Country policy and information note: security situation, Syria, July 2025 (accessible)

Updated 6 January 2026

Version 2.0, July 2025

Executive summary

On 8 December 2024, the regime of Bashar Al-Assad fell, bringing an end to over 50 years of Al-Assad family rule. An Islamist rebel group called Hayat Tahrir Al-Sham (HTS) led by Ahmad Al-Sharaa, commenced the 11-day offensive which culminated in the toppling of Al-Assad. Ahmad Al-Sharaa is now the de facto leader of Syria, and figures affiliated with HTS occupy the major positions in the new government.

A breakdown in law and order or uncertain security situations do not in themselves give rise to a well-founded fear of persecution for a Refugee Convention reason.

There are not substantial grounds for believing there is a real risk of serious harm in Syria because of a serious and individual threat to a civilian’s life or person by reason of indiscriminate violence in a situation of international or internal armed conflict, as defined in paragraphs 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules. The onus is on the person to demonstrate otherwise.

Where a claim is refused, it is unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

All cases must be considered on their individual facts, with the onus on the person to demonstrate they face persecution or serious harm.

Assessment

Section updated: 7 June 2025

About the assessment

This section considers the evidence relevant to this note – that is the country information, refugee/human rights laws and policies, and applicable caselaw – and provides an assessment of whether, in general:

- the security situation is such that there are substantial grounds for believing there is a real risk of serious harm because there exists a serious and individual threat to a civilian’s life or person by reason of indiscriminate violence in a situation of international or internal armed conflict as within paragraphs 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules

- the state (or quasi state bodies) can provide effective protection

- internal relocation is possible to avoid persecution/serious harm

- a claim, if refused, is likely or not to be certified as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

Decision makers must, however, consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts.

Sources cited in the country information may refer interchangeably to Hayat Tahrir Al-Sham (HTS), or the interim or de facto government or authorities. Within this assessment, we use the (new) Syrian government and, since 8 December 2024 they are considered the controlling party of the state or a substantial part of the territory of the State (for the purposes of Article 1(A)(2) of the Refugee Convention).

1. Material facts, credibility and other checks/referrals

1.1 Credibility

1.1.1 For information on assessing credibility, see the instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

1.1.2 Decision makers must also check if there has been a previous application for a UK visa or another form of leave. Asylum applications matched to visas should be investigated prior to the asylum interview (see the Asylum Instruction on Visa Matches, Asylum Claims from UK Visa Applicants).

1.1.3 Decision makers must also consider making an international biometric data-sharing check, when such a check has not already been undertaken (see Biometric data-sharing process (Migration 5 biometric data-sharing process)).

1.1.4 In cases where there are doubts surrounding a person’s claimed place of origin, decision makers should also consider language analysis testing, where available (see the Asylum Instruction on Language Analysis).

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information in this section has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

1.2 Exclusion

1.2.1 Decision makers must consider whether there are serious reasons to apply one (or more) of the exclusion clauses. Each case must be considered on its individual facts.

1.2.2 Multiple armed groups have operated, or still operate, in Syria. This includes (but is not limited to) the Assad regime’s military and security forces, and groups involved in Assad’s fall and the post-Assad era. Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) are proscribed terrorist organisations in the UK. For reports of serious human rights abuses committed by parties to the conflict see Violence against civilians and relevant claim-specific Syria CPINs.

1.2.3 If the person is excluded from the Refugee Convention, they will also be excluded from a grant of humanitarian protection (which has a wider range of exclusions than refugee status).

1.2.4 For guidance on exclusion and restricted leave, see the Asylum Instruction on Exclusion under Articles 1F and 33(2) of the Refugee Convention, Humanitarian Protection and the instruction on Restricted Leave.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information in this section has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

2. Convention reason(s)

2.1.1 A breakdown in law and order or uncertain security situations do not in themselves give rise to a well-founded fear of persecution for a Refugee Convention reason.

2.1.2 In the absence of a link to one of the 5 Refugee Convention grounds necessary to be recognised as a refugee, the question to address is whether the person will face a real risk of serious harm in order to qualify for Humanitarian Protection (HP).

2.1.3 However, before considering whether a person requires protection because of the general security situation, decision makers must consider if the person faces persecution for a Refugee Convention reason. Where the person qualifies for protection under the Refugee Convention, decision makers do not need to consider if there are substantial grounds for believing the person faces a real risk of serious harm meriting a grant of HP.

2.1.4 For further guidance on the 5 Refugee Convention grounds, see the Asylum Instruction, Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status

3. Risk

3.1.1 There are not substantial grounds for believing there is a real risk of serious harm in Syria because of a serious and individual threat to a civilian’s life or person by reason of indiscriminate violence in a situation of international or internal armed conflict, as defined in paragraphs 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules. The onus is on the person to demonstrate otherwise.

3.1.2 Even where there is not a real risk of serious harm by reason of indiscriminate violence in a situation of armed conflict in general, a person may still face a real risk of serious harm if they are able to show that there are specific reasons over and above simply being a civilian affected by indiscriminate violence.

3.1.3 However, paragraphs 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules only apply to civilians who must be non-combatants. This could include former combatants who have genuinely and permanently renounced armed activity.

3.1.4 Decision makers must consider each case on its facts.

3.1.5 In the case of Elgafaji (C-465/07), the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Justice (ECJ) set out that

‘– the existence of a serious and individual threat to the life or person of an applicant for subsidiary protection is not subject to the condition that that applicant adduce evidence that he is specifically targeted by reason of factors particular to his personal circumstances;

‘– the existence of such a threat can exceptionally be considered to be established where the degree of indiscriminate violence characterising the armed conflict taking place … reaches such a high level that substantial grounds are shown for believing that a civilian, returned to the relevant country or, as the case may be, to the relevant region, would, solely on account of his presence on the territory of that country or region, face a real risk of being subject to that threat.’ (para 43).

3.1.6 Whilst a country guidance case on Iraq, in QD (Iraq) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2009] EWCA Civ 620 (24 June 2009) the Court of Appeal held that ‘We would accept UNHCR’s submission that, for the purposes of article 15(c), there is no requirement that the armed conflict itself must be exceptional. What is, however, required is an intensity of indiscriminate violence – which will self-evidently not characterise every such situation – great enough to meet the test spelt out by the ECJ [in Elgafaji, above]’. (para 36).

3.1.7 The 14-year Syrian civil war involved multiple international, state and non-state actors. It resulted in hundreds of thousands of deaths and injuries, widespread damage to property and infrastructure, and millions of persons displaced internally, to neighbouring countries and beyond. However, the levels of violence decreased as different groups held control over different areas. HTS led the 11-day offensive which culminated in the toppling of Al-Assad in December 2024 (see Background to the conflict, relevant claim-specific Syria CPINs and the COI from previous, archived versions of this CPIN).

3.1.8 Even allowing for a spike in both total fatalities and civilian fatalities in the 2 weeks preceding and the week following the ousting of Al-Assad, the levels of indiscriminate violence involving civilians are so low, relative to the size of the respective populations, that it cannot be said that any remaining levels:

a. reach such a high level that substantial grounds are shown for believing that a civilian faces a real risk of serious harm simply by being present; and/or b. are ‘great enough to meet the test spelt out by the ECJ’ [in Elgafaji].

(see All conflict events and fatalities and Violence against civilians).

3.1.9 There are a few remaining contested areas within Syria, and an ongoing Israeli military presence in the buffer zone along the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights. These are:

- The outskirts of Deir ez-Zor

- The area to the south east of Raqqa/south of the Taqba dam

- The area to the east of Aleppo where the SNA-controlled area meets the SDF-controlled area

- The buffer zone along the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights

(see Territorial control after Assad’s fall).

3.1.10 However, any fighting in these areas appears sporadic. It does not reach the level of intensity outlined above.

3.1.11 Between 6-9 March 2025, sectarian violence took place on Syria’s Mediterranean coast. Whilst significant violence took place, with around 800 civilians killed, it was not considered to be indiscriminate violence as defined in paragraphs 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules because members of the Alawite community were specifically targeted. For guidance on claims related to the Alawite community and perceived Assadists, see the CPIN Syria: Alawites and Actual or Perceived Assadists.

3.1.12 For guidance on considering serious harm where there is a situation of indiscriminate violence in an armed conflict, including consideration of enhanced risk factors, see the Asylum Instruction, Humanitarian Protection.

4. Protection

4.1.1 The state is not able to provide protection against a breach of Article 3 ECHR because of indiscriminate violence in a situation of armed conflict if this occurs in individual cases.

4.1.2 For further guidance on assessing state protection, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

5. Internal relocation

5.1.1 The evidence in this and the other country policy and information notes on Syria does not indicate that there are restrictions on movement across state-controlled areas, or that any restrictions (for example, checkpoints) are unreasonable or insurmountable.

5.1.2 Whilst it is reasonable to conclude it must be possible, based on significant numbers of returnees from neighbouring countries such as Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq going to different onward destinations, the situation is unclear in areas controlled by other groups, and on travel between different areas.

5.1.3 Syria also remains one of the world’s most challenging humanitarian environments. This applies across the country as a whole. Therefore, even if it is reasonable to expect a person to move to a different location, it may be more challenging to show it is reasonable to expect them to stay there, especially if the person does not have a support network capable of ensuring access to their basic needs. Without this, internal relocation is unlikely to be reasonable.

5.1.4 For further guidance on considering internal relocation and factors to be taken into account see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

6. Certification

6.1.1 Where a claim is refused, it is unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

6.1.2 For further guidance on certification, see Certification of Protection and Human Rights claims under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 (clearly unfounded claims).

Country information

About the country information

This section contains publicly available or disclosable country of origin information (COI) which has been gathered, collated and analysed in line with the research methodology. It provides the evidence base for the assessment which, as stated in the About the assessment, is the guide to the current objective conditions.

The structure and content follow a terms of reference which sets out the general and specific topics relevant to the scope of this note.

This document is intended to be comprehensive but not exhaustive. If a particular event, person or organisation is not mentioned this does not mean that the event did or did not take place or that the person or organisation does or does not exist.

The COI included was published or made publicly available on or before 31 March 2025. Any event taking place or report published after this date will not be included.

Decision makers must use relevant COI as the evidential basis for decisions.

7. Background to the conflict

7.1 Assad regime and the civil war

7.1.1 In May 2023 the BBC summarised the events which led to the start of the civil war in 2011:

‘In March 2011, pro-democracy demonstrations erupted in the southern city of Deraa, inspired by uprisings in neighbouring countries against repressive rulers. When the Syrian government used deadly force to crush the dissent, protests demanding the president’s resignation erupted nationwide.

‘The unrest spread and the crackdown intensified. Opposition supporters took up arms, first to defend themselves and later to rid their areas of security forces. Mr Assad [then-President Bashar al-Assad] vowed to crush what he called “foreign-backed terrorism”.

‘The violence rapidly escalated and the country descended into civil war. Hundreds of rebel groups sprung up and it did not take long for the conflict to become more than a battle between Syrians for or against Mr Assad. Foreign powers began to take sides, sending money, weaponry and fighters, and as the chaos worsened extremist jihadist organisations with their own aims, such as the Islamic State (IS) group and al-Qaeda, became involved. That deepened concern among the international community who saw them as a major threat.

‘Syria’s Kurds, who want the right of self-government but have not fought Mr Assad’s forces, have added another dimension to the conflict.’[footnote 1]

7.1.2 A 19 December 2024 research briefing prepared by the House of Commons Library, citing other sources, summarised the main actors and events of the civil war:

‘Estimates vary, but between 350,000 and 606,000 people are estimated to have been killed in Syrian civil war since 2011. The Assad government also deployed chemical weapons, and Islamic State/Daesh rose to capture significant territory in both Iraq and Syria before losing its final Syrian territory in 2019.

‘Six foreign actors were involved militarily: Iran, Hezbollah, and Russia in support of Assad; the US against Islamic State and in support of the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces; Turkey in support of the Syrian National Army (both Turkey and the US acting in opposition to Assad); and Israel, targeting Hezbollah and Iranian forces…

‘The military intervention of Russia in 2015 was widely seen as a turning point, allowing Assad forces to expel the opposition from Syria’s second city, Aleppo. Most observers increasingly considered that Assad would hold onto power and Syria would become one of many “frozen conflicts” worldwide, with little change in military control. By 2020, Assad forces held around 60% to 70% of Syrian territory and, despite continued violence and fighting, there was little significant change in zones of control again until 2024.’[footnote 2]

7.2 Fall of Assad in December 2024

7.2.1 For information see the CPIN Syria: Returnees after fall of Al-Assad regime.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information in this section has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

8. Demography

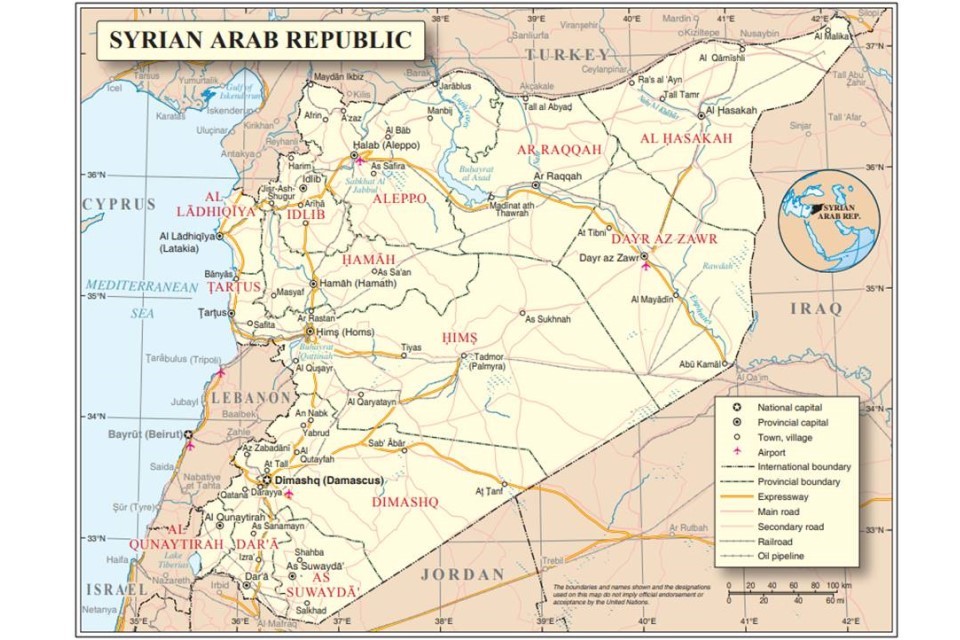

NOTE: The maps in this section are not intended to reflect the UK Government’s views of any boundaries.

8.1 Governorates

8.1.1 A UN map, dated August 2022, shows Syria’s governorates, cities and towns.[footnote 3]

Map of Syria

8.2 Population by governate and city

8.2.1 The below table was produced by CPIT using June 2024 data obtained from the UNOCHA Syria Population Task Force[footnote 4]:

| Governorate | Population |

|---|---|

| Aleppo | 4,754,560 |

| Al Hasakah | 1,447,069 |

| Ar Raqqa | 933,444 |

| Suwayda | 446,048 |

| Damascus | 1,812,584 |

| Dara | 1,081,657 |

| Deir Ez Zoir | 1,234,199 |

| Hama | 1,524,494 |

| Homs | 1,505,561 |

| Idleb | 3,179,920 |

| Lattakia | 1,299,538 |

| Quneitra | 149,374 |

| Rural Damascus | 3,395,491 |

| Tartous | 939,918 |

Note: CPIT has amended the spelling of some names with the aim of seeking consistency with the tables further down in the CPIN

9. Actors and areas of control

9.1 Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS)

9.1.1 Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) is a proscribed terrorist organisations in the UK.[footnote 5]

9.1.2 Reuters reported on 8 December 2024:

‘The most powerful group in Syria that spearheaded the rebels’ advance is the Islamist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham.

‘It started out as the official al Qaeda affiliate in Syria under the name Nusra Front, staging attacks in Damascus from early in the uprising against Assad.

‘Its leader Ahmed al-Sharaa, who for years used the nom de guerre Abu Mohammed al-Golani, decided to split first from the nascent Islamic State group, and then in 2016 from the global al Qaeda organisation.

‘It went through several name changes, eventually rebranding as HTS, as it became the strongest group in the main rebel enclave around Idlib province in the northwest.

‘HTS and its leader have been designated terrorists by the United States, Turkey and others, but continued to fight alongside mainstream rebel groups and backed an administration in Idlib that they called the Salvation Government.’[footnote 6]

9.1.3 The 8 December 2024 ISPI article cited commentary from ‘experts from the ISPI network’, including Silvia Carenzi an Associate Research Fellow at ISPI who opined:

‘While uncertainties and concerns for Syria’s transition and its future are more than understandable – and it is too early to make predictions – securitized interpretations that emphasize “jihadism” are misleading. Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) has been undergoing a path of political maturation over the past years – not only as it severed its ties to al-Qa‘ida, but also as its governance has experienced changes too. Sheer comparisons between HTS and the Taliban neglect two key points: first, the very different contexts that Syria and Afghanistan are; secondly, the organizational differences between HTS and the Taliban – as HTS’s evolution saw the sidelining of those deemed as “hardliners”, and its leadership is in the hand of more pragmatic and politically savvy figures, open to deals and compromises. The Repelling the Aggression operation – led by HTS, but that includes an array of other armed opposition groups – is highly popular domestically. To fully reap its fruits, HTS will have to engage in coalition-building and power-sharing with other actors and keep its word on promises of inclusiveness.’[footnote 7]

9.1.4 On 17 December 2024, The New Arab reported on a meeting attended by HTS leader Ahmed al-Sharaa where ‘he said all rebel factions would “be disbanded and the fighters trained to join the ranks of the defence ministry”.’[footnote 8]

9.1.5 The 19 December 2024 TIMEP article stated: ‘Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, which spearheaded the initial and largest offensive, now controls most of the territories seized from the regime, particularly in major urban centers such as Aleppo and Damascus. HTS has emerged as the dominant power in these areas, solidifying its influence over key cities.’[footnote 9]

9.1.6 On 13 February 2025, the Arab Center Washington DC, a US-based ‘nonprofit, independent, and nonpartisan research organization’[footnote 10] wrote:

‘On January 29, 2025, Ahmed al-Sharaa was named president of Syria for a transitional period and the country’s constitution was suspended. Seven weeks after leading Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) in an offensive that overthrew Bashar al-Assad’s presidency, al-Sharaa was also authorized to form a temporary legislative council to govern the country until a new constitution is adopted… While Syria’s new president laid out ambitious goals to rebuild state institutions and develop the economy, he has said that it may take up to four years to write up a new constitution and hold formal elections, raising concerns about prolonged uncertainty over governance, the rebuilding process, and the future of the Syrian people.’[footnote 11]

9.1.7 See also section 2.1.1 of the European Union Asylum Agency’s (EUAA) March 2025 COI Report - Syria: Country Focus. However, refer to the relevant footnote(s) as that report and this note have used the same or similar sources and reports in places.

9.2 Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA)

9.2.1 On 8 December 2024 Reuters reported:

‘Turkey sent troops into Syria from 2016 to push Kurdish groups and Islamic State away from its borders. A key supporter of the rebels, it eventually formed some of the groups into the Syrian National Army which, backed by direct Turkish military power, held a stretch of territory along the Syrian-Turkish border. As HTS and allied groups from the northwest advanced on Assad last week, the SNA also joined them, fighting government forces and Kurdish-led forces in the northeast.’[footnote 12]

9.2.2 The 19 December 2024 TIMEP article stated: ‘The Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA) retains control over territories it held prior to the offensive in northern Syria – including Azaz, al-Bab, Jarablus, and Afrin – along with newly captured areas, particularly in the eastern countryside of Aleppo.’[footnote 13]

9.2.3 On 13 January 2025, BBC Monitoring described the main factions of the SNA: ‘The SNA initially consisted of factions based in Aleppo province. This was expanded in 2019 to include Idlib province-based National Liberation Front (NLF) formations. The geographic separation between the Aleppo-based SNA factions and the Idlib-based NLF meant that in practical terms these two entities have retained a high degree of mutual autonomy.’[footnote 14]

9.2.4 The same BBC Monitoring article named the main members of the 2 SNA factions:

- Aleppo province-based factions:

Levant Front, Sultan Murad Division, Jaysh al-Islam, Joint Force (Al-Hamza Division and Sultan Suleiman Shah Division), Liberation and Construction Movement (LCM), Mutasim Division, Second Division (made up of Jaysh al-Nukhba and 113th Brigade), Sultan Malik Shah Division, Majd Corps, and Sham Corps

- Idlib province-based factions:

National Liberation Front (NLF) (including hrar al-Sham, Nour al-Din al-Zenki Movement, Suqur al-Sham Brigades, Jaysh al-Ahrar, Jaysh al-Nasr and the Free Idlib Army)[footnote 15]

9.2.4 See also section 2.1.2 of the European Union Asylum Agency’s (EUAA) March 2025 COI Report - Syria: Country Focus. However, refer to the relevant footnote(s) as that report and this note have used the same or similar sources and reports in places.

9.3 Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF)

9.3.1 An article dated 27 January 2025 on the website of the Syrian Democratic Council (SDC) explained: ‘The SDC is the political leadership of the Democratic Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (DAANES) and the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF)…’[footnote 16]

9.3.2 The Guardian reported on 9 December 2024:

‘The Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) is a Kurdish dominated alliance that holds a vast swathe of territory in north-east Syria and is backed by the US. The SDF, which includes some Arab fighters, was founded in 2015 and did much of the hardest fighting against IS. Led by the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG), the SDF is viewed by Ankara as part of the broader Kurdish separatist movement that has fought a bloody nationalist campaign against Turkey for decades.’[footnote 17]

9.3.3 On 9 February 2025, the Observer noted that female-only units of Kurdish soldiers, the YPJ (translated as ‘Women’s Protection Units’[footnote 18] ‘… are now part of the Syrian Democratic Forces, the autonomous administration’s army, which is now in fraught negotiations about whether and how it can become part of a new national Syrian army led from Damascus.’[footnote 19]

9.3.4 The 19 December 2024 TIMEP article stated:

‘… the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) – a multi-ethnic coalition and a key US partner in the fight against ISIS – continue to govern regions in northeastern Syria, including Hassakeh, Raqqa, and the countrysides of Deir Ezzor and Aleppo. However, the SDF has experienced a reduction in its territory, having lost Manbij and other areas in the Deir Ezzor governorate following the regime’s collapse, due to clashes with Turkish-backed opposition groups.’[footnote 20]

9.3.5 Al Jazeera reported on 6 January 2025: ‘The SDF currently controls a large swath of northeast Syria, accounting for nearly a third of the country’s overall territory. The land it controls contains about 70 percent of Syria’s oil and gas fields.’[footnote 21]

9.3.6 On 21 January 2025 The New Arab, a London-based news website, reported:

‘The collapse of Bashar Al-Assad’s brutal regime in Syria in early December gave rise to hopes that an end to the country’s lengthy civil war was finally on the horizon.

‘However, clashes continue in the north between militias operating under the umbrella of the self-styled, Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA) on one side, and the US-backed, Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) on the other. And there is little sign of any let-up.

‘When Syrian opposition forces led by the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) group captured Syria’s second city, Aleppo, in late November, the SNA launched a concurrent offensive targeting Kurds in that province that displaced tens of thousands of civilians.

‘Clashes with the SDF ensued, with the latter group losing ground west of the Euphrates River, most notably Tel Rifaat and Manbij…

‘The UK-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights war monitor estimates that at least 423 people have been killed in this SNA-SDF conflict since 12 December; 41 of them civilians, 308 SNA, and the remaining 74 SDF fighters.’[footnote 22]

9.3.7 BBC Monitoring reported on 11 March 2025:

‘Syria’s Islamist-led government has reached an agreement with a Kurdish-led militia alliance, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) to integrate into the new Syrian state…

‘The eight-point deal includes a full ceasefire and recognises the Kurdish minority as “an integral part of the Syrian state” with “full citizenship rights and all constitutional protections”…

‘”All civil and military institutions in north-eastern Syria, including border crossings, airports, and oil and gas fields, will be integrated under Syrian state control,” it said.

‘The deal committed the SDF to supporting the Syrian state in combating “Assad’s remnants and all threats to national security and unity”.’[footnote 23]

9.3.8 See also section 2.1.4 of the European Union Asylum Agency’s (EUAA) March 2025 COI Report - Syria: Country Focus. However, refer to the relevant footnote(s) as that report and this note have used the same or similar sources and reports in places.

9.4 Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS)

9.4.1 Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) is a proscribed terrorist organisations in the UK.[footnote 24]

9.4.2 A 16 July 2024 press release from U.S. Central Command, which has responsibility for defending U.S. interests in the Middle East and Asia[footnote 25] stated:

‘From January to June 2024, ISIS has claimed 153 attacks in Iraq and Syria. At this rate, ISIS is on pace to more than double the total number of attacks they claimed in 2023. The increase in attacks indicates ISIS is attempting to reconstitute following several years of decreased capability.

‘…United States Central Command, along with our Defeat ISIS partners, Iraqi Security Forces and the Syrian Democratic Forces, conducted 196 Defeat ISIS Missions resulting in 44 ISIS operatives killed and 166 detained in the first half of 2024… In Syria, 59 operations conducted alongside the SDF and other partners resulted in 14 ISIS operatives killed and 92 ISIS operatives detained…

‘The continued pursuit of the approximately 2,500 ISIS fighters at large across Iraq and Syria is a critical component to the enduring defeat of ISIS.’[footnote 26]

9.4.3 On 10 December 2024 BBC Monitoring, citing other sources, reported:

‘The Islamic State group (IS) is bitterly opposed to the rebel factions, including militant group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS)… Nevertheless, the jihadist group has been looking for ways to exploit the situation [of Assad’s fall] to establish more definitive footholds across the country.

‘After several years of steady decline in IS-claimed activity in Syria, 2024 has seen a notable rebound in attacks, mainly in the east of the country. IS propaganda has consistently emphasised the necessity of attacks to free thousands of jihadist suspects held in huge detention camps in eastern Syria.

‘Around 2014, sizeable areas of eastern Syria fell under the sway of IS’s so-called caliphate. However, by 2019, Western and regional forces had succeeded in beating IS back and capturing its last foothold of territory at the village of Baghouz in south-eastern Syria…

‘Between 2019 and 2023, IS activity in Syria and Iraq steadily fell year-on-year…

‘The jihadist group is understood to have largely based itself in the remote Badia desert region of central Syria. Most IS attacks have tended to be in the eastern Hasaka and Deir-al-Zour provinces…

‘2024 was notable for a sizeable increase in the group’s claims [of attacks] in Syria. This included high-casualty attacks against pro-Assad military forces.

‘… [IS’s activity in Syria] for the first quarter of the year [2024] saw a threefold increase compared with 2023.

‘By far, the most frequent target of IS attacks has been the SDF, which wields security control over much of eastern Syria.’[footnote 27]

9.4.4 On 9 January 2025, the CFR stated ‘While the bulk of ISIS has been largely defeated, it continues to recruit and operate in Syria and beyond. The recently deposed regime of Bashar al-Assad, weakened by civil war, had never managed to impose its authority in significant parts of the country and had thus relinquished the fight against the Islamic State to the Americans and the Syrian Kurds.’[footnote 28]

9.4.5 On 26 February 2025, the BBC reported: ‘It’s estimated that there are still about 40,000 IS family members and up to 10,000 jihadist fighters held in SDF-controlled camps and prisons in the north-east, says [SDF commander] Gen Abdi.’[footnote 29]

9.4.6 On 23 February 2025, the Middle East Forum reported that ‘[since 2019, ISIS] … has been sporadically active in its heartland and birthplace, Iraq, in Syria and further afield. There are now indications that its activities are once more on the rise. The revival of ISIS preceded the sudden fall of the Assad regime in December [2024]. In the course of that year, attacks by the organisation tripled in comparison to 2023.’[footnote 30]

9.4.7 See also section 2.1.5 of the European Union Asylum Agency’s (EUAA) March 2025 COI Report - Syria: Country Focus. However, refer to the relevant footnote(s) as that report and this note have used the same or similar sources and reports in places.

9.5 Other armed groups

9.5.1 The 9 December 2024 Guardian article stated: ‘The Southern Operations Room is a newly formed coalition of rebel groups in southern and south-eastern Syria, drawn mainly from Druze communities and opposition groups. The region was an early stronghold of opposition to the Assad regime but suffered heavily from brutal repression.’[footnote 31]

9.5.2 The 19 December 2024 TIMEP article stated: ‘In southern Syria, including the governorates of Daraa and Sweida, local armed groups – long active in these regions – have assumed control after liberating their areas from regime forces. In more rural regions outside major urban centers, power often rests with former opposition fighters, many of whom were previously displaced or demobilized but have now reasserted local authority.’[footnote 32]

9.5.3 See also section 2.1.3 of the European Union Asylum Agency’s (EUAA) March 2025 COI Report - Syria: Country Focus. However, refer to the relevant footnote(s) as that report and this note have used the same or similar sources and reports in places.

9.6 Israel

9.6.1 On 16 December 2024, Al Jazeera reported:

‘Among Israel’s recent violations of Syrian sovereignty, which include hundreds of air attacks, is its renewed encroachment into the Golan Heights – with tanks and illegal settlements…

‘The Golan Heights are part of Syria, as recognised by the United Nations. However, Israel occupied the Golan during the 1967 War and currently controls 1,200sq km (463sq miles) of the western part of the region…

‘… Israel has built more than 30 settlements in the area, where more than 25,000 Jewish Israelis live. And it is still signalling that it wants to build more…

‘This is not happening in isolation, as Israel is also attacking sites across Syria, claiming that it is doing so in “self defence”.’[footnote 33]

9.6.2 On 18 December 2024, Voice of America (VoA), a U.S. broadcaster funded by the U.S. Congress, reported:

‘New details have emerged of Israel’s occupation of a Golan Heights buffer zone since Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad fell from power this month…

‘A spokesperson for U.N. peacekeeping operations told VOA… that the U.N. Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF) has identified at least 10 locations occupied by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) in the buffer zone as of December 15 [2024].

‘The zone, which the United Nations calls an Area of Separation, is on the Syrian side of a 1974 ceasefire line that had divided Israeli and Syrian-administered territory following the 1973 Arab-Israeli war. Under the ceasefire, the area was intended to separate, or be free of, Syrian and Israeli forces.

‘UNDOF has called Israel’s latest actions in the zone a “violation” of the ceasefire agreement.

‘The zone is 75 kilometers long, spanning from the peak of Mount Hermon in the north to the Yarmouk River along the Jordanian border in the south… The area is home to 11 Syrian towns and villages, with tens of thousands of residents…

‘Israel has said its occupation of the buffer zone is a temporary measure to prevent Syrian armed groups that ousted Assad from threatening Israeli territory.’[footnote 34]

9.6.3 On 18 December 2024, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR) ‘an independent and impartial UK-based human rights organisation’[footnote 35] documented 498 Israeli airstrikes on Syria in the aftermath of the fall of Assad and noted: ‘…Israeli airstrikes have destroyed Syria’s military assets, where the airstrikes focused on Syrian airbases and their contents, including warehouses, aircraft, radar systems and military signal stations, scientific research centres and weapons and ammunitions warehouses in different positions across Syria. The attacks resulted in complete suspension of air-defences and put all targeted positions out of service.’[footnote 36]

9.6.4 ABC News reported on 25 February 2025: ‘Israel confirmed it is conducting strikes in southern Syria… [Israeli Defence Minister Israel Katz] said the Israeli Air Force is “now attacking strongly in southern Syria as part of the new policy we have defined of pacifying southern Syria.”… Israel confirmed the strikes after Syrian state media reported several aircraft strikes near Damascus.’[footnote 37]

9.6.5 On 11 March 2025, BBC Monitoring reported: ‘The Israeli army said early on 11 March that it had carried out a wave of air strikes on Syria, with targets including military headquarters, weapons depots and radar and detection equipment. In a post on X, the army said that the assets in southern Syria had posed a threat to Israel and its military operations and the attacks were intended to “eliminate future threats”.’[footnote 38]

9.6.6 See also section 3.1.5 of the European Union Asylum Agency’s (EUAA) March 2025 COI Report - Syria: Country Focus. However, refer to the relevant footnote(s) as that report and this note have used the same or similar sources and reports in places.

9.7 United States of America (USA)

9.7.1 On 9 December 2024, the U.S. Department of Defense announced: ‘On Saturday, U.S. forces conducted precision airstrikes in central Syria against known ISIS camps and operatives. As part of the operation, U.S. Air Force fighter and bomber aircraft struck more than 75 targets.’[footnote 39]

9.7.2 On 19 December 2024, the U.S. Department of Defense announced that approximately 2,000 U.S. troops were deployed in Syria. The spokesperson explained that 900 of the personnel were ‘core’ assets on longer term deployments and 1,100 of the personnel were ‘”temporary rotational forces” — often in theater for 30 to 90 days — that are deployed to meet the fluid mission requirements of U.S. Central Command’s area of responsibility’.[footnote 40]

9.7.3 On 9 January 2025, the CFR stated: ‘The United States began helping the Kurdish militia, known as the People’s Defense Units (YPG), fight against the self-declared Islamic state, also known as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), in 2014 when the radical group controlled large swathes of those two countries. The U.S. military and the YPG, which later reconfigured into the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), succeeded in beating back ISIS, and their alliance endures to this day….’[footnote 41]

9.7.4 See also section 3.1.4 of the European Union Asylum Agency’s (EUAA) March 2025 COI Report - Syria: Country Focus. However, refer to the relevant footnote(s) as that report and this note have used the same or similar sources and reports in places.

9.8 Russia

9.8.1 On 16 December 2024, CNN reported that Russia had begun a withdrawal of military equipment and troops from its 2 bases in Syria, a port facility at Tartus and Khmeimim airbase in Latakia.[footnote 42]

9.8.2 An article published on 27 January 2025 by the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS), a Tel Aviv-based ‘independent think tank influencing Israel’s long-term national security policy’[footnote 43] stated:

‘Russia emerged as the most dominant political and military force in Syria when it sent its troops to support the Assad regime at the height of the civil war in September 2015. However, with the downfall of the Assad regime, Russia now finds itself in a weakened position vis-à-vis the rebel forces. Until recently, Russia had launched airstrikes against them and classified them as terrorists; now it is dependent on the same rebels to ensure the security of its soldiers and its remaining military assets in Syria, while hoping that the new regime will allow it to retain at least some presence in the country…

‘Since the downfall of the Assad regime on December 8, the Russian forces deployed in Syria have gathered at three permanent military bases—the Khmeimim Air Base, the Tartus Naval Base, and Qamishli in the Kurdish region in northern Syria—having withdrawn their personnel and posts from across the country. These include positions in the south, north, and northeast, as well as the Syrian desert and cities such as Damascus, Aleppo, and Deir al-Zur…’[footnote 44]

9.8.3 On 25 February 2025, the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP) ‘one of Europe’s largest foreign policy think-tanks’[footnote 45] stated:

‘… Russia, which had intervened in Syria from September 2015 onwards to ensure Assad remained in power, was unable to prevent the Syrian president’s overthrow at the end of 2024…

‘Moscow’s military presence in Syria had always been limited. Estimates suggest that in 2024, the Russian contingent numbered around 7,500 personnel and comprised mainly air force units, special forces and military police. The number of ground troops, which was low from the beginning, dwindled further following the redeployment of “Wagner” fighters to Ukraine from 2022 onwards… Russia’s intervention model reached its limits when confronted with the 2024 rebel offensive. Assad’s troops offered little resistance and/or rapidly collapsed, including the Fifth Corps of the Syrian army, which had received strong financial and military support from Moscow…

‘Russia’s top and immediate priority right now is to retain its military bases in Syria, particularly the Tartus naval base and the Hmeimim military airfield, both of which are essential not only for operations in Syria but also for Russia’s military posture in the broader region… Against this background, Moscow is seeking to reach a deal with the new Syrian leadership on the continued operation of its two military bases.’[footnote 46]

9.8.4 See also section 3.1.2 of the European Union Asylum Agency’s (EUAA) March 2025 COI Report - Syria: Country Focus. However, refer to the relevant footnote(s) as that report and this note have used the same or similar sources and reports in places.

10. Maps of territorial control

NOTE: The maps in this section are not intended to reflect the UK Government’s views of any boundaries.

10.1 Territorial control under the Assad regime

10.1.1 A map produced by Al Jazeera showed territorial control on November 26 2024 (prior to the rebel offensive which began on November 27).[footnote 47]

10.2 Territorial control after Assad’s fall

10.2.1 On 8 December 2024, ISPI, citing Syria Liveumap and Al Jazeera, produced the following map showing who controlled what in Syria.[footnote 48]

10.2.2 On 22 January 2025, the Syria Justice and Accountability Centre, a US-based human rights organisation[footnote 49] stated: ‘The new Syrian government, currently a caretaker government led by Hayat Tahrir Al-Sham, now controls the majority of Syrian territory, including Daraa, Suwayda, Damascus, Rif Damascus, Homs, Hama, Latakia, Tartous, and Idlib governorates, along with parts of Aleppo, Deir Ezzor, Al-Raqqa governorates.’[footnote 50]

10.2.3 The SJAC produced a map showing areas of control in January 2025.[footnote 51]

Key: Green = interim authorities; Orange = SDF/AANES; Red = Turkiye and proxy forces under the Syrian National Army (SNA); Blue = Golan Heights; Crosshatched = contested.

10.2.4 The Institute for the Study of War (ISW) and the American Enterprise Institute’s (AEI) Critical Threats Project team (CTP), produced an interactive map which is regularly updated. The latest version is accessible here. As of 4 March 2025, the most recent map showed territorial control on 28 February 2025:[footnote 52]

10.2.5 ISW and AEI explained that Lost Regime Territory ‘…represents territory that the Assad Regime used to control before November 27, 2024… Opposition rebel groups are very likely operating in areas within the Lost Regime Territory Layer.’[footnote 53]

10.2.6 CFR published a map on 9 January 2025. Using the ISW and AEI as its sources, together with the Congressional Research Service, CFR produced a map which showed areas of territorial control as well as the locations of recent ISIS activity.[footnote 54]

11. Sources of conflict data

11.1.1 Syrian Network for Human Rights

11.1.1 The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) is a NGO which monitors and documents human rights violations in Syria and which ‘is a primary source for the United Nations on all death toll-related statistics in Syria.’[footnote 55]

11.1.2 SNHR publishes monthly reports documenting civilian deaths including breakdowns of deaths by location and perpetrator. SNHR’s report covering civilian deaths in January 2025, explained the methodology used to compile the statistics: ‘This report draws upon the SNHR team’s constant daily monitoring of news and developments in Syria, and on information supplied by our extensive and varied countrywide network… SNHR also provides a special form that can be completed by victims’ relatives… [so SNHR can] verify its accuracy before adding it to the database.’[footnote 56]

11.1.3 SNHR’s report covering civilian deaths in February 2025 noted: ‘The fatalities recorded in this report are limited to civilian deaths documented in the preceding month. Some of these deaths may have taken place months or years before and only have been formally confirmed or documented during the past month…’[footnote 57]

11.1.4 The same SNHR report also noted: ‘… it is important to note that this report represents only the bare minimum of the scale and severity of documented violations due to the ongoing difficulties in documentation.’[footnote 58]

11.2 Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED)

11.2.1 ACLED describes itself as, ‘An independent, impartial, international non-profit organization collecting data on violent conflict and protest in all countries and territories in the world.’[footnote 59]

11.2.2 ACLED researchers gather information from 4 categories of sources: traditional media, reports by international institutions and non-governmental organisations (NGOs), local partners, and through targeted use of social media. ACLED explained ‘Sourcing lists are carefully curated and monitored to maintain accurate coverage.’[footnote 60]

12. All conflict events and fatalities

12.1 Number and type of conflict events

12.1.1 ACLED categorises data into 6 event types and 25 sub-event types. ACLED’s 6 event types plus brief definitions are provided below. More detail, including examples of the types of events recorded in each category, is provided in ACLED’s codebook[footnote 61]:

- Battles: ‘a violent interaction between two organized armed groups’[footnote 62]

- Protests: ‘an in-person public demonstration of three or more participants in which the participants do not engage in violence, though violence may be used against them’[footnote 63]

- Riots: ‘violent events where demonstrators or mobs of three or more engage in violent or destructive acts, including but not limited to physical fights, rock throwing, property destruction, etc’[footnote 64]

- Explosions/remote violence: ‘incidents in which one side uses weapon types that, by their nature, are at range and widely destructive’[footnote 65]

- Violence against civilians: ‘violent events where an organized armed group inflicts violence upon unarmed non-combatants’[footnote 66]

- Strategic developments: ‘captures contextually important information regarding incidents and activities of groups…. [that] may trigger future events or contribute to political dynamics within and across states’[footnote 67]

12.1.2 See also pages 10-13 of the European Union Asylum Agency’s (EUAA) March 2025 COI Report - Syria: Country Focus which discuss ACLED and other sources and their respective data sets. However, refer to the relevant footnote(s) as that report and this note have used the same or similar sources and reports in places.

12.1.3 CPIT has used ACLED data to compare the number and type of events for the 12 week period up to and after the fall of Assad. To note that at the time of the analysis the most recent ACLED information was dated 28 February 2025. Therefore, the final week of the data used to compile the table (week commencing 24 February 2025) consists of 5-days, not 7.[footnote 68]

| Event type | 12 week period up to the fall of Assad (16 September 2024 to 8 December 2024) | 12 week period after the fall of Assad (9 December 2024 to 28 February 2025) | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explosions/ remote violence | 2,248 | 1096 | ↓ 51% |

| Battles | 813 | 502 | ↓ 38% |

| Strategic developments | 769 | 765 | ↓ 0.5% |

| Violence against civilians | 361 | 652 | ↑ 81% |

| Protests | 198 | 215 | ↑ 9% |

| Riots | 20 | 10 | ↓ 50% |

| All event types | 4,409 | 3240 | ↓ 27% |

12.2 Fatalities

12.2.1 ACLED noted: ‘Fatality data are typically the most biased, and least accurate, component of conflict reporting. They are particularly prone to manipulation by armed groups, and occasionally the media, which may overstate or underreport fatalities for political purposes. These figures should therefore be understood as indicative estimates of reported fatalities, rather than definitive fatality counts.’[footnote 69]

12.2.2 The ACLED database provides ‘…the estimated number of reported fatalities associated with a single event. ACLED does not collect data on injuries, nor are fatalities attributed to specific groups.’[footnote 70] In other words, the ACLED fatalilty estimate combines all deaths arising from a single event, including both civilian and combatant.

12.2.3 However, the ACLED dataset ‘allows for filtering of events in which civilians were the main or only target of an event.’[footnote 71] Filtering events by ‘Civilian targeting’ allows the user to estimate civilian fatalities, although the estimate will exclude civilians ‘… that may have died as “collateral damage” during fighting between armed groups or as a result of the remote targeting of armed groups (e.g. an air strike hitting militant positions that also kills civilians).’[footnote 72]

12.2.4 CPIT has used ACLED data to produce a graph comparing all recorded fatalities (a combination of civilian and combatant) against an estimate of civilian fatalities (based on civilian targeting events) over the 12 week period up to and after the fall of Assad. To note that at the time of the analysis ACLED data was available until 28 February 2025. Therefore, the final week represented on the graph (week commencing 24 February 2025) consists of 5-days, not 7.[footnote 73]

12.2.5 The graph indicates:

- A spike in both total fatalities and civilian fatalities in the 2 weeks preceding and the week following the ousting of Assad.

- Between the week commencing 16 December and the week commencing 27 January both total fatalities and civilian fatalities remaind relatively constant.

- From 3 February 2025 both indicators exhibit a downward trend.

13. Violence against civilians

13.1 ACLED ‘civilian targeting’ filter

13.1.1 ACLED’s codebook explained:

‘In order to facilitate the analysis of all events in the ACLED dataset that feature violence targeting civilians, the ‘Civilian targeting’ column allows for filtering of events in which civilians were the main or only target of an event. Besides events coded under the ‘Violence against civilians’ event type, civilians may also be the main or only target of violence in events coded under the ‘Explosions/Remote violence’ event type (e.g. a landmine killing a farmer), ‘Riots’ event type (e.g. a village mob assaulting another villager over a land dispute), and ‘Excessive force against protesters’ sub-event type (e.g. state forces using lethal force to disperse peaceful protesters). Events in which civilians were incidentally harmed are not included in this category.’[footnote 74]

13.2 Nature of violence

13.2.1 To analyse the nature of events targeting civilians CPIT filtered the ACLED data by ‘civilian targeting’ for the 12-week period before and after the fall of Assad. The graph below tracks the types of event recorded by ACLED as ‘civilian targeting’: Explosions/ remote violence, Violence against civilians, and Protests (excessive force against protesters) and riots. To note that at the time of the analysis ACLED data was available until 28 February 2025. Therefore, the final week of the graph (week commencing 24 February 2025) consists of 5-days data, not 7.[footnote 75]

13.2.2 The graph indicates:

- Total civilian targeting events began to rise in mid-November 2024 and hit a peak of 105 events in the week commencing 27 January 2025. After this date total civilian targeting events dropped sharply to their lowest level throughout the 24-week period.

- Violence against civilians follows a similar pattern to total civilian targeting events, rising from the start of December 2024 and peaking at 85 events in the week commencing 27 January 2025. After this date violence against civilians dropped sharply to its lowest level throughout the 24-week period.

- Explosions/ remote violence rose steadily to a peak of 46 in the week commencing 30 December 2024 and then dropped sharply before levelling out and then falling to its lowest level throughout the 24-week period.

- Protests (excessive force against protesters) and riots remained very low throughout the 24-week period. A maximum of 6 events were recorded in the week following Assad’s fall (week commencing 9 December 2024).

13.3 Actors involved in violence against civilians

13.3.1 SNHR’s monthly reports provide a breakdown of civilian deaths by perpetrator. However, a large proportion of the deaths recorded by SNHR are attributed to ‘other’ or ‘unidentified’ parties, which limits the validity of any conclusions which can be drawn from the data. A new category of perpetrator ‘General security forces’ was introduced by SNHR in its February 2025 report. This category includes ‘Security and military forces affiliated with the current transitional authority.[footnote 76] CPIT has compiled the table below using data from SNHR’s monthly reports covering the period September 2024 to February 2025.[footnote 77] [footnote 78] [footnote 79][footnote 80][footnote 81] [footnote 82] The table shows the number of recorded civilian deaths per month by perpetrator.

| Perpetrator | Sept 24 | Oct 24 | Nov 24 | Dec 24 | Jan 25 | Feb 25 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDF | 1 | 3 | 11 | 108 | 21 | 5 |

| Assad regime forces | 18 | 12 | 11 | 223 | 9 | 0 |

| SNA/ opposition factions | 2 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 1 |

| US-led international coalition | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Russian forces | 0 | 11 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| HTS | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| General security forces | - | - | - | - | - | 13 |

| Other/ unidentified | 29 | 61 | 47 | 151 | 201 | 203 |

| Total | 50 | 89 | 71 | 503 | 236 | 222 |

13.4 Civilian fatalities

13.4.1 CPIT has produced a graph which compares ACLED and SNHR data on civilian fatalities recorded each month over the period January 2023 to February 2025.[footnote 83] [footnote 84] CPIT applied a filter of ‘Civilian targeting’ to the ACLED data to provide the civilian fatality estimates.

13.4.2 The graph indicates:

- ACLED and SNHR data both chart a similar trend in civilian fatalities.

- Both sources recorded a spike in civilian fatalities in December 2024 (the month of Assad’s ousting).

- Both sources recorded a sharp fall in civilian fatalities after December 2024, although the figures for February 2025 remain relatively high when compared against the preceding monthly totals.

13.5 Civilian fatalities by location

13.5.1 CPIT has produced the table below which compares SNHR and ACLED data on civilian fatalites per governorate for the 2 complete months since the fall of Assad (January and February 2025).[footnote 85] [footnote 86] [footnote 87]

| Civilian fatalities recorded in January and February 2025 by governorate | ACLED recorded fatalities | ACLED rank | SNHR recorded fatalities | SNHR rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aleppo | 175 | 1 | 135 | 1 |

| Homs | 124 | 2 | 45 | 4 |

| Hama | 81 | 3 | 75 | 2 |

| Deir ez Zoir | 31 | 4 | 56 | 3 |

| Lattakia | 27 | 5 | 31 | 6 |

| Rural Damascus | 26 | 6 | 9 | 11 |

| Ar Raqqa | 23 | = 7 | 13 | = 8 |

| Idleb | 23 | = 7 | 41 | 5 |

| Al Hasakeh | 19 | = 9 | 6 | 12 |

| Tartous | 19 | = 9 | 11 | 10 |

| Dara | 15 | 11 | 19 | 7 |

| As Sweida | 7 | 12 | 13 | = 8 |

| Damascus | 6 | 13 | 3 | 13 |

| Quneitra | 0 | 14 | 1 | 14 |

| Total civilian fatalities in January and February 2025 | 576 | 458 |

13.5.2 A comparison of the ACLED and SNHR data indicates a consistency across both sources regarding which governorates sustained the highest number of civilian fatalities in January and February 2025:

- Of the 5 highest ranked governorates according to ACLED data, 4 of the governorates are also ranked in SNHR’s top 5.

- The exceptions are firstly, Lattakia which was ranked 5th by ACLED and 6th by SNHR and, secondly, Idleb which was ranked 5th by SNHR and 7th by ACLED.

13.5.3 CPIT has used ACLED data to analyse the distribution of civilian targeting events and civilian fatalities across Syria’s 14 governorates. The graph below shows the geographic split of events and fatalities recorded during the 12-week period after the fall of Assad. To note that at the time of the analysis ACLED data was available until 28 February 2025. Therefore, the final week’s data (week commencing 24 February 2025) consists of 5-days data, not 7.[footnote 88]

13.5.4 The graph indicates a clustering of civilian fatalities with 3 governorates (Aleppo, Homs and Hama) accounting for over 63% of all recorded civilian deaths. CPIT has produced the table below which shows the absolute and relative number of civilian fatalities per governorate during the 12 week period 9 December 2024 to 28 February 2025.[footnote 89] Actual and relative population size have been provided for comparison.

| Governorate | Civilian fatalities | % of all fatalities | Population | % of total population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aleppo | 243 | 25.8 | 4,754,560 | 0.0051 |

| Homs | 212 | 22.5 | 1,505,561 | 0.0141 |

| Hama | 139 | 14.8 | 1,524,494 | 0.0091 |

| Deir ez Zoir | 80 | 8.5 | 1,234,199 | 0.0065 |

| Ar Raqqa | 57 | 6.1 | 933,444 | 0.0061 |

| Lattakia | 40 | 4.3 | 1,299,538 | 0.0031 |

| Rural Damascus | 38 | 4.0 | 3,395,491 | 0.0011 |

| Idleb | 31 | 3.3 | 3,179,920 | 0.0010 |

| Al Hasakeh | 28 | 3.0 | 1,447,069 | 0.0019 |

| Dara | 27 | 2.9 | 1,081,657 | 0.0025 |

| Tartous | 24 | 2.6 | 939,918 | 0.0026 |

| Damascus | 12 | 1.3 | 1,812,584 | 0.0007 |

| As Sweida | 10 | 1.1 | 446,048 | 0.0022 |

| Quneitra | 0 | 0 | 149,374 | 0.0000 |

| Total | 941 | 100.2 | 23,703,857 |

Note: caution should be attached to the percentages cited in the above given all the figures are estimates.

13.5.5 See also section 4.5 of the European Union Asylum Agency’s (EUAA) March 2025 COI Report - Syria: Country Focus. However, refer to the relevant footnote(s) as that report and this note have used the same or similar sources and reports in places.

13.6 Events on Syria’s Mediterranean coast, 6–9 March 2025

13.6.1 For information see the CPIN Syria: Alawites and Actual or Perceived Assadists.

Research methodology

The country of origin information (COI) in this note has been carefully selected in accordance with the general principles of COI research as set out in the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), April 2008, and the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation’s (ACCORD), Researching Country Origin Information – Training Manual, 2024. Namely, taking into account the COI’s relevance, reliability, accuracy, balance, currency, transparency and traceability.

Sources and the information they provide are carefully considered before inclusion. Factors relevant to the assessment of the reliability of sources and information include:

- the motivation, purpose, knowledge and experience of the source

- how the information was obtained, including specific methodologies used

- the currency and detail of information

- whether the COI is consistent with and/or corroborated by other sources

Commentary may be provided on source(s) and information to help readers understand the meaning and limits of the COI.

Wherever possible, multiple sourcing is used and the COI compared to ensure that it is accurate and balanced, and provides a comprehensive and up-to-date picture of the issues relevant to this note at the time of publication.

The inclusion of a source is not, however, an endorsement of it or any view(s) expressed.

Each piece of information is referenced in a footnote.

Full details of all sources cited and consulted in compiling the note are listed alphabetically in the bibliography.

Terms of reference

The ‘Terms of Reference’ (ToR) provides a broad outline of the issues relevant to the scope of this note and forms the basis for the country information.

The following topics were identified prior to drafting as relevant and on which research was undertaken:

- Actors in the conflict

- Areas of territorial control (ideally shown in maps/pictures), focussing on the situation post-Assad

- Areas where any fighting is taking place

- Intensity of fighting, incl. levels of violence – with a particular focus on impact on civilians

- Statistics showing deaths and injuries (where available)

- Statistics broken down by region/governorate/city (where possible).

Bibliography

Sources cited

ABC News

- Israel says it is conducting strikes in southern Syria, 25 February 2025. Accessed: 3 March 2025

Al Jazeera

-

Is Israel trying to entrench its occupation of the Golan Heights?, 16 December 2024. Accessed: 25 February 2025

-

Taking Syria: The opposition’s battles shown in 11 maps for 11 days, 8 December 2024. Accessed: 27 February 2025

-

What is behind US strategy of keeping troops in post-Assad Syria?, 6 January 2025

Arab Center Washington DC

-

About Arab Center Washington DC, no date. Accessed: 27 February 2025

-

Syria’s Transitional Government: Challenges, prospects, and global implications, 13 February 2025. Accessed: 27 February 2025

Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED)

-

About ACLED, no date. Accessed: 5 February 2025

-

Codebook, no date. Accessed: 5 February 2025

-

Data Export Tool, data downloaded 4 March 2025 (dataset available on request). Accessed: 4 March 2025

-

Fatalities, 7 May 2024. Accessed: 6 February 2025

BBC

-

‘We are still at war’: Syria’s Kurds battle Turkey months after Assad’s fall, 26 February 2025. Accessed: 26 February 2025

-

Why has the Syrian war lasted 12 years?, 2 May 2023. Accessed: 27 February 2025

BBC Monitoring

-

Briefing: Syria government and Kurdish-led SDF sign deal for ‘full integration’, 11 March 2025. Accessed: 12 March 2025

-

Explainer: Can IS capitalise on Syria’s instability?, 10 December 2024 (subscription only, copy on request). Accessed: 27 February 2025

-

Explainer: Key factions of the Turkey-backed Syria National Army coalition, 13 January 2025 (subscription only, copy on request). Accessed: 3 March 2025

-

Explainer: Which militant groups were involved in Syrian fighting?, 9 Dec 2024 (subscription only, copy on request). Accessed: 3 March 2025

-

Israel carries out wave of air strikes in southern Syria, 11 March 2025. Accessed: 12 March 2025

CNN

- Russian military has begun large-scale withdrawal from Syria, US and Western officials say, 16 December 2024. Accessed: 26 February 2025

Council on Foreign Relations (CFR)

-

About CFR, no date. Accessed: 25 February 2025

-

After Fall of Assad Dynasty, Syria’s Risky New Moment, 8 December 2024. Accessed: 25 February 2025

-

Will the Shake-up in Syria Undermine the Fight Against ISIS?, 9 January 2025. Accessed: 25 February 2025

German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP)

-

About SWP, no date. Accessed: 26 February 2025

-

The Fall of the Assad Regime: Regional and International Power Shifts, 25 February 2025. Accessed: 26 February 2025

The Guardian

-

Israel strikes Syria as Netanyahu approves plan to expand Golan Heights settlement, 15 December 2024. Accessed: 25 February 2025

-

Who are the main actors in the fall of the regime in Syria?, 9 December 2024. Accessed: 25 February 2025

Home Office

- Proscribed terrorist groups or organisations, updated 27 February 2025. Accessed: 31 March 2025

House of Commons Library

- Syria after Assad: Consequences and next steps in 2024/25, 19 December 2024. Accessed: 27 February 2025

Institute for the Study of War (ISW) and the American Enterprise Institute’s (AEI) Critical Threats Project (CTP)

-

Assessed Control of Terrain in Syria Shapefile Definitions, 28 February 2025

-

Interactive Map: Assessed Control of Terrain in Syria, 28 February 2025. Accessed: 4 March 2025

Institute for National Security Studies (INSS)

-

Despite efforts to remain in Syria, Russia is losing its status as an important security actor in the middle east, 27 January 2025. Accessed: 26 February 2025

-

Vision and mission, no date. Accessed: 26 February 2025

Italian Institute for International Political Studies

-

About the Institute, no date. Accessed: 23 January 2025

-

The End of Assad: A New Chapter in Syrian History, 8 December 2024. Accessed: 9 January 2025

The Kurdish Project

- YPJ: Women’s Protection Units, no date. Accessed: 26 February 2025

Middle East Forum

- ISIS Is Filling the Vacuum in Syria, 23 February 2025. Accessed: 4 March 2025

The New Arab

-

Syria’s Ahmed Al-Sharaa says rebel factions will be ‘disbanded’ in meeting with Druze, 17 December 2024. Accessed: 27 February 2025

-

Why fighting is raging in north Syria between the Turkish-backed SNA and Kurdish-led SDF, 21 January 2025. Accessed: 25 February 2025

The Observer

- ‘Woman, life, freedom’: the Syrian feminists who forged a new world in a land of war, 9 February 2025. Accessed: 25 February 2025

Reuters

- Syria: who are the main rebel groups?, 8 December 2024. Accessed: 25 February 2025

Syria Justice and Accountability Centre (SJAC)

-

About, no date

-

New Government-Controlled Areas, 22 January 2025. Accessed: 4 March 2025

-

Regions of control, 22 January 2025. Accessed: 18 February 2025

Syrian Democratic Council (SDC)

- We call for a democratic Syria, 27 January 2025. Accessed: 25 February 2025

Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR)

-

About Us, no date. Accessed: 4 February 2025

-

Monthly report (civilian deaths) [December 2023], 1 January 2024. Accessed: 5 February 2025

-

Monthly report (civilian deaths) [September 2024], 1 October 2024. Accessed: 5 February 2025

-

Monthly report (civilian deaths) [October 2024], 1 November 2024. Accessed: 5 February 2025

-

Monthly report (civilian deaths) [November 2024], 1 December 2024. Accessed: 5 February 2025

-

Monthly report (civilian deaths) [December 2024], 2 January 2025. Accessed: 5 February 2025

-

Monthly report (civilian deaths) [January 2025], 1 February 2025. Accessed: 5 February 2025

-

Monthly report (civilian deaths) [February 2025], 1 March 2025. Accessed: 3 March 2025

Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR)

-

About us, no date. Accessed: 26 February 2025

-

Since fall of Al-Assad’s regime Nearly 500 Israeli airstrikes destroy the remaining weapons of army of future Syria, 18 December 2024. Accessed: 26 February 2025

Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy (TIMEP)

-

About us, no date. Accessed: 23 January 2025

-

A Post-Assad Syria: Navigating the Transition Ahead, 19 December 2024. Accessed: 9 January 2025

United Nations (UN)

- Syrian Arab Republic, 1 August 2022. Accessed: 25 February 2025

U.S. Central Command

- Defeat ISIS mission in Iraq and Syria for January to June 2024, July 16 2024. Accessed: 27 February 2025

U.S. Department of Defense

-

DOD Announces 2,000 Troops in Syria, Department Prepared for Government Shutdown, 19 December 2024

-

DOD’s mission to defeat ISIS remains ongoing in Syria, 9 December 2024. Accessed: 26 February 2025

USA GOV

- U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM), no date. Accessed: 27 February 2025

Voice of America (VoA)

- New details emerge on Israel’s actions in Syrian buffer zone, change in US position, 18 December 2024. Accessed: 25 February 2025

Sources consulted but not cited

Hudson Institute, Remaining, Waiting for Expansion (Again): The Islamic State’s Operations in Iraq and Syria, 5 December 2024. Accessed: 27 February 2025

The Washington Institute, Syria Crisis Leaves Islamic State Prisons and Detention Camps Vulnerable, 9 December 2024. Accessed: 27 February 2025

Version control and feedback

Clearance

Below is information on when this note was cleared:

- version 2.0

- valid from 14 July 2025

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information in this section has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

Changes from last version of this note

First version since the fall of the Al-Assad regime.

Feedback to the Home Office

Our goal is to provide accurate, reliable and up-to-date COI and clear guidance. We welcome feedback on how to improve our products. If you would like to comment on this note, please email the cipu@homeoffice.gov.uk.

Independent Advisory Group on Country Information

The Independent Advisory Group on Country Information (IAGCI) was set up in March 2009 by the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration to support them in reviewing the efficiency, effectiveness and consistency of approach of COI produced by the Home Office.

The IAGCI welcomes feedback on the Home Office’s COI material. It is not the function of the IAGCI to endorse any Home Office material, procedures or policy. The IAGCI may be contacted at:

Independent Advisory Group on Country Information

Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration

1st Floor

Clive House

70 Petty France

London

SW1H 9EX

Email: chiefinspector@icibi.gov.uk

Information about the IAGCI’s work and a list of the documents which have been reviewed by the IAGCI can be found on the Independent Chief Inspector’s pages of the GOV.UK website.

-

BBC, Why has the Syrian war lasted 12 years?, 2 May 2023 ↩

-

HoC Library, Syria after Assad… (pages 8 to 9), 19 December 2024 ↩

-

UN, Syrian Arab Republic, 1 August 2022 ↩

-

Syria Population Task Force, Population Data, June 2024 (available by request from the HDX) ↩

-

Home Office, Proscribed terrorist groups or organisations, updated 27 February 2025 ↩

-

Reuters, Syria: who are the main rebel groups?, 8 December 2024 ↩

-

ISPI, The End of Assad: A New Chapter in Syrian History, 8 December 2024 ↩

-

The New Arab, Syria’s Ahmed Al-Sharaa says rebel factions will be ‘disbanded’…, 17 Dec 2024 ↩

-

TIMEP, A Post-Assad Syria: Navigating the Transition Ahead, 19 December 2024 ↩

-

Arab Center Washington DC, About Arab Center Washington DC, no date ↩

-

Arab Center Washington DC, Syria’s Transitional Government…, 13 February 2025 ↩

-

Reuters, Syria: who are the main rebel groups?, 8 December 2024 ↩

-

TIMEP, A Post-Assad Syria: Navigating the Transition Ahead, 19 December 2024 ↩

-

BBC Monitoring, Explainer: Key factions of the Turkey-backed SNA coalition, 13 January 2025 ↩

-

BBC Monitoring, Explainer: Key factions of the Turkey-backed SNA coalition, 13 January 2025 ↩

-

SDC, We call for a democratic Syria, 27 January 2025 ↩

-

The Guardian, Who are the main actors in the fall of the regime in Syria?, 9 December 2024 ↩

-

The Kurdish Project, YPJ: Women’s Protection Units, no date ↩

-

The Observer, ‘Woman, life, freedom’: the Syrian feminists who forged…, 9 February 2025 ↩

-

TIMEP, A Post-Assad Syria: Navigating the Transition Ahead, 19 December 2024 ↩

-

Al Jazeera, What is behind US strategy of keeping troops in post-Assad Syria?, 6 January 2025 ↩

-

The New Arab, Why fighting is raging in north Syria…, 21 January 2025 ↩

-

BBC Monitoring, Briefing: Syria government and Kurdish-led SDF sign deal…, 11 March 2025 ↩

-

Home Office, Proscribed terrorist groups or organisations, updated 27 February 2025 ↩

-

USA GOV, U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM), no date ↩

-

U.S. Central Command, Defeat ISIS mission in Iraq and Syria…, July 16 2024 ↩

-

BBC Monitoring, Explainer: Can IS capitalise on Syria’s instability?, 10 December 2024 ↩

-

CFR, Will the Shake-up in Syria Undermine the Fight Against ISIS?, 9 January 2025 ↩

-

BBC, ‘We are still at war’: Syria’s Kurds battle Turkey months after Assad’s fall, 26 February 2025 ↩

-

Middle East Forum, ISIS Is Filling the Vacuum in Syria, 23 February 2025 ↩

-

The Guardian, Who are the main actors in the fall of the regime in Syria?, 9 December 2024 ↩

-

TIMEP, A Post-Assad Syria: Navigating the Transition Ahead, 19 December 2024 ↩

-

Al Jazeera, Is Israel trying to entrench its occupation of the Golan Heights?, 16 December 2024 ↩

-

VoA, New details emerge on Israel’s actions in Syrian buffer zone…, 18 December 2024 ↩

-

SOHR, Since fall of Al-Assad’s regime Nearly 500 Israeli airstrikes…, 18 December 2024 ↩

-

ABC News, Israel says it is conducting strikes in southern Syria, 25 February 2025 ↩

-

BBC Monitoring, Israel carries out wave of air strikes in southern Syria, 11 March 2025 ↩

-

U.S. Dept of Defense, DOD’s mission to defeat ISIS remains ongoing in Syria, 9 December 2024 ↩

-

U.S. Department of Defense, DOD Announces 2,000 Troops in Syria…, 19 December 2024 ↩

-

CFR, Will the Shake-up in Syria Undermine the Fight Against ISIS?, 9 January 2025 ↩

-

CNN, Russian military has begun large-scale withdrawal from Syria…, 16 December 2024 ↩

-

INSS, Vision and mission, no date ↩

-

INSS, Despite efforts to remain in Syria, Russia is losing its status…, 27 January 2025 ↩

-

SWP, The Fall of the Assad Regime: Regional and International Power Shifts, 25 February 2025 ↩

-

Al Jazeera, Taking Syria: The opposition’s battles shown in 11 maps for 11 days, 8 December 2024 ↩

-

ISPI, The End of Assad: A New Chapter in Syrian History, 8 December 2024 ↩

-

SJAC, New Government-Controlled Areas, 22 January 2025 ↩

-

SJAC, Regions of control, 22 January 2025 ↩

-

ISW & AEI, Interactive Map: Assessed Control of Terrain in Syria, 28 February 2025 ↩

-

ISW & AEI, Assessed Control of Terrain in Syria Shapefile Definitions, 28 February 2025 ↩

-

CFR, Will the Shake-up in Syria Undermine the Fight Against ISIS?, 9 January 2025 ↩

-

SNHR, Monthly report (civilian deaths) [January 2025], 1 February 2025 ↩

-

SNHR, Monthly report (civilian deaths) [February 2025] (page 1), 1 March 2025 ↩

-

SNHR, Monthly report (civilian deaths) [February 2025] (page 4), 1 March 2025 ↩

-

ACLED, About ACLED, no date ↩

-

(https://acleddata.com/acleddatanew/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2024/10/ACLED-Codebook-2024-7-Oct.-2024.pdf) (page 18), no date ↩

-

ACLED, Data Export Tool, data downloaded 4 March 2025 ↩

-

ACLED, Fatalities, 7 May 2024 ↩

-

ACLED, Fatalities, 7 May 2024 ↩

-

ACLED, Data Export Tool, data downloaded 4 March 2025 ↩

-

ACLED, Data Export Tool, data downloaded 4 March 2025 ↩

-

SNHR, Monthly report (civilian deaths) [February 2025] (page 2), 1 March 2025 ↩

-

SNHR, Monthly report (civilian deaths) [September 2024], 1 October 2024 ↩

-

SNHR, Monthly report (civilian deaths) [October 2024], 1 November 2024 ↩

-

SNHR, Monthly report (civilian deaths) [November 2024], 1 December 2024 ↩

-

SNHR, Monthly report (civilian deaths) [December 2024], 2 January 2025 ↩

-

SNHR, Monthly report (civilian deaths) [January 2025], 1 February 2025 ↩

-

SNHR, Monthly report (civilian deaths) [February 2025], 1 March 2025 ↩

-

SNHR, Monthly report (civilian deaths), various dates ↩

-

ACLED, Data Export Tool, data downloaded 4 March 2025 ↩

-

ACLED, Data Export Tool, data downloaded 4 March 2025 ↩

-