Get Britain Working White Paper

Updated 2 September 2025

Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions, Chancellor of the Exchequer, and Secretary of State for Education by Command of His Majesty.

November 2024

CP 1191

© Crown copyright 2024

This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk.

Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned.

This publication is available at www.gov.uk/official-documents.

Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at wp.gbw@dwp.gov.uk.

ISBN 978-1-5286-5157-8

EE03184199 11/24

Joint Ministerial Foreword

To get Britain growing again, we’ve got to get Britain working again.

Our country’s greatest asset is its people. However, the talents of too many are being wasted because of spiralling economic inactivity. We’ve got 2.8 million people locked out of work due to long-term sickness.[footnote 1] 1 in 8 of our young people are not in education, employment or training.[footnote 2] 9 million adults lack the basic skills they need to get on.[footnote 3]

Behind these statistics are human stories played out time and again across the country. Young people with mental health problems, waiting for treatment, or lacking the basic qualifications they need to get a job and kick-start their career. People in their 50s and 60s struggling with chronic pain like bad joints, with women often caring for elderly relatives, who have huge experience to offer employers but far too few opportunities. The school-leaver let down because employment support is not designed to help them seize today’s opportunities.

This is not good enough for people across the country who cannot access the support they need to improve their living standards and build a better life. It is bad for employers who are desperate to recruit but cannot find people with the skills to fill well-paying roles. It is bad for the economy and the taxpayer, driving a rising benefits bill.

Nothing less than radical reform is required. This White Paper sets out a fundamentally different approach, alongside the detail of our plan for £240 million of investment. Rather than writing people off, our reforms target and tackle the root causes behind why people are not working, joining up help and support, based on the needs of local people and local places.

This means fixing the NHS, cutting waiting lists so people can get back to health and back to work, as well as having a greater focus on preventing people becoming ill in the first place.

It means transforming a department for welfare into a genuine department for work through a new national jobs and careers service, focused on people’s skills and careers not only monitoring and managing benefit claims.

It means mobilising Mayors and councils to join up local work, health and skills support in ways that meet the needs of their area.

It means building a Youth Guarantee, so every young person has a real chance of either earning or learning.

With our series of trailblazers around the country, we will begin to set the blueprint for this new approach to reducing economic inactivity.

It also means supporting employers to employ people with health conditions, and to keep them in the workplace, as well as having a health and disability benefits system that encourages people to engage with support and try work.

This White Paper is part of wider government action to spread opportunity and fix the foundations of our economy. This includes launching Skills England to create a shared national plan to boost the nation’s skills, creating more good jobs through our modern Industrial Strategy, and strengthening employment rights through our Plan to Make Work Pay.

Our plan to Get Britain Working sets us on a path to bring down economic inactivity levels and takes the first steps to delivering our long-term ambition to achieve an 80% employment rate.

This is not only a mission for the whole government. It also needs genuine partnership with and between, the new jobs and careers service, Mayors and councils, trade unions, private, voluntary, community and social enterprise organisations, the NHS, employers and schools, colleges and universities. This is how, together, we can build a healthier, wealthier nation - driving up employment and opportunity, skills and productivity – while driving down the benefit bill.

Above all, this is about how we ensure everyone, regardless of their background, age, ethnicity, or where they live, has the opportunities they need to achieve and thrive, to succeed and flourish.

Helping people into decent, well-paid jobs and giving our children and young people the best opportunities to get on in life. This is how we get Britain working and growing again.

The Rt Hon Rachel Reeves MP, Chancellor of the Exchequer

The Rt Hon Liz Kendall MP, Secretary of State for Work and Pensions

The Rt Hon Bridget Phillipson MP, Secretary of State for Education

The Rt Hon Wes Streeting MP, Secretary of State for Health and Social Care

Executive Summary

1. A key part of this government’s mission to kick-start growth is our commitment to building an inclusive and thriving labour market where everyone has the opportunity of good work, and the chance to get on at work. This will improve living standards and ensure we can fund vital public services. It is also central to delivering on our missions to break down barriers to opportunity, and to improve the health of the nation.

2. That is why the government has set a long-term ambition to achieve an 80% employment rate. This would place the UK among the highest performing countries in the world, with the equivalent of over 2 million more people in work.[footnote 4] Our approach is based on 3 pillars:

-

a modern Industrial Strategy and Local Growth Plans – to create more good jobs in every part of the country

-

improving the quality and security of work through the Plan to Make Work Pay

-

the biggest reforms to employment support for a generation, bringing together skills and health to get more people into work and to get on in work

3. This third pillar is the focus for this White Paper: to Get Britain Working, as part of a system based on mutual obligations, where those who can work, do work, and where support is matched by the requirement for jobseekers to take it up.

The case for change

4. The UK is the only major economy that has seen its employment rate fall over the last 5 years, reversing the previous long-run trend of declining rates of economic inactivity. This has been driven predominantly by a rise in the number of people out of work due to long-term ill health.

5. This White Paper sets out fundamental reforms to tackle 6 key issues:

-

too many people are excluded from the labour market – especially those with health conditions, caring responsibilities or lower skill levels

-

too many young people leave school without essential skills or access to high-quality further learning, an apprenticeship or support to work so that they can thrive at the start of their career

-

too many people are stuck in insecure, poor quality and often low-paying work, which contributes to a weaker economy and also affects their health and wellbeing

-

too many women who care for their families still experience challenges staying in and progressing in work

-

too many employers cannot fill their vacancies due to labour and skills shortages, holding back economic growth and undermining living standards

-

there is too great a disparity in labour market outcomes between different places and for different groups of people

6. The UK has lived with many of these challenges for decades, but the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic alongside long-running economic, demographic and technological changes mean that we need radical action now to address them.

7. The current employment support system is set up to deal with the problems of the past, not the challenges of today or the opportunities of the future. It is:

-

too narrowly focused on unemployment, with too little support in particular for disabled people and people who have health conditions, and young people who are too often written off before their careers have even begun

-

too centralised and siloed, both across central government and in the relationships between national and local government

-

too focused on benefits and compliance, which can push people away from support at the expense of real help that meets their needs

Our new approach

8. The driving purpose behind our new approach is to enable everyone to have the opportunity of secure, rewarding and fulfilling work. That means tackling economic inactivity, particularly where it is driven by ill health. It means getting more young people the chances and choices to learn, earn and take the first steps in work and their career. It means helping more people to get good jobs and progress out of poverty. And it means enabling local areas – especially through mayoral authorities – to lead and drive action to reduce economic inactivity and expand opportunity for young people, working with the NHS, councils, colleges, the voluntary sector and employers.

9. To deliver this, our fundamental reforms will transform the system so that there is better:

-

support for people to get back into work if they are outside the workforce (and help to stay in employment if they have a health condition)

-

access to training, an apprenticeship, or help to find work for young people (including help to avoid losing touch with the workforce at a young age)

-

help for people to get a job, upskill, and get on in their career, whether they are unemployed or in employment, alongside clear obligations on people to take up support and do in return everything they can to work

-

support for employers to recruit, retain and develop staff

Plan for reform

10. This White Paper sets out our proposals for action and change in a range of areas

Scaling up and deepening the contribution of the NHS and wider health system to improve employment outcomes

Given the strong evidence on the health benefits of good work, we will:

-

support the NHS to provide 40,000 extra elective appointments each week and deploy dedicated capacity to reduce waiting lists in 20 NHS Trusts in England with the highest levels of health-related economic inactivity

-

address key public health issues that contribute to worklessness, through an expansion of Talking Therapies, our landmark Tobacco and Vapes Bill and a range of steps to tackle obesity (including trials of new treatments)

-

expand access to expert employment advisers as part of treatment and care pathways, in particular mental health and musculoskeletal services. We will also continue to expand access to Individual Placement and Support (IPS) for severe mental illness, reaching 140,000 more people by 2028/29

Backing local areas to shape an effective work, health and skills offer for local people, with mayoral authorities leading the way in England

Going with the grain of the government’s wider approach to devolution, we will:

-

work with mayoral authorities and the Welsh Government to mobilise 8 place-based trailblazers to reduce economic inactivity, with £125 million of funding in 2025/26.[footnote 5]This will enable them to work with the full range of partners in their areas to shape a strong, joined-up and local work, health and skills offer. Trailblazers will trial new interventions and increase engagement with local people who are outside the workforce. In 3 areas in England, trailblazers will receive a share of £45 million for dedicated input from the local NHS Integrated Care System (ICS). They will all have a set of agreed outcomes, shared governance and a commitment to robust evaluation and learning

-

support all areas in England to develop local Get Britain Working Plans and to convene local partners to work together to deliver these. Plans will focus on reducing economic inactivity and taking forward the Youth Guarantee within local areas. We expect these plans to be developed by mayoral authorities where they exist – aligned with their Local Growth Plans – and elsewhere by groups of local authorities

-

kick-start local plans with £115 million in funding next year to enable local areas in England and Wales to deliver new back-to-work support for people who are economically inactive. Connect to Work, a new supported employment programme, will support up to 100,000 people a year at full rollout, as the first tranche of money from a new Get Britain Working Fund. This approach will enable local areas to develop this new provision as part of a coherent local offer, alongside wider health and skills support, the use of the UK Shared Prosperity Fund and active links with local employers

-

incorporate devolved funding for Connect to Work into the new Integrated Settlements for Mayoral Combined Authorities from 2025/26, which will initially be available to Greater Manchester and the West Midlands

Delivering a Youth Guarantee so that all 18 to 21-year-olds in England have access to education, training or help to find a job or an apprenticeship

Building on existing provision and entitlements, we will:

-

work with mayoral authorities to mobilise 8 place-based Youth Guarantee trailblazers with £45 million of funding in 2025/26. These trailblazers will design and test how different elements of the Guarantee can be brought together into a coherent offer for young people, with clear leadership and accountability and proactive engagement to make sure no young person misses out. All trailblazers will have a set of agreed outcomes, shared governance and a commitment to robust evaluation and learning

-

expand opportunities for young people by transforming the Apprenticeship Levy into a more flexible Growth and Skills Levy. As a first step, we will create new foundation and shorter apprenticeship opportunities for young people in key sectors

-

establish a new national partnership to generate a range of exciting opportunities that engage young people and set them on the path to success, beginning with leading sports, arts and cultural organisations like The Premier League, Channel 4 and the Royal Shakespeare Company

-

explore a new approach to benefit rules for young people, to make sure they can develop skills alongside searching for work, while also preventing young people from falling out of the workforce before their careers have begun

-

act to prevent young people losing touch with education or employment before the age of 18, with a guaranteed place in education and training for all 16 and 17-year-olds, an expansion of work experience and careers advice, action to tackle school attendance, and steps to improve access to mental health services for young people

Creating a new jobs and careers service to help people get into work and get on at work

To promote employment, tackle economic inactivity and boost living standards, we will transform Jobcentre Plus across Great Britain into a genuine public employment service, bringing it together with the National Careers Service in England. This service will:

-

be digital, universal and fully inclusive

-

be based around personalised support to help people get into work, build skills and get on in their career, underpinned by a clear expectation that jobseekers do all they can to look for work

-

build new and enhanced relationships with employers that better meet their recruitment needs and help to reduce reliance on foreign workers

-

have a clear focus on supporting progression and good work by bringing together employment support and careers advice

-

be locally responsive, embedded and engaged, as a strong local partner with other local services and local organisations

The new jobs and careers service will be focused around 3 core objectives of improving engagement, employment and earnings. The recent Budget allocated £55 million in 2025/26 to kick-start these ambitious reforms. This will enable investment in new digital prototypes and tests and trials of elements of the new service, including an enhanced employer offer. To build a national service that is fundamentally local at heart, we will design, develop and test this service in partnership with mayoral authorities, local authorities and devolved governments.

Launching an independent review into the role of UK employers in promoting healthy and inclusive workplaces

Poor workforce health imposes large costs on employers, especially from sickness absence and turnover, while also making it harder for them to find the talent they need to grow and thrive. There is also compelling evidence about the value of helping people with a health condition or disability to stay in work, including to prevent them becoming economically inactive. In response, the review will consider what more can be done to enable employers to:

-

increase the recruitment and retention of disabled people and those with a health condition, including via the new jobs and careers service

-

prevent people becoming unwell at work and promote good, healthy workplaces

-

undertake early intervention for sickness absence and increase returns to work

The review will run until next summer and involve wide-ranging engagement with employers, employees, trade unions, health experts, and disabled people and those with health conditions. It will complement the government’s Make Work Pay reforms, which will tackle job insecurity and expand flexible working.

11. To support these goals, the government believes there is also a strong case to change the system of health and disability benefits across Great Britain so that it better enables people to enter and remain in work, and to respond to the complex and fluctuating nature of the health conditions many people live with today. The government will bring forward a Green Paper in spring 2025. We will listen to and engage with disabled people as we develop proposals for reform in this area and across the employment support system.

12. In delivering this new approach, we are building on existing strengths: thousands of dedicated frontline employment and careers advisers (including in Jobcentre Plus and the National Careers Service); a network of capable providers and voluntary organisations; local leaders – in devolved governments and councils, combined authorities, colleges, universities and the NHS – committed to making a difference; and businesses, employers and trade unions across the country who are passionate about playing a positive role in their communities.

13. The changes set out in this White Paper require government to work in a very different way. Consistent with mission-driven government, that means being more joined up across central government, especially in relation to work, health and skills, and forging a new relationship between the UK, devolved and local governments, as well as with other partners like the NHS, colleges, employers, trade unions and civil society.

Chapter summaries

Chapter 1: sets out our ambition to drive growth through employment and to build a thriving and inclusive labour market that works for people, communities and the economy.

Chapter 2: diagnoses the problems we face in the labour market and sets out the case for fundamental reform of our health, employment and skills systems.

Chapter 3: focuses on interventions to prevent economic inactivity driven by ill health and sets out government action to increase workforce participation through improving the health of the population, mobilising local work, health, and the skills systems, supporting employers to promote healthy workforces, and reforming the health and disability benefits system. It also sets out plans for a series of major place-based trailblazers to design and test local action to tackle economic inactivity.

Chapter 4: focuses on getting young people the jobs and opportunities they deserve, the challenges faced by young people first entering the world of work, how the government is delivering the Youth Guarantee in England, including through new local trailblazers, and plans to launch a Youth Guarantee Advisory Panel and national partnerships with leading organisations to help young people develop skills and find employment.

Chapter 5: focuses on how the government will deliver a new jobs and careers service to support people to progress in their careers, earn more and find higher quality work, the 5 pillars that will underpin design and delivery of this new service and our plan for adult skills.

Chapter 6: sets out wider labour market reforms that support the government’s policy agenda to deliver economic growth and break down barriers to opportunity.

Chapter 7: sets out the territorial scope of these reforms, our plans for greater devolution in Wales and England and our conclusions and next steps.

Chapter 1: Driving growth through employment

14. Building a thriving and inclusive labour market and increasing the number of people in work is central to achieving the government’s number one mission to grow the economy, as well as delivering our missions to spread opportunity and improve the health of the nation.

15. We want to build a labour market in which everyone has the opportunity to participate and progress regardless of their background, age, ethnicity, or where they live – because work is good for people, for communities and for the economy.

16. For individuals, having a job helps provide a sense of purpose, value and control. It provides financial resilience, enabling families to improve their living standards and escape poverty. The benefits also go beyond a pay cheque: research shows that good employment is good for physical and mental health and promotes full participation in society and independence.[footnote 6]

17. For communities, more people in work means more money spent in local shops, hospitality and entertainment, boosting local prospects and reducing regional disparities. Through the government’s Growth Mission, we will ensure more people are supported to access and engage with dynamic markets across the UK, wherever they choose to live.

18. Skilled work is good for helping businesses to grow. Approximately one third of annual productivity growth from 2001 to 2019 was due to general skills improvement, but there are still significant gaps that are limiting growth in key sectors.[footnote 7] Increasing the amount of skilled work helps to increase productivity and innovation, which in turn encourages businesses to invest.[footnote 8]

19. Increasing employment is also good for our economy and public finances. More people in work means more funding for vital public services. Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) analysis recently suggested half a million more people participating in the labour market would lower borrowing by £18.7 billion by 2027/28.[footnote 9]

Therefore, to grow the economy and spread opportunity to every corner of the country, this Get Britain Working White Paper will support higher employment and lower economic inactivity, and will enable more people to develop their careers and boost their skills so that they can move into higher paid, higher quality and more productive work.[footnote 10] This will in turn help us to make progress towards our long-term ambition of an 80% employment rate for the UK (see Box 1).

Box 1: A bold, long-term ambition to reach an 80% employment rate

Increasing labour market participation will support the Growth Mission through expanding labour supply and boosting the productive capacity of the economy. Unemployment is low by historical standards at 4.1%, so reducing elevated levels of economic inactivity is critical to achieving an 80% employment rate.[footnote 11] This would bring the UK in line with top performing economies such as the Netherlands (82.5%), Switzerland (80.4%) and Iceland (85.3%).[footnote 12] This White Paper identifies 3 key groups for whom economic inactivity could be reduced: people who are economically inactive due to long-term sickness, young people who are not in education, employment or training, and women with caring responsibilities.

Office for National Statistics (ONS) measures of economic inactivity include people who are studying, which in time can lead to higher quality employment and higher wages. We will therefore ensure that setting ambitious goals to reduce economic inactivity does not set the wrong incentives around young people’s participation in learning, and that our efforts are fully focused on reducing the number of young people who are not in education, training or employment. The Labour Market Advisory Board (see Chapter 7) will support our work on the exact definition and measurement of our ambitions on employment and labour force participation.

21. This requires a full UK and devolved government, public sector, third sector, and business effort. Get Britain Working is part of a bold, new, mission-led approach, enabling a collective and relentless focus on the UK’s top priorities, to deliver a decade of national renewal.

Box 2: Mission-driven government

The UK government has set out 5 key missions: Growth, Clean Energy, Safer Streets, Opportunity and Health. Get Britain Working supports each mission:

Growth Mission – Increasing the number of people in good jobs is central to the government’s ambition to drive growth, an ambition which includes a range of actions being taken across government such as the modern Industrial Strategy. Sustained economic growth is in turn the only route to improving living standards and employment prospects across the UK.

Opportunity Mission – The UK should be a country where hard work means you can get on in life regardless of your background. The Opportunity Mission will break the link between young people’s backgrounds and their future success by delivering in 3 key areas: giving every child the best start in life; helping them achieve and thrive through school years and building skills for opportunity and growth.

Health Mission – Through the Health Mission and the NHS 10-year plan for England, which will be published next spring, we have a dual focus on fixing the foundations of the NHS and shifting to a system focused on prevention. Ill health has become a critical driver of economic inactivity, and through these steps we will improve the health of the population and support people to stay in and return to work.

Clean Energy Superpower – Becoming a world leader in climate action will create jobs and opportunities right across the country. 1 in 5 jobs will be directly influenced by the shift towards a net-zero carbon economy, with the Climate Change Committee estimating that between 135,000 and 725,000 new jobs could be created across low-carbon sectors by 2030, across the range of different skills levels.[footnote 13]

Safer Streets Mission – Halving violence against women and girls (VAWG) and knife crime within a decade, while simultaneously improving confidence in policing and the criminal justice system, will require improvements in local policing. To achieve this, the Safer Streets Mission is focusing on delivering thousands more neighbourhood policing roles to meet the government’s neighbourhood policing guarantee and to restore public confidence in policing. The knock-on societal benefits of this mission – for example, fewer young people falling into crime, less anti-social behaviour and fewer victims of crime – will also benefit the Opportunity, Health and Growth Missions, which will in turn support the labour market.

Chapter 2: Problem diagnosis and the case for change

22. Although the number of people in the UK on payrolls is at a near record high, this masks significant inequalities and challenges.[footnote 14]

23. Too many people are excluded from the labour market – especially due to ill health and disability. The UK remains the only G7 country that has higher levels of economic inactivity (see Box 3) now than before the pandemic,[footnote 15] with a record level of 2.8 million people out of work due to long-term sickness.[footnote 16] As Box 4 sets out, a lower percentage of people are working than before, with an economic inactivity rate of 21.8% in Q2 2024.[footnote 17] This is bad for individuals and their living standards, bad for communities, bad for employers who lose out on people’s talents, and bad for public finances.

Box 3: What do we mean by economic inactivity?

According to internationally agreed definitions, people in the labour market fall into one of 3 groups: employed, unemployed and economically inactive. Economically inactive people are those without a job who have not sought work in the last 4 weeks and/or are not available to start work in the next 2 weeks. This differs from the definition of unemployment, where people are without a job but are seeking work and available to start. Many economically inactive people contribute to the economy in ways other than work, for example, by caring or studying to build their skills. However, the UK’s current high economic inactivity rate is unsustainable, leaving many people excluded from the labour market and holding back economic growth.

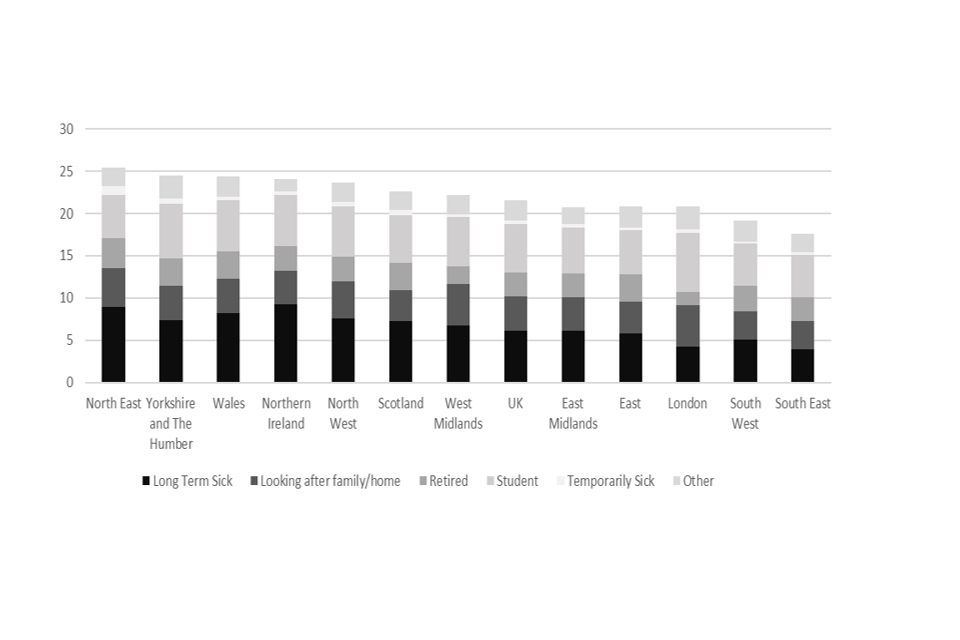

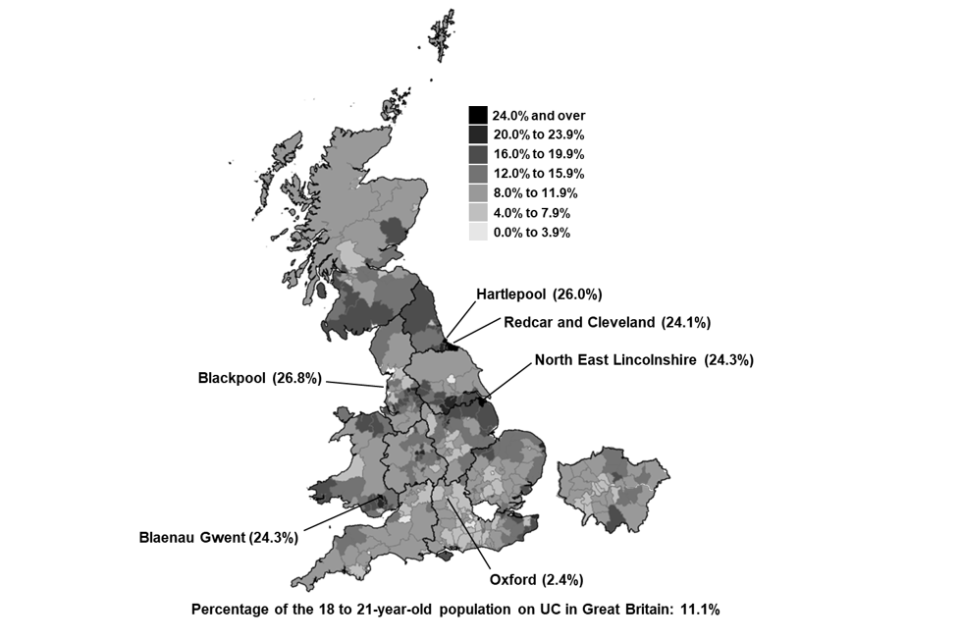

24. For too many people, labour market opportunities are shaped by where they live. Employment rates, earnings and access to skilled jobs vary significantly between areas. As the chart below shows, rates of economic inactivity are highest in the North of England, Wales and Northern Ireland, with, for example, around a quarter of people aged 16 to 64 economically inactive in the North East of England (25.6%) compared with just over 1 in 6 in the South East (17.7%).[footnote 18] Excluding students, of the 20 upper-tier local authorities in England with the highest rates of economic inactivity, 11 are in the North of England, while none are in the South East and just 2 are in London.[footnote 19] However, there are disadvantaged areas across the United Kingdom, and inequalities within regions are often greater than those between them.[footnote 20] In particular, economic inactivity is higher in some coastal and ex-industrial communities than other parts of the country, and there are areas with high levels of people not working in our major cities.[footnote 21] [footnote 22]

25. There are also notable differences in qualification levels between regions in England. London and the South East tend to have higher proportions of adults with degree-level qualifications compared to the North East and parts of the Midlands. Overall, areas with higher levels of deprivation often have lower levels of educational attainment, and areas with higher unemployment rates and lower average incomes typically have a higher percentage of adults with no qualifications.[footnote 23]

Figure 1: Economic inactivity rate by region and reason (July 2023 – June 2024)[footnote 24]

26. Too many young people leave school without essential reading, writing, maths or digital skills, or the support and opportunities to thrive at the start of their career. Nearly 900,000 young people (16 to 24-years-old) are currently not in work or education,[footnote 25] with many having special educational needs, low-level skills and mental health conditions.[footnote 26] Young people struggling with poor mental health and who lack basic qualifications face the greatest disadvantages.[footnote 27] For young people, a prolonged stretch of unemployment or economic inactivity at an early age can make it harder to find a job in the future, with negative impacts on the economy.[footnote 28]

27. Too many people are stuck in insecure, poor quality and often lower-paying work, which contributes to a weaker economy and also affects health and wellbeing.[footnote 29] There are labour market success stories across the UK but the overall economy has experienced a long period of sluggish productivity growth, with real earnings (after inflation) having barely grown since the 2008 financial crisis.[footnote 30] There are now 700,000 more working-age adults, and 900,000 more children living in poverty in families where someone works than in 2010/11.[footnote 31] In addition, people in low-paid work are relatively unlikely to leave it, with only 2 in 5 low-paid people in 2017 consistently earning enough by 2023 to no longer be considered low paid.[footnote 32] In-work poverty varies between different regions of the UK. The West Midlands and the North West have the highest rates of in-work poverty at 22% and 20% respectively. These regions also had the highest rates of in-work child poverty at 33% and 30% respectively. Northern Ireland and the North East have the lowest rates of overall in-work poverty at 12% and 13%, while Northern Ireland and Scotland have the lowest rates of in-work child poverty at 16% and 18%.[footnote 33]

Box 4: Rising economic inactivity in the UK, which is an outlier internationally

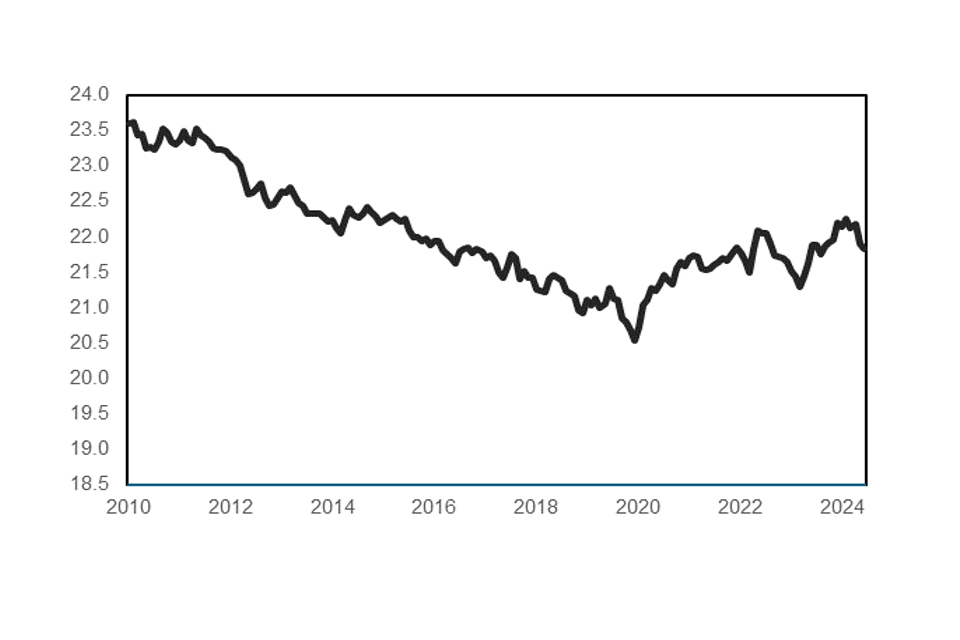

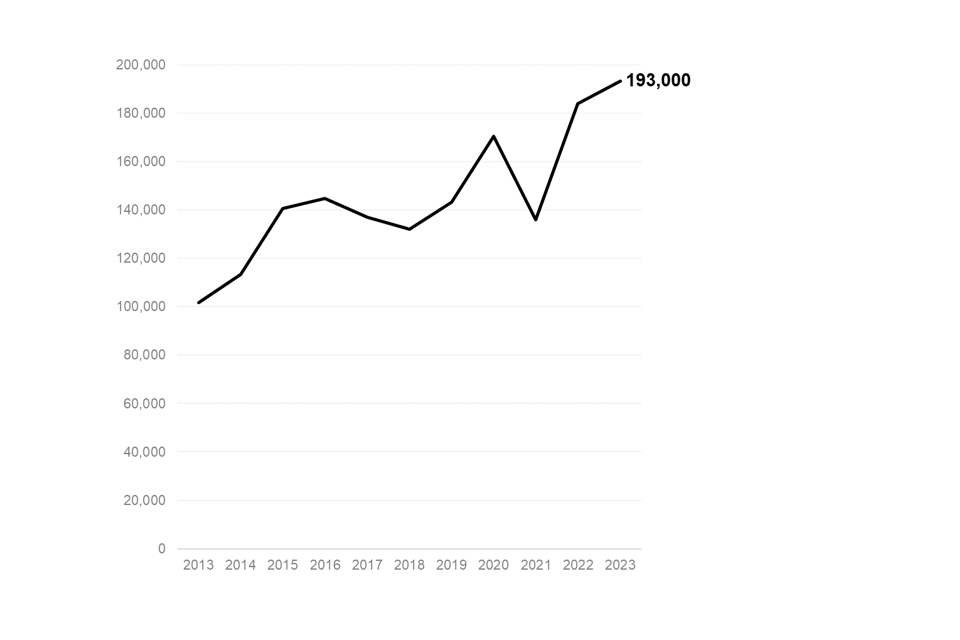

Rising labour market participation was a key driver of economic growth across the 2010s but this has reversed since 2020. The working-age participation rate peaked at 79.5% in early 2020, including rising participation among women, older workers and disabled people. This is likely to have reflected a number of factors, including policy changes (such as the rise in State Pension age and childcare support), changes in social norms and rising educational levels.[footnote 34] The UK’s economic inactivity rate has risen sharply since early 2020, increasing to 21.8% in June to August 2024. Over 700,000 additional people are outside the labour market compared to when the economic inactivity rate was at its 2020 low.[footnote 35]

Figure 2: Economic inactivity rate (16 to 64-year-olds Labour Force Survey)[footnote 36]

While there are many reasons for labour market inactivity, increases since 2020 have been primarily driven by long-term health conditions which remain at historically high levels.[footnote 37] The UK’s sustained rise in economic inactivity since the pandemic is not replicated in other major G7 economies.[footnote 38]

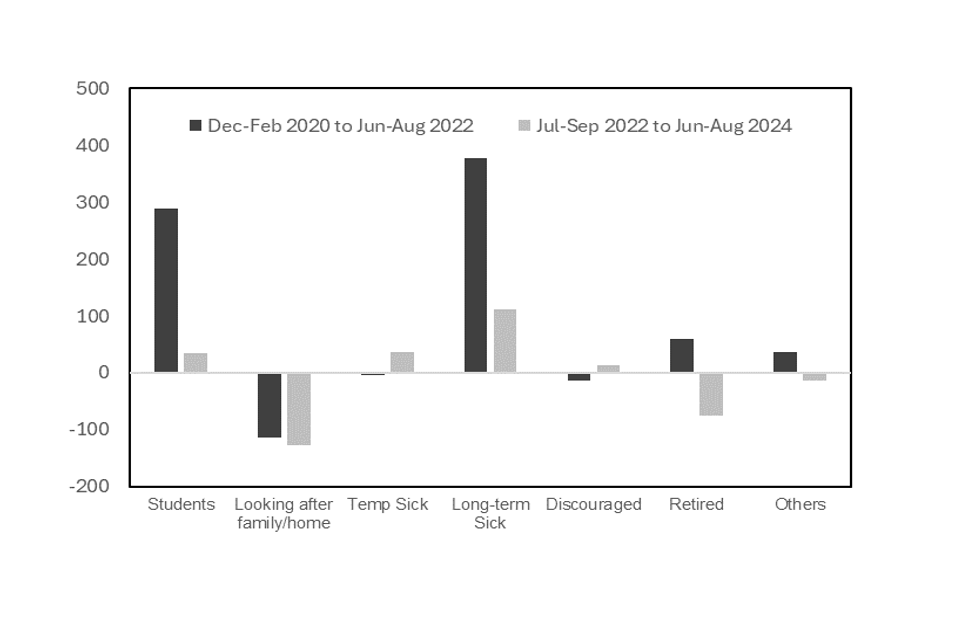

Figure 3: Change in economic inactivity by reasons (000s) (Labour Force Survey)[footnote 39]

The challenge of increasingly poor health is likely to continue, driven in part by the ageing population. The number of people living with major illness in England is projected to increase by over a third by 2040,[footnote 40] and the OBR projects the participation rate amongst the 16+ population to fall from around 63% today to around 61% over the next fifty years. However, if health continues to deteriorate across the population the participation rate could drop below 60%.[footnote 41]

28. Too many women who care for their families still experience challenges in staying and progressing in work. While the UK’s gender participation gap has been closing over recent decades, it is still larger than top performing economies, with a female economic inactivity rate in 2023 at 25.3% that was 7.3 percentage points higher than the male rate (18.0%).[footnote 42] Mothers on average experience a decline in participation and hours worked after having children, which persists over time. This drives down hourly pay for women and contributes to the gender pay gap.[footnote 43] While many mothers want to care for their children full time, survey data indicates around half of non-working mothers would prefer to work.[footnote 44] For many mothers, a lack of affordable and accessible childcare, inflexible working practices and fragmented and poor-quality information can make this challenging.[footnote 45] 5 million people are providing unpaid care and 59% of these are women. 1 in 5 women aged 55 to 59 are providing unpaid care.[footnote 46]

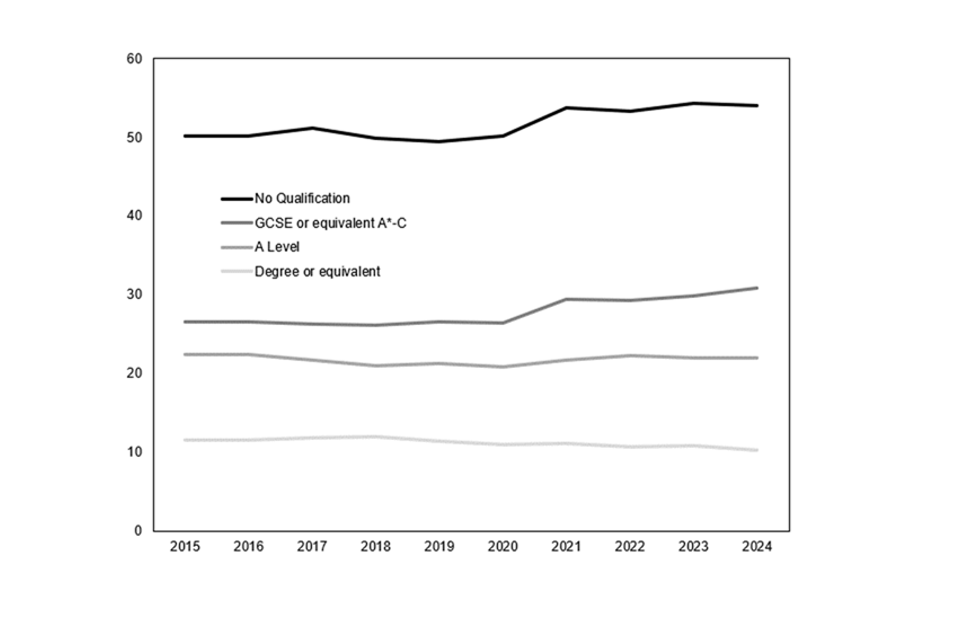

29. Too many employers cannot fill their jobs due to labour and skills shortages, holding back economic growth and undermining living standards. The number of skills shortage vacancies more than doubled between 2017 and 2022, with 36% of vacancies now due to skills shortages.[footnote 47] Global shifts such as the green transition and artificial intelligence will impact the distribution of jobs and skills further. We need a robust, skilled labour market to respond to and benefit from these changes. However, despite evidence that qualifications pay dividends for individuals and the taxpayer, participation in training is falling. UK employers invest half as much per employee in training compared to the EU average,[footnote 48] while employer investment in training has fallen by nearly 20% in real terms since 2011.[footnote 49] 33% of working-age adults in England do not have a Level 3 or above qualification, and 17% do not have a Level 2 or above qualification.[footnote 50] In Yorkshire and the Humber and the North East only 4 in 5 young people achieve a Level 2 (GCSE or equivalent A*- C) qualification by the age of 19 and around half achieve Level 3 (A Level or equivalent), making these the poorest performing regions in England.[footnote 51] Furthermore, economic inactivity is strongly correlated with low skills. The graph below shows that people with no qualifications are significantly more likely to be inactive than those who have a higher level of qualification.

Figure 4: Percentage of population aged 16 to 64-years-old, by highest qualification, that are economically inactive[footnote 52]

The case for fundamental reform of our health, employment and skills systems

30. These labour market challenges are serious. However, the current system is almost entirely set up to address the problems of the past, not those that we see today or are facing in the future. The current system does not allow us to deal with spiralling inactivity, an ageing population or increasing prevalence of ill health. It does not help ensure that young people get the education, skills and job opportunities that they need to kick-start their careers, and it does not enable people to get the chance to earn decent pay and to build skills and careers.

Health system

31. Our health system is struggling and waiting lists have been increasing. NHS referrals to elective treatment waiting lists in England increased from 4.4 million in January 2020 to 7.6 million in July 2024.[footnote 53] [footnote 54] Between 18 October 2023 and 1 January 2024, 33% of working age people who were economically inactive (excluding those who were retired) were on NHS waiting lists, in comparison to 19% of those who were either employed or self-employed.[footnote 55] There is insufficient focus on preventing the common health conditions, risk factors and health inequalities that limit people from engaging with work, and there is limited support to help disabled people or people with health conditions to stay in work (or get back into work quickly). This is critically important, as once people become economically inactive due to long-term sickness, they are highly unlikely to move into employment in the future.[footnote 56]

Employment support system

32. Our employment support system has been primarily focused on managing the benefits system and not on delivering a public employment service. It primarily engages with people who are unemployed and focuses on rapid job entry, which potentially misses the opportunity to find the right job for them. The system provides little support to those who are looking to find a new job, to progress in work, or to stay in work but need help to do so, such as carers.[footnote 57] It also pays insufficient attention to wider issues like health, skills, childcare and transport, which play a fundamental role in supporting people to enter, stay in or get on at work.

Skills system

33. Our current skills system is not delivering the skills that the country needs. Many adults with lower skills and qualifications disengage from learning after leaving education. Nearly 1 in 4 do not participate in any training after this point,[footnote 58] with the lowest-qualified and poorest adults the least likely to access further training.[footnote 59] While quality post-16 education has clear benefits,[footnote 60] many face barriers like cost, childcare responsibilities and work-related time pressures that hinder access to these opportunities.[footnote 61] Typically, the most disadvantaged people fall through the cracks and are more likely to experience unemployment scarring effects, which negatively impact their future career prospects, earnings and wellbeing.[footnote 62] Domestic skills shortages are widespread, increasing our reliance on migration and hindering economic growth.

34. The result is a system that is too siloed, which fails to join up health, work and skills support and is not rooted in local economies or driven by local needs.

Chapter 3: Tackling economic inactivity caused by ill health

35. Reversing the increase in economic inactivity caused by ill health is a national priority. A quarter of all people aged 16 to 64 have a long-term health condition that limits their day-to-day activities (therefore classing them as disabled), with disabled people nearly 3 times more likely (than non-disabled people) to be economically inactive.[footnote 63] This leads to significant adverse impacts for people, for the economy and for the public finances.

36. Many people who are off work with long-term health conditions want to work, with 600,000 stating that they would like a job at the moment.[footnote 64] However, too many disabled people and people with long-term health conditions face significant challenges in: finding work that can accommodate their needs, getting the right support to help manage their conditions, or having the right adjustments at work.[footnote 65]

37. Our approach – for individuals and employers – needs to reflect the scale of the challenges that disabled people and people with health conditions face.

38. This chapter sets out the drivers and impacts of ill health-related economic inactivity, and how the government is going to tackle this challenge, in 4 priority areas:

-

improving the health of the population so that more people can stay in and thrive at work

-

mobilising local leadership to tackle economic inactivity by better connecting work, health and skills support and increasing engagement with that support

-

supporting employers to promote healthy workplaces, and to recruit and retain workers with a health condition or disability

-

reforming the system of health and disability benefits to promote and enable employment

Many of the policy functions described in this chapter are devolved to Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. Where this is the case the focus of this chapter is on the actions the UK government will take in England. The UK government will work closely with the devolved governments to maximise positive outcomes and learning across the UK whilst respecting devolution settlements.

Ill health-related economic inactivity trends

40. Long-term sickness-related economic inactivity is at a near-record high.[footnote 66] Disability prevalence is also increasing, with 2.6 million (38%) more people in the working-age population classed as disabled compared to a decade ago. The employment rate of disabled people (53%) is nearly 29 percentage points lower than that of non-disabled people, and this employment ‘gap’ has stopped narrowing over the last 5 years.[footnote 67]

41. There has also been a decline in the health of those who are working. 4.1 million people are currently in work with a health condition that is work-limiting – an increase of 300,000 over the past year.[footnote 68]

42. More than half of those who are economically inactive due to long-term ill health are aged 50 to 64.[footnote 69] However, recent trends have been particularly concerning for young people, who have seen a greater proportional increase in comparison to older groups. The steepest increase has been for those aged 16 to 34, who account for 22.6% of those economically inactive due to ill health, an increase of 3.4 percentage points between 2019 and 2023.[footnote 70]

43. Ill health also affects the employment prospects of the friends and family members who provide unpaid care. There are untapped opportunities to prevent and reduce economic inactivity by exploring how those with care needs and those caring for them navigate the social care system.[footnote 71]

44. A range of complex and interacting factors have contributed to the rise in ill health-related economic inactivity since 2019. These include population ageing, as the last of the ‘Baby Boomer’ generation enter their 60s, a higher prevalence of ill health among people aged 16 to 64, particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic (affecting both mental and physical health)[footnote 72], and potentially, factors related to the benefits system: a combination of the strictness of ‘conditionality’ for jobseekers, administrative changes to health assessments, and differences in benefit rates, may have contributed to increases in the number of people claiming health-related benefits.[footnote 73]

45. People who are economically inactive due to long-term sickness are likely to face multiple barriers in returning to the labour market. Most have several long-term health conditions and no recent work history. They are also more likely (than the population as a whole) to have no qualifications, and some may also face other complex disadvantages, including homelessness, drug or alcohol addiction and contact with the criminal justice system.[footnote 74]

Box 5: Common risk factors

The most prevalent primary conditions in people who are economically inactive due to long-term sickness are mental health conditions, musculoskeletal (MSK) conditions, and cardiovascular disease (CVD),[footnote 75] with obesity being a key risk factor across all of these and a significant driver in and of itself.[footnote 76]

Mental health conditions are the most common conditions that affect younger working-age people who are economically inactive due to long-term sickness. They have been trending up over the past decade.[footnote 77] Of the rise in long-term sickness among 16 to 49-year-olds between 2019 and 2022, mental health conditions account for 25% (50,000 people).[footnote 78] The number of workers aged 16 to 34 who report that their mental health limits the type or amount of work they can do has increased more than four-fold over the past decade, and mental health is now the leading work limiting health condition among those aged 44 and younger.[footnote 79]

MSK conditions are the most common conditions that affect older working-age people who are economically inactive due to long-term sickness.[footnote 80] They were trending down prior to the pandemic but have since risen. Of the rise in long-term sickness among 50 to 64-year-olds between 2019 and 2022, 22% (40,000 people) is accounted for by MSK conditions.[footnote 81]

Of all the people who were economically inactive due to long-term sickness in 2023, 14.4% reported cardiovascular and digestive health problems (which includes diabetes) as their main health condition.[footnote 82] More than 1 in 3 heart attacks treated in hospital were in people of working age, and 1 in 4 people who have a stroke are of working age, with a third of stroke survivors not returning to work and an additional 16% reducing their working hours – this equates to around 11,000 people not able to work each year.[footnote 83] CVD disproportionately impacts on the most deprived communities and is a leading driver of health inequalities.[footnote 84]

Obesity, smoking, harmful alcohol consumption and physical inactivity are key drivers of ill health and premature mortality and are linked to mental health, MSK and CVD conditions. Those who smoke, drink alcohol at high levels, or have a Body Mass Index (BMI) of over 40, are more likely to be out of work than those who do not (controlling for factors such as level of education).[footnote 85] It has been estimated that nearly half a million people are unemployed or economically inactive due to these unhealthy behaviours.[footnote 86]

Most people who are economically inactive due to long-term sickness have multiple health conditions.[footnote 87] In 2023, 81% reported having more than one condition and 35% reported having 5 or more conditions.[footnote 88] This suggests that increasingly complex and interlinked health needs are keeping people out of work.

There are more working-age adults living with major illness in the most deprived areas (14.6%), which is more than double the rate in the least deprived areas (6.3%). Inequalities in working-age ill health are also projected to persist. 80% of the increase in the number of working-age people living with major illness between 2019 and 2040 (from 3 million to 3.7 million) will be concentrated in more deprived areas.[footnote 89]

The case for change

46. The impact on people who are locked out of the labour market is clear. Compared with employees (both part-time and full-time workers), those who were economically inactive because of temporary sickness were 8.9% more likely to report lower life satisfaction ratings. Meanwhile, those who were inactive because of long-term sickness or disability were 5.1% more likely to report lower life satisfaction than employees.[footnote 90] It is the purpose of the reforms in this White Paper to shift those trends in a positive direction.

47. The current system of support for disabled people and people with health conditions is centralised, fragmented and not set up to handle the challenge of ill health-related economic inactivity. Too often, disabled people and people with health conditions cannot get the help they need or cannot access support in a way that is joined up between services. To tackle these trends, preventative health interventions, a stronger role for local areas in integrating support, reforms to the benefits system and support for employers to play a proactive role, are all needed.

The future system we are aiming for

48. Tackling economic inactivity will require a joined-up approach right across government, the NHS, employment services, local areas and employers in England, building on work to better integrate health and employment support, including through the Joint Work and Health Directorate of the Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC) and Department for Work and Pensions (DWP). Our future system in England will be based around a coordinated approach that prioritises prevention and early intervention, as well as tackling the risk factors and inequalities that drive economic inactivity. Improving the health of the population will enable more people to stay in and thrive at work. We will learn and embed best practice from across systems, including within the devolved governments. Local leaders know best the challenges local people and employers face. They are best placed to shape a coherent offer to meet their needs from the range of support and opportunities available in their area, and to increase engagement with people who are economically inactive and outside the workforce and who are, too often, written off. We will empower local areas and leaders in England to take a leading role in addressing economic inactivity. We will also work to ensure that more people are engaged with support that can help them to work.

Box 6: The Joint DWP and DHSC Work & Health Directorate

This was set up in recognition of the significant link between work and health and to improve employment opportunities for disabled people and people with health conditions. The goal of the Directorate is to open up opportunities to good work and to support a healthier, more productive and inclusive nation, by helping more disabled people and people with health conditions to: get appropriate work, get on in that work, and to return to work as quickly as possible if they leave it.

This is achieved through the delivery of evidence-based programmes, trials and tests, as well as by working with employers, local areas and wider government, to remove the additional barriers these groups face when in and out of work, with a focus on better aligning the work and health systems.

Priority 1: Improving the health of the population, which will enable more people to stay in and thrive at work

49. Our health system is struggling. Lord Darzi’s independent investigation into the NHS in England found that it is not contributing to national prosperity as it could be. For example, the waiting list for elective treatments rose to over 7.6 million in June 2024, and Lord Darzi highlighted that more than half of those on the waiting lists for inpatient treatment are working-age adults.[footnote 91] In its 2023 Fiscal Risk and Sustainability Report, the OBR estimated that, relative to the elective waiting list in England remaining flat at 2022 levels, a scenario where the waiting list halves over 5 years would reduce working-age inactivity by around 25,000.[footnote 92]

Fixing the foundations of the NHS

50. The government will deliver an additional 8,500 new mental health staff and provide 40,000 extra elective appointments each week. This will enable people to get the treatment they need more quickly, reducing waiting lists and returning to NHS constitutional standards that 92% of patients should wait no longer than 18 weeks from referral to treatment. While the direct impact of reducing waiting lists on economic inactivity is inconclusive at present, it is an important step alongside other interventions to support people to enter and stay in work.

51. Building on wider work to reduce waiting times, we will deploy Getting It Right First Time Further Faster teams to support 20 Trusts in areas of England with the highest numbers of people off work sick.[footnote 93] To ensure community services can also address their waiting times in areas of high unemployment and provide support to hospitals, we are also working jointly between DWP, DHSC, and Getting It Right First Time teams to deliver a MSK Community Delivery Programme. This will work with Integrated Care Board leaders to further reduce waiting times and improve data and metrics and referral pathways to wider support services. Jobcentres and other, locally led employment support will work with Getting It Right First Time teams to enable the end-to-end support people need: from treatment to rehabilitation to good work and health.

A greater focus on prevention to reduce working-age ill health

52. Tackling the conditions that drive economic inactivity requires a fundamental shift towards prevention and early intervention. Under the Health Mission, we will move from a model of sickness to one of prevention – keeping people well and in work for longer, addressing health inequalities and closing the gap in healthy life expectancy.

53. Health inequalities mean poorer health and a reduced capacity to be economically active for many. Our Health Mission in England will therefore also address the risk factors for poorer health as well as the social determinants of health, with the goal of halving the gap in healthy life expectancy between the richest and poorest regions. This is not just a health matter – it makes economic sense and is central to economic growth.

54. To achieve these aims, wide-ranging actions over a decade or more are required. The 10-Year Health Plan will set out broader actions to support the shift to prevention across the health and care system in England, which will include the conditions and risk factors driving economic inactivity.

55. To tackle poor mental health, the leading driver of ill health-related inactivity,[footnote 94] the government has committed to continuing to expand access to NHS Talking Therapies for adults with common mental health conditions in England. This is expected to increase the number of people completing courses of treatment by 384,000 and increase the number of sessions. There is extensive literature and studies showing that Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) and NHS Talking Therapies more widely have significant positive health impacts, as well as improving employment outcomes.[footnote 95] Currently over 90% of NHS Talking Therapy Services in England also provide access to Employment Advisers, with an aspiration that by March 2025 99% of NHS Talking Therapies services in England will offer employment support as part of their service.[footnote 96] The government will also continue expansions to Individual Placement Support (IPS), increasing access for people with severe mental illness by an additional 140,000 people by 2028/29. The OBR judged that both these expansions of support would boost employment by 20,000 in 2028/29.[footnote 97] The IPS scheme helps thousands of people with severe mental illness to find and keep employment. IPS for severe mental illness is an employment support service integrated within community mental health teams for people who experience severe mental health conditions. It is an evidence-based programme that helps people find and retain employment through intensive, individualised support, rapid job search followed by a placement in paid employment, and unlimited in-work support for both employers and employees. In August 2024 38,704 people accessed IPS for severe mental health services in the previous 12 months, meaning we are above our trajectory to meet the end of year target of 40,500 people accessing these services.[footnote 98]

56. Tobacco remains the single largest cause of preventable ill health and mortality and is a key risk factor for CVD and respiratory diseases, which are leading drivers of economic inactivity due to ill health. The government’s landmark Tobacco and Vapes Bill will create the first smoke-free generation, helping to reduce the around 80,000 preventable deaths from smoking each year, gradually ending the sale of tobacco products across the country, and banning vapes and other nicotine products from being deliberately branded and advertised to children.[footnote 99] It will also reduce the burden on the NHS and the taxpayer.

57. At Autumn Budget 2024, the government re-committed to the tobacco duty escalator for this Parliament, increasing rates by 2% above the Retail Price Index (RPI). To reduce the gap with cigarette duty, the duty on Hand Rolling Tobacco will rise by a further 10% (12% in total) above RPI this year. High and increasing rates of tobacco duty are proven to reduce smoking prevalence, as well as supporting the public finances.

58. The government also announced an increase in alcohol duty in line with inflation on all non-draught products, alongside a cut in duty rates for lower strength products sold on draught. This decision encourages responsible drinking in social, controlled settings, recognises cost of living pressures, and reflects the connection between excessive alcohol consumption, ill health and economic inactivity.

59. We are committed to continuing to develop the evidence base on how health interacts with the labour market, to ensure the government can prioritise programmes that improve people’s health and help them back to work. This includes a forthcoming ONS evaluation on the impact of NHS Talking Therapies, as well as exploring opportunities to utilise the data platform created by Our Future Health in partnership with the NHS, the largest health study of its kind. We will build on evidence published by the ONS which finds that bariatric surgery leads to a sustained increase in employee pay and the probability of being in work (as a paid employee).

Box 7: Obesity

Obesity remains a significant health challenge. 64% of adults aged 16 years and over were overweight or living with obesity in 2021.[footnote 100] Childhood obesity has also increased over the last few decades with 36.6% of Year 6 children overweight or living with obesity in 2022/23.[footnote 101]

Obesity is a key risk factor for leading conditions driving health-related economic inactivity (CVD and MSK).[footnote 102]

The prevention of ill health is a clear priority for this government, and we remain committed to tackling obesity. As announced in the King’s Speech, we are committed to restricting television and online advertising of less healthy food to children, empowering councils to block the development of new fast-food shops outside schools, and banning the sale of high-caffeine energy drinks to under-16s.

Reformulation of everyday food is also a key element of preventing obesity. The sugar reduction programme led to reductions in sugar across a range of foods between 2015 and 2020, with some categories achieving higher reductions such as approximately 13.5% for yogurts and approximately 14.9% for breakfast cereal.[footnote 103]

The Soft Drinks Industry Levy has also been a successful mechanism to drive reformulation in the soft drinks sector, with a 46% average reduction in sugar in soft drinks between 2015 and 2020.[footnote 104] To ensure the Soft Drinks Industry Levy remains fit-for-purpose and effective, the government committed at Budget to ensure the levy increases with inflation - to maintain incentives for soft drinks producers to reduce their sugar content - as well as to review its sugar content thresholds and the exemption for milk-based drinks.

The government is committed to reducing the number of people becoming overweight and obese and wants to work with the sector to consider all levers to further encourage food and drink reformulation to help tackle obesity, in a way that protects consumers and with a focus on voluntary and regulatory measures.

The collaboration between the government and Eli Lilly will see plans for a place-based real-world evidence study being conducted in Manchester. This aims to evaluate the effectiveness of tirzepatide on obesity and its impact on obesity-related conditions in a real-world setting, to improve our understanding of how obesity medications can potentially improve health, health inequalities and obesity-related absences. As well as data on patient outcomes, such as a reduction in rates or even reversal of conditions such as diabetes, CVD and poor mental health, the study will also improve the evidence base on non-clinical outcomes of weight loss, including the health economic impacts through potential reductions on health service usage and changes in participants’ employment status and sick days from work.

Priority 2: Mobilising local leadership in England, and working closely with devolved governments, to tackle economic inactivity by better connecting work, health and skills support and increasing engagement with that support

60. In addition to improving population health, we also need a step change in how the UK government funded support to help those who are economically inactive back into the workforce is integrated with local provision.

61. DWP funded employment support provision has focused overwhelmingly on the unemployed, while local help offered – by local councils, the NHS, voluntary sector, colleges and housing associations – is often fragmented and difficult to navigate.

62. The government will therefore support and enable local areas in England to take the lead in shaping a coherent offer of support across work, health and skills, and to effectively engage local people and local employers in that offer. That means: every area having a plan to tackle economic inactivity, backed up by new funding for supported employment; trailblazers to go further and faster towards a locally led approach; a strong focus on increasing levels of engagement with support; and a new role for government in making a more locally led system a success. In Wales the trailblazer will be jointly designed with the Welsh Government to ensure all aspects of the new jobs and careers service partner effectively with devolution of non-Jobcentre Plus employment support funding and areas of devolved competence.

Local Get Britain Working Plans and devolved funding in every area

63. To make this new approach a reality, we will provide all areas in England with resource to produce a local ‘Get Britain Working Plan’, focused on reducing economic inactivity among their local population, and to convene key local stakeholders, people and partners who have a role in delivering on it.

64. Going with the grain of the government’s wider approach to devolution in England, we expect these plans to be developed by combined authorities where they exist, and across groups of local authorities elsewhere. In mayoral authorities, these plans will be guided by, and support, the aims of their Local Growth Plans and link to other existing strategies and plans such as Local Skills Improvement Plans.

65. The thinking behind Get Britain Working Plans has been informed by the 1,900 responses to the fit note Call for Evidence which include insights from employers, healthcare professionals and patients about the role of the fit note process in supporting people to stay in work while they manage their healthcare condition.[footnote 105]

66. The purpose of local Get Britain Working Plans will be to set out an analysis of the economic inactivity challenge in each local area and the actions that will be taken to improve outcomes across the local population. This should aim to draw on the full range of provision and resources in a local area, as well as maximising the contribution of local relationships and assets. This includes local authorities, the NHS, training providers, Jobcentre Plus, the voluntary sector, employers and trade unions.

67. Local areas should actively involve these partners, as well as local people, in the development of their plans, with the aim of establishing or further enhancing forms of local collaboration that can support successful delivery.

68. To kick-start these plans, the government will devolve funding over the coming years to support those who are economically inactive back to work, starting with £115 million going to local areas in 2025/2026 to deliver Connect to Work, a new supported employment programme for people who are economically inactive. This will be the first strand of funding within a new Get Britain Working Fund. Part of this funding will go to Wales.

69. From 2026/2027 Connect to Work will support up to 100,000 people per year. Local areas will be responsible for delivering the provision and will use the ‘place, train and maintain’ model, which has a strong evidence base from a range of international sources,[footnote 106] [footnote 107] as well as from trials in South Yorkshire and the West Midlands.[footnote 108]

70. The development of local Get Britain Working Plans will support an integrated offer of local work, health and skills support. This should include the contribution of new and existing provision such as Connect to Work and the Ministry of Housing, Communities and local government-led UK Shared Prosperity Fund, which remains a source of locally controlled funding that can be used to support the economically inactive population.

71. Funding from DWP for supported employment provision will be included in the new Integrated Settlement from 2025/2026, which will initially be available to the Greater Manchester and West Midlands Combined Authorities. The Integrated Settlement will be available to other eligible areas in England from 2026/2027. Devolution of supported employment funding is part of a wider set of reforms which will also increase transport, adult education and skills, housing and planning powers to help drive growth across England.

Trailblazers to go further and faster

72. To accelerate a more locally led and joined-up approach to tackling economic inactivity, we will launch a set of place-based trailblazers in eight areas in England and Wales to run during 2025/2026. These trailblazers will be at the forefront of designing how a model of locally joined-up work, health and skills support will work in practice. They will enable participating mayoral authorities in England and the Welsh Government to maximise the impact of existing resources, including supported employment funding, the UK Shared Prosperity Fund, WorkWell pilots (where operating – see Box 8), wider NHS-led employment support as well as local authority and voluntary sector provision. We will also focus activity to design and test the new jobs and careers service in trailblazer areas, to help shape a fully integrated local offer in England and Wales.

Box 8: WorkWell

WorkWell brings together Integrated Care Boards, local authorities, Jobcentre Plus and other local organisations to design and deliver services that help to keep people with health conditions in work or to get them back into the workforce quickly.

From 1 October, 15 WorkWell pilot services have begun to deliver an early intervention work and health assessment service to reduce the flow of people into economic inactivity, with low-intensity holistic support for health-related barriers to employment, to 56,000 participants by March 2026. They also offer a common point of access into local support services, whether health, employment or skills, to simplify the support landscape for participants. Participation will be voluntary and will include people in and out of work, regardless of benefit entitlement.

73. We will work closely and at pace with mayoral authorities to mobilise these trailblazers around a set of common core elements to ensure we maximise the learning from their implementation:

-

clear plans for delivery with agreed outcomes – including the proposals being tested; strong performance oversight and management; how existing and new resources will be used; and measurable goals for tackling economic inactivity

-

governance and management – including accountabilities and responsibilities across partners, and arrangements for data sharing

-

evaluation and support – an agreed and common approach to measuring impact, including an evaluation strategy for tests and trials,[footnote 109] along with a support programme to develop capability, capacity and infrastructure

74. We will design the detail of what is tested in partnership with mayoral authorities, in 2 key areas:

-

targeted expansion of provision – testing additional early intervention support to keep people in work or get new qualifications to work (pre-Work Capability Assessment), wider employment, health and skills support, case management or support to address individual barriers to work

-

enhanced engagement activity – to reach people out of work and not in regular contact with employment, health or local services – including those claiming Universal Credit without requirements to prepare for work or attend meetings

75. Given that poor health is a leading cause of economic inactivity,[footnote 110] the local health system will play a vital role in all the trailblazers. In addition, at least 3 of the trailblazer areas will also receive a share of £45 million funding for Integrated Care Systems to test ambitious reforms in how the NHS operates with local partners to address the health drivers of economic inactivity. These areas will be selected on the basis of having a combination of high rates of health-driven economic inactivity and people in work with health conditions, communities more likely to be affected by deprivation and inequality, and with demonstrated proactive action on integrating work and health support. The focus of this activity will be improving population health outcomes and reducing health-related economic inactivity.

76. We will work with Mayoral Combined Authorities and London to establish the most appropriate type of trailblazer for their areas. Alongside our plans for Youth Guarantee Pathfinders (set out in Chapter 4), this means that all Mayoral Combined Authorities, the 4 sub-regional partnerships in London, and Wales will receive some funding for testing or trailblazer activity in 2025/2026. We will discuss arrangements for Wales with the Welsh Government.

Box 9: The Pathways to Work Commission[footnote 111]

In July 2024 the Pathways to Work Commission published its report setting out how to give the 6,000 economically inactive people who live in Barnsley a pathway to work. The Commission’s research found that 7 in 10 currently economically inactive people would like a job that is aligned to their skills, interests and circumstances. They highlighted the many problems with the current approach to addressing growing levels of economic inactivity, including perverse system incentives, confusing support offers and the lack of clarity on the role of employers.

The Commission identified the need to take a whole-system approach to supporting people who are economically inactive and making good work accessible to everyone, with the Rt Hon Alan Milburn, the Pathways to Work Commission Chair, calling for a radical new approach that is: ‘built on a new national ambition to build a more inclusive economy where people have a right to work, and an expectation that those who can should be helped to do so. Tackling economic inactivity must become the national mission shaping welfare and employment policy over the next decade. That will require action across government but also by employers, local authorities, charities, communities and, of course, citizens themselves’.

The Commission identified 6 themes it sees as critical to addressing economic inactivity locally: leadership and funding, tailored support, work that is worth it, business engagement, health interventions and improved education. These themes informed the development of a South Yorkshire proof of concept proposal that will start to sort the system, prepare the jobs and take the journey with people.

Increasing engagement with those who are economically inactive

77. A key objective from shifting to a more locally led approach to tackling economic inactivity – and reforming Jobcentre Plus – is to increase the quantity and quality of engagement with those outside the workforce. It cannot be right that so many on health-related benefits are effectively written off and offered little support. Our goal is for many more people to be on a pathway towards employment, in particular those who do not currently have any contact with Jobcentre Plus.

78. Increasing engagement is the first essential step to delivering better employment outcomes. We want to test new ways of keeping in touch more regularly, offering a conversation and encouraging people to take the first step on a journey towards employment. Our trailblazers will provide an opportunity to explore how we can increase levels of engagement, working closely with charities, local government, the health service and disabled people and people with health conditions themselves.

A new role for the UK government

79. Finally, to support the development of a more locally led system of support in England for those who are economically inactive, the role of the UK government needs to evolve. We are committed to providing local areas with the support they need to develop their plans and to build capability and infrastructure in England. That includes working together on:

-

better use of data. The government wants local areas to have improved data to understand local population needs and to help design future programmes. We also need better data to track outcomes and develop the evidence base

-

accountability and governance. The government will work with local areas to create suitable frameworks, where these are not in place, to underpin the relationship with central government, to agree outcomes and to determine how different partners should be held accountable for results

-

consistent strategic geographies. The English Devolution White Paper will set out plans to create a system of consistent strategic geographies across England, which will provide the basis for a more locally led approach

Priority 3: Supporting employers to promote healthy workplaces and to recruit and retain workers with a health condition or disability

80. To take a comprehensive approach to tackling economic inactivity, we must ensure that employers have the support they need to recruit and retain disabled people and those with a health condition.

Employers have a key role in creating and maintaining healthy and inclusive workplaces

81. Poor health of the working-age population imposes a large cost on employers, including: poor workplace health impacting performance; costs due to sickness absence; loss of valuable experience when employees drop out of work, and recruitment costs to replace them; and restricted access to the widest pool of potential talent.[footnote 112], [footnote 113], [footnote 114]

82. Employers stand to benefit from promoting workplace health and taking action on preventable illnesses. In 2022/2023, an estimated 35.2 million working days were lost due to work-related illness and non-fatal workplace injuries in Great Britain, the majority (31.5 million days) because of work-related illness.[footnote 115] Work-related MSK conditions make up around a quarter of all self-reported cases and work-related stress, depression, or anxiety make up around half of all cases.[footnote 116]

83. Alongside the steps the government is taking, employers have a vital role to play through their recruitment practices in creating inclusive workplaces that protect health and support retention and rehabilitation for disabled employees and those with health conditions. The evidence is clear: once someone loses touch with the labour market, their chances of getting back into employment are diminished.

84. The majority of employers recognise the link between work, health and wellbeing, and their role in relation to this.[footnote 117] Previous studies have found that employees consider worker health to be a collective responsibility between employers, the state, and individuals.[footnote 118] We know that many employers are excellent at creating inclusive workplaces in relation to disability, health, and wellbeing. Many others recognise the value in doing so and would like to take action but need support and confidence to do so.