Research and analysis to explore the service effectiveness and sustainability of community managed libraries in England

Published 5 September 2017

1. Executive summary

1.1 Introduction

Local authorities have a statutory duty under the Public Libraries and Museums Act 1964 “…to provide a comprehensive and efficient library service for all persons desiring to make use thereof”. In light of increased resourcing pressures, many local authorities have moved, or are now moving, to a model where they are working in partnership with communities to deliver this service.

As part of this shift towards the increased use of community managed libraries, the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) and the Libraries Taskforce, a partnership body of sector stakeholders, want to ensure that local authorities have access to the most up-to-date and accurate evaluation of delivery options when they consider how they will provide their library services in the future to meet the needs of each community that they serve. Therefore, to further build the evidence base on community managed libraries, the Libraries Taskforce and DCMS commissioned SERIO, an applied research unit at Plymouth University, to conduct an England-wide research project to understand more about how community managed libraries operate, and what lessons can be learnt and examples shared about their effectiveness, efficiency and sustainability.

The objectives of the research were to examine:

- Whether, and how successfully, they are able to deliver the 7 Outcomes identified in Libraries Deliver: Ambition for Public Libraries in England 2016-2021, including as articulated in the Society of Chief Librarians (SCL) Universal Offers and how / whether this has changed over time

- Whether the service level / quality matches expectations prior to switching to a community managed library model

- Any evidence around whether some community managed library models deliver against expectations more effectively than others

- What could be done (at local and national level) to help them be more effective

- Whether community managed libraries are sustainable over the longer-term in terms of both finances and other resources (for example staff / volunteers)

1.2 Methodology

The research consisted of a desk-based review to collect important contextual and comparative data that then informed the assessment against each of the research objectives. This included a literature review of documents, outlining expectations of community managed libraries such as service level agreements; and any research or evaluations conducted by (or for) local authorities in relation to the effectiveness and sustainability of community managed libraries.

An online baseline survey was conducted with community library service managers, staff and volunteers across the 9 regions of England, to provide a broader understanding of the delivery models and effectiveness of community managed libraries. This was followed by the development of 9 detailed case studies, one for each of these regions, to inform the research objectives. Finally, a financial sustainability review, library user survey and interviews with local authority stakeholders from across the 9 regions were conducted to assess library effectiveness and financial and resource sustainability.

The research was limited to the number and typology of community managed libraries that responded to the initial online survey, and subsequently provided consent to be contacted for further investigation. Therefore, the information collected cannot be considered a representative sample of the community managed library sector as a whole. However, additional analysis was conducted following consultation with DCMS and Libraries Taskforce (with input from Local Government Association (LGA)) to ensure, as far as possible, a representative sample of community managed library typology, age, demographic profile and geographic location across the 9 regions in England.

1.3 Models examined

The research used 3 overarching types of community library model, as described in the Libraries Taskforce’s Community managed libraries: good practice toolkit, as the basis for classifying community managed libraries for analysis and reporting. These 3 models are:

- Independent libraries (ILs) - run fully independently of the local authority library service

- Community managed libraries (CMLs) - community led and largely community delivered, rarely with paid staff, but often with professional support and some form of ongoing local authority support

- Community supported libraries (CSLs) - council-led and funded, usually with paid professional staff, but given significant support by volunteers

This typology is broadly illustrative of the different types of community library models in existence but, in practice, there is great variation in the operational structures chosen and the services offered. In addition, there are situations where more than one model is used within one council area, recognising that even within one area, ‘one size does not fit all’.

For the purposes of this research, the acronym CL will be used inclusively to refer to all 3 recognised types of community library. The acronyms ILs, CMLs and CSLs will be used throughout the report to refer to the 3 specific model types of independent libraries, community managed libraries and community supported libraries respectively.

1.4 Research findings

Analysis of the information collected during the primary research and desk-based review identified 6 major themes regarding the effectiveness and sustainability of community managed libraries. They were:

Communication and recognition

The desk based review consistently pointed towards the requirement for greater communication, understanding, and strengthening of links between local authorities and CLs. This was validated in the primary research, particularly by CMLs who cited varying levels of communication with local authorities, in addition to a perceived lack of official recognition for the role that CMLs play, as barriers to their future development and sustainability. These barriers were highlighted by CMLs as a wish for greater recognition of their services by their local authority library service and for their inclusion within national statistics. Also of note was the desire by CMLs to change the nature of the relationship with local authorities to that of both groups working on a more mutually beneficial basis, supporting each other in the delivery of local library services.

Recommendation

It is recommended that ongoing engagement between local authorities and CLs is encouraged. This could be supported by the increased promotion of existing support materials, such as the ‘Stronger co-ordination and partnership working’ section of the ‘Libraries Deliver: Ambition’ document, by the LGA to its members, and by existing CL peer networks, for example Community Managed Libraries Peer Support Network.

CLs are also treated differently by local authorities across England, with some CLs being part of the statutory service and other CLs not being aware if they are part of the statutory service or not. Increased clarity of communications at a local level between CLs and local authorities could be supported by additional national guidance for local authorities on when to view CLs as potentially providing a statutory service. It could also provide example service level agreements (SLA’s) or memorandum of understanding (MoU’s) for local authorities to use in setting out clear expectations for delivery by existing and new CLs. This guidance should be provided by DCMS and consideration should be given about whether it could take a similar format as that produced by the Welsh Government in their publication Guidance on Community Managed Libraries and the Statutory Provision of Public Library Services in Wales.

Recommendation

It is recommended that additional national guidance for local authorities is provided byDCMS. This guidance should set out when a CL should, or should not, be viewed as potentially providing a statutory service and also provide examples of SLA’s and/or MoU’s templates that can be used by local authorities to set out expectations for CL delivery of services. This guidance could take the form as that produced by the Welsh Government in their publication ‘Guidance on Community Managed Libraries and the Statutory Provision of Public Library Services in Wales’.

Shared learning

CLs cited their wish to see increased cohesion and learning developed through a nationwide peer support group that, separate to engagement with local authorities, aimed to share learning and good practice across specific issues that CLs face; a view that was echoed by stakeholders interviewed. The shared learning and knowledge created by the networks would encourage self-ownership by CLs of the challenges within the sector, and provide a route for local authorities to engage with CLs in a different manner. Peer networking could therefore take a more prominent role in catalysing development and enhancing the communication process between CLs, local authorities and other relevant stakeholders.

Recommendation

It is recommended that existing networking arrangements, such as the Community Knowledge Hub and Community Libraries Peer Support Network, are supported, developed and promoted for further dissemination by the Taskforce and its members (particularly the LGA) to relevant stakeholders, local authorities and CLs.

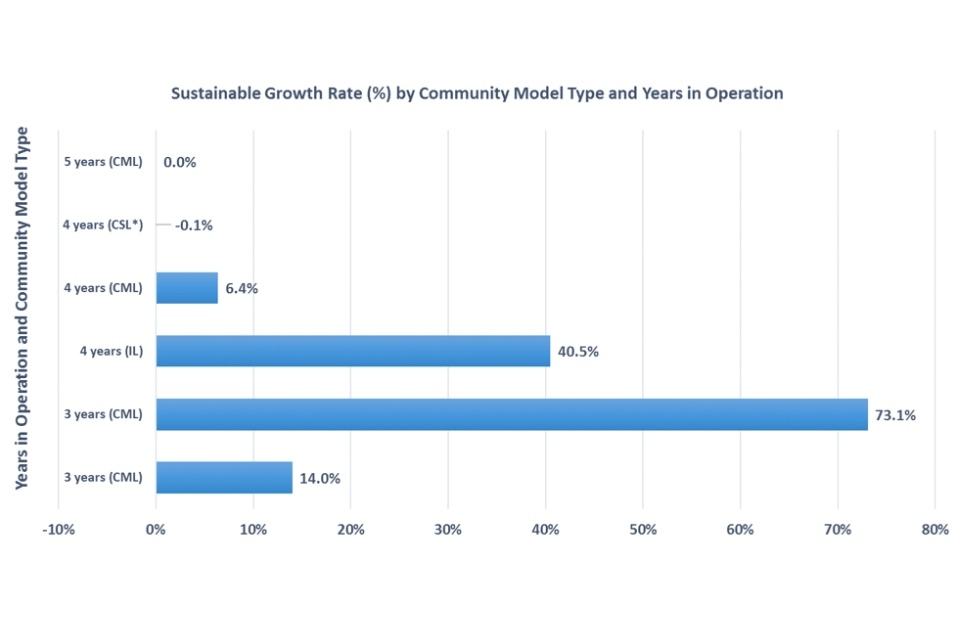

Sustainability

In terms of the effectiveness of service delivery, despite areas of commonality across the CSL and CML models, there is a great deal of variability in how these services are provided. This variability is the result of a range of localised internal and external factors, and therefore it is reasonable to argue that the CL sector cannot be fully understood by segregating library types into operational model types alone.

The likelihood of success for sustainably financed and resourced community libraries is dependent on a broad set of internal factors, such as drive, determination, volunteer availability and expertise, and external factors, such as the impact of local authority policy and resource availability.

Despite these factors, the majority of CLs indicated that they intend to grow the number and scale of their enhanced or income generating services in the future, highlighting a desire to increase revenue incomes and support their sustainable growth into the future. However, these same libraries reported that their main revenue streams will still be derived from the delivery of core services, indicating limitations to their ambitions to grow in the short-term whilst they remain reliant on some form of centralised local authority funding or support. Therefore, the current rates of sustainable growth in the research should be considered fragile.

In particular, despite the financial sustainability analysis reporting generally positive growth, current library models demonstrate a high dependency on volunteer performance and availability, and a high level of sensitivity to additional financial burden, such as increasing overhead costs.

The dependency on volunteers is particularly important, with CLs citing volunteer availability and capability as a major barrier. Volunteers represent a critical resource for revenue generation and future development, however CLs raised concerns regarding the gap in volunteer availability becoming greater as the number of older volunteers providing their time either reduced or ceased. Some CLs have tackled this barrier by developing interesting and engaging services that attract and encourage a different age range of volunteers to participate, and which can be provided without the need for additional training above that of a basic nature.

Recommendation

It is recommended that additional information and support on how to increase volunteer recruitment and improve succession planning and retention is provided by local authorities and (such as the Taskforce and peer support networks) to CLs. This could include increasing connections with national partners such as the National Citizen Service (NCS), or exploring corporate volunteering opportunities. Learning and good practice developed through this support, and areas of further research into how to attract and retain volunteers of all ages with the right skills, (as outlined in point 1 of Recommended areas of further research) should be incorporated into the ‘Community managed libraries: good practice toolkit and receive additional promotion by CL peer networks, such as the Community Libraries Peer Support Network.

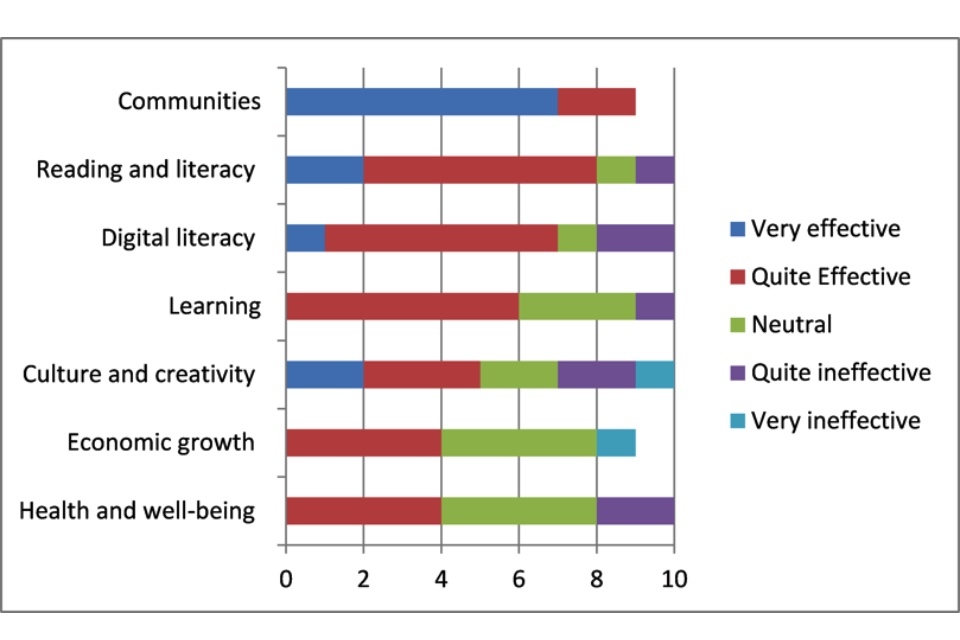

Effectiveness

All libraries reported that they felt they were delivering efficient and effective services for the majority of those services that they offer, a view that was verified by both the user survey and stakeholder interviews. Stakeholders interviewed as part of the research, which consisted of local authority representatives responsible for library services, were also generally positive about how they viewed CLs and their ability to deliver library services. When asked if they felt CLs were effective in delivering the 7 Outcomes, as outlined by ‘Libraries Deliver: Ambition’, they felt that CLs were ‘quite’ or ‘very effective’ in delivering 4 of the 7 Outcomes. Those Outcomes where stakeholders felt CLs were currently less effective were ‘healthier and happier lives’, ‘greater prosperity’ and ‘helping everyone achieve their full potential’.

The majority of stakeholders indicated that they felt that CLs had met or exceeded expectations for specific outputs including financial savings; increased opening hours, visitor counts and book issues, maintaining quality levels and increasing social capital in the local area. There were also areas where stakeholders reported that they felt that CLs were better placed than they were to deliver services that engaged and tailored services to local communities. However, a small minority of stakeholders reported that, in some cases, their expectations were set low to begin with, raising the question as to whether the performance of CLs is assessed by stakeholders on an equal basis with local authority led libraries.

Following on from this, stakeholders indicated that size, proximity to local authority led libraries, a lack of ongoing local authority support and a limited range of services on offer from CLs could be limiting factors in their future sustainability, factors that correlated with the views voiced by community libraries. However, some stakeholders confirmed that their existing support would probably continue for the foreseeable future; and all stakeholders reported that they were ‘very comfortable’ with the idea of income generation or ‘enterprising’ activities undertaken within a library context, indicating that developing this area of income generation for CLs is broadly supported.

Support

CLs identified limited sources of funding and building restrictions as major barriers. Tackling these barriers is challenging given that solutions are limited by external factors, such as the availability of localised funding and the physical building constraints that libraries operate within. Income generation activities are critical to CLs long-term sustainability, allied with ongoing support from local authorities, for example, through contributions to core funding (especially in the early years), free/discounted access to library management systems and IT, and reduced business rates and preferential lease rates. Both CLs and local authorities both recognise there is a need for more funding opportunities to be made available for CLs; ranging from minor support to more substantial grant funding.

Recommendation

It is recommended that further information and support is provided to CLs to identify, prepare and apply for local and national grant funding sources. This information and support could be provided through ‘Community managed libraries: good practice toolkit’, the CommunityLibraries Peer Support Network or by local authorities assisting CLs by providing access to information and training, ensuring that CLs are able to benefit from any funding streams that become available.

A regular theme identified by CLs is the value of ongoing ad-hoc or targeted support from local authorities that does not necessarily relate to direct funding, for example, informal advice, support with accessing local volunteer networks, and combined training sessions. This support has enabled CLs a window of opportunity to consolidate their volunteer base, ensure effective service delivery and, in particularly in the case of CMLs, develop new enhanced or income generating services that have contributed to their long-term sustainability.

Recommendation

Local authorities should be encouraged to provide on-going ‘non-financial’ and ‘provision of expertise’ support to CLs, such as informal advice, or free/discounted access to library management systems and IT, combined training sessions or preferential lease rates. This continuing support is particularly valuable to CLs in the short to medium term period (Years 1 to 3) of consolidation required to ensure their sustainable development.

1.5 Areas for further research

Following on from the themes identified by the research, a number of additional areas have been identified that would warrant further investigation – either because insufficient information was available at this stage, or because specific areas of enquiry fell outside the scope of this piece of work.

First, the availability and capability of volunteers within the community library sector was consistently identified as a significant factor for the future sustainability of community libraries. Therefore, going beyond the recommendation regarding increasing volunteer recruitment and succession planning, further research is required to fully understand the major drivers and barriers in attracting, training, developing and retaining volunteers. The learning from this further research should then be applied to the ‘Community managed libraries: good practice toolkit’.

Secondly, due to the limited number of IL respondents, additional investigation into ILs is required to fully understand their operational models and methods of revenue generation. Initial insights indicated that the level of revenue and breadth of services ILs offer far exceeds that of both CSLs and CMLs. Therefore, to provide a holistic view of the CL sector, it is recommended that areas of IL good practice are examined and disseminated to CSLs, CMLs and local authority led libraries, through updates to the ‘Community managed libraries: good practice toolkit’ and through the Community Libraries Peer Support Network.

Finally, the desk based review of available information regarding community libraries within existing literature, specifically concerning their effectiveness and sustainability, was found to be limited. However, the review did not conduct an exhaustive search of all available evidence, but rather captured significant findings that summarised current levels of understanding. Therefore, there would be benefit in conducting a wider review of available evidence to inform future research, based on the findings in this report.

2. Context and background

DCMS oversees policy on public libraries and is responsible for the promotion and superintendence of the public library sector in England. It is supported by the Libraries Taskforce, a partnership body of sector stakeholders, which is jointly sponsored by DCMS and the LGA. Their role is to provide leadership to, and help to reinvigorate, the public library sector, and to enable the delivery of the recommendations from the Independent Library Report for England. The Libraries Taskforce remit covers public libraries in England only, however it liaises with the Devolved Administrations to share information and learning.

Local authorities have a statutory duty under the Public Libraries and Museums Act 1964 “…to provide a comprehensive and efficient library service for all persons desiring to make use thereof”. Many local authorities are now working in partnership with communities to deliver this service. This may be through volunteers working alongside paid staff to run statutory services or communities taking on responsibility for delivering services. The latter may be accompanied by the library moving out of the statutory service where a needs assessment indicates the ability to withdraw the statutory council service. This move to increased community involvement is also happening in other public services, including museums, post offices, leisure centres, community halls and pubs.

DCMS and the Libraries Taskforce, want to ensure that local authorities have access to the most up-to-date and accurate evaluation of delivery options when they consider how they will provide their library services in the future to meet the needs of each community that they serve. To further build the evidence base on community managed libraries, the Libraries Taskforce and DCMS commissioned SERIO, an applied research unit at Plymouth University, to conduct an England-wide research project to understand more about how community managed libraries operate, and what lessons or examples can be learnt and shared about their effectiveness, efficiency and sustainability.

To assess how far community managed libraries successfully and sustainably support the delivery of the statutory duty to deliver a ‘comprehensive and efficient library service’, the research project required evidence to understand how effective community managed libraries are in terms of service delivery compared to other library delivery models, including:

- Whether, and how successfully, they are able to deliver the 7 Outcomes identified in Libraries Deliver: Ambition for Public Libraries in England 2016-2021, including as articulated in the Society of Chief Librarians (SCL) Universal Offers and how / whether this has changed over time

- Whether the service level / quality matches expectations prior to switching to a community managed library model

- Any evidence around whether some community managed library models deliver against expectations more effectively than others

- What could be done (at local and national level) to help them be more effective

- Whether community managed libraries are sustainable over the longer-term in terms of both finances and other resources (for example staff / volunteers), including:

- whether they are sustainable at all

- whether they are more or less sustainable than other library delivery models

- whether some community managed library models appear to be more sustainable than others

- what could be done to maximise the likelihood of long-term sustainability

- how efficient community managed libraries appear to be compared to other delivery models (including any value for money assessments readily available), in particular how the efficiencies delivered by community managed models compare to what stakeholders expected when switching to this model of library provision

3. Summary of research methods

To address these research themes, the following methodology was developed to offer robust conclusions on the effectiveness, sustainability and efficiency of community managed libraries.

3.1 Desk based review

A desk-based review was undertaken to collect important contextual and comparative data which informed the assessment against each of the research objectives. This included a literature review of documents, outlining expectations of community managed libraries such as service level agreements; and any research or evaluations conducted by (or for) local authorities about the effectiveness and sustainability of community managed libraries. A search strategy was developed that applied the appropriate significant words to academic databases and grey literature. The purpose of the review was not to conduct an exhaustive search of all available evidence, but rather to capture the main findings that summarise current levels of understanding.

3.2 Online baseline survey

An online baseline survey with community library service managers, staff and volunteers across England was conducted to provide a broader understanding of the delivery models and effectiveness of community managed libraries. This approach represented the most efficient and effective method to collect the range of data required from the different research sample populations across the 9 regions of England. Responses about issues such as effectiveness, sustainability and efficiency were collected through this online survey, providing a greater understanding of these within community managed libraries in England and enabling a comparison between the range of different community managed library models currently operating.

3.3 Case studies

Nine detailed case studies, one for each of the regions of England, were produced. Each case study was selected based upon providing the greatest range of typological, geographical, demographic and community library model and age type to inform the research objectives. Developing the case studies involved telephone and in-person interviews with library service managers, staff, volunteers, and local authority stakeholders (see section 3.6). Semi-structured interviews were used to enable an in-depth exploration of topics covered in the baseline survey as well as open discussion about the issues especially pertinent to each respondent, which subsequently provided the data required to meet the research objectives.

3.4 Users survey

410 postal surveys were distributed to the 9 case study libraries. The libraries subsequently circulated the surveys amongst their users. The survey explored users’ views and experiences of the library to provide insight into what types of services are being used, how satisfied people are with those services, and what, if anything, could be done to improve those services. As an incentive, respondents were offered the chance to win one of nine £10 Amazon vouchers and one of two £25 iTunes vouchers.

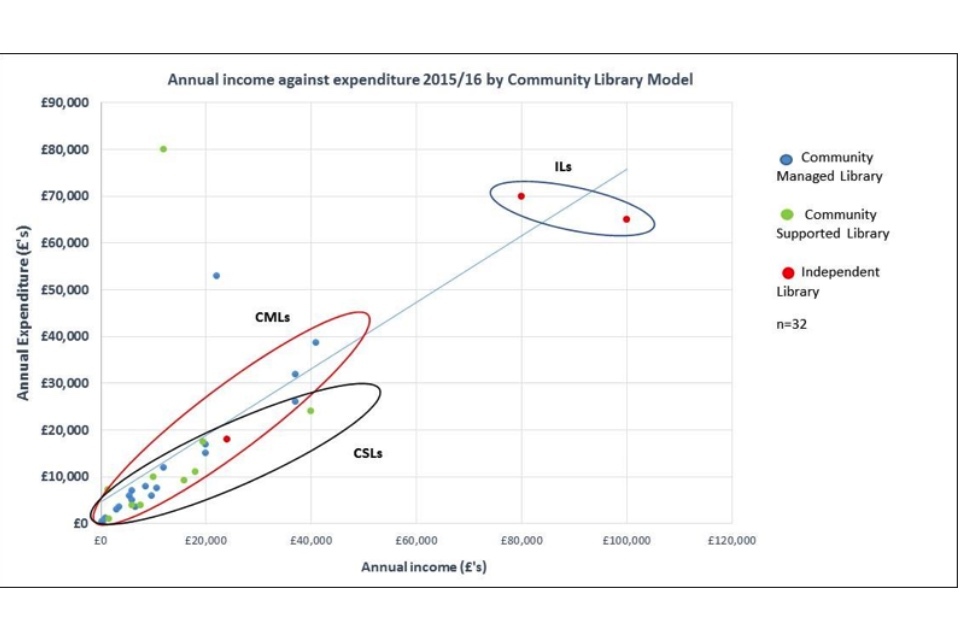

3.5 Financial sustainability analysis

Community libraries responding to the online baseline survey were asked to provide basic income and expenditure data for their libraries for the latest full financial year. CLs were also asked for consent to be contacted regarding collecting more detailed financial information. A small sample of the CLs who provided consent were asked to provide additional financial information for (up to) the previous 3 years, or from the first full financial year of trading, to assess their financial sustainability over the longer-term. Financial sustainability was assessed by comparing performance between CL models against a set of financial indicators.

3.6 Stakeholder interviews

Ten local authority stakeholders from each of the 9 regions in England were identified and invited to take part in an interview lasting approximately 1 hour to explore the following major themes:

- the library service history and provision of statutory services in the region; including if and how the local authority have been involved with community managed libraries

- where regional library services have adapted to include community managed libraries, what expectations were regarding their delivery; and perceptions of how efficiently community managed libraries perform

- opinions on the benefits or drawbacks of community managed libraries compared to pre-community managed models, particularly highlighting where community managed models have exceeded or under-performed against expectations

- views on the future direction and sustainability of library services, in the context of both local authority and community managed library models

4. Desk review of the sustainability and effectiveness of community managed libraries

The desk review of the sustainability and effectiveness of community managed libraries revealed the following findings:

4.1 The transition

Public libraries within England have connected communities and individuals over the last 150 years or so, providing a safe, neutral space for members of the community to use.

Involving the community in supporting and delivering library services is not a new concept, and groups such as ‘Friends of …’ have helped to raise funds and support the continued existence of libraries for many years. In addition, the use of community volunteers has formed part of local library provision for decades and, from the 1950s up until the 1980s, community managed libraries in the form of networks of local volunteers delivered much of rural Britain’s public library service[footnote 1].

However, with the recent resource challenges public sector organisations across England have faced, there is an increasing focus on the role communities can play in shaping and delivering their local library service. Managing resources effectively and in a sustainable manner is fundamental and, if properly supported, community managed libraries can contribute to the adaptability and innovation required to deliver an efficient library service.

It has been suggested that community involvement is not a ‘quick fix’ for strengthening sustainability within library services. Communities and local authorities need time and resources to investigate the transition to new arrangements with increased community involvement. The challenge is not simply to transfer libraries to community management to ensure local authority efficiencies, but to work with communities in a strategic manner that will create shared benefits for the local community, local government and local users.

4.2 Library models

There are various forms of community library in existence. Some local authorities pay community groups or charities to deliver statutory services; whilst other communities continue to deliver or develop their own services where local authority funding is being withdrawn. As described in the Libraries Taskforce’s Community managed libraries: good practice toolkit, there are 3 overarching types of community library model:

- Independent libraries - run fully independently of the local authority library service

- Community managed libraries - community led and largely community delivered, rarely with paid staff, but often with professional support and some form of ongoing local authority support

- Community supported libraries - council-led and funded, usually with paid professional staff, but given significant support by volunteers

This typology is broadly illustrative of the different types of community library models in existence, but in practice, there is great variation in the operational structures chosen and the services offered. In addition, there are situations where more than one model is used within one local authority area, accepting that even within one area, ‘one size does not fit all’.

For the purposes of this research, the acronym CL will be used inclusively to refer to all 3 recognised types of community library. The acronyms ILs, CMLs and CSLs will be used throughout the report to refer to the 3 specific model types of independent libraries, community managed libraries and community supported libraries respectively.

A 2016 report noted that the pace of CL growth in England is relatively rapid, with the number of CLs having increased by a fifth since 2015, from 250 to 300.

4.3 Sustainability

Libraries are operating in a changing landscape characterised by declining public funding and increased demand for digital capabilities. Leadership and a clearly articulated ‘theory of change’ is required to improve the overall sustainability and resilience in future library services. In the face of this challenging environment, CLs are adopting more dynamic strategies to remain sustainable. For example they are increasingly diversifying their services and expanding their income streams, providing secondary activities alongside their core work such as cafés or community hub facilities.

In Locality’s review of current and potential library enterprise activities, 5 important areas of opportunity for income generation were identified:

- non-library service public contracts

- private sector service contracts

- direct trading through the sale of complementary products

- charges for services, and

- new / emergent ICT services

A pilot programme explored the potential of various income-generating activities for libraries, establishing a learning base to build upon. The programme report detailed several important themes to be taken into account if income generation within public libraries was to be increased. Among them was the need for significant organisational transformation to occur and for staff attitudes to embrace service transformation. Critical elements included a need for:

- staff to buy into the vision, mission and values of the service

- staff to be duly recognised for their efforts

- for an environment to be fostered that encourages participation and innovation

Other themes included the need for libraries to consider the scope, scale and form of their service offerings, for example engaging in multi-authority partnerships to achieve greater financial returns; and considering the sale of specialist resources or assets.

However, despite these efforts, in the past 5 years the total income raised from library services has remained relatively unchanged, at around 8% of total expenditure[footnote 2].

For existing CLs, the ownership of assets was not originally a part of transfer agreements, but in relation to the development of sustainable CLs, it is beginning to play an important role. Transferring library buildings into the ownership of legally constituted community groups can open up a range of possibilities that can result in improvements to the layout and fabric of buildings. A community asset transfer can be an essential factor in increasing the prospects for future financial sustainability, with a rising number of local authorities recognising that this can form an important part of their strategic asset management. However, transferring library buildings into community ownership is not always viable, and each individual case needs consideration on its own merits. Nevertheless, in recent years, the majority of local authorities in England have started to consider the process of transferring assets to communities.

4.4 Effectiveness

There are no national performance standards or frameworks extant in the English public library sector that local authorities can assess CLs against to evidence whether they are providing effective services. Previous frameworks such as Public Library Standards and Public Library Impact Measures were removed in 2008.

Cavanagh also noted that there was little guidance available to enable robust evaluation of CL services[footnote 1]. Therefore, in the absence of clear criteria for assessing library effectiveness, Cavanagh invited 2 groups of library staff to complete an online survey, reporting on the services their library provided and the degree of importance they placed on certain aspects of library provision. He compared the responses of CL leader volunteers (volunteers, n=36) with those from leading traditional libraries (librarians, n=34). Due to the small sample size of the Cavanagh research, the findings associated with the work should be considered indicative rather than representative.

Although noting that there was no baseline to compare service provision prior to the CLs becoming volunteer-managed, Cavanagh observed that CLs offered a narrowed yet diversified service when compared to traditional libraries. They were less likely to be open in the evening, provide newspapers or magazines, or offer e-books; but were more likely to offer unique services such as a café or film nights. Librarians in traditional libraries tended to report that they felt CLs would do less well compared to when the library was professionally staffed; whilst volunteers tended to report that their CL was performing better than when the library was professionally staffed. Regarding the importance of training, librarians in traditional libraries were found to perceive various areas of training as essential, such as Equality and Diversity, Data Protection, Freedom of Information, and Customer Care, whereas volunteers were less likely to perceive training as important. Further to this, both volunteers and librarians reported undertaking less training than that perceived as being needed. For example, 100% of librarians and 46% of volunteers perceived that training in Customer Care was essential, but only 43% of librarians and 29% of volunteers reported that they had received such training.

There were also differences of opinion observed between volunteers and librarians concerning the relative importance they placed on 30 different aspects of library services. While library usage and the quality of staff/ volunteers were ranked in the librarians’ top 5 essential criteria, volunteers ranked these criteria 17th and 14th respectively. Conversely, volunteers ranked staff/ volunteer morale as the most essential criteria, whereas librarians ranked it much lower. There were some similarities in rankings between the groups, for example customer satisfaction and services suited to customer’s needs were ranked highly by both volunteers and librarians; whilst parking provision and staff/ volunteer demographics reflecting the communities served were both ranked relatively unimportant by both groups. There was also variation in the level of support that volunteers reported they were receiving from their local authority. While some reported that local authorities provided them with professional assistance whenever they needed it, others perceived that their CL was at risk of closure if footfall to the library did not increase.

Cavanagh noted that there appears to be widespread variation across the library network regarding the range of services and training provided, and the extent of local authority support. He suggested that the evidence indicates there is currently a ‘fragmented and inconsistent network of volunteer delivered libraries’ and a national library standards framework is needed to reduce service variability between and within local authorities.

To reduce service variability and support heads of library services and communities looking to establish community managed libraries, the Libraries Taskforce published the Community managed libraries: good practice toolkit. It provides guidance on establishing a community managed library, including how to engage in effective partnerships with local authorities and other stakeholders and ensure a high-quality service is provided to local people. First launched in March 2016, the toolkit is a live document which is regularly iterated and improved based on feedback.

4.5 Concluding points

From the literature search summarised in the previous section, it was evident that there is a reasonable body of literature available regarding the effective delivery of public library services. However, specific literature that addresses and investigates community run library services is relatively sparse. Therefore, this report looks to contribute to the literature specifically looking at the effectiveness and sustainability of community library models. However, as the review did not conduct an exhaustive search of all available evidence, there would be benefit in conducting a wider review of available evidence to inform future research, based on the findings in this report.

5. Online baseline survey of community library models in England

The following section provides the findings from the online baseline survey sent to all community libraries:

5.1 Library models

The research used 3 overarching types of community library model, as described in the Libraries Taskforce’s Community managed libraries: good practice toolkit, and earlier in section 4.2, as the basis for classifying community managed libraries for analysis and reporting. This typology is broadly illustrative of the different types of community library models in existence but, in practice, there is great variation in the operational structures chosen and the services offered.

5.2 Library demographics

In total, 61 libraries responded to the online survey within the three-week timeframe allocated. This reflects a 13.5% response rate, of the 442 libraries that were invited to take part.

[Please note that due to variability in the number of responses to each question within the survey, percentages reported will vary due to differing bases and/or non-responses. Response numbers will be provided against each statistic reported.]

CLs for the survey sample were identified through consultation with the Libraries Taskforce and primary desk based research. Due to non-responses, the number of CLs in the East, North East and North West regions were under-represented when compared to the other 6 regions. However, there was an even response across all of the 9 regions in terms of typology, deprivation levels and demographics. Given this, the survey cannot be considered as representative of the CL sector as a whole, but should be considered indicative of CL model and operational type across England.

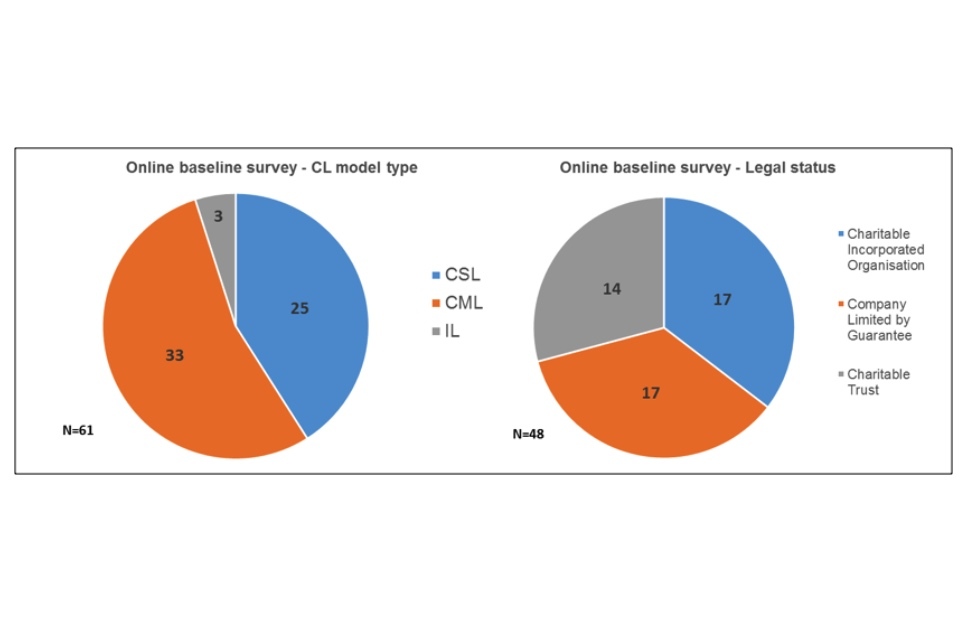

Responding libraries were located across 30 local authority areas and were comprised of a diverse range of organisational legal statuses and community library models. Chart 1 provides information regarding legal status and CL model reported from the online survey respondents.

2 pie charts showing the online survey respondents with the CL model type and legal status

Due to the low base number of ILs, any statistical comparisons drawn between the models will be limited to CSLs and CMLs.

More than half of all the libraries surveyed (60%, 36 libraries) reported that they were part of their council’s statutory library service network. Other libraries were either not part of the network (20%, 12 libraries) or they were unsure (20%, 12 libraries).

Of the 3 models CSLs are, unsurprisingly, most likely to report being part of their council’s statutory library service network; however only around three-quarters of CSLs indicated they are members (72%, 18 libraries). The remaining 28% (7 libraries) were unsure, raising questions over the clarity of communication between the library and their local authority regarding the provision of statutory services.

Over half of CMLs (56%, 18 libraries) reported that they were part of their council statutory library network; 15% (5 libraries) were unsure and 27% (9 libraries) reported that they were not. As anticipated, all 3 ILs responded that they were not part of the statutory library service network.

5.3 Delivering library services

Core library services

The online baseline survey listed 9 core services that CLs may be expected to deliver as part of the statutory network membership - a list of core services can be found in Annex 1. Of the libraries who were part of their council’s statutory library network, 86% (16 CSLs and 14 CMLs) reported that some of their services are provided as a result of their statutory network membership; the most commonly offered services included[footnote 3]:

- book loans / reservations (63%, 8 CSLs and 11 CMLs)

- wifi (40%, 4 CSLs and 8 CMLs)

- inter-library loans (30%, 3 CSLs and 6 CMLs)

- access to computers (26%, 3 CSLs and 5 CMLs)

Responses also indicated a greater appetite to engage further with their local authority with regards to providing statutory services:

Even accepting our local authority’s terrible financial situation, we would like to have a closer relationship with the statutory library service, for example marketing our activity programme through the local authority.

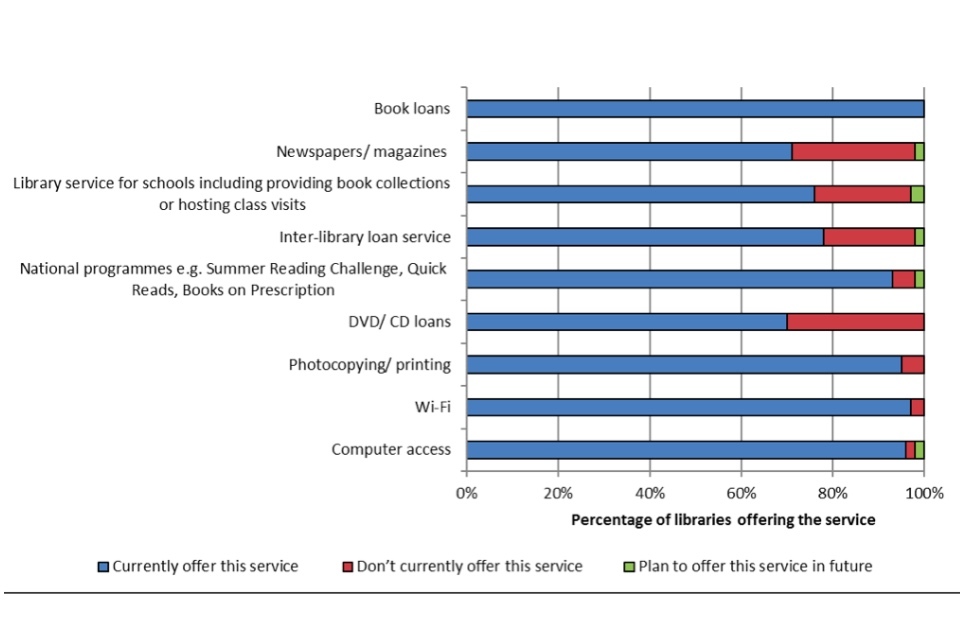

However, across all CL models, the majority of respondents reported that they offer a range of core library services, whether they are part of the statutory service network or not. CLs on average provide at least 7 of the 9 core library services listed. As Chart 2 shows, the most common services provided by both CMLs and CSLs included: book loans; photocopying/ printing; computer access and wifi provision.

Of those who offer computer access, just under two thirds (60%, 15 CSLs, 9 CMLs, and 1 IL) note that they provide this service for free. Around a third (31%, 7 CSLs, 10 CMLs, and 1 IL) said that computer access is free for a set period (for example 1 hour) or for certain people (such as children or library members), and then is subsequently chargeable. The remaining 9% (2 CSLs, 2 CMLs and 1 IL) said that all their computer access is chargeable.

Bar chart showing the core services provided by community-supported, community-managed, and independent libraries

Base: 61 (with exception of book loans n=60; newspapers/ magazines n=60; library service for schools n=58; inter-library loan service n=59; DVD/ CD loans n=59; wifi n=60)

A large majority of community libraries reported that they receive financial and/or in-kind support from their local authority to deliver the core services they provide, including:

- inter-library loan service (95%, 19 CSLs and 20 CMLs)

- national programmes such as the Summer Reading Challenge, Quick Reads, Books on Prescription (90%, 21 CSLs and 26 CMLs)

- book loans (89%, 24 CSLs and 26 CMLs)

- computer access (80%, 20 CSLs and 24 CMLs)

- DVD/CD loans (74%, 14 CSLs and 15 CMLs)

- wifi (72%, 17 CSLs and 22 CMLs)

Libraries were less likely to report that they received local authority support to provide newspapers/ magazines (30%, 9 CSLs and 3 CMLs), and library service for schools (26%, 6 CSLs and 3 CMLs).

Enhanced library services

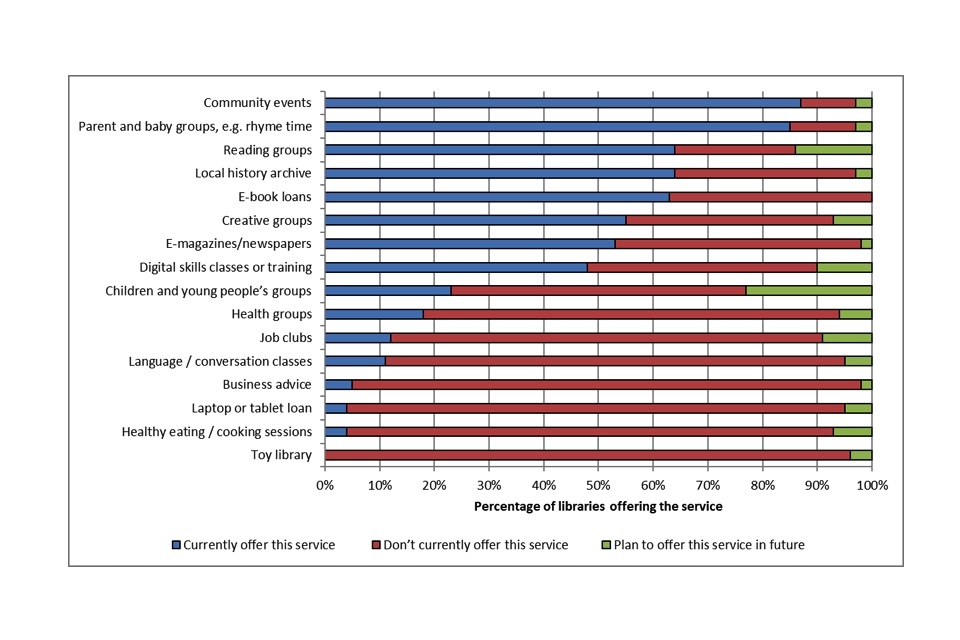

The online baseline survey highlighted variation in the types of enhanced library services CLs offer - a list of enhanced services can be found in Annex 1. From a list of 16 potential enhanced services, CLs reported providing between 0 and 12 enhanced services (mean= 6).

As shown in Chart 3, a large proportion of libraries reported offering community events and parent and baby groups 87% (19 CSLs, 30 CMLs and 3 ILs) and 85% (20 CSLs, 26 CMLs and 3 ILs) respectively. Similarly, around two thirds of libraries reported that they offer:

- reading groups (64%, 15 CSLs, 21 CMLs and 2 ILs)

- local history archive (64%, 16 CSLs, 20 CMLs and 1 IL)

- ebook loans (63%, 18 CSLs and 18 CMLs)

This is supported by comments provided by CLs within the survey:

We have an events programme including lectures, classes, activities for small children, and wellbeing sessions for older people

There are book sales, plant sales, local events information, health information, education information, and displays of local authority consultation documents

Around half the libraries surveyed reported that they offer:

- creative groups (55%, 10 CSLs, 19 CMLs and 3 ILs)

- e-magazines (53%, 15 CSLs and 13 CMLs)

- digital skills classes or training (48%, 8 CSLs, 18 CMLs and 2 ILs)

Less than a quarter of libraries currently offer children and young people’s groups, or health groups (23%, 7 CSLs, 4 CMLs and 2 ILs; and 18%, 2 CSLs, 6 CMLs and 2 ILs respectively).

Groups for children and young people was the service that libraries were most likely to report as one they planned to offer in the future (23%, 3 CSLs and 10 CMLs). With regards to the services that libraries were least likely to report offering or planning to offer, no libraries said that they offer a toy library and only 2 libraries (1 CSL and 1 CML) indicated that they plan to offer one in the future.

Similarly, business advice, laptop or tablet loan, and healthy eating/ cooking sessions were currently on offer by only 5% (1 CSL, 1 CML and 1 IL), 4% (1 CSL and 1 CML) and 4% (1 CSL and 1 IL) of libraries respectively; with only 1, 3 and 4 libraries indicating that they plan to offer these services in future.

Bar chart showing the enhanced services provided by community-supported, community-managed, and independent libraries

Base: 60 (except reading groups n=59; digital skills classes or training n=58; creative groups n=58; parent and baby groups n=58; local history archive n=58; healthy eating / cooking sessions n=57; job clubs n=57; e-book loans n=57; laptop or tablet loan n=56; business advice n=56; children and young people’s groups n=56; language / conversation classes n=56; health groups n=55; toy library n=54; e-magazines / newspapers n=53)

Overall, CLs reported receiving less support from their local authority to deliver enhanced services, when compared to core services. For example, the majority of libraries reported that they do not receive any form of financial or in-kind support from their local authority to deliver:

- creative groups (97%, 8 CSLs, 17 CMLs and 3 ILs)

- community events (94%, 17 CSLs, 25 CMLs and 3 ILs)

- children and young people’s groups (92%, 6 CSLs, 4 CMLs and 2 ILs)

- parent and baby groups (89%, 15 CSLs, 22 CMLs and 3 ILs)

- digital skills classes (80%, 4 CSLs, 14 CMLs and 2 ILs)

- reading groups (66%, 11 CSLs, 10 CMLs and 2 ILs)

- local history archive (57%, 10 CSLs, 9 CMLs and 1 IL)

The exceptions to this were e-book loans, and e-magazines/newspapers, which were reported as supported by local authorities in 100% (16 CSLs and 16 CMLs) and 96% (13 CSLs and 13 CMLs) of cases respectively.

Income raising services

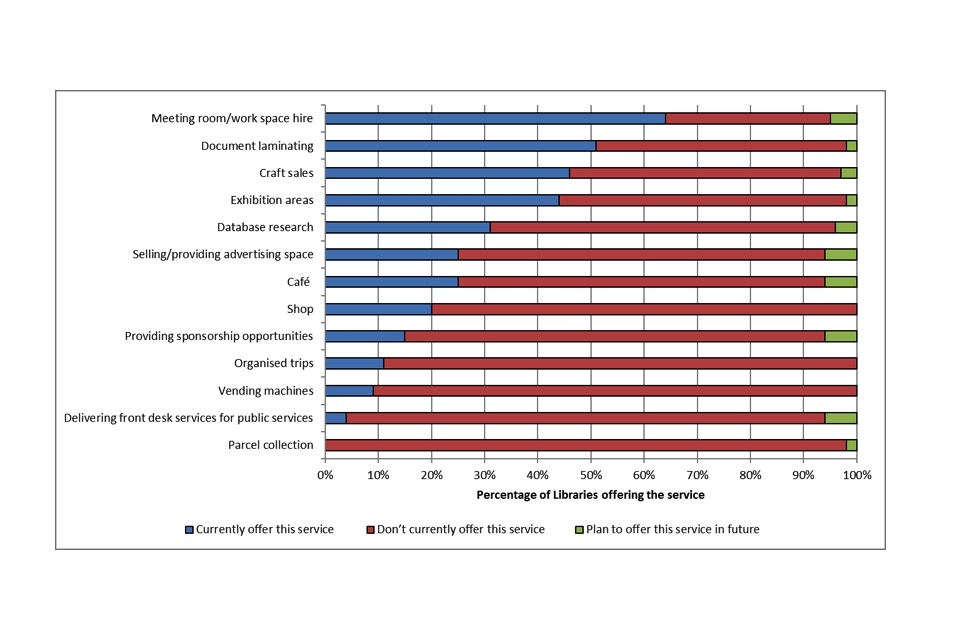

The majority of CLs reported that they currently offer at least one income raising service (81%, 46 of 57 respondents). The total number ranged from 0 to 9 and the mean number of income raising services currently offered was 3.

Of the 11 CLs (6 CSLs and 5 CMLs) who reported that they do not currently provide an income raising service, 3 noted that they plan to offer one in the future. As shown in Chart 4, the most commonly reported service currently provided was meeting room/ workspace hire, by 64% of libraries (14 CSLs, 22 CMLs and 2 ILs).

Around half the libraries surveyed reported that they provide:

- document laminating (51%, 11 CSLs, 17 CMLs and 1 IL)

- craft sales (46%, 6 CSLs, 18 CMLs and 2 ILs); and

- exhibition areas (44%, 7 CSLs, 16 CMLs and 1 IL)

A third said they provide database research (31%, 6 CSLs and 11 CMLs) and a quarter offer selling/ advertising space (25%, 5 CSLs, 8 CMLs and 1 IL); and a café (25%, 5 CSLs, 7 CMLs and 2 ILs); whilst one fifth provide a shop (20%, 4 CSLs, 6 CMLs and 1 IL).

Parcel collection was not offered by any of the CLs surveyed. In addition:

- 2 libraries deliver front desk services for public services (4%, 1 CSL and 1 CML)

- 5 offer a vending machine (9%, 1 CSL, 3 CMLs and 1 IL)

- 6 provide organised trips (11%, 4 CMLs and 2 ILs) and

- 8 provide sponsorship opportunities (15%, 3 CSLs, 2 CMLs and 3 ILs)

Although CSL and CML libraries reported providing a number of similar income raising services, there were some notable differences. For example, a higher proportion of CMLs reported providing craft sales (52%, compared to 29% of CSLs); database research (42%, compared to 29% of CSLs); and exhibition areas (56%, compared to 33% of CSLs). This may be somewhat related to the nature of CMLs, and their increased reliance on additional, sustainable sources of funding.

Bar chart showing the income raising services provided by community-supported, community-managed, and independent libraries

Base: 59 (except craft sales n=57; document laminating n=57; café n=55; shop n=55; selling / providing advertising space n=55; exhibition areas n=55; vending machines n=54; providing sponsorship opportunities n=54; parcel collection n=54; database research n=54; delivering front desk services for public services n=53; organised trips n=53)

Overall, the majority of CLs reported that they did not receive any financial or in-kind local authority support for delivering income-raising services, including:

- document laminating (100%, 10 CSLs, 17 CMLs and 1 IL)

- exhibition areas (100%, 6 CSLs, 13 CMLs and 1 IL)

- sponsorship activities (100%, 1 CSL, 2 CMLs and 3 ILs)

- front desk services for public services (100%, 1 CSL and 1 CML)

- organised trips (100%, 4 CMLs and 2 ILs)

- meeting room/ work space hire (94%, 12 CSLs, 19 CMLs and 2 ILs)

- café (92%, 3 CSLs, 7 CMLs and 2 ILs)

- advertising space (92%, 4 CSLs, 6 CMLs and 1 IL)

- craft sales (91%, 5 CSLs, 14 CMLs and 2 ILs)

- shop (90%, 2 CSLs, 6 CMLs and 1 IL)

- vending machines (80%, 1 CSL, 2 CMLs and 1 IL)

The exception to this was the delivery of database research, for which 62% (4 CSLs and 6 CMLs) reported receiving financial and/ or in-kind support from their local authority.

6. Service effectiveness and efficiency

6.1 Service efficiency

Libraries were asked how efficient they felt their library services are and the majority of respondents reported that they felt their services were running efficiently. 30% (5 CSLs, 11 CMLs and 2 ILs) reported that they were ‘very efficient’, where all or most services are running efficiently.

Almost two thirds (63%, 15 CSLs, 21 CMLs and 1 IL) reported that they were ‘quite efficient’, with room for improvement for a minority of services. Only 4 libraries (7%, 3 CSLs, 1 CML and 1 IL) reported that they perceived themselves to be ‘quite inefficient’ with room for improvement for the majority of services; and no libraries reported that they were very inefficient.

6.2 Effectiveness of core, enhanced and income-raising services

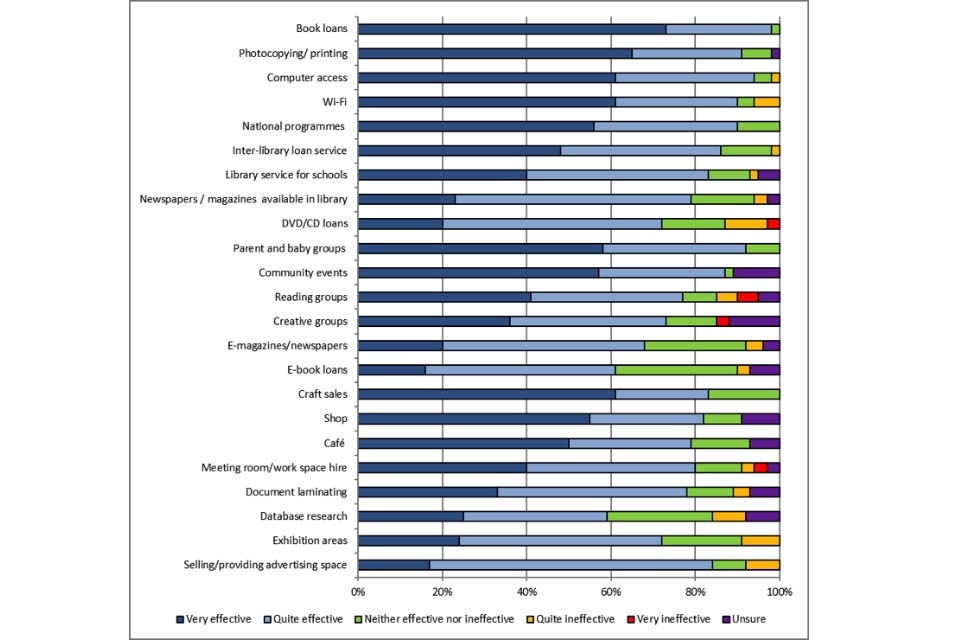

The majority of libraries reported that each of their core services was running effectively. As shown in Chart 5, the book loans service was rated as being most effective with 98% of libraries (21 CSLs, 30 CMLs and 3 ILs) who provide this service rating it as being very or quite effective[footnote 4]. Similarly, CLs rated the following services as very or quite effective:

- computer access 94% (19 CSLs, 29 CMLs and 3 ILs)

- photocopying/ printing 91% (17 CSLs, 29 CMLs and 3 ILs)

- wifi 90% (20 CSLs, 26 CMLs and 3 ILs)

- national programmes 90% (18 CSLs, 27 CMLs and 2 ILs)

The least effective core service reported overall was DVD/CD loans with 13% (2 CSLs and 3 CMLs) rating their service as quite or very ineffective.

The enhanced services that most libraries rated as being very or quite effective overall, included:

- parent and baby groups (92%, 5 CSLs, 4 CMLs and 2 ILs)

- community events (87%, 14 CSLs, 23 CMLs and 3 ILs)

- reading groups (77%, 11 CSLs, 17 CMLs and 2 ILs)

- creative groups (73%, 8 CSLs, 14 CMLs and 2 ILs)

- e-magazines/ newspapers (68%, 9 CSLs and 8 CMLs)

- e-book loans (61%, 11 CSLs and 8 CMLs)

Overall, income raising services were similarly rated as effective by the majority of libraries. For example, the income raising services rated as very or quite effective by the highest proportion of libraries were:

- craft sales (83%, 4 CSLs, 13 CMLs and 2 ILs)

- selling/ providing advertising space (83%, 3 CSLs, 6 CMLs and 1 IL)

- shop (82%, 3 CSLs, 5 CMLs and 1 IL)

- meeting room/ work space hire (80%, 8 CSLs, 18 CMLs and 2 ILs)

- café (79%, 4 CSLs, 6 CMLs and 1 IL)

- document laminating (78%, 7 CSLs, 13 CMLs and 1 IL)

- exhibition areas (71%, 5 CSLs, 9 CMLs and 1 IL); and

- database research (58%, 3 CSLs and 4 CMLs)

Bar chart showing the effectiveness of core, enhanced and income raising services as rated by community supported, community managed, and independent libraries

Base: 56 (except photocopying/ printing n=54; computer access n=54; wifi n=54; national programmes n=52; inter-library loan service n=42; library service for schools n=42; N=newspapers/ magazines available in library n=39; DVD / CD loans n=40; parent and baby groups n=12; community events n=46; reading groups n=39; creative groups n=33; e-magazines / newspapers n=25; e-book loans n=31; craft sales n=23; shop n=11; café n=14; meeting room / work space hire n=35; document laminating n=27; database research n=12; exhibition areas n-21; selling / providing advertising space n=12)[footnote 5]

Some libraries provided additional comments regarding the provision and efficacy of their services. For example, some noted that they had received positive user feedback since becoming a CL and others reported providing, or planning to provide, a greater range of services.

A common concern between CL models was the availability of physical space and the way in which this may limit libraries’ capacity to deliver more and varied services. Similarly, a lack of volunteers with the appropriate experience and skillset was cited as a concern amongst all libraries, particularly regarding their ability to deliver effective services.

We are physically a small library and are very limited in opportunities for revenue generation. We do not have a separate room that we can hire out so most events / activities have to be outside of normal library hours and involve moving the book racks each time.

Shortages of staff and volunteers means that we are unable to reach out to the 3 local schools in the way we would like to

We have received positive feedback from users about our core services and additional activities, for example increased liaison with the local primary school

A café is planned and the current library space will be converted into a theatre/conference space. We will then be able to offer a wider range of services such as reading groups, homework clubs, health clubs, as there will be more staff available

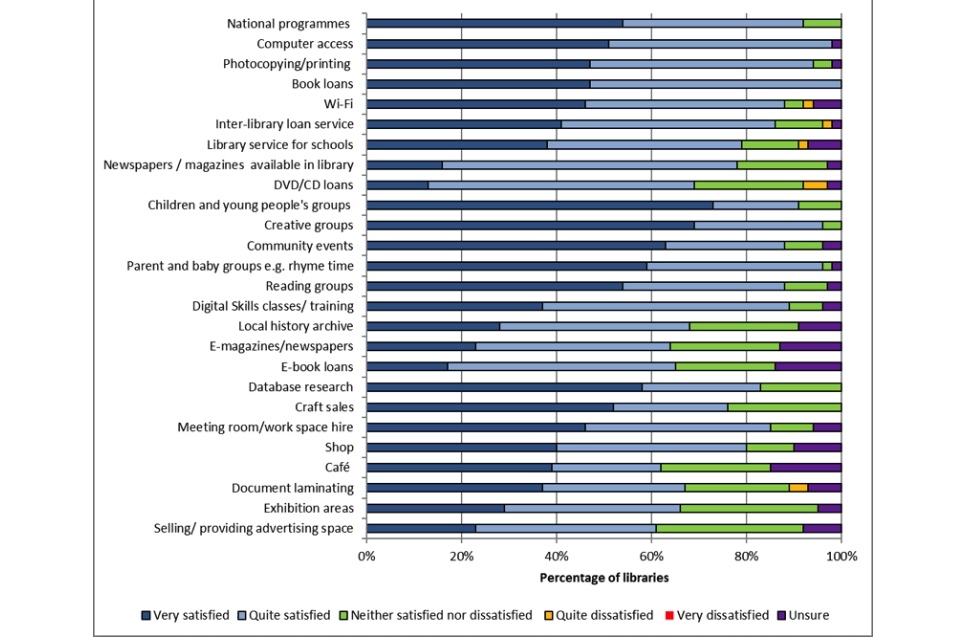

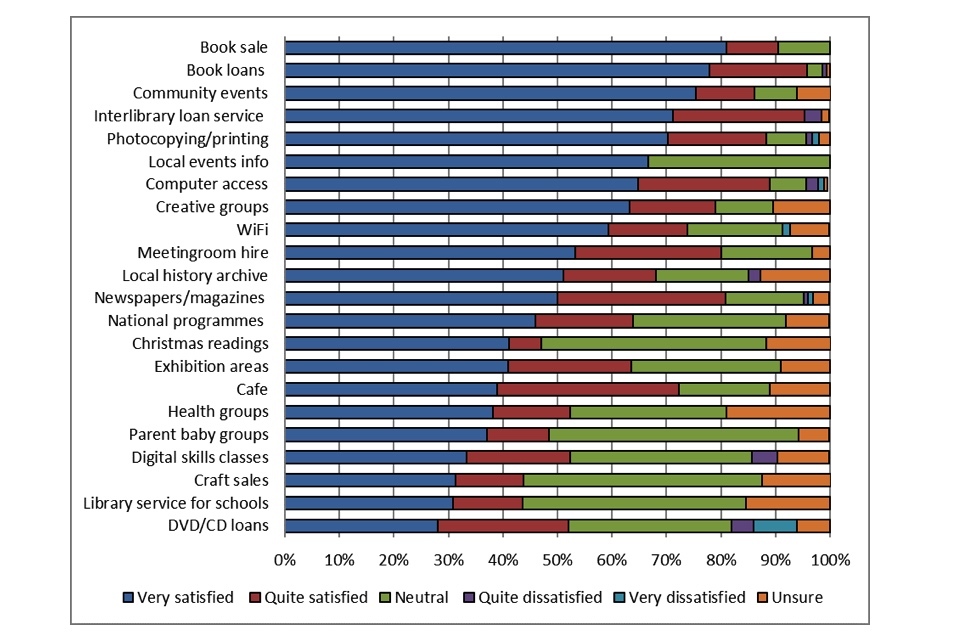

6.3 User satisfaction

Most libraries also reported that they perceived the users of each of their core services to be satisfied with the services they deliver. As shown in Chart 6, the core services that libraries reported users would be quite or very satisfied with were: national programmes (92%, 21 CSLs, 25 CMLs and 2 ILs), computer access (98%, 22 CSLs, 29 CMLs and 3 ILs), and book loans (100%, 22 CSLs, 30 CMLs and 3 ILs).

DVD/CD loans was rated as the core service that libraries perceived users would be least satisfied with, but overall was still rated highly by 69% (14 CSLs, 12 CMLs and 1 IL).

The enhanced services that most libraries reported that users would be very or quite satisfied with were:

- creative groups (96%, 9 CSLs, 14 CMLs and 2 ILs)

- parent and baby groups (96%, 18 CSLs, 21 CMLs and 3 ILs)

- children and young people’s groups (91%, 7 CSLs, 2 CMLs and 1 IL)

- reading groups (89%, 12 CSLs, 17 CMLs and 2 ILs)

- dgital skills classes/ training (89%, 7 CSLs, 15 CMLs and 2 ILs); and

- community events (88%, 16 CSLs, 23 CMLs and 3 ILs)

The income-raising services that libraries were most likely to report that users were very or quite satisfied with, were:

- meeting room/ work space hire (85%, 9 CSLs, 17 CMLs and 2 ILs)

- database research (83%, 5 CSLs and 5 CMLs)

- shop (80%, 3 CSLs, 4 CMLs and 1 IL)

- craft sales (76%, 3 CSLs, 11 CMLs and 2 ILs)

- café (62%, 4 CSLs, 3 CMLs and 1 IL)

Bar chart showing user satisfaction of core, enhanced and income raising services as rated by community supported, community managed and independent libraries

Base: 55 (except national programmes n=52 ; photocopying / printing n=53; wifi n=54; inter-library loan service n=42; library service for schools n=42; newspapers / magazines available in library n=37; DVD / CD loans n=39; children and young people’s groups n=11; creative groups n=26; community events n=48; parent and baby groups n=44; reading groups n=35; digital skills classes / training n=27; local history archive n=35; e-magazines / newspapers n=22; e-book loans n=29; database research n=12; craft sales n=21; meeting room / work space hire n=33; shop n=10; café n=13; document laminating n=27; exhibition areas n=21; selling / providing advertising space n=13)[footnote 6]

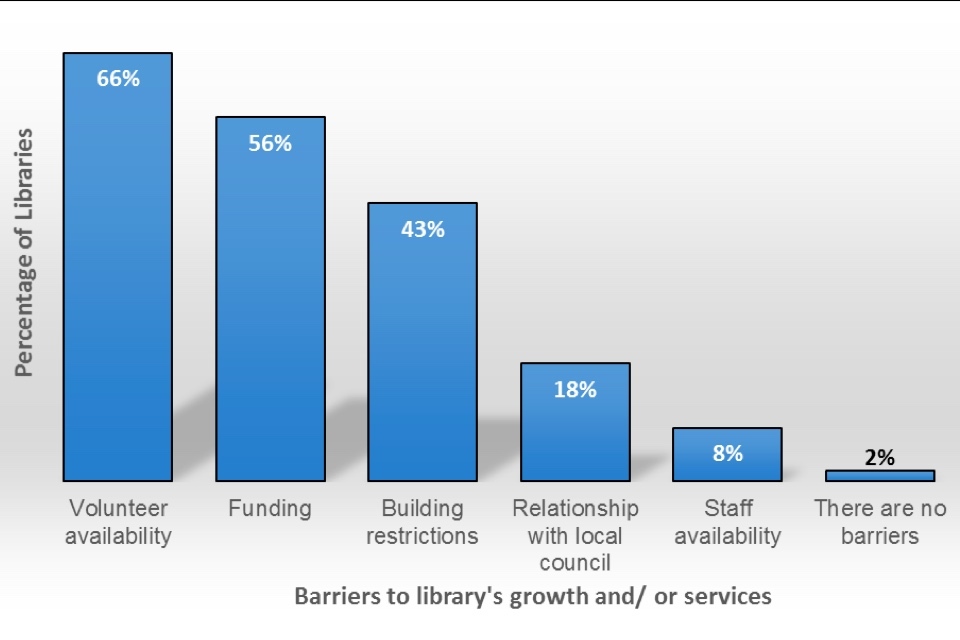

6.4 Barriers to growth

Libraries were asked to identify the main barriers to their library’s growth and/or services. The most commonly reported barriers reported by both CSLs and CMLs, as shown in Chart 7, included:

- volunteer availability, cited by 66% (16 CSLs, 22 CMLs and 2 ILs)

- funding 56% (12 CSLs, 20 CMLs and 2 ILs)

- building restrictions 43% (9 CSLs, 15 CMLs and 2 ILs)

The library’s relationship with the local council was cited as a barrier by 18% (3 CSLs, 7 CMLs and 1 IL); and staff availability by 8% (2 CSLs and 3 CMLs). Only one library (a CML) reported that they do not have any barriers to growth.

Our volunteer levels are low and it is a continual struggle to recruit people with the right qualities

The council have only agreed funding for a 4 year period. If funding then ceases, the remaining sources of funding would not generate enough income to keep the library open.

The library is small so this restricts some of the services that we offer and makes others unviable

communication is a perennial issue; for example logistics of deliveries can be difficult, usually owing to LA staffing issues, and on-going training is logistically almost impossible

Bar chart showing barriers to growth reported by community supported, community managed, and independent libraries

Base: 58 (except volunteer availability n=55; and relationship with local council n=55)

7. Resourcing the libraries

7.1 Volunteer and staff numbers

Library respondents were asked how their libraries were resourced in terms of numbers of paid staff and volunteers. As might be expected, the majority of respondents reported that their libraries have volunteers (98%, 60 of 61 libraries) and the total number of registered volunteers per library ranged from 9 to 100.

ILs and CMLs had the highest mean number of volunteers (42 and 42 respectively); followed by CSLs (mean number =33). This may be related to the degree of self-management led by the local community, in conjunction with a certain level of support provided by the local authority. Volunteers were most likely to be aged 60+ (70%), followed by 25-60 years of age (23%), 16-24 (3.5%) and under 16 (3.4%).

Only around one fifth of CLs (6 CSLs, 6 CMLs and 1 IL) reported that they have dedicated paid staff regularly in attendance at the library. Of the 13 CLs with paid staff, 8 reported that they have 1 FTE employee in paid employment by the library (5 CSLs and 3 CMLs). Four libraries said that they have 2 FTEs (1 CSL and 3 CMLs) and one IL said they have 9 FTEs.

7.2 Length of service

More than half of CLs surveyed reported that, since becoming a CL, their number of registered volunteers had increased (59%, 16 CSLs, 16 CMLs and 2 ILs). Just over a third (34%, 7 CSLs, 13 CMLs and 1 IL) said the number had stayed the same, and only 2 libraries (both of whom were CMLs) said the number of volunteers had decreased. One CML was unsure.

In addition, around half of the CLs surveyed reported that, on average, their volunteers stay involved with the library for more than 3 years (53%, 10 CSLs, 19 CMLs and 2 ILs). A further 16% (3 CSLs and 6 CMLs) said their volunteers are typically involved for between 2 and 3 years, and 10% (4 CSLs, 1 CML and 1 IL) said between 1 and 2 years.

By contrast, only 2 libraries (3%, both CML) reported that their volunteers are only involved for between 6 months and 1 year and 10 (17%, 6 CSLs and 4 CMLs) were unsure how long their volunteers stay involved with the library.

7.3 Volunteer and staff satisfaction

The majority of respondents reported that they perceive the volunteers and paid staff at their library to be generally satisfied with their role:

- 95% (20 CSLs, 32 CMLs and 3 ILs) felt that volunteers were either very or quite satisfied

- 92% (4 CSLs, 6 CMLs and 1 IL) felt that paid staff were either very or quite satisfied

No libraries reported that they felt volunteers were dissatisfied with their role, and only one library (a CSL) noted that paid staff may be quite dissatisfied.

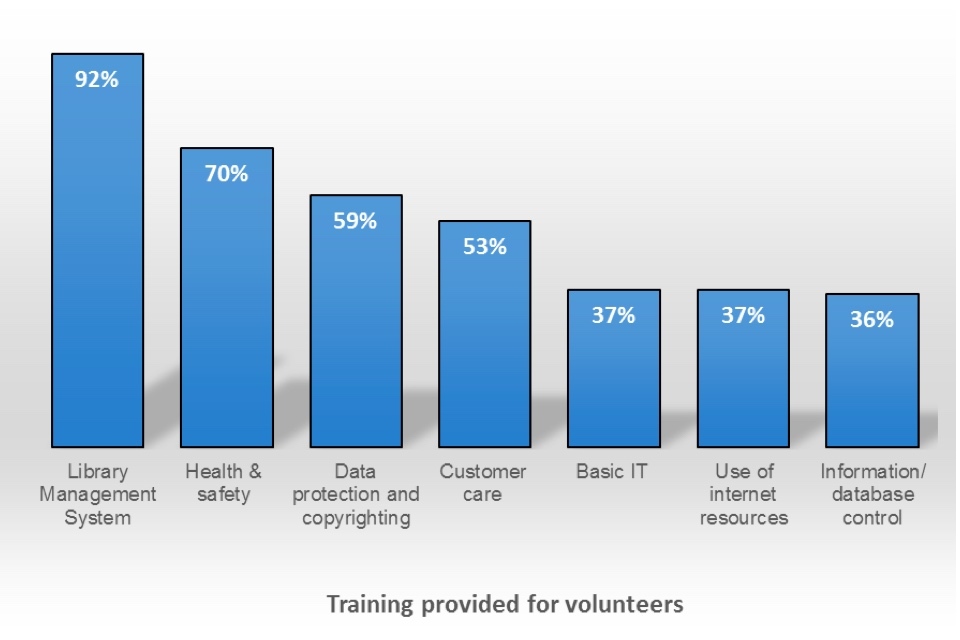

7.4 Training

Of the libraries who have volunteers, a large majority (98%, 20 CSLs, 29 CMLs and 3 ILs) reported that they perceive training for volunteers as ‘quite’ or ‘very useful’ and that they currently provide formal and/ or informal training for all their volunteers (98%, 24 CSLs, 32 CMLs and 3 ILs).

As shown in Chart 8, training on the library management system was the most commonly reported form of training provided by CLs, by 92% of respondents (21 CSLs, 30 CMLs and 3 ILs). Other training for volunteers commonly provided by libraries included:

- health and safety (70%, 14 CSLs, 24 CMLs and 3 ILs)

- data protection and copyrighting (59%, 14 CSLs, 17 CMLs and 3 ILs)

- customer care (53%, 14 CSLs, 15 CMLs and 2 ILs)

Lastly, around a third of libraries also reported providing:

- basic IT training (37%, 6 CSLs, 15 CMLs and 1 IL)

- use of internet resources (37%, 7 CSLs, 14 CMLs and 1 IL)

- information / database control (36%, 3 CSLs, 16 CMLs and 2 ILs)

CMLs were proportionally more likely than CSLs to provide training on use of internet resources (44% of CMLs, compared to 29% of CSLs).

Bar chart showing types of training provided for volunteers reported by community support, community managed, and independent libraries

Base: 59

Of the 13 libraries with paid staff who responded, 62% (2 CSLs, 5 CMLs and 1 IL) reported that they provide in-house training. The types of training most commonly provided for paid staff included health and safety (100%, 2 CSLs, 5 CMLs and 1 IL); library management system (88%, 2 CSLs, 4 CMLs and 1 IL); and data protection and copyright training (75%, 2 CSLs, 3 CMLs and 1 IL).

8. Financial sustainability

8.1 Current income

Except for ILs, most libraries surveyed reported that they receive some form of financial and/ or in-kind support from their local authority. Unsurprisingly, CSLs were most likely to report that they receive core/ majority funding from their local authority (24 libraries; 96% of CSLs in total sample); most CMLs reported that they receive in-kind support (19 libraries; 61% of CMLs). As expected, all 3 responding ILs confirmed that they do not receive any funding or in-kind support from their local authority.

The most common forms of in-kind support provided by the local authority included[footnote 7]:

- connection to the library management system (1 CSL and 8 CMLs)

- provision of new books (8 CMLs)

- provision of computers (7 CMLs)

- support and advice helpline (6 CMLs)

- professional library staff (5 CMLs)

- inter-library loan transfers/ returns (5 CMLs)

Around two thirds of respondents (66%, 14 CSLs, 23 CMLs and 1 IL) reported that they receive financial and/ or in-kind support from sources other than their local authority.

Of these, 32 libraries provided further details regarding the nature of this support. The most common sources included financial and/or in-kind support from their Parish Council (1 CSL and 10 CMLs); grants/ donations (2 CSLs and 5 CMLs); and fundraising/ earned income (2 CSLs and 4 CMLs)[footnote 8].

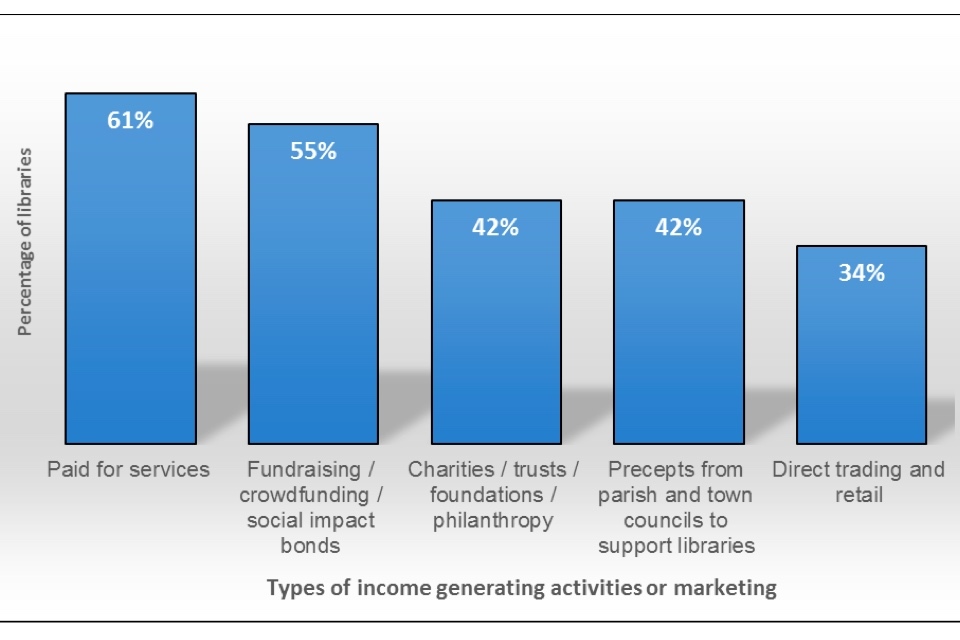

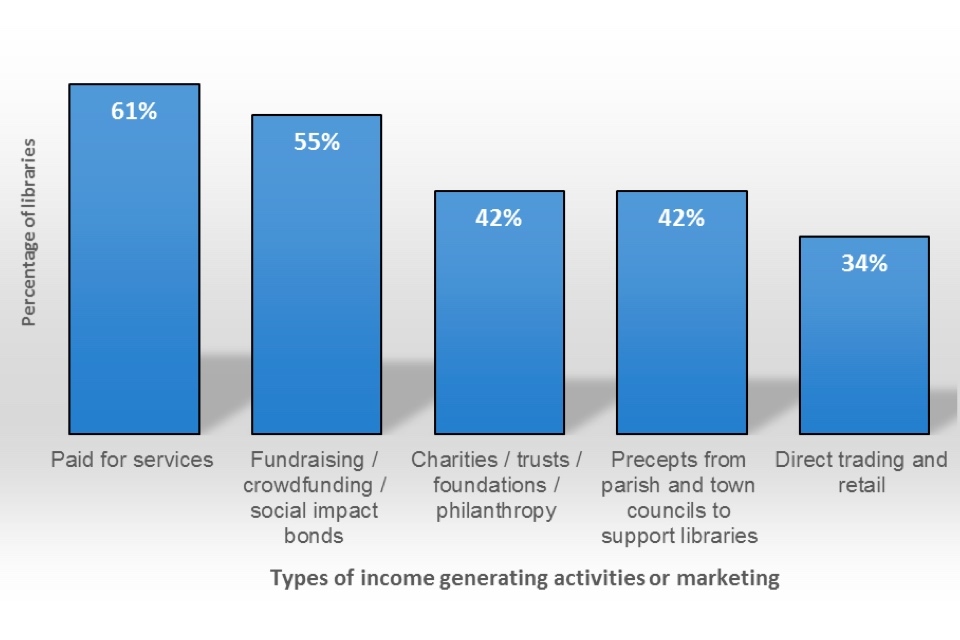

When asked about their income-generating activities, libraries tended to report a range of activities. As shown in Chart 9, the most common forms of activity cited by libraries were:

- paid for services (61%, 8 CSLs, 12 CMLs and 1 IL)

- fundraising / crowdfunding (55%, 6 CSLs, 12 CMLs and 1 IL)

- charities / trust donations (42%, 6 CSLs, 9 CMLs and 1 IL)

- precepts from parish and town councils (42%, 5 CSLs and 11 CMLs)

- direct trading and retail (34%, 6 CSLs, 6 CMLs and 1 IL)

Less commonly cited activities included:

- community infrastructure levy / section 106 agreements

- non-library service public contracts

- private sector service contracts / partnerships

- digital services

The most common paid for services that libraries reported providing were:

- room hire

- computer use

- printing / photocopying

In addition, ‘Friends of’ fundraising events were commonly reported; as were donations or grants from national charities/ organisations.

Bar chart showing the types of income generating activities or marketing reported by community supported, community managed, and independent libraries

Base: 38

8.2 Future income

Around two thirds of CLs (67%, 39 of 58 libraries) reported that they have plans in place for funding/ income generation over the next 3 years. The remaining libraries did not have plans in place (21%, 12 libraries) or were unsure (12%, 7 libraries).

Where CLs said they have future funding plans in place, they reported that the local authority would continue to provide core/ majority future income (57%, 8 libraries) or minor funding (29%, 4 libraries). For CMLs, 36% (8 libraries) reported that they would receive minor funding from their local authority, whereas 67% (14 libraries) said their future income would come from sources other than the local authority.

CLs reported similar planned future income generating activities to those they are currently undertaking. As shown in Chart 10, the most common forms of planned income activities were: paid for services (72%, 10 CSLs, 14 CMLs and 2 ILs), charity donations (54%, 6 CSLs, 11 CMLs and 3 ILs) and fundraising 20 (54%, 6 CSLs, 12 CMLs and 2 ILs).

In addition, some CLs reported they plan to generate income from direct trading and retail (33%, 6 CSLs, 4 CMLs and 2 ILs); precepts from parish and town councils (31%, 4 CLS and 7 CMLs) and community infrastructure levy/ section 106 agreements (28%, 4 CSLs, 5 CMLs and 1 IL).

Bar chart showing the types of planned income generating activities or marketing reported

Base: 39

9. Community library user survey

As part of the research proposal, a separate survey of library users was developed and undertaken through the case study community libraries. The survey was undertaken to provide additional insight into the efficiency and effectiveness of community library service provision, and to enhance, compare and validate the views of community libraries that responded to the user satisfaction element of the online baseline survey.

9.1 Library demographics

In total, 161 users responded to a postal survey, representing a 39.2% response rate from the 410 surveys distributed evenly across 9 CLs.

Please note that due to variability in the number of responses to each question within the survey, percentages reported will vary due to differing bases and/or non-responses. Response numbers will be provided against each statistic reported.

However, given the small CL sample size, the survey cannot be considered as representative of user experience across the CL sector as a whole, but should be considered indicative of CL user experience across England.

Most respondents were aged 55 years and over (84%, 135 out of 161), with the remaining 26 respondents being between the ages of 16 and 54 years of age. Over half of the library users reported that they are ‘retired’ (61%, 97 out of 159). Two thirds of respondents who completed the survey were female (66%, 107 out of 160) compared to 33% males (53 out of 160).

38 respondents (24%, 38 out of 161) were either in full-time or part-time employment and 10 (6%, 10 out of 161) were currently unemployed. Only 3 library users (2% 3 out of 161) were students and 11 (7%, 11 out of 161) did not provide their current employment status.

9.2 Library usage

When asked how often they visit the library, respondents reported:

- 46% (74 out of 161) reported that they visit ‘once or twice a week’

- 32% (51 out of 161) visit the library ‘every couple of weeks’

- 10% (16 out of 161) visit ‘once a month’

- 7% (12 out of 161) visit ‘every day or almost every day’

- 4% (7 out of 161) visit ‘every few months’

- 1 user visits their library ‘once or twice a year’

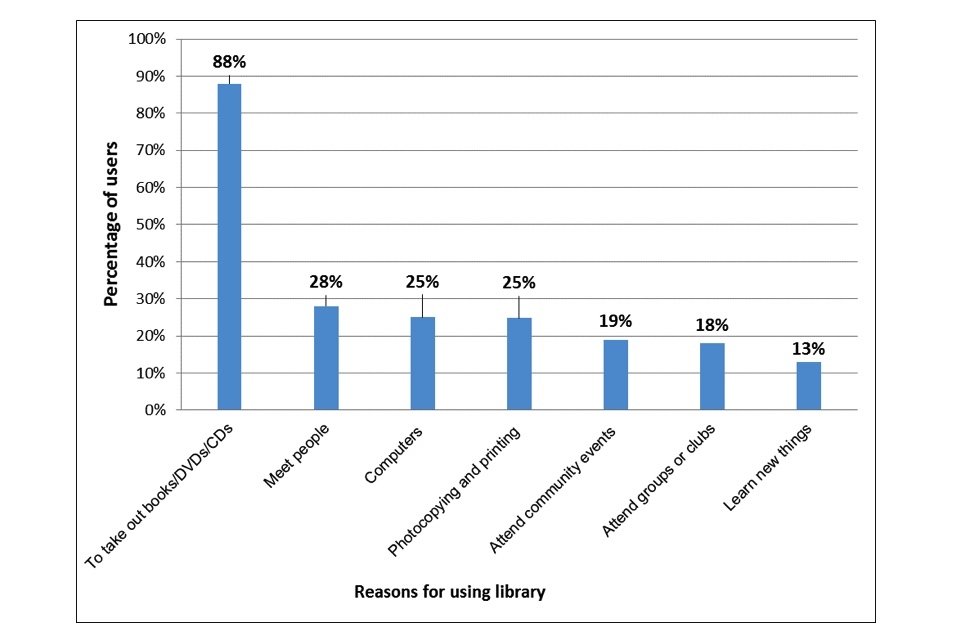

Library users were asked why they used their community library and, as may be expected, (shown in Chart 11) a large proportion of respondents reported ‘taking out books / DVDs or CDs’ (88%, 142 out of 161) as one of their main reasons for using the library.

Other primary reasons for using the library included, ‘to meet people’, reported by nearly a third (28%, 45 out of 161) of users, and to ‘use the photocopying and printing facilities’ and/or ‘the computers / wifi’ (25%, 40 out of 161 and 25%, 40 out of 161 respectively).

Furthermore, around one fifth of respondents reported that they used the library to ‘attend community events’ and ‘attend groups or clubs’ (19%, 30 out of 161 and 18%, 28 out of 160 respectively). A small number of users attend their library ‘to learn new things and/or develop skills through classes’ (13%, 21 out of 161).

Bar chart showing the frequency of library use by service amongst respondents

Base: 161 (multiple response question)

Respondents were also given the opportunity to specify any other reasons they use their library. 25 respondents provided comments, with the 2 most common reasons for using their library being ‘reading/relaxation’ (6) and ‘using the library for their children’ (4).

9.3 Types of library services used

In addition to the main reasons for visiting the library mentioned above, the libraries surveyed offered a wide range of other services that users could access. All provided the core services of access to wifi, computer access, book loans and photocopying and printing.

The vast majority of libraries also offered additional core services, including the availability of newspapers/magazines, inter-library loan service, national programmes, DVD/CD loans and a library service for schools. Having these services in close proximity within a community has been beneficial amongst library users, as indicated by user comments:

I can walk to choose my books to read, instead of having to include it as part of a major shopping trip in a nearby town.

A very important part of our village. Villagers would need to travel by car or bus / rail to reach the nearest (other) library.

Accessible books for all ages, especially important for those who cannot travel to libraries farther away. A welcoming space, where people are known, and care and attention is paid to the services being delivered.

Chart 12 provides a comprehensive view of the range of services that library users most commonly accessed[footnote 9]. The most commonly used service was ‘book loans’ (87%, 140), and over half of the users reported accessing ‘inter-library loans’ and ‘book sales’ (56%, 22 out of 39, 52%, 49 out of 95 respectively).

Just under half of respondents currently use ‘newspapers/ magazines’ (44%, 66 out of 150) and over a third use ‘photocopying/printing facilities’ (36%, 58 out of 161). Similarly, just over a third also ‘access computers’ (34%, 54 out of 161).

Please see PDF for Chart 12: Range of library services accessed by users

Chart 12 also indicates a large proportion of respondents who ‘do not use’ a variety of services, such as ‘craft sales’, ‘data base research’, ‘parent baby groups’ and ‘laptop / tablet loan’.

This result is accounted for by a combination of not all libraries surveyed offering all services, and users not accessing all of the services that are on offer. However, despite the proportion of users who cannot, or do not, access specified CL services, there were additional less tangible benefits that users identified that having their CL provides, most notably, community cohesion and opportunities for volunteering:

…a meeting place for the community to engage with one another, creating a social forum.

…a place to meet and chat with the ‘locals’. It’s a lifeline for older, lonely people.

As with any community service it provides contact with the local population & events.

In a small market town like ours, it’s a focal hub where we can find local information ie bus times, what’s going on, talk with local police.

It completes community services within the village. It provides a service and an opportunity for people to volunteer.

The benefits of a community library have been getting to know local people, finding a lovely book to read, finding out what is going on in the community and having access to all the services it provides if needed.

9.4 Perceived efficiency of community managed libraries

Library users were asked how efficient they feel the library services are. The majority of respondents reported that they felt library services were running efficiently. In particular, 68% (109 out of 160) reported that they were ‘very efficient’, where all or most services are running efficiently.

Almost one third reported that they were ‘quite efficient’, with room for improvement for a minority of services (28%, 45 out of 160). Only 1% (2 out of 161) library users reported that they perceived the services to be ‘quite inefficient’, with room for improvement for the majority of services.

Only 1 user reported that they were ‘very inefficient’, where all or most services are running inefficiently and 3 users were ‘unsure’.

Regarding the importance of efficiency for library services, the majority of users reported that they felt that this was important to them, as illustrated by some of the user comments collected:

We all have busy lives and like to complete our actions without too much delay.

It is important for things to run efficiently, as long as people are paid attention to as individuals.

Being a volunteer managed library, efficiency (& effectiveness) becomes an important ‘credible’ issue.

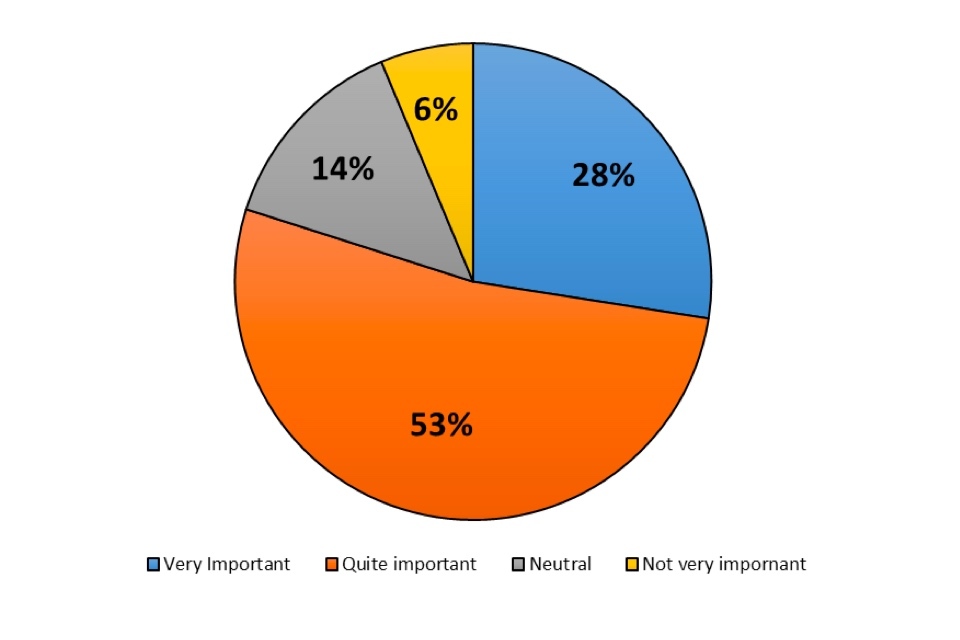

Specifically, as Chart 13 shows, 28% (44 out of 160) reported that efficiency was ‘very important’ and around half of users reported (53%, 84 out of 161) that it was ‘quite important’.

22 respondents (14% 22 out of 161) were ‘neutral’ around the importance of the efficiency and only 6% (10 out of 161) of respondents reported that speed and efficiency were ‘not very important’. No users reported that efficiency was ‘not at all important’.

Pie chart showing the user importance rating of efficiency of library services

Base: 160

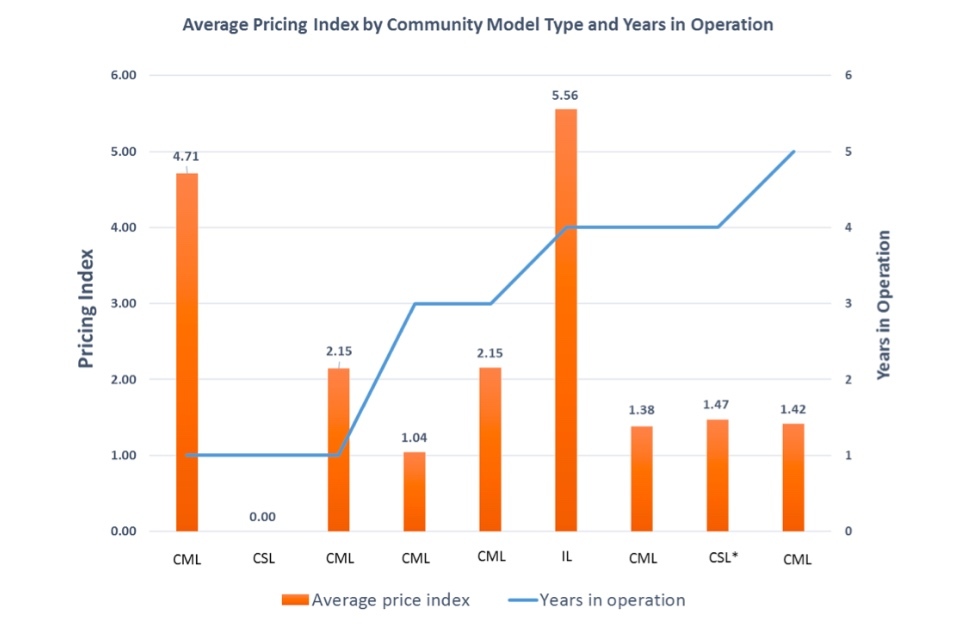

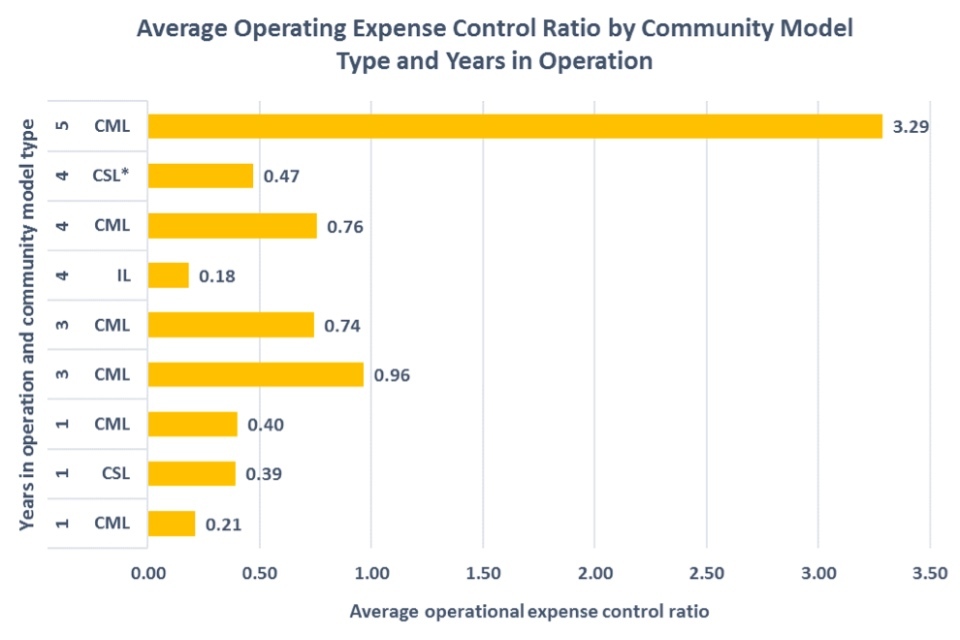

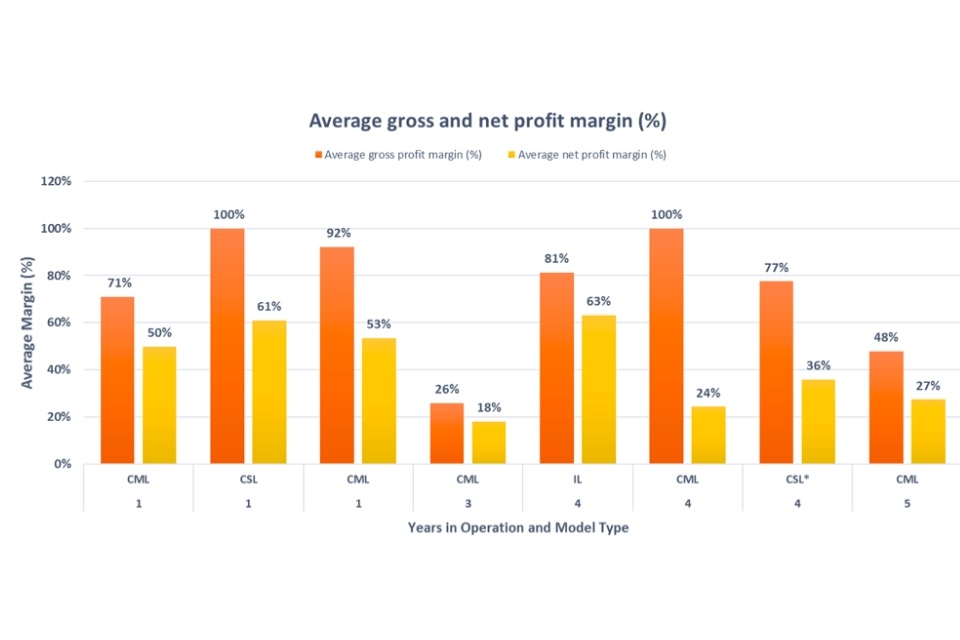

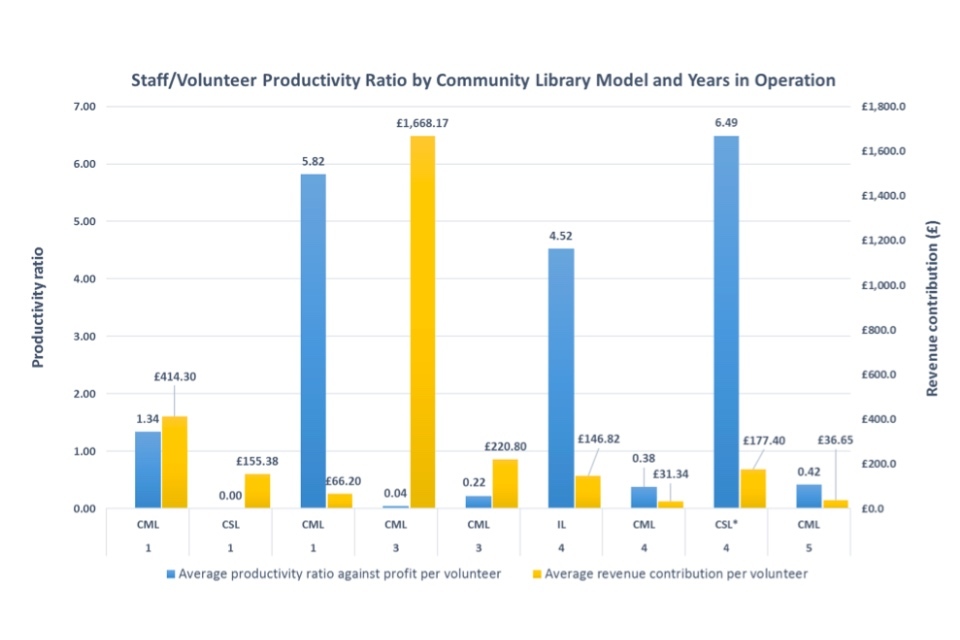

9.5 Satisfaction with library services