Occupational Health: Working Better

Updated 24 November 2023

Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions and Secretary of State for Health and Social Care by Command of His Majesty

July 2023

CP 880

This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3.

Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned.

This publication is available at GOV.UK.

Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at oh.consultation@dwp.gov.uk

ISBN 978-1-5286-4342-8

E02943964 07/23

Ministerial Foreword

Good work is good for health and good health is good for work.[footnote 1],[footnote 2] Together they deliver real benefits for individuals, businesses, communities, and the wider economy. The Government is committed to generating long-term prosperity and economic growth for all by supporting businesses to grow; ensuring our labour market remains strong and resilient and supporting individuals, particularly disabled people and those with health conditions, with the work and health enablers they need to start, stay and succeed in employment.

At the Spring Budget 2023, the Government introduced an ambitious and wide-ranging package of new measures worth over £2 billion[footnote 3] to support people living with health conditions to succeed in work. Building on a substantial existing package, this will provide a strong foundation to ensure everyone in our country that wants to work is enabled to do so. However, there is still more we can do.

Long-term sickness is now the main reason people of working-age give for being economically inactive (the proportion of people who are neither working nor looking for work). Expert-led impartial advice, and interventions such as occupational health (OH) can help employers provide work-based support to manage their employees’ health conditions.[footnote 4] This, in turn, not only leads to better retention and return to work prospects, but also improves business productivity, which can be adversely impacted by sickness absence.[footnote 5] OH services help to keep employees healthy and safe whilst in work and to manage risks in the workplace that could give rise to work-related ill-health.

Many employers already invest in the health and wellbeing of their workforce and are reaping the benefits, yet there are still marked differences in employers’ abilities and capacity to act. Only 45% of workers in Great Britain have access to OH services,[footnote 6] which is significantly lower than some international comparators. 92% of large employers provide some form of OH for their staff, compared to 18% of small employers.[footnote 7] A radical shift is needed to improve access and uptake of OH services by employers. This will require diversification of the OH workforce and service models, and work with the private sector to develop a longer-term sustainable, multidisciplinary workforce pipeline that can deliver services for businesses of all sizes, and for employees with a range of needs.

This consultation proposes a range of measures to increase OH take-up and address OH workforce capacity, to ensure sufficient services and support are available to those who need them. By bringing together our businesses, the healthcare sector, and local communities, we can achieve this bold vision for the future. A future where an enabling workplace culture is supported by strong OH market provision, and a skilled multidisciplinary OH workforce that uses effective evidence-based strategies to enable people to live healthier and wealthier working lives. This will support the success and prosperity of businesses across our country, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

Executive Summary

Although unemployment is low by historic standards, labour market participation has become a major challenge for the UK. To help stem the flow into economic inactivity, two elements remain essential: work-focused interventions in the healthcare system and accommodating workplaces. The role of employers is critical in helping to identify and remove obstacles to staying in and returning to work.

This consultation focuses on the role of the Government, OH providers and employers, in increasing OH coverage across the UK, within the broader context of enabling better workplace support to improve productivity and prevent ill-health related job loss.

Employers and workplaces are key enablers for retaining disabled people and those with health conditions in work.[footnote 8] OH as advisory support has a broad remit. It plays an important role in supporting employers to maintain and promote employee health and wellbeing through assessments of fitness for work, advice about reasonable adjustments, work ability or return to work plans, and signposting to treatment for specific conditions. Employers have a choice about the type and level of OH service to provide for their employees. However, with only 45% of workers in Great Britain having access,[footnote 9] OH is still not being utilised to its full potential, and some businesses, particularly SMEs, are also sceptical about the business case for the quality and impact of OH.[footnote 10]

To better support businesses, the Government intends through this consultation, to establish agreement and partnership between Government, employers and OH providers, where Government develops clear evidence-based expectations and the underpinning support to enable greater OH take-up, and businesses take bolder steps to support employee health in the workplace. This means that we need to be clear about what OH is and outline a simple and clear baseline for the provision of quality OH as part of a wider ‘health at work standard’ that businesses of all sizes can easily draw on. We also need to explore the evidence base underpinning the steps which countries such as France, Finland, the Netherlands, and Japan have taken to increase their OH coverage, and to learn the most applicable lessons to help drive increased OH take-up amongst employers and in the longer-term, the development of a more multi-disciplinary OH workforce. In some cases, OH may also enable access to treatment, including digital therapeutics that can support self-management, which is an intervention that employers may choose to pay for privately. Whilst this is outside of the scope of this consultation, it highlights the far-reaching benefits of employers’ actions in using OH as a tool for supporting a healthy workforce, enabling self-management of conditions, preventing ill-health related job loss and promoting better work and health outcomes.

Chapter One sets out voluntary proposals, including a national health at work standard for employers, embedding a baseline for quality OH provision, and best-practice sharing, to help provide a simple and clear baseline for quality OH provision to all employers.

It is recognised that different measures may suit the needs of different businesses and that further action is needed to address access, cost, and perception barriers, particularly for SMEs. Government would particularly welcome views from both SMEs and larger firms ahead of taking future decisions.

The proposals set out in this chapter therefore focus on providing greater support to employers to take-up OH. This includes a combination of new guidance on a national health at work standard, embedding a baseline for quality OH provision, offering accreditation levels, Government-funded provision to enable employers to meet the accreditation, and best practice sharing, particularly to support SMEs. Views are sought on the factors linked to outlining a simple and clear baseline for quality OH provision as part of a wider national health standard and the most effective combination of support for employers. Views are also sought on best practice sharing, as outlined above.

Chapter Two examines steps taken by other countries to increase coverage of OH, lessons from successful UK-based employer models to improve support for their employees and potential measures that could apply in the UK.

It is clear from international examples that those countries that have legislated to make the provision of OH a legal requirement have over 75% coverage[footnote 11] (see Annex B). The Government acknowledges that taking steps to accelerate action towards more comprehensive coverage will require substantial action by both the Government and employers. A direct lever (as deployed in other countries) would be to create a legislative framework that sets clear requirements for employers. However, this must be with a view that recognises any such approach must not affect SMEs disproportionately, given 99.2% of private sector businesses at the start of 2022 were small businesses with 0-49 employees[footnote 12].

There are also lessons that we can draw from successful UK policy mechanisms that have delivered large scale systems change (backed by legislation), with employers playing a central role – primarily Automatic Enrolment.

The comparisons set out in this chapter seek to inform solutions to the low OH take-up amongst employers across the UK. Views are sought on how these lessons might be applied in a UK context. Views are also sought on the applicability of lessons from UK-based employer models, where a combination of systems and legal change has enabled larger scale coverage of support for employees.

Chapter Three sets out proposals to develop the existing OH workforce capacity and develop a longer-term sustainable multidisciplinary OH workforce in partnership with the private sector.

To achieve the scale of ambition set out in this consultation, both the workforce and delivery models will need to evolve to meet increased demand. Previous consultations have shown that there is support for the development of a more multidisciplinary model of work and health provision, including expert-led OH, and work on a smaller scale has been taking place. Further work is now needed to build a more multidisciplinary OH workforce model, drawing on both clinical, and wider health and non-clinical professionals.

The proposals set out in this chapter focus on boosting recruitment in this sector, through promotion and pipeline development. Views are sought on identifying new models of care, the range and balance of clinical and non-clinical professionals needed, and appropriate pathways for them to play a role in this profession in future. Views are also sought on optimising additional workforce capacity on work and health conversations through fit notes and a greater role for private providers of OH services in building the workforce.

Introduction

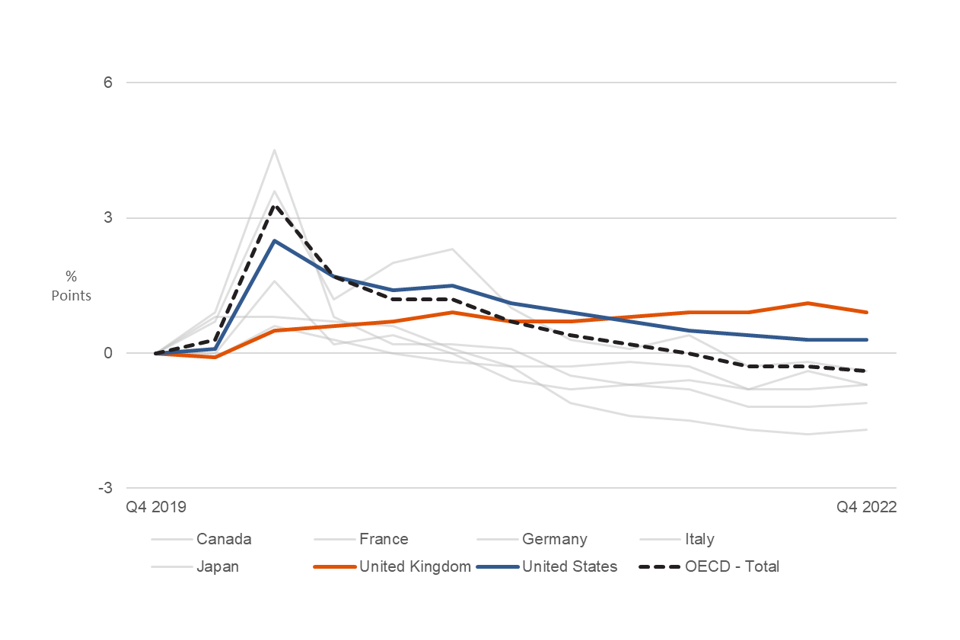

1. The UK has a relatively low economic inactivity rate compared to the rest of the OECD[footnote 13]. However, long-term trends of falling economic inactivity in the UK were reversed during the pandemic. Unlike most comparable countries (and despite falling recently), economic inactivity in the UK has yet to return to pre-COVID levels.[footnote 14] This contrasts with many other OECD countries, who saw sharp rises in inactivity at the start of the pandemic followed by swift returns to pre-pandemic levels.

Fig 1. Percentage point change in economic inactivity rate since Q4 2019, G7 nations and OECD average, 16 to 64[footnote 15]

2. In the UK, long-term sickness is now the most common reason given by working-age people for economic inactivity. Figures from February to April 2023 show that the proportion of people who are economically inactive mainly due to long-term sickness is now up 6.3 percentage points (or 580,000 people) over the latest four years, to 2.55 million.[footnote 16] Between 2014 and 2021, an average of 163,000 employees flowed out of work into health-related inactivity annually (either temporary sick or long-term sick).[footnote 17] Prolonged absences from work can lead to poorer health and increasingly complex barriers to returning,[footnote 18],[footnote 19] so once people become inactive due to long-term sickness, they tend to remain inactive for a long period.

3. Musculoskeletal (MSK) and mental health conditions are the two biggest drivers of economic inactivity when looking at main or secondary conditions.[footnote 20]

4. Furthermore, health-related job losses are often preceded by sickness absences from work. The number of working days lost because of sickness or injury was around 186 million working days in 2022, a new record high.[footnote 21] This represents an increase of around 36 million from 2021 and around 47 million more than its pre-pandemic 2019 level. The longer a sickness absence lasts, the less likely an individual is to return to work, demonstrating the need to minimise the length of sickness absence.[footnote 22]

5. Overall, for disabled workers and workers with health conditions, barriers to staying in work are varied, complex, and multi-faceted. Many have long-term health conditions (lasting longer than 12 months) and co-morbidities. There is little evidence that purely clinical interventions can improve work outcomes.[footnote 23],[footnote 24] This is because the reasons for sickness absence and health-related job loss are often not only biological, but also related to psychological and social/environmental factors.[footnote 25],[footnote 26],[footnote 27],[footnote 28] For example, this can include beliefs that someone cannot work unless fully recovered, lack of motivation or coping skills, physical workplace barriers, unsuitable job roles, or stigma from colleagues.

6. As reviewed thoroughly in the Health is Everyone’s Business (HiEB) consultation,[footnote 29] there is growing evidence and consensus about the key elements of workplace support, and best practice required to support employees with health conditions to remain in work and to reduce ill-health-related job loss. This includes early and sustained workplace support for employees with health conditions, workplace adjustments and work modifications, as well as financial and employment protections.

7. OH advice is a critical enabler for employers to identify and implement evidence-based workplace support. It can help to reduce work-related illness, avoidable sickness absence, and movements out of work into ill health-related inactivity. OH has a broad remit and this consultation uses the same definition as that used in the HiEB consultation:[footnote 30]

Occupational health (OH) is advisory support which helps to maintain and promote employee health and wellbeing. OH services provide direct support and advice to employers and managers, as well as support at an organisational level; (for example, on how to improve work environments and cultures). The services delivered by OH providers traditionally focused on ensuring employers were compliant with health and safety regulations. For example, some OH providers offer health surveillance services, which is a system of ongoing health checks required by law for some employees who undertake or are exposed to certain activities or substances hazardous to health. These services also help with general health risk management in workplaces. As the UK economy has moved towards more service-led industries, OH providers have widened their offer to meet the new challenges facing employers and the workforce today.

8. Services commonly offered are:[footnote 31]

- assessments of fitness for work for ill or sick employees

- advice about workplace modifications or reasonable adjustments

- advice to support development of return-to-work plans

- signposting to, and in some cases providing, services that treat specific conditions, such as physiotherapy

- health promotion schemes

9. Internationally, a number of countries such as France, Finland and the Netherlands have invested in increasing OH coverage. The value placed on OH is clear in these examples as OH access is enforced by law, with particular emphasis on management and prevention. This covers steps taken by employers to prevent health problems at work, unnecessary sickness absence, presenteeism (being present at work but unproductive) and ill-health-related job loss. Return to work support is usually a distinct element of these employer obligations, including return to work plans and adjustments.[footnote 32]

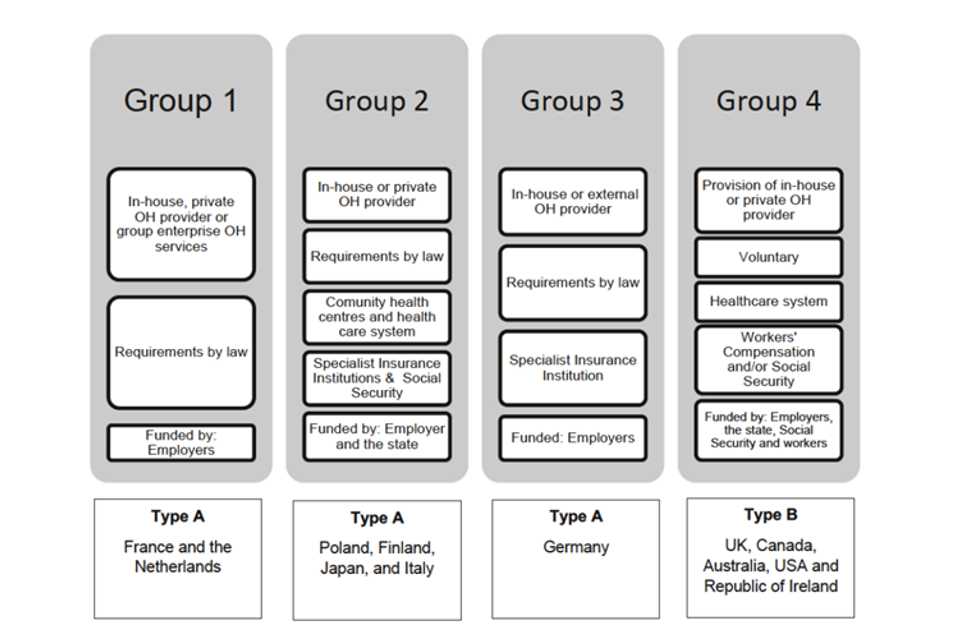

10. In a review of 12 national OH systems, OH coverage varied from 30% to more than 90%, with higher coverage (over 75%) generally in countries where legislation requires employers to provide some form of OH (Germany, Poland, France, Finland, Japan, Netherlands, and Italy). Across the reviewed countries where there was no legal requirement, coverage was less than 50% (UK, Australia, Canada, Ireland, and USA).[footnote 33]

11. UK and international evidence indicates that OH interventions may have the potential to generate economic and social benefits to:[footnote 34]

- individuals, through better work and health outcomes

- employers, through higher productivity, lower sickness absence costs, and lower recruitment costs

- communities and wider society, through higher economic output and better population health

- the Government exchequer, through higher tax receipts, lower spend on disability benefits, and lower NHS spend

12. At the start of 2022, there were 5.5 million private sector businesses in the UK. 5.47 million were small (0 to 49 employees), 35,900 businesses were medium-sized (50 to 249 employees), and 7,700 businesses were large (250 or more employees). 1.4 million of these had employees and 4.1 million had no employees.[footnote 35] There are substantial differences in access to OH in relation to employer size and therefore this context is important when considering how to improve coverage for employees.

13. For employers, there is a business, legal, and moral case for investing in OH.[footnote 36] From a business point of view, it has been estimated that, on average, preventing a single job loss can save employers £8,000 in recruitment costs and business output.[footnote 37] Additionally, investing in the provision of OH services increases organisational performance.[footnote 38] It has been estimated that poor mental health costs UK employers approximately £56 billion a year because of sickness absence, presenteeism, and increased staff turnover – a cost which has increased by about 25% since 2020.[footnote 39] OH services can help employers to comply with legal and regulatory obligations, such as employment law and health and safety regulations. Employers also use OH because they believe they have a moral responsibility to support and improve employee health and wellbeing.[footnote 40]

14. For Government, having one extra disabled person in full-time work, rather than being out of work and fully reliant on benefits, would mean the Government could save an estimated £18,000 a year.[footnote 41] It could give societal savings of £28,000 a year when considering increases in output, reductions in healthcare costs and increased travel. The societal savings could increase to £34,000 a year if including Quality Adjusted Life Year (QALY) impacts, or £36,000 a year if including subjective wellbeing impacts. For a disabled person working part-time, the equivalent figures could be a saving to the Government of £8,000 a year, and a societal saving of £15,000 a year, rising to £19,000 a year if including QALY impacts, or £20,000 a year if including subjective wellbeing impacts.[footnote 42] See Annex A for further details.

15. Ill-health that prevents working age people from working is estimated to cost the whole UK economy around £150 billion per year, equivalent to 7% of GDP.[footnote 43] This includes costs related to lost production due to worklessness, sickness absence, and informal care.

16. Since the HiEB response was published in July 2021, good progress has also been made in identifying ways to improve OH coverage, with a particular focus on SMEs and the commercial market. This includes:

- a new subsidy scheme to tackle financial barriers to purchasing OH to improve SME access is being developed to address cost barriers. This will include digital market navigation to improve support available to SMEs

- a £1 million innovation fund has been launched that is focused on increasing access to, and capacity in, OH through new models designed for SMEs. This will help stimulate market services beyond larger employers to currently underserved SMEs

- working to support the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) (through which DHSC funds research), who are leading on generating and disseminating evidence to support future policy and practice through employers, OH (private and public) providers, and local and national Government. As part of this work, NIHR has launched new Work and Health Development Awards in 2023 which aim to develop the work and health research community and lead to ambitious programmes of research in this important area

-

establishing a cross-sector Task and Finish Group in partnership with the National School of Occupational Health to address current workforce capacity challenges. In line with Task and Finish Group recommendations, the Occupational Health Workforce Expansion Scheme will be launched imminently, providing funding for registered Doctors and Nurses to undertake OH courses and qualifications to support new OH professionals to enter the sector

- further details on the progress since HiEB can be found in Annex D

17. To move beyond market support to improve availability and further drive greater take-up of OH amongst employers, with the aim of preventing ill-health-related job loss, the Government is now consulting on the:

-

introduction of voluntary measures, including a national health at work standard for employers, embedding a baseline for quality OH provision, accreditation, and best-practice sharing, to help provide a simple and clear baseline for quality OH provision to all employees

-

addressing the low take-up of OH provision amongst employers across the UK through examining the steps taken internationally to increase OH coverage and considering lessons from successful UK-based employer models to improve their support for employees, and

-

work to develop OH workforce capacity to support the sector to rapidly build a sustainable, multidisciplinary workforce that can meet increased demand for OH services. This will help align activities with longer term workforce developments across the health and care systems

18. The Government in tandem is also consulting on whether there is a case for tax incentives to help incentivise employers to provide OH services to their employees. As a part of establishing agreement and partnership between the actions of Government, businesses and OH providers, we intend for this consultation to be read alongside the HMT and HMRC consultation Tax Incentives for Occupational Health.

19. In addition to the consultation, the Government has also commissioned IFF Research to conduct research with OH providers, to understand more about the OH market. This will include a telephone survey of OH Providers which will run from July to September 2023. We strongly recommend OH Providers to engage in both the survey and the wider consultation to help create a picture of current provision in the UK and to shape the UK Government sector. For more information, and to take part, please contact OHProviderSurvey@iffresearch.com

Chapter One: Opportunities for greater employer action, best-practice sharing and voluntary health at work standards

Introduction

20. Supporting the health of their workforce should be a key part of the overall work offer for all employers. Many employers provide good health and support measures within the workplace, including robust line management support to enable beneficial conversations about health and wellbeing.[footnote 44] To improve support for employers, progress has been made to simplify the information available, but more can be done to ensure employers have the knowledge and capacity to act, especially SMEs.

21. Research with employers who use OH found little evidence of them exploring the market for the best providers, suggesting that many do not know what a good OH service looks like.[footnote 45] Further, larger employers are five times more likely to provide OH to their employees than smaller employers and SMEs face greater barriers to accessing OH.[footnote 46] These are exacerbated by high search costs, as SME employers find navigating the health and wellbeing market difficult, particularly those without HR departments.[footnote 47] Therefore, we need to ensure good quality information and support is available for SMEs to secure the right level of OH support for their businesses. A strong start was made with HEiB and there is more that we can achieve together.

22. The Government is therefore seeking views on the following proposals and how these can enable businesses to do more to promote better health support at work and increase the take-up of OH provision:

-

views from employers on best practice models to promote better health support in the workplace, and how these can be best shared across larger employers and SMEs

-

consolidating guidance on workplace health provision for employers including defining a simple and clear baseline for quality OH provision for all employers, particularly SMEs

-

a new voluntary national health at work standard for employers, embedding a baseline for quality OH provision, including a simple and clear baseline for quality OH provision, for employers to accredit to

-

if national health at work standard for employers, embedding a baseline for quality OH provision, is developed, providing additional Government-funded support to enable businesses to work towards that standard

Sharing best practice, developing new guidance and defining a simple and clear baseline for quality OH provision

23. In 2013, the Government began a communications campaign with the launch of Disability Confident to challenge negative attitudes and improve employment opportunities for disabled people. In 2016, the Disability Confident scheme began, in its current multi-level form began, developed by disabled people, employers and disability organisations representing disabled people, based on the social model of disability. The Government intends that the Disability Confident Scheme remains credible, sufficiently challenging and continues to support the employment of disabled people. Work will continue with stakeholders to develop and grow the scheme to increase the number of inclusive employers in the UK.

24. Since the Government’s response to the HiEB consultation, positive steps have been taken to develop better information and advice on workplace health and disability provisions. The Government is developing a national (Great Britain wide) digital service for employers (focussed on the needs of smaller businesses) called Support with Employee Health and Disability.[footnote 48] This service is available nationally in live test mode and provides employers with step-by-step guidance, with prompts to take the right action at the right time. It provides information on legal obligations and signposts to sources of expert support, including OH.

25. The Health and Safety Executive (HSE) has also developed new non-statutory principle-based guidance in response to HiEB. This consists of a set of clear and simple principles for employers to support disabled employees and those with long-term health conditions in the workplace. Responses to HSE’s published guidance have been positive.[footnote 49]

26. These recent steps help address the need for more consolidated information for employers on how best to support employee health outcomes, but the landscape remains complex. There is more to do to simplify and consolidate the guidance available, and to showcase the breadth of opportunity to use the workplace to better support employee health outcomes and prevent ill-health related job loss.

27. The Government would particularly like to explore whether there is value in introducing new guidance on health at work standards, that embeds a simple and clear baseline for quality OH provision by employers.

28. OH provision can mean different things for different employers, based on their size, available resources, circumstances and needs. It does not necessarily translate into a need for an employer to offer the full range of interventions that OH covers, which might be more challenging and unnecessary for SMEs. The Government will explore a range of researched views on OH interventions to understand their efficacy and approach for a national OH standard.

29. This includes examining the Denmark model of a tiered approach to minimum levels of OH based on employer size.[footnote 50],[footnote 51] Another example is a work ability plan, which offers to map out individualised support for an employee with health conditions to help return to work from sickness absence. This includes a guided self-assessment of an employee’s work ability (interaction between their health and work), as a starting point and building on this to ensure the employee can thrive in work, managed by a case manager working collaboratively with the employee and their healthcare professional.

30. Baselining quality OH provision could involve:

- commissioning an Expert Advisory Group to develop evidence-based options to help define a simple and clear baseline of quality OH provision proportionate to all sizes and types of businesses, which businesses can follow to improve their workplace health and wellbeing offer to employees; and/or;

- using new guidance and consolidating best practice examples to develop a framework and guiding principles on workplace OH provision for employers; and

- promoting these via Government-funded marketing and communications campaigns

31. This proposal would not require businesses to provide follow up or evidence of activities undertaken to comply with the guidance.

Case study on the positive impact of recently improved guidance

Employer from HSE’s Stage 2 research uses new guidance and reports positive impact:

Chris manages a small gym chain in the recreation sector. The company is currently facing significant workforce challenges, making it crucial to keep experienced staff at work - including supporting through physical and mental health issues.

One of Chris’s staff, a personal trainer, has recently had a hip replacement to address a hip problem which developed over the last two years and had resulted in high frequency of sickness absences.

Support and guidance currently being used:

Chris’s approach has been to support as much as possible to retain this highly skilled and trusted staff member,

My approach was communication, support, discussions at every stage.

However, the lack of clear knowledge and guidance specific to hip problems in the workplace, and the employee’s understanding of their developing condition presented challenges for Chris.

Chris’s company hires a specialist HR consultancy focused on ensuring legal compliance.

Role and impact of the new HSE guidance:

Chris’s HR adviser shared the new published guidance which he is using to inform his future actions, adding a positive impact. It has given Chris confidence about process and a framework on how to talk about work impacting his employee’s specific health condition and how this can be managed at work via guidance on reasonable adjustments that could help to address one of his key priorities around retention of his employee, such as a longer period of time off for surgery, recovery and a phased return to work.

Your views

Q1. What would you consider to be a robust and reliable source of evidence to establish a simple and clear baseline for quality OH provision?

- Evidence based outcomes from an Expert Advisory Group.

- The Government guidance to support employee health outcomes in the workplace, including specifying a clear and simple baseline for minimum levels of OH support.

- Anything else? Give reasons for your views.

Q2. What best practice examples have you seen where workplaces are used to better support employee health outcomes that could be used instead to bolster greater take-up of OH provision? What kind of model would you prefer for sharing this good practice, particularly to support SMEs?

Q3. What benefits does, or could, access to OH services bring to your organisation?

Q4. Are there particular benefits these measures could bring for people with protected characteristics? In what ways could this be achieved?

Q5. What are, or could be, the costs of accessing OH services for your organisation?

Introducing a national voluntary standard and accreditation scheme on work and health embedding a baseline for quality OH provision

32. Kitemarking (a voluntary tool) is used across the healthcare sector to standardise delivery of services. In this chapter, voluntary standards and accreditation are explored as a tool for developing a simple and clear baseline for the level of OH provision that is offered by employers. This chapter is not exploring kitemarking of the quality of OH provision itself. The Safe Effective Quality Occupational Health Service (SEQOHS) offers an industry standard for providers of OH services.

33. The Government would like to explore the value of consolidating existing best practice and introducing new guidance to develop a Government-endorsed, evidence-based accreditation scheme on workplace health and disability which employers could adopt. This could include a national health at work standard for employers, embedding a baseline for quality OH provision, and how to achieve it.

34. Developing such a scheme would likely increase awareness of best practice and build employer confidence, particularly for SMEs. This would likely enable businesses to better promote and support the health of their employees but also increase employee engagement with a clearer overall support offer. This could be beneficial for recruiting new talent.

35. We would explore options for how this accreditation scheme could serve as a comprehensive resource for employers on workplace health and disability, to minimise the number of places where employers need to go for guidance in this area. We would need to carefully consider how this would relate to existing information services, such as Disability Confident and the Support with Employee Health and Disability Service.

36. An accreditation scheme for employers could have a number of benefits including:

- a national tiered (likely based on business size) set of provisions that an employer could put in place, including on OH, which would help employers of all sizes improve their knowledge of how to better manage health and disability in the workplace and prevent ill-health related job loss

- employers being able to advertise that they had committed to maintaining a certain standard on workplace health and disability, including OH, which could help them attract and retain talent in a competitive labour market

- employees having a greater understanding of how their employer will support them, particularly if they have a disability or long-term health condition. This would increase their psychological safety and wellbeing at work as well as their ability to seek support when required and therefore potentially stay in work when they might otherwise fall out of it

37. There are potential drawbacks to the Government developing such a standard, including:

- the risk of duplicating existing frameworks and standards, and confusing employers about which standards they should adopt

- lack of employer capacity to effectively implement the new standard because the landscape of existing frameworks and regulations that employers either have to or choose to abide by is sufficiently demanding

- lack of credibility in the standard if not developed in an appropriately robust way. For example, if the evidence base is inadequate or the standard does not contain measures to assure employer compliance such as spot checks and

- the standard not being attractive enough for employers to take it up, leading to poor value for public money

38. In developing this scheme, we would examine similar offerings in countries around the world to learn from international comparators. For example, Singapore operates an initiative called the Tripartite Alliance for Fair and Progressive Employment Practices (TAFPEP), which provides resources for employers and employees on workplace management (including on health and disability issues). Australia has developed a Mentally Healthy Workplaces platform to provide quality-assured advice in one place. Learning from international experience would be a key part of our policy development.

39. A scheme would need some form of flexibility to allow for the different needs and abilities of employers. For example, it could be tiered to meet the needs of different sized businesses, as some measures may not be suitable for SMEs but would be suitable for larger businesses. Alternatively, the tiers of the scheme could be based on ‘minimum’ versus ‘excellent’ quality of OH provision for those employers seeking market leading provision, giving a range of options for all employers. There are examples of voluntary standard accreditation schemes in different regions, including Thrive at Work, across the East and West Midlands, and Mind’s Mental Health at Work Commitment (see case studies below).

Case Study

The Mental Health at Work (MHAW) Commitment is a free framework curated by Mind and the Mental Health at Work Leadership Council. It was developed from the six core standards from the Thriving at Work: the Stevenson/Farmer review on mental health and employers as well as other mental health standards. The MHAW Commitment is based on standards which are to:

- Prioritise mental health in the workplace by developing and delivering a systematic programme of activity

- Proactively ensure work design and organisational culture drive positive mental health outcomes

- Promote an open culture around mental health

- Increase organisational confidence and capacity

- Provide mental health tools and support; and

- Increase transparency and accountably through internal and external reporting

The framework sets out actions that an organisation can follow to improve and support the mental health of their employees. The Government have supported an evaluation of the MHAW website and commitment through the Midland’s Mental Health and Productivity Pilot. The final evaluation will be available by April 2024.

Case Study

Thrive at Work is an accreditation programme that enables employers to sign up to a workplace commitment with criteria and guidelines on creating a workplace that promotes employee health and wellbeing, focusing on key organisational enablers of health (policies and procedures such as attendance management) in addition to thematic health areas (e.g. mental health, musculoskeletal health and promoting healthy lifestyles).

Employers that gain accreditation to Thrive at Work are recognised among an esteemed network of organisations committed to excellence in employee health and wellbeing.

Thrive at Work is funded through the Mental Health and Productivity Pilot and is free to organisations across the East and West Midlands region. It is open to organisations of any sector and is suitable for those organisations of more than 8 employees.

There are four levels of accreditation covering different health and wellbeing themes. Organisations start by working towards Foundation level and can then progress on to bronze, silver and gold levels, working at their own pace to implement the criteria required to achieve each level. Organisations that achieve accreditation are set apart as an ‘employer of choice’ when it comes to health and wellbeing.

Your views

Q6. a) What should such a national health at work standard for employers, embedding a baseline for quality OH provision, include, especially given the requirement to accommodate different employer needs?

b) What should the OH elements of that standard look like, particularly to ensure a simple and clear baseline for quality OH provision?

Q7. For an accreditation scheme, should the levels or tiers be based on business size and turnover? What other factors should we consider for the tiers? What incentives should be included in the higher tiers?

Q8. [To be answered if you are an SME or if you represent SMEs]

As an SME with fewer than 250 employees or as a SME representative,

a) how useful and/or practical would such an accreditation scheme be for you? Give reasons.

b) how useful and/or practical would benefits such as access to peer support be?

Q9. How should such an accreditation scheme be monitored and assessed? What assessment or evidence should employers need to provide to achieve each level?

Providing additional Government-funded support to enable businesses to adhere to guidance

40. The Government could consider additional funded support for those seeking to accredit themselves to the proposed national health at work standard, including for providing baselined quality OH. This could build on the promising indications from an existing Government approach in the Midlands, the Mental Health and Productivity Pilot (MHPP), where employers are supported with both frameworks of guidance and support services to help them implement the guidance. The MHPP is primarily focused on mental health, but the Government would look to tackle both mental and physical ill-health.

41. Based on promising initial findings from the Midlands pilots, the support offer to employers seeking to adopt the standard could include:

- outreach workers to support employers by tailoring the package to their needs and facilitating peer-to-peer learning

- a package of evidence-based resources for managing health and disability in the workplace

- opportunities for businesses to network and to mentor each other (perhaps through local Chambers of Commerce) to share ideas on best practice and to explore collective approaches to meeting the standards with other businesses of the same size or in the same sector; and

- bespoke support options tailored to different employer sizes and the sectoral mix in different regions, to complement a national standard and resource offer developed by DWP/DHSC

Your views

Q10. What Government support services would be most valuable for employers seeking to improve their support for health and disability in the workplace, including as they work by towards a baselined quality OH provision as set out in a national health at work standard for employers, embedding a baseline for quality OH provision, that the Government would develop?

Q11. Should access to a Government-funded support package be conditional on accrediting to the proposed national health at work standard for employers, embedding a baseline for quality OH provision? Give reasons for your views.

Chapter Two: Lessons from international comparators and successful UK-based employer models to drive OH take-up

The matters raised in this chapter relate to employment. Employment is a reserved matter in relation to Scotland and Wales and so this chapter relates to the entirety of Great Britain.

Introduction

42. Whilst there is evidence on the benefits of OH in terms of helping to support earlier returns from sickness absence and preventing job loss, there is scope to strengthen the evidence. Employers need a better understanding of how they can maximise outcomes through the use of OH services.[footnote 52]

43. Lessons could be learned from international comparators that have taken more radical steps to achieve more than 75% OH coverage, and consider these in the UK context, including considering organisational size. We must also consider factors underpinning the success of UK-based policy mechanisms, to bring about change amongst employers and greater take-up of different provisions by employees.

44. We must recognise that any Government-led policy to prompt systems change needs to balance an expectation of self-sufficiency from our larger world-leading organisations with suitable complementary support for SMEs (as outlined in Chapter One) to enable their continued growth, as well as exploring the case for financial incentives through the HMT and HMRC consultation Tax Incentives for Occupational Health.

45. This chapter therefore starts by examining the steps taken by other countries to increase OH coverage and the available evidence and rationale underpinning the approach, which has often been iterated over several years.[footnote 53] The evidence allows for some comparison between the UK and the countries in question, their healthcare systems, modes of delivering OH services, and legal landscape. It also identifies where size has influenced a greater role. Further, the chapter considers lessons from policy mechanisms in the UK that have delivered large scale systems change (backed by legal requirements), with employers playing a central role – primarily Automatic Enrolment.

46. The Government would like to gather views on whether more direct policy levers, including employer models to drive systems change, would be the best way to increase use of appropriate OH services, in addition to the voluntary measures set out in Chapter One.

Lessons from International Comparators[footnote 54]

47. Internationally there are two main legislative approaches to OH access. Those countries categorised as type A in this comparison all have higher rates of access than the UK, which is categorised as type B:

A. OH legislation is enshrined in a single act with focus on an integrated, multidisciplinary service, stipulating rights and roles of employers and employees; and

B. OH legislation is spread across social security, health and safety, and labour laws. Delivery of OH provision is typically (but not always) more open for interpretation.

Occupational Health Coverage in Selected Countries

| Country | Estimation of Coverage | Legal Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Poland | ~100% | Type A |

| Germany | High | Type A |

| France | 90+% | Type A |

| Finland | 90% | Type A |

| Japan | 85% | Type A |

| Netherlands | 80% | Type A |

| Italy | 75% | Type A |

| UK | 51% | Type B |

| Australia | 50% | Type B |

| Canada | 48% | Type B |

| Republic of Ireland | 30-40% | Type B |

| USA | 35% | Type B |

48. The organisation and financing of OH services varies between countries based on national tradition, healthcare systems, legal context, social security system, and economic structure. The services included often cover steps taken by employers to prevent health problems at work (as set out in paragraph 9) with return to work support often forming a distinct element of these employer obligations. To meet the OH needs of employers a number of different models of OH services are commonly used. These include:

- in-house provision where OH is organised and funded by the employer

- private provision where outsourced OH operates externally from the employer

- group service models where OH services are shared and jointly funded by multiple companies

- community-based healthcare where OH services are provided by regional health service units

- workers compensation, which is organised via state-run authorities and funded through employer levies; and

- state provision where OH services are provided through state-run programmes

49. In the UK, OH services are primarily funded by employers, and delivered by in-house or private provision. Of the employers that use OH, in-house OH teams are used by one in eight (12%), particularly by larger employers (17%) and by those working in highly specialised environments.[footnote 55] Some experts have pointed to a shift and decline in usage of in-house OH, and the subsequent impacts on the OH workforce.[footnote 56] It is important to note that a number of international models target specific employer size and employee groups for provision. Proposals to increase access in the UK should consider this option for rebalancing expectations of employer self-sufficiency versus receiving Government support.

Case Study: Netherlands

Employers are legally mandated to provide OH under the Working Conditions Act (1994). The two key mandates are:

- Employers with 50+ employees must have a ‘Work Council’, where employers and employees jointly agree on the company’s policies on health and safety and sickness absence. Small employers must directly consult with employees.

- During sickness absences, the ‘Gatekeeper’ protocol mandates tasks for employers, employees, and OH physicians, focusing on return to work. The employer must refer sick employees to an OH physician for periodic OH assessments (assessing ability to work and providing advice about returns to work). The employer must draft an action plan and is expected to do the utmost to provide the employee with suitable work (e.g. work accommodations). If no suitable work is available in the company, it can be expected that the employer funds the employee to seek employment elsewhere for up to two years.

Case Study: Japan

- All employers of >50 people are legally mandated to appoint an OH physician.

- Among smaller sized employers (50-999 people), a part-time Occupational Physician must be contracted, but can be shared across employers. Note that small-sized employers comprise 97% of all workplaces in Japan.

- Emphasis in legislation on primary prevention - Total Health Promotion Plan.

- All workplaces, regardless of size, are mandated to provide health examinations for their workers. These include pre-employment and periodic general health examinations for full-time workers, and specific health examinations for full-time workers engaged in activity described as ‘harmful work’.

50. Whilst international comparisons suggest that legal requirements for employers to provide OH can contribute to higher coverage, the evidence on the direct labour market impacts of greater coverage is more complex to identify. Further, maximising the employment outcomes as a result will depend on a range of other factors, influenced by employer culture, capability and capacity. Also, gaining positive impacts from OH is not just about employees having access to OH, but employers then having the willingness and ability to act upon the advice they receive.

51. Survey evidence from 2018-19, found that a majority of employers in Great Britain report that they provide some form of support to prevent employee ill-health or improve the health and well-being of their workforce. The most common form of support provided by three quarters of employers (77%) was health and safety training. Around three in ten provided interventions to prevent common health conditions becoming a problem (29%) and just over a quarter provided line manager training (26%). When asked about the barriers in providing support to employees to return to work, three in five employers who had experienced long-term sickness absence in the last 12 months (60%) cited barriers, with lack of time and resources (41%) and a lack of capital to invest (27%) being among the most common reasons.[footnote 57]

52. Evidence from the Fit for Work assessment service which ran between 2014 and 2018 to help employees stay in or return to work highlights barriers some employers faced when receiving advice from the service. Nearly two in five (39%) employees who received a Return-to-Work Plan reported that all of their recommendations had been enacted, and a further fifth (22%) reported that some had been acted upon. The most common reason employers gave for not implementing recommendations was that they were reported to be impractical, or inappropriate to their work context. Findings also indicated that: adaptations may be harder for smaller organisations; small employers were less likely to agree that recommendations had been helpful than for medium or larger employers; and employees with mental health conditions were less likely to report that all recommendations had been acted upon.[footnote 58]

Considering lessons from international comparators in a UK context

53. Any potential changes to drive greater take-up of OH by employers would need to be reasonable and proportionate, not only to retain the flexibility within the UK labour market which has been crucial to its success, but also to recognise the differences in employer capability and the capacity to act. Mirroring the approaches taken by some international comparators does not mean that the same impacts will be achieved in a UK setting, because the UK is not wholly comparable due to differences in factors such as state actors, levers, and health care provision.

54. When comparing the UK with states that have taken a legislative approach to increasing use of OH, it is clear that the Government would need to introduce legislation to enable more direct policy levers. A less direct approach may be appropriate instead, including:

- amending corporate reporting requirements (such as the declarations that company directors are required to make under section 172 of the Companies Act 2006) to compel the relevant companies to make declarations of their provisions to support the health needs of their employees

- introducing ‘indirect’ requirements. For example, this could mean introducing supply chain duties, similar to modern slavery commercial requirements. This could require that investors take account of health and disability provision (as modelled by Churches, Charities and Local Authorities’, or CCLA, Corporate Mental Health Benchmark)

55. OH can be an effective tool for those not categorised as employees or workers (including self-employed people). Regardless of employment status, the rights to safe working environments (Health and Safety at Work Act 1974) and to not be discriminated against based on disability or health condition (Equality Act 2010) apply to all persons. However, increasing employer duties or introducing new employment rights would apply to the employment relationship between employers and their employees, and potentially workers. The Government would need to consider to which categories of employees and workers any new measures should apply.

56. The Government is also exploring what considerations should be made for different workplace situations. For example, it could be the case that it may not be proportionate for smaller businesses to be subject to the same measures on OH provision as larger businesses. Alternatively, there may be specific sectors or categories of employees, such as those classed as workers who have less statutory employment protection, who should be treated differently under these measures.[footnote 59]

57. A tiered system that has more measures or expectations for larger employers could be adopted and has a precedent in several international examples.

Your views

Q12. Drawing on examples from international comparators, what could be effective in driving employer demand to enable a shift towards higher rates of access?

Q13. What are the possible costs/benefits of legal measures to provide OH, and do these vary by the size of the business?

UK models of employer-funded provision for employees

58. There are already a number of support provisions available to help businesses take-up OH in the UK. Employers receive up to £500 tax relief for medical treatments they fund to support the return to work of an ill or injured employee, and the Government’s Access to Work Scheme also provides support for employees where the support to stay in work goes beyond reasonable adjustments.

59. These provisions can help to reduce barriers for SMEs and are also used by larger employers. We must rebalance expectations of our larger business by ensuring we target support to those who need them most, whilst encouraging all our larger organisations to become world leaders in this space. This could include, for example, larger organisations self-reporting on an annual basis and the availability of Government support to those organisations being linked to OH provision being in place.

Case Study

What is Automatic Enrolment (AE)?

By compelling employers to automatically enrol eligible employees into a workplace pension scheme with an employer contribution, AE worked by increasing access to a ‘good’ workplace pension, as well as changing the default for workers so that they had to opt out if they didn’t want to remain enrolled, rather than requiring them to actively opt in.

The Pension Commission in 2006 provided a starting point for more than a decade of reform. The Commission examined the adequacy of UK pension saving, both state and private. It identified areas of challenge and set out solutions which have driven subsequent reform.

People were not saving enough privately to supplement their State Pension in order to have sufficient funds in retirement. AE was introduced to help address that, with a focus on low to moderate earners.

How does it work?

AE works by legally requiring all employers – regardless of size or sector – to assess their workers against a set of criteria (including age and earnings) and to enrol eligible workers into a pension scheme (which is chosen by the employer). Workers have to choose to opt out if they do not want to save. It removes complexity from pensions, as workers do not have to make choices once enrolled by their employer. It is more flexible than compulsion, as it retains choice for people to opt out. In practice, most do not opt out and they continue to save. Employer compliance is overseen by The Pensions Regulator, and employers have to complete a declaration of compliance with their AE duties.

Both employers and the worker make a pension contribution (with associated tax relief). The minimum contribution is a total of 8% of qualifying earnings with a minimum of 3% from the employer. Until 2018 the minimum contribution required under Automatic Enrolment was 2% of qualifying earnings, with a minimum of 1% contributed by the employer. In April 2018, this minimum increased to 5% of qualifying earnings, with a minimum of 2% from the employer. In April 2019 the phased introduction of AE was completed when the minimum contribution increased to 8% of qualifying earnings with a minimum of 3% from the employer.

It has transformed participation in workplace pension saving.[footnote 60]

60. Whilst Automatic Enrolment into a pension scheme operates within a different context to the delivery of OH services, learning could inform a similar approach for increasing employer take-up of OH. For example:

- Employers could be legally required to provide minimum access to OH, as a default for their eligible employees. Employees could however opt-out of their entitlement to access OH and the onus would be on the employer to send a declaration of compliance

- A body would also be required to oversee this scale of change. For example, The Pensions Regulator in the context of supporting the delivery of Automatic Enrolment, are responsible for raising awareness of legislative requirements as well as overseeing reporting and compliance. The Pensions Regulator make sure that employers, trustees, pension specialists, and business advisers can fulfil their duties to scheme members

- Careful consideration would need to be given to SME requirements, allowing them to prepare for the changes, and support services would need to be in place to meet their needs. The National Employment Savings Trust, which is run on a not-for-profit basis, ensures that all employers have access to suitable, low-charge pension provision to meet their new duty to enrol all eligible workers into a workplace pension automatically

- SMEs could also potentially be brought into the compulsory system on a longer timeframe

61. To enable the above approach in the context of OH, the following would need to be in place:

-

new primary legislation to legally require employers to provide a minimum level of OH in specified circumstances, as there is no existing legislation to enable this

-

agreement on what services, circumstances, and employee eligibility criteria should apply. For example, OH assessment following sickness absence

-

identification or creation of a regulatory body and processes to support administration, compliance, and penalties; and

-

sufficient OH capacity to ensure all employers could access when required as outlined in Chapter Three

62. The Government is therefore considering the development of a UK-based employer model encompassing systems change elements that could drive increased OH take-up amongst employers in the longer term and is keen to seek views to help build the evidence base on impact. Responses here will be considered alongside those on the OH workforce set out in the next chapter.

Your views

Q14. What lessons could be learned from self-reporting models and Automatic-Enrolment that could be applied to increase access to OH amongst employers? Please include which elements of these examples could be delivered for OH.

Chapter Three: Developing the work and health workforce capacity, including the expert OH workforce, to build a sustainable model to meet future demand.

Health is a devolved matter in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, so only provide responses to the questions contained within this chapter if:

- You are a resident in England

- Your organisation or company is registered in England; and/or

- Your organisation or company deliver its services in England

We have engaged with the Devolved Administrations (DAs) who are supportive as they have equivalent initiatives and similar issues in relation to workforce. Through ongoing engagement, we intend to share the findings of this consultation and explore opportunities to collaborate with DAs in the future.

Introduction

63. Our healthcare professionals are some of the finest in the world. They work in partnership with non-clinical professionals across both the NHS and the private sector to keep our nation living longer in better health. As people live and work for longer at a time when we also face significant pressures across the health and care workforce, it is right that we consider how we support the increased demand for OH services, as well as other work and health interventions. This needs to balance looking at how services can be delivered differently to increase capacity, options to expand and diversify the current workforce, and longer-term sustainable workforce planning. This must be done in partnership with the private OH market that provides the majority of existing OH services.

64. Work with the OH sector (which includes longstanding work[footnote 61] with OH professions and leaders across the system who champion work and health) has shown there is support for a multidisciplinary approach to the delivery of work and health services.

65. As part of moving to a more multidisciplinary model, there is an opportunity to put a greater recognition and focus on wider health determinants of health. For example, clinical and non-clinical professionals could put more focus on biopsychosocial models of care, which recognise the interconnectedness of biological, psychological and social factors that contribute to a person’s working health. This must be done in a sustainable way that recognises the workforce needed to deliver work and health interventions that can deliver person-centred care and can operate across the commercial and public sectors.

66. The approach to workforce development will consider both existing models of expert clinician-led OH as well as the emergence of innovative new approaches to low intensity work and health support such as that tested by the Manchester Working Well Early Help Programme, and a Society of Occupational Medicine (SOM) led initiative which also involves a pilot ‘join up’ between OH, primary care, and DWP work coaches to reduce worklessness due to ill-health. The forthcoming WorkWell Partnership Programme pilots announced at the Spring Budget 2023 will also look to provide low intensity biopsychosocial interventions with a focus on multidisciplinary teams staffed largely by non-clinical professionals. Investing in a wider workforce and skills mix can also offer potential to support conversations about wider determinants that can impact on both employment and health. For example, using Green Social Prescribing to support both mental health outcomes and employment opportunities.

67. To address the question of sustainable workforce development the Government is therefore seeking views on the following. Please provide responses that consider both the need to develop skills mix with the expert clinically led OH workforce and the wider nonclinical workforce needed to deliver low intensity work and health interventions:

- the role of public and private sector in jointly identifying ways to increase long term recruitment and making OH a more attractive profession

- promotion of the OH profession to help increase recruitment into and leadership of the profession

- developing a multidisciplinary workforce by identifying the appropriate balance of clinical and non-clinical professionals, and mix of healthcare professionals, required to deliver a quality multidisciplinary service

- identifying how SME OH providers are encouraged to invest in this workforce and to use these models

- optimising additional workforce capacity via the fit note certification extension to increase the number of “may be fit for work with adjustment” conversations and work to improve work and health conversations by a wider range of healthcare and non-healthcare professionals

Boosting recruitment and diversifying the pipeline into the OH profession

68. In order to build a sustainable workforce equipped to have work and health conversations there is a need to increase the number of clinical and non-clinical professionals able to undertake work and health conversations in the shorter term. This needs to happen whilst also understanding how to build the pipeline of future professionals in partnership with the private sector to provide long term sustainability and support for people with health conditions and disabilities currently in work and those hoping to return across the UK.

69. The specialist OH market has substantial workforce capacity constraints which risk limiting its ability to meet current and future demand for OH services. There is a declining OH workforce and insufficient entry into the OH sector. Nurses and doctors with OH qualifications are currently the most frequently employed roles by OH providers.[footnote 62]

70. As a result the reduction in people undertaking OH courses and qualifications has led to the average age of OH doctors and OH nurses increasing over time, and many are likely to retire in the next decade. Almost three quarters (74%) of OM-specialist physicians are aged 50+ and over a third (35%) are aged 60+.[footnote 63]

71. More recently, some larger employers have transitioned to a less specialist-centred model, such as drawing on nurses or privately sourced external provision rather than reliance on OH doctors. OH providers may have typically relied on OH specialists who trained under the historic model (i.e. major employers training up OH specialists) but have done so without taking on the training of the next generation of OH specialists. As a result, the pool of OH expertise has been decreasing, with a particularly sharp decline in recent years.[footnote 64]

72. Many countries face similar shortages of occupational physicians and have taken different approaches to address it. For example, in France there was a shift to focus on multidisciplinary models, and in Finland they focused on providing support for occupational health training.

73. To enhance uptake in training opportunities in the OH market, the Government will launch in England the OH Workforce Expansion Scheme delivered via the National School of Occupational Health. The scheme is aimed at registered doctors and nurses to start to address the decline in clinicians through funding c.70 places during 2023/24. Promotion of the scheme will be through registered bodies and organisations with a focus on those who have left the NHS or are planning to leave. This scheme will provide information and evidence on demand to support potential recruitment by the private sector, following the excellent outcome from the NHS Grow Programme.

74. This is an important first step to workforce expansion. However, to address the decline and increase capacity, further actions are required to develop a diverse workforce. To achieve this, we need to take a whole systems approach (that integrates services around the person including health, social care, public health and wider services such as those provided by employers) to understand the skills mix and scale of action required. The responses to this consultation will help shape this thinking, ensuring this work aligns activities with longer term workforce developments across the health and care systems.

75. The existing tendency to use medicalised models of OH delivery means that recruitment into the private OH sector has primarily drawn upon registered doctors and nurses and therefore those working within the NHS. In 2021, there were 1,366 members of the Faculty of Occupational Medicine (FOM; the UK professional and training body for Occupational Medicine) which is less than 0.5% of all UK doctors.[footnote 65],[footnote 66]

76. The NHS in England provides OH services for NHS employees, however it faces similar issues as the private sector around recruitment into OH. To start to address this, the Growing OH and Wellbeing Together strategy has been launched, which included funding for OH courses in 2022/23 to increase the capacity of the NHS OH clinical workforce by taking 29 doctors, 30 nurses and 55 managers through professional development qualifications to enable them to effectively practice in OH.

77. To meet an expanded demand, there is also a need to think creatively about the ways in which people from wider clinical and non-clinical backgrounds can be trained to work in multidisciplinary OH teams to meet the needs of employers and individuals. Identifying the range of professionals such as physiotherapists, occupational therapists and mental health practitioners who might want to work in OH through both undergraduate, graduate and non-graduate routes will be key, including considering the potential for professionals from non-traditional routes to play a role, such as sports science and exercise professionals.

Your views

Q15. What more can be done to build the multidisciplinary clinical and non-clinical workforce equipped with the skills needed to deliver occupational health and wider work and health services? Please include any examples of creative solutions.

Q16. What would professionals find helpful to refer into wider work and health or employment support services?

Building and diversifying the pipeline in the OH profession through promotion of OH as a career

78. There is an opportunity to support retention of clinical professionals in the healthcare workforce, by delivering targeted promotion of OH as a career option for those who have left or are planning to leave the NHS or profession, and to encourage them to stay in the profession. This includes those who may be later in their careers and need flexible hours for responsibilities such as caring.

79. Insight from the OH sector suggests that in comparison to other health specialisms such as primary care, OH lacks promotion at undergraduate level when people opt for an area of healthcare to specialise in. Therefore, promotion of the profession could play an important role in attracting both clinical and non-clinical professionals to work in OH.

80. The UK Government has commissioned Kings College London to conduct audience research with trainee doctors, nurses, OH trainees, and OH career leavers exploring the awareness and attractiveness of OH careers. We will want to consider with the sector how the findings can inform how OH is positioned as an attractive career option.

Your views

Q17. How can we promote OH as an attractive career to encourage a wide range of professionals to join and/or remain in the profession?

Q18. What are the optimum touchpoints to promote careers in OH at entry level e.g., studying different disciplines to those who have left the NHS or are considering a career change?

Developing a multidisciplinary workforce and encouraging SME OH providers to utilise different models

81. With any increased demand, OH providers’ ability to grow their capacity through their investment in the workforce will be key to meeting market needs of businesses and supporting working age people to enter, stay in and return to work. The Government recognises the need to work jointly with the OH commercial market to consider the development of career paths from other disciplines, including across the health and social care sectors, at the point of entry or career change to OH profession. Larger OH providers and in-house OH services are more likely to deliver through multidisciplinary teams and could have the potential to offer apprenticeships and other pathways. The mix and skill set of people differs dependant on the level of skills in their workforce and the requirements of that employment sector.

82. To move over to a more multidisciplinary model of resourcing there are some constraints in the current market - currently 60% of OH providers have under ten employees in their organisation,[footnote 67] which may make it harder to adopt a more multidisciplinary approach. In addition, 78% of surveyed providers felt they already had the “right balance” of medical and non-medical staff, suggesting they are generally not responding to recruitment difficulties by recruiting a more multidisciplinary team.

Your views

Q19. What actions or mechanisms (including technology) can be used to ensure that the multidisciplinary OH workforce will be utilised by service providers in an effective way to respond to an increase in demand for quality expert and low intensity work and health support (OH)?

Q20. How do we encourage and support small and medium sized OH providers to adopt a multidisciplinary approach? What are the key enablers and what opportunities are there to incentivise collaboration within the sector?

Optimising additional workforce capacity via fit note and other mechanisms for health and work conversations

83. As work is a key determinant of health, supporting healthcare professionals to embed health and work conversations into their routine clinical practice can influence health outcomes. There is guidance and e-learning to help upskill-healthcare professionals into having good health and work conversations - Work and Health - elearning for healthcare (e-lfh.org.uk).

84. The Government is currently refreshing the existing guidance available for healthcare professionals, employers and employees as part of recent legislative changes to fit notes. It is exploring ways to better promote the fit note as a means of having a work and health conversation that supports those who are at risk of falling out of employment but who may be fit for, or benefit from remaining in work, to do so.

85. This builds on the Government’s continued commitment to improving the fit note as the main conversational tool on work and health between healthcare professionals and individuals. We are working with the professional medical bodies to implement these changes.

86. From 1 July 2022 the Government changed the regulations to extend certification of fit notes to a wider range of healthcare professions. This means that registered nurses, occupational therapists, physiotherapists and pharmacists, in addition to doctors, can now certify fit notes. We have a programme of work, including both qualitative and quantitative elements, that aims to evaluate the impact of the changes at the end of 2023. It is too early to draw definitive conclusions about the impact of the regulation changes at this stage.

87. This represents a significant step in the longer-term fit note policy journey by drawing on the skills and experience of other healthcare professions working as part of multi-disciplinary teams that can support the fit note to be a more effective tool in sickness absence management.

Your views

Q21. As part of the move to a more multidisciplinary workforce to deliver work and health conversations, should we consider further extension of the professionals who can sign fit notes?

And if yes, which professionals should we consider?

Q22. What further action can the Government take to support multidisciplinary teams to deliver work and health conversations in other settings (for example NHS or community settings), to improve health outcomes and address health disparities?

Annex A: Methodological detail for Exchequer and societal savings from job retention

The Exchequer and Societal savings figures are based on internal analysis. We estimate the costs and benefits of moving example Universal Credit (UC) claimants from unemployment into work on the Claimants, their Employers, the Exchequer and wider Society. The analysis is in line with the HM Treasury Green Book, as well as the Department for Work and Pensions Social Cost-Benefit Analysis Framework.