For example, women living in the 10% most deprived areas can expect to live 18 fewer years in good health than those in the 10% least deprived areas.

Figure 1: Female healthy life expectancy at birth and years lived in poorer states of health by national deprivation deciles, England, 2015 to 2017[footnote 6]

Deprivation deciles: 1 = most deprived, 10 = least deprived

| Deprivation decile | Healthy life expectancy | Years lived in poorer states of health | Life expectancy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 52.0 | 26.7 | 78.7 |

| 2 | 56.9 | 23.5 | 80.3 |

| 3 | 59.2 | 22.4 | 81.6 |

| 4 | 61.9 | 20.6 | 82.5 |

| 5 | 64.1 | 19.0 | 83.1 |

| 6 | 65.8 | 17.9 | 83.7 |

| 7 | 66.9 | 17.3 | 84.2 |

| 8 | 68.2 | 16.4 | 84.6 |

| 9 | 68.7 | 16.5 | 85.1 |

| 10 | 70.4 | 15.9 | 86.2 |

Inequalities also exist across a range of other dimensions, including ethnicity, gender, sexuality and having a disability. The underlying causes of these inequalities often cluster together, with people experiencing ‘multiple disadvantage’. There are also certain groups who experience poorer health outcomes than the wider population, such as people sleeping rough, leaving care, and offenders in prison or in the community.

For learning disabilities, autism and other neurodevelopmental or behavioural conditions such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), an early diagnosis can help a child’s development. Specifically, it can help them get the help they need at school, and ensure families and carers can support them better. This in turn helps to improve wider outcomes and prevent needs escalating. But this early diagnosis doesn’t always happen. We also know that adults living with these conditions often have worse mental and physical health than the wider population, and can struggle to access the help they need.[footnote 7]

Risk factors like obesity, smoking and physical inactivity place us at higher risk of both early death and ill-health/disability.[footnote 8] Yet, we know the things that kill us (such as cancer, heart disease and stroke) are not always the same as the things that make us unwell. Some of the most common causes of ill-health are: joint, bone and muscle problems, depression and anxiety, long-term conditions like asthma and diabetes.[footnote 9]

Figure 2: Leading causes of years lived with disability, England, 2017[footnote 10]

| Cause | Percentage of total years lived with disability |

|---|---|

| Musculoskeletal disorders | 22.7% |

| Mental disorders | 14.0% |

| Neurological disorders | 9.0% |

| Unintentional injuries | 6.4% |

| Chronic respiratory diseases | 6.3% |

| Sense organ diseases | 6.0% |

| Other non-communicable diseases | 5.8% |

| Skin and subcutaneous diseases | 5.6% |

| Diabetes and kidney diseases | 4.9% |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 4.4% |

Problems with joints, bones and muscles

For the last 30 years, problems with joints, bones and muscles have been the most common cause of years lived with disability in England.[footnote 11] They affect around 15 million people (1 in 3 adults in England).[footnote 12] They are sometimes called musculoskeletal (or ‘MSK’) conditions. The most common are conditions of musculoskeletal pain, such as osteoarthritis or back and neck pain. Women are more likely to be affected than men.[footnote 13] The risk of having back pain also increases with rising body mass index.[footnote 14] For this reason, the policy priority is helping people to achieve a healthier weight, eat well and stay active.

Osteoarthritis: Nora’s story

Nora used to struggle to cope with the pain of osteoarthritis. Her muscles and joints had become stiffer and more painful, making it harder to enjoy interests like jam-making, gardening and art classes. Nora decided it was time to make some changes to push back against the negative impact arthritis was having on her life.

After taking advice from healthcare professionals and doing online research, Nora started an exercise routine that worked for her, incorporating Pilates, low-impact exercise on a cross-trainer or a bike and swimming.

“My advice to anyone with arthritis is to keep moving. I know everyone says that but take it from me I’ve seen such positive changes in my life since I’ve been exercising. It’s the small things you notice that make the biggest difference to how you feel. For the first time in years I’m able to make jam from the fruit I grow in my garden without taking medication. That means the world to me.”

Depression, anxiety and other mental health problems

Poor mental health is the second most common cause of years lived with disability in England.[footnote 16] The most common conditions are depression and anxiety, which make up the majority of mental health cases.[footnote 17] Approximately 1 in 4 people report living with a mental health issue.[footnote 18] Incidence is highest in the working-age population, and higher in women than men.[footnote 19] Other groups at greater risk include: those living on low incomes, people with problem debt, and those identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender (LGBT).[footnote 20]

Anxiety and depression at work: Helen’s story

Helen was first diagnosed with a mental health condition 15 years ago. After speaking to colleagues at work, Helen now receives the help and support she needs to continue in her role.

“It was around 3 years ago when I suffered panic attacks. I was feeling sick, not wanting to go into work. I had depression as well; you don’t even want to get out of bed, you just want to hide.”

Other long-term health conditions

Together, musculoskeletal problems and mental health conditions account for almost 40% of the total years lived with disability in England. The remaining 60% is split among a number of mainly long-term conditions, such as diabetes, lung conditions like asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), sight loss, hearing loss and dementia.[footnote 22]

In many cases, long-term conditions cluster together. This is sometimes called multimorbidity. There are no official measures, but between 15 and 30% of the adult population are thought to be living with multiple conditions.[footnote 23] Problems are more common in later life, in deprived communities, and among people who are overweight or who smoke.[footnote 24]

Living with multiple conditions: Susan’s story

Susan used to work as a catering manager at a university. She had to stop work in 2008 when she got fibroids, and was bedridden for 2 weeks at a time. Since stopping work, Susan has been diagnosed with osteoarthritis, COPD, hypothyroidism, angina, high blood pressure and high cholesterol, depression and diabetes. She takes 14 different medications every day and her illnesses can feel as though they consume her life.

“I just have to take each day as it comes. Planning doesn’t work.”

The drivers of good health

The good news is that much premature ill-health and disability can be prevented, and there are actions we can take to increase our chances of living longer, healthier lives. Some health conditions we are born with and cannot avoid. Where this is the case, the priority is supporting people to enjoy a good quality of life and to live well.

The mission

Last year, the government set a mission as part of the Ageing Society Grand Challenge[footnote 26] to “ensure that people can enjoy at least 5 extra healthy, independent years of life by 2035, while narrowing the gap between the experience of the richest and poorest”.

The green paper proposals will not deliver the whole ‘5 years’. But they will help us towards achieving this mission. Further details on this will be provided later in the year, through a government response to the green paper.

The mission is based on the technical term ‘disability-free life expectancy at birth’. That is, the time a child born today can expect to live without a limiting health condition: a mental or physical condition that’s long-term and affects day-to-day activities.[footnote 27]

The latest figures for disability-free life expectancy are 62 years for women and 63 for men.[footnote 28] To achieve our mission in England, we will need to increase this to at least 67 for women and 68 for men by 2035. That’s almost 4 months per year. Given that disability-free life expectancy has remained stable in recent years,[footnote 29] this is likely to be extremely difficult, and will require bold action.

Much has been written on the factors that shape our health. As set out in the Prevention Vision, evidence suggests there are 4:

- the services we receive (Chapter 1)

- the choices we make (Chapter 2)

- the conditions in which we live (Chapter 3)

- our genes, which we inherit from our parents

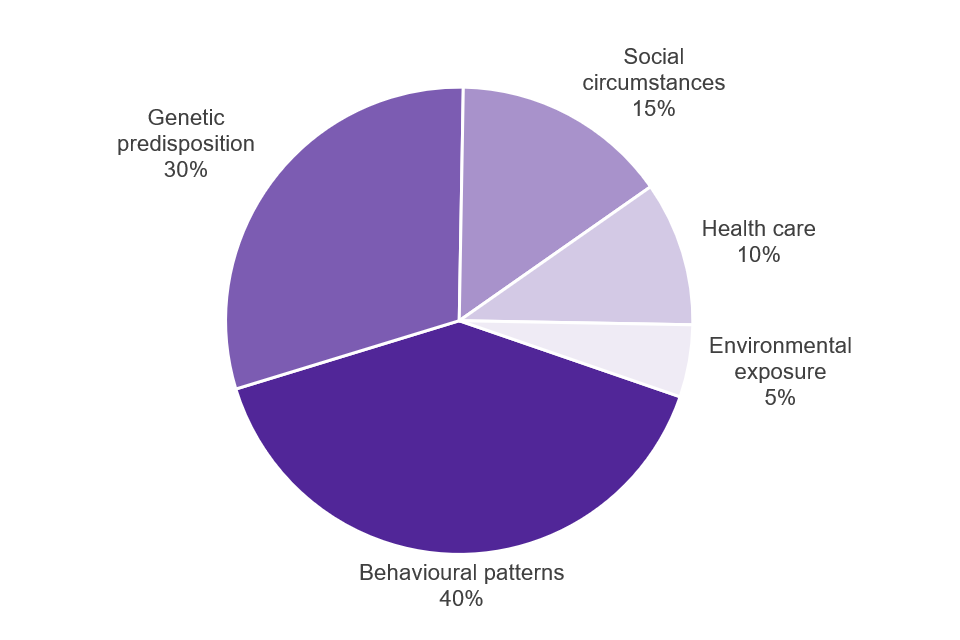

Figure 3: Determinants of premature mortality and their contribution (McGinnis and others, 2002)[footnote 30]

Genetic predisposition, 30%; social circumstances, 15%; health care 10%; environmental exposure 5%; behavioural patterns, 40%

The contribution of health determinants to premature mortality from a study by McGinnis and others, 2002: behavioural patterns 40%, genetic predisposition 30%, social circumstances 15%, healthcare 10%, environmental exposure 5%.

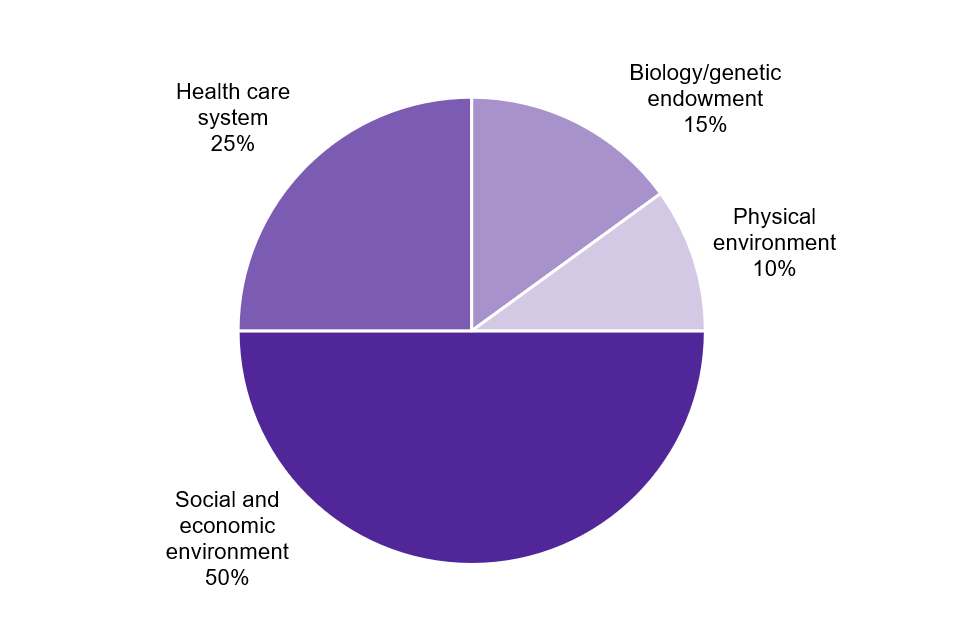

Figure 4: Estimated impact of determinants on health status (Canadian Institute of Advanced Research, 2002)[footnote 31]

Health care system 25%; biology/genetic endowment 15%; physical environment 10%; social and economic environment 50%

The contribution of health determinants to health status from a study by the Canadian Institute of Advanced Research, 2002: social and economic environment 50%, healthcare system 25%, biology/genetic endowment 15%, physical environment 10%.

There are different views about the contribution made by each, which is likely to vary from person to person and from disease to disease. Nevertheless, most people agree that the choices we make, shaped by the conditions in which we live, have the biggest impact. The focus of this green paper is on services, choices and conditions.

If we are to achieve our mission, we need to take bold action in all areas: making the most of the opportunities in front of us and being open to innovations ahead. This includes:

- bringing in a new wave of intelligent public health, which is more proactive, predictive and personalised, while also taking tough action on our biggest challenges: smoking, obesity and mental ill-health[footnote 32]

- taking a behavioural science approach to some of our biggest challenges on prevention. This means making healthy choices as easy as possible for people, and, in some cases, making all options healthier

- viewing health as our most precious asset, and not just a problem to fix when it goes wrong. Good health is the foundation of happy families, thriving communities, and a strong economy. When our health is good, we take it for granted. When our health is bad, we expect the NHS to do their best to fix it. We need to lay the foundations for good health so everyone has a chance to live a healthy and happy life

Chapter 1: Opportunities

Intelligent public health

In today’s increasingly digital world, technology and data have a clear role to play in helping us to deliver more proactive, predictive and personalised services to people. We’ve already taken the first steps in doing this.

PHE’s social marketing campaigns already personalise lifestyle advice to different audiences, with 90% of their social media messaging on smoking being seen by people who smoke. That’s modern, efficient and focused prevention in action.

The future is even greater personalisation and a closer fit with individual needs. There will always be a place for interventions that improve everyone’s health. But it can be less intrusive and better value for money to offer people more personalised and tailored support. Many are already opting in to this kind of approach. In the next decade, intelligent public health will mean:

- focused support and advice to those who need it and choose to participate

- precision medicine

- tackling current and future threats

Predictive prevention

Starting this year, PHE will work together with NHSX and other partners across the public health system, academia, industry and the voluntary sector to build a portfolio of new innovative projects that will help us evaluate and model Predictive Prevention at scale.

Phase one of the programme includes:

-

getting the foundations right by building trust with the public about how data can be used to improve their experience, and the benefits of participating

-

refining our overall approach to analysis and insight generation to help us understand and support the most at-risk and vulnerable groups

-

developing exemplar projects to prove the concept of personalised prevention and establish the evidence base

-

designing the future shape of the programme, with a view to increasing the scale and ambition

Use of data: a citizen’s view

The data we generate about our health, our activities, our genomes and our environment can empower us in unimaginable ways. We can tailor our diet to meet our metabolism, we can account for air pollution in our exercise plans, and we can take action to prevent painful diseases decades before they would begin. And we know this is only the beginning.

Finding insights in this data is an ongoing challenge, one that can be met on our phones and tablets, in the GP surgery or nationally, at a population level. We are entering a new era of evidence-based self-care, driven by us as patients in partnership with the NHS.

PHE and the NHS use data and insights to create these algorithms and models, and the public can have a role in this if we choose to help by either allowing our phones and devices to send data, or by allowing PHE and the NHS to access our anonymised clinical data. There is some indication from PHE’s targeted marketing campaigns that citizens are willing to share their contact details to receive information, and to have an ongoing dialogue around health issues relevant to them. To date, there have been over 7.1 million responses to this type of offer from PHE. The UK Biobank has also been able to build a record of the data of over half a million volunteers.

To make this work, PHE and NHS organisations will ensure that they respect and protect our data. They will focus on the requirements of the General Data Protection Regulation and Data Protection Act 2012, adhere to the Caldicott principles and implement Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) policy on patient preferences. At all stages, they will work closely with the Information Commissioner’s Office, the National Data Guardian, the new Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation, and academics and other experts in information governance.

They will work closely with the public, privacy organisations and other relevant bodies including the Information Commissioner’s Office and the Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation, to understand what we consider to be acceptable use of our data. They will also explore developing models of dynamic, informed consent, so we can choose how and when we want to share our personal data for this purpose.

The impact achieved will be constantly evaluated in the open, with regular and transparent engagement with the health sector and the public – ensuring that individual interventions are having a positive impact overall, and that we are narrowing the gap between richest and poorest.

Some of the most exciting opportunities for intelligent prevention are those that can be developed locally, including as part of devolution areas that have a broad focus on economic development alongside a commitment to improve health. The learning from these experiences can be shared more widely to enable other areas to benefit.

In support of this ambition, the government is exploring ways to support a West Midlands Combined Authority Radical Prevention Fund. This will involve a programme of work to explore, test and learn from new opportunities to prevent ill-health using the latest technology – stimulating innovation in ways that can support both health and wealth.

Case study: Digital Diabetes Prevention programme

From August 2019, there will be a digital way to take part in the Healthier You: NHS Diabetes Prevention Programme. The digital version gives the same advice on healthy eating, exercise and weight management as the face-to-face programme, but through wearable technologies, apps and websites. It is designed for those at risk of type 2 diabetes who find it difficult to attend sessions because of work or family commitments. Early analysis from pilots involving over 4,000 people shows the digital programme is reaching more people of working age.

Andrew, a 51-year-old farmer from North Yorkshire, took part in the pilot. This helped him lose weight and reduce his blood sugar levels out of the pre-diabetic range. He said:

“It’s given me a helping hand in the right direction. I get a video message from my personal health coach a couple of times a week with diet recommendations and fitness techniques personalised to me and my lifestyle plan. I send a text back and we keep up the conversation digitally. I also like reading the comments and conversations on the online community.”

The NHS is also working to give more people access to digital ways to manage their diabetes, including through an online ‘healthy living for people with type 2 diabetes’ support tool, and by investing £2 million into a new NHS Test Bed programme. Last year (2018), NHS England also launched a guide on NHS UK for managing type 1 diabetes.

Focused support and advice

In the future, the support and advice we provide to people will become much more focused and tailored. We will start this transformation with 2 of our largest existing programmes – screening and NHS Health Checks.

Intelligent screening

Screening programmes have long been used to identify those at risk of or already living with health problems. By preventing conditions – or detecting them at more treatable stages – it’s possible to save lives and improve outcomes.

Our vision for future screening in the NHS is for:

- uptake to be maximised, including by making screening easier for people to access, and tackling unjustified variations in take-up

- existing national screening programmes to become more personalised and stratified by risk, so we focus interventions where they are most needed. For example, reviewing the case for increasing cervical screening intervals for lower-risk groups, such as women vaccinated against human papillomavirus. We also know that the predictive power of a screening test is increased if you identify high-risk groups, rather than screening everybody

- focused screening within high-risk populations to be offered for a greater range of conditions. For example, considering introducing lung cancer screening to high-risk individuals, such as smokers, together with more personalised ongoing support

- better use of technology, including an expansion of our offer on genomics, better use of data and embedding the use of artificial intelligence. This includes incorporating genetic testing into screening and diagnostics. For example, using next generation sequencing to confirm cases of cystic fibrosis in children (currently being tested in the newborn bloodspot programme), or screening for genes associated with Lynch syndrome, which leads to an increased risk of bowel cancer

- recommendations to be developed in a co-ordinated way across different kinds of screening opportunity, while continuing to be based on the best evidence and advice. For example, by reviewing how the different sources of expert advice on screening, in particular the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the UK National Screening Committee (UK NSC), relate to one another

- faster implementation of recommended interventions and programmes, with clear accountability for delivery and investment in supporting IT

Professor Sir Mike Richards is currently carrying out a review of cancer screening. The report is due to be published in September 2019. This provides a good opportunity to update and modernise our approach to screening.

We recognise that there are challenges in the existing screening arrangements, and that reform is needed to achieve our vision for the future. Recommendations from the review will help shape our plans for change, supported by a strategic review of IT required to enable our vision for future screening. NHSX will lead on this element of the screening strategy.

We also recognise that there remains variation in screening outcomes across the country, and by deprivation and ethnicity. As part of our response to Public Accounts Committee (PAC) recommendations, we will set out our understanding of the variation in performance and a plan for reducing these inequalities. We are due to respond to these recommendations in July.

Intelligent health checks

NHS Health Checks is a national programme commissioned by councils. Health Checks offer people aged 40 to 74 a free check-up of their overall health, every 5 years. The results can tell people whether they are at higher risk of developing certain health problems, such as heart disease, diabetes, stroke and dementia. They help underpin the NHS Long Term Plan commitments to prevent 150,000 heart attacks, strokes and cases of dementia, and to double the NHS Diabetes Prevention Programme.

Case study: Southwark Digital Health Check tool

Southwark Council developed an online digital health check tool to help more people benefit from the NHS Health Check programme. People who had already been offered an NHS Health Check, but had not responded, were sent a text message inviting them to access the digital check.

A third of the people accessed the digital check. Half of these completed it to find out their chance of having a heart attack or stroke in the next 10 years. More than 1 in 10 of those using the digital check were found to be at high risk of having a heart attack or stroke and so went on to complete a face-to-face NHS Health Check. These important checks focus on the leading causes of premature death and ill-health such as obesity, smoking, high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes, therefore offering people the chance to lower or manage their risk.

The NHS Health Check programme has achieved a lot. But uptake varies across the country,[footnote 33] the risks identified in a check could be followed up more consistently by the NHS, and evidence is emerging that people could benefit from a more tailored service.[footnote 34] There may also be a case for a particular focus on supporting people through key changes in their life, in particular thinking about future care needs and how they can remain healthy and active in older age.

Building on the gains made over the last 10 years, we believe the time is right to take a step back and consider whether changes to the programme could help it deliver even greater benefits. The government will commission an evidence-based review of the NHS Health Checks programme to maximise the benefits it delivers in the next decade.

Details will be confirmed later this year, but the scope is likely to include:

- ways of increasing uptake, particularly among high-risk groups

- options for making it more focused, for example identifying people on the basis of information about their likely risks, rather than making the same offer to everyone. This could mean more support to those who need it most

- considering how it’s delivered, for example using developing digital service offers to intervene in a more efficient and tailored way

- reviewing what’s covered in an NHS Health Check, for example increasing the range of health and care advice that checks can offer

- reviewing the evidence for a specific ‘MOT’ when approaching retirement age to help prevent or delay future care and support needs

Precision medicine

Genomics is changing the future of health and medicine. From providing more tailored cancer treatments to helping diagnose unknown conditions, it will underpin a new era of precision medicine. Over the next decade, we want to build on our position as a world leader in genomics and make the UK the number one destination to research and develop the latest scientific advances in genomic healthcare.

How genomics works

The human genome is made of DNA and is the ‘instruction manual’ for how our bodies come into existence, maintain our cells, and ultimately die. It is the unique blueprint that makes every person different from every other, and tiny variations in the genome can have significant impacts on our life and health. Sequencing these variations can help doctors identify people at risk of developing treatable diseases, speed up diagnoses and find effective personalised treatments that deliver better results with fewer side effects.

For the last 70 years, the UK has been at the forefront of the use of genetics to improve healthcare. However, it’s only in the last 10 years, with advances in science and technology, that we have begun to unlock the wider potential. We have led the way globally with initiatives like the 100,000 Genomes Project, which was led by Genomics England and is the largest national sequencing project anywhere in the world. This project is already making a real difference for patients. Early results show 1 in 4 rare disease patients previously without a diagnosis now receive one, and up to half of cancer patients could be provided with findings that put them and family members on a better care pathway.

Later this year, Genomics England and the NHS will start returning results of additional findings related to preventable conditions to participants who have chosen to receive them. These may be available based upon follow-up analysis of their samples.

The Genomic Medicine Service in the NHS is the first of its kind in the world to integrate whole genome sequencing into the healthcare system. It aims to deliver equitable access to genomic testing to help more accurately diagnose disease and personalise treatments and interventions. Our partnerships with researchers, industry and governments, domestically and internationally, all contribute to advancing this area.

Genomic approaches will be transformative for early detection of many of the common diseases and cancers. Opportunities to understand how best to realise these benefits will be explored as part of plans to sequence 5 million genomes by 2023 to 2024, through a unique collaboration between the NHS, UK scientists and industry.

Genetic risk in healthy populations

We know genetic factors play a role in human health and disease, including most major chronic diseases. For some diseases, many thousands of genetic variations across our genomes each have a small impact on the chance that we will develop some common diseases. It is now possible to combine this genetic information from many people into polygenic risk scores (PRS), which identify those at highest risk of particular diseases. This could allow individuals to make lifestyle changes that will help prevent disease or reduce its impact, lead to more effective prescription medicines and improve other public health interventions.

PRS could also help to define new, currently invisible, patient populations. This could, for example, include people at risk of heart disease who would benefit from receiving statin therapy but who are currently not receiving preventative treatment because their blood pressure and cholesterol levels are normal. As the evidence develops, complementing existing risk scores (such as the QRisk Score for cardiovascular disease) with this kind of genetic information will be a priority for the UK healthcare system.

Building on recent advances realised through UK BioBank, the clinical implementation of this approach will be pioneered at scale in the new Accelerating Detection of Disease (ADD) challenge, which aims to recruit up to 5 million healthy participants into a world-leading research cohort in order to shed new light on the detection and treatment of common diseases. A key part of the ADD challenge will be to offer as many participants as possible their PRS. Individuals will volunteer their genetic information, which will be used in accordance with relevant legislation, regulation and good practice guidance on use of data, in order to develop and improve the evidence base for the use of PRS.

The goal of the ADD challenge will be to support research, prevention and treatment across major chronic diseases, including cancer, dementia, heart disease and mental health conditions. The project will seek to enrol under-represented groups, such as ethnic minorities, to enable a better understanding of disease and preventative measures for every individual in society and reduce existing health inequalities. The project brings together the NHS, industry and leading charities including Cancer Research UK, the British Heart Foundation and Alzheimer’s Research UK. It will be the largest ever study of its kind, collecting a broad range of data from healthy volunteers over many years.

We will be publishing a National Genomics Healthcare Strategy in autumn 2019. This will set out how the genomics community can work together to make the UK the global leader in genomic healthcare.

We have an ambition to embed genomics in routine healthcare and make the UK home to the genomic revolution that’s on the horizon.

By 2023 to 2024, the UK will aim to carry out 5 million genomic analyses, including sequencing at least one million whole genomes from patients in the NHS and participants in the UK Biobank.

Some of these genomic analyses will be provided by the ADD challenge, which will now incorporate the government’s commitment to develop a genomic volunteer service and will be free to participants.

This year, seriously ill children who are likely to have a rare genetic disorder, children with cancer, and adults suffering from certain rare conditions or specific cancers will be offered whole genome sequencing as part of their routine care. This will put the UK at the cutting edge of genomic technologies to predict and diagnose inherited and acquired disease, and to personalise treatments and interventions.

Case study: Whole genome sequencing

Genome sequencing has the potential to dramatically improve the speed of diagnosis and influence the treatment plans for children with rare childhood conditions. The Next Generation Children Project led by clinical researchers in Cambridge used whole genome sequencing to help doctors identify genetic diseases in 350 babies receiving intensive care at Addenbrooke’s Hospital.

The study showed that the diagnosis and treatment of some of the most critically ill babies can be improved by sequencing their whole genome. A diagnosis was provided in 2 to 3 weeks instead of around 3 to 6 months and identified a quarter of the babies as having an underlying genetic condition. The diagnosis also changed the treatment plans for three-quarters of the babies which often saved the need for further tests.

Tackling current and future threats

Antimicrobial resistance

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is one of the most pressing global challenges we face this century. If no action is taken, up to 10 million people per year could die worldwide. This would make drug-resistant infections a bigger killer than cancer currently is now over the next 30 years.[footnote 35] AMR is already estimated to contribute on average to over 2,000 deaths annually and cost the NHS approximately £95 million each year in the UK.[footnote 36]

In recognition that there are no ‘quick fixes’, the UK government set out its longer-term vision of a world in which AMR is contained and controlled by 2040, supported by a 5-year action plan. This covers actions across human and animal health, addressing infection prevention, use of antimicrobials, increasing the availability of clean water, and minimising spread through the environment and food.

Tackling sepsis

Our recent focus on sepsis has meant better awareness and improved recognition of symptoms among clinicians, with more people being correctly diagnosed. At the same time, as we face the possibility of a world without effective antibiotics, it’s critical that we conserve our antibiotics so that they remain effective when they are really needed.

The UK’s 5-year national action plan for AMR includes the commitment to develop a real-time patient-level data source of patients’ infection, treatment and resistance history that will be used to inform their treatment and the development of interventions to tackle severe infection, sepsis and AMR.

But the UK cannot tackle AMR alone. Global problems require global solutions. That’s why One Health co-ordinates action in all sectors, across the world. In the UK, we continue to play our part globally by modelling best practice, sharing this good practice with other countries, and supporting international efforts.

To maintain the UK’s position as world leaders on AMR and to deliver international action, we have appointed Professor Dame Sally Davies as the UK Special Envoy on AMR.

As an international expert, Dame Sally will support the UK government on the delivery of their 5-year AMR action plan while working with the World Health Organization, World Organisation for Animal Health, Food and Agriculture Organization and the United Nations to maintain momentum on the global stage. Dame Sally will work across all sectors and advise on the delivery of a ‘One Health’ response to AMR including health, agriculture and the environment.

A new model for the evaluation and purchasing of antimicrobials in the UK

The national action plan includes a commitment to testing solutions that address the failure of companies to develop new antimicrobials. We’re the first country in the world to announce that we’ll test new, innovative models to pay companies for antibiotics based on their value to the NHS, not volumes used. We hope this will send a strong signal to the rest of the world that testing models to incentivise the development of new, vital medicines is of great importance.

The UK represents only a small part of the global market for these drugs. For this to have the full effect, we need other countries to offer similar incentives in their own domestic markets. We hope that by leading the way and promoting the project internationally, they will do just that.

Immunisations

Vaccinations are one of the most cost-effective health interventions.[footnote 38] Not only are there substantial health gains – saving lives, protecting vulnerable groups and reducing disability – but they also reduce pressure on the NHS and improve productivity.[footnote 39] Despite this, there’s been a gradual decline in vaccine uptake in recent years, with too many people not getting the vaccines they need for themselves or their children.[footnote 40]

By spring 2020, we will launch a Vaccination Strategy, to maintain and develop our world-leading immunisation programme. The strategy will include action on:

-

Operational work to increase uptake of all recommended vaccinations across all communities and areas, to include the medium-term aim of reaching over 95% uptake for childhood vaccinations and continuing to increase uptake of the seasonal influenza vaccine. This includes implementing the UK measles and rubella elimination strategy to increase uptake of the second dose of the MMR vaccine to at least 95%, to match the aspiration for the first dose.

-

Enhanced use of local immunisation co-ordinators and primary care networks, ensuring the right mechanisms are in place to increase uptake (through the GP Vaccines review) including consistent application of call and recall, and improved data services.

-

Continued evolution of our immunisation programme, incorporating new, more effective and cost-effective vaccines and new uses for existing vaccines across the life course, as advised by our expert group, the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation.

The government will also continue to emphasise the preventative value of vaccines at every opportunity. This is to ensure that people have the facts they need, and that vaccine misinformation is addressed as effectively as possible.

Chapter 2: Challenges

When it comes to living a healthier life, the modern world presents many challenges. It can feel like the odds are stacked against us. This is particularly the case if you’re living on a low income or have a serious mental illness or learning disability. This green paper is not about nannying, but empowering people to make the decisions that are right for them. It’s about providing everyone with the chance to live happy, healthy lives.

By taking a few actions, we can reduce our chances of developing arthritis, dementia, diabetes and various other health conditions. This applies to people of all ages. Evidence suggests our biggest challenges are: being smoke-free, eating a healthy diet and staying active, and taking care of our mental health.[footnote 41]

Figure 5: Leading risk factors of years lived with disability, England, 2017[footnote 42]

| Risk factor | Percentage of total years lived with disability |

|---|---|

| High body-mass index | 6.4% |

| Tobacco | 5.9% |

| High fasting plasma glucose | 5.5% |

| Occupational risks | 3.3% |

| Dietary risks | 3.1% |

| High systolic blood pressure | 2.3% |

| Drug use | 2.3% |

| Alcohol use | 2.2% |

| Child and maternal malnutrition | 1.9% |

| Air pollution | 1.5% |

Being smoke-free

There has been good progress in moving towards a smoke-free society. Over the last 35 years, smoking rates in Great Britain have halved.[footnote 43] We now have one of the lowest rates in Europe,[footnote 44] with fewer than 1 in 6 adults smoking.

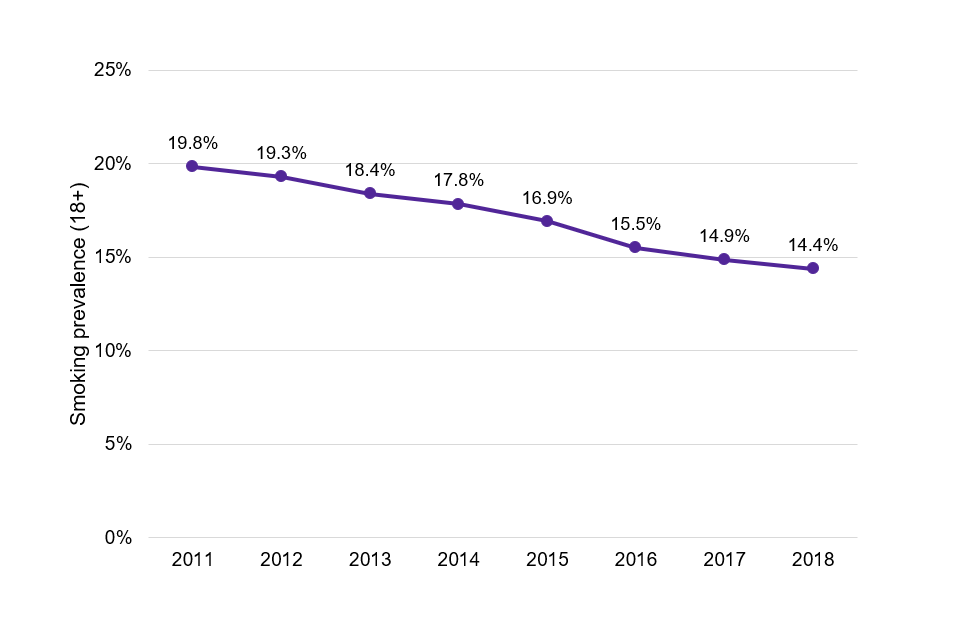

Figure 6: Adult smoking prevalence in England, 2011 to 2018[footnote 45]

19.8% in 2011; 19.3% in 2012; 18.4% in 2013; 17.8% in 2014; 16.9% in 2012; 15.5% in 2016; 14.9% in 2017; 14.4% in 2018

Chart showing that smoking prevalence rates among adults in England have declined from 19.8% in 2011 to 14.4% in 2018.

This remarkable change is the result of decades of concerted effort and government action. We were one of the first countries to ban smoking in public places (2007), we established education campaigns like Stoptober (2012), and introduced plain packaging for cigarettes (2016). Recently, the government also published a tobacco control plan, which included the goal of reducing smoking rates to 12% in adults by 2022.

The gains in tobacco control have been hard-won, and there’s still much to do. For the 14% of adults who are not yet smoke-free,[footnote 46] smoking is the leading cause of ill-health and early death, and a major cause of inequalities.[footnote 47] That’s why the government wants to finish the job.

We are setting an ambition to go ‘smoke-free’ in England by 2030.

This includes an ultimatum for industry to make smoked tobacco obsolete by 2030, with smokers quitting or moving to reduced risk products like e-cigarettes. Further proposals for moving towards a smoke-free 2030 will be set out at a later date.

This goal is extremely challenging. Although smoking rates are falling overall, they remain stubbornly high in certain groups, including:

-

in areas of deprivation. In Blackpool, 1 in 4 pregnant women smoke. In Westminster, it’s 1 in 50.[footnote 48] Rates are also higher among manual workers and social renters[footnote 49]

-

among people who identify as LGBT[footnote 50]

-

among people living with mental health conditions. A joint report from the Royal College of Physicians and the Royal College of Psychiatrists suggests that 1 in 3 cigarettes in England are smoked by somebody with poor mental health[footnote 51]

Tackling these inequalities is the core challenge in the years ahead. If we are to achieve this vision of a smoke-free future, we need bold action to both discourage people from starting in the first place, and to support smokers to quit.

Case study: Salford ‘Swap to Stop’

Social housing tenants are much more likely to smoke: 30% of adults in the social rented sector are estimated to be smokers, double the national average.

As part of comprehensive local action on smoking, Salford city council worked with a local housing association, stop smoking service, pharmacies and a registered vape shop on the Salford ‘Swap to Stop’ project, aimed at social housing and privately rented tenants in some of the most deprived areas in the city. A free e-cigarette starter-pack was given as well as behavioural support to quit smoking. Demand was high: over 1,000 smokers were recruited in 10 weeks, of whom 20% quit smoking altogether.

Discouraging people from starting

Two in 3 people who experiment with smoking go on to become smokers. Discouraging young people from trying cigarettes is an important priority.[footnote 53] In 2007 the government raised the age of sale for tobacco from 16 to 18. This helped contribute to lower teenage smoking rates, and forms part of wider government action to deter people from starting in the first place, including bans on:

- television advertising (1985)

- printed advertising (2003)

- sponsorship (2005)

Supporting smokers to quit

Help to quit is mostly delivered by the NHS or local authorities, paid for through general taxation. Given the pressure on local budgets, the government is considering other ways of ensuring people can get the help they need.

Other countries, such as France and the USA, have taken a ‘polluter pays’ approach requiring tobacco companies to pay towards the cost of tobacco control. We’re also open to other ideas for funding, including proposals to raise funds under the Health Act 2006.

We would aim to use any funds to focus stop-smoking support on those groups most in need, such as pregnant women, social renters, people living in mental health institutions, and those in deprived communities; and to crack down on the illicit tobacco market by improving trading standards enforcement.

We also believe that there could be a positive role for inserts in tobacco products giving quitting advice and will consider this as part of our review of tobacco legislation once we leave the European Union.

The government is committed to monitoring the safety, uptake, impact and effectiveness of e-cigarettes and to assess further innovative ways to deliver nicotine with less harm than smoking tobacco. There is a large amount of research now available to support e-cigarette use as a safer alternative to smoking and help people quit smoking, and we continue to monitor the evidence. There are also claims that heated tobacco products could be less harmful than smoking and help smokers quit. Heated tobacco products are relatively new to the UK market in comparison with e-cigarettes, and research is in its infancy and mainly led by the tobacco industry.

The latest evidence on heated tobacco (given by the independent Committee on Toxicity in December 2017 and in the February 2018 PHE evidence review)[footnote 54] stated that heated tobacco products still pose harm to users, but may be less harmful than smoking conventional cigarettes. Information on the impact on health is very limited and we recommend that smokers quit completely rather than move to these products.

As part of our commitment to evaluate the evidence on new products, we will run a call for independent evidence to assess further how effective heated tobacco products are, or are not, in helping people quit smoking and reducing health harms from smoking. We’ll keep the evidence on e-cigarettes under review.

Maintaining a healthy weight

For other areas, the trend is going in the wrong direction – with only a third of adults a healthy weight. Since 1993, rates of adult obesity have almost doubled (to 29%), and morbid obesity has quadrupled (to 4%)[footnote 55]. One in 3 children aged 10 to 11 are now overweight or obese and we know that obese children are 5 times more likely to become obese adults.[footnote 56]

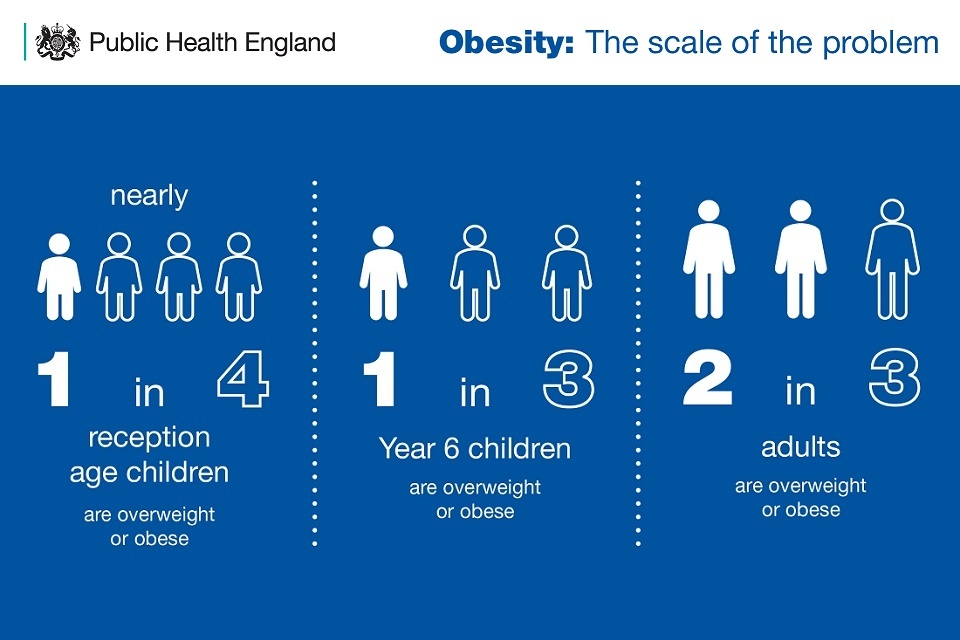

Figure 7: Obesity – the scale of the problem[footnote 57]

Nearly 1 in 4 reception age children are overweight or obese; 1 in 3 Year 6 children are overweight or obese; 2 in 3 adults are overweight or obese

Nearly 1 in 4 reception age children, 1 in 3 year 6 children, and 2 in 3 adults are overweight or obese.

This is storing up health problems for the future, and is a cause for serious concern. This is because being overweight or obese is a major risk factor for a number of conditions, including diabetes, heart disease and stroke, and some cancers.[footnote 58] Improving our diet is one of the biggest health-related actions we can take to improve the health of the nation.[footnote 59]

Eating a healthy diet

As a country, we need to eat more fruit, vegetables, fibre and oily fish. We consume too many calories, as well as too much sugar, saturated fat and salt.[footnote 60] We know it can be difficult to eat healthily when unhealthy options are all around us. That’s why our focus must be on making healthier choices easier. This is not nannying, but reshaping the environment to provide people with more choice, not less.

We have demonstrated through our childhood obesity plan our commitment to take bold action. That’s why our plan for reducing childhood obesity by 50% by 2030 has focused on making the food and drink available to families healthier.

Energy drinks are soft drinks that are typically distinguished by their significantly higher caffeine content. Although diet versions are available, regular energy drinks on average contain more calories and sugar than other regular soft drinks.

Research has suggested that excessive consumption of energy drinks by children may affect some children adversely. In addition, energy drink consumption has also been associated with unhealthy behaviours and deprivation.

Last year we consulted on ending the sale of energy drinks to children. The consultation showed overwhelming public support, with 93% of consultation respondents agreeing that businesses should be prohibited from selling these drinks to children. Teachers and health professionals, in particular, were strong in their support for the government to take action.

Therefore, we can now announce that the government will end the sale of energy drinks to children under the age of 16.

We will be setting out the full policy in our consultation response shortly.

We have also consulted on making calorie labelling mandatory in the out-of-home sector, such as restaurants, takeaways and cafes. We will be setting out details of our policy in a consultation response shortly. In addition, we set out our intention to, and consulted on, banning promotions of foods and drinks high in fat, sugar and salt (HFSS) by price and by location. We have also consulted on introducing a 9pm watershed on TV advertising of HFSS products and similar protection for children viewing adverts online. We will be setting out the government’s response and next steps on both policies as soon as possible.

In Chapter 2 of our childhood obesity plan, we committed to deliver a Childhood Obesity Trailblazer Programme in partnership with the Local Government Association and PHE, working with local authorities to test the boundaries of their levers through innovative local action to tackle childhood obesity. Where we live has a huge role to play in tackling childhood obesity, whether it is the way our towns and cities are designed to ensure greater active travel or safe physical activity, or how many hot food takeaways can operate near schools. While local authorities have a range of powers to support local solutions to address childhood obesity, many face challenges. We want to make sure that all local authorities are empowered and confident in finding what works for them to tackle childhood obesity.

We have now selected 5 successful Childhood Obesity Trailblazer authorities, who together will have access to £1.5 million of funding and support over the next 3 years. They are: Blackburn with Darwen, Birmingham, Bradford, Lewisham and Nottinghamshire. Across the 5 areas, Trailblazer activity will support and create opportunities for future generations, from supporting families and children in the early years through to upskilling adolescents and young adults. Between them, they will test the potential for existing local levers to:

- restrict out-of-home HFSS advertising

- create healthier food environments through the planning system

- use community and faith assets

- incentivise businesses to improve their retail offer

- improve accessibility and affordability of healthier foods

- improve job opportunities and growth in health, food and physical activity sectors

This will help to inform further action the government can take in the future to enable ambitious local action. We will also share the learning from the programme to encourage and empower wider local action across the country.

While we know this represents a world-leading approach, we have always been clear that we need to go further and faster in ensuring everyone has a chance to lead a healthier life.

That’s why we’re publishing Chapter 3 of the childhood obesity plan as part of this green paper.

This sets out our plans for: infant feeding, clear labelling, food reformulation improving the nutritional content of foods, and support for individuals to achieve and maintain a healthier weight.

Infant feeding

To support families, it’s important to understand the choices they make when it comes to infant feeding. In England, most mums start breastfeeding. However, after 6 to 8 weeks, only 4 in 10 are still breastfeeding their babies.[footnote 61] The UK has one of the lowest breastfeeding rates in the world.[footnote 62]

Given the benefits of breastfeeding, we intend to commission an infant feeding survey to provide information on breastfeeding and the use of foods and drinks other than breastmilk in infancy. This will also provide the means to assess the impact of the actions we are taking on infant feeding which are outlined below.

Currently 18% of boys and 21% of girls aged 2 to 4 years are overweight or obese.[footnote 63] Therefore, we need to look at what we can do in the early years to help give children the healthiest start in life.

We know that 3 in 4 children aged 4 to 18 months have energy intakes that exceed their daily requirements.[footnote 64] This figure increases with age following the introduction of solids. Data shows that sugar levels in some commercial baby foods and drinks can be very high.[footnote 65] Around 9 in 10 children aged 1.5 to 3 years old exceed recommended daily sugar intake levels.[footnote 66] Consuming too much sugar, and too many foods and drinks high in sugar can lead to weight gain, which in turn increases the risk of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, stroke and some cancers in adulthood.[footnote 67] Added sugar in foods can have a negative effect on babies and young children’s health by putting them on this trajectory.[footnote 68]

High levels of sugar intake also increase the risk of tooth decay.[footnote 69] Just under a quarter of 5-year-olds in England have tooth decay[footnote 70] and almost 9 out of 10 hospital tooth extractions among children aged 0 to 5 could have been avoided.[footnote 71]

Because of this, we will challenge businesses to improve the nutritional content of commercially available baby food and drinks. PHE will publish guidelines for industry in early 2020.

Industry’s progress will be monitored and reported to the government. If insufficient progress is made, the government will consider other levers. PHE will also explore including baby food within the popular Change4Life Food Scanner app to help parents and carers make healthier choices for their infants.

Parents and carers want to know more about the nutritional value of the food and drink they buy for their families. This is particularly important in the early years, when parents and carers buying products marketed for infants and young children are making decisions about when and what to feed their baby.

Too many commercially available foods and drinks marketed for infants and young children have labels that do not align with the latest government scientific advice. They can also make a product appear healthier than it really is, or do not contain enough information about how they should be consumed.[footnote 72] All of this can be confusing to parents and carers.

We will therefore explore how we can improve the marketing and labelling of infant food. This is so that parents and carers have honest and accurate information on the products they feed their babies at this critical stage of life. We will seek views on how we do this.

Clear labelling

It’s important that everyone, regardless of their age, has access to the information they need to make informed decisions. But we know that identifying what food and drinks are healthy is not always easy. To support consumers in making healthier food and drink choices through labelling, we believe that people need 2 things:

- to know what’s in the food they’re buying

- for this information to be presented clearly and concisely, helping them to make quick, informed decisions about what to buy

Since 2013, the UK has led the way in recommending a voluntary nutritional labelling scheme, sometimes called ‘traffic light’ labelling. This uses colours, words and numbers to help UK consumers understand the amount of fat, saturated fat, sugar, salt and calories in a product. This scheme was the result of over 15 years of research to provide a label that meets the needs of UK shoppers.

As a nation, we’re proud of the success of this scheme. Front-of-pack labels feature on a significant proportion of pre-packaged food and drinks, and 9 in 10 shoppers agree it helps them make informed decisions when shopping.[footnote 73] We want to do more to ensure that our label still meets the needs of UK shoppers and that wherever people shop and whatever they buy they are presented with consistent front-of-pack nutritional labelling that they find helpful and easy to understand.

Since we introduced the UK scheme, a number of other countries around the world have introduced their own versions of front-of-pack nutrition labels. Some labels are similar to the UK approach, but many differ. For example, some countries like Sweden, Denmark and Norway choose to focus on signposting the healthier aspects of foods such as high fibre, while Chile chooses to alert shoppers to products that are high in nutrients such as fat, calories, salt and sugar that eaten in excess can be harmful to health.

We have previously committed in both Chapter 1 and Chapter 2 of the Childhood Obesity Plan to explore what additional opportunities leaving the European Union presents for front-of-pack food labelling in England.

As part of exploring this we will consult by the end of 2019 on how we can build on the successes of our current front-of-pack nutritional labelling scheme once we have left the European Union.

Our consultation will consider the evidence underpinning these many different forms of front-of-pack labelling. It will focus on ensuring that the UK continues to be world-leading in providing UK shoppers with simple nutritional information that they need to make healthier decisions, while taking into account the UK’s ambitions for trade once we have left the European Union.

Improving the nutritional content of food and drink

Central to our approach to improving diets is working with food and drink companies to make their products healthier. We often call this reformulation. Over time, these small changes can add up to big improvements in the nation’s health.

The Soft Drinks Industry Levy (SDIL) has been hugely successful in removing the equivalent of over 45,000 tonnes of sugar from our shelves. So far, we have not included sugary milk drinks within this ‘tax’. However, these drinks can also contribute to our sugar and calorie intakes, particularly given some of the larger portion sizes available.

Therefore, if the evidence shows that industry has not made enough progress on reducing sugar, we may extend the SDIL to sugary milk drinks.

We also need to do more to consume less salt. This is vital for reducing the risk of heart disease and stroke.[footnote 74] The government recommends that we should consume no more than 6g per day, well below the current average in England (8g per day).[footnote 75] This is mostly through salt that is already in the food we buy, rather than the salt we might add ourselves.

Case study: Salt reduction

Voluntary salt reduction targets for particular types of food were set for industry in 2014, building on 3 earlier sets of voluntary targets (in 2006, 2008 and 2011). These aimed to gradually reduce the levels of salt in the foods that contribute most salt to our diet.

PHE’s 2018 report showed that 81% of products were meeting the targets for 2017. Businesses achieving reductions include McCain Foods (GB) Ltd who have reduced the amount of added salt in their products by 22% since 2001, while Mars Food have reported an average reduction in salt of 30% since 2007 across their Dolmio and Uncle Ben’s cooking sauces, as part of meeting the 2017 targets across their products.

Our ambition is to reduce the population’s salt intakes to 7g per day.

To achieve this, we will publish revised salt reduction targets in 2020 for industry to achieve by mid-2023 and we will report on industry’s progress in 2024. Influencing consumer behaviour through marketing and providing advice, including within the NHS, will also help. We will keep all options open if a voluntary approach does not demonstrate enough progress by 2024. We will commission a urinary sodium survey in 2023 to measure progress towards the ambition and understand how much salt individuals are consuming.

Developments in food technology also offer opportunities to improve the nutritional content of food and drink in order to improve people’s health. For example, it is already possible to enrich eggs or milk with omega 3. Government will continue to examine the growing evidence in this area.

Support for individuals to achieve and maintain a healthier weight

We want to make it as easy as possible for people of all ages who want to lose weight to access the support they need. Access to the right services can help people achieve a healthier weight and reduce the cost to the NHS and public services further down the line.

Evidence shows that patients are receptive to brief interventions for obesity.[footnote 77] On average, they lose weight in the year following the intervention. Being able to deliver a brief intervention and provide opportunistic advice in a primary care setting presents an effective way for doctors to engage with obese patients about weight management and lifestyle.

We will work with NHS England to develop approaches to improve the quality of brief advice given on health issues, including weight management, in general practice. We will also explore the use of quality improvement approaches, and test any new, innovative proposals through the new NHS Primary Care Network Testbeds, as appropriate.

As more services go online, we will drive the digital market for weight management apps; helping health professionals to offer patients support in new, innovative ways that fit with how they live their lives.

We will work with NHS England, PHE and NHSX to review the current digital weight management offer on the NHS Apps Library, and promote the app marketplace to encourage the availability of more products and services.

We will also continue to develop Our Family Health, a digital approach to support families with children aged 4 to 7 years with lifestyle behaviour change. We will work with local authorities to explore how Our Family Health can support families living in some of our most deprived areas with high childhood obesity rates.

Every year, the National Child Measurement Programme (NCMP) measures the height and weight of over 1 million children aged 4 to 5 and 10 to 11 in state schools across England.[footnote 78]

The programme provides key opportunities for parents to be informed of their child’s weight status and to access support from health professionals and local services, where appropriate. However, there is currently no standard route to share this vital information with healthcare professionals; for example, through the health and care record. As such, it’s not done routinely.

Case study: Children’s weight services in Essex

Livewell Child is a local initiative led by Braintree District Council that is all about supporting children and families to eat well, keep active and feel good. Following the start of the programme in 2016, there has been 1.2% decrease in the number of overweight pupils in year 6 between 2016 to 2017 and 2017 to 2018 across the schools taking part in the Livewell Child programme. This contrasts with an increase in the number of pupils who were overweight in schools in Braintree that did not take part in the programme. Key to this approach has been the development of a lasting and trusted relationship with the 10 pilot schools, which has been built over the last 2 years.

To better enable families identified through the NCMP to access support, PHE will work with NHS England and NHS Digital to explore how NCMP data can be shared directly with digital child health records and presented appropriately so that it’s consistently accessible for both parents, carers and health professionals.

We will also explore how to embed Our Family Health within the NCMP, so that more families are getting the help they need.

We will also look to the latest behavioural science to understand how we can best communicate with parents and health professionals on obesity.

Staying active

Becoming more active is good for our mental and physical health, and reduces our risk of developing a number of health conditions. For example, regular activity can reduce our risk of hip fractures by 68%, type 2 diabetes by 40%, heart disease by 35%, and depression by 30%.[footnote 79]

It can also help us keep the weight off after a (diet-led) weight-loss programme. It can also help the third of people who are already a healthy weight to stay that way.[footnote 80] This has led some experts to suggest:

If physical activity were a drug, we’d talk about it as a miracle cure.

Professor Dame Sally Davies, Chief Medical Officer for England and Chief Medical Adviser to the UK government (2017)[footnote 81]

Case study: Grassroots football

The Football Association’s report on The Social and Economic Value of Adult Grassroots Football in England found that participants report significantly higher levels of happiness and general health compared with people who play no sport. People in lower-income groups also experience greater health benefits from football than higher-income groups.

Despite this evidence, many of us are not active enough to ensure we’ll remain healthy and independent for as long as possible: a third of adults do not meet guidelines of 150 plus minutes of aerobic activity a week;[footnote 83] and evidence suggests that the UK is less active than France, the Netherlands and Australia, and has twice the level of inactivity seen in Finland.[footnote 84]

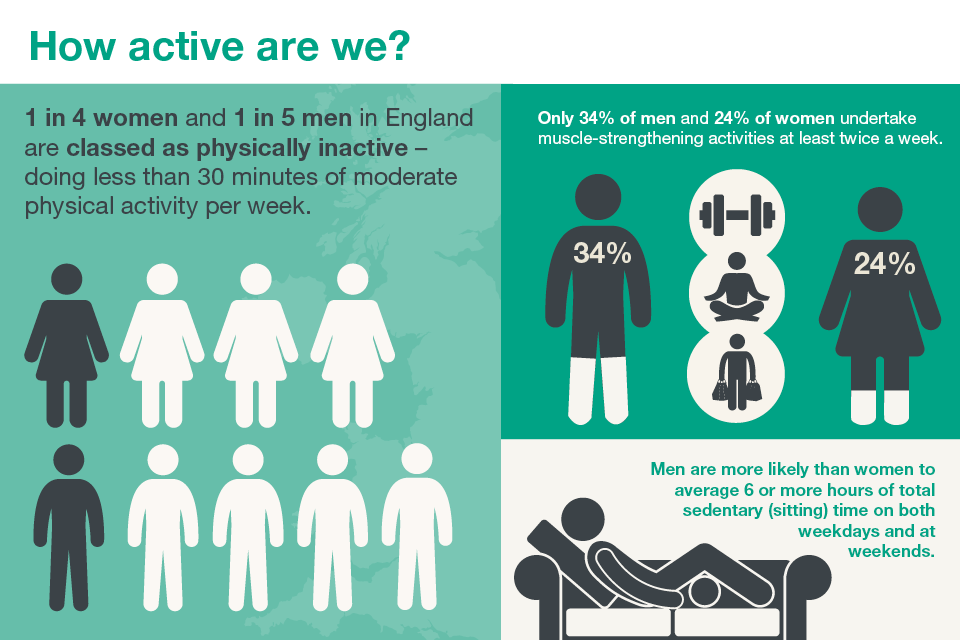

Figure 8: How active are we?[footnote 85]

1 in 4 women and 1 in 5 men are classed as physically inactive - doing less than 30 minutes of moderate physical activity per week. Only 34% of men and 24% of women undertake muscle-strengthening activities at least twice a week. Men are more likely than women to average 6 or more hours of total sedentary (sitting) time on both weekdays and at weekends.

1 in 4 women and 1 in 5 men in England are classed as physically inactive - doing less than 30 minutes of moderate physical activity per week. Only 34% of men and 24% of women undertake muscle-strengthening activities at least twice a week.

The UK Chief Medical Officers have published guidelines that clearly state the amount of activity required for good health. One of the easiest ways to get active is to build physical activity into your daily commute to work or school. Walking and cycling are 2 of the top ways that people in England keep physically active[footnote 86] and are the most accessible and cheapest forms of transport.

Given the importance of physical activity we’ve asked the UK Chief Medical Officers to review the current guidelines. New guidelines will be published in September 2019.

The guidance states that all adults should aim to be active every day. This should include muscle-strengthening activity – such as exercising with weights, yoga or carrying heavy shopping – on at least 2 days a week. These types of activity are particularly important for people in or approaching later life. This is also the case for balance exercises, which are recommended twice a week for older people at risk of falls. Yet rates of strength and balance activity are particularly low, with just 1 in 4 women (and 1 in 3 men) meeting the recommended guidelines.[footnote 87]

We will work with partners to launch a new ‘digital design challenge’ for strength and balance exercises.

This will ask ‘how can we use digital to support the public to do regular activities to increase their strength and balance?’. The challenge will be focused on:

- older people

- those living with health conditions already

- people on low income, in deprived areas

The final product or service should be free to use and available across England. The design challenge will be launched in the autumn.

Physical activity can also help those living with a health condition to keep symptoms under control, and to prevent additional conditions from developing.[footnote 88] Yet we know that getting more active can be daunting, especially if you haven’t done much exercise before or you’re managing a health condition. In the 2020s, we want to get everybody active, including those of us who are already living with a health condition.

To support this, we are launching a second phase of the national Moving Healthcare Professionals partnership programme led by PHE and Sport England, which supports healthcare professionals to promote physical activity to their patients.

We will work with the UK’s leading health charities and Sport England to support the launch of a new physical activity campaign, which seeks to empower and inspire those living with health conditions to be more active. The campaign will be launched later this year and is supported by PHE.

We will also be working across government to encourage:

- local authority planning decisions to promote active lifestyles

- more people to switch from driving to public transport, cycling and walking – especially on the school run

- nurseries to build opportunities into their daily routine for physical activity such as energetic play, walking and skipping (pdf, 232 KB)

- strengthening the evidence base about the social and economic value of physical activity

Taking care of our mental health

Good health is much more than the absence of illness. It’s a state of wellbeing that includes our mental as well as our physical health. Parity of esteem was enshrined in law back in 2012. This requires the NHS and local authorities to consider the ‘whole person’, and their mental and physical health needs as equally important.

This government has provided people with greater access to mental health services.[footnote 90] And, in doing so, we began to close the ‘treatment gap’ between mental and physical health:

-

We are spending more on mental health services. The NHS Long Term Plan commits at least a further £2.3 billion a year by 2023 to 2024.[footnote 91]

-

One million people now have access to psychological therapies for common mental health problems.[footnote 92] The Long Term Plan promises to treat an extra 380,000 per year.

-

An additional 24,000 women per year will benefit from increased access to perinatal mental health care by 2023 to 2024, in addition to the extra 30,000 women getting specialist help by 2020 to 2021.[footnote 93]

-

At least 345,000 more children and young people will have access to mental health support including via new mental health teams in schools.[footnote 94]

We now need to close the ‘prevention gap’ and achieve parity of esteem, not just for how conditions are treated, but also for how they are prevented. When it comes to preventing health problems, much of our focus is still on people’s physical health. Less attention is given to the steps we can take to improve our mental health and wider sense of wellbeing. This is despite our physical and mental health being closely related – physical health problems increase the risk of poor mental health, and vice versa.[footnote 95]

Tackling risk factors and strengthening protective factors

We need to lay the foundations for good mental health across all parts of our society. This is because the circumstances we’re born into – and the conditions in which we live – all have a major bearing on our mental health. We need to take urgent action to tackle the risk factors that can lead to poor mental health, such as adverse childhood events, violence, poverty, problem debt, housing insecurity, social isolation, bullying and discrimination. We also need to invest in the protective factors that can act as a strong foundation for good mental health throughout our lives, such as strong attachments in childhood, living in a safe and secure home, access to good quality green spaces, security of income, and a strong set of social connections.[footnote 96] These will be considered in the next chapter.

Mental health problems can have a broader impact on society. Poor mental health at work costs the UK economy between £74 billion and £99 billion per year.[footnote 97] Mental ill-health is also associated with lower life expectancy, with some conditions associated with reductions in life expectancy of 10 to 20 years.[footnote 98]

Case study: Prevention Concordat for Better Mental Health for All and Thrive Bristol

The Prevention Concordat for Better Mental Health for All brings together a wide range of organisations that have committed to preventing mental health problems and promoting good mental health. The organisations that join the Concordat agree to work together to take local and national action to achieve the aim of better mental health for all.

‘Thrive Bristol’ is an example of the action taken by a signatory of the Prevention Concordat, Bristol City Council. It is a 10-year programme to improve the mental health and wellbeing of everyone in Bristol, with a focus on addressing inequality.