The State of UK Competition Report April 2022

Published 29 April 2022

Executive Summary

Context

Recognising the importance of competition to economic performance, in March 2021 the Chancellor and the Business Secretary jointly commissioned the CMA to carry out an assessment of the state of competition in the UK.[footnote 1] This followed an earlier assessment published by the CMA in November 2020.[footnote 2] Others have also noted the value of such assessments: for example, John Penrose MP’s report on competition policy – Power to the people [footnote 3] – called for a ‘State of Competition and Consumer Detriment’ report.[footnote 4]

This second State of Competition report responds to the Chancellor’s and Business Secretary’s request. Its central aim is to provide information and analysis to help inform public debate and policy. It builds on the CMA’s first assessment, presenting new, improved and updated indicators of the state of competition. In particular, the latest report presents:

-

Updated indicators of the state of competition, including concentration, profitability and markups, and entry and exit.

-

Improved estimates of concentration that adjust for the effects of international trade and the effects of competing firms having the same owners (so-called “common ownership”).[footnote 5]

-

An assessment of whether consumers on lower incomes face less competitive markets.

-

Analysis of the latest surveys examining businesses’ and consumers’ experience of markets.

-

Specific analysis of competition in digital markets, which are poorly captured by existing economic statistics.

The importance of competition

The COVID-19 pandemic, the UK’s changing trade relationship with the EU, disruption to supply chains and shipping, and rising energy costs have all brought significant change and upheaval to the UK economy over the past few years. In such circumstances it is more important than ever that competitive intensity across the economy is monitored and supported.

Effective competition happens when businesses compete to win customers by offering them a better deal. When firms compete effectively with each other, they cannot raise prices, or cut quality and service, without losing business.

If competition is weak or ineffective, firms do not face the same pressures to keep prices down; to keep quality up; to operate efficiently; or to innovate. This comes at a cost to consumers, other businesses and the wider economy.

-

Weak competition harms consumers: the cost of weak competition is borne by consumers in the form of higher prices, lower quality and less innovation. This raises the cost of living,[footnote 6] and it can hit the poorest households hardest.[footnote 7] With fewer suppliers to choose from, and less innovation, consumers also suffer from reduced choice.

-

Weak competition can harm businesses: just as consumers pay more when competition is weak, businesses pay more than they should to their suppliers. And when markets are dominated by a small number of powerful firms, they can use their position to prevent other businesses from entering and growing. Both of these factors lead to higher prices for customers of those businesses.

-

Weak competition harms the economy as a whole: because firms do not face pressures to operate as efficiently as possible, the people employed by them are not as productive as they could be. Nor do they face the same pressures to innovate, in order to get ahead of their rivals. This inefficiency and lack of innovation comes at a cost to the economy as a whole, in the form of reduced job creation, weaker productivity and slower wage growth. In countries where competition is stronger, productivity and hence wage growth tends to be higher. [footnote 8]

Findings

Overview

The strength of competition is not generally directly observable, but must instead be inferred by analysing relevant indicators. Taken together these indicators can shine a light on the state of competition.

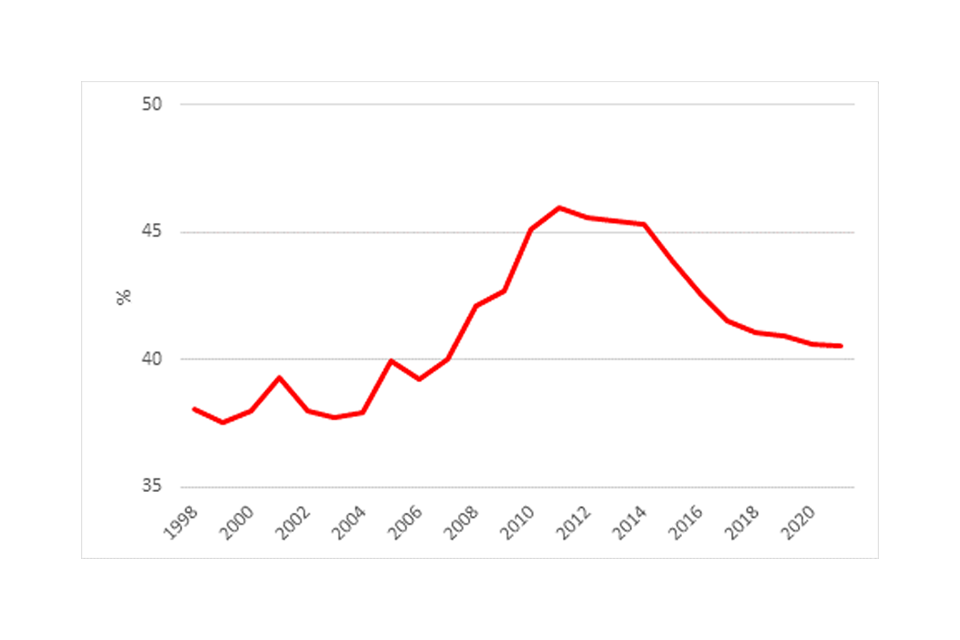

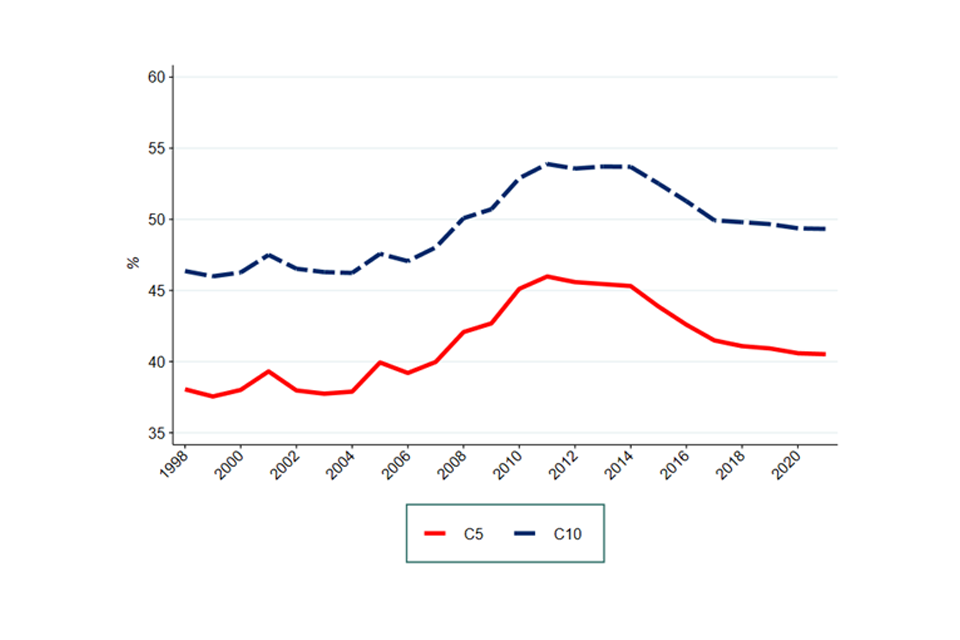

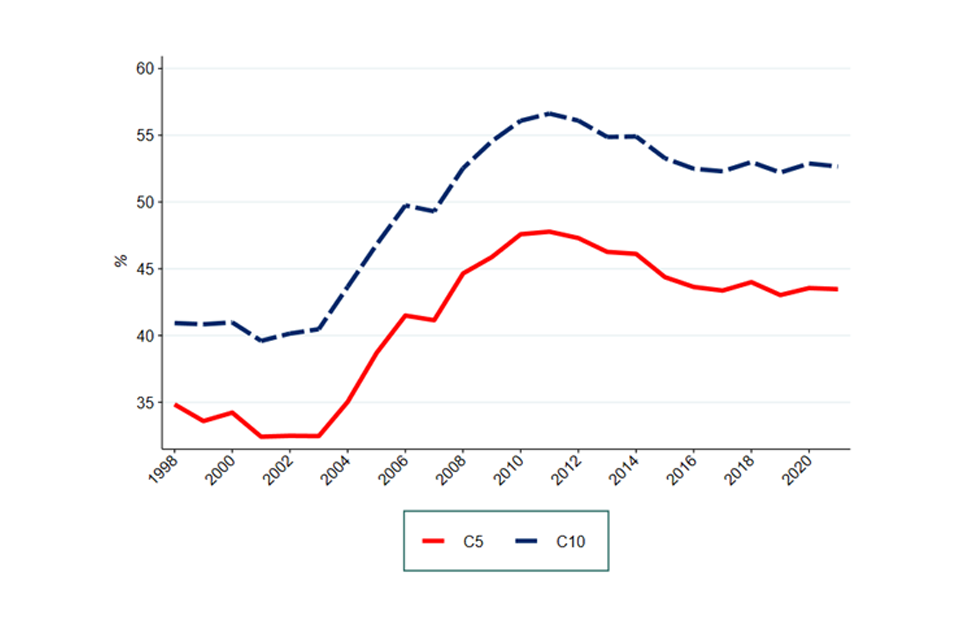

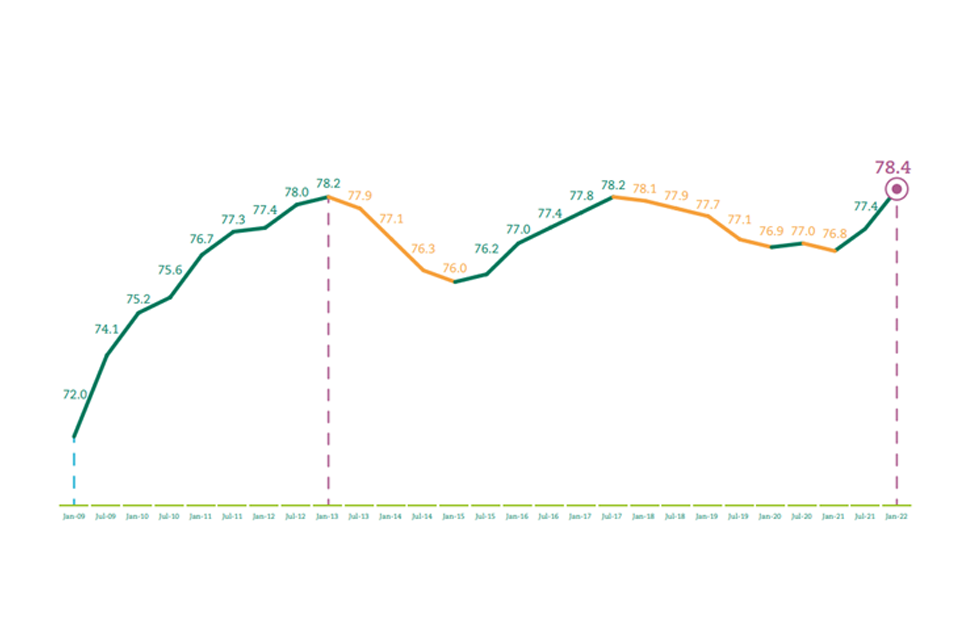

“Static” indicators of competition include concentration (the extent to which industries are dominated by a small number of large firms) and business profitability. These measures can help to tell us about the state of competition at a particular point in time: high concentration or high profitability in an industry may be signals that competition is weak. Tracking how such static measures change through time can shed light on how well the competitive process is working in the UK economy. Figure 1 shows the average market share of the 5 largest firms in each industry (the so-called C5 measure) over the last 20 years. It shows that there was a marked increase in concentration in the years after the 2008 financial crisis. Since then, concentration has fallen, but it still remains above levels seen prior to 2008.

Figure 1: Average C5 (average market share of the 5 largest firms in each industry) [footnote 9]

Image description: A line graph showing the average market share of the largest 5 firms in each industry between 1998 to 2021.

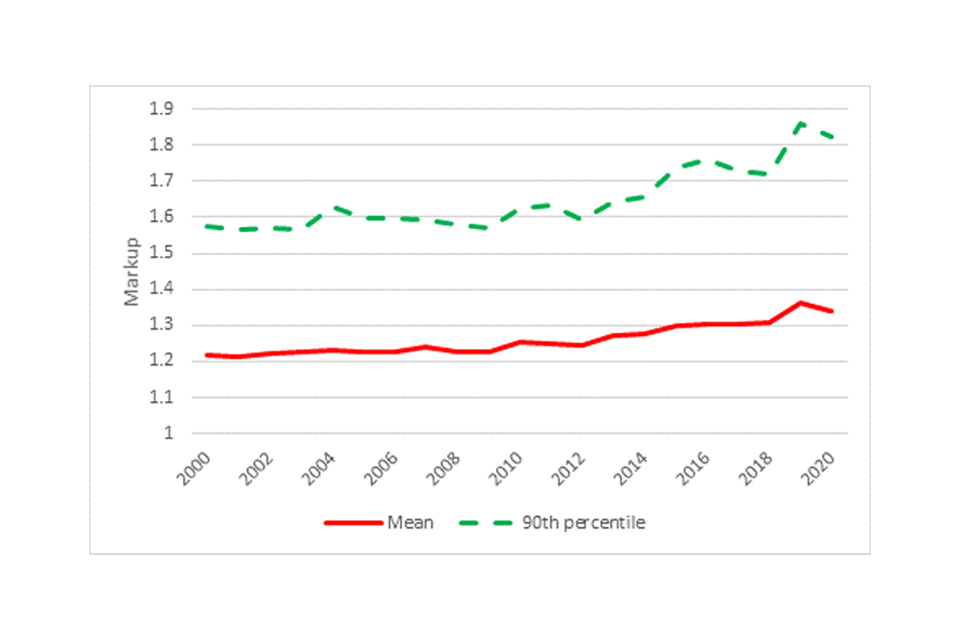

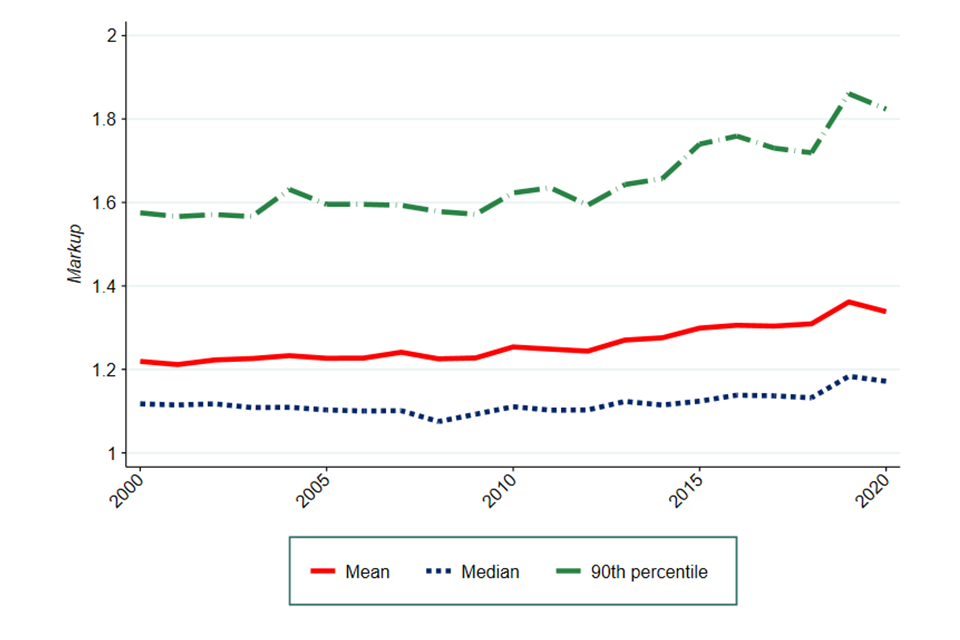

There is also some evidence that on some measures profitability is higher than before the 2008 crisis. Figure 2 shows data on the markup of prices over marginal costs. It shows that average markups have increased since 2008 from just over 20% to about 35%. It also shows that the increase in markup has been higher for the 10% most profitable firms.

Figure 2: Price-cost markups since 2000[footnote 10]

Image description: A line graph showing the mean (red line) markup of price over marginal cost and the equivalent graph for firms in the 90th percentile (dotted green line) between 2000 to 2020.

Further analysis of static measures can be found in concentration, industry structure, and distributional impacts and markups and profitability.

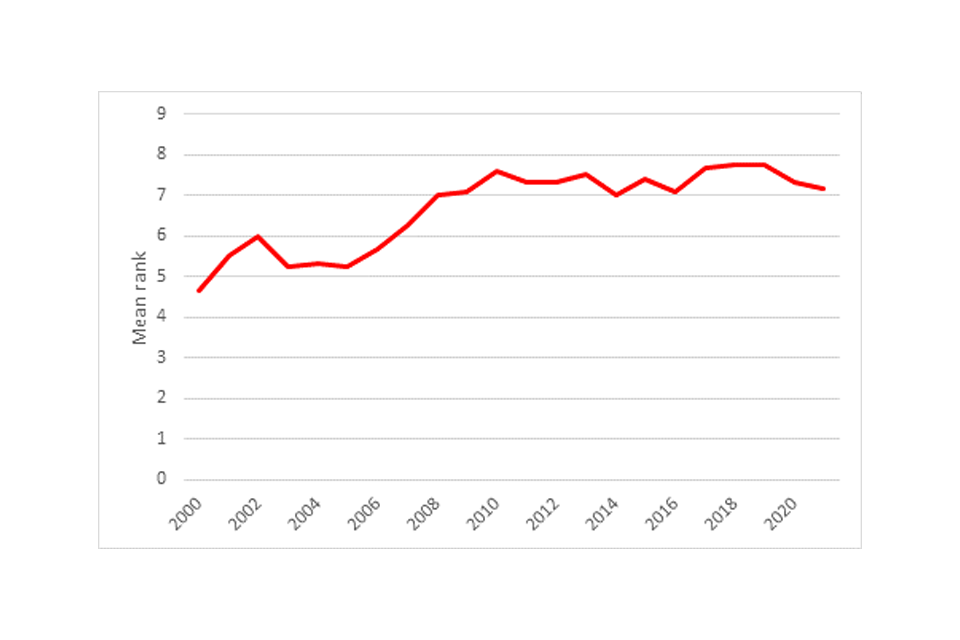

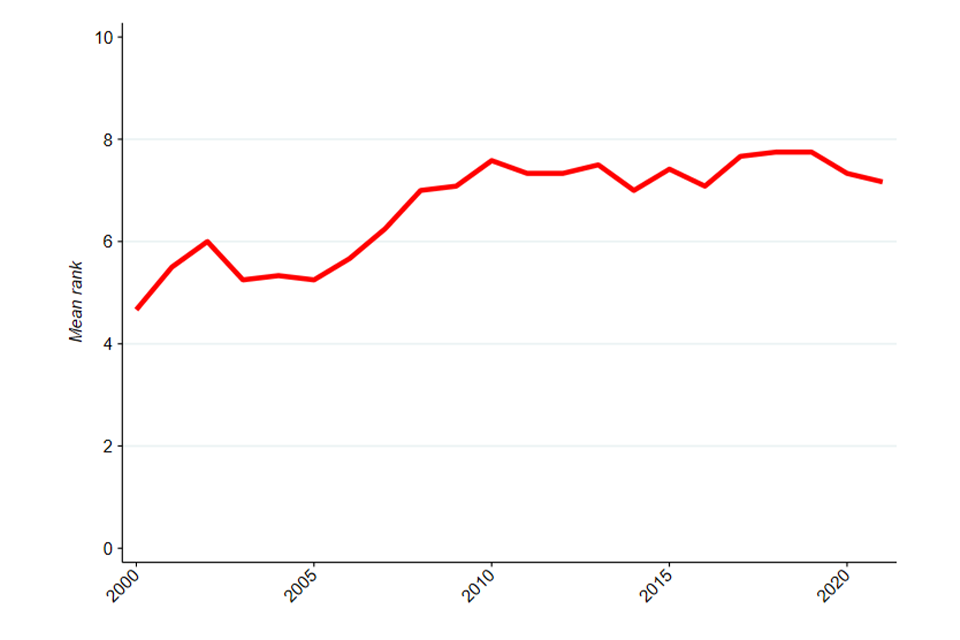

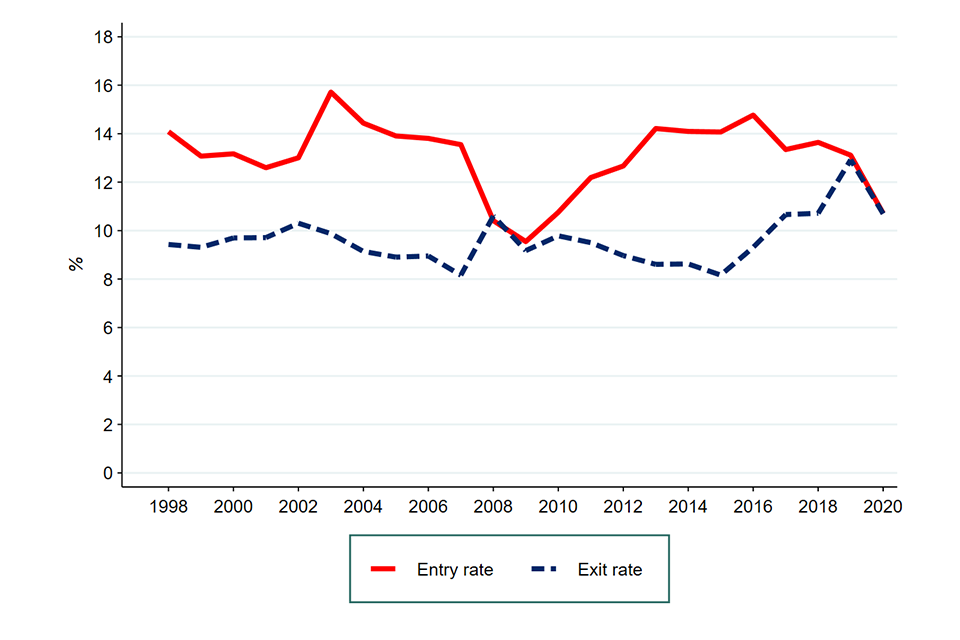

“Dynamic” indicators of competition include rates of firm entry and exit, and the extent to which high-performing firms sustain or get dislodged from their position. These measures help us assess the extent of change and churn in an industry over time. In an open competitive market we expect to see firms entering and leaving markets, and jostling for market share, as this is an important part of the competitive process. Looking at these measures, there is evidence that the largest and most profitable firms are able to sustain their strong position for longer than they used to. Figure 3 shows the rank persistence of the top 10 firms in each industry over time. The rank persistence measures how many of the top 10 firms in an industry were also in the top 10 3 years ago. Figure 3 shows that over the last 20 years, the likelihood of the largest firms in an industry remaining the largest firms has increased. The chart shows that whilst the rank persistence was around 5 before 2008, it has been between 7 and 8 since.

Figure 3: Rank persistence (averaged across industries) [footnote 11]

Image description: 3 line graphs illustrating trends between 2003 to 2020. The line in red illustrates the average markups across industries and is trending upwards. The dotted green line represents the average EBIT margin across all industries and is gently sloping downwards and the dotted blue line represents average ROCE and is also trending upwards.

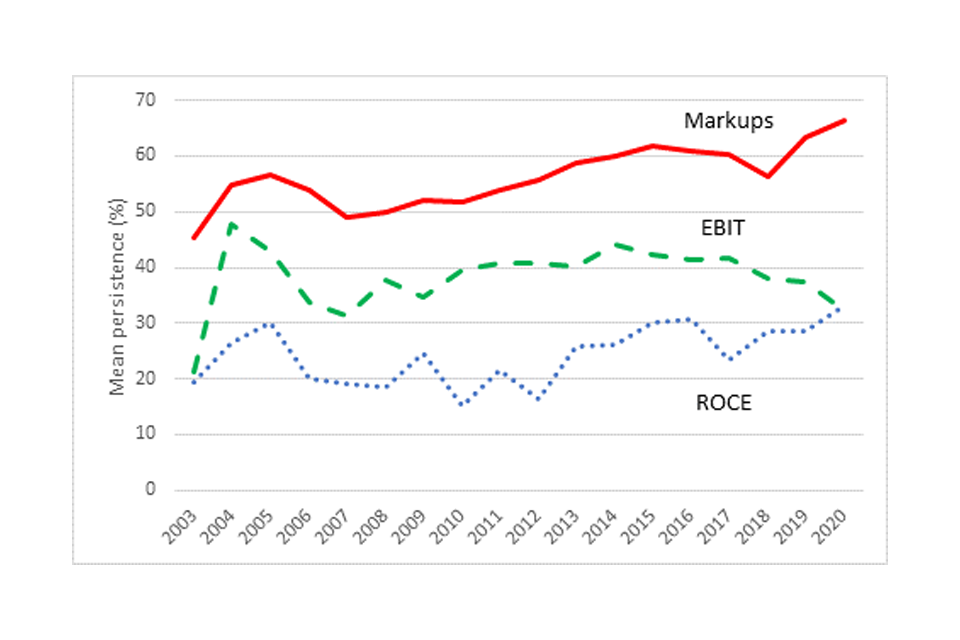

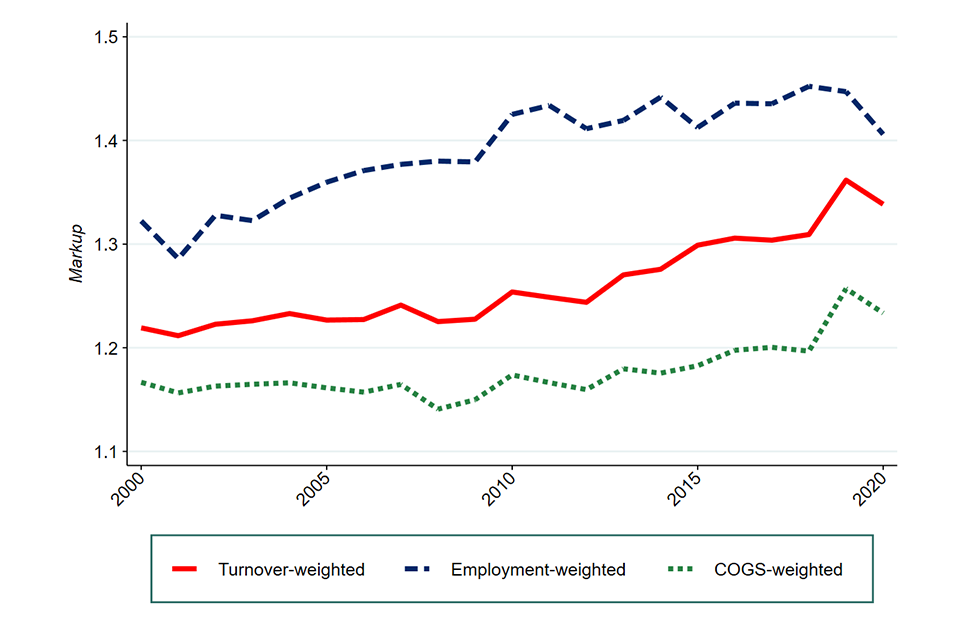

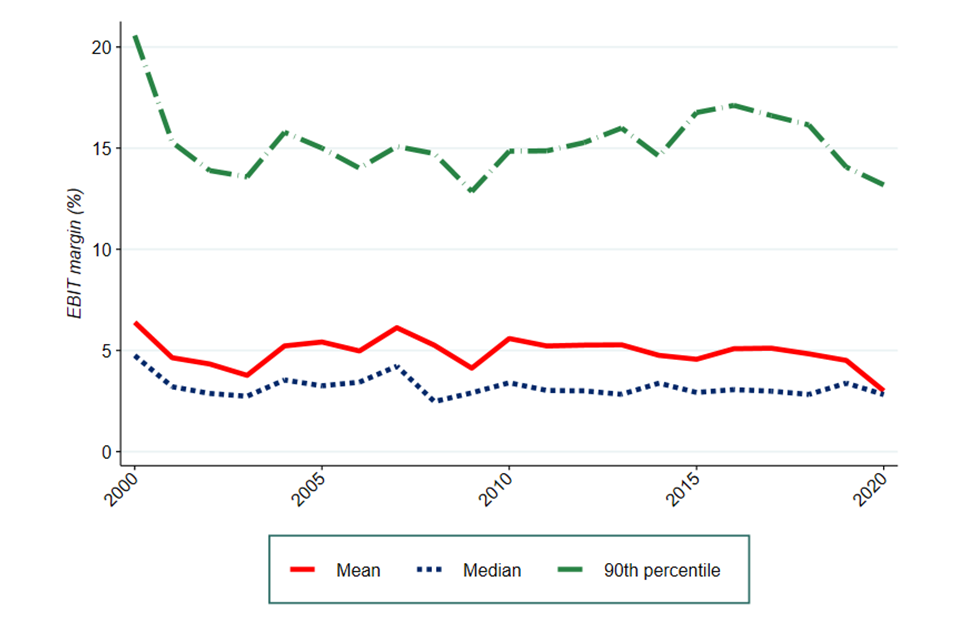

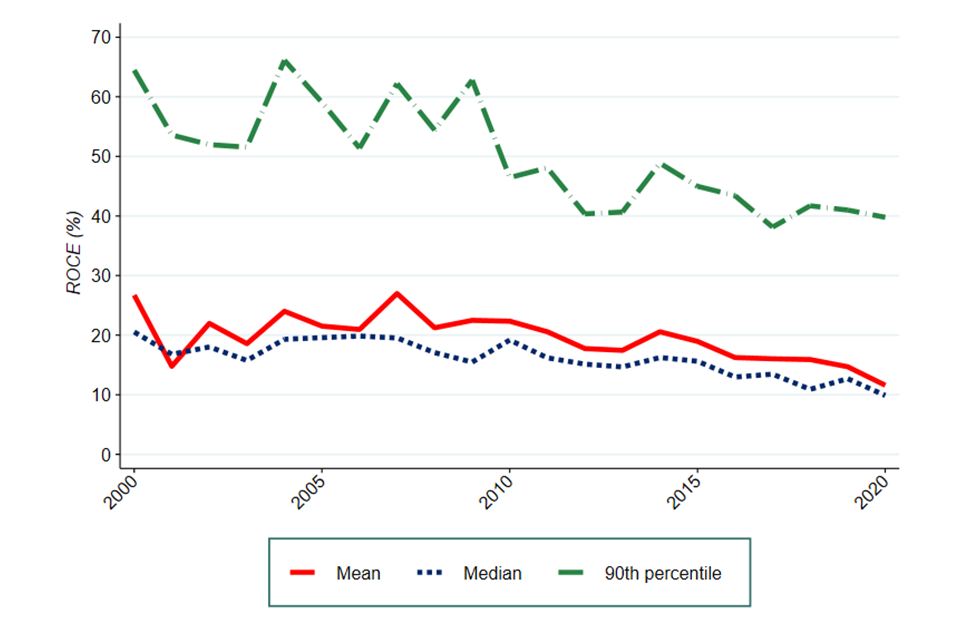

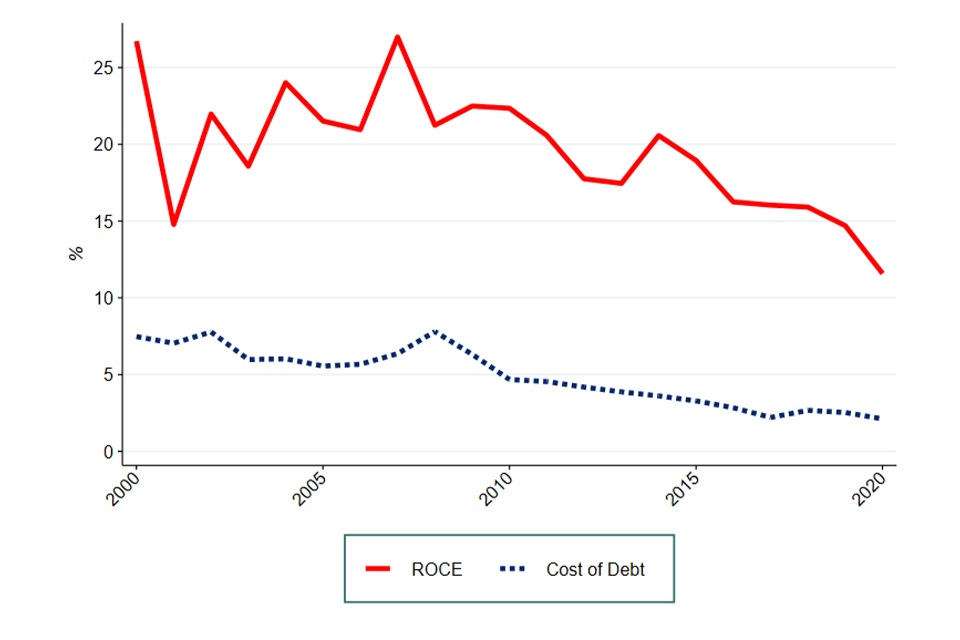

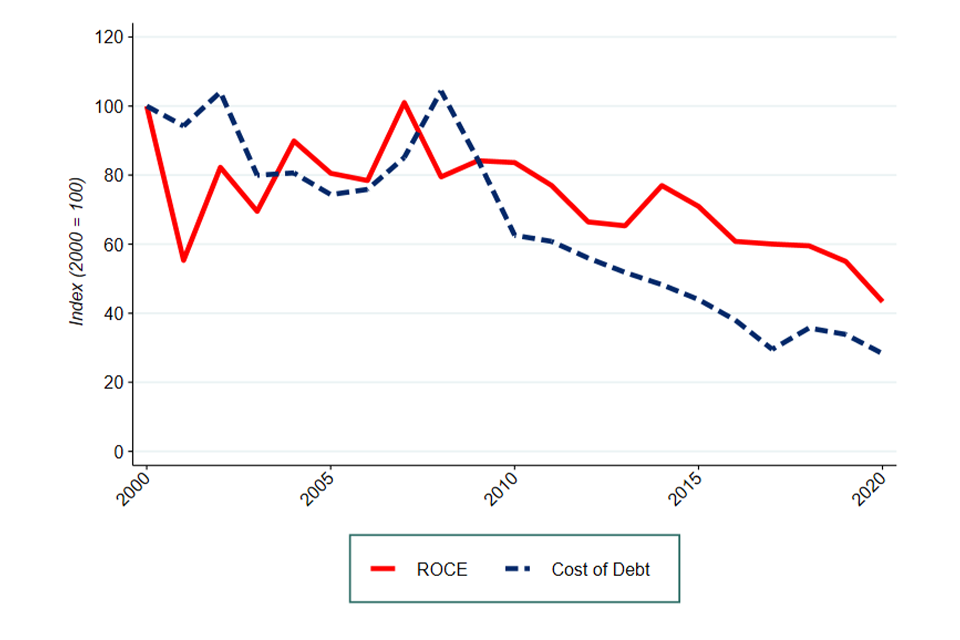

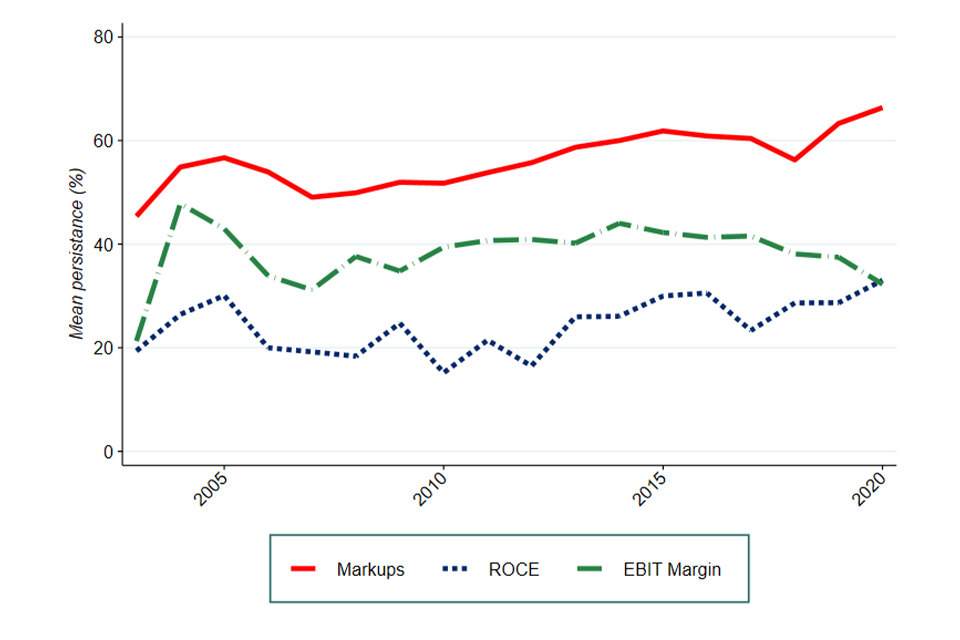

We have also looked at profit persistence. This shows the proportion of the top 10 most profitable firms in each industry which were also in the top 10 3 years ago. This provides a more mixed picture than the rank persistence measure, as shown in Figure 4. Profit persistence has increased as measured by markups over marginal costs and the Return on Capital Employed (ROCE), but has fallen back to pre-2008 levels for Earnings Before Interest and Taxes (EBIT).

Figure 4: Profit persistence (averaged across industries)[footnote 12]

Image description: A line graph showing the median HHI across the UK economy from 1998 to 2021.

Further analysis of dynamic measures can be found in other indicators of competition.

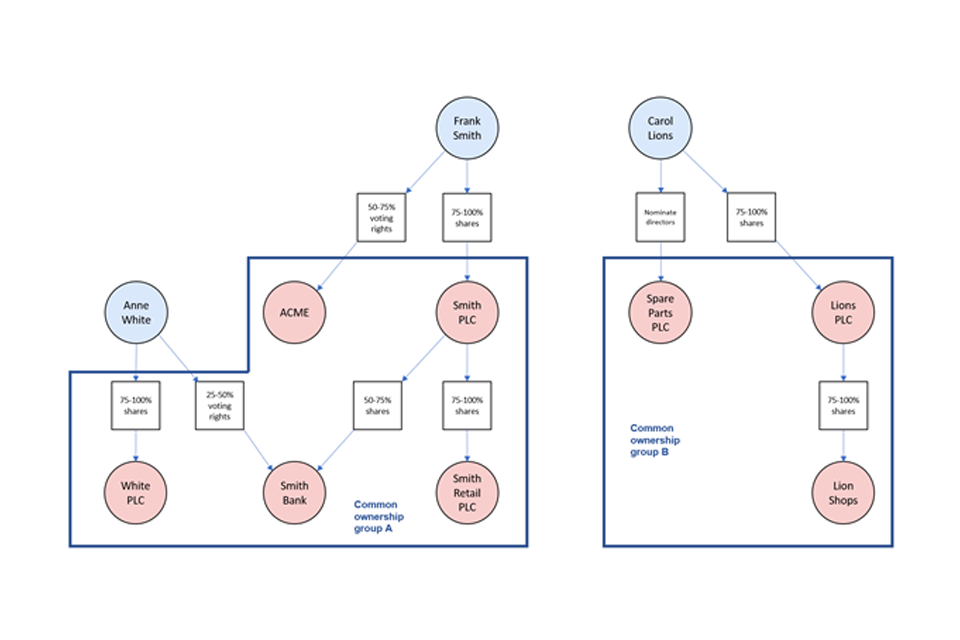

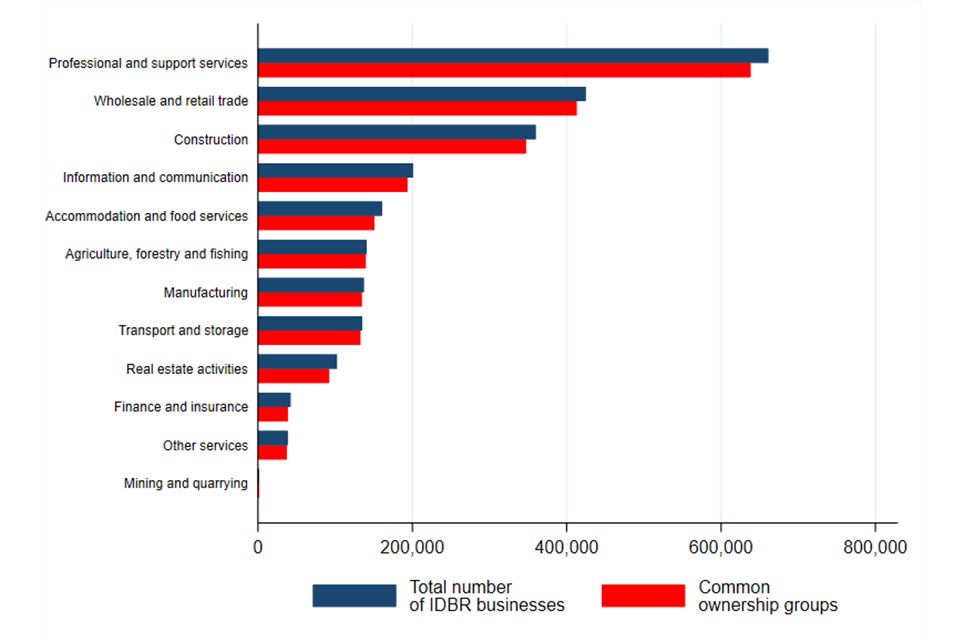

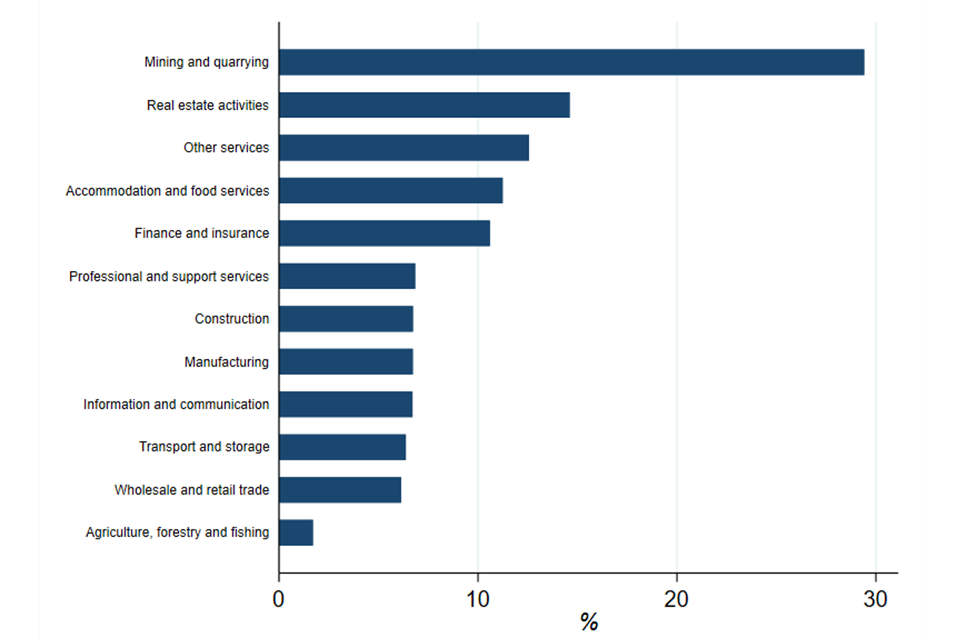

When companies in the same market are controlled (or part-controlled) by the same owners, the commercial incentives for them to compete will be weaker or even absent. For the first time, this report presents preliminary data on the effects of this common ownership by combining 2 extremely large datasets of UK businesses. Our assessment, which considers common ownership at 25% and 50% thresholds,[footnote 13] shows that:

-

The effect of common ownership on the overall number of independent businesses is modest: only 160,000 businesses out of the 2.6m analysed are part of a common ownership group.

-

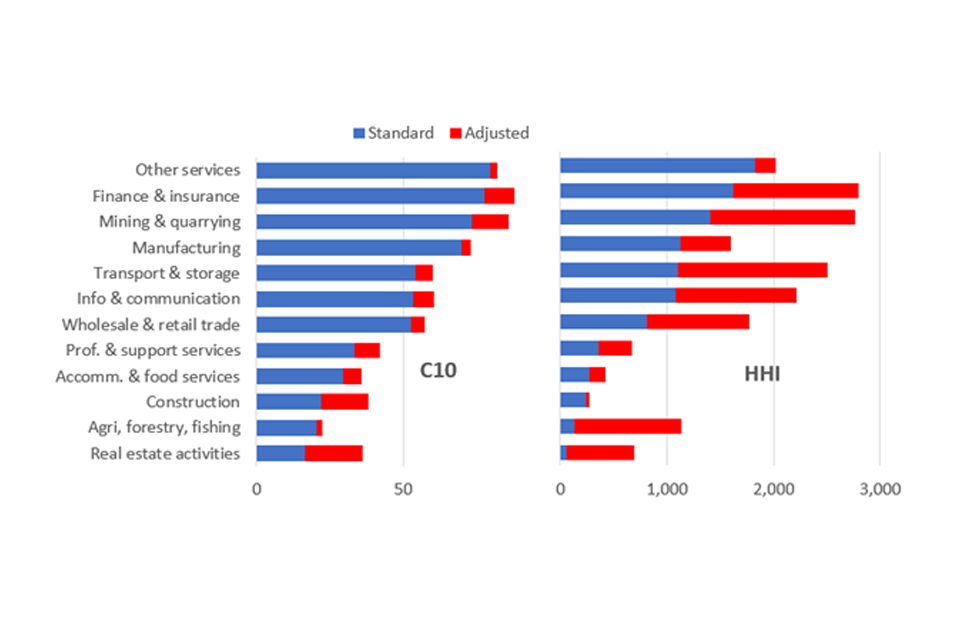

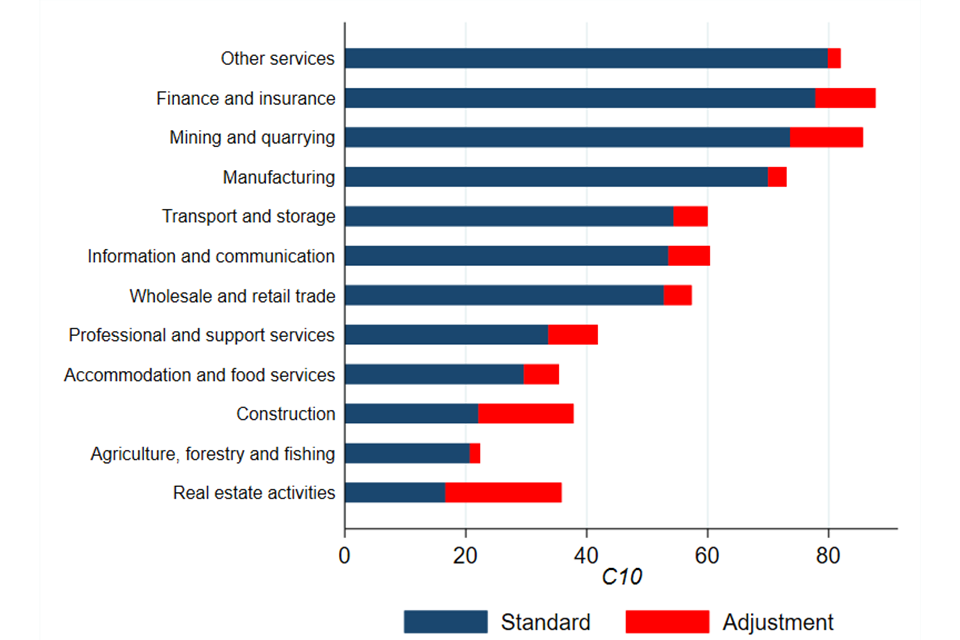

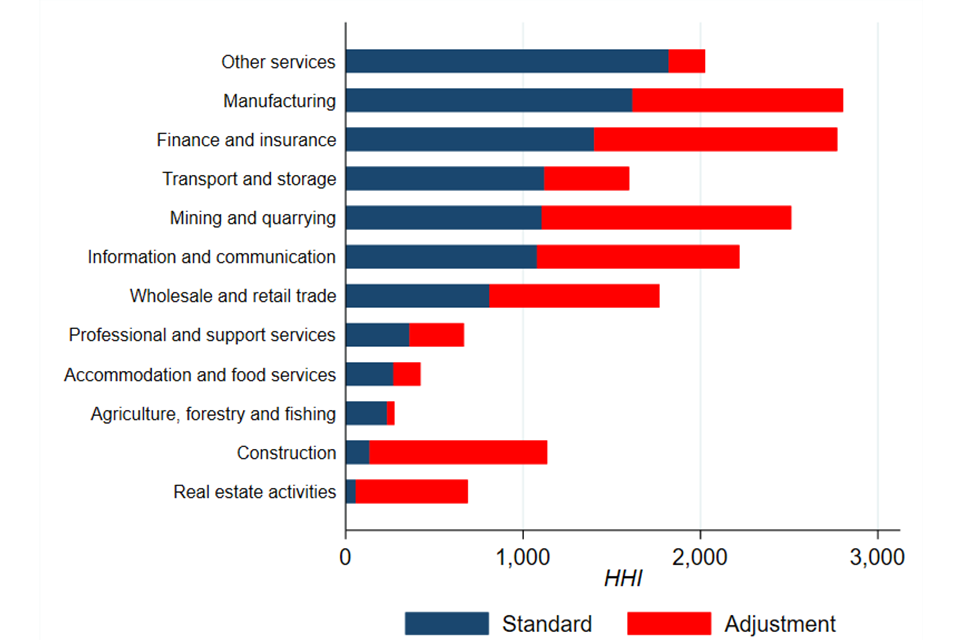

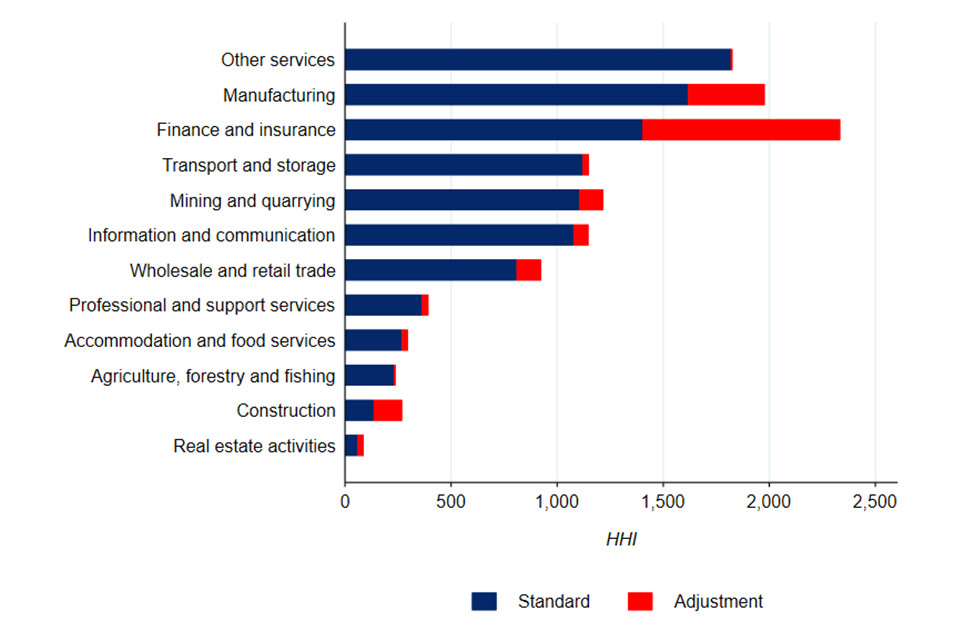

However, common ownership is more prevalent among larger businesses and in certain sectors: for example, in mining and quarrying, almost 30% of businesses are part of a common ownership group. Because of this, accounting for common ownership materially increases measured concentration in some sectors. Figure 5 shows this using 2 different measures of concentration. One is the combined market share of the 10 largest firms in each industry (C10); the other is the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI). [footnote 14] This chart shows that common ownership can have a significant effect on the HHI.

-

It should be reiterated, however, that this is very preliminary analysis that we will seek to refine in future.

Figure 5: Impact of accounting for common ownership on the C10 and HHI [footnote 15]

Image description: Two stacked bar charts. The chart on the left represents the share of the top 10 firms by industry using standard measures (blue bars) and how these shares change once common ownership is factored to produce adjusted measures (red bars). The chart on the right represents the HHI of firms by industry (blue bars) and how these change once common ownership is considered (red bars).

Further analysis of common ownership can be found in adjusted concentration.

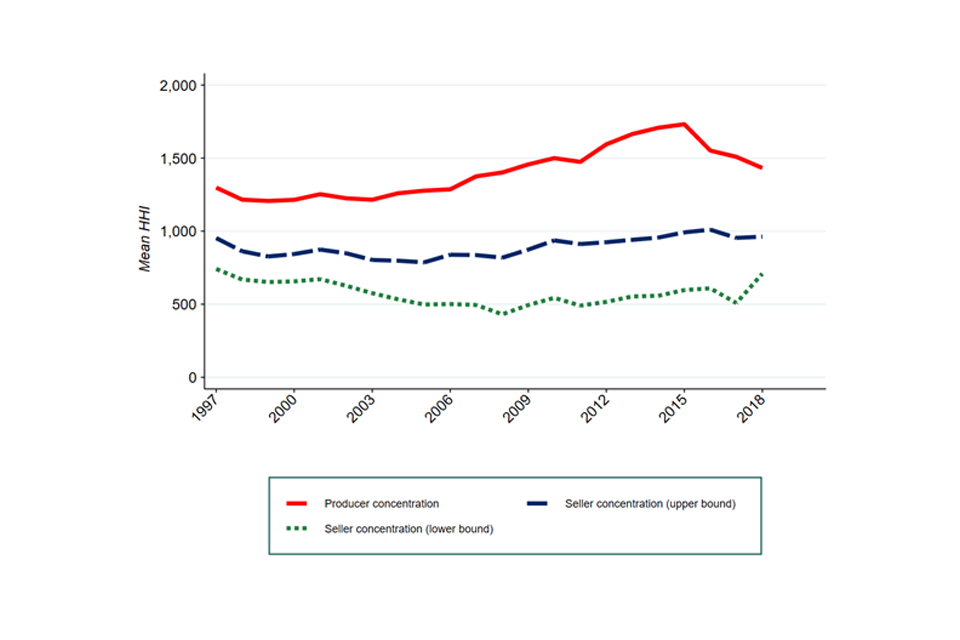

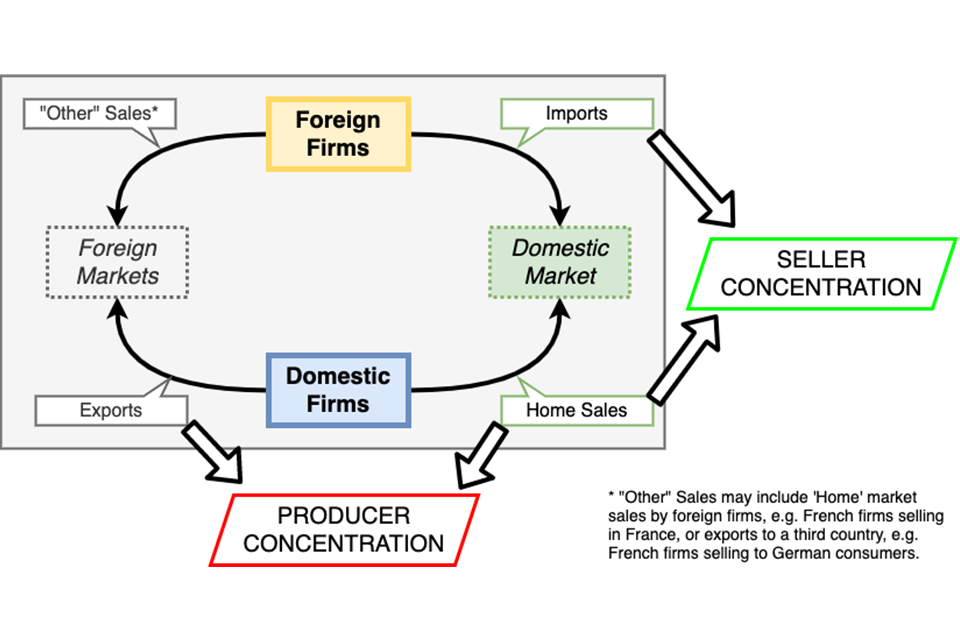

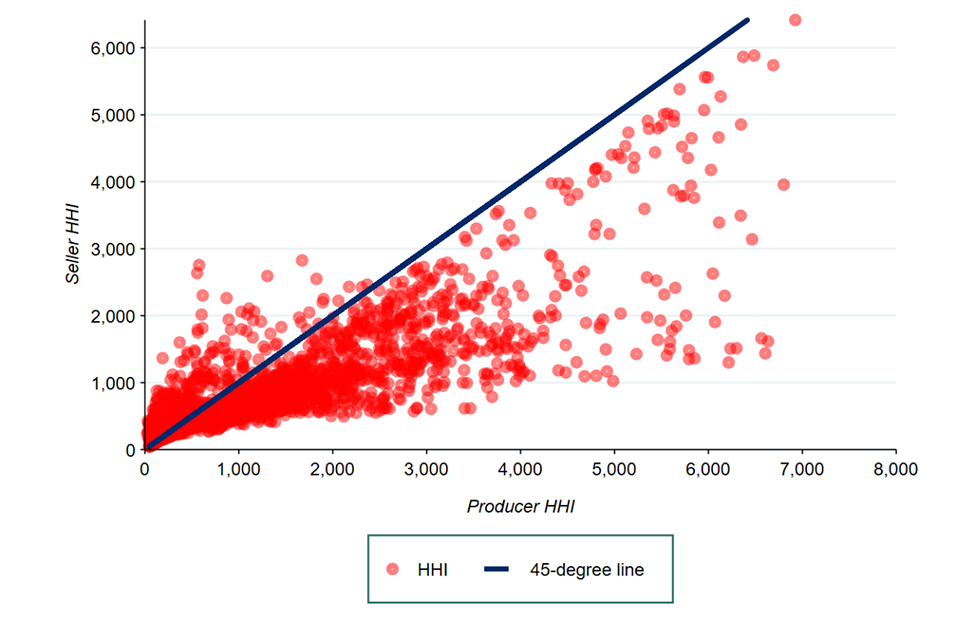

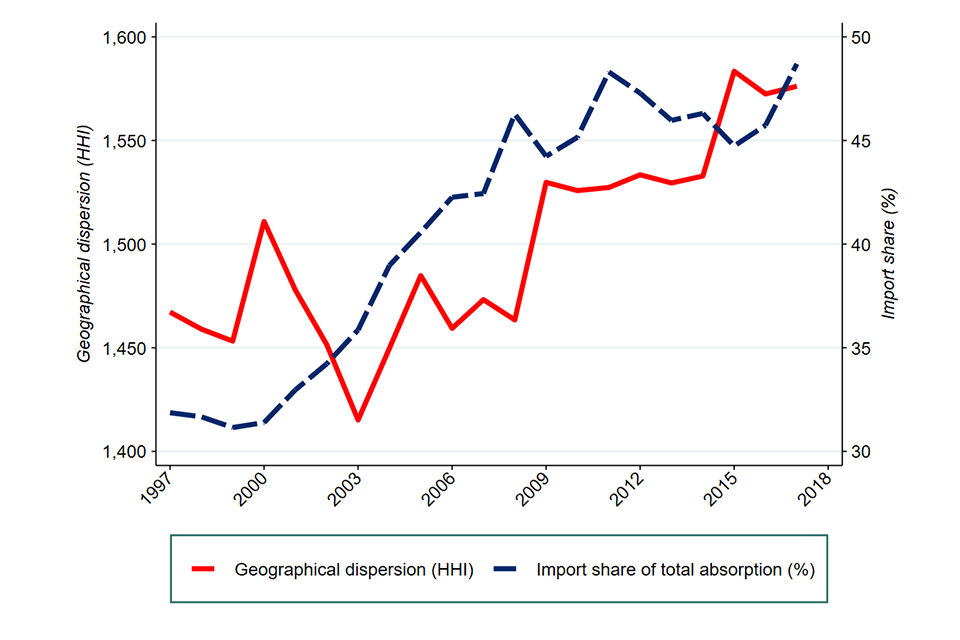

Adjusted concentration also considers how concentration is affected when international trade is accounted for. The standard data that is used for measuring concentration in the UK excludes imports into the UK and exports out of the UK. We have attempted to correct for this using the available trade data. This analysis, which relates to a sample of manufacturing industries only, is illustrated in Figure 6. The red line shows our standard measure of overall concentration, whilst the blue and green lines show the upper and lower bounds of our estimates of concentration once we take trade into account. The chart shows that overall concentration is lower when we account for international trade. This highlights the important role that international trade plays in contributing to keeping UK markets competitive. Whilst the effect seems significant at the aggregate level, it should be noted that the result will vary across specific industries. For instance, in industries where large volumes of imports come from a small number of overseas suppliers, accounting for international trade will tend to increase measured concentration.

Figure 6: The effect of trade on measured concentration [footnote 16]

Image description: 3 line graphs illustrating various measures of concentration between 1998 to 2019. The red line represents traditional measures of concentration, “producer concentration”. The dashed blue line and dotted green line represent concentration when measured from the seller’s perspective and illustrate upper and lower bound measures respectively.

Effective competition is driven by customer choice. It is the act of choice that sends signals to firms about what customers want and makes them compete to deliver it. If consumers are not able to identify or access the best value deals, or if firms do not deliver on their offers, then competition will not deliver lower prices and better quality. In the worst case, firms may instead compete to mislead or exploit customers. For example, if some firms in a market operate by presenting up front prices which do not include “hidden extras” this can undermine firms with a more straightforward presentation of prices to consumers. This ‘drip pricing’ has the capacity to significantly distort competition and harm consumers. Understanding consumers’ experience of markets is therefore critical to any rounded assessment of the state of competition.

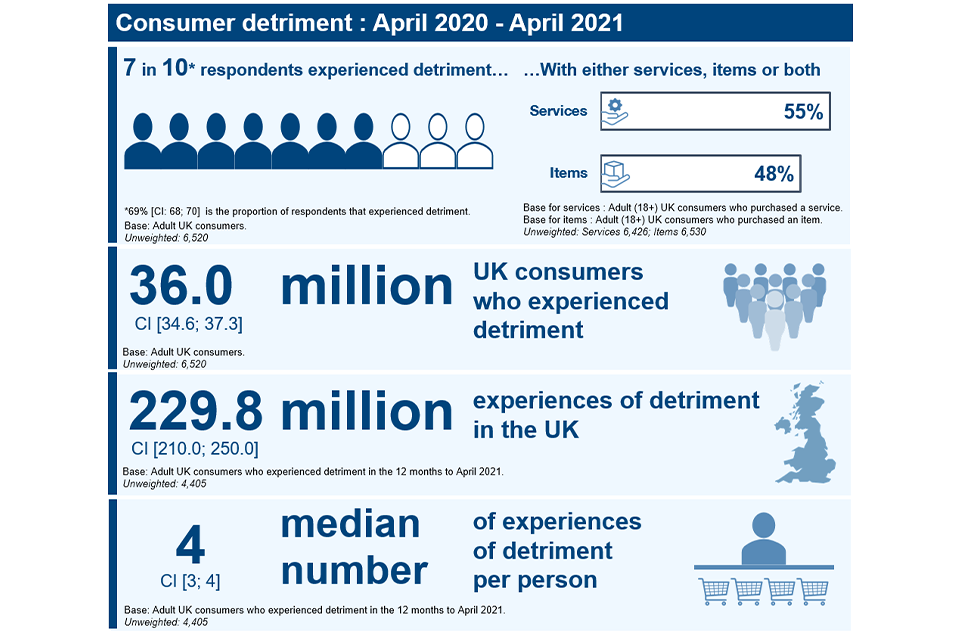

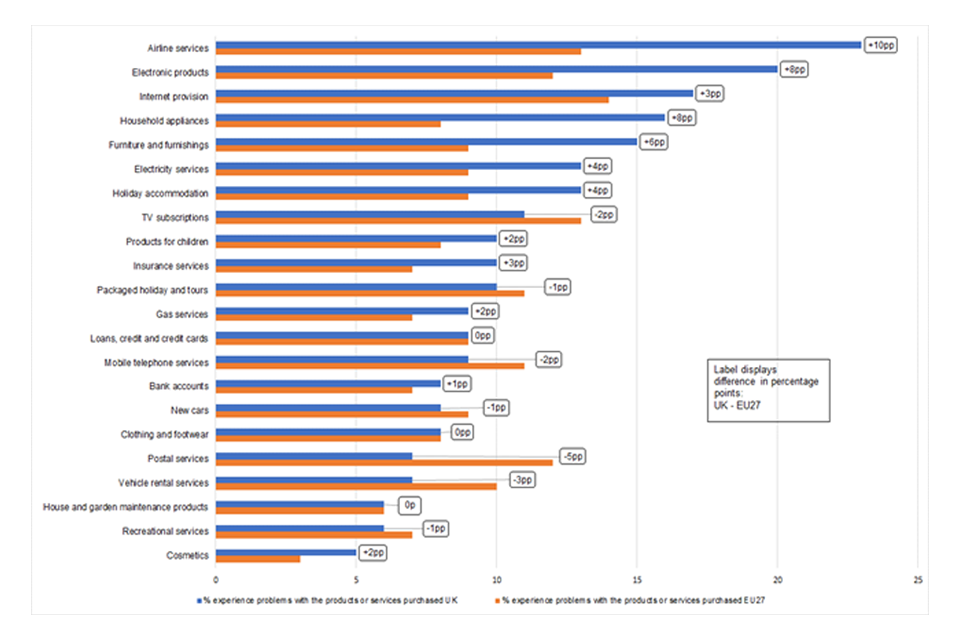

In the consumer survey evidence section, it analyses a number of surveys, including the results of the recently-published BEIS Consumer Protection Study 2022 (CPS), which asks consumers about problems they have experienced with goods and services they have purchased.[footnote 17]

-

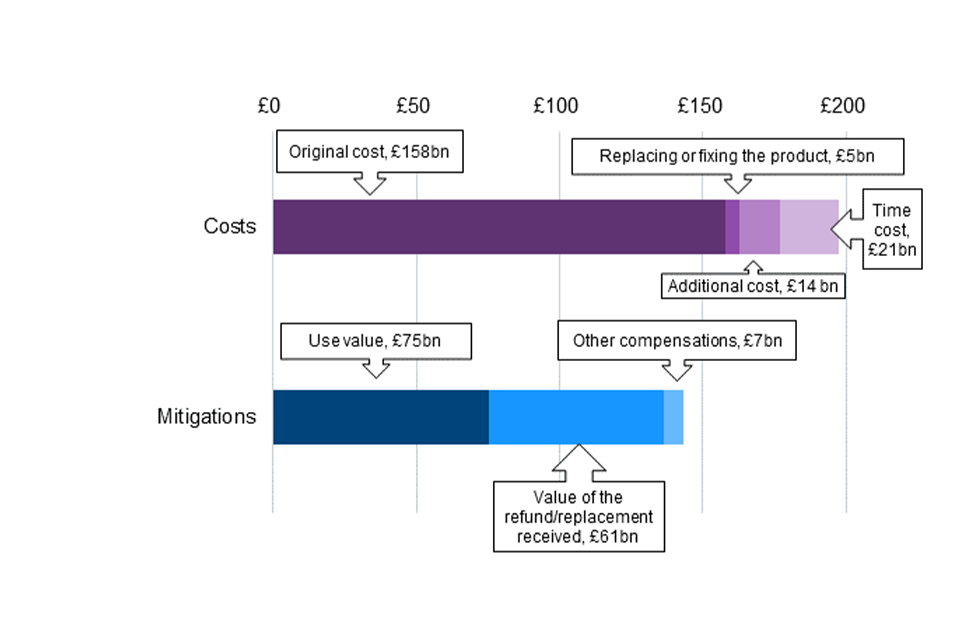

In the period covered by the CPS (the year to April 2021), most consumers (around 7 in 10) experienced some sort of “detriment” or “harm”. This is caused by a problem with something they had bought or used. Problems were more frequently encountered with services than with goods. In addition, the average cost to consumers of these problems is higher with services (£41) than with goods (£14).

-

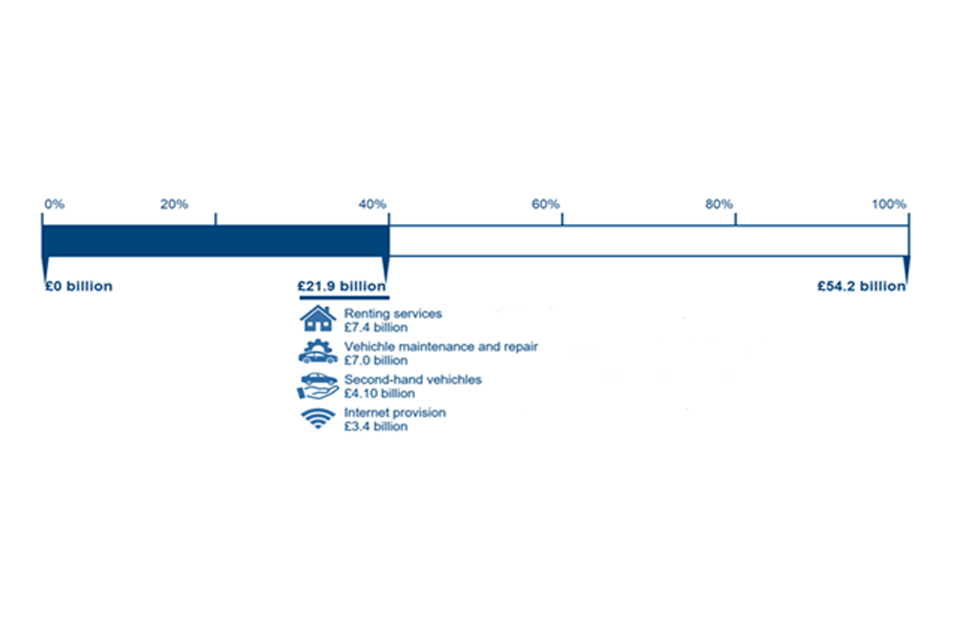

The study estimates that the total net value [footnote 18] of consumer detriment was £54.2bn, two-fifths of which comes from just 4 sectors: renting services, vehicle maintenance and repair, second-hand vehicles, and internet provision.

-

Detriment is more widespread and more costly among younger people, and among those in more difficult financial situations.

-

A separate survey[footnote 19] on UK customer satisfaction shows that over the same period, the level of problems consumers have encountered had risen compared to earlier periods. However, satisfaction with complaint handling has also risen over this period.

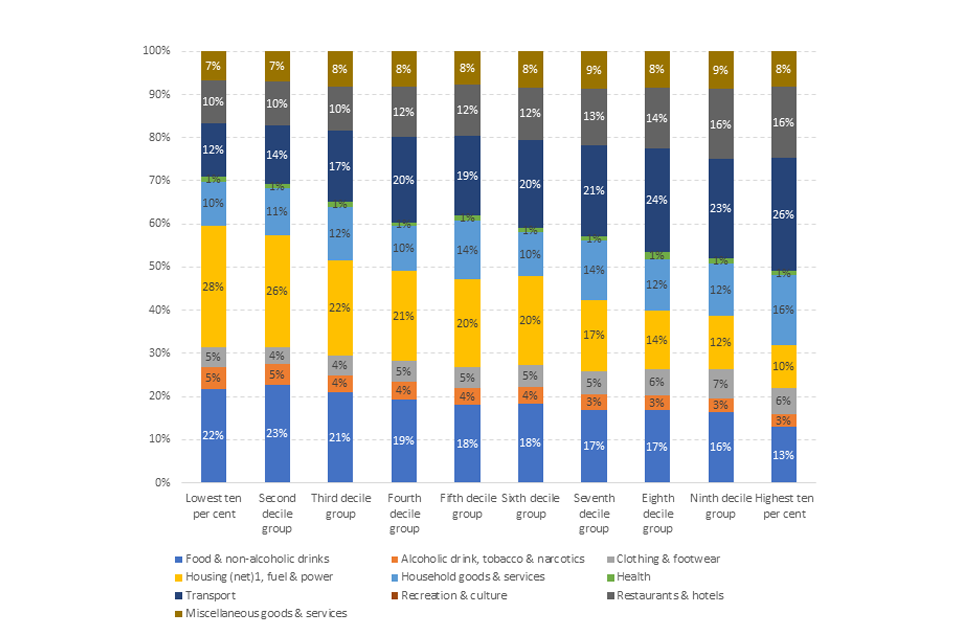

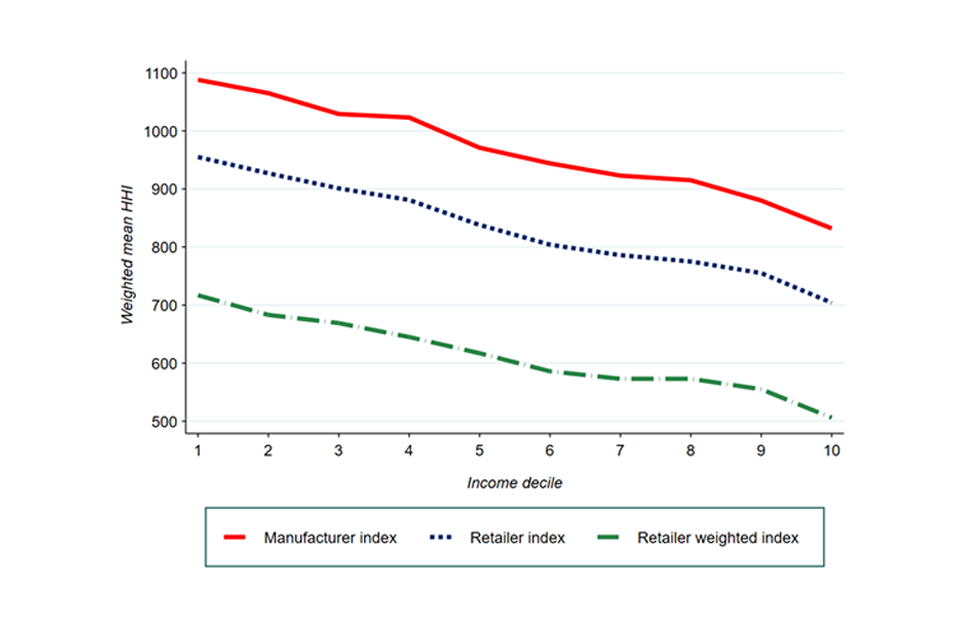

In the concentration, industry structure, and distributional impacts section, it considers another aspect of the consumer experience: the extent to which those on low incomes are more likely to buy in markets in which there are fewer supplier and less choice. Overall, we find that households on lower incomes are significantly more likely to consume goods and services produced in more concentrated industries. This is because markets for essential goods and services (which, for those on low incomes, account for a higher proportion of expenditure) tend to be more concentrated. This is illustrated in Figure 7. It shows that whilst the average concentration faced by the 10% least well off consumers is about 1,100, this drops to less than 900 for the 10% most well off consumers.

Figure 7: Expenditure on products and services by households[footnote 20]

Image description: Line graph illustrating the relationship between the average concentration or weighted HHI each household by income faces. The line is downward sloping, illustrating that households in the highest income decile experience a lower weighted HHI than households in the lowest income decile.

Spotlight on the COVID-19 pandemic

Analysis of the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic is hindered by a lack of available data.[footnote 21] The available data suggests very little change in concentration since 2019, while measures of profitability and markups show a slight decline. Given the lack of data, it is too early to draw any firm conclusions about any long term impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on concentration or profitability.

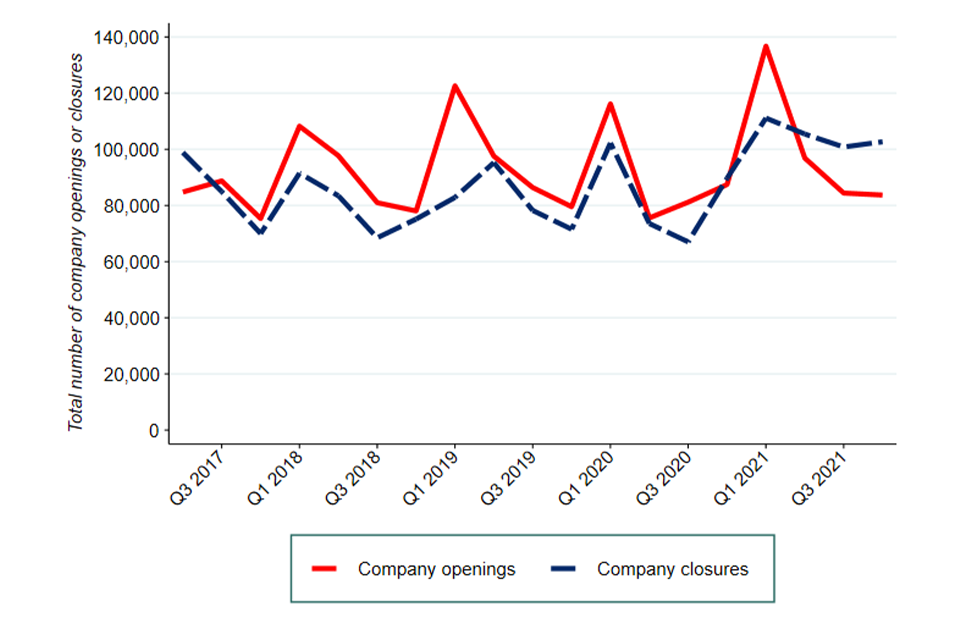

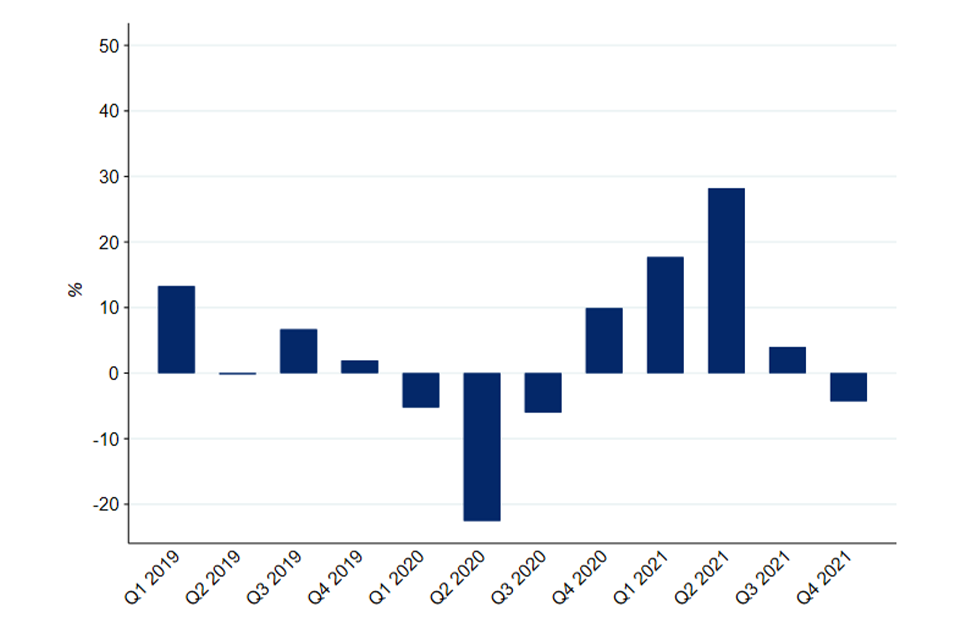

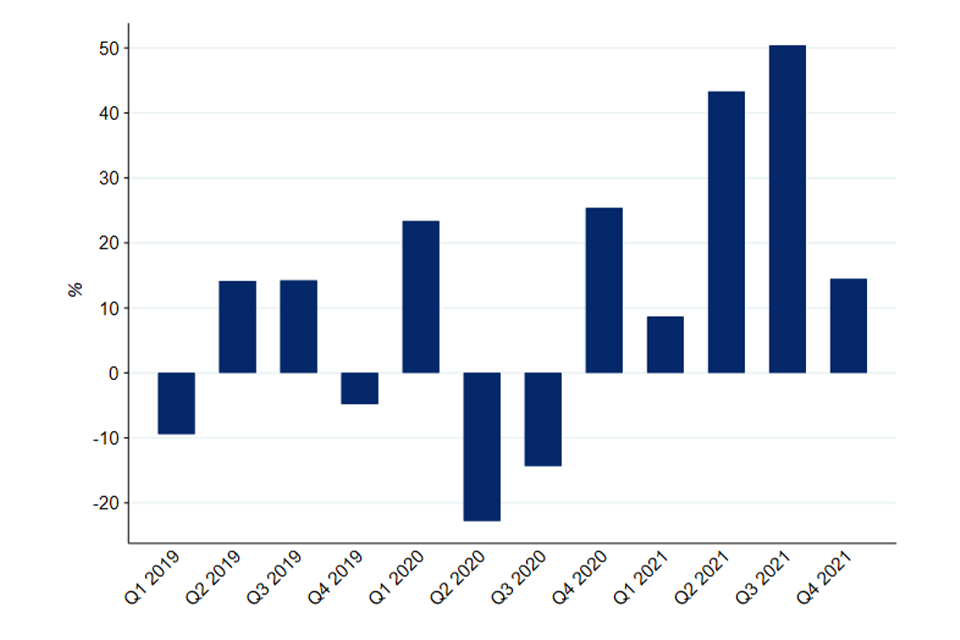

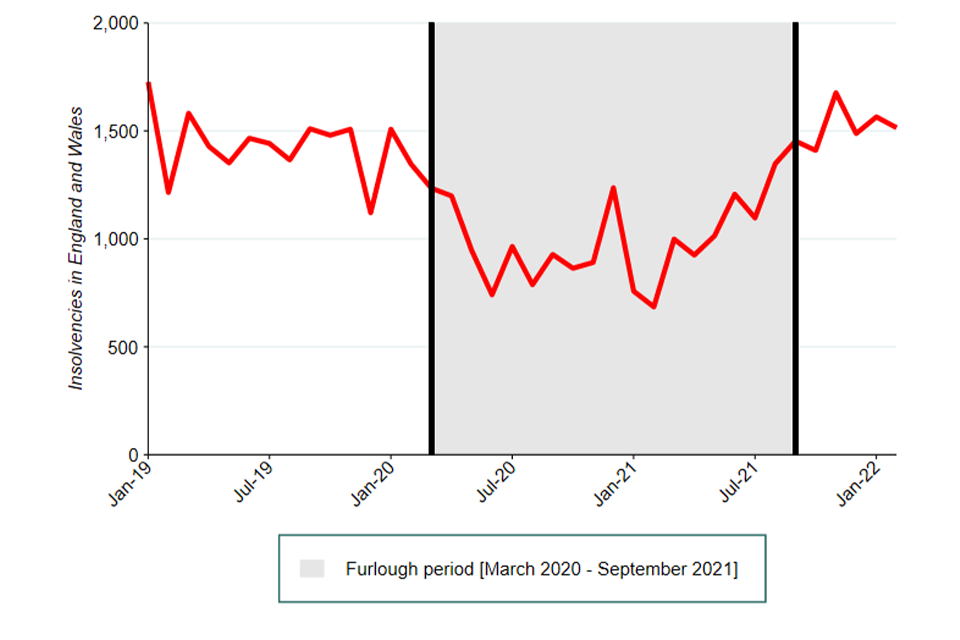

Other dynamic indicators show that, while there was an immediate fall in new businesses being created after March 2020, there was also a reduction in business closures. This was subsequently followed by a rapid increase in business creation (and closures). This pattern is not usually observed during economic slowdowns, and may be due to the extraordinary levels of financial support provided by government, and to regulatory forbearance in respect of insolvencies and HMRC debt collection. More recently, there is tentative early evidence of a rise in business closures as the major elements of government support are withdrawn.

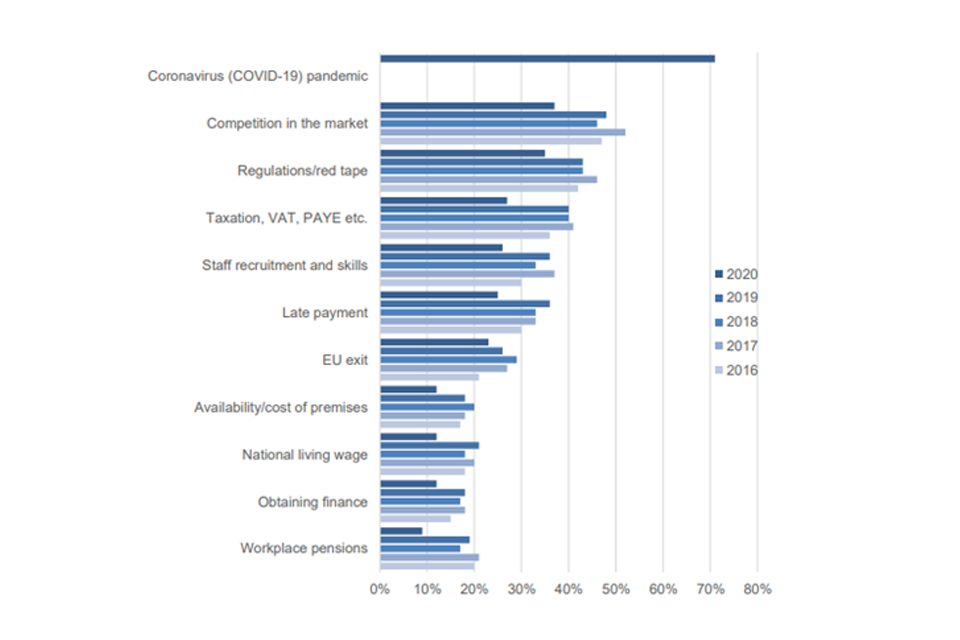

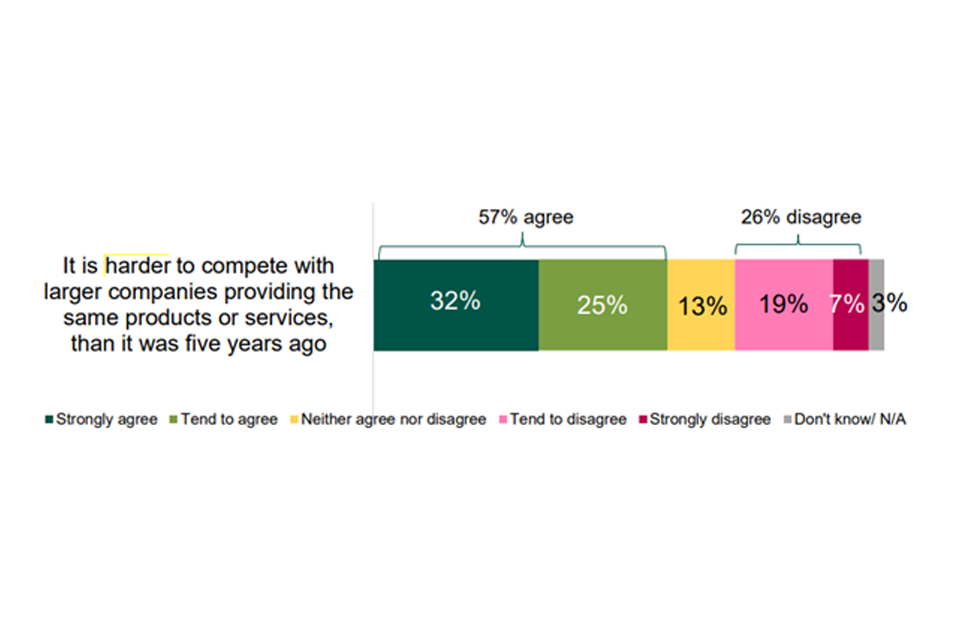

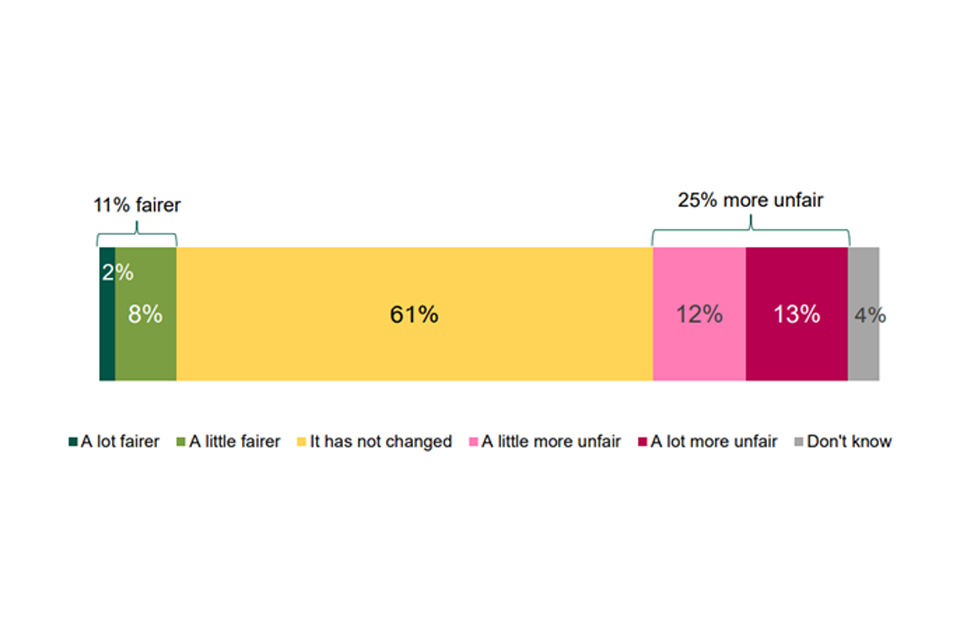

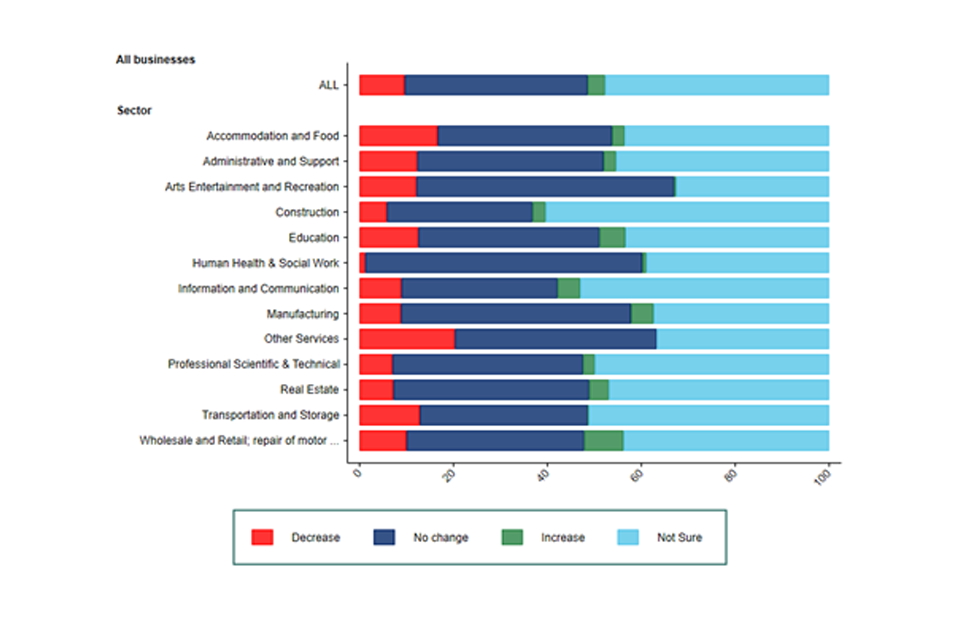

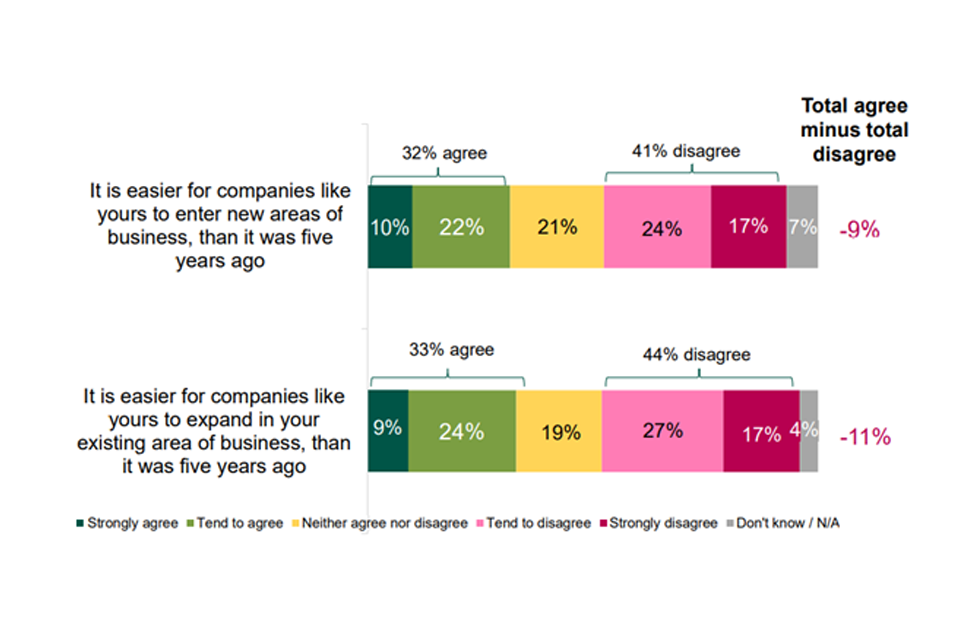

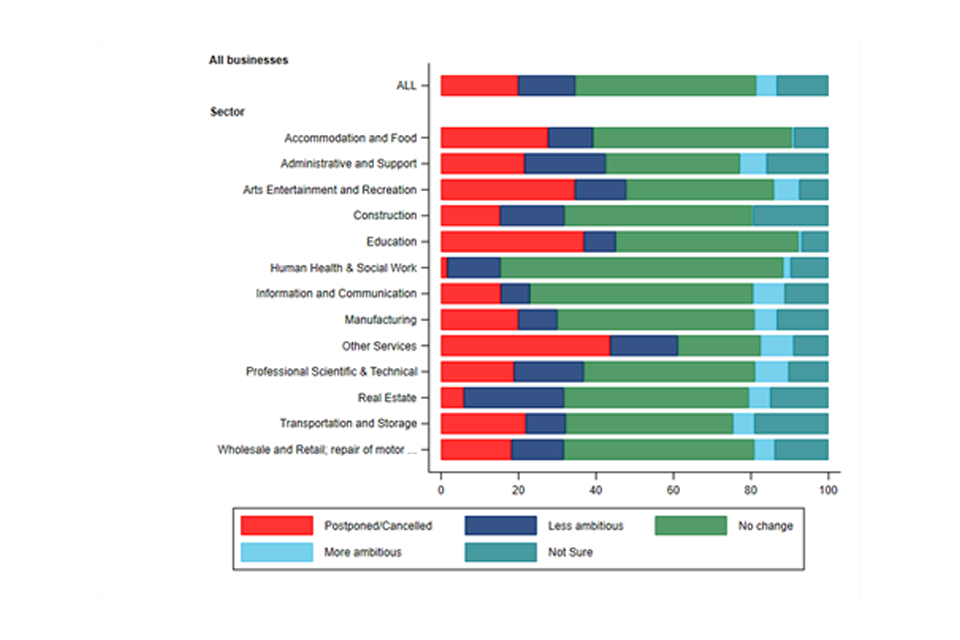

Evidence from surveys of business owners (discussed in business survey evidence) unsurprisingly indicates that the pandemic was a significant barrier to growth, with over a third of businesses with expansion plans saying that these were postponed, cancelled or scaled back as a result.[footnote 22] Businesses also report that innovation levels have been affected by the pandemic, with a fall in the proportion of businesses reporting either product or service innovation in 2020 compared to 2019 (though levels remained higher than in 2018).[footnote 23]

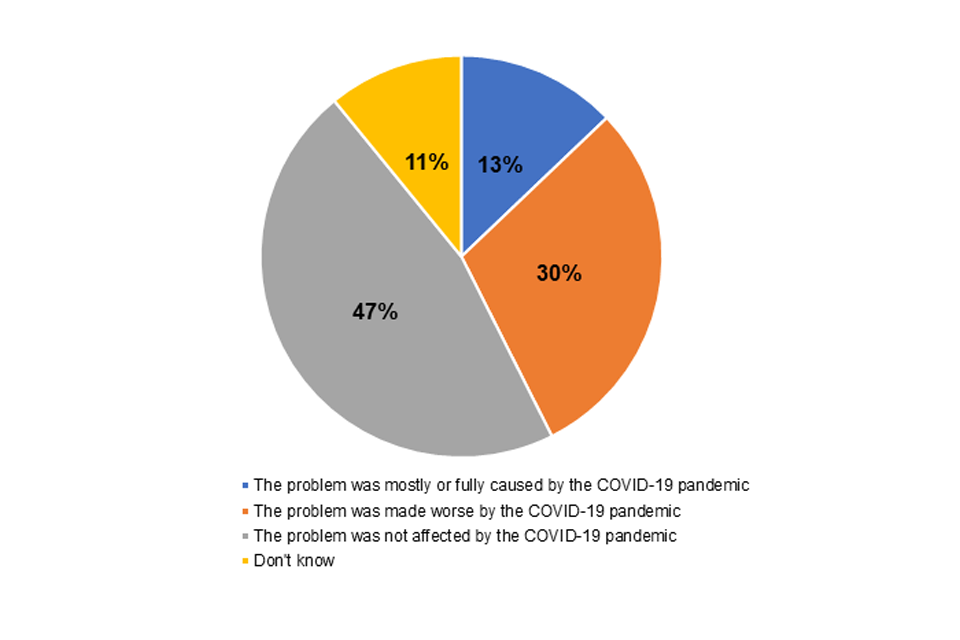

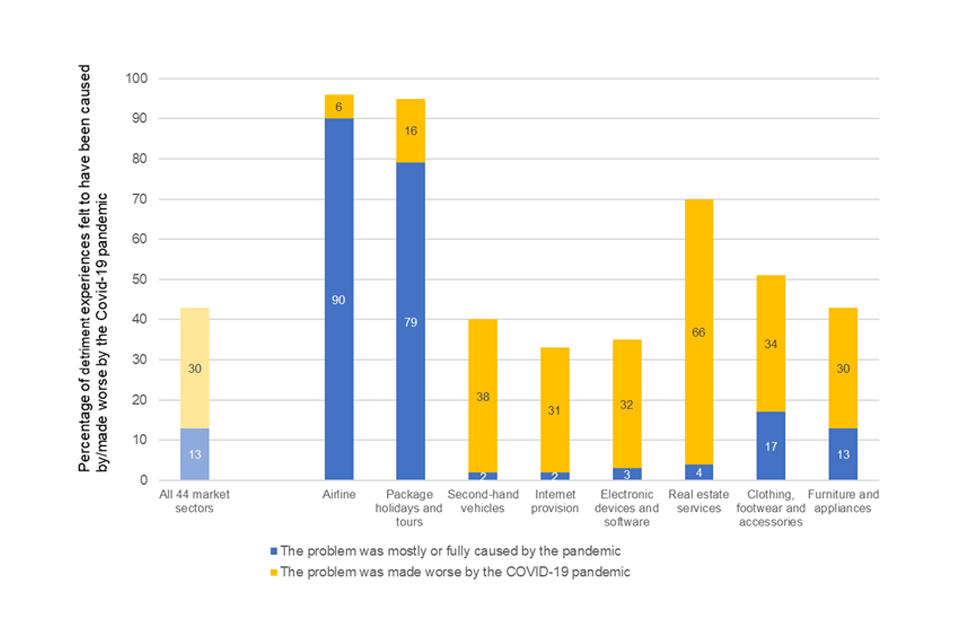

From the consumer perspective, the pandemic is likely to have affected the level and pattern of detriment in markets. The CMA received tens of thousands of complaints about difficulties consumers had experienced in obtaining refunds for travel and holidays that were cancelled because of lockdown restrictions.[footnote 24] This is borne out by evidence from the BEIS Consumer Protection Study 2022 (Consumer survey evidence), which found ‘airlines’ and ‘package holidays and tours’ to be the sectors in which consumers were most likely to have experienced detriment. In over 90% of cases, consumers reported that the problems they had experienced in these sectors had been caused or made worse by the pandemic.

Overall, consumers reported that £7.7bn of the detriment they experienced (14% of the total) had been caused by the pandemic. A further £18.8bn (just over a third of the total) was linked to detriment that consumers said had been made worse by the pandemic.

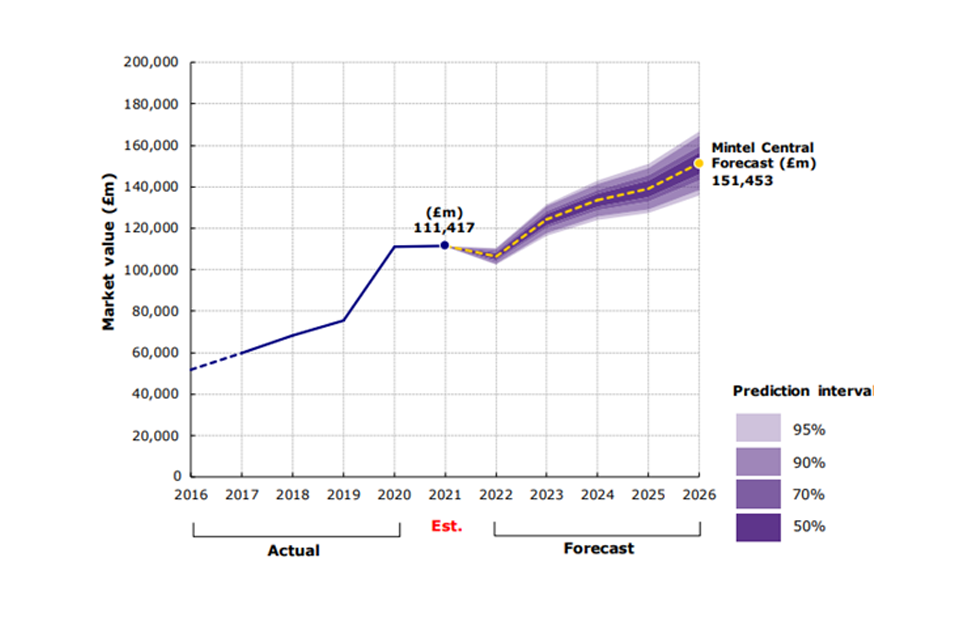

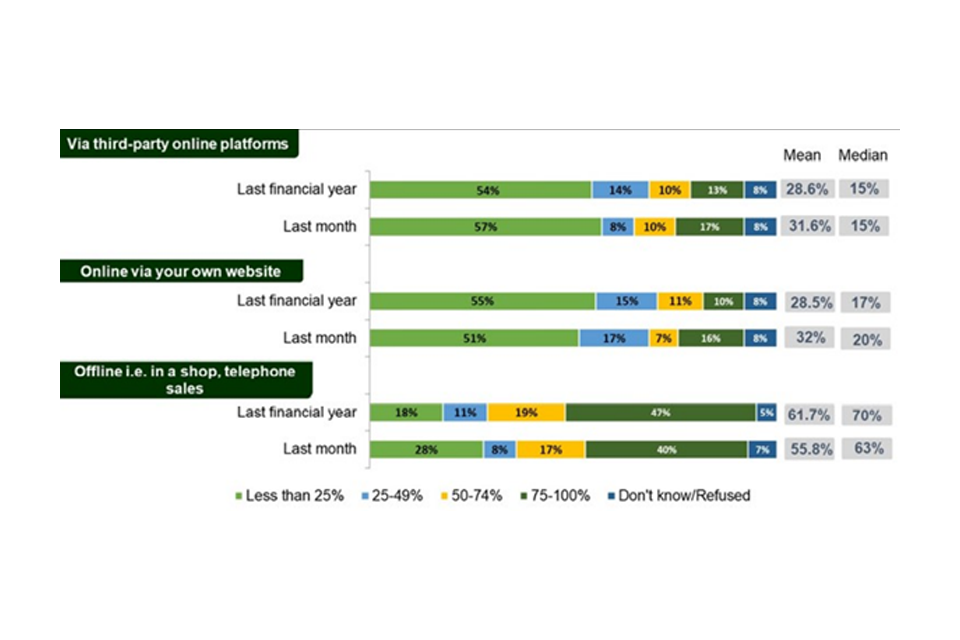

Unsurprisingly, the pandemic accelerated the trend toward online shopping. Whilst all retail categories saw increases in online spending, online grocery saw one of the largest increases (after DIY), with spending up an estimated 75.2% between 2019 and 2020 and grocery sales accounting for a fifth of all online spending, the highest proportion on record.

Spotlight on digital markets

The digital revolution has brought huge benefits to consumers. And it has enabled small firms to reach out beyond their local market and access customers around the world. In the process, it has disrupted business models, from broadcasting and music, to taxis and food delivery. Digital markets have huge potential to continue to improve our lives and living standards and to play an important role in the post-pandemic recovery. But to deliver those benefits, they need to stay competitive.

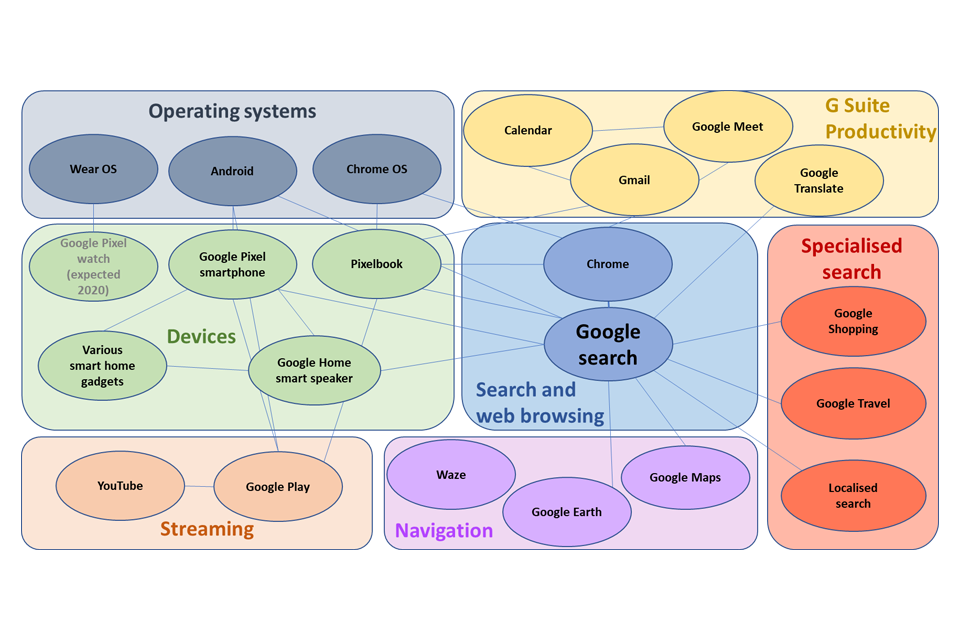

The data that we have used in this report does not capture indicators of competition in these digital markets. We have therefore relied on our published analysis of some of these markets. Competition in the digital economy summarises some of the key findings on competition in digital markets made by the CMA’s market studies into digital advertising and mobile ecosystems.

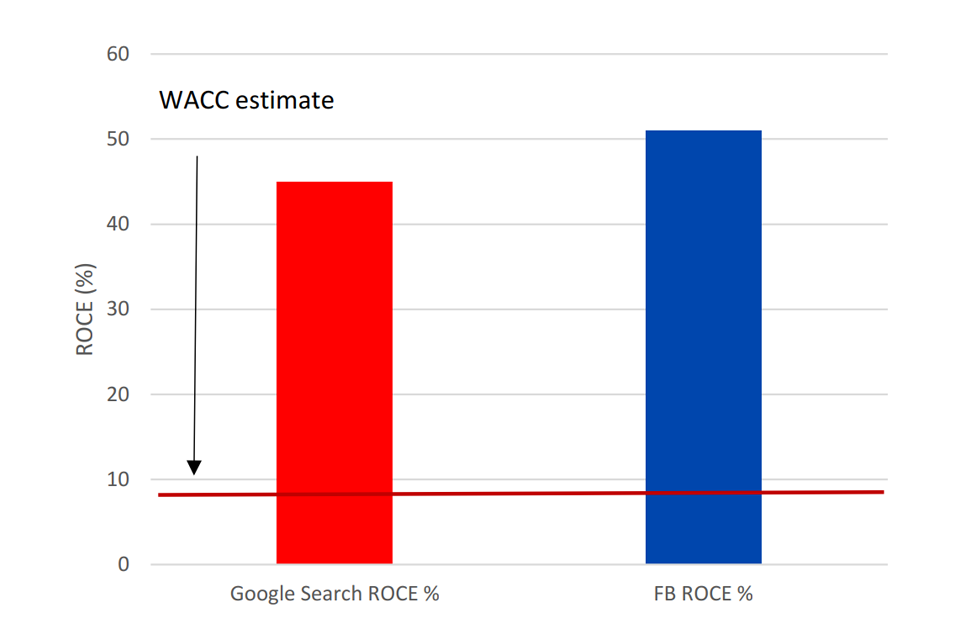

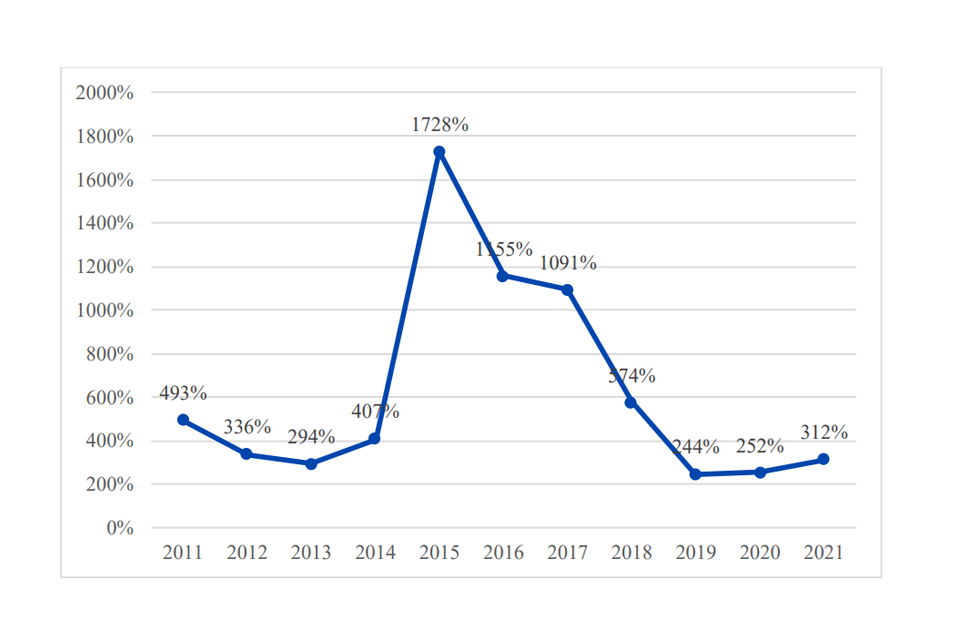

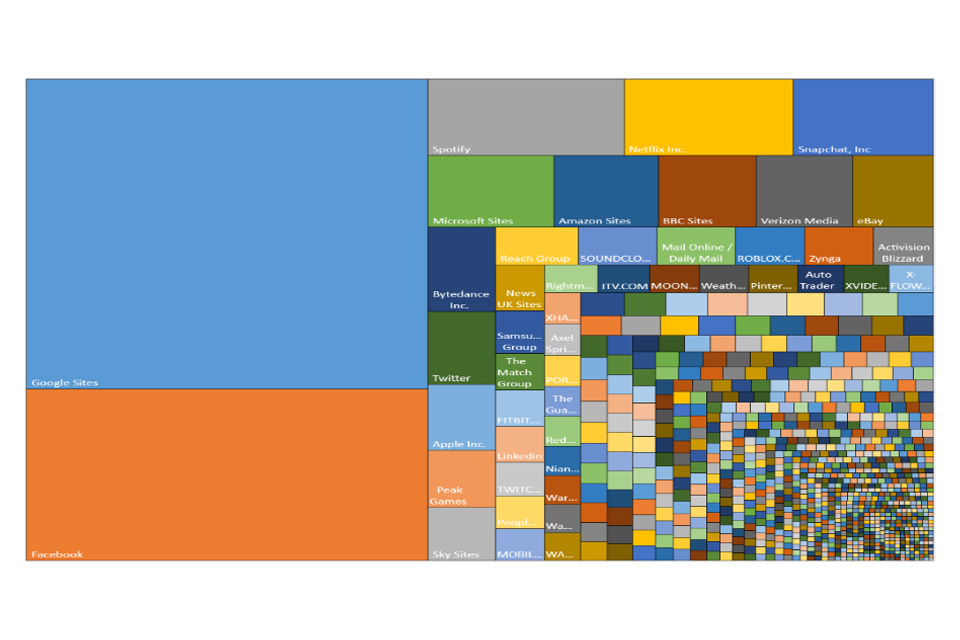

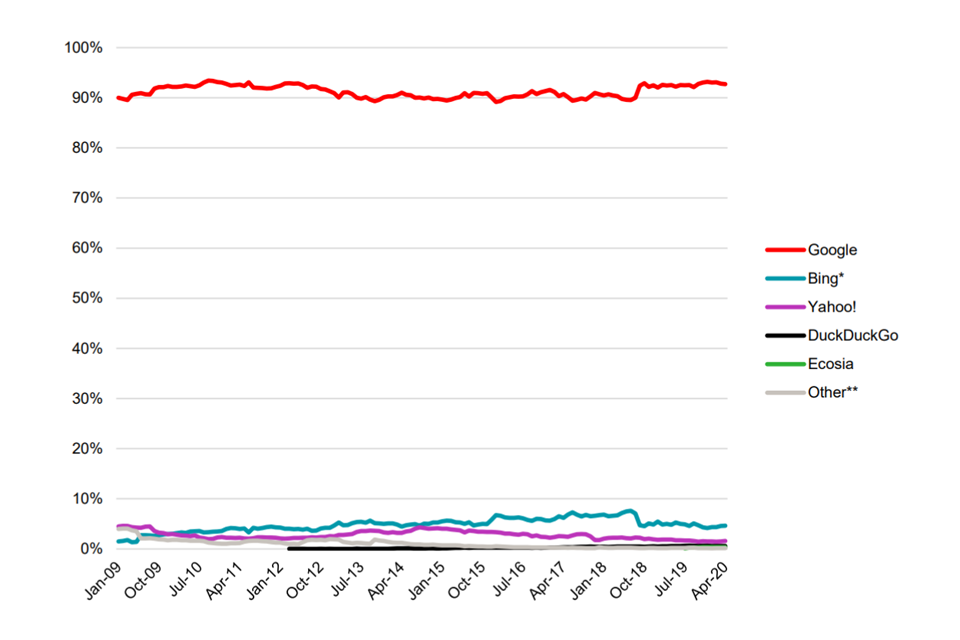

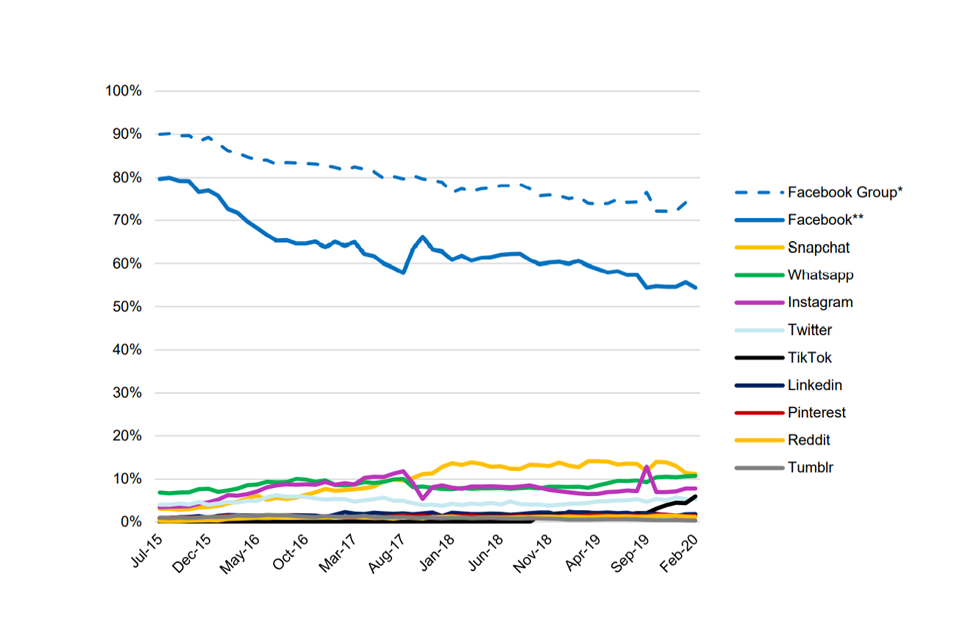

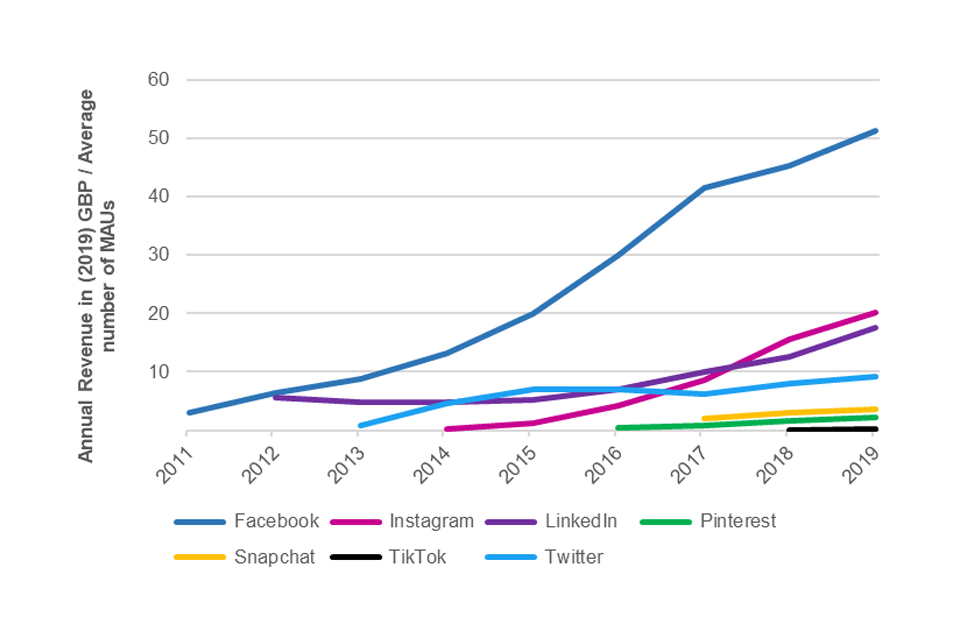

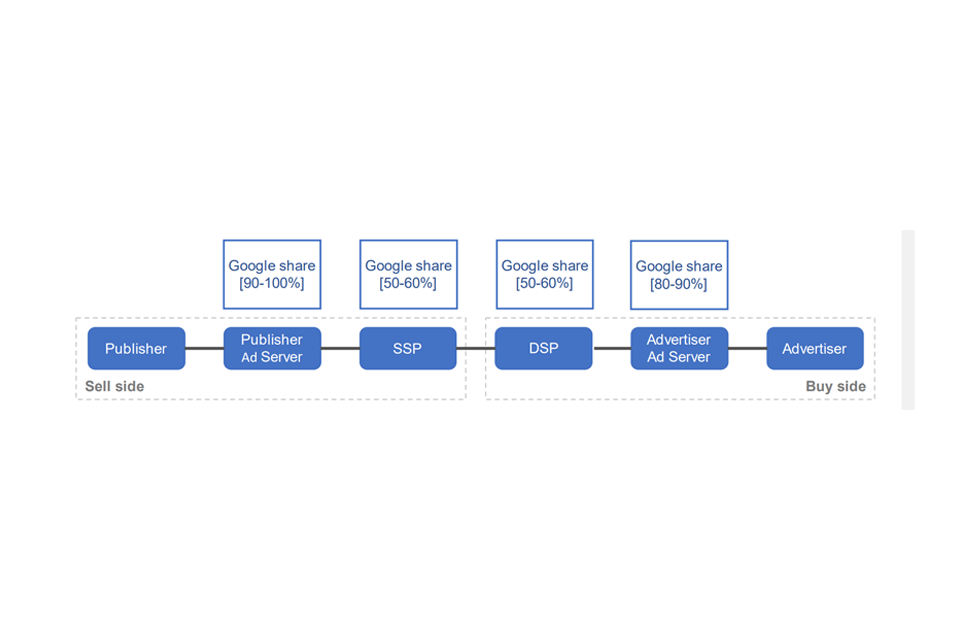

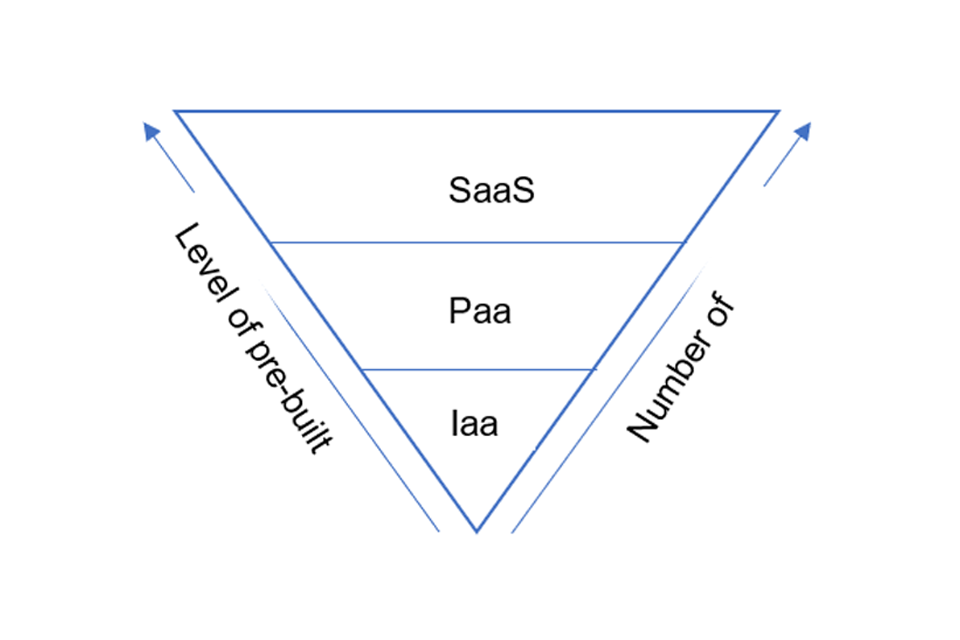

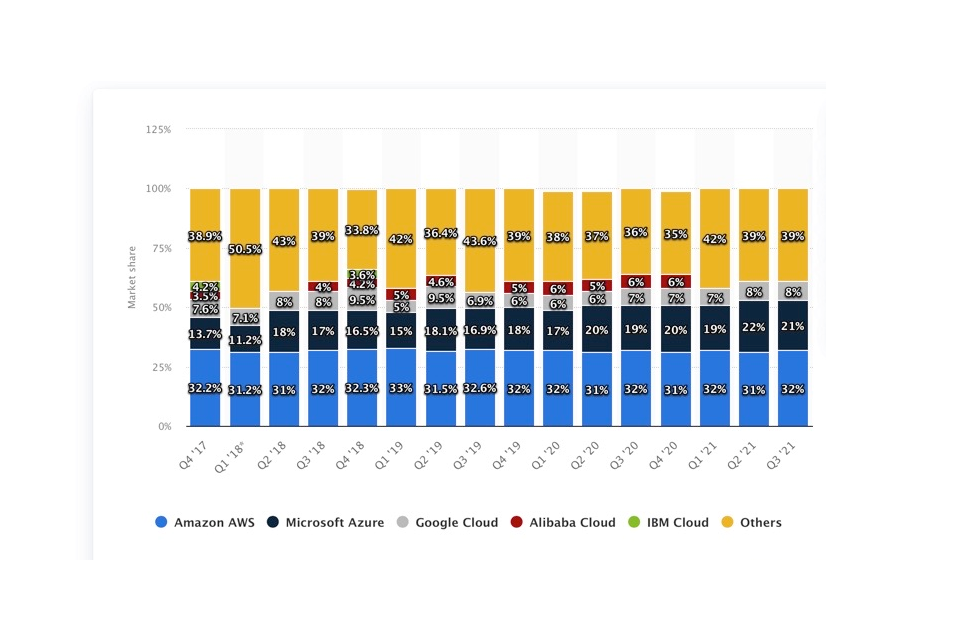

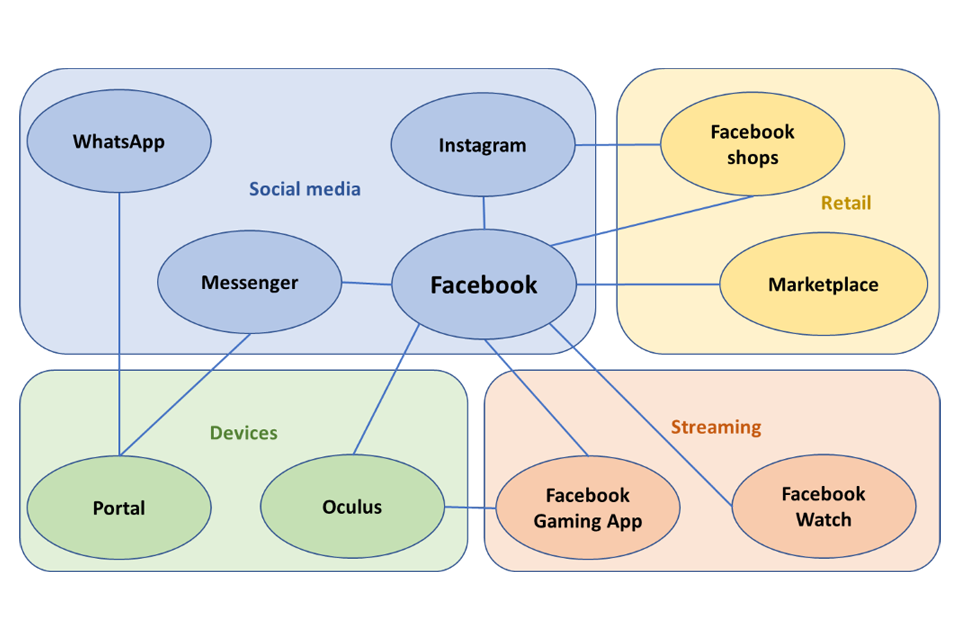

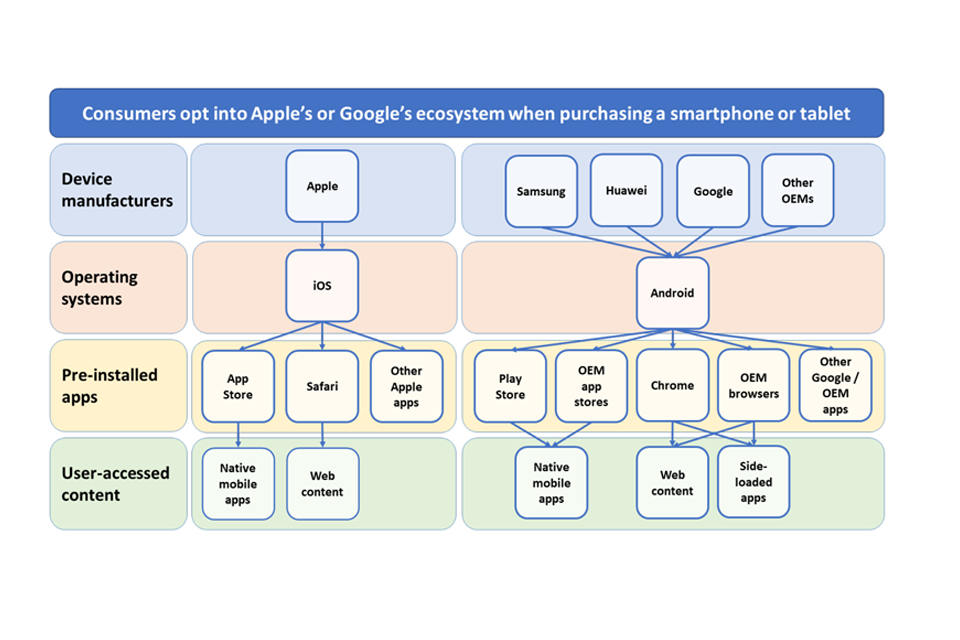

Google, Meta and Apple are highly profitable and have a very high market share in the markets in which they operate, a situation that has endured for many years. On both static and dynamic measures of competition, these markets therefore appear to perform poorly.

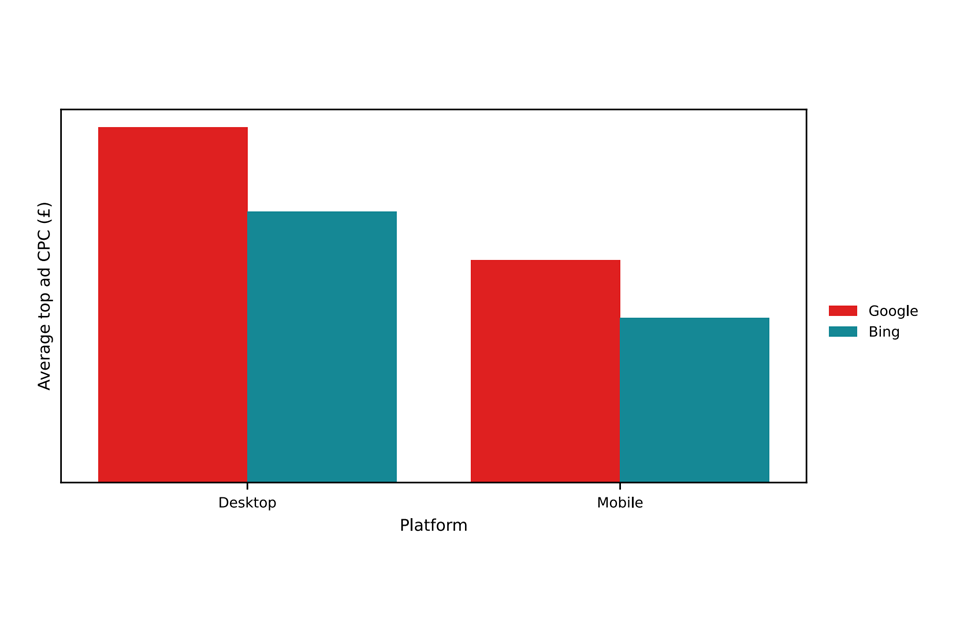

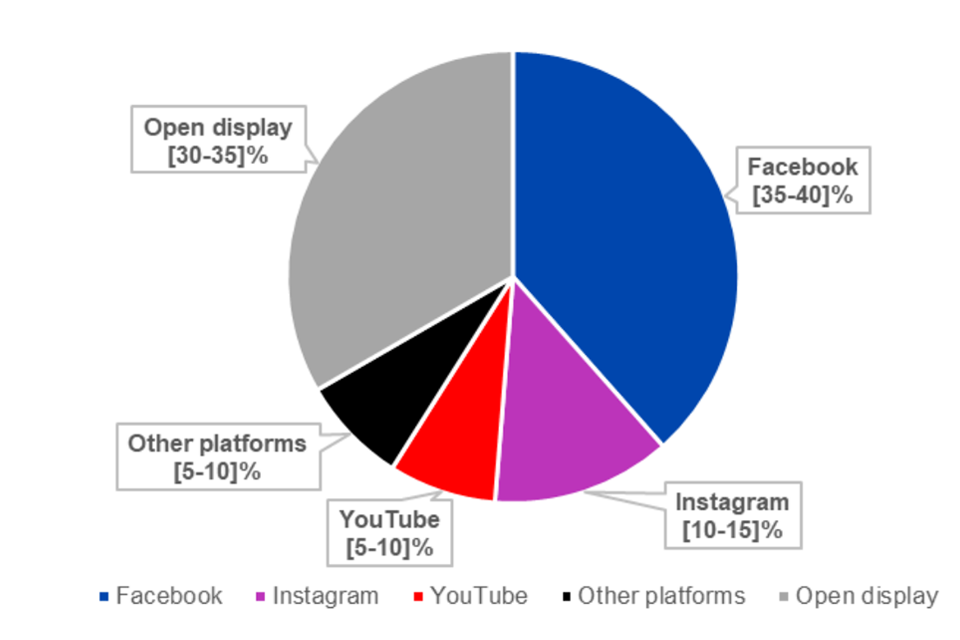

Weak competition in search and social media markets risks leading to reduced innovation and choice, as well as to consumers giving up more data than they would like. Google and Meta’s (Facebook’s)[footnote 25] strong position also means that businesses are more likely to pay more for digital advertising than they would in a more competitive market, a cost that we would expect ultimately be reflected in higher prices for consumers.

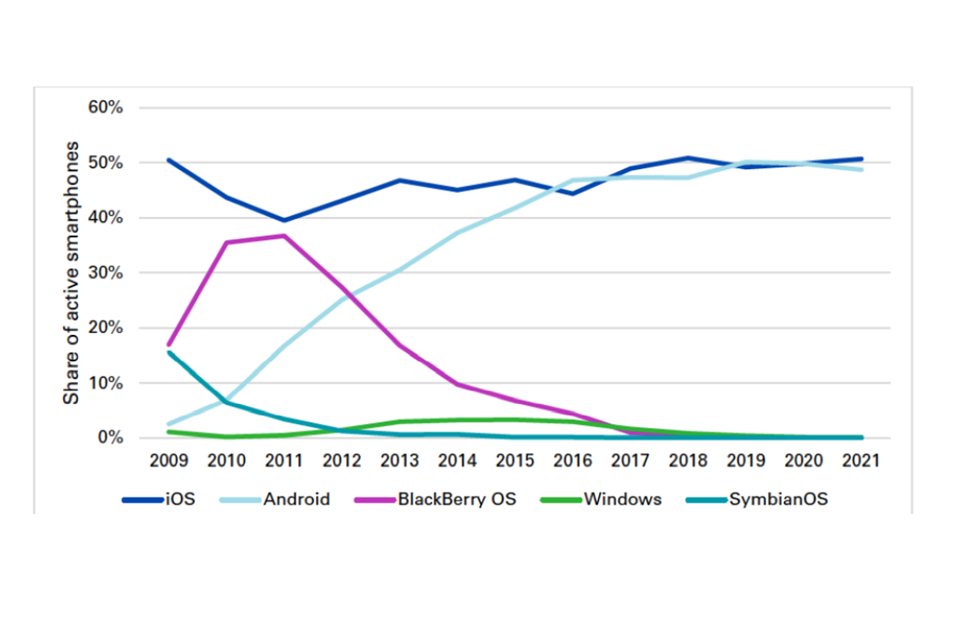

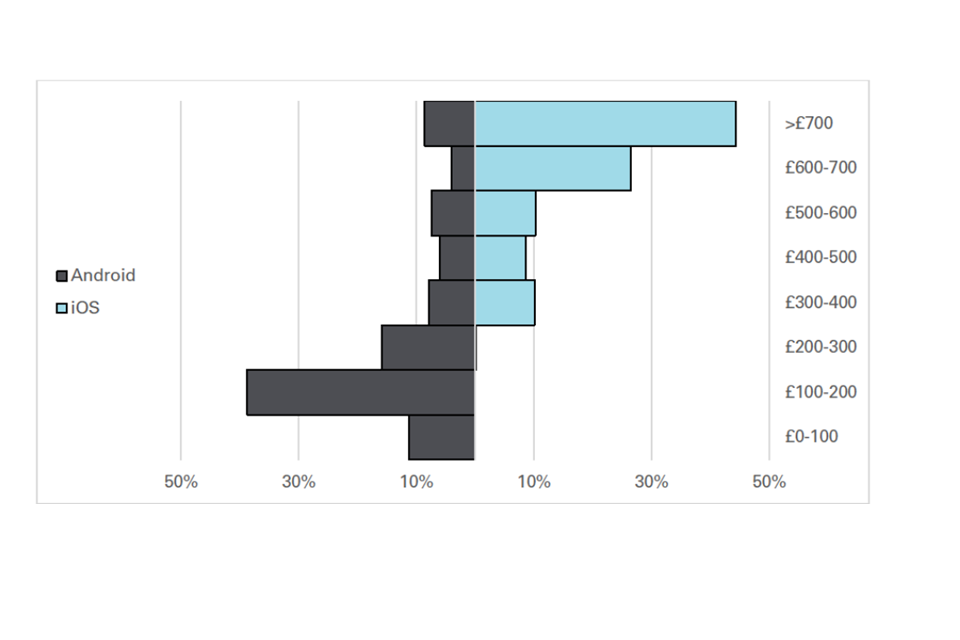

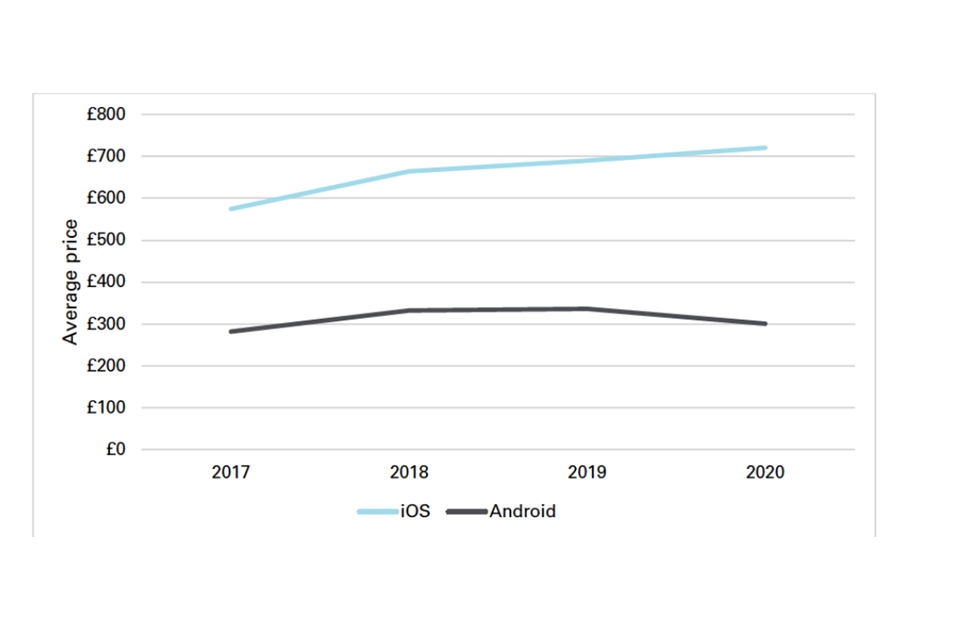

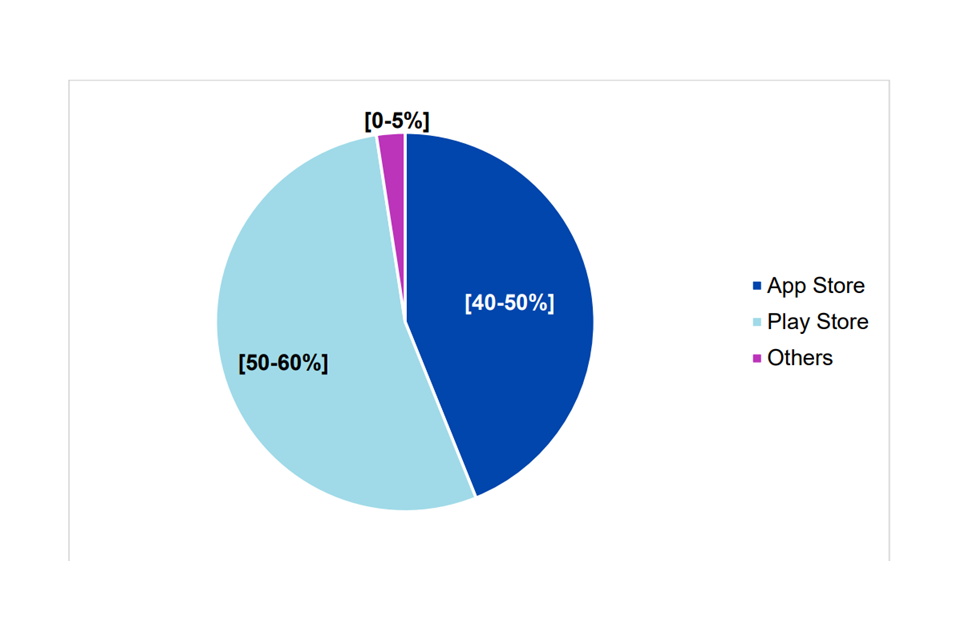

When consumers buy a smartphone, they effectively enter into one of 2 mobile ‘ecosystems’ – controlled by Apple or Google – that determine how a range of online content is delivered to them. The result is that the provision of a range of smartphone services, including operating systems, app stores and mobile browsers, is highly concentrated. Competition is further weakened by the difficulties users encounter in switching between Apple (iOS) and Google (Android) devices. All this may limit innovation and choice, and lead to consumers paying more for app purchases and subscriptions than in a more competitive market.

Implications

Competition has a key role to play in supporting UK productivity and growth. Given evidence that competitive pressure may have been stronger in the past than it is today, it is natural to ask what might be done to further strengthen competition. The objective of this report is to inform debate and public policy, rather than to propose specific interventions. However, the evidence in this report, combined with other recent work and analysis undertaken by the CMA, point towards a number of important areas of focus.

Competition policy and enforcement: the CMA has a key role to play, particularly post-Brexit, in creating the conditions where the best businesses can thrive, and where consumers can shop with trust and confidence. The CMA’s annual plan sets out its priorities for the year ahead.

Reform of the framework: as the CMA has set out, and as government has recognised, there is a need to update the legislative framework – including the CMA’s tools and powers – to make it fit for the modern economy. The CMA supports the plans by the government to reform competition and consumer protection law to make it swifter and more effective, and to introduce a new pro-competition regime for the most powerful digital platforms.

Pro-competitive regulatory policy: well-designed regulation can support consumer choice and competition, especially in markets where data is important.[footnote 26] And it can support consumer trust, confidence and engagement, particularly in complex markets. The CMA welcomes the government’s plans to reform the framework for regulation,[footnote 27] and to hard-wire competition principles into regulatory decision making.[footnote 28]

Close monitoring of the impact of Covid-19 business support: as the exceptional support provided by government to business during the pandemic is withdrawn, it will be important to monitor the effects on markets and consumers. Firms leaving markets are an important part of the competitive process; but to the extent it leaves certain markets with a small number of powerful firms, there could also be a cause for concern.

Developing the analysis further

In addition to updating the existing analysis, we intend to include additional analysis in the next iteration of this report. As with this version of the report, much of this will be carried out in conjunction with academic advisors. This will potentially include the following areas:

Concentration metrics:

-

Estimating concentration measures at a more granular level in order to better approximate economic markets. Our analysis in this report is based on 4-digit SIC industries. As explained in concentration, industry structure, and distributional impacts, this is likely to represent a more aggregated level than what the CMA would normally define as an economic ‘market’. This could include refining our use of the existing data sets (for instance, through the use of data science techniques to match industries with how companies describe their own business in statutory directors’ reports and other filings) in order to more closely match SIC industrial categorisations to economic markets.

-

The data we use for estimating concentration metrics is recorded at a national level. We investigated the possibility of estimating concentration at a more local level, but the necessary data was not available. We intend to do further analysis on this issue in order to better understand how concentration varies regionally.

-

Our analysis shows how accounting for imports and exports significantly affects estimated concentration. However, our estimates remain imprecise, as shown by the gap between our upper and lower bound estimates in Figure 6 above. More granular data on firms’ levels of trade would allow for more precise estimates of the impact of trade flows (and changes in trade flows) on estimated concentration measures.

-

Further work to understand what factors drive the greater concentration faced by lower income households in essential goods and services markets. We consider this to be a particularly high priority piece of work.

Profitability:

-

The best methodology for estimating markups and profitability at a sector level is a highly debated topic in the economic literature. As the debate evolves, new or enhanced methodologies might become available. If one of the key drivers for competition policy is a belief that excessive concentration in markets can lead to excessive monopoly profits, then understanding trends in mark-ups, profitability and returns on capital in different sectors and industries is very important.

-

A focus on the most profitable firms, the markets they operate in, and their features could shed some light on the competitive conditions these highly profitable firms face. This is not to say that the CMA regards profitability as a problem per se, but rather that persistent profitability that does not attract new competitors may be an important signal of problem areas in the economy.

Common ownership:

-

The economic literature on common ownership is still developing. Our analysis of common ownership in adjusted concentration is still preliminary and there are various ways in which it could be extended and improved upon. For instance, our results are sensitive to the control thresholds used. Further sensitivities could be built in to explore how our results are driven by our definition of common ownership groups (including allowing for common ownership across industries and differentiating between horizontal and vertical ownership chains) and person of significant control.

-

In addition, further iterations of the data used in our analysis would allow for a study of changes in common ownership and adjusted concentration measures over time.

Effect of COVID-19:

-

The long run effect of the pandemic on competitive outcomes is clearly an important topic for further research. The next iteration of this report should look at this issue.

-

The BEIS Consumer Protection Study 2022 provides valuable evidence on the experience consumers are having in markets and the problems they encounter. The reference period for the 2021 survey is April 2020 to March 2021 - the peak of the Covid-19 pandemic - and the findings were heavily influenced by this. A further wave of the survey is recommended to understand the level of consumer detriment now that the UK is emerging from the worst economic impact of the pandemic. It will also be particularly important to understand consumer detriment levels considering recent increases in the cost of living for UK consumers meaning that the impact of any detriment experienced may be greater than in previous years.

Introduction

The competitive process provides incentives for firms to keep prices down and to keep quality and service standards up: in short, to win business by making the best offer to consumers that they can. In turn, this contributes to economic growth and productivity. The firms that serve their customers most effectively and are most efficient in terms of how they run their business, can be rewarded through winning market share from their competitors.

Free and fair competition, by incentivising firms to innovate, to improve productivity and to keep prices lower, is therefore essential in providing consumers with better deals and new goods and services while also contributing to higher real wages across the economy.

Following the CMA’s first publication on the state of competition within the UK economy[footnote 29], the Chancellor of the Exchequer and the Secretary of State for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy asked the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) to deliver assessments on competition across the UK economy on a regular basis.[footnote 30]

This commission from government asks that the report should be an authoritative, accessible and transparent source of public information on how competition is evolving across the UK economy. The ambition is that this will also provide both the CMA and government with information to better target their respective resources and tools towards improving competition in the UK.

Competition and the pandemic

As the UK begins to return to normality after the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic (the pandemic), an assessment of the state of competition is now more important than ever. The economic environment may discourage business entry and expansion and lead to an increase in business closures thus placing competition under strain. We look in detail at some of the dynamic indicators of competition in other indicators of competition and the extent to which any effects of the pandemic can be seen in the most recent evidence.

The pandemic has also brought the reliance of the UK economy on international supply chains into focus. We discuss the effects international trade can have on competition as importers can provide competition to domestic producers,. This is discussed in further detail in adjusted concentration.

Competition drives productivity

The UK’s weak productivity growth is well known, so much so that the 0.3% average annual increase in UK labour productivity (measured as output per hour) since the financial crisis was named Statistic of the Decade by the Royal Statistical Society in December 2019.[footnote 31] It had averaged 2.3% in the decade prior.

By comparison, the UK’s level of productivity has been lower than that of other advanced economies since the 1960s. The UK’s level of productivity is more than 20% lower than other major advanced economies such as the US, France and Germany. Productivity growth across the G7 [footnote 32] averaged 0.8% since 2008 (compared to the 0.3% in the UK). There is also wide variation in productivity within the UK. As measured by output per hour, the only 2 areas with average levels of productivity above the UK average in 2018 were London and the South East.[footnote 33]Recent publications by the ONS offers a more nuanced picture.[footnote 34]

The causes of this weak productivity are numerous and often complex but improving it is a major government and public priority. In the long term, productivity growth remains the only path to sustainable economic growth and rising living standards.

One mechanism to help tackle the UK’s weak productivity is boosting competition. There is strong evidence that competition drives productivity growth.[footnote 35] It does this in 3 main ways:

-

acting as a disciplining device, placing pressure on the managers of firms to become more efficient;

-

via reallocation, ensuring more productive firms increase their market share; and

-

driving firms to innovate, coming up with new products and processes which can lead to step-changes in efficiency.

While research is still ongoing as to which of these mechanisms is more important in different contexts, increasing our understanding of the state of competition in the economy and trends in it over the last 2 decades could help understand where it might be possible to support productivity growth by promoting competition.

Widespread concern that competition is weakening

In recent years competition concerns have been brought into sharp focus in international academic and policy debates with a number of studies suggesting that competitive pressure across advanced economies could be weakening. The most high-profile of these have been focused on the US, with some extending the analysis to Europe, including the UK. In our first assessment of the state of competition[footnote 36] within the UK, we found evidence to support some of these concerns, with a rise in concentration across UK industries and an increase in markups amongst already profitable firms. The rationale for undertaking our assessment is to build a better understanding of what has happened in the UK.

The debate over whether market power is broadly increasing over time most notably gained prominence in 2016 when the White House Council of Economic Advisors (CEA) published research based on US data which tracked the share of revenue accounted for by the 50 largest firms in 13 broad industrial sectors and noted it had increased in 10 of them since 1997. This research also pointed to a sharp increase in the return on capital achieved by the top 10% of US firms and an apparent drop in the rate of firm entry.

Several recent books, by economists and by political commentators, have discussed broad changes in competition in economies and the effect of competition policy on this. In the US, Baker (2019)[footnote 37] has argued that competition policy has become unusually weak in recent decades, allowing for a long-term decrease in competition in markets which has had large macroeconomic effects. Philippon (2019)[footnote 38] contrasts this with Europe, which he argues has been successful in pursuing a stricter competition policy, particularly with regard to mergers, and so has markets which are becoming more competitive. He points to differences in the amount of lobbying and political spending by incumbent firms between the US and Europe as being one of the key explanations for this difference.

In terms of the picture in Europe, De Loecker and Eeckhout (2018)[footnote 39] use Thomson Reuters data on a wide set of countries, including large European and North American countries and a set of developing countries, to estimate the changes in firms’ average mark-ups[footnote 40] in these countries between 1980 and 2016. They find that estimated mark-ups have risen across almost all developed countries, with stable or falling mark-ups observed in many developing countries. According to the authors, the UK has seen an increase in estimated gross mark-ups from just below 1 to 1.68 (meaning prices rose from being roughly equal to marginal cost to being 68% higher than marginal cost), putting the UK in the top third of increases among European countries.

From a UK-specific perspective, the Resolution Foundation found that concentration in the UK economy as a whole increased between 2003 and 2011 – particularly during the financial crisis in 2008 – before starting to fall back again.[footnote 41] This appeared to be the case regardless of the measure of concentration used.

Digital markets present different challenges

As set out in the Digital Competition Expert Panel review,[footnote 42] digital technology provides substantial benefits to consumers and the economy. These gains however have arisen without strong competition both in and for the market. This means that consumers are missing out on the full benefits and innovations that competition can bring. Increasing digitalisation makes examining the overall state of competition in the UK particularly important.

Internationally, the consensus on the need for action to address the challenges posed by digital markets has also grown stronger. Work to address these challenges is now underway around the world. In particular, the European Commission published its Digital Markets Act[footnote 43] proposals in December 2020 which include ex ante rules covering large online platforms acting as gatekeepers. In addition, Germany has amended its competition act[footnote 44] to enable it to better address the conduct of large digital companies. There have been regulatory proposals and developments in both Australia and Japan. And in the US, the House Judiciary Antitrust Subcommittee made a range of recommendations[footnote 45] to restore competition in digital markets, and there has been a recent increase in antitrust enforcement activity.

How public authorities are responding

Many competition authorities have recognised the need to change how they operate to respond to these challenges. At the CMA, we have set out proposals for reform of our duties and powers[footnote 46] and set up a dedicated Digital Markets Unit to begin to operationalise key parts of a new regime to promote competition in digital markets.[footnote 47] Internationally, some cross-economy assessments of competition have been undertaken in Germany,[footnote 48] Norway, and New Zealand.[footnote 49]

Purpose of the project and what it can tell us

Purpose

Our central purpose is to better measure and understand the state of competition in the UK, and to help inform policy and academic and public debate on competition. For example, this work may indicate where government efforts to promote competition might be best directed and suggest where further analysis would be helpful.

What this project can tell us

There are many ways of measuring the state of competition. We look at a range of metrics, each aiming to shed light on a different aspect of how markets are functioning in the UK:

-

concentration – the structure of industries and the extent to which industry turnover is divided among the largest firms;

-

adjusted concentration – the structure of industries incorporating broader measures than turnover such as significant shareholdings or imports and exports;

-

profitability and mark-ups – the levels of UK businesses’ profits, the markups of prices over costs charged by businesses and the distribution of profits among businesses;

-

other indicators of competition – how likely the most profitable businesses are to remain the most profitable businesses, the stability of the positions of the largest firms in the economy, and the rates of firm entry and exit;

-

consumer surveys – measures of consumer detriment across markets and channels of purchase;

-

business surveys – firm’s perceptions on competition, barriers to expansion and innovation.

These metrics may be estimated at the level of individual industries, of sectors of the economy and of the whole economy. Individually, each of these measures provides only a limited amount of information, but together they can paint a better picture of the trends in competition over recent years.

This work is not a substitute for the CMA’s work in market studies and market investigations (or the similar work carried out by the sector regulators) and the findings are not intended to be informative of the approach taken (or conclusions that may be drawn) in that context, nor is it our intention (nor would it be feasible) to conduct a ‘market study’ of the whole UK economy. Furthermore, it remains the case that competition can most effectively be assessed at the level of individual product markets – measures based on industries and sectors can only indicate what the underlying trends may be. Our intention is to provide a view of how the structure and performance of markets has evolved over time.

We would like to thank the following people who provided the team with challenge and advice on the project: Dr Anthony Savagar (Senior Lecturer in Economics, University of Kent); Professor Steve Davies (Professor of Economics, University of East Anglia); Joseph Carr (PhD student, University of East Anglia ); Sabria Behilil (PhD student, University of East Anglia).

Concentration, industry structure, and distributional impacts[footnote 50]

Summary

We use concentration as a simple indicator of competition in a market. Higher concentration means a smaller number of firms control a larger share of the market which may lead to weaker competitive pressures and greater market power.

We have used data from the Office of National Statistics to build several measures of concentration from 1998 to 2021 – the longest time period for which data is available. We find that average industrial concentration – aggregated to the level of the whole economy – has increased during the financial crisis and the following recession. Since 2011, we have seen a stabilisation and gradual reduction in concentration, though not to the pre-crisis level. The increase in concentration is driven by the very largest firms in each sector.

We divided industries according to their HHI levels and found that, even at the relatively aggregated 4-digit industry level, 2 in 5 industries are classified as medium or highly concentrated, a proportion which has not changed significantly over time.

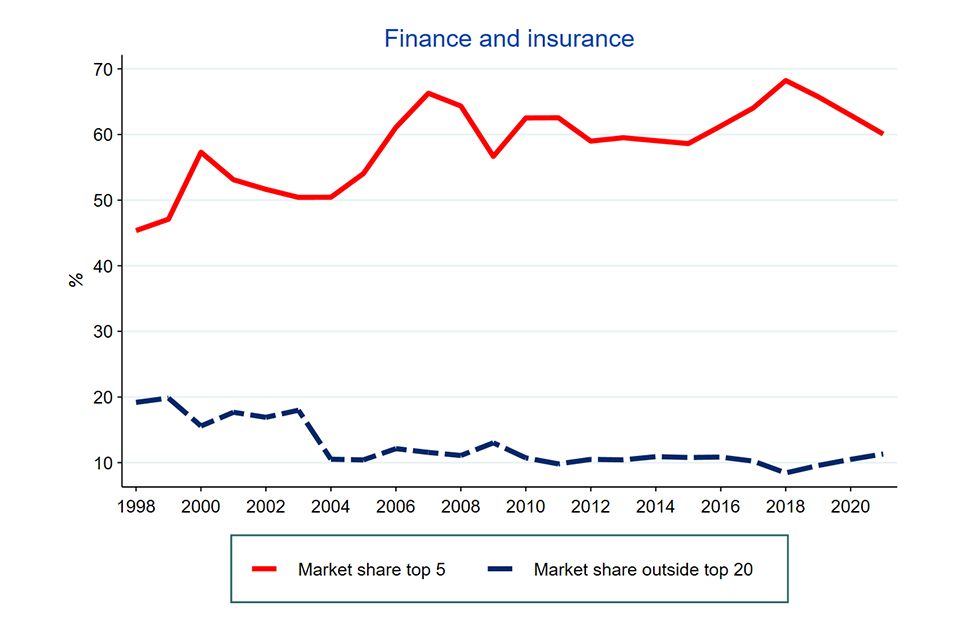

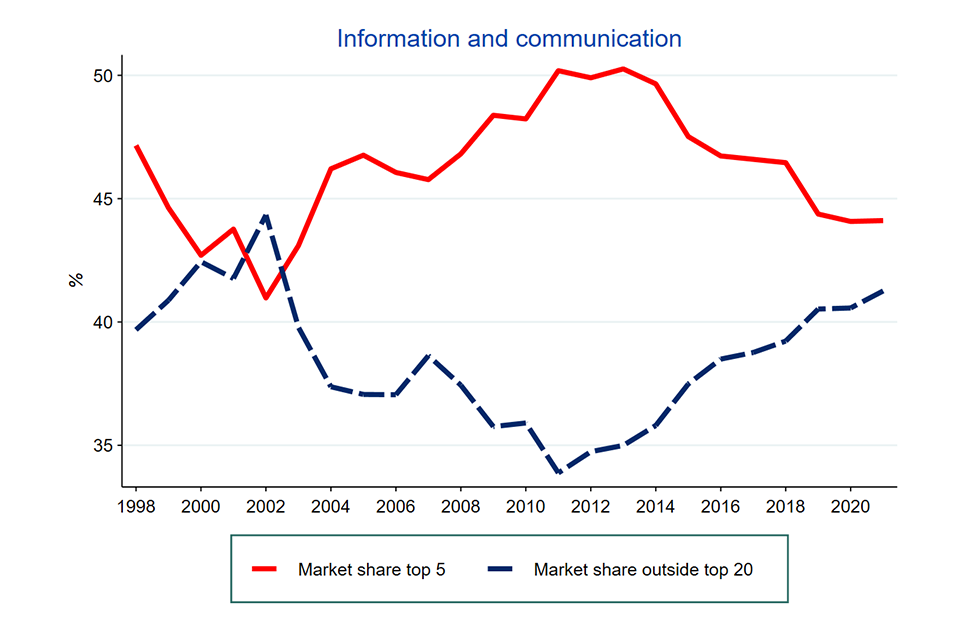

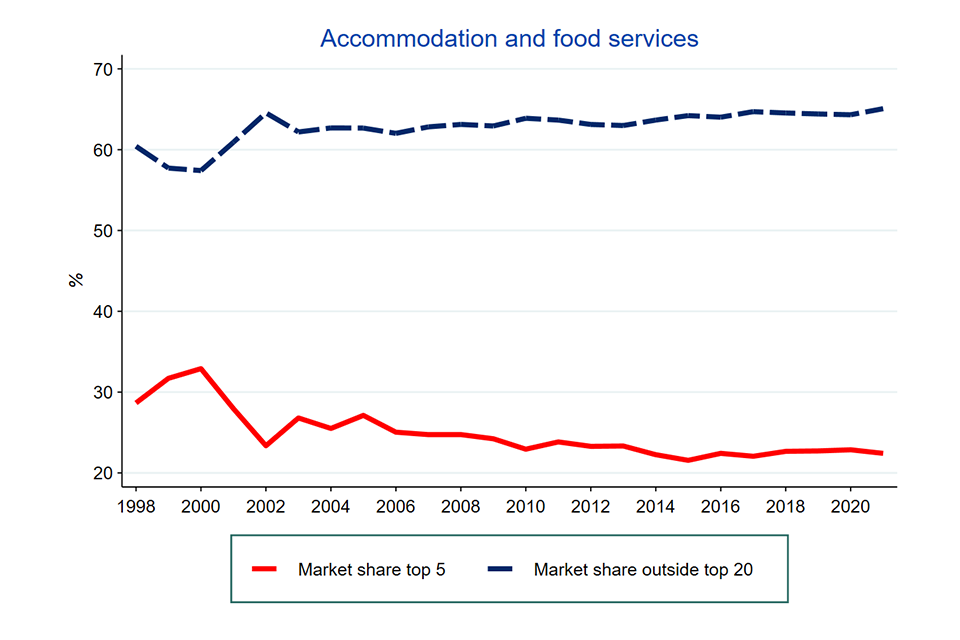

Sector-level trends show differences in concentration trends across sectors. Among the high-turnover sectors, Finance and insurance, Manufacturing, and Information and communication show high and/or increasing concentration levels.

Looking at the relationship between concentration and inequality, it is illustrated that poorer households spend a greater proportion of their income on essential goods or services. These households on average face markets that are approximately 30% more concentrated than markets faced by the richest households. Therefore, this would suggest that poorer households are more vulnerable to the effects of concentration.

Concentration and industry structure

Introduction

In this chapter, we consider measures of competition based on industry structure, such as concentration. We first explain what aggregate measures of concentration can and cannot tell us about competition. We then give an overview of the existing studies of concentration across the UK economy and compare the results to work done in other countries.

We then set out our own concentration analysis of the UK economy. In doing this, we consider how the average concentration of UK industries has changed since 1998 and examine the trends at the sector level. The time period considered is driven uniquely by the availability of reliable data. Our more detailed analysis of concentration and industry structure across the UK economy is set out in Appendix A.

We also seek to establish an empirical understanding of the relationship between market concentration and income inequality, effectively looking at the extent to which poorer households lose out because their consumption is disproportionately high in markets where firms are more concentrated and therefore more likely to exert market power.

Concentration as a measure of competition

Estimating concentration in individual markets is an intuitively simple way to assess the level of competition across an economy. Economic theory tells us that the more concentrated a market is, the less competitive pressure firms may face, potentially resulting in increased market power.[footnote 51] This could result in higher prices and lower quality for consumers, either directly, or indirectly if the increase in market power manifests itself in fewer incentives to invest and innovate.

The 2 most common measures of concentration are the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) and Concentration Ratios.

Concentration-based metrics have the advantage of simplicity; all we need to calculate them are firm-level revenue figures within reasonably defined industries.

However, we must be cautious in interpreting them as direct evidence of market power. Concentration metrics do not measure market power directly. Rather, they are one step removed as they are a ‘market outcome’ – that is, they arise as a result of the competitive interactions of firms rather than determining the competitive interaction.

This means we need to be careful when interpreting concentration metrics, as the underlying causes of any observed changes in industry concentration may be unclear. For example, an increase in concentration can be either the result of fierce competition (where more efficient firms gain market share at the expense of less efficient ones) or the result of anti-competitive behaviour where one firm uses its market power to exclude other firms. Similarly, an increase in concentration might not always lead to weaker competition, and the effect of changes in concentration is likely to depend on the initial level of concentration (see CMA analysis). In addition, the level and trends in globalisation and digitalisation are likely to influence the concentration in a market.

HHI, Concentration Ratios, and their limitations

As mentioned in concentration as a measure of competition, the 2 most common measures of concentration are the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) and Concentration Ratios.

The HHI is calculated as the sum of the squares of each firm’s shares at a given level of aggregated activity. It ranges between 0 to 10,000, where a value of 0 represents perfect competition and 10,000 represents a monopolist. Product markets with HHIs of more than 1,000 are generally considered to be concentrated, and those with HHIs of more than 2,000 to be highly concentrated.[footnote 52],[footnote 53]

Concentration Ratios are the combined market share of the largest firms.[footnote 54] This is the sum of the market shares of the top 5, 10, or 20 firms at a given level of aggregated activity. The number is often expressed as Cn (for example C5, C10 or C20).

Both indices have their advantages and disadvantages. For example:

-

The HHI accounts for the market shares of all companies in an industry, regardless of their size. Therefore, the HHI will capture information from across the entire industry. Concentration Ratios, instead, disregard any information beyond the top n largest firms. For example, the C10 will not account for the market shares of companies smaller than that top 10 in the industry. This can represent an advantage for Concentration Ratio where market shares information is only available for the largest firms, or where we are interested only in the ‘dominance’ of the largest group of firms. It can also represent a disadvantage as it might disregard important dynamics among medium and small sized firms. Moreover, when only a small number of firms belongs to a narrowly-defined industry, Concentration Ratios might not be very informative.

-

Concentration Ratios are measured in market shares, while HHI has no intuitive unit of measure. This enhances the interpretability of Concentration Ratios. However, the HHI can be interpreted as follows: from the value of the HHI, it can be computed the correspondent number of equally sized firms required to obtain the same HHI. For example, an HHI of 2,000 indicates that the market is as concentrated as a market with 5 equally sized firms.[footnote 55]

-

Both indices are relatively easy to compute. However, they are both aggregate measures which may hide interesting complexities in the underlying distribution of market shares.[footnote 56] One should therefore take this into account when interpreting the results.

Moreover, there are also caveats around the methodology and data we (and others) use to look at concentration across an economy.[footnote 57] In particular:

-

In the UK, we must rely on data gathered based on the Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) system, and even the most granular SIC codes are likely to be far broader than any ‘product market’[footnote 58] that the CMA would define in any inquiry or casework.[footnote 59] This makes it hard to draw direct conclusions about competition in a particular market.[footnote 60] Moreover, in this data each firm is allocated one single SIC industry even if it in reality it operates across several. This makes the study of multiproduct/multiservice companies difficult. Additionally, SIC codes do not easily take account of newer markets, such as digital markets, as they are based on traditional industrial classifications.[footnote 61]

-

In the UK, data on business turnover is only available at the national level, but geographic markets are not necessarily national and can instead be either local or international. For example, a leading retail chain setting up new stores in multiple local areas may lead to an increase in the measured national concentration, as it is likely that the retail chain would make more sales nationally. However, retailers often compete in local markets[footnote 62] and there may be no increase (and possibly a decrease) in the concentration of any local markets it enters as existing retail stores in those local areas face an additional competitor.[footnote 63]

-

In an industry of international scope, where imports make up a material part of domestic consumption, concentration statistics, which only show the production of domestic firms, will provide a misleading view of the actual structure of the market.[footnote 64] This poses a particular problem when charting changes in the estimated level of concentration over time – as many markets in developed countries, particularly those for manufactured goods, have seen increasing levels of imports and the closing of domestic manufacturers.[footnote 65] We address this particular issue in adjusted concentration.

Existing concentration studies

Compared to the body of literature focussing on concentration in the US, the number of papers published focussing specifically on the UK is fairly small. Nevertheless, there has been a recent increase in the number of UK-focussed studies. We discuss the main studies which look at changes in concentration in the UK in the following paragraphs. We discuss their findings below, highlighting points of consensus and areas of disagreement.[footnote 66]

Findings

Common, though not universal, themes from these studies are that, over the last 2 decades and at an economy wide level:

-

concentration levels are higher now than they were in 1998 – the oldest data available

-

concentration in the UK peaked just after the financial crisis, but was generally stable or fell after the financial crisis back towards pre-financial crisis levels

One study (Aguda, Hwang, and Savagar (2019)) found evidence that aggregate measures of concentration in the UK are sensitive to the inclusion in the sample of certain industries.

In addition, all of these studies show that the economy-wide results mask the fact that different industries followed different trends with some experiencing increases in concentration while for others concentration remained constant or decreased.

The Resolution Foundation found that concentration in the UK economy increased between 2003 to 2004 and 2010 to 2011, before starting to fall back again. This appeared to be the case regardless of the cross-economy measure used.

-

Between 2003 to 2004 and 2010 to 2011, the share of the largest 100 firms across the entire economy increased by over a third in the UK, from 18.5% to over 25%, and then began to fall, reaching roughly 23% in 2015 to 2016.

-

With respect to economy-wide average Concentration Ratios,[footnote 67] the Resolution Foundation found that concentration similarly increased between 2003 to 2004 and 2010 to 2011, albeit to a smaller degree than seen using the CR100 measure. After this spike, the aggregated subsector concentration measures levelled off and then started to fall, not returning to their pre-crisis levels.

-

Finally, economy-wide average HHIs showed concentration rising from below 900 in 2003 to 2004 to above 1,100 in 2010 to 2011, and then falling to around 940 in 2015 to 2016.

Additionally, when looking at changes in concentration in each sector, the Resolution Foundation found that concentration increased in two thirds of all industries over the same timeframe. The sector with the largest observed increase was ‘Manufacturing’ (over 10% increase) – ‘Other’ also experienced a 25% increase, driven primarily by the gambling subsector.[footnote 68] Three sectors decreased in concentration, with ‘Construction’ experiencing the largest decrease (roughly 2.5%).

The Resolution Foundation considered what was driving the changes in its economy-wide averages. It found that the rise was caused by both an increase in the share of the economy accounted for by highly concentrated subsectors and a general increase in concentration within the subsectors. However, while it found a general increase in concentration at the subsector level, this masks the fact that actual trends differ substantially between individual subsectors. For example, based on CR5 concentration figures, 55% of the subsectors analysed saw an increase in concentration from 2003 to 2004.[footnote 69] Similarly, while the share of subsectors with high concentration[footnote 70] grew from 18% to 21%, the number of subsectors with low concentration[footnote 71] increased from 40% to 41% over the same timeframe.

BEIS (2020) found concentration increased across all its Concentration Ratios between 2006 and 2010.[footnote 72] While the absolute levels of concentration found by BEIS are lower than those found by the Resolution Foundation, the percentage increases across CR5 and CR10 are larger in BEIS’ results. After this spike, concentration levelled off and slowly decreased, while remaining above pre-financial crisis levels. BEIS found similar results when analysing a weighted average HHI, although this measure found a larger observed fall after the financial crisis than its estimated Concentration Ratios, with HHI decreasing to pre-financial crisis levels in 2017 before increasing again in 2018.

Again however, the economy-wide averages are not representative of the levels as well as trends in concentration that many sectors of the economy experienced.[footnote 73] Generally, around half of the sectors examined by BEIS experienced an increase in concentration between 2006 and 2018 across all concentration measures, with concentration in the remaining sectors remaining constant or decreasing.

Alongside this, BEIS also published data on churn as well as firm entry and exit, finding that firm entry rates fell during the financial crisis and have been stable since.[footnote 74]

The UK specifically had a large proportion of industries with strong increases in concentration – in 29% of British industries the share of the 4 largest firms grew more than 20%. Underlying all of these results, the authors suggest that the changes in concentration suggest a tendency towards ‘oligopolistic structure’.

Bajgar, Criscuolo and Timmis (2021) took a similar approach and examined the share of sales of the largest 8 business groups in 13 countries including the UK.[footnote 75] The authors then compared these against the shares of both the 4 largest firms and 20 largest firms. The authors used the Orbis database to calculate the sales of the largest firms and the OECD STAN database at the 2-digit level to calculate total sales in each country industry. Overall, the authors found that from 2002 to 2014 there was a broad increase in industry concentration across the majority of sectors and countries, including the UK.

Davies (2021) found that concentration at the 4-digit level increased rapidly (by 30%) between 1998 and 2011 before levelling off at a high level from 2011 to 2018. Within industries, this increasing concentration was usually fuelled by soaring market shares for the largest 5 firms at the expense of the smallest.[footnote 76]

Aguda, Hwang, and Savagar (2019) investigated the sensitivity of aggregate market concentration measures to the sectors that are included and found, when using their full sample, broadly decreasing concentration in the UK between 1998 and 2018 based on whole economy CR5, CR10, CR20, and CR50. However, their results are consistent with the other papers when assessing these concentration trends for a sub-sample which excludes firms from subsectors known to be poorly measured or where using turnover to indicate output might be problematic. They found increasing concentration up until 2010, followed by a period of fluctuating concentration until 2016, after which a decrease in concentration can be seen.

When assessing entry and exit in the UK – something we discuss in markups and profitability – the authors found that in most years entry was greater than exit with the difference being greater after the financial crisis.[footnote 77] The exceptions are during and just after the financial crisis (2008 to 2011) and in 2018 where more firms exited the economy than entered it.

Valletti, Koltay, Lorincz, and Zenger (2017) examined concentration in the UK, alongside France, Germany, Italy and Spain, using both the weighted average CR4 and HHI4. The authors found that concentration was constant in 2010 and 2011, before falling afterwards to plateau around 2014 to 2015. A later report by Koltay, Lorincz & Valletti (2021) documented 2 more results.[footnote 78] First there was a moderately increasing average industry concentration over the last 2 decades. Second, there was a considerably increasing proportion of high concentration industries. Low and mid concentration industries became more concentrated on average, while industries with existing levels of concentration higher than 60% became less concentrated.

The Social Market Foundation (2017) report found that 8 out of the 10 analysed markets exhibited HHI levels exceeding 1,000 in 2016, of which 3 showed HHI levels of 2,000 and above. Eight out of 9[footnote 79] markets exhibited CR4 market shares of over 50%, indicating a considerable amount of concentration. Consistent with other studies that identified different trends amongst subsectors over time, the researchers found that markets moved in different directions, with some markets falling in concentration while a number of other markets became more concentrated over the observed timeframe.

UK-specific findings in the international context

In Europe the evidence is mixed, with some papers suggesting increasing concentration, others finding stability, while others suggest concentration has been falling. In contrast, the majority of the literature on the US suggests an increase in concentration, with Gutiérrez and Philippon (2020)[footnote 80] representing an exception to this.

The trend of increasing concentration in the US was most notably put forward when the Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) published a note based on US data which tracked the share of revenue accounted for by the 50 largest firms in the 13 industrial sectors defined by the North American Industry Classification System,[footnote 81] and noted it had increased in 10 of them between 1997 and 2012.[footnote 82]

Findings of increasing concentration in the US are also reported in Autor et al (2020), [footnote 83] who generally found increasing concentration across the OECD[footnote 84]. Grullon, Larkin, and Michaely (2018) [footnote 85] also report increasing concentration in the US; using HHIs, they suggested that concentration increased in more than three-quarters of US industries over the last 2 decades, with the average increase reaching 90%. They also found a significant increase in the CR4, including public and private firms, in most industries. Additionally, they reported that the average and median size of public firms has tripled in real terms.

Bajgar et al (2019) [footnote 86] calculated SIC-code level concentration in Europe and North America using both OECD MultiProd data and Orbis-Worldscope-Zephyr data. In line with the CEA results for the US, the datasets show a rise in industry concentration between 2000 and 2014, with roughly 75% of industries in both continents becoming more concentrated over this period.

On the other hand, Gutiérrez and Philippon (2018) [footnote 87] found stable to decreasing concentration in Europe, which they mainly attribute to a combination of stronger enforcement of pro-competitive policies in Europe, falling product market regulations, more stringent competition laws and lower levels of lobbying compared to the US. While the researchers found concentration increased in Europe during the financial crisis and immediately afterwards, the levels of concentration have been fairly stable since the early 2000s and have fallen since the late 1990s. The US on the other hand witnessed an increase in concentration over the same timeframe.[footnote 88]

Separately, Gutiérrez and Philippon (2020) also looked at the evolution of concentration globally as well as in the US by focussing directly on the largest global and US firms in terms of sales in a given year. They compared domestic sales of the largest US companies with domestic US GDP[footnote 89] and consolidated global sales of the largest global companies with global GDP. Contrary to the other works, they concluded that over the past 2 decades, the largest firms have not outgrown the global economy and that their domestic share of domestic GDP has been more or less stable over the previous 4 decades. Additionally, Gutiérrez and Philippon found that the largest firms have witnessed a decline in their share of global GDP.

CMA analysis

This section summarises the analysis we have undertaken for this report, with the detailed findings set out in Appendix A. As outlined in the concentration as a measure of competition section, there are several caveats when using trends in concentration to measure changes in the level of competition. We have considered the extent to which it is possible to address these caveats in our own analysis.[footnote 90]

Economy wide concentration trends

C5 and C10

To begin with, we look at the results when aggregating all the individual 4-digit SIC codes to look at the concentration picture cross-economy from 1998 to 2018, as measured by C5 and C10, aggregated by turnover.[footnote 91] In doing so, we exclude non-market sectors, such as government-related services and education, because of the different role that competition plays in these industries. We are also wary of the potential impact that large (in terms of relative turnover) sectors like finance and extraction of oil might have on our aggregate figures. Therefore, we construct 2 measures:

-

turnover-weighted mean C5 and C10, excluding Finance and insurance and Fuel wholesale[footnote 92]

-

the median of sectors’ C5 and C10[footnote 93]

Figure 2.1 shows concentration measured by the mean C5 while Figure 2.2 shows concentration as measured by the median C5. For consistency with our State of Competition report from 2020, we also report the C10.

Figure 2.1: Turnover-weighted mean C5 and C10, across whole UK economy

Image description: A line graph showing the turnover weighted mean C5 and C10 from 1998 to 2021. There are separate lines for C5 and C10 and the figure is depicted in percentages.

Source: CMA analysis of ONS BSD data

Note: Excludes some non-market sectors such as government services – including fully government-run sectors such as central banking, and those dominated by the public sector, such as education; and the 4-digit industry Wholesale of solid; liquid and gaseous fuels and related products and industries in the Finance and Insurance sector as their runover disproportionately affects our results.

Figure 2.2: Median C5 and C10, across whole UK economy

Image description: A line graph showing the median C5 and C10 from 1998 to 2021. There are separate lines for C5 and C10 and the figure is depicted in percentages.

Source: CMA analysis of ONS BSD data

Note: Excludes some non-market sectors such as government services – including fully government-run sectors such as central banking, and those dominated by the public sector, such as education. Median is calculated as the median of turnover-weighted sector-level means.

Both graphs show a similar trend. Looking at the period 2008 to 2021, we can see that concentration increased between 2009 and 2011, then declined from 2014 onwards. This increase coincides with the financial crisis and the recession in its aftermath (Q2 2008 to Q2 2009). While concentration has declined from its peak in 2011, it is still at a higher level than seen from 1998 to 2008.

A comparison between the C5 and C10 suggests that the change in concentration is almost entirely driven by the 5 largest firms in each industry. Indeed, the 2 lines in Figure 2.1 and Figure 2.2 are nearly identical with only a difference in the level. Moreover, the median (both here and for the HHI below) shows a sharper rise in concentration after the financial crisis and slower decline after that than the mean. In the limited time available, we were not able to pinpoint exactly to the source of this difference.

HHI

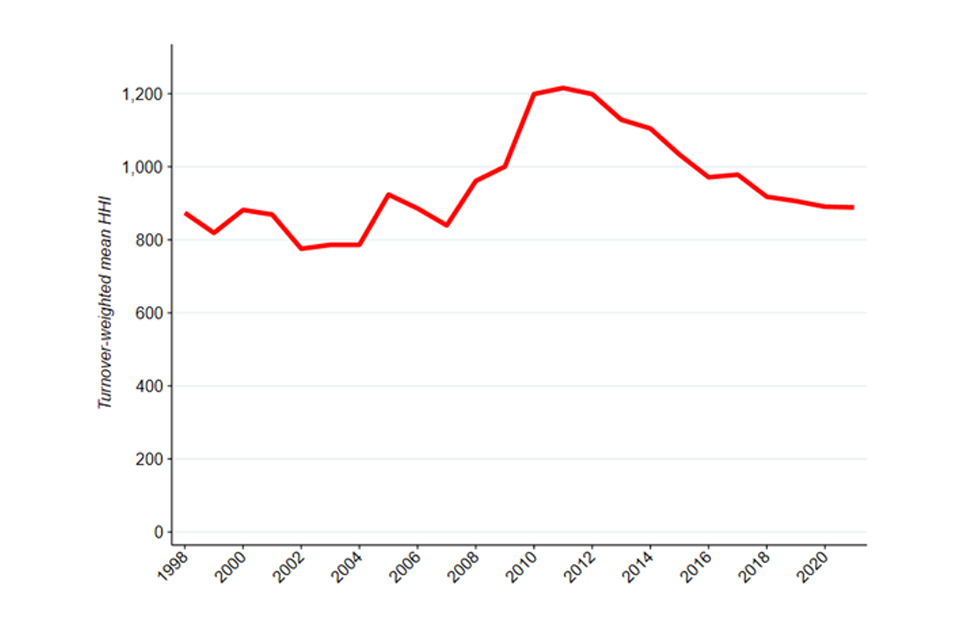

Figure 2.3 shows the economy wide HHI. Similar to what we did with the C5 and C10, we present both turnover-weighted average and median HHI.

Image description: A line graph showing the turnover weighted mean HHI across the UK economy from 1998 to 2021.

Source: CMA analysis of ONS BSD data

Note: Excludes some non-market sectors such as government services – including fully government-run sectors such as central banking, and those dominated by the public sector, such as education; and the 4-digit industry Wholesale of solid; liquid and gaseous fuels and related products and industries in the Finance and Insurance sector as their runover disproportionately affects our results.

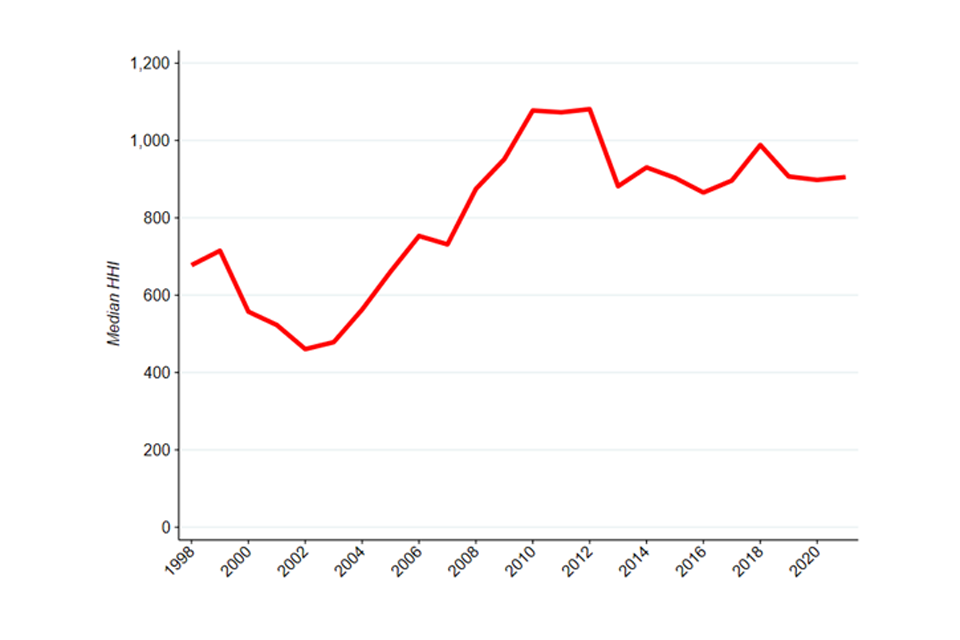

Figure 2.4: Median HHI, across whole UK economy

Image description: A line graph showing the median HHI across the UK economy from 1998 to 2021.

Source: CMA analysis of ONS BSD data

Note: Excludes some non-market sectors such as government services – including fully government-run sectors such as central banking, and those dominated by the public sector, such as education. Median is calculated as the median of turnover-weighted sector-level means.

The pattern is similar to the one seen in C5 and C10: concentration has materially increased after the financial crisis.

In interpreting C10 ratios and HHI (or other concentration metrics) over a 23-year period, we should bear in mind that several factors might affect their change over time.[footnote 94] However, overall, this evidence suggests that the peak in concentration that coincided with the financial crisis has taken some time to fall away and, especially in the case of median concentration, remained at levels higher than pre-financial crisis. The trends we have found are consistent with the findings of the Resolution Foundation and BEIS reports (see the findings section).

Distribution of C5

Another way to visualise changes in concentration is to look at the distribution of concentration indices over time. We start by looking at the C5.

In particular, we look at the way 4-digit SIC industries are distributed according to their concentration and how this distribution has changed in the past 11 years. This analysis may shed light on the level of competition in the economy. A competitive economy is expected to show an asymmetric distribution with most industries showing a relatively low concentration. This means that one would expect most industries to have a relatively low value of C5.

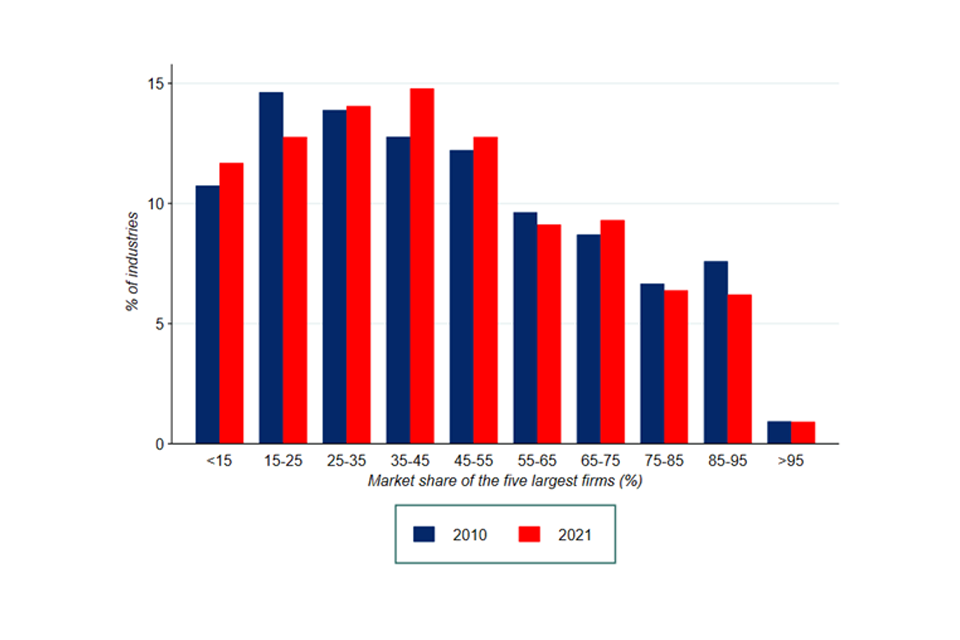

Figure 2.5 shows that this is the case for the UK. The bars represent the proportion of industries with a given level of concentration.[footnote 95] Concentration, in this case, is measured as the total market shares of the top 5 firms. We present this information for both 2010 and 2021.

Figure 2.5: Distribution of industries according to the market share of the 5 largest firms in 2010 and 2021

Image description: A bar graph showing the distribution of industries according to the market share of the 5 larges firms in 2010 and 2021. The y axis depicts the market share the 5 largest firms have and starts at <15%, then 15 to 25% and so on until it reaches >95%. Each section has 2 bars which represent the total percentage of industries in 2010 and 2021 for which the 5 largest firms that had that specific market share.

Source: CMA analysis of BSD data.

Note: graph based on 4-digit SIC industries. Excludes industries in some non-market sectors such as government services – including fully government-run sectors such as central banking, and those dominated by the public sector, such as education.

The distribution in Figure 2.5 presents the expected positive skewness. In 2021, more than 53% of the industries are characterised by the largest 5 firms holding 45% or less of the market. Less than 14% of industries have a C5 greater than 75%.

The distribution is broadly similar in 2010 and 2021. The most substantial changes are a reduction in the proportion of industries with a C5 of 15-25% and an increase in the proportion of industries with a C5 of 35 to 45%. Moreover, the proportion of industries with a C5 greater than 75% has not increased.

Concentration trends in the proportion of industries by HHI levels

We now turn to the distribution of the HHI. Competition authorities around the world have often used specific levels in the HHI to determine whether a market is highly concentrated. For example, the merger assessment guidelines of the US Department of Justice (DOJ) state that a market is highly concentrated if it presents n HHI above 2,500; medium concentrated between 2,500 and 1,500; and not concentrated if below 1,500.[footnote 96] The European Commission uses thresholds of 2,000 and 1,000.[footnote 97]

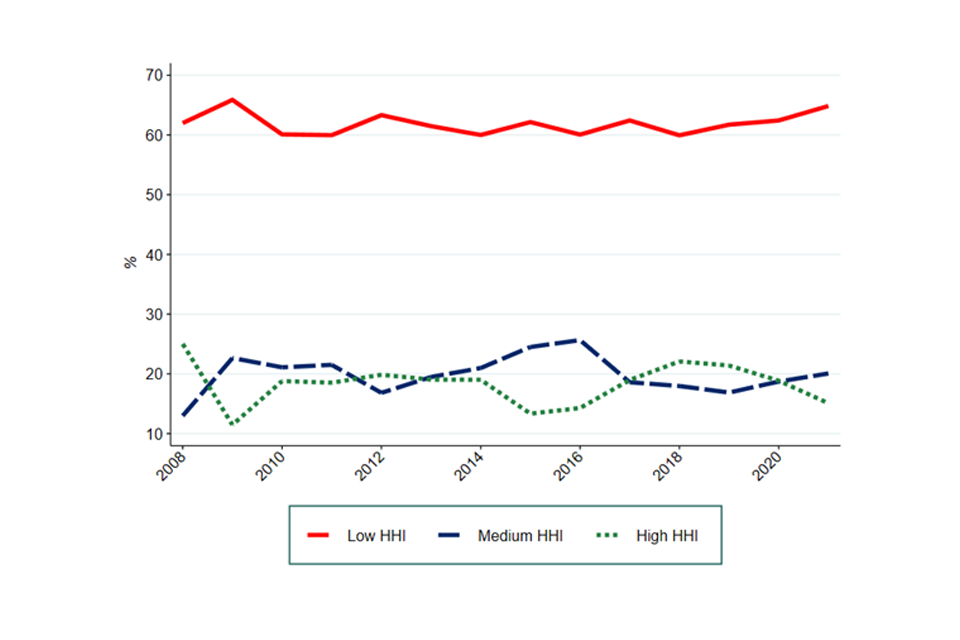

We use the European Commission thresholds to create Figure 2.6. This shows the proportion of UK industries, weighted by their turnover, that fall within each category since 2008.[footnote 98] Using the DOJ thresholds only changes the level, not the trend.

Figure 2.6: Proportion of turnover-weighted industries according to different HHI thresholds

Image description: A line graph showing the proportion of turnover-weighted industries according to different HHI thresholds from 2008 to 2021. There are 3 lines – one for a low threshold, one for a medium threshold and one for a high threshold.

Source: CMA analysis of BSD data

Note: graph based on 4-digit SIC industries. Each industry has been weighted by its total turnover. Excludes some non-market sectors such as government services – including fully government-run sectors such as central banking, and those dominated by the public sector, such as education; and the 4-digit industry Wholesale of solid; liquid and gaseous fuels and related products and industries in the Finance and Insurance sector as their runover disproportionately affects our results.

More than 3 in 5 industries have an HHI level that can be considered low. This result is probably not surprising given we are measuring the HHI at the level of 4-digit SIC industries, a broader level than what the CMA or other antitrust authorities would typically define as a market. As such, the HHI thresholds set out by competition authorities’ guidelines might not be very indicative. However, it is notable that even at this broader level, about 2 in 5 industries have either a medium or high HHI level. In this context, it is important to remind that under some circumstances, high concentration can reflect high competitive pressure, with all but the most efficient firms being driven from the market (see concentration as a measure of competition section).

The proportion of industries within each category is relatively stable over time. In other words, there has not been any material change in the number of industries becoming more or less concentrated.

High-turnover sectors-level concentration trends

In this section, we focus on a subset of the economy and explore sector-level trends. We look only at what we defined as high-turnover sectors as they are the most likely to drive our economy wide measures. These are the 6 sectors in the UK economy with the highest total business turnover[footnote 99] for the period 1998 to 2021. These sectors account for an annual average of 82% of the combined turnover of firms in the BSD. In Appendix A, we provide similar results for the lower-turnover sectors.

There are individual trends apparent at a sector-level (hence when we aggregate all the individual 4-digit SIC codes in a specific sector) that differ somewhat from the whole economy picture. It should also be reiterated that ‘natural’ levels of concentration in different sectors will vary due to differing cost structures and other parameters. Therefore, we focus on trends in the concentration of particular industries over time, and differences in these trends between sectors.

Moreover, in interpreting these sector level trends, the importance of imports in many sectors should be borne in mind. The data on businesses we use to calculate concentration in this chapter is based on UK businesses alone. We address the impact of trade data on concentration measures in adjusted concentration.

C10

Figure 2.7 shows the mean C10, weighted by turnover, within each sector from 1998 to 2021.

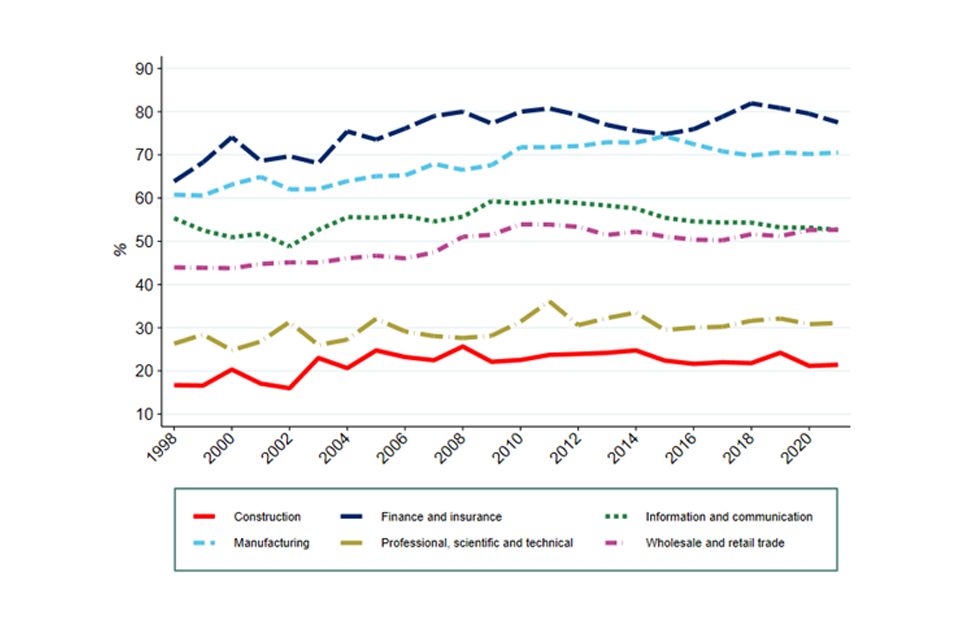

Figure 2.7: Turnover-weighted mean C10 within each high turnover sector

Image description: A line graph showing the turnover-weighted mean C10 within 6 high turnover sectors from 1998 to 2021. There are 6 lines for 6 different industries – Construction, Finance and insurance, Information and communication, Manufacturing, Professional and scientific activities and Wholesale and retail trade.

Source: CMA analysis of ONS BSD data

Note: Data issues mean that figures for 1997 have been dropped. C10 is calculated at 4-digit sic code level and then aggregated to sector level using a weighted average by total firm turnover. Professional and support services includes both Professional, scientific and technical activities, and Administrative and support service activities. Excludes some non-market sectors such as government services – including fully government-run sectors such as central banking, and those dominated by the public sector, such as education; and the 4-digit industry Wholesale of solid; liquid and gaseous fuels and related products and industries in the Finance and Insurance sector as their runover disproportionately affects our results.

Figure 2.7 shows that concentration has increased over the period for most of these high turnover sectors. The sectors differ in the degree to which they become more concentrated prior to the financial crisis, with concentration stabilising across most sectors following that point. It is unsurprising these trends mirror the overall picture given these sectors account for an annual average of 82% of the combined turnover of firms in the BSD. Finance and insurance[footnote 100] stands out as a sector where concentration increased the most in the run-up to the financial crisis from less than 64% in 1998 to more than 80% in 2011, as does Manufacturing whose C10 increased from approximately 61% in 1998 to 74% in 2015.

In Appendix A, we provide similar results for the lower-turnover sectors. Some of these sectors exhibit similar patterns to that described above as they show a relative peak around 2010 (for example Mining and quarrying, and Utilities).[footnote 101] In contrast, in some sectors concentration increases significantly throughout the period (Transport and storage, Other services,[footnote 102] and Agriculture, forestry and fishing) while others become less concentrated over the period (Accommodation and food services, and Real estate activities).

HHI

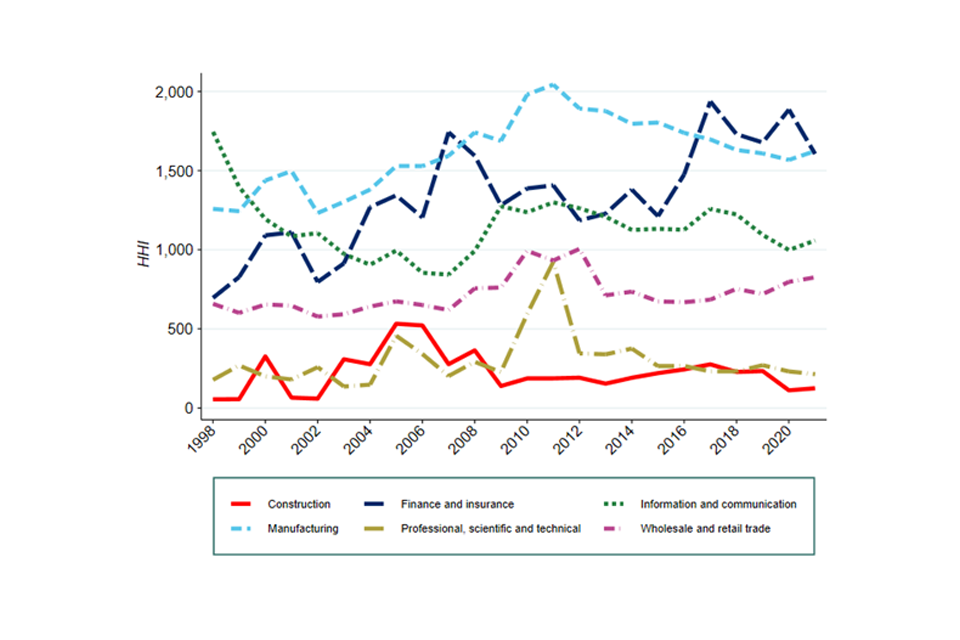

Figure 2.8 shows the mean HHI, weighted by turnover, within each of high-turnover sectors. Again, we focus on the long-term trends rather than the short-term fluctuations.

Figure 2.8: Turnover-weighted mean HHI within each high turnover sector

Image description: A line graph showing the turnover-weighted mean HHI within 6 high turnover sectors from 1998 to 2021. There are 6 lines for 6 different industries – Construction, Finance and insurance, Information and communication, Manufacturing, Professional and scientific activities and Wholesale and retail trade.

Source: CMA analysis of ONS BSD data

Note: Data issues mean that figures for 1997 have been dropped. C10 is calculated at 4-digit sic code level and then aggregated to sector level using a weighted average by total firm turnover. Professional and support services includes both Professional, scientific and technical activities, and Administrative and support service activities. Excludes some non-market sectors such as government services – including fully government-run sectors such as central banking, and those dominated by the public sector, such as education; and the 4-digit industry Wholesale of solid; liquid and gaseous fuels and related products and industries in the Finance and Insurance sector as their runover disproportionately affects our results.

Figure 2.8 shows consistent results with the C10 for some sectors, but not for all. Similar to Figure 2.7, most sectors display a relative peak in the early 2010s, after the financial crisis (for example, Manufacturing, Wholesale and retail trade, and Professional, scientific and technical activities). However, the HHI shows a different pattern for Finance and insurance whose concentration more than doubled since 1998.

In Appendix A, we provide similar results for the lower-turnover sectors. Transport and storage display a declining HHI, whereas Other services increase significantly over the considered period. Accommodation and food services, Real estate activities, and Agriculture, forestry and fishing have low and relatively stable levels of HHI.

Concentration and distributional impacts

Introduction

The analysis in this Chapter draws exclusively from the forthcoming paper by Davies and Mariuzzo[footnote 103] on inequality and concentration. We are extremely grateful to them for their generosity in allowing us to refer to this work ahead of publication and for all their help in producing this chapter.

This chapter seeks to establish an empirical understanding of the relationship between market concentration and income inequality and has been stimulated by the growing concern that the harmful effects of market power may fall disproportionately on the less well off.

Selected literature review

Though there are several studies on the effects of competition on inequality[footnote 104], the analysis presented in this Chapter has predominantly been inspired by 3 academic papers:

-

Baker and Salop (2015) note that given the marginal propensity to consume is less than unity, the lower-income who allocate proportionately more of their income to consumption than higher-income households, should benefit more from lower prices. In contrast, the rich may lose more from any reduction in share prices as a result of lower monopoly profits. In this light, inequality has been framed in terms of consumer surplus and how this is distributed among consumers (by income)

-

Comanor and Smiley (1975) demonstrate that the share of the wealthiest in Gross National Product would decline in the absence of monopoly to the benefit of all those below the median. This effect was driven by the fact that up to 50% of wealth holdings by the richest 2.4% was entirely due to monopolised capital gains. However, the paper also noted that poorer households consume relatively more of their income

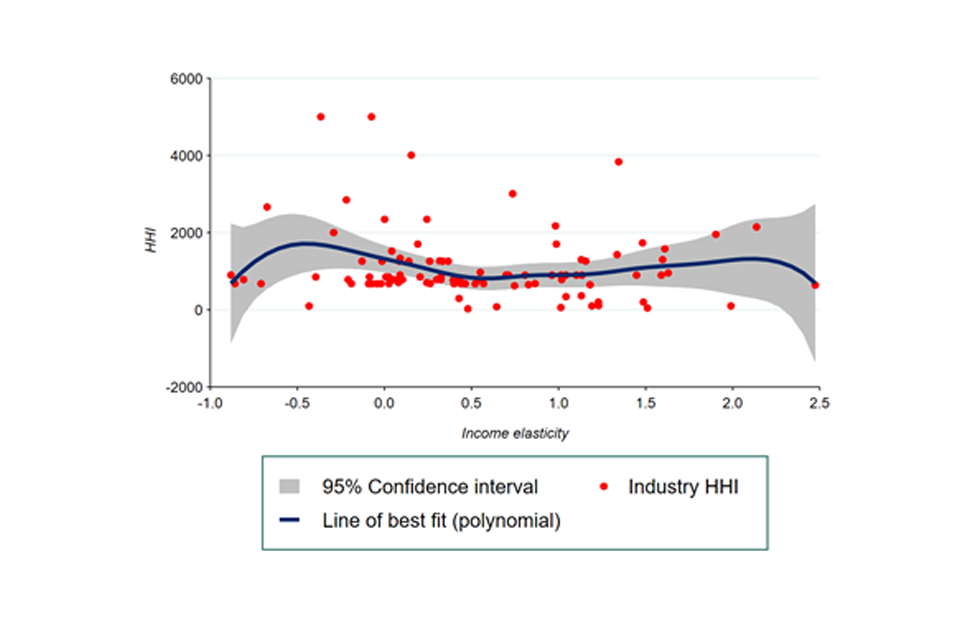

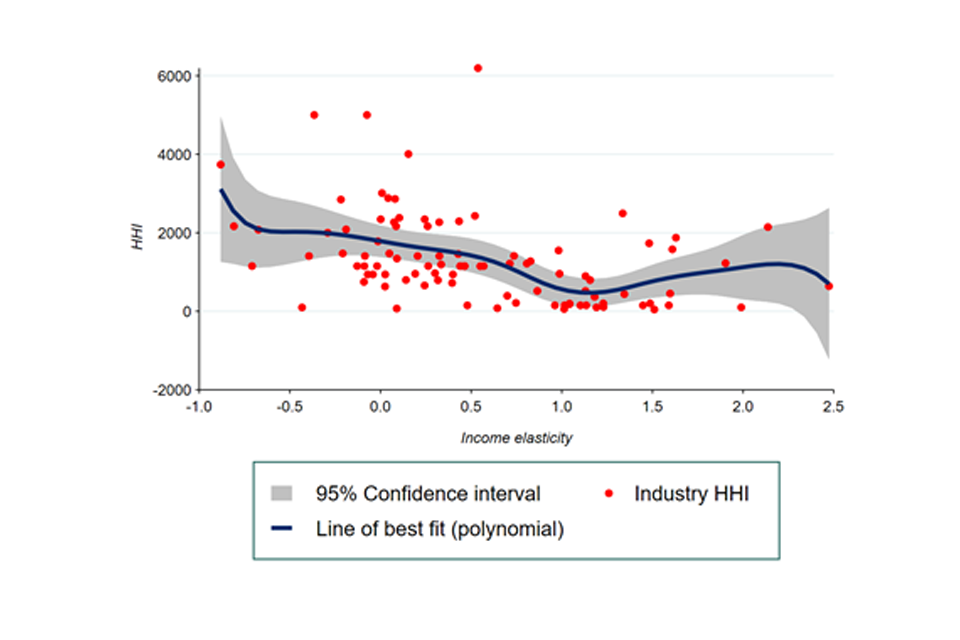

-