Introducing a total online advertising restriction for products high in fat, sugar and salt (HFSS)

Updated 24 June 2021

Introduction

On 27 July 2020 the government launched its tackling obesity strategy, to empower adults and children to live healthier lives. Obesity is one of the greatest long-term health challenges this country faces.

Today, around two-thirds (63%) of adults are above a healthy weight and of these, half are living with obesity. We also have 1 in 3 children leaving primary school already overweight or living with obesity.

In the tackling obesity strategy, launched by the Prime Minister, government made clear that helping people to achieve and maintain a healthy weight is one of the most important things we can do to improve our nation's health. Not only because obesity is associated with reduced life expectancy and is a risk factor for a range of chronic diseases,[footnote 1] but there is now evidence that people who are overweight or living with obesity are at greater risk of being seriously ill, and dying from COVID-19.

Therefore, it is more important than ever to support the nation in reducing overweight and obesity and help change attitudes and drivers around food and exercise. We also know from the evidence that tackling obesity requires a wide range of interventions that cover both our diet and our physical activity, and that everyone has a role to play.

As set out in the government’s Sporting Future strategy, it is vital that everyone has opportunities to be active, for both their physical and mental wellbeing. In particular, our school sport and activity action plan sets out how we intend to help increase children’s activity levels, ensuring children enjoy being physically active and retain active habits throughout their lives. This work complements the tackling obesity strategy, and shows how we can help and support everyone to eat better and move more.

Lots of people who are overweight or living with obesity want to lose weight but find it hard. Many people have tried to lose weight but struggle in the face of endless prompts to eat – on TV, online and on the high street. The factors that influence obesity are complex and there is no single solution, we need to help support people by making the healthiest option the easiest option.

In the strategy, government announced a number of measures to help people live healthier lives. These included a new 'Better Health' campaign, expanding weight management services, consulting on front of pack labelling, requiring large out of home food businesses to add calorie labels to the food they sell, consulting on introducing calorie labelling on alcohol, and legislating to end the promotion of foods high in fat, sugar or salt (HFSS) by restricting volume promotions and placement in certain locations.

In addition to these measures, government announced its intention to ban HFSS products being shown on TV and online before 9pm. This will help limit the amount of HFSS advertising children see and is easy for parents and guardians to understand. We also said that we want to go further online, and will consult on how we would introduce a total online HFSS advertising restriction. This document outlines our proposal for a total online HFSS advertising restriction and asks for your views on how we can design a restriction to effectively reduce the amount of HFSS advertising children are exposed to.

We see this as an extension of the previous 2019 consultation and are now consulting only on matters relating to online HFSS advertising. We plan to publish a consultation response following this online only consultation.

Background

From 18 March 2019 to 10 June 2019 the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) and the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) held a public consultation 'Introducing further advertising restrictions on TV and online for products high in fat, sugar and salt (HFSS)' and accompanying impact assessment. That consultation asked for views on whether to go further by extending advertising restrictions on broadcast and online media, including consulting on watershed restrictions, in order to reduce children's exposure to HFSS advertising and should be read in conjunction with this latest consultation.

Childhood obesity remains one of the biggest health problems this country faces, with 1 in 3 children leaving primary school already overweight or living with obesity. It is also a major challenge for adults. Around two-thirds (63%) of adults are above a healthy weight, and half of these are living with obesity. The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has brought this into sharper focus as evidence shows that people who are overweight or living with obesity who contract COVID-19 are at greater risk of being seriously ill and dying from the virus. As excess weight is one of the few modifiable factors for COVID-19, government has been clear that there is an urgent need to help support people to achieve a healthier weight and do all that we can to improve the health of our nation to better equip us for the future.

In addition to COVID-19, obesity is also a risk factor for a range of chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, at least 12 kinds of cancer, liver and respiratory disease,[footnote 2] and it can impact on mental health.[footnote 3]

It is estimated that obesity-related conditions are currently costing the NHS £6.1 billion per year. The total costs to society of these conditions have been estimated at around £27 billion per year with some estimates placing this figure much higher.

Regular overconsumption of food and drink high in calories, sugar and fat is one of the key factors leading to weight gain and, over time, obesity. We make numerous decisions about the food we eat, and every day we are presented with encouragement and opportunity to eat the least healthy foods. We know that advertising can shape children's food choices. Evidence suggests that children's exposure to HFSS product advertising can affect what they eat and when they eat. This can happen both in the short term, increasing the amount of food children eat immediately after being exposed to a HFSS advert,[footnote 4],[footnote 5] and in the longer term by shaping children's food preferences from a young age.[footnote 6]

While the evidence is not conclusive,[footnote 7],[footnote 8],[footnote 9] it's possible that restricting HFSS advertising exposure could also influence adult purchases and consumption. Further restrictions on HFSS advertising could therefore help reduce overconsumption and generate significant additional health benefits. Industry may also decide to reformulate their products in order to make them healthier which would enable them to continue advertising the product. If companies chose to do this, it could further increase the health benefits.

People who live in deprived areas have higher COVID-19 diagnosis and death rates and are more likely to be living with childhood and adult obesity. Studies suggest that children from the most deprived households spend more time online than those from the most affluent, and that HFSS adverts have a greater impact on those children who are already overweight or obese than non-overweight children.[footnote 10]

This indicates that children in more deprived communities are more likely to benefit from a reduction in HFSS advertising exposure.

Progress since our previous consultation and the rationale for a total online HFSS advertising restriction

As part of the tackling obesity strategy we committed to taking further action on protecting children from HFSS exposure on TV and online. We want to go further and are therefore consulting on our proposal to introduce a total restriction for these adverts online. We believe a total restriction online is necessary to:

- futureproof the policy against changes in children's media habits

- account for a lack of transparency and independent data; and

- address potential issues with the way HFSS adverts are targeted away from children online.

Children's media habits and HFSS advertising online

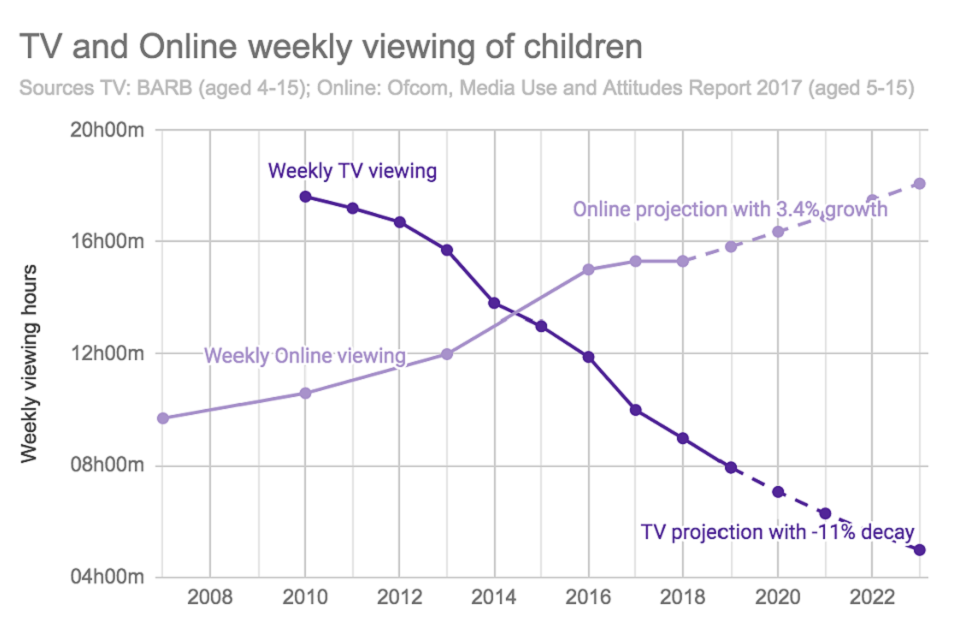

5 to 15 year-olds spend around 20 minutes more online per day than in front of a TV set and evidence suggests that this shift will continue (figure 1). Evidence submitted to our consultation indicates that food and drink advertising has mirrored that shift, with a 450% increase in spend on online display between 2010 and 2017.[footnote 11]

Figure 1 TV and online weekly viewing of children

Children’s weekly viewing online has been increasing steadily since 2007, and is expected to continue to increase by 3.4% per year.

Sources: TV: BARB, 2019 (aged 4 to 15); Online: Ofcom, Media Use and Attitudes Report 2018 (aged 5 to 15)

As a reflection of these trends and taking into account the evidence we received as part of last year's consultation we have revised upwards our estimates of the amount of HFSS advertising that may be seen by children online. We now estimate around 15.1 billion child HFSS impressions online in the UK in 2019, up from our original estimate of 0.7 billion in 2017. This significant uplift is due to methodological changes in how the size of the online is estimated. A full explanation of the changes to the methodology can be found in the accompanying evidence note.

We acknowledge that it is currently not possible to take into account fully the effect of current restrictions around advertising HFSS products to children, and our own approach was based principally on the size of the market (noting that the estimate is informed by application of Kantar's survey-based Crossmedia tool, which thereby introduces an element of real world experience). The increased estimates of children’s online media consumption strengthens the case for government acting to reduce children's exposure to HFSS online and demonstrates the rising risk of children's exposure in this media where children are spending an increasing amount of time.

Transparency, availability of data and targeted advertising

We set out previously our concerns regarding dynamically served advertising[footnote 12] and recent evidence has only served to reinforce those concerns:

- the use of devices, online profiles and accounts shared between adults and children, and the communal viewing of content ‒ research from the ASA last year found that an avatar mimicking the profile of a child and adult sharing a device was served a similar proportion of HFSS ads as avatars mimicking the profile of an adult

- the false reporting of users' ages ‒ Ofcom data indicates that levels of misreporting of age on social media have remained steady over the past 10 years ‒ around 20% of 8 to 11s report having social media accounts, despite the minimum age for such accounts being 13

- predictive inaccuracy in using interest-based factors and other behavioural data as a proxy for age ‒ research from the ASA last year found that 2.4% of all ads served to avatars mimicking the profiles of a range of age groups were HFSS, compared with 2.3% of all ads served to avatars mimicking only the profiles of children

While online targeting may be directionally accurate, it is of limited specific reliability. It is therefore likely that children are seeing HFSS adverts where this is not the intent of the regulatory system.

Following our previous consultation, the government wants to go further than the current regulatory approach and ensure there is sufficient reliable evidence with regard with regard to online advertising. This is underlined by the absence of any independent, comprehensive, industry-recognised, gold-standard and publicly available means of audience measurement. This may add a degree of variation and discretion to compliance, dependent on the accuracy of the tools used by each advertiser, intermediary and platform. The use of different compliance tools, standards and methods across the online advertising environment, plus a lack of transparency in reporting of data, means that it can be difficult to identify online audiences with certainty.

This lack of transparency ‒ reflecting not only limited independent public data, but also widespread personalisation of advertising, the significant scale of digital marketing and the relative novelty of ASA rules which were only introduced in 2017 ‒ presents challenges in reliably understanding the extent to which children are exposed to HFSS advertising online, the media with which they engage with most as set out above. The lack of transparency also presents challenges for parents and guardians in being able to prevent children from seeing HFSS advertising online.

Government's concern extends also to static advertising in general audience media, where the ASA's current restriction on HFSS advertising by a 25% child audience threshold means a significant number of children may still be exposed to these adverts.

Underpinning this is evidence of continued inadvertent breaches of HFSS rules. 33% of the websites and 95% of the YouTube channels identified as being aimed at children and included in last year's ASA HFSS research project served HFSS adverts. Between April and June this year, in another online monitoring sweep, the ASA found HFSS advertising on 49% of children's websites and 71% of YouTube channels aimed at children under review[footnote 13]. Twenty-nine different HFSS advertisers were responsible for the various breaches in this latest study, contrasting with just 6 advertisers in breach of the rules across e-cigarettes, alcohol, weight control/slimming and gambling sectors, and indicating a widespread problem rather than any more isolated failure. It is important to acknowledge that work is underway to prevent breaches in all sectors.

Evidence to the contrary of these concerns in response to our consultation was limited. One respondent highlighted that current rules require advertisers to use multiple evidence sources where possible to ensure they are compliant, and to exercise caution in cases where robust evidence is not available. Another highlighted that dynamically served advertising is not strictly automated, and that humans make conscious decisions about when and where adverts are shown online, control the buying process, and specify how ads should be targeted, with numerous points in the process where regulatory compliance is checked before, during and after a campaign. We do not consider that this addresses fundamental concerns about flaws in the system by which advertising is targeted, which are magnified as children spend more time online, and further undermined by a lack of transparency.

A solution building on existing audience-based restrictions is therefore too dependent on an opaque and potentially porous system, over which the advertiser may sometimes have limited control, and applied to an advertising category which is unique in being age restricted in advertising but not otherwise (unlike, for example, alcohol which is age restricted for purchase and consumption).

In addition, an approach where compliance relies on the quality and reliability of targeting information and the ability to target certain advertisements away from children, may engage issues of competition. Effective and widespread targeting tools and methods would be necessary to ensure a level playing field. Some platforms may be better disposed to implement time-based targeting already, which may confer an advantage over those facing operational or practical burdens in implementing a time-based restriction. Measures to enable compliance would have to be universally accessible and compatible in order to minimise potential risks of market distortion and competitive advantage.

Given the scale of the obesity problem we face, the government believes that a total online restriction on HFSS advertising is required to effectively reduce children's online HFSS exposure and signal to industry, consumers and parents the government's determination to tackle it.

Interaction with 2019 consultation

Objective of consultation

Our objectives remain unchanged since the 2019 consultation. The main aim remains to reduce children's exposure to HFSS advertising, in order to help reduce their overconsumption of HFSS products. As part of this we also want to drive reformulation of products by brands, ensure that any potential future restrictions would be proportionate and targeted to the products of most concern to childhood obesity, and ensure that any potential future restrictions would be easily understood by parents, so that they can be supported in making healthy choices for their families.

The online watershed

Responses from industry to our previous consultation highlighted concerns that an online watershed may not be an appropriate tool for content regulation. Respondents highlighted that TV is a linear medium that pushes content and advertising to a mass audience, in a manner traditionally dictated by time of day. Online, however, is an on demand medium commonly targeted to individual users, where time of day is neither a determining factor in what content is consumed, nor a proxy for establishing who is likely to consume it.

Responses also underlined some of the practical challenges of an online time-based restriction as set out in our previous consultation, such as:

- the potential for a time-based restriction to confer inadvertently a competitive advantage on some platforms, such as those that already provide advertisers with the tools to identify and time limit dynamically served advertising

- the potential for an online watershed to be more likely to shift online HFSS adverts to post-9pm than an equivalent shift on TV advertisements under a TV watershed

- potential variations in the effects or impacts that a time-based restriction may have on different types and formats of advertising

While we are not pre-judging our response to that consultation, these concerns warrant consideration of an online total restriction of HFSS advertising, as a more effective solution.

Responses submitted to previous consultation

We have considered the responses and evidence submitted as part of the 2019 consultation on further advertising restrictions on TV and online and will publish a consultation response following this online only consultation.

Please do not resubmit any evidence that you have already sent as part of the previous consultation. We have reviewed those responses in full and together with the responses to this consultation they will be taken into account when determining the best course of action.

As a result we are not inviting views as part of this consultation on the following aspects as they have been considered as part of the previous consultation:

- extending to other forms of media ‒ as announced in tackling obesity, government will be taking forward further restrictions on TV and online. The policy decision on whether to implement a TV watershed is out of scope of this consultation. The treatment of brand advertising and rules on the content of HFSS advertising and rules relating to advertising of HFSS products in programming or content of particular appeal to children remain out of scope

- food and drink products in scope ‒ in the previous consultation, government proposed that HFSS products would be classed as in scope if they were a) in scope of the sugar and calorie reduction programmes and the SDIL and b) failed to pass the 2004/05 NPM. This remains our proposed approach. We will confirm the final policy position in our consultation response later this year

- implementation ‒ as part of tackling obesity we announced that we will implement any restrictions to HFSS advertising on TV and online at the same time, and we will aim to do this by the end of 2022. Further detail on the means of implementation and timelines will be set out in the responses to our HFSS advertising consultations

Introducing an online total HFSS advertising restriction ‒ policy proposal

This section outlines the proposed design of an online total HFSS advertising restriction. Please see the consultation questions in annex A.

Advertising in scope

We propose that the restrictions apply to all online marketing communications that are either intended or likely to come to the attention of UK consumers and which have the effect of promoting identifiable HFSS products, while excluding from scope:

- marketing communications in online media targeted exclusively at business-to-business. We do not seek to limit advertisers' capacity to promote their products and services to other companies or other operators in the supply chain

- factual claims about products and services

- communications with the principal purpose of facilitating an online sale

The scope of the restriction would include, but is not limited to, for example:

- commercial email, commercial text messaging and other messaging services

- marketers' activities in non-paid for space, for example on their website and on social media, where the marketer has editorial and/or financial control over the content

- online display ads in paid-for space (including banner ads and pre/mid-roll video ads)

- paid-for search listings; preferential listings on price comparison sites

- viral advertisements (where content is considered to have been created by the marketer or a third party paid by the marketer or acting under the editorial control of the marketer, with the specific intention of being widely shared. Not content solely on the grounds it has gone viral)

- paid-for advertisements on social media channels - native content, influencers etc

- in-game advertisements

- commercial classified advertisements

- advertisements which are pushed electronically to devices

- advertisements distributed through web widgets

- in-app advertising or apps intended to advertise

- advergames

- advertorials

Factual claims

We recognise that companies should be able to make available factual information about their products. Therefore we propose that advertisers remain able to feature such information on their own websites or other non-paid-for space online under their control, including their own social media channels.

We consider that factual claims include but are not limited to:

- the names of products

- nutritional information

- price statements

- product ingredients

- name and contact details of the advertiser

- provenance of ingredients

- health warnings and serving recommendations

- availability or location of products

- corporate information on, for example, the sales performance of a product

However, we note in this context the regulatory challenges arising from having to make a distinction between factual claims and promotional claims, and the inherently shareable and engaging nature of social media content. This is highlighted by recent partially upheld ASA rulings against 4 e-cigarette advertisers in December 2019 which concluded in all cases that the advertisers should take steps to ensure that claims made on their social media channels should only be distributed to those actively following those channels and should not be seen by other users.

We therefore propose that any advertisers[footnote 14] which sell or promote an identifiable HFSS product or which operate a brand considered by the regulator to be synonymous with HFSS products should be required to set controls which ensure that their posts regarding HFSS products can only be found by users actively seeking them on the advertisers own social media page. This could be achieved, for example, by ensuring that the privacy settings on their social media channels are set so that their content appears on that page only.

Online sales

We also want to ensure that any advertiser who uses the internet to conduct transactions of their products is allowed to continue selling their products online. We therefore propose any platform whose principal function is the buying or selling of products, including food and drink, is exempt from the proposed restriction. This includes websites, social media channels, apps ‒ or dissociable part of those platforms, including also email, text or push notifications directed to customers who have chosen to opt-in to these communications.

Audience measurement and the treatment of BVoD platforms

As noted above one of the key drivers for government proposing a total online restriction is the absence of any independent, comprehensive, gold-standard and publicly available means of audience measurement online. This is in contrast to TV, where Broadcasters Audience Research Board (BARB) data provides a level of assurance to advertisers which is not widely available online. A broadcaster-led initiative to deliver multiple-screen programme viewing figures (Project Dovetail) now means that broadcast video on demand (BVoD) platforms can depend on the same standard of audience measurement as linear broadcast. We propose applying a watershed to the adverts shown instream during programming on BVoD platforms to mirror our approach to linear TV, separate to the approach for other online media.

Liability

Here we seek to build on existing regulatory structures in order to minimise disruption to industry and regulators. We also want to ensure that online advertising regulation sufficiently incentivises compliance and drives rapid remedial action.

We will appoint a statutory regulator with overall responsibility for the regulation of the restriction, with discretionary powers to take effective action against advertisers who breach the rules, especially in cases of more serious or repeat breaches. We propose that the day-to-day responsibility for applying the rules, considering complaints, provisioning guidance and training material to industry would remain with the ASA, recognising their expertise and experience in regulating advertising.

We propose that advertisers are liable for compliance with a total online HFSS advertising restriction.

In addition we want to consider whether other actors in the online advertising ecosystem should have responsibility for advertising that breaches an online restriction. We envisage that the nature of this responsibility would depend on the level of control which the actor had over the advertising that was served on their sites or placed through their ad networks.

We consider that there is scope to introduce such requirements through specific legislation that prohibits these actors from running advertising that breaches the restriction.

We also recognise that there is scope for legislation to set out a requirement to introduce measures appropriate to the level of control that the actor has over advertising in order to prevent the dissemination of advertising in breach of the restriction. The regulator would then be responsible for ensuring compliance with and enforcement of such appropriate measures. Guidance on appropriate measures would be developed in consultation with industry and other stakeholders in an open and transparent way, with the regulator ultimately responsible for determining the content.

We will consider the use of a requirement for the takedown of advertising that breaches the restriction after it has been brought to the relevant ad networks' attention. This would not affect protections under the UK's intermediary liability regime which limits liability for illegal third party content hosted on online services until the service provider has received notification of its existence and they have subsequently failed to remove it from their services in good time.

Enforcement

We want to ensure that the enforcement powers of the statutory regulator are designed and used in a way that incentivises compliance and allows for rapid remedial action.

We propose that the day-to-day responsibility for applying the restriction, considering complaints about advertising that breaches the restriction, provisioning guidance and training material to the advertising industry would be given to the ASA, recognising their expertise and experience in regulating advertising.

In line with the current regulatory regime we propose that breaches would be resolved in line with current ASA policy of responding to individual complaints and promoting voluntary cooperation with the restriction. If this approach failed or advertisers were committing repeated or severe breaches relating to HFSS marketing material, they would face stronger penalties through the statutory backstop. We would envisage that these would include civil sanctions, including the ability to issue fines in defined circumstances and tied to defined metrics.

To support any potential requirements on in scope online service providers, we will consider whether it is necessary for the statutory regulator to have powers in relation to the oversight of any appropriate measures. These powers might include (but are not limited to):

- requiring evidence of effective maintenance, review and enforcement of the service provider's appropriate measures, which should reflect guidance issued by the regulator in its codes of practice

- requiring evidence of the number of adverts that are being placed in breach of the restriction, who those advertisers are and action taken to prevent adverts that breach the restriction being placed

- requiring evidence of the processes that the service provider has in place for reporting content in breach of the restriction, the number of reports received and how many of those reports led to action

We envisage that the statutory regulator would not be expected to respond to individual complaints about failures to implement appropriate measures, but would have a role more focused on monitoring and review to ensure that appropriate measures are in place. They would be able to work with the ASA to identify areas or online service providers that require intervention. The regulators would also have a discretionary power to impose civil fines for breaches.

The imposition of civil fines by the statutory regulator would open to challenge through normal court procedures.

We note also in this context, the challenges of applying statutory regulation to persons overseas. It is our intention to restrict the HFSS adverts seen by children in the UK. Given the global nature of online media platforms and advertisers, we welcome views on the extent to which an online total restriction on HFSS advertising in the UK could be made to apply to online advertising served in the UK, but originating from advertisers or intermediaries based overseas. We would also be interested to hear views on whether this restriction may disproportionately affect UK-based companies.

Additional considerations

Public sector equality duty

As part of the consultation, we are inviting views on the impact of these advertising restrictions on people with protected characteristics and steps that could be taken to mitigate the impact, against the government's duties under the Equality Act 2010.

Socioeconomic considerations

In addition to the protected characteristics, we also want to consider the potential for these advertising restrictions to reduce inequality in health outcomes experienced by different socioeconomic groups.

How to respond to the consultation

The consultation will run for 6 weeks. Our preferred method of response is via SurveyOptic, the government's consultation hub. A summary of the consultation questions has also been provided in annex A.

If you do wish to send an email response, please send those to: childhood.obesity@dhsc.gov.uk

We will publish the government's response to this consultation on the GOV.UK website, summarising the responses received and setting out the action we will take, or have taken.

Annex A: consultation questions

1. Do you support the proposal to introduce a total online HFSS advertising restriction?

Yes/No/I don't know

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

Scope

2. We propose that the restrictions apply to all online marketing communications that are either intended or likely to come to the attention of UK children and which have the effect of promoting identifiable HFSS products, while excluding from scope:

- marketing communications in online media targeted exclusively at business-to-business. We do not seek to limit advertisers' capacity to promote their products and services to other companies or other operators in the supply chain

- factual claims about products and services

- communications with the principal purpose of facilitating an online transaction

Do you agree with this definition?

Yes/No/I don't know

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

3. Do you foresee any difficulties with the proposed approach on types of advertising in scope?

Yes/No/I don't know

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

4. If answered yes, please can you give an overview of what these difficulties are? Please provide evidence to support your answer.

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

5. Do you agree that for the purpose of a total online advertising restriction for HFSS products, the term 'advertiser' should be defined as a natural or legal person, or organisation that advertises a product or service?

Yes/No/I don't know

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

6. Do you agree that for the purpose of appropriate measures, the term "online service providers" should include all internet services that supply services or tools which allow, enable or facilitate the dissemination of advertising content?

Yes/No/I don't know

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

7. Our proposed exemption for factual claims about products and services would include content on an advertiser's social media. Do you agree with this approach?

Yes/No/I don't know

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

8. We propose that any advertisers which sell or promote an identifiable HFSS product or which operate a brand considered by the regulator to be synonymous with HFSS products should be required to set controls which ensure that their posts regarding HFSS products can only be found by users actively seeking them on the advertisers own social media page. This could be achieved, for example, by ensuring that the privacy settings on their social media channels are set so that their content appears on that page only. Do you think this would successfully limit the number of children who view this content?

Yes/No/I don't know

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

9. In your sector or from your perspective, would a total restriction of online HFSS advertising confer a competitive advantage on any particular operator or segment of the online advertising environment?

Yes/No/I don't know

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

10. If answered yes, are there steps that could be taken when regulating an online restriction to reduce the risk of competitive distortions arising?

Yes/No/I don't know

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

11. We are proposing that broadcast video on demand (BVoD) is subject to a watershed restriction as Project Dovetail will mean they have BARB equivalent data. Do you know of other providers of online audience measurement who are able to provide the same level of publicly available assurance with regard to audience measurement?

Yes/No/I don't know

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

12. If answered yes, do you think that platforms or advertisers using those forms of audience measurement should be subject to a similar approach as BVoD?

Yes/No/I don't know

Enforcement and liability

13. What sanctions or powers will help enforce any breaches of the restriction or of the appropriate measures requirements by those in scope of this provision?

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

14. Should the statutory "backstop" regulator for HFSS marketing material be:

a) a new public body

b) an existing public body

c) I don’t know

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence.

Should the final proposals lead to the creation of new central government arm’s length bodies, then the usual, separate government approval process would apply for such entities. This equally applies to proposals elsewhere in this document.

15. If answered b, which body or bodies should it be?

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

16. Do you agree that the ASA should be responsible for the day-to-day regulation of a total online HFSS advertising restriction?

Yes/No/I don't know

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

17. Do you agree with our proposal that advertisers are liable for compliance with a total online HFSS advertising restriction.

Yes/No/I don't know

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

18. Do you consider that online service providers should be prohibited from running advertising that breaches the restriction or should be subject to a requirement to apply appropriate measures?

a) Prohibited

b) Subject to appropriate measures

c) Neither

d) I don't know

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence.

19. If answered b, please expand on what you consider these measures should be.

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

20. Do you consider that the sanctions available (voluntary cooperation and civil fines in instances of repeated or severe breaches) are sufficient to apply and enforce compliance with a total online HFSS advertising restriction?

Yes/No/I don't know

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

21. Do you consider that the imposition of civil fines by the statutory regulator is sufficient to enforce compliance with the appropriate measures requirements?

Yes/No/I don't know

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

22. Would a total restriction on HFSS advertising online have impacts specifically for start-ups and/or SMEs?

Yes/No/I don't know

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

23. What, if any, advice or support could the regulator provide to help businesses, particularly start-ups and SMEs, comply with the regulatory framework?

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

24. We note the challenges of applying statutory regulation to overseas persons. It is our intention to restrict the HFSS adverts seen by children in the UK. From your sector or from your perspective do you think any methods could be used to apply the restriction to non-UK online marketing communications served to children in the UK?

Yes/No/I don't know

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

25. Do you see any particular difficulties with extending the scope to non-UK online marketing communications as well as UK communications?

Yes/No/I don't know

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

26. Do you see any difficulties with the proposed approach in terms of enforcement against non UK based online marketing communications as opposed to UK based ones?

Yes/No/I don't know

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

27. Do you think these restrictions could disproportionately affect UK companies?

Yes/No/I don't know

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

Public sector equality duty

28. Do you think that a total restriction on HFSS advertising online is likely to have an impact on people on the basis of their age, sex, race, religion, sexual orientation, pregnancy and maternity, disability, gender reassignment and marriage/civil partnership?

Yes/No/I don't know

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence. Please state which protected characteristic/s your answer relates to.

29. Do you think that any of the proposals in this consultation would help achieve any of the following aims?

- Eliminating discrimination, harassment, victimisation and any other conduct that is prohibited by or under the Equality Act 2010

- Advancing equality of opportunity between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and persons who do not share it?

- Fostering good relations between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and persons who do not share it?

Yes/No/I don't know

Please explain which aims it would help achieve and how

Could the proposals be changed so that they are more effective? Please explain what changes would be needed

Socio-economic impact

30. Do you think that the proposals in this consultation could impact on people from more deprived backgrounds?

Yes/No/I don't know

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

Annex B: evidence note consultation questions

31. Do the calculations in the evidence note reflect a fair assessment of the transition costs that your organisation would face?

Yes/No/I don't know

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

32. Is the time allocated for businesses to understand the regulations a fair assessment?

Yes/No/I don't know

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

33. Are there any ongoing costs that your organisation would face that are not fairly reflected in the evidence note?

Yes/No/I don't know

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

34. Is the assessment on the number of online impressions a fair assessment?

Yes/No/I don't know

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

35. It is estimated that a significant proportion of HFSS advertising online will be displaced to other forms of media. Do you think the level of displacement is correct?

Yes/No/I don't know

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

36. It is assumed that the level of displacement to other forms of media would be the same under the options outlined in the evidence note. Would you agree with this approach?

Yes/No/I don't know

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

37. Do you have any evidence on how competition may vary between the options in the evidence note? This can be any form of competition, for example competition between HFSS brands or competition between other forms of advertising.

Please explain your answer and provide relevant evidence

38. Do you have any additional evidence or data that would inform:

a) our understanding of children's exposure to online adverts?

b) how different types of online advert (for example static display and video adverts) can have different effects on children's calorie consumption?

c) the estimates for additional calorie consumption caused by HFSS product advertising online?

d) the long-term impact of HFSS advertising exposure during childhood (for example on food behaviours and preferences later in life)?

e) the health benefits of either option in the evidence note?

f) how consumer spending habits will change as a result of these restrictions?

g) how advertisers might adapt their marketing strategies in response to further restrictions in HFSS advertising?

h) the impacts on the price of advertising slots, and how this might vary under both options?

Please provide the relevant evidence or data

Annex C: disclosure of responses

Data protection

The information you provide in responses to this consultation is managed in accordance with DHSC’s information charter and DCMS’s information charter. The information you supply will be processed by the Obesity Food and Nutrition policy team in DHSC in accordance with the Data Protection Act 2018 and the General Data Protection Regulation.

The government's response to the consultation will summarise feedback received through the consultation using aggregated data and will not contain any personal information that could identify you. We will not publish the names or contact details of respondents and will not include the names of organisations responding, unless we have express permission to do so.

Outside of specific exemptions under the legislation, your personal data shall be retained for no longer than the purposes for which it is being processed, as in line with the privacy notice.

Disclosure of responses

Please note that, as a public body, DHSC or DCMS may be required by law to publish or disclose information provided in response to this consultation in accordance with access to information obligations, for example:

The Freedom of Information Act 2000

The Data Protection Act 2018

The General Data Protection Regulation

By providing personal, confidential, commercial or intellectual property information for the purpose of the public consultation exercise, it is understood that you consent to its disclosure and publication in such circumstances. Confidential information is disclosed at the respondent's risk; we would encourage any confidential or sensitive information to be marked as such in your response.

Under the Data Protection Act 2018 (and the General Data Protection Regulation), you have certain rights to access your personal data and have it corrected, restricted or erased (in certain circumstances), and you can withdraw your consent to us processing your personal data at any time. If you decide to withdraw your response, you will need to contact DHSC using our web contact form.

Complaints

You have the right to lodge a complaint to the Information Commissioner's Office about our practices, to do so please visit the Information Commissioner's Office website.

Information Commissioner's Office

Wycliffe House

Water Lane

Wilmslow

Cheshire

SK9 5AF

Email: casework@ico.org.uk

Telephone: 0303 123 1113

Textphone: 01625 545 860

Monday to Friday, 9am to 4:30pm

References

-

Guh et al. (2009) The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: A systematic review and meta-analysis, BMC Public Health ↩

-

Guh et al. (2009) The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: A systematic review and meta-analysis, BMC Public Health. ↩

-

Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, Stijnen T, Cuijpers P, Penninx BWJH, et al. (2010) Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Archives of General Psychiatry 2010;67(3):220-9 ↩

-

Halford JC et al. (2007). Beyond-brand effect of television (TV) food advertisements/commercials, in Public Health Nutrition 11(9):897-904 ↩

-

Halford JC, Gillespie J, Brown V, Pontin EE, Dovey TM. (2004). Effect of television advertisements for foods on food consumption in children. Appetite. Apr 1;42(2):221-5. ↩

-

Hastings G, Stead M, McDermott L, Forsyth A, MacKintosh AM, Rayner M, Godfrey C, Caraher M, Angus K. (2003). Review of research on the effects of food promotion to children. London: Food Standards Agency. Sep 22. ↩

-

Zimmerman FJ, Shimoga SV. The effects of food advertising and cognitive load on food choices. BMC Public Health. 2014 Dec;14(1):342. ↩

-

Harris JL, Bargh JA, Brownell KD. Priming effects of television food advertising on eating behavior. Health psychology. 2009 Jul;28(4):404. ↩

-

Koordeman R, Anschutz DJ, van Baaren RB, Engels RC. Exposure to soda commercials affects sugar-sweetened soda consumption in young women. An observational experimental study. Appetite. 2010 Jun 1;54(3):619-22. ↩

-

Russell, Simon J., Helen Croker, and Russell M. Viner. (2018). "The effect of screen advertising on children's dietary intake: A systematic review and meta‐analysis." Obesity Reviews. ↩

-

AA/WARC Expenditure Reports 2017 and 2019 ↩

-

i.e. advertising served specifically to a selected audience group. This includes, for example, programmatic display, native advertising in social media or pre/mid-roll video advertising. ↩

-

Based on 49 websites and 7 YouTube channels. ↩

-

a company, person, or organisation that advertises a product or service ↩