Stopping the start: our new plan to create a smokefree generation

Updated 8 November 2023

Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care by Command of His Majesty.

October 2023

CP 949-I

ISBN: 978-1-5286-4439-6

Foreword

Smoking damages and cuts short lives in extraordinary numbers. From increasing stillbirths, through asthma in children, to dementia, stroke and heart failure in old age, it causes disability and death throughout the life course. It drives many cancers, especially lung cancer which is the most common cause of cancer deaths in both women and men in the UK. It causes and accelerates heart disease, the biggest single cause of deaths overall. Large numbers of people are confined to their homes by heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease caused by smoking, unable even to climb the stairs. Non-smokers, including children and pregnant women are exposed to the risks of second-hand passive smoking. The NHS has a huge burden of smoking-related disease to attend to, along with all its other work.

Data over the last 5 years shows most smokers want to quit, but cannot due to an addiction to nicotine that started in their teenage years. Over 80% of smokers started before they turned 20, many as children. They have had their choices taken away by addiction, and their lives will be harmed and cut short by an addiction they do not want.

One of the tools to help people addicted to nicotine to stop smoking is vaping - and because the harms of smoking are so great, it is safer to vape than smoke, but vapes are not risk free. So, if you smoke, swap to vaping, if you don’t smoke, don’t vape. Marketing vapes to children is utterly unacceptable. Some are now clearly trying to addict children including with colours, flavours, cartoons and other marketing methods aiming to tempt children towards addiction.

The government has made clear they wish to create a smokefree generation unaffected by the extraordinary harms of addiction-driven smoking, and tackle youth vaping. This Command Paper lays out a route to prevent addiction to smoking before it starts, to support smokers to quit and to stop vapes being marketed to children.

Professor Sir Chris Whitty, Chief Medical Officer for England

Smoking kills, places a huge burden on the NHS and costs the economy billions every year in lost productivity. We need to do more to protect our children and grandchildren from the many health problems it causes, including cancer and cardiovascular disease, and to help them live longer, healthier lives. We know that most smokers start in their youth and are then addicted for life. Vaping can be an effective tool in helping smokers to quit, but we have seen a recent and highly concerning surge in the number of children vaping

By taking action now, we are helping smokers across the country to quit through our new programme of stop smoking support, reducing the appeal and availability of vapes to young people, and taking a big step towards a smokefree generation which will help build a better future for our children.

The Rt Hon Steve Barclay MP, Secretary of State for Health and Social Care

Executive summary

Tobacco is the single most important entirely preventable cause of ill health, disability and death in this country, responsible for 64,000 deaths in England a year. No other consumer product kills up to two-thirds of its users. The independent review in 2022 found that, if we do not act, nearly half a million more people will die from smoking by 2030.

… when used exactly as recommended by the manufacturer, cigarettes are the one legal consumer product that will kill most users…

The Khan review: making smoking obsolete (2022)

Smoking causes harm throughout people’s lives. It is a major risk factor for poor maternal and infant outcomes, significantly increasing the chance of stillbirth and can trigger asthma in children. It leads to people needing care and support on average a decade earlier than they would have otherwise, often while still of working age. Smokers lose an average of ten years of life expectancy, or around one year for every 4 smoking years.

Smoking causes around 1 in 4 of all UK cancer deaths and is responsible for the great majority of lung cancer cases. Smoking is also a major cause of premature heart disease, stroke and heart failure and increases the risk of dementia in the elderly. Non-smokers are exposed to second-hand smoke (passive smoking) which means that through no choice of their own many come to harm - in particular children, pregnant women, and their babies.

The tobacco epidemic is one of the biggest public health threats the world has ever faced… All forms of tobacco use are harmful, and there is no safe level of exposure to tobacco.

World Health Organization (2020)

As a result, smoking puts significant pressure on the NHS. Almost every minute of every day someone is admitted to hospital because of smoking, and up to 75,000 GP appointments could be attributed to smoking each month - equivalent to over 100 appointments every hour.

Those who are unemployed, on low incomes or living in areas of deprivation are far more likely to smoke than the general population. Smoking attributable mortality rates are 2.1 times higher in the most deprived local authorities than in the least deprived.

It is estimated that the total costs of smoking in England are over £17 billion. This includes an annual £14 billion loss to productivity, through smoking related lost earnings, unemployment, and early death, as well as costs to the NHS and social care of £3 billion.

Most smokers know about these risks and, because of them, want to quit - but the addictive nature of cigarettes means they cannot. Three-quarters of current smokers would never have started if they had the choice again and on average it takes around 30 quit attempts to succeed. The majority of smokers start in their youth and are then addicted for life. More than 4 in 5 smokers start before the age of 20. In short, it is much easier to prevent people from starting smoking in the first place.

Over the last 30 years, governments have taken decisive action to reduce smoking rates, saving thousands of lives as a result. There is strong public support for action: 77% of adults in England support government action to limit smoking or think the government should do more. The government now wants to take the final step and end smoking in this country for good.

The government is creating the first smokefree generation, by bringing forward legislation so that children turning 14 this year or younger will never be legally sold tobacco products. This will prevent future generations from ever taking up smoking, as there is no safe age to smoke.

To support existing smokers to quit, the government is more than doubling the budget for stop smoking services, investing an additional £70 million per year (to a total of £138 million), aiming to support around 360,000 people to quit each year. We are providing funding (£5 million this year, £15 million thereafter) for new national campaigns to explain the legal changes, the benefits of quitting and the support available. The government will ensure the law is enforced by providing an additional £30 million a year for enforcement agencies and introducing on the spot fines for underage sales of tobacco products and vapes.

Vapes are substantially less harmful than smoking because they do not contain tobacco, and therefore can be an effective tool in supporting smoking cessation. Vaping is already estimated to contribute to an extra 50,000 to 70,000 smoking quits per year in England. Ensuring that vapes continue to be available to current adult smokers is vital to reducing smoking rates. That is why in April 2023, the government committed to support 1 million adult smokers to ‘Swap to Stop,’ which was the first scheme of its kind in the world.

However, the number of children using vapes has tripled in the past 3 years and a staggering 20.5% of children had tried vaping in March to April 2023. Due to nicotine content and the unknown long-term harms, vaping carries risk of harm and addiction for children. The health advice is clear: young people and those who have never smoked should not vape. We have a duty to protect our children from the potential harms associated with underage vaping, while their lungs and brains are still developing. Encouraging children to use a product designed for adults to quit smoking and then addicting them is not acceptable.

While selling nicotine vapes to under 18s is illegal, inherited EU regulations have led to a system where vapes are routinely promoted and marketed to children and young people at scale. Major economies such as the USA, Australia and Canada are taking action to tackle sharp increases in youth vaping, and we risk becoming an outlier if we do not keep pace. Learning from other countries and our recent call for evidence, the government is therefore looking at measures to reduce the appeal and availability of vapes to children.

Chapter overview

This paper sets out ambitious proposals to prohibit the sale of tobacco products for future generations, a wider package of measures to support current smokers to quit alongside action to curb the rise in youth vaping.

Chapter 1 begins by setting out a clear case for change. The harms caused by smoking and second-hand smoke are well documented, but the chapter also considers the more recent evidence on the harms of child and youth vaping and international comparisons.

Chapter 2 summarises action already underway on smoking and vaping, including the success of previous legislative changes to bring down smoking rates and reduce the appeal of smoking to young people.

Drawing on the recommendations from the independent review, Chapter 3 proposes legislation so that children turning 14 this year or younger will never be legally sold tobacco products, as introduced by New Zealand last year, which attracted significant public support. This does not criminalise smoking, and the phased approach means that anyone who can legally be sold tobacco products now will never be prevented from doing so today or in future.

While the government wants to stop people from starting to smoke in the first place, most smokers want to quit. Chapter 4 sets out further action the government will take to support smokers to quit, including more than doubling the existing budget for local stop smoking services. Someone quitting before turning 30 could add 10 years to their life and if a smoker can quit smoking for 28 days, they are 5 times more likely to quit permanently. In addition, the government will provide further funding for national campaigns, roll out the new ‘Swap to Stop’ scheme - the first of its kind in the world - and provide financial incentives for pregnant smokers to quit.

Chapter 5 sets out the legislative proposals the government is considering to curb the rise in youth vaping. These will need to balance having the biggest impact on youth vaping with ensuring vapes continue to support adult smokers to quit. The proposals include restricting flavours, regulating point of sale displays, regulating packaging and presentation, considering restricting the sale of disposable vapes, and closing loopholes in the law on free samples and non-nicotine vapes. The government will consult on measures this month.

Chapter 6 sets out the approach to enforcement to ensure that the above measures deliver lasting change. This includes new funding for enforcement agencies to implement and enforce the proposed rules, introducing on-the-spot fines for rogue retailers who commit underage sales, and further steps to enhance online age verification so that age of sale law is enforced across both online and face-to-face sales.

Chapter 7 sets out the next steps more generally. Later this month, the government will launch a consultation on the smokefree generation policy detailed in this paper and its scope, as well as on the measures to curb the rise in youth vaping. Following consultation, the government will bring forward legislation as soon as the parliamentary timetable allows.

Territorial extent

Health policy is a devolved matter in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. However, the UK government is committed to working closely with the devolved administrations as we develop these proposals, with a view to aligning policy approaches wherever this would improve outcomes - continuing ongoing collective action to tackle the harms caused by smoking and youth vaping across all parts of the UK.

1. The case for change

Overview

This chapter sets out the case for taking further action to finish the job on preventing people becoming addicted to smoking, while also addressing the more recent challenge of youth vaping.

Tobacco, and especially cigarette smoking, is the single biggest entirely preventable cause of ill health, death and disability in this country. Stopping people from ever starting smoking, as well as supporting current smokers to quit, will improve public health and reduce disparities, reduce the burden on the NHS and the social care system, and provide substantial benefits to the workforce and the economy.

Smoking prevalence and age of initiation

The government is committed to reducing the harms of smoking and has a strong history of taking bold and comprehensive action on tobacco control. Smoking rates in the UK are now the lowest on record, at 12.9% (around 6.4 million people) and 12.7% smoke in England.

Smoking prevalence is a third of its height in 1974, and has fallen by more than a third over the last decade. We have successfully seen smoking rates decline in all ages since the 1970s, with the largest reduction among 18 to 24 year olds: 25% of this group smoked in 2011 compared with 11.6% in 2022.

Legislation has been an important driver of this decline - including raising the age of sale for smoking from 16 to 18, which reduced prevalence in this age group by 30%.

The great majority of initiation of cigarette use continues to be in the teenage years. 83% of smokers start before the age of 20. People who start smoking under the age of 18 have higher levels of nicotine dependence compared to those starting over 21 and are less likely to make a quit attempt and successfully quit.

The impact of smoking on public health

Figure 1 shows that tobacco is the single leading preventable cause of mortality, leading to 64,000 deaths in England each year and harming nearly every organ of the body.

Smoking is causing a hidden national health crisis. Estimates suggest there have been as many - if not more - deaths from smoking as from COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic. Up to two-thirds of smokers die of smoking, and those who start smoking as a young adult lose an average of 10 years of life expectancy.

Figure 1: Age-standardised mortality attributed to risk factors, England, 2019

Source: Global Burden of Disease Study 2019

Smoking causes around 1 in 4 of all UK cancer deaths. Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer deaths in the UK, and most people who are diagnosed with this condition die within a year. Of the estimated 54,500 total new lung cancer cases in the UK in 2023, 43,000 were preventable. Tobacco is responsible for just over 70% of all lung cancer cases, or equivalent to over 39,300 cases. Smoking also contributes significantly to cancers of the mouth, throat, oesophagus, stomach, bowel, pancreas and bladder.

Lung health in general is also severely impaired by smoking, leading to disabilities, including the 9 out of 10 cases of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) thought to be caused by smoking. Smoking, including passive smoking, can increase the risk of asthma in children and adults.

Smoking substantially increases the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) - heart attacks and strokes - one of the most common causes of mortality in the UK. Between 2017 and 2019, around 28,000 deaths from heart disease were attributable to smoking. Smoking increases the rates of stroke by around 12% for every 5 cigarettes a day.

Smoking is also a significant risk for poor pregnancy-associated health outcomes. Women who smoked during pregnancy were 2.6 times more likely to give birth prematurely. These babies were more likely to have a lower birth weight and were 4.1 times more likely to be small-for-date babies. Smoking increases the risk of birth defects which can result in poorer health outcomes later in life. In areas with the highest smoking rates, in high income countries, up to 20% of stillbirths may be caused by smoking.

Smoking is closely associated with poor mental health and wellbeing. People with mental health conditions die 10 to 20 years earlier with smoking contributing significantly to this. Smokers are also 1.6 times more at risk of dementia, including Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia, and 14% of dementia cases can be attributed to smoking internationally.

Smoking and levelling up

There are wide health disparities, socioeconomic and geographical, in the UK. People in the least deprived areas of the UK can expect to live around a decade longer than people in the most deprived areas. In England, there is an almost 19 year gap in healthy life expectancy between the most and least affluent areas. People in the most deprived areas, or living in relative deprivation, get multiple long-term health conditions 10 to 15 years earlier than in the least deprived areas, and spend more years in ill health.

CVD is one of the largest contributors to health disparities. People living in the most deprived areas of England are almost twice as likely to die prematurely from CVD than people in the least deprived areas.

Lung cancer deaths in England are more common in people living in the most deprived areas. According to NHS Digital’s cancer registration data, mortality rates for lung cancer in 2020 were almost 3 times higher for people living in the most deprived areas compared to the least deprived areas. For males, the rate was 103 deaths per 100,000 living in the most deprived areas compared to 37 per 100,000 people living in the least deprived areas. For females, the rate was 78 per 100,000 people living in the most deprived areas, compared to 26 per 100,000 people living in the least deprived areas.

COPD limits people’s quality of life, leads to multiple NHS interactions and is much more common in areas of deprivation. Someone from the most deprived 10% of households is more than 2.5 times more likely to have COPD than someone from the least deprived households. Many other smoking-related diseases are more common in deprived areas.

Smoking is also a significant driver of stillbirth. Stillbirth rates increase with socioeconomic deprivation, from 4.9 per 1,000 in the most deprived decile to 3.0 per 1,000 in the least deprived.

Smoking and health disparities

Smoking is one of the most important preventable causes of disparities in health and a significant contributor to the gap in life expectancy. For some conditions, such as lung cancer and severe COPD, smoking is the main driver and for others, such as premature CVD, smoking is a major factor. Reducing smoking rates is therefore one of the biggest single health interventions that we can make to level up the nation.

Figure 2 shows that mortality rates attributed to smoking are 2.1 times higher in the most deprived local authorities than in least deprived local authorities, where more people become addicted when young.

Smoking prevalence is much higher in people on lower incomes, unemployed or those experiencing homelessness. The major risks of smoking occur in every ethnic group.

Deprived areas are more likely to have lower healthy life expectancy and higher smoking rates. In the least deprived local authority, healthy life expectancy for females is 71 years and smoking prevalence is 2.5%, whereas in the most deprived local authority, healthy life expectancy for females is 17 years lower, at 54 years, and smoking prevalence is over 7 times higher at 19.1%, according to the Public Health Outcomes Framework.

Figure 2: Smoking attributable mortality by deprivation, England, 2017 to 2019

Source: Local tobacco control profiles

NHS pressures from smoking-related diseases are especially high in areas of deprivation. Figure 3 shows smoking attributable hospital admissions by deprivation and demonstrates that smoking-related morbidity and NHS activity is concentrated in areas of relative deprivation. It shows that the number of smoking attributable hospital admissions per 100,000 is double in the most deprived decile compared to the least deprived.

Figure 3: Smoking attributable hospital admissions by deprivation, England, 2019 to 2020

Source: Local tobacco control profiles

Smoking in pregnancy

Rates of smoking in pregnancy, which has many risks for the baby, change with age, socioeconomic and geographical disparities. On average, 1 in 11 of all mothers smoked at the time of delivery in 2022 to 2023, however this is as high as 1 in 5 in some parts of the country. In 2021 to 2022, 21.1% of pregnant women in the most deprived area smoked at time of delivery, compared to 5.6% in the least deprived area.

Figure 4 shows that 24% of pregnant women who live in the most deprived decile smoke during early pregnancy compared to 4.3% in the least deprived.

Pregnant women living in areas where there is high smoking prevalence are also more likely to be exposed to passive smoking via second-hand smoke. This leads to babies having smoking-related adverse birth outcomes.

Based on Local tobacco control profiles from 2018 to 2019, the highest prevalence of smoking in pregnancy is in the under 18 age range, at 31.8%, and the second highest prevalence, 31.2%, is for the 18 to 19 year old age range. This means that almost a third of teenage mothers smoked during pregnancy. This compares to 7.2% among 35 to 39 year olds, and 7.3% among 40 to 44 year olds.

Figure 4: Smoking rates in early pregnancy by deprivation, England, 2018 to 2019

Source: Local tobacco control profiles

Other groups

According to Local tobacco control profiles, smoking prevalence in people who have routine and manual occupations in 2022 was 22.5% and the odds of being a current smoker in this group is 2.24 times higher than being a current smoker in other occupational groups. In 2022, 20.1% of unemployed adults in England were current smokers, compared with 12.7% of employed adults.

Impact of smoking on income

Based on 2022 estimates, the average smoker spends around £47 a week on tobacco, which is around £2,450 a year, according to the Ready Reckoner tool created by Action on Smoking and Health (ASH). On average, stopping smoking would have increased disposable incomes by 9% in 2019, ranging from 6.4% in London to 11.4% in the North East.

The cost of smoking to the NHS

Smoking places a significant burden on the NHS. It is estimated that in 2019 to 2020, 448,031 NHS hospital admissions were attributable to smoking.

Smoking increases multimorbidity (many diseases at once) and can cause particularly complex disease states, requiring multiple hospital and GP attendances. Analysis suggests almost every minute of every day someone is admitted to hospital because of smoking, and up to 75,000 GP appointments could be attributed to smoking each month - equivalent to over 100 appointments every hour.

Smoking also increases the burden on social care. Smokers need care on average 10 years earlier than they would otherwise have - often while still of working age.

There is evidence that previous legislation on tobacco has reduced smoking-related pressures on the NHS: the smokefree (ban in public places) legislation in 2007 led to a reduction in emergency admissions in England, including a reduction in the incidence of acute coronary events and reduced admissions for childhood asthma.

The economic cost of smoking

In 2016, the High Court, based on a 2010 report from Policy Exchange, said that the economic costs of tobacco use to society were in the region of £13.74 billion per year. ASH now estimates that the total costs of smoking in England are over £17 billion. This includes a £14 billion loss to productivity per year through smoking related lost earnings, unemployment, and early death, as well as costs to the NHS and social care sector of £1.9 billion and £1.1 billion respectively.

The impact that smoking has on productivity varies across the country. ASH estimates that smoking causes a £897 million productivity loss in Greater Manchester, compared to a £191 million loss in Cambridge and Peterborough.

Smoking can stop people from thriving within the labour market. ASH’s Smoking, employability, and earnings report shows that being a smoker is associated with a 7.5% lower probability of being employed and about £1,424 lower earnings a year. Quitting may help mitigate this - ex-smokers are 5% more likely to be employed than current smokers.

The illnesses smoking causes lower an individual’s productivity and shorten their working lives. Smokers have an absenteeism rate 33% higher than non-smokers and take an extra 2.7 sick days per year. For an 18 year old joining the workforce today, this represents an additional 4.5 months off sick over the course of their working lives.

Each lung cancer case, just over 70% of which are caused by tobacco, costs society £360,000 from lost productivity through additional morbidity and mortality.

Vaping as a cessation tool

The latest evidence found that in the short and medium term, vaping poses a small fraction of the risks of smoking, because vapes do not contain tobacco. Vaping can therefore provide a less harmful alternative for an adult smoker by giving the person the nicotine they crave through heating e-liquid but creating fewer toxins and at lower levels.

Recent evidence shows that, for many adult smokers, vapes are an effective tool in supporting smoking cessation, especially when combined with expert support. It found that adverse events from vapes are rare, as rare as for nicotine replacement therapy. Vaping is already estimated to contribute to an extra 50,000 to 70,000 smoking quits per year in England. Ensuring vapes continue to be made available to current smokers is vital to reducing smoking rates.

That is why in April 2023, the government committed to support 1 million adult smokers to ‘Swap to Stop’, swapping cigarettes for vapes under a new national scheme, the first of its kind in the world.

The rise in youth vaping

Vaping is never recommended for children and carries risk of future harm and addiction. The health advice is clear: young people and those who have never smoked should not vape or be encouraged to vape.

Selling nicotine vapes to children (under 18) is an offence. Despite this, the number of children vaping has risen sharply over the past few years. ASH analysis showed that in 2023, 20.5% of children (aged between 11 and 17) had tried vaping, up from 15.8% in 2022, and 13.9% in 2020 before the first COVID-19 lockdown.

As with other health risk behaviours, experimentation and prevalence is higher among older children. According to NHS Digital’s report Smoking, drinking and drug use among younger people in England 2021, 1% of 11 year olds were current vape users, compared with 18% of 15 year olds. This lower rate in younger children has been the case since data collection began in 2014. However, in 2021, there were larger increases in current use for those aged 14 and 15 compared to younger age groups.

Similarly, ASH found that current vaping prevalence among 16 to 17 year olds increased from 5% in 2018 to 15% in 2023. The data from 2023 found that of the 11 to 17 year olds who had tried vaping, almost half had never smoked a cigarette.

Figure 5 shows the current vaping prevalence among 11 to 15 year olds by age, between 2014 and 2021. Prevalence was highest, and saw large increases between 2018 and 2021, for those aged 14 and 15. Current vaping prevalence among 12 to 14 year olds ranged from between 2% and 6% in 2014 to between 3% and 11% in 2021.

Figure 5: Current vaping prevalence by age, England, 2014 to 2021

Source: Smoking, drinking and drug use among young people in England, 2021

NHS Digital’s report Smoking, drinking and drug use among young people in England 2021 showed a recent doubling of regular vape use for 11 to 15 year olds, from 2% in 2018 to 4% in 2021. Regular users were those who used vapes at least once a week. Current use, which includes regular users and occasional users who used vapes less than once a week, also increased. The government does not want these increases to continue.

More 11 to 15 year olds are now starting vaping than starting smoking. Figure 6 shows that the percentage of 11 to 15 year olds vaping in 2021 was triple those who were smoking.

Figure 6: 11 to 15 year olds that are current smokers and vape users

Source: Smoking, drinking and drug use among young people in England, 2021

Health risks associated with youth vaping

Vaping should only be to help people stop smoking because the harms of smoking are so great. Vapes should never be used by children.

The active ingredient in most vapes (apart from nicotine-free vapes) is nicotine which, when inhaled, is a highly addictive drug. The addictive nature of nicotine means that a user can become dependent on vapes, especially if they use them regularly.

Giving up nicotine can be very difficult because the body has to get used to functioning without it. Withdrawal symptoms can include cravings, irritability, anxiety, trouble concentrating, headaches and other mental and physical symptoms. Nearly half of nicotine users want to quit but cannot. Evidence suggests that in adolescence, the brain is more sensitive to the effects of nicotine, so there could be additional risks for young people than for adults.

There are also some health risks associated with the other ingredients in vapes. For example, propylene glycol and glycerine (components of e-liquids) can produce toxic compounds if they are overheated. The long-term health harms of colours and flavours when inhaled are unknown, but they are certainly very unlikely to be beneficial.

While the majority of vapes are covered under our regulations, research by the Chartered Trading Standards Institute shows that some vapes on sale are illegal and do not meet the UK’s quality and safety regulations. These illegal products can often be dangerous and harmful and carry much greater risk than legal vapes. Recent reports have shown that unsafe and illegal vapes can contain dangerous chemicals like lead and nickel. High levels of inhaled lead damages children’s central nervous system and brain development.

There is considerable debate about the scale and nature of long-term vaping harms. Not all the risks from vapes have been fully investigated, including inhaling additives for flavours, and the long-term effects of vaping are yet unknown, although further evidence will emerge in the future.

Tobacco and vaping internationally

Tobacco use is the world’s single most preventable cause of death and disease. Countries around the world have adopted different approaches to tobacco control, reflecting the unique cultural, social and economic contexts in which they operate.

Some countries, such as the USA in 2019, Sri Lanka in 2006 and Uganda in 2015, have moved to 21 years as the age of sale for tobacco products. Singapore progressively raised the age at which individuals could buy cigarettes from 18 to 21 between 2018 and 2021, with recent discussions to increase this further.

More countries are looking to raise the age of sale to prohibit the next generation from smoking, including New Zealand, which is covered in the case study. Malaysia introduced a bill in June 2023 that would prohibit smoking for anyone born on or after 1 January 2007. Canada has taken a wider approach to tackle tobacco use, focusing on reducing the availability and promotion of tobacco products. Canada was one of the first countries to adopt picture warnings on the outside of cigarette packets and introduce pack inserts with quit messaging information.

Youth vaping is also becoming a global issue, with countries around the world experiencing increases in vaping use among their younger populations. Countries reporting a two-fold or greater increase include Australia, Italy, Germany, and France. In the USA in 2022, approximately 1 in 10 middle and high school students used vapes.

Many major economies such as the USA, Australia and Canada are taking action to tackle sharp increases in youth vaping, and we risk becoming an international outlier if we do not keep pace. Various measures have been taken, including prohibiting the sale of vapes or raising the age of sale, restricting the types of flavours and packaging designs and advertising restrictions or making vapes available on prescription only (as in Australia).

The USA has also introduced a strict pre-market authorisation for all new and current vapes, restricting vape flavours to tobacco and menthol only. The Food and Drug Administration in the USA assessed over 5 million applications and, as of March 2023, has only authorised 23 products and devices for sale.

Action on disposable vapes is being considered internationally, as these products particularly appeal to children. In 2023, France, Germany and Ireland have all taken steps to restrict the sale of disposable vapes due to the environmental impact and appeal of these products connected to the recent rise in youth vaping. Other countries have taken action to reduce the visibility and appeal of vapes - Canada has prohibited visible product display and vape advertising in shops. Denmark and Finland have both introduced standardising vape packaging and have prohibited all e-liquids with any characterising flavours.

Case study: New Zealand

In January 2023, New Zealand became the first country in the world to introduce a restriction on the sale of tobacco to anyone born after a specified date, as part of its Smokefree 2025 Action Plan. The legislation makes it an offence to sell smoked tobacco products to anyone born on or after 1 January 2009, to first take effect in January 2027.

This legislation accelerates progress towards a smokefree future. Future generations will never be able to legally purchase tobacco, because the truth is there is no safe age to start smoking. Thousands of people will live longer, healthier lives and the health system will be NZ$5 billion better off from not needing to treat the illnesses caused by smoking.

Health Minister, Dr Ayesha Verrall

Modelling of New Zealand’s policies shows a significant reduction in overall smoking rates (estimating that prohibiting the sale of tobacco to anyone born after 2009 could halve smoking rates within 10 to 15 years of implementation) and a steep narrowing of the smoking gap between Maori and non-Maori.

Similar to the UK, New Zealand has seen a significant increase in the number of children vaping. Figure 7 shows that current vaping among 15 to 17 year olds in New Zealand has tripled since 2019, rising from 3.5% to 12.3% in 2021.

In 2020, the New Zealand government introduced regulations on vapes to help limit youth use. They introduced an age of sale restriction to 18 and prohibited vaping advertisement and sponsorship. They also established a licensing scheme, permitting general retailers to sell only tobacco, menthol and mint flavours, with specialist vape retailers permitted to sell all flavours. In 2023, the government announced new policies to be introduced over the next 2 years to tackle youth vaping. This includes restrictions on flavour descriptions, prohibiting images of cartoons and toys on packaging and regulating single use vapes.

Figure 7: Current (at least monthly) and daily smoking and e-cigarette use among 15 to 17 year olds, 2011 to 2012 to 2020 to 2021 in New Zealand

Source: New Zealand Health Survey 2021 to 2022

2. Action already underway

Overview

A comprehensive approach to tobacco control has been critical to the success in reducing smoking rates including a history of legislation, funding to local stop smoking services, NHS tobacco dependence treatment services and impactful anti-smoking campaigns.

Tobacco legislation

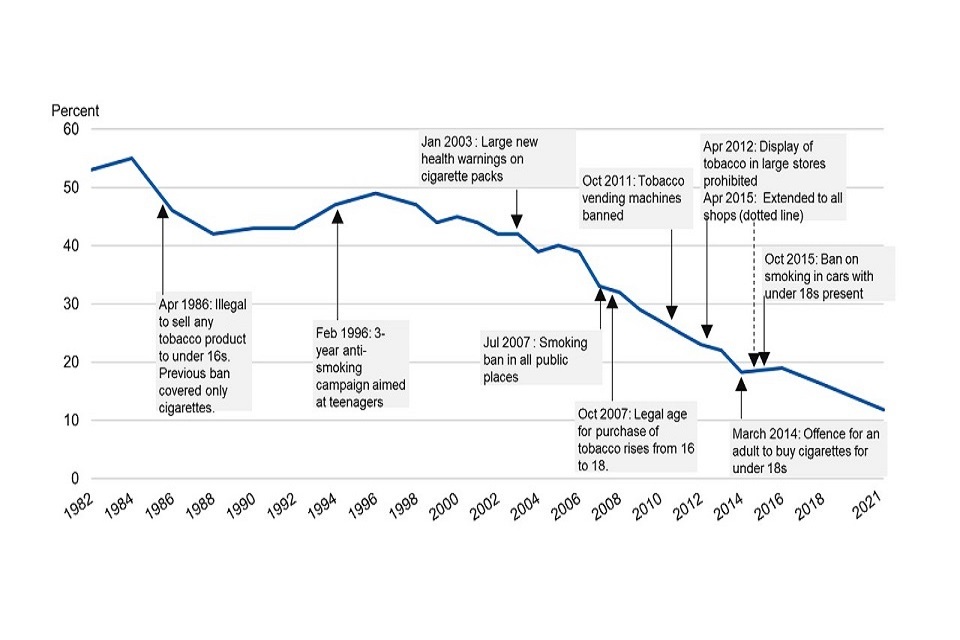

Legislative action has made long-lasting change, particularly legislation to discourage young people from taking up smoking. Figure 8 shows a consistent decrease in smoking rates alongside the legislation which has supported this.

Figure 8: Smoking prevalence mapped against key interventions from 1982 to 2021

Source: Smoking, drinking and drug use among young people in England, 2021

In 2007, the legal age of sale for tobacco products was raised from 16 to 18. This change was shown to reduce smoking among children with a similar impact among different socioeconomic groups. This helped reduce youth smoking rates in children aged 11 to 15 from 9% in 2005, to less than 1.1% in 2021. In 2008, the first time data was collected after the change in the law, 39% of pupils who smoked said they found it difficult to buy cigarettes from shops, an increase of 15 percentage points from 2006.

More recent changes include the introduction of standardised packaging in 2016 and prohibiting the sale of menthol flavoured cigarettes and hand rolling tobacco, which came into force in May 2020, as international evidence shows that many young people start smoking by using menthol cigarettes.

System wide action and funding

Last year alone, the government provided £35 million to deliver on the NHS Long Term Plan’s commitments on smoking. This funding will mean that all inpatients admitted to hospital who smoke will be offered NHS-funded tobacco treatment services. As part of the plan, all pregnant smokers will receive specialist opt-out support as part of a new maternity-led pathway. Routine carbon monoxide testing, which is used to identify smokers at booking and refer them into support to quit, has resulted in more pregnant smokers being identified and referred into stop smoking services.

In June 2023, the government announced a new national targeted lung cancer screening programme designed to catch cancer sooner. Smoking causes just over 70% of lung cancer cases, so people aged 55 to 74 with a history of smoking will be assessed and invited for screenings and directed to smoking cessation services. In August 2023, the government launched a consultation on introducing mandatory cigarette pack inserts with positive messages and information to help people to quit.

Making smoking obsolete - independent review

In 2022, the government launched an independent review into tobacco control policies, led by Dr Javed Khan OBE. Following extensive consultation, the review made recommendations to support the government’s target to be smokefree by 2030 (prevalence of 5% or less). The most ambitious was a proposal to raise the age of sale for tobacco year-on-year indefinitely, to ensure that future generations never start smoking. The review also recommended vaping to be offered as a substitution for smoking, alongside measures to reduce the appeal of vaping to children.

Vaping regulations

To date, government policy has been to facilitate 2 routes to market for vapes, the consumer and medicinal route. Currently, all products are supplied to market through the consumer route, as there is no medicinally licensed vaping product.

In 2016, the government introduced regulations to regulate vapes as consumer products, largely derived from EU law. The Tobacco and Related Products Regulations 2016 (TRPR) sets product standards for nicotine vapes including restrictions on maximum nicotine strength, refill bottle and tank size limits, packaging, and advertising (including prohibiting advertising on television and radio). As part of the compliance process for TRPR, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) has to be notified if a company wants to bring a vape on to the UK market. The MHRA has registered over 67,000 nicotine-containing vape products on the UK consumer market.

The inherited EU regulations do not support the government’s objective to promote vapes as a quit aid for adult smokers. Instead, the regulations have enabled a system where vapes are all too often promoted and marketed to children. This needs to change, which is why the government will look to introduce measures to reduce the appeal and availability of vapes to children. In the absence of an approved medicinal vape, the government is rolling out a new national vaping ‘Swap to Stop’ scheme to support a million smokers to quit.

The MHRA is ready to support a future medicinally-licensed vaping product, if the industry comes forward with a successful candidate. The MHRA continues to provide technical and scientific advice to companies interested in developing medicinal vapes.

The Tobacco Advertising and Promotion Act 2002 placed further restrictions on advertising and promotion of tobacco products. Working with the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA), the government has taken further steps to regulate the advertising of vapes. ASA recently issued an enforcement notice instructing vaping companies to comply with the UK Advertising Codes and remove any non-compliant advertisements for vaping products on social media. It is also undertaking proactive investigations into vaping advertisements on a range of social media platforms.

Under the Online Safety Bill, social media platforms will have a responsibility to ensure that children are protected from content which is harmful to them. Companies will have to put in place age-appropriate protections to protect children from user-generated content that encourages the inhalation of harmful substances.

Educating children about the risks of smoking and vaping

Primary and secondary school children are already educated on the harms of tobacco. In May 2023, the Prime Minister announced that the government will do more to teach children about the risks of vaping. The Department for Education has brought forward the review of the relationships, sex, and health education statutory guidance, and will include the risks of vapes in it.

The government has also published a new resource pack for schools on vaping for the start of the 2023 to 2024 academic year. These resources build on other content we have produced for young people on the FRANK and NHS Better Health websites, and input to educational resources produced by partners including the PSHE Association.

3. Smoking - stopping the start

Overview

There is no more addictive product that is legally sold in our shops than tobacco, which is why ‘stopping the start’ of addiction is vital. Three-quarters of smokers would never have started if they had the choice again. It is much easier never to start than to have to quit.

The great majority of smokers start as teenagers - 83% before the age of 20. Drawing on the 2022 independent review recommendations, the government will bring forward new legislative proposals to raise the age of sale indefinitely. The government wants to continue the current downward trajectory and get smoking rates to 0%. There is no safe age to smoke.

Legislating to create a smokefree generation

The government will bring forward legislation making it an offence to sell tobacco products to anyone born on or after 1 January 2009. In effect, the law will stop children turning 14 or younger this year from ever legally being sold tobacco products - raising the smoking age by a year each year until it applies to the whole population. This will ensure children and young people do not become addicted in the first place.

As is the case with current age of sale legislation, the emphasis will be on those who sell tobacco products - the government has never and will not criminalise smoking. Furthermore, the phased approach means that anyone who can legally be sold cigarettes now will not be prevented from doing so in the future. These changes will be brought in following an implementation period, alongside ongoing support for current smokers to quit.

Context

The Children and Young Persons (Sale of Tobacco etc) Order 2007 increased the legal age of sale for tobacco products from 16 to 18 years old in England and Wales. There have been calls in recent years to go further. The independent review recommended the government raise the age of sale by one year each year to stop people from ever starting to smoke and create the first smokefree generation.

As noted in Chapter 1, New Zealand became the first country in the world to prohibit the sale of tobacco to anyone born after a specified date, as part of a broader set of policies announced under its Smokefree Aotearoa 2025 Action Plan. Such action is supported by most people in this country. 71% of adults in Great Britain support raising the legal smoking age by one year each year.

Policy summary

Smokefree generation policy

This policy will make it an offence for anyone born on or after 1 January 2009 to be sold tobacco products. The government will also make it an offence for anyone at or over the legal age to purchase tobacco products on behalf of someone born on or after 1 January 2009 (‘proxy purchasing’).

Products in scope of the new legislation will mirror the current scope of age of sale legislation for tobacco products (see section on product scope).

Product scope

The current age of sale restriction is imposed under the Children and Young Persons Act 1933. The age of sale restriction applies to tobacco products and cigarette papers.

We propose that products in scope of the new legislation will mirror the existing age of sale legislation which would mean that all tobacco products, cigarette papers, waterpipe tobacco (such as shisha) and herbal smoking products would be subject to the new law.

All other products such as vapes and nicotine replacement therapies would be out of scope because they do not contain tobacco and are often used as a smoking quit aid.

Age of sale statements

The Children and Young Persons (Protection from Tobacco) Act 1991 requires retailers selling tobacco to display a notice in a prominent position at the point of sale stating that ‘it is illegal to sell tobacco products to anyone under the age of 18’. This requirement would change to align with the new age of sale.

The government proposes that display statements will need to be changed and required to read “it is illegal to sell tobacco products to anyone born on or after 1 January 2009”.

Likely impact

Action on the age of sale can make a difference. In England, when the age of sale was raised from 16 to 18, it led to around a 30% reduction in smoking prevalence for 16 and 17 year olds. In the US, when the age of sale was increased from 18 to 21, the chance of a person in that age group smoking fell by 39%.

New Zealand estimates that, if well enforced, prohibiting the sale of tobacco to anyone born after 2009 could reduce their smoking rates to half of current rates within 10 to 15 years.

Figure 9 shows government modelling which forecasts smoking prevalence in all smokefree generation scenarios. While the modelling suggests prevalence will continue to decline in all smokefree generation scenarios, it forecasts that this measure could further reduce smoking rates in England among 14 to 30 year olds such that, within 3 to 10 years of implementation, they could be half of current rates and close to 0% as early as 2040.

Figure 9: Forecast smoking prevalence for ages 14 to 30

Source: DHSC modelling, to continue to be further refined ahead of publication of a full impact assessment

Each of the lines represents one of the smokefree generation modelling scenarios, from the most conservative scenario (top dotted line) to a scenario reflecting New Zealand’s modelling approach (bottom solid line). More detail on the preliminary modelling scenarios has been published alongside this paper.

Reduced smoking rates lead to fewer people dying from smoking-related diseases and fewer children exposed to second-hand smoke or living in smoking induced poverty. There are 4 major diseases that together account for almost 60% of all ill health and early deaths attributable to smoking: COPD, coronary heart disease (CHD), lung cancer and stroke. By 2075, our modelling suggests between 48,000 and 115,000 cases of these diseases would be avoided - improving people’s lives and avoiding the pain of loss for families.

DHSC modelling focuses on changes in smoking initiation rates in the 14 to 30 age group and therefore, conservatively, assumes no changes to the quit rate for current smokers and relapse rate for former smokers. Health and economic gains are expected further in the future, saving the health and care system up to £18 billion and boosting the economy by up to £85 billion by 2075 (cumulative, undiscounted). Someone who avoids a smoking-related death can be expected to live 8 to 9 years longer as a result of this change.

4. Supporting people to quit smoking

Overview

Quitting smoking is the best thing a smoker can do for their health. It has been estimated that someone who quits before turning 30 could add 10 years to their life. So, alongside taking bold action to stop the start, the government is also taking new action to support current smokers to quit - building on the existing infrastructure of funding and support we have in place through the NHS and local authorities across England.

The government is investing:

- an additional £70 million per year to support local authority-led stop smoking services (SSS) - more than doubling current spend from £68 million per year (to a total of £138 million) and supporting around 360,000 people to set a quit date each year

- an additional £5 million this year and then £15 million per year after to fund new national anti-smoking campaigns - a substantial uplift on current spend

- up to £45 million over 2 years to roll out our new national ‘Swap to Stop’ scheme - supporting 1 million smokers to swap cigarettes for vapes

- up to £10 million over 2 years to provide evidence-based financial incentives to support all pregnant smokers to quit

Local stop smoking services

SSS were established across England in 2000 to enable smokers to access a combination of behavioural support from a trained advisor, as well as medicines or stop smoking products for up to 12 weeks. Local authorities report spending £68 million in 2021 to 2022 on commissioning SSS.

SSS are an effective and cost-effective way of supporting smokers to quit, increasing the chances of quitting threefold, compared to willpower alone, and since inception have delivered over 5 million successful quits. Stop smoking products and medicines (provided by SSS) can double the likelihood of quitting compared to willpower alone, but are most effective when combined with behavioural support. SSS are also effective in reaching high-prevalence groups, with the official statistics NHS Stop Smoking Services in England showing that 55% of clients in 2022 to 2023 were recorded as routine and manual workers, long-term unemployed/never worked, unpaid home carers or those who are sick or disabled and unable to work.

However, the number of smokers seeking help to quit from SSS has declined by nearly 80% since their peak in 2012. Figure 10 shows the number of people accessing stop smoking services between the years 2000 to 2001 and 2022 to 2023 who set a quit date and managed to quit smoking successfully.

Figure 10: Number of people using SSS who set a quit date and quit successfully

Source: Statistics on stop smoking services in England

While some of this decline reflects the success of SSS in helping people quit smoking, there has also been a drop in the availability and accessibility of these services. Additionally, there has been a decrease in referrals to SSS from healthcare professionals, and a decrease in public awareness regarding the availability of this support. This is why the government is also funding an awareness raising campaign which will direct smokers to quit support.

The decline in the number of smokers accessing SSS highlights the need for continued investment in these crucial services. The latest data suggests that there were over 176,000 quit attempts with the support of a SSS in 2022 to 2023. To help reach the Smokefree 2030 ambition, the government is committing additional funding of £70 million per year to SSS. This will more than double the current local authority spend on SSS of £68 million per year to a total of £138 million, and also meet the independent review recommendation for increased investment. In total the funding will aim to support around 360,000 people to quit with 198,000 successful quits (measured as 4-week quits). As the independent review made clear, well-funded SSS are highly cost-effective and play a pivotal role in improving healthy life expectancy and narrowing the gap in health disparities.

This additional funding will ensure there is a universal and comprehensive offer across local authorities in England, while providing additional weighted funding to local authorities with the highest smoking rates to level up the communities who need it most and address health disparities. This increased investment will directly impact on the availability and quality of support offered, and the number of quits achieved in those areas that need it most. The methodology for allocating indicative funding to local authorities is published alongside this paper.

Funding will be used to help bring all services in line with quality standards that are set out by National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training guidance. It will support a core specialist team of advisors into local SSS, and a range of other trained professionals (for example, nurses and pharmacy staff) to engage with specific smoking populations that typically do not access SSS without being targeted and directed to stop smoking support. This will also support delivery of the ‘Swap to Stop’ scheme as detailed later in the chapter.

It is important to recognise that the remaining smokers are likely to be the most entrenched smokers and may find it harder to quit having experienced a number of unsuccessful quit attempts. Helping these individuals successfully quit is essential, even if it may require a higher cost per smoker. After all, these services were established with the goal of supporting all smokers in their journey to quit, whoever and wherever they are.

Awareness raising campaigns

There is strong evidence that national campaigns are effective in supporting smokers to quit and they deliver a strong return on investment and impact at scale. In particular, awareness raising campaigns play a role in dismantling common misperceptions among the public. For example, 4 in 10 smokers incorrectly believe vaping is as dangerous as smoking cigarettes. They can be targeted at current smokers, so they can make well informed choices about quitting tools.

The annual Stoptober campaign alone has driven more than 2.3 million quit attempts between its inception in 2012 and the latest evaluation in 2020. Evidence from evaluations of Stoptober campaigns showed that in 2020, the campaign generated quit attempts among 12.3% of smokers and recent ex-smokers. The Stoptober campaign emphasises that if a smoker can quit for 28 days, they are 5 times more likely to quit permanently.

The independent review recommended that the government invest £15 million to fund a nationwide, all year stop-smoking campaign. The government will invest an initial £5 million right now, and £15 million each year after, on campaigns to highlight the harms of smoking and signpost people to support. We will take a national approach, but this will be amplified in local areas with higher smoking rates and targeted at demographics most likely to start smoking or be current smokers. Combined with the increase in availability and quality of other support, this is a wide reaching, high impact proposal. It is also supported by the public: 69% of adults in England support further investment in campaigns on smoking.

Rollout of national ‘Swap to Stop’ scheme

Vaping has become the most popular quitting aid in England, and vapes are extremely effective for many, particularly when combined with additional behavioural support from SSS. They are up to twice as effective as the available licensed nicotine replacement therapy at one-fifth of the cost. The latest international research shows that smokers who use a vape every day are 3 times more likely to quit smoking, even if they did not intend to.

In April 2023, the government announced a world-first national ‘Swap to Stop’ scheme - offering a million smokers across England a free vaping starter kit, investing up to £45 million over 2 years. Smokers who join this scheme must join on one condition - they commit to quit smoking with expert support from local SSS. The scheme will target the most at-risk communities first including job centres, homeless centres and social housing providers - building on existing and effective pilots. For example, in Salford where 1,000 housing association residents joined the offer, 60% had quit smoking at 4 weeks. This scheme represents an exciting opportunity to capitalise on the potential of vaping as a tool to help smokers quit.

A large proportion of this national programme will be delivered in partnership with SSS, who will provide smokers with starter kits as part of their existing offer. The government’s increased investment in SSS will allow services to reach a larger number of smokers to ‘swap to stop’ and provide the wraparound support for more specialised staff who can provide essential behavioural support alongside the vaping kit.

Financial incentives for pregnant smokers to quit

There is a strong evidence base for the effectiveness of financial incentives for pregnant smokers. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines published in 2021 recommend the use of vouchers up to the value of £400, based on validated abstinence from smoking, as an effective way to help pregnant women to quit when used alongside behavioural support. Financial incentive schemes increase the number of women engaging with stop smoking support as well as successfully quitting. For instance, since the start of Greater Manchester’s Smokefree Pregnancy programme in 2018, they have seen the number of people who smoke at the time of delivery fall by a quarter and an estimated 3,500 more babies have been born free from the harm of tobacco smoke.

In April 2023, the government announced the rollout of a financial incentives scheme for all pregnant smokers by the end of 2024. This programme will offer all pregnant smokers the best chance of becoming, and staying, smokefree. Those who take up the offer will receive vouchers to a maximum of £400. These will be issued at specified time points during the quit journey, contingent on ongoing engagement with behavioural support and evidence of smokefree status.

Women who receive incentives are twice as likely to successfully quit throughout pregnancy (and remain a non-smoker postpartum) compared to those that do not receive incentives. Supporting more women to have a smokefree pregnancy will reduce the number of babies born underweight or with health problems (for example, respiratory, heart defects) requiring neonatal and ongoing care. It will also reduce the risk of miscarriage and stillbirth. Babies exposed to tobacco smoke in pregnancy or in the home are also at a higher risk of sudden infant death (cot death).

5. Youth vaping

Overview

The government is committed to having the biggest impact possible in reducing youth vaping. The government is also conscious of the potential impact that new policies may have on adult smokers looking to quit and the associated health benefits, as vaping is substantially less harmful than smoking and can be an effective tool in supporting adult smokers to quit. Ensuring vapes can continue to be made available to current adult smokers is vital to tackle smoking. The government is therefore consulting on a set of proposals to reduce youth vaping, ensuring we get the balance right between protecting our children and supporting adult smokers to quit.

There has been a recent and highly concerning surge in the number of children vaping and the evidence shows that vaping products are regularly promoted in a way that appeals to children, through flavours and descriptions, cheap convenient products and in-store marketing - despite the risks of nicotine addiction. Alongside the findings from the call for evidence, the government has drawn on the latest public health evidence both in the UK and internationally, what we know has worked in reducing youth smoking, and extensive learning from stakeholders. The government is also responding to recommendations made in the independent review to tackle youth vaping.

The proposals the government is looking at include:

- restricting vape flavours

- regulating vape packaging and product presentation

- regulating point of sale displays

- restricting the sale of disposable vapes

- introducing an age restriction for non-nicotine vapes

- exploring further restrictions for other nicotine consumer products such as nicotine pouches

- preventing industry giving out free samples of vapes to children

These actions would complement each other, forming a suite of measures that will work together to reduce the various ways that vapes appeal to children, with the aim of reducing youth vaping and the potential for children to be exposed to the risks.

Restricting vape flavours

Our call for evidence showed us that children are attracted to the fruit and sweet flavours of vapes, both in their taste and smell, as well as how they are described. So, restricting flavours has the potential to significantly reduce youth vaping.

So, the government is considering new legislation to regulate the flavours of vapes and their descriptions. To avoid unintended consequences on youth and adult smoking rates, the scope of restrictions will need to be carefully considered. The options for how the government will seek to do this will be detailed in a consultation later this month.

Context

Vape liquids (e-liquids), sometimes known as vape juice, is typically composed of nicotine, propylene glycol and/or glycerine, and flavourings. The TRPR currently restricts certain ingredients including colourings, caffeine, and taurine. However, it does not restrict any combinations of flavours or flavour types.

There are a vast and diverse variety of flavours on the UK market including: tobacco (imitating cigarettes), menthol and mint, fruit flavours (for example, strawberry, blueberry and mango), dessert and sweet flavours (for example, bubblegum, cotton candy, caramel or cheesecake), tobacco blends (combining tobacco with vanilla, caramel or nuts), and custom mixes (vape liquid mixed by users to suit their personal preferences). The attractive wording (descriptor names) can also entice children to try vaping, such as ‘fiery flavoured strawberry’ and ‘berry blast’: sweet flavours that children may be familiar with.

Evidence on the use of vape flavours

In the UK, a 2023 survey by ASH shows that the most frequently used vape flavouring for children is ‘fruit flavour’ with 60% of current children using them. 17% of children who vape choose sweet flavours such as chocolate or candy and 4.8% choose to vape energy or soft drink flavours. Figure 11 shows the most frequent flavours chosen by young people.

The use of flavoured vapes in smokers has also increased. In 2015, most adults who vaped used tobacco flavour. However, in recent years there has been a shift, and in 2023 more adults are choosing fruit flavours (47%), as well as mint and menthol (17%), and tobacco (12%). Figure 12 shows the most frequent flavours chosen by adults.

Flavours are an important factor in motivating young people to start vaping and makes them more attractive to existing users. Evidence suggests consumers also prefer flavoured vapes, and flavour is important for adolescents in both vaping trial and initiation.

Figure 11: Most frequently chosen e-cigarette liquid flavour, current vape users 11 to 17, Great Britain

Source: ASH smokefree Great Britain youth surveys

Figure 12: Most frequently chosen e-cigarette liquid flavour, adult vape users, Great Britain

Source: ASH smokefree Great Britain adult surveys

There is evidence that flavoured vaping products can assist quitting smoking. London South Bank University found that smokers who got advice picking their vape flavour, and received supportive text messages and/or expert support, are much more likely to quit. It found that after 3 months 25% were smokefree compared with 12% who received no support. A further 13% had reduced their cigarette consumption by more than 50%.

Flavourings may also encourage daily use. Among smokers not intending to quit, daily use is strongly associated with subsequent smoking cessation, but among young people, daily use may be associated with a greater risk of subsequent dependence.

Regulating point of sale displays

Unlike tobacco products, vapes are currently allowed to be displayed at the point of sale. It is unacceptable that children can see and pick up vapes in retail outlets easily due to them being displayed within aisles, close to sweets and confectionary products and on accessible shelves.

So, the government is considering bringing forward legislation on point of sale displays to keep them away from children.

Context

Analysis from Imperial College London looked at data collected in the annual ASH survey of youth vaping. Comparing 12,445 responses to an online survey by children aged between 11 to 18 over the 5 years from 2018 to 2022, researchers found increases in the proportion of children reporting that they had seen vapes on display in shops.

By contrast, tobacco point of sale restrictions in England reduced the exposure of cigarettes in shops to children. The likelihood of noticing cigarettes decreased from 81% in 2018 to 66% in 2022 for small shops and from 67% to 59% in supermarkets. This also coincided with a decrease in buying cigarettes in shops.

The government wants to mirror this trend for vaping, especially since the often-colourful nature of vaping displays appeals to children. Limiting this exposure is a necessary step to reducing experimental use among children and young people. Legislation is needed to keep vapes out of sight from children. However, we do not want it to inhibit those who currently smoke from accessing vapes as a quit aid so they must remain visible enough. There is strong public support for this. A 2023 ASH public support survey found that 74% of adults in England support prohibiting point of sale promotion of vapes.

Specialist vape shops could be an exception to this. These are retail outlets that specialise in the sale of vaping products. They normally have a far wider selection of devices and products available compared to general retailers such as supermarkets and off licences.

Regulating vape packaging and product presentation

Vapes can entice children to start, and continue, vaping through brightly coloured products and packaging, and imagery such as cartoons. To tackle this, the government is considering further regulation of vape packaging and product presentation, ensuring that neither the device nor its packaging targets children.

Context

The Tobacco and Related Products Regulations 2016 (TRPR) outlines the requirements relating to the labelling and presentation of vaping products. It sets out what can be written on a unit or container pack of the vape or refill container. Products may not, for example, suggest that a particular vape is less harmful than other vape or refill containers, has revitalising, energising, healing, rejuvenating, natural or organic properties, and/or has other health or lifestyle benefits. It must also include a health warning.

However, unlike tobacco packaging, vape packaging can come in different colours, styles, and shapes. They can include brand names and different types of images and formatting. The products themselves can be designed and displayed differently, in ways that can make them more attractive to children. While mod or tank devices are often wrapped in more neutral packaging, vape liquids and disposable vapes are regularly sold and marketed in a range of brightly coloured designs.

Packaging and design features of vapes have been shown to appeal to children. The presentation of vape packs can vary significantly, which can influence a child’s intention to try different vaping products. Research on standardised packaging shows that standardising vape packaging with reduced brand imagery can decrease the appeal of vape products among young people. It specifically decreased the appeal among young people who have not smoked or vaped previously, without reducing its appeal among adult smokers.

Historically, the branding of tobacco products made them more appealing to children. This led to the government introducing standardised packaging across cigarettes and hand rolling tobacco. The Standardised Packaging of Tobacco Products Regulations 2015: post-implementation review found evidence that suggested prohibiting tobacco branding reduced the appeal of tobacco products to children, with young non-smokers and occasional smokers potentially affected the most. Other studies have confirmed this and demonstrated that standardised packaging reduced the appeal of smoking overall, particularly to young people.

We know that there is strong public support for regulation of vape packaging and presentation. The 2023 ASH public opinion survey found that 76% of adults in England support limiting the names of sweets, cartoons and bright colours on vape packaging.

Restricting the sale of disposable vaping products

The use of disposable vaping products (sometimes referred to as single use vapes) has increased substantially in recent years. A disposable vape is a type of vape designed to be single use. These devices are neither rechargeable nor refillable and are discarded when it runs out of charge or e-liquid. They contain plastic, copper, rubber, and a lithium battery. Some parts, like the battery, can be widely recycled, whereas other parts, such as any rubber pieces, are not easily recyclable.

The government is concerned about the threat that single-use disposable products pose to the environment and the large number of children that are using disposable vapes. The government is considering restricting the sale of disposable vapes using powers under section 140 of the Environmental Protection Act 1990.

Context

Figure 13 shows the proportion of young vape users that most frequently use disposable vapes has significantly increased in recent years. ASH’s Use of e-cigarettes among young people in Great Britain report found that in 2021, only 7.7% of current vape users aged 11 to 17 used disposable vapes, which increased to 52% in 2022 and 69% in 2023.

Disposable vapes are convenient and easy to use which is what is attracting children and young people to begin or continue vaping. However, this convenience can also help adults quit smoking.

Disposable use is growing for adults, with 31% of adult vape users mainly using disposables in 2023 compared with 2.3% in 2021. However, ASH’s Use of e-cigarettes among adults in Great Britain report shows that for adults, the most used type of vape device remains a refillable tank system, with 50% of current vape users using this device.

Figure 13: Most frequently used e-cigarette device type, 11 to 17 year olds in Great Britain

Source: ASH smokefree Great Britain youth surveys

The risks of waste vape products

The rise in the use of disposable vapes has inevitably led to a rapid increase in the volume of these products becoming waste. When littered, disposable vapes introduce plastic, nicotine salts, heavy metals, lead, mercury, and flammable lithium-ion batteries into the natural environment. This contaminates waterways and soil, posing a risk to the environment and animal health. Disposable vapes also pose a fire risk when not separately collected for specialist recycling, as lithium-ion batteries can ignite when crushed in a refuse vehicle or at waste-processing plants.

Disposable regulations for vapes

It is important that these products are disposed of correctly. The Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment Regulations 2013 (WEEE) require manufacturers and importers of equipment, including vapes, to finance the cost of collection and proper treatment of equipment that is returned to dedicated collection points, which are usually household waste recycling centres. Retailers, both those with stores and those selling online, also have take-back obligations for unwanted vapes on the sale of new products. There are also obligations under The Waste Batteries and Accumulators Regulations 2009. Emerging evidence suggests compliance with these obligations is low, given the recent surge of businesses supplying disposable vapes. Both the WEEE and batteries regulations are being reviewed, with consultations planned by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs for later this year.

Research on vape disposal by YouGov commissioned by Material Focus found that almost 5 million disposable vapes are either littered or thrown away in general waste every week. This has quadrupled in the last year and is equivalent to the lithium batteries of 5,000 electric vehicles being thrown away per year. The report found 52% of 18 to 34 year olds who bought a vape in the last year bought a single-use product. The report also found that over 360 million single use vapes are bought in the UK each year and concerningly 73% of these vapes are thrown away.

Non-nicotine vapes

The majority of vapes sold in the UK contain nicotine. Non-nicotine vapes (or nicotine-free vapes) are not subject to the same product standards and age restrictions for nicotine-containing vapes. Instead they are covered by the General Products Safety Regulations (GPSR) 2005. Like nicotine vapes, they can come in liquid form to be used in a device or already contained as a liquid in a device. The GPSR requires providers to ensure only safe products are placed on the market, together with any necessary warnings for safe use of the product.

There is clear data of young people using non-nicotine vapes in Great Britain. Internationally, around 30 countries have prohibited the sale of non-nicotine vapes, and another 50 countries allow them to be sold but with age restrictions.

In May 2023, the Prime Minister laid out the government’s commitment to review the rules on selling nicotine-free vapes to under 18s, to ensure our rules keep pace with how vapes are being used.

The government will seek to introduce legislation to prohibit the sale of non-nicotine vapes to under 18s as a first step to protect children. The government is also interested in views on whether we should also impose further restrictions on non-nicotine vapes, which we will explore in our consultation later this month.

Other nicotine consumer products

There are other consumer nicotine products in the UK market such as nicotine pouches. They too do not come under the TRPR, but GPSR also applies to these. There are no age of sale restrictions, but the government does have regulatory making powers to introduce these.

A recent study suggests that, although nicotine pouch use is low among adults (0.26% or 1 in 400 users in Great Britain), it is increasingly popular with younger male audiences. The youth vaping call for evidence included comments about children using nicotine pouches but there is limited data about children using them.

In our consultation later this month, the government will explore whether further regulatory measures are needed for other nicotine consumer products such as nicotine pouches.

Preventing industry giving out free samples of vapes to children

In May 2023, the Prime Minister announced a commitment to close the loophole in our laws which allow retailers to give free samples of vapes (and other nicotine containing products) to under 18s. ASH found that 2% of 11 to 15 year olds who have ever vaped (approximately 20,000) said that their first vape was given to them by a vape company. There is currently no restriction on the free distribution of samples of nicotine or non-nicotine vapes. This differs from the position on tobacco products, since the free distribution of tobacco products is prohibited under the Tobacco Advertising and Promotion Act 2002. The government plans to address this loophole at the next legislative opportunity available.

6. Enforcement

Overview

A strong approach to enforcement is vital if the smokefree generation policy is to have real impact. Underage and illicit sale of tobacco, and more recently vapes, is undermining the work the government is doing to regulate the industry and protect public health.

The sale of illicit products frequently targets children and young people in disadvantaged communities, widening health disparities. The impact of the illicit trade is often the greatest in the most deprived areas of the country. Tobacco smuggling also costs over £2.8 billion in lost tax and duty revenue each year. This deprives the UK of vital money that could be used to fund essential public services - instead putting it in the hands of criminals.

In this chapter, we set out additional steps that the government will take to clamp down on those irresponsibly selling tobacco products and vapes to underage people and preventing illicit products from being sold. This includes:

- providing £30 million additional funding per year (from April 2024) to support enforcement agencies such as trading standards, Border Force and HMRC to implement and enforce the law (including enforcement of underage sales) and tackle illicit trade

-

HMRC and Border Force publishing an updated Illicit Tobacco Strategy, which will:

- set out plans to target illegal activity at all stages of the supply chain to stamp out opportunities for criminals in light of the new rules