Overview of the UK Internal Market

Published 22 March 2022

Introduction

Background

This chapter explains the background to this report providing an overview of the UK internal market, including the wider context of the role of the Office for the Internal Market (OIM). It explains the purpose of this report in setting the scene for the OIM’s ongoing monitoring and reporting role, as well as the information we have drawn on.

Overview of the OIM’s role

The UK Internal Market Act 2020 (the Act) established the OIM to carry out the Competition and Market Authority’s (CMA) functions and powers under Part 4 of the Act. [footnote 1]

The OIM launched on 21 September 2021 [footnote 2] to provide independent advice, monitoring and reporting in support of the effective operation of the UK internal market, following the return of powers from the European Union (EU) to the UK Government and Devolved Administrations (DAs). The Act establishes an OIM panel, consisting of a panel chair (who will sit on the CMA Board) and a number of panel members.

The OIM’s statutory objective is to support, through the application of economic and technical expertise, the effective operation of the internal market in the UK. [footnote 3] It provides non-binding technical and economic advice to all 4 governments on the effect on the UK internal market of specific regulatory provisions that they introduce. It also assists governments in understanding how effectively companies are able to sell their products and services across the 4 nations of the UK, and the impact of regulatory provisions on this, including the impact on competition and consumer choice, for assessment alongside wider policy considerations.

The OIM’s main functions fall into 2 categories:

-

providing reports (or advice, as applicable) on specific regulatory provisions on the request of a Relevant National Authority (RNA) [footnote 4]

-

monitoring and reporting on the operation of the UK internal market. [footnote 5] This has 2 strands:

-

discretionary reviews and reports on any issues relevant to the effective operation of the UK internal market [footnote 6]

-

annual and 5-yearly reports on developments relevant to the UK internal market and its effective operation [footnote 7]

-

Further information on the role of the OIM can be found in its Operational Guidance published in September 2021.[footnote 8]

Overview of the UK Internal Market Report

The OIM is publishing this report providing an overview of the UK internal market as a discretionary output under section 33(1) of the Act, 6 months after its establishment and a year before it is required to produce its first statutory annual and 5-yearly reports. The report is intended to inform understanding of the UK internal market and to help set the scene for the OIM’s future outputs.

What do we mean by the UK internal market?

The UK internal market

The UK is a union of 4 nations: England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. The term ‘UK internal market’ therefore refers to the set of trading relationships within and across these 4 UK nations rather than trade with the rest of the world. [Economic overview of the UK internal market](https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/overview-of-the-uk-internal-market-report/overview-of-the-uk-internal-market#economic-overview-of-the-uk-internal-market] explores the size and composition of the economies of the 4 nations of the UK before considering the trade flows between them.

The UK Internal Market Act

Since leaving the EU and the end of the Transition Period on 31 December 2020, significant powers returned from the EU to the UK Government and DAs, including powers in devolved policy areas – for instance food, waste, hygiene and hazardous substances regulation.

This return of powers has increased the opportunity for regulatory differences to emerge between the nations. An important additional factor in considering the scope for possible regulatory differences is the Northern Ireland Protocol (NIP). [footnote 9] We consider these issues in the regulatory environment.

The Act is intended to ensure the UK’s internal market functions effectively as powers previously exercised at EU level return to the UK, allowing people and businesses to trade without additional barriers based on which nation they are in – limiting the trade and wider economic costs of divergence and providing certainty for people and businesses.

Parts 1 to 3 of the Act therefore establish the market access principles (MAPs) [footnote 10] of mutual recognition and non-discrimination across the 4 nations of the UK:

-

the mutual recognition principle ensures that a product that has been legally produced in, or imported into, and can be legally sold in one part of the UK, can be sold in any other part of the UK; or that a service that can be legally provided in one part of the UK can be provided in another part of the UK

-

the non-discrimination principle ensures that goods or services coming from other parts of the UK are not directly or indirectly discriminated against (in favour of local goods or services)

International examples of internal markets

As the Institute for Government (IfG) notes, the UK is not alone in managing an internal market. [footnote 11] Unitary states, such as Japan and New Zealand, [footnote 12] do not need measures to maintain the integrity of their internal markets. However, federal states or those with powers devolved to territories within them such as Switzerland and Australia, [footnote 13] typically face the same challenge of balancing frictionless trade against the right of the territorial jurisdictions within them to set their own rules.

In developing its approach to supporting the effective operation of the UK internal market, the OIM therefore considered international experience in a number of countries, including Spain, Canada, Australia and Switzerland (see Appendix A).

There are marked differences between these international examples and the UK internal market model, reflecting each individual historical and constitutional context. Similarly, whilst there is broad international recognition of the need to analyse and assess the economic impacts of divergent regulatory approaches that emerge from federal or devolved systems of government, the role of the OIM and its functions necessarily reflects the specific context of the UK internal market.

In particular, although the UK has adopted some similar aspects of the EU Single Market, such as the concepts of mutual recognition and non-discrimination, the UK model differs in several ways, reflecting its specific constitutional position and devolution settlements. Notably, the OIM’s role differs to that of the European Commission in that it does not have a formal role in making regulatory proposals and its function is advisory in relation to regulations that may engage the MAPs.

The purpose of this report

This ‘Overview of the UK Internal Market’ report is intended to support and inform the OIM’s monitoring and reporting role, as described above, by setting out the evidence that we have been able to draw together so far and identifying where there are knowledge gaps ahead of our first statutory reports due by March 2023.

Prior to its launch, the OIM consulted on how it expected to approach the exercise of the internal market functions assigned to it in Part 4 of the Act. [footnote 14] A number of respondents suggested that a key early priority for the OIM should be to compile empirical data on the functioning of the internal market and the effects of regulatory divergence upon it, perhaps through the development of a baseline report.

This report therefore provides an economic overview of the UK internal market, the regulatory environment across the nations and the OIM’s plans to collect evidence and monitor the UK internal market.

More specifically, the report:

-

considers the key elements of the UK regulatory environment, how devolution allows for regulatory divergence, and the potential implications for the UK internal market of leaving the EU

-

provides an economic overview of the UK internal market, including a summary of the available evidence (including trade data and survey evidence)

-

provides a description of the work that the OIM is doing in partnership with the 4 nations to improve the evidence base on intra-UK trade

-

considers where regulatory divergence might be most likely to arise between the 4 nations since the UK left the EU and sets out recent and potential UK internal market developments

The report is likely to be of particular interest to UK Government, the DAs and the 4 legislatures, as well as businesses that trade across the UK and relevant representative organisations.

What information are we drawing on?

In developing this report, we held a series of bilateral meetings with the 4 governments of the UK to discuss the OIM’s role and relevant regulatory developments. We also worked closely with analysts in each of the UK’s nations to consider the economic and statistical evidence available on the internal market and how we can work together to improve the evidence base.

In particular, we have drawn on some specific information sources, including:

-

the results of the OIM’s survey of nearly 600 businesses across the 4 nations, and questions proposed by the OIM which the Office for National Statistics (ONS) included in its Business Insights and Conditions Survey (BICS), discussed in more detail in economic overview of the UK internal market

-

our analysis of published intra-UK trade and other economic data on the economies of the 4 nations

-

desk based reviews of relevant literature and other evidence, such as public announcements, programmes for government and Committee hearings

-

information and knowledge from wider CMA work

Our future monitoring

Our future monitoring reports will be able to build on the information and analysis in this report. We will also draw on our ongoing engagement with UK Government and DAs, as well as analysis we conduct in response to their requests and for our discretionary reviews of specific topics. In particular, we will continue our programme of engagement with stakeholders. [footnote 15]

In addition, we have set up a new digital reporting service, [footnote 16] for businesses and other stakeholders to submit information and evidence via a webform on how the UK internal market is working, which will help to inform our intelligence function.

The information provided through the webform, as well as from other sources, will be analysed to help monitor how effectively goods and services are moving between different parts of the UK, and whether there are any barriers preventing individuals from practising a profession in one part of the UK because the qualification was obtained in another part of the UK, and to identify emerging issues. We will use this information to decide whether to produce ‘own-initiative’ reports using our powers under s33 of the Act as well as to inform our general monitoring of the effectiveness of the UK internal market.

The regulatory environment

Introduction

In this chapter, we consider the regulatory framework relating to the UK internal market and the potential for regulatory differences to emerge between the UK’s 4 nations, particularly following the UK leaving the EU. We also consider the OIM’s role in assessing regulatory developments.

The chapter is structured as follows:

-

the regulatory environment – we set out what we mean by the relevant ‘regulatory environment’ in terms of the OIM’s role

-

devolution and regulatory divergence – we provide an overview of devolution in the UK [footnote 17] and set out how this allows for regulatory divergence between the UK nations

-

regulatory divergence and Brexit – we discuss the relationship between Brexit and the scope for regulatory divergence within the UK

-

the OIM’s role in relation to regulatory developments – we describe the OIM’s role in supporting the effectiveness of the UK internal market, through advice, monitoring and reporting, as well as how the OIM’s work can help to inform policy development

-

the OIM’s consideration of specific regulatory developments – we explain what regulatory issues might fall to the OIM to consider, including the implications of the NIP and interaction with the Common Frameworks programme [footnote 18]

What is the relevant regulatory environment?

As set out in the regulatory environment, the OIM has reporting and advisory functions under ss 34 to 36 of the Act relating to ‘regulatory provisions’, which the Act defines [footnote 19] to ‘include primary and subordinate legislation, retained EU legislation and provision made under legislation, [footnote 20] but not provisions necessary to give effect to the NIP. [footnote 21]

Under the Act, a relevant regulatory provision is one to which the MAPs for goods, services, or professional qualifications apply. Some provisions fall outside our scope because they are excluded by Schedule 1 (goods) or Schedule 2 (services), [footnote 22] or because they were in place before 31 December 2020 (the end of the transition period following the UK’s exit from the EU). [footnote 23]

Furthermore, for the OIM to consider a regulatory provision under ss 34 to 36, the provision must apply to one or more of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, but not apply to the whole of the UK.

As explained in the regulatory environment, under section 33(1) of the Act, the OIM also has a role to monitor and report on the UK internal market, including on any issues relevant to its effective operation, or the effective operation of the MAPs. [footnote 24] In practice, as well as regulatory provisions, these issues could include matters which are not of a legislative nature but may impact on the movement of goods or services between the 4 nations such as relevant trade association rules or government policy; and relevant regulatory provisions which would not fall within the OIM’s ss 34 to 36 functions because they are excluded from the MAPs.

For the purposes of the Act and the OIM’s role, the relevant ‘regulatory environment’ therefore broadly refers to regulatory developments falling within the above scope. For this report, however, at this early stage in the OIM’s life, we focus primarily on regulatory developments that may be relevant to our functions under ss 34 to 36 of the Act, rather than the broader range of developments that we might consider under s33(1).[footnote 25]

Devolution and regulatory divergence

In the UK, devolution has been a process conferring increased legislative powers upon the elected legislatures of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, and executive (or administrative) powers on their administrations / governments. Each devolved nation in the UK has its own devolution settlement, [footnote 26] with the creation and development of devolved legislatures and administrations.[footnote 27] See Appendix B for more information.

The exercise of devolved powers by the elected legislatures of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland can take many forms, but most relevant to the UK internal market is the power to adopt new regulations and change existing regulations. Regulatory divergence can therefore occur where new or changed regulations in one or more of the 4 nations is not adopted in them all, resulting in differences between the nations in how they treat businesses. Divergence may also occur where UK Government exercises its reserved powers, but with different approaches or timescales in the devolved nations. As discussed further below, divergence between Great Britain (GB) [footnote 28] and Northern Ireland may also arise following Brexit because of the NIP.

Regulatory change itself can also vary in nature. It may involve either a reduction or an increase in regulation. It may also include procedural changes – such as a requirement to meet particular standards and the establishment of new regulatory bodies to oversee this.

Regulatory divergence and Brexit

Prior to the UK’s exit from the EU, there was already scope for regulatory divergence. Over time, devolution has seen differences emerge between the nations in how they regulate certain goods and some services within their borders – for example, funeral services, building regulations, Sunday trading laws, minimum pricing for alcohol units, the sale of raw drinking milk and the labelling of natural spring water.

However, whilst the UK was a member of the EU, the EU single market provided a framework that limited the scope for further divergence in regulatory approaches across the 4 nations.[footnote 29] The devolved legislatures and administrations were expressly prohibited by statute from passing any legislation or acting in any way that was incompatible with ‘community’ (EU) law or obligations. After the UK left the EU, and at the end of the Transition Period on 31 December 2020, powers previously exercised at EU level returned to the UK Government and the DAs.

This included powers in devolved policy areas – for instance food, waste, hygiene and hazardous substances regulation. This return of powers has increased the potential for regulatory differences to emerge between the 4 nations. Within this general context of increased scope for regulatory differences, the NIP is an important additional factor which we consider further below in relation to the OIM’s role.

The implications of increased regulatory divergence for the UK internal market

Any decision by one or more of the 4 governments to diverge from previously aligned regulatory systems could affect the operation of the UK internal market. Whilst there may be democratic, policy and practical reasons for governments to adopt differing regulatory approaches, there may also be implications – both positive and negative – for intra-UK trade that have not, until recently, typically been considered in any depth.

Absent the MAPs, regulatory differences in one or more nations may affect both the nation(s) adopting the regulations and those not doing so, because they may impose or remove requirements on businesses selling across borders between the nations. Some changes may represent challenges and risks whilst others represent opportunities and rewards. Each of the 4 nations may therefore be affected by decisions made elsewhere and will therefore have an interest in understanding these decisions and their impacts.

Whilst regulatory developments may have beneficial economic effects for intra-UK trade, intra-UK trade barriers might also arise from the UK Government and DAs amending retained EU law in different ways. This could lead to frictions – making it harder to do business across borders, which, in turn, might lead to higher supplier costs, affect investment decisions and impact on the range, price and quality of goods available to consumers.[footnote 30]

The OIM’s role in relation to regulatory developments

In this section we consider the role assigned to the OIM under the Act and, in particular, its aim to assist governments across the UK through its functions to provide reports or advice on specific regulatory provisions as well as to monitor and report on the operation of the UK internal market. We also address how the OIM can help to inform policy development.

Supporting the effective operation of the UK internal market

The aim of the OIM is to assist RNAs across the UK to manage the potential evolution of different regulatory approaches in a way which protects the effective operation of the UK internal market.

As summarised in the introduction, the OIM can provide non-binding technical and economic advice to all 4 governments on the effect on the UK internal market of specific regulatory provisions that they introduce. It also assists governments in understanding how effectively companies are able to sell their products and services across the 4 nations of the UK, and the impact of regulatory provisions on this, including the impact on competition and consumer choice. These considerations would form part of the governments’ assessment of these provisions alongside wider policy considerations. Appendix C addresses the policy making processes in terms of where the OIM might assist governments.

In the context of the OIM’s overall responsibilities, recognising the balance to be struck between frictionless trade and devolved policy autonomy, we consider that ‘effective operation’ includes the following:

-

minimised barriers to trade, investment and the movement of labour between all parts of the UK (subject to relevant exclusions in the Act)

-

ensuring that businesses or consumers in one part of the UK are not favoured over others

-

effective management of regulatory divergence (including through the use of Common Framework agreements)[footnote 31]

The OIM’s focus will therefore be on assessing the economic effects of regulatory differences, with a particular emphasis on trade between the UK nations. The OIM will not assess wider policy considerations, including the benefits, or otherwise, of divergence.

Providing reports and advice

As set out in the introduction, the OIM will provide reports and advice to the RNAs on request. Ultimately, decisions about how potential regulatory divergence post Brexit is managed is a matter for the 4 governments of the UK. However, as we note below, the OIM’s technical and economic analysis is designed to be a valuable input to the policy and decision-making processes of governments as well as potentially assisting with common policy programmes, including Common Frameworks.

The OIM’s analysis may also assist with wider economic policy developments. In this regard we note that Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland each trade more with the rest of the UK than with the EU or the rest of the world (see economic overview of the UK internal market. Given the high level of integration in trade flows between UK nations, potential barriers to trade with the rest of the UK could have implications for economic growth and prosperity.

Monitoring the internal market

As described in the introduction, one of the OIM’s main functions is to monitor and report on the operation of the UK internal market. The Act envisages 3 distinct tools for the OIM to do so: discretionary reviews and reports; annual reports and 5-yearly reports.

There is an important distinction between the scope and nature of the OIM’s annual and 5-yearly reports. The annual report provides for a broad assessment of the ‘health’ of the UK internal market – essentially a review of its operation and function in the wider sense. In contrast, the 5-yearly report requires the OIM to assess the effectiveness of Parts 1 to 3 of the Act and the impact they have on the operation and development of the internal market – i.e. whether the MAPs are fulfilling their function in safeguarding the effective operation of the UK internal market appropriately. The 5-yearly report will also cover Common Frameworks and their interaction with both Parts 1 to 3 of the Act and impact on the effective operation of the UK internal market.

To conduct its monitoring function, the OIM can commission research to establish baselines and benchmarks, and seek to understand flows and barriers to flows of capital, trade and labour to develop an evidence base.[footnote 32] [Economic overview of the UK internal market](https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/overview-of-the-uk-internal-market-report/overview-of-the-uk-internal-market#economic-overview-of-the-uk-internal-market] of this report includes the outcomes of the OIM’s research on the current economic and trade structure of the UK internal market.

The OIM’s consideration of specific regulatory developments

As well as monitoring general trends, the OIM will seek to track specific regulatory developments in the nations of the UK and to assess relevant changes and developments in the internal market over time to identify the sectors or industries in which these are occurring. As noted above, this will include considering the impact of Common Framework agreements on the development of the UK internal market. In developments in the regulatory environment, we consider the sectors where relevant regulatory developments may be most likely to arise and identify some examples of potentially relevant regulatory developments in these sectors.

In the OIM’s view, specific variations in regulatory provisions (including sales restrictions) with the potential to affect trade in goods may include, for example: [footnote 33]

- packaging, labelling or design regulations

- restrictions relating to the transport and sale of live animals, or animal and plant products

- testing, inspection and certification procedures

- environmental, safety or quality regulations

Potential regulatory developments in relation to the regulation of service providers may notably include: [footnote 34]

- local presence requirements

- local qualification requirements

- restrictions on business structure

Understanding these developments will assist the OIM in undertaking its monitoring role, but also potentially in addressing requests for reports and advice from RNAs, as well as in identifying where the OIM may conduct discretionary work.

Under the Act there is a presumption that professional qualifications will be recognised throughout the nations and that there must be no discrimination when assessing the compatibility of qualifications with national law. Some provisions, such as those relating to legal services and to schoolteachers, are excluded and in some cases professionals may need to requalify. The OIM can also consider regulatory developments in relation to professional qualifications.

The OIM will also take into account some further factors in identifying potential relevant regulatory developments and which we explain in more detail below:

- the relationship to the NIP

- the relationship to the Common Frameworks programme

The Northern Ireland Protocol

Under the NIP, Northern Ireland remains part of the UK customs territory and is therefore included in UK free trade agreements. However, Northern Ireland must follow the EU’s rules for bringing goods in and out of the EU (the customs code) and many EU single market rules for goods, while GB will set its own customs and regulatory rules. This is explained further in Figure 1.

Figure 1: NIP devolved and reserved / excepted matters

""

Image description: Image showing a map of the UK and Republic of Ireland showing the effects of the NIP on trade flows between Northern Ireland and GB. Qualifying NI goods can be sold in GB under the UKIM Act, but goods from GB to NI must conform to EU standards. Services are not generally affected.

Source: Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS). [footnote 35]

Differences may therefore arise between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK, as the EU adopts regulatory changes that Northern Ireland is required also to adopt; or as GB (or nations in GB) adopt regulatory changes that Northern Ireland cannot follow as a result of the NIP.

The NIP and the OIM’s role

The NIP and legislative provisions which are necessary to give effect to it are outside the scope of the OIM’s functions under the UKIM Act. The OIM therefore cannot produce reports, at the request of any RNA on regulatory provisions which are necessary to give effect to the NIP. Nor can the OIM undertake a review of the NIP (or legislation implementing it) under its broader monitoring functions.

However, it is important to note that the NIP affects only goods moving from GB to Northern Ireland. It does not impact on goods moving from Northern Ireland to GB, nor does it impact the provision of services or the recognition of professional qualifications.

Furthermore, the OIM can potentially provide advice in certain specific circumstances, such as when regulations are made which go beyond what is necessary to give effect to the NIP, or on the impacts of GB divergence with EU law on the UK internal market, or when Northern Ireland is required by the Protocol to remain aligned to the EU. In all circumstances, these would need to be assessed on a case-by-case basis.

For the purposes of this report, we note in developments in the regulatory environment some examples of regulatory developments that may be within scope of the NIP.

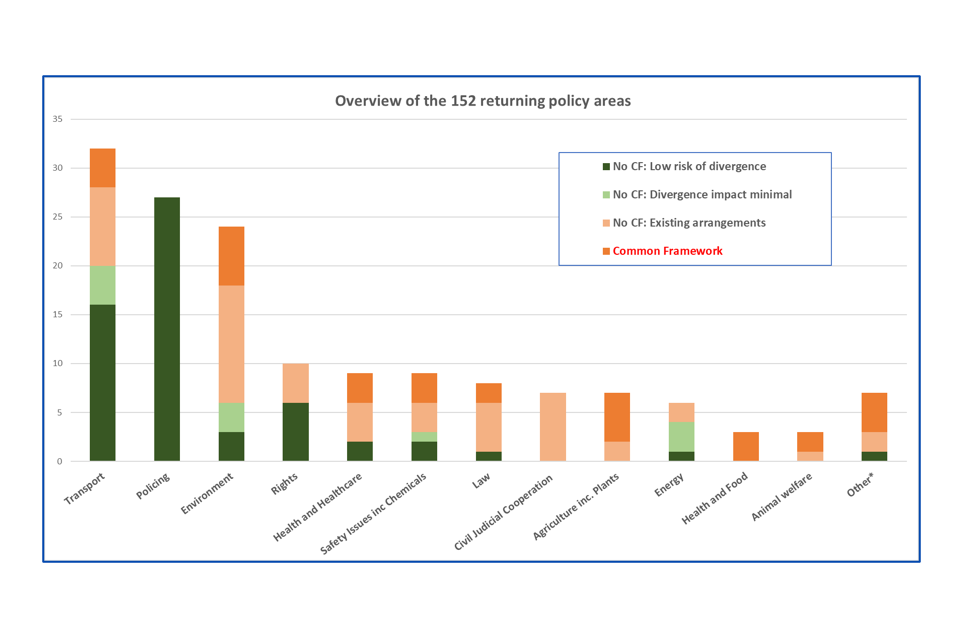

Common Frameworks

Common Frameworks are, essentially, non-statutory intergovernmental arrangements between the UK Government and DAs to establish common approaches to policy areas where powers which have returned from the EU intersect with areas of devolved competence.

In 2017, governments across the UK agreed principles [footnote 36] setting out what Common Frameworks would be and the areas in which they were required after Brexit. Their communiqué defined Common Frameworks:

A framework will set out a common UK, or GB, approach and how it will be operated and governed. This may consist of common goals, minimum or maximum standards, harmonisation, limits on action, or mutual recognition, depending on the policy area and the objectives being pursued. Frameworks may be implemented by legislation, by executive action, by memorandums of understanding, or by other means depending on the context in which the framework is intended to operate.

The Frameworks Division in the UK Government Cabinet Office has coordinated the Common Frameworks programme as a whole, working with governments across the UK. All major decisions are taken by administrations jointly including decisions to sign off the Frameworks at key stages of their development. Framework agreements are also subject to scrutiny by Parliament and the devolved legislatures before they are finally agreed.

In 2021, the Cabinet Office identified 152 areas of EU law that intersected with devolved competence in one or more DAs. [footnote 37] Through collaborative work, the UK Government and DAs have reviewed these policy areas to agree where Common Frameworks are required [footnote 38] and continue to work together to take forward the programme. At the time of writing there are 32 areas where a Common Framework has been or is being developed, covering a range of policy areas and at various stages of delivery (see Appendix D).[footnote 39] To date, one Common Framework has been finalised and fully implemented following scrutiny by all 4 legislatures.[footnote 40] A further 29 Common Frameworks have been provisionally confirmed and of these 26 have been shared with legislatures for Parliamentary scrutiny.

Common Frameworks may set out areas of harmonisation and areas of agreed or accepted divergence. An example is the Food and Feed Safety and Hygiene Common Framework, [footnote 41] which sees all 4 administrations conduct joint risk analysis on food safety but with decisions ultimately taken by each Minister separately, with a possibility of divergence.

Common Frameworks and the OIM’s role

The OIM’s 5-yearly reports will include a review of the impact of Common Frameworks on the UK internal market, and any interaction between the operation of the MAPs and Common Framework agreements.[footnote 42] As we set out in our Operational Guidance,[footnote 43] the scope of this analysis relating to Common Frameworks may include: identifying the relevant regulatory and market conditions in each of the nations; the scope of permitted and actual divergence; the existence, extent and impact of any related exclusions from the MAPs; and assessment of impacts on trade and other economic variables.[footnote 44]

Prior to its launch, the OIM consulted on how it expected to approach the exercise of the internal market functions assigned to it in Part 4 of the Act.[footnote 45] Approximately half of respondents discussed the role of Common Frameworks within the UK internal market. Many advocated a prominent role for them in managing future divergence within the internal market, arguing that this best respected the devolved settlements whilst providing a forum for the effects of divergence to be managed on a pan-UK basis; balancing economic impacts with regulatory autonomy.

Strategic choices about how potential divergence within the internal market is to be managed, and the role of Common Frameworks within that process, are matters for the UK Government working with the DAs.

However, as we set out in our response to the outcomes of the consultation, we are open, within the constraints of our functions under the Act, to exploring with RNAs how best we can support them in the operation of the Common Frameworks process.[footnote 46]

Furthermore, section 10(3) of the Act provides that the Secretary of State may make exclusions from the MAPs to give effect to agreements under Common Frameworks. The UK Government, Northern Ireland Executive, Scottish Government and Welsh Government have developed a process for the consideration of such exclusions, which involves evidence gathering, review and agreement by all 4 governments.[footnote 47]

For this report, we note in developments in the regulatory environment where there may be some interaction between Common Frameworks and some of the regulatory developments we have identified. We will continue to liaise closely with the Cabinet Office and the DAs to understand developments in Common Frameworks and their implications for the UK internal market as well as our role.

Economic overview of the UK internal market

Introduction

This chapter provides an economic overview of the UK internal market.

To provide context, we first describe the relative size and key sectors of the economies of the 4 nations of the UK. We then examine trade flows between the nations (intra-UK trade) based on data published by Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland (England does not yet publish intra-UK trade data). We summarise the key findings by nation and sector, noting the current limitations of the data.

All 4 governments share a common desire to enhance intra-UK trade data for the benefit of policymakers, businesses and consumers. We set out the OIM’s collaborative work with the ONS and the governments of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland to develop the published trade data.

In addition, as part of the ongoing work to improve the evidence base on intra-UK trade, the OIM commissioned its own telephone survey of businesses across the 4 nations. We discuss the methodology, key results and qualitative responses. In addition to this survey, following discussions with the OIM, ONS included 2 questions on intra-UK trade in its Business Insights and Conditions Survey (BICS). We set out the methodology and results.

We conclude by drawing together the emerging themes from the published intra-UK trade data and surveys.

Overview of published economic evidence on the UK internal market

In this section we provide an overview of the key economic data on the UK internal market, including:

- the relative size of the economies of the 4 nations of the UK and the key sectors of their economies

- a summary of evidence sources for intra-UK trade flows as well as an analysis of both recent and historical evidence by nation and by sector of the economy

- ongoing work to enhance intra-UK trade data

The relative sizes and key sectors of the economies of the 4 UK nations

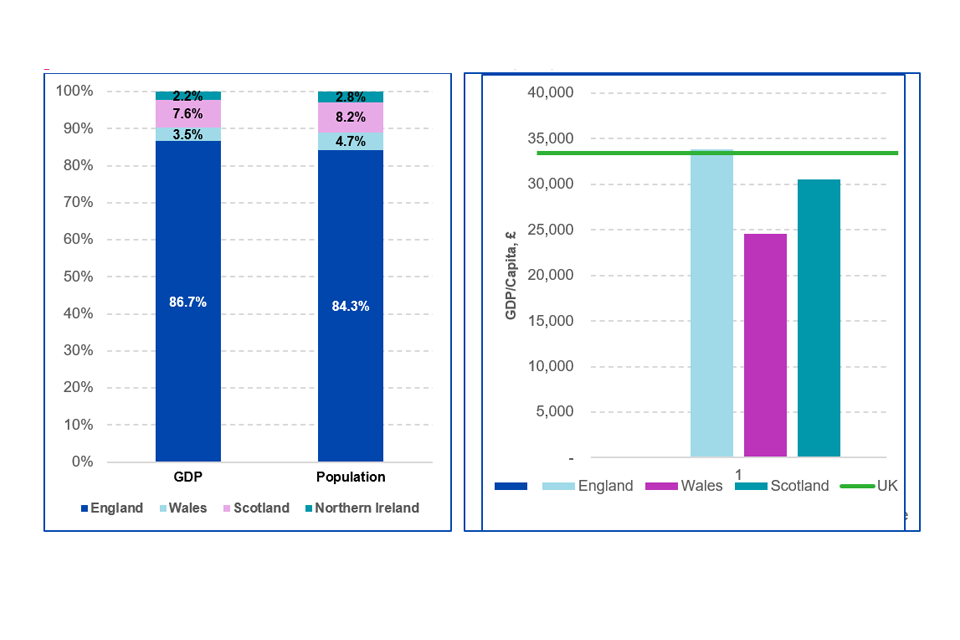

The 4 nations of the UK vary significantly in the size of their populations and economies. Total Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for England in 2019 was £1,903 billion compared to £167 billion in Scotland, £78 billion in Wales and £49 billion in Northern Ireland.[footnote 48] Figure 2 below shows that in 2019 GDP in England accounted for c.87% of total GDP compared with c.8% for Scotland, c.3% for Wales and c.2% for Northern Ireland.

Figure 2: GDP and Population per Nation and GDP / Capita, 2019

""

Image description: 2 sets of bar graphs: The first bar chart shows a breakdown in contribution to UK GDP for each UK nation as well as a breakdown of the population for each. The second bar graph shows the value in GBP £ of each UK nation’s GDP, with the UK average GDP shown horizontally across the bars, for comparison. Figures shown on graphs are included in main text.

Source: ONS Regional economic activity by GDP and population estimates for the UK, 2019.

While the main driver of the differences in GDP is differences in population size,[footnote 49] there are important differences with respect to each nation’s GDP per capita. England had the highest GDP per capita in 2019 at nearly £34,000 per head and is the only nation to have a GDP per capita higher than the UK average. Scotland’s equivalent figure in 2019 was approximately £30,600, but both Northern Ireland and Wales had comparatively lower measures with figures of approximately £25,700 and £24,600, respectively.

Although the magnitudes of the 4 nations’ economies differ, the composition of their economies is relatively similar. All 4 nations are heavily reliant on services, with at least 70% of Gross Value Added (GVA) [footnote 50] in their economies attributed to services.

As illustrated below in Table 1, whilst the available data indicates that no single sector dominates any one economy, we note the following:

-

all 4 economies are heavily driven by service industries, though England and Scotland have a greater reliance on these sectors with over 75% of their respective GVAs within these sectors. Wales comparatively has the smallest reliance on services and the largest reliance on goods, though service sectors still account for over 70% of its economy

-

real estate activities are typically one of the largest components of any individual UK nation’s GVA, accounting for between 11-14% of GVA in each nation[footnote 51]

-

manufacturing, whilst relatively important for all 4 nations, contributed significantly more to the economies of Wales (17% of GVA) and Northern Ireland (13%) than it did to those of Scotland (11%) and England (9%)

-

by contrast, professional and technical activities and financial services comprised a larger share of England and Scotland’s economies (each accounting for around 8% of GVA) compared to Wales and Northern Ireland (around 4% of GVA)

-

the ‘Other’ industries contribute around 20% of each nation’s economy and comprise a range of sectors such as transport and storage, administrative and support service, food and accommodation as well as agricultural and mining related activities.

Table 1: Breakdown of GVA by Industry and UK Nation, 2019

| Industry | England | Wales | Scotland | Northern Ireland |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 1% | 1% | 1% | 2% |

| Mining and quarrying | 0% | 0% | 1% | 0% |

| Manufacturing | 9% | 17% | 11% | 13% |

| Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply | 1% | 2% | 3% | 1% |

| Water supply; sewerage and waste management | 1% | 2% | 2% | 2% |

| Construction | 7% | 7% | 6% | 8% |

| Wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles | 11% | 10% | 9% | 14% |

| Transportation and storage | 4% | 3% | 4% | 4% |

| Accommodation and food service activities | 3% | 4% | 3% | 3% |

| Information and communication | 7% | 3% | 4% | 4% |

| Financial and insurance activities | 7% | 4% | 6% | 3% |

| Real estate activities | 14% | 11% | 12% | 12% |

| Professional, scientific and technical activities | 8% | 4% | 7% | 4% |

| Administrative and support service activities | 6% | 4% | 4% | 3% |

| Public administration and defence | 5% | 8% | 7% | 8% |

| Education | 6% | 6% | 6% | 6% |

| Human health and social work activities | 7% | 11% | 10% | 11% |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | 2% | 1% | 1% | 1% |

| Other service activities | 2% | 2% | 2% | 2% |

| Activities of households | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

Source: ONS Regional Gross Value Added 2019.

Evidence and analysis of intra-UK trade flows

In this section, we set out the sources of evidence on intra-UK trade and provide an overview of intra-UK trade flows by nation. We consider more recent data available in relation to trade between Great Britain and Northern Ireland. We then discuss trade flows by economic sector.

Sources of evidence on intra-UK trade

Before examining intra-UK trade flows and highlighting key findings, we summarise the available sources of published evidence in Box 1. Given the differences in methodologies used to compile intra-UK trade data, and relative lack of comparability across data sources, caution is advised in interpreting the data. Further information about these data sources and their limitations is set out in Appendix E.

As described below, the OIM is working collaboratively with ONS, the governments of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland and the Economic Statistics Centre of Excellence at the Fraser of Allander Institute to develop comparable and robust statistics on intra-UK trade for the benefit of policymakers, businesses and consumers.

Sources of intra-UK trade data

National publications

Intra-UK trade data has historically been relatively limited. Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland each publish details of the value of sales and purchases of goods and services with other UK nations:

- Scotland publishes information on trade with the rest of the UK in its Quarterly National Accounts, Scotland (QNAS) and its annual Export Statistics Scotland (ESS)

- Wales publishes the annual Trade Survey for Wales (TSW), which includes sales to and purchases from each UK nation by either business size or broad sector category

- Northern Ireland publishes annual information on its trade with other UK nations in the Broad Economy Sales and Exports Statistics (BESES)

- England does not publish information on intra-UK trade so it is not possible to compare trade between all 4 UK nations using official or government sponsored statistics.

Surveys

Surveys can provide insights into intra-UK trade. Depending on the scale, frequency and design of a survey, it may also allow more timely evidence to be gathered than the data available from published statistics. Surveys also offer an opportunity to gather qualitative evidence from respondents. As well as the cost involved, key challenges in conducting a survey include obtaining a sufficiently large and representative sample and balancing the need for key insights from businesses against the burdens these questionnaires place on their time and willingness to respond. The OIM has used the ONS’ fortnightly interview of businesses in addition to conducting its own survey of UK businesses for this report; further information is provided below.

Input-Output Analytical Tables

Input-output (IO) and national supply-use tables (SUTs) are national accounting frameworks or matrices that illustrate how domestic production and imports of goods and services are used by industries for intermediate consumption and households for final consumption. Regional SUTs for Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland are not compiled in a regular or co-ordinated manner and there are no existing IO or SUTs for England.

Separate to the national publications, the PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency published a time series of IO tables at a regional level for all European members as of 2010, known as ‘EUREGIO’. More recently the Economic Statistics Centre of Excellence (ESCoE) has developed its own regionalised supply-use tables documenting their understanding of trade between the 4 UK nations as of 2015.

Analysis of intra-UK trade flows

In this section we summarise the published data on intra-UK trade flows. The analysis focuses on 2019 data, the most recent year for which published data is available for each of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Summary of comparative intra-UK trade flows

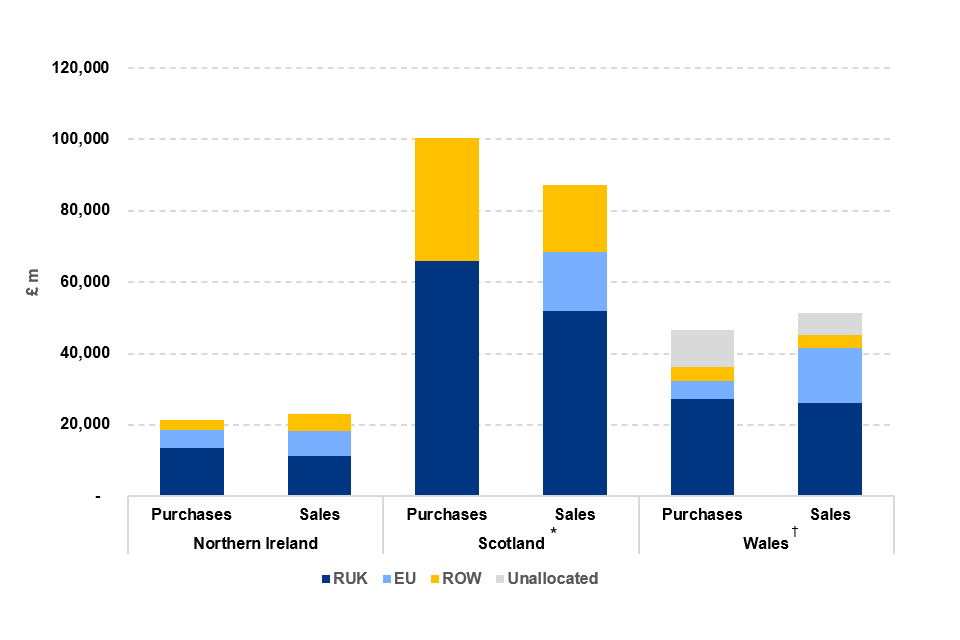

Figure 3 illustrates the total external purchases and sales by origin and destination in 2019 for each of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland using the data in their respective statistical publications. In summary, Scotland has the greatest amount of trade with the rest of the UK in absolute terms with approximately £66bn in purchases (imports) and £52bn in sales (exports), followed by Wales (c.£27bn purchases; c.£26bn sales) and Northern Ireland (c.£13bn purchases; c.£11bn sales). As Figure 3 illustrates, all 3 nations are net importers, purchasing more from the rest of the UK than they sell or export. By inference, this would also suggest that England is a net exporter to the rest of the UK internal market.

Figure 3: Total external purchases and sales by origin/destination in 2019 for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland (£m)

""

Image description: A bar graph that gives a summary of intra-UK trade flows, detailing purchases and sales for each of NI, Scotland and Wales, by origin and destination. Figures are split into those for the Rest of UK, the EU, the Rest of World and Unallocated. The figures show that each of the 3 nations trades more with the Rest of the UK than with other destinations.

Source: Figures for Northern Ireland are taken from the Broad Economy Sales and Statistics, 2019; Figures for Wales are from Trade Survey Wales, 2019; Figures for Scotland are from Quarterly National Accounts Scotland, 2019 and Export Statistics Scotland, 2019.

(*) Scotland’s predominant source for intra-UK trade only covers exports. Imports have been taken from the Quarterly National Accounts Scotland, which does not distinguish between EU and Rest of World trade.

(**) Over 15% (c.£16.5bn) of the value of internal market trade from Wales is ‘unallocated’ where respondents have been unable to allocate this trade to a specific destination therefore these figures are a lower estimate of Welsh trade with the rest of the UK.

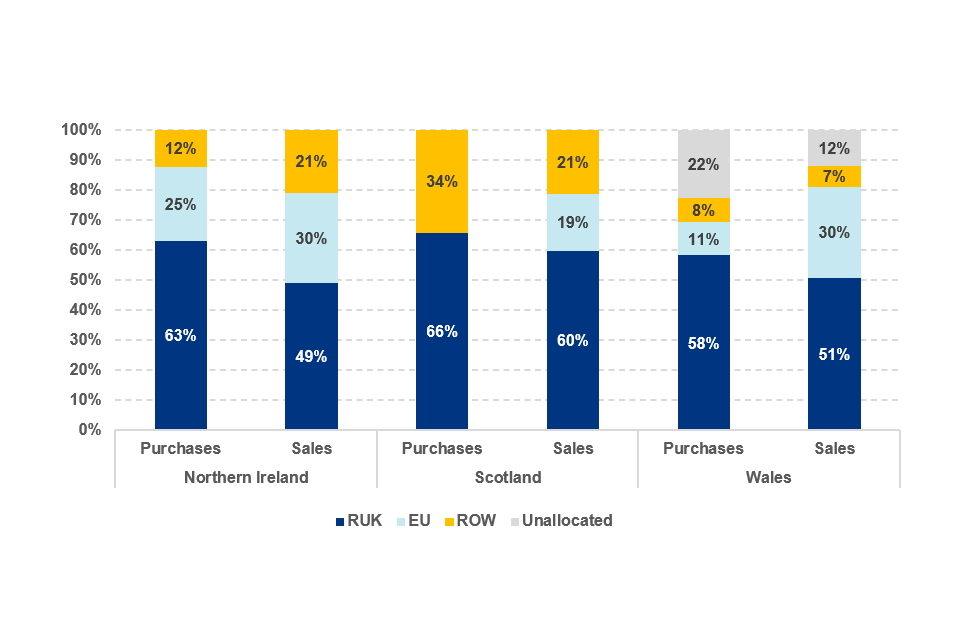

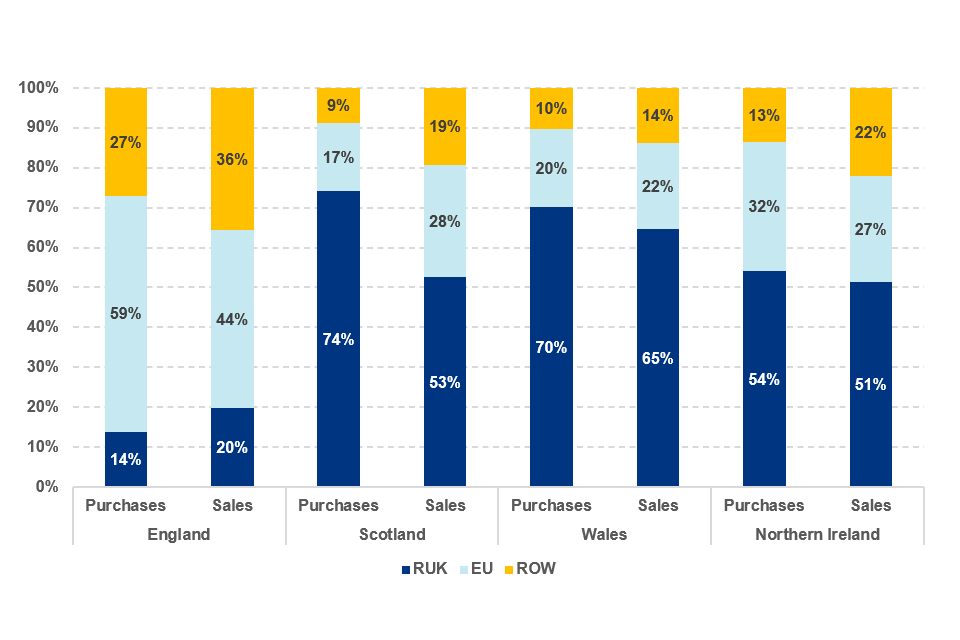

Figure 4: Proportion of external purchases and sales by origin/destination in 2019 for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland (£m)

""

Image description: A bar graph showing 2019 data that for NI, Scotland and Wales, has 2 bars per nations. The first bar for each nation shows the proportion of total purchases split by whether their origin was Rest of UK, EU, Rest of World or Unallocated. The second bar shows the proportions of sales for each nation going to these same destination groups. NI, Scotland and Wales have broadly similar proportions for RUK purchases, with 63%, 66% and 58% respectively. For sales to RUK, NI and Wales have similar figures at 49% and 51% respectively, with Scotland having a higher proportion of RUK sales at 60%.

Source: Broad Economy Sales and Statistics, 2019; Trade Survey Wales, 2019; Quarterly National Accounts Scotland, 2019; Export Statistics Scotland, 2019.

As shown in Figure 4, despite differences in absolute values, in relative terms Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have a broadly similar reliance on the rest of the UK with respect to trade. 66% of Scotland’s external purchases and 60% external sales are from and to other UK nations. For Northern Ireland and Wales, purchases from the rest of the UK are 63% and 58% of total external purchases, respectively, and, for both nations, sales to the rest of the UK are around a half of external sales.

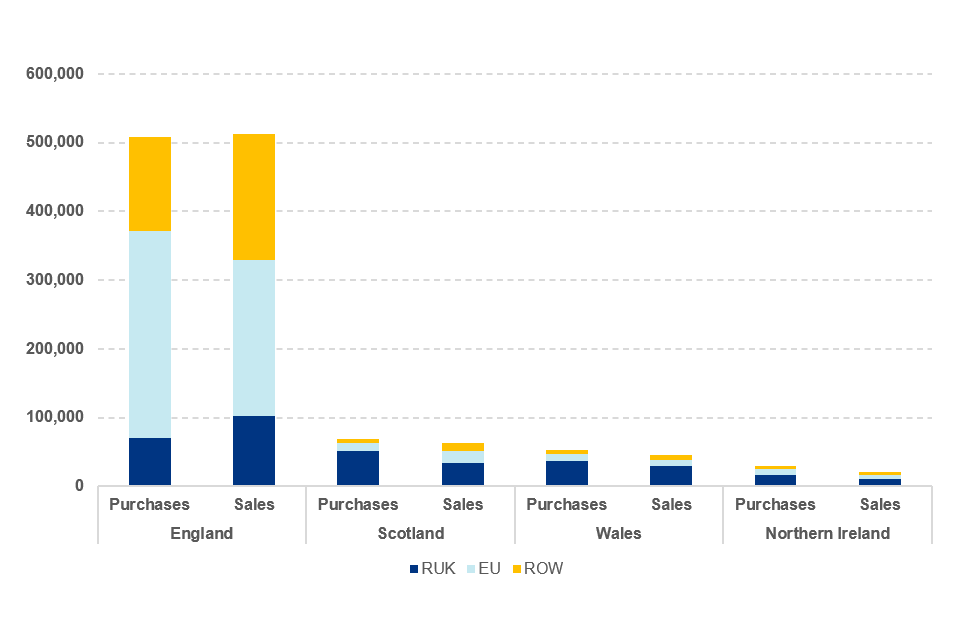

As also illustrated by Figure 4 and as discussed above, there are no corresponding intra-UK trade measures for England as of 2019. However, we can infer trade values and proportions for firms in England using 2 sources, the EUREGIO database, which estimate figures for intra-UK and external trade as of 2010 and the ESCoE publication in 2021,[footnote 52] which estimates intra-UK sales as of 2015. These are presented in Figures 5 to 8.

Figure 5: 2010 estimates of intra-UK trade

""

Image description: A bar graph of 2010 EUREGIO data that for each UK nation, shows estimates of purchases and sales in £s split between RUK, EU and ROW. The data shows significantly higher value purchases and sales for England compared with Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. England traded proportionally more with the EU and ROW, than did the other UK nations who traded more within the RUK.

Source: EUREGIO 2010.

Figure 6: 2010 estimates of proportions of intra-UK trade

""

Image description: A bar graph of 2010 EUREGIO data that for each UK nation, shows estimates of the proportions of the total purchases and sales for each origin/destination of RUK, EU and ROW. England trades proportionally more with the EU and ROW than with RUK with only 14% of purchases from RUK and 20% sales to RUK. In contrast, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland show RUK purchases of 74%, 70% and 54% respectively, and show sales to RUK of 53%, 65% and 51% respectively. Northern Ireland bought more from the EU than the other devolved nations at 32%, compared to Scotland’s 17% and Wales’s 20%.

Source: EUREGIO 2010.

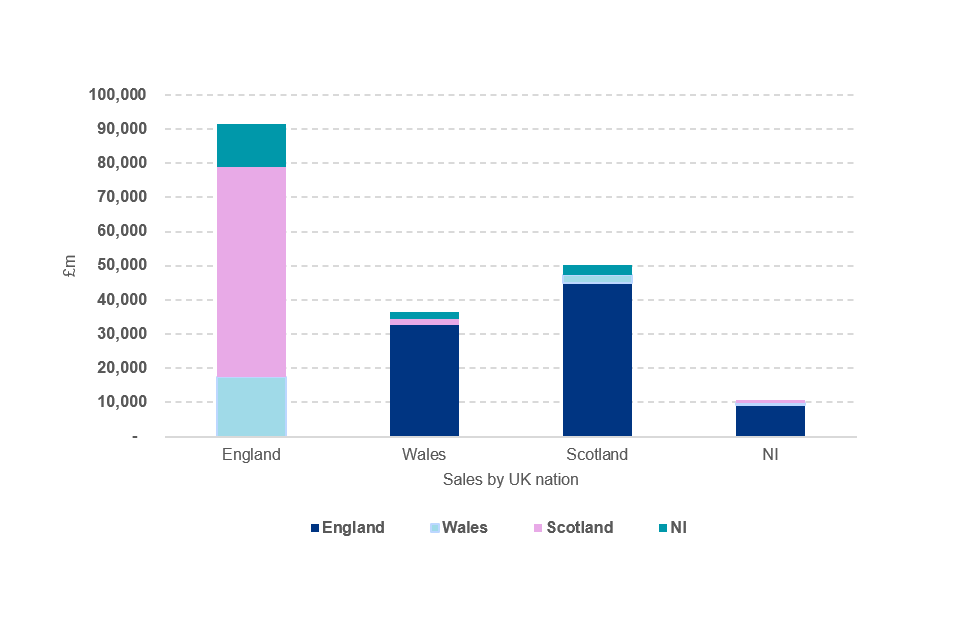

Figure 7: 2015 estimates of intra-UK sales by UK nation[footnote 53]

""

Image description: A bar graph of 2015 ESCoE data showing the value of sales in £s that each UK nation sold to each of the other UK nations. England sales to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland were around £61m, £17.5m and £13m respectively. Scotland sales to England, Wales and Northern Ireland were around £45m, £2m and £3m. Wales sales to England, Scotland and Northern Ireland were around £33m, £2m and £2m respectively. Northern Ireland sales to England, Scotland and Wales were around £9m, £1m and £0.4m respectively.

Source: ESCoE (2021) (excludes non-resident flows).

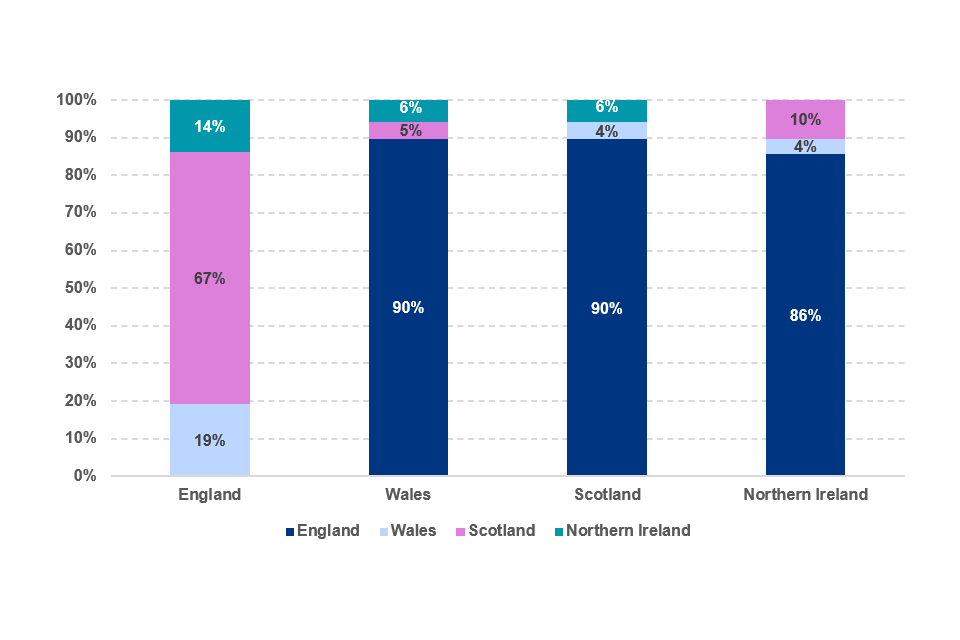

Figure 8: 2015 estimates of proportions of intra-UK sales

""

Image description: A bar graph of 2015 ESCoE data showing estimates of the proportions of total sales that each UK nation sold to the other UK nations. The figures reflect the relative sizes of the national markets, with Scotland, Wales and NI selling mostly to England, with the proportions being 90%, 90% and 86% respectively. England sells most to Scotland at 67%, followed by to Wales at 19%, and least to NI at 14%.

Source: ESCoE (2021) (excludes non-resident flows).

We draw the following key conclusions from the trade data published by the devolved nations and both the ESCoE and EUREGIO data.

-

as illustrated in Figure 7 conservative estimates of all 4 UK nations sales would suggest intra-UK exports are worth around £190bn.[footnote 54] Comparable figures for UK international exports indicate that the UK sold £512bn of goods and services internationally,[footnote 55] which suggests that intra-UK exports could represent over one-quarter of all UK exports (both intra- and extra-UK exports)

-

the significant disparity in the size of England’s economy and the size of those of the other UK nations is reflected in a significant difference in their patterns of trade. Whereas intra-UK trade accounts for the majority of trade for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, only a small proportion of England’s trade is with the other UK nations. This is not surprising given that, for England, the other UK nations represent a relatively small market, whereas for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, England represents a large and geographically close market which accounts for the bulk of their intra-UK sales

-

all 3 devolved nations are net importers within the UK, purchasing more from the other UK nations than they sell to them. England is a net exporter to the other UK nations

The variation in importance of economic trade is also reflected in the proportion of GDP that intra-UK trade represents. Using the 2010 EUREGIO data and 2010 GDP estimates, imports into England from the rest of the UK represented around 5% of GDP. By contrast, this figure was over 40% for Scotland and Northern Ireland and over 60% for Wales. Caution should be exercised when drawing any conclusions with this dataset given both the considerable data lags and the challenges of generating trade data.[footnote 56] However, the data serves as a useful indication of the relative importance of trade to various UK nations.

Recent data on trade between Great Britain and Northern Ireland

Media coverage of trading patterns between Great Britain and Northern Ireland over the last year placed increased scrutiny over this aspect of intra-UK trade.

Whilst analysis of the NIP remains out of scope for the OIM, trade between GB and Northern Ireland is an important aspect of the UK internal market. We have therefore considered the availability of more recent evidence on trade between GB and Northern Ireland.

As noted above, at the time of publication of this report, the most recent and robust intra-UK trade data from official devolved nation sources covers trade to 2019, which precedes any effects of the NIP, the pandemic or Brexit. There are some more recent sources of evidence including the Northern Ireland Manufacturing Survey and data on trade between the Republic of Ireland and both Northern Ireland and Great Britain published by the Republic of Ireland’s Central Statistics Office. However, both sources have limitations in relation to estimating trade between Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

Given the paucity of data sources and their limitations, the picture is far from definitive at this stage. More data will become available in December 2022 when NISRA publishes the BESES exports data for 2021, followed in March 2023 by data on imports and a split by goods and services.

Trade flows by sector

Table 2 breaks down trade for each of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland by broad industry type alongside a comparison of the respective GVA or economic make up for each nation.

Table 2: Proportion of trade and GVA by broad industry group, 2019

| Broad Industry Group | Northern Ireland GVA | Northern Ireland Trade | Scotland GVA | Scotland Trade | Wales GVA | Wales Trade |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Sector and utilities | 5% | 2% | 7% | 20% | 5% | 15% |

| Manufacturing | 13% | 39% | 11% | 21% | 17% | 38% |

| Construction | 8% | 17% | 6% | 3% | 7% | 7% |

| Trade, accommodation and transport | 21% | 29% | 17% | 19% | 16% | 25% |

| Business and other services | 53% | 14% | 59% | 37% | 55% | 15% |

Source: Broad Economy Sales and Statistics, 2019; Trade Survey Wales, 2019; Quarterly National Accounts Scotland, 2019; Export Statistics Scotland, 2019, ONS Regional Gross Value Added 2019.

The importance of intra-UK trade to the UK economy is clear from the data collected by the devolved nations, with nearly £90bn in exports and over £100bn in imports reported by the devolved nations in 2019. As illustrated by Table 2, we conclude the following:

-

reliance on intra-UK trade in services varies considerably across Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Whilst all 3 nations rely heavily on services sectors in terms of GVA (comprising 70 to 80% of economic output) [footnote 57], services sales from Northern Ireland and Wales to the rest of the UK account for a significantly lower proportion (approximately 40%) of intra UK sales than for Scotland (approximately 60%)

-

almost 40% of Scotland’s sales to the rest of the UK are business services. This figure is over twice that of Northern Ireland’s or Wales’s equivalent trading proportions. This larger concentration in business services may be explained by the size of Scotland’s financial services industry

-

almost 40% of Northern Ireland’s and Wales’ sales with the rest of the UK were in manufactured goods. As noted, these industries accounted for a larger proportion of GVA compared to Scotland and England

-

20% of all of Scotland’s and 15% of all of Wales’s sales to the rest of the UK were in primary sector goods and utilities. In Scotland, this figure is driven by the oil and gas industry. In Wales, the figure is underpinned by a relatively bigger agricultural sector

Ongoing work to enhance intra-UK trade data

As part of its remit to facilitate the operation of the internal market, one of the OIM’s primary contributions includes the collation, analysis and dissemination of evidence to develop understanding of intra-UK trade. This includes 2 surveys:

- the OIM’s own-initiative survey

- inclusion of intra-UK trade questions in BICS

In addition, the OIM’s ongoing projects to improve intra-UK trade data include:

-

collaborating with the governments of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland to find ways to enhance intra-UK trade statistics

-

collaborating with ONS on its work to investigate sources of data that might contribute to the estimation of intra-UK trade. We are advising on data collection and analysis and taking part in the ONS chaired sub-national working group, which also includes HMRC and statisticians from the Scottish, Welsh and Northern Ireland Governments

-

engaging with academics at ESCoE at the Fraser of Allander Institute, University of Strathclyde, who are working to develop intra-UK trade statistics

-

gathering intelligence on internal market developments, including through our digital reporting service

Evidence from BICS

BICS is a voluntary fortnightly business survey conducted by ONS to deliver real-time information to help assess issues affecting UK businesses.[footnote 58] BICS is a large-scale survey, sent to around 39,000 businesses with each wave typically receiving around 8,000 to 9,000 responses. Samples are drawn from the Inter-Departmental Business Register (IDBR) which covers around 2.7 million businesses with a broad coverage of business sectors and sizes. ONS included 2 questions[footnote 59] on intra-UK trade in the BICS Wave 47 survey,[footnote 60] relating to: (i) sales of goods or services to customers in other UK nations; and (ii) whether businesses were experiencing challenges in trading with customers in other UK nations. We received input from analysts in all 4 nations on the design of the questions. This section summarises the results and further detail is set out at Appendix F.

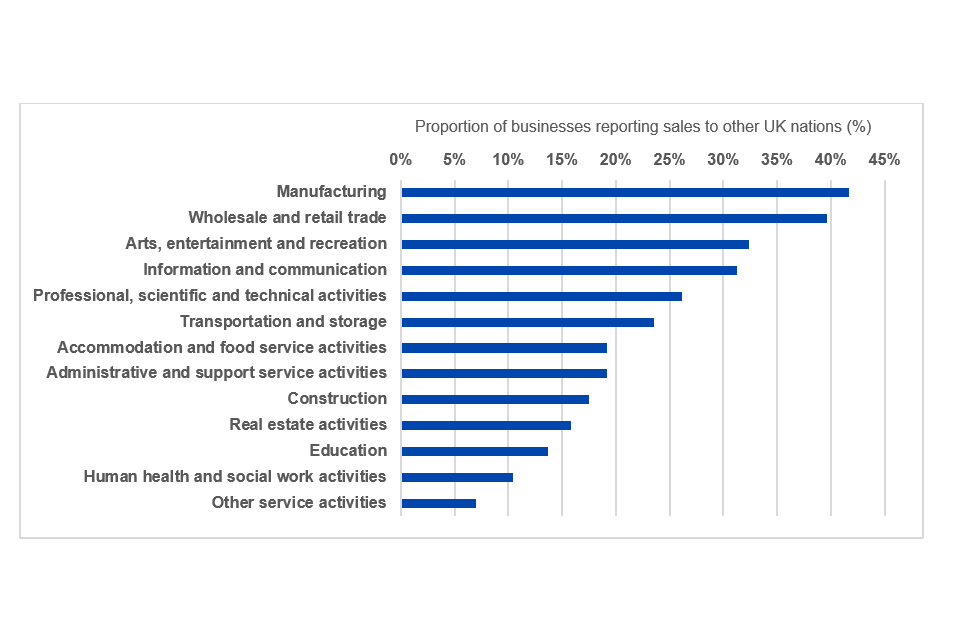

Based on weighted responses[footnote 61] to the survey, an estimated 26% of businesses were able to estimate the proportion of goods or services they sold to customers in other UK nations in the last 12 months. This is likely to underestimate the total proportion that sold goods or services to customers in other UK nations as a further 9% answered ‘not sure’ to the question and some of these are likely to have made sales but be unable to estimate the proportion.

Figure 9 shows the proportion that provided percentages of their sales to other UK nations by industry.[footnote 62] This shows significant variation between sectors, from around 10% for human health and social work and just 7% for other service activities to 40% for Wholesale / Retail trade and 42% for Manufacturing.

Figure 9: Proportion of businesses reporting estimated sales to other UK nations, by industry

""

Image description: A bar graph of the OIM’s analysis of BICS Wave 47 data showing the proportion of businesses reporting estimated sales to other UK nations, split by industry. Manufacturing was the sector with the highest proportion of sales, with 42%; and wholesale and retail trade was the second with 40%.

Source: OIM analysis of BICS Wave 47 data.

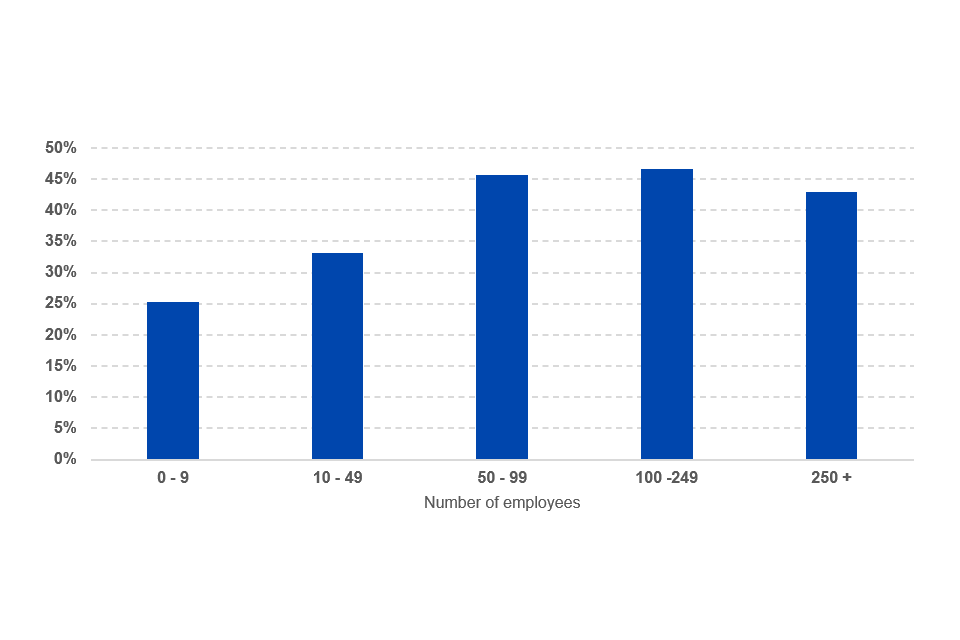

As shown in Figure 10 below there was a positive relationship between the proportion of businesses trading with other UK nations and company size. The estimated proportion trading and estimating a percentage was 35% [footnote 63] (with a further 11% ‘not sure’) when the smallest companies (those with 0 to 9 employees) are excluded.

Figure 10: Proportion of businesses with sales to customers in other UK nations, by size band (employees)

""

Image description: A bar graph of the OIM’s analysis of BICS Wave 47 data showing the proportion of businesses with sales to other UK nations, split by size band (number of employees). Businesses with 50 to 99 employees, or with 100 to 249 employees, were most likely to have said they had sales to customers in other UK nations.

Source: OIM analysis of BICS Wave 47 data.

The data generated by the BICS questions does not include specific sales value or destination estimates and does not facilitate estimation of aggregate intra-UK trade flows. Doing so would require a more sophisticated survey, for example of the types undertaken by the DAs in the preparation of their annual trade reports.

Of those businesses which traded with customers in other UK nations, 10% said that they were experiencing challenges in doing so. By industry sector, the highest were: Accommodation and food service (21%); Transportation and storage (16%); and Manufacturing (16%). There was no clear relationship with business size, with a range from 7% (businesses with more than 250 employees) to 11% (50 to 99 employees). In the absence of further follow-up questions, it is not possible to identify the specific nature of trading challenges, which could feasibly include the COVID pandemic, supply chain disruption, transport logistics disruption, as well as any barriers arising from regulatory divergence.

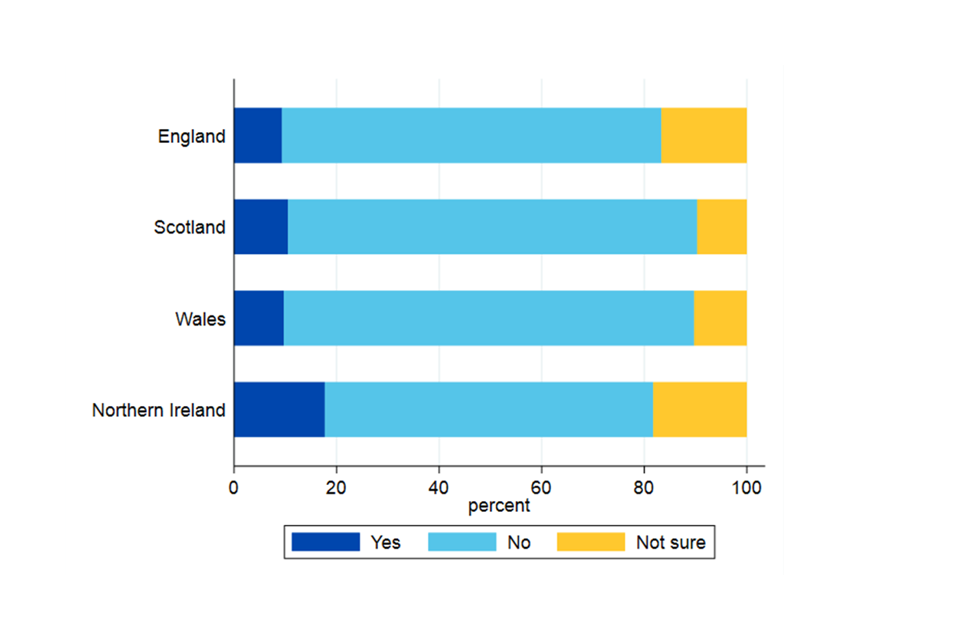

A breakdown by nation, as illustrated in Figure 11, would appear to show a higher proportion of businesses in Northern Ireland experiencing challenges trading across borders.[footnote 64] However, it should be noted that there is great deal of uncertainty in these estimates.[footnote 65] The small numbers of responders in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, together with differences in the sizes of businesses within each sector across the 4 nations, results in a very small effective sample size. This suggests that BICS data is not suitable for obtaining good country-level estimates.

Figure 11: Percentage of businesses experiencing challenges across borders

""

Image description: A bar graph of the OIM’s analysis of BICS Wave 47 data showing the percentages of businesses experiencing challenges trading across UK borders. Businesses responded ‘Yes’, ‘No’ or ‘Not sure’ as to whether they were experiencing challenges across borders.

Source: OIM analysis of BICS Wave 47 data.[footnote 66]

The OIM’s survey

To complement the quantitative analysis discussed above on existing intra-UK trade, we conducted a survey of businesses.

The survey was primarily designed to gain insights into the prevalence of UK businesses selling goods and services across national borders within the UK internal market, these firms’ experiences of trading across the UK and their awareness of regulatory issues that might act as a barrier to trade. It also sought to establish an indication of the extent to which businesses are familiar with the concepts of UK internal market trade. In addition to providing a richer evidence base, the survey was also an opportunity for the OIM to understand better the extent to which surveys can be used as a means of examining intra-UK trade.

The OIM survey was a telephone interview of 582 businesses.[footnote 67] The survey was not intended to cover a representative sample but rather to collate a wide range of views across all UK sectors.[footnote 68] As a result, smaller regions and industries have been oversampled to provide a minimum level of representation. Further information on the sampling approach and the questionnaire can be found in Appendix G together with the data tables setting out the responses.

The following paragraphs highlight the key themes that emerged from the responses. As the sample design was not intended to be representative of the wider population we focus on a qualitative interpretation of the results.

Overview of the survey results

Of the 582 businesses surveyed, 337 traded with other UK nations, of which 173 traded goods but not services with other UK nations, 114 traded services but not goods and, 50 traded both goods and services with other UK nations. The following paragraphs highlight the key themes that emerged from the responses.

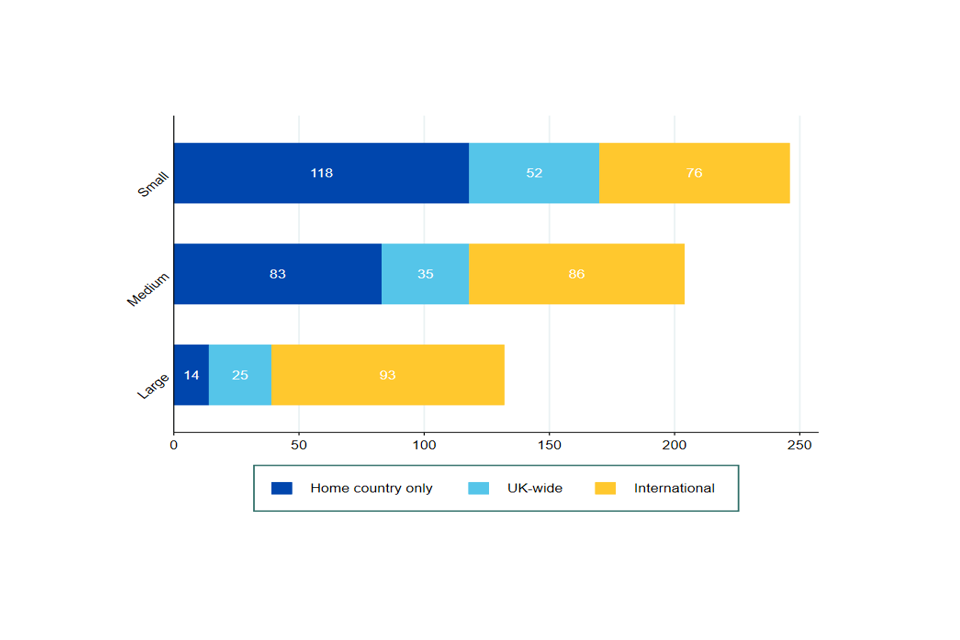

Larger firms were more likely to trade across the UK. Almost all large firms (250+ employees) traded outside their own nation (trading either UK-wide or internationally). In contrast, almost half of the small firms in our survey did not trade outside the nation they were based in (Figure 12).

Figure 12: Number of businesses trading within their home country or across borders[footnote 69] [footnote 70]

""

Image description: A bar graph of OIM survey data showing the number of businesses trading solely within their home nation, as well as the number whose trade is UK-wide, and those which trade internationally, split by business size of small, medium and large. Small firms had 118 firms trading solely in their home nation, 52 UK-wide, and 76 internationally. Medium firms’ figures were 83 home nation, 35 UK-wide, and 86 international. Large firms had 14 home nation, 25 UK-wide, and 93 traded internationally.

Source: OIM telephone survey of businesses.

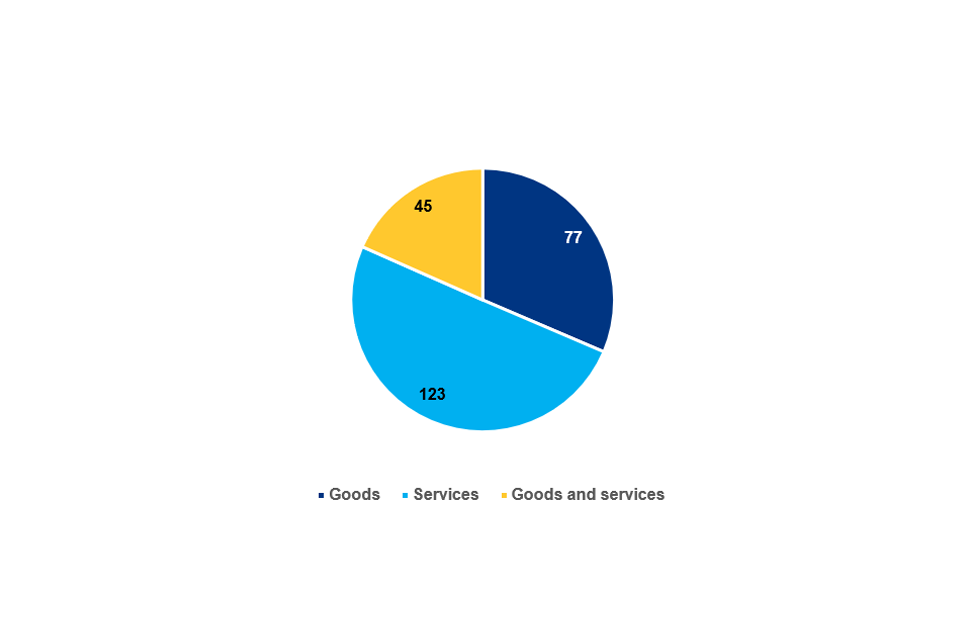

Of the 582 firms who responded, 245 did not engage in any intra-UK trade. Over half of these businesses were exclusively service providers and many of these businesses noted the local nature of their demand, with pubs, restaurants or hairdressers all responding along similar lines (see Figure 13). A similar theme was noted for goods producers too, although for goods producers a key factor making markets local was that transport costs made their products uncompetitive when travelling across large distances.

Figure 13: Number of businesses who do not trade across UK nations

""

Image description: A pie chart of OIM survey data showing the breakdown of the 245 businesses who do not trade across UK nations split by whether they provide goods, services or both. The largest number was for those providing services at 123 businesses, followed by 77 businesses providing goods, with 45 businesses providing both goods and services.

Source: OIM telephone survey of businesses.

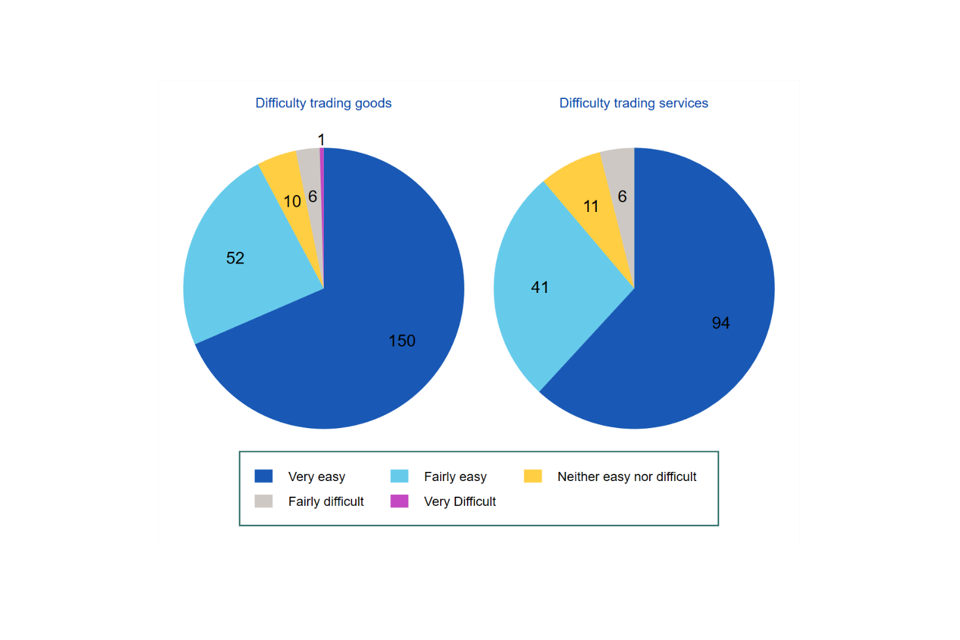

Most of the respondents that trade with other UK nations said that doing so was either fairly or very easy. Figure 14 shows that only 7 of the 223 businesses who sold goods between UK nations and only 6 of the 164 businesses selling services said trading with other UK nations was difficult.

Figure 14: Difficulties trading with other UK nations[footnote 71]

""

Image description: 2 pie charts of OIM survey data showing level of difficulty trading with other UK nations experienced by businesses. The first pie chart shows data for businesses trading goods, with 150 finding trading very easy, 52 fairly easy, 10 neither easy nor difficult, 6 fairly difficult and 1 very difficult. For businesses trading services, 94 found trading very easy, 41 fairly easy, 11 neither easy nor difficult, 6 fairly difficult and none very difficult.

Source: OIM telephone survey of businesses.

Those who highlighted difficulties mentioned general difficulties in selling to another country rather than regulatory differences. For example, a medium-sized English luxury packing business highlighted that people had a preference for local companies. An English maritime scientific company stated that although they were not aware of any regulations requiring Scottish companies to procure marine consultancy services locally, they now have very few Scottish clients given that there is now a presumption in favour of local Scottish suppliers. Although it was outside the scope of the survey, some firms mentioned the NIP as a barrier to trade.

A notable number of firms identified some existing differences in regulations already likely to affect their sales of goods or services.[footnote 72] Of the 337 businesses who engage in trade with other UK nations, 42 identified existing differences in regulations that affect their sales.[footnote 73] For these, the most frequently cited issues were in the following areas:

-

building regulations, including in relation to health and safety – mainly referred to by large- and medium-sized businesses in the construction and manufacturing sectors in Scotland, England and Northern Ireland

-

legal services and the law, especially between Scottish and English law – mainly cited by a mix of businesses in the legal, finance and IT sectors

-

regulations relating to food and drink, including ingredients, nutrition and alcohol policies (such as Minimum Unit Pricing) – cited by medium and large producers and accommodation providers

-

regulations relating to environmental policies, including water regulation, waste disposal and deposit return schemes mainly cited by medium and large business in the agriculture, waste disposal and retail sectors

The numbers are small but provide an indication that some businesses consider that they are already managing regulatory differences in their work and, in some cases, this may have impacted how they operate.[footnote 74] In developments in the regulatory environment we identify potential new regulatory developments in a number of these areas, including regulations relating to energy use for new builds and to policies relating to food and alcohol.

A slightly smaller number of firms identified anticipated policy and regulatory differences that may affect the sales of their goods or services. Of the 337 businesses who traded with other UK nations, 29 referred to examples of potential differences.[footnote 75]

The most frequently cited topic was the potential for future independence referendums and how this might impact on trade. However, in terms of new regulatory developments, some respondents identified similar themes to those noted above – including food policies, alcohol pricing and building regulations. Some additional specific issues noted by the respondents included expectations in relation to environmental developments and policies relating to packaging, recycling and single-use plastics. Again, these are issues that we address further in our analysis of regulatory developments in developments in the regulatory environment.

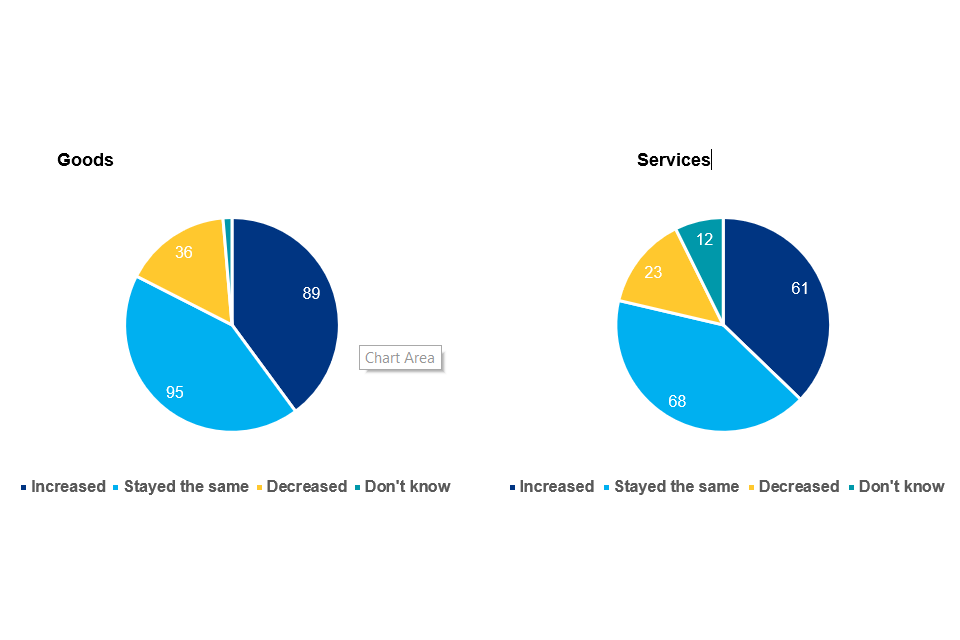

Of the businesses who traded with other UK nations, most noted trade had either stayed the same or increased over the past year (Figure 15). Of the 223 goods producers who traded with other UK nations, 184 noted they had seen either no change or an increase in their level of trade over the last 12 months. For services providers, 128 of the 164 businesses who traded across UK nations saw no change or an increase in their intra-UK trading activity.

Figure 15: Businesses reporting changes to the level of intra-UK trade over last 12 months[footnote 76]

""

Image description: 2 pie charts of OIM survey data showing whether businesses reported changes to the level of intra-UK trade over the last 12 months, broken down by good and services. Of the 223 good producers, 89 said it had increased; 95 that it had stayed the same; 34 that it had decreased and 3 did not know. Of the 164 service providers, 61 said it had increased; 68 that it had stayed the same; 23 that it had decreased and 12 did not know.

Source: OIM telephone survey of businesses.

The pandemic was cited by different respondents as an important driver for both increases and decreases in internal market trading activity. 22 of the 89 goods producers and 21 of the 61 services producers who responded experienced an increase in sales to customers in other UK nations. Illustrative of firms who experienced an increase in their intra-UK sales was a small Scottish manufacturing business who noted that the furniture industry had boomed during lockdown due to people buying within the UK. Similarly, a small English information and communication business highlighted that internet services have been in more demand due to more people working from home; it also noted that the closure of holiday parks allowed technology upgrades ahead of a subsequent holiday boom.

Of those firms who experienced a decline in sales to customers in other UK nations, 24 of the 36 goods producers and 18 of the 23 services providers explained Covid or the pandemic was responsible. This included businesses such as a large English transport and storage company who sold aircraft parts and supported airline services and noted that flight groundings had negatively affected intra-UK sales.

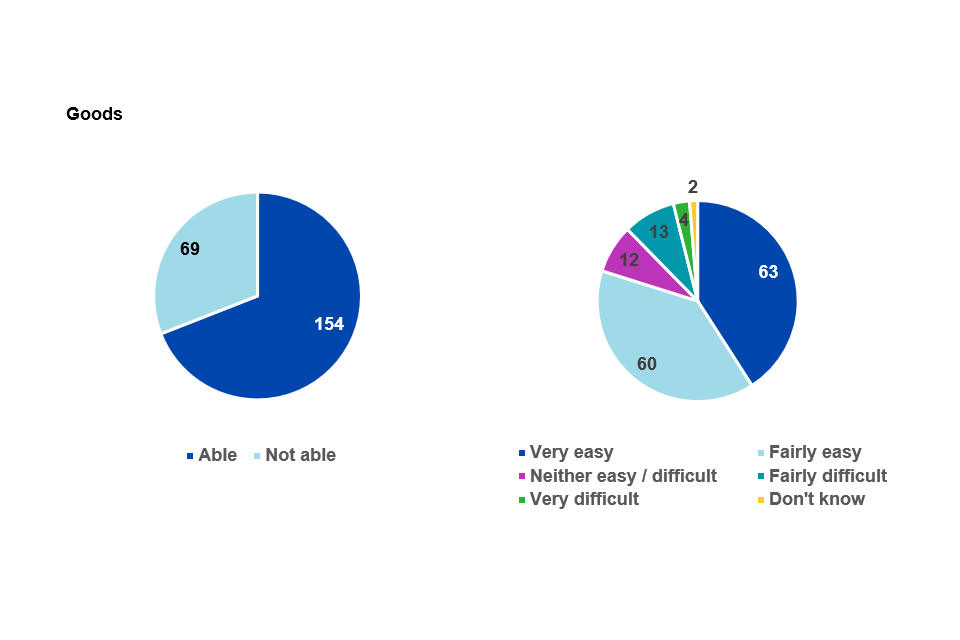

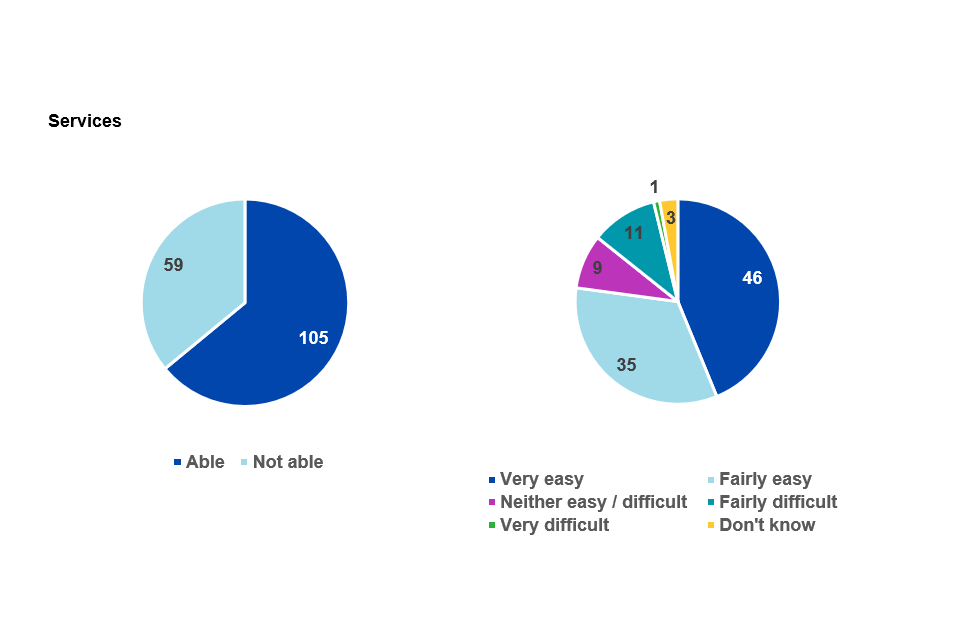

A majority of respondents that traded across UK nations were able to quantify the proportion of the sales that were traded, and most of them found it either very or fairly easy to do so (Figure 16). However, 69 out of 223 goods producers and 59 out of 164 services producers were unable able to estimate their proportions of intra-UK trade. A further 17 of the 152 goods producers and 12 of the 102 services providers said it was either fairly or very difficult to quantify proportions.

Figure 16: Number of business able to quantify proportions of sales to UK nations and the ease of providing these breakdowns for those who could [footnote 77] [footnote 78]

""

""

Image description: 4 pie charts, with 2 each for goods and for services. In each pair of charts, one shows the number of businesses able to quantify proportions of sales to UK nations, and the other shows how easy it was to provide this breakdown, for those who could. For goods, 154 businesses were able to provide a breakdown, and 69 could not. Of those who could do so, 123 found it either very easy or fairly easy to do so. For services, 105 businesses were able to quantify goods sold to UK nations and 59 could not. Of those who could, 81 found it either very easy or fairly easy to do so.

Source: OIM telephone survey of businesses.

There were 2 main reasons that respondents gave for finding it difficult to quantify the proportion of their sales that were traded. The first was that they did not know who their end customers were, for example because their sales went to a distribution centre which may supply across the UK nations. The second was that they did not have information systems that allowed them to extract data by nation. Similarly, having information systems that can readily generate the data was frequently mentioned as a reason why it was easy to quantify the proportion of sales that are traded. Interestingly, there was some evidence that larger firms found it more difficult to quantify intra-UK trade - 28 out of 69 goods producers and 30 out of 59 service providers that were unable to estimate their proportions by UK nation were large firms.[footnote 79]

For the 154 goods respondents and 105 services providers who said they were able to estimate their proportions, a number of key themes emerged. These included having large bespoke products that warranted knowledge of their customers location, dealing with specific individuals or having a relatively limited number of consumers which meant it was easier to calculate proportions of sales manually.

The fact that a sizable minority were unable to estimate the proportion of their sales that are traded suggests that there are likely to be challenges in using surveys of this size and nature to carry out whole economy estimates of intra-UK trade flows. It may also be useful to explore further whether the challenges faced, in particular those around not knowing the final customer, are particularly prevalent in certain sectors.

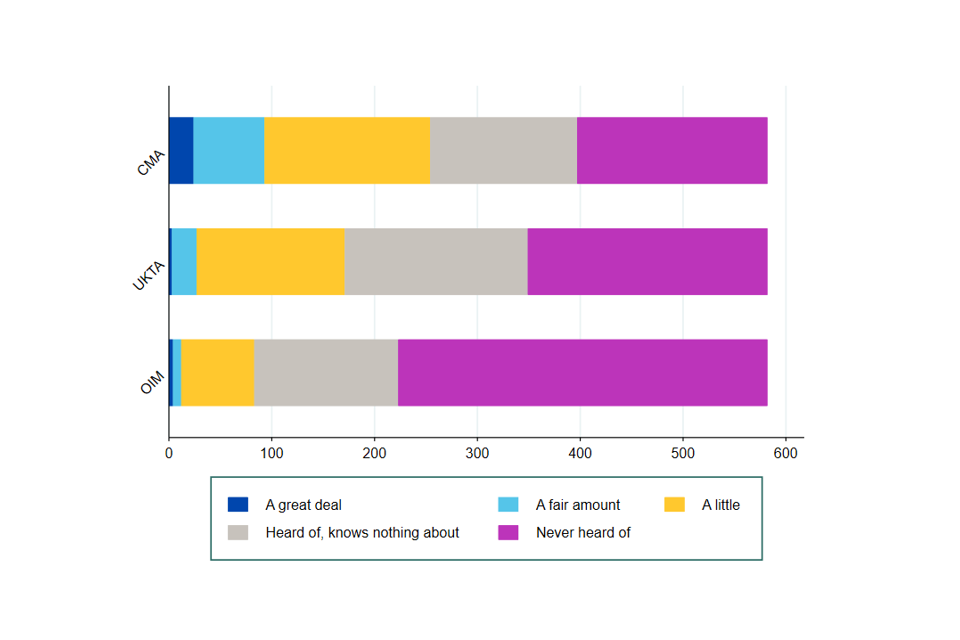

The survey also offers insights into the general awareness of institutions and intra-UK trade policy. Most respondents were unaware of the OIM, with 359 of the 582 respondents saying they had never heard of the OIM and 71 of the 83 that said they had heard of the OIM, saying they knew little or nothing about it (Figure 17). This number was almost twice as large as the number of respondents who were unaware of the CMA. While this is not altogether surprising given that the OIM only officially launched in September 2021, it does highlight the importance of the OIM continuing to engage with stakeholders to communicate its role. We note that a significant proportion of respondents said they were aware of a fictitious organisation called the UK Trade Agency (indeed more than said they were aware of the OIM) which suggests there may be inherent biases in questions of this nature which makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions from these results.

Figure 17: Awareness of the OIM

""

Image description: A bar graph showing the awareness of businesses of 3 organisations: the OIM, the CMA, and the fictitious UKTA. Over 61% had never heard of the OIM, with 12% saying they had heard of the OIM but knew little or nothing about them. The remaining 27% of businesses stated they knew either a fair amount or a great deal about the OIM. The fictitious UKTA had responses showing it was better known than the OIM, and the CMA was familiar to the largest number of businesses.

Source: OIM telephone survey of businesses

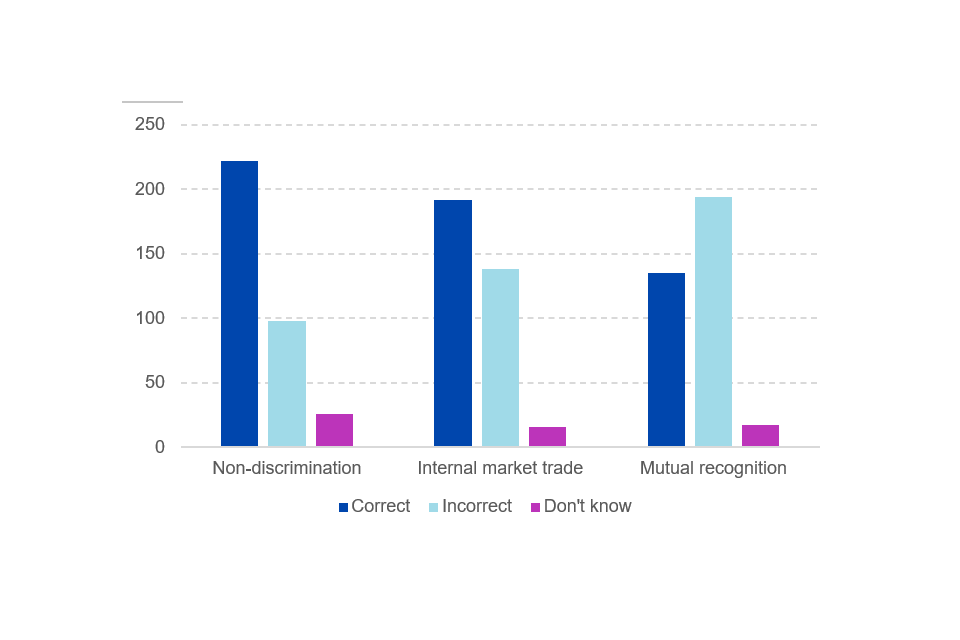

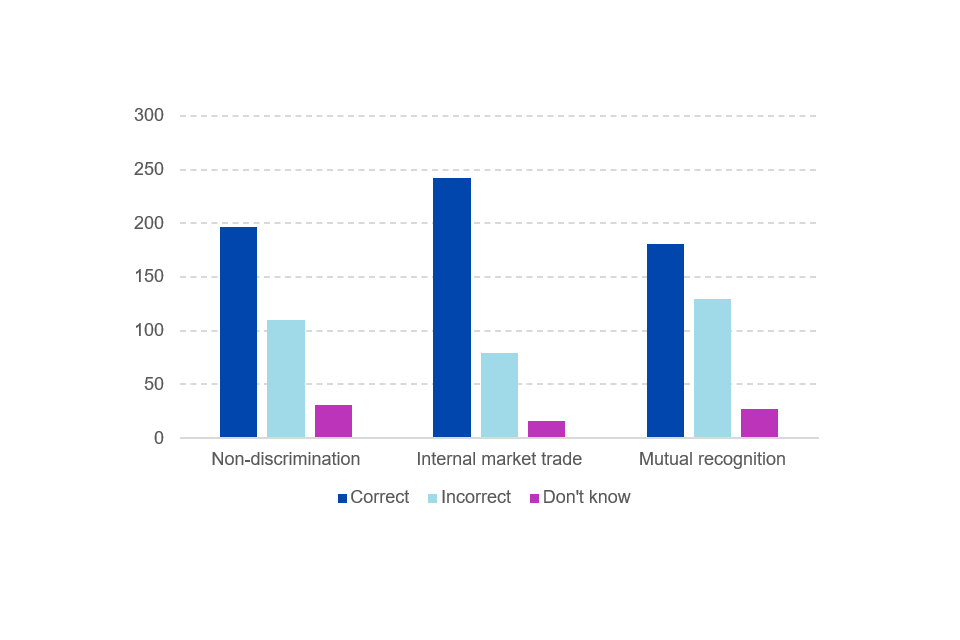

The survey also examined awareness of the MAPs by providing respondents with a series of statements and asking them to select the answers they believed to be correct. Respondents were asked questions on non-discrimination, the ability of regulations to vary between UK nations and on the mutual recognition principle. While a significant number of both goods and services respondents answered at least one question on the MAPs correctly, the proportions answering the mutual recognition question correctly are low - indeed for goods producers more respondents gave the incorrect answer.[footnote 80]

As illustrated in Figure 18, of the 347 goods producers, 222 answered the question on non-discrimination correctly,[footnote 81] 192 correctly answered the question on internal market trade[footnote 82] and 135 answered the question on mutual recognition correctly.[footnote 83] As Figure 19 illustrates, of the 341 service providers, 197 answered the question on non-discrimination correctly,[footnote 84] 242 answered the question on internal market trade correctly[footnote 85] and 181 answered the question on mutual recognition correctly.[footnote 86]

Figure 18: Goods producers awareness of the MAPs

""