Households below average income series: quality and methodology information report FYE 2023

Updated 27 March 2025

Introduction

The Households Below Average Income (HBAI) report presents information on living standards in the United Kingdom and is the foremost source for data and information about household income, and inequality in the UK. It provides annual estimates on the number and percentage of people living in low-income households.

HBAI statistics incorporate widely used, international standard measures of low income and inequality. They provide a range of measures of low income, income inequality, and material deprivation to capture different aspects of changes to living standards. The current series started in Financial Year Ending (FYE) 1995 and so allows for comparisons over time, as well as between different groups of the population.

The statistics are based on the Family Resources Survey (FRS), whose focus is capturing information on incomes, and as such captures more detail on different income sources compared to other household surveys. The FRS captures a lot of contextual information on the household and individual circumstances, such as employment, education level and disability. This is therefore a very comprehensive data source allowing for a lot of different analysis.

This report provides detailed information on key quality and methodological issues relating to HBAI data. Information on the FRS methodology is available in the FRS Background Information and Methodology.

Comparing official statistics across the UK

All official statistics from the HBAI for the UK and constituent countries in this publication are considered by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) as “Fully Comparable at level A*” of the UK Countries Comparability Scale (with the exception of measures estimated on a before housing cost (BHC) basis for Northern Ireland, due to differing treatment of water rates).

Accredited Official Statistics

These Accredited Official Statistics were independently reviewed by the Office for Statistics Regulation in November 2012. They comply with the standards of trustworthiness, quality and value in the Code of Practice for Statistics and should be labelled ‘accredited official statistics’. Accredited official statistics are called National Statistics in the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007.

OSR introduced the term ‘Accredited Official Statistics’ to describe National Statistics in September 2023. This was done following OSR’s review of the National Statistics designation and subsequent designation refresh project, which found the term ‘National Statistics’ was not well understood by users of statistics.

It is DWP’s responsibility to maintain compliance with the standards expected of Accredited Official Statistics. If DWP becomes concerned about whether these statistics are still meeting the appropriate standards, we will discuss any concerns with the Office for Statistics Regulation. Accredited Official Statistics status can be removed at any point when the highest standards are not maintained, and reinstated when standards are restored.

Acknowledgements

As in previous years, the DWP would like to thank the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) for the substantial assistance that they have provided in checking and verifying the income data and grossing factors underlying the main results in this edition.

We are also grateful to HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) for the provision of aggregated data from the Survey of Personal Incomes.

Users and uses

HBAI is a key source for data and information about household income and inequality and is used for the analysis of low income by researchers and the Government. Users include: policy and analytical teams within the DWP, the Devolved Administrations, other Government departments, local authorities, Parliament, academics, journalists, and the voluntary sector.

The Department for Work and Pensions’ responsibilities include understanding and dealing with the causes of poverty rather than its symptoms, encouraging people to work and making work pay, encouraging disabled people and those with ill health to work and be independent, and providing a decent income for people of pension age and promoting saving for retirement. Progress towards these responsibilities will affect these results.

The key uses of the published statistics and datasets are:

-

to provide detail on the overall household income distribution and low- income indicators for different groups in the population;

-

for international comparisons; and

-

for parliamentary, academic, voluntary sector and lobby group analysis. Examples include using the HBAI data to examine income inequality, the distributional impacts of fiscal policies and understanding the income profile of vulnerable groups.

The first three of the four income-related measures included under section 4 of the Welfare Reform and Work Act 2016.

The four measures cover the percentage of children in the United Kingdom:

a) who live in households whose equivalised net income for the relevant financial year is less than 60% of median equivalised net household income for that financial year;

b) who live in households whose equivalised net income for the relevant financial year is less than 70% of median equivalised net household income for that financial year, and who experience material deprivation;

c) who live in households whose equivalised net income for the relevant financial year is less than 60% of median equivalised net household income for the financial year beginning 1 April 2010, adjusted to take account of changes in the value of money since that financial year; and

d) who live in households whose equivalised net income has been less than 60% of median equivalised net household income in at least 3 of the last 4 survey periods.

Definitions for relevant key terms in the Act are consistent with those given in the Glossary, Income Definition, Equivalisation, and Combined Low income and Child Material Deprivation sections of this report.

Data for reporting against the fourth measure will be released via the Income Dynamics publication.

Further details of the uses of HBAI statistics are given in Annex 3.

What do you think?

We are constantly aiming to improve this report and its associated commentary. We would welcome any feedback you might have and would also be particularly interested in knowing how you make use of these data to inform your work. Please contact us via email: team.hbai@dwp.gov.uk.

New for this publication

Family Resources Survey (FRS) fieldwork during FYE 2023

In Great Britain, survey fieldwork operations used face-to-face interviewing as the preferred method of data collection for the duration of the year. Telephone interviewing was retained as an alternative based on household preference and (in the first few months) interviewer availability. In Northern Ireland, a return to prioritising face-to-face interviewing was rolled out fully by interviewers from July 2022. Across the UK, 72% of FRS households were interviewed face-to-face during FYE 2023.

This year, we have enhanced confidence in data quality due to the return of traditional fieldwork methods and the larger achieved sample size of 25,000 households, some 30% larger than was achieved in FYE 2020, and 50% higher than FYE 2022. As with other years, we have completed extensive quality assurance of all published estimates, including comparing changes with external data sources, and analysing subgroups in detail. The achieved sample compares well with FYE 2020, and representativeness has improved on what was observed during the pandemic.

We continue to advise users that changes in estimates over recent years should be interpreted being mindful of the differences in data collection approaches across the period and the effect this had on sample composition. Details of this can be found in the technical reports which were issued alongside the statistical releases covering the pandemic. In this report we continue to make assessments of observed changes in the data compared with both FYE 2022 and with pre-pandemic trends and estimates.

Annex 5 in this report provides more detail on the use of a mixed mode in the FRS in FYE 2023, how this affected the overall FRS sample, and the degree of impact this had on the HBAI statistics.

Cost of Living Support Schemes

During FYE 2023 the UK Government announced and implemented additional support to families with several cost of living support schemes, depending on people’s circumstances. These payments are included in the HBAI estimates of household income, and more information is available in the Income Definition section of this document.

Most of the schemes were introduced at pace, in a timeframe which made it difficult to adapt the FRS questionnaire to capture them. As each support scheme came with clear eligibility guidelines, receipt of the payments was imputed based on respondent characteristics. Further details on the methodology can be found in the FRS Background Information and Methodology document.

Educational Attainment

Development work to improve reporting on categories of level of education identified a separate issue with the FRS variable EDUCQUAL. This variable is used to present estimates of low income for working-age adults by their level of educational attainment. The estimates have been withdrawn from the FYE 2023 publication, affecting the following tables: 5.3db BHC, 5.3db AHC, 5.6db, and 5.9db. The breakdown has also been removed from Stat Xplore. We will provide an update on restoring the estimates when validation checks are complete.

For the survey period covering the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, EDUCQUAL was used to adjust our weighting methodology to correct for the over-representation of degree educated working-age people in the FRS sample. Following the reintroduction of FRS face-to-face interviewing for FYE 2023, this additional weighting was no longer required, and the grossing has returned to the FYE 2020 position.

We are investigating how identified issues with EDUCQUAL may have affected previous releases and will update in due course.

Resumption of the material deprivation time series

The measurement of material deprivation was affected by restrictions introduced in response to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic.

For FYE 2023, responses to the survey items asked as part of establishing the level of material deprivation are unaffected by the pandemic. We have resumed our material deprivation time series by comparing changes in the estimates directly with FYE 2020, when responses were last comparable.

We have chosen to display this in affected charts by presenting estimates for the pandemic period (FYE 2021 and FYE 2022) as individual data points. We advise users not to make a direct comparison of changes in material deprivation estimates with those published prior to the pandemic.

Other points of note

Following our decision to not publish breakdowns of the FYE 2021 HBAI estimates, all three-year rolling averages calculated and published for any period including FYE 2021 continue to be based on two data points only. Next year the calculation will revert to using three data points.

Using and Interpreting HBAI Results

Guide to published tables

A wide range of ODS supported tables are available alongside this release, breaking down the results presented in this report for different demographic characteristics. This includes breakdowns of the statistics by region, ethnic group, family type, and economic status. All tables can be downloaded via the HBAI homepage (see Directory of Tables link on this webpage to locate tables referenced in the following pages and to generally find the desired tables). Results are available for most series back to FYE 1995.

UK-level HBAI data is also available between FYE 1995 and FYE 2023 on the Stat-Xplore online tool. You can use Stat-Xplore to recreate measures in our static tables and also create your own bespoke HBAI analysis.

The source data behind these statistics is available for download and further analysis via the UK Data Service.

Note that unpublished FYE 2021 data is excluded from both the tables and Stat-Xplore. The HBAI dataset underpinning the headline estimates for FYE 2021 remains available for expert users and researchers in the UK Data Service, and we recommend consulting the FYE 2021 technical report for more guidance on use and interpretation of sub-national estimates.

Estimates of the change in the percentage and number that are significantly different from a previous year are shown with the notation [s]. Changes marked with an [s] are unlikely to have occurred as a result of chance. Changes that are not significant are shown with the notation [ns].

The series started in FYE 1995 and so allows for comparisons over time, as well as between different groups of the population.

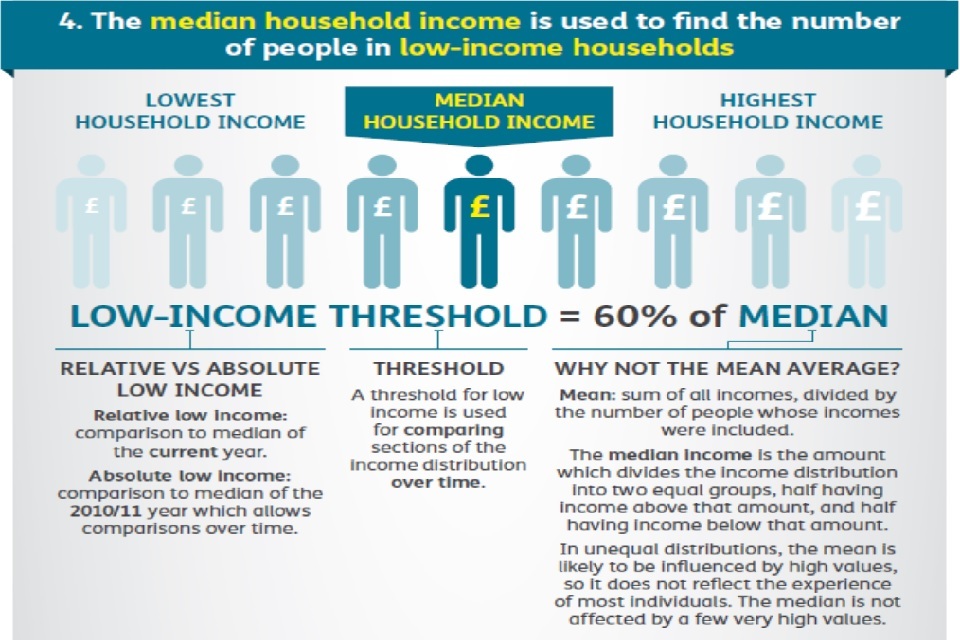

What do we mean by average?

In HBAI, the term ‘average’ is used to describe the median. This divides the population of individuals, when ranked by income, into two equal-sized groups, and unlike the mean is not affected by extreme values.

HBAI measures

There are a range of measures of low income, income inequality, and material deprivation to capture different aspects of changes to living standards:

-

Relative low income measures the number and proportion of individuals who have household incomes below a certain proportion of the average in that year - and is used to look at how changes in income for the lowest income households compare to changes in incomes near the ‘average’. In the HBAI report we concentrate on those with household incomes below 60 per cent of the average. Information on those with household incomes below 50 and 70 per cent of the average is available in the detailed tables published on the HBAI homepage.

-

Absolute low income measures the proportion of individuals who have household incomes a certain proportion below the average in FYE 2011, adjusted for inflation. It is used to look at how changes in income for the lowest income households compare to changes in the cost of living. In the HBAI report we concentrate on those with household incomes below 60 per cent of the average FYE 2011 income. Information on those with household incomes below 50 and 70 per cent of the average is available in the detailed tables published on the HBAI homepage.

Rounding

Due to rounding, the estimates of change in percentages or numbers of may not equal the difference between the total percentage or number of individuals for any pair of years.

The publication and tables follow the following conventions:

[low] the estimate is less than 50,000 or the percentage is less than 0.5 per cent

[u] the estimate is not available due to small sample sizes (fewer than 100)

[x] the estimate is not available. In FYE 2021 this was due to sample quality concerns across different household sizes and compositions.

Population estimates are rounded to the nearest 0.1 million.

Percentages are rounded to the nearest 1 per cent.

Key terminology

Income

This is measured as total weekly household income from all sources after tax (including child income), national insurance and other deductions. An adjustment called ‘equivalisation’ is made to income to make it comparable across households of different size and composition.

Median

Median household income divides the population, when ranked by equivalised household income, into two equal-sized groups. The median is the value at the very middle of the distribution.

Deciles and Quintiles

These are income values which divide the whole population, when ranked by household income, into equal-sized groups. This helps to compare different groups of the population.

Decile and quintile are often used as a standard shorthand term for decile/quintile group.

Decile groups are ten equal-sized groups - the lowest decile describes individuals with incomes in the bottom 10 per cent of the income distribution.

Quintile groups are five equal-sized groups - the lowest quintile describes individuals with incomes in the bottom 20 per cent of the income distribution.

Income distribution

The spread of incomes across the population.

Equivalisation

Equivalisation adjusts incomes for household size and composition, taking an adult couple with no children as the reference point. For example, the process of equivalisation would adjust the income of a single person upwards, so their income can be compared directly to the standard of living for a couple.

Housing costs

Housing costs include rent, water rates, mortgage interest payments, buildings insurance payments and ground rent and service charges. A full list can be found in the glossary at the end of this report.

Benefit unit and households

HBAI presents information on an individual’s household income by various household and benefit unit (family) characteristics. There are important differences between households and benefit units.

Household The definition of a household used in the FRS is ‘one person living alone or a group of people (not necessarily related) living at the same address who share cooking facilities and share a living room, sitting room, or dining area’. So, for example, a group of students with a shared living room would be counted as a single household even if they did not eat together, but a group of bed-sits at the same address would not be counted as a single household. A household may consist of one or more benefit units, which in turn will consist of one or more people (adults and children).

Family or Benefit Unit A family in the FRS is defined as ‘a single adult or couple living as married and any dependent children’. A dependent child is aged 16 or under, or is 16 to 19 years old, unmarried and in full-time non-advanced education. This is consistent with the DWP term “benefit unit”, which is a standard grouping used for assessing benefit entitlement.

So, for example, a husband and wife living with their young children and an elderly parent would be one household but two families or benefit units. The husband, wife and children would constitute one benefit unit and the elderly parent would constitute another.

Other terms

For more information on these and other terms used throughout the report, see the glossary at the end of this report, and the infographics explaining key terms.

Issues to consider

The following issues should be considered when using the HBAI:

- Impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on FYE 2021 and FYE 2022 statistics: Fieldwork operations for the Family Resources Survey (FRS) were changed in response to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and the introduction of national lockdown restrictions in March 2020. The established face-to-face interviewing approach employed on the FRS was suspended and replaced with telephone interviewing from April 2020 for the whole of the 2020 to 2021 and 2021 to 2022 survey year. This change impacted on both the size and composition of the achieved samples for those years. The data published for FYE 2021 is limited to headline measures and not available in our supplementary tables or on our Stat-Xplore tool. It is, however, still deposited for download by users in the UK Data Service. We recommend caution is exercised when interpreting any data published for these survey years, particularly when making comparisons with years prior to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. This methodology report does not detail the effect the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic had on the sample data and estimates. For this information, users are advised to consult the technical reports which accompanied the FYE 2021 and FYE 2022 publications. Detail on the methodological changes made during the period to take account of new income sources (such as Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme) and temporary changes to the HBAI grossing regime to improve sample representativeness are provided later in this document.

- Lowest incomes: Comparisons of household income and expenditure suggest that those households reporting the lowest incomes may not have the lowest living standards. The bottom 10 per cent of the income distribution should not, therefore, be interpreted as having the bottom 10 per cent of living standards. Results for the bottom 10 per cent are also particularly vulnerable to sampling errors and income measurement problems. For HBAI tables, this will have a relatively greater effect on results where incomes are compared against low thresholds of median income. For this reason, compositional and percentage tables using the 50 per cent of median thresholds have been italicised to highlight the greater uncertainty. We have also presented money value quintile medians in Table 2.3ts on three-year averages to reflect this uncertainty (any period including FYE 2021 is based on two data points).

- Adjustment for inflation: As advised in a Statistical Notice published in May 2016, from FYE 2015 HBAI made a methodological change to use variants of CPI when adjusting for inflation. Prior to the FYE 2015 HBAI publication variants of RPI were used to adjust for inflation. This change followed advice from the UK National Statistician that use of RPI should be discontinued in statistical publications. Full details on the impact on this methodological change, together with estimates for trends in income and absolute low income under both the old and new methodologies, are presented in Annex 4 of the FYE 2015 HBAI Quality and Methodology Report.

- Benefit receipt: Relative to administrative records, the FRS is known to under-report benefit receipt. However, the FRS is the best source for looking at benefit and tax credit receipt by characteristics not captured on administrative sources, and for looking at total benefit receipt on a benefit unit or household basis. It is often inappropriate to look at benefit receipt on an individual basis because means-tested benefits are paid on behalf of the benefit unit. DWP published research (Working Paper 115) which explores the reasons for benefit under-reporting with the aim of improving the benefits questions included within the FRS. Table M.6a of the FRS publication presents a comparison of receipt of state support between FRS and administrative data. Methodology Table M.6b compares the average weekly receipt of state support in the FRS with the average weekly receipt of state support from the administrative data sources. Some benefit types have not been included in this analysis because no directly comparable administrative data source is available.

- Self-employed: All analyses in the HBAI publication include the self-employed. A proportion of this group are believed to report incomes that do not reflect their living standards and there are also recognised difficulties in obtaining timely and accurate income information from this group. This may lead to an understatement of total income for some groups for whom this is a major income component, although this is likely to be more important for those at the top of the income distribution. There is little difference in the overall picture of proportions in low-income households when analysis is performed either including or excluding the self-employed.

- Savings and investments: The data relating to investments and savings should be treated with caution. Questions relating to investments are a sensitive section of the questionnaire and have a low response rate. A high proportion of respondents do not know the interest received on their investments. It is likely that there is some under-reporting of capital by respondents, in terms of both the actual values of the savings and the investment income. This may lead to an understatement of total income for some groups for whom this is a major income component, such as pensioners, although this is likely to be more important for those at the top of the income distribution.

- Methodological change for FYE 2020 (FRS savings and investments variable used in HBAI): The level of savings and investments, for some families (benefit units) and households was estimated using a slightly different methodology from FYE 2020 than in previous years. The new method more accurately estimates savings in current accounts and basic bank accounts. It should be noted that savings and investments breakdowns from FYE 2020 are not directly comparable with those for previous years.

- Comparisons with National Accounts: Table 1.2a shows comparisons between growth in Real Household Disposable Income and real growth in HBAI mean BHC unequivalised income. For some years, income growth in the HBAI-based series appears lower than the National Accounts estimates. The implication of this is that absolute real income growth could be understated in the HBAI series. Comparisons over a longer time period are believed to be more robust.

- High incomes: Comparisons with His Majesty’s Revenue and Customs’ Survey of Personal Incomes (SPI), which is drawn from tax records, suggest that the FRS under-reports the number of individuals with very high incomes and understates the level of their incomes. There is also some volatility in the number of high-income households surveyed. Since any estimate of mean income is very sensitive to fluctuations in incomes at the top of the distribution, an adjustment to correct for this is made to ‘very rich’ households in FRS-based results using SPI data. The median-based low-income statistics are not affected.

-

Working status: DWP and ONS have jointly investigated the reasons for the FRS consistently giving higher estimates than the Labour Force Survey (LFS) of the percentage of children in workless households. A report on this investigation found that the main reasons for the divergence were:

- FRS unweighted data identifying a higher proportion of children in lone parent families, who have a much higher worklessness rate, than does LFS;

- FRS unweighted data showing a higher worklessness rate, in both lone parent and couple with-children families, than LFS;

- LFS employing a grossing regime which substantially reduces the proportion of children in lone parent households, and thereby in workless households; whereas the FRS grossing regime has less of an effect in reducing these proportions;

- The LFS grossing regime also reduces the worklessness rate in lone parent families; whereas the FRS grossing regime has less clear-cut effects.

- Gender analysis: The HBAI assumes that both partners in a couple benefit equally from the household’s income and will therefore appear at the same position in the income distribution. Research has suggested that, particularly in low-income households, the assumption with regard to income sharing is not always valid as men sometimes benefit at the expense of women from shared household income. This means that it is possible that HBAI results broken down by gender could understate differences between the two groups. See, for instance “Purse or Wallet? By Gender Inequalities” by Goode, J., Callender, C. and Lister, R. (1998) and the Distribution of Income in Families on Benefits by JRF/Policy Studies Institute.

- Students: Information for students should be treated with some caution because they are often dependent on irregular flows of income. Only student loans are counted as income in HBAI (with both the maintenance and tuition parts of the loan included), any other loans taken out are not. The figures are also not necessarily representative of all students because HBAI only covers private households and this excludes halls of residence.

- Elderly: The effect of the exclusion of the elderly who live in residential homes is likely to be small overall except for results specific to those aged 80 and above.

- Ethnicity analysis: Smaller ethnic minority groups exhibit year-on-year variation which limits comparisons over time. For this reason, analysis by ethnicity is usually presented as three-year averages. Please note that following the decision to not publish breakdowns of the FYE 2021 estimates, all three-year averages calculated and published for any period including FYE 2021 are based on two data points only.

- Disability analysis: No adjustment is made to disposable household income to take account of additional costs that may be incurred due to the illness or disability in question. This means that using income as a proxy for living standards for these groups, as shown here, may be somewhat upwardly biased. Analysis excluding Disability Living Allowance and Attendance Allowance from the calculation of income has been published as part of the suite of online HBAI ODS (not available for FYE 2021).

- Regional analysis: Disaggregation by geographical regions is usually presented as three-year averages. This presentation has been used as single-year regional estimates are considered too volatile. This issue was discussed in Appendix 5 of the FYE 2005 HBAI publication, where regional time series using three-year averages were presented. Although the FRS sample is large enough to allow some analysis to be performed at a regional level, it should be noted that no adjustment has been made for regional cost of living differences. It is therefore assumed that there is no difference in the cost of living between regions, although the AHC measure will partly consider differences in housing costs. Analysis at geographies below the regional level is not available from this data. Please see the Children in Low-Income Families publication for local level geographies. Please note that following the decision to not publish breakdowns of the FYE 2021 estimates, all three-year averages calculated and published for any period including FYE 2021 are based on two data points only.

- Household food security and food bank usage: The individual level statistics presented in our tables relate to the household’s food bank usage or household food security. The circumstances of the household are applied to all individuals within that household. The questions do not ask, for example, about the food bank usage of the individual or food bank usage needs of children. It should also be noted that the statistics presented exclude shared households, such as a house shared by a group of professionals.

- Changes to deflators: Since the HBAI FYE 2018 publication, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) have made some very minor revisions to the bespoke Consumer Price Index (CPI) series we use to make real-terms income comparisons within and between survey years. However, because the effect of these revisions on low-income measures is negligible no revisions have been made to the deflators used in HBAI. See the following ONS update for more details.

- Revision to FYE 1995 to FYE 2019 due to treatment of income from child maintenance: In HBAI FYE 2020 a minor methodological change was made to capture all income from child maintenance. This resulted in more income from child maintenance being included, in turn slightly increasing some household incomes and so tending to slightly reduce low-income rates for families with children. The full back series back to FYE 1995 was revised so that comparisons over time are on a consistent basis across the full time series. This means that figures for FYE 1995 to FYE 2019 may be slightly different to the equivalent figures in publications issued prior to FYE 2019. Please refer to HBAI Quality and Methodology Information Report for FYE 2020 for more information.

- Income from dividends: From FYE 2022, income received from director’s dividends is included in the estimates following an addition to the Family Resources Survey. From FYE 2023 there has been an adjustment to the treatment of dividends for a small group of respondents: in cases where respondents are all of (i) self-employed, and (ii) state they are directors, and (iii) where their calculated income rests on profits from annual accounts, as opposed to the other figures reported; then it is assumed that the profit figure is already inclusive of any dividend also reported. The income is treated as income from earnings. More information on the treatment of specific income sources can be found in FRS Background Information and Methodology.

Survey Data

The statistics in the HBAI report come from the Family Resources Survey (FRS), a representative survey of 25 thousand households in the United Kingdom in FYE 2023. This was meaningfully higher than the over 16,000 achieved in FYE 2022. The achieved sample for FYE 2023 was short of the aim of 45,000 households but was still 30% above levels seen in the years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (typically 19,000-20,000). In general, this means that the degree of uncertainty around this year’s survey estimates is smaller than in the last two years.

The focus of the FRS is on capturing information on incomes and, as such, is the foremost source of income data and provides more detail on different income sources than other household surveys. It also captures a lot of contextual information on the household and individual circumstances, such as employment, education level and disability. This is therefore a very comprehensive data source allowing for a lot of different analysis.

Surveys gather information from a sample rather than from the whole population. The sample is designed carefully to allow for this, and to be as accurate as possible given practical limitations such as time and cost constraints. Results from sample surveys are always estimates, not precise figures. This means that they are subject to a margin of error which can affect how changes in the numbers should be interpreted, especially in the short-term. The latest estimates should be considered alongside medium and long-term patterns.

In addition to sampling errors, consideration should also be given to non-sampling errors. Non-sampling errors arise from the introduction of some systematic errors in the sample as compared to the population it is supposed to represent. As well as response bias, such errors include inappropriate definition of the population, misleading questions, data input errors or data handling problems – in fact any factor that might lead to the survey results systematically misrepresenting the population. There is no simple control or measurement for such non-sampling errors, although the risk can be minimised through careful application of the appropriate survey techniques from the questionnaire and sample design stages through to analysis of results.

HBAI is based on data from a household survey and so subject to the nuances of using a survey, including:

- Sampling error. Results from surveys are estimates and not precise figures. Confidence intervals help to interpret the certainty of these estimates, by showing the range of values around the estimate that the true result is likely to be within. In general terms the smaller the sample size, the larger the uncertainty. Statistical significance is an attempt to indicate whether a reported change within the population of interest is due to chance. It is important to bear in mind that confidence intervals are only a guide for the size of sampling error.

- Non-response error. Prior to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, the FRS response rate each year was around 50 per cent. Following the change in mode because of pandemic, the FYE 2021 the response rate fell to 23% and in FYE 2022 it improved to 26%. In FYE 2023, the response rate was 25%. To correct for differential non-response, estimates are weighted using population totals.

- Survey coverage. The FRS covers private households in the United Kingdom. Therefore, individuals in nursing or retirement homes, for example, will not be included. This means that figures relating to the most elderly individuals may not be representative of the United Kingdom population, as many of those at this age will have moved into homes where they can receive more frequent help.

- Survey design. The FRS uses a clustered sample designed to produce robust estimates at former government office region (GOR) level. The FRS is therefore not suitable for analysis below this level.

- Sample size. Although the FRS has a relatively large sample size for a household survey, small sample sizes for some more detailed analyses may require several years of data to be combined to generate reliable estimates. From April 2011, the target achieved GB sample size for the FRS was reduced by 5,000 households, resulting in an overall achieved sample size for the UK of around 20,000 households from FYE 2012 onwards. We previously published an assessment concluding that this still allows core outputs from the FRS to be produced, though with slightly wider confidence intervals or ranges. The circumstances surrounding the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic resulted in a smaller achieved FRS sample size than pre-pandemic, with over 16,000 households in the FYE 2022 sample. This was an improvement on FYE 2021 where the achieved sample size was around 10,000 households. DWP had previously announced plans for a significant boost to the FRS sample size, with the aim to increase the achieved sample to 45,000 households annually, from April 2022. However the primary challenge to achieving this stemmed from recruiting and retaining sufficient interviewers: a number of factors conspired to cause existing interviewers to leave at a higher rate than previously, while at the same time it was hard to attract and retain new interviewers. The impact of this was that the level of field capacity required to manage the sample boost was not achieved. For FYE 2023 the achieved sample was 25,000 households. It remains the case that gaining household response has continued to be challenging in FYE 2024. The primary challenge remains the recruitment and retention of sufficient interviewers; versus the call on their time (and from all large social surveys, not just the FRS). Consequently, we expect a final achieved sample for the year of around 17,500 households, rather than the 20,000 originally intended. Please see the FRS release strategy for more information.

- Measurement error. The FRS is known to under-report certain income streams, especially benefit receipt. More detail can be found in Table M.6a and M.6b of the FRS report.

Further methodological details relating to the FRS are given in the FRS Background Information and Methodology.

Reporting Uncertainty

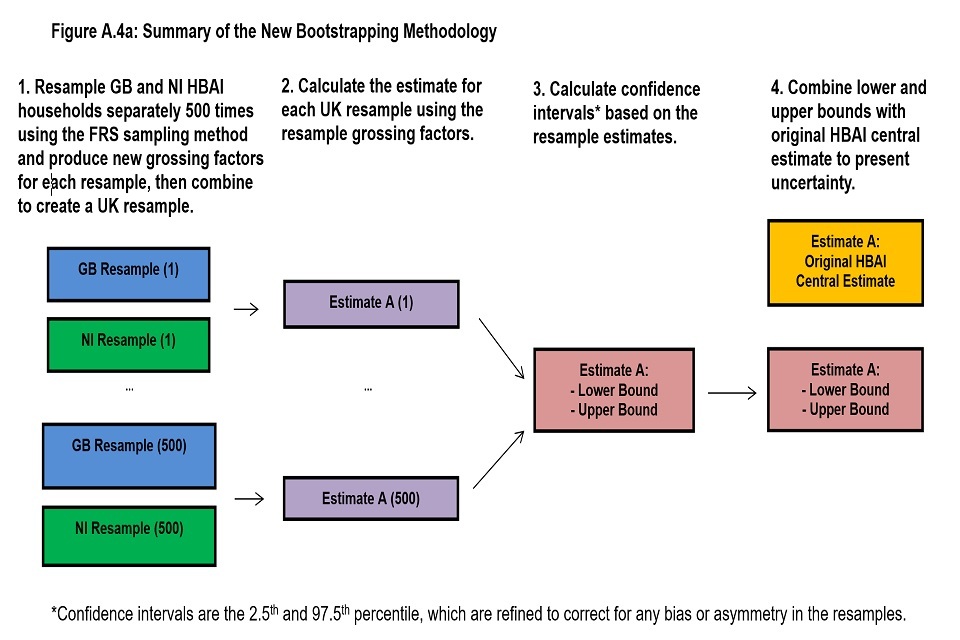

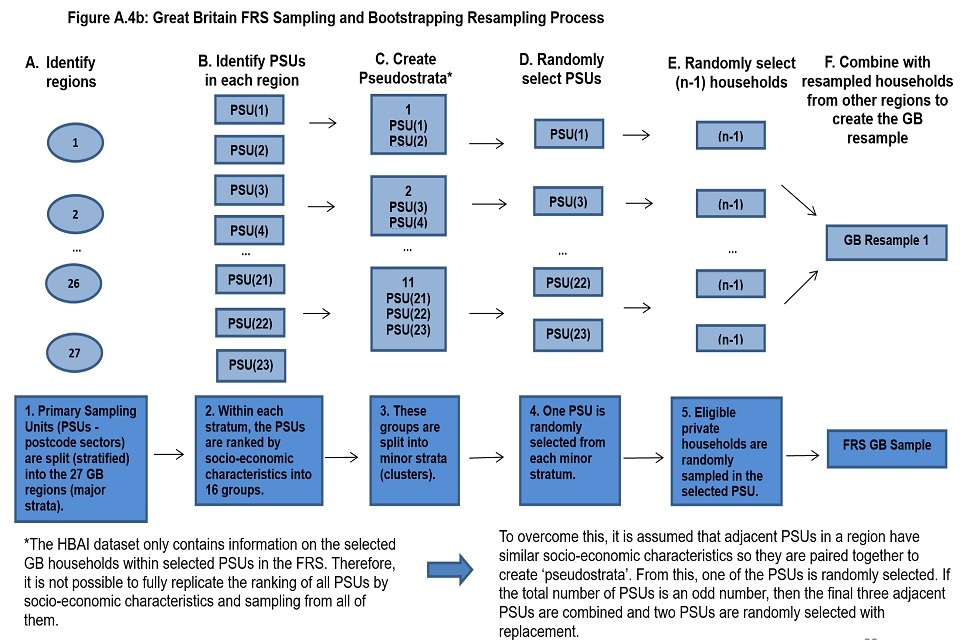

As above, survey results are always estimates, not precise figures and so subject to a level of uncertainty. Two different random samples from one population, for example the UK, are unlikely to give the same survey results, which are likely to differ again from the results that would be obtained if the whole population was surveyed. The level of uncertainty around a survey estimate can be calculated and is commonly referred to as sampling error.

We can calculate the level of uncertainty around a survey estimate by exploring how that estimate would change if we were to draw many survey samples for the same time period instead of just one. This allows us to define a range around the estimate (known as a “confidence interval”) and to state how likely it is that the real value that the survey is trying to measure lies within that range. Confidence intervals are typically set up so that we can be 95% sure that the true value lies within the range – in which case this range is referred to as a “95% confidence interval”. Annex 4 of this report provides further details on the Bootstrapping methodology used to estimate confidence intervals in HBAI, alongside estimates of the sampling error.

Population

The analyses in the HBAI report are primarily based on the FRS. Households in Northern Ireland (NI) were surveyed for the first time in the FYE 2003 survey year. A detailed analysis of observed trends, together with results for NI and the UK for the first three years of NI data can be found in Appendix 3 of the FYE 2005 HBAI publication.

The FRS time series in this publication are presented with discontinuities in the years where there is a change from GB to UK. Prior to FYE 2015, for some tables, estimates for NI were imputed for the years FYE 1999 to FYE 2002. This allowed for changes since FYE 1999 to be measured at the UK level. For further details, see Appendix 4 of the FYE 2005 HBAI publication. This imputation is no longer carried out from the FYE 2015 publication.

The survey covers the private household sector. All the results therefore exclude people living in institutions, e.g. nursing homes, halls of residence, barracks or prisons, and homeless people living rough or in bed and breakfast accommodation. The area of Scotland north of the Caledonian Canal was included in the FRS for the first time in the FYE 2002 survey year and, from the FYE 2003 survey year, the FRS was extended to include a 100 per cent boost of the Scottish sample. This has increased the sample size available for analysis at the Scottish level.

A further adjustment is that households containing a married adult whose spouse is temporarily absent, whilst within the scope of the FRS, are excluded from HBAI. Similarly, prior to the FYE 1997 data, households containing a self-employed adult who had been full-time self-employed for less than two months were excluded. This exclusion is no longer made because of the improvements in the self-employment questions in the FRS.

Grossing

The published HBAI analysis presents tabulations where the percentages refer to sample estimates grossed-up to apply to the whole population.

Grossing-up is the term usually given to the process of applying factors to sample data so that they yield estimates for the overall population. The simplest grossing system would be a single factor, e.g. the number of households in the population divided by the number in the achieved sample. However, surveys are normally grossed by a more complex set of grossing factors that attempt to correct for differential non-response at the same time as they scale up sample estimates.

The system used to calculate grossing factors for HBAI mirrors that of FRS grossing with two differences described below.

The system used to calculate grossing factors for the FRS divides the sample into different groups. The groups are designed to reflect differences in response rates among different types of households. The FRS stratified sample structure is designed to minimise differential non-response in the achieved sample. Grossing is then designed to account for residual differential non-response. They have also been chosen with the aims of DWP analyses in mind. The population estimates for these groups, obtained from official data sources, provide control variables. The grossing factors are then calculated by a process which ensures the FRS produces population estimates that are the same as the control variables.

As an example, the grossed number of men aged 35 to 39 would be consistent with the Office for National Statistics (ONS) estimate (see Table 1). Some adjustments are made to the original control total data sources so that definitions match those in the FRS, e.g. an adjustment is made to the demographic data to exclude people not resident in private households. It is also the case that some totals have to be adjusted to correspond to the FRS survey year.

A software package called CALMAR, provided by the French National Statistics Institute, is used to reconcile control variables at different levels and estimate their joint population. This software makes the final weighted sample distributions match the population distributions through a process known as calibration weighting. It should be noted that if a few cases are associated with very small or very large grossing factors, grossed estimates will have relatively wide confidence intervals.

As stated above, the system used to calculate grossing factors for HBAI mirrors that of FRS grossing with two differences. The first difference with FRS grossing is that the sample of households is smaller for HBAI purposes because households with spouses living away from home are excluded (see Population section above). The second difference is that separate control totals are introduced for ‘very rich’ households, so that the top end of the income distribution is more accurately reflected, which is particularly important for estimates of mean income or inequality as measured by the Gini coefficient.

As with the FRS, the grossing regime for HBAI currently uses population and household estimates based on the results of the 2011 Census. Prior to FYE 2013, 2001 census-based estimates were used. In addition, a review of FRS grossing was carried out on behalf of DWP by the ONS Methodological Advisory Service. In implementing the review recommendations, a number of relatively minor methodological improvements were implemented from FYE 2013.

The main changes implemented were as follows:

-

improvements to the categorisation of tenure control totals;

-

a full breakdown of the total number of households into each of the English regions (in addition breakdowns for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland); and

-

a new adjustment to account for the different rates of sampling in England and Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland.

A back-series of grossing factors calculated using the new methodology was created for each year back to FYE 2003 and are used in the HBAI publication tables from FYE 2013 onwards. Further details and analysis of the impact of these methodological changes are published in the grossing methodology review.

In developing the grossing regime, careful consideration has been given to the combination of control totals and the way age ranges, Council Tax bands and so on, have been grouped together. The aim has been to strike a balance so that the grossing system will provide, where possible, accurate estimates in different dimensions without significantly increasing variances.

There are some differences between the methods used to gross the Northern Ireland sample as compared with the Great Britain sample:

-

Local taxes in Northern Ireland are collected through the rates system, so Council Tax Band as a control variable is not applicable.

-

Northern Ireland housing data are based largely on small sample surveys. It is not desirable to introduce the variance of 1 survey into another by using it to compute control totals, therefore, tenure type has not been used as a control variable.

Details of the grossing regime for Northern Ireland are shown in Table 2.

FYE 2023 Grossing Regime

For FYE 2023, population estimates used to weight HBAI are still primarily based on mid-year estimates rolled forward from the 2011 Census to mid-2019 and subnational population projections (2018-based) for mid-2020 and mid-2021. For England, Wales, and Northern Ireland the projection for mid-2021 was rolled forward to mid-2022 using official estimates of population change. For Scotland, the mid-2022 population estimates are taken from the subnational projections (2018-based). Note: This series of population estimates do not take account of the 2021 and 2022 Censuses across the UK. They are bespoke estimates provided to DWP by ONS which was necessary due to information from the Scottish 2022 Census being unavailable for use.

The mid-year estimates cover the usual resident population and were adjusted to reflect the population living in private households and covered by the FRS sample. This was achieved by deflating the usual resident population using data from the 2011 Censuses on the proportion of people usually resident, by local authority, age and sex who live in private households.

Table 1: HBAI grossing regime for Great Britain, FYE 2023

| Control totals for Great Britain | Groupings | Original Source | Adjustments made by DWP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Private household population by region, age and sex | Regions: North East, North West, Yorkshire and the Humber, East Midland, West Midlands, East, London, South East, South West, Wales, Scotland. Sex and age: Males 0-19 dependants, 16-24 independents, 25-29, 30-34, 40-44, 45-49, 50-59, 60-64, 65-74, 75-79, 80+; Females 0-19 dependants, 16-24 independents, 25-29, 30-34, 40-44, 45-49, 50-59, 60-69, 70-74, 75-79, 80+ | Mid-year population estimates, Office of National Statistics | ONS total population figures are adjusted for private household estimates using data supplied by ONS directly to DWP. 16-19-year-old dependents and non-dependents are split using data supplied by HMRC directly to DWP |

| Benefit Units with children | Region: England and Wales, Scotland | Families in receipt of child benefit, HM Revenue and Customs | |

| Lone Parents | Sex: Males, Females | Lone parent estimates, Labour Force Survey | Adjusted for FRS survey year (April-March) |

| Households by region | Region: North East, North West, Yorkshire and the Humber, East Midlands, West Midlands, East of England, London, South East, South West, Wales, Scotland. | Households by region, Office for National Statistics (England) / Welsh Government (Wales) / Scottish Government (Scotland) | Adjusted for FRS survey year (April-March) |

| Households by tenure type | Tenure (Social Renters, Private Renters, Owner Occupied) | Dwellings by tenure type, Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities | Household control totals are calculated using dwellings data published by DLUHC, Welsh Government, Scottish Government. Adjusted for FRS survey year (April-March) |

| Households by council tax band | Council Tax Band (NVS and A, B, C and D, E to I) | Dwellings by council tax band, Valuations Office Agency, Dwellings by council tax band, Scottish Government | Household control totals are calculated using dwellings data published by VOA / Scottish Government, adjusted for FRS survey year (April-March). Estimates for properties not-valued-separately (NVS) based on FRS sample proportions |

| Households containing ‘Very Rich’ people | Pensioners, Non-pensioners | HMRC Survey of Personal Incomes (SPI) |

Table 2: HBAI grossing regime for Northern Ireland, FYE 2023

| Control totals for Northern Ireland | Groupings | Original Source | Adjustments made by DWP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Private household population by age and sex | Sex and age: Males 0-19 dependants, 16-24 independents, 25-29, 30-34, 40-44, 45-49, 50-59, 60-64, 65-74, 75-79, 80+; Females 0-19 dependants, 16-24 independents, 25-29, 30-34, 40-44, 45-49, 50-59, 60-69, 70-74, 75-79, 80+ | Private household estimates, Department for Social Development in Northern Ireland | |

| Households | Household estimates, Department for Social Development in Northern Ireland | ||

| Lone Parents | Household estimates, Department for Social Development in Northern Ireland | ||

| Households containing ‘Very Rich’ people | Pensioners, Non-pensioners | HMRC Survey of Personal Incomes (SPI) |

Adjustment for individuals with very high incomes

An adjustment is made to sample cases at the top of the income distribution to correct for volatility in the highest incomes captured in the survey. This adjustment uses data kindly supplied by HM Revenue and Customs’ statisticians from HM Revenue and Customs’ Survey of Personal Incomes (SPI) to control the numbers and income levels of the ‘very rich’ while retaining the FRS data on the characteristics of their households. The methodology defines a household as ‘very rich’ if it contains a ‘very rich’ individual and it adjusts pensioners and non-pensioners separately. Thresholds have been set at the level above which, for each group, the FRS data is volatile due to small numbers of cases.

From the FYE 2010 publication, the SPI adjustment methodology was changed to be based on adjusting a fixed fraction of the population rather than on adjusting the incomes of all those individuals with incomes above a fixed cash terms level. This is intended to prevent an increasing fraction of the dataset being adjusted. The adjustment fraction was set at the same level as the fraction adjusted in FYE 2009. There was also a movement to basing all SPI adjustment decisions on gross rather than a mixture of gross and net incomes. These changes only have a very small effect on the results as presented.

The numbers of ‘very rich’ pensioners and non-pensioners in survey estimates are matched to SPI estimates by the introduction of two extra control totals into the grossing regime. One is for the total number of pensioners above the pensioner threshold and the other for the number of non-pensioners above the non-pensioner threshold. The grossing factors for individual cases are only marginally changed because of this adjustment. In addition, each ‘very rich’ individual in the FRS is assigned an income level derived from the SPI, as the latter gives a more accurate indication of the level of high incomes than the FRS. Again, this adjustment is carried out separately for pensioners and non-pensioners.

The latest SPI data available when we carried out our analysis was the FYE 2020, which was projected forward to cover the FYE 2023. This was due to the FYE 2021 SPI outturn data being significantly impacted by coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, and therefore HMRC continued to project using the previous year’s SPI. For FYE 2023, pensioners in Great Britain are subject to the SPI adjustment if their gross income exceeded £99,500 per year (£79,400 in Northern Ireland). Working-age adults (including the working-age partners of pensioners) are subject to the SPI adjustment if their gross income exceeded £351,500 per year (£181,000 per year in Northern Ireland).

Changes to the grossing regimes in FYE 2021 and FYE 2022

Due to the impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, there was a need to add in extra grossing controls for:

-

Month of interview (FYE 2021): the number of households sampled varied between months. There was no need to make changes to the back-series - adding month of interview in previous years has minimal impact as each month had approximately the same number of sample cases and there was less in-year variation in incomes.

-

Working-age adults with degrees (FYE 2021 and FYE 2022): there was a clear bias in the samples toward better-educated adults, specifically those with degrees. This bias was confirmed when comparing to an external data source – the Annual Population Survey (APS). It was important to address this as households with at least one working-age adult with a degree have statistically significantly higher incomes than households with adults that have lower levels of education. After adding in a control total for working-age adults with degree level education, there was still a bias towards younger adults with degrees so the grossing control was split into two: working-age adults aged 16 to 45 with a degree and working-aged adults over 45 with a degree. The grossing control totals were based on education level splits reported in the FRS prior to the pandemic, projected forward using growth in the APS.

-

Biannual grossing control for number of households (FYE 2022): this was introduced to balance the number of households in Great Britain across the two halves of the survey year. This was necessary due to the introduction of the pre-planned boost to the FRS issued sample in England and Wales in October 2021. In Northern Ireland, changes to the approach of contacting respondents in July 2021 meant that the achieved sample increased markedly partway through the year. This is not normally a feature of the FRS achieved sample, with response normally spread relatively equally over each twelve-month run of fieldwork. We introduced a quarterly household grossing control to balance their sample across the year.

Following the resumption of face-to-face interviewing in the FRS in FYE 2023, the methodology reverted to the grossing system in place before the pandemic (detailed in tables 1 and 2).

Plans to use 2021 Census outputs for grossing

We expect to receive UK population and private household estimates based on the 2021 Census (2022 for Scotland) later in 2024. This will include a back series of grossing factors from FYE 2013 to re-base the HBAI estimates from that year onwards.

As with previous rebasing exercises, we will also review other inputs into the grossing including the SPI adjustment received from HMRC. We will provide transparency to users on the main areas of change when the statistical series is reissued.

Equivalisation

HBAI uses net disposable weekly household income, after adjusting for the household size and composition, as an assessment for material living standards - the level of consumption of goods and services that people could attain given the net income of the household in which they live. To allow comparisons of the living standards of different types of households, income is adjusted to take into account variations in the size and composition of the households in a process known as equivalisation. HBAI assumes that all individuals in the household benefit equally from the combined income of the household. Thus, all members of any one household will appear at the same point in the income distribution.

The unit of analysis is the individual, so the populations and percentages in the tables are numbers and percentages of individuals – both adults and children.

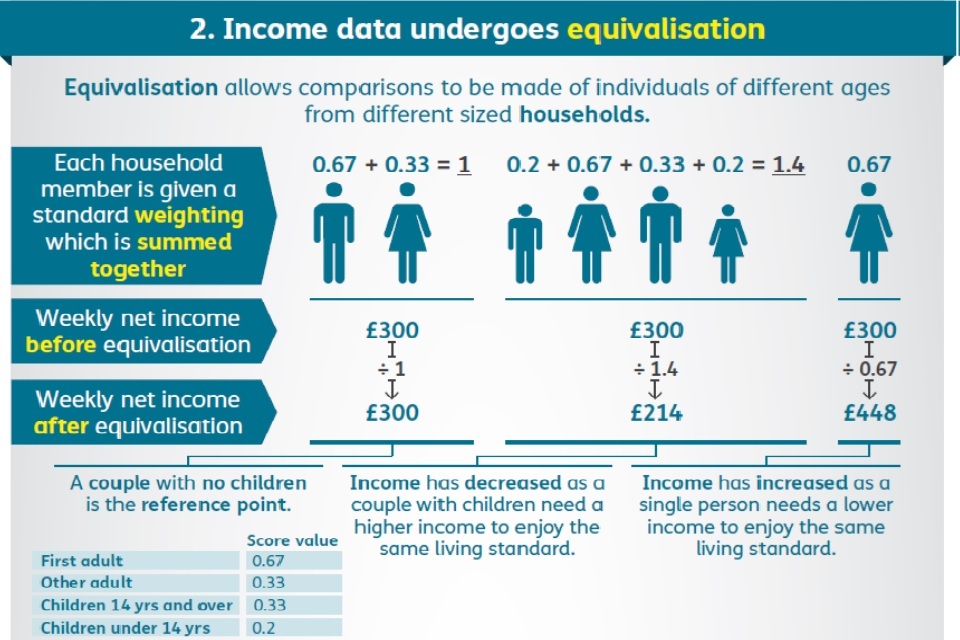

Equivalence scales conventionally take an adult couple without children as the reference point, with an equivalence value of one. The process then increases relatively the income of single person households (since their incomes are divided by a value of less than one) and reduces relatively the incomes of households with three or more persons, which have an equivalence value of greater than one. The infographic below illustrates the process of equivalisation, Before Housing Costs.

Figure 1

Consider a single person, a couple with no children, and a couple with two children aged twelve and ten, all having unadjusted weekly household incomes of £300 (BHC). The process of equivalisation, as conducted in HBAI, gives an equivalised income of £448 to the single person, £300 to the couple with no children, but only £214 to the couple with children.

The main equivalence scales now used in HBAI are the modified OECD scales, which take the values shown in Table 3. The equivalent values used by the McClements equivalence scales are also shown for comparison alongside modified OECD values. The McClements scales were used by HBAI to adjust income up to the FYE 2005 publication.

In the modified OECD and McClements versions, two separate scales are used, one for income BHC and one for income AHC. The construction of household equivalence values from these scales is quite straightforward. For example, the BHC equivalence value for a household containing a couple with a fourteen-year-old and a ten-year-old child together with one other adult would be 1.86 from the sum of the scale values:

0.67 + 0.33 + 0.33 + 0.33 + 0.20 = 1.86

This is made up of 0.67 for the first adult, 0.33 for their spouse, the other adult and the fourteen-year-old child and 0.20 for the ten-year-old child. The total income for the household would then be divided by 1.86 in order to arrive at the measure of equivalised household income used in HBAI analysis.

Table 3: Comparison of modified OECD and McClements equivalence scales

| OECD rescaled to couple without Children=1 | OECD ‘Companion’ Scale to equivalise AHC results | McClements BHC | McClements AHC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Adult | 0.67 | 0.58 | 0.61 | 0.55 |

| Spouse | 0.33 | 0.42 | 0.39 | 0.45 |

| Other Second Adult | 0.33 | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.45 |

| Third Adult | 0.33 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.45 |

| Subsequent Adults | 0.33 | 0.42 | 0.36 | 0.40 |

| Children aged under 14 years | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| Children aged 14 years and over | 0.33 | 0.42 | 0.32 | 0.34 |

Notes:

-

All scales are presented to 2 decimal places.

-

For the McClements scale, the weight for ‘Other second adult’ is used in place of the weight for ‘Spouse’ when 2 adults living in a household are sharing accommodation, but are not living as a couple. ‘Third adult and ‘Subsequent adult’ weights are used for the remaining adults in the household as appropriate. In contrast to the McClements scales, apart from for the first adult, the OECD scales do not differentiate for subsequent adults.

-

The McClements scale varies by age for children, appropriate averages are shown in the table.

Income Definition

The income measure used in HBAI is weekly net (disposable) equivalised household income. This comprises total income from all sources of all household members including dependants.

Income is adjusted for household size and composition by means of equivalence scales, which reflect the extent to which households of different size and composition require a different level of income to achieve the same standard of living. This adjusted income is referred to as equivalised income.

In detail, income includes:

-

usual net earnings from employment;

-

profit or loss from self-employment (losses are treated as a negative income);

-

income received from dividends (from FYE 2022);

-

state support - all benefits and tax credits;

-

income from occupational and private pensions;

-

investment income;

-

maintenance payments;

-

income from educational grants and scholarships (including, for students, student loans and parental contributions); and

-

the cash value of certain forms of income in kind (free school meals, free school breakfast, free school milk, free school fruit and vegetables, Healthy Start vouchers and free TV licences for those aged 75 and over who receive Pension Credit.

Income is net of the following items:

-

income tax payments;

-

National Insurance contributions;

-

domestic rates/council tax;

-

contributions to occupational pension schemes (including all additional voluntary contributions (AVCs) to occupational pension schemes, and any contributions to stakeholder and personal pensions);

-

all maintenance and child support payments, which are deducted from the income of the person making the payment;

-

parental contributions to students living away from home; and

-

student loan repayments.

Income After Housing Costs (AHC) is derived by deducting a measure of housing costs from the above income measure.

Housing costs

These include the following:

-

rent (gross of housing benefit);

-

water rates, community water charges and council water charges;

-

mortgage interest payments;

-

structural insurance premiums (for owner occupiers); and

-

ground rent and service charges.

For Northern Ireland households, water provision is funded from taxation and there are no direct water charges. Therefore, it is already taken into account in the Before Housing Costs measure.

In the FYE 1996 and subsequent datasets, a refinement was made to the calculation of mortgage interest payments to disregard additional loans which had been taken out for purposes other than house purchase.

Negative incomes

Negative incomes BHC are reset to zero, but negative AHC incomes calculated from the adjusted BHC incomes are possible. Where incomes have been adjusted to zero BHC, income AHC is derived from the adjusted BHC income.

State support

The Government pays money to individuals in order to support them financially under various circumstances. Most of these benefits are administered by DWP. The exceptions are Housing Benefit and Council Tax Reduction, which are administered by local authorities. Tax Credits are not treated as benefits, but both Tax Credits and benefits are included in the term State Support. Further information on UK state support and specific benefits for devolved administrations is available under ‘Benefits’ in the Glossary section of the FRS Background Information and Methodology.

Treatment of coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic related support schemes in the HBAI income estimates for FYE 2021 and FYE 2022

Earnings from employment

During FYE 2021 and FYE 2022 many households experienced variation in their earnings within the survey year due to changes in employment and hours worked and/or receipt of support grants through schemes such as the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS) or the Self-Employment Income Support Scheme (SEISS). From May 2020, the FRS questionnaire incorporated questions to specifically ask about receipt of CJRS and from June 2020, this was extended to SEISS. The CJRS and SEISS schemes were closed in September 2021 and questions about income from the schemes were removed from the FRS questionnaire in January 2022.

For employees, receipt of CJRS (‘furlough’) and any resulting effect on levels of pay were fully reflected in the HBAI estimates. Employees who were furloughed were classified as employed, but temporarily away from work. This meant that, all things being equal, furloughed workers did not reduce the number of people in employment (or the employment rate). The calculation of ‘income from employment’ used wages which were treated as income rather than state support, irrespective of any support payments from CJRS that the respondent’s employer was receiving in respect of their employment.

Earnings from self-employment

For the self-employed, it is difficult to calculate current-year income, and in line with international standards, the FRS questionnaire asks for profit data for a previous tax year and/or regular self-employment income over the past twelve months. While this is less of an issue when incomes are broadly stable, it became more of a challenge in FYE 2021 given the sharp changes in self-employed incomes over the course of the pandemic. Although from June 2020 the FRS specifically asked about receipt of SEISS grants and amounts, questions were not asked about receipt of income from continued trading which was permissible under the terms of the scheme. It was therefore not possible to adapt our methodology to estimate in-year income more accurately, taking account of both SEISS and non-SEISS sources.

This means that the HBAI estimates indirectly, rather than explicitly, included information on the amount of SEISS received. This is because we pull through information on previous trading profits, upon which the SEISS grants are based. In FYE 2021, while there was an option to ‘add in’ the SEISS amounts received for this group, there was a risk of double counting, as there was evidence that some respondents had already included income from SEISS in their responses. In FYE 2022, receipt of the first three SEISS grants was treated as taxable income when calculating profits in FYE 2021 tax returns. Therefore, money received from the scheme will have been automatically included in income estimates for self-employed people who reported their FYE 2021 profit data.

Sensitivity analysis completed internally showed that, as in other years, changes to self-employed incomes had only a marginal effect on the overall estimated proportions of the population in low income.

Further information is available in the FRS Background Information and Methodology.

Treatment of cost of living and wider support schemes in the HBAI income estimates for FYE 2023

During FYE 2023 the UK Government announced and implemented additional support to families with several cost of living support schemes, depending on peoples’ circumstances.

These were:

-

A Cost of Living Payment for households on a qualifying low-income benefit or tax credits. A payment of £650 was paid in 2 lump sums of £326 and £324 to households already in receipt of the eligible benefits. This payment was made on top of any benefit payments received by the claimants.

-

A Disability Cost of Living Payment for households on a qualifying disability benefit. A lump sum payment of £150 was paid to those already in receipt of the eligible benefits. To be eligible for the payment, households must have received a payment (or later receive a payment) of one of these qualifying benefits before 25 May 2022.

-

A Pensioner Cost of Living Payment for households entitled to a Winter Fuel Payment for winter 2022 to 2023. Up to £300 was paid with eligible households’ normal payments from November 2022. This is in addition to any other Cost of Living Payment received.

-

An Energy Bills Support Scheme grant of £400 to help with rising energy costs. The payment was received by customers between October 2022 and March 2023 either as a monthly credit on bills, applied directly to the meter or paid as a voucher. Households in Northern Ireland were not eligible for this scheme, but equivalent support of £600 per household was provided.

-

Households in receipt of the Guarantee Credit element of Pension Credit or were on a low income and have high energy costs also received a one-off discount on their energy bill under the Warm Home Discount scheme. The rebate increased from £140 to £150 and was discounted automatically from bills. A further £200 was available in Wales for those in receipt of qualifying benefits (through the Wales Fuel Support Scheme).

-

A £150 non-repayable rebate for households in England in council tax bands A to D, known as the Council Tax Rebate. This was in response to the rising cost of household bills in 2022 to 2023.

Income from these sources is primarily categorised as state support in the FYE 2023 estimates, except for the £400 Energy Support Scheme payments (£600 in Northern Ireland), the £150 Council Tax Rebate payments which were made to households in bands A to D, and the Warm Home Discount and Wales Fuel Support Scheme. These are classified as miscellaneous income.

Most of the schemes were introduced at pace, in a timeframe which made it difficult to adapt the FRS questionnaire to capture them. As each support scheme came with clear eligibility guidelines, receipt of the payments was imputed based on respondent characteristics. Further details on the methodology used to impute receipt are in the FRS Background Information and Methodology document.

Interpreting low-income measures

Relative low income sets the threshold as a proportion of the average income and moves each year as average income moves. It is used to measure the number and proportion of individuals who have incomes a certain proportion below the average.

The percentage of individuals in relative low income will increase if:

-

the average income stays the same, or rises, and individuals with the lowest incomes see their income fall, or rise less, than average income; or

-

the average income falls and individuals with the lowest incomes see their income fall more than the average income.

The percentage of individuals in relative low income will decrease if:

-

the average income stays the same, or rises, and individuals with the lowest incomes see their income rise more than average income; or

-

the average income falls and individuals with the lowest incomes see their income rise, or fall less, than average income, or see no change in their income.

Absolute low income sets the low income line in a given year, then adjusts it each year with inflation as measured by variants of the CPI. This measures the proportion of individuals who are below a certain standard of living in the UK (as measured by income).

-

The percentage of individuals in absolute low income will increase if individuals with the lowest incomes see their income fall or rise less than inflation.

-

The percentage of individuals in absolute low income will decrease if individuals with the lowest incomes see their incomes rise more than inflation.

Income inequality, measured by the Gini Coefficient, shows how incomes are distributed across all individuals, and provides an indicator of how high and low-income individuals compare to one another. It ranges from zero (when everybody has identical incomes) to 100 per cent (when all income goes to only 1 person). The 90:10 ratio is the average (median) income of the top 20 per cent (quintile 5) divided by the average income of the bottom 20 per cent (quintile 1). The higher the number, the greater the gap between those with the highest incomes and those with the lowest incomes.

Figure 2

Before Housing Costs (BHC) measures allow an assessment of the relative standard of living of those individuals who were actually benefiting from a better quality of housing by paying more for better accommodation, and income growth over time incorporates improvements in living standards where higher costs reflected improvements in the quality of housing.

After Housing Costs (AHC) measures allow an assessment of living standards of individuals whose housing costs are high relative to the quality of their accommodation. Income growth over time may also overstate improvements in living standards for low-income groups, as a rise in Housing Benefit to offset higher rents (for a given quality of accommodation) would be counted as an income rise.

Therefore, HBAI presents analyses of disposable income on both a BHC and AHC basis. This is principally to take into account variations in housing costs that themselves do not correspond to comparable variations in the quality of housing.

Combined low income and child material deprivation

Material deprivation is an additional way of measuring living standards and refers to the self-reported inability of individuals or households to afford goods and activities that are typical in society at a given point in time, irrespective of whether they would choose to have these items, even if they could afford them.

A suite of questions designed to capture the material deprivation experienced by families with children has been included in the FRS since FYE 2005. Respondents are asked whether they have 21 goods and services, including child, adult and household items. Together, these questions form the best discriminator between those families that are deprived and those that are not. If they do not have a good or service, they are asked whether this is because they do not want them or because they cannot afford them.

The original list of items was identified by independent academic analysis. See McKay, S. and Collard, S. (2004). Developing deprivation questions for the Family Resources Survey, Department for Work and Pensions Working Paper Number 13. The questions are kept under review and for the FYE 2011 Family Resources Survey, information on four additional material deprivation goods and services was collected and from FYE 2012 four questions from the original suite were removed.

The trends table 4.5tr available in the Data Tables on the HBAI homepage shows figures using the original suite of questions up to and including FYE 2011, and the new suite of questions from FYE 2011 onwards. FYE 2011 data is presented on both bases as figures from the old and new suite of questions are not comparable.

See Appendix 3 of the FYE 2011 HBAI publication for a discussion of the implications of changing the items.

A prevalence weighted approach has been used, in combination with a relative low-income or severe relative low-income threshold. Prevalence weighting is a technique of scoring deprivation in which more weight in the deprivation measure is given to families lacking those items that most families already have. This means a greater importance, when an item is lacked, is assigned to those items that are more commonly owned in the population.

For each question a score of 1 indicates where an item is lacked because it cannot be afforded. If the family has the item, the item is not needed or wanted, or the question does not apply then a score of 0 is given. This score is multiplied by the relevant prevalence weight. The scores on each item are summed and then divided by the total maximum score; this results in a continuous distribution of scores ranging from 0 to 1. The scores are multiplied by 100 to make them easier to interpret. The final scores, therefore, range from 0 to 100, with any families lacking all items which other families had access to scoring 100.

A child is in combined low income and child material deprivation if they live in a family that has a final material deprivation score of 25 or more and an equivalised household income below 50/60/70 per cent of relative/absolute median income.

From the FYE 2009 edition of the HBAI publication, we moved to using the prevalence weights relative to the survey year in question, rather than fixed FYE 2005 weights, which were used in previous publications. The prevalence weights are shown in Table 4 below.

Table 4: Material deprivation scores used for children in FYE 2023

| Material deprivation questions | Weights | Final Scores |

|---|---|---|

| For children | ||

| Outdoor space or facilities nearby to play safely | 0.941 | 5.80 |

| Enough bedrooms for every child of 10 or over of a different sex to have their own bedroom | 0.824 | 5.08 |

| Celebrations on special occasions such as birthdays, Christmas or other religious festivals | 0.951 | 5.86 |

| Leisure equipment such as sports equipment or a bicycle | 0.859 | 5.29 |

| A family holiday away from home for at least 1 week a year | 0.651 | 4.01 |

| A hobby or leisure activity | 0.752 | 4.64 |

| Friends around for tea or a snack once a fortnight | 0.635 | 3.91 |

| Go on school trips | 0.855 | 5.27 |

| Toddler group/nursery/playgroup at least once a week | 0.698 | 4.31 |

| Attends organised activity outside school each week | 0.700 | 4.31 |

| Fresh fruit and vegetables eaten by children every day | 0.915 | 5.64 |

| Warm winter coat for each child | 0.980 | 6.04 |

| For adults | ||

| Enough money to keep home in a decent state of decoration | 0.779 | 4.80 |

| A holiday away from home for at least 1 week a year, whilst not staying with relatives at their home | 0.578 | 3.56 |

| Household contents insurance | 0.653 | 4.02 |

| Regular savings of £10 a month or more for rainy days or retirement | 0.655 | 4.03 |