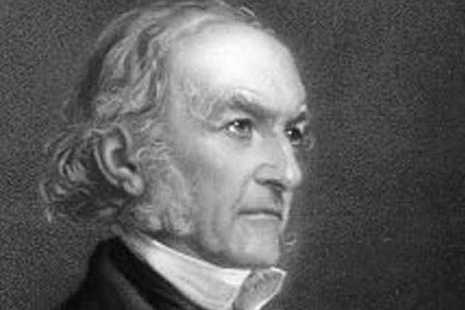

William Ewart Gladstone

Liberal 1868 to 1874, 1880 to 1885, 1886 to 1886, 1892 to 1894

“The love of freedom itself is hardly stronger in England than the love of aristocracy.” Queen Victoria described him as a “half-mad firebrand” while to a large part of the British working classes he was the "Grand Old Man". Four times prime minister, Gladstone provoked strong reactions.

Born

29 December 1809, Liverpool

Died

19 May 1898, Hawarden Castle, Flintshire

Dates in office

1868 to 1874, 1880 to 1885, 1886 to 1886, 1892 to 1894

Political party

Liberal

Major acts

Representation of the People Act 1884: increased the number of men who were eligible to vote in an election. Gave the vote to men paying an annual rent of at least £10 or all those holding land valued at £10. (Of course, women were still ineligible). Government of Ireland Bill 1886 and 1893 (aka Home Rule Bills): attempts by Gladstone to allow a system of home rule in Ireland. The first bill was rejected by the Commons, the second was vetoed by the Lords. Thus, it never became law.

Interesting facts

He served as Prime Minister for 4 separate periods. More than any other Prime Minister.

Biography

Gladstone was elected Tory MP for Newark in December 1832, aged 23, with ultra-conservative views.

In Parliament he spoke out against the abolition of slavery, because his family used slaves on their West Indian plantation. He also opposed the recent democratic electoral reforms.

Gladstone’s talent for public speaking caught the attention of Robert Peel, then Prime Minister, who made him a Junior Lord of the Treasury and later Under-Secretary at the Colonial Office. He followed Peel in resigning in 1835, and spent the following 6 years in Opposition.

In 1840 Gladstone began his ‘rescue and rehabilitation’ of London’s prostitutes. Even while serving as Prime Minister in later years, he would walk the streets, trying to convince prostitutes to change their ways. He spent a large amount of his own money on this work.

In 1845 he resigned over Peel’s decision to make a grant to a Roman Catholic theology school in Ireland. This caused some confusion, as he was known to favour the policy himself. He rejoined Peel’s government later that year as Colonial Secretary.

When the Tory party broke apart in 1846, Gladstone followed Peel in becoming a Liberal-Conservative, now believing strongly in free trade. In 1847 he returned to Parliament as MP for Oxford University, having lost his Newark seat.

In 1858, he turned down a position in the Earl of Derby’s Conservative government, because he no longer believed in protectionism and did not want to work with Disraeli. Instead he became Chancellor of the Exchequer in Aberdeen’s coalition of Whigs, Peelites and radicals in 1863, where he proved himself to be an outstanding minister.

He was Chancellor again under Palmerston between 1859 and 1865, though their relationship was an uncomfortable one, and yet again under Russell from 1865 to 1866. During these years he became persuaded of the case for a wider franchise, saying: “Every man who is not presumably incapacitated by some consideration of personal unfitness or of political danger is morally entitled to come within the pale of the Constitution.”

In 1867, Gladstone became leader of the Liberal party following Palmerston’s resignation, and became Prime Minister for the first time the following year. His policies were intended to improve individual liberty while loosening political and economic restraints.

Ireland was another area of Gladstone’s concern. He successfully passed an act to disestablish the Church of Ireland and an Irish Land Act to tackle unfair landlords, but was defeated on an Irish University Bill proposing a new university in Dublin open to Catholics and Protestants.

But in 1874 a heavy defeat at the general election led to his arch-rival Disraeli becoming Prime Minister. Gladstone retired as leader of the Liberal Party, but remained an intimidating opponent, attacking the government fiercely over their weak response to Turkish brutality in the Balkans, known as the Eastern Crisis.

In 1880 he became Prime Minister for a second time, much against Queen Victoria’s will. Her dislike of him was strong, complaining that he “addresses me as though I were a public meeting”. For 2 years he combined the offices of Prime Minister and Chancellor of the Exchequer.

Yet trouble overseas created problems. He failed to rescue General Gordon from Khartoum, leading to the loss of British control in Sudan, and a dent in Gladstone’s popularity. Critics reversed his ‘GOM’ nickname (for ‘Grand Old Man’) to ‘MOG’ (‘Murderer of Gordon’).

In 1885 the government’s Budget was defeated, prompting him to resign, with Lord Salisbury becoming Prime Minister. Gladstone declined an earldom offered by Queen Victoria, preferring to remain in office.

In February 1886, aged 76, he became Prime Minister for the third time. Working in alliance with the Irish Nationalists, he immediately introduced an Irish Home Rule Bill, proposing a parliament for Ireland. It was defeated, and he lost the General Election held in July 1886.

Gladstone devoted the next 6 years to convincing the British electorate to grant Home Rule. Campaigning on the issue, the Liberals won the 1892 election, and he returned for a fourth administration. He once more introduced the Irish Home Rule Bill, but it was rejected by the Lords. He resigned in March 1894, having failed to retain the support of his Cabinet.

Gladstone died on 19 May 1898 from cancer, which started behind the cheekbone and spread across his body. He was buried in Westminster Abbey.