Tackling Domestic Abuse Plan - Command paper 639 (accessible)

Updated 1 September 2022

Applies to England and Wales

This is everyone’s responsibility. Let’s stop domestic abuse now.

March 2022

Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for the Home Department by Command of Her Majesty

CP 639

Forewords

Rt Hon Priti Patel MP, Home Secretary

Domestic abuse is the most common form of violence against women and girls.

In England and Wales, 2.3 million people are known to have experienced it in one year, 1.6 million of them women. It is likely that we all know someone who is being hurt in this way, at the hands of a person who is supposed to make them feel safe and secure. Despite being such a pervasive and insidious crime, it too often goes unnoticed by others.

The COVID-19 pandemic made domestic abuse loom larger in the public’s conscience. We must not lose that focus. Through this plan, we will deliver the practical steps needed for the whole of society to say, ‘enough is enough’.

This government has already taken steps to change things, with funding to increase support for victims and survivors, the introduction of coercive and controlling behaviour as an offence in 2015, and the passing of our landmark Domestic Abuse Act 2021, which recognised that children too can be victims of domestic abuse. This plan sets out how we will invest over £230 million to deliver many of the act’s provisions to bring about a response from all parts of society, to overcome domestic abuse.

This plan will place greater focus than ever before on preventing abuse. We will do this by improving our understanding of what works to prevent domestic abuse, and using education as a tool to address the harmful attitudes and behaviours which can start young and can lead to individuals becoming abusive. We will ensure victims and survivors and their children have access to safe accommodation.

We will be more robust and relentless in our response to domestic abuse perpetrators, whether through electronic tagging, innovative behaviour change programmes, or tougher sentences. And we will examine how to deal with the most harmful abusers, including options for a register of domestic abuse offenders.

It is vital we take the onus off victims and survivors, and that we consider what more needs to be done so they can get the support they need at work and focus on rebuilding their lives. That is why the government will review whether the current statutory leave provision for employees does enough to support victims and survivors who are escaping domestic abuse. We will set out any next steps later this year.

And why the government will be investing a minimum of £47.1 million over three years into support services. We will make the police, family courts, and criminal justice system easier for victims and survivors to navigate. And we will make it easier for them to disclose abuse through continued funding of vital helplines, and to get the tailored support they need from specialist and ‘by and for’ support services.

Our approach is all about enabling the whole system to operate with greater coordination and effectiveness. This will include training for those professionals most likely to encounter domestic abuse to better identify it and refer victims and survivors to appropriate support, including up to £7.5 million investment into interventions in healthcare settings. Reforms to domestic homicide reviews will improve our understanding and drive down the frequency of these terrible crimes.

This plan for tackling domestic abuse is fully aligned with the Tackling Violence Against Women and Girls Strategy that we published last Summer. Both that strategy and this plan are informed by the unprecedented 180,000 responses we received to the Violence Against Women and Girls call for evidence. They echo the voices of victims and survivors.

It is vital for both to recognise the disproportionate impact that domestic abuse has on women, and to ensure male victims and survivors get the support they need. That is why we have published a refreshed supporting male victims document.

Domestic abuse is everyone’s business, and we need to stop it now.

Rachel Maclean MP, Minister for Safeguarding

Domestic abuse causes untold harm and misery in our society. Victims and survivors endure horrific ordeals that can stay with them for the rest of their lives.

Their experiences must drive our determination to confront these awful crimes wherever and whenever they occur.

This plan recognises that women and girls are disproportionately affected by domestic abuse. Only by understanding the gendered nature of this crime and recognising the specific needs of all victims and survivors, can the whole of society mount an appropriate response.

Interventions need to begin at an early age. It is vital that we embed attitudes and behaviours which reduce the likelihood of future abusive behaviour. The new relationships, health and sex education curriculum will help do this.

The plan also sets out actions to enable relevant professionals to better recognise and act upon abusive behaviours. By expanding the Ask for ANI codeword scheme into Jobcentre Plus settings, we will make it easier for victims and survivors to seek help and support.

We are taking action to bring more domestic abuse perpetrators to justice and reduce reoffending. This includes next steps in our rollout of domestic abuse protection notices and domestic abuse protection orders, a key provision in the landmark Domestic Abuse Act 2021, and a commitment to establish a set of standards for perpetrator interventions. The plan also includes measures to drive down the number of domestic homicides, of which there are still far too many, and improve our knowledge of suicides that take place in the context of domestic abuse.

It is essential that victims and survivors can access a wide range of support. They have suffered terribly and the help available to them can make all the difference. The plan recognises this and among its many commitments sets out steps to strengthen the provision of specialist and ‘by and for’ services and ways to encourage employers to go further in their support for staff who may be facing domestic abuse. We take a whole family approach, which recognises children as victims and commits to increasing the Children Affected by Domestic Abuse fund.

This plan calls for more financial sector firms to sign up to the Financial Abuse Code, which is critical. It will support our efforts to prevent economic abuse and help deliver the best possible outcomes for victims and survivors.

Every case is different, but there are a number of core questions that must drive our approach, such as ‘What could have been done to prevent the abuse or intervene earlier?’ and ‘What more could we do to support the victim or survivor?’.

By asking these questions, and by seeking the answers at every turn, we will transform our response to domestic abuse. That is what this plan is designed to achieve.

None of this would have been possible without the voices of victims and survivors who responded to the Violence Against Women and Girls call for evidence. Their testimonies were integral to the development of this plan. So too was the expertise and insight, for which I am hugely grateful, of charities, police, and frontline professionals.

Domestic abuse may often take place behind closed doors, but we will not let this issue be hidden from view. By asking the right questions and by sticking to this plan, we will protect the public, root out the abusers, and make our society safer.

Introduction

Domestic abuse is horrendous and pervasive, and still too often hidden from view. It turns victims’ and survivors’ closest relationships from what should be sources of love and security into sources of pain, fear, and anxiety. This reality is far too common; the 2019-20 Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW)* estimated 2.3 million people experienced it in the previous year. [footnote 1] Women are more likely to be impacted by domestic abuse [footnote 2] and domestic homicide, [footnote 3] and men are most likely to be the perpetrators. [footnote 4] Domestic abuse is the most prevalent form of violence against women and girls**, and its consequences are enormously harmful. Around one in five homicides are related to domestic abuse [footnote 5] and we are concerned about its effect on suicides.

Crime Survey for England and Wales

* The Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) is a nationally representative face-to-face victimisation survey, in which people resident in households in England and Wales are asked about their experiences of a range of crimes in the 12 months prior to the interview. This includes self-completion modules on certain topics, including domestic abuse. For the crime types and population it covers, the CSEW provides a better reflection of the true extent of crime experienced by the population than police-recorded statistics, because the survey includes crimes that are not reported to, or recorded by, the police.

** The term ‘violence against women and girls’ refers to acts of violence or abuse that we know disproportionately affect women and girls. Crimes and behaviour covered by this term include rape and other sexual offences, domestic abuse, stalking, ‘honour’-based abuse (including female genital mutilation, forced marriage, and ‘honour’ killings), as well as many others, including offences committed online. While we use the term ‘violence against women and girls’, this refers to all victims and survivors of any of these offences.

The COVID-19 pandemic only exacerbated what is an already horrific experience faced by domestic abuse victims and survivors. Lockdown left them, including children, more vulnerable than ever, as they were spending far more time at home with abusers and away from others who might realise something was wrong. That said, domestic abuse affected millions before the COVID-19 pandemic, disproportionately women. [footnote 6] It will continue to do so unless we all take responsibility and act.

The brave, harrowing testimonies of victims and survivors of domestic abuse in response to the Violence Against Women and Girls call for evidence, made plain how a perpetrator’s behaviour has a lasting impact on a victim’s and survivor’s life. The government thanks all those victims and survivors who courageously gave their contributions, which were an invaluable asset in the development of this plan.

More needs to be done to hold perpetrators to account and support victims, I was blamed.

Call for evidence, victim and survivor survey.

In the past, the onus has too often been placed on the victim and survivor to take action. This plan sets a new course. It vigorously targets those who perpetrate domestic abuse to prevent first-time, repeat, and serial offending. It will set out the building blocks for an enhanced system that will aim to prevent domestic abuse from happening in the first place, deliver better outcomes for victims and survivors, as well as one that is unrelenting in the pursuit of perpetrators and unequivocal in insisting it is they who need to change their behaviour.

What we have achieved

Since 2010, we have made great strides in our efforts to tackle domestic abuse and wider violence against women and girls, introducing several new measures:

- in 2011, we commenced the Domestic Homicide Review (DHR) process so lessons can be learnt to reduce the number of domestic homicides

- in 2015, we introduced the offence of controlling or coercive behaviour through the Serious Crime Act 2015 to clamp down on these insidious forms of behaviour, underscoring that domestic abuse goes well beyond only physical violence

- in 2020, the Department for Education made Relationships Education mandatory in all primary schools and Relationships and Sex Education mandatory in all secondary schools

- in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, we provided over £28 million to support domestic abuse organisations in delivering vital services to victims and survivors

- we also launched the #YouAreNotAlone campaign and Ask for ANI (Action Needed Immediately) codeword scheme to increase awareness among victims and survivors of how to safely access help and support

In April 2021, the landmark Domestic Abuse Act 2021 gained Royal Assent. This legislation provides the tools and powers for this plan to drive down the number of people who face domestic abuse and better support victims and survivors. Its many reforms include:

-

Updating the definition of domestic abuse so that it recognises children as victims and economic abuse as a form of domestic abuse

-

A statutory duty on local authorities relating to the provision of support to victims and survivors and their children within safe accommodation. This has been supported by £125 million of funding in 2021-22 to enable local authorities to deliver it.

-

New domestic abuse protection notices (DAPNs) and domestic abuse protection orders (DAPOs) to bring together the strongest elements of existing protective orders into a single, comprehensive order. This will mean we have a more efficient and robust response to, and management of, domestic abuse perpetrators.

-

The creation of new offences of non-fatal strangulation and threats to disclose intimate images means that abusers will face the full force of the law.

-

Family court reforms which prohibit cross-examination of victims and survivors by perpetrators, provide automatic eligibility for special measures to support victims and survivors of domestic abuse, and clarify the availability of barring orders under Section 91(14) of the Children Act 1989.

-

Establishing the role of the Domestic Abuse Commissioner as an independent voice who will stand up for victims and survivors and, among other responsibilities, hold public bodies to account.

But we know we need to do more.

Building on our achievements

This plan seeks to build on the work of previous strategies [footnote 7], [footnote 8] and to complement the Tackling Violence Against Women and Girls Strategy published in July 2021.

It will also set out how various aspects of the Domestic Abuse Act 2021 will be delivered through:

- A whole pillar dedicated to preventing domestic abuse from ever happening in the first place. This includes further actions to enhance the delivery of the new Relationship, Sex and Health Education curriculum so young people have greater awareness and understanding of abusive behaviours.

- More support for victims and survivors. This plan will set out a multi-year funding package to deliver community-based support services, how the duty for accommodation-based support will be delivered, and a commitment to review whether the current statutory leave provision for employees does enough to support victims and survivors.

- Tougher, more robust actions which deal with domestic abusers. These include next steps in the delivery of DAPNs and DAPOs, a commitment to consider options for more robust management of domestic abusers, including the option of creating a register of domestic abusers, and provisions for electronic monitoring of the most harmful perpetrators.

The plan also details how the government will respond to the recommendations in HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services (HMICFRS) reports to improve the response to domestic abuse. There will also be more information on the Domestic Abuse Commissioner’s role, including her oversight on Domestic Homicide Review recommendations and family courts and a new victim engagement mechanism.

Why we must tackle domestic abuse

Domestic abuse is a complex and multi-faceted form of crime. It can be physical, verbal, sexual, emotional, psychological, economic, a combination of these, and include many other forms of harmful behaviour. There is no one type of domestic abuse, nor is there one solution to remedy it. This is reflected in the statutory definition of domestic abuse we passed in the Domestic Abuse Act 2021, which sets out numerous forms of behaviour, any one of which can constitute domestic abuse, if both the victim and survivor and perpetrator are “personally connected”. (Section 1 of the Domestic Abuse Act 2021 provides greater detail on the behaviour which constitutes “domestic abuse”, Section 2 of the Domestic Abuse Act 2021 provides greater detail on what constitutes “personally connected”).

And while anyone can be a victim and survivor of domestic abuse, women are disproportionately affected. The 2019-20 CSEW showed that over two-thirds (1.6 million) of those estimated to have experienced domestic abuse in the previous year were women, [footnote 9] and in 73% of domestic abuse crimes recorded by police in England and Wales in 2020-21, the victim and survivor was a woman. [footnote 10] In the year ending March 2021, we know that the majority of defendants (92%) in domestic abuse-related prosecutions were men. [footnote 11]

The data underscores the importance of tackling domestic abuse through the lens of violence against women and girls. Indeed, many forms of these crimes take place within the context of domestic abuse, including 36% of stalking and harassment cases and 19% of sexual offences. [footnote 12]

Yet these data do not include the number of child victims, with estimates suggesting between March 2017-19 that 7% of children aged 10 to 15 years were living in households where an adult reported experiencing domestic abuse in the previous year. [footnote 13] Witnessing domestic abuse as a child can have devastating consequences and is linked to later experience of, or perpetration of, abuse [footnote 14], [footnote 15].

With this in mind, and through examination of the available data, a wide-ranging review of the academic literature and the unprecedented over 180,000 responses to the Violence Against Women and Girls call for evidence, four major problems were identified that this plan will seek to address:

-

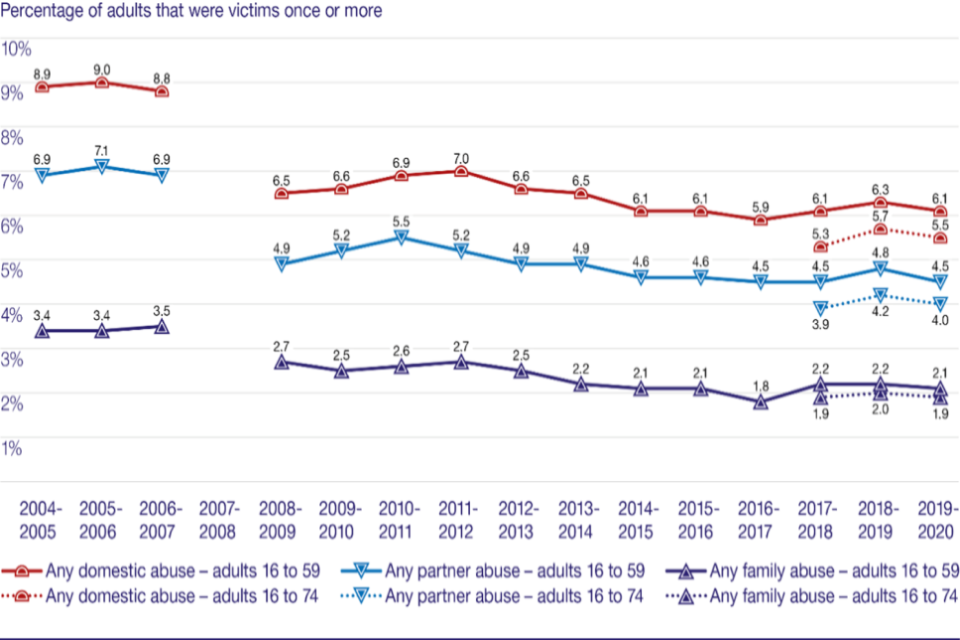

Problem One, the stubbornly high prevalence of domestic abuse. The 2019-20 CSEW estimated that 2.3 million adults aged 16 to 74 experienced domestic abuse in England and Wales [footnote 16] in the previous year. These numbers are intolerably high.

-

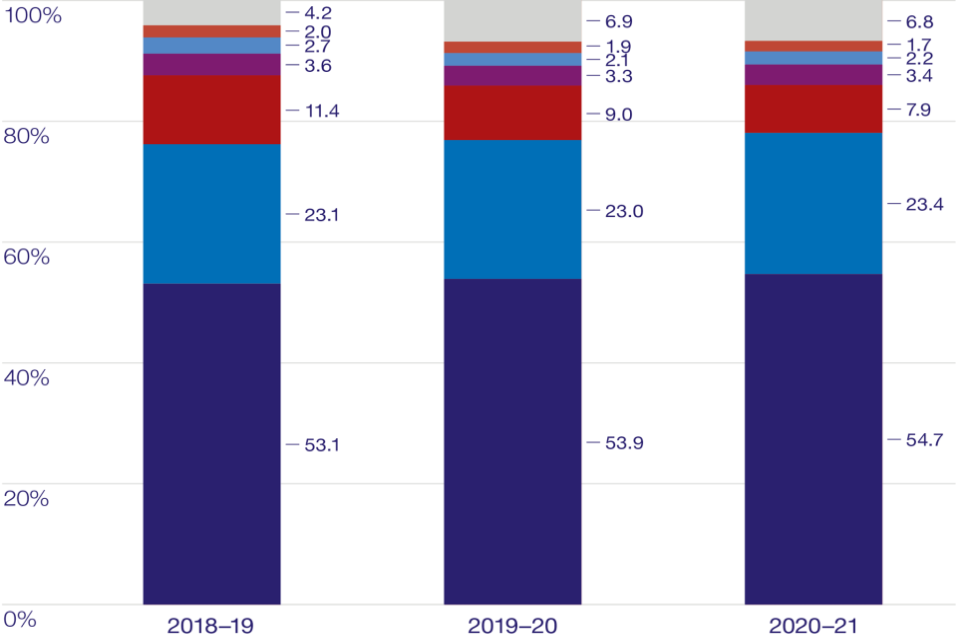

Problem Two, the significant loss of life caused by domestic abuse, with 114 domestic homicides recorded in 2020-21, of which 75 were female victims [footnote 17]. These homicides are at the most extreme end of a spectrum of harms that domestic abuse perpetrators inflict on their victims. In too many cases, these harms can also result in a victim taking their own life. Despite this, only 8% of recorded domestic abuse crimes were assigned an outcome of charged or summonsed in 2020-21. [footnote 18]

-

Problem Three, the negative health, emotional, economic, and social impact victims and survivors face during and following domestic abuse. Whilst more needs to be done to prevent domestic abuse, when it does occur, victims and survivors need a comprehensive package of support that is not just crisis-focused, and which takes the onus off them. They need greater access to support services, particularly specialist and ‘by and for’ services, support for the whole family, interventions which address financial and housing insecurity, more support in the workplace, and a better experience of the police, family courts, and the criminal justice system. (‘By and for’ services are specialist services that are led, designed, and delivered by and for the users and communities they aim to serve - for example victims and survivors from ethnic minority backgrounds, deaf and disabled victims and survivors, and LGBT victims and survivors).

-

Problem Four, an efficient system is necessary to allow us as a society to tackle domestic abuse. To improve the current system, three specific problems need to be addressed:

-

Identifying more domestic abuse cases. Currently there are gaps in public awareness of what constitutes domestic abuse, which hinders identification of cases. Increasing the ability of professionals to identify and respond to domestic abuse cases, particularly those more likely to regularly encounter them, should also contribute to identification of more cases. And the system needs to provide more opportunities for victims and survivors to disclose abuse by addressing the reasons why they do not do this. These include not knowing if or where support existed or how to access it.

-

Greater collaboration and coordination between and within organisations. Research has shown this is crucial to reducing the prevalence of domestic abuse. When organisations do not collaborate and coordinate internally and externally, opportunities are missed to identify victims and survivors and perpetrators sooner. This also helps to curtail abuse. Plus, sharing crucial information about victims and survivors can help tailor and improve the support they receive.

-

Improving our knowledge about domestic abuse through better data. There are gaps in the crime survey data collected [footnote 19] on domestic abuse. In general, more information needs to be made available from the data on the characteristics of victims and survivors, to ensure the impact of domestic abuse on specific groups can be studied and better understood. There is also more we can do to improve our knowledge, with two particular areas where more focus is needed: domestic homicides and suicides following domestic abuse. Any improvements in data on and knowledge of domestic abuse can be fed back into the system to tailor and refine the response to domestic abuse.

-

Our approach

This plan is a call to the whole of society to tackle domestic abuse. These crimes are everyone’s business, as is the business of addressing them. We must all play a role. We need all parts of national and local government, charities, the private sector, and individuals in their own communities to act. This plan seeks to encourage and facilitate the necessary coordination to achieve this.

Our approach is to be practical, not prescriptive. This plan commits to implement the measures that are most appropriate for the problems they aim to solve, without being fixed to one particular method. The complexity of domestic abuse and variety of forms it takes demands such flexibility in our response.

The plan is closely aligned with the recently published Tackling Violence Against Women and Girls Strategy. Domestic abuse is one form of violence against women and girls, however many of these crimes can happen in the context of domestic abuse. For example, we know that a large proportion of rapes occur in intimate partner relationships and that most cases of ‘honour’-based abuse occur in a domestic abuse context. The documents make complementary commitments and will share an integrated governance framework overseen by the government’s Violence Against Women and Girls Inter-Ministerial Group, chaired by the Home Secretary.

Both will be supported by a revised national statement of expectations, which provides clear and consistent guidance for local areas on how to commission support services for victims and survivors of all forms of violence against women and girls.

We have also refreshed our Supporting Male Victims document, in recognition of the fact that men and boys are affected by crimes such as domestic abuse, and require a nuanced, tailored response. However, our approach speaks to all victims and survivors of domestic abuse and our plan will help and support all victims and survivors.

This plan used the Violence Against Women and Girls call for evidence as a key data source. It received an unprecedented total of over 180,000 responses and comprised of four elements:

- a public-facing survey, as well as a nationally representative survey to ensure a fair representation of views from across society *

- a victim and survivor survey to better understand lived experiences of people accessing support and the criminal justice system, distributed via specialist support organisations

- 16 focus groups with a range of expert organisations and professionals to discuss specific crime types, including domestic abuse, as well as broader issues

- written submissions from a wide range of expert respondents which provided information on the scope, scale, and prevalence of domestic abuse, prevention, support available, perpetrator management and more

* Quotas were set on age, gender, and region, with weighting applied on these variables to reflect national profiles. Note: the respondents to the public-facing survey were more likely to be female, LGBT+, of no reported religion, and victims and survivors of violence against women and girls offences than the wider population, therefore their views will differ from the views of the wider population.

The call for evidence ran in two phases. Phase One ran between 10 December 2020 and 19 February 2021. In Phase Two, the public survey was reopened by the Home Secretary between 12 March and 26 March 2021.

The call for evidence was open to people aged 16 or over across England and Wales. Respondents tended to be female and aged between 16 and 34. We heard from a wide range of people across the country, including from different ethnicities, ages, sexes, and sexual orientations. A number of these respondents, or their friends, family, or colleagues, had been directly affected by domestic abuse. For this plan, we carefully filtered the responses to the victim and survivor survey to generate data specifically from victims and survivors of domestic abuse.

Only the data from the call for evidence that met the following criteria were used to inform this plan:

- A domestic abuse or specialist organisation supported the victim and survivor to submit a survey response

- An independent domestic violence adviser (IDVA) supported the victim and survivor or

- Domestic abuse was specifically mentioned in the open text questions.

We have included anonymised quotes from respondents to the call for evidence throughout this document. This reflects its significant influence on the plan, particularly the voices of victims and survivors.

The elements of this plan which relate to crime, policing, and justice apply to both England and Wales. The elements relating to health, social care, and education are devolved to Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland, and therefore apply to England only. The Welsh Government has been engaged throughout the development of the plan.

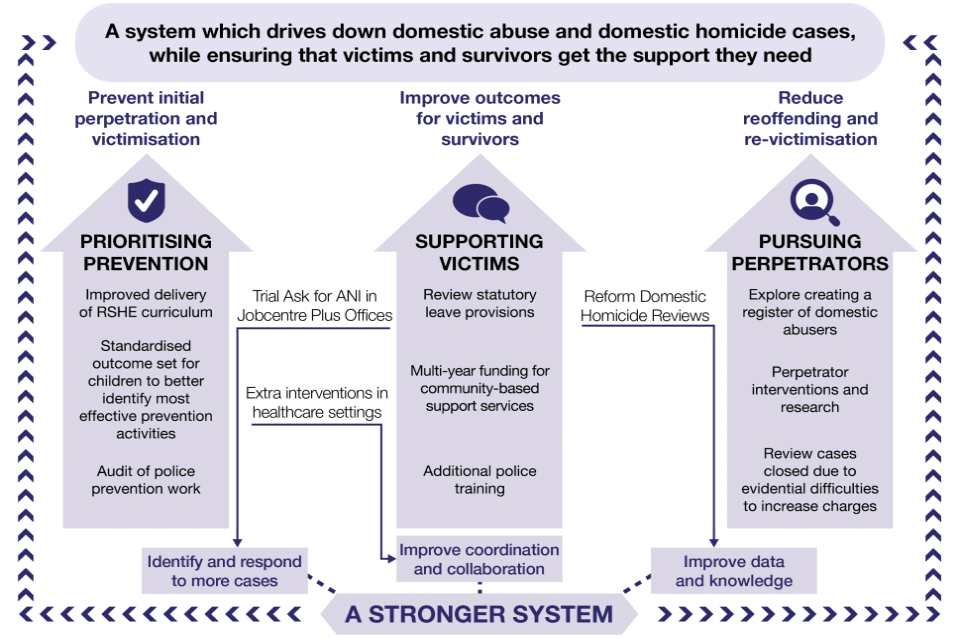

Graphic of system which drives down domestic abuse by prioritising prevention, supporting victims and pursuing perpetrators

Executive summary

Prioritising prevention

Objective

Reduce the amount of domestic abuse, domestic homicide, and suicides linked to domestic abuse, by stopping people from becoming perpetrators and victims to begin with.

Rationale

Domestic abuse devastates the lives of millions. We know its scale is vast (Problem One), and we know its consequences, which often include loss of life, are intolerable (Problem Two). We know there are several factors which can increase the likelihood of someone becoming an abuser. There are interventions to address this, although in many cases, we do not yet know the most effective at mitigating those risk factors. Equally, we do not know the extent to which these risk factors cause an increased likelihood of domestic abuse rather than just being associated with it.

Therefore, to drive down domestic abuse and domestic homicide by preventing them from ever happening in the first place, we need actions which not only tackle those risk factors but interventions to help us better understand them. We want a more targeted approach to see domestic abuse and domestic homicide reduce by more than it ever has before.

Metrics

These are shared with those in the pursuing perpetrators pillar.

-

A reduction in the prevalence of domestic abuse. Source: Crime Survey for England and Wales (Office for National Statistics).

-

A reduction in the number of domestic homicides. Source: Homicide Index (Home Office).

Key commitments

-

Being of a younger age and low levels of education are two significant risk factors. To address them, the Department for Education will provide support to teachers delivering the recently refreshed Relationships, Sex and Health Education (RSHE) curriculum. Experts, including domestic abuse organisations, will together feed into what this support looks like. Ensuring children know about healthy relationships through the RSHE curriculum at a young age, as well as challenging poor attitudes towards relationship behaviours, will help to prevent cases of domestic abuse later in life.

-

The Home Office is supporting the development of methods to comparably measure the effectiveness of different interventions which support children experiencing domestic abuse. These measures will consider key outcomes for children and young people who have experienced domestic abuse, such as the impact on relationships, wellbeing, and perceptions of safety and freedom. This will improve our understanding of what works to support and improve outcomes for children who experience domestic abuse.

-

The Home Office will work with the National Police Chiefs’ Council to identify and audit police forces which record the highest rates of domestic homicide and serious domestic abuse crimes. The Home Office will work with these forces to improve their domestic abuse metrics and identify challenges they are facing. The aim is to prevent serious incidents, including domestic homicides, from ever occurring.

Supporting victims

Objective

Help all victims and survivors who have escaped from domestic abuse feel that they can get back to life as normal, with support for their health, emotional, economic, and social needs.

Rationale

We need to improve health, emotional, economic, and social outcomes for domestic abuse victims and survivors (Problem Three). We know there are many forms of support which can do this, particularly support services and professional support. However, these must be tailored to each and every individual.

That is why this plan sets out a range of support to ensure that every victim and survivor can get the support they need. We will also monitor their needs and reflect changes in our policy. This individualised approach will help to take the onus off victims and survivors by ensuring support is tailored to them, no matter how complex their needs.

Metrics

-

An increase in spending on support services, including on ‘by and for’ services, for domestic abuse victims and survivors. Source: Home Office and Ministry of Justice spending on services that provide support for domestic abuse victims and survivors, and Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities spending on services that provide support for domestic abuse victims and survivors within safe accommodation.

-

Support services are crucial in helping victims and survivors of domestic abuse recover [footnote 20], [footnote 21]. However, we need to ensure they all provide a consistently good service across the country. The upcoming Victims Funding Strategy will propose a set of core metrics to be used across support services to establish what good looks like. It will also improve how the government monitors its impact.

-

An increase in reporting of domestic abuse to the police*. Source: Crime Survey for England and Wales - Percentage of victims and survivors reporting partner abuse to the police (Office for National Statistics) and Domestic abuse-flagged police recorded crimes (Home Office).

* Domestic abuse is an under-reported crime. The gap between police reports of domestic abuse and the number of domestic abuse victims and survivors estimated by the Crime Survey for England and Wales means there is a significant number of unidentified cases. Uncovering more of these cases could lead to earlier interventions which shorten the duration of domestic abuse (reducing prevalence), and lead to better outcomes for victims and survivors.

We have included further performance metrics in the delivery section of the document. These will track our progress in delivering this support to victims and survivors, and the impact they are having.

Key commitments

-

In order to understand whether more needs to be done to support domestic abuse victims and survivors to rebuild their lives, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy will review the current statutory leave provision for employees and consider if this does enough to support victims and survivors who are trying to escape domestic abuse. We will set out any next steps later this year.

-

In recognition of how important support services are, the Ministry of Justice will ringfence £47.1 over three for community-based services supporting victims and survivors of domestic abuse and sexual violence and provide £81 million for independent domestic violence advisers and independent sexual violence advisers. Both the Home Office and the Ministry of Justice will offer multi-year awards of funding to organisations supporting victims and survivors of domestic abuse. This will mean more survivors receive higher quality support services.

-

To help increase the confidence of victims and survivors in the police, encourage more people to report domestic abuse, and receive better treatment when they do come forward, the Home Office will provide up to £3.3 million to fund the rollout of Domestic Abuse Matters training to forces which have yet to deliver it, or do not have their own specific domestic abuse training.

-

As part of the Victims Funding Strategy, the Ministry of Justice will be looking at introducing national commissioning standards across all victim support services and DLUHC Quality Standards for support in safe accommodation. This will ensure that the commissioning of support in safe accommodation for domestic abuse victims and survivors and their children will be subject to the same standards as all victim support services.

Pursuing Perpetrators

Objective

Reduce the amount of people who are repeat offenders and make sure that those who commit this crime feel the full force of the law.

Rationale

We are clear that perpetrators are the ones who need to change their behaviour and stop offending. By relentlessly pursuing them we can make this happen. We can drive down the prevalence of domestic abuse (Problem One) and reduce the number of domestic homicides (Problem Two).

This involves better understanding and addressing the falling number of charges, prosecutions, and convictions so perpetrators are stopped and face justice. We need to improve risk assessments and expand and strengthen the measures we have to deal with abusers once risks are identified. And we need to deploy interventions and programmes which do not just stop perpetrators, but which change their behaviour in the long-term.

Metrics

- An increase in the number of charges for domestic abuse-flagged crimes. Source: Crime outcomes in England and Wales (Home Office) and Crown Prosecution Service data on the volume of charges (Crown Prosecution Service)

- A reduction in the prevalence of domestic abuse victims. Source: Crime Survey for England and Wales (Office for National Statistics).*

- A reduction in the number of domestic homicides. Source: Homicide Index (Home Office).*

*Shared with those in the prioritising prevention pillar.

Key commitments

-

To better understand and address the falling number of charges, the Home Office will accept recommendations made in reports by HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services (HMICFRS) to conduct a review of data on domestic abuse cases closed due to evidential difficulties. This is where cases are closed by the police due to the lack of evidence (Outcomes 15) or where the victim does not support police action (Outcome 16).

-

To manage the most harmful domestic abusers more robustly, the government is actively exploring creating a register of domestic abuse offenders. Additionally, the Ministry of Justice will increase tagging for those leaving custody, including around 3,500 individuals who are at risk of perpetrating domestic abuse.

-

To help the police assess the dangers posed by individual domestic abusers, the Home Office will allocate £6.7 million over the next three years to refine and pilot the rollout of a risk assessment tool. The Recency, Frequency, Gravity and Victimisation model has huge potential to enhance these risk assessments by identifying the most dangerous serial abusers.

-

To get perpetrators to change their behaviour and reduce reoffending, the Home Office will invest £75 million over three years into tackling domestic abusers. This includes funding for perpetrator interventions, with multi-year agreements where appropriate, evaluation, and further research. This will include funding for interventions that directly address domestic abusers’ behaviours. The Home Office will also develop a set of national principles and standards to promote a consistent and safe approach by these programmes.

A stronger system

Objective

Improve the systems and processes that underpin the response to domestic abuse across society.

There are three specific ways in which the plan aims to improve these systems and processes:

- more domestic abuse cases are identified and responded to appropriately

- improve collaboration and coordination between and within organisations

- improve data on, and knowledge of, domestic abuse

Rationale

To make sure we can be at our strongest when tackling domestic abuse, we need a robust system that works across the whole of society. This is important in enabling us to effectively deliver on our first three objectives.

We will make it easier for more victims and survivors to report domestic abuse, as well as making sure that professionals who regularly encounter domestic abuse can better identify and refer victims and survivors appropriately (Problem Four A). This is critical to them accessing the support they need. Improved communication between Departments, public service organisations and wider society (Problem Four B) will contribute to a reduction in the prevalence of domestic abuse. And addressing gaps in data and knowledge, including on domestic homicide and suicides following domestic abuse (Problem Four C), will mean we can tailor future interventions so that they are most effective.

Metrics

We will be able to judge if we have a better system if the other three objectives are being delivered. Outputs of measures committed to in this pillar will be monitored closely to ensure our system delivers an effective response to domestic abuse.

Key commitments

-

We want to make it easier for people to ask for help and identify more cases. The Home Office will work with the Department for Work and Pensions to trial and, if it is successful, consider a national rollout of the Ask for ANI codeword scheme across Jobcentre Plus offices. The scheme currently provides a simple and discreet way for domestic abuse victims and survivors to signal that they need immediate help using a codeword in participating pharmacies.

-

We know that providing doctors, nurses, and midwives with the skills to better identify and refer domestic abuse cases will help to better join up the response across society. The Home Office will therefore invest up to £7.5 million over three years to implement those structures within healthcare settings.

-

The Department of Health and Social Care will publish their Women’s Health Strategy in Spring 2022, which will address some of the barriers that victims and survivors of domestic abuse face when interacting with important health services, and help to ensure that our healthcare professionals are appropriately equipped to support and refer those suffering trauma from abuse.

-

There is much more that needs to be done to improve our data on domestic homicides and suicides following domestic abuse. To address this, the Home Office will reform the Domestic Homicide Review (DHR) process. This will include working with the National Police Chiefs’ Council to identify best practice in referring suicides that followed domestic abuse for a DHR and launching an online database in 2022 of all DHRs, in which £1.3 million has been invested.

Prioritising prevention

Our objective: Reduce the amount of domestic abuse, domestic homicide, and suicides linked to domestic abuse, by stopping people from becoming perpetrators and victims to begin with.

If we are to reduce the prevalence of domestic abuse and domestic homicide, robust action is needed to prevent it from happening in the first place. We can do this by better understanding what factors can lead to a higher risk of someone becoming a domestic abuser.

We are looking at whether these circumstances actually cause domestic abuse or are just associated with a higher likelihood. But we must still act now and directly address those risk factors to have the biggest possible chance of preventing cases of domestic abuse and domestic homicide.

What we know, do not know, and need to do

Anyone can be a victim and survivor or perpetrator of domestic abuse. In this pillar, we set out the risk factors which we know are associated with an increased likelihood of domestic abuse perpetration and victimisation.

So much more needs to be done to understand what lies beneath behaviours of perpetrators.

Call for evidence, victim and survivor survey.

We know that whilst younger males are more likely to perpetrate domestic abuse, there are several other factors influencing whether someone might commit these crimes. We know there is a complex relationship between domestic abuse and, for example, a lower level of education, having a criminal history, a disadvantaged background, and whether those around them condone violence and gender inequality.

We know experience of child abuse is a consistent predictor of domestic abuse for both perpetrators and victims. The relationship between domestic abuse perpetration and substance misuse is even more complex, so too is the relationship between domestic abuse perpetration and mental health issues. It is important to highlight that simply because an individual is exposed to any one of these risk factors, it does not necessarily mean they will experience or carry out domestic abuse.

Given we do not know what can cause domestic abuse, or what may just be an associated risk, it makes it difficult to precisely identify what will achieve the greatest change. To address this, we need to introduce a range of interventions and monitor their effectiveness.

While we await more data, we still need to deliver interventions which address the risk factors outlined in Annex B. Often, the risk factors for domestic abuse are the same as those for other crime types. [footnote 22] This means we can aim to drive down multiple types of crime at once.

What we are already doing and what more we will do

Identifying preventative measures

We must continue to understand the most effective ways of preventing all forms of violence against women and girls, including domestic abuse. That is why the Home Office has committed to invest £3 million in 2022-23 towards programmes that improve our understanding on what works to prevent violence against women and girls.

To respond to the urgent need to scale-up efforts to prevent violence against women and girls crimes, including domestic abuse, the United Kingdom is investing in What Works to Prevent Violence: Impact at Scale. This will be the first global effort to systematically scale-up violence prevention efforts and evaluate their impact. Through this, we hope to learn how to reduce the prevalence of domestic abuse, preventing first occurrence, and reducing reoffending and re-victimisation at scale.

Taking preventative measures

Increasing awareness

In the Tackling Violence Against Women and Girls Strategy, the Home Office committed to roll out a multi-year communications campaign focused on creating behaviour change. The campaign, called ‘Enough’, launched in March 2022, with its first phase focusing on challenging perpetrators and encouraging members of the public to take action if they witness abuse. Television adverts, outdoor posters, radio, digital audio, partnerships, and social media content all aimed to increase awareness of challenging perpetrators and signposted to a campaign website with more information and support for victims and survivors. Campaign materials have featured in transport settings including bus stops, roadsides, train stations, the London Underground and in pubs, bars, and men’s toilets.

The government is also committed to protecting people from conversion therapy practices, which can constitute a form of domestic abuse, and preventing it from happening in the first place. The Home Office will work with the Equality Hub to make clear how some so-called ‘conversion therapy’ practices may constitute domestic abuse, such as family members coercing a relative into undertaking it. In addition, the Home Office is committed to supporting the Equality Hub in taking appropriate action to end the practice, and support victims and survivors.

Teaching young people

Teaching young people what is unacceptable and abusive behaviour in relationships is essential… Teaching young people about what is abusive will have a huge impact on lowering abuse in the future.

Call for evidence, public survey.

It is important we have measures that target younger age groups. These measures can often align with addressing low levels of education. The need to do so was raised in all components of the call for evidence. Respondents felt that children and young adults need to be educated about:

- healthy relationships

- consent

- what behaviours are not acceptable, particularly regarding coercive control in a relationship

- the relevant laws

- how to access help if needed

The Relationships, Sex and Health Education (RSHE) curriculum will play a key part in improving children’s education to ensure they understand healthy relationships. That is why, since September 2020, the Department for Education made relationships education mandatory in all primary schools, relationships and sex education mandatory in all secondary schools, and health education mandatory in all state funded schools.

Pupils need to be taught about the concepts and laws relating to a range of areas including consent, coercion, and domestic abuse. Boys and young men should understand what is not acceptable within relationships and girls and young women need to know what not to accept. To help teachers to deliver the RSHE curriculum, the Department for Education will work with experts to develop a package of support for teachers. This will include guidance, expert-led webinars, and regional events to facilitate the sharing of good practice and effective networking. The Department for Education will continue to build a programme of support that meets teachers’ needs.

There is a link between holding views that support gender inequality and condone violence and domestic abuse. [footnote 23] We must prevent these attitudes from developing at a young age. Therefore, it is vital that trusted adults, including parents and teachers, take steps to ensure children and young people respect each other. This means that harmful attitudes and behaviours cannot be left unchallenged and must not be tolerated. Schools and colleges can play a vital role in fostering a positive culture in which healthy behaviours are understood and encouraged, and harmful attitudes challenged. The Respectful School Communities Toolkit supports school leaders to create a whole-school approach which promotes respect and discipline.

The Keeping Children Safe in Education (KCSIE) guidance has been strengthened following a full consultation process last year and the findings from the Ofsted Review of Sexual Abuse in Schools and Colleges. The guidance now better supports schools and colleges to prevent, identify and respond appropriately to abuse where it is reported. It sets out that downplaying certain behaviours, for example dismissing sexual harassment as “just banter”, “part of growing up” or “boys being boys”, can lead to a culture of unacceptable behaviours. It can create an unsafe environment for children and, in some cases, a culture that normalises domestic abuse. The guidance sets out that schools and colleges are expected to have clear processes to support victims and survivors and any other children affected by child-on-child abuse. The KCSIE guidance remains under constant review.

Outcomes for children

It is crucial that we maximise our knowledge on what works to support and improve outcomes for children experiencing domestic abuse. This can be particularly challenging given difficulties in comparing studies of different interventions in this area, because each study measures success in different ways.

Children living in a home where there is domestic abuse/control are traumatised by what they are forced to witness. Government must put in place help and counselling for these children.

Call for evidence, nationally representative survey.

Therefore, the Home Office is supporting the development of a set of tools to measure the effectiveness of interventions that support children experiencing domestic abuse. This work is being undertaken by a group led by University College London. This group is agreeing a set of common outcomes which could be measured in evaluations of child and family interventions which address domestic abuse. The next stage is to agree appropriate measurement tools to assess these outcomes. To facilitate this, the Home Office is funding research to investigate the types of measures currently being used.

It is vital that children and younger age groups are protected from content and activity online that can cause them significant physical and psychological harm; 80% of 12-15-year-old internet users have had at least one potentially harmful online experience in the last 12 months. [footnote 24] The Online Safety Bill will require companies to protect all children from the most harmful content and activity on the internet and ensure that wider protections are age appropriate. It will also require websites that publish or host pornographic content to put in place measures which prevent children from accessing such material.

Child, early and forced marriage is a form of violence against women and girls, which denies women and girls their rights, freedom, and ability to make choices that affect their lives. Delaying marriage reduces the risk of domestic abuse, amongst other benefits including reducing adolescent pregnancy, preventing maternal deaths, giving people better career opportunities, and preventing school dropouts. [footnote 25]

Given this, the government has supported the Marriage and Civil Partnership (Minimum Age) Bill, which would tackle child marriage by raising the age of marriage and civil partnership in England and Wales from 16 to 18. It will also expand the offence of forced marriage to provide that it is always illegal to arrange the marriage (legally binding or otherwise) of an under-18, even when coercion is not used. In addition, the government continues to provide support for victims and survivors, and those at risk of forced marriage through the joint Home Office and Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office Forced Marriage Unit’s helpline.

Child-to-parent abuse

Tackling behaviours early on is key to preventing future offending, as these learned behaviours can act as a steppingstone towards perpetrating abuse in later life. The Home Office will publish updated guidance for frontline practitioners on child-to-parent abuse (CPA) this year, working with frontline practitioners include those working in the police, health, education, and social care, to name just a few. The Home Office will also work with stakeholders to reach an agreed definition and terminology for this type of behaviour. This will underpin policy development on the response to CPA, and comprehensive guidance to support practitioners and service commissioners.

Role of the police

For those in intimate relationships or those starting out in new relationships who have concerns about their partner’s behaviour, the government introduced the Domestic Violence Disclosure Scheme (DVDS), also known as Clare’s Law, which came into force in England and Wales in 2014. The DVDS sets out procedures that can be used by the police to disclose information about previous violent or abusive offending, including emotional abuse, controlling or coercive behaviour, or economic abuse by an individual, where this may help protect their partner or ex-partner. These disclosures could be critical in safeguarding a victim and survivor or potential victim.

Under Section 77 of the Domestic Abuse Act 2021, we will be placing the guidance for the DVDS on a statutory footing. This will help ensure a uniform and consistent implementation of the Scheme by the police. The Home Office is reviewing and revising the existing guidance, including considering the timescales for disclosure and promoting tools which allow applications to be made online. The revised guidance will go out for public consultation shortly.

Multi-agency working is crucial to preventing domestic homicides, and the police have an important role to play. The Domestic Homicide Project found that 52% of domestic homicide suspects between March 2020 and 2021 were previously known to police as a suspect for any prior offending. Of those, 82% were known to police for domestic abuse. This shows that the police have an important role to play in preventing these tragedies.

That is why the Home Office will collaborate with the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) Domestic Abuse Lead, Assistant Commissioner Louisa Rolfe, on a new domestic abuse policing and domestic homicide prevention pilot. The pilot will identify forces that have relatively high levels of domestic homicide and serious domestic abuse incidents. These forces will be audited to ensure they are doing everything they can to prevent domestic abusers from causing harm. This will involve data collection, work to improve their domestic abuse metrics, and help to identify challenges they are facing in domestic abuse policing, all with the aim of preventing domestic homicides.

Supporting victims

Our objective: Help all victims and survivors who have escaped from domestic abuse feel that they can get back to life as normal with support for their health, emotional, economic, and social needs.

We must first and foremost seek to prevent domestic abuse from happening. But when it does occur, we need to do everything in our power to mitigate its impact, to help victims and survivors recover and to encourage them to feel that they can get back to life as normal. We will deliver a wide-ranging package of support with measures which we know are effective. One that is not just crisis-focussed, and which takes the onus off victims and survivors. We will also seek to better understand how the support provided can be improved.

What we know, do not know, and need to do

Support services were really important as they validated my feelings and supported me and empowered me to take action and leave my partner.

Call for evidence, victim and survivor survey.

We know there is a wide variety of support available to victims and survivors. In many cases, it is clear which forms of support deliver improved outcomes. However, we do not know which measures will work best for individuals. The package of support required by each person will be unique to them and their circumstances. Additionally, we know this can be an underreported crime, and our experience of what works is based on victims and survivors who have been reached and received help, not those whose cases remain unidentified. Domestic abuse remains too often hidden from view.

Therefore, this plan cannot be prescriptive in the support offered to victims and survivors. Instead, it needs to deliver a holistic package of support, with a wide variety of interventions that will enable victims and survivors to access the support most suited to their needs.

The call for evidence provided data on the forms of professional support which generated the greatest satisfaction among victims and survivors (Figure 1). Victims and survivors were most satisfied with independent domestic violence advisers (85%), support services (81%), and helplines (78%). Satisfaction was also high for voluntary sector psychologists and independent sexual violence advisers (ISVAS, 67% for both).

Figure 1 – Call for evidence victim and survivor survey responses for satisfaction with professional support received, 2020-21

| Satisfaction with professional support | percentage |

|---|---|

| Independent domestic violence adviser | 85% |

| Support service eg rape crisis centre or refuge | 81% |

| Specialist service helpline | 78% |

| Trained counsellor / psychologist (voluntary sector) | 67% |

| Independent sexual violence adviser | 67% |

| Sexual assault referral centre | 63% |

| via support service website eg webchat | 59% |

| Medical professional eg GP, nurse | 58% |

| Trained counsellor / psychologist (NHS) | 58% |

| Social services (children) | 41% |

| Social services (adult) | 30% |

Source: Domestic abuse-specific Violence Against Women and Girls call for evidence responses

There are five broad categories of support which will deliver improved outcomes:

- support services and professional support

- support for the whole family

- economic and housing support

- support in the workplace

- support through the police, family courts and criminal justice system

This plan needs to set out how tailored, community-based, and accommodation-based services will be provided – services that are accessible and which generate the greatest satisfaction from victims and survivors. We need to ensure a whole family approach that provides support for all family members is available. Responses to the call for evidence made clear that economic abuse can leave victims and survivors economically dependent on abusers, creating financial insecurity that makes it harder for them to access safety. We know that employers need more robust responses and protocols after disclosures of domestic abuse.

Figure 2 – Why the victim did not tell the police about the partner abuse experienced in the last year, England and Wales, year ending March 2018

| Why the victim did not tell the police | percentage |

|---|---|

| Too trivial / not worth reporting | 46% |

| Private family matter / not police business | 40% |

| Didn’t think they could help | 34% |

| Embarrassment | 27% |

| Didn’t want the person who did it to be punished | 17% |

| Some other reason | 16% |

| Didn’t think the police would do anything about it | 15% |

| Thought it would be humiliating | 12% |

| Feared more violence as a result of involving police | 11% |

| Didn’t think they would believe me | 8% |

| Didn’t think the police would be sympathetic | 8% |

| Didn’t want to go to court | 7% |

| Dislike / fear of the police | 2% |

| Police did not come when called | 2% |

Source: Office for National Statistics

Only a small proportion of victims and survivors report domestic abuse to the police. The Crime Survey England and Wales (CSEW) shows that only 17% of victims and survivors whose partner abuses them report it to the police. [footnote 26] The most frequently cited reason was thinking it was too trivial or not worth reporting (46%). Another reason was thinking the police couldn’t help (34%).

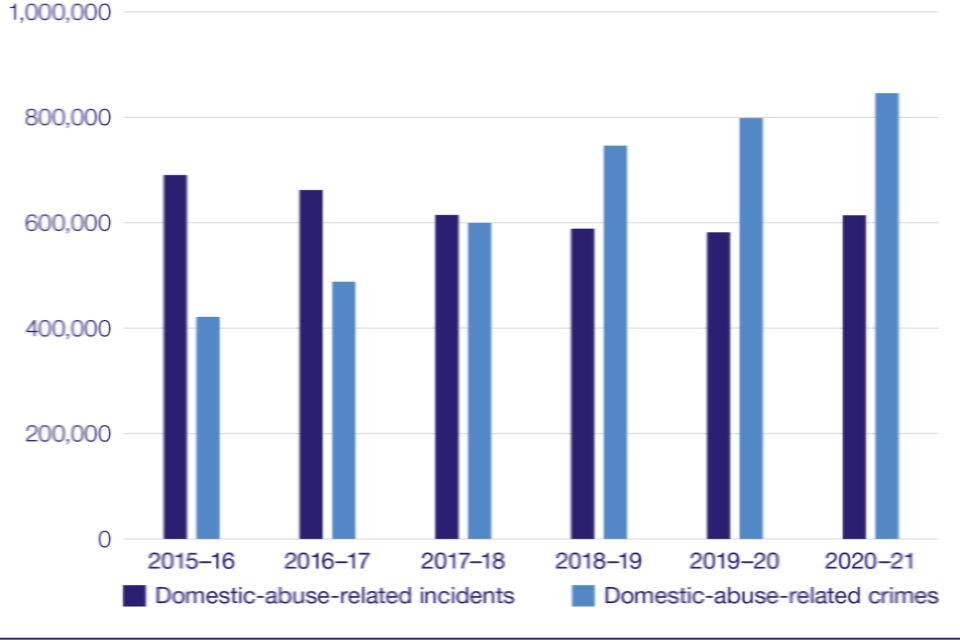

We need to increase reporting to the police of domestic abuse-related incidents and recorded crimes. This will mean more victims and survivors, if they choose to, can access support and protection from the police and the wider criminal justice system. Figure 3 shows a year-on-year increase in police recorded domestic abuse-related crime (excluding fraud) in England and Wales between 2015 to 2021. Though the gap between prevalence and police recording is decreasing due to improvements in how police record domestic abuse, this is still below the 2.3 million estimated by the CSEW over the same period.

Figure 3 – Volumes of domestic abuse-related incidents and crimes recorded by police in England and Wales, year ending March 2016 to year ending March 2021

Volumes of domestic abuse-related incidents and crimes recorded by police in England and Wales, year ending March 2016 to year ending March 2021. Incidents fell from 700,000 to around 600,000. crimes rose from 400,000 to around 850,000

Source: Office for National Statistics

What we are already doing and what more we will do

All the measures we take to support victims and survivors must have victims and survivors at their core. We need to ensure their voices inform policy and that we hear from those across the whole of society, particularly as we uncover a greater number of cases. To do this, we will provide additional funding to the Domestic Abuse Commissioner to establish a mechanism for their input into policy development and implementation.

The Domestic Abuse Commissioner is uniquely placed to have meaningful conversations with victims, which can feed directly into policy work across government. We will also continue to engage with charities and organisations who support victims and survivors.

A range of support

Support services and professional support

Advocacy and therapeutic interventions can have positive effects on victims’ and survivors’ wellbeing, and the most effective methods are tailored to individuals’ needs. [footnote 27] In 2021-22, the Ministry of Justice provided £150.5 million for victim, survivor and witness support services. This included £51 million to increase support for rape and domestic abuse victims and survivors, building on the emergency funding from the last financial year to help domestic abuse and sexual violence services meet the demand driven by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The government also awarded £25 million in May 2020 to help domestic abuse and specialist rape organisations during the COVID-19 pandemic. This helped organisations to recruit more staff and adapt to remote counselling methods during the COVID-19 pandemic. A further £2 million was provided to ensure that helplines and online services continued to be easily accessible.

The Ministry of Justice also conducted a wider consultation on the upcoming Victims’ Bill which looked at the provision of community-based support and a statutory underpinning for the independent sexual violence advocate (ISVA) and independent domestic violence adviser (IDVA) roles.

The Ministry of Justice is increasing funding for victim and witness support services, to £185 million by 2024-25. This includes funding to increase the number of independent sexual violence and domestic abuse advisers to over 1,000 and funding to implement the new national support for victims of rape and sexual violence which will be available 24/7.

Of this, £147 million has been committed to per annum between 2022-23 and 2024-25. This includes a minimum of £81 million over three years to fund 700 ISVA and IDVA roles, with additional funding to be confirmed later this year. There will be a ringfence of £15.7 million per annum to be spent on community-based services supporting victims and survivors of domestic abuse and sexual violence. The £147 million includes funding for Police and Crime Commissioners to commission a range of support services for victims of all crime, based on their assessment of local demand. Police and crime commissioners will be required to pass the multi-year commitment on to the local services they commission, to ensure frontline service providers receive the full benefits.

The Home Office is also planning to double funding for survivors of sexual violence and the National Domestic Abuse Helpline by 2024-25, and further increase funding for all the national helplines it supports.

Multi-year funding by the Home Office and Ministry of Justice will offer more stability and consistency for victims as services will not be dependent on yearly grants. Investing in these services will help to ensure that high quality support is available to victims when needed.

Responses to the call for evidence emphasised a troubling ‘postcode lottery’ when it came to the availability of support services. To address this, we will use the results of the Domestic Abuse Commissioner’s mapping exercise of support services across the country to identify gaps and better target funding to local services.

The call for evidence also highlighted that services are routinely commissioned in silos which means support services cannot properly support people with complex needs. To help address this, we are publishing refreshed versions of the National Statement of Expectations and Commissioning Toolkit. They will ensure there are consistent processes for commissioning services across the country. The updated documents include further information on how local areas should work in partnership with specialist ‘by and for’ organisations. This will build on the guidance issued in relation to provision of support services by local authorities in safe accommodation. These documents will make sure every victim and survivor across the country can receive help.

Support in safe accommodation

To ensure sufficient provision of support services in safe accommodation, as well as the community, the Domestic Abuse Act 2021 placed a new duty on Tier One local authorities to assess the need, and commission support for all victims and survivors of domestic abuse, including children, within safe accommodation. In 2021-22, this was supported by £125 million of funding from the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC). The new duty came into force on 1 October 2021, accompanied by Statutory Guidance to support local authorities in implementing it. Since then, DLUHC has confirmed a further £125 million will be provided in 2022-23 to support delivery of the duty.

To go even further, as part of the Victims Funding Strategy, the Ministry of Justice will be looking at introducing national commissioning standards across all victim support services and DLUHC Quality Standards for support in safe accommodation. This will ensure that safe accommodation for victims will be subject to the same standards as all victim support services.

Not all vacancies in safe accommodation are available to every victim and survivor due to the accommodation not being able to offer the specialist support that may be required by each person. Sadly, some victims and survivors will not be able to access safe accommodation, even if there are vacancies. By providing funding for support services in safe accommodation, it should make more of those vacancies available to a greater number of victims and survivors. This increases the numbers supported in safe accommodation and decreases the numbers turned away.

To ensure the new duty works for all victims and survivors, a Ministerial-led National Expert Steering Group has been established to oversee the successful provision and delivery of the new duties across the country, which will meet at least twice a year. The group is co-chaired by the Minister for Rough Sleeping and Housing and the Domestic Abuse Commissioner. It will review any operational challenges on the ground, looking at possible causes and solutions.

Tailored support

I would never [have] been able to overcome the abuse without specialised support… We need more services and investment as it took me days of trying to call all the time to get through.

Call for evidence, victim and survivor survey.

We know the importance of support that is tailored to the specific needs of different groups of victims and survivors. In 2021-22, the Home Office provided Sign Health with just over £145,000 to support deaf victims and survivors of domestic abuse. More widely, the government has also backed the British Sign Language (BSL) Bill which if passed, would require the government to produce guidance about the promotion and facilitation of the use of BSL.

The Home Office provided Victim Support with £125,000 in 2021-22, to help build the capacity of IDVAs to support disabled victims and survivors and create a network of Multi-Agency Risk Assessment Conference disability champions. We have also provided just over £200,000 to the organisation Hourglass to enhance their helpline, provide casework support, and train specialist IDVAs to support older victims and survivors.

In 2021-22, the Home Office provided £1.5 million to launch the Support for Migrant Victims Scheme to further support this group. This was in recognition of the additional barriers those with insecure immigration status can face in seeking support. Doing this helps to remove some of the control abusers exert over victims. Anyone who has suffered domestic abuse should be treated as a victim and survivor first and foremost, regardless of their immigration status.

The 12-month pilot scheme is being run by Southall Black Sisters and their delivery partners. It provides accommodation and wrap-around support to migrant victims and survivors of domestic abuse. An independent evaluator, Behavioural Insights Ltd, has also been appointed to assess the pilot, with a final report to be published in Summer 2022. We will take on board the evaluation findings to inform future decisions. In the interim, we will provide £1.4 million in 2022-23 to continue to fund support for migrant victims and survivors. The Scheme will help the government paint an accurate picture of what support migrant victims and survivors of domestic abuse need.

For male victims and survivors, one example of the services funded is the Men’s Advice Line, run by Respect, which has received just under £168,000 per year. In 2020-21, the helpline was provided with a further £151,000 to bolster services in response to COVID-19 pandemic pressures and in 2021-22, a further uplift of £64,500.

We need tailored, ‘by and for’ support for women with particular needs (Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic women, disabled women, women with multiple layers of need, LGBT victims).

Call for evidence, public survey.

‘By and for’ support

In 2021-22, the Home Office committed to provide an additional £1.5 million in funding to increase provision of ‘by and for’ and specialist services for victims and survivors of domestic abuse, and all forms of violence against women and girls. This was in recognition of the benefits victims and survivors report from accessing such services.

We know that specialist and ‘by and for’ organisations face challenges in navigating local commissioning processes. To begin addressing this, the statutory guidance to support implementation of the duty on local authorities to commission support services in safe accommodation sets out that, where possible, this should be conducted on a multi-year basis. This means that smaller organisations can offer a stable service to victims and survivors. We also want to ensure smaller voluntary organisations are not left out and are clear that local authorities should seek specialist advice to ensure the particular needs of specific groups of victims and survivors are considered.

Support for the whole family

We know that all family members affected by domestic abuse need to be supported. This kind of whole-family approach is already being delivered through the following schemes:

-

The government has committed over £39 million to champion family hubs and, at the 2021 Budget, announced a further £82 million to create a network of family hubs in England. Family hubs are a way of joining up locally to improve access to services for children of all ages, the connections between families, professionals, services, and providers, and putting relationships at the heart of family help. Services could start to include support for survivors of domestic abuse. How services are delivered varies from place to place, but these principles are key to the family hub model.

-

At the 2021 Spending Review, the Supporting Families programme received a £200 million uplift in funding, taking the total planned investment to £695 million until 2024-25, representing a 40% real-terms uplift in funding. This will enable the programme to secure better life outcomes for up to 300,000 more families by 2025 and ensure that many more benefit from improved services. The Supporting Families programme is designed to improve public services for families by promoting and funding integrated support. This ensures families get access to early, coordinated help to address multiple and complex needs, including domestic abuse. The programme encourages domestic abuse to be viewed in the context of other problems affecting the family, such as youth crime, substance misuse, truancy, or mental health issues, so that all problems are addressed holistically and not in isolation.

-

By taking a whole-family approach, we can address the devastating impact that experiencing domestic abuse can have on the health and development of children. That is why the Domestic Abuse Act 2021 recognises children who see, hear or experience the effects of domestic abuse as victims. And it is also why in 2021-22, the Home Office has provided over £3 million, through the Children Affected by Domestic Abuse (CADA) Fund, to organisations providing specialist support within the community to children who are experiencing domestic abuse. The Home Office will increase funding so that the CADA fund receives £4.1 million in 2022-23.

-

Concerns about obtaining a school placement for children may be a barrier to victims and survivors escaping domestic abuse mid-way through the school year, and seeking refuge or safe accommodation, particularly if it means leaving the area. However, parents can apply for a place for their child at any school at any time; and where there are places available, the child must be admitted. In 2021, following a consultation the Department for Education revised the School Admissions Code to improve the in-year admissions process and minimise gaps in children’s education. There are proposals to include children living in a refuge or relevant accommodation as an eligible category for placement via local fair access protocols.

(For a full definition of ‘relevant accommodation’ included under the Fair Access Protocol, see Section A3 of Delivery of support to victims of domestic abuse in domestic abuse safe accommodation services).

We also know particular focus is needed on children who are supported by children’s social care to ensure that provision in schools is effective in addressing their needs. Following the Review of Children in Need, which looked at educational outcomes of children with a social worker, including those that have experienced domestic abuse, the Department for Education has made up to £26.6 million available to What Works for Children’s Social Care (WWCSC). With this funding, WWCSC is testing school-based interventions aimed at understanding barriers and improving outcomes for children who need a social worker. The Department for Education will share the learning from the WWCSC trials with schools and wider safeguarding partners once the independent evaluation reports are published in early 2023. This includes the impact of interventions such as social workers in schools and supervision models for schools’ designated safeguarding leads.

(The designated safeguarding lead (DSL) has lead responsibility for safeguarding and protecting all children in their school or college. They also play a critical role in the lives of children who have, or have had, a social worker by safeguarding them, and by supporting their wider welfare, including their educational outcomes. The role of the DSL carries a significant level of responsibility. They should be a senior member of the school or college’s senior leadership team. They will have an in-depth knowledge of safeguarding guidance (such as Keeping Children Safe in Education and Working Together to Safeguard Children) and related pieces of legislation (for example the Children Act 1989), that their workplace must follow.)

To strengthen the safeguarding response for children who have experienced domestic abuse, the Home Office has been allocated £1.1 million from HM Treasury’s Shared Outcomes Fund. This will include investing in Operation Encompass, which enables information sharing between police and schools in cases where a school-aged child has experienced a domestic abuse incident, so the school is in a better position to support the affected child. The investment will enable the Home Office to:

- evaluate the current Operation Encompass scheme

- expand the ongoing pilot scheme, extending coverage to health visitors so that when the police attend an incident involving very young children (0-5 years) this information is shared with the child’s health visitor

- evaluate the extension of the scheme coverage to health visitors

- research the feasibility of expanding the scheme to other harm types

- provide a national teachers’ helpline for all staff in education settings to seek guidance about supporting pupils affected by domestic abuse following an Operation Encompass notification

This funding will also be used to review the national police response to children experiencing domestic abuse. This will help them better understand local responses and work out how to improve national practice. The review will consider how the police work with partners such as local authorities so that the response is joined up and effective in supporting children. We will consider recommendations from the research to transform the national response to children who experience domestic abuse.