Shaping future support: the health and disability green paper

Updated 15 March 2023

Foreword

My priority as Minister for Disabled People is to make sure that disabled people and people with health conditions can lead the most independent lives possible and reach their full potential. As this Government’s 2019 manifesto set out, we must empower and support disabled people and be an ally. The benefits system is one important lever we have to achieve this.

Shaping Future Support: The Health and Disability Green Paper asks for your views on how the Government can help people to live more independently, including support to start, stay and succeed in work and ways we can improve the experience people have of the benefits system.

The experiences of disabled people and people with health conditions have shaped the ideas, proposals and questions in this Green Paper, following a significant programme of more than 40 events where people have shared with us their views on the benefits system and their priorities for change. I’d like to thank everyone who has contributed to these discussions for sharing your knowledge, experiences and enthusiasm.

We have heard that some people find it difficult to interact with the benefits system. They can feel afraid to access benefits and can find health assessments a difficult, long and challenging process. Shaping Future Support: The Health and Disability Green Paper sets out ways we could make our services easier to access, make our processes simpler and help build people’s trust.

We have already stopped reassessments for people with the most severe conditions that are unlikely to change. We propose ways to further reduce the number of unnecessary assessments, while continuing to ensure support is properly targeted. Alongside this, we propose ways of offering greater flexibility and simplicity in the way that assessments are delivered; including improving the evidence we use to make decisions from health assessments, and learn the lessons of coronavirus where we introduced telephone and video assessments

For people who need extra help to navigate the benefits system, we want to strengthen the role of advocacy so that they can get the right level of support and information first time. Where advocacy support is already available from other sources, we want to look at how we can make sure everybody who needs it has access to the same level of service.

The majority of people are satisfied with the assessment process, but for those who do want to appeal a decision, we must ensure this process is as easy and efficient as possible. That is why Shaping Future Support: The Health and Disability Green Paper explores further ways to improve the decision making and appeals process.

And we plan to make it quicker, simpler and easier for people approaching the end of their lives to claim benefits by changing the Special Rules for Terminal Illness. This change follows an evaluation where we heard the views of people nearing the end of their lives, their families and friends, the organisations supporting them and the healthcare professionals involved in their care. This will mirror the current definition of end of life used across the NHS and we will seek to raise awareness of this vital support.

I am proud that since 2013 we have witnessed record levels of disability employment, and significant progress has been made on our commitment for an additional 1 million more disabled people in work by 2027. Disabled people and people with health conditions are benefiting from intensive employment support through our Plan for Jobs, which builds on the more active support we have introduced through Universal Credit and our existing employment programmes. But there is still more we can do. Disabled people rightly want the same work opportunities that everyone else has access to. To meet that aspiration, we must make further positive changes, which is why this Green Paper explores how we could go further to help reduce the challenges disabled people can still face in starting, staying and succeeding in employment.

Shaping Future Support: The Health and Disability Green Paper represents an important step for improving the benefits system, increasing opportunities for employment and helping more people to lead independent lives. It is part of a wider package of support for disabled people that includes the National Disability Strategy which, for the first time, represents focus and collaboration across Government to set out a wide-ranging portfolio of practical changes we can take to help people in every aspect of daily life. Our Health Is Everyone’s Business consultation response also looks at how employers can support people at work.

I hope you will take the opportunity to have your say on all our proposals by responding to the consultation questions in Shaping Future Support: The Health and Disability Green Paper.

Justin Tomlinson

Minister for Disabled People

Executive Summary

1. The Government has ambitious plans to support disabled people and people with health conditions to achieve their full potential and live better for longer. This Green Paper, the National Disability Strategy and the Health is Everyone’s Business consultation response each form part of our holistic approach to supporting disabled people and people with health conditions to live independent lives and start, stay and succeed in employment.

2. The National Strategy calls for action across Government and wider society. This will look at how to address broader issues that can limit opportunities for disabled people.

3. Our response to the Health is Everyone’s Business consultation is being published with the Department of Health and Social Care. This will set about improving the support provided to employers and employees, to reduce the number of people we see leaving employment because of a disability or health condition.

4. Alongside this work, this Green Paper consults on the following aspects of our support for disabled people and people with health conditions:

- How well our services work for people, and what more we can do to make improvements and build trust.

- How effectively we are supporting people to start, stay and succeed in employment. We recognise that, where people are able to work, appropriate employment has a vital role to play in supporting good mental and physical health.

- How successful the changes we have made to the benefits system since 2010 have been. We consider whether we need to re-think any aspect of these changes or go further. We want to explore whether our current system encourages and supports people in the best way.

5. Throughout this Green Paper, we are guided by three priorities. These are:

- Enabling independent living;

- Improving employment outcomes; and

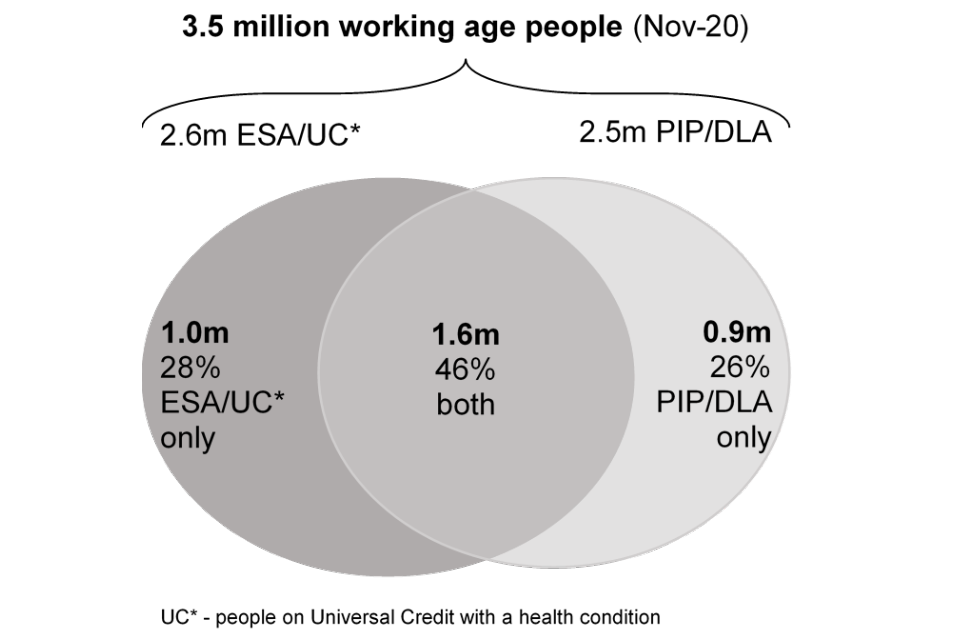

- Improving the experience of people using our services.

6. This Green Paper has been informed by the experiences of disabled people and people with health conditions who use our services. We have talked with hundreds of people and organisations to ensure that we know what is and is not working. This consultation focuses on those areas that we may need to change.

7. Alongside this, we have analysed existing data and evidence as well as carrying out new research. This has provided us with a detailed understanding of what is happening now. This evidence is shared throughout this Green Paper. It is available in more detail in the supporting data pack and in our published research.

8. We know that we can make more progress. We have already delivered changes to our services and support in the last ten years that have made a real difference. For example, we have delivered more employment support through Universal Credit (UC) and new employment programmes. By the end of 2019, the number and rate of disabled people in employment was the highest it has been since comparable records began in 2013[footnote 1].

9. We are proud of this Government’s commitment to supporting disabled people. However, the amount of public money we spend on benefits for disabled people and people with health conditions is growing every year, and it is vital we ensure that this money is spent in the most effective way possible.

10. In this Green Paper we consider how to address some of the short- and medium-term issues in health and disability benefits. These include:

- Improving signposting to wider services at an early stage. In particular, we want to improve signposting to health services, so that people are better able to access treatment and support;

- Testing advocacy for people who struggle the most to access and use the benefits system;

- Continuing to improve our employment support so that more people can start, stay and succeed in work. This is particularly important given the challenges we are seeing in the wider economy as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. This work includes exploring greater join-up between employment support and health services; and

- Improving the support for, and expectations of, employers, to help prevent people with a health condition or disability falling out of work;

- Exploring how to conduct assessments in different ways. This includes through the use of telephone and video assessments;

- Continuing to reduce repeat assessments where a person’s health is unlikely to change;

- Continuing to increase the quality and accuracy of the decisions we make on benefit entitlement;

- Exploring further improvements to our mandatory reconsideration and appeal processes; and

- Improving the information we use to make decisions. This includes securing better medical evidence to increase the speed and likelihood of people getting the correct level of support at the outset.

11. We also want to consider whether we should make more fundamental changes over the longer-term. We want to hear how the benefits system could be designed differently to help more people work and live independently and explore new approaches to providing support.

12. We want to hear from you about the approaches we should consider. Crucially, we want your views on whether we can achieve our ambition within the current structure of health and disability benefits or whether wider change is needed.

13. This consultation is an important step towards making changes that will improve our services, increase opportunities for employment and help more people to live independent lives. Our approach must be informed by different views and opinions, particularly those of disabled people and people with health conditions.

Introduction

14. This Government has ambitious plans to support and empower disabled people and people with health conditions. The National Disability Strategy will be published shortly. This will outline practical changes to tackle the day-to-day challenges disabled people face. It will also set out the Government’s vision to transform the lives of disabled people by taking action across Government and wider society.

15. This Green Paper will explore how the benefits system can better meet the needs of disabled people and people with health conditions. As such, it forms an important part of the Government’s wider plans and is this Department’s main contribution to the National Disability Strategy.

16. A number of publications led by other Departments, will also explore support for disabled people and people with health conditions, as follows:

- The Department of Health and Social Care is working to refresh the Autism Strategy. This will improve understanding of autism and the provision of services and support for autistic people. It will set out steps to enable more autistic people who are able to work to do so.

- The Department for Education will also publish a review of support for children with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND). This aims to ensure better outcomes for children and young people with SEND. It will consider ways to make sure the SEND system is consistent, high-quality, and integrated across education, health and care.

17. As well as being linked to work across government, this Green Paper builds on our earlier consultations. We published the 2016 Improving Lives Green Paper[footnote 2] and the 2017 response[footnote 3] with the Department of Health and Social Care. These looked at supporting disabled people and people with health conditions to remain in and return to work, improving assessments for benefits, and helping employers to recruit disabled people. We will follow up on the responses to this Green Paper with a White Paper in mid-2022. This will aim to set out how we can better enable people to take up work and live more independently, and outline the changes we want to make to the benefits system to better address structural and delivery challenges.

18. The 2019 Health is Everyone’s Business consultation[footnote 4], also published with the Department of Health and Social Care, looked at ways to encourage employers to support disabled people and people with health conditions at work. This focused on better and earlier information and support for employers and employees, to help prevent disabled people and people with health conditions losing their jobs through ill-health. We will shortly be publishing the Health is Everyone’s Business consultation response. While important progress is being made, we know there is more to do.

19. The coronavirus pandemic has affected how we live and work. Since spring 2020, we have been providing support in the midst of a public health emergency. More people than before have been claiming benefits: in the first six weeks of the UK Government’s response to the pandemic, we received over six times the normal number of claims for benefits, including Universal Credit (UC) and Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) [footnote 6]. Many disabled people and people with health conditions have been identified as clinically extremely vulnerable (CEV) and, as such, advised to shield for significant periods since the start of the pandemic. Since the pandemic began, we have rapidly adapted our ways of working to continue to support people. The UC system in particular has shown resilience and flexibility in how it has responded to the challenges posed by the pandemic.

20. By the end of 2019, the number and rate of disabled people in employment were the highest they have been since comparable records began in 2013[footnote 5]. As we come through these unprecedented challenges, we are still committed to getting 1 million more disabled people into work by 2027. The number of people needing our support is forecast to increase[footnote 7]. As we recover from the pandemic, we want to intensify our support for disabled people and people with health conditions.

The Scope of this Green Paper

21. This consultation focuses on the main benefits paid to disabled people and people with long-term health conditions of working age. These benefits fall into two groups:

- Benefits for people who have a health condition or disability that affects their ability to work and who are unemployed or on a low income. These benefits are ESA and UC.

- Benefits to help with some of the extra costs for disabled people and people with long-term health conditions. These are paid to people whether or not people have a job or income, and aim to support independent living. The main extra costs benefit is Personal Independence Payment (PIP), which is replacing Disability Living Allowance (DLA) for adults.

Employment and Support Allowance (ESA)

22. Until recently, ESA has been the main benefit paid to people who have a disability or health condition that affects their ability to work. People who receive ESA are placed in one of two groups. Where a person is able to prepare for work, that person will be placed in the Work-Related Activity Group (WRAG). People in the WRAG may be required to do things like write a CV or take part in confidence-building sessions. Alternatively, a person may be placed in the Support Group. Where someone is placed in the Support Group there is no obligation to take part in work-related activity. People in the Support Group receive an extra amount of benefit, on top of their main ESA payment.

23. There are two types of ESA: income-related ESA and contribution-based ESA. Contribution-based ESA is now known as New Style ESA[footnote 8], while income-related ESA (ESA (IR)) is being replaced by UC. In November 2020 952,260 people were claiming ESA (IR) and have not yet moved across to claim UC, while 809,590 people were receiving New Style ESA[footnote 9].

Universal Credit (UC)

24. UC is a benefit for working-age people who are unemployed or in low-paid work and who have limited savings. It was introduced in 2013 and is simplifying the benefits system by replacing six different benefits with one. A person does not need to be disabled or have a health condition to be able to claim the main UC payment (the standard allowance). Where a person who is eligible for the main UC payment has a health condition which affects their ability to work, that person may be found to have limited capability for work (LCW) or limited capability for work and work-related activity (LCWRA). People found to have LCWRA receive an extra amount of benefit in addition to the main UC payment.

25. We consider support for people claiming UC who have LCW and LCWRA in this Green Paper. We also consider people claiming UC with approved evidence of a health condition[footnote 10] as well as people claiming UC who are waiting for an assessment. Throughout this Green Paper we will refer to these people as people claiming UC with a health condition. People claiming UC with a health condition remain part of the overall UC caseload. 782,000 people of working age were claiming UC with a health condition in November 2020[footnote 11].

Personal Independent Payment (PIP)

26. Unlike UC and ESA, PIP aims to help people with the extra costs of a disability or long-term health condition. PIP is paid regardless of income or savings. The amount paid depends on the impact of a disability or health condition. PIP was introduced in 2013 to replace DLA for adults of working age to provide more support for the people who need it most. In November 2020 there were 2.5 million working-age people receiving extra costs benefits. The majority of these people are claiming PIP[footnote 12].

Other Support

27. In November 2020, 3.5 million working-age people were claiming at least one of PIP/DLA or are claiming ESA or UC with a health condition. Of these, 1.6 million working-age people claim PIP/DLA as well as ESA or UC with a health condition[footnote 13].

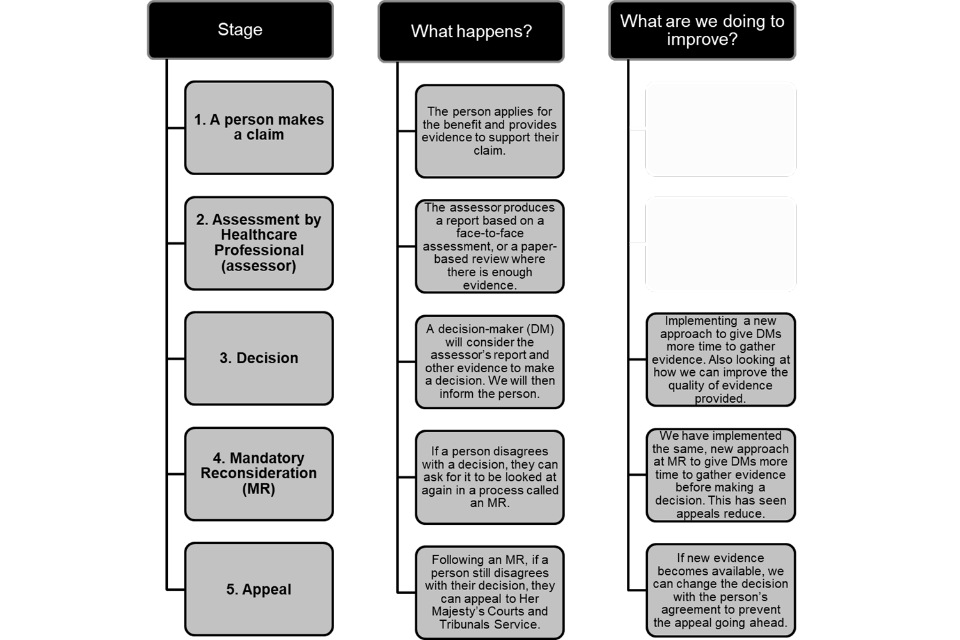

28. We use ‘functional assessments’ on PIP, ESA and UC LCW/LCWRA. A functional assessment is one which considers the impact of a health condition on a person’s ability to carry out activities, rather than just the health condition itself. The Work Capability Assessment (WCA) is used to help decide financial entitlement and employment support for ESA and UC. We use a separate assessment to determine entitlement for PIP.

29. As well as the payment of benefits, the help we offer working-age disabled people and people with health conditions includes employment support (for people claiming UC and ESA). In addition, mobility support is provided through the independent Motability scheme (for people receiving higher-rate PIP and DLA mobility payments) and support to apply for UC is available through the Help to Claim service.

30. Although the scope of this Green Paper is restricted to support for working-age disabled people and people with health conditions, many of the issues we explore will also resonate with older people who have similar needs. There are 284,000 people over State Pension age who receive PIP[footnote 14]. The benefits system also provides financial support for people over State Pension age through Attendance Allowance (AA). AA can help towards the extra costs faced by pensioners who require long-term care or supervision as a result of being disabled or having a health condition. Disabled people and people with health conditions may also have unpaid carers. We provide support for unpaid carers through Carer’s Allowance or extra amounts for carers in UC and other benefits[footnote 15]. As we consider the responses to this consultation we will look at the potential impacts on support for people with similar needs over State Pension age, and unpaid carers.

Why Change is Needed

31. Starting, staying and succeeding in work can be more difficult for many disabled people than non-disabled people. Disabled people and people with health conditions can also face other challenges which make it harder to live equal, independent lives.

32. Currently one in three people aged 16-64[footnote 16] in the UK has a long-term health condition and one in five people aged 16-64 in the UK is disabled[footnote 17]. The number of working-age people reporting a disability increased by 20% between 2013 and 2019[footnote 18], and is forecast to continue to grow[footnote 19]. The number of older working-age people has increased and, typically, people’s health declines with age. However, changes in the age of the working-age population do not fully explain the increase in the number of people claiming health and disability benefits. There are likely to be many factors, including the increase in the proportion of people reporting a mental health condition[footnote 20] [footnote 21]. In 2020 50% of working-age people receiving ESA and 41% of working-age people receiving PIP/DLA had a mental health condition as their main condition[footnote 22].

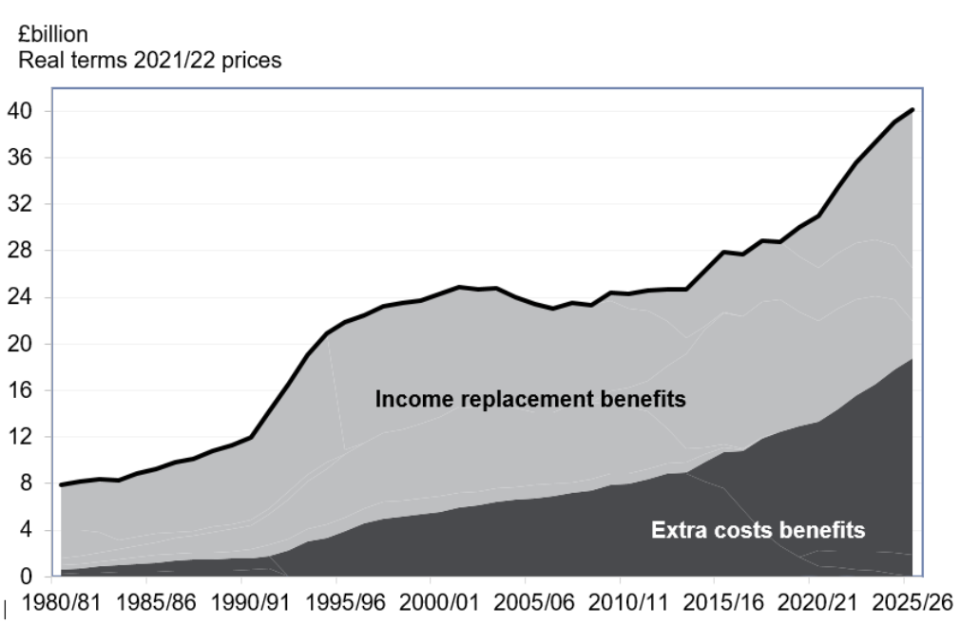

33. Spending on benefits for disabled people and people with long-term health conditions is currently the highest it has ever been[footnote 23]. In 2021/22 we are forecast to spend £33 billion to support working-age adults on PIP/DLA, ESA and people claiming UC with a health condition. Over the next five years this spending is forecast to continue to increase[footnote 24].

34. We want to make sure that money spent on supporting disabled people and people with health conditions has a positive impact on their lives. Spending on the main benefits claimed by disabled people and people with health conditions is at a record level[footnote 25] and there has been positive progress on outcomes. By the end of 2019, the number and rate of disabled people in employment were the highest they have been since comparable records began in 2013[footnote 26]. The difference between the employment rate of disabled people and the employment rate of non-disabled people, known as the disability employment gap, also reduced between 2013 and 2019[footnote 27].

35. Our ambition is to do more and go further to improve employment and independent living outcomes for disabled people and people with health conditions. This is not only good for the individual, but good for everyone. Having one extra disabled person in full-time work, rather than being out of work longer term, would mean Government could save and re-invest £15,000 a year[footnote 28].

36. We want to continue to reduce the disability employment gap, which currently stands at 28.6%[footnote 29]. According to the latest figures, 43% of people living in poverty live in a family where someone is disabled[footnote 30]. Disabled people and people with health conditions have told us that change is needed, as set out below.

Listening to Disabled People and People with Health Conditions

37. We have been listening to disabled people and people with health conditions. Their feedback has helped shape our proposals for change. To make sure we heard a range of views which reflect people’s lived experience, the Minister for Disabled People, Health and Work held a series of Green Paper events. Disabled people and people with health conditions, local support organisations, national charities, employers and think tanks have all taken part. To understand the needs of people living in different parts of Great Britain, we have held events in large towns and cities as well as in more rural and coastal areas. To continue listening to people during the pandemic, we have also held virtual events. More information about when, where and how these events have been conducted is provided in Annex A.

38. We have also collected evidence through research. In recent years, independent researchers have surveyed and interviewed thousands of people claiming health and disability benefits. This work has been done to understand more about people’s experiences of claiming benefits[footnote 31] and to establish where we can make improvements[footnote 32].

39. We are grateful to everyone who has attended these Green Paper events and taken part in research. We reflect on the insights that have been gathered in every chapter of this Green Paper. We will continue to listen to disabled people and people with health conditions throughout the consultation period and beyond.

Priorities for Change

40. The insights from Green Paper events have helped us develop three priorities for change. These priorities will help us to improve outcomes for disabled people and people with health conditions. The three priorities are:

- Enabling independent living;

- Improving employment outcomes; and

- Improving the experience of people using our services.

41. Each of these priorities is explained below.

Enabling independent living

42. Independent living is about extending opportunities, so disabled people and people with health conditions can achieve their full potential and live the lives they choose.

43. At present, we enable independent living mainly through the payment of benefits and the provision of employment support. People who receive higher-rate PIP or DLA mobility payments can also swap their payments to access mobility support through the independent Motability Scheme.

44. At Green Paper events people said that we could do more to make sure disabled people have equal access to the same opportunities as non-disabled people. People asked us to provide better and broader support to help meet the specific needs of disabled people and people with health conditions. This includes help to overcome obstacles to independent living, such as difficulties in accessing healthcare, issues with transport and a lack of suitable local jobs. People told us that government services need to be more accessible for disabled people, so that people can get the support they need. People said that we need to work harder to provide reasonable adjustments to the services provided by this Department. The support we offer could also be better joined-up, both internally (between different benefits) and externally (with services offered by other government departments and agencies, the NHS, local authorities and charities).

45. Our first priority is to support disabled people and people with health conditions to live independently and achieve their potential. This means that people should be provided with the right amount of financial support, given the opportunity to make their own choices, have equal access to services, be supported to access healthcare and treatment, and be able to participate in society on the same basis as other people.

Improving employment outcomes

46. We want disabled people and people with health conditions to have opportunities and live a full life. Being in appropriate work is good for health and being out of work can have a negative impact on people’s health[footnote 33]. We want to focus more on what disabled people and people with health conditions can do, rather than what they cannot. Through effective employment support we can help people improve their health and reach their potential.

47. The Government has committed to continue reducing the disability employment gap. We have also committed to see 1 million more disabled people in employment between 2017 and 2027. We want to do our best to make sure that disabled people and people with health conditions have the same opportunities as others to fulfil their potential. We want to help disabled people and people with health conditions to stay in work wherever possible. As set out in the Health is Everyone’s Business consultation[footnote 34], preventing people from falling out of work is a key part of our ambition. We also want to do more to help people prepare for and enter employment.

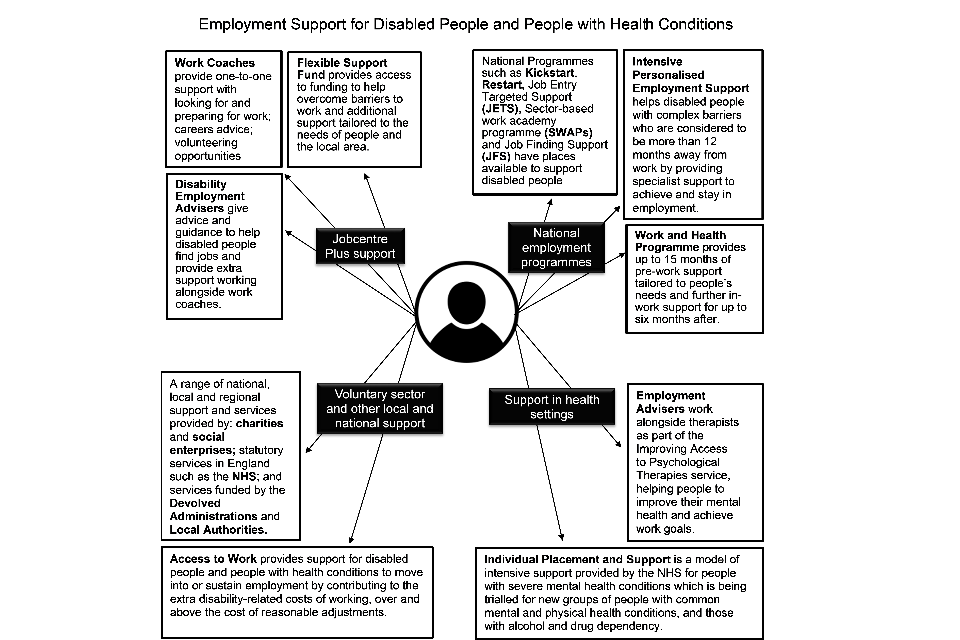

48. We already offer employment support to people claiming benefits such as UC and ESA. This is delivered through work coaches in jobcentres and employment support provision including the Work & Health Programme and Intensive Personalised Employment Support (IPES). We also support disabled people in work through Access to Work grants and work with employers to help them recruit and retain disabled people through the Disability Confident scheme.

49. At Green Paper events, disabled people and people with health conditions expressed a desire to contribute to society in such a way as to be able to balance working with managing their health. People recognise the value of employment but want us to take more account of their circumstances, including the impact of being disabled or having a health condition, and the restrictions of their local area. People would like support and training to be more tailored to their needs. Some people felt afraid of taking steps to prepare for or try out work in case this affected their benefits. People also asked for better support from employers and this Department to stay and succeed in work.

50. We have conducted research with disabled people and people with health conditions on ESA and UC[footnote 35] to understand their feelings about preparing for work and working. This showed that people felt health-related issues were often a challenge. People were worried that their health could make it difficult to find or keep a job, or that working could have a negative impact on their health.

51. The same research indicates that disabled people and people with health conditions do not always feel comfortable taking up our employment support. Some people who were not in work were concerned that doing paid work could risk them losing their benefits or having to reapply for benefits if a job did not work out. Some people felt worried about being left without income during the period between their benefit payments stopping and receiving the first wages from a new job[footnote 36].

52. Some of the people who took part in this research were claiming ESA rather than UC. UC is an in- and out-of-work benefit which helps to address some of the concerns people expressed. For example, UC allows people to try out work and stay on benefit in the knowledge that their benefit will continue if the job does not work out.

53. Our second priority is to reduce the difficulties disabled people and people with health conditions can still face in starting, staying and succeeding in employment. We want to offer better and more tailored employment support, whether people are in or out of work. We want to help prevent disabled people and people with health conditions from falling out of employment. We want to work with employers to improve employment outcomes wherever people may be able to work, now or in the future.

Improving the experience of disabled people and people with health conditions

54. Most people receiving services from this Department agree that we do what we say we will do, that we treat people fairly and that our staff are helpful, polite and respectful[footnote 37]. Where disabled people and people with health conditions have said their experience could be better, we want to take ambitious steps to improve.

55. At Green Paper events some people have said it is difficult to interact with us. People may feel afraid of having to use the benefits system. People sometimes struggle to apply for benefits and can find health assessments difficult. People said they did not always trust assessments, or the decisions that they led to. Where people challenge a benefit decision this can sometimes lead to a long and difficult process. A lack of trust can affect people’s willingness to accept offers of employment support.

56. Our third priority is to improve the experience of disabled people and people with health conditions by continually listening, learning and improving. We want to make our services easier to access and our processes simpler, where we can. We want to make improvements that will help build people’s trust. We want to explore ways to offer more and better support for the people who need it most.

Spending on Health and Disability Benefits

57. In the last seven years we have seen an increase of 20% in the number of working-age people reporting a disability[footnote 38]. In 2021/22 we are forecast to spend a record £58 billion of public money on benefits for disabled people and people with health conditions[footnote 39]. Of this, £33 billion is spent on working-age people in Great Britain, including spending devolved to the Scottish Government for working-age PIP and DLA. Between 2021/22 and 2025/26 we expect real terms[footnote 40] spending on Great Britain working-age health and disability benefits to increase from £33bn to £40bn[footnote 41], an increase of 20% and an increase in expenditure as a proportion of GDP over this time. We are proud of this Government’s commitment to supporting disabled people. However, it is vital to ensure that public money is spent in the most effective way possible.

58. The Government is committed to improving the lives of disabled people and people with health conditions. We want to help people overcome challenges to independent living. We also want to support people to move into work wherever possible. Rising spending on health and disability benefits suggests there is more to be done to enable people to live independent lives and work. We want to consider the support we currently offer and explore whether there may be better ways to provide support.

59. We must ensure that disabled people and people with health conditions are effectively supported. This Green Paper will consider whether the money we spend on supporting disabled people and people with health conditions is spent well. This includes ensuring that we have the right checks in place to make sure we are paying people the right amount of money for their particular circumstances. This is because we want to ensure that the health and disability benefits system is effective and sustainable in the future.

Across the United Kingdom

60. The UK Government is committed to improving the lives of disabled people and people with health conditions across the Union. We welcome views from people wherever they live, including in Northern Ireland. However, the specific areas covered in this Green Paper relate to Great Britain only.

61. This section sets out the extent to which this consultation will apply in each part of the UK. The Minister for Disabled People, Health and Work in the UK Government has overall responsibility for disabled people across the United Kingdom.

62. The UK Government is responsible for policies on employment support and social security in England and Wales, and shares that responsibility in Scotland with the Scottish Government. In Northern Ireland, these areas are the responsibility of the Northern Ireland Executive. The Department for Communities in Northern Ireland and the Department for Work and Pensions in Great Britain seek to maintain similar social security systems.

63. In Scotland, some parts of the social security system are devolved[footnote 42]. This includes PIP and DLA. These will be replaced over time by new Scottish Government benefits[footnote 43]. Once these new benefits have been introduced, the proposals relating to PIP and DLA considered in this Green Paper will not apply in Scotland. This includes the changes we propose to the Special Rules for Terminal Illness (SRTI) in PIP and DLA, which are outlined in Chapter 3 of this Green Paper[footnote 44]. The changes proposed for ESA and UC will apply in Scotland, since these benefits will remain the responsibility of the UK Government.

64. With respect to employment support, the Scottish Government has powers to set up contracted programmes to help disabled people into work. It has similar powers to support people who are at risk of long-term unemployment, provided this support lasts for 12 months or longer. The UK Government remains responsible for the support provided by Jobcentre Plus, and for other contracted employment support in Scotland. The proposals in this Green Paper apply in Scotland to areas which are reserved to the UK Government.

65. In Wales, employment support and social security are the responsibility of the UK Government. This means that the proposals in this Green Paper relating to those areas, including PIP and DLA, apply in Wales.

66. The case studies in Chapter 2 of this Green Paper provide insights on delivery in Scotland and Wales.

67. The Scottish and Welsh Governments are responsible for health, local government, education, skills and social care. Where the proposals set out in this Green Paper relate to these areas, the consultation and views will focus on what this means for England.

68. We remain committed to working with the Scottish and Welsh Governments, and with the Northern Ireland Executive, to consider how best to deliver support for disabled people and people with health conditions.

Summary

69. The three priorities of enabling independent living, improving employment outcomes and improving the experience of people using our services will be considered in each of the following chapters:

- In Chapter 1 we will explore ways to provide more support to help meet the needs of disabled people and people with health conditions and allow them to more easily access and use benefits and services.

- In Chapter 2 we will consider how to continue to improve employment support for disabled people and people with health conditions, and how to encourage people to take up that support, where possible.

- In Chapter 3 we will look at short-term improvements to our current services such as improvements to assessments and decision making, to improve the experience of disabled people.

- In Chapter 4 we will describe how we have been working with disabled people and people with health conditions, medical professionals, charities and academics to consider changes to future assessments, and explore alternative approaches.

- In Chapter 5 we will explore changes that could be made to the structure of the main benefits claimed by working-age disabled people and people with health conditions.

70. In each chapter, we want to hear your views on the areas for consultation. This Government and this Department have bold ambitions for disabled people and people with health conditions. This Green Paper is a crucial part of the action we are taking under the National Disability Strategy. Our priority now is to hear your suggestions on how to transform these ambitions into reality.

Chapter 1: Providing the Right Support

Chapter Summary

We have heard that people can sometimes find it difficult to access health and disability benefits and related support. In this chapter we explore how to improve this by:

- Improving signposting. In particular, we want to improve signposting to health services, so that people are better able to access treatment and support;

- Testing advocacy for people who struggle the most to access and use the benefit system; and

- Exploring further support for mobility needs.

Introduction

71. Each person is likely to have different support needs at different times. We want to do our best to make sure disabled people and people with health conditions have the right support to meet these needs and live independently.

72. Lots of support, including financial, health and employment support, is already available to disabled people and people with health conditions from a range of sources. Most people feel it is easy to access and use our services[footnote 45]. However, at Green Paper events, some people said that it can be difficult to know what wider support exists and how to access it. At the same events, we heard that it is not always clear which of our benefits people might be eligible for. People have also told us that our benefit forms can feel long, stressful and difficult to fill in. Finally, we have heard that the reasonable adjustments people ask for when using our services are not always provided.

73. We want to do more to ensure everyone has a smooth experience and can access the right help. To achieve that, in this chapter we will explore ways to help people access and use the current health and disability benefits system and wider services.

What We have Already Done

Improving reasonable adjustments

74. A reasonable adjustment is a change that removes or reduces the barriers disabled people face. We want to make sure that our services are fully accessible to support people and offer the reasonable adjustments that people need. For example, we have a visiting service for people who are not able to get to one of our assessment centres and we provide communications in alternative formats.

75. The Department already has in place a wide range of reasonable adjustments for disabled people. These include communications in braille, large print and electronic formats for visually impaired people, British Sign Language (BSL) interpretation for deaf and hard of hearing people, quiet rooms for autistic people, and coloured paper for dyslexic people. We also offer email as a reasonable adjustment for people who cannot access print or find it difficult to use the telephone to contact us.

76. We have been working with organisations for people with a learning disability to develop a Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) Easy Read standard and publish new Easy Read guides on topics such as Access to Work which are accessible online. Further Easy Read products for PIP and UC are also available on the UK Government website, GOV.UK.

77. We are continually working to improve the reasonable adjustments we provide. In October 2020, we completed the roll-out of the Video Relay Service across all benefits. This allows people who use BSL to contact us by telephone. We are also testing the introduction of Video Remote Interpreting in our services. This would allow BSL users to communicate with us through an interpreter on a video call.

78. We are working on improving how we collect and record alternative formats and reasonable adjustments on our systems so that people will not need to request a change to their communications more than once. We have also set up a Reasonable Adjustments Forum with disability charities, to continue to improve accessibility. We want everyone to get the support they need and would like to hear what more we could do.

Consultation question

What more could we do to improve reasonable adjustments to make sure that our services are accessible to disabled people?

Improvements to forms

79. We use forms to understand the challenges disabled people and people with health conditions face that affect their ability to work and live independently. For PIP, we have the PIP2 ‘How your disability affects you’ form. For UC and ESA, we use the UC50 and ESA50 ‘Capability for Work’ forms.

80. It can be difficult to explain the effects of a health condition or disability, as illustrated in the case study below.

Case study: The need to improve our forms

James, an unpaid carer, told us that if our forms were easier to understand, people would need to rely less on medical professionals to provide support when applying for benefits. The focus of the forms on what a person cannot do can often leave people feeling more vulnerable and less positive. Nothing prepares people for how complicated the forms are and what they are asking people to describe or prove. James said that he had to fill in 42 pages of information which took him two whole days. He had to send lots of emails and contact multiple healthcare professionals to obtain the necessary supporting evidence.

81. To address this, we commissioned research to understand more about how to improve our forms[footnote 47]. We are now making many of the changes that people asked for. Following the discussions that took place with disabled people and people with health conditions through research and at Green Paper events, we are improving our forms. For example, on the PIP2 form we are:

- Simplifying instructions and reducing repeated information;

- Adding examples that show how to explain the impact of certain conditions;

- Changing the descriptions of some activities to make it clearer how they relate to different conditions; and

- Explaining more clearly what happens after returning the form.

82. At Green Paper events, some people told us that they prefer online forms. During the coronavirus pandemic, we introduced an online New Style ESA claim service. We are developing a fully digital version of the UC50 ‘Capability for Work’ form. We are also developing an online PIP2 form which can be automatically saved and uploaded onto our systems. We hope to offer the improved digital PIP2 form by summer 2021. We will always offer alternatives to people who cannot access online forms.

Signposting and support to help people access benefits

83. Signposting means making people aware of other benefits and services which could help them, so that people can more easily access vital support. Signposting can be particularly helpful when people are claiming benefits for the first time. We already provide a range of support to 3.45 million disabled people and people with health conditions of working age, including through PIP and UC[footnote 48]. At Green Paper events, we heard that people would like more information, signposting and practical support to help meet their financial and health-related needs.

84. We have set out below examples of processes that are in place and changes underway which make it easier for people to identify and access relevant support:

- Improving information on GOV.UK – To help people access the relevant benefits online, we are making it easier for people to find information on GOV.UK. We know there is a lot of information on this website so people can struggle to know where to go for what they need. We are working with GOV.UK users, local partners and other organisations to improve the information we provide online.

- Signposting to other services – We want to find ways to signpost people to other support and services. For example, in the letter people receive with their PIP decision, we include information about other benefits, support and services that could be helpful. Work coaches also identify issues that could make it more difficult for people to start work, and find help to address these. This can include signposting people to local services and support for issues related to mental health, housing, debt management and wellbeing.

- Special Rules for Terminal Illness – Where people are nearing the end of their lives, it is important that the process for securing support is as simple as possible. Since the end of 2020 we have been offering a full benefit check on the PIP telephone service for people who have applied for PIP through the Special Rules for Terminal Illness. This identifies the financial support to which people may be entitled.

- Extra Support through Advanced Customer Support Senior Leaders (ACSSLs) – In 2020, we introduced a network of 31 ACSSLs. These roles are located throughout England, Scotland and Wales. Where people need extra support to access our benefits or services, ACSSLs support and signpost people to a range of local provision.

- Support through Help to Claim – Since April 2019, we have funded[footnote 49] Citizens Advice and Citizens Advice Scotland to successfully deliver our Help to Claim programme[footnote 50]. As illustrated in the case study below, ‘Help to Claim’ offers independent, tailored and practical support to help people make a UC claim and receive their first full payment on time.

Case study: Support through Help to Claim

Pauline had been on contribution-based ESA which came to an end after 12 months. She rang the ESA helpline and was told to apply for UC online. Pauline has poor mental health and is a carer for her disabled father. Pauline needs support with managing money and budgeting. She also struggles to use the internet and was unsure of her entitlement and was not able to start an application for UC online.

This situation was making her anxiety worse. A Help to Claim adviser was able to support Pauline, check her entitlement and help her through the application process. The adviser gave Pauline information so that she could check that her first UC payment was correct, as well as a number to call if she had any concerns at the beginning of her claim. Pauline was very grateful for the support she received to claim UC.

85. While we have made progress, we know more needs to be done. We want to go further to take account of and respond to people’s different needs and improve the experiences of people using our services. We would like to hear how signposting can help us to do this more effectively.

86. In particular, we know that access to appropriate health treatment is vital to enable people to live full and independent lives. Health-related issues can make it harder for people to take up employment support, as well as to start and stay in work. Because of this, we especially want to improve signposting to health services, so that people are better able to access treatment.

Consultation questions

What more information, advice or signposting is needed? How should this be provided?

Going Further

Testing advocacy support

87. At Green Paper events, we heard about the power of advocacy for disabled people and people with health conditions. Advocacy is more than signposting; it is about supporting each person to help ensure their needs are met. Many people can use the benefits system independently or have the help of friends, family, charities or other support networks[footnote 52]. People can also use Help to Claim for UC. For people who do not have that support, we want to test providing advocacy so that people can get the right level of support and information first time. Where advocacy support is already available from other sources, we want to look at how we can make sure everybody who needs it has access to the same level of service[footnote 53]. 88. Evidence supports what we have heard at Green Paper events: that extra support to help people navigate the benefits system can help change people’s lives[footnote 54]. To help us design and test advocacy support, we want to explore how it might look. We will explore in our test of the service whether it is feasible to deliver advocacy support and whether this offers value for money.

89. We recognise that improvement to our services is an important part of making the benefits system easier to use. Chapter 3 looks at what we could do to improve the experience of disabled people using our services. Providing advocacy would not be an alternative to these improvements but an additional form of support for people who need it.

How advocacy support might look

90. We suggest that advocacy support could be based on these principles:

- Advocacy could help people find information and provide practical support (such as filling in forms) but would also help people to have their voice heard on matters affecting them.

- This support would not be available for everyone; it would only be offered to the people who need it most. It could be for people who do not already have the support of charities and other organisations. Evidence suggests that advocacy could benefit disabled people in particular[footnote 55] but it would not need to be limited to disabled people. It could also be offered to other people who are not able to find their way through the benefits system without extra support.

- It should be delivered in a way that ensures it offers advice that people can trust.

- Advocacy should not duplicate existing support but fill gaps in provision. It should complement the help other organisations provide.

- It should be flexible enough to support people whenever they need help, and not just at the beginning of their claim. This will help meet the needs of vulnerable claimants.

- Advocacy should aim to help people to achieve certain outcomes rather than being open-ended, so that it helps people to become independent from the service[footnote 56].

- Advocacy could do more than just help people to access and use the benefits system. It could also provide support to address wider issues in people’s lives (such as access to health and care services, and housing) which we know can affect people’s ability to manage their health condition or disability.

91. We want to hear from people who could benefit from advocacy and their representatives to help us develop this test. We are keen to hear views on the principles we have proposed and would like to understand whether there is anything else we should consider.

Consultation questions

- Do you agree with the principles we have set out for advocacy support?

- How might we identify people who would benefit from advocacy?

- What kinds of support do you think people would want and expect from advocacy?

Exploring support for mobility needs

92. The ability to move around and make journeys is a key part of independent living. We currently provide mobility allowances through PIP and DLA. People can choose to spend these allowances however they wish.

93. A popular way to spend mobility allowances is through the independent Motability scheme. The Motability scheme, which is operated by the independent Motability charity, helps people meet their mobility and travel needs. It allows disabled people and people with health conditions to use their PIP/DLA higher-rate mobility allowance to lease a new affordable car, Wheelchair Accessible Vehicle, scooter or powered wheelchair. In 2020 1.8 million people were receiving the PIP Enhanced mobility or DLA Higher mobility award and were eligible for the Motability Scheme. In that year there were 635,000 customers using the scheme[footnote 57].

94. The charity which provides the Motability Scheme benefits from a range of tax concessions[footnote 58] and the direct transfer of mobility allowances[footnote 59]. This means that they are able to provide leases that are around 44% cheaper than they would be otherwise[footnote 60]. Currently, 34% of eligible people join the Motability Scheme[footnote 61]. The support provided by the scheme is illustrated in the case study below. We want to hear how disabled people and people with health conditions use their PIP and DLA mobility payments, particularly where people do not use Motability, and whether there is more we could do to support people’s mobility needs.

Case study: The Motability scheme

Nazmin, 37, has Arthrogryposis Multiplex Congenita. This is a condition that causes limb weakness. Nazmin decided to use her mobility allowance to join the Motability Scheme after she attended a regional driving assessment centre to find out which adaptations would enable her to drive a car herself.

Before I found out about Motability, I used to have to travel by taxi, but this wasn’t ideal as they were frequently late. This experience gave me the incentive to pass my driving test. The advisors at the driving assessment centre suggested what adaptations would be suitable for me and informed me about the Motability Scheme and the range of help that both it and the charity could provide me with.

Nazmin received a grant from Motability for adaptations to be added to her new vehicle. She has a hoist to help move her powered wheelchair in and out of the vehicle, a powered tailgate and hand controls.

Motability and the Motability Scheme have been an absolute godsend and continue to be so. It is incredibly hard to put into words just how much my vehicle has helped over the years and continues to help. I started using the Scheme in 2004 and in that time, it has enabled me to go to university and flourish within my studies. It enables me to go out to visit friends and family, hospital appointments and interviews. It enables me to work, to contribute to and feel part of society and to live a fulfilling life.

Consultation question

Are we meeting disabled people’s mobility needs? Please tell us why/why not.

Summary

95. We have listened to what people have told us at Green Paper events, through surveys and research. Although most people find our services easy to access[footnote 63], we know that some disabled people and people with health conditions can struggle to access benefits and use services. Because of this, we want to do more to help people find their way through the benefits system and access wider support. This includes improving signposting to other services, such as housing and health, and testing advocacy support.

96. We believe that together, improving signposting and offering advocacy could make it easier for people to use the benefits system and help meet their wider needs. Since being able to move around and travel freely is an important need for many disabled people, we also want to understand what more we can do to help people meet their mobility needs.

Chapter 2: Improving Employment Support

Chapter Summary

There has been good progress on disability employment since the 2016 Improving Lives Green Paper[footnote 64]. By the end of 2019, the number and rate of disabled people in employment were the highest they had been since comparable records began in 2013[footnote 65]. However, we want to go further to help more disabled people and people with health conditions prepare for, start, stay and succeed in work, where it is right for them. In this chapter we explore:

- Taking action now through early intervention. This means supporting people to stay in work and providing back-to-work support earlier to reduce the risk of people falling into long-term inactivity.

- How to ensure our that our jobcentres are welcoming and engaging, to encourage more people to take up our employment support. This includes using a new approach to conditionality. Our staff also need to be expert in providing and referring to employment support for disabled people and people with health conditions.

- Personalising employment support, recognising that one size does not fit all. We also ask what more we can do to encourage people in the Support Group/LCWRA to take up our voluntary employment support.

Introduction

97. Work has a vital role to play in supporting good mental and physical health[footnote 66]. It can also provide greater financial security and enable people to live independently. Improving employment outcomes for disabled people and people with health conditions can help unlock their talents, promote equal access to opportunity and contribute to the economy. This is why we want to reduce the difference between the employment rate of disabled and non-disabled people, which is known as the disability employment gap.

98. In 2017, we set a goal to see 1 million more disabled people in work by 2027[footnote 67]. In the three years since, the number of disabled people in work grew by 800,000[footnote 68]. The disability employment rate has also increased by 8.4% since comparable records began in 2014[footnote 69]. We now want to intensify our efforts to provide the support disabled people and people with health conditions need, when they need it. We remain committed to achieving the challenging goal of 1 million more disabled people in work and, once we have, we will consider how we can build on this success.

99. In this chapter we consider employment support for disabled people and people with health conditions. We also know that other factors, such as people’s experiences of assessments for benefits and the structure of the benefits system, can affect whether and how people move into and stay in work. These other factors will be considered in Chapters 4 and 5.

100. To improve employment outcomes for disabled people and people with health conditions, we want to support people who are out of work to start, stay and succeed in appropriate employment, wherever it is possible to do so. However, to achieve our goals, it is equally important that we support disabled people and people with health conditions in work to remain in employment. For full context, this chapter should be read alongside the Health is Everyone’s Business consultation[footnote 70]. This contained a range of proposals to support more disabled people and people with health conditions to stay in work. Evidence shows how important it is for an employer to support an employee who is at risk of, or on, long-term sickness absence. Providing more support sooner to employees and employers is vital to reduce the chance of people losing their jobs through ill health[footnote 71].

101. In the forthcoming response to the Health is Everyone’s Business consultation, which we will publish with the Department of Health and Social Care, we will set out our strategy for preventing ill health-related job loss. In this response, we will explain how we propose to improve information, advice and guidance on health, work and disability. This includes work by the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) to lead new guidance on how to manage sickness absence and support people to return to work.

102. In this chapter we explore early intervention. We want to provide back-to-work support earlier when people apply for out-of-work health and disability benefits, through jobcentres and our employment support programmes, in order to reduce the risk of long-term unemployment.

103. We also consider what more we can do to ensure disabled people and people with health conditions feel comfortable taking up our employment support. We look at how to make our jobcentres more welcoming and engaging. We set out the new way we are applying conditionality for disabled people and people with health conditions claiming out-of-work benefits[footnote 72]. Our staff also need to be expert in providing and referring to employment support in order to build trust with disabled people and people with health conditions.

104. Starting and staying in work can be particularly difficult for disabled people and people with health conditions. We know that one size does not fit all and people will have different support needs. Later in this chapter, we set out the wide range of tailored employment support that is available to help meet people’s specific needs. This includes approaches to support that join up employment and health services. We also ask how best to offer voluntary support to people in the ESA Support Group and people claiming UC who have LCWRA.

Early Intervention

105. Preventing people from falling out of work is crucial. Where ill health-related job loss does occur, it is vital to ensure that people can rapidly access appropriate support. We know that the longer someone is out of work, the greater the risk to their long-term health and wellbeing[footnote 73]. As well as exploring early intervention, improved guidance and greater support to help people stay in work, we want to set out changes to Access to Work and Disability Confident that will support employers and employees. We also want to explore providing earlier and more comprehensive support through jobcentres for people who have fallen out of work because of a health condition or disability. This support could be provided before people have a WCA. Where people are able to work, providing this extra support could enable a quicker return to appropriate employment.

Working to support employers

106. Employers play a vital role in supporting disabled people and people with health conditions to stay in work. Soon, we will publish our response to the Health is Everyone’s Business consultation with the Department of Health and Social Care. This focuses on better and earlier support for employers and employees, to help prevent people losing their jobs through ill-health. The response explains how we will clarify and improve information, advice and guidance for employers on health, work and disability. This includes a national information and advice service for employers.

107. The Health & Safety Executive (HSE) will also lead new guidance on sickness absence management and returns to work. We will take steps to improve access to quality occupational health services[footnote 74], particularly for people who work in small and medium-sized businesses.

108. We know that the proportion of people with a mental health condition is growing[footnote 75]. We have been working to help employers improve mental health in the workplace. This has included contributing to the Government’s plan[footnote 76] to prevent, mitigate and respond to the mental health impacts of the pandemic. In addition, we continue to support employer action to improve mental health at work through the Thriving at Work Leadership Council. This includes promoting the information and advice available via the Mental Health at Work website[footnote 77], which supports employers to manage the mental health of their staff.

109. Access to Work provides practical and financial support. It is designed to help people overcome barriers and cover the extra costs disabled people and people with health conditions can face in work, beyond those covered by reasonable adjustments. This support is illustrated in the case study below. It can include workplace assessments, providing support workers, specialist aids and equipment and travel to work costs.

Case study: Support provided by Access to Work

Deborah experiences light sensitivity, migraine and a number of musculoskeletal health conditions. Using equipment supplied through Access to Work has enabled Deborah to work effectively in an office.

I chose to apply online and this was a simple process to complete. Once received by Access to Work, an Advisor was allocated to myself who then got in touch to discuss my application further and explained the process step by step.

Using equipment supplied through Access to Work has helped tremendously.

I use an ergonomic split keyboard and a roller mouse, these offer me the ability to use my computer without exacerbating the pain in my wrist and hand. I also have forearm supports which clamp to my desk; these enable me to achieve a supported posture and reduce pressure on my wrists. I have an ergonomic chair with lumbar support; having the neck support allows me to lean back and stretch periodically throughout the day.

To enable me to work from home through the Access to Work Blended Offer Scheme, I was provided with an Electric Sit-Stand Desk, enabling me to stand or sit while working.

The combination of using all this specialist equipment ensures that I work in a comfortable position, allowing me to sit or stand as needed.

Deborah started working as a Customer Services Advisor with Manpower at EON in 2018. She is now employed as an Account Manager at EON.

110. We know from Green Paper events that Access to Work can be a lifeline for disabled people and people with health conditions. However, some people have found the application process difficult, and said that support can take too long to be provided. We are committed to making Access to Work a fully digital service that is innovative, visible and provides an improved experience. We are already making digital improvements which will speed up the payment process and reduce the time it takes to provide support.

111. We are working with disabled people, disabled people’s organisations and charities via the Access to Work Stakeholder Forum to develop an Access to Work Passport, which we will be testing during 2021. The passport will support disabled people when transitioning from education, leaving the armed forces or moving into employment for the first time. This will be a document that can be continually updated, setting out the needs of the passport holder to assist understanding by the employer and provide relevant support in the workplace. This will provide greater flexibility and reduce the need for repeated workplace assessments when changing job roles or working on time-limited contracts.

112. To provide greater flexibility for disabled people to decide where they work, we made changes to enable Access to Work support to be provided in more than one location. Recognising that many disabled people may want to take up freelance and contractor work opportunities, we have introduced a new flexible application process. This flexible application process will reduce bureaucracy and remove the need for repeated Access to Work applications when moving between contracts.

113. Disability Confident (DC) aims to help disabled people start, stay and succeed in work. It does this by helping employers to think differently about disability and take action to improve how they recruit and retain disabled employees[footnote 79]. We are continuing to increase the number of employers who are signed up to the Disability Confident scheme. In April 2019, 11,500 employers had signed up. By the end of March 2021 this had increased to more than 20,000. We are working with people to maximise opportunities through communications, newsletters, social media and network groups to encourage employers to take part in Disability Confident and to progress through the scheme. We are also taking steps to improve Disability Confident by making it easier for employers to sign up and provide their information online.

Consultation question

What more could we do to further support employers to improve work opportunities for disabled people through Access to Work and Disability Confident?

Providing more support before the Work Capability Assessment

114. Recent forecasts assume that the pandemic will lead to greater levels of economic inactivity, including health-related inactivity. As a result, 300,000 more people are forecast to claim UC with LCWRA and New Style ESA from 2022/23[footnote 80]. This can be expected to increase the demand for WCAs. However, the pandemic has also brought about a potentially lasting shift towards home working, which may present new opportunities for many disabled people and people with health conditions.

115. We want to tackle the predicted growth in health-related inactivity, because we know that the longer someone is out of work, the greater the risk to their long-term health and wellbeing[footnote 81]. To help reduce the chance of people being out of work in the long term, we want to explore offering earlier back-to-work support. This support would go beyond the existing ‘Health and Work Conversation’ which people take part in before their WCA takes place.

116. Where people have recently fallen out of work because of a health condition or disability, jobcentres could help people to consider appropriate employment opportunities and raise awareness of in-work support. This could involve more support from a person’s work coach, more often and earlier in the claim. This support would be tailored to each person’s needs. This could either be delivered by a work coach alone or with a Disability Employment Advisor. This will be explored further in Chapter 4, where we look at a separate employment and health discussion.

Consultation question

How can we support people who have fallen out of work to identify and consider suitable alternative work before their WCA?

Ensuring Jobcentres Are Welcoming, Engaging and Expert

117. In recent years we have undertaken research to help us understand what may be preventing people from taking up the support we offer. Through this research[footnote 82], and at Green Paper events, some disabled people and people with health conditions reported worrying that taking part in employment support or starting work might affect their benefit claim or lead to a sanction[footnote 83].

118. Through UC, people can start a new job and gradually increase their earnings without having to leave the benefit. This makes it easier for disabled people and people with health conditions to try out work without worrying about seeing a sudden drop in income.

119. In this section, we will look at building trust and engagement through our jobcentres. We will also consider the role of conditionality and the expertise of our staff.

Applying a new approach to conditionality

120. At Green Paper events, we have heard that people are nervous about engaging with employment support. Conditionality is the requirement for a person to do certain activities that will help that person move towards and into work if they are able. These activities are tailored to the person’s capability and circumstances, with requirements varying depending on which group or regime people are placed in. People who are waiting for a WCA may be asked to carry out work search on UC or work preparation on ESA. People who are found to have LCW (known as WRAG on ESA) will only be required to carry out work preparation activities; while people who are found to have LCWRA (Support Group on ESA) will not be asked to carry out any mandatory work-related activities.

121. Where activities are required, completing them is a requirement of receiving financial support. However, we will never apply a sanction where someone shows a good reason for not complying with this requirement. The activities should always be reasonable and should take account of a person’s disability, health condition and other circumstances.

122. Having listened to people’s views, we have rolled out a new approach to conditionality for disabled people and people with health conditions. This applies to:

- People claiming ESA in the WRAG;

- People who are claiming UC who have been found to have LCW or;

- People who are claiming UC or ESA, ahead of their WCA.

123. In September 2019, we started testing whether changing how activities are agreed can improve the relationship between a person and their work coach. The aim of the approach is to enable an honest and open conversation about what a person can do. We want people to feel engaged in their activity, understand why it is worthwhile and carry it out to the best of their ability, so people are more likely to move towards work, and into work, where possible.

124. Work coaches have the option of applying no mandatory requirements if they feel this is appropriate for the person’s individual circumstances, but instead are encouraged to set voluntary steps the person could take to move towards or into work. These could include, for example, developing a CV or looking for suitable jobs online. Using their discretion, work coaches apply mandatory requirements only if and when they are needed.

125. One of the reasons why this approach to conditionality was shown to be effective in testing was because work coaches were able to apply more tailored activities to help people prepare for and progress in work. Work coaches felt they were able to develop a better understanding of how best to support people through the new approach. They were able to make the best use of voluntary activities to stretch and encourage people, while introducing mandatory activities if necessary to ensure people remained engaged with their employment support. This new approach also reduced the risk of sanctions. We have now rolled this approach out nationally, subject to ongoing evaluation. We will continue to refine our approach on the basis of these findings.

Testing new support through Health Model Offices

126. We want to encourage people who are able to take up employment support to do so. We know that people value frequent contact with a trusted individual, who can identify and help people access extra support[footnote 84].

127. In 2019, we introduced Health Model Offices in 11 jobcentres across Great Britain. These aimed to test a wide range of initiatives including:

- Providing more intensive support to disabled people and people with health conditions;

- Adapting the physical environment in the jobcentre to better meet the needs of disabled people and people with health conditions;

- Improving links between jobcentres and health services, including by basing work coaches in GP surgeries and healthcare professionals in jobcentres; and

- Introducing new communication tools such as a map which outlines a person’s route through the benefits system. This helps to reassure people and encourage better communication.

128. The work of one of these Health Model Offices is highlighted in the case study below.

Case study: Leeds Eastgate jobcentre is one of the Health Model Offices which tested innovative tools and flexible approaches

- Meeting people in an environment where they feel more comfortable – this can involve meeting people in a private room in the jobcentre where it is quieter or in alternative locations to jobcentres such as in community hubs. A disabled person who had appointments with a work coach at the Headingley Community Hub in Leeds said: ‘It’s great to be seen in a relaxing, supporting environment with my work coach. I feel like a person not a number. I feel part of the process and that things are not just being done to me.’

- A Wellness Star –This tool was used to support conversations between work coaches and individuals on a range of areas such as their lifestyle, condition and aspirations for moving towards work. The tool helps measure progress towards goals and identify support needs. The aim is to encourage open and honest conversations and highlight areas where people need support.

- Flexibility – work coaches were given flexibility over the length of time they could spend with people. This helped work coaches build relationships. One work coach said “it means that we have time to build trust. We can explain how we can help and support individuals – it isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach.”