Consumer vulnerability: challenges and potential solutions

Published 28 February 2019

A collage of photographs of people who have been interviewed as part of this work.

Foreword by the Chairman

Supporting vulnerable consumers is an essential part of the CMA’s job. We can all be vulnerable in certain contexts: if we need to make a purchase at a stressful time, for example, or feel under pressure to make a choice between different options that we do not fully understand. Some of us will experience vulnerability during particularly difficult periods of our lives, while for others vulnerability derives from longer term challenges, such as physical disability or protracted periods of poor mental health.

This paper explores the different dimensions of consumer vulnerability and considers what the CMA can do to help. It is the result of a programme of work that we have undertaken, comprising research and discussions with a range of organisations such as Age UK, Citizens Advice, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, Money and Mental Health Policy Institute and Scope. These discussions have been lively and impassioned and have contributed greatly to improving our understanding. We are grateful to all those who have taken part.

One of the most informative aspects of the CMA’s work has been the in-depth research we have conducted with people on low incomes across the country, to improve our understanding of the challenges they face. Hearing about their experiences, and the difficulties they face in getting a fair deal in a range of markets, provides a very salutary reminder that, in assessing how well markets are working, it’s the experience of millions of people using them that counts. And we need to take particular account of this experience in designing remedies, so that when we intervene in a market, we do so in a way that will can benefit everyone.

At the end of last year, the CMA published our response to the loyalty penalty super-complaint. The topics of consumer vulnerability and exploitation of loyal customers are closely linked, and speak to wider public concerns about the role of markets and the balance between competition and regulation. There has been a widespread erosion of trust in markets, and the CMA and other regulators can and should be playing an important role in arresting and reversing that loss of trust.

Andrew Tyrie, CMA Chairman

Introduction

Helping vulnerable consumers is central to the Competition and Market Authority’s (CMA) mission. It is one of the key strategic priorities set out in our Annual Plan[footnote 1] and is one of the principal areas of focus of the government’s consumer green paper and draft strategic steer to the CMA.[footnote 2] Much of our previous work – and that of our predecessor bodies, the Office of Fair Trading (OFT) and the Competition Commission (CC) – has also focussed on aspects of consumer vulnerability. Examples include the CC market investigation into payday lending and the CMA’s market study and consumer enforcement into care homes for the elderly.

We recognise, however, that we need to do more. In particular, we need to improve our understanding of the different dimensions of consumer vulnerability across markets and to ensure that we are in a better position to help those members of our society who are at greatest risk of suffering from poor market outcomes. To help achieve these aims, in 2018 we established a programme of work on vulnerable consumers. This has comprised of wide-ranging engagement with different groups, analysis and externally-commissioned research, providing a rich insight into the different forms that consumer vulnerability can take and what can be done to help.[footnote 3]

The insights we have gained in the course of our work have already proved to be valuable: notably they have informed our response to the ‘loyalty penalty’ super-complaint, published at the end of last year. We investigated concerns raised by Citizens Advice that longstanding customers pay more than new customers for the same services (known as a ‘loyalty penalty’) in key markets such as mobile, broadband, cash savings, home insurance and mortgages. We considered the experience of vulnerable consumers throughout our response and set out a package of cross-cutting reforms and market-specific recommendations to tackle the loyalty penalty, including consideration of additional protections for vulnerable consumers.

This paper sets out some of the lessons that we have learned from our vulnerable consumers programme of work. It is structured as follows:

-

the paper starts by considering what we mean by consumer vulnerability. It draws an important distinction between ‘market-specific vulnerability’, which can affect any of us in certain contexts, and ‘vulnerability associated with personal characteristics’, which captures the idea that individuals with certain characteristics may face particularly severe, persistent problems across a range of markets;

-

the main body of the paper then draws on our research and discussions to consider the challenges faced by different types of vulnerable consumer in engaging with markets, evidence on market outcomes, and what can be done to help overcome these challenges; and

-

finally, the paper presents the conclusions from our work to date and sets out next steps.

What is consumer vulnerability?

In this paper we use the term consumer vulnerability in a broad sense, to refer to any situation in which an individual may be unable to engage effectively in a market and as a result, is at a particularly high risk of getting a poor deal.[footnote 4]

Such vulnerability may arise for a variety of reasons. Many of us can be vulnerable in certain market contexts, such as when we have to choose between complex alternatives or make decisions on the basis of imperfect information. Some of us may experience vulnerability during difficult periods of our lives, such as when we go through a bereavement, a divorce or a period of ill health. Vulnerability can also derive from more enduring personal circumstances, such as a long term physical disability. Consumer vulnerability is not, therefore, a binary concept: it is multidimensional and often highly context-specific.[footnote 5]

In this paper we distinguish between two broad categories of consumer vulnerability:

- ‘market-specific vulnerability’, which derives from the specific context of particular markets, and can affect a broad range of consumers within those markets; and

- ‘vulnerability associated with personal characteristics’ such as physical disability, poor mental health or low incomes, which may result in individuals with those characteristics facing particularly severe, persistent problems across markets.

Most of the CMA’s project work has focussed on addressing market-specific vulnerability. There has been comparatively little focus on vulnerability associated with personal characteristics, or the challenges faced by certain groups of vulnerable consumers across different markets. We expand upon these two definitions below, giving some examples from recent CMA work.

Market-specific vulnerability

There are certain market contexts in which all of us can experience a degree of vulnerability - for example, when we need to make a purchase at a stressful time. Vulnerability can also arise if assessing the value of a product involves complex estimations of risk or probability (as is the case with many financial services products) or if we are required to make a choice when we do not fully understand the options available to us.

Much of the CMA’s work – whether market studies and investigations, consumer and competition law enforcement, or merger assessment – has addressed different forms of market-specific vulnerability. Our market study into care homes, for example, showed to what extent an emotionally stressful situation such as choosing care arrangements for a loved one, can inhibit our ability and willingness to exercise consumer choice. This is also a key issue we are looking at in our ongoing market study into funeral services, as explained in Box 1.

CMA funerals market study

The death of a loved one is one of the most difficult events that any of us will face in our lives and it falls upon those who are most affected by the loss to organise the funeral. People are often poorly prepared, grieving, emotional and under pressure to arrange a funeral quickly. In addition, we purchase a funeral relatively infrequently, and therefore have little knowledge of what is required or what options are open to us. In our research, a large group of respondents reported emotional distress as one of the factors for not shopping around. When probed about reasons for not considering different funeral directors, many explained that they had been struggling to handle their grief and deal with practical arrangements at the same time. Our research shows that people who organise a funeral do not use some of the most basic ways of seeking value for money (eg getting more than one quote) that consumers typically display in other circumstances.

More information on the CMA’s market study into funeral services is available on the case page. [footnote 6]

Behavioural economics seeks to categorise some of the ways in which consumer vulnerabilities can manifest themselves in specific market contexts. A leading practitioner in this field, Nobel Laureate Professor Richard Thaler, addressed us on this topic at our symposium on vulnerable consumers. He identified a number of ‘behavioural biases’ that constrain our ability to choose between alternative products, some of the most important of which include: ‘framing’ (the notion that we make different decisions depending on how the same choices are presented to us); and ‘inertia’ (the notion that we tend to stick with defaults and the status quo).

Businesses are able to exploit these vulnerabilities to charge consumers higher prices – a clear example of this occurring was in the energy market, where our investigation found that around 70% of consumers were on highly expensive default tariffs, resulting in consumer detriment of almost £2 billion in 2015. More recently, we investigated this practice of charging higher prices to longstanding customers - sometimes called the loyalty penalty - in response to a super-complaint, as explained in Box 2.

CMA response to loyalty penalty super-complaint

Our investigation found that in markets which are subscription-based, or have auto-renewal or roll over contracts, longstanding customers can end up paying more than other customers (a loyalty penalty). We identified two main reasons for this. First, some people are less likely or able to negotiate or switch provider to get a better deal. This might be out of choice, or due to factors such as inertia, being too overwhelmed by the information and choices available to switch or feeling that the switching/negotiation process is too time-consuming or difficult. Second, businesses are able to charge higher prices to such customers and choose to do so. It can be easier for businesses to exploit customers in markets with auto-renewal/roll over contracts or which are subscription-based, by increasing prices year on year. Loyalty penalty pricing is particularly concerning when: suppliers make it more difficult than it needs to be for customers to exercise choice, and then exploit those who do not switch; the price gap is large or it affects many people; it particularly harms those who may be vulnerable such as the elderly, those on low incomes, or with physical disabilities or poor mental health; or it arises in markets where the nature of the services provided can be considered ‘essential’ - such as utilities markets - or make up a large proportion of people’s expenditure.

We found that consumers were paying a total penalty of around £4 billion a year across the five markets we investigated - mobile, broadband, cash savings, home insurance and mortgages. Loyalty penalty pricing might also arise in other auto-renewal, roll over or subscription-based markets, such as other insurance markets, pay-TV, credit checking services, or software.

While digital markets can create opportunities for helping consumers overcome vulnerability, business practices in digital markets can also exacerbate existing vulnerabilities and create new forms of vulnerability. We jointly hosted a roundtable on vulnerability in digital markets with Citizens Advice to explore some of these issues.[footnote 7]

We have taken action where we have found evidence of business practices that seek to exploit consumer vulnerability in digital markets. Last year we took enforcement action against online gambling firms which were making it difficult for customers to access their winnings, which made it harder for customers to stop gambling. We secured undertakings from six firms to commit to stop these unfair practices. We also recently took action against a number of online travel agents, following concerns about practices including: pressure selling; misleading discount claims; the effect that commission has on how hotels are ordered on sites; and hidden charges. As a result, these businesses have voluntarily agreed to make changes to their practices to address these concerns.

Understanding different characteristics associated with vulnerability

To date, the CMA has placed less emphasis on understanding to what extent groups of consumers with certain characteristics face enduring problems across markets.[footnote 8] While to a large extent this reflects the focus of the tools at our disposal, which are generally designed to tackle issues that we identify within individual markets, this is an important gap in our evidence base. If individuals with mental health problems, or on low incomes, for example, face a consistent set of problems across markets, this has potentially important implications for the best way to intervene to help such consumers. Our programme of work on vulnerable consumers was created in part to fill this gap, and this is the main focus of the rest of this paper.

In our discussions with different organisations and our commissioned qualitative research[footnote 9], we have focussed on four characteristics associated with consumer vulnerability: mental health problems; physical disabilities; age; and low income. These were chosen on the basis that our own experience and previous research suggests that consumers with these characteristics may face additional, specific challenges in engaging across a range of markets.

For ease of reference, in this paper we use the general term ‘vulnerable consumers’ to refer to people with at least one of these characteristics.

That is not to say that all individuals with such characteristics are necessarily vulnerable. We recognise that many individuals within these groups do not see themselves (or want to be described) as ‘vulnerable’, and it is important to note that our objective in undertaking this work has not been to label or categorise individual experience in a reductive way. Neither is it the case that these are the only personal characteristics that are likely to be relevant for understanding consumer vulnerability: many other factors, such as ‘time poverty’; confidence in using the internet; and level of educational attainment are likely to affect consumers’ ability to engage in certain markets.

Publicly available statistics suggest that there are significant numbers of people with at least one of these four characteristics:

- around 25% of the population in England experience a mental health problem each year[footnote 10], and one in six report experiencing a common mental health problem (such as anxiety or depression) in any given week;

- 22% of the UK population (around 14 million people) report having some form of disability[footnote 11];

- 18% of the UK population (around 12 million people) are aged 65 or over;[footnote 12] and

- 22% of the UK population (around 14 million people) live in low income households (ie with income below 60% of the median income).[footnote 13]

What these official statistics do not tell us, however, is the extent to which these characteristics overlap in the population and how many individuals have one or more of these characteristics. To explore this question, we analysed data in our survey of 7,000 domestic energy customers in Great Britain, conducted as part of our energy market investigation.[footnote 14] We found that nearly half of our survey population (49% of respondents) were either on a low income or disabled or above 65, and almost a third (31%) were either on a low income or disabled. A relatively small proportion of our survey population (3% of respondents) had all three characteristics (being on a low income, above 65 and disabled).

The challenges faced by vulnerable consumers in engaging with markets

In developing our views on the challenges faced by vulnerable consumers, we have drawn on a number of roundtables that we have held jointly with a range of organisations representing different groups of people.

With the Joseph Rowntree Foundation we organised a session on the challenges facing people on low incomes, and with the Money and Mental Health Policy Institute (MMHPI), we discussed the issues faced by people suffering from mental health problems. These were followed by sessions with Age UK on elderly consumers and with Scope on consumers with physical disabilities. We also visited the devolved nations to understand specific issues facing vulnerable consumers in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Finally, we held a symposium that brought together insights from a wide spectrum of contributors on the challenges facing vulnerable consumers and the potential solutions to these challenges. All of these sessions have been well attended, they have invariably led to lively debate and we have found them invaluable in developing our thinking.[footnote 15]

We have supplemented these insights with analysis carried out as part of previous CMA projects that have addressed aspects of consumer vulnerability and with qualitative research that we commissioned from BritainThinks into the challenges facing consumers who are on low incomes, have poor mental health, a physical disability and/or are elderly.[footnote 16] The aim of the research was to provide an understanding of the challenges which vulnerable consumers face across a range of markets and to identify what support may help to address them. This research has provided us with rich and detailed insights into the experiences of vulnerable consumers in engaging with markets, and we refer to our findings throughout this paper.

Consumers suffering from poor mental health

Consumers with poor mental health can struggle to engage with markets for a number of reasons. Around a third of participants in our commissioned research had mental health problems in addition to being on a low income. We draw on their experiences here, as well as our roundtable discussion with MMHPI and other research.

In order to understand the challenges that consumers with mental health problems face when engaging with markets, it is important to consider the nature of their condition and how it may affect their ability to participate. There is a wide range of mental health conditions, from depression to affective psychosis to schizophrenia and many in-between. Some participants in our qualitative research self-identified as having mental health problems including anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and personality disorder.

A key overarching point that was raised in the roundtable discussion regards the often transient nature of mental health. People can go through periods of good and poor mental health, for varying lengths of time. When they are experiencing good mental health, they may be able to cope with certain tasks and activities that become extremely difficult for the same individual when experiencing poor mental health. Research commissioned by Citizens Advice identifies this behaviour as ‘fluctuating management’, because it has implications for consumers’ ability to manage their accounts for key services such as energy or telecoms. This means that during bouts of poor mental health, individuals can struggle to pay bills on time, or go through periods of disengagement from their supplier.

This theme also came out of our research. Several participants spoke about the fluctuating nature of their mental health problem and ‘having bad days’ where they felt unable to engage in even basic day to day activities.

Generally speaking, if I was feeling down, I wouldn’t go out, but on Sunday, I felt the need to go out … It’s, sort of, different all the time.

Qualitative research participant, mental health problems, aged 65-74, Belfast.

In our roundtable discussion and qualitative research we identified a number of reasons why people with mental health problems may be more likely to have difficulty engaging with markets. An important insight is that the specific mental health problem an individual has, can be fundamental to understanding the difficulty they face in engaging with markets. This is reflected in the examples set out below.

Many people suffering from poor mental health have difficulties with certain types of communication. MMHPI found that 75% of customers who have experienced mental health problems have serious difficulties engaging via at least one commonly used communication channel such as telephone, face to face contact, or letters. This can mean that they are unable to engage with suppliers through the channels available to them, for example to ask a question about their billing or account services. The nature of the difficulty can vary by mental health condition - people with anxiety may avoid interactions or communication with others as a coping mechanism, to prevent themselves getting overwhelmed, which may be easier to do with letters or emails, whereas people who suffer from paranoia or delusion may struggle to communicate by phone because, for example, they may think their phone line has been bugged.

Participants in our qualitative research with mental health problems often described having low levels of confidence in engaging with others, which was reflected in the difficulties they faced when communicating with suppliers.

If I get letters they just go in the bin, I don’t [do] anything. I don’t like to pick up the phone. I just want to shut everything out and be alone in my room.

Qualitative research participant, mental health problems, aged 35-44, Glasgow.

A lack of ‘mental bandwidth’ required to be able to think about engaging with suppliers was another problem typically encountered. Individuals experiencing depression can struggle to get the motivation to carry out the various tasks required to switch suppliers - one MMHPI survey found that 82% of respondents said they found the thought of switching and shopping around exhausting. And a survey commissioned by Citizens Advice found that 15% of those who have experienced a mental health problem in the last 12 months think it is too difficult to switch contracts in key markets such as telecoms and financial services, compared to 5% of those who have not. The nature of the difficulty can increase dramatically for people currently experiencing poor mental health - MMHPI data shows that 81% of people who are currently unwell find it difficult or very difficult to sign up with an essential service provider or to open an account, compared with 18% of those who have experienced mental health problems previously, and 4% who have not.

Our qualitative research found that participants with mental health problems were likely to fall into the segment of participants who stayed with their provider and did not switch, shop around or negotiate. This group were often aware that they could be overpaying for services and aware that switching and negotiating are possible but were not taking action because they felt that it would be too overwhelming and difficult. Understanding which individuals exhibit these sorts of characteristics can be relevant to remedy design, as we discuss later.

Other research has found that consumers with mental health problems such as stress, anxiety and depression, may avoid switching suppliers or services because they require stability and routine to help maintain their mental wellbeing. For such individuals, change can be highly disruptive. This can affect their ability to manage their supplier or service accounts if there are changes in for example, what these look like or how they operate, or to deal with any unanticipated problems in their service provision.

Compulsive behaviour and addiction can make it difficult for consumers to engage safely and effectively in a market. The CMA’s consumer enforcement investigation into online gambling showed in stark terms how firms can sometimes attempt to exploit such behaviour. The investigation found that in promotions, consumers are often prevented from accessing winnings from their deposit funds until they meet wagering requirements. The requirement for consumers to commit to an extended period of gambling before winnings can be withdrawn, and preventing them from stopping gambling whenever they choose, was considered a particular risk to consumers vulnerable to problem gambling.[footnote 17]

Mental health conditions such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or bipolar disorder, can affect individuals’ cognitive ability and result in impulsive behaviour such as volatile overspending on something that is not needed, or is unaffordable. This in turn can cause problems down the line, such as a reliance on (high-cost) credit, and indebtedness. [footnote 18] In a survey of 5,413 people with mental health problems carried out by MMHPI, nearly all respondents (93%) said that when they are unwell they spend more, and 59% had taken out a loan they would not have taken out otherwise.

While many participants in our qualitative research reported finding the credit market problematic, this was particularly the case for participants with mental health problems. These participants often felt less confident managing their money and less in control of their spending, and felt anxious about the risk of overspending as a result of certain impulses or in periods in which they felt ‘on a high’.

I don’t really manage my money, I’m really bad … I do try and budget but it never works.

Qualitative research participant, mental health problems, aged 35-44, Glasgow.

There is evidence to suggest that some mental health conditions can result in impaired cognitive skills, which in turn can affect people’s ability to carry out certain tasks such as managing finances. For example, an individual with memory impairment from conditions like ADHD, bipolar disorder or obsessive compulsive disorder, may struggle to track their spending and to budget their finances. Someone with depression or borderline personality disorder can experience attention problems, preventing them from being able to concentrate for the time needed to pay or check a bill. This can make it difficult to understand complex billing information, or to compare and choose suppliers, particularly in markets with complex services/products, or with lots of suppliers.

When you’re anxious and when I’ve been so ill, I could be thinking all day what I’ve got to do but I just won’t do it. Like, I worry about it, I overthink it so much that I don’t do it.

Qualitative research participant, mental health problems, aged 45-54, London.

People with mental health problems may therefore need additional help or support to engage with markets. However, our discussions and qualitative research identified a key challenge in providing such support, which is that those who do engage with suppliers often do not disclose their condition. This can be due to a fear of stigmatisation that they will be treated differently or offered poor value deals, uncertainty about how the information might be used, or because they do not think it will make a difference to their experience. In addition, a few participants in our research felt that there was no suitable time or point in their engagement with suppliers to disclose their mental health problem. If suppliers are not aware that a customer has mental health problems, they cannot provide the additional support customers may need.

Our research found that in a few cases, participants had disclosed their vulnerability to suppliers and received no offer for additional help or consideration.

The amount of times I rang people when I was really, really down, bad, and asked someone to come and help me, and they told me, ‘Oh,’ […] ‘You’ve got to come to us in [location].’ ‘I’ve got anxiety, I can’t get out the door. Can you not hear me, what I’m trying to say to you?’ We used to get the same thing, all the time. I’m getting better, thank God, but there are people who have been suffering for years. My heart goes out to them because I think, ‘How do they get by?’

Qualitative research participant, mental health problems, aged 45-54, London.

These types of challenges can mean that consumers with poor mental health are at an increased risk of experiencing poor outcomes in markets. They are less likely to get a good deal from a supplier, for example through switching or shopping around, because of the challenges they experience in these forms of engagement. This can mean they may be paying more than they need to for services.[footnote 19]

Consumers with mental health problems can also feel the consequences of experiencing poor outcomes in markets more acutely. For example, they are more likely to experience financial harm. One in four people experiencing a mental health problem is also in problem debt, and people with mental health problems are three times more likely to be in financial difficulty and more than twice as likely to be behind with some or all of their bills.

Elderly consumers

The UK population is ageing, with the number of people over 85 predicted to double to 3.2 million by 2041. According to research by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), 69% of UK adults aged 75 and over display one or more characteristics of potential vulnerability – rising to 77% for people aged 85 and over.

The CMA, its predecessor bodies and regulators have been active across a range of markets to tackle challenges and deliver better outcomes for older customers. Key markets for older people include regulated services (such as energy, financial services, telecoms and water) and a range of services relevant to later life (such as care homes, assistive products, funerals and retirement income products).

Our roundtable on vulnerability in later life with Age UK and our qualitative research provided insight on the range of challenges facing older consumers when engaging with markets. It highlighted the need for caution in using age as an indicator of vulnerability, since being older does not necessarily make you vulnerable. Older people face the same challenges as consumers of all ages, although there are conditions associated with ageing that may lead to some older people becoming more vulnerable.

Older people can become vulnerable due to the interaction of personal characteristics, situational circumstances and environmental factors (which include business and market interactions). Some older people will face challenges when navigating markets due to personal characteristics arising from multiple health conditions, sensory impairment, disability and cognitive impairment. Digital exclusion and limited digital capabilities are also factors in vulnerability and can constrain the ability of older people to engage in modern markets. Further challenges are posed by older people experiencing specific circumstances and life events, such as periods of isolation, loneliness and/or bereavement.

Recent research into cognitive ageing has highlighted the complex nature of the ageing process and how this can affect the ability of older people to make decisions. Normal cognitive ageing entails older people often having greater knowledge but being slower at processing information. However, a subset of individuals will experience greater degrees of age-related decline and severe forms of cognitive impairment such as dementia. In 2015, an estimated 850,000 people were living with dementia in the UK, with the vast majority being older people. People with dementia are likely to be particularly vulnerable and at risk when navigating markets. The condition will affect a large and growing part of the population in future, with the number of people with dementia forecast to increase to over one million by 2025.

The FCA has explored the implications of cognitive ageing as part of a wider programme of work considering how the UK’s ageing population will affect financial services. This included commissioning two external pieces of research on ‘the ageing mind’ and ‘coping mechanisms and third party access’. The FCA’s research revealed that older consumers are more likely to face challenges when needing to make more complex and unfamiliar decisions, such as changing insurance provider or deciding how to invest pension savings. Older consumers were found to often resort to workarounds or ‘coping mechanisms’ in accessing and dealing with retail banking products, as well as drawing on existing support networks where possible.

While technology has the potential to alleviate some challenges, digital developments can also create new barriers for older people. First there is the problem of digital exclusion: a higher proportion of older people either do not have access to the internet or do not feel confident using it. The Office of Communications (Ofcom) found that just under half (47%) of people aged 75+ do not use the internet. People who are digitally excluded often find it more difficult to engage: in our energy market investigation, we found that just over 50% of the people who had been on the expensive default tariff for more than three years either did not have access to the internet or did not feel confident using price comparison websites.

For those who do have access to the internet, our roundtable highlighted that some older people may have limited capabilities when online and are less likely to keep software up to date, with implications including missing out on services, security risks and possible product obsolescence. There are likely to be particular risks associated with groups experiencing more severely impaired judgement going online. In particular, security protections for online and telephone services may make it difficult to engage and there is also potential for older people to be more vulnerable to mistakes. Digital innovations may also be used in more negative ways to target older consumers, whose lack of confidence online may mean they are more susceptible to fraud and scams. For example, those aged 65 and over are least likely to check if an internet site is secure before giving their bank or credit card details as well as being less likely to use the internet overall.

Some older participants in our qualitative research perceived that older people were more likely to be taken advantage of, while for others, the threat of being scammed itself acted as a deterrent to going online.

People take advantage of old age people … I think probably they think they are too vulnerable, maybe, to understand, or they cannot do much. That is the reason.

Qualitative research participant, physical disability, aged 75+, London.

I wouldn’t do it online anyway, they nick your bank details on online, I wouldn’t do it. I just wouldn’t do it because there’s always a scam, new way to scam … that will never change in the world, that will never ever change.

Qualitative research participant, long term health condition, aged 65-74, Glasgow.

Age-related vulnerability is often linked to particularly stressful life events. In this respect, the CMA’s care homes market study highlighted that people are particularly vulnerable when choosing a care home – both those in need of care and those making emotive decisions on care on behalf of others. We found that once in a care home, it is often difficult for older people to move, complain and obtain redress – with people being vulnerable to unfair consumer law practices. We recommended that industry provide better information - for example on costs, that government and local authorities improve support for people seeking care, and that regulators play a greater role in protecting older people from unfair contracts.[footnote 20]

A fear of change and unfamiliar decisions can increase the propensity to ‘stick with what you know’ which can in turn result in greater risks for older people of being left behind and/or receiving poor outcomes. For instance, Ofcom’s review of the market for standalone phone services highlighted that older consumers were more likely to be on poor value landline-only contracts – paying very high prices for a basic service. Line rental prices were found to have risen significantly between 2009 and 2017, despite wholesale costs falling. Ofcom found that two-thirds of landline-only customers were over 65 years old (and over 40% above 75). Ofcom’s plans to improve outcomes for these consumers through the introduction of a price cap resulted in the voluntary reduction of charges for landline-only customers.

In some markets it may have never occurred to older people to switch supplier for a better price or deal, particularly if they are comfortable in using a former monopoly supplier or do not think there is an issue or need to switch. Some older participants in our qualitative research noted that they had no desire to change supplier.

I’m with electricity company X and gas company Y and I’m quite happy with that. I’ve never changed them and never will … I’m just set in my ways, and I think a lot of old people are like that, they don’t like change … As I say, and I’ll always say, I’m set in my ways, and change, I just don’t want it …

Qualitative research participant, long term health condition, aged 65-74, Glasgow.

Consumers with physical disabilities

There are challenges in defining and measuring disability, given the overlapping nature of some disabilities and the potential for certain conditions to fluctuate over time and affect people differently at different times. Twenty-two per cent (around 14 million) of people in the UK report having some form of disability – defined as a longstanding illness, disability or impairment which causes substantial difficulty with day to day activities. The prevalence of disability rises with age. Around 8% of children are disabled, compared to 19% of working age adults and 45% of adults over State Pension age. Research carried out by Scope suggests that, while some disabled people would describe themselves as ‘vulnerable’, over half do not.

Commonly-reported impairments are those that affect mobility. The CMA’s predecessor, the OFT, considered the mobility aids market (including wheelchairs, scooters, stair lifts, bath aids, hoists, adjustable beds and specialist seating) in 2011. It highlighted that users of mobility aids may be more likely to be vulnerable when making purchasing decisions, due to their limited mobility and age-related conditions. In addition, the OFT found that complaints about unfair sales practices in the sector were high – particularly for doorstep sales. The OFT subsequently also used its competition powers to investigate concerns in the sector – taking action against two mobility scooter manufacturers for entering into arrangements with retailers that breached competition law.[footnote 21]

Our roundtable considered the challenges experienced by disabled people across many aspects of their lives. Scope told us about the challenges faced by physically disabled people when accessing essential goods and services, which include extra costs due to their impairment or condition. Scope highlighted its research on the ‘disability price tag’, which estimates that disabled consumers face average additional costs (after deducting support and other benefits) of around £583 per month (on specialist equipment, more complex insurance policies, higher energy bills etc). One in five disabled adults face monthly costs in excess of £1,000. After housing costs, Scope estimated that disabled people on average spend almost half of their remaining income on disability-related costs. This is an example of how one aspect of vulnerability (eg physical disability) can lead to others, such as stress and money worries.

The ‘access, assess, act’ framework,[footnote 22] which considers the steps that consumers go through in order to exercise effective choice, can be applied to some of the challenges facing different physically disabled groups. Depending on the source of physical disability, people may find it harder to access the best deals, or to find out about them. If a physical disability affects cognitive capability (for instance, through being tired or in pain) then people might find it harder to assess alternatives. Physical constraints may also make it harder to act on decisions. Scope’s research also highlights a ‘digital divide’ for disabled people – with 20% of disabled adults having not accessed online content (in contrast to just 5% of adults without disabilities). Not having access to the internet will further reduce the ability of these people to access assess and act to secure good deals.

We also heard about the experience of a parent caring for their child with multiple disabilities. In particular, we heard about how extra costs can be experienced across a range of every day goods and services – from costs associated with regular hospital appointments, financial challenges incurred from the regular purchase of bespoke wheelchair equipment to difficulties of accessing common gateway products, such as insurance for holiday travel. Day to day priority caring activities also take time and energy, as well as placing a strain on finances. Such pressures often result in the carer having less time and ‘headspace’ to engage and deal with specific markets.

The challenges of caring for children with multiple disabilities were illustrated by one participant in our qualitative research who was disabled. The combination of life being ‘a struggle’ and regularly feeling tired, ill or in pain had implications for their ability to deal with payments which resulted in multiple demands when bills were not paid:

… when I had to physically pay all the payments myself, I used to miss them… just forgetting … or, I’m too ill, the day I’m supposed to have rung up and made the payment, and then, of course, you forget that you haven’t made the payment, and then the money’s in the account, and you think, ‘Oh God, I’m better off this month, I can get this.’ Then you get the letter through the door going, ‘You’ve not paid the water,’ and the rent’s not been paid.

Qualitative research participant with physical disability, aged 45-54, Watford.

Consumers on a low income

The question of whether consumer on low incomes secure poor market outcomes has attracted a high level of political and public attention. However, of the four dimensions of consumer vulnerability that we have considered in our research, this relationship is perhaps the most complex to understand. Part of the challenge lies in the fact that it is not always clear whether low income consumers are likely to secure better or worse outcomes than higher income consumers in specific markets.

On the one hand, consumers on low incomes stand to gain proportionally more from engagement in a market, relative to their income, than other consumers. If an individual is living hand-to-mouth, the ability to save a few hundred pounds a year from switching supplier can make a huge difference to their lives – much more so than for someone who is comfortably off. Consumers on low incomes therefore have a greater incentive to engage, which might encourage them to seek better market outcomes than people on higher incomes.

Our BritainThinks research provides some support for this view - some low income consumers appeared to be very aware of their finances and ‘savvy’ in their approach to managing bills. For example, participants were able to recite the exact amounts of their bills and when these were due to be paid. In contrast, the control group of higher earners were far less likely to be able to recount financial outgoings in as much detail.

However, as discussed at the roundtable on low income consumers that we co-hosted with the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, and explored further in our qualitative research, there are a range of factors that push in the other direction, suggesting that low income consumers can face additional barriers to engagement and hence may secure worse outcomes in some markets. Key among the factors that may inhibit engagement among consumers on low incomes are: constrained finances and higher risk of indebtedness; limited access to enabling products; and correlation with other dimensions of vulnerability.

Being on a low income often leads to constrained finances, which are likely to make consumers less willing to take risks because they have fewer or no savings to meet an unexpected cost. This focus on getting by from day to day may in turn lead such individuals to prioritise cash flow control and flexibility of expenditure over the total longer term costs of a product or service. This is illustrated by a preference among a number of participants in our research to use pay-as-you-go services rather than long fixed term contracts.[footnote 23] Even among those participants who preferred the certainty and fixed costs of a contract, there was a preference for these contracts to be more flexible in nature, and shorter term (eg 12 months versus 18 months).

Constrained finances may also lead some low income consumers to seek to defer expenditure even if this implies paying more over the long term (eg by purchasing a good through a hire purchase scheme).[footnote 24]

It’s a struggle, because all you need is something to go wrong in the house, or something to go wrong with the car, and then you’re not ticking over any more.

Qualitative research participant, physical disability, aged 45-54, Watford.

You have to take each day as it comes. Life is stressful, it’s all about keeping up with the mortgage payments … You get by. You focus on your bills. There’s no pots of money left at the end.

Qualitative research participant, mental health problems, aged 45-54, Watford.

For some of the consumers on low incomes in our research, the aversion to risks arising from constrained finances sometimes meant that they were unwilling to switch for fear that something would go wrong or that contractual arrangements would result in them being penalised.

Say you moved from [supplier X, supplier Y], whatever, to another supplier, you’ve no idea if you’ve got, like, say 12 months contract rolling 18 months, two years, 20 years, I don’t know. You don’t know if there’ll be any, sort of, fines for moving to another supplier. Not a clue.

Qualitative research participant, physical disability, aged 75+, Rhyl.

I think the way that companies do their thing now is like, there’s something about part of your contract is 12 months and the other part is 18 months, which technically means you can’t actually switch for 18 months, but if you don’t renew whatever it is, I can’t remember, at 12 months, then you’re without that for six months while you wait on the other part of the contract to run out.

Qualitative research participant, mental health problems, aged 65-74, Belfast.

Low income consumers are also at a higher risk of indebtedness, which can reduce the options available to them to get better deals. This is illustrated very starkly in the case of prepayment meters, onto which energy consumers are moved if they have an outstanding debt. In our energy market investigation, we found that prepayment customers (roughly half of whom had an income of below £18,000) got a far worse deal than other customers, since they did not have access to cheap tariffs, and suffered a disproportionately high level of detriment. A number of participants in our qualitative research described similar experiences.

… because I’ve got this debt now. […] If I couldn’t pay it all off, then you’ve got to have meters to put in your house and pay it that way. That was the only way I could do it.

Qualitative research participant, mental health problems, aged 45-54, London.

High levels of debt can also reduce creditworthiness, reducing the options for, and increasing the cost of, debt – as shown in the CC market investigation into payday lending. The challenges posed by a lack of options were also highlighted by participants in our qualitative research.

You use your demons like X doorstep lender, and you know, all your doorstop knockers who give you money. I’ve been in that situation … They love it. I mean we’ve got three or four trading people around here that do that sort of thing … they used to walk the estate, every week, knocking the doors. ‘Oh, we can give you up to £500 right here and now, and you pay us back £4.50 per week’ you know. Yes, but you pay it back forever … I’ve been through it. I’ve got the County Court Judgements for non-payments, I’ve had the debt collectors on the doorstep.

Qualitative research participant, physical disability, aged 45-54, Watford.

I needed money in the meantime and the only credit out there, because you’re unemployed, is high cost credit.

Qualitative research participant, physical disability, aged 45-54, Belfast.

Consumers on low incomes are also less likely to have access to important enabling products, such as the internet, a car or a bank account, which can be essential for obtaining the best deals in many markets. For example, according to FCA research, 62% of individuals who do not have a bank account have a household income of less than £15,000. In 2018, Ofcom reported that the proportion of adults in DE households (semi-skilled and unskilled occupations and the unemployed) who do not go online is almost double the UK average (22% vs 12%). Our qualitative research highlighted how this challenge area could be reinforced or made worse by the presence of other vulnerabilities, such as having a physical disability.

I can’t walk a distance … My daughter’s got the car, so my shopping and all of that-, I go with her a lot. She takes me quite a lot … Without her I’ve been taking a taxi from here to two streets along just because I can’t manage if there’s nobody here with a car.

Qualitative research participant, long term health condition, aged 65-74, Glasgow.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, having a low income is correlated with many other dimensions of vulnerability which themselves can negatively affect an individual’s ability and inclination to engage in a market. These include the other factors discussed in this paper - poor mental health, physical disability and old age – and many others, including low levels of education, digital exclusion or being time poor, among others. We analysed data from our survey of 7,000 energy customers undertaken for our energy market investigation to assess the extent of this relationship, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Dimensions of consumer vulnerability among energy consumers with incomes below and above £18,000 a year

| Incomes below £18,000 per year | Incomes above £18,000 per year | |

|---|---|---|

| Aged above 65 | 36% | 16% |

| Have a physical disability | 30% | 6% |

| Have no qualifications | 26% | 4% |

| Are time poor (being a carer or a single parent) | 26% | 15% |

| Either have no access to internet or are not confident in using a price comparison website | 56% | 31% |

Source: Survey of 7,000 energy customers undertaken in 2014 for the energy market investigation.

The results are striking: low income individuals are substantially more likely than people on higher incomes to exhibit each of the above dimensions of vulnerability. In particular, they are five times more likely to have a disability and more than six times more likely to have no qualifications. This suggests that these other dimensions of vulnerability are likely to be highly significant factors in shaping the experience of low income consumers in engaging with markets, and that low income consumers who do not have these characteristics may not be vulnerable to the same extent.

The varied nature and impact of vulnerability on consumers’ lives emerged as a theme from our qualitative research. While all participants (excluding the control group) were on a low income, most also had additional vulnerabilities - including mental health problems, physical disabilities and/or long term health conditions, being elderly, or having no formal educational qualifications. The research found that participants’ experiences of their day to day lives, including their engagement with markets, varied by the nature of their vulnerabilities.

For example, for participants with physical disabilities, reliability and consistency of service was often important where they were dependent on the service as a result of their disability. Low income consumers with physical conditions were therefore particularly unwilling to tolerate any uncertainty or disruption in certain markets, such as energy. As a result, they were unlikely to want to switch suppliers, even if this could get them a better deal.

For participants on low incomes with mental health problems, barriers to engagement with suppliers were often related to difficulties with communication. Having mental health problems also led participants to feel overwhelmed at the thought of managing their finances or engaging with a supplier, which often meant they avoided doing so.

Further, where being on a low income is correlated with other dimensions of vulnerability, specifying the precise nature of the causal relationship between them can sometimes be challenging – as MMHPI has highlighted regarding the relationship between low income and poor mental health. We also found evidence of this in our qualitative research.

Researcher: What about your mental health though? Is it more the low income or is it your mental health on top of that I suppose?

Participant: I think it’s all together, because my money stresses me out and makes my mental health go crazy, and then I can make myself go crazy.

Qualitative research participant, mental health problem, aged 35-44, Watford.

The patterns of vulnerability affecting low income consumers are, therefore, complex, and sometimes pull in different directions. Degrees of vulnerability differ quite markedly both between low income consumers and across different markets. This is borne out in our research, which found that consumers on low incomes generally felt more confident engaging with the grocery market compared to the other markets explored (telecoms, energy, credit, insurance).

Evidence on outcomes for vulnerable consumers

As set out in the previous section, there is a range of evidence to suggest that certain groups of consumers can experience significant challenges when engaging with markets and, as a result, are likely to be at a higher risk of getting a poor deal. In this section, we review the available evidence on the outcomes that vulnerable consumers achieve in markets. We first review data on switching and engagement among vulnerable consumers and then consider the available evidence on the prices that vulnerable consumers pay in different markets, focussing in particular on the ‘poverty premium’ – the hypothesis that low income consumers pay more than higher income consumers for the same goods and services.

Engagement and switching among vulnerable consumers

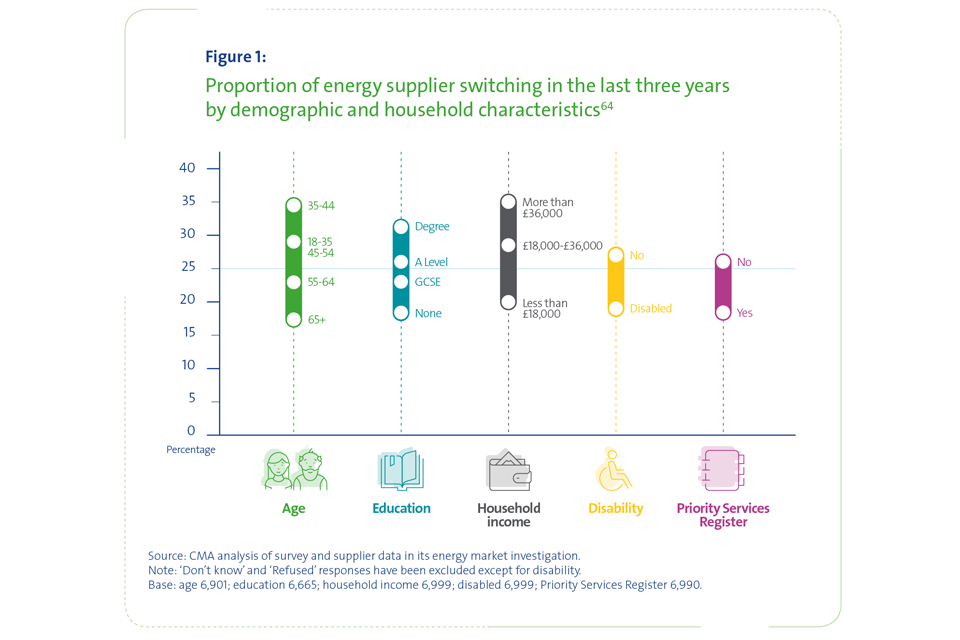

In our energy market investigation, we found strong evidence that vulnerable consumers were less likely to have switched energy provider than other consumers. Specifically, we found that the proportion of respondents to our survey who were less likely to have switched supplier in the last three years were consumers with any of the following characteristics: household incomes under £18,000 a year; living in rented social housing; without qualifications; aged 65+; with a disability;[footnote 25] or registered on the Priority Services Register (see Figure 1).[footnote 26]

Figure 1: Proportion of supplier switching in the last three years by demographic and household characteristics.[footnote 27]

Figure 1 graph

More recent data from Ofgem’s 2018 Consumer Engagement Survey presents a similar picture. Survey respondents aged 65+, on incomes under £16,000 or with a disability, were significantly more likely to have been with the same provider for 10 or more years (14%, 10%, and 12% respectively, compared with 7% of the sample).

We also considered engagement and switching among vulnerable consumers as part of our response to the Citizens Advice super-complaint. Drawing on the existing evidence base, we looked at whether particular groups of consumers were more likely to pay a loyalty penalty in the five markets we investigated (mobile, broadband, cash savings, home insurance and mortgages).

In the three financial services markets, we found evidence that different groups of vulnerable consumers - those on low incomes, aged 65+, without educational qualifications, who were unemployed, or had a physical or mental health condition - were more likely to be longstanding customers and less likely to have switched providers in these markets (see Table 2 for more details). As a result, they may be more likely to pay a loyalty penalty.

| Market | Proportion of consumers with the same provider for 10 years or more |

|---|---|

| Home insurance (contents and building) | Of those with home insurance; 46% have no educational qualifications; |

| - 43% are aged 65+; | |

| - 37% have a physical or mental health condition expected to last 12 months or more; | |

| - 32% are unemployed; and | |

| - 27% are earning less than £15,000; have had the same home insurance provider for 10 years or more, compared with 16% of all adults that have held their home insurance with the same provider for 10 years or more. | |

| Mortgages | Of those with a residential mortgage: |

| - 72% are aged 65+; | |

| - 64% are earning less than £15,000; | |

| - 48% have no educational qualifications; | |

| - 48% have a physical or mental health condition expected to last 12 months or more; and | |

| - 41% are unemployed; have held their mortgage with the same provider for 10 years or more, compared with 31% of all adults that have held their residential mortgage with the same provider for 10 years or more. | |

| Cash savings | Of those with a cash savings account: |

| - 56% have no educational qualifications; | |

| - 43% are aged 65+; | |

| - 34% are earning less than £15,000; and | |

| - 34% have a physical or mental health condition expected to last 12 months or more; have had a savings account with the same provider for 10 years or more, compared with 27% of all adults that have held their a savings account with the same provider for 10 years or more. |

Evidence from other sources broadly supports these findings. For example, the 2018 Money and Advice Service Financial Capability Survey found that consumers on a low income (defined as under £17,500) were more likely to say that they did not shop around for better deals compared to those on higher incomes. It found a similar pattern for elderly consumers; 74% of those aged 75+ said they shop around ‘not very much or not at all’. (see Tackling the loyalty penalty: response to a super-complaint made by Citizens Advice on 28 September 2018, December 2018, chapter 4 for more details.

Evidence from Ofcom suggests that, in both mobile and broadband, elderly consumers (aged 65+) are significantly more likely to be longstanding customers. As we set out in our super-complaint response, they therefore may be at risk of paying a loyalty penalty:

- in mobile, 43% of those aged 65+ had been with their provider for 10 years or more, compared with 21% of under 65s;

- in broadband, 55% of those aged 65+ had changed their provider, versus 67% of those under 65. This age group are also significantly less likely than average to have considered deals from other providers (17% vs 28%), or to have looked at deals/offers from their own provider (10% vs 14%) (Ofcom, core switching tracer 2018, 30 August to 30 September 2018).

Evidence on switching for other groups of vulnerable consumers - such as those on low incomes - is not currently available. Ofcom is currently conducting further work to understand whether or not potentially vulnerable consumers (including those who are elderly) pay higher prices than other consumers, and to explore the link between price paid and length of time spent with a provider. This should help to address some of the evidence gaps. (for more details, see Ofcom, Helping consumers to get better deals in communications markets: mobile handsets, September 2018; Ofcom, Helping consumers get better deals: consultation on end-of-contract and annual best tariff notifications, and proposed scope for a review of pricing practices in fixed broadband, December 2018, page 121-136)

Overall, while there are gaps in the evidence base, particularly in relation to mental health, the available evidence suggests that vulnerable consumers are less likely to engage and switch than other consumers across a range of regulated or essential services markets such as energy and financial services. As a result, they are more at risk of paying a loyalty penalty in these markets.

The prices paid by vulnerable consumers and the ‘poverty premium’

There is less evidence available on the extent to which vulnerable consumers pay higher prices than other consumers. Most of the analysis that has been carried out has focussed on whether low income consumers pay more for the same goods and services than high income consumers, a phenomenon known as the ‘poverty premium’. [footnote 28]

In 2016, the University of Bristol identified six areas where the poverty premium arises: household fuel, telecoms, insurance, grocery shopping, access to money and use of higher-cost credit (see also Davies, Finney and Hartfree, Paying to be poor, 2016. The study estimated the overall average cost of the poverty premium to be £490 per year per household, increasing to £750 for some households. However, this research did not have access to information on actual expenditure and prices paid by consumers on low incomes, and how these compared with consumers in other income groups. The Social Market Foundation (SMF) subsequently published a report on a methodology for measuring the poverty premium, reviewing and building on a range of previous studies. It concluded that the University of Bristol’s methodology risked overestimating the size of the poverty premium.

Both the SMF and Bristol University studies have made valuable contributions to understanding the components of the poverty premium and variations in the exposure of consumers with low incomes to these components. However, this work has demonstrated that it is very difficult to produce a robust estimate of the poverty premium without having comprehensive data on the prices actually paid by different categories of consumer. In this respect, it is worth highlighting two pieces of analysis that have used extensive data sets. These cover energy and groceries, two very large items of expenditure for low income households (see ONS, Table 3.2 Detailed household expenditure as a percentage of total expenditure by disposable income decile group UK, financial year ending 2017. There was found to be a poverty premium in energy, but not in groceries.

Estimates of the link between income and prices in energy and groceries

We carried out an analysis of the poverty premium in energy using data from 2014 collected in our energy market investigation. As highlighted earlier, low income customers are more likely to be disengaged from the energy market and hence to pay an expensive default tariff. Low income customers are also more likely to prepay for energy, and hence pay higher prices than other customers. On the other hand, low income customers are more likely to be in receipt of the Warm Home Discount, which provides a government-mandated rebate on the bill. Excluding those who received the Warm Home Discount, we calculated that in 2014 dual fuel customers on incomes below £18000 a year would have paid on average £26 more for a year of typical household consumption than those on incomes above £18000, and £38 more than those on incomes above £36,000.

A study carried out by the IFS used Kantar World panel data to investigate the cost paid by lower and higher income households for their food and grocery shopping. This study used barcode-level data to compare prices paid on identical grocery products across Great Britain in 2006 and found that there was variation in prices paid (either due to price differences between stores or temporary special offers) and that on average lower income households paid slightly less than higher income households for the same products (Taking average monthly prices over calendar year 2006, those with incomes below £10,000 paid on average 0.9% less than those with incomes over £60,000).

See footnotes. [footnote 30] [footnote 31] [footnote 32]

These two contrasting results highlight an important point: the existence and size of the poverty premium in specific markets is, ultimately, an empirical question. And yet, outside of these two pieces of work, there are few examples of robust empirical measures of this phenomenon, largely because of a lack of adequate data. Given the strong public and political interest in whether low income consumers – and vulnerable consumers more generally - suffer from poor outcomes across a range of markets, we believe this is a significant gap in the evidence base.

Addressing the evidence gap on outcomes

As set out above, a major challenge we have encountered is the lack of comprehensive, consistent data on which groups of consumers experience poor outcomes across different markets. Currently, regulators can address this question for some markets, through major market studies or investigations that allow price data to be linked to consumer surveys that include demographic characteristics such as income, and age. The energy market investigation referred to above is an example. These can give powerful insights but are conducted on an ad hoc basis, with evidence becoming out of date over time. Furthermore, such studies do not allow for comparisons across markets.

We have therefore considered the scope for identifying outcomes for different categories of consumer on an ongoing basis, and across markets. In developing our views on how best to do this, we have drawn on advice we commissioned from NatCen and IFS on the scope for producing a more robust measure of the poverty premium across markets, and our own analysis.

The view we have reached is that the best way of producing this evidence is likely to be through matching price and other transaction data from suppliers across a range of markets with a recurring survey that contains comprehensive information about respondents’ demographic and other characteristics. These characteristics would include for example information on respondents’ income, age, mental health and any physical disability/health conditions.

In our response to the loyalty penalty super-complaint we made a recommendation for a feasibility assessment to be undertaken for such a data matching exercise. We have now agreed that the CMA will take this work forward, working closely with the FCA, Ofcom, Ofgem and Ofwat. We will also engage with the UK Regulators Network (UKRN) as a convening forum and to keep all regulators up to date on our progress.

The feasibility assessment will consider a number of factors, including: the choice of survey; scope (eg which sectors to collect data from, and which suppliers to include for each sector); the price data that could be collected and whether other transactional data could be included; the mechanics of the data matching process; legal vires; and practicalities such as the costs, resource requirements and timeframes for a full data matching exercise on an regular basis.

In relation to the choice of survey, two potential survey options we will be considering as part of our feasibility assessment are:

- the Understanding Society survey. This is a large scale Economic and Social Research Council-funded longitudinal survey of around 40,000 households across the UK. It is run on an annual basis to provide evidence of the experiences of the UK population over time, through a questionnaire that covers a wide range of themes, providing a rich source of information

- the ONS Living Costs and Food Survey (LCFS), which is conducted throughout the year and across the UK. The LCFS provides a rich source of information on UK households’ spending patterns and cost of living, collected via a face to face questionnaire.

There will be practical challenges to consider in assessing the suitability of this approach, but, if feasible, it would potentially provide a number of significant benefits. In particular, linking price data from several markets to a high quality recurring survey over time would allow us to compare outcomes across these markets, to identify whether the same groups of consumers are suffering from poor outcomes in different markets. It would also allow us to identify patterns and trends, including the longer term impact on outcomes associated with particular vulnerabilities, or the link between transient vulnerabilities such as mental health, and market outcomes.

Matching transaction data to a recurring survey has the further advantage of potentially reducing the need for ad hoc surveys to be undertaken across regulated markets. It would offer opportunities for understanding the experiences of vulnerable consumers over time and whether there are particular groups facing specific difficulties at a given point in time. It could also offer a baseline against which regulators could consider how and why particular problems are occurring, allowing for the identification of trends and potentially informing future case selection and remedy development.

Such an approach could have a broad range of potential applications. For example, as highlighted earlier, it could be used to provide a robust, consistent basis for measuring the poverty premium over time. It could also be used to assess outcomes associated with other dimensions of vulnerability, for example to determine whether a premium is paid by people with disabilities, or by other groups such as those with mental health problems, the elderly, people who are time poor, or have poor digital skills.

We will publish the conclusions of our feasibility study in the summer, as part of our wider progress update on the recommendations being taken forward from our super-complaint response.

Implications for remedy design

We have had valuable discussions with a range of organisations about potential remedies to address the challenges that vulnerable consumers face in markets. We have distilled some of the key themes in the form of five high level principles, to help guide our thinking in the future. These principles are also informed by our qualitative research findings and the work we carried out as part of our response to the loyalty penalty super-complaint.

Three of the five principles are about helping vulnerable consumers engage in markets by ‘making it easy’, to borrow a phrase used by Richard Thaler at our symposium on consumer vulnerability. This captures the simple insight that the key to helping vulnerable consumers is not just providing them with information, but making it easier for them to access the services and support that they need, and to shop around and switch. These principles are: ‘finding out what works’; using ‘inclusive design’ and making good use of ‘data and intermediaries’. The final two principles that emerged from our discussions and research are about business behaviour: ‘changing business practices’; and, where necessary, ‘regulating outcomes’ directly. We discuss each of these principles below.

Finding out what works

A key theme to emerge from our discussions relates to the importance of trialling and testing interventions, to find out what works. Testing can take a variety of forms, from qualitative research and focus groups, to the so called ‘gold standard’ of randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Whatever form it takes, greater use of testing is fundamental to effective remedy design.

The importance of exposing potential remedies to trialling and testing can be seen in the history of attempts by regulators to encourage customers to engage.[footnote 33] Early engagement measures that had not been tested have been found to have somewhat limited impact (Amelia Fletcher, The role of demand-side remedies in driving effective competition: a review for Which?, November 2016). However, some recent interventions that have been subject to RCTs have shown positive effects. For example, some of the prompts to consumers that Ofgem has trialled following the energy market investigation have been found to increase switching rates four-fold for some of the most disengaged consumers, while Ofgem’s collective switch trial produced even more positive results.

Ofgem collective switch trial results

Ofgem’s recent collective switch trial involved offering 50,000 disengaged customers a more favourable tariff that had been negotiated for them. Overall, the intervention increased the switching rates by a factor of 8 relative to the control group and, for some variants of the intervention, by a factor of 10 (We also consider the results of the trial in further detail in chapter 6 of our super-complaint response). This resulted in 22% of customers switching and is the most successful Ofgem trial to date. Further consideration of why this intervention was more successful than others have been is needed – it may be because of the tailored communications customers received, or the endorsement of a trusted intermediary in Ofgem, or a number of other factors.

These results suggest that there is further scope for public sector intermediaries to support consumer engagement through the organisation of collective switches.

While as a regulatory community we have improved our testing of remedies, we recognise that there is still room for improvement. In particular, there is a need for more granular information about which groups of consumer respond to particular types of intervention. Key to this is ensuring that demographic and socio-economic information is collected from participants in remedy trials and tests in the future.

Inclusive design

A key theme arising from our work is that there is no such thing as an ‘average’ vulnerable consumer. Consumer vulnerability is multidimensional, and the challenges that individuals face in engaging with markets are varied and complex. When it comes to designing remedies and providing broader support for vulnerable consumers, we therefore need to be mindful of the needs of a broad range of consumers. The principle of ‘inclusive’ or ‘universal’ design is helpful here. This involves designing products or services so they are accessible to, and usable by, as many people as possible.

One example is communication: the right communication channel can potentially differ significantly for different groups of vulnerable consumer. As set out earlier, people with mental health problems can prefer electronic means of communication, as they create less anxiety than telephone interactions, or letters (which tend not to get opened)(Money and Mental Health Policy Institute, Access essentials: giving people with mental health problems equal access to vital services, July 2018). Offering communication channels such as email, text messaging, mobile apps such as WhatsApp or web-based interactions could therefore help consumers with mental health problems to engage with suppliers, access the support that they need, and potentially get better market outcomes as a result. In contrast, for others, more traditional means of communication are right. Part of the success of Ofgem’s recent collective switch trial may have been due to the fact that individuals were given a choice of routes to switch (71% of switchers switched over the phone while 29% switched online. Customers received letters informing them of the personalised savings they could make if they switched to the collective deal).

The importance of how communications are designed also came out in our testing of prompts in our qualitative research. While generally prompts were seen in a positive light, participants raised concerns about missing a prompt or dismissing it as marketing if they were in email form or designed in a particular way that appeared to be advertising.

Emails are no good, I get spam for everything especially from [telecom provider X] and [telecom provider Y] so I tend to ignore emails.

Qualitative research participant, physical disability, aged 25-34, London

Inclusive design also helps to address a key area of challenge which was highlighted in our research: that vulnerable consumers (particularly those with mental health problems) often do not disclose their vulnerability to suppliers. By making access to services easier for consumers generally, the need for disclosure may be reduced. For example, providing different choices of communication channel can help to empower those consumers, such as those with mental health problems, who can struggle to engage with suppliers over the phone. Offering a range of channels can mean that those with complex needs can also access support in the format that works for them, such as face to face.

However, there can also be a need to consider bespoke remedies or additional protections for different groups of vulnerable consumers where appropriate. At our roundtable with MMHPI, for example, we considered a variety of interventions that may help those who are prone to addictive and compulsive behaviour, including the creation of the option for such individuals to put themselves on registers which would require suppliers to give them a ‘cool off’ period before a particular purchase can be completed.