The Self-Employment Income Support Scheme final evaluation

Published 17 July 2023

A joint evaluation by HM Treasury (HMT) and HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) of the Self-Employment Income Support Scheme (SEISS).

Acknowledgements

HMT and HMRC would like to give thanks to our peer reviewers, Robert Joyce from the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), and Iven Stead and Tim Blackman from the Department for Transport (DfT), who reviewed a draft of this evaluation. All decisions made about subsequent revisions to the evaluation were made by HMT and HMRC and all conclusions are our own.

Glossary

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| SEISS | The Self-Employment Income Support Scheme was set up by the government to provide financial support to self-employed individuals in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. |

| Self-employed | A person is self-employed if they run their business for themselves and take responsibility for its success or failure. Self-employed individuals are not paid through Pay As You Earn (PAYE), and they do not have the rights and responsibilities of an employee. Someone can be both employed and self-employed at the same time, for example if they work for an employer during the day and run their own business in the evenings. |

| Income Tax Self Assessment (ITSA) | Self Assessment is a system HMRC use to collect Income Tax from those who do not have tax deducted automatically from wages, pensions and savings. People and businesses with other income (including COVID-19 grants and support payments) must report it in a tax return for the year the income was received. |

| Eligible population | Self-employed individuals who were assessed for the SEISS and deemed potentially eligible according to the policy criteria. To be eligible to claim their business must have been adversely affected by the COVID-19 outbreak and they must intend to continue to trade. |

| Assessed as ineligible population | Individuals who were assessed for eligibility for the SEISS grants but were deemed ineligible on the grounds of either earning more than £50,000 in trading profits, earning £0 or less in trading profits or having non-trading income as a larger proportion of total income than trading income. It does not include individuals who did not complete a self-employed schedule on their tax return, such as those paid through PAYE, company owner managers or directors of limited companies. |

| Newly self-employed eligible population | Individuals who started trading in the 2019 to 2020 tax year and who were assessed for the SEISS and deemed potentially eligible according to the policy criteria only for the fourth and fifth grants. To be eligible to claim their business must have been adversely affected by the COVID-19 outbreak and they must intend to continue to trade. |

| Error and fraud | Error is non-deliberate over or under-payment, typically due to mistake, misunderstanding or misapplication of rules. Fraud is any deliberate omission, concealment, or misinterpretation of information, or the false or deceptive presentation of information or circumstances in order to gain an advantage. |

| PAYE | Pay As You Earn is the system for deducting and collecting Income Tax and National Insurance contributions from employment income. |

| RTI | RTI (Real Time Information) is the system used by employers to report to HMRC each time they pay their employees. Under RTI, information about PAYE, NICs and other deductions is transmitted to HMRC by the employer every time an employee is paid. |

| Agent | Someone who acts on behalf of a self-employed person to help them meet their tax obligations, including accountants, tax agents or other professionals. |

| RBT | Reasonable Belief Test. Claimants were asked to declare that as a result of the reduced activity, capacity or demand suffered, they reasonably believed there would be a significant reduction in their trading profits in the relevant period compared to what they would have expected in the absence of the COVID-19 pandemic. This applied from the third SEISS grant. |

| FID | Financial Impact Declaration (often referred to as a ‘turnover’ test). The Financial Impact Declaration (FID) was introduced for the fifth SEISS grant to determine the value of the grant for those who had become self-employed or a member of a partnership before the 2019 to 2020 tax year. The FID required a comparison of turnover in the ‘pandemic year’ with an earlier representative period. Where turnover fell by 30% or more a higher rate grant was paid. Other eligible claimants received the lower rate grant. |

| NPIs | Non-pharmaceutical interventions. These were behavioural and social interventions applied as part of the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. These are measures intended to reduce COVID-19 transmission by reducing contact rates in the general population, for example national lockdown and social distancing measures. |

| Counterfactual assessment | A counterfactual assessment models what would have happened in the absence of the SEISS. |

| Tax gap | The tax gap is the difference between the amount of tax that should, in theory, be paid to HMRC, and the amount that is actually paid. |

| Deadweight | Desired policy outcomes that would have taken place without the intervention under consideration. |

| Value for Money | A way of assessing the value from government spending, and the optimal use of resources to achieve the intended outcomes. |

| CJRS | The Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme. The scheme was launched in April 2020 and aimed to protect jobs affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. The scheme initially offered employers the opportunity to apply for a grant to fund the wages of their employees who were on furlough, equivalent to 80% of usual wages up to £2,500 per month. |

| The Green Book | The Green Book is guidance issued by HMT on how to appraise policies, programmes and projects. It also provides guidance on the design and use of monitoring and evaluation before, during and after implementation. It is published on GOV.UK. |

Executive summary

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic had far-reaching consequences for the UK labour market, households, businesses, and the economy more widely – some of which are still being felt. The Self-Employment Income Support Scheme (SEISS) was announced on 26 March 2020 as part of the government’s economic response to the COVID-19 pandemic, bringing broad parity with the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS) which provided support for the employed.

The primary objective of the SEISS was to support self-employed individuals whose businesses had been adversely affected by COVID-19 restrictions. It sought to quickly support individuals most reliant on their self-employed income, who would have lost out financially due to COVID-19, enable self-employed people to remain in business, and provide support broadly equivalent to the CJRS.

The SEISS sought to do this in a way that targeted support as much as possible on those who needed it most and minimise the risk of error and fraud. However, the policy design needed to adapt to the circumstances of the self-employed cohort which presented different challenges to the employed population. The different characteristics of the self-employed population and the nature of the data HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) collects meant there were different issues to consider in the policy design.

The SEISS was delivered as a series of 5 grants available between May 2020 and September 2021, that self-employed individuals could claim based on their Self Assessment tax records. It was delivered at pace, with the first grant opening for applications on 13 May 2020. The scheme aimed to support those most reliant on self-employed income by setting criteria based on annual trading profits and the share of income from self-employment.

As the effects of COVID-19 eased and the economy reopened, further criteria were introduced to ensure the scheme was more targeted towards those most affected by the disruptions. These included a Reasonable Belief Test (RBT) from the third grant onwards where claimants had to declare that they reasonably believed their trading profits were reduced as a result of COVID-19, and a turnover test on completion of a Financial Impact Declaration (FID), for the final grant which opened on 29 July 2021.

Across the lifetime of the scheme, a total of 2.9 million eligible self-employed individuals claimed SEISS grants, totalling £28.1 billion.

This final evaluation completes the government’s evaluation of the scheme following best practice from the Green and Magenta books, with any deviation from this guidance clearly highlighted. A Value for Money (VfM) assessment following the ‘4 Es’ structure that is widely used when assessing this subject is also included.

An interim evaluation published in October 2022 set out initial impact findings on the first 3 grants of the scheme, alongside an evaluation of the processes by which the scheme was delivered and accessed by claimants, covering the entire lifespan of the scheme. The final evaluation covers the impacts across all SEISS grants and also assesses the scheme’s VfM, including a consideration of deadweight, and lessons learned. It has been peer reviewed by 3 external reviewers to provide independent challenge.

Key findings

1) The SEISS was good VfM, with a positive net benefit to society of £14.2 billion and a social benefit to cost ratio of 3.8: 1.

This evaluation uses the principles of the Green Book to estimate all the costs and benefits to society of the SEISS and finds that the SEISS provided a Net Present Value (NPV) of £14.2 billion in current prices. The total benefits created by the scheme are estimated to be worth £19.3 billion, with an accompanying social cost of £5.1 billion. These estimates have some uncertainties and further detail is provided in chapter 5, but overall, the assessment finds that the scheme represents good VfM. A proportion of the initial cost of grants (£28.1 billion) was reclaimed through additional tax and National Insurance contributions (NICs) paid, and benefit payments avoided, meaning the scheme’s effective net cost was £19.5 billion.

The SEISS was primarily an income support scheme, designed to support those most in need and to enable them to remain in business. By supporting claimants’ businesses, it had wider indirect benefits as those businesses in turn sustained additional business activity that would not have existed without the scheme. These benefits are estimated at between £0.2 billion and £1.5 billion. Additionally, wider economic activity was supported such as consumer spending as a result of the scheme successfully supporting incomes. These additional effects are estimated at around £8.5 billion. Targeting of the SEISS at those with self-employed profits of no more than £50,000 per year through the eligibility criteria also had an equity benefit estimated at £10.5 billion, based on the standard Green Book method.

Given the extraordinary nature of the COVID-19 pandemic and the uncertainty it created, it was important that support was provided at pace to provide security and reassurance to self-employed individuals who were impacted by COVID-19 and facing an uncertain economic shock. A complicated application process and eligibility criteria could have unintentionally denied support to those who needed it or put them off from claiming the support they required.

The lack of timely self-employment data held by HMRC also meant that there were challenges in balancing the need for cost-effectiveness with ensuring those who most needed support could get it. Eligibility to the SEISS was based on matching claims against information already held on HMRC’s system in order to combat the risk of error and fraud, and improve the ease of making claims. The eligibility rules were tightened over time as more data became available. However, there is some evidence of support going to those who did not necessarily require it. Potential deadweight in the scheme is estimated at around £2.8 billion, although this is likely to be a slight over-estimate due to limitations of the methodology.

Additionally, the eligibility criteria for the SEISS excluded some groups such as those whose trading profits just failed to meet the requirement to have more than 50% of total income from trading profits, or those who were newly self-employed in 2019 to 2020. A lesson learned from the SEISS is that improved data and more timely reporting of self-employed profits could have led to improved targeting of the scheme, a reduction in deadweight and the inclusion of some groups who were not able to access the scheme. Whilst targeting mechanisms were introduced over time as the path of the COVID-19 pandemic became clearer, better data on self-employed business performance and the impact on different sectors may have allowed for more targeted support to be introduced more quickly and in a more effective way.

The government has committed to further action to identify data gaps to help its ability to understand the self-employed population. HMRC ran a data consultation between 20 July and 12 October 2022 and published a Summary of Responses which also includes proposed next steps. This could give policy makers more options in the future. The government have also set out plans for the introduction of Making Tax Digital for Income Tax from April 2026, which will begin to provide a more up-to-date data picture of the income and expenditure levels of self-employed individuals. The government will continue to review the data it collects to ensure future policy measures requiring economic support are effectively targeted whilst also balancing the cost of collection.

2) The SEISS was designed and implemented swiftly. The scheme was easy to understand, and the claim process was simple.

HM Treasury (HMT) and HMRC worked together to design and implement the SEISS, at the same time as the CJRS was being delivered. It was important to deliver support to as many self-employed people who needed it as quickly as possible. While Self Assessment tax data provided the best available evidence to assess eligibility for the SEISS, it is significantly less timely than the Pay As You Earn (PAYE) data that was used for the CJRS. Self Assessment tax returns are filed annually, with trading profits reported with a time lag.

To protect against fraud risks, for the first 3 SEISS grants, only those who traded in the tax year 2018 to 2019, were eligible to apply, which meant newly self-employed were not eligible for the SEISS at first. When 2019 to 2020 Self Assessment tax return data became available, the newly self-employed in this tax year and those newly eligible based on this additional trading profits data were brought into the scheme’s eligibility rules.

Payments were made quickly following the launch of the scheme: individuals were invited to apply on a specified date between 13 May 2020 and 18 May 2020, based on their Unique Tax Reference number. By 25 May 2020, 88% of claims for the first SEISS grant had been paid. 99.4% of SEISS claims were paid within the government’s target of 6 working days from application.

According to HMRC research there were high levels of claimant satisfaction with the SEISS claim process, with 96% of claimants rating their overall experience of applying for the SEISS as either good or very good. Claimants were highly positive about the application process, with 90% feeling most aspects were clear. A lesson learnt from the design and implementation of the SEISS is the benefit of simple scheme rules enabling fast and efficient delivery. For any future similar scheme, the government may want to reconsider customer eligibility reviews and a pre-population process for taxable grants.

Full details of the process evaluation findings can be found in the SEISS interim evaluation.

3) The SEISS helped support trading profits and incomes for many self-employed people who were most affected by COVID-19.

The SEISS supported a large number of self-employed people who would otherwise have seen a drop in income. This ensured they could maintain living standards, and support their business activity to continue, despite the public health motivated restrictions on economic activity.

To ensure that economic activity continued where COVID-19 restrictions allowed, SEISS claimants were able to continue to work, start a new trade, or take up other employment, including voluntary work, provided they intended to continue trading as a self-employed individual and met all other eligibility criteria.

Self Assessment data was a critical part of the design of the SEISS, but some groups fell outside the scheme criteria. This included directors of limited companies and company owner managers who take their profits in dividends.

The scheme needed to be easy to understand and the claim process easy for eligible claimants to access the grants. This constraint on scheme design for the earlier grants meant that it was not possible to create a highly detailed scheme that could perfectly account for the wide variety of individual circumstances. This means some payments, though claimed legitimately, may have gone to self-employed individuals that did not need the support – representing a form of deadweight.

Analysis suggests the eligibility criteria put in place were set at an effective level to meet the objectives of the scheme. These thresholds were created to ensure support was provided to self-employed people most in need (with trading profits of no more than £50,000), and most dependent on their trading income (with trading profits at least equal to their non-trading income). A more complicated design based on tapered support around these thresholds would have meant claims taking longer to process and support not being paid out in time to those who needed it most.

Providing financial support could in theory lead to people reducing work effort, and therefore their income. This is known as an ‘income effect’. Using a counterfactual methodology to measure the causal impacts of the SEISS, there is some limited evidence for the existence of an income effect. Although this analysis is only valid for a limited group around the £50,000 trading profits eligibility threshold, it potentially indicates a localised behavioural effect in that income from SEISS grants may have disincentivised economic activity for individuals around this specific point in the income distribution.

It appears measures to create more targeted support were effective in reducing the provision of grant income to stronger performing self-employed businesses.

4) The SEISS helped support businesses to continue trading in the short term, however whether the scheme had a longer-term impact on business survivability is less clear.

The SEISS enabled claimants to sustain their self-employment trading activity, with fewer permanent business cessations compared to a scenario without the SEISS. Eligible claimants were found to be 2.8 percentage points more likely to remain trading in 2020 to 2021 than those assessed as ineligible at the scheme’s £50,000 average trading profits eligibility threshold for the first 3 SEISS grants. However, due to the lag in Self Assessment data, the scheme’s impact on longer-term business survivability is less clear. Using the equivalent methodology to assess the likelihood of claimants continuing to trade relative to those assessed as ineligible for the last 2 SEISS grants, the difference was small and not statistically significant.

This shows the importance of timely support for the self-employed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Preventing individuals from ceasing to trade avoided a likely period of either inactivity or unemployment, with the associated risk of long-term economic scarring.

5) Error and fraud were effectively managed throughout the lifetime of the SEISS, even as stricter eligibility criteria were introduced, to successfully target the scheme

The government effectively mitigated the risk of error and fraud through the use of data already held by HMRC.

The final estimate of overall error and fraud from the SEISS is estimated to be 5.2% (within a range of 4.2% to 6.3%). The rate of error and fraud increased in 2021 to 2022, driven by the RBT in the fourth and fifth SEISS grants. These levels compare favourably with the overall UK tax gap for Self Assessment which is estimated to be 12.4% in 2020 to 2021 and 11.2% in 2021 to 2022, and for the Self Assessment Business tax gap which is around 20%.

Due to the nature of the scheme, it was likely that the SEISS would be a target for opportunistic fraud and organised crime, and that some customers would make mistakes.

While the rates and monetary value of error and fraud for the fourth and fifth grants increased due to the self-certification elements within the RBT (introduced from the third grant onwards) and the FID introduced for the fifth grant, these changes to the policy design contributed to better targeting and an overall exchequer cost saving due to the reduced take-up and lower value of the grants paid out. The exact saving from the FID is uncertain due to other factors such as the changing economic situation but could be up to £2.5 billion when comparing the drop-off in take-up between the fourth and fifth grants.

Since the start of the compliance activity into the SEISS and up to 31 March 2023, HMRC has recovered and prevented a loss of over £466 million with compliance activity still ongoing.

Chapter 1: Introduction

1.1 Evaluation scope

The SEISS was designed to support self-employed individuals (including members of partnerships) whose self-employment activities had been adversely affected by COVID-19.

Evaluation of the SEISS is being undertaken to provide transparency and accountability around the use of public funds and to learn lessons for the future. The SEISS interim evaluation was published in October 2022. The interim evaluation provided findings for the process evaluation across all 5 grants of the scheme, and an initial impact evaluation limited to findings from the first, second and third grants only, with findings conveying the short-term impacts of the scheme.

This final evaluation provides findings on the impact of the scheme covering all 5 SEISS grants. This evaluation also includes an assessment of the VfM of the scheme, including a consideration of possible deadweight.

1.2 Evaluation objectives and questions

This final SEISS evaluation assesses the extent to which the scheme achieved its intended outcomes and the wider effects of the scheme. The key objective of the SEISS was to support self-employed individuals whose businesses had been adversely affected by COVID-19 restrictions. It also sought to quickly support individuals most reliant on their self-employed income, who would have lost out financially due to COVID-19; enable self-employed people to remain in business; minimise the risk of error and fraud; and provide support broadly equivalent to the CJRS.

The evaluation follows guidance on evaluation best-practice as outlined in the Magenta Book, and the economic principles for appraisal and evaluation as outlined in the Green Book where applicable. A draft of this evaluation was reviewed by 3 external peer reviewers who critically assessed it to provide independent oversight and quality assurance of both the evaluation approach and the robustness of the findings.

The evaluation has been conducted in-house using the expertise of the HMRC and HMT’s analytical teams. This is a common approach to government evaluation, as outlined in the Magenta Book.

Evidence used in the SEISS evaluation derives primarily from analysis of management information and Income Tax Self Assessment data. Further information about evidence sources and analytical methods is provided in the accompanying information and the counterfactual technical note to this evaluation.

1.3 Background to the SEISS

The SEISS was designed to support self-employed individuals (including members of partnerships) whose self-employment activities had been adversely affected by COVID-19 restrictions. The scheme was part of a broader COVID-19 support package that included the CJRS, uplift in Universal Credit (UC), local authority grants, government-funded loans, and tax payment deferral schemes.

The SEISS sought to ensure that support for the self-employed was equivalent to that provided for the employed population through the CJRS (with 80% of average trading profits in the first SEISS grant aligning with 80% of PAYE earnings at the start of the CJRS). The SEISS aimed to support individuals most reliant on their self-employment income, targeting those with average trading profits of no more than £50,000, and who received at least half of their income from self-employment.

The SEISS was designed and delivered using information already held by HMRC through Self Assessment. This effectively mitigated the risk of error and fraud by claimants of the SEISS by removing the need for claimants to make their own calculations or provide additional evidence to HMRC which would have increased the administrative burden of delivering the scheme. Self-certification elements such as the RBT and the FID were introduced later in the scheme, both of which increased the rate of error and fraud but were cost saving measures overall. Reliance on data already held by HMRC limited the scheme’s ability to target everyone who may have needed support, such as the newly self-employed in 2019 to 2020, those who failed to submit tax returns by the necessary deadline, or directors of limited companies who do not receive trading income.

1.4 SEISS delivery

Between May 2020 and September 2021, 5 grants were made available to those who were eligible to claim. To ensure support was delivered at speed and to minimise the risk of error and fraud, identifying the potentially eligible population and calculation of grants was based on data HMRC already held from Self Assessment tax returns. This data was used to pay grants at scale without the need for any calculations or other significant input from the majority of claimants.

The interim evaluation found within 12 days of launch, 88% of claims for the first SEISS grant had been paid, and across the whole scheme over 99% of claims were paid within 6 days. Research showed there were high levels of satisfaction with the claim process, with the vast majority of claimants (96%) rating their overall experience of applying for the SEISS as either good or very good. Claimants were also very positive about the application process, with 90% feeling most aspects were clear.

As the scheme progressed HMRC took the decision to introduce personal claim dates for the potentially eligible population. This was effective in reassuring customers that they would be able to make a claim from a particular date and in managing the high contact levels around the opening of the claim window for the earlier grants. HMRC also learned from customer feedback to send claim messages by email, to make the messages short, and to include the claim date early in the text. These are process and communication learning points for any future scheme.

To be eligible for the first, second and third SEISS grants (in 2020 to 2021), individuals were required to have filed their 2018 to 2019 Self Assessment tax return on or before 23 April 2020. The value of the first 3 grants was based on an average of the trading profits declared on tax returns covering the period 2016 to 2017 until 2018 to 2019. For the fourth and fifth grant (in 2021), the 2019 to 2020 tax return had to be filed by 2 March 2021. Using the 2019 to 2020 tax return meant eligibility for the scheme could be widened to include those newly self-employed or newly eligible who met the filing deadline.

Individuals were required to confirm that they had been adversely affected by COVID-19 for the first and second grants. For the third, fourth and fifth grants, claimants had to meet a more specific test, the RBT, declaring that they reasonably believed that any reduced activity, capacity or demand due to COVID-19 would result in a significant reduction in their trading profits compared to what they would otherwise have expected to achieve during this period. Guidance asked claimants to keep evidence of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their business.

The value of the fourth and fifth grants was based on an average of the trading profits declared on tax returns covering the period 2016 to 2017 until 2019 to 2020. Using a 4-year average of profits accounted for fluctuations in trading income and profits over time.

The value of the fifth grant was also determined by a turnover test, called the FID. This was designed to target the most generous support at those experiencing a slower recovery, while continuing to support those who were reopening their businesses. The FID meant that those declaring a larger reduction in turnover received a grant based on 80% of 3 months’ average trading profits, whereas those who suffered a smaller reduction in trading profits received a grant worth 30% of 3 months’ average trading profits.

The FID was designed using a comparison of ‘pandemic year’ turnover (April 2020 to April 2021) to turnover from an earlier year included in a filed tax return. This data was only available for the fifth grant.

To be eligible for the SEISS, individuals also needed to be trading at the point of claiming and intend to continue trading in the following tax year. Recipients of SEISS grants were allowed to continue to trade, start a new trade and/or take on other employment, but they could not permanently cease trading. When new tax data was available ahead of the fourth and fifth grants being launched, individuals who had ceased trading were no longer eligible for the scheme.

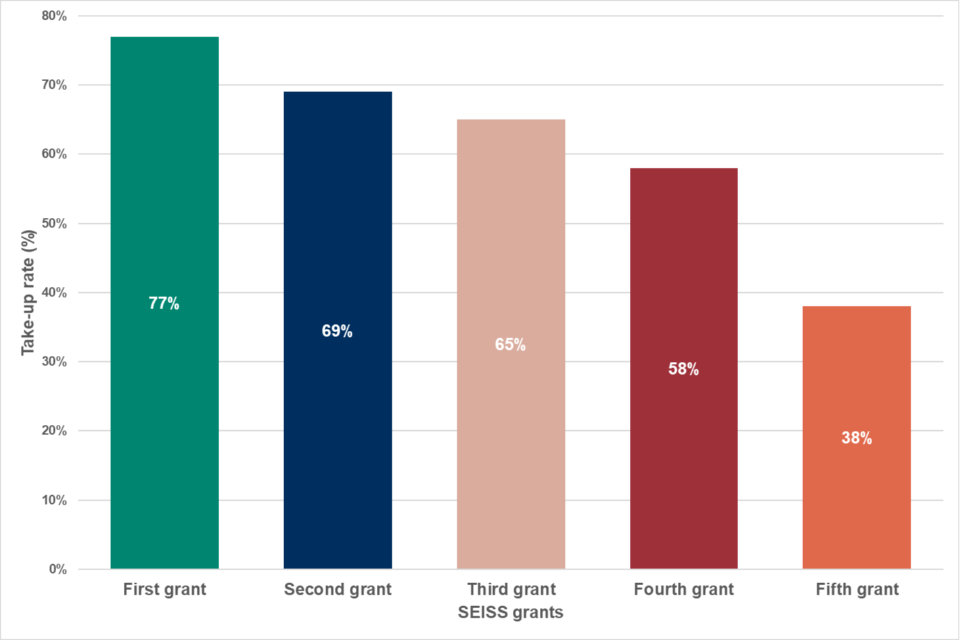

Table 1.1 summarises the total number and value of claims made for each SEISS grant. The number of claims declined with each successive grant, likely as a result of both an improving economic recovery and the introduction of the RBT and FID. The take-up rate, defined as the proportion of potentially eligible self-employed individuals for each grant who made a claim, is also shown, and declines in a similar manner.

Table 1.1 Number and value of claims for each SEISS grant

| Grants | Total number of claims (000s) | Total value of claims (£ millions) | Average value of claims (£) | Take-up rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First grant | 2,610 | 7,591 | 2,900 | 77 |

| Second grant | 2,351 | 5,931 | 2,500 | 69 |

| Third grant | 2,194 | 6,219 | 2,800 | 65 |

| Fourth grant | 1,958 | 5,518 | 2,800 | 58 |

| Fifth grant | 1,262 | 2,846 | 2,300 | 38 |

| Total across all grants | 10,374 | 28,105 | 2,700 | - |

| Total across individuals | 2,897 | 28,105 | 2,800 | - |

The eligibility rules evolved throughout the 5 iterations of the scheme to reflect the changing economic conditions and social restrictions, and to ensure the grants continued to be targeted at self-employed people most affected by the pandemic. Table 1.2 outlines the eligibility criteria throughout the 5 grants. More detail can be found in the accompanying information document published alongside this evaluation.

Changes setting out the statutory rules were introduced via the second SEISS Treasury Direction to allow claims from new parents and reservists. The changes meant that some new parents who did not submit a 2018 to 2019 tax return, or whose trading profits were less than their non-trading income in that year, may have become eligible. Similarly, self-employed reservists may have become newly eligible.

If newly eligible, these groups could claim both the first and second grant. For reservists who were assessed as ineligible on the basis of their 2019 to 2020 Self Assessment returns, HMRC assessed their eligibility and based their grant calculations on information from either their 2018 to 2019 Self Assessment return or an average of their 2016 to 2017, 2017 to 2018 and 2018 to 2019 tax returns. These groups also needed to meet the other standard eligibility criteria to secure support from the SEISS.

As stated above, the SEISS was designed to support individuals most reliant on their income from self-employment. The use of trading profits to determine eligibility meant that individuals receiving their income from other sources such as short-term employment contracts or investment income like dividends were not eligible. Individuals on a PAYE employment contract may have been eligible for the CJRS. Requiring claimants to have included trading income on their tax return was the best way of both targeting support and operationalising the SEISS at scale and at pace.

Using data outside of Self Assessment tax returns to increase eligibility would have put additional strain on HMRC’s operational capabilities, resulting in slower payments. Tax returns were a critical part of demonstrating earnings for the self-employed population and not using them would have increased the risk of error and fraud.

To ensure quick delivery of support, SEISS grants were paid via lump sums. The SEISS grants were not intended to provide a month-by-month replacement of income. Targeting and self-certification were introduced into the scheme over time with the RBT in place from the third grant onwards, and the FID for the fifth grant. Both of these were introduced to improve targeting and reduce the risk of deadweight within the scheme. However, they were not introduced sooner due to the need for support to be delivered in a broad manner that did not deter legitimate claimants in the early stages of the pandemic when economic restrictions were most severe.

Table 1.2 SEISS eligibility criteria

| Grant | Qualifying period | Criteria | Grant value % (according to turnover amount in the fifth grant) | Grant cap (£) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First grant | Impacted on or before 13 July 2020 | Business adversely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. | 80 | 7,500 |

| Second grant | 14 July 2020 – 19 October 2020 | Business adversely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. | 70 | 6,570 |

| Third grant | 1 November 2020 – 29 January 2021 |

RBT Claimant must declare that they reasonably believed that any reduced activity, capacity or demand due to COVID-19, would result in a significant reduction in trading profits, compared to what they would otherwise expect to have achieved during this period. Note: For this, and the subsequent grants, the adversely affected test also applied, but in practice it was met by someone meeting the RBT. |

80 | 7,500 |

| Fourth grant | 1 February 2021 – 30 April 2021 | RBT | 80 | 7,500 |

| Fifth grant | 1 May 2021 – 30 September 2021 |

RBT In addition: The FID was introduced to determine the amount of the grant. Individuals who suffered a 30% or smaller reduction in turnover received 30% of 3 months’ average trading profits, while the rate was 80% for those who suffered a greater reduction in turnover. |

80/30 | 7,500/2,850 |

1.5 The closure of the SEISS

The number and value of SEISS claims was highest for the first SEISS grant, corresponding to the initial wave of COVID-19, paid out between May and July 2020. Take-up declined with each successive grant as shown in figure 1.1 below. Introducing the RBT for the third SEISS grant onwards and FID for the fifth grant, alongside improving economic conditions and reduced restrictions over time, are likely to have contributed to take-up declining to 38% for the final grant.

Figure 1.1: Take-up rate of the SEISS across the 5 grants

Source: HMRC SEISS data

Sample size: Approximately 3.4 million individuals were potentially eligible for each SEISS grant, declining to 3.3 million for the final grant. Small changes in the numbers of eligible and ineligible individuals between grants occur as HMRC reviewed and monitored HMRC data systems to identify all potentially eligible individuals and to ensure that only genuine HMRC customers are invited to claim

Notes: Uses SEISS claims up to 28 October 2021, consistent with the final statistics publication

Table 1.3 Take-up rates of the SEISS grants

| SEISS grant | Take-up rate (%) |

|---|---|

| First grant | 77 |

| Second grant | 69 |

| Third grant | 65 |

| Fourth grant | 58 |

| Fifth grant | 38 |

The fifth and final SEISS grant was paid out up to the end of September 2021, coinciding with the easing of restrictions and the withdrawal of other COVID-19 support such as the CJRS. SEISS grants were subject to Income Tax and NICs and SEISS amounts were reported on individual’s Self Assessment tax returns for 2020 to 2021 and 2021 to 2022. HMRC looked into developing a process to pre-populate tax returns with the amount of grants received but it proved too complicated to deliver in time. Instead HMRC developed an ‘autocorrect’ process. This added SEISS grants to a tax return where they had not been included. However, some customers had entered the grants in the wrong boxes, so a separate process had to be designed with supporting legislation to allow customers to amend those returns by telephone.

There is ongoing work on how HMRC’s information and data-gathering powers could be updated to further enable digitalisation of services, improve compliance and reduce administrative burdens. The Tax Administration Framework Review (TAFR) is part of the government’s 10-year Tax Administration Strategy to ensure legislation, guidance and processes surrounding tax administration are suitable to deliver the digital tax system the UK will require in the future. A TAFR Information and Data Call for Evidence was published on 27 April 2023. This work focuses primarily around improving the range of information and data HMRC collects, uses and shares across government. Securing higher quality data from existing third parties could improve the accuracy of data-matching and pave the way for wider use of pre-population of Self Assessment tax returns.

Chapter 2: Error and fraud

2.1 Introduction

This chapter addresses the following evaluation question:

- what was the scale of error and fraud associated with the scheme throughout its delivery and how has HMRC dealt with it?

The SEISS interim evaluation published in 2022 provided a detailed overview of HMRC’s compliance approach, including the establishment of a Taxpayer Protection Taskforce. This information can be accessed through the interim evaluation or the 2022 to 2023 HMRC Annual Report and Accounts. This section will focus on updated methodology and findings since the SEISS interim evaluation was published in 2022.

During the design phase of the scheme, government priorities were to deliver a scheme that would provide financial support quickly to the eligible self-employed, while minimising error and fraud. The scheme therefore made use of data that HMRC already held on its system and could verify, mitigating the risk of customers manipulating evidence in order to make a claim or claim a larger value of grant.

Pre-payment controls were put in place to address notable risks, including from organised crime groups who could have hijacked customer identities or manipulated Self Assessment returns to secure grants to which they were not entitled. These controls proved very effective and resulted in less fraud across the scheme than anticipated. Compliance activity is still ongoing across all COVID-19 schemes and up to 31 March 2023, HMRC has prevented and recovered over £1.4 billion, of which £466 million relates to the SEISS.

This chapter draws evidence from the work conducted by HMRC analysts to assess the level of error and fraud for the SEISS, which used a wide-ranging evidence base including HMRC administrative data. A package of measures designed to minimise the risk of organised crime, opportunistic fraud and customer error was built into the claims process and was deployed for each iteration of the scheme.

2.2 Error and fraud estimate

The final estimate of error and fraud for the entirety of the scheme (all 5 grants) is between 4.2% to 6.3%, with a most likely value of 5.2% (£1.2 billion to £1.8 billion, most likely value of £1.5 billion). This is an increase from last year’s most likely estimate and is above the top of last year’s estimate range (2.7% to 4.8%, most likely value of 3.6%). The decomposition of the overall estimate into each individual risk is shown in the technical report on error and fraud published as part of HMRC’s Annual Report and Accounts. This also provides further detail on the methodology for calculating error and fraud.

HMRC have recently completed and reviewed the results of a Random Enquiry Programme covering the fourth and fifth SEISS grants. A statistically significant number of claims were selected at random for a post-payment compliance audit, the result of which has given new insight on the FID and the RBT. The increase in error and fraud in this year’s estimate is largely driven by the RBT in the fourth and fifth SEISS grants.

HMRC also has more complete data from Self Assessment tax returns covering the whole of 2020 to 2021 and 2021 to 2022 which gives a more comprehensive understanding of the claimant population.

Updated estimates have been published in the 2022 to 2023 Annual Report and Accounts along with an updated technical publication with more detail on the final estimates.

The interim evaluation suggested the reason for the increase in the error and fraud rate for the later grants was likely to be due to some individuals anticipating the eligibility criteria and therefore manipulating information on their 2019 to 2020 tax return, as well as the introduction of the FID for the fifth grant. The original estimate for the error and fraud associated with the FID was 0.6 percentage points of the 3.6% total estimate. This has since been revised to 0.3 percentage points of the updated 5.2% total estimate. While there were taxpayers who had a discrepancy between the turnover reported on the Self Assessment tax return and the FID, the Random Enquiry Programme found that there were instances where this could be explained, and taxpayers were found to be compliant.

Although the error and fraud rate increased the overall cost of the fifth grant, the introduction of the FID is still estimated to be an overall cost-saving measure. This is due to the inclusion of a lower-rate grant (worth 30% of trading profits) and the reduction in take-up of the fifth grant. The exact saving from the FID is uncertain, due to other factors such as the changing economic situation, but could be up to £2.5 billion when comparing the drop-off in take-up between the fourth and fifth grants.

The RBT was introduced from the third SEISS grant onwards in order to improve targeting. This test required traders to confirm they believed they would suffer a reduction in their trading profits compared to what they would otherwise have expected in the absence of the pandemic. The RBT was devised to act as a ‘nudge’ for claimants intended to induce a behaviour change, and asked the customer to keep evidence to prove their reasonable belief that they would be impacted. Post-payment, it is difficult to establish the counterfactual to prove that the customer’s belief they would suffer a reduction in trading profits was not well grounded.

New insight from the Random Enquiry Programme has allowed HMRC to fill some evidence gaps and has shown that error and fraud from the RBT is larger than previously thought. Some customers were unable to provide evidence to support their claim. The error and fraud rate associated with the RBT for the fourth and fifth SEISS grants was estimated to be negligible in the interim evaluation, but has since been revised upwards to 2.2%, at a monetary cost of £613 million.

Further detail on the nature of the compliance risks can be found in the updated technical publication on error and fraud. To provide context to the SEISS estimates and to underline the comparative effectiveness of the compliance measures built into the scheme, they can be compared to the tax gap estimates. One important caveat with such a comparison is that the tax gap is estimated including the downstream impacts of compliance, meaning this estimate is for the error and fraud rate remaining after compliance activity has already occurred, whereas the estimates presented for the COVID-19 schemes do not include compliance recoveries. The most likely error and fraud figure for the whole life cycle of the SEISS scheme is 5.2%.

Compared to the Self Assessment tax gap, which covers a similar population to the SEISS, there is a tax gap of 12.4% in 2020 to 2021, and 11.2% in 2021 to 2022, so the SEISS is subject to a much lower rate of non-compliance than is seen elsewhere for this population. This appears even more favourable in comparison to the Self Assessment Business tax gap highlighted in the latest measuring tax gaps publication and the prior publication which stands at around 20%. This will cover a broadly similar population to the SEISS claimant population as it excluded large partnerships, who are unlikely to have been eligible for the SEISS based on the £50,000 trading profits cut-off.

2.3 Compliance approach

From the beginning, it was expected that the SEISS would be a target for fraud and that customers operating at pace and under pressure would make mistakes. Therefore, a range of measures to protect the scheme against organised crime, opportunistic fraud, and customer error were designed into the SEISS, which drew on analysis and intelligence of the likely significant risks.

The approach is outlined in detail in the SEISS interim evaluation and summarised below:

- promoting compliance – through education, good customer service, and providing easy ways for customers to make correct claims or correct and repay overclaims, including establishing an online portal

- preventing non-compliance – to limit incorrect or fraudulent claims being accepted, compliance controls were built into the scheme design and the claims process itself

- post-payment compliance – through additional powers given to HMRC as well as developing automatic correction methods and the creation of a taskforce specifically designed to recover overpaid COVID-19 grants

Since the start of the compliance activity into the SEISS and up to 31 March 2023, HMRC has recovered and prevented a loss of over £466 million with compliance activity still ongoing. Further details on the SEISS compliance outcomes can be found in HMRC’s Annual Report and Accounts for 2022 to 2023.

Additionally, repayments occur when customers entitled to a grant choose to repay it voluntarily, or when customers repay due to error or fraud without a prompt from HMRC. Up to end of March 2023, there has been a total of £51 million unprompted repayments and disclosures of SEISS grants.

Although the pre-payment controls and post-payment compliance action have succeeded in tackling error and fraud within the SEISS, there are 2 process decisions that could benefit from reconsideration for any future similar scheme that may help reduce the need for compliance interventions, albeit with some downsides.

Firstly, a decision was taken to exclude agents from making claims on behalf of their clients. This was in part to secure rapid delivery of the scheme, as building in claims for agents would take time, as well as to ensure HMRC could check that only one claim per grant was made by and paid out to each customer. Feedback from agents and representative bodies indicates that if they had been more directly involved in the claims process they could have ensured only those who were eligible claimed the grants and that receipt of the grants was recorded in the correct box on later tax returns.

Secondly, a decision was taken to invite claims from those who had indicated on their 2018 to 2019 tax return that they had ceased self-employment. The government knows that the self-employed population is volatile, with many pausing their trades, or ceasing one activity and commencing another a short time later. These traders would still have been eligible for the grant. At the outset the government was keen to ensure all those who might be eligible were invited to make a claim, at which point the claimant would then have to confirm whether they met the detailed scheme rules.

This decision led to 2 large scale post-payment compliance campaigns to check the trading position and recover grants that were paid to those who, despite confirming that they were still trading in the claim, had in fact not continued to trade. Some of this activity could have been avoided if this group had never been invited to claim, although a review process would have been needed to include cases where the customer had not been invited to claim but could show they had traded in the relevant tax year.

Chapter 3: The impact of the SEISS on incomes

3.1 Introduction

This chapter contributes towards answering the following evaluation questions:

- to what extent did the SEISS support claimants’ incomes?

- what impact did the eligibility criteria have on the scheme achieving its policy objectives?

- who was impacted by the SEISS and what can be learned from the relationships between their characteristics and the outcomes/impacts of the scheme?

- what impact did the SEISS have on claimants’ self-employment activity?

3.2 Overall assessment

The SEISS supported many self-employed individuals during the pandemic who would otherwise have experienced a decline in income. The impact of support varied across SEISS recipients, reflecting the diversity of the self-employed population and the variation in impact of the pandemic on their businesses. A lesson here is that improved data, including better understanding of sectors, and more timely information to understand the impact of the pandemic on businesses, could have helped reduce this range of outcomes.

This chapter assesses the impact of the SEISS across the entirety of the scheme using a range of analysis. There is a significant degree of uncertainty associated with some of these results, given that it is impossible to know what would have happened in the absence of the pandemic.

Taking the evidence together suggests 3 key conclusions:

-

The 2021 to 2022 tax year data shows the SEISS continued to ensure many self-employed individuals who would otherwise have been in significant financial difficultly were supported through the pandemic. On average, the SEISS appeared to protect profits of recipients that would have otherwise suffered falls in trading profits of 33% in 2020 to 2021 and 17% in 2021 to 2022. However, there were a range of outcomes for this population, with some self-employed people likely receiving more money than their pre-pandemic income, whereas others may have needed more support to maintain pre-pandemic income. The effect is particularly acute when looking at those sectors which were most affected by COVID-19 restrictions, for example arts, entertainment and recreation. Sectors least affected by restrictions experienced significant gains compared to their pre-pandemic income when taking into account the value of SEISS grants, although these were tempered by better targeting over time.

-

The SEISS eligibility criteria of having no more than £50,000 of trading profits and at least half of income from self-employment were set to support those people who were likely to be most impacted by a decline in their self-employed income. On average, self-employed individuals who were assessed as ineligible for the SEISS and those assessed as eligible but did not claim the SEISS did not fare worse, with significant improvements in average profits of 21% and 33% respectively in 2021 to 2022 compared to pre-pandemic. This is compared to eligible claimants who experienced a 17% decrease in average trading profits without the SEISS grant, and a 9% increase in average trading profits including the SEISS grant. The need to get support to people quickly combined with the lack of real-time information for the self-employed population meant it was not possible for early grants to have an overly complex design. However, the targeting of the SEISS was improved over time with the introduction of additional needs-based criteria to target the most generous support at those experiencing a slower recovery.

-

Although evidence is mixed, there may have been a localised behavioural change by self-employed people on higher incomes as a result of receiving SEISS grants, whereby receiving the grants resulted in reduced income, possibly due to lower work effort, known as an income effect in economic theory. This effect appears to have increased for the fourth and fifth grants. It is worth noting that for any significant income replacement grant, it would be expected to see some behavioural response. However, this behavioural effect can only be credibly evidenced for those with higher incomes. It is expected that the income effect would be less likely for individuals with lower incomes, and those who received smaller grants, but this cannot be tested by this analysis.

3.3 Trading profits analysis

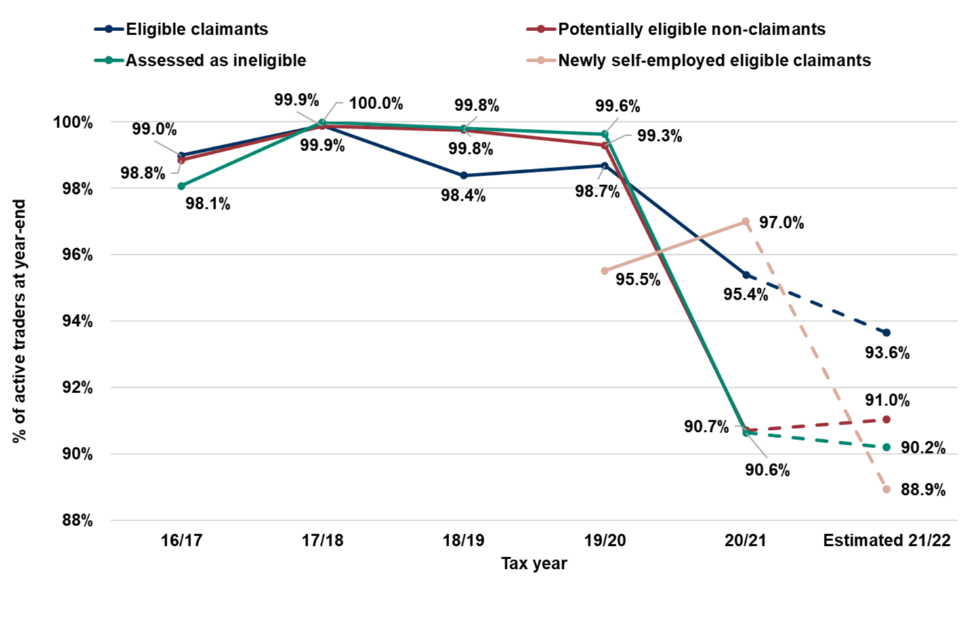

If the SEISS was successful at achieving its primary aim of supporting self-employed incomes during the pandemic, trading profits in 2020 to 2021 and 2021 to 2022 might be expected to remain broadly in line with the historic trends. Before assessing the causal impact of the SEISS, this chapter considers the average trading profits of the self-employed population during the pandemic (2020 to 2021 and 2021 to 2022), compared to pre-pandemic, to examine the difference in outcomes between SEISS recipients and non-recipients. Outcomes are compared for several key groups related to their SEISS eligibility and use: ‘eligible claimants’, ‘potentially eligible non-claimants’, ‘assessed as ineligible’ and ‘newly self-employed eligible claimants’ (who were ineligible in 2020 to 2021 but eligible in 2021 to 2022).

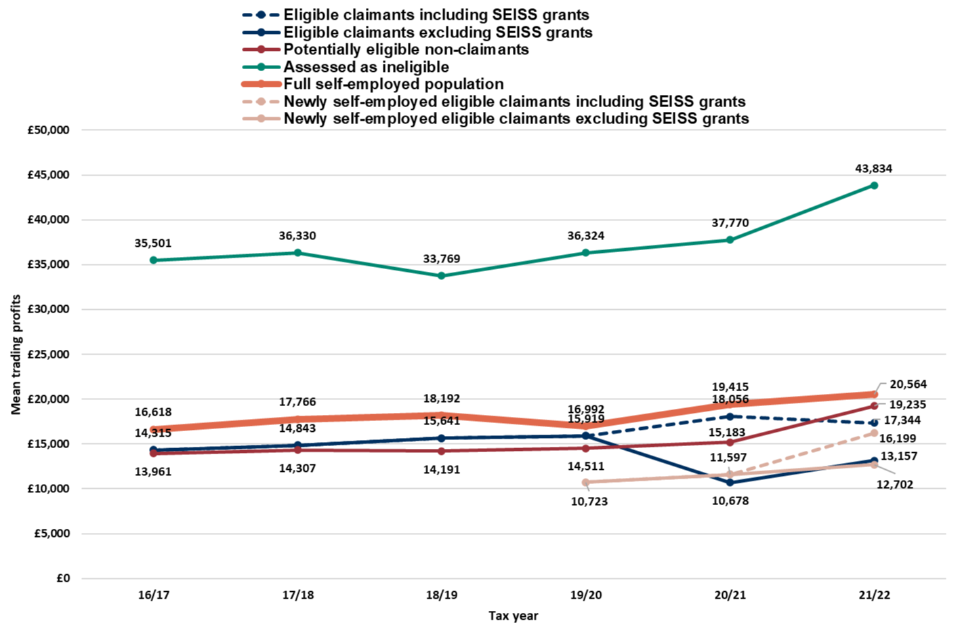

Figure 3.1: Mean trading profits based on SEISS claimant status

Source: HMRC SEISS data matched to Self Assessment taxpayer information

Sample size: Approximately 4.2 million individuals

Notes: Only includes individuals if they filed at least one self-employed page on a Self Assessment return for 2019 to 2020 and 2020 to 2021 for the first 3 SEISS grants and 2021 to 2022 for the fourth and fifth SEISS grants, and some outliers are removed

Table 3.1 Mean trading profits based on SEISS claimant status

| Tax year | Eligible claimants including SEISS grant (£) | Eligible claimants excluding SEISS grant (£) | Potentially eligible non-claimants (£) | Assessed as ineligible (£) | Newly self-employed eligible claimants including SEISS grant (£) | Newly self-employed eligible claimants excluding SEISS grant (£) | Full self-employed population (£) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16/17 | 14,315 | 14,315 | 13,961 | 35,501 | - | - | 16,618 |

| 17/18 | 14,843 | 14,843 | 14,307 | 36,330 | - | - | 17,766 |

| 18/19 | 15,641 | 15,641 | 14,191 | 33,769 | - | - | 18,192 |

| 19/20 | 15,919 | 15,919 | 14,511 | 36,324 | 10,723 | 10,723 | 16,992 |

| 20/21 | 18,056 | 10,678 | 15,183 | 37,770 | 11,597 | 11,597 | 19,415 |

| 21/22 | 17,344 | 13,157 | 19,235 | 43,834 | 16,199 | 12,702 | 20,564 |

Figure 3.1 shows that, on average, SEISS grants more than offset the decline in trading profits experienced by self-employed SEISS claimants in 2020 to 2021. This suggests that, had the SEISS not existed, claimants may have experienced a potentially large reduction in income, particularly in 2020 to 2021. However, there was significant variation in outcomes within this population.

In 2021 to 2022, the gap between average trading profits including the SEISS grants and excluding the SEISS grants reduced compared to 2020 to 2021. This could be explained by a combination of increased targeting, with the introduction of the FID for the fifth SEISS grant and the improved economic outlook during 2021. This is evidenced by lower take up rates for the fourth and fifth grants (58% and 38% respectively) indicating individuals may have started to experience an increase in trading profits as the economy opened up.

Trading profits increased by 9% to just over £17,000 in 2021 to 2022 compared to pre-pandemic profits in 2019 to 2020 (when including SEISS grants). This was slightly down on trading profits of just over £18,000 in 2020 to 2021, likely explained by improved targeting via the FID and lower grants for more strongly performing businesses. 59% of individuals saw an increase in profits in 2021 to 2022 compared to pre-pandemic profits in 2019 to 2020.

Figure 3.1 also suggests that newly self-employed individuals would have experienced a small level of year-on-year growth in average trading profits without the SEISS. Compared to historical trends of newly self-employed individuals among whom initial trading profits are generally lower, newer self-employed claimants appear to have made a stronger start to their business in 2019 to 2020 and were more able to continue trading in 2020 to 2021 before claiming SEISS grants in 2021 to 2022.

This suggests these businesses were more able to adapt to the shock to the economy. Over half (53%) of newly self-employed eligible claimants reported increased trading profits in both 2020 to 2021 and in 2021 to 2022, when the SEISS grant is excluded. When the SEISS grant is included in 2021 to 2022 (the year this group became eligible), over two-thirds (71%) experienced an increase in annual trading profits.

In comparison, those who were potentially eligible for the SEISS but chose not to claim experienced on average a strong recovery in annual trading profits in 2021 to 2022 (27%, up from 3% during 2020 to 2021). This suggests that this group generally did not need the SEISS because their businesses were better able to generate profits during the pandemic.

Those who were assessed as ineligible for the SEISS saw large increases in average trading profits in 2021 to 2022. This jump is mainly driven by those individuals who were assessed as ineligible due to having trading profits greater than £50,000 and supports the theory that businesses with higher trading profits were more able to adapt to the pandemic.

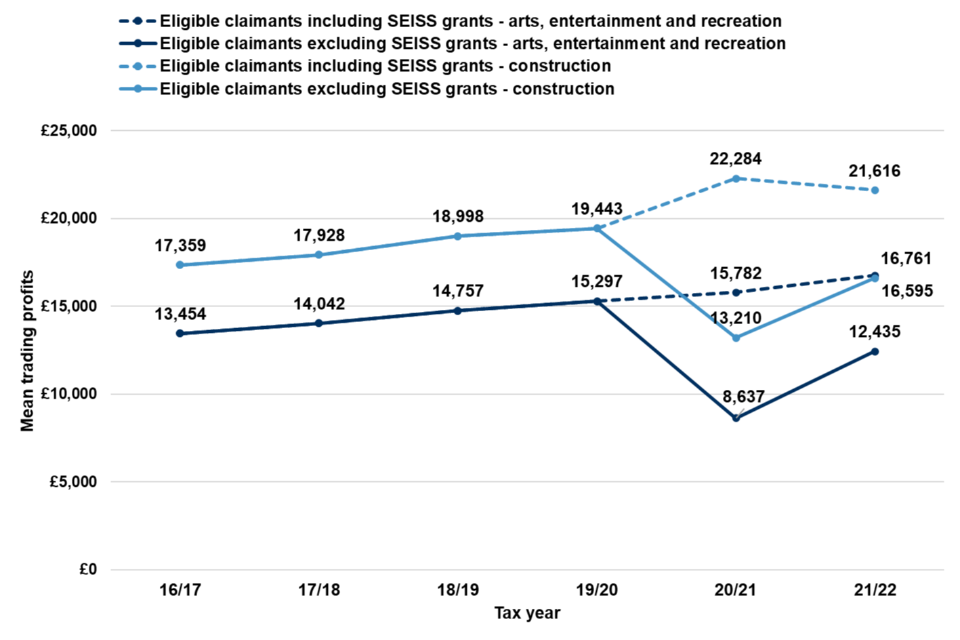

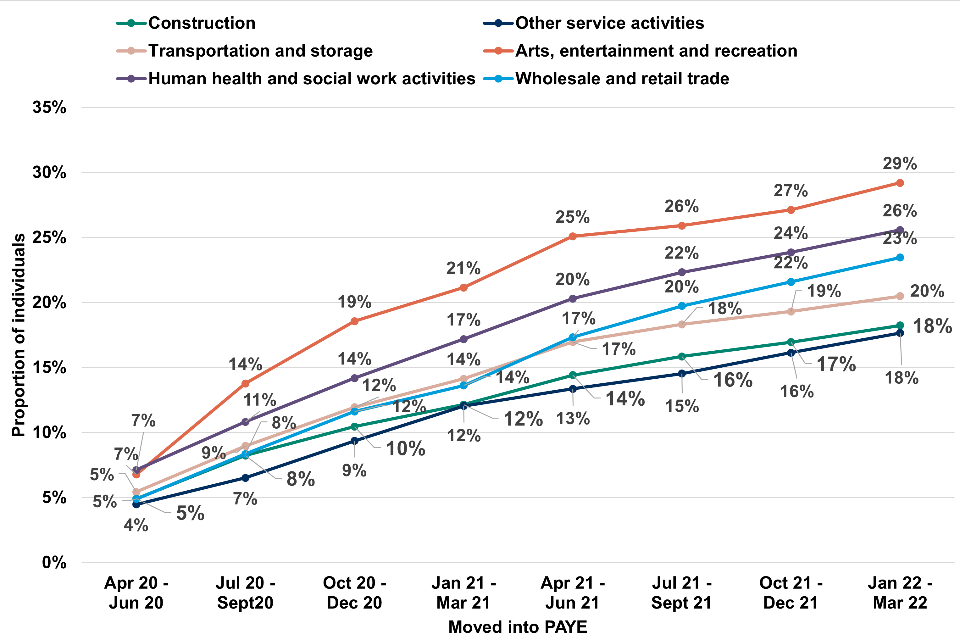

However, there was a significant range in outcomes, as sectoral analysis illustrates. Figure 3.2 compares the difference that the SEISS made for one of the most affected sectors (arts, entertainment and recreation) with one of the less affected sectors (construction). The SEISS topped up average profits for arts, entertainment and recreation to around pre-pandemic levels, whereas in construction it provided a significant surplus in 2020 to 2021.

This was less pronounced in 2021 to 2022, further evidence of the improved targeting for the last 2 grants. Construction was the sector with the highest number of SEISS claimants and covers a very broad range of activities as well as a dependency on other sectors (to avoid supply chain issues), which likely means effects from the pandemic within this sector also varied. The variation in effects by sector shows that the SEISS helped many individuals who were particularly affected by loss of income during the pandemic.

Figure 3.2: Mean trading profits for SEISS eligible claimants in the arts, entertainment and recreation and the construction sectors

Source: HMRC SEISS data matched to Self Assessment taxpayer information and the Standard Industry Classification produced by the Office for National Statistics (ONS)

Sample size: Approximately 1.2 million individuals

Notes: Only includes individuals if they filed at least one self-employed page on a Self Assessment return for 2019 to 2020 and 2020 to 2021 for the first 3 SEISS grants and 2021 to 2022 for the fourth and fifth SEISS grants, and some outliers are removed

Table 3.2 Mean trading profits for SEISS eligible claimants in the arts, entertainment and recreation and the construction sectors

| Tax year | Eligible claimants including SEISS grant - arts, entertainment and recreation (£) | Eligible claimants excluding SEISS grant - arts, entertainment and recreation (£) | Eligible claimants including SEISS grant - construction (£) | Eligible claimants excluding SEISS grant - construction (£) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16/17 | 13,454 | 13,454 | 17,359 | 17,359 |

| 17/18 | 14,042 | 14,042 | 17,928 | 17,928 |

| 18/19 | 14,757 | 14,757 | 18,998 | 18,998 |

| 19/20 | 15,297 | 15,297 | 19,443 | 19,443 |

| 20/21 | 15,782 | 8,637 | 22,284 | 13,210 |

| 21/22 | 16,761 | 12,435 | 21,616 | 16,595 |

3.4 Income counterfactual analysis

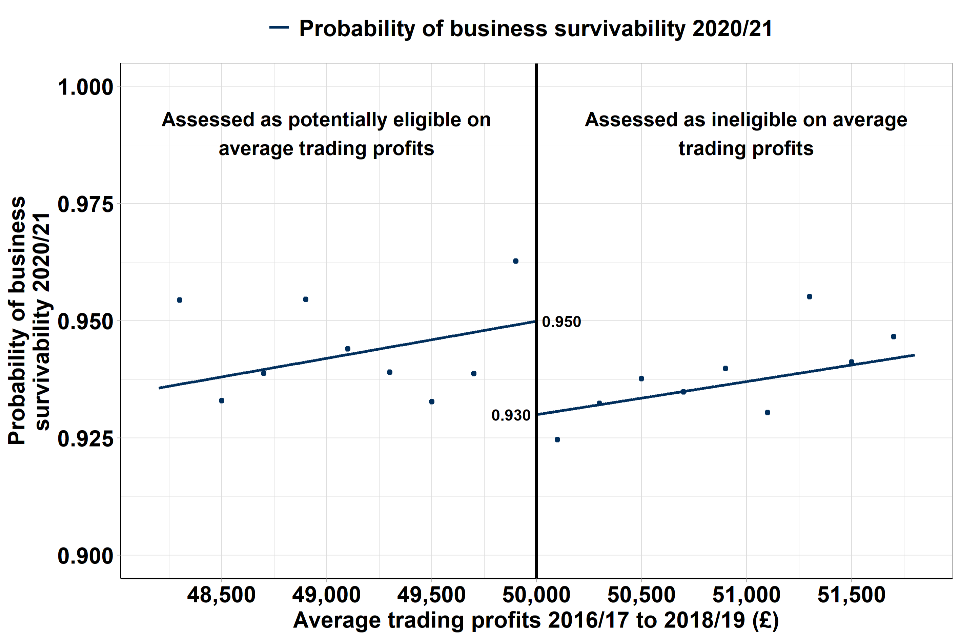

Another potential explanation for the differing outcomes in figure 3.1 (that trading profits for claimants, excluding the SEISS, are lower than the assessed as ineligible group) is that there may have been an ‘income effect’; that is receiving the SEISS may have led to some claimants reducing the amount of work they undertook. An income effect is consistent with economic theory and therefore might be expected when a grant replaces earned income. However, it is difficult to test for as there is no way to know for certain how individuals would have behaved had the SEISS not been made available. A counterfactual assessment attempts to estimate what would have happened in the absence of the SEISS. An approach called ‘Fuzzy Regression Discontinuity Design (RDD)’ is used to test how claiming the SEISS affected behaviour, in order to consider the impact of the scheme.

RDD is a quasi-experimental evaluation tool that can help estimate the causal impact of an intervention (such as the SEISS) that was offered to a group of people who met certain eligibility criteria, by comparing outcomes either side of those criteria thresholds. These criteria will create a discontinuity (a change in the trend) in outcomes for individuals on either side of the eligibility thresholds. Quasi-experimental means that statistical techniques are used to estimate the impact of the intervention, given that the grants were not randomly allocated. Randomisation would have ensured no systematic differences between the treatment (assessed as potentially eligible for the SEISS) and counterfactual (assessed as ineligible) populations meaning any observed differences in observed outcomes could be directly attributed to the SEISS. However, randomisation would not be ethical in this case.

This analysis compares trading profits and total income in 2021 to 2022 for individuals immediately above and below the cut-off points for the fourth and fifth SEISS grants of £50,000 average trading profits, and average trading profits being 50% of total income. The interim evaluation published in October 2022 compared trading profits in 2020 to 2021 for individuals immediately above and below the cut-off points for eligibility for the first 3 SEISS grants. It reported that income from the first 3 SEISS grants may have allowed some individuals to slightly reduce hours worked (referred to as an ‘income effect’).

In this analysis a discontinuity occurs at the eligibility threshold because individuals with less than £50,000 average trading profits (calculated using whichever years individuals were actively trading between 2016 to 2017 and 2019 to 2020) often chose to claim the SEISS, whereas those above this threshold were assessed as ineligible. The fuzzy design allows for voluntary participation as not every individual with average trading profits below £50,000 claimed the SEISS.

The analysis looks at trading profits and total income, both including and excluding SEISS grants, as outcome variables. Whereas trading profits are the total net profits of individuals’ self-employed businesses, total income includes other sources of income the individual may have, such as employment, dividends, pensions or property.

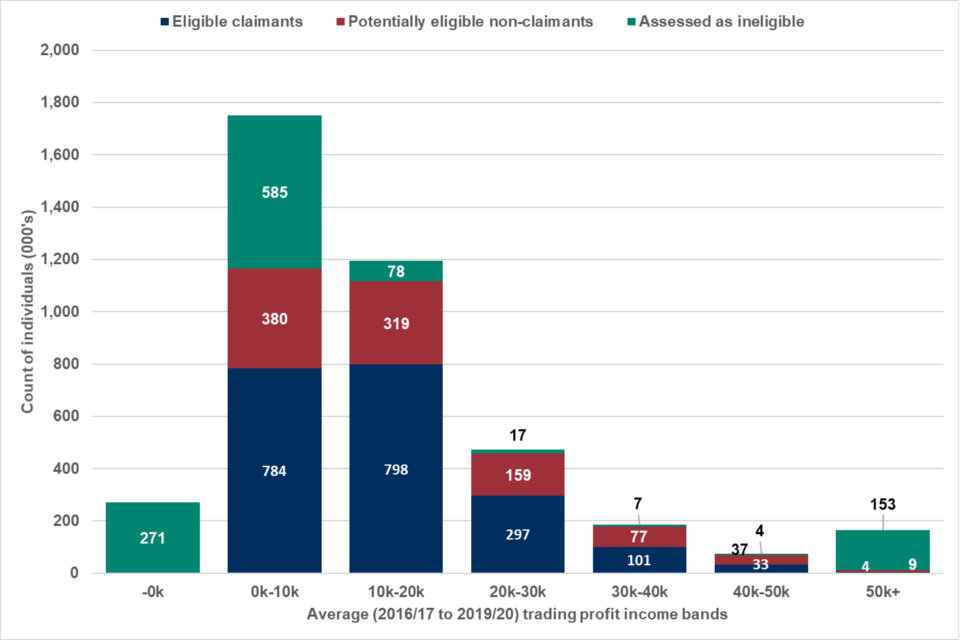

Figure 3.3: Income bands based on average trading profits between 2016 to 2017 and 2019 to 2020 by SEISS eligibility status

Source: HMRC SEISS data matched to Self Assessment taxpayer information

Sample size: Approximately 4.2 million individuals

Notes: Only includes individuals if they filed at least one self-employed page on a Self Assessment return for 2019 to 2020 and 2020 to 2021 for the first 3 SEISS grants and 2021 to 2022 for the fourth and fifth SEISS grants, and some outliers are removed

Table 3.3 Income bands based on average trading profits between 2016 to 2017 and 2019 to 2020 by SEISS eligibility status

| Average (2016/17 to 2019/20) trading profit income bands | Eligible claimants (000’s) | Potentially eligible non-claimants (000’s) | Assessed as ineligible (000’s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| -0k | 0 | 0 | 271 |

| 0k-10k | 784 | 38 | 585 |

| 10k-20k | 798 | 319 | 78 |

| 20k-30k | 297 | 159 | 17 |

| 30k-40k | 101 | 77 | 7 |

| 40k-50k | 33 | 37 | 4 |

| 50k+ | 4 | 9 | 153 |

Figure 3.3 shows the majority of individuals assessed as potentially eligible for the SEISS had lower average trading profits of between £0 and £20,000 which is consistent with median self-employment income being much lower (around £10,000 in 2021 to 2022) compared to the individuals assessed in the RDD around the £50,000 threshold. There are a small number of individuals assessed as potentially eligible with average trading profits over the £50,000 threshold. This is because these individuals would have been assessed as potentially eligible on their single-year 2019 to 2020 trading profits but were assessed as ineligible based on their average trading profits.

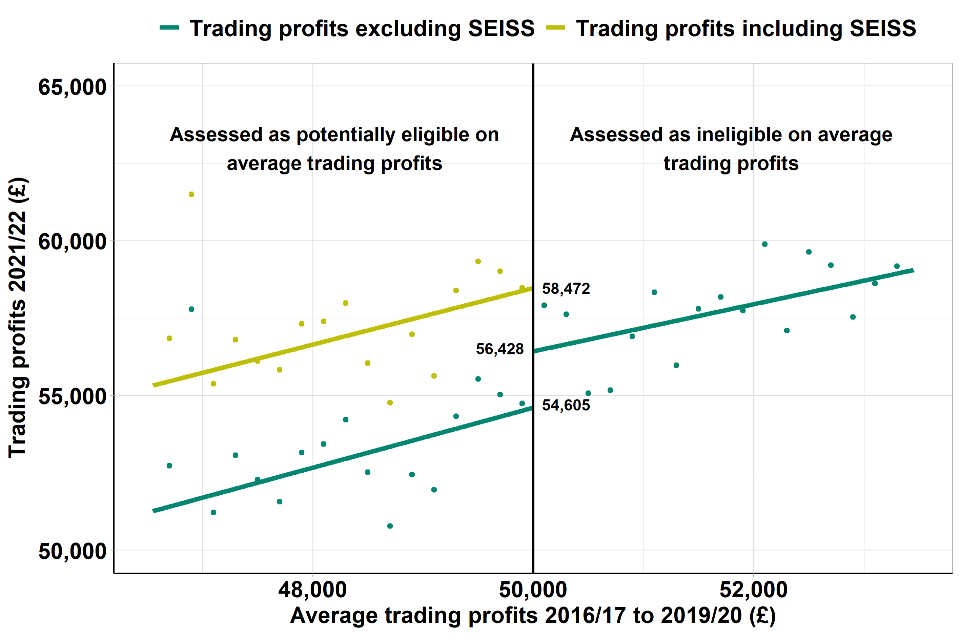

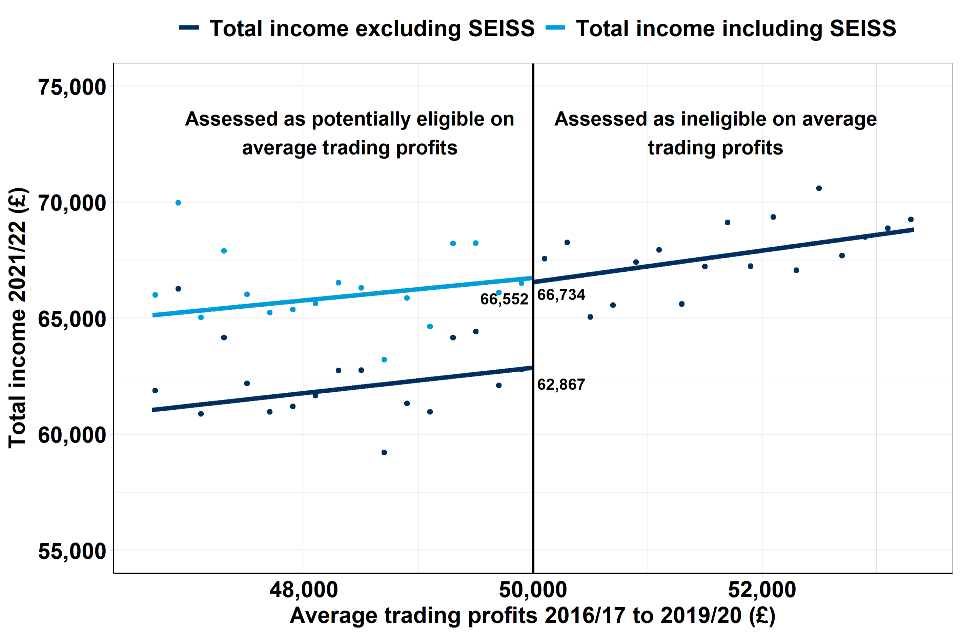

Figures 3.4a and 3.4b compare the trading profits and total income of those just below and above the £50,000 trading profits eligibility criteria. Figure 3.4a shows trading profits in 2021 to 2022 as the outcome variable, both including and excluding SEISS grants, and figure 3.4b shows the same but for total incomes. Self-employed people who sit very marginally above or below the eligibility threshold ought to have had very similar trading profits and/or incomes when excluding SEISS grants and have other similar characteristics.

Therefore, any difference in trading profits and/or incomes is more likely to be the impact on behaviour that can be attributed to receiving SEISS grants. More details on this analysis can be found in the counterfactual technical note.

Figure 3.4a: RDD output for average trading profits (between 2016 to 2017 and 2019 to 2020) against trading profits in 2021 to 2022

Source: HMRC SEISS data matched to Self Assessment taxpayer information

Sample size: Approximately 17,000 individuals

Notes: Only includes individuals if they filed at least one self-employed page on a Self Assessment return for 2019 to 2020, 2020 to 2021 and 2021 to 2022, and some outliers are removed. All individuals included were ineligible based on their 2019 to 2020 Self Assessment return alone.

Table 3.4a RDD output for average trading profits (between 2016 to 2017 and 2019 to 2020) against trading profits in 2021 to 2022

| Outcome variable | 2021 to 2022 trading profits with average trading profits under £50,000 - A | 2021 to 2022 trading profits with average trading profits over £50,000 - B | Difference A-B = C | Difference in probability of claiming SEISS either side of £50,000 discontinuity - D | Estimate = C/D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21/22 trading profits including SEISS (£) | 58,472 | 56,428 | 2,044 | 0.380 | 5,379 |

| 21/22 trading profits excluding SEISS (£) | 54,605 | 56,428 | -1,823 | 0.380 | -4,797 |

Figure 3.4b: RDD output for average trading profits (between 2016 to 2017 and 2019 to 2020) against total income in 2021 to 2022

Table 3.4b RDD output for average trading profits (of years 2016 to 2019) against total income in 2021 to 2022

| Outcome variable | 2021 to 2022 total income with average trading profits under £50,000 - A | 2021 to 2022 total income with average trading profits over £50,000 - B | Difference A-B = C | Difference in probability of claiming SEISS either side of £50,000 discontinuity - D | Estimate = C/D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21/22 total income including SEISS (£) | 66,552 | 66,734 | -182 | 0.380 | -479 |

| 21/22 total income excluding SEISS (£) | 62,867 | 66,734 | -3,867 | 0.380 | -10,176 |

The analysis shows that, close to both thresholds, SEISS claimants in the potentially eligible group had on average lower non-SEISS trading profits and incomes than the assessed as ineligible group.

When comparing the groups that fall either side of the £50,000 threshold (figure 3.4a), the gap between the dark green lines at the threshold for trading profits excluding SEISS grants (£56,428 compared to £54,605) is statistically insignificant. Figure 3.4a also shows that for individuals with average trading profits close to the threshold of £50,000, their 2021 to 2022 trading profits are on average around £55,000. In the interim evaluation it was shown that individuals close to the £50,000 average trading profits threshold had 2020 to 2021 trading profits of around £40,000. This provides further evidence that businesses started recovering to pre-pandemic levels of trading profits in 2021 to 2022.

However, there is a statistically significant difference between the darker blue lines (figure 3.4b) at the threshold for total income excluding SEISS grants (£66,734 compared to £62,867). Comparing the average values for trading profits and total income at the threshold suggests the majority of total income for individuals close to the threshold is sourced from trading profits. Furthermore, deeper analysis into the sources of other non-trading income has not shown any significant differences between individuals assessed as potentially eligible and those assessed as ineligible. This suggests self-employment activity is driving much of the observed difference, however this is not translated into a statistically significant difference when isolating trading profits from total income.

Further analysis has indicated a difference in outcomes between self-employed individuals who are sole traders and those who are members of a partnership. Limiting the population to those with sole trader income has shown those assessed as potentially eligible based on average trading profits experienced trading profits excluding the SEISS that were on average around £2,000 lower in 2021 to 2022 than those assessed as ineligible, which is equivalent to around £8,000 per SEISS recipient. This difference is statistically significant at the 10% level which suggests that income from the SEISS grants may have slightly disincentivised economic activity (an ‘income effect’) for sole traders, who have greater autonomy over their business, but there is less evidence of an impact for self-employed individuals who are members of a partnership.

Overall, this provides some limited evidence that receiving SEISS grants was associated with lower incomes (excluding SEISS grants). This could suggest that receipt of SEISS grants may have led some claimants to reduce the amount of work they undertook, or to reduce their involvement in other economic activities. This is known as an ‘income effect’. The possibility of an income effect is consistent with economic theory of individuals’ working decisions where an unearned grant is received.

The size of this estimated effect in 2021 to 2022 is almost £4,000 near the £50,000 average trading profits threshold, which is equivalent to almost £10,000 per SEISS recipient of the last 2 SEISS grants. The population assessed in this analysis was eligible for the maximum value of the fourth SEISS grant capped at £7,500, and for the fifth SEISS grant either a maximum of £7,500 for those with a turnover reduction of 30% or more, or a maximum of £2,850 for those with a turnover reduction of less than 30%. This means this group will have been eligible to claim between £10,350 and £15,000 in SEISS grants. It is notable that this is a larger income effect than was found for the first 3 grants of around £5,000 per recipient. This may reflect the SEISS grants being paid out during the first half of the year, but trading profits are reported for the whole year and there was a strong economic recovery experienced during the second half of the year in 2021 to 2022 which may have contributed to improved trading income.

However, it is important to note that the extent of this income effect across the wider self-employed population is uncertain because the evidence is limited to total incomes either side of the £50,000 eligibility criteria, with no evidence of an income effect for trading profits unless the population is limited to sole traders only.

Furthermore, this analysis uses a specific sub-section of the SEISS population and whilst the demographics of this group are broadly representative of the self-employed population this finding is only valid around the £50,000 threshold and cannot be generalised to the entire population of SEISS recipients. Indeed, it is possible that behaviour for individuals close to the threshold could be due to a ‘substitution effect’ whereby individuals chose to work less in order to keep their trading profits below the eligibility cut-off in anticipation of eligibility for any continued or future support.

Therefore, this result is only directly valid for those individuals near the eligibility threshold (less than 1% of the total self-employed population) and may not be generalisable to the over 5 million individuals who were assessed for the SEISS, who may have different characteristics. It is expected that the income effect would be smaller for individuals with lower incomes, and those who received smaller values from the SEISS, but this cannot be tested by this analysis.

Chapter 4: Impact on businesses and the economy

4.1 Introduction

This chapter contributes towards answering the following evaluation questions:

- what contribution did the SEISS make to the outcomes and impacts identified?

- what impact did the eligibility criteria have on the scheme achieving its policy objectives?

- who was impacted by the SEISS and what can be learned from the relationships between characteristics and outcomes/impacts of the scheme?

- what impact did the SEISS have on claimants’ self-employment activity?

4.2 Overall assessment

SEISS was primarily intended to be an income support scheme, and the previous chapter assessed in detail the impact of the scheme in this respect. However, this chapter assesses the impact beyond this, especially on self-employed businesses and the macroeconomy. Overall, there are 3 key conclusions:

- In the short term, covering the first year of the pandemic, the scheme had a positive effect on business survivability, with claimants more likely to continue trading than potentially eligible non-claimants, or those assessed as ineligible

- The longer-term effect during the second year of the pandemic is less clear. Due to the lag in Self Assessment data it is not possible to fully assess the longer term impact of the SEISS on business survivability

- In addition to the effects on business survivability, there were some macroeconomic benefits from the scheme. The income provided to individuals from the SEISS had the impact of supporting demand during the pandemic and reducing the size of the negative shock to the economy, while helping businesses continue trading prevented periods of unemployment or inactivity

4.3 Business survivability analysis

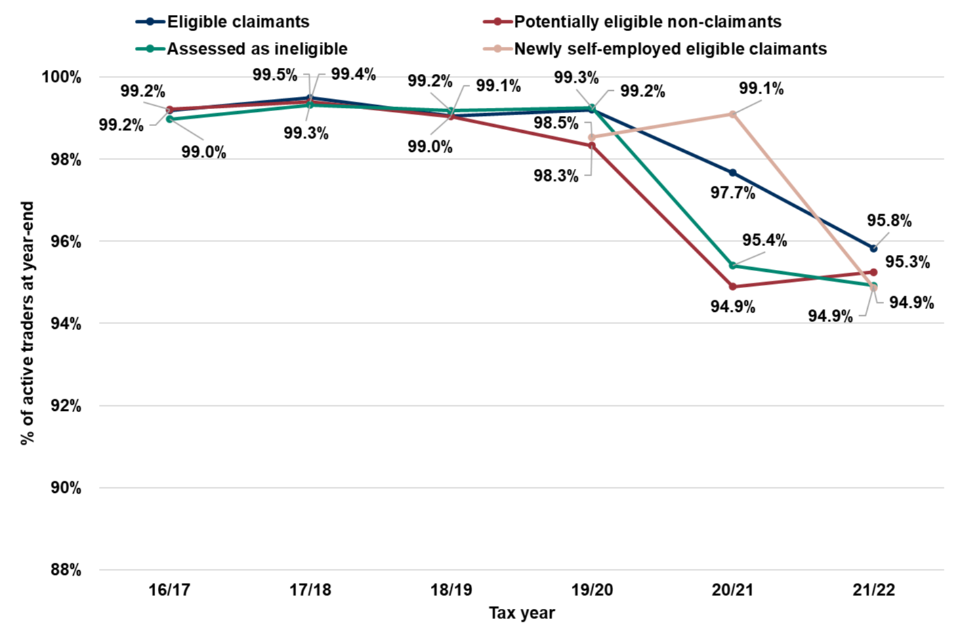

Analysis of business survivability shows that SEISS claimants were more likely to continue trading than potentially eligible non-claimants or those assessed as ineligible for the scheme. This suggests the SEISS may have had a positive effect in helping businesses to survive during the pandemic.

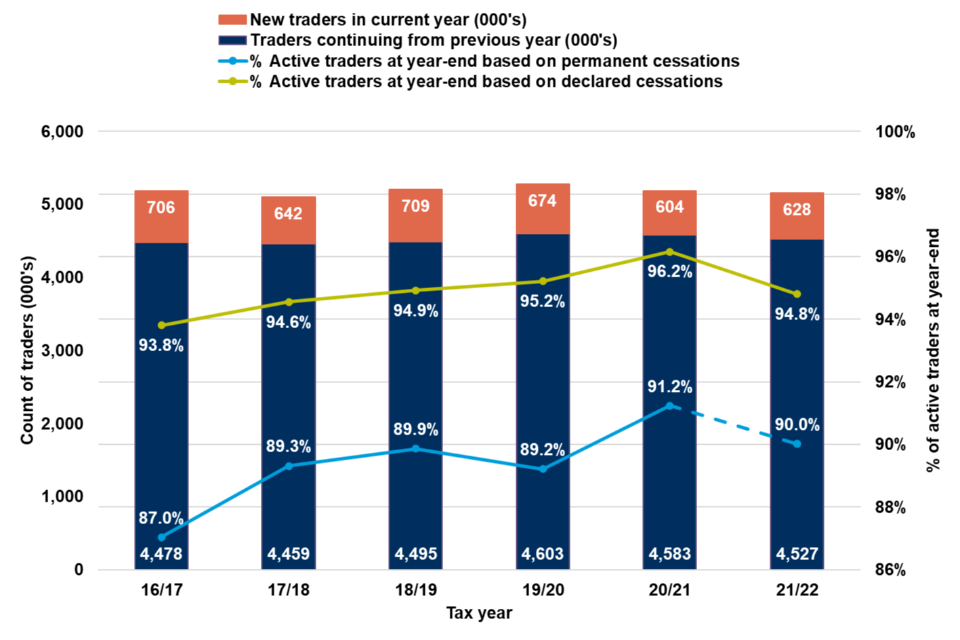

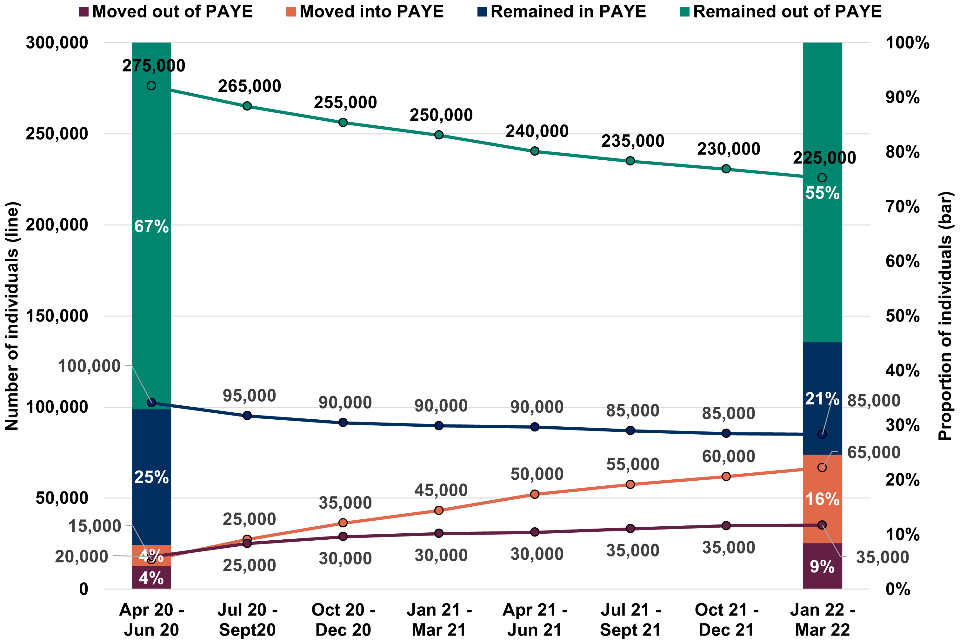

Figure 4.1: Churn of full self-employed population

Source: HMRC SEISS data matched to Self Assessment taxpayer information

Sample size: Approximately 5.3 million individuals

Notes: Includes the full self-employed population from 2016 to 2017 and 2021 to 2022 who are new traders in current year and traders continuing from previous year

Table 4.1: Churn of full self-employed population

| Tax year | Count of new traders in current year (000’s) | Traders continuing from previous year (000’s) | Active traders at year-end based on permanent cessations (%) | Active traders at year-end based on declared cessations (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16/17 | 706 | 4,478 | 87.0 | 93.8 |

| 17/18 | 642 | 4,459 | 89.3 | 94.6 |

| 18/19 | 709 | 4,495 | 89.9 | 94.9 |

| 19/20 | 674 | 4,603 | 89.2 | 95.2 |

| 20/21 | 604 | 4,583 | 91.2 | 96.2 |

| 21/22 | 628 | 4,527 | 90.0 | 94.8 |

Analysis of the full self-employed population (at the individual level) shows an increase in business survivability during the first year of the pandemic (91.2% of traders in 2020 to 2021 remained active at year-end based on permanent cessations or 96.2% based on declared cessations). However, it should be noted that the full self-employed population includes individuals that were not assessed for the SEISS and individuals that ceased trading before the pandemic. Individuals not assessed for the SEISS includes new businesses that commenced trading during or after 2019 to 2020, which comprise around 15% of the total population each year. As such, this analysis includes traders who were more able to adapt to the effects of the pandemic.

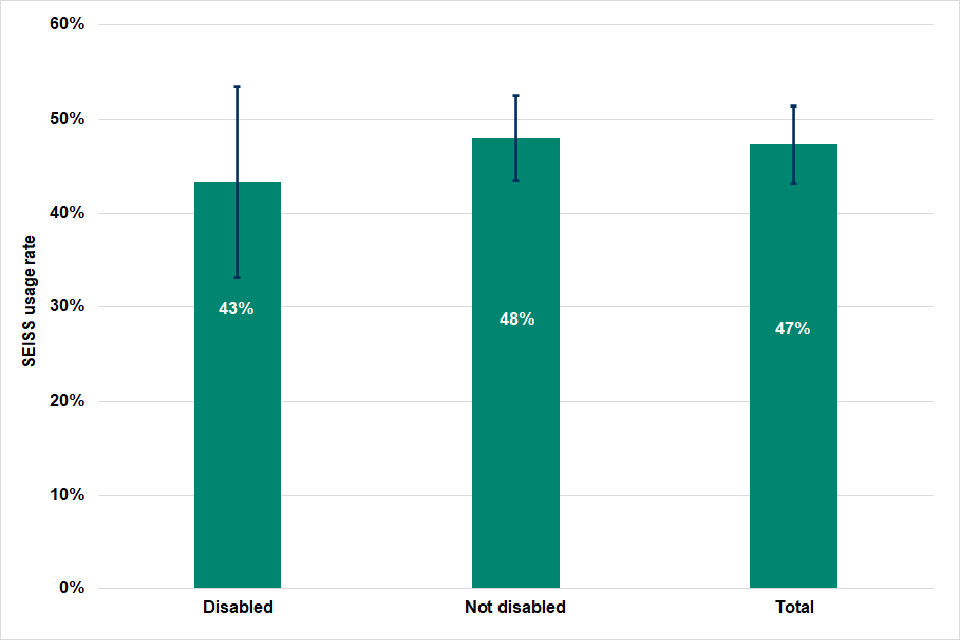

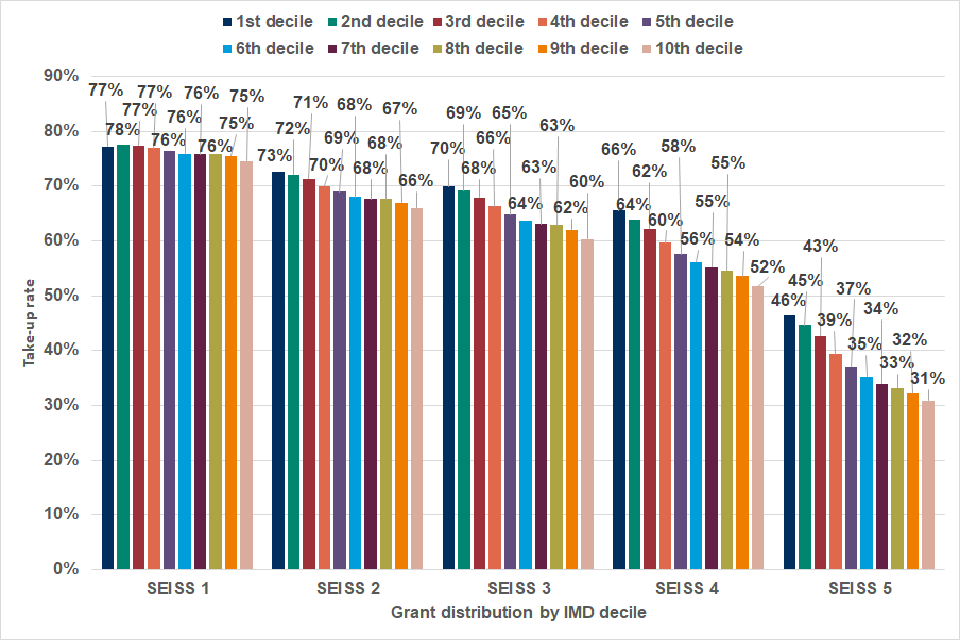

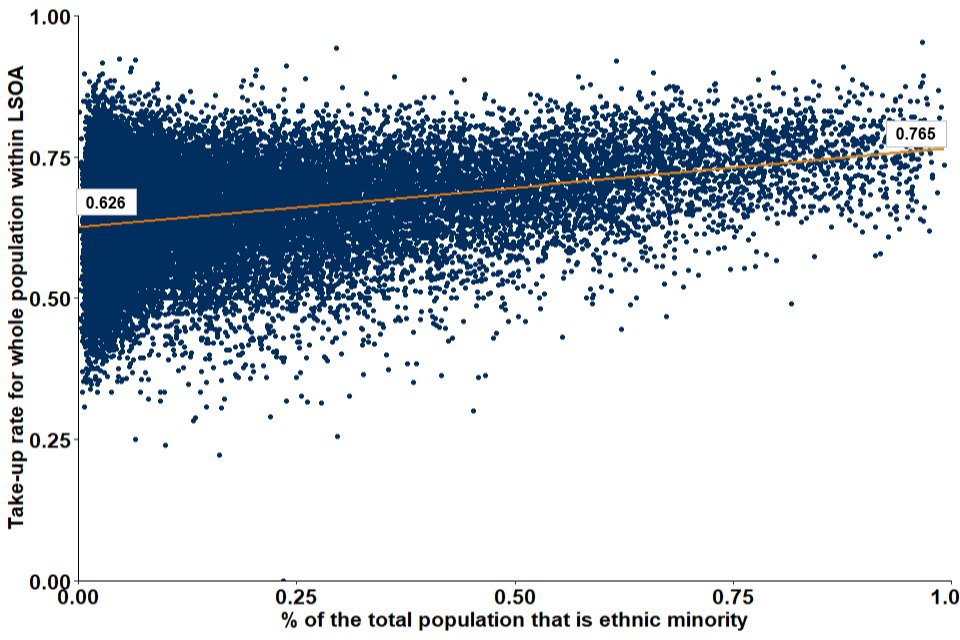

Analysis in the SEISS interim evaluation showed early signs that the SEISS was helping businesses to continue trading. It should be noted that this analysis is limited to the subset of the self-employed population who were assessed for eligibility for the SEISS. Rolling forward this analysis to 2021 to 2022 tax year finds a reduced impact from the SEISS in terms of longer-term business survivability. However, this analysis should be treated with caution as it is limited to cessation dates as declared on Self Assessment returns. It is not possible to determine whether these represent permanent or temporary closures, or whether an individual has started an alternative business in the next tax year, or has not declared a cessation date. Within the 2021 to 2022 tax year, 27% of eligible claimants with declared business cessations had newly commenced employment within the tax year, compared to 29% of potentially eligible non-claimants and 12% of the assessed as ineligible population.