Final report

Published 26 February 2024

Background

The CMA launched its housebuilding market study on 28 February 2023, at which point it also issued a Statement of Scope for consultation. The document identified the purpose and proposed themes to be explored in the market study and outlined the CMA’s intended approach to evidence-gathering. Submissions were also invited on the topics raised.

Since then, we have gathered information from various sources, met with stakeholders, and released several interim publications, including:

-

an interim update report and decision on whether to consult on making a market investigation reference in August 2023

-

working papers covering the private management of public amenities on housing estates, land banks, and planning in November 2023

Rationale for the launch of our study

Housebuilding, in some form, has been at the forefront of government policy since the end of the Second World War and has been closely scrutinised in numerous research papers and reviews by academics and others.

The UK government set a target in its 2019 manifesto to deliver 300,000 homes (in England) per year by the mid-2020s and at least a million more homes by the end of the 2019 Parliament. These targets have so far not been met, with concerns about whether they are attainable and/or can adequately meet future needs and demands.

The Secretary of State for the Department of Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) wrote to the CMA in 2022 supporting a study into the housebuilding sector, highlighting the importance of ensuring that the housebuilding market is working in the best interests of consumers. The CMA received further calls from members of parliament and industry bodies to carry out a review of the market. Taking these views into account, and applying our prioritisation principles, the CMA Board decided that it was timely to launch a market study into housebuilding in England, Scotland, and Wales. Our Statement of Scope set out that the study would consider the supply of new homes to consumers in England, Scotland, and Wales. Given differences in the structure and functioning of the housebuilding sector in Northern Ireland, we considered that NI was unlikely to face the same market or supply-side issues as the rest of the UK; we therefore excluded NI from the scope of the market study.

The focus of our work

We have gathered and analysed a range of evidence to enable us to:

-

provide an overview of how the market is structured, the main models of housing delivery in GB, the relationships between key participants, and other aspects of the way the industry operates, at each key stage of the housebuilding process

-

discuss the outcomes that are delivered in relation to the supply and affordability of new homes, the profitability of the largest housebuilders, and the extent to which innovation in the market is occurring, in particular to improve its sustainability

-

explore the extent to which various drivers contribute to the outcomes that we observe in the housebuilding market. We seek to measure, where possible, whether and to what extent any of the competition issues that we identify may lead to consumer harm, by looking at drivers of prices and build-out speed, the nature and operation of the planning system, and drivers of quality and innovation in the sector

-

outline our proposals to address issues we have found during the market study and consider options to improve market outcomes within the current framework. We also identify concerns about the planning system of GB nations and detail possible options for reform

Methods of engagement

Since launching the market study, the CMA has collated information from and discussed issues with a range of stakeholders across the different parts of England, Scotland, and Wales to get an understanding of the challenges facing different regions.

Specifically, we have:

-

sent requests for information (RFIs) to the 11 largest housebuilders, to 52 land agents and promoters, to 55 SME housebuilders, and to 15 estate management companies, allowing us to gain access to information not available to others who have studied this market

-

engaged with a range of government bodies across England, Scotland, and Wales tasked with forming and delivering policy in this area

-

procured planning data from a specialist supplier

-

procured an independent research agency to carry out qualitative research with a sample of 100 owner-occupiers of new build homes, with a focus on understanding their expectations and experiences of the quality of their properties (50 interviews), or their experiences of estate management charges where these apply (50 interviews)

-

held 4 roundtable sessions involving diverse stakeholder representation from the industry on matters relating to quality and planning in each of England, Scotland, and Wales. Roundtable attendees involved: local authorities, housebuilders, and various representative bodies (including trade associations, consumer groups, and associations representing planning and housing officers and local authorities)

We have also received responses to our working papers, including 90 responses from organisations and over 170 individual responses, largely from owners of new build properties.

Scope of our study

The focus of our market study is the supply of new homes to consumers (‘housebuilding’) in England, Scotland, and Wales.

From engaging with various stakeholders in Northern Ireland and undertaking desk research, we identified that the housebuilding sector in Northern Ireland demonstrates notable disparities in market structure and functioning compared with England, Scotland, and Wales. In particular, these are that: the largest 11 GB housebuilders do not operate there, and Northern Ireland is served entirely by SME builders; the pace of housebuilding has been significantly higher than in the rest of the UK; affordable housing is largely funded directly rather than using developer contributions; and estate management with regard to new roads takes place on a different basis.

Due to these significant differences in dynamics and outcomes, a number of the concerns we sought to examine in the course of our study do not appear applicable here. As a result, we decided to exclude Northern Ireland from the geographic scope of the market in this study.

The statutory 12-month timetable for market studies imposed certain limitations on the scope of our investigation. We therefore sought to identify aspects of the housebuilding market where we could offer significant insights and have the greatest impact.

The area of housebuilding touches on important policy objectives that involve wider social and economic policy concerns, beyond the CMA’s core focus on whether the market is working well for consumers. Accordingly, we scoped our study so that we have not considered issues such as:

-

the validity of the actual targets set by governments across GB and whether GB is building enough homes to meet demand

-

the constraints on new homes supply resulting from broad policy choices that weigh various costs and benefits to society, such as the preservation of green belts

-

the fundamental aims of the GB planning regimes, including the way in which they seek to balance housing needs and other societal needs

Our approach to the final report

This document constitutes the final report of the CMA’s housebuilding market study, setting out our overall findings and conclusions, as well as our final decision on whether to make a market investigation reference in relation to this market.

In addition, we are publishing a supplementary supporting evidence document containing in-depth information. Appendices A – K cover technical areas.

Market overview

Summary

Housebuilding in GB, as in many other countries, involves developers identifying a desired location, acquiring land, and navigating a legislative and regulatory framework in order to construct homes and bring them to market.

The majority of new homes in GB are delivered through the ‘speculative model’ of housebuilding (over 60% in 2021/22), whereby housebuilders buy land in advance of the construction and sale of homes, for profit, and without knowing the final price they will sell that home for.

Around a third of homes are built on an affordable housing basis (c.30% in 2021/22), meaning they are sold or rented at a discount to the market price. The construction of these homes is typically either funded and procured by a public body, local government, or registered housing provider, or provided by housebuilders via planning obligations. As a proportion of total builds, England has relatively more speculative housing, and Scotland and Wales have relatively more affordable housing.

The largest 11 housebuilders provide a significant proportion of homes in GB (around 40% in 2021 to 2022), operating mainly, but not exclusively, through the speculative model. Large housebuilders develop a range of sites, whether greenfield, brownfield, rural or urban, with a wide geographic spread, although they tend to focus on larger developments.

Our analysis suggests there are currently thousands of SME housebuilders in England, Scotland, and Wales, who according to our data are building in excess of 50,000 houses in total each year. SMEs also cover a range of sites but tend to focus on smaller developments. The number of SME housebuilders is reported to have fallen significantly since the late 1980s.

Landowners, intermediaries who support transactions between landowners and housebuilders, providers of warranties for new homes (similar to insurance), and estate management companies are also participants in the market.

Housing policy is a devolved matter. In England, the Department of Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) is the lead policy department. The Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) and the Department for Transport (DfT) have responsibility for sewers and drainage and roads on new build estates, respectively.

The Scottish and Welsh governments have policy responsibility for the range of areas within housing policy in these nations.

Local government plays an important role, with Local Planning Authorities (LPAs) leading planning activities and decisions in local areas and bringing forward social housing, and local authorities (as well as other relevant authorities) having power to adopt infrastructure and amenities constructed by housebuilders.

A number of public bodies such as Homes England, the Planning Inspectorate, HM Land Registry, and statutory consultees to the planning process (such as Natural England, the Environment Agency, and others) also play a role.

In this chapter we describe the key features of the housebuilding market[footnote 1] in England, Scotland, and Wales in order to provide the background and building blocks for subsequent chapters focused on analysis and recommendations.

This chapter therefore discusses:

-

the process of bringing new homes to market

-

the main models of housing delivery in GB

-

the key market participants

-

the role of government and public bodies

How houses are brought to market

The activity of supplying new homes in GB, as in other countries, is not as simple as buying a plot of land, starting construction, and then putting them on the market.

Housebuilders instead operate through a series of legislative and regulatory frameworks which are in place with the aim of managing a range of social and policy objectives, which we describe later in our report as they become relevant.

In this section, we set out the main phases that housebuilders go through while developing a plot of land into new, saleable homes.

The development process

The development process broadly consists of a number of phases:[footnote 2]

-

pre-planning, typically involving: site identification and appraisal; securing target sites under contract (usually through an option agreement); initial site design and master planning; site promotion for allocation in local plan; and pre-application discussions with local planning authorities (LPAs) and other stakeholders

-

planning application to planning permission, typically involving: final preparation of planning applications; submission of the planning applications to the LPA for validation; statutory and non-statutory consultation for a minimum of 21 days; negotiation of planning conditions and planning obligations; recommended decision on planning applications by planning officers; final decision on planning application by planning committee; and (where this occurs) an appeal of a planning decision to the Planning Inspectorate (or in some cases a judicial review of the planning decision)

-

planning permission to start on site, typically involving: final acquisition of permissioned land from landowner/land promoter; discharge of planning conditions; pre-commencement orders/reserved matters; assembly of labour and construction materials; and ground works, site access, and installation of enabling infrastructure

-

construction, typically involving: build commencement; marketing and initial sales release; phasing development; build complete. Within this stage, consumers may have moved in which initiates the snagging and aftercare processes

-

post-construction, typically involving: sales completion; adoption of amenities, such as roads, sewers and drains, or transfer of land and management of amenities to a residents’ management company (RMC) or private management company.[footnote 3] Consumer aftercare is provided by the housebuilder and warranty providers for a period of time

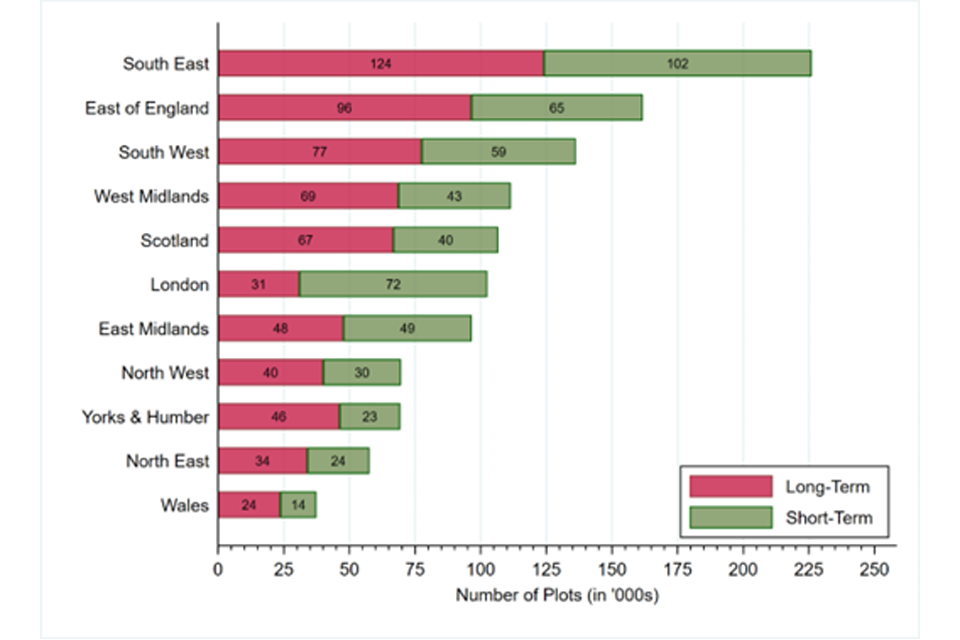

How land is sold

Land is clearly an essential input required by housebuilders to deliver homes. Finding the right plots, where people want to live, where there is - or can be - appropriate infrastructure, and where they are likely to get planning approval is a key part of the housebuilding process.

Housebuilders may purchase or control residential land with:

-

no planning permission (known as long-term or strategic land). For this type of land, a housebuilder must first obtain planning permission to begin construction of a residential development

-

at least outline planning permission (known as short-term or permissioned land). For this type of land, the housebuilder will be able to begin construction of the residential development relatively quickly

Land can either be brownfield (previously developed) or greenfield (previously undeveloped).

Housebuilders use the Red Book, voluntary guidance published by the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS), to value the land which they plan to develop.[footnote 4] Land agents also provide land valuations to landowners, but this is provided as a guide for marketing purposes. Land can be valued either through direct comparison with other recent sales (where data on sufficiently similar transactions is available) or through residual valuation, where the land value (in other words, the ‘residual’) is the completed gross development value (how much the properties on the land would sell for) minus total development costs, government policy and obligation costs (for example, Section 106 contributions), and developer’s profit.

Land can be sold either through on-market (in other words, publicly advertised) or off-market (inother words, private transactions not publicly advertised) processes. The negotiation process between the seller and purchaser is typically one of the following:

-

bilateral negotiation: this is a one-to-one negotiation between the buyer and the seller

-

limited tender: a select list of potential purchasers are invited by the landowner (and/or their appointed agent) to bid for the land

-

open market: any bidder can bid for the land

The main models of housing delivery in GB

There are several models by which housing has been delivered across GB and other countries in recent decades. These models vary by how much involvement the eventual buyer, or a state or private developer, has in the construction process, and in terms of the kind of end-user envisaged for the dwelling.

The main models used to deliver housing in GB are:

-

speculative housebuilding – housebuilders buy land in advance of the construction and sale of homes. The price at which the homes are to be sold is uncertain at the time of the land purchase and will not be determined until the homes are sold to a final consumer, which can be late on in the development process. As with most market transactions, the builder is motivated primarily by the desire to earn a commercial return on the project

-

affordable housing/sub-market – this is housing that is typically sold or rented at a discount to market prices. Several different types of housing fall into this category, including social rented housing; affordable or intermediate rented homes; and discounted or subsidised sales of homes. The construction of these homes is, typically, either funded and procured by a public body (such as Homes England or an LPA) or a Registered Housing Provider, or provided by housebuilders via planning obligations that form part of the planning permissions obtained for developments

-

build to rent housing – purpose-built housing that is typically 100% rented out. These types of build to rent developments will usually offer longer tenancy agreements of 3 years or more and will typically be professionally managed rental stock in single ownership and management control

-

custom build/Self-commissioned housing – housing built by an individual, a group of individuals, or persons working with or for them, to be occupied by them. Such housing can be either market or affordable housing

Our analysis suggests that around 141,000 (around 60%) of the 239,000 new build homes completed in GB in 2021 to 2022 were built though the speculative model, although we note this is approximate given the different data sources used

Figure 2.1: Estimated number of homes built in GB using various models in 2021 to 2022

Alt text

A pie chart showing the number of homes built under various models of housebuilding in GB in 2021 to 2022.

The numbers are: speculative housing 141,600; affordable housing 71,600; custom build housing 15,900; and build to rent housing 12,300.

Sources: CMA analysis of

-

New data shows custom and self build numbers growing (nacsba.org.uk)

-

Live table 1000 Additional affordable homes provided by tenure, England

-

Additional affordable housing provision by provider and year (gov.wales)

Note: Figures may not sum due to rounding. Note: Figures for custom build housing are for 2019.

We see a higher proportion of speculative housebuilding in England than in Scotland or Wales, due to England having a lower proportion of affordable/social housing. In England, affordable housing accounted for around 29% of completions in 2021 to 2022, compared with 45% and 50% for Scotland and Wales respectively.

Key market participants

A range of market participants are involved in the supply and related activities regarding new build housing in GB. This includes housebuilders (who differ significantly by size and other characteristics such as geographic scope), landowners, intermediaries of various kinds, warranty providers, and estate management companies.

Large housebuilders

Large housebuilders, also known as volume housebuilders, are key players in the GB housing market.

For the purposes of this study, we define large housebuilders as those building more than 1,000 homes a year. Our analysis of NHBC data suggests that around 25 housebuilders built more than 1,000 homes in 2022, although this may be an underestimate.[footnote 5] For the purposes of our analysis, we have particularly gathered information from a subset of these: the 11 largest housebuilders in Great Britain, by 2020 to 2021 and 2021 to 2022 revenue. Each of these housebuilders built more than 2,000 homes in 2021-22.[footnote 6] These firms are: Barratt, Bellway, Berkeley, Bloor Homes, Cala, Crest Nicholson, Miller Homes, Persimmon, Redrow, Taylor Wimpey, and Vistry.[footnote 7]

These large housebuilders mainly build under the speculative model outlined above, but typically a significant minority of their output will be affordable homes. 8 of these firms are UK-listed and, since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), have been largely equity-financed to allow them to better manage risk.

Large housebuilders develop a variety of sites, including greenfield and brownfield sites, and rural and urban sites. They tend to focus on larger developments, and generally have a relatively wide geographic spread, which allows them to diversify exposure to local risks.

According to our estimates, in 2021 to 2022 the single largest builder, Barratt, supplied around 8% of the GB market. The largest 11 firms together supplied around 40%.[footnote 8]

Figure 2.2: GB shares of housebuilding 2021 to 2022

Alt text

A pie chart showing shares of new-build housing in 2021 to 2022.

The shares are: Barratt 8%; Bellway 5%; Persimmon 6%; Taylor Wimpey 6%; other top 11 housebuilders 15%; and other builders 61%.

Sources: CMA analysis of:

-

various large housebuilders’ annual reports and accounts and government statistics; Housing supply: net additional dwellings - GOV.UK

-

Housing statistics quarterly update: new housebuilding and affordable housing supply (gov.scot)

SME housebuilders

SME housebuilders also play a significant role in housing delivery in GB. For the purposes of this market study, we define SME housebuilders as any housebuilder building 1,000 houses or fewer per year.[footnote 9]

Our analysis suggests there are currently thousands of SME housebuilders in England, Scotland, and Wales, who according to our data are building in excess of 50,000 houses in total each year.[footnote 10] The number of SME housebuilders is reported to have fallen significantly since the late 1980s.[footnote 11]

SMEs develop a variety of types of site, including greenfield and brownfield sites, and rural and urban sites. They also develop a range of sizes of site, including smaller sites which larger housebuilders may not develop.

SMEs build a variety of houses, with some utilising standardised house types, and others building more bespoke homes.

Unlike large housebuilders, SMEs typically use external debt financing, either on a project-by-project bases or through longer-term finance. This means SMEs cannot hold land banks in the same way as the large housebuilders can due to their access to equity or other external finance.

Landowners

Landowners are private individuals, public entities, commercial entities, charities, or institutional landowners who own land and may be willing to sell it for housing development. There is no single comprehensive set of data on who owns what proportion of land across Great Britain. However, some estimates suggest around 60% of land in England and Wales is owned by private individuals, with a range of institutions such as the Forestry Commission, Ministry of Defence, and the Crown Estate also holding significant amounts of land for different purposes.[footnote 12]

Intermediaries

There are intermediary actors in the market which support landowners when they seek to sell or develop their land. Most commonly these are solicitors, land agents, and land promoters. The interactions these actors have with landowners are usually dependent on what the owner wants to do with their land.

Land agents are individuals or firms who specialise in representing clients (buyers or sellers) in land transactions. They support the sale, purchase, or leasing of land.

Based on the land agents’ completed sales data,[footnote 13] we found the largest land agents were Savills (approximately [redacted]% of sites, equivalent to [redacted]% of plots in 2022),[footnote 14] with multiple agents holding a share of more than 5% of sites and plots and several more with shares below 5% in 2022.

Land promoters’ main activity is promoting land through the planning system on behalf of landowners, with the objective of securing planning permission for residential development. Land promoters have been active in the strategic land market for decades, but the GFC is reported to have stimulated the expansion of this model since 2008.[footnote 15]

Based on land promoter completed sales data,[footnote 16] we found Gladman was typically the largest promoter each year (approximately [redacted]% of sites, equivalent to [redacted]% of plots). Based on sites, the other promoters are smaller and do not have a consistently high share for each year, indicating that sales from promoters may be volatile. Based on plots, there is more variation in the relative size of land promoters, which may be due to the sale of larger sites with more plots in particular years.

Warranty providers

A new build warranty is an insurance product for a newly-built home. The warranty is taken out by the housebuilder, with the beneficiary of protection being the buyer and mortgage lender, if applicable. It typically covers defects that arise due to faults in design, workmanship, or materials that remain undiscovered at the time of completion of the new build.[footnote 17] There is a range of warranty providers: well-known ones are NHBC, Local Authority Building Control (LABC), and Premier Guarantee.

Currently, the period of coverage is usually 10 years and housebuilders are not required by law to provide a warranty; instead, the majority of mortgage lenders make provision of one a requirement for lending.[footnote 18] The Building Safety Act 2022 has provisions to make it mandatory for housebuilders to provide a warranty to the purchaser, with a minimum period of coverage of 15 years.[footnote 19] These provisions are not yet fully in force, although are expected to come into force in the near future.

Estate management companies

Estate management companies, which include some property factors in Scotland, provide services to households on housing estates for the ongoing management and maintenance of public amenities such as open spaces, roads, drainage and sewers, and sustainable drainage systems (SuDS), where those amenities have not been adopted by the relevant public authority.

They may specialise in the provision of estate management services in general or in the provision of estate management services for specific amenities such as public open spaces, and they may offer estate management services as part of a wider portfolio including, for example, block management for leasehold customers.

The role of government and public bodies

As noted above, housebuilding operates in an environment heavily influenced by governments and public bodies, and the legal and regulatory frameworks they set and operate. In this section we set out the key responsibilities and features in this regard.

Policy responsibility

Housing policy, including policy on planning, consumer protection with regards to housing, and other relevant policy areas such as specific environmental policies and energy efficiency policy, is devolved. Therefore, governments across GB are responsible for policies which impact the issues considered in this market study.

England

The UK government is responsible for housebuilding in England. The lead policy department is the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC). DLUHC’s work includes investing in areas to drive growth and create jobs, delivering the homes the country needs, supporting community and faith groups, and overseeing local government, planning, and building safety.

DLUHC is responsible for housing, which includes a broad range of activities in homeownership, leasehold, the private rented sector, social housing, housing delivery, building safety and Net Zero. Planning is also a key responsibility: DLUHC is responsible for the production of the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), a document that sets out the UK government’s economic, environmental, and social planning policies for England. The NPPF covers a wide range of topics, including housing, business, economic development, transport, and the natural environment.

In relation to estate management, DLUHC has policy responsibility for leasehold and freehold matters, and is implementing reforms through the Leasehold and Freehold Reform Bill.

In relation to the adoption of amenities, the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) has policy responsibility for sewers and drains under the Water Industry Act 1991 and sustainable drainage systems (SuDS) under the Flood and Water Management Act 2010. In relation to roads, the Department for Transport (DfT) has policy responsibility under the Highways Act 1980.

Scotland

The Scottish Government has responsibility for housing policy in Scotland. It also has responsibility for the production of the National Planning Framework, a document that acts as the national spatial strategy for Scotland, as well as setting out Scotland’s spatial principles, regional priorities, national developments, and national planning policy.

Policy responsibility for estate management and roads is also devolved in Scotland. In relation to estate management, the Scottish Government sets out its policy for property factors in Scotland under the Property Factors (Scotland) Act 2011.

In relation to adoption, the Scottish Government sets out the policy for roads under the Roads (Scotland) Act 1984, and sewers and SuDS under the Sewerage (Scotland) Act 1968.

Wales

The Welsh Government has responsibility for housing policy in Wales. It also has responsibility for preparing Planning Policy Wales (PPW), the document that sets out the land use planning policies of the Welsh Government.

PPW is supplemented by a series of Technical Advice Notes, Welsh Government Circulars, and policy clarification letters, which together with PPW provide the national planning policy framework for Wales. The primary objective of PPW is to ensure that the planning system contributes towards the delivery of sustainable development and improves the social, economic, environmental, and cultural well-being of Wales, as required by the Planning (Wales) Act 2015 and the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015.

In relation to estate management, in November 2023, the Minister for Climate Change stated that she will be laying a Legislative Consent Memorandum in respect of the Leasehold and Freehold Reform Bill, given housing is within the legislative competence of the Senedd.[footnote 20]

In relation to adoption, the Water Industry Act 1991 covers the adoption of sewers and drains. Welsh Ministers have published standards related to the mandatory adoption of sewers and lateral drains under the Flood and Water Management Act 2010. The adoption of SuDS is governed by the Flood and Water Management Act 2010 (Schedule 3). Adoption of roads is covered by the Highways Act 1980.

Local government

Local planning authorities (LPAs)

The planning system is designed to be applied by local government and communities across all 3 GB nations. Local government administers much of the planning system, preparing local plans, determining planning applications, and carrying out enforcement against unauthorised development.

An LPA is the local government body that is empowered by law to exercise planning functions for a particular area.

Mayor of London and the Greater London Authority (GLA)

The Mayor of London and the GLA have joint responsibility for planning with the London boroughs. The GLA sets out a spatial development strategy for London in the form of the London Plan and related polices. It also sets London’s housing targets. Strategic planning applications are referred to the Mayor for comment and the Mayor also has power to ‘call in’ planning applications in certain circumstances.

Greater Manchester and the West Midlands Mayors

Similar to the London Mayor, the Mayor of Manchester and Greater Manchester Combined Authority have planning powers and are developing a planning spatial strategy for the region, barring Stockport Council. The Mayor of Manchester has no powers to ‘call in’ strategic applications.

Contrary to London and Manchester, the Mayor of the West Midlands and West Midlands Combined Authority work with constituent and non-constituent members on spatial planning and redevelopment of brownfield land, including use of compulsory purchasing powers to acquire land. However, formal planning powers rest primarily with individual local councils.

Both Greater Manchester and the West Midlands also have various transport and housing powers, among others.

Public bodies and statutory consultees

Public bodies play different roles across the housebuilding process. The main ones are Homes England, the Planning Inspectorate, and HM Land Registry.

Homes England

Homes England is an executive non-departmental public body, sponsored by DLUHC. It is the UK government’s housing and regeneration agency working across England only, except in London where much of the agency’s role is devolved to the London Mayor. Its role is to improve the supply and quality of housing in England.

Planning Inspectorate

The Planning Inspectorate is an executive agency sponsored by DLUHC. It deals with planning appeals, national infrastructure planning applications, examinations of local plans, and other planning-related and specialist casework in England.[footnote 21]

HM Land Registry

HM Land Registry is a non-ministerial department which registers the ownership of land and property in England and Wales.[footnote 22]

Statutory Consultees

Statutory consultees are organisations that are required by legislation to be consulted on plans and applications. They play an important check-and-balance role within planning systems, safeguarding the environment, respecting heritage, and ensuring health and safety considerations are properly considered in the production of Local Plans and in determining planning applications. Such organisations include Natural England, Nature Scot, Natural Resources Wales, the Environment Agency, Historic England, Cadw, Historic Environment Scotland and the Health and Safety Executive, among others.

Market outcomes

Summary

The housebuilding market is not delivering well for consumers. In particular, we see:

Supply of new homes across GB persistently falling well short of government targets and other assessments of need, as well as being highly cyclical. As this happens over many years, it compounds to create a growing housing shortfall, which puts increasing pressure on housing affordability. Looking back at the history of this market, it is notable that housebuilding has only reached the desired levels in periods where significant supply was provided via local authority building.

Below the GB level, significant variation in housing delivery relative to need. Scotland has, in general, come closer to its implied target levels than Wales and, in particular, England. There is also variation by region, with regions of England (London, South East and East) accounting for the majority of the areas where there has been significant under-delivery against assessed need, and some local authority areas in Scotland and Wales also delivering less than their assessed level of need.

The ability for firms to earn profits in excess of the cost of capital over an extended period. Our analysis has found that during the 2010s, average housebuilder profitability was well in excess of the cost of capital, although this was preceded by a period in which the reverse was true, and was partially driven by external factors such as ultra-low interest rates and the Help to Buy scheme. We therefore do not take this to indicate that intervention is required to directly tackle housebuilder profitability.

Problems faced by some purchasers of new homes in relation to the prevalence of defects, and the effectiveness with which they are rectified. Although buyers’ reported satisfaction at 8 weeks after completion is generally high, there is some evidence that customers’ perceptions of the quality of service they had received (or in some cases were still receiving) deteriorated as they lived in their homes for longer. In particular, where consumers experience a greater number of snags or faults it can be more difficult to resolve them, taking weeks or even months. It also appears that there is a small but significant minority experiencing the most serious defects, who are likely to experience significant consumer detriment.

Lower levels of innovation in the industry than we might expect in a dynamic, well-functioning market. Although many of the largest builders have invested in, acquired, or developed their own more innovative production capacity, the dissemination of these new methods continues to happen at a slow pace. Efforts at improving sustainability are primarily driven by expectations of future regulation, rather than industry momentum.

Consumer detriment arising from the private management of public amenities on housing estates. We conclude that, as a result of the proliferation of this model, and with some households unable to switch provider at all, households may face detriment in the form of the charges they pay, the quality of amenities available to them and the quality of management services they receive, the potential for disproportionate sanctions to be applied for outstanding charges, and the sometimes significant efforts required to achieve a satisfactory outcome in those regards. We consider that if the status quo is maintained, aggregate detriment is likely to worsen over time.

Introduction

In market studies, we explore the outcomes that are being delivered by a market, so that we can assess how well it is working for consumers, and areas where it may be falling short.

In this chapter, we discuss our findings in relation to the following outcomes:

- the supply of new build homes, and the affordability of homes more broadly

- the profitability of the largest housebuilders

- the quality of the new homes being delivered, and consumers’ experiences of seeking redress when things go wrong

- the extent to which the market is innovating, including to improve its sustainability

- the increasing use of private models for managing the public amenities on new estates, and the impact this is having on consumers

In the Statement of Scope for our housebuilding study we set out that we would also examine the extent to which the market delivers adequate choice of new build homes; we explore this in our discussion of how housebuilders decide build-out rates and prices at paragraph 4.105 onwards. We also said that we would seek to understand the role of SME housebuilders in driving quality and innovation; we report our findings in respect of that question in paragraph 4.185 onwards.

Supply and affordability

Fundamental to whether the housebuilding market is delivering good outcomes for consumers is whether it is producing an adequate quantity of new housing. The quantity of housing that is supplied to the market depends on a range of factors, including decisions made by housebuilders; government policy (such as housebuilding targets or government housebuilding programmes); broader macroeconomic conditions; the planning system and how well it functions; how effectively the markets for the supply of land and housing are working; and natural constraints such as the quantum of developable land in places where people want to live. While observations about how much new build housing is being delivered may not directly tell us how well the market, and competition within it, is working, nevertheless it is an important step in understanding whether we should be concerned about how the market is delivering for consumers.

In considering the adequacy of supply in the housing market it is important to distinguish between housing demand and housing need. While housing demand is determined by the number of people or organisations willing and financially able to buy a property, either as a home, second home or investment property, housing need is determined by the amount of housing required for all households to live in accommodation that meets a certain normative standard. As such, estimates of housing need inevitably reflect views about what acceptable standards look like, which are ultimately for wider society to determine through democratic processes.

One of the primary ways in which housing need is assessed is through setting government targets. The different nations of GB have different approaches to estimating housing need.

-

in England, there is a government commitment to deliver 300,000 new houses per year by the middle of the decade. Alongside this, LPAs must conduct a local housing need assessment through the Standard Method (SM). The current version of the SM introduced changes to help ensure that it ‘delivers a number nationally that is consistent with the commitment to plan for the delivery of 300,000 new homes a year’[footnote 23]

-

in Scotland, LPAs must set out their Local Housing Land Requirement for the area they cover. This is expected to exceed the 10-year Minimum All Tenure Housing Land Requirement (MATHLR). The sum of the MATHLR targets set out in Annex E of NPF4 equates to land for 20,000 homes per year[footnote 24]

-

in Wales, LPAs must explain how they will ensure that their housing requirement and associated land supply will be delivered in their local development plan. While there is no officially set target, work published by the Welsh Government in August 2020 provided a central estimate of annual all-tenure housing need of 7,400[footnote 25]

We do not intend to provide an assessment of the targets set by governments or test their validity. However, we note that assessing the level of housing need is very challenging, requiring a variety of assumptions around factors such as population growth and current levels of suppressed demand. As such any method is likely to have weaknesses. We set out in Section 2 of the supporting evidence document further detail of critiques which have been made of the different approaches to setting targets in the different nations.

Given the difficulty of assessing housing need and the issues with any given metric used for this purpose, we have therefore also considered other assessments of the level of housebuilding which is needed.[footnote 26] We do not endorse the specific figures produced by any of these papers. However, we note that most find that there is a shortfall in current levels of housing provision, and that the findings of those papers imply the target levels of housebuilding set by government may be a lower bound for what is needed.[footnote 27]

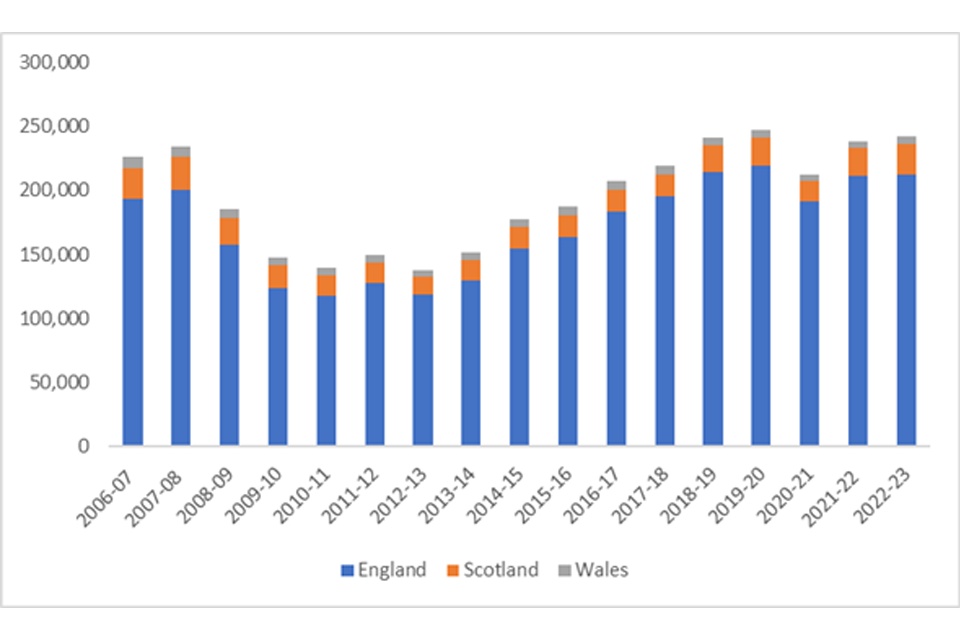

Figure 3.1: New homes built in England, Scotland, and Wales 2006 to 2007, to 2022 to 2023

Alt text

A bar chart showing the number of new homes built in England, Scotland, and Wales between 2006 to 2007, and 2022 to 2023.

The chart shows that housebuilding over this period has been significantly and persistently below 300,000 homes per year across GB.

In England, the volumes of housing delivered annually have increased significantly since the Great Financial Crash but have not exceeded 250,000 at any point during this period.

In Scotland, it has taken some time for the level of new-build completions to return to close to pre-2008 levels (which exceeded 25,000) and were still somewhat short of this at 21,000 in 2021 to 2022.

In Wales, the number of new-build homes completed remains well below its pre-2008 level of around 9,000 and in 2021 to 2022 was less than 6,000.

Sources:

As figure 3.1 above shows, housebuilding over this period has been significantly and persistently below 300,000 homes per year across GB.[footnote 28]

-

in England, the volumes of housing delivered have increased significantly since the GFC but have not exceeded 250,000 at any point during this period

-

in Scotland, it has taken some time for the level of new build completions to return to close to pre-2008 levels (which exceeded 25,000) and are still somewhat short of this at 21,000 in 2021 to 2022. While in some recent years levels of completions have been just above 20,000, over a 10-year period (2012 to 2013, to 2021 to 2022) completions were below this, averaging approximately 17,800

-

in Wales, the number of new build homes completed remains well below its pre-2008 level of around 9,000 and in 2021 to 2022 was less than 6,000. This is also below the level of need estimated by the Welsh Government as described in paragraph 3.6(c)

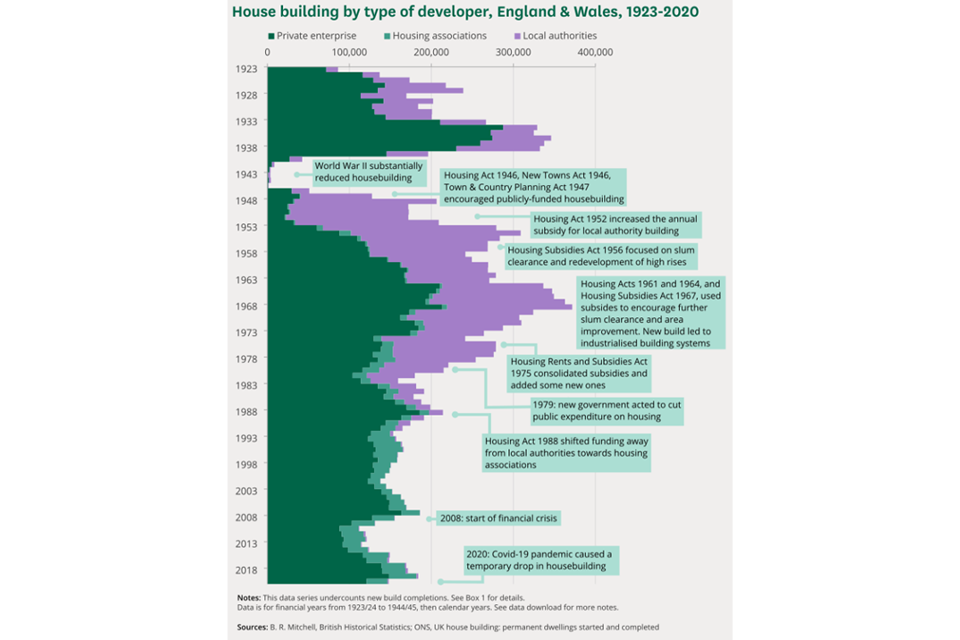

Recent levels of housebuilding are not unusual in the longer historical context. As can be seen from the chart below, the only years when housebuilding in England and Wales approached or exceeded 300,000 homes per year were during periods with significant levels of local authority housebuilding.

Since the Second World War, private developer output has fluctuated between roughly 150,000 and 200,000 per year, according to this data set. It is also highly cyclical in nature, with housing output strongly correlated with changes in macroeconomic outlook. There is some underestimation of new build supply in this dataset, which means we cannot be definitive;[footnote 29] nevertheless, looking over a longer time period shows that private housebuilding alone has rarely, if ever, in the past century delivered close to the amount of housing expected under the current targets.

Figure 3.2: Housebuilding by type of developer, England and Wales, 1923 to 2020

Alt text

A chart showing housebuilding in England and Wales by private enterprises, housing associations and local authorities.

Since the Second World War, private developer housing output has fluctuated between roughly 150,000 and 200,000. Housebuilding by local authorities has declined markedly and, although since the late 1970s the volume of housebuilding by housing associations has increased, this has not been sufficient to outweigh the large drop in volumes provided by local authorities. Private housebuilding is shown to be highly cyclical in nature, with housing output strongly correlated with changes in macroeconomic outlook. Looking over a longer time period shows that private housebuilding alone has rarely, if ever, in the past century delivered close to the amount of housing expected under the current targets according to this data set.

Source:

There are also important local dynamics at play in housing delivery. The same level of housing (and so housebuilding activity) is not required uniformly across the nations and regions of Great Britain.

-

in England, the majority of LPAs in England meet or exceed their local Housing Delivery Test (HDT) targets: 214 (or 70%) of LPAs achieved more than 95% of their housing need in 2020 to 3021[footnote 30] - significant underperformance of housing delivery against targets is limited to a relatively small number of LPAs, and these are relatively highly concentrated in certain areas of the country, particularly in the South East, East of England, and London regions

-

for Scotland, over the last 5 years, in 7 out of 33 LPAs (21%) housing completions were equivalent to 75% or less of their MATHLR assessment of local need, while in 18 (55%) housing completions were in excess of 100% of this - the LPAs scoring below 75% included the most densely populated conurbations in Scotland – Edinburgh and Glasgow[footnote 31]

-

for Wales, over the last 5 years, 13 out of 21 LPAs (62%) achieved housing completions equivalent to 50% or less of their local plan housing requirement whilst none achieved completions in excess of 100% - the high number of LPAs missing their local plan requirements means that they are spread across Wales but amongst the areas with the lowest ratios are the most densely populated areas Cardiff and Swansea[footnote 32]

We have also considered what we can infer from metrics of housing affordability. In addition to supply, affordability is determined by factors such as household size and composition, credit conditions, population growth, and levels of household income. If supply of housing fails to keep pace with changes in demand, we might expect house prices to increase faster than earnings, and so affordability may worsen. In addition, large differences in affordability between areas may indicate the market is not able to fully respond to price signals (for example, consumers being unable to move to areas with greater supply and so lower prices, or housebuilders not being able to expand supply in areas with greater shortages).

A number of measures define affordability to be house prices of around 4 times or 5 times annual incomes. In 2022, full-time employees in England could expect to spend around 8.4 years of income buying a home. This compares with average house price to income ratios of 6.4 in Wales, and 5.3 in Scotland.[footnote 33],[footnote 34] We also see significant regional variation in affordability. Analysis by Nationwide found that in 2021 almost all regions had some areas where affordability ratios were above the level which would be considered affordable, and in the East of England, South East, South West, and London, all LAs had an affordability ratio of 5 or higher.[footnote 35] Data from the ONS for England and Wales shows a similar pattern,[footnote 36] and shows that over the 25 years for which the series is available, affordability has worsened in every LA area. Equivalent data is not available for Scotland.

Considering affordability of rents, ONS uses an affordability threshold of 30% of income (in other words, rent less than 30% of income is considered affordable). Since 2014, the rental affordability ratio for both England and Wales has been below this threshold. However, ONS analysis also indicates that affordability is challenging for those on low incomes and in London, as discussed further in Section 2 of the supporting evidence document. Equivalent data is not available for Scotland.

Clearly, housebuilding is only one factor which will affect affordability, and some studies have indicated that other factors, such as interest rates, taxes, and levels of housing benefit, play an important role.[footnote 37] We therefore cannot attribute changes in affordability solely to the level of housebuilding. In addition, we note that there are limitations with the data used to calculate affordability ratios.[footnote 38] However, worsening affordability, particularly in those parts of the country where housebuilding has been more constrained, is indicative of a market which is not working well.

Conclusions on supply outcomes

Our analysis indicates that the housebuilding sector is not delivering the number of homes which governments and a number of other sources have assessed are needed. At the same time, the affordability of buying a home is increasingly challenging, particularly in highly populated areas. While rents remain more affordable for most of the population, they are more challenging for those on low incomes or in London. In addition, a significant number of people remain in acute need of adequate housing, as demonstrated by the numbers who are homeless, in temporary accommodation or awaiting social housing (as we discuss further in Section 2 of the supporting evidence document).

However, it is important to reiterate that this reflects performance against need rather than demand. Some people will not be able to afford the level of accommodation which normative judgements indicate they need (for example, those on low incomes living in overcrowded accommodation); others will be able to demand well above the level of need (such as those who can afford a second home). Private sector housebuilders are likely to be far more focused on building homes to meet demand rather than need, as demand will determine what and how much they can sell. Demand for housebuilding is strongly influenced by general economic conditions such as interest rates and incomes, and so fluctuates throughout the economic cycle. This is important context for understanding how the market functions, and particularly the incentives on housebuilders to build at different points in time.

Profitability

Introduction

The primary purpose of conducting profitability analysis is to understand whether the levels of profitability (and therefore prices) achieved by suppliers are consistent with the levels we might expect in a competitive market. If supernormal profits (in other words profits above the levels that we would expect in a competitive market) have been sustained over a sufficiently long period of time, this could indicate limitations in competition.

The extent to which the results of profitability analysis indicate limitations in the competitive process may depend on both the size of the gap between the level of profitability and the cost of capital, and the length of the period over which the gap persists. Further, the appropriate time period over which to examine the persistence of the gap between profitability and the cost of capital may vary according to the specific market.

For our methodology and approach in full, please see Profitability Appendix A and Cost of capital Appendix B.

Approach to profitability analysis

As with all of our markets work, we are interested in understanding how the market functions. The CMA’s guidelines for market investigations (CC3 (Revised)) indicate that outcomes such as the profitability of firms provide evidence about its functioning.[footnote 39] We consider that these guidelines are relevant to our profitability analysis in this market study.

The analysis of profitability as a means of understanding competitive conditions in a market is based on the premise that in a competitive market firms would generally earn no more than a ‘normal’ rate of profit. CC3 (Revised)[footnote 40] defines a ‘normal’ level of profit as:

… the minimum level of profits required to keep the factors of production in their current use in the long run, in other words, the rate of return on capital employed for a particular business activity would be equal to the opportunity cost of capital for that activity.

The opportunity cost of capital is the cost of capital which investors expect for providing capital to firms undertaking the activities under investigation. This can be thought of as a market-based return on investment, to compensate investors for providing money to firms in the market.

The rationale for benchmarking return on capital with the opportunity cost of capital is that, in a competitive market, if firms persistently earned in excess of the return required to compensate investors for the risks taken, we would expect these high returns to attract entry and/or expansion. Such entry/expansion would serve to compete away profits in excess of the cost of capital up until the point where firms cover their total costs, including a market-based cost of capital and no more. Where firms persistently earn in excess of a normal return, this therefore signals that there may be limitations in the competitive process.

Our methodology

Profitability

In scoping our profitability analysis, we have considered:

-

the relevant business activities to be: securing land for future development; obtaining planning permission (and putting in place various agreements with the appropriate authorities); and building and then selling homes

-

the relevant firms to be the 12 largest housebuilders operating in GB[footnote 41]

-

the relevant time period to be 20 years from January 2003 to December 2022. The housebuilding market is highly cyclical and impacted by external factors such as the wider economic climate, and so we wanted to understand how the level of profitability changed over a long period

In calculating profitability, we have adopted the following approach:

-

profitability measure: we have used return on capital employed (ROCE) as our measure of return on capital, as this measure can be computed annually and thus provides greater insights into trends over time and the drivers of profitability above the ‘normal’ level

-

potential adjustments to financial information to determine economic profitability:

-

we have excluded items which do not relate to the housebuilders’ operating profits and operating capital employed

-

we have retained the basis of valuation for land that housebuilders adopt in their accounts for our analysis.[footnote 42] We consider that the returns housebuilders have realised in each period through selling homes to new home buyers is the most relevant concept for assessing outturn performance and that valuation basis provides the right foundation for what we are seeking to assess

-

Cost of capital

We have compared the returns made by the 12 largest housebuilders against their opportunity cost of capital, as estimated using the capital asset pricing model (CAPM).[footnote 43] We have estimated the cost of capital of the 12 largest housebuilders over the 20-year period from January 2003 to December 2022 in line with our profitability analysis. We have calculated a range for the cost of capital for each year to reflect changes in macroeconomic conditions over the period.

Results and interpretation of our analysis

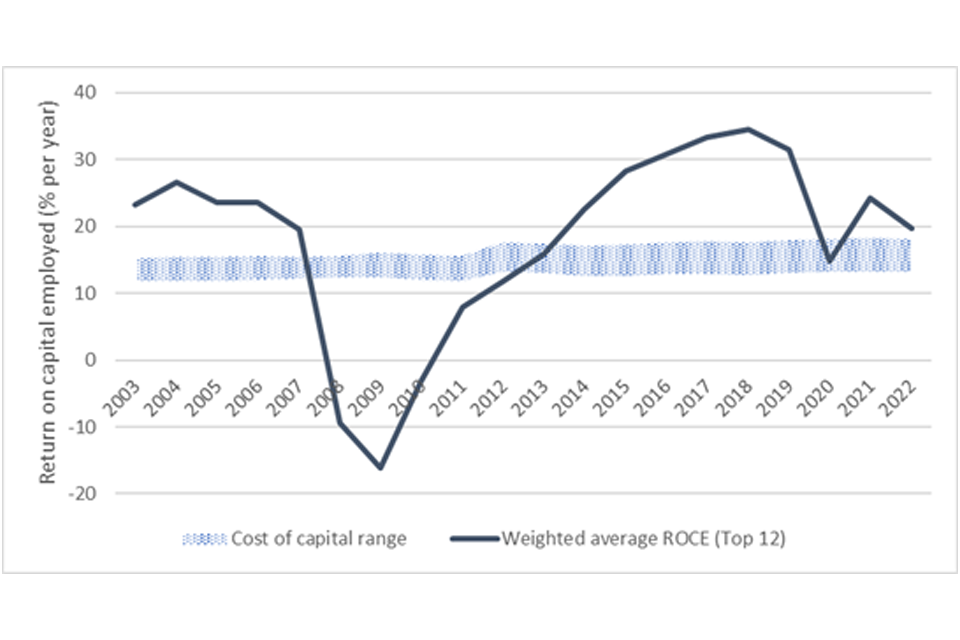

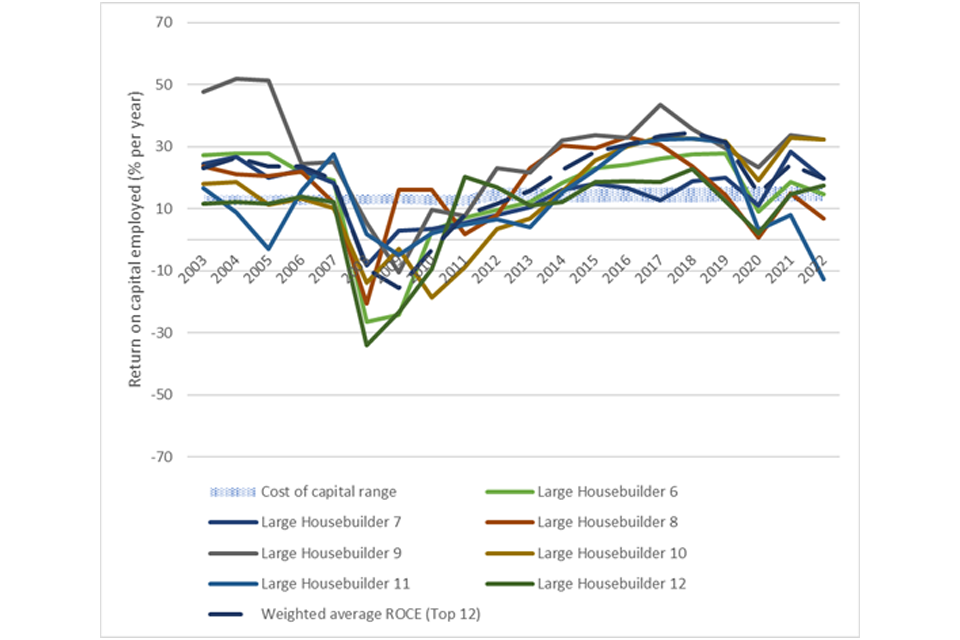

Figure 3.3 below illustrates the profitability of the 12 largest housebuilders over the 20-year period, as compared with our estimate of their cost of capital for the corresponding period.

Figure 3.3: Weighted average ROCE for the 12 largest housebuilders compared with our range for the cost of capital

Alt text

Figure 3.3 plots annual return on capital employed (ROCE) across the 12 largest housebuilders against our period of review from 2003 to 2022. It also plots our estimate of the range for the cost of capital across the same period.

Source: CMA analysis based on information drawn from large housebuilders annual reports and accounts.

We have found that the 12 largest housebuilders have generally earned returns in excess of the cost of capital over the 20-year period, although profitability has fluctuated across the period. Given the fluctuations in profitability across the period, we consider separately below their profitability leading up to the GFC, their profitability during and in the immediate aftermath of the GFC, and their profitability following the GFC and leading up to 2022.

Profitability leading up to the GFC (2003 to 2007)

During this period, on average, the 12 largest housebuilders earned returns in excess of the cost of capital, which reflects a generally favourable operating climate for them over the period. The demand for new homes was supported by low interest rates, good employment levels, and the continuing serious constraint on supply caused by delays within the planning system.

Profitability during and in the immediate aftermath of the GFC (2008 to 2012)

During this period, the 12 largest housebuilders earned returns in line with or below their cost of capital, including a period of losses in the immediate aftermath of the GFC from 2008 to 2010.

The GFC adversely impacted all housebuilders, as prospective purchasers of new homes found it difficult to obtain mortgages. This caused housebuilders, in contrast to their normal build-out practices whereby they seek to sell homes at prices prevailing in local second-hand markets, to significantly reduce the prices of the homes they were already constructing in order to sell them to generate funds. The prevailing economic conditions therefore resulted in the 12 largest housebuilders realising lower profit margins on the sale of new homes, resulting in reduced levels of profitability. The large housebuilders (with the exception of Berkeley) were also forced to write down the value of their land banks, causing many of them to incur losses over the period. This was because, in many cases, the price that they had paid in the past for the land would have then not enabled them to develop that land profitably due to the fall in house prices.[footnote 44]

This all adversely impacted the profitability of individual large housebuilders to varying degrees, depending, in particular, on the volume of land they held at the time and the extent to which the GFC adversely affected the value of that land. See Figures 3.4 and 3.5 below.

The profitability of the 12 largest housebuilders gradually improved towards the end of the period, primarily driven by the fall in interest rates proving beneficial to those prospective purchasers who were able to obtain mortgages under the stricter lender conditions immediately following the GFC but also through government initiatives to relieve housebuilders of excess stock and increase mortgage take-up.

Profitability following the aftermath of the GFC and leading up to 2022 (2013 to 2022)

During this period, on average, the 12 largest housebuilders earned increasingly higher returns above the cost of capital up to 2018. After 2018 average returns plateaued and then fell to levels that nevertheless were above or at the cost of capital.

In the first half of this period, housebuilders benefitted from increasing consumer confidence, driven by improving access to mortgages, low interest rates, and the launch of the government’s Help to Buy scheme in 2013.[footnote 45]

The large housebuilders also benefited from the revision of the planning regime in 2012 which included a presumption in favour of sustainable development.[footnote 46],[footnote 47] This enabled the large housebuilders more readily to gain planning permission for developments where they had already purchased the land without planning permission, enabling them to construct homes and bring them to the market on these sites, thereby increasing their profitability.[footnote 48]

In 2020, housebuilders’ profitability was adversely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused them to curtail operations, resulting in lower sales and increased costs.[footnote 49] This was somewhat mitigated by the government temporarily reducing stamp duty rates, which drove up demand, resulting in an increase in house prices and profitability.

Profitability levels, particularly in 2021 and 2022, were also adversely impacted by the significant provisions that housebuilders have made to cover the costs of the remedial work on legacy buildings found to be necessary in the wake of the 2017 Grenfell fire.[footnote 50]

More recently, profitability levels have been adversely impacted by an increase in construction costs,[footnote 51] the need to meet more stringent planning requirements (for example, in respect of environmental standards), and an increase in inflation and interest rates dampening demand.

Variation in levels of profitability across the largest housebuilders

Although we have found that the 12 largest housebuilders have generally earned returns in excess of the cost of capital over the 20-year period, there was variation in their individual performance during this period.

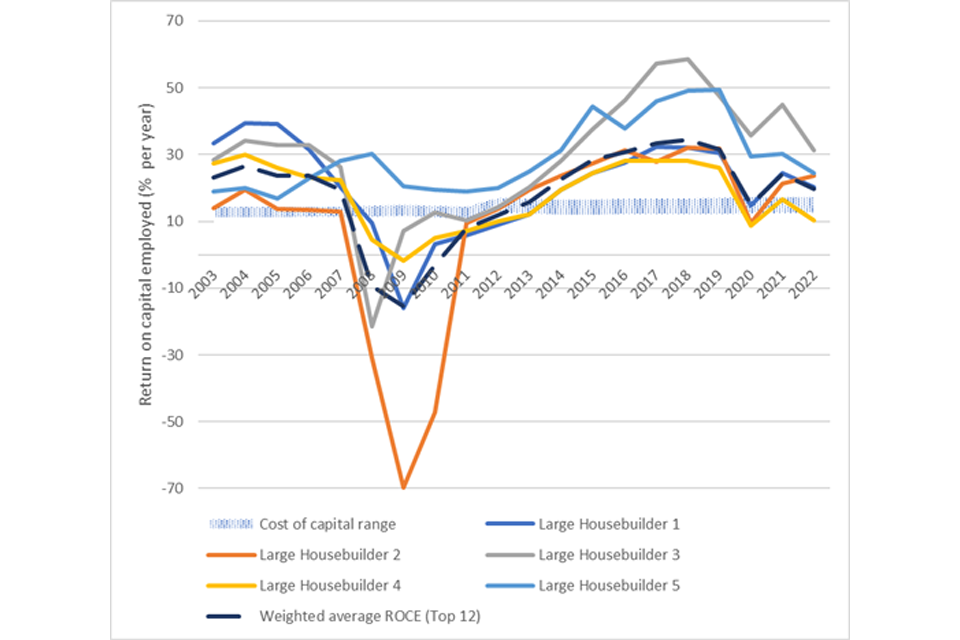

Figure 3.4 shows the profitability of the 5 largest housebuilders over the 20-year period, as compared with our estimate of the cost of capital for the corresponding period.

Figure 3.4: ROCE for the 5 largest housebuilders compared with our range for the cost of capital

Alt text:

Figure 3.4 plots:

a) return on capital employed (ROCE) for each of the 5 largest housebuilders in our dataset

b) weighted average return on capital employed across the 12 largest housebuilders

c) our estimate of the range for the cost of capital, against our period of review from 2003 to 2022, all expressed in percent for each year

Source: CMA analysis based on information drawn from large housebuilders annual reports and accounts.

Note 1: The 5 largest housebuilders have been determined on the basis of their revenues over the 20-year period inflated to December 2022 £s using CPIH

Note 2: The range for the cost of capital relates to all the large housebuilders in our sample, not just the 5 shown here

Figure 3.5 shows the profitability of the remaining 7 largest housebuilders over the 20-year period, as compared with our estimate of the cost of capital for the corresponding period

Figure 3.5: ROCE for the other 7 of the 12 largest housebuilders compared with our range for the cost of capital

Alt text

Figure 3.5 plots a) return on capital employed (ROCE) for each of the other 7 of the 12 largest housebuilders in our dataset b) weighted average return on capital employed across the 12 largest housebuilders and c) our estimate of the range for the cost of capital, against our period of review from 2003 to 2022, all expressed in percent for each year.

Source:

- CMA analysis based on information drawn from large housebuilders annual reports and accounts

Note 1: The other largest housebuilders have been determined on the basis of their revenues over the 20-year period inflated to December 2022 £s using CPIH.

Note 2: The range for the cost of capital relates to all the large housebuilders in our sample, not just the 7 shown here.

We have found that the 5 largest housebuilders have generally achieved higher levels of profitability than the others. For example, one large housebuilder, following the changes to the planning regime in 2012, was able to build out the strategic land bank it held at the time, thereby realising the greater returns associated with buying land without planning permission. This large housebuilder also benefitted significantly from the increase in demand driven by the Help to Buy scheme: in 2018, we estimate that this large housebuilder sold circa 60% of the homes it had delivered in that year to customers accessing the scheme.[footnote 52] Another large housebuilder benefitted from developing complex brownfield sites, typically to construct tall blocks of flats in areas of high demand at the higher end of the market.

In contrast, we have found that there is greater variability in the performance of the other large housebuilders. For example, 4 of the large housebuilders were forced to restructure their businesses, sometimes repeatedly, during the period of review, often in response to the operational and financial challenges caused by the GFC (see paragraph 3.33).

As previously explained in paragraph 3.34, there was also significant variability in the extent to which the GFC adversely impacted the profitability of individual large housebuilders.

Current position and outlook

In the current period, the housebuilders have reported that their profitability is falling due to subdued demand caused by the increase in interest rates resulting in a sharp rise in the cost of mortgages. In contrast to the GFC, however, house prices have so far held relatively steady, meaning the impact of current market conditions is manifesting itself, in the first instance, through reduced output rather than falling prices.[footnote 53]

Conclusions

We have found that the profitability of the 12 largest housebuilders has been generally high during those periods outside the GFC and its immediate aftermath. The period from 2013 to 2019 was particularly elevated due to supportive economic circumstances for housebuilders – in particular, low interest rates and quantitative easing – as well as measures taken by the government to help homebuyers fund deposits for the purchase of new homes through the Help to Buy scheme.[footnote 54]

While we have seen an extended period during the 2010s in which the profitability of the 12 largest housebuilders has been higher than we would expect in a well-functioning market, we do not take this to indicate that intervention is required to directly tackle this level of profitability, because:

-

the housing market is highly cyclical and impacted by external factors, such as the wider economic climate

-

profitability during the 2010s is likely to have been boosted by temporary factors that are no longer in evidence, in particular a prolonged period of ultra-low interest rates and the Help to Buy schemes’ support for first-time buyers

-

there was significant variation in the performance of individual large housebuilders in our sample

Given the points above, there is a risk that any measures seeking directly to reduce housebuilder profitability may create an additional downward pressure on the number of houses being built, exacerbating the supply problems that have characterised this market over a long period.

Instead, our analysis suggests that actions could be sought to improve the functioning of the market more generally, and the impact of competition within it, which would then serve to bear down on the price of new homes and the levels of profitability that large housebuilders are able to achieve.

Quality

The quality of goods and services is another indicator of how well a market is working. In a competitive market, when all other factors are equal, a product or service that offers higher consumer satisfaction would be expected to outsell a product with lower consumer satisfaction. However, this does not mean that there would not be differentiation between providers: a competitive market is likely to generate different price/quality combinations across providers in accordance with the preferences of different customers, who can observe, understand, and choose between the available combinations.

For the purposes of our market study, we have defined new build housing quality in terms of the reasonable expectations a consumer might have of their new build home. We consider that this includes the structural integrity of the property, and the ability to use it and its features as reasonably intended. We have not sought to interrogate whether requirements for building standards are adequate, as reforms are being implemented in response to building safety concerns by the UK, Scottish, and Welsh governments. Instead, we have focused on indicators of the quality of new homes overall, consumer satisfaction, the experience of buying a new home and ease of getting issues resolved.

As quality can encompass different parameters, there is no single measure for the quality of new build housing. However, there are several sources of evidence that can be used to infer quality of build or to explore and understand particular aspects of quality. In this study we have analysed data from the National New Homes Customer Satisfaction Survey (CSS) run by the Home Builders’ Federation (HBF) for the 4 survey years 2018 to 2019 to 2021 to 2022,[footnote 55],[footnote 56] and abridged, aggregated findings from quantitative research by the agency In-house Research on behalf of 80 housebuilders.[footnote 57]

We have also carried out our own qualitative consumer research consisting of 50 in-depth interviews with recent new build buyers about the quality of their new homes (CMA consumer research),[footnote 58] and we have reviewed complaints submitted to us by consumers in response to our Statement of Scope and Update Report.

The evidence suggests that the majority of customers are happy with the pre-sale process and the period shortly after completion. The 8-week CSS suggests that there is high overall satisfaction, with 89% of customers in 2021 to 2022 saying they would recommend their builder, and 83% saying that they were very or fairly satisfied with the pre-completion services.[footnote 59] Similarly, our consumer research found that most homeowners were satisfied with their purchase journey, although some felt that housebuilders’ sales teams had a tendency to misrepresent aspects of quality of the property and estate. The In-house Research survey found that in the period of purchasing the property and shortly after completion, customers were generally satisfied.[footnote 60]

However, our consumer research and our Q19 verbatim analysis both indicate that customers’ perceptions of the quality of service they had received (or in some cases were still receiving) deteriorated as they lived in their homes for longer.

Moreover, a specific issue on customisation came to light through our consumer research where a considerable number of buyers were left dissatisfied. Concerns centred around ‘hidden costs’, specifically, the lack of clarity around what features, fixtures and fittings were (not) included as standard, the perceived limited, overpriced, or low quality of customisation options, and the timing for payment of requested upgrades.

Across a range of evidence sources, we see a less positive picture once customers have lived in the home for a period of months, particularly in relation to their experience of snags. In the 9-month CSS, for example, 487 out of 1,200 respondents referred negatively to snagging issues in their Q19 verbatim answers. We see evidence of a statistically significant increase over time in the proportion of homeowners reporting higher numbers of snags, with 35% of respondents to the 9-month CSS in 2021 to 2022 reporting 16 or more different problems.[footnote 61]

While we have not been able to gather quantitative evidence on the severity of problems, our qualitative consumer research suggests that although many issues are relatively minor, there are certainly cases of more serious issues. Likewise, in our Q19 verbatim analysis we saw (for example) the following from respondents:

‘After moving in, my attic hatch fell completely out of the ceiling of its own, because the joiner had only used 3 screws to fix it instead of 16 plus.’

‘The stairs collapsed while walking up [them] with my son.’

‘From the day we moved in and I badly scolded my hands due to the faulty boiler, we knew things were not going to be straightforward.’

‘[Ongoing] leaks … which have led to serious damage to our home … we had to rip out our bathroom floor as mould was growing under the flooring.’

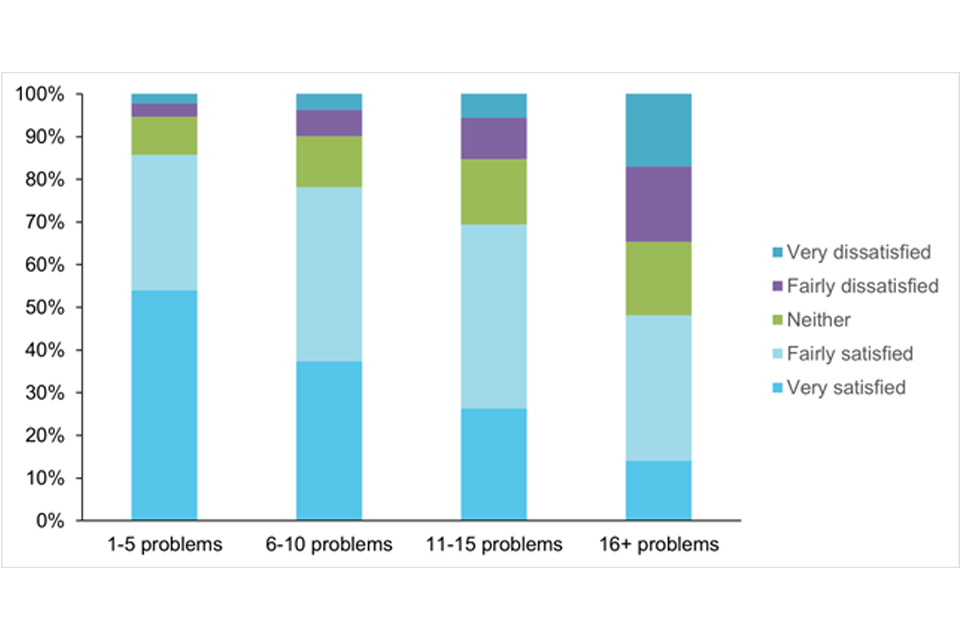

The 9-month CSS findings suggest that a significant proportion of customers who report issues to their builders do not have their problems resolved within a reasonable timescale and to their satisfaction, particularly those who experience the highest number of separate issues (see Figures 3.6 and 3.7).

Figure 3.6: Time taken to repair snags by the number of snags reported

Alt text

A bar chart showing how the time taken to repair snags varies with the number of snags reported at 9 months post-completion, based on the CMA’s analysis of the National New Homes Customer Satisfaction Survey (CSS) dataset for 2021 to 2022.

For customers reporting more than 16 problems, in 65% of cases these snags were still to be rectified.

For customers reporting between 11 and 15 problems in 44% of cases these snags were still to be rectified.

For customers reporting between 6 and 10 problems, in 31% of cases these snags were still to be rectified.

For customers reporting between 1 and 5 problems, in 18% of cases these snags were still to be rectified.

Source: CMA analysis of 2021 to 2022 9-month CSS Q8c: Has the repair work been …?

Base: All who reported problems with their home to their builder and answered Q8c (n=38,870); 1-5 problems: n=8,720, 6-10 problems: n=9,420, 11-15 problems: n=6,369, 16+ problems: n=14,361

Figure 3.7: Satisfaction with repair of snags by the number of snags reported

Alt text

A bar chart showing how customer satisfaction with repair of snags varies with the number of snags reported at 9 months post-completion, based on the CMA’s analysis of the National New Homes Customer Satisfaction Survey (CSS) dataset for 2021 to 2022.

For customers reporting more than 16 problems, around one in 3 were fairly or very dissatisfied.

For customers reporting between 11 and 15 problems, around one in 6 were fairly or very dissatisfied.

For customers reporting between 6 and 10 problems, around one in 10 were fairly or very dissatisfied.

For customers reporting between 1 and 5 problems, around one in 17 were fairly or very dissatisfied.

Source:

- CMA analysis of 2021 to 2022 9-month CSS Q8d: How satisfied or dissatisfied were you … with the standard of any repair work carried out by your builder?

Base: All who reported problems with their home to their builder and answered Q8d (n=31,503); 1-5 problems: n=8,191, 6-10 problems: n=8,497, 11-15 problems: n=5,410, 16+ problems: n=9,405

In addition to single indicators from the CSS and the In-house Research survey, we have developed a composite indicator using the CSS dataset to identify customers who express overall dissatisfaction with problems in their home, and with the way these problems are addressed.[footnote 62] Overall, 12% of customers met these criteria in 2021 to 3022, and this had hardly changed over the previous 4 years.

The experience of customers in this regard appears to vary substantially across housebuilders: among the top 11 in 2021 to 2022, the proportion of customers expressing dissatisfaction ranged from 1% to 24%. Outside of the top 11 housebuilders, other large companies appear to have a higher proportion of customers experiencing these types of problem (18% of their customers, compared with 11% overall for the top 11). The medium and small housebuilders sit between these on average, at 12% and 14% of customers respectively.

In summary, the data we have analysed shows that, overall, most consumers are happy with their new homes. As part of the purchase process, they expect snags (although not the volume of snags they actually encounter) and have sought for these to be fixed post-completion. However, where consumers experience a greater number of snags or faults, it can be more difficult to resolve them, taking weeks or even months. It also appears that there is a small but significant minority experiencing the most serious defects, who are likely to experience significant consumer detriment.

Innovation