Energy white paper: Powering our net zero future (accessible HTML version)

Updated 18 December 2020

Ministerial foreword

The government presents this white paper at a time of unprecedented peacetime challenge to our country. Coronavirus has taken a heavy toll on our society and on our economy. But we will overcome COVID-19 and rebuild our economy, building back better and levelling up the country.

As we do so, we must address the inter-generational challenge of climate change. Unchecked, the impact of rising global temperatures represents an existential threat to the planet. So, building back better means building back greener.

The UK has set a world–leading net zero target, the first major economy to do so, but simply setting the target is not enough – we need to achieve it. Failing to act will result in natural catastrophes and changing weather patterns, as well as significant economic damage, supply chain disruption and displacement of populations.

Tackling climate change will require decisive global action and significant investment and innovation by the public and private sectors, creating whole new industries, technologies, and professions.

But fighting climate change offers huge opportunity for both growth and job creation. The global markets for low-carbon technologies, electric vehicles and clean energy are fast growing: zero emission vehicles could support 40,000 jobs by 2030, with exports of new technologies such as CCUS having the potential to add £3.6 billion GVA by 2030. The time is now to seize these opportunities.

This white paper puts net zero and our effort to fight climate change at its core, following the Prime Minister’s Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution. The Ten Point Plan sets out how government investment will leverage billions of pounds more of private investment and support up to 250,000 jobs by 2030.

This includes building on our leadership in offshore wind to target 40GW by 2030 – enough to power every home in the UK – which alone will support up to 60,000 jobs.

The way we produce and use energy is therefore at the heart of this. Our success will rest on a decisive shift away from fossil fuels to using clean energy for heat and industrial processes, as much as for electricity generation.

These are more than academic considerations; the shift to net zero will affect us all. This white paper presents a vision of how we make the transition to clean energy by 2050 and what this will mean for us as consumers of energy in our homes and places of work, or for how businesses use energy to produce goods and services.

It sets out the changes which will be required. We will reduce emissions through shifting from gas to electricity to heat our homes and by better insulating the buildings in which we live and work. We will end the sale of petrol and diesel cars and vans, and accelerate the transition to clean, zero tailpipe emission vehicles. We will start to capture carbon emissions from power generation and from industry. And we will switch to new, clean fuels such as hydrogen for heat, power and industrial processes.

As we leave fossil fuels behind us and increasingly rely on clean electricity, our experiences as energy consumers will be very different. Smart technologies are revolutionising how we can engage the market. Smart meters and a range of smart appliances, backed by new smart tariffs, will give us control about how we use energy and help us manage our bills – running the washing machine or charging the electric vehicle when demand is low and electricity is cheap, even selling surplus power back to the grid at a profit.

And we will do this with affordability at the front of our minds. The costs of renewables have fallen sharply over the last 5 years. Offshore wind prices in renewable Contracts for Difference auctions have fallen from £120/MWh in 2015 to around £40/MWh in last year’s auction.

Greater competition and more innovation will drive down the costs of our energy system even further. We expect energy companies to ensure that the benefits of a more efficient system result in a fair deal for consumers. Where we use taxpayers’ money to fund the transition to clean energy, we will leverage private capital as much as we can.

Across the board, as a result of our polices, energy bills will remain affordable over the 2020s. A major push on improving the energy efficiency of our homes will mean households can significantly reduce demand and save money on their bills.

We understand the effect that COVID-19 has had on household incomes, and therefore commit to protecting those who are particularly vulnerable. Lower income households can receive up to £10,000 to improve the energy efficiency of their homes via the Green Homes Grant scheme, saving up to £600 each year on bills on average. Through this white paper, we are expanding the Warm Home Discount to around 3 million homes to provide £150 a year off electricity bills, representing £1.9 billion of extra support for households in fuel poverty. This builds on the Ten Point Plan’s commitment to extend the Energy Company Obligation to 2026.

This is an ambitious domestic agenda on which we will also seek to secure equally ambitious international action, through the UK’s presidency of COP26, the UN’s climate conference being held in Glasgow in November 2021. The actions we take as a result of this white paper, as part of our wider climate agenda, are intended to show leadership and vision and demonstrate to our partners around the world that now is the time to take the bold steps to tackle climate change. The UK is leading from the front in the transition to clean energy, while ensuring that we leave no one behind as we build back greener.

Rt Hon Alok Sharma MP

Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy

Introduction

We are on the cusp of a global Green Industrial Revolution.

The Prime Minister’s Ten Point Plan has set out the measures that will help ensure the UK is at the forefront of this revolution, just as we led the first over 2 centuries ago.

As nations move out of the shadow of coronavirus and confront the challenge of climate change with renewed vigour, markets for new green products and services will spring up round the world. Taking action now will help ensure not just that we end our contribution to climate change by achieving our target of net zero emissions. It will help position UK companies and our world class research base to seize the business opportunities which flow from it, creating jobs and wealth for our country.

Following on from the Ten Point Plan and the National Infrastructure Strategy, the Energy White Paper provides further clarity on the Prime Minister’s measures and puts in place a strategy for the wider energy system that:

- transforms energy, building a cleaner, greener future for our country, our people and our planet

- supports a green recovery, growing our economy, supporting thousands of green jobs across the country in new green industries and leveraging new green export opportunities

- creates a fair deal for consumers, protecting the fuel poor, providing opportunities to save money on bills, giving us warmer, more comfortable homes and balancing investment against bill impacts

The compelling case for tackling climate change

We are reminded on a daily basis why we need this Green Industrial Revolution: climate change is having a real effect on our planet.

The melting of glaciers and ice sheets is accelerating, contributing to rising sea levels across the globe, with melting rates of ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica matching the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s worst-case climate warming scenarios.[footnote 1] All 10 of the warmest years in the UK’s temperature record have taken place since 2002.[footnote 2] Rainfall over Scotland is up 10% from the start of the 20th century.[footnote 3] The record-breaking European summer heatwave of 2003 resulted in at least 70,000 deaths across the continent,[footnote 4] and such heatwaves are projected to become the norm in the UK by the 2040s at current rates of warming.[footnote 5]

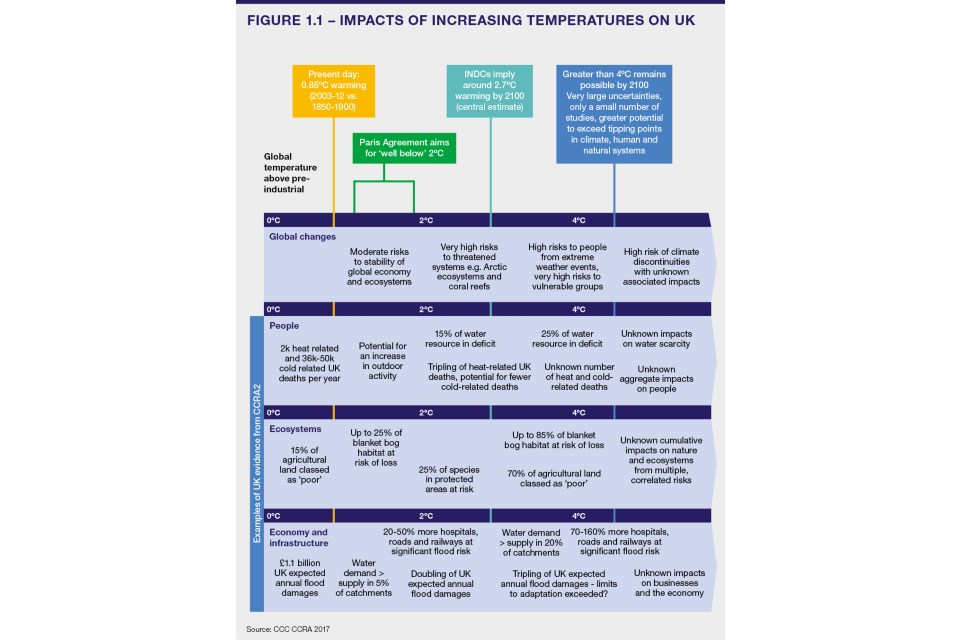

We need to act urgently. The future impacts of climate change depend upon how much we can hold down the rising global temperature. To minimise the risk of dangerous climate change, the landmark Paris Agreement of 2015 aims to halt global warming at well below 2°C, while pursuing efforts to limit it to 1.5°C, increasing measures to adapt to climate change, and aligning financial systems to these goals.[footnote 6]

At the global scale, however, we are not presently on track to reach the temperature goal of the Paris Agreement. Based on current national pledges, and assuming the level of ambition does not change, the world is heading for around 3°C of warming by the end of the century.[footnote 7]

The cost of inaction is too high.[footnote 8] We can expect to see severe impacts under 3°C of warming. Globally, the chances of there being a major heatwave in any given year would increase to about 79%, compared to a 5% chance now.[footnote 9] Many regions of the world would see what is now considered a 1-in-100-year drought happening every 2 to 5 years.[footnote 10]

At 3°C of global warming, the UK is expected to be significantly affected, seeing sea level rise of up to 0.83 m.[footnote 11] River flooding would cause twice as much economic damage and affect twice as many people, compared to today,[footnote 12] while by 2050, up to 7,000 people could die every year due to heat, compared to approximately 2,000 today.[footnote 13] And, without action now, we cannot rule out 4°C of warming by the end of the century, with real risks of higher warming than that.[footnote 14] A warming of 4°C would increase the risk of passing thresholds that would result in large scale and irreversible changes to the global climate, including large-scale methane release from thawing permafrost and the collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation.[footnote 15] The loss of ice sheets could result in multi-metre rises in sea level on time scales of a century to millennia.[footnote 16]

To meet the temperature goal of the Paris Agreement, the world must collectively and rapidly reduce global emissions to net zero over the next 30 years. Success will mean we are less exposed to flood and heat risks and preserve our national security, our prosperity, and our natural world which are threatened by the global disruption of climate change.

Figure 1: impacts of increasing temperatures on UK

Our domestic agenda

30 years of successfully reducing UK emissions while simultaneously growing our economy

500% increase in the amount of renewable capacity connected to the grid from 2009 to 2020

72% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from electricity generation between 1990-2019

As we tackle climate change, we will have the interests of consumers at the front of our mind, now and for future generations.

We are committed to ensuring that the cost of the transition to net zero is fair and affordable. We have consistently balanced spending on measures that decarbonise the energy system with the need to help consumers save money on their bills. Thanks to early investment, many low-carbon technologies are now cheaper than their fossil fuel counterparts.

Our vision is of a system with consumers at its heart, able to make money or save on bills through using the new technologies net zero will require. So our approach means not just deploying measures that save energy and reduce bills, but also ensuring the energy system is fit for a net zero world, making markets efficient, incentivising people to move to clean energy solutions, or making sure system rules are agile and flexible to accommodate new technologies and new ways of doing things.

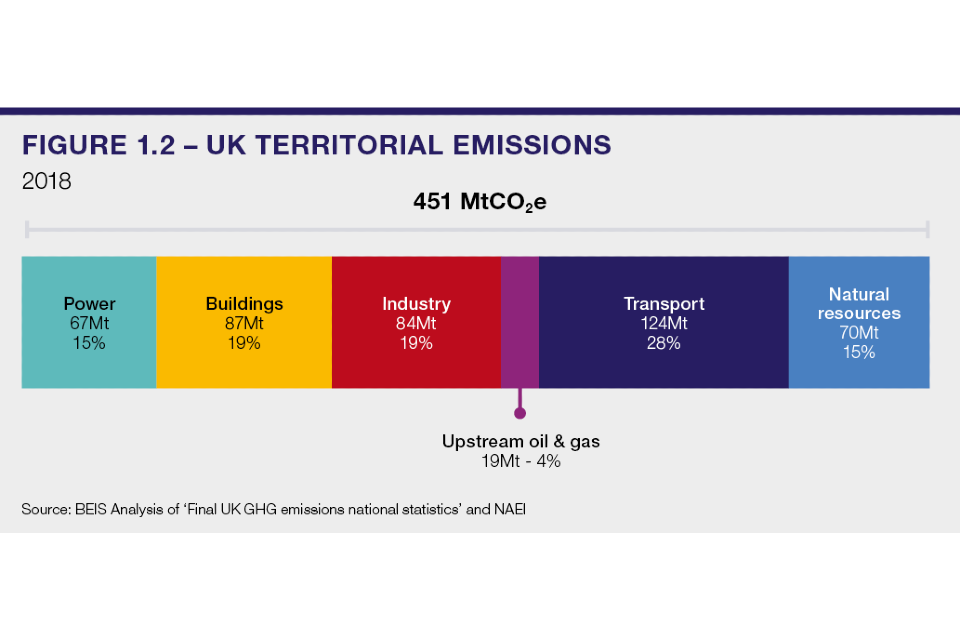

But affordability does not mean compromising our ambition. Achieving our 2050 goal requires action across the economy. The measures in this white paper will reduce emissions from power, buildings, industry, upstream oil and gas, and address the implications for the energy system of electrifying surface transport. We will publish our wider Transport Decarbonisation Plan in the spring.

Action on energy will be consistent with our wider environmental commitments, as we balance new technologies and the need for new infrastructure with protecting the environment, including air quality. Our 25 Year Environment Plan aims to improve the environment within a generation. Through the Environment Bill, we are placing this ambitious set of proposals on a legal footing, including a commitment to bring forward new legally binding environmental targets (on air quality, biodiversity, water, and resource efficiency and waste reduction) by October 2022.

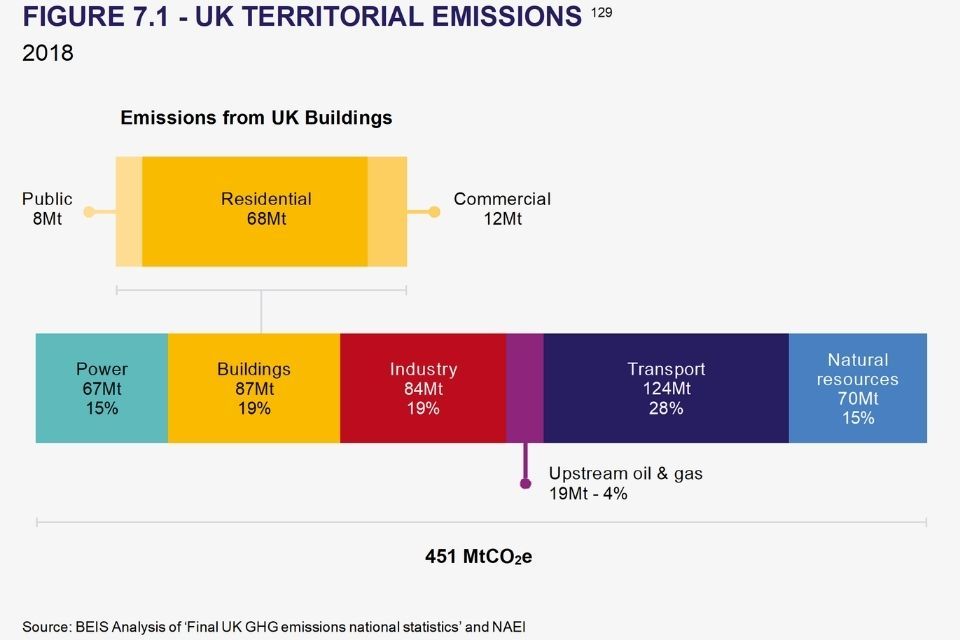

Figure 1.2: UK territorial emissions

Figure 1.3: UK versus rest of G7 GDP and emissions

Our National Adaptation Programme, which was updated in 2018, sets out the actions which the government is, and will be taking, to address the risks and opportunities posed by climate change in response to the Climate Change Risk Assessment. This includes a dedicated chapter on infrastructure, including actions to build the energy sector’s resilience to climate change.

No one doubts the challenge of achieving net zero emissions, but the UK is able to build on 30 years of successfully reducing emissions while simultaneously growing our economy. Between 1990 and 2018, emissions fell by 43% while GDP rose by 75%, with the UK decarbonising faster than any other G20 country since 2000 (Figure 1.3).[footnote 18]

Energy has led the way. In 2019, greenhouse gas emissions (MtCO2e) from electricity generation were down 13% on 2018 levels and 72% lower than 1990 levels,[footnote 19] as we have switched from coal to gas and renewable power together with the continued contribution of nuclear. In April 2017, the UK experienced its first coal free day since the industrial revolution. From April to June 2020, the total coal-free period lasted 67 days.[footnote 20]

Over the past decade, and with government support, the amount of renewable capacity connected to the grid has increased from 8GW in 2009 to 48GW at the end of June this year, an increase of 500%.[footnote 21] The share of low-carbon electricity generation has risen to 54% in 2019, with renewables at a record 37%.[footnote 22]

Through a mix of early policy action, increased competition, innovation, and growth in deployment, our sustained support for clean electricity has helped secure dramatic falls in the costs of some renewables and provided developers and private investors with long term certainty.

The cost of offshore wind projects contracted in 2019 fell by 30% for example, relative to those contracted in 2018.[footnote 23] There are even early signs of some renewable technologies deploying without direct policy support.[footnote 24]

But there is still much more to do. Our energy system is dominated by the use of fossil fuels and will need to change dramatically by 2050 if we are to achieve net zero emissions (see figure 1.4).

Decarbonising the energy system over the next thirty years means replacing - as far as it is possible to do so - fossil fuels with clean energy technologies such as renewables, nuclear and hydrogen.

Figure 1.4: Illustrative UK final energy use in 2050

This is a significant and historic undertaking. It means ending our dependency on oil to power nearly half of our economy. It means largely eliminating the use of natural gas to heat our homes, and make them considerably more efficient – but as 20% of homes currently overheat even in cool summers we will need to ensure that our homes are not just efficient, but adapted to the future climate.[footnote 25] This will apply throughout the system.

Clean electricity will become the predominant form of energy, entailing a potential doubling of electricity demand and consequently a fourfold increase in low-carbon electricity generation. We must secure this transition while retaining the essential reliability, resilience and affordability of our energy, as the bedrock of a modern, productive economy driving almost every facet of our home and working lives.

Delivering this transition will require billions of pounds of investment in clean energy infrastructure or new low-carbon technologies, and a major shift away from spending in fossil fuels. As set out in the National Infrastructure Strategy,[footnote 26] delivering this volume of private investment will require multiple policy levers and the right market frameworks to encourage competition and drive down costs. This challenge is set against the backdrop of an economy which has been hit by the largest recession in 300 years as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our commitments to new and improved buildings, infrastructure and energy sources will support near-term investment and jobs in the UK. It will also establish world-leading capabilities in the new technologies which will be needed globally to tackle climate change, growing our capability to trade UK expertise around the world.

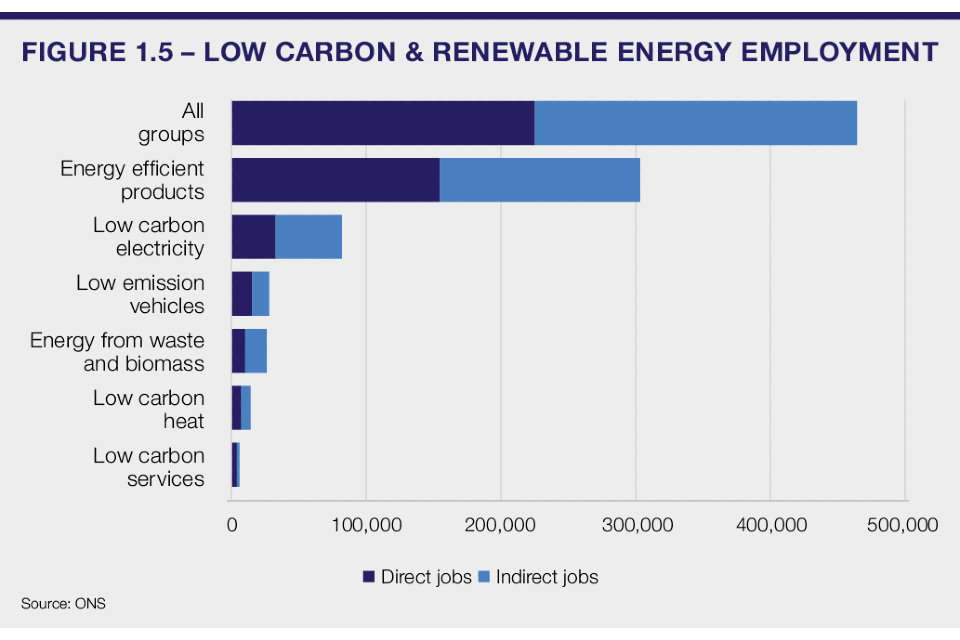

Figure 1.5: Low carbon and renewable energy employment

Across the UK almost half a million people are already employed in the low-carbon economy and its supply chains (Figure 1.5).[footnote 27] These jobs are frequently outside the South East of England, including electric vehicle manufacturing in the Midlands and North East, and reconditioning and recycling in the North East and West Midlands. The offshore wind sector supports an estimated 7,200 direct jobs as a whole, with a burgeoning industry on the north east coast of England, centred around the Humber and the Tees.

But this is just the beginning. In November 2020, the Prime Minister announced his Ten Point Plan to lay the foundations for a Green Industrial Revolution. We will start by supporting 90,000 jobs across the UK in this Parliament, and up to 250,000 by 2030. The response to the pandemic has been a reminder of the excellence of British science, a research and development (R&D) capability which engineers, fitters, construction workers and many others will harness to develop the clean energy technologies of the future and forge new industries to service new markets at home and abroad.

We will generate new clean power with offshore wind farms, nuclear plants and by investing in new hydrogen technologies. We will use this energy to carry on living our lives, running our cars, buses, trucks and trains, ships and planes, and heating our homes while keeping bills low. And to the extent that we still emit carbon, we will pioneer a new British industry dedicated to its capture and return to under the North Sea. Together these measures will reinvigorate our industrial heartlands, creating jobs and growth, and pioneering world-leading SuperPlaces that unite clean industry with transport and power.Energy White Paper.

The Prime Minister’s Ten point plan

Green public transport, cycling and walking

We will accelerate the transition to more active and sustainable transport by investing in rail and bus services, and in measures to help pedestrians and cyclists. We will fund thousands of zero-emission buses and give our towns and cities cycle lanes worthy of Holland.

Hydrogen

Working with industry the UK is aiming for 5GW of low-carbon hydrogen production capacity by 2030. We are also pioneering hydrogen heating trials, starting with a Hydrogen Neighbourhood and scaling up to a potential Hydrogen Town before the end of this decade.

Nuclear power

Nuclear power provides a reliable source of low-carbon electricity. We are pursuing large-scale nuclear, whilst also looking to the future of nuclear power in the UK through further investment in Small Modular Reactors and Advanced Modular Reactors.

Offshore wind

By 2030 we plan to quadruple our offshore wind capacity so as to generate more power than all our homes use today, backing new innovations to make the most of this proven technology and investing to bring new jobs and growth to our ports and coastal regions.

Jet zero and green ships

By taking immediate steps to drive the uptake of sustainable aviation fuels, investments in R&D to develop zero-emission aircraft and developing the infrastructure of the future at our airports and seaports, we will make the UK the home of green ships and planes.

Greener buildings

Making our buildings more energy efficient and moving away from fossil fuel boilers will help make people’s homes warm and comfortable, whilst keeping bills low. We will go with the grain of behaviour, and set a clear path that sees the gradual move away from fossil fuel boilers over the next fifteen years as individuals replace their appliances and are offered a lower carbon, more efficient alternative, supporting 50,000 jobs.

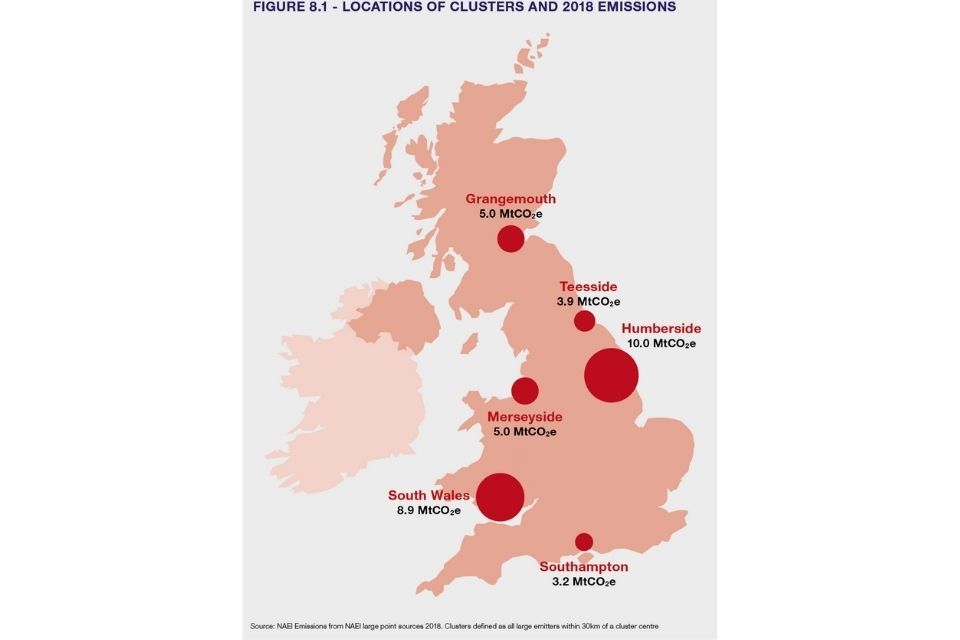

Carbon capture, usage and storage (CCUS)

Our ambition is to capture 10Mt of carbon dioxide a year by 2030 - the equivalent of 4 million cars’ worth of annual emissions. We will invest up to £1 billion to support the establishment of CCUS in 4 industrial clusters, creating ‘SuperPlaces’ in areas such as the North East, the Humber, North West, Scotland and Wales. We will bring forward details in 2021 of a revenue mechanism to bring through private sector investment into industrial carbon capture and hydrogen projects via our new business models to support these projects.

Protecting our natural environment

We will safeguard our cherished landscapes, restore habitats for wildlife in order to combat biodiversity loss and adapt to climate change, all whilst creating green jobs.

Zero emission vehicles

From 2030 we will end the sale of new petrol and diesel cars and vans, 10 years earlier than planned, and provide a £2.8 billion package of measures to support industry and consumers to make the switch to cleaner vehicles.

Green finance and innovation

We have committed to raising total R&D investment to 2.4% of GDP by 2027 and in July 2020 published the UK Research and Development Roadmap. The next phase of green innovation will help bring down the cost of the net zero transition, nurture the development of better products and new business models, and influence consumer behaviour.

Leading global action

The UK accounts for less than 1% of annual global emissions.[footnote 28] We therefore need to help other nations reduce their emissions in line with the Paris Agreement.

Our leadership is based on taking practical domestic action, which in turn creates business opportunities for the UK to export clean technology, skills and know-how.

We use our international partnerships and work through multilateral fora to influence international agreements on climate change and clean energy issues which help reinforce our domestic and international priorities. The principal vehicle we work through is the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which delivered the Paris Agreement.

We will continue to demonstrate international leadership by building on the policies set out in the UK’s National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP) and a number of other publications. This white paper goes even further than the ambitions set out in the NECP for renewables and energy efficiency.

Our presidency of the UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26), which will meet in Glasgow in November 2021, provides the opportunity to drive further ambitious action on climate change and unite the world on a path to a net zero economy, including through our COP26 Energy Transition Campaign and co-leadership of the Powering Past Coal Alliance.

We are already seeing encouraging signs. In March, the European Union (EU) Commission proposed the first European Climate Law, which would commit the EU to achieving net zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2050. In September, China announced that it would achieve carbon neutrality by 2060 and enhance its 2030 Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC). In October, both Japan and South Korea committed to achieving net zero by 2050. And thanks to the efforts of the UK, the EU, and other nations, there are now around 120 countries that are committed to, are developing plans or advancing consultations on long-term climate or carbon neutral targets.[footnote 29]

The countries delivering on these commitments will need to radically change their energy, transport, buildings and land use sectors. By driving forward UK action now, we can build companies that can win the lion’s share of these new global markets in the future.

What the white paper delivers - and beyond

This white paper builds on the Prime Minister’s Ten Point Plan to set the energy-related measures the Plan announced in a long-term strategic vision for our energy system, consistent with net zero emissions by 2050. It establishes our goal of a decisive shift from fossil fuels to clean energy, in power, buildings and industry, while creating jobs and growing the economy and keeping energy bills affordable. It addresses how and why our energy system needs to evolve to deliver this goal. And it provides a foundation for the detailed actions we will take in this Parliament to realise our vision.

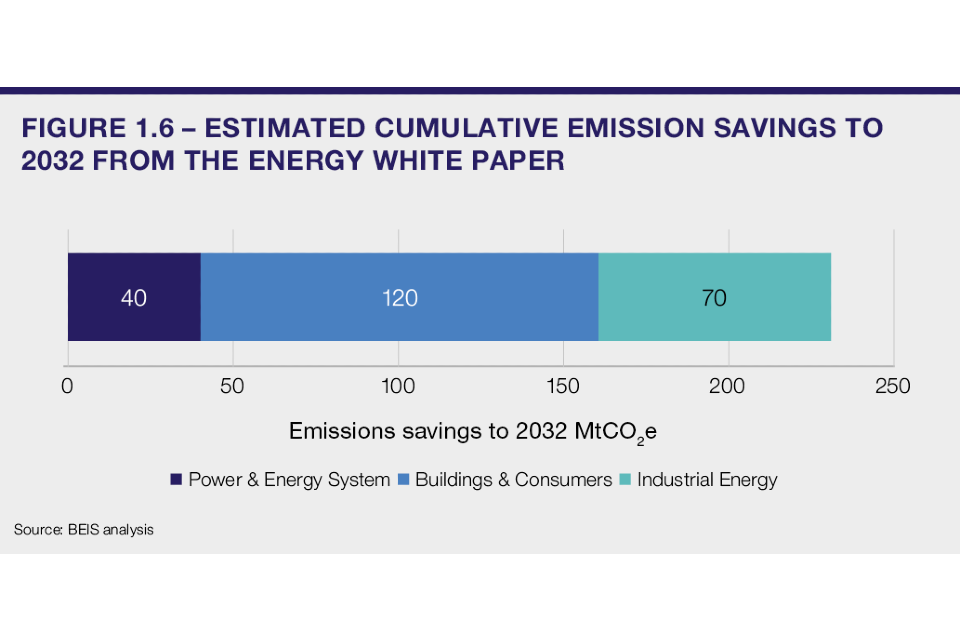

We estimate the measures in this paper could reduce emissions across power, industry and buildings by up to 230MtCO2e in the period to 2032 and enable further savings in other sectors such as transport. In doing so, they will support up to 220,000 jobs per year by 2030. These figures include the energy measures from the Prime Minister’s Ten Point Plan as well as additional measures provided in this white paper.[footnote 30]

We recognise that more will need to be done to meet key milestones on the journey to net zero, including our ambition for Carbon Budget 6, which we will set next year, taking into account the latest advice from the Climate Change Committee. In the run-up to COP26 we will bring forward a series of sectoral strategies, and our overarching Net Zero Strategy, which will set out more detail on how we will meet our net zero target and ambitious carbon budgets.

Figure 1.6: Estimated cumulative emission savings to 2032 from the Energy white paper

Overview of key commitments

This white paper sets out the government’s policies and commitments that will put us on course to net zero, levelling up the country and strengthening the union as we achieve this goal. We will:

Transform energy

Building a cleaner, greener future for our country, our people and our planet, by measures including:

- targeting 40GW of offshore wind by 2030, including 1GW floating wind, alongside the expansion of other low-cost renewables technologies

- supporting the deployment of CCUS in 4 industrial clusters including at least one power CCUS project, to be operational by 2030 and putting in place the commercial frameworks required to help stimulate the market to deliver a future pipeline of CCUS projects

- establishing a new UK Emissions Trading System, aligned to our net zero target, giving industry the certainty they need to invest in low-carbon technologies

- aiming to bring at least one large-scale nuclear project to the point of Final Investment Decision by the end of this Parliament, subject to clear value for money and all relevant approvals

- consulting on whether it is appropriate to end gas grid connections to new homes being built from 2025, in favour of clean energy alternatives

- growing the installation of electric heat pumps, from 30,000 per year to 600,000 per year by 2028

- building world-leading digital infrastructure for our energy system based on the vision set out by the independent Energy Data Taskforce, publishing the UK’s first Energy Data Strategy in spring 2021, in partnership with Ofgem

Support a green recovery from COVID-19

Growing our economy, supporting thousands of green jobs across the country in new green industries and creating new export opportunities, by measures including:

- increasing the ambition in our Industrial Clusters Mission 4-fold, aiming to deliver 4 low-carbon clusters by 2030 and at least one fully net zero cluster by 2040

- investing £1 billion up to 2025 to facilitate the deployment of CCUS in 2 industrial clusters by the mid-2020s, and a further 2 clusters by 2030, supporting our ambition to capture 10MtCO2 per year by the end of the decade

- working with industry, aiming to develop 5GW of low-carbon hydrogen production capacity by 2030

Creating a fair deal for consumers

Protecting the fuel poor, providing opportunities to save money on bills, giving us warmer, more comfortable homes and balancing investment against bill impacts, by measures including:

- creating the framework to introduce opt-in switching, consulting by March 2021 on how it should be designed, tested and incrementally scaled up

- considering how the current auto-renewal and roll-over tariff arrangements could be reformed to facilitate greater competition, consulting by March 2021 on how opt-out switching could be tested as part of any future reforms

- assessing what market framework changes may be required to facilitate the development and uptake of innovative tariffs and products that work for consumers and contribute to net zero, engaging with industry and consumer groups throughout 2021 before a formal consultation

- ensuring the retail market regulatory framework adequately covers the wider market, consulting by spring 2021 on regulating third parties such as energy brokers and price comparison websites

- establishing the Future Homes Standard which will ensure that all new-build homes are zero carbon ready

- consulting on regulatory measures to improve the energy performance of homes, and are consulting how on how mortgage lenders could support homeowners in making these improvements

- requiring that all rented non-domestic buildings will be Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) Band B by 2030, barring lawful exceptions

- extending the Energy Company Obligation to 2026 and expanding the Warm Home Discount to £475 million per year from 2022 to 2025/2026

In addressing these issues we respect the devolution settlements with Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. All proposals in this white paper which touch on devolved matters will be progressed in accordance with those settlements.

Chapter 1: Consumers

Our goal

We are committed to making the right reforms that will protect the interests of consumers and create opportunities to reduce bills and carbon emissions.

In partnership with the Office of Gas and Electricity Markets (Ofgem), we will:

- create a fair deal for consumers

- protect the fuel poor

- provide opportunities to make savings on energy bills

The strategic context

Energy is integral to everything we do, from work, to travel, to leisure, to just relaxing at home. Whether it be for heating and lighting our homes or powering appliances, we all rely on secure, affordable energy every day. But the way we use energy in the home is changing.

Smart technologies, enabled by our increasingly digital world, offer new products and services which help us to take control of our energy use and reduce bills. And, over the next 30 years, electricity will become a significant proportion of the energy we use at home, powering electric cars, replacing petrol and diesel, and enabling the installation of electric heat pumps which reduce the need for oil and gas to heat our homes.

This transformation of energy in our homes will only accelerate over the coming decade. The government and Ofgem have an important role to play, making regulatory reforms which place fairness and affordability at the heart of our efforts to protect the interests of consumers and create opportunities to save money.

This means:

- creating a fair deal for consumers. We will increase competition throughout the energy retail market to benefit consumers and, as we transition to net zero, we will make sure the costs of doing so are distributed fairly

- protecting the fuel poor. We will offer additional protections to the vulnerable and fuel poor, through our Energy Company Obligation (ECO) and expanded Warm Home Discount (WHD) schemes and the Green Homes Grant, providing financial support of at least £6.7 billion over the next 6 years (see ‘Buildings’ chapter)

- providing opportunities to make savings on energy bills. We will create opportunities for consumers to reduce bills and carbon emissions by upgrading the energy performance of homes (see ‘Buildings’ chapter), switching to clean energy, or using energy when it is cheapest thanks to smart technology

Smarter, cleaner energy for all consumers

Traditionally, households have been passive consumers of energy from fossil fuels.

Smart technology is unlocking new opportunities to give consumers more control, choice and flexibility over their energy use. We are seeing retail offers that will help consumers engage in the market and save money in the process.

Smart meters

Smart meters are replacing traditional gas and electricity meters in homes and small businesses across Great Britain as part of an essential infrastructure upgrade to make the energy system more efficient and flexible, helping to deliver net zero emissions cost-effectively.

Smart meters are also modernising energy services by ending manual meter readings, delivering accurate bills and enabling prepayment customers to conveniently track their usage and top-up credit without leaving home. The In-Home Display (IHD), which households are offered when they have smart meters installed, gives accurate information about energy consumption and costs so consumers can easily understand how to save money on their bills.

The real-time information about energy use, recorded by smart meters, ensures that consumers are accurately charged by their suppliers. Smart meters also enable consumers to access innovative solutions such as smart tariffs, including ‘time of use’ tariffs. These tariffs reward consumers financially for using less electricity at peak times of demand or using more when overall demand is low and there is surplus generation available, for example on a sunny or windy weekend. This can reduce the cost of using clean electricity to power homes, businesses and electric vehicles, making the system more efficient and saving consumers money.

Smart tariffs

Smart tariffs include: tariffs where costs vary by the time of use, based on the cost of electricity; export tariffs, for those with generation technology such as solar panels; load control tariffs that can manage when appliances are used to ensure consumers use the cheapest energy; and tariffs designed for consumers with low-carbon technology, for example, electric vehicles, to ensure they can charge at the cheapest times.

There are now new ways for households to find the best energy products and services to match their specific needs. This ensures consumers are getting the best deal available and can help them choose new ways to engage with the energy system.

Consumers can be rewarded for playing a bigger role in our energy system. There are plenty of ways to save money, from installing energy saving measures to making the most of new technologies, such as batteries, heating controls or smart washing machines and dishwashers. Consumers can also generate their own electricity through roof-top solar panels, store it in batteries, and even sell any excess power back to the grid to generate a profit at times of higher demand.

Case study: smart tariff comparison tool - Smarter Tariff – Smarter Comparison, Vital Energi

Vital Energi is leading a consortium of experts to develop a comparison tool that gives consumers an easy way to find the most suitable smart tariff. Smart tariffs are often not included on price comparison websites and consumers have little visibility of their benefits. For example, many electric vehicle owners are unaware that there are dozens of tariffs designed specifically for them.

Supported with government funding, the project is developing a tool which will help people find the best smart tariff to match their needs. Consumers can use their actual smart meter data as an input to get personalised, accurate comparisons and, after they switch, see if they have achieved the expected savings. It eliminates the need to manually provide estimated electricity bills and integrates time-of-use tariffs and use of low-carbon technologies in the tariff search. Consumer research indicates that many people would be more likely to use a smart comparison tool such as this.

At the end of the project in March 2021, the proof of concept will be free for anyone to reuse. This means that suppliers, comparison websites and others will be able to integrate it into their services or reuse it. The research findings will be made public so they can be used by innovators in the market.

Case study: Smart tariff - Agile Octopus Tariff, Octopus Energy

Agile Octopus is a ‘time-of-use’ tariff, which gives consumers access to half-hourly electricity prices, tied to wholesale prices, which are updated daily. So when energy prices drop, so could bills. Sometimes prices even go ‘negative’ - meaning that consumers can be paid to use energy during that period. Octopus also cap prices at 35p/kWh to protect consumers during price spikes.

Octopus calculate that, on this tariff, customers could save £120 a year by shifting electricity use outside of the 4pm to 7pm peak. This is best suited for households with lots of electricity demand during those periods. For example, households with electric heating or electric vehicles.

Case study: connected home - Core4Grid, geo

Through the ‘Core4Grid’ trial, battery storage and smart meters have been installed in 24 houses that already had solar panels, electric heating or electric vehicle chargers. Using Core - its ‘energy brain’ - the technologies have been integrated to run as a whole system within each home.

Core responds to signals from the electricity system to make decisions on when to use energy or charge the batteries, using either excess solar generated by the household’s panels or grid electricity imported during cheaper periods.

The trial has been running since March, with participating homes sourcing over half of the energy they used from their solar and batteries. The houses have generated almost 30MWh of local generation (equivalent to ten times a typical dual fuel household’s annual electricity use) for the period.

[footnote 31] Agile Octopus Tariff

[footnote 32] Core4Grid

Electric vehicles will accelerate this trend (see Transport). By using a smart charger when powering up their electric vehicle, consumers will play an essential role in helping manage electricity demand, avoiding the expensive peak periods. Increasingly, consumers will also be able to export energy from their electric vehicle back to the grid. In doing so, they could significantly reduce their energy costs and help maximise the amount of solar and wind energy used to charge their vehicle.

Case study: smart electric car charging and ‘vehicle-to-grid’ trial - Project Sciurus, Kaluza, Ovo Energy

Project Sciurus is the largest domestic ‘vehicle-to-grid’ (V2G) demonstration in the world - with 323 V2G chargers supplying electricity to the grid at times of high energy demand. These operate on the ‘Kaluza’ platform, which receives live signals from the grid so that consumers can charge their vehicle when prices are low, and sell electricity back to the grid at times of peak demand.

The Sciurus project is part of a £30 million Innovate UK competition, with a diverse consortium of participants taking part. The majority of trial participants have found V2G capability to be valuable. Consumers have changed how and when they were charging their electric vehicles to help reduce costs for themselves and the grid, all while helping balance the energy system and saving money.

And some local communities are coming together to establish their own approach to managing energy demand in their areas. Smart local energy systems are community-based initiatives which bring together a range of energy issues, typically including heat, power and transport, to reduce emissions in an integrated way, while also promoting local jobs and businesses. Local Authorities are key to delivering these systems by combining energy into their wider statutory work on housing, transport, waste and planning, making delivery more cost-effective and preparing for a net zero future. Government provides funding for Local Authorities to deliver programmes that support decarbonisation and will continue to work with communities to enable projects to be tailored and delivered to meet local needs.

Case study: community energy - Energy Local Clubs, Energy Local

Energy Local has designed a local energy market. Households and small renewable generators form a Local Energy Club, the first of which started in a small town called Bethesda, in North Wales back in 2016. Through this, households use their smart meters to show how much power they are using.

They agree a ‘match’ tariff with local generators that pays them a price for the power they produce when households are using it. This keeps more money local and offers consumers the chance to reduce household bills by using energy when it’s cheaper. They also partner with a supplier (Octopus Energy) to buy more power when there’s not enough locally.

It benefits suppliers, generators and communities, giving a fair price to renewable generators and developing a suitable package of improved energy controls in the home, particularly for those at risk of fuel poverty as the benefits of local generation can be shared with anyone who joins the Local Energy Club, without having to pay a high capital cost.

Household energy bills

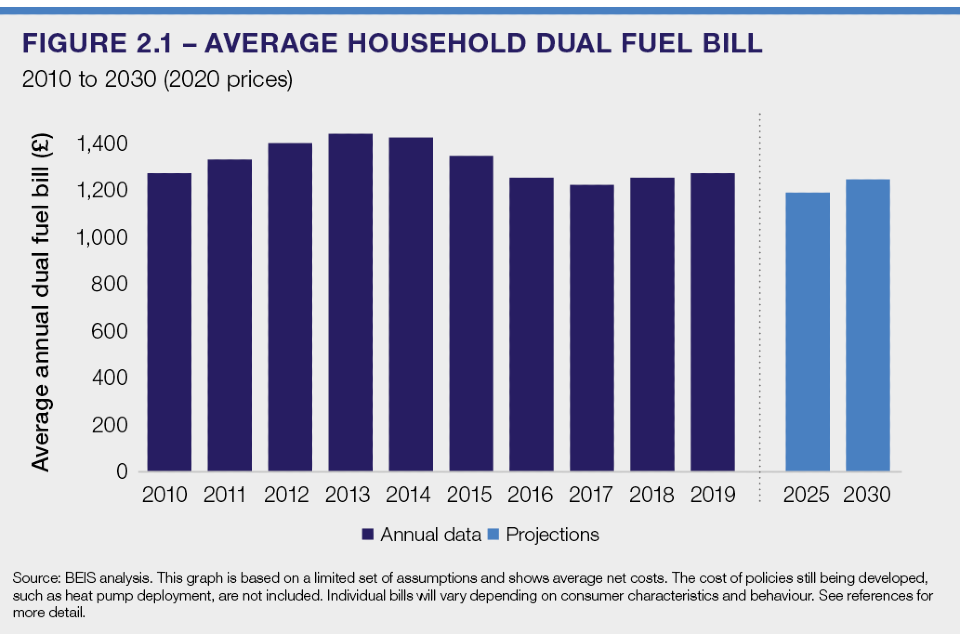

The average household’s dual fuel energy bill in 2019 was similar to 2010 (figure 2.1).

However, the underlying costs have changed. Over the past decade, electricity prices have gone up, because of rises in policy and network costs, while gas prices have fluctuated, reflecting movements in the wholesale gas price. However, consumers have used less energy, which has balanced out the cost increase.[footnote 33]

Overall, households who install energy saving measures will see significant savings and can offset the costs. Through targeting our energy saving schemes, such as extended ECO,[footnote 34] expanded WHD,[footnote 35] and the Green Homes Grant, many of the people making savings will be low-income or vulnerable households on benefits, whose homes currently have poor energy efficiency ratings. For such households, energy represents a significant share of their outgoings, so these savings can have a significant impact on their disposable income.

Our ECO and expanded WHD schemes will provide at least £4.7 billion of extra support to low-income and vulnerable households between 2022 and 2026. Under the Green Homes Grant, we expect £500 million to be spent on low-income households through Local Authority Delivery. In addition, £500 million of the £1.5 billion voucher scheme is also intended for low-income households.

Figure 2.1: Average household dual fuel bill

For example, a household in receipt of Universal Credit and living in an old, inefficient home could enjoy bill savings worth over £400, making them warmer, healthier and reducing their carbon emissions.

Over the next ten years, increases in network costs, along with funding for clean energy and supporting vulnerable households could push gas and electricity prices up. Based on the policies in this white paper with agreed funding, we estimate that household dual fuel bills will be, on average, broadly similar in both 2025 and 2030 to 2019 (figure 2.1). These policies are estimated to amount to a net increase of around 2% on average,[footnote 37] though households who take up measures stand to make material net savings. This depends on a range of uncertain and variable factors, including future fossil fuel prices and how consumers use energy. We have used a central set of assumptions for these drivers.

Energy bill components

- wholesale costs: the amount energy suppliers pay to buy gas and electricity

- network costs: the costs to build, maintain and operate the pipes, wires and cables that transport gas and electricity from producers to consumers

- supplier costs and margins: the administrative costs of running the supply business, including customer service, marketing, metering, plus profits

- policy costs: cost of programmes to save energy, reduce emissions, and provide financial support to the fuel poor

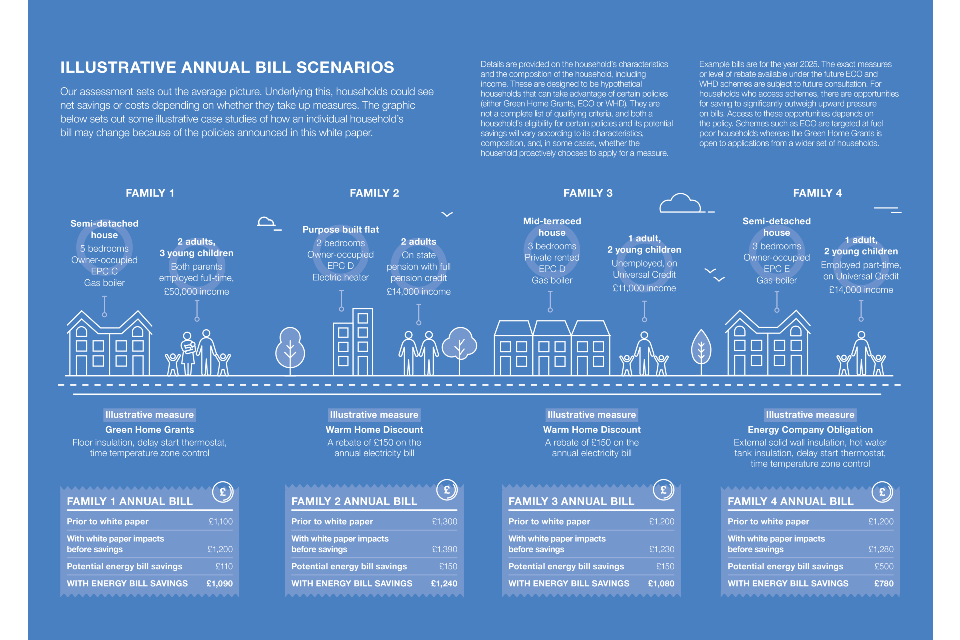

Illustrative annual bill scenarios

Our assessment sets out the average picture. Underlying this, households could see net savings or costs depending on whether they take up measures. The graphic below sets out some illustrative case studies of how an individual household’s bill may change because of the policies announced in this white paper.

Household bill comparison

Details are provided on the household’s characteristics and the composition of the household, including income. These are designed to be hypothetical households that can take advantage of certain policies (either Green Home Grants, ECO or WHD). They are not a complete list of qualifying criteria, and both a household’s eligibility for certain policies and its potential savings will vary according to its characteristics, composition, and, in some cases, whether the household proactively chooses to apply for a measure.

Example bills are for the year 2025. The exact measures or level of rebate available under the future ECO and WHD schemes are subject to future consultation. For households who access schemes, there are opportunities for saving to significantly outweigh upward pressure on bills. Access to these opportunities depends on the policy. Schemes such as ECO are targeted at fuel poor households whereas the Green Home Grants is open to applications from a wider set of households.

Our key commitments

Affordability and fairness

It matters how much consumers pay for their energy, particularly when household budgets are tight.

The government will work with the regulator, Ofgem, to take the necessary steps to help households manage their bills. We have already introduced a price cap to ensure that the market does not excessively penalise consumers who do not frequently shop around for better deals.

As we move to a clean energy system, fairness will be at the heart of our approach. Every household and business should be confident that everyone is paying their fair share of the costs of the transition. The members of the Climate Assembly UK identified “fairness within the UK, including for the most vulnerable” as one of the top 2 principles that should guide decisions around net zero.[footnote 38] We agree.

We will publish a call for evidence by April 2021 to begin a strategic dialogue between government, consumers and industry on affordability and fairness.

We will work across the sector to identify existing distortions in the system and gain insights into the trade-offs involved in the distribution of energy costs. This will allow us to take decisions on how energy costs can be allocated in a way which is fair and incentivises cost-effective decarbonisation.

The nature of costs in a smart, clean energy system will be different. The largest part of our electricity bill is the cost to our energy supplier from buying power. This cost has traditionally been determined by the underlying price of gas or coal but this is changing. Gas will set the electricity price for some years to come but, over time, will do so less frequently, as more and more wind and solar connect to the electricity system. These are technologies which do not have a fuel cost. What we are paying for is the cost of building and operating the wind or solar farms, not the fuel cost. This trend fundamentally reshapes the costs of the system we must pay for. How consumers are charged will need to reflect this.

Ensuring that costs are fairly allocated between all consumers will be a central challenge for government. We need to strike the right balance between different households, between domestic consumers and businesses, including the big energy users in industry. The way that the costs are passed through to bills can incentivise or disincentivise certain types of consumer behaviour, including how the costs of decarbonising energy are apportioned between gas and electricity bills.

This can be a particular barrier to electrifying heat, which will be crucial for the transition to low-carbon buildings (see ‘Buildings’ chapter). It will be essential to ensure that price incentives are fair and help achieve our net zero target.

We are also mindful that, as we rightly encourage households to adopt new technologies such as roof-top solar and home energy storage, this change could affect how consumers pay for their energy in a way which is unfair to others. Households which self-generate electricity and store it, even sell it back to the grid, will be able to reduce how much they pay towards the fixed costs of the electricity system, while still relying on the system when they are not self-supplying. It could leave other consumers to pay a greater share, some of whom may not be able to take advantage of new technologies.

For all these reasons, the time is now right to reflect carefully on the nature of energy costs, who pays for them and how. HM Treasury has already launched a review of how the transition to net zero would be funded and where the costs would fall. An interim report will be published in December 2020, with a view to completing the review in spring 2021. This white paper sets out what we currently do to enshrine fairness in the way consumers are treated in the energy sector and puts forward new policy proposals to go even further. Building on this foundation, we will start a conversation with consumers and the energy industry about the fairness and affordability of the cost of moving to clean energy over the long-term. We are clear that the outcome of this work is a net zero world which continues to ensure a fair distribution of costs and maintains support in society and business for our climate goals.

Rolling out smart meters

It remains our ambition to achieve market-wide roll-out of smart meters as soon as practicable, enabling homes and small businesses to access digital energy services that put them in charge of their energy use. Second generation smart meters – which are compatible with all energy suppliers from the point of install – are now being rolled out as standard across Great Britain, while the enrolment of first generation smart meters into the national communications system will ensure these stay smart when consumers switch energy supplier.

We have introduced a new smart meter obligation on suppliers, which will start in July 2021. This will drive consistent, long-term investment, by setting annual targets and providing regulatory certainty. We are committed to exploring ways to encourage consumer uptake.

We are working with industry and delivery partners to help energy suppliers develop successful strategies for consumer engagement which improve the installation and operational performance rates of new meters, while stimulating consumer demand.

To allow consumers to make the most of the data recorded by smart meters, it needs to be combined with half-hourly settlement for suppliers. This will allow households to access more real-time prices, should they wish. Most households are currently billed at a fixed price, based on an estimate of when they use electricity during the day. Half-hourly settlement provides the option for different prices in each 30-minute period of the day. Ofgem’s analysis estimates that half-hourly settlement would bring net benefits for consumers of between £1.6 billion and £4.6 billion by 2045.[footnote 39] Ofgem intend to publish their final decision in spring 2021 on how and when to implement half-hourly settlement.

Facilitating competition and tackling the loyalty penalty

We are already seeing the value of innovation in smart controls and tariffs, as well as household batteries and solar panels.

To ensure that the growth in technological innovation goes from strength to strength, we need to ensure markets provide consumers with access to the services they want and offer fair value to all consumers. This is especially pressing as the system becomes more complex. Vulnerable consumers may need additional protections appropriate to their circumstances.

Consumers who have been automatically rolled onto a default tariff when their introductory tariff ends, or who start off on an auto-roll-over tariff, such as when they move into a new house, often pay much more for their energy, even when significantly cheaper alternatives are available. Over 50% of consumers remain on default tariffs, despite almost all consumers knowing they can switch.[footnote 40] Many remain in this position for a long time, paying a ‘loyalty penalty’,[footnote 41] while other suppliers struggle to compete to provide these consumers with a better deal.

The price cap currently limits the extent of the loyalty penalty, but we believe competition is the most effective and sustainable way to keep prices low for all consumers over the long-term. Where the market and policy conditions for effective competition are not yet in place, we are prepared to ensure that proportionate price protection remains.

We have set out options for long term measures to protect consumers from the loyalty penalty in the joint government and Ofgem consultation ‘Flexible and responsive energy retail markets’ of July 2019.[footnote 42] With the measures set out in this white paper, we aim to address barriers to consumer engagement and the current nature of default tariff arrangements, the 2 leading causes of the loyalty penalty.

Opt-in switching

We will create the framework to introduce opt-in switching, consulting by March 2021 on how it should be designed, tested and incrementally scaled up.

We know from today’s energy market that, for some consumers, the existence of cheaper deals is not sufficient in itself to drive consumer behaviour. Ofgem has found in recent trials that opt-in switching and similar tools can facilitate greater consumer engagement with the energy market.[footnote 43]

We will learn from these trials and create the framework to enable the introduction of opt-in switching by 2024. This will be implemented once we have reformed the exemption that smaller energy suppliers have from paying for energy efficiency measures (ECO) and from offering a discount for customers in fuel poverty (WHD).

Default tariff arrangements and opt-out switching

We will consider how the current auto-renewal and roll-over tariff arrangements could be reformed to facilitate greater competition, consulting by March 2021 on how opt-out switching could be tested as part of any future reforms.

Default or roll-over tariffs are important for ensuring continuous supply and service for consumers, even where they have not agreed a specific deal. However, these tariffs also enable passive engagement with the market, which limits competition and allows suppliers to charge such consumers excessive prices.

We want energy markets to be truly competitive. We do not think that energy suppliers should expect to roll over or continue contracts with customers indefinitely. Where consumers do not opt-out, reforms could move consumers on default tariffs to a new, cheaper contract through a competitive process. We will test how moving consumers to new contracts, with the option to opt-out, could work best for consumers, consulting by March 2021. We will engage closely with stakeholders to consider the design of the testing, including which consumers should be targeted, how the new tariff is determined and what safeguards should be in place to ensure beneficial outcomes.

Removing market distortions

We will work with industry to reduce the barriers to consumer engagement so that more households make informed choices about the products and services they receive.

Transparency

We will ensure consumers are provided with more transparent and accurate information on carbon content when they are choosing their energy services and products, consulting on reforms in early 2021.

Smart digital technology is not just giving consumers more control, choice and flexibility in their energy use. It allows consumers to make a personal contribution to delivering a clean energy system.

So, it is important that they have clear and easily accessible information on the options to do so. We will assess how effectively the market provides consumers with clear information on costs and clean energy choices.

This will be the key to helping consumers make informed decisions. We will consult in 2021 on how to ensure consumers receive transparent information when choosing an energy product, for example quantifying the additional environmental benefits of a tariff marketed as ‘green’.

Policy obligations

We will consult on how:

- the energy supplier thresholds of ECO can be removed without incurring disproportionate costs on suppliers, including potentially introducing a buy-out mechanism as part of reforms to the scheme beyond 2022

- the energy supplier thresholds of WHD can be removed as part of reforms to the scheme beyond 2022 to ensure administrative simplicity and consistency

ECO and WHD are obligations on suppliers that tackle fuel poverty by providing targeted energy efficiency measures and discounts on bills (see ‘Buildings’ chapter for more detail).

Supplier thresholds for these schemes were introduced to avoid creating significant administrative barriers to market entry for new suppliers. The thresholds exempt suppliers with fewer customers from some of the costs to which their larger competitors are exposed. However, these thresholds may create market distortions as smaller suppliers are able to undercut other suppliers who still have to pay the costs.

For WHD, the threshold also creates barriers to switching for the fuel poor, as some suppliers are not required to offer the discount. We want to remove policy obligation thresholds but ensure that schemes can be extended, without creating significant administrative burdens for small suppliers. This will mean that fuel poor consumers who receive WHD can have greater confidence that switching to a cheaper tariff with an alternative supplier.

Retail regulatory framework

We will assess what market framework changes may be required to facilitate the development and uptake of innovative tariffs and products that work for consumers and contribute to net zero, engaging with industry and consumer groups throughout 2021 before a formal consultation.

Consumers can benefit and contribute more effectively to net zero through an energy retail regulatory framework that accommodates emerging and innovative business models. Consumers are best placed to decide which business models suit their needs through market participation, but they could include peer-to-peer trading; energy as a service, where customers buy an outcome for an agreed price, such as a guaranteed temperature at home or guaranteed level of heat pump performance, rather than paying for units of gas or electricity; or the bundling together of utilities, such as water and energy.

The market framework will need to enable innovation and competition, while protecting consumers. We will continue to review whether the current supply licence framework strikes this balance effectively. We will assess whether incremental changes, alongside wider sectoral initiatives, are sufficient or whether more fundamental changes are required.

Protecting consumers as technologies and services evolve

Consumers must be able to benefit from robust and consistent protection when engaging the energy market, no matter where they obtain their products and services.

Third party energy products and services

We will ensure the retail market regulatory framework adequately covers the wider market, consulting by spring 2021 on regulating third parties such as energy brokers and price comparison websites.

The energy market is evolving rapidly as technology advances and consumer behaviour changes. Consumers can engage in the market in new ways. When the current licensing framework was developed, the majority of consumers would engage directly with their new supplier when arranging a switch but this is less common now, as consumers increasingly use price comparison websites. Ofgem does not currently regulate third parties like energy brokers and price comparison websites and we need to ensure that consumers can be confident that they are protected when engaging with any energy product or service through these channels.

This principle of protection does not just apply to households. In its Microbusiness Strategic Review, Ofgem identified harms to microbusinesses from some brokers such as mis-selling and misrepresentation. Government and Ofgem will work together to ensure microbusinesses have appropriate protection from bad practices.

Smart appliances

We will take powers to regulate smart appliances based on principles including interoperability, data privacy and cyber security, legislating when Parliamentary time allows.

The market for smart appliances, such as smart fridges, washing machines and heating systems, is just emerging. Regulation of these devices, in particular relating to interoperability, data privacy, and cyber security, is required to support its development and to ensure that appropriate consumer protection is in place ahead of time. Devices should be able to link with any service provider’s systems so that consumers cannot be locked into a single provider. It is also important that devices are cyber secure, to ensure consumers’ data remains private and the energy system as a whole is protected. Industry is developing standards for smart appliances in line with these principles, which will be published by summer 2021.

We will ensure that the approach adopted for regulating smart appliances is compatible with the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport’s existing commitment to take powers to regulate the cyber security of consumer smart devices.

Opt-in switching trials

Since 2017, Ofgem has run trials to develop and test new prompts to increase consumer engagement. Ofgem found that customers who have not switched energy tariff for many years can be prompted to do so following simple, well designed letters and emails. The trials included over 1.1 million customers and resulted in over 94,000 of them switching to new energy tariffs, with most of them making an active choice about their energy tariff for the first time in years. In total, these customers have saved around £21.3 million between them.

The most successful trials were the opt-in collective switching trials. These removed as many steps as possible from the switching process and provided additional reassurances, such as independent support. Between 19-30% of consumers switched their tariff – 5 to 10 times higher than the control group, which had rates of 2.6-4.5%.

Our key commitments

- we will publish a call for evidence by April 2021 to begin a strategic dialogue between government, consumers and industry on affordability and fairness

- we will create the framework to introduce opt-in switching, consulting by March 2021 on how it should be designed, tested and incrementally scaled up

- we will consider how the current auto-renewal and roll-over tariff arrangements could be reformed to facilitate greater competition, consulting by March 2021 on how opt-out switching could be tested as part of any future reforms

- we will ensure consumers are provided with more transparent and accurate information on carbon content when they are choosing their energy services and products, consulting on reforms in early 2021

- we will consult on how the energy supplier thresholds of ECO can be removed without incurring disproportionate costs on suppliers, including potentially introducing a buy-out mechanism as part of reforms to the scheme beyond 2022

- we will consult on how the energy supplier thresholds of WHD can be removed as part of reforms to the scheme beyond 2022 to ensure administrative simplicity and consistency

- we will assess what market framework changes may be required to facilitate the development and uptake of innovative tariffs and products that work for consumers and contribute to net zero, engaging with industry and consumer groups throughout 2021 before a formal consultation

- we will ensure the retail market regulatory framework adequately covers the wider market, consulting by spring 2021 on regulating third parties such as energy brokers and price comparison websites

- we will take powers to regulate smart appliances based on principles including interoperability, data privacy and cyber security, legislating when Parliamentary time allows

Chapter 2: Power

Our goal

Electricity is a key enabler for the transition away from fossil fuels and decarbonising the economy cost-effectively by 2050.

We will:

- accelerate the deployment of clean electricity generation through the 2020s

- invest £1 billion in UK’s energy innovation programme to develop the technologies of the future such as advanced nuclear and clean hydrogen

- ensure that the transformation of the electricity system supports UK jobs and new business opportunities, at home and abroad

The strategic context

>50% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from electricity generation between 1990-2019

5x renewables capacity has grown 5-fold since 2010

9GW increase in operational offshore wind since 2010

Decarbonising the power sector has led the UK’s efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

In 1990, electricity generation accounted for 25% of UK emissions. In 2018, it was only 15%.[footnote 46] 30 years ago, fossil fuels provided nearly 80% of electricity supply.[footnote 47] Today, the country gets over half of its power from low-carbon technologies.[footnote 48] The rapid growth of renewables has a been a critical feature of this transformation. Renewable capacity has grown 5-fold since 2010, driven by the deployment of wind, solar and biomass. The UK had 10GW of operational offshore wind by 2019, up from just over 1GW in 2010.[footnote 49]

Figure 3.1: Change in power supply

Renewables now account for over one third of electricity generation, up from 7% in 2010. Yet, this green revolution has been delivered without disruption to the reliability of our electricity supply and the scale of deployment has contributed to a significant reduction in the cost of renewables. Increasingly, green power is the cheapest power.[footnote 50]

Building on this foundation, we need to go further. With the exception of Sizewell B and Hinkley Point C, which is under construction, all of the existing nuclear power plants are due to have ceased generating by the end of 2030. We have already committed to ending coal in the electricity mix no later than 2025.

Today, as a signal of our further ambition and to encourage other countries along the path to phasing out coal, we are publishing a consultation over the option to bring forward our coal closure date to 2024.[footnote 51] Subject to this consultation, we will introduce legislation to give legal effect to the end date.

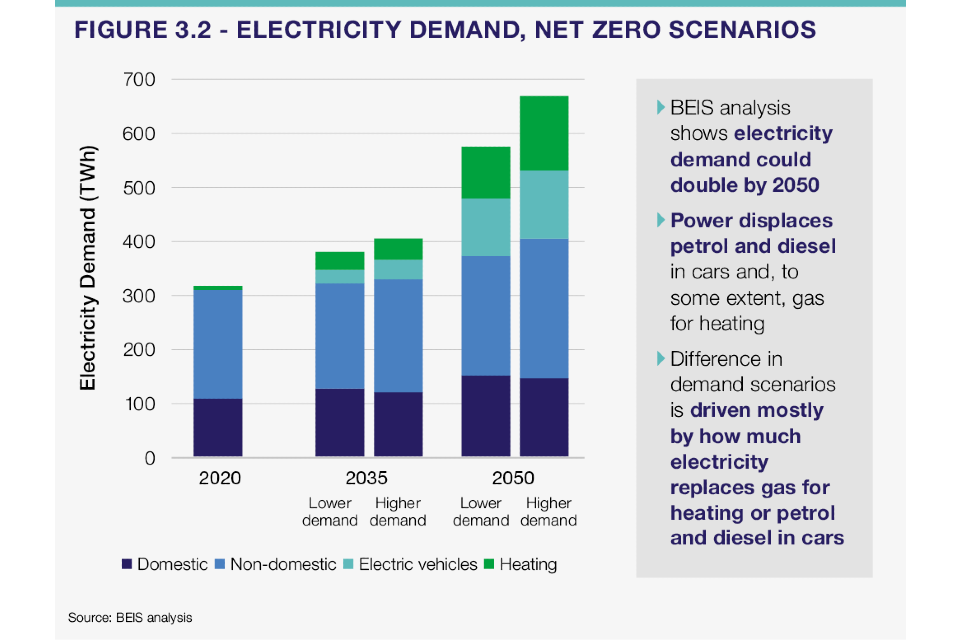

While retiring capacity will need to be replaced to keep pace with existing levels of demand, our modelling suggests that overall demand could double out to 2050. This is because of the electrification of cars and vans and the increased use of clean electricity replacing gas for heating. As a result, electricity could provide more than half of final energy demand in 2050, up from 17% in 2019.[footnote 52]

Figure 3.2: Electricity demand, net zero scenarios

This would require a 4-fold increase in clean electricity generation with the decarbonisation of electricity increasingly underpinning the delivery of our net zero target.

Given the pivotal role of electricity in delivering net zero emissions, we must aim for a fully decarbonised, reliable and low-cost power system by 2050. Low emissions in power does not necessarily mean higher costs. Carbon intensity, the amount of CO2 emitted to generate 1kWh of electricity, can fall to very low levels without costs rising significantly. This will depend on the level of demand, and the cost and availability of other low-carbon technologies, particularly low-cost clean hydrogen.

Our understanding of what is required from the electricity sector to support the delivery of net zero emissions will change over time.

Our views will be informed by what we learn about the costs of decarbonising other sectors of the economy and by the costs and availability of negative emissions technologies, such as Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS) or Direct Air Carbon Capture and Storage (DACCS).

We are not targeting a particular generation mix for 2050, nor would it be advisable to do so. We have already reduced power sector emissions 58% between 2010 and 2018,[footnote 53] and to stay on a course for a fully decarbonised system we will continue that progress through the 2020s and have an overwhelmingly decarbonised power system in the 2030s.

The electricity market should determine the best solutions for very low emissions and reliable supply, at a low cost to consumers.

Figure 3.3: UK emissions, net zero scenario

Competition should be a spur to greater investment in technologies which are cheaper and more efficient; or to the innovation which will reduce the costs of existing options. We have seen very rapid falls in the costs of renewables over the last 5 years and want to maintain the market conditions which stimulate these cost reductions. The government’s role is to ensure a market framework which promotes effective competition and delivers an affordable, secure and reliable system, consistent with net zero emissions by 2050. This market framework should enable the deployment of the most efficient, low-cost technologies and mitigate delivery risk associated with a particular technology. We will intervene to address any potential market failures, as government did through the introduction of the Capacity Market, to ensure enough supply at periods of peak demand. We will continue to invest in innovation which helps commercialise new technologies and reduce overall technology costs.

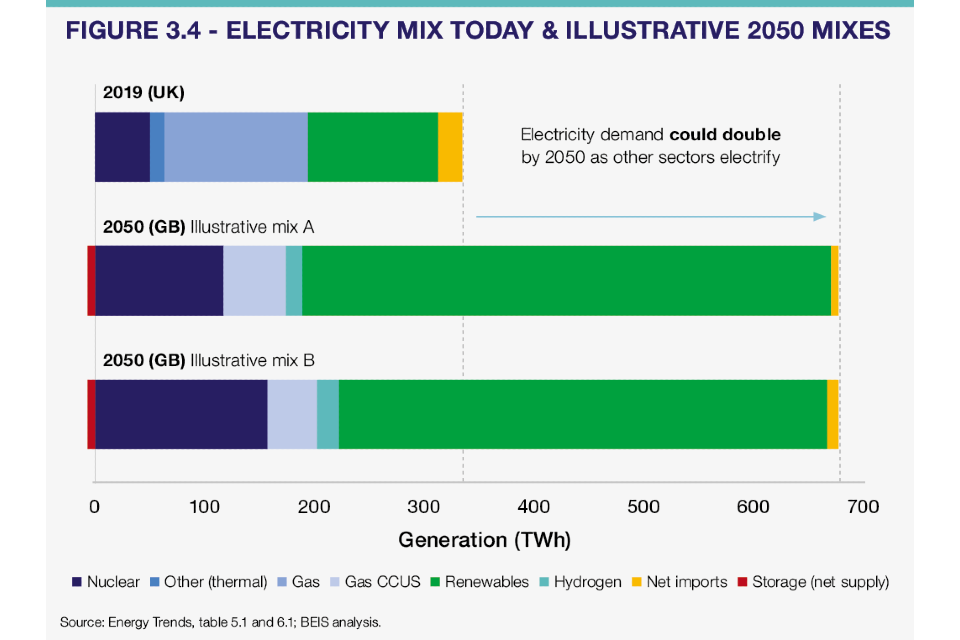

While we are not planning for any specific technology solution, we can discern some key characteristics of the future generation mix. A low-cost, net zero consistent system is likely to be composed predominantly of wind and solar. But ensuring the system is also reliable, means intermittent renewables need to be complemented by technologies which provide power, or reduce demand, when the wind is not blowing, or the sun does not shine. Today this includes nuclear, gas with carbon capture and storage and flexibility provided by batteries, demand side response, interconnectors (see ‘Energy system’ chapter) and short-term dispatchable generation providing peaking capacity, which can be flexed as required.

By 2050, we expect low-carbon options, such as clean hydrogen and long-duration storage, to satisfy the need for peaking capacity and ensure security of supply at low cost, likely eliminating the reliance on generation from unabated gas.

Figure 3.4: Electricity mix today and illustrative 2050 mixes

Figure 3.4 illustrates how the system could meet a doubling of demand, while reducing emissions. It shows just 2 of many scenarios which decarbonises electricity to very low levels of emissions at low cost. It serves to emphasise how much additional generation capacity we will need to build and how much electricity it produces to satisfy high levels of demand. Very different mixes can also provide low-cost solutions for the same demand scenario.

We are publishing the details of our electricity system analysis alongside this white paper.[footnote 54] We have modelled almost 7,000 different electricity mixes in 2050, for 2 different levels of demand and flexibility, and 27 different technology cost combinations. It has produced a dataset comprising of over 700,000 unique scenarios, allowing us to identify common features of a low emissions, low-cost electricity system.

The analysis allows us to better prepare for an electricity system which is consistent with net zero emissions, even if we do not know the precise generation mix in 2050. It informs the actions we need to take to support the deployment of clean electricity technologies, including how we can direct our innovation support most effectively. We can target the technologies which have a key role in the system of the future, such as low-carbon peaking capacity and long-duration storage, which enable us to integrate high volumes of low-cost intermittent generation.

Our key commitments

Affordable clean electricity

This white paper sets out the actions which we are taking to put the country on the path to a low-cost, clean electricity system by 2050.

It will comprise the technologies which allow us to drive deep reductions in carbon emissions at a low cost, while maintaining the reliability and resilience of the system. Our actions are a strong signal to project developers and the wider investor community about the government’s commitment to delivering clean electricity. This should stimulate the continued deployment of key low-carbon technologies in the near term, while encouraging innovation in the technologies of the future which offer the greatest potential to reduce costs.

Renewables

We will target 40GW of offshore wind by 2030, including 1GW floating offshore wind, alongside the expansion of other low-cost renewable technologies.

A highly competitive Contracts for Difference (CfD) allocation round in 2019 led to the procurement of 5.5GW of offshore wind and 275MW of remote island wind, at strike prices around £40/MWh (2012 prices) for projects expected to start generating electricity by 2024.[footnote 55] This contrasts with prices for offshore wind of £150/MWh for projects which became operational in 2017.[footnote 56]

As announced in the Prime Minister’s Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution, we will continue to hold regular CfD auction rounds every 2 years to bring forward a range of low-cost renewable technologies. The next auction in late 2021 will be open to onshore wind, solar photovoltaics and other established technologies, as well as offshore wind. Subject to sufficient projects coming through the planning pipeline to maintain competitive tension, we plan to double the capacity awarded in the last round with the aim to deploy around 12GW of low-cost renewable generation. Onshore wind and solar will be key building blocks of the future generation mix, along with offshore wind. We will need sustained growth in the capacity of these sectors in the next decade to ensure that we are on a pathway that allows us to meet net zero emissions in all demand scenarios.

Following our recent Call for Evidence on the potential of marine energy projects, we have set an ambition of deploying 1GW of floating offshore wind by 2030, supported by CfDs and innovation funding. Acting now will drive higher volumes of deployment in the 2030s and beyond, subject to cost reductions. We will work closely with the devolved administrations, the Crown Estate and Crown Estate Scotland to address issues such as seabed leasing and protecting the marine environment and to ensure the UK captures the economic benefits of deploying the technology. This will provide the foundation for a sustainable, competitive supply chain and enable floating offshore wind projects to scale up and accelerate cost reduction. We will consider the role of wave and tidal energy, following further evaluation of the commercial and technical evidence. We will also identify and utilise synergies between hydrogen and the deployment of offshore wind.

It is vital that CfDs offer value for money to consumers and continue to deliver low prices. We will structure the 2021 and future auctions to keep the CfD allocation process highly competitive, supported by a number of technical changes to the auction. Alongside this white paper, we are issuing a new Call for Evidence seeking views on how the CfD scheme could evolve beyond the 2021 auction, including how longer-term changes to the CfD or wider electricity market design can enable the effective integration of increasing renewables capacity.[footnote 57]

We want to understand how generators can best be exposed to market signals which stimulate innovation and incentivise generators to minimise the overall system costs of large amounts of renewables. We will also be asking about the broader evolution of the electricity market (see ‘Energy system’ chapter). We will seek a balance between options for further reform of the market with maintaining the success of the CfD in deploying low-cost renewables at scale.

We will establish a Ministerial Delivery Group, which brings together the relevant government departments to oversee the expansion of renewable power in the UK. This group will provide the cross-government coordination and collaboration necessary to achieve our ambition for renewable electricity. It will tackle barriers such as the impact of wind turbines on radar systems, maintaining a flourishing and biologically diverse marine environment and the development of appropriate network infrastructure to support future renewables deployment. We will also work to reduce consenting delays and ensure that planning guidelines and environmental regulations are fit for purpose. The Ministerial Delivery Group will make use of existing cross-government mechanisms, such as the Offshore Wind Enabling Actions programme, a £4.3 million initiative to be run jointly by Defra and BEIS and funded by HM Treasury (HMT).

Power CCUS

We will support the deployment of at least one power CCUS project, to be operational by 2030, and put in place the commercial framework required to help stimulate the market to deliver a future pipeline of power CCUS projects.