Interim report

Published 22 October 2021

Applies to England, Scotland and Wales

Summary

This report provides an update on the interim findings from our children’s social care market study. These findings are based on our initial analysis and therefore do not necessarily reflect the positions we will reach in our final report. We are currently just over halfway through our study and will publish our final report by the statutory deadline of 11 March 2022.

Background to our market study

On 12 March 2021 we launched a market study into the supply of children’s social care placements in England, Scotland and Wales. We did this because of concerns about a shortage of appropriate places for looked-after children and high prices paid by local authorities. Just over 7 months on, we are now in a position to set out our interim findings and seek views from stakeholders.

Our decision to launch this market study was strongly influenced by the fact that looked-after children are among the most vulnerable people in our society, and the impact on them of poor outcomes in the placements market are potentially extremely far-reaching and life-changing. Our role, primarily, is to consider how social care placements operate as a market, for example by looking at overall levels of supply and the cost of these places, but we have remained acutely aware throughout that behind these issues are real and deep impacts on the lives of vulnerable young people throughout the country, and those who care for them. Risks that might be readily acceptable in other markets, such as a temporary mismatch between supply and demand, or the failure of certain providers, could have far more serious consequences in this market. We have taken an evidence-based approach, but in the full knowledge of the importance of getting the right outcomes for so many people, many of whom are young people who may have experienced trauma and neglect and whose future prospects are at stake.

Local authorities in England, Scotland and Wales have statutory duties in relation to the children taken into their care and are obliged to safeguard and promote their welfare, including through the provision of accommodation and care.

In discharging their duties, local authorities provide some care and accommodation themselves, and they purchase the remainder from independent providers, some of which are profit-making. Local authorities rely on independent provision more for residential placements than fostering placements, and more in England and Wales than in Scotland.

Children’s social care is a devolved policy responsibility, with key policy decisions being made by the Welsh, Scottish and UK governments. We recognise that the placements market is just one aspect of the wider children’s social care system and the economic considerations that we are focusing on are not the only relevant policy considerations. Our analysis, and any recommendations we make, will be based on the outcomes we see being produced by the placements market. It will, of course, be for the 3 governments and other stakeholders, taking into account wider policy goals and the context within their own nations, to decide how these should fit within their wider approach to the children’s social care system.

Concerns about the placements market

The quality and appropriateness of the placements which children receive is extremely important to their experience of care and future outcomes. Regulators assess most residential placements and fostering services as being of good quality, and where they are not there is pressure for this provision to improve or leave the market. We do not see significant differences in assessed quality between local authority and independent provision.

However, the concerns about a shortage of appropriate places and high prices appear to be supported by the evidence we have seen so far. Based on our initial consideration of the way the placements market is functioning, we have concerns that it is contributing to poor outcomes for children and local authorities in 2 ways.

First, it seems clear that the placements market overall is not providing sufficient appropriate places to ensure that children consistently receive placements that fully meet their needs, when and where they require them. This is resulting in some children being placed in accommodation that, for example, is too far from their home base, does not provide the therapy or facilities they need, or separates them from their siblings. Given the impact that poor placement matches have on the well-being of children, this is a significant concern.

Second, there is evidence that some prices and profits in the sector are above the levels we would expect in a well-functioning market. Our analysis of the largest fifteen independent providers indicates that they are earning significant and persistent economic profits. Our analysis so far only covers providers responsible for around a fifth of placements in children’s homes and slightly over half of fostering placements, so it is too early to give a definitive view on the overall levels of prices and profits in the sector. However, it does indicate that some providers are able to earn significant profits, paid for by local authorities, through the provision of children’s social care placements. If this market were functioning well, we would not expect to see under-supply and elevated prices and profits persisting over time. Instead, we would expect existing and new providers to create more places to meet the demand from local authorities, which would then drive down prices and profits. The fact that this does not appear to be happening suggests that there must be factors that are acting to deter new provision.

Identifying and addressing these factors should lead to a better functioning market, offering more places that better match the needs of looked-after children at reduced cost to local authorities. Our primary focus has been on doing this.

In any market, buyers and sellers must be able to interact effectively to generate positive outcomes. For buyers, they must be able to effectively signal their likely demand, now and in the future, and purchase the product or service that best fits their needs from those available. For sellers, they must be able to recognise and respond to buyers’ needs, adjusting the amount and type of the product or service they supply to meet these. Our view is that the placements market, as currently constituted, inhibits the effectiveness of both of these functions: local authority engagement in the market is not as effective as it could be and there are barriers to new supply being brought to the market.

Local authority engagement with the market

Local authorities face challenges procuring the best placements for their looked-after children. In some respects, their position is inherently weak as they must make sure a placement is provided for every child, often under considerable time pressure. This difficulty is made worse by the ongoing under-supply of appropriate placements, meaning that local authorities may end up paying a lot of money for places which are not ideal matches for the children they are placing.

One key strategy that local authorities can adopt to strengthen their position as buyers is to try to move away from purchasing each placement completely separately, instead linking them, for instance by using block contracts or procurement frameworks, or by seeking bulk purchasing discounts. However, the extent to which local authorities are able to employ these approaches effectively is limited by the small scale on which they are operating. Smaller numbers make it less attractive for providers to limit themselves in these ways.

Local authorities in some areas have tried to overcome these difficulties by cooperating with each other to form joint procurement approaches of various forms, including via national bodies in Scotland and Wales. To date, however, the success of these approaches in improving local authorities’ position in the market has been mixed; in England, for example, a large proportion of children’s home placements are currently spot-purchased.

On top of these concerns, it is widely recognised that the purchasing decisions made by local authorities today do not provide current and potential independent providers with good information about their future needs. Given the under-supply of appropriate places, places may still be filled even if they are not in the best location or provide the most suitable environment for the children placed in them. As a result, providers face weaker incentives to create new provision that is more appropriate to children’s needs.

This issue is made worse by the impact of timing; there is an immediate need to find appropriate placements for the children who need them. In the recent past, both the overall number of looked after children, and the needs of those children, has changed significantly. This is particularly important, because the creation of new placements (opening residential settings or recruiting foster carers) is both time-consuming and costly. As a result, when considering creating new provision, providers find it difficult to predict what the likely demand will be by the time those places are available to children.

Local authorities in England have a “sufficiency duty” to take steps to secure, so far as reasonably practicable, sufficient accommodation within each local authority’s area to meet the needs of the children it looks after. Local authorities in Scotland and Wales have similar duties. These duties ought to operate over time to ensure that local authorities are generally able to place children locally in a setting that is appropriate to their needs. However, the concerns we have around under-supply of appropriate places in the market suggest that this is not consistently happening. There is clear variation in the extent to which local authorities act to encourage sufficient provision to meet the future needs of children in their care, suggesting that spreading best practice, resource and expertise could lead to some benefits. However, our current view is that there are intrinsic limitations to the extent at which these functions can be effectively carried out at local authority level.

-

As a pre-requisite to doing this effectively, local authorities must be able to effectively forecast the number and type of placements they will need in the future. The numbers of children that local authorities will place in a given year are relatively small and variable, particularly for residential care. This problem is magnified when we look at children who have particularly complex needs requiring very intensive support, where the numbers per local authority are very small and the provision is expensive.

-

Once they have made forecasts, local authorities have to be able to meet any expected shortfall by creating placements themselves or encouraging such provision from the independent sector. For local authorities considering block contracts or other means of providing certainty of take-up to potential providers, there is a trade-off between their potential to create new places and the risk of paying for provision that is not needed by local children. In addition, for each local authority, the cost and management time of doing this market-shaping themselves can be significant in a context where the financial pressures on local authorities have increased significantly in recent years.

To address these persistent concerns about the inherent constraints that local authorities face in delivering effective forecasting, market shaping and procurement approaches, we are exploring potential recommendations around the need for larger-scale national or regional bodies with a remit to help ensure that children are able to access the right placements for them. There are a range of options to consider. At one end of the scale, these bodies could act as a support function for local authorities to carry out their own market-facing activities and collaborate with each other. At the other, the bodies could take on the responsibility for delivering placement sufficiency across their geographical remit, or even placing the children themselves, with associated budget. Similarly, local authority engagement with collaborative approaches run by these regional bodies could be voluntary or mandatory.

In examining these options, we recognise that effective engagement with the market is far from the only aim of the children’s social care system, and there may be concerns that moving away from a locally-focused service may harm the effectiveness of support offered for children and families. These concerns are best assessed by other policymakers, regulators and stakeholders. However, it is important that we understand these concerns as we shape our recommendations.

Barriers to new supply being brought to the market

Returning to the second issue that we are concerned is inhibiting the effectiveness of the placements market, we believe there are factors that are reducing the ability of suppliers to efficiently bring new supply to the market to meet emerging needs. These factors may be leading to provision being created more slowly, or even deterred completely, contributing to the overall undersupply of appropriate places.

One area we have considered is whether there are aspects of regulation which may be counterproductive. Regulation is a vital safeguard to protect the interests of children who are in an extremely vulnerable position. Clearly, appropriate regulatory standards must be maintained.

Our concern is not that regulatory standards are too high. Rather, it is that some aspects of the regulatory regime may be unwittingly creating barriers to providers and local authorities responding effectively to future needs without generating corresponding benefits for the children whose interests they are supposed to protect. The overall regulatory framework has been in place for more than twenty years, during which time the market has changed very significantly. The number of children requiring placements, and the complexity of the needs of those children, have increased significantly, as has the extent to which independent provision is playing a part in meeting those needs. It would therefore not be surprising if over this period some aspects of regulation have become outdated and inappropriate to the market as it currently exists.

To address this, we are considering potential recommendations around the reviewing of existing regulations that apply to providers of children’s social care placements. Any final decision on regulations however must be made by a body that has the appropriate expertise and must focus on the protection of children’s interests, which should be paramount. It should also, however, take a wider view of regulations, considering where they may negatively impact on the provision of placements. This will allow conclusions to be drawn on how regulation needs to be positioned to drive the best outcomes for looked-after children.

We also have concerns that a range of other barriers, including access to staff, recruitment and retention of foster carers, and property acquisition and planning processes may be restricting the ability of providers to provide more placements where they are needed. Policy approaches to the delivery of local children’s services and a lack of funds, or uncertainty about funding levels, may also be creating barriers to additional local authority provision. While these reflect broader concerns about labour supply across the economy and the availability of housing and local authority funding more generally, we are investigating whether there are particular aspects of the children’s social care system that make these issues especially problematic for the placements market.

Comparing types of provision: local authority and private

The considerations above have focused on how independent provision can be more effectively engaged in delivering the best outcomes for children and local authorities. We have also considered whether the involvement of certain types of provision, namely private (for-profit) provision and, within that group, private equity-owned providers, is itself a driver of poor outcomes.

First, considering quality, we have not at this stage seen any evidence of significant variations in quality between independent and local authority provision as evidenced by inspection outcomes. We have also seen that there is a significant impact on independent providers of receiving lower ratings. While both local authority and independent providers have told us that their provision is generally better, including in ways that are not consistently reflected in inspection ratings, those inspection ratings are the most comprehensive and comparable assessments of quality available, and the CMA is not in an appropriate position to second-guess them.

Second, we have considered the cost to local authorities of purchasing placements from private providers versus providing them in-house, using our dataset from large providers and local authorities. We have analysed the average operating costs of a number of private providers and compared these to costs of some local authorities’ own provision. We are aware that this does not give an accurate like-for-like comparison, mainly due to different average levels of need among the children placed in each type of provision. These outputs should not, therefore, be considered definitive, but are rather a basis for further consideration.

For children’s homes across England, Scotland and Wales, we have provisionally found that the prices charged to local authorities for private children’s homes placements are typically not higher than the cost of providing placements in-house. We note that these figures do not take into account the level of needs of the children and we understand the children placed in independent homes tend, on average, to have more complex needs. Larger independent providers are able to earn significant profits because their operating costs are lower than those of local authorities. This difference appears to be primarily driven by staffing costs, both higher numbers of staff per child and higher cost per staff member.

For fostering placements across England and Wales, by contrast, we found that the average price per child that local authorities pay for independent provision from the largest providers is higher than the cost of their in-house provision, reflecting both higher independent sector operating costs and the existence of a profit margin in the independent sector. As noted above, however, these figures do not take into account the level of needs of the children which we understand are generally higher in the independent sector. They also do not cover Scotland where for-profit provision of fostering agency services is unlawful.

These findings suggest that there are unlikely to be operational cost savings available to local authorities directly through a shift towards much more in-house provision of children’s homes. In fostering, on the other hand, this appears more of an open question. We will investigate the drivers of these average cost differences, and any implications these may have for our recommendations between now and our final report.

Turning now to private equity-owned provision, we have heard concerns that the involvement of private equity is driving up prices, driving down quality and decreasing resilience in the sector. In terms of prices and quality (as measured by inspection ratings) outcomes from private equity-owned provision do not appear any worse than those of independent provision in general.

In terms of resilience, we have seen evidence of particularly high and increasing levels of debt being carried by private equity-owned firms, which may leave them vulnerable to having to unexpectedly exit the market in the event of tightening credit conditions. We are less concerned about fostering agencies, as we would expect the foster carers to be able to transfer to another agency (independent or local authority) relatively easily. In the case of residential provision, however, transfer of homes to another provider could be especially disruptive for children. The homes could cease to operate as children’s homes altogether, with potentially serious negative impacts on children and the ability of local authorities to fulfil their statutory duties. Therefore, the risk of unexpected disorderly exit as the credit conditions faced by highly-leveraged companies change, is one that needs to be taken seriously. To address this, we are considering recommendations focused on measures that would reduce the risk of unexpected disorderly exit (such as a financial oversight regime with clear limits on leverage and financial risk-taking) and mitigate its effects (such as step-in provisions for alternative providers).

Finally, we consider the view that we have heard from some stakeholders that high prices and profits in the placements market should be addressed by directly restricting the prices or profits of private providers. Although at this stage we share concerns that prices and profits for the large providers we have analysed appear higher than we would expect in a well-functioning market, we believe that this is fundamentally a symptom of the underlying problem of insufficient supply of appropriate placements and the difficulties faced by local authorities in engaging effectively in this market.

Any moves to restrict prices and profits before we have addressed the supply problem would not address the supply problem and would be very difficult to apply where the needs of children (and the costs of meeting them) is so varied. While this could reduce the prices paid by local authorities for independent provision in the short term, this may be at the cost of further reducing the range of placements available for children and/or creating other cost pressures for local authorities as they had to make greater in-house provision to fill the gap.

Next steps

We welcome feedback on our analysis of market outcomes, emerging conclusions on potential drivers of poor outcomes and early stage thinking on possible recommendations. Informed feedback will be extremely valuable to us as we move into the second phase of our study, where we will look to deepen our analysis and sharpen our understanding of any drivers of poor outcomes and what can best be done to address them. In order to gain more structured feedback, we intend to hold a series of workshops with stakeholders to test our thinking and explore options.

Between now and the final report, which we will publish by 11 March 2022, we will develop further our thinking on the extent to which the placements market is delivering poor outcomes, the causes of these and the detail of any remedies required to address them.

1. Background

In the light of persistent concerns around high prices and an inadequate supply of appropriate placements for looked-after children, on 12 March 2021 we launched a market study into the supply of children’s social care services in England, Scotland and Wales, specifically considering residential services and associated care and support, and fostering services. The purpose of the market study is to examine how well the current system is working across England, Scotland and Wales, and to explore how it could be made to work better, to improve outcomes for some of the most vulnerable people in our society.

Our Invitation to Comment set out the scope of the market study and the key themes we intended to focus on, namely: the nature of supply, commissioning, the regulatory system and pressures on investment. On 20 May we published responses to the Invitation to Comment on our Children’s social care study case page.

Over the past few months we have gathered information from a wide range of sources to develop our understanding of these particular areas and the children’s social care sector more broadly, and to assess outcomes in the sector in terms of the availability of appropriate places, prices paid by local authorities and the resilience of the sector. We received 37 responses to our invitation to comment; we issued information requests to, and received responses from, the 15 largest providers of children’s homes and fostering services and received 27 responses to our questionnaire issued to smaller providers; we also received responses from 41 local authorities to our questionnaire. In addition, we have met with a range of stakeholders with an interest in the sector and we have visited a number of children’s homes.

This information includes data produced by the relevant regulators and national governments as well as that provided by large providers and local authorities in response to our questionnaires. However, we have found that the data available is generally not at a level of detail sufficient to be able to clearly answer some specific questions, such as whether there is sufficient supply of more specialised provision to meet a particular type of need in a particular location. As such, when we set out our provisional findings, we draw extensively on the experience and expertise of stakeholders in the sector to augment the available data.

On 9 September 2021 we published our decision not to make a market investigation reference. We are required to publish our final report on the market study by 11 March 2022. This interim report sets out our emerging thinking and we welcome submissions on the issues set out in this report by 12 November 2021. In addition to the information we have already gathered, those submissions will inform our findings and help shape our thinking on the nature of any remedies that may be appropriate, depending on those findings. We will seek to test our thinking with stakeholders, including via a series of workshops.

2. Overview of the sector

This section provides an overview of the children’s social care sector in England, Scotland and Wales and highlights some of the key differences in the policy, legislative and regulatory frameworks in each nation. It also considers how the sector has evolved over time.

Ensuring children live in safe, caring and supportive homes

All children need a safe, caring and supportive environment. The children’s social care system exists to ensure that all children have access to such an environment. For some children in England, Scotland and Wales, their family home is provided by foster carers and, for a smaller group, care is provided by children’s homes. In some circumstances, in England and Wales, children may be placed in unregulated accommodation: independent or semi-independent living facilities where they may receive support but not care.

Children may be looked after for a short period of time or there may be a longer-term arrangement, and children may be looked after in different care settings at different times in their lives. For these looked-after children – some of the most vulnerable people in our society - the state, through local authorities, is responsible for providing their accommodation, care and support.

It does this in 2 main ways: local authorities may use their own in-house foster carers, children’s homes and, in some circumstances, unregulated accommodation to provide accommodation, care and support – and tend to do so as their first choice where appropriate local authority placements are available – or they procure these services from independent (private and voluntary) providers.

The necessity of ensuring that children receive accommodation and care as the need arises places severe constraints on local authorities in how they must purchase placements. Time pressure can be immense as children may require placements urgently, often in response to a crisis. The requirements can vary considerably from case to case, due to the particular needs and circumstances of the child. The local authority must therefore seek the best option from among those placements that are available during a limited time period.

Children’s social care sector in England, Scotland and Wales

"

"

"

Notes: In the chart showing the proportion of children in care, the 57% of children in ’other settings’ in Scotland, represents a broader definition of care than is applied in England and Wales. In the pie chart showing foster placements in Scotland, the independent providers are wholly not-for-profit.

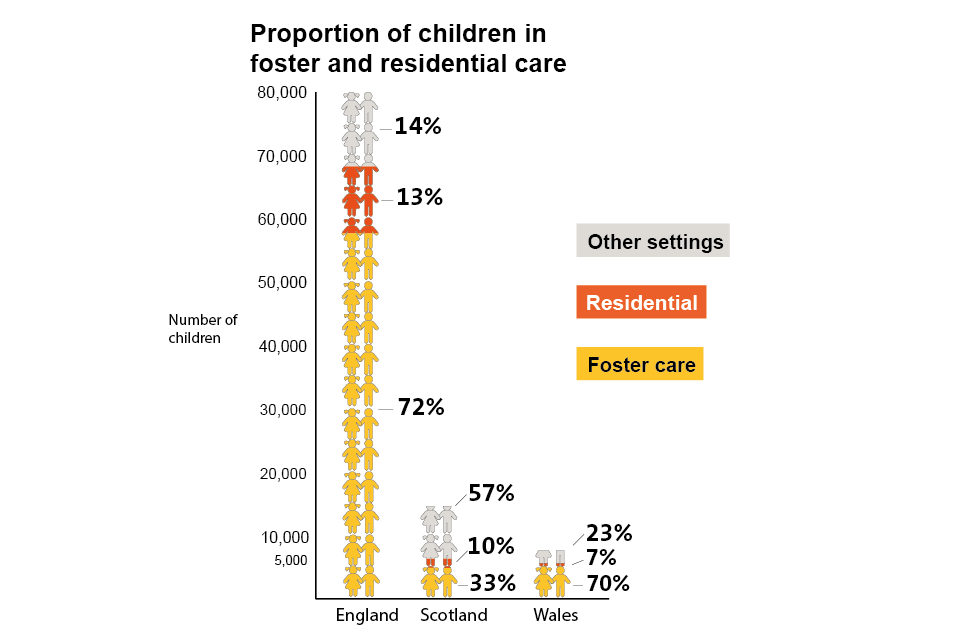

Looked-after children

There are currently just over 100,000 children in the care of a local authority (‘looked-after children’) in England, Scotland and Wales. Foster care is the most common form of care setting for looked-after children in each of these nations: over two-thirds of looked-after children in England and Wales live in foster care; around a third of looked-after children in Scotland live in foster care. 13% percent of looked-after children live in residential settings in England, 10% in Scotland and 7% in Wales. Such settings include children’s homes, secure children’s homes, independent or semi-independent living facilities and residential schools. The remainder of looked-after children live in a variety of settings, for example, living with parents, with kinship carers, placed for adoption or in other community settings.

Table 1: Children in care in fostering and residential settings in England, Scotland and Wales in 2020

| Numbers of looked after children | England | Scotland | Wales |

|---|---|---|---|

| In foster care | 57,380 (72%) | 4,744 (33%) | 4,990 (70%) |

| In residential settings | 10,790 (13%) | 1,436 (10%) | 535 (7%) |

| Other settings | 11,910 (15%) | 8,278 (57%) | 1,645 (23%) |

| Total | 80,080 | 14,458 | 7,170 |

Source: CMA analysis of data from various sources.

Notes: In Scotland 16,530 children were looked after or on the child protection register: 14,458 were looked after, 2,654 on the child protection register and 582 in both categories. In addition to the statistics in this table, in Scotland, 31% of looked after children were placed formally with kinship carers in 2020 and 25% were looked after at home.

Children may become looked after for a number of reasons including as a result of abuse or neglect, family dysfunction, parental illness or disability and absent parenting, as well as where they arrive in the UK as unaccompanied asylum seekers.

Local authorities

Local authorities have statutory duties in relation to the children taken into their care and are obliged to safeguard and promote their welfare, including through the provision of accommodation and care. Where it is in the child’s best interests, this should be provided locally in order to ensure continuity in their education, social relationships, health provision and (where possible and appropriate) contact with their family.

Specific statutory obligations on local authorities vary across England, Scotland and Wales, and we consider these further in Appendix B, including the “sufficiency duty” placed on local authorities in England, whereby local authorities are required to take steps to secure, so far as reasonably practicable, sufficient accommodation within the local authority’s area which meets the needs of the children it looks after.

Each local authority is responsible for providing, either themselves or by purchasing from another provider, the placements they require. There are 152 such local authorities in England, 32 in Scotland and 22 in Wales.

A 2020 survey found that a large proportion of placements (51%) are spot-purchased by local authorities. In such cases the terms for each placement are determined on an individual basis. The survey found that in 47% of cases, local authorities purchase placements using framework agreements, which set out the terms (such as the service offered and the price) under which the provider will supply the relevant service in the specified period. A much smaller number of placements (2%) are block contract placements.[footnote 1]

There are different approaches to commissioning and purchasing in each nation:

-

There is no national commissioning body in England. The National Contracts Steering Group (NCSG) – comprising the Local Government Association (LGA), a group of local authority commissioners, independent providers and trade associations – was established over a decade ago, supported by the Commissioning Support Programme. It developed 3 national contracts for placements in schools, foster care and children’s homes. However, the work of the NCSG ended when the Commissioning Support Programme came to an end, as discussed further in Section 4. Currently in England, some local authorities procure individually, while many form regional procurement groups with neighbouring local authorities. These groups vary in their design and purpose.

-

Scotland Excel is a public sector organisation operating on behalf of Scotland’s 32 local authorities. It undertakes strategic commissioning of services and provides a wide range of national contracts for local authorities in Scotland, including contracts for the provision of fostering services and children’s residential care. It is up to individual local authorities whether they secure placements through Scotland Excel, and not all local authorities do so for every placement they require to make.

-

In Wales, all 22 local authorities are members of the Children’s Commissioning Consortium Cymru (4Cs). Since 2018 the Framework Agreements for both residential and foster care have been reviewed – the All Wales Residential Framework was launched in 2019 and the All Wales Foster Framework launched in April 2021.[footnote 2]

Role of the market and nature of provision

In addition to local authorities making placements through their own in-house provision (where that is available), the market plays a significant role in the allocation of care placements that can be purchased by local authorities from private and voluntary providers.

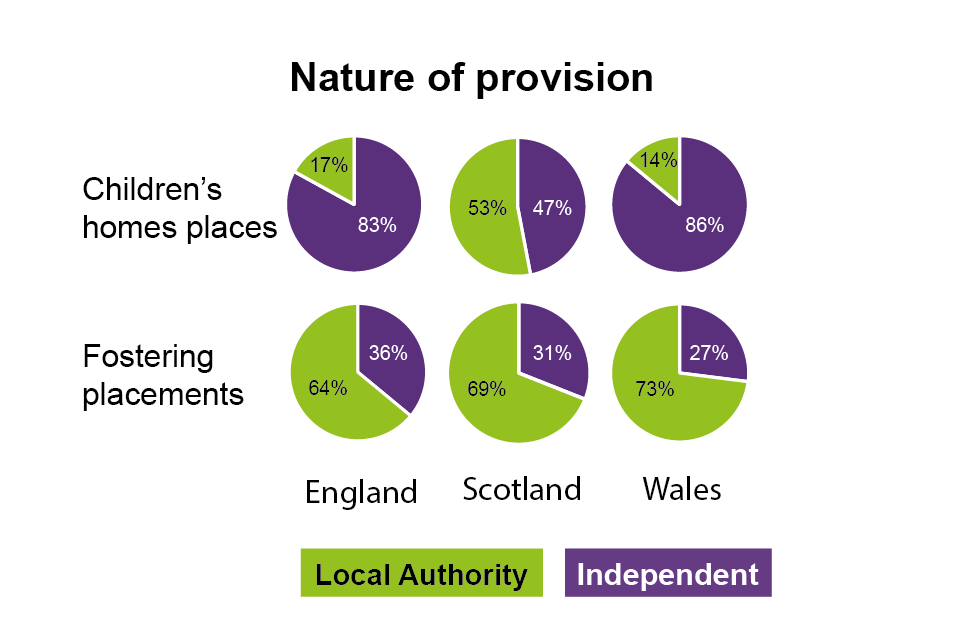

Table 2 below shows that in England and Wales, the largest proportion of children’s home places are provided by the private sector – around 78% and 77% respectively. In contrast, in Scotland only around 35% of places are provided by the private sector.

Table 2: Number of children’s home places by provider type and nation

| Provider type | England | Scotland | Wales |

|---|---|---|---|

| Private provision | 7555 | 362 | 769 |

| Voluntary provision | 501 | 130 | 89 |

| Local authority provision | 1643 | 556 | 144 |

Source:

- England - Main findings: children’s social care in England 2021

- Scotland - Children’s social work statistics: 2019 to 2020

- Wales - Invitation to comment response: Care Inspectorate Wales

The majority of fostering placements are provided by local authority foster carers – 64% in England, 69% in Scotland and 73% in Wales, as illustrated by table 3 below. However, a significant minority are provided by private providers (except in Scotland where for-profit provision is not permitted) and voluntary providers.

Table 3: Number of children in foster care by provider type and nation (2020)

| Provider type | England (2019 to 2020) | Scotland (31st Dec 2019) | Wales (31st Mar 2020) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent provision | 19,395 | 1,514 | 1,355 |

| Local authority provision | 34,190 | 3,396 | 3,635 |

Note: “Independent provision” refers to care which is not provided by local authorities. Except in Scotland, it includes both for-profit and not-for-profit provision. For-profit provision of fostering services is not permitted in Scotland.

Source:

- England - Ofsted: Official Statistics Release, published 12 November 2020

- Scotland - Care Inspectorate: Fostering and adoption 2019-20 A statistical bulletin

- Wales - Children looked after in foster placements at 31 March by local authority and placement type

Policy context

Children’s social care is a devolved policy area. The current annual cost for children’s services in England is around £4.5 billion. In Scotland, the current annual cost is around £650 million. In Wales, the current annual cost is around £320 million.

All 3 governments are engaged in significant policy processes to consider wide issues relating to children’s social care.

-

In England, the Independent review of children’s social care published its case for change in June 2021. The Review is aiming to publish its final recommendations by Spring 2022.

-

In Scotland, the findings of The Promise – Independent care review are being taken forward by The Promise Scotland. This year it published its Change Programme ONE and Plan 21-24. The Scottish Government has launched a consultation on a National Care Service (NCS) in Scotland, following on from the Feeley review of adult social care. Amongst other questions, the Scottish Government is seeking views on whether the NCS should include both adults and children’s social work and care services.

-

In Wales, commitments around protecting, re-building and developing services for vulnerable people were made in the Programme for government 2021 to 2026.

Both the Scottish Government and Welsh Government have expressed an intention to remove profit-making from the provision of care to looked-after children, as is already the case for fostering agencies in Scotland.

Each nation has its own statutory framework, regulations and guidance applicable to the children’s social care sector and where relevant, we draw out key differences in this interim report.

Regulatory environment

Children’s social care provision is highly regulated. England, Scotland and Wales have their own regulators – Ofsted,[footnote 3] the Care Inspectorate Scotland (CIS)[footnote 4] and the Care Inspectorate Wales (CIW)[footnote 5], respectively. The regulators register and inspect children’s social care establishments. Again, we draw out key differences in approach where relevant in this interim report.

Unregulated and unregistered accommodation

In England, an establishment is a children’s home if it provides care and accommodation wholly or mainly for children.[footnote 6] Unregulated accommodation is where accommodation is provided, but not care. Independent living (with or without support) and semi-independent living, fall into this category of accommodation. Unregulated accommodation should not be confused with unregistered accommodation (which is where care is provided, but the provider is not registered; this is illegal). Placing children under the age of 16 in unregulated accommodation in England became illegal from 9 September 2021.[footnote 7] In Wales, some accommodation is not regulated or inspected by the CIW.[footnote 8] Unregulated accommodation for children is not permitted in Scotland.

Market oversight

Unlike for adult social care, in England there is no statutory market oversight scheme for the children’s social care sector. In Wales there are statutory market oversight provisions,[footnote 9] but these have not yet been commenced. However, the Welsh Government intends to develop a non-statutory market oversight framework. There is no formal market oversight regime in Scotland. Appendix B provides more information on market oversight.

Evolution of the children’s social care sector

The number of children entering children’s social care has increased over time, and the needs of those children have grown more complex. A number of parties told us that the level of individual need is both growing and evolving.[footnote 10] There are also increasing numbers of older children being looked after.[footnote 11]

There has been a trend towards smaller children’s homes, as demand for smaller and solo provision has increased over time.[footnote 12] In 2020, the average new children’s home in England had 3.5 places.[footnote 13]

The Institute for Government projected in its 2019 Performance Tracker that demand for children’s social care placements would grow by 7 to 10% between 2018 to 2019 and 2023 to 2024.[footnote 14] More recently, the Social Market Foundation projected that, in England, “based on the growth seen in the last 5 years, we could expect that close to 77,000 children will be in foster care by 2030; an increase of more than 30% from now.” However, as discussed later in this report, we note that while demand for children’s social care services is widely expected to grow, there are ongoing efforts to reduce the number of looked-after children, and several other factors that make it difficult to predict the level and profile of future demand with a high degree of certainty.

There has been an increase in private provision over time, with many voluntary providers leaving the sector (although there has been an increase in the number of voluntary children’s homes in Scotland over this time). We heard that, in England and Wales, some local authorities have come back to providing some of their own residential care or are actively considering doing so. The Fostering Network,[footnote 15] which operates across the UK, noted that it had seen a considerable rise in the number of independent foster providers in its membership over the years, reflecting the expansion of the independent fostering sector in that time.

Structure of the rest of the interim report

In the rest of this interim report we:

-

Set out our view on the outcomes we would expect a well-functioning placements market to deliver, then set out our emerging findings on how closely outcomes in the children’s social care sector seem to approach this, assessing the evidence on the supply of appropriate places, prices and profits, and the resilience of the sector. (Section 3)

-

Examine the possible drivers of those outcomes. (Section 4)

-

Set out our provisional view on issues that need to be addressed and potential remedies. (Section 5)

-

Ask a number of questions in relation to our emerging findings and potential measures and invite evidenced submissions in response to these questions and our emerging findings more generally. (Section 6)

3. Emerging findings – outcomes from the placements market

Outcomes that we would expect a well-functioning placements market to deliver

Children’s social care must aim to secure the right outcomes for children who rely on it. While the determinants of these outcomes go beyond the functioning of the market for placements, that market should contribute to, and certainly not detract from, the ability of the system as a whole to deliver these outcomes.

We have picked out 4 key outcomes that a well-functioning market for placements would support:

-

First, the supply of placements must be sufficient so that places are available for children that need them, as they need them. These placements must be appropriate to the needs of the child and in the appropriate location.

-

Second, placements must be of sufficiently high quality, tailored to the specific, individual needs of each child.

-

Third, placements must be available at a reasonable price, taking into account the costs involved and the quality of the placements.

-

Fourth, the market should have sufficient resilience that it allows us to have confidence that the 3 outcomes above will continue to be met into the future.

In the remainder of this section we consider each of these required outcomes in turn and give our emerging view on the extent to which the functioning of the placements market is contributing to them.

Supply of appropriate places

The evidence we have seen so far raises clear concerns that the placements market is not providing sufficient appropriate places to ensure that children consistently receive placements that fully meet their needs, when and where they require them. This is resulting in some children being placed in accommodation that, for example, is too far from their home base, does not provide the therapy or facilities they need, or separates them from their siblings. Given the impact that poor placement matches have on the well-being of children, this is a significant concern. Local authorities go to great lengths to ensure that all their looked-after children have a placement when they need it. The alternative to this – children not getting access to any placement – would be an unacceptable outcome, and it is crucial that this never happens.

Overall, there are more approved places than children deemed to be in need of placements. For example, in England at 31 March 2020 there were 89,200 approved fostering places and only 64% were filled (excluding those where data was not available).[footnote 16] Similarly, the 700 children’s homes owned by larger providers that we collected data on had an average occupancy rate of 83%.

Simply having a number of approved places that is higher than the number of children requiring placements, however, does not mean that there are sufficient appropriate placements for children. First, the overall number of approved places is an overstatement of the number of places that are available at any one time:

-

At March 2020 in England, 20% of approved fostering places were ‘not available’ (excluding those where data was not available).[footnote 17] Approved foster places may not be available for a wide number of reasons including where foster carers are taking a break or are not able to take their maximum approved number of children, for example where this maximum is dependent on the children being siblings.

-

Similarly, approved places in children’s homes are sometimes not available, for example, where a current resident’s needs mean it is not appropriate to place other children alongside them. The extent to which this is the case will fluctuate over time, and there is no consolidated data on the aggregate position.

Second, where a place is available, it may not meet the specific needs of individual children who require placements at that time. While comprehensive data about the appropriateness of placement matches for particular children’s needs is not available, we have seen evidence indicating that some children are not gaining access to appropriate placements due to a lack of supply. This may be because of a number of factors, including:

-

Type of placement: local authorities have consistently told us that they may assess that one type of placement would be most appropriate for a child, but have to place them in a different type of placement due to lack of availability of the preferred option. For instance, this can result in children for whom foster care would be most appropriate being placed in a children’s home. As well as being a poor outcome for the child, this is more expensive for the local authority.

-

Location: As of March 2020, in England 44% of children in residential placements[footnote 18] and 17% of children in fostering placements were over 20 miles away from where the child would call home (excluding those where distance is not known).[footnote 19] As at March 2018, in England more than 2,000 looked-after children were over a hundred miles from home.[footnote 20] Stakeholders report concerns about children being placed across national borders, particularly placements from England into Scotland where children may be very far from home and in a different legal and educational system. While there can be legitimate reasons why it would be in a child’s best interests to be placed out of area (for example, to separate them from negative influences), we have been told that it is lack of suitable places available within a reasonable distance that is driving the out-of-area placement of children in many cases. Children moved away from their home area may suffer loneliness and isolation at being separated from their support networks, have their schooling disrupted and may experience difficulty in accessing social services.

-

Siblings: Local authorities also report difficulties in placing sibling groups together, particularly larger groups. Ofsted figures show that for fostering in England in 2019 to 2020, 1400 siblings were not placed according to their plan.[footnote 21] This represented 13% of all siblings in care. In Scotland, at 31 December 2019, there were 200 sibling groups separated upon placement in foster care, just over one in 5 of all sibling groups in foster care.[footnote 22]

-

Type of care needs: We also heard from local authorities that it is especially difficult to find placements for children with more complex needs. Given the particularity of the needs involved, it is very difficult to quantify the extent to which this is happening in aggregate. However, high levels of placement breakdown may be due, in part, to difficulties with finding placements that are appropriate to the needs of individual children; for example, in England, one in nine children looked after at 31 March 2020 had had 3 or more placements in the preceding year.[footnote 23]

One particularly concerning indicator of a lack of supply of appropriate placements is the extent to which children appear to have been placed in unregulated accommodation, not as a positive choice but due to the lack of availability of a suitable regulated placement.[footnote 24] For example, between April 2018 and March 2019 there were 660 looked-after children under the age of 16 placed in unregulated accommodation.[footnote 25] In response to these concerns, the Department for Education has recently banned the placement of under-16s in unregulated accommodation and committed to introducing national minimum standards for these settings. Although this should improve the situation by ensuring that one important category of children who were being inappropriately placed in unregulated accommodation are no longer placed there (under-16s), it will not in itself address the supply constraints in the regulated sector that drove local authorities to place them there to begin with and may indeed make them worse.

Taken together, this evidence suggests that the market is providing insufficient places to ensure that local authorities can consistently get access to placements for children that meet their needs. This conclusion is supported by the fact that local authorities, particularly those in England, told us that when they are seeking to place children they often have little or no choice of placement, for example finding at most one available placement that fits their basic criteria, which means that factors such as quality, fit, cost and location are less likely to determine placement decisions.

It is important to note that, while this pattern reflects what we are seeing in aggregate, there are important variations, both geographically and within the whole cohort of looked-after children.

In England, concerns about lack of appropriate supply were widespread. For example, Ofsted told us that it does not believe local authorities are able to meet their sufficiency duties as indicated by, among other things, the use of unregistered provision, the number of children waiting for secure places, and the lack of appropriate provision for children with complex needs. Some regions have far more places than others, for example the North West has 23% of all places in children’s homes and 19% of looked-after children, while London has just 6% of places in children’s homes and 12% of looked-after children.[footnote 26] However, this does not necessarily translate into sufficient availability of appropriate places for children in areas of “oversupply”, such as the North West, due to children from outside the area being placed there. Also, analysis done by Ofsted in 2018 found that there was wide regional variation in how far children’s homes were located from where children originally lived. Children placed from local authorities in the South West and London had to travel 54 and 60 miles respectively, compared to an average of 36 miles for England as a whole and 21 miles for children from the North West.[footnote 27]

In Wales, the situation appears to be similar. Stakeholders in Wales also report sufficiency problems particularly in fostering and to meet more complex needs. CIW told us that “most local authorities are struggling to meet their sufficiency duties and find suitable placements to meet the needs of children and young people. This adversely affects placement choice, permanency and stability and consequently outcomes for children.”[footnote 28] A lack of available fostering places has led local authorities to seek other residential care instead even if this is not as conducive to meeting needs. For residential care, the problem was considered to be not overall capacity but where that care is and having sufficient provision to meet the highest levels of need. As at March 31 2020, Welsh local authorities had placed over 1300 children in other local authority areas in Wales and almost 200 children outside of Wales.[footnote 29] Unregulated care is used when local authorities could not find regulated provision with timescales put in place to get the service registered.

In Scotland, by contrast, stakeholders expressed more limited concerns about the supply of placements. As in parts of England and Wales, however, we were told that there were difficulties finding appropriate care placements. We were told there is a general shortage of foster carers and particularly so for children with more complex needs, such as complex disabilities or older children with risk factors, and for family groups. Fewer concerns were raised around the overall capacity of residential care, but shortages were reported for residential care for children with disabilities and for children with mental health issues.

Moving to variations within the cohort of looked-after children, we received widespread feedback from local authorities that certain factors made it harder for them to find appropriate placements for children from the supply available in the placements market. These included:

- Care needs: children with more complex needs are harder to place.

- Age: for a given level of care need, older children are typically harder to place. This factor also plays into the difficulty of placing unaccompanied asylum seeking children.

- Siblings: as noted above, local authorities can have difficulties placing sibling groups together.

In sum, there is wide-spread agreement from stakeholders, supported by the available data, that the market is currently failing to provide sufficient supply of the right kind to ensure that local authorities can consistently place children in appropriate placements to meet their needs. Within this picture, there are particular shortages of supply in relation to particular geographic regions and types of need.

Quality of provision

The quality of accommodation and care that children receive is of paramount importance to their life experiences. However, as with other social services, pressures to reduce costs can adversely affect quality. As a result of this, and the serious consequences of poor care provision for children, regulation is rightly used to ensure that required standards are being met. This is the most important role that regulation plays and we recognise that others conducting work on children’s social care, including the Independent Care Review in England, The Promise implementation team in Scotland and officials serving the Welsh Government, are better placed to comment on the approaches to considering quality and the standards set by regulators and legislation.

Choosing a placement that best meets a child’s need is an essential part of the local authority’s role. However, assessing the quality of care is difficult for reasons including: the personalised nature of children’s needs; the large number and small scale of residential and foster homes; the importance of matching children to the right type of care; that children may be vulnerable and not able to articulate their views; and the long-term nature of desired outcomes. This is part of the challenge for regulators in this sector and we have heard concerns about consistency and occasions where stakeholders do not consider that ratings reflect quality.

Despite these challenges, inspection outcomes are generally seen as an important measure of quality and used by local authorities when deciding where to place children. Findings by the regulators suggest that the quality of care in most cases is high. In England at 31 March 2021, 81% of children’s homes and 93% of fostering agencies were rated as good or outstanding.[footnote 30] In Scotland, in January 2021 CIS reported that “overall, the quality of fostering services was high”[footnote 31] and it “evaluates most care homes for children and young people in Scotland as being good or very good.”[footnote 32] In Wales the CIW, in a recent thematic review of care homes for children, found “most children were receiving good quality care and support”.[footnote 33] However, this still means that regulators consistently find that some provision does not meet the required quality standards and this shortcoming, of course, must be addressed.

Stakeholders consistently told us that there is a significant impact on independent providers of receiving lower ratings. At the extreme, regulators will close children’s homes that do not meet the minimum required standards. Further, providers explained there were multiple other potential impacts on their business of having poor ratings, including “requires improvement to be good” ratings in England, which is above the minimum standard. One provider told us that “local authorities regularly take the position that they will not refer/place young persons into a service rated Inadequate or Requires Improvement” and “a number of local authority frameworks will also not allow services to be included” if they have received one of these ratings. Another provider highlighted the impact on their ability to recruit foster carers, because local authorities would generally use agencies rated Good or Outstanding instead, and staff, including that “some social workers did not want to be associated with a [requires improvement] rating.” Providers consistently told us that they proactively seek to maintain high quality standards and would always work to improve poor ratings.

Local authorities placing children rely on a wider range of quality measures than inspection ratings, including: visits to homes by social workers and independent visitors, such as the monthly visits by an independent person in England[footnote 34] and by independent advocacy groups; and experience of past outcomes for other children. The nature of these measures means that we are not able to consider these systematically and, as noted above, others are better placed to do so.

The situation is different for unregulated accommodation, which is not currently subject to inspection. Individual local authorities make their own assessments of whether unregulated accommodation places are appropriate for the young person they are placing there, and we have heard concerns around high levels of variability in quality, with some instances of very poor quality. Without an external judgement of quality, it will be more difficult for local authorities’ activities in the placement market to encourage providers to improve quality. The Department for Education has announced that it will introduce national minimum standards for unregulated settings in England; while the detail on how these will be implemented is yet to be confirmed, this could improve the ability of local authorities to drive up quality via the placements market.

Our provisional view is that the inspection regimes in place for children’s homes and fostering agencies, along with their own observations, provide local authorities with an evidence base on which to make judgements on the quality of care provided. These judgements exert a strong influence on their placement purchasing decisions, meaning that there are incentives on suppliers to rapidly improve provision or exit the market. While we are aware of arguments that the standards required by regulators ought to be higher, or inspections ought to be more frequent, these questions do not directly relate to the functioning of the placements market, and are best considered by policymakers, regulators and their independent advisers.

Prices and profits

Based on what we have seen so far, there is evidence that some prices and profits in the sector are above the levels we would expect in a well-functioning market. We have analysed data from the 15 largest private providers of children’s social care across all 3 nations covering the period since financial year (FY) 2016. Our analysis so far only covers providers responsible for around a fifth of placements in children’s homes and slightly over half of fostering placements, so it is too early to give a definitive view on the overall levels of prices and profits in the sector. However, it does indicate that some providers are able to earn significant profits, paid for by local authorities, through the provision of children’s social care placements. If this market were functioning well, we would not expect to see under-supply and elevated prices and profits persisting over time. Instead, we would expect existing and new providers to create more places to meet the demand from local authorities, which would then drive down prices and profits. The fact that this does not appear to be happening suggests that there must be factors that are acting to deter new provision.

In this section we provide an overview of our initial findings. Appendix A, published alongside this report, provides more data on our methodology and on these initial findings.

Splitting our data by type of placement provided across the 15 providers, we found that:

- For children’s homes, prices increased steadily across the period, from an average weekly price of £2,977 in 2016 to £3,830 in 2020, an average annual increase of 5.2% compared to average annual price inflation of 1.7% over that period.

- For fostering placements, prices remained broadly the same over the same period, at an average of £820 per week.

- For unregulated provision the underlying trend is affected by some of the large providers in our sample entering this segment around 2018, but since that point the average price has also remained broadly unchanged at £948 per week.

Changes in prices alone, however, do not in themselves provide an indication of how well or poorly the market is functioning. Price changes can also be due to changes in costs and many providers pointed to cost drivers such as rising National Minimum and Living Wage rates, as well as increasing average levels of need among children entering care. It is therefore important to consider whether cost factors can account for any observed increase in prices.

In order to account for cost factors for private providers, we have considered the operating profit for our set of the 15 largest providers, over the same period. Operating profit indicates a provider’s profitability after deducting its operating (day-to-day running) costs. We obtained operating profitability by subtracting total operating costs from total revenue.[footnote 35] From this we have calculated the average operating profit per placement and the operating profit margin (operating profit as a percentage of revenue).

Applying this to the 3 broad categories of placement (ie children’s homes, fostering agencies and unregulated accommodation), we have found that:

- For children’s homes, average operating costs have increased over the 5 year period from 2016 to 2020 in line with increasing prices, resulting in operating profit margins remaining broadly flat, at an average of 22.6%. Average operating profit has increased over the period from £702 to £910 per placement per week.

- For fostering agencies, operating costs have remained flat over the 5 year period, as have prices, resulting in a steady operating profit margin at an average of 19.4%. Average operating profits have also remained broadly flat over the period at £159 per placement per week.

- For unregulated accommodation, prices remained broadly flat in the period from 2018, but operating costs increased resulting in an operating profit margin that decreased from 39.9% to 35.5%. Average operating profit per placement per week decreased from £381 in 2018 to £330 in 2020.

In addition to operating costs, however, we must also consider the cost of capital for the business. The cost of capital represents the return that equity and debt investors require to invest in a business.[footnote 36] Deducting the cost of capital from operating profits provides us with a figure for economic profit. Economic profitability indicates a provider’s profitability after meeting its operating costs, its capital expenditure and providing a return to its investors. Significant and persistent economic profit is often an indication that a market may not be working well.

Unlike the figures for prices/revenues and operating costs, which can be calculated directly from a firm’s accounts, its cost of capital needs to be estimated. The cost of capital will differ between and within different sectors depending on factors such as risk and rates of return available elsewhere.

We have made preliminary estimates of the return on capital employed (without deducting a cost of capital) for the 13 large providers operating in residential accommodation (children’s homes and unregulated accommodation), as an indicator of the level of profitability of these providers:

- 11.1% for children’s homes for the period from 2016 to 2020; and

- 16.2% for unregulated accommodation for the period from 2018 to 2020.

For our analysis to find that economic profits were not being made in this sector, we would need to believe that the true weighted average cost of capital was at approximately this level. We have not at this stage taken a view on what we think the true cost of capital is for firms in this sector. Given our experience in other sectors, however, at this stage we consider it unlikely that this level is as high as our estimate of the return on capital employed among this set of providers.

As operating a fostering agency is an asset-light business, approaches that look at return on capital employed are less helpful in determining the level of economic profits being made. Instead, we intend to compare margins in fostering agency services to appropriate comparator companies and also use an alternative analysis that estimates the market value of assets and applies a rate of return to these. While we have not yet completed this analysis, at this stage we consider that the average profit margin of 19.4%, which we found in our sample of the largest providers, appears high for a business with relatively few capital assets.

Our provisional view is that, among the 15 large providers in our dataset, there is evidence that profits in the provision of children’s social care are higher than we would expect in a well-functioning market. Between now and our final report, we intend to do further work to test that conclusion, including:

- Consider further the cost of capital that is appropriate in children’s social care;

- Carry out financial analysis to examine prices and profits beyond the fifteen largest providers;

- Examine profitability drivers such as sub-categories of provision, geographical basis, or other factors.

We welcome views on our proposed approach to profitability assessment and on the appropriate cost of capital (ie the level of return that an investor would expect) in children’s social care which we use to assess the levels of profitability, which are described in more detail in the financial analysis appendix.

Resilience of the market

For the children’s social care market to work well, local authorities must have confidence that it will offer them good options in the future to meet their statutory obligations towards the young people in their care. We have concerns that risks may arise in this regard.

The main source of these risks arises from the fact that local authorities have an obligation to provide suitable placements for children, but are, to varying extents, reliant on placements from private providers to fulfil this obligation. For a variety of reasons, private providers may exit the market at any time. This creates a potential risk that certain external events may lead to unforeseen and significant market exit, significantly increasing the difficulties local authorities face in finding placements for young people in their care.

To some degree, this will be an issue in any market where significant provision comes from the private sector. In assessing whether we should have particular concerns in relation to children’s social care, we therefore need to consider whether the consequences of unforeseen and significant market exit would be particularly damaging, and whether the likelihood of this happening is particularly high.

We do have concerns that an unforeseen disruption in the supply of placements could have a particularly negative impact.

First, the impact of a local authority being unable to find an appropriate placement for a child can be extremely significant in terms of the outcome on that child’s life and experiences. While in many markets if there is an interruption in supply due to market disruption a buyer can simply delay or forego a purchase, in children’s social care this is not an option as there are real and urgent needs to be met.

Second, given our concerns about the availability of adequate supply of appropriate placements, a sudden reduction in supply caused by market disruption would exacerbate these issues. Any sudden and significant reduction in supply would be likely to impact on local authorities’ ability to provide appropriate placements for children in their care as they need them, as they are not facing a market with significant additional supply that is appropriate to absorb such a shock. The consequences of such an event occurring would also be severe for the children affected - potentially disrupting their education, social contacts and therapeutic progress, and seriously damaging their life prospects.

Third, we have heard that the creation of new provision takes a significant length of time, in terms of securing property and/or carers, and meeting regulatory requirements. This would suggest that even where there are suppliers looking to enter or expand to replace lost capacity, this would be unlikely to address any shortfall in placement in the short term.

The level of potential negative effects on local authorities and children in the event of a provider failure will depend on both the scale and nature of the provider and what happens to the business. The failure of a larger provider would generally be likely to have a more significant impact than that of a smaller one, as it would raise the risk of more children needing a new home at once; this would be likely to prove challenging in a supply-constrained market. Similarly, if one or more local authorities is highly dependent on a provider that fails, this could cause particular problems for them.

The impact of any firm failure will depend on what happens to the placements that firm had been providing. If provision was able to continue smoothly without disruption to the lives of children, this would be much less concerning than if the provision were to cease operation, creating upheaval for children.

This is less likely to be concerning in the case of a fostering agency provider, as the foster carers themselves would not necessarily cease to provide foster care simply because their agency withdrew from the market. Unlike with children’s homes, the main pieces of physical capital – the actual homes children live in – are not owned by the provider, but are provided by the foster carers themselves. The main issue would be transferring the foster carers to another agency; if carried out smoothly, this should not directly affect the experience of children. We will investigate further if there would be administrative difficulties with this, or if loss of foster carers would be a likely outcome as this process played out.

Firm failure is potentially more concerning in the case of residential children’s homes and unregulated accommodation. In theory, where these properties, staff and other company assets are fundamentally profitably employed as placements for looked-after children, they could be sold to another owner who wishes to use them in this way (either en masse as a trade sale or to multiple buyers); theoretically, this could result in a relatively seamless transition for local authorities and children through the change of ownership.

However, this may not play out as smoothly as the theory may suggest. Given the nature of the children’s social care market, there may be a small pool of potential buyers in this sector, especially if external events are putting pressure on multiple providers at the same time. Changes in rental values and costs may make it less attractive for a new purchaser to continue to operate children’s homes. Additionally, the process of restructuring could be protracted and disruptive, reducing focus on outcomes for children.

Turning to factors that may make sudden supply disruption more likely in this sector, we have heard concerns that high levels of debt held by firms may leave them particularly vulnerable to changes in external conditions, such as a sudden tightening of credit conditions, which could result in them being unable to service their debt burden and therefore being forced to leave the market. Some stakeholders made comparisons to Southern Cross, a former provider of care homes for older people, which got into severe financial difficulties in 2011. These concerns have been raised especially in relation to private equity (PE) owned providers; we provide an update on our findings so far about relative debt levels of PE-owned providers in the following section.

All else being equal we would expect high levels of debt to leave providers more vulnerable to tightening credit conditions, and therefore more at risk of unanticipated exit from the market. This analysis, however, does not take into account the wider financial position of the upstream owners of the provider, which may have greater or lesser access to capital to support the business through temporary difficulty. It is therefore not possible to use operating company debt levels alone as a conclusive indicator of the vulnerability of a provider to external shocks.

Taking all of these considerations together, however, the underlying risk of unexpected disorderly exit – which we have seen with highly-leveraged companies in other sectors – is one that needs to be taken seriously in this sector due to the consequences that could result. These could include significant negative impacts on individual children and the ability of local authorities to carry out their statutory duties, at least in the short term.

Types of provision

Concerns have been put to us about the participation of private providers in children’s social care provision and the Scottish Government and Welsh Government have expressed an ambition to end reliance on private provision. Some stakeholders are particularly concerned about the role of PE-owned providers in the placements market. We have therefore looked at the outcomes from:

- Independent provision versus local authority in-house provision; and,

- Within independent provision, PE-owned versus non-PE-owned providers.

Independent and local authority provision

We found that independent provision can often play a very different role to local authority in-house provision and as a result, comparisons between outcomes are challenging, with neither type of provision at this stage appearing clearly to deliver better outcomes across the board.

First, we have consistently heard that independent providers tend to look after children with more complex needs compared to in-house services. This is the case across nations and in both fostering and children’s homes, although we recognise that there will be exceptions where local authority provision takes on more complex needs and where independent providers take on less complex needs.[footnote 37] One exception we heard to this general trend is where local authorities cannot find a suitable independent provider for a child with particularly complex needs and so local authorities have to provide care for that child in-house.

Second, we have heard from local authorities and other stakeholders that local authorities attempt to use their in-house provision first, using independent providers only if no suitable in-house place is available. We have been told that this is because they want to use the capacity that they understand better and over which they have greater control, and for which they are already paying the fixed costs.

Turning first to comparisons of quality, we have not seen evidence of systematic differences in outcomes between local authority and independent provision. In England, the regulatory ratings for children’s homes run by private providers and local authorities are broadly in line with each other; local authorities have a greater proportion of outstanding children’s homes (22% vs 15%), but they also have a slightly higher proportion of inadequate homes (3% vs 1%). It is not possible to compare ratings in this way for fostering as local authorities’ fostering services are rated as part of their overall children’s services rather than for their fostering services alone. In Scotland the proportion of children’s homes graded good or better is higher for privately owned homes compared to local authority run homes (81.5% vs. 75.5%).[footnote 38] (In Wales, it is not possible to compare ratings in this way as provision is rated as either compliant or non-compliant).

Despite this, many local authorities and private providers told us that their type of provision was of better quality than the other. Given the relative performance reflected in inspection ratings, for there to be any systematic difference in quality between the 2 types of provision, there would need to be differences in quality that are systematically missed in inspection ratings. The CMA is not well-placed to assess whether this is the case and we have not seen convincing evidence that it is. As it stands, inspection ratings are the most comprehensive and comparable assessments of quality available, and there is no reason to believe that the CMA could get a more accurate picture by second-guessing them.