Strategic planning of library services: longer-term, evidence-based sustainable planning toolkit

Updated 14 November 2017

1. Introduction to the toolkit

This toolkit is designed to support:

- portfolio holders, other senior councillors and senior leaders at officer level (such as chief executives, corporate directors and those leading council transformation teams), to help them:

- understand the contribution library services can make to achieving overall corporate outcomes and objectives (see Figure 1)

- understand why they should be putting library services at the strategic centre of their thinking

- identify opportunities to link libraries into all corporate strategies

- learn from good practice in developing a sustainable library strategy to best meet the needs of local people and the communities they serve

- library service managers, to help them:

- understand how they can contribute evidence and insights to help develop and support longer-term, evidence-based and sustainable approaches to planning future library provision

- establish library services at the heart of council service delivery strategies

- achieve understanding, buy-in and commitment to a sustainable and thriving library service from senior council leaders

This toolkit has various sections and links which we hope will be useful to these different audiences as they progress through the planning cycle. These describe:

- the context within which local library service planning needs to take place

- topics and issues the Libraries Taskforce would expect strategic planning of library services to cover

- the potential for considering partnerships with other library services or other public or private organisations (including commissioning approaches) to deliver services more effectively to communities

- pointers towards different delivery models which a council may wish to consider in structuring future provision

- the ways in which local communities can be engaged in co-designing and participating at all stages of strategic planning

- the sort of data sources and tools that library services might wish to be aware of and use to help them contribute towards successful strategies.

We want to help the users of this toolkit to undertake (or contribute to) a robust, objective and evidence-based analysis of the various strategies open to them to develop their library services. By doing this, they should be able to deliver corporate priorities through a library service that will meet the needs of their local communities.

We’ll consider some of the challenges and barriers to overcome, as well as highlighting some of the benefits that can be realised.

1.1 Why develop this toolkit for planning library services?

The Taskforce’s ‘Libraries Deliver: Ambition for Public Libraries in England 2016-2021’ document emphasised that library authorities need to:

- think long-term and strategically as they plan and transform their library service

- do this in consultation with their communities

This is especially important given the challenging times councils face. They are looking for more radical and transformational approaches to providing local services as they cope with pressures on resources, increasing demands for social care and changing expectations from local communities. The way people use libraries and their expectations of public services are changing. Financial, technological and demographic challenges are increasing. Standing still is therefore not an option for library services.

Councils remain statutorily responsible for overseeing and ensuring the delivery of a ‘comprehensive and efficient’ library service - to do this, they need to listen to, and reflect, the changing needs of their communities. They’re also responsible for supporting the overall health and well-being of their areas, and ensuring that what they do provides social value. We want to ensure that the strong links between these objectives are made clearer and understood at the corporate strategic level.

Figure 1: Library services deliver against 7 Outcomes: Ambition document

Councils should work with stakeholders and local communities to consider the services currently offered by their library service. A number of library services are already developing innovative, needs-led and sustainable services that support a range of priorities and strategic Outcomes. We believe councils should view library services as an integral element of their corporate strategies, and think ‘libraries first’ when considering how to deliver services, and, most importantly positive outcomes to communities. If they do this, it will help achieve libraries’ sustainability and resilience, and promote innovation across the library sector and beyond.

The Libraries Taskforce want to ensure that councils have access to the best possible information and advice in undertaking this strategic thinking. This is so they can provide future library services that meet the needs of the local people and communities they serve.

1.2 Using the toolkit

Using this toolkit will help:

- build understanding of the context for thinking strategically about library services

- council decision makers and their transformation and strategy teams and library service staff to approach the strategic planning process in a structured, robust and objective way

The toolkit provides links to helpful resources that can be used at certain points of the process. It also highlights case studies that illustrate some of the critical stages of the strategic planning process, and good practice from library services across England.

We’ve arranged it into sections that should help users work their way through the different aspects they need to consider.

Some sections are likely to be of particular interest to transformation teams and those within corporate strategy units. These will help them understand the valuable role libraries can play in achieving corporate objectives, and the ways they support strategic Outcomes.

Other sections are primarily intended to provide library service staff with ideas on data sources and tools they could use to better develop and contribute evidence so any proposed strategy for local library services fully reflects community needs.

This toolkit is currently in ‘beta’; that means this is the first version. Some parts of the toolkit are developed more than others; we intend to add more detail and examples over time, based on what users tell us they need. During this beta phase, we’ll be continually testing and improving the toolkit. We’re looking for feedback. Please let us know your thoughts by emailing us on librariestaskforce@culture.gov.uk.

1.3 What this toolkit can help you to do

It can help stimulate the strategic thinking that will help a council develop a local library service which is strong and sustainable. Councils can do this by:

- identifying and building on a profound understanding of local community needs, co-designing services with local people, and engaging with local communities at all stages of the process

- establishing ways in which the library service can contribute to supporting the council and other local public services to achieve a range of strategic Outcomes (as set out in the Libraries Deliver: Ambition document)

- exploring and evaluating options for redesigning or improving the services it provides in the light of these developing plans for the way it will structure the service

- use the skills, resources and asset base available to it, to deliver these services most effectively

- devising ways to monitor and measure progress against the strategy to ensure the library service can adapt in an agile way to changing circumstances, opportunities and demands

The toolkit also links across to other existing sources of in-depth or targeted information or guidance. For example:

The Local Government Association (LGA) has published Delivering local solutions for public library services, which has been designed for all councillors who have an interest in supporting the development of public library services. It goes through the how and why of local service transformation and sets out ways in which councillors can work to ensure their library service excels and meets the needs of their communities.

The evidence gathered to develop strategic thinking may lead the council or its library service to consider major service changes or transformation which might involve looking at new delivery models, in either the shorter or longer-term. Step by step information on how to go about this can be found in the Taskforce’s Alternative Delivery Models toolkit.

The Taskforce has also published a good practice toolkit on Community managed libraries. This is designed to help heads of library services who are supporting communities considering taking over or establishing a community managed library. It provides insights to help those looking at this route make informed decisions, based on learning from others who have already taken this approach.

The LGA has also published New Conversations, providing guidance for councillors and council staff at all levels on consulting and engaging with residents when major service transformation is being undertaken.

2. The importance of long-term strategic planning

Under their duty of best value, councils should consider overall value, including economic, environmental and social, when reviewing services provision. Their strategic plans set out how they’ll achieve this.

We believe that fully integrating library services into these plans will help councils fulfil their obligations towards achieving social value more effectively and efficiently. This is because of the contribution that we’ve identified library services can make to delivering 7 strategic Outcomes. These Outcomes are:

- cultural and creative enrichment

- increased reading and literacy

- improved digital access and literacy

- helping everyone achieve their full potential

- healthier and happier lives

- greater prosperity

- stronger, more resilient communities

It’s important that councils think about the contribution their library service can make in this broader context as they plan and transform their services. And that they develop their thinking in consultation with their communities, and with library services staff. They should be thinking about this looking to the longer-term, as well as in the context of more immediate pressures. They need to be clear how:

- their proposals for future library service provision fit in with their overall strategy and vision for the future of their area

- how the library service can help meet their wider objectives, taking into account other local service provision, both within the area and across council boundaries

2.1 The national context

The legal framework

Any strategic planning councils do should ensure that they fulfil their statutory duties in relation to public library provision. Under the Public Libraries and Museums Act 1964, local councils in England have a statutory duty to provide a ‘comprehensive and efficient’ library service for all people working, living or studying full-time in the area who want to make use of it. Councils have the power to offer wider library services beyond the statutory service to other user groups, and the Act allows for joint working between library authorities.

In providing this service, councils must, among other things:

- have regard to encouraging both adults and children to make full use of the library service

- lend books and other printed material free of charge for those who live, work or study in the area

At a national level, the Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport has a statutory duty to:

- superintend and promote the improvement of the public library service provided by local authorities in England

- secure the proper discharge by local authorities of the functions in relation to libraries conferred on them as library authorities

If the Secretary of State investigates a complaint about a library service not meeting its legal obligations, he or she will expect that library authority to demonstrate that, in drawing up its strategy, it had:

- consulted with local communities alongside assessing their needs

- considered a range of options (including alternative financing, governance or delivery models) to sustain library service provision in its area

- undertaken a rigorous analysis and assessment of the potential impact of its proposals

More information on the legislative framework can be found in the guidance note Libraries as a statutory service. You can also see ministerial letters the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) has sent to councils where it has investigated formal complaints.

What Ambition says

In addition to this, the Taskforce’s ‘Libraries Deliver: Ambition for Public Libraries in England 2016-2021’ document, endorsed by both central and local government, said that as local decision makers plan their library service, they need to consider its:

- accessibility (physical, virtual and outreach)

- quality (mapped to local needs)

- availability (including opening hours)

- sustainability

To help locally-led decisions on libraries be made and carried out in a way that will help library services work together better, the Taskforce would like to see all library services across England designed in line with 7 principles (endorsed as good practice by the library sector).

These 7 Design Principles state that library services should:

Meet legal requirements

The public library network in England must comply with the Public Libraries and Museums Act 1964. This includes the retention of an explicit connection between national superintendence and local leadership. Councils must also comply with other legal obligations including the Equality Act and Public Sector Equality Duty.

Be shaped by local needs

Libraries should co-design and co-create their services with the active support, engagement and participation of their communities so services are accessible and available to all who need them. Library Friends groups (or similar) can help with these conversations. Public services should think ‘libraries first’ when considering how to deliver information and/or services into communities in an effective and value for money way.

Focus on public benefit and deliver a high-quality user experience

Library services should be designed to provide a high-quality user experience, based on explicit statements about the public benefit, outcomes and impact that they deliver.

Make decisions informed by evidence, building on success

Library service leaders should base decisions on evidence, data and analysis of good practice from the UK and overseas. They should evaluate the impact and outcomes of programmes and projects they run and share learning widely across the sector.

Support delivery of consistent England-wide core offers

Library services could benefit from signing up to the Libraries Connected’s (LC’s) Universal Offers which underpin the 7 Outcomes. Most already do. Not every library will deliver every Offer: local needs and circumstances may differ.

Promote partnership working, innovation and enterprise

Library leaders should empower and support their workforce to innovate and develop new services. The should also encourage them to be entrepreneurial and creative in building new service models and strengthening partnerships with public and private sector, voluntary and community organisations.

Use public funds effectively and efficiently

Councils should regularly review how they provide library services so they remain effective and efficient. In line with broader public sector reform, councils should actively examine alternative delivery models and revenue streams that could unlock additional investment.

The Libraries Deliver: Ambition document’s action plan also set 2 challenges to local government which are particularly pertinent to this set of guidance. These were:

-

adopt a ‘libraries first’ approach:

- when considering how to deliver information and services into local communities, and promote this approach to local partners

- and where the public library network is chosen as an effective and efficient method, ensure resources are provided to support this activity (Challenge LG1)

- as doing this should help to identify opportunities and synergies for aligning libraries to the broadest range of public, voluntary and commercial services locally

-

plan public library services (including consideration of cross-boundary issues) using the toolkits provided by the Taskforce (Challenge LG3)

2.2 The local context

The 7 strategic Outcomes described in Ambition map across to councils’ local objectives and priorities in fulfilling their duty to ensure the economic, environmental and social value is considered when reviewing service provision. We’d like to see library services working with their corporate strategy units to:

- discuss how local priorities each help focus library service planning (as there may be more or less emphasis on different Outcomes in different areas)

- agree how library services can be fully integrated into corporate plans

- see libraries considered as part of wider regeneration and development plans - for more information see Championing archives and libraries within local planning

2.3 Transforming library services

Councils need to take a broader transformational look at what a library service should be, and how it could be configured to adapt to changing communities and needs. If it hasn’t done so already, your council must radically rethink the way that it views library services. Across the country, local authorities are taking bold steps to transform these services, collaborating with others to find new and effective delivery models.

Your thinking needs to consider longer-term sustainability, in addition to any changes needed to respond to shorter-term pressures. This may mean looking at all the options open to you to deliver library services upfront, even if you do not intend to implement elements of these immediately. For example, undertaking a comprehensive needs assessment, and/or exploring some of the bigger changes that you may want to consider, could take a considerable time due to the need for consultation and detailed business planning. You will have to build this into your forward planning.

You may also need to consider new ways of funding frontline library services and offsetting the investment in buildings and staff through greater partnership working. Sustainable economies and efficiencies cannot come from simply trimming the libraries budget, reducing staff levels or opening hours, or making transactional savings.

A range of income generation methods, where proceeds are ploughed back into library services, can be useful to help supplement core funding or help to expand or develop new services. But this is unlikely to be able to fundamentally support the majority of what your library service needs to cover. A wider transformation programme is required – one that is rooted in the positive and essential contribution that effective libraries can make to the communities they serve.

Options you could consider might include:

Commissioning

How the library service could help councils meet their wider objectives by delivering services into communities, either by being commissioned to do so (see Understanding Commissioning: a practical guide for the culture, tourism and sport sector for more guidance on the processes and skills needed to build successful relationships with commissioners), or by acting as a venue to host others to work with local people. In both cases, these contributions should be appropriately remunerated - either specifically paid for or offset against library service savings targets.

Service integration

How the council could explore aligning library service provision with other local services - both within the council area (whether council or partner-run) or across borders. For example, what are other important local strategies (such as NHS Sustainability and Transformation Plans) saying, and how can corporate strategies and library service plans align with these?

Co-location

There may be opportunities to integrate and co-locate library services with other government and partner services who share library values or user groups, particularly as part of the One Public Estate programme. This can join up services for users, allow buildings to be opened for longer, and enable costs to be shared. For example, South Woodford Library, where the co-located gym effectively cross-subsidises and complements the newly refurbished library provision.

Shared services

Most councils across the country are sharing services with other councils or public services in some way. Doing this successfully can result in financial efficiencies and also non-financial benefits such as increased resilience and business transformation improvements.

The LGA has produced a councillors guide to shared services and management. It shares information on the variety of arrangements which are being pursued across the country, and across different types of service (including offering a matching service and access to expert advice). This may help you to decide whether this is a way forward for your library service. It has also undertaken research to evaluate the benefits of this sort of arrangement, and look at what is required to enter into it. This provides detailed analysis of five high-profile shared service arrangements, including insights into the scale of savings that have been achieved through sharing back office functions like IT and legal, and the benefits of teaming up to deliver frontline services like waste disposal and road maintenance.

Although many arrangements are made with neighbouring councils or other public services this need not be a constraint: for example, Essex County Council partner with Slough Council to develop their library service – although the organisations are some 70 miles apart.

Case study: Rutland County Council – strong coordination and partnership working

The development of the Ketton Library and Surgery Hub was the result of strong partnership working between county and parish councils, the local GP surgery and the NHS. The councils were exploring ways to increase the use of the library site - by extending beyond traditional library services – when, in 2010, the Ketton surgery announced its intention to close because it could not be upgraded to meet modern standards. This created an opportunity to improve the accessibility of both the library and the surgery, and thereby retain essential local services. The library became a joint service hub with the surgery in June 2012. Since then, customer numbers have increased for both the library and surgery – with library use increasing from 7,077 visitors in 2012 to 9,749 visitors in 2016, a 38% increase.

Ketton Councillor Diana MacDuff said:

The Ketton Hub is a great example of how successful a multipurpose site can be. The increase in library use is partly due to the additional footfall that has come about as a result of the inclusion of nurse and surgery services in the same location. Multipurpose sites are particularly relevant for our villages, where the retention of local services is vital to maintaining their identity and community spirit.

Remodelling service delivery channels

Maintaining a comprehensive and efficient service for future needs won’t necessarily mean retaining the same buildings or range of services if needs have changed.

People often think of libraries as buildings - a community focal point and an important public shared space. These can play a critical role in wider social regeneration and place-shaping work, and as a valuable resource for use by local services and community groups alike.

But library services are more than bricks and mortar or even the people, stock and resources sitting within a building. Libraries can also provide services through outreach - with skilled people taking services out into communities - and virtually - allowing access to a wide range of online resources and online spaces for people to meet and learn from each other.

Library staff are an important asset that councils can deploy to deliver services into communities. Their skills cover a multitude of disciplines - such as information management, service advice, community engagement, and digital skills.

To meet local needs, the council may need to consider remodelling future services, building new skills and services, and delivering services differently. Following changes in population, transport, technology and patterns of use over the last decades, the location or layout of some library buildings may no longer be suitable for the things local councils and communities want their library services to do. There may be an argument for replacing universal mobile services by more targeted outreach services; or a growing demand for excellent digital services to provide library access and transactions 24/7. The crucial thing is to ensure that decisions like these, including where and how a library service is provided, should be made based on robust evidence. This includes a comprehensive and evidence-led assessment of local needs. It should also be actively managed with the community and library professionals. This may look very different in different areas; for example between urban and rural locations.

Case study: Hampshire mobile library service

Hampshire library service analysed their mobile library costs and usage. This demonstrated that mobiles had far higher costs (and lower value for money) then the more specialist and targeted home library service. However basing the argument to close it down on a clear analysis on value for money and impact data meant that a potentially controversial decisions received little feedback from politicians or residents (even those who had previously been users of the mobile library service).

As part of this work, once the council is clear about what it wants to deliver for the future and the resources available, it may decide that it wants to explore different ways of structuring and delivering the service. The Taskforce’s Alternative Delivery Models and Community Managed Libraries toolkits provide more detailed advice and guidance on what councils and library services will need to consider if they want to look at these options. These are likely to be decisions that need to be planned with a long lead time - they shouldn’t be seen as a quick fix for immediate resourcing pressures. If councils do consider these options, we want to ensure that all parties involved make informed decisions: understanding the pros and cons and learning from others who have gone before. The aim should be to continue providing a high quality service to local people whatever the decision a council makes on these issues.

3. What are you aiming for?

A clearly articulated strategic approach to library service provision can help councillors, library professionals, stakeholders, communities and library users work together to achieve shared strategic outcomes which benefit their communities. Developing this thinking will also help to identify opportunities for library provision to become an integral element of other council strategies, and thereby increase the service’s sustainability.

3.1 What should this strategic approach cover?

Every council will have its own templates for how it sets out strategies, and its own processes it follows to develop them. But broadly speaking, we believe that a strategy which covers library services should include:

- a description of how the library service fits with national policies, and the design principles set out in the Ambition document

- a description of the council / area covered by the service - spelling out community needs, based on robust data and evidence (see Annex A for sources of this information)

- a description of the current position of the library service - strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats

- an assessment of the changes that the library service will face in the foreseeable future - for example, demographic, societal trends, changing customer demands and the nature of the local economy

- a vision for the library service showing how it connects to the vision, mission and corporate strategy of the council

- a statement of the strategic outcomes the library service will help deliver on behalf of the council (bearing in mind Ambition’s challenge to local government to think ‘libraries first’ in delivering services to local communities)

- a statement about how libraries feature and are embedded in others’ strategies (other departments or partners); including any plans to seek commissioning by others, and the skills, resources and relationship building strategies required to move to this position

- details of the library service’s strategic priorities to guide development

- a description of the services that it will seek to provide for the future, and any areas where the service is proposing to either expand, or withdraw from or reduce (see section 4.2)

- a statement of any significant new development or investment required to achieve the library service’s strategic aims - for example in staff skills, building or facilities changes, digital development

This should be accompanied by:

A clear, costed and realistic delivery plan for implementation. This should include:

- how the future service will be delivered (including buildings, mobile and outreach and digital provision)

- any significant shifts proposed between delivery channels and the rationale for those proposals

- targets for outcomes

- efficiency savings

- income generation

This plan should take into account:

- accessibility (physical, virtual and outreach)

- quality (mapped to local needs)

- availability (including opening hours)

- sustainability

Information on how the service will be monitored and improved in the future against the priorities and targets specified in the delivery plan.

Clear statements about what commitment or support the service has from important stakeholders/decision makers/partners.

Case study: Hampshire library service transformation strategy

In April 2016, Hampshire County Council published a new strategy that set out a transformation programme to provide a comprehensive and affordable library service through innovation, modern thinking and business leadership. Around 9,500 people and organisations participated in a public consultation exercise that helped inform the strategy.

3.2 Processes to get there

To achieve this, it’s important first of all to achieve senior level buy-in from both councillors and corporate officers, including commissioners. They need to understand how libraries can contribute to other corporate priorities, and be prepared to embed them into these other strategy documents. This will mean that library services will need to communicate with these other services in terms they recognise, to articulate their relevance and encourage investment. The Cultural Commissioning Programme has some useful advice and case studies on how this can be approached successfully.

Councils should be able to demonstrate how they have come to the conclusions and ways forward set out in their future plans for the library service. When the DCMS is considering complaints about proposed changes to library services, it will look to see:

- how the council / library service has consulted with local communities and involved them in co-designing the future library service (see section 6)

- what evidence the council / library service used to make its judgements about assessing local needs (see section 5)

- that the council / library service have considered a range of options (including alternative financing, governance or delivery models) to sustain library service provision in the area in the long-term (see our toolkit on Alternative Delivery Models for more detailed advice on options appraisal)

- that the council / library service has undertaken a rigorous analysis and assessment of the potential impact of its proposals

Case study: London Borough of Sutton

The consultation on changes to Sutton libraries was backed by research mapping demographic trends and needs analysis across the borough. This was so staff had a clear view of the communities the libraries serve.

This toolkit will, over time, include sections covering each of these areas in more detail, providing pointers and links to good practice guidance and advice.

3.3 Using your strategic plans

If the council and library service gets their strategic thinking right, they’ll have:

- a sound basis for future development of the library service in line with community needs, based on a shared understanding of strategic priorities with crucial stakeholders and local people

- an explicit statement of how the library service contributes to overall corporate objectives, and library service contributions acknowledged and embedded in a range of other council strategies

- a forward plan on how the library service will be aiming to work in partnership with other local organisations or neighbouring boroughs

- a clearly stated business plan for what the library service is going to do and achieve in the future, and how it proposes to get there (including a plan for developing or acquiring the skills and resources it will need)

- an advocacy document they can use to influence future approaches to potential commissioners or partners

- a set of measures they can use to assess progress against objectives and outcomes specified

- a greater appreciation and understanding by library managers and staff of the data they need to use in advocacy or to evidence the impact they achieve

4. Developing your strategic thinking

4.1 Where are we now? Using the benchmarking framework

We’ve established a benchmarking framework, based on descriptions of a range of aspects that make up library services. Library services can use this to self-assess how they are currently performing in delivering their services. This is against a spectrum of descriptors (from an adequate service through to an excellent one) - and then think about how they would like to do so in the future.

The sort of issues this covers are:

- measuring performance against local strategic outcomes

- delivery against each of the Ambition 7 Outcomes and LC’s universal offers

- levels attained against a range of practical aspects, relating to things like stock, user visits and satisfaction, and staff development

- exploring the roles of leadership, governance and management, and evidence-based decision making

The benchmarking framework is a self-assessment tool, which is not competitive but simply an exercise to help you to develop awareness and agree priorities for improvement. It involves a mix of consensus discussion and analysis of data (for example performance data and feedback from stakeholders) and is conducted by a Self-Assessment Team, comprising managers and other leaders as identified in your Organisational Model. It should not take more than a few days to complete.

This could be a useful tool to help kick off strategic thinking. It can be used to establish a current baseline on all these issues, and help to develop thinking on where the library service wants or needs to be against them (if that differs). We’d also suggest that you use the benchmarking tool as a useful and practical way to engage in debate with stakeholders, commissioners, local communities and users and to validate or challenge your thinking. It can also be used to build their knowledge and understanding of what library services can offer them.

4.2 What do we want to be doing? Defining your functions

As part of the initial thinking about what services could be provided in the future, council strategists and library service staff may find some of the guidance on defining functions included within our Alternative Delivery Model toolkit useful. In particular, the section on service profile and growth strategy. This provides a service definition template to use to help consider the future service profile. As well as to decide, in the light of the evidence gathered on local needs, which services should:

- continue as they are

- be redesigned to meet needs more effectively or make better use of resources

- be reduced in their scope and scale, or stopped completely

- be designed from scratch to meet emerging or anticipated needs

It also includes templates to help thinking about growth strategy, and ways to increase income to offset any potential future funding reductions. To help assess whether this will be a practical prospect, tools can be used for a:

It’s important that, at this stage, councils and library services consider their services in the widest context possible. This will mean ensuring that your thinking covers things like:

- cross-border and partnership working

- co-location and integration with other services

- digital offer

Cross-border and partnership working

Councils should be looking at how the library service can help meet their wider objectives, taking into account other local service provision both within the area and across council boundaries. We believe this up-front thinking will pay dividends longer-term. Particularly where existing library provision sits near to council borders, we encourage neighbouring councils to talk to each other when considering any service changes. We’d like to see them looking at how they can consciously coordinate their future planning to give local residents the best possible access to high-quality library services irrespective of exactly where administrative borders fall.

One example might be in considering the design of a mobile service route which has the potential to take in rural areas on both sides of the council borders. These services can prove too costly for an individual council to operate, but collaboration across borders could mean that additional reach and shared operating costs make sustaining it viable.

For other areas, collaboration on purchasing and marketing arrangements may prove more appropriate. The Taskforce has information and case studies on joint procurement and consortium arrangements in the Smarter Working section of our Libraries: Shaping the Future toolkit.

Case Study: LibrariesWest Consortium

The LibrariesWest consortium is a partnership between the library services of Bath and North East Somerset, Bristol, Dorset, North Somerset, Poole, Somerset and South Gloucestershire. It aims to achieve significant economies of scale and to deliver better services for customers.

Co-location and integration with other services

We’re keen to encourage councils and library services to actively consider whether local services can be integrated better; and as part of this, whether library services can be co-located with other services to increase the benefits and impact for local people.

However, doing this needs to be considered and planned carefully to:

- understand the synergies that can be achieved

- realise the potential benefits

- avoid clashes between the needs of different user groups

A starting point is to think through whether the organisations that might co-locate with the library share its values. The council needs to guard against undermining the public’s perception of the library by partnering inappropriately. It also needs to guard against losing the distinctive value of public libraries – the ethos of the service, the skills of people staffing it, and its role as a non-judgemental community venue - by moving too far down the path of seeing it as simply a customer service point for other services.

Doing this well isn’t just about putting a number of services into a shared space but then continuing to operate separately. You get most benefit for users and the service when service delivery is integrated wherever possible - shared support services, staffing arrangements and IT. The council also needs to think carefully about how the finances of co-location will work; so that the contribution the library service makes through the space it provides is properly accounted for and remunerated.

This means looking at a range of issues such as:

- any commonality of users, and any synergies that can be realised

- the impact on staff

- designing accommodation to retain flexibility and to cater for any special needs (for example privacy for certain groups or uses and any child protection or noise issues)

- opening hours

- shared systems or support contracts

- the time and resource it will take to manage the process properly

- managing the financial implications (both initial establishment and subsequent cost allocation)

- retaining the distinctive role and value of the library in considering this route

Case study: Ashburton library - Co-location with a Post Office

Ashburton library service worked with 13 communities to explore different ways of delivering its services. Its co-location emerged from the collaboration and partnership between the community, Devon Libraries and a local business (the Post Office).

In Worcestershire, there are numerous different examples of collaboration and co-location, which vary according to community need. These include:

- Wythall library - a joint provision with the Woodrush Academy, supported by the local community and parish council

- Bewdley library - a new library alongside a new local medical centre

- Malvern library is co-located with Jobcentre Plus, they are expanding to do the same in Kidderminster and Redditch

We have further information and case studies on co-location in the Smarter Working section in the Taskforce’s Libraries: Shaping the Future toolkit.

Digital offer

Developing a compelling virtual presence which integrates seamlessly with the physical library provision, is increasingly important as more people communicate, use services and engage digitally. An improved digital presence can, in turn, stimulate and increase physical visits. At present, many library services have a limited and outdated web presence, but tackling fundamental redesign at a local level presents challenges in the current environment. As local resources are limited, we’re looking on a national level at how libraries’ digital presence can be improved, by developing a Single Libraries Digital Presence. More details are set out in Outcome 3 of the Libraries Deliver: Ambition document. Councils and their library services need to think about what digital service they want to build, based on local needs and interests - this could cover not only access to materials, but also building virtual spaces for people to meet online, co-create and debate (for example online book clubs).

Library services’ digital offer can also be enhanced by increased provision of e-books, e-magazines and e-newspapers, allowing people who prefer to read using digital devices or can’t easily visit the library to access a wider range of material. Councils and library services need to consider how to promote these services, possibly in a targeted way to those less able to access library services in other ways.

Low-cost and accessible technologies are fuelling a new wave of creativity, problem solving and entrepreneurialism. Makerspaces have emerged as a response to that opportunity. They vary from a simple space with work benches to a fully equipped lab with a wide range of digital, creative and manual tools. Councils and library services could consider how this sort of facility can be developed to link into other local agendas. These could be:

- local economic development

- digital skills

- building science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) skills (or STEAM as it is now sometimes becoming referred to, by also including the Arts)

- encouraging entrepreneurship

Case study: Makerspace in Fab Lab Devon

A makerspace is a physical location where people gather to co-create, sharing resources and knowledge, work on projects, network, and build. A number of larger public libraries already have successful makerspaces, including Exeter’s FabLab.

And alongside this, councils should consider the vital role that libraries can play in gearing people up to live safely and successfully in an increasingly digital world. Libraries are important in increasing digital access (by making internet and wifi access available, alongside peripherals such as printers, in their buildings) and digital literacy (through their role in providing digital skills training and support in using vital online services). But libraries also have an important and growing role to play in developing people’s ability to handle and make judgements on the plethora of data and information that they access online.

4.3 Resourcing your strategy

Finance

Section 3 of the Ambition document highlights the challenges faced by local government in funding library services. Wider financial and demographic pressures have meant that there is no longer the same level of funding available for library services. So to secure a sustainable future for library services, councils need to adapt and think beyond previous efficiency approaches, to take a more transformational approach to delivering services locally. Understanding the role that library services can play in delivering other council priorities and embedding their use into those strategies will help to secure core funding.

Over recent years, government policy has been to reduce centrally-distributed funding to local authorities, and to encourage local authorities to become increasingly self-sustaining, based on self-generated revenues (such as fees and charges). This seems likely to continue against the backdrop of Brexit and ongoing deficit reduction. A strong revenue and capital financing strategy needs to be developed and articulated alongside strategic service delivery discussions and negotiations.

We’ve already mentioned the growing importance of commissioning as a source of financial investment to support library services’ activities. The Taskforce has published material pointing to guidance on various approaches to income generation (including things like facilities hire and retail). Many library services are already required to meet corporate income generation targets.

Undertaking these activities successfully means assessing whether the library service has the skills and capacity to do so (and if not, how it can acquire or develop these), and also taking a very clear-sighted view on whether the returns will justify the investment that this activity will require. We ran income generation Masterclasses to share information and learning on the range of activities that library services could consider. There are some useful guides around on these topics for organisations which share some similarities with library services. For example, The National Archives published an income generation guide in February 2016 which has useful sections on things such as cost benchmarking and marketing.

We’ll shortly be developing further guidance on other alternative funding streams including social investment and philanthropy.

But before looking further afield, libraries need to continually assess whether they can demonstrate clear value for money to potential delivery partners; and improve efficiency in their core activities. For example, shared savings or joint procurement can offer considerable savings (such as the LibrariesWest consortium arrangements). However these benefits can be diluted by individual library services insisting on retaining bespoke arrangements - these just build additional costs back in. The Taskforce will undertake further work to look at how this type of issue can be identified, the implications costed, and good practice promoted widely across the sector.

People and skills

A skilled and experienced workforce should be at the heart of any library service, combining expert information skills, with the ability to engage with communities to deliver outstanding services that support and enhance the prospects of all citizens. This makes them a powerful asset for councils to use to help achieve wider corporate outcomes and deliver services successfully in communities.

To maintain and develop a thriving library service for the future, the council and the library service will need to be clear about what capacity and capability they need to deliver against their objectives. As well as how they will attract, retain and develop the right people to achieve this.

CILIP (The Libraries and Information Association) and LC have published a Public Libraries Skills Strategy which sets out the challenges facing the sector and the actions they think need to be taken to address these.

Examples of practical issues councils should consider as future plans are developed, are:

- the numbers of staff needed, and in which parts of the service

- the current balance between different skills sets (for example, information skills, commercial disciplines and customer service), and whether / how this might need to change for the future

- any new demands the library service might need to respond to (for example skills in bid-writing, higher level digital expertise)

- the profile of the existing workforce, and what the service might want to do to:

- address diversity issues, to align its workforce more closely with the community it serves

- establish programmes such as apprenticeships and internships to bring in new talent

- develop and deepen or extend the skills of their existing workforce

- the extent to which future plans rely on recruiting and using volunteers to augment library service staff, and what needs to be done (and what investment made) to train them and develop their skills

- collaboration with other sectors (for example schools, higher education or training) to access or develop transferable skills

5. The importance of evidence

With decreasing budget and resources, councils need to find innovative ways to reduce costs while maintaining service quality and meeting their statutory obligations. Data plays an important role in making informed decisions, leading to new insights that can result in unexpected benefits.

For instance:

Meeting community needs

Data can be used to identify particular groups within a community who may need support, or particular issues that need tackling, such as obesity or the provision of digital skills training.

Meeting corporate priorities

With pressures on council budgets, every service has to be clear about how it is delivering against these council priorities. (Many library services will already be delivering work against these priorities, but being able to build an evidence base for their approach will help demonstrate that to decision-makers).

Targeting services or designing new ones

Any changes to a service, including considering new models of delivery or service re-design should be based on what the local community looks like now, is expected to become, and its needs. Evidence is critical to understanding these different elements.

Being efficient

Using evidence of what your community needs as a basis for future service planning will help you focus on services and activities that achieve the best possible outcomes for your resources. As well as considering what library services will be needed as new communities are created, through increases in housing developments.

Meeting statutory duties

Local authorities have a statutory duty under the Public Libraries and Museums Act 1964 ‘to provide a comprehensive and efficient library service for all persons’ in the area that want to make use of it. Using evidence to inform proposals, and consulting with the community are two important ways to help meet this obligation. They will be considered carefully by DCMS if a complaint is made about your provision.

5.1 Libraries working together with corporate strategy teams

Central corporate statistics and analysis experts will have access to the main data sources on local population, communities within the area, and their general needs. But it’s important that library service staff understand what these data sources cover, and use what these sources say to think about what future service priorities might be. And library services should be discussing with their data experts what other information they and their staff could help draw out at a service level. This extra data could be used to:

- complement the centrally held data to help with planning

- assist in subsequent monitoring of the effectiveness and delivery of plans and strategies

- gather evidence on longer-term service impact

Annex A lists important data sources (both internal and external) that library services should be aware of and discussing with corporate strategy colleagues.

5.2 Structuring your evidence gathering

Councils and library services need to focus on gathering the evidence to meet strategic requirements. These will vary between local situations so this toolkit can only be a guide. The 7 design principles identified in Libraries Deliver: Ambition may help design this process. These are:

- meet legal requirements

- shaped by local need

- focus on public benefit and deliver a high-quality user experience

- make decisions informed by evidence

- support delivery of consistent England-wide core offers

- promote partnership working, innovation and enterprise

- use public funds effectively and efficiently

If the library service is aiming to deliver services commissioned by other council departments or partners, it will need to consider what sort of information the commissioner will expect the proposal to include, and how it will measure delivery against their objectives. The Cultural Commissioning Programme provides practical advice on how to understand what commissioners might need and how to go about gathering this evidence.

5.3 Measuring your outcomes

There is no standard way for measuring outcomes, and you will need to use a range of different tools depending on what activity you are measuring. Wherever possible, explore whether there are existing measures or tools that can be used to capture progress. Also, check with key partners, such as corporate leaders, councillors or commissioners, that they will consider the evidence to be robust enough to influence their decision making.

For instance, if you are being commissioned to deliver a health intervention, your commissioner may have an accepted method for collating data and impact. This may be based on a quality standard from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), as in this example for promoting mental wellbeing and independence for older people. Demonstrating knowledge of these standards may also help you secure commissions from health commissioners.

For cultural activities, you may be able to draw on the Arts Council England Measuring Outcomes tools, which also contain further advice on collecting data.

For reading activities, you may be able to use the Reading Agency’s Reading Outcomes Framework toolkit which can help you to measure the impact of reading for pleasure and empowerment.

Norfolk Library Service has also developed a simple evaluation workbook to help library staff capture data from activities in their library branches and identify the impact, as well as link them to corporate priorities.

Annex A: using data to inform your thinking, sets out a range of data that could be used to look at different aspects and outcomes of library services. It covers things like:

- using local knowledge

- understanding changing needs

- what data sources a library service might find useful and where these are likely to be held, internally and externally

Annex B: useful datasets, lists some of the most common datasets that may be of use to library services as they discuss and explore strategic needs and priorities. [Annex B can be downloaded here]

Annex C: data tools looks in more detail at data tools that are available, in particular LG Inform and LG Inform Plus. LG Inform is a free online tool that brings together a range of core data for councils, alongside demographic and financial information. LG Inform Plus is a subscription service for authorities to drill down further from the top level strategic metrics in LG Inform to more detailed information.

It is very important that library services focus on devising ways of collecting evidence about the impact and outcomes they achieve through the interventions they provide. We’ll be developing more detailed sets of guidance on this, for example:

- how library services can measure their activities (for example via event attendance and use of digital assets) and link these to outcomes

- how library services can make better use of existing user data - for example, that gathered via library membership / card use - to help understand user behaviour and to target services, whilst being sensitive about individuals’ privacy

- good practice relating to user research - looking not only at collecting opinions and ideas about services, but also ways to capture information and insights based on user behaviour

In many cases, you will be able to use recognised research to demonstrate impact and then relate this locally. For example, as there is clear evidence that participation in the Summer Reading Challenge helps to maintain reading standards over the school holidays, you can put your efforts into maximising participation and recording this to evidence your impact. Similarly, the fact that research shows that running high quality rhyme time sessions has a beneficial effect on language development means that, if you run similar things locally, you can extrapolate this to demonstrate your contribution to the local objectives that this supports.

Arts Council England, as the development agency for libraries in England, also publishes research into the impact of libraries, most recently on: the contribution of libraries to the wellbeing of older people and the contribution of libraries to place-shaping.

The LGA carried out a literature review as part of the LGA’s research into community action. This provides useful background reading for those looking to find out more.

Inspiring Impact published the Code of Good Impact Practice in June 2013. Inspiring Impact makes the case for an impact approach, exploring the benefits – including how focusing on impact can help improve services, motivate frontline staff and reduce monitoring burdens – and weighing these against the costs of measurement.

The Home Office have published an Indicators of Integration framework which references libraries and could be used when demonstrating the contribution of your library service to other policies.

6. Co-designing with your communities

One of the 7 Design principles set out in Libraries Deliver: Ambition says that library services should:

co-design and co-create their services with the active support, engagement and participation of their communities so services are accessible and available to all who need them

The LGA has developed a tool, New Conversations, which provides detailed guidance on how to undertake successful consultation and engagement, and helps councils self-assess how effective they are. It also suggests ways to improve and shares practical tools to use, alongside case studies of good practice.

It goes into detail on legal requirements regarding consultation and engagement. For example:

Equality

The Equality Act 2010 states that public bodies must have “due regard” to a variety of Equalities objectives (Equality Act 2010, Section 149). Consequently, Equality Analysis (formally Equality Impact Assessments) must be carried out to demonstrate that decision-makers are fully aware of the impact that changes may have on stakeholders. The concept of “due regard” was reinforced in 2012 during the review of the Public Sector Equality Duty which “requires public bodies to have due regard to the need to eliminate discrimination, advance equality of opportunity and foster good relations between different people when carrying out their activities”.

Best Value Duty Statutory Guidance

This guidance applies to how “authorities should work with voluntary and community groups and small businesses when facing difficult funding decisions.” It requires councils to consult on any changes to policies and services with regard to efficiency, economy or effectiveness. It states that authorities are to “consider overall value, including economic, environmental and social value, when reviewing service provision.” To reach this balance, prior to choosing how to achieve the Best Value Duty, authorities remain ‘under a duty to consult representatives of a wide range of local persons.’ This duty to consult is not optional. Section 3(2) of the Local Government Act 1999 provides details on those who should be engaged in such consultations.

New Conversations also provides useful guidance on the common-law doctrine of legitimate expectation, giving case law examples of how this applies.

6.1 Engagement

As the library service and council strategists work on ideas about where the library service might go, what it should be focussing on for the future, and what it will look like, this thinking should be used to prompt a two way conversation. By involving internal and external viewpoints throughout the decision process, councils stand the best chance of reaching the best solution.

Engagement with, and led by, frontline staff is critical to learning about what the community values, needs, and would like done differently. As well as harnessing their ideas for new ways to deliver services or new things the library could help to provide.

Engagement involves working with staff and the community to help get their involvement in designing future services, and seeking insight into what local people think and feel, to help make services more responsive to residents’ needs. It might involve a whole variety of listening events and tools, both face to face, through correspondence or digitally.

When engaging with local people, it’s just as important to talk to people who don’t currently use library services as well as those that do. So you can find out why they don’t; and whether the library service should offer new or different services, offer them in new or different ways, to meet their needs.

6.2 Consultation

Consultation is a more specific process. A definition used by the LGA is:

The dynamic process of dialogue between individuals or groups, based upon a genuine exchange of views with the objective of influencing decisions, policies or programmes of action. (Elected Member Briefing Note, Improvement Service and TCI, 2013.)

Consultation tends to have a clear ‘beginning’, ‘middle’ and ‘end’. The scope for input should be clear and it must be meaningful. You should share and consult on a range of options and make it clear to the community what they can influence (and, just as importantly, what they cannot). The consultation process should inform your decision making and you should be open to considering suggestions made during it.

It is important to clearly explain how you have revised your plans in light of the consultation.

Case study: Peterborough City Council

Peterborough’s library network comprises 10 libraries and a mobile service. Local residents value these libraries not only for books but as community meeting places and for education, computer and internet access.

In 2014, a public consultation showed that the most valued aspects of the library service were the ability to borrow books, access to information and location. When people were asked what would make them use their library more, 75% said that access outside of normal opening hours was important. In response to the consultation, the council developed a range of models and opted for the Open+ model, delivered by Bibliotheca, as its preferred option. Open+ uses technology to complement a library’s core staffed hours by extending opening times. It has enabled all the libraries to remain open through a combination of staffed and extended self-service hours. This option was put out to a second public consultation and won overwhelming public support.

7. Annex A: using data to inform your thinking

There are a number of data sources available. But you will want to use and focus upon those that are relevant to the priorities you have identified for your council and that will assist in designing a library service that meet local needs.

7.1 Local knowledge

You need to use local knowledge when considering service re-design or the location of facilities. This is important where there is significant change in population, when sources like the census rapidly become out of date. Your public health colleagues will tend to have the most up to date and accurate information on demographics, often drawn from the Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA), but corporate plans and Local Plans will also be helpful.

Local knowledge will help you decide where a service could be most effectively located. For instance, research has shown that libraries are typically most used when connected to good local transport options and near other local amenities that residents visit at the same time. These are some of the reasons why multi-service hubs such as Canada Water library, Southwark and Stafford Central Library have seen an increase in visitor numbers. This is also why effective engagement and communication with your local community is so important (see section 6).

Some of the local spatial planning data that you might want to consider includes:

- local travel and passenger routes, held by the highways team (alongside data on things like household car ownership)

- areas of high footfall, held by town centre or planning teams

- the location of other council assets, such as leisure centres, museums or underused buildings, held by public estate teams

- the location of other public facilities, such as jobcentres, GP surgeries or community centres, run by partner organisations

- up to date demographic intelligence, from ward councillors or community cohesion teams, or library staff.

Remember that you also need to capture information on the needs of people who don’t use library services, which will give you ideas on how to broaden your offer to meet the needs of the whole community. The community profile that you build up should form the opening section of your library strategy, and place your proposals and your offer in their local context.

7.2 Changing needs

The future needs of your communities are important to establish. For instance, if your local development plan outlines intentions to build significant extra housing, the council should consider the cultural (including library services) and other infrastructure required to support it. As part of this, there could be an opportunity to fund new library building from any section 106 money contributed by the developer. This does not include covering stocking or staffing the building, so the library service needs to consider how it will cover these aspects. The National Archives and Arts Council England have written a guide on local planning processes, including section 106.

Case Study: Bicester library

Bicester library had long been planned by Oxfordshire County Council and Cherwell District Council as part of Franklins House, a new community building at the heart of the multi-million pound regeneration of Bicester town centre. The new library, with greatly improved facilities, is a focal point for a town that is growing yet retaining its own distinctive character as an Oxfordshire town. The project to create the new library was paid for by developers as part of the expansion of Bicester. As such, there was no cost to the public purse.

Discussions with neighbouring library authorities might reveal an opportunity to co-operate with them on a new development or shared facility. Assessment of how well the community’s future needs have been considered in service redesign plans is something DCMS considers in assessing whether councils are continuing to meet their statutory duties. It is important to ensure that the evidence on this has been fully explored.

The information contained in this toolkit is a sample of the data already available to corporate strategy teams. Library service staff may be able to supplement it with other, more locally detailed data, about user preferences, service usage, activities, user behaviour and outcomes. We will be publishing further sections of this toolkit covering issues such as user research and visit data in the future.

7.3 Corporate information

Corporate plan

The council’s corporate plan sets out its strategic objectives. The library service needs to demonstrate it is delivering against these objectives, preferably against more than one. Libraries are well-placed to do this. By framing services around these objectives, library services can achieve greater traction with corporate decision-makers and budget holders.

You should get involved in the corporate planning process as early as possible. You will need to identify the major corporate themes and map them against the possible contribution of the library service. Library services can deliver against almost all of the most common corporate priorities - such as improving education and literacy, promoting public health and wellbeing, and supporting local small businesses. However, their contribution is not always fully understood so you should be prepared to set out the practical details of how the library service can deliver for them. The evidence collected to inform your library strategy will help you build a persuasive case.

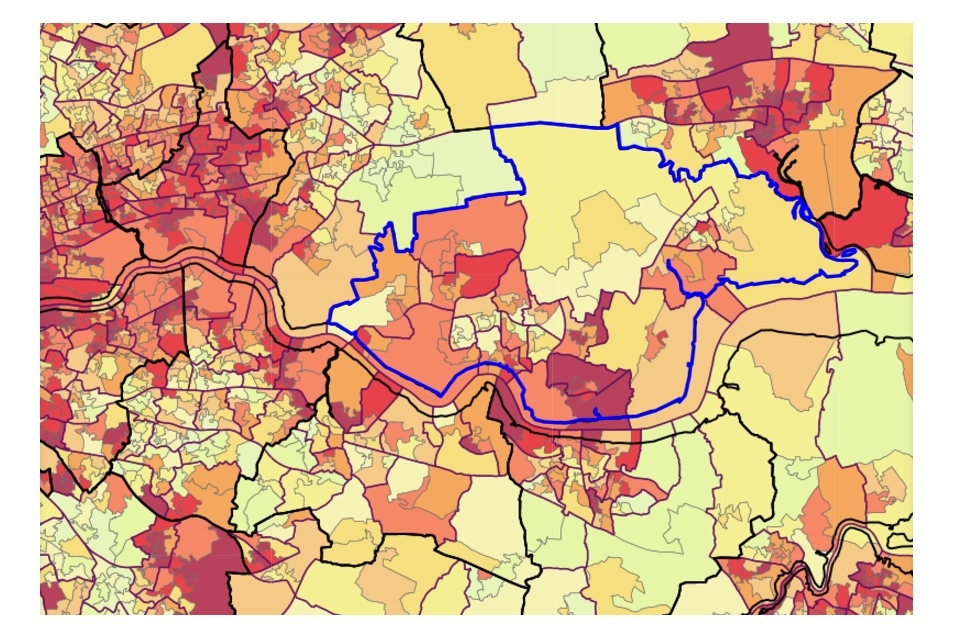

Figure 2: Mapping strategic alignment. Photo credit: Ben Lee/Shared Intelligence

Local Plan

Local Plans set out a vision and a framework for the future development of the area, addressing needs and opportunities in relation to housing, the economy, community facilities and infrastructure – as well as a basis for safeguarding the environment, adapting to climate change and securing good design.

They are also a critical tool in guiding decisions about individual development proposals, as Local Plans (together with any neighbourhood plans that have been brought into force) are the starting-point for considering whether applications can be approved. You will need to consider them when considering where future demand for library services will be located.

Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA)

Local JSNAs are prepared by the Health and Wellbeing Board and published on top-tier council websites each year. They describe what’s being done to support health and wellbeing strategies based on the demographics they cover. This include a wide range of data on current and future health needs of the local population, outlining what work is, or will be, commissioned to help tackle them.

JSNAs are a particularly strong piece of data to base your work on, as they will have already secured agreement from key stakeholders. If you’re in a two-tier area, this will include your local district councils, as well as any clinical commissioning groups and other statutory service providers. This means there is a consensus about the issues the area faces, and that services targeting activity based on this will all be aligned. Because they look to the future, as well as mapping existing need, basing your plan on JSNA data will help to future proof it.

Public Health England’s data and analysis tools may also be helpful. Talk to your public health teams for more advice on targeting and evaluation of health-related library activities, or about the health needs of your local residents. Libraries are very well placed to deliver on public health outcomes, and many services have been commissioned to do this by their public health team. So it is important that you have considered how your service can do so.

Case study: Norfolk library service

Almost two thirds (65.7%) of the adult population of Norfolk are overweight or obese and instances are increasing among the child population of Norfolk. They have one of the lowest levels of childhood activity in the East of England (49.7%). In addition, an estimated 16,400 people in Norfolk have dementia (diagnosed or undiagnosed).

Dealing with these conditions costs local Public Health an estimated £19 million every year.

By focusing the work of the library teams on their public health goal, and targeting their activities based on the local JSNA, Norfolk Libraries are making a tangible difference to the health of their residents and reaffirming the place of the library at the heart of a health community.

Norfolk library staff have been trained to understand health improvement, nutrition, and mental health first aid. They can also offer information, advice and guidance on local health services. Between May 2015 and April 2016, over 2,000 Norfolk residents participated in a dedicated health-based activity under the programme.

School readiness and other educational attainment data

Libraries have a fundamental role in supporting local education provision, promoting literacy, and providing access to the subject information needed to help students to excel in their studies. Your council schools service will hold key information about educational attainment in your area, but you may find it quicker to source the specific information you need on the Department for Education website or by looking through the datasets held on LG Inform and LG Inform Plus (requires a subscription). Some examples of educational and literacy datasets are also included in Annex B.

7.4 Evidence held by others

CIPFA

CIPFA collect and publish annually some core library statistics (these are behind a paywall). The comparative profiles (funded by DCMS) allow for some basic benchmarking with neighbouring authorities. However, not all councils make a CIPFA return and the dataset doesn’t include data covering all library activity, nor service impact measures.

LG Inform and the single data list

LG Inform has over 4,500 data items about a local area from more than 200 data collections all in one tool, and this is growing. The government’s Single Data List contains all of the information that local government must provide to central government, so this information should be available from council data teams. Councils can also use the Libraries Taskforce core dataset.

National surveys

There are 2 national surveys into the ways that the public use and view libraries, which can help frame a narrative. The Carnegie UK Trust published a comprehensive study (April 2017) into library usage in England and the devolved administrations. DCMS run a Taking Part survey, covering England only, which is published annually. It comprises a household survey of adults aged 16 and over and also children aged 5 - 15 years old. Both these need to be used alongside local data.

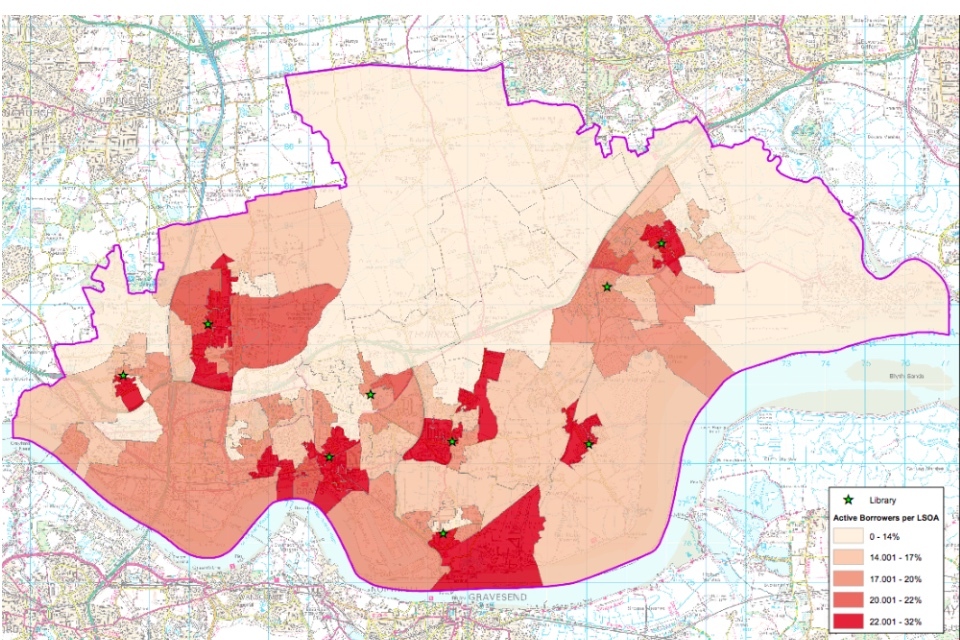

Audience Finder is a free national audience data and development tool, enabling cultural organisations to understand, compare and apply audience insight. Its data is similar to Taking Part, and is available at a local level. Individual councils can send in their postcode data either for an entire library service user-base or individual initiative. This has been used effectively in St Helens and Peterborough.

In addition, Evidencing Libraries Audience Reach: research findings and analysis by the Audience Agency aims to understand the reach of public libraries, and the way in which audience research and data are accessed and used by library practitioners.

National or local charities may also hold information that is useful, particularly in the health sector. For instance, Age UK’s Loneliness Maps 2016 have been referenced in a number of JSNAs.

Digital inclusion and skills levels

Digital inclusion and increasing digital skills levels are very important to councils, and the wider economy. Enabling residents to use public services online, rather than through a contact centre or help desk, provides councils with significant extra flexibility and reduces costs. Information about digital literacy and skills levels are available in Annex B and in the data tools in Annex C. These include a survey that asks residents a number of questions about their digital skills, including ability to use a search engine, use an online payment facility, and send an e-mail.

You may also wish to look at the digital exclusion heatmap as a useful guide to identifying the extent to which digital exclusion is an acute issue in your area.

Economic data

There is a wealth of economic data available and what you need to look at will depend on your local needs. We have identified some of the most common items in Annex B. However, you will also want to look at local priorities. Many councils publish local economic plans, which will identify what they have identified as corporate economic priorities. You may also want to look at key issues identified by your local enterprise partnership and/or Growth Hub (although these tend to operate at a very strategic level). More detailed local data may be held by the local Chamber of Commerce or local branch of the Federation of Small Businesses.

Economic data can be about boosting local growth, particularly small businesses and start-ups, as well as about ensuring the local workforce has the skills needed to participate fully in the economy. For one, you might look at the number of start-ups and their success rate in your area, while for the other you might look at Jobseeker Allowance (JSA) claimant rates - both are listed in Annex B. You may choose to focus on one or the other, or both.

Case study: The Glass Box, Somerset Libraries