Public Health England: approach to surveillance

Published 13 December 2017

1. Executive summary

Surveillance is a core function for Public Health England (PHE) and ensures that we have the right information available to us at the right time to inform public health decisions and actions.

The opportunities provided by good quality surveillance are significant, from ensuring we respond quickly and effectively to public health threats to improving interoperability between systems and using new technologies to improve outcomes.

In 2012 we published ‘Towards a Public Health Surveillance Strategy for England’, an overview of the vision, rationale and plans for the delivery of a surveillance strategy for PHE.

Now we need to build on that vision, acknowledging the definition, purpose and role of surveillance and outlining the principles and standards that should underpin all of our current and future surveillance activities.

This document recognises the need for high-quality evidence derived from our surveillance systems and sets out the overarching direction under which strategies can be developed for surveillance of both infectious and non-communicable diseases.

This will allow us to place the role of surveillance securely within the current strategic framework of PHE, and respond to new approaches to how we identify and respond to emerging threats to public health, for example, the rapidly developing use of whole genome sequencing.

Some of these new approaches are detailed in the examples given towards the end of this report. The examples show how we are developing new systems for collecting valuable data that adhere to the common and recognised principles of surveillance and conform to the PHE surveillance standards.

We must ensure that our surveillance systems and activities continue to be fit for purpose; failing to do so will directly hamper our ability to tackle the serious challenges to our health and to the sustainability of our health and social care systems posed by issues such as:

- global warming

- a growing and ageing population with multiple morbidities

- increasing inequalities in wealth and health

- emerging and resistant infectious diseases

One of the recommendations of the Academy of Medical Sciences’ 2016 report, Improving the health of the public by 2040 [footnote 1], was that main public sector, commercial and charitable stakeholders work together ‘to maximise the potential of data generated within and outside the health system, within appropriate ethical and regulatory frameworks, for health of the public research’.

This report provides a framework for how we can work together in innovative ways to collect, link, analyse, visualise and interpret a vast range of data for different purposes, with significant benefits for protecting and improving the public’s health.

2. Background and context

Public health surveillance dates back to the first recorded epidemic in 3180 B.C. in Egypt. Hippocrates (460 B.C.-370 B.C.) coined the terms endemic and epidemic, John Graunt (1620-1674) introduced systematic data analysis, Samuel Pepys (1633-1703) started epidemic field investigation, William Farr (1807-1883) founded the modern concept of surveillance, John Snow (1813-1858) linked data to intervention, and Alexander Langmuir (1910-1993) gave the first comprehensive definition of surveillance.

Choi, 2012 [footnote 2]

Surveillance is a core function for Public Health England (PHE), highlighted in the PHE remit letter that sets out the role that the government expects us to play within the health and care system. This letter clearly states that PHE is expected to provide, among other things, ‘the national infrastructure for health protection including an integrated surveillance system’ [footnote 3].

In 2012 we published ‘Towards a Public Health Surveillance Strategy for England’, an overview of the vision, rationale and plans for the delivery of a surveillance strategy for PHE [footnote 4]. This document builds on that vision, acknowledging the definition, purpose and role of surveillance, and placing it within the current strategic framework of PHE, recognising related strategies, such as the:

- PHE publication standard

- Information and communications technology (ICT) strategy

- Knowledge and digital publication strategy

It recognises the need for high-quality evidence that is derived from our surveillance systems to better understand the wider influences on health. The document clearly describes the principles and standards that should underpin all of PHE’s surveillance activities, both current and future, and sets out the overarching strategic direction under which strategies for both infectious and non-communicable diseases can be developed.

3. Scope of this document

The central goal of surveillance is to provide information that can be used to support action by public health teams and individuals, government leaders and the public to guide public health policy and programmes.

This document will therefore relate to all tiers of the surveillance system.

- The collection, collation and analysis of data (data sources – primarily to assess health status, threats, determinants and influences) and the need to measure/capture health-enhancing variables such as employment level and quality, aspects of the built and cultural environments, forms of transport, among others.

- Operational information and intelligence (outputs such as alerting, and decisions to inform actions such as acute response).

- Strategic information and intelligence (outputs such as secondary analysis and decisions to inform actions such as policy and strategic planning).

Although intended primarily for those working within PHE, the principles described in this strategy will also be relevant to our partners, our stakeholders (locally, nationally and internationally) and other interested parties as it sets out what we hope to achieve, the standards and qualities we will adhere to and the framework within which we will operate.

4. Common set of principles

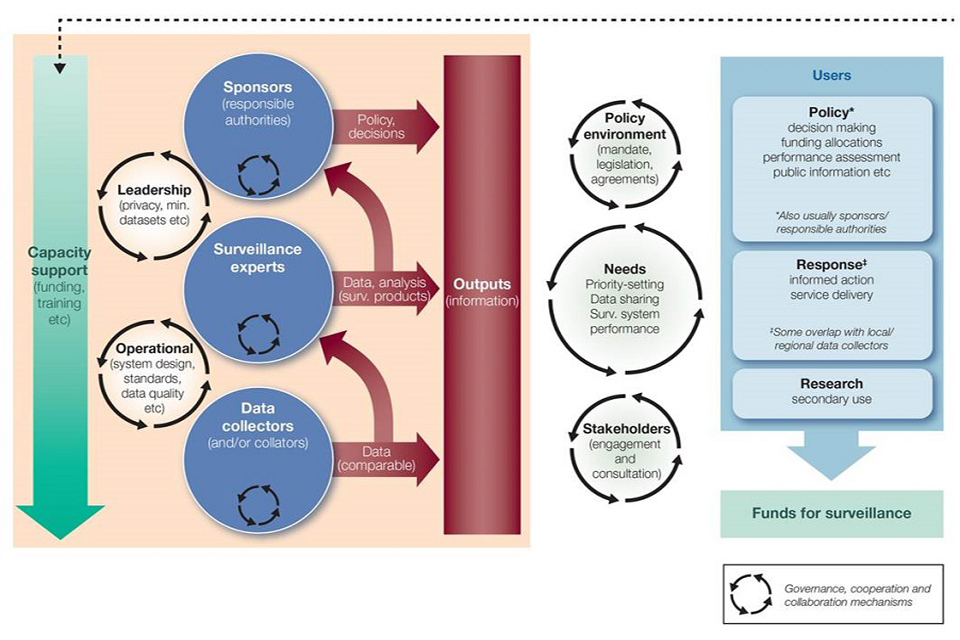

Surveillance activities in PHE conform to the principles of a proposed general model of health surveillance (Figure 1) [footnote 5] developed for a review of health surveillance functions in Canada. This model clearly shows the interconnected elements that make up the complete ‘system’ required to provide and support surveillance activities. It is in this context that the word ‘system’ is therefore applied in this document.

Figure 1: A general model for health surveillance

As the model describes, there are 3 layers that drive surveillance and inform the output of information, such as:

- data collectors

- surveillance experts

- sponsors

These have both operational and leadership roles and are underpinned and influenced by the degree of capacity support provided.

1. Data collectors

Data collectors ensure that comparable data are provided to, and available for, the surveillance experts.

2. Surveillance experts

Surveillance experts are required to ensure that data are analysed and interpreted so that the findings can be translated to support an informed response and improved service delivery. This also informs policy development and the role of the sponsor, and should be collaborative with knowledge experts.

3. Sponsors

Surveillance, along with the relevant knowledge and evidence base, informs policy decisions and ensures as far as possible that the appropriate mandate is in place, underpinned by relevant legislation and/or agreements. Sponsors are the authorities responsible for making sure that the correct systems are in place to prevent gaps and identify issues relevant to population health and wellbeing at an early stage. They should set out what conditions are important for surveillance, such as:

- objectives for surveillance

- what to do with signals or indicators

- how to use data for longer-term planning

PHE currently, and will continue to, adopt a standards-led approach to all of its surveillance activities and this is informed by internally agreed PHE surveillance standards. Important principles that are clearly defined within the standards are described below.

4.1 Aims of surveillance

Surveillance systems should have recognisable and/or defined public health goals and address specific public health priorities and objectives at a national, regional or local level. They should be subject to regular review, through consultation, with clearly identified internal and external stakeholders, including both providers and users of inputs and outputs respectively, and lead to demonstrable public health outcomes.

4.2 Surveillance objectives

Each surveillance system operating within PHE should have clearly specified objectives. Objectives should be regularly reviewed and systems evaluated to establish whether changes should be made or the surveillance should cease.

4.3 Data collection

All surveillance systems that involve data collection should have a clearly defined target population and case definition, as well as documented protocols for data collection including clarity on the legal framework within which data are justifiably collected. All data should be captured the minimum possible number of times necessary to meet the system objectives, either in the NHS, in PHE or in any other setting. PHE has a data catalogue that defines the primary data collections for which it is responsible.

4.4 Data storage

All surveillance information should be stored appropriately according to the type of data, in compliance with the Data Protection Act, and adhering to good information governance practice as defined by PHE and Cabinet Office guidance.

4.5 Data transfer

All data that contains patient identifiable information, or for which there is a risk of disclosure, should not be transferred unless necessary, that is, for a clinical response or direct public health action. If it needs to be transferred, this must be done using an appropriate secure method. Data sharing agreements or contracts should be implemented where appropriate.

PHE has a designated Caldicott Guardian who is responsible for protecting the confidentiality of patient and service-user information and enabling appropriate information sharing.

PHE has also established an Office for Data Release (ODR), which provides a systematic, risk-based approach to reviewing both internal and external requests to process PHE data for secondary purposes and to meet our obligations under the:

- Data Protection Act 1998

- common law duty of confidentiality

- Caldicott principles

- best practice set by the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO)

4.6 Data analysis

Standard operating procedures should be developed with clearly defined quality assurance processes. Tools should be developed to reflect, and be able to answer, the objectives of the surveillance activity or system and support the identification of trends and associations as well as analytical studies. Tools can range from statistical programmes and modelling to analysis through indicator development.

4.7 Dissemination of surveillance information

Surveillance outputs should be developed that meet the needs of those who are required to take action as a result of the information. They should be timely, high quality, accessible and, where appropriate, contain interpretation and recommendations. Outputs can include bulletins, reports and interactive web-based tools. Where appropriate, the concept of open data should be recognised and data made accessible whenever possible. Mechanisms should be in place to provide assurance that the right people are receiving the information.

4.8 Information for action

Surveillance data should be reviewed regularly by the appropriate staff to ensure the prompt identification of trends and the subsequent communication of any action that may be required. The responsible authority is often the sponsor, as set out in Figure 1, and should therefore be informed.

4.9 Quality assurance and information governance

The One PHE quality model is an internally developed quality framework that sets out our responsibilities with regards to quality and clinical governance across the organisation, and this advocates the application of a consistent approach to agreed standards. PHE continues to encourage a learning culture that inspires dedication to quality, innovation and improvement, supported by strong leadership and accountability at all levels. As such, all priority surveillance systems should comply with the internally developed PHE surveillance standards and be referenced in the PHE departmental quality plans, set out by the respective quality hub (the mechanism by which PHE oversees and monitors its quality work). This includes ensuring that there is a programme of audit (including quality and governance), with accountability for the findings and any subsequent action that needs to be taken.

The importance of confidentiality, integrity and availability is well recognised, with rules and policies in place to govern access to information, assurance regarding the trustworthiness and accuracy of the data and a framework that supports reliable, timely and appropriate access.

4.10 Capacity

It is essential that our surveillance activities are adequately resourced and that all staff with surveillance responsibilities are appropriately trained to ensure that standards are met. Training requirements for the system or activity must be clearly described and comprehensively documented.

4.11 System development

The following principles need to be applied and should, where appropriate, underpin any future information system development:

- designed to support the objectives expressed in relevant strategic and business plans, taking into account local requirements and reflecting the different needs of different business operations

- designed to support rather than constrain innovation

- follow the principles of re-use and integrate rather than build, buy new and potentially duplicate

- consider the use of cloud and digital platforms by default and cognisant of the PHE digital programme

- compatible with common data analytics and presentation tools, using consistent methods and common (business intelligence) tools

- adopt modern and future proof technologies and common platforms that can support new and emerging approaches, for example, whole genome sequencing (WGS)

- part of a single management line of sight

- reflect a modular approach

- Standardise and/or centralise as a priority

- of high, measurable quality – integrated validation, common data standards, auditable

- not disease specific or bespoke – core fields, master indexes, disease specific variables (features)

- interoperable – capable of interfacing / linking with other systems

- supportive of Application Programming Interfaces (APIs)

- high performance – optimised and indexed

- process driven

- responsive and flexible

- underpinned by robust governance – integrated archiving, comprehensive documentation, clear regulatory rationale

- secure and have auditable access control

- compliant with industry standard security measures such as the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) ‘good practice’ measures

- developed and adapted based on regular feedback from colleagues and stakeholders on how to best serve their needs

- collect and retain data only if there is a good business need for doing so, and such retention complies with the law and good practice

- resilient and ensure robust business continuity

- demonstrate value for money and clear business/public health benefits

- capable of being evaluated to establish whether they are fit for purpose and continue to meet the initial need and deliver on the agreed purpose

5. Quality

To ensure that all PHE surveillance systems and activities (from data input to output) are of high quality and fit for purpose, they should be regularly assessed using the established evaluation criteria as set out in recognised guidelines. [footnote 6] [footnote 7] The outcome of these reviews should be clearly set out and system owners held accountable. The evaluation criteria are:

- simplicity

- flexibility

- data quality

- acceptability

- sensitivity

- predictive value positive [footnote 8]

- representativeness

- timeliness

- stability

Through the systematic evaluation of our surveillance systems, we will continue to ensure that we promote the best use of data collection resources and that our systems are operating effectively. These reviews will provide assurance that our surveillance systems are beneficial for a defined public health initiative and are achieving the data collection objectives and central goals of the public health program. They will also ensure that recommendations for improving the quality and efficiency of the systems and a timeline for implementing changes based on available resources are made, encouraging iterative and regular review and improvement.

PHE has developed an internal, operationally focused surveillance and quality framework that sets out the requirements for surveillance within PHE and includes an audit framework to support the assessment of compliance against agreed surveillance standards. This provides PHE with an internal mechanism to assess the quality and robustness of surveillance systems and identify and resolve any issues.

6. Governance

Surveillance activities within PHE are overseen by the PHE surveillance strategy group, chaired by the Director of Health Improvement and accountable to the PHE strategy group. The PHE surveillance strategy group is also responsible for providing assurance and promoting cross-working and integration across all domains of public health within PHE, as well as raising awareness of the work of other complementary agencies. Its role is to build on work that has already been undertaken, including the development of internal surveillance standards and a supporting quality assurance framework, as well as other cross-organisation activities delivered in the context of the 2012 document, ‘Towards a Public Health Surveillance Strategy for England’ [footnote 4].

At a strategic level, the group oversees both existing and proposed new surveillance activities undertaken or commissioned by PHE, including appropriate risk management with regards to surveillance. It also promotes and leads stakeholder engagement processes to ensure that PHE surveillance outputs meet the needs of key stakeholders and support core public health functions. The group has a key horizon scanning role, within and outside of PHE, to ensure that we are aware of what others are doing and the potential effects or benefits on internal systems. It promotes active engagement with academics, enabling better knowledge through evidence and through the identification of gaps with regards to the strategy, and also with funders to stimulate academic research. It should be recognised that surveillance activities will often generate hypotheses that warrant further research and this should be encouraged where appropriate.

The PHE surveillance strategy group has a number of sub and task groups that report to it, which focus on specific areas such as non-communicable or infectious disease and which have responsibility for surveillance activities and systems that are not cross-PHE (that is, are at directorate level).

As set out in Figure 1, it should be noted that it is the sponsor of the surveillance that is the responsible authority and therefore must ensure that the appropriate governance arrangements are in place.

Consideration should also be given to the application of a maturity index [footnote 9] to our surveillance activities, enabling us to quantify the quality of our data and providing us with a measurement that can be built upon, through quality initiatives, to demonstrate improvements.

6.1 Decision-making process

The PHE surveillance strategy group is responsible for ensuring that all surveillance activities within PHE are integrated (if appropriate), efficient and to a consistently high standard. As such, any decisions relating to strategic surveillance activities, such as the development of a new system, should be presented to the group for consideration and formal sign off (unless there is an alternate forum designated to undertake this role, as is the case for indicator development). Where decisions are specific to a directorate or topic area, these should be made by the relevant sub-group, with the PHE surveillance strategy group sighted for information.

7. Sharing knowledge

Sharing knowledge across PHE is paramount to ensure that we capitalise on best practice, innovation and efficiencies.

Routine surveillance outputs should be published to an agreed timetable, distinguishing between raw (disaggregate) and aggregated data and recognising that different people need different data to support their work and will have different levels of permission. Equally, timeliness of data sharing and outputs will be determined by the public health need and purpose of the data collection and use.

PHE has established an internal Knowledge and Library Service, which aims to maximise co-operation, collaboration, resource sharing and cost-effectiveness. They support the embedding of knowledge management processes, tools and techniques throughout PHE to enhance sharing and learning from experience and make better use of internal knowledge and expertise. This approach could support the sharing of knowledge and ideas relating to our surveillance activities.

There are also other mechanisms for knowledge sharing that should be considered, such as the PHE Knowledge Hub (KHub). KHub is a website that has been developed to share information about local knowledge and intelligence products and services, enabling staff to share knowledge on topics such as the use of digital platforms and outputs. KHub is available internally as well as externally.

We also have much to learn from our stakeholders and partner organisations, including academic colleagues locally, nationally and internationally. Where appropriate, partnership working and collaborative projects should be encouraged.

As set out in Figure 1, we are dedicated to making data available to all of our users, including those that are responsible for policy development, those leading the response through informed action and service delivery and, where appropriate, for secondary use through research.

8. Training

It is essential that PHE develops and supports a workforce with the skills and knowledge to deliver high-quality disease surveillance that is responsive and supports public health action. We recognise the importance of workforce development and this is demonstrated in the Public Health Skills and Knowledge Framework (PHSKF), a UK-wide tool that describes the areas of work delivered by people working towards the delivery of public health outcomes – both the specialised core workforce and the wider workforce. This framework has been developed through the collaborative efforts of a number of lead public health organisations [footnote 10].

Within PHE there are a number of training modules and courses that support surveillance activities. For example, we have developed health intelligence courses that support the development of a wide range of skills that can be applied to surveillance activities. There are also more specialist health protection courses that include surveillance activities [footnote 11] and online modules that have been developed by other organisations, such as the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention [footnote 12].

Many training courses have been developed collaboratively with academic partners and this approach often has the benefit of combining academic and operational perspectives.

9. Resources and business planning

As already acknowledged, the success of any surveillance activity is determined by the adequacy of the resource that drives it. This can be through initial funding, staffing, training or the development of new technologies and approaches.

An integrated approach with other functions and services in the organisation is essential for a number of reasons, including efficiency of staff time and expertise as well as sharing best practice. For example, the PHE ICT strategy needs to support the delivery of the surveillance activities and work needs to be undertaken with communications colleagues to ensure that the outputs are provided to the right stakeholders in a timely and appropriate way. As PHE looks to develop a formal data strategy, it will need to ensure that data and information management processes are robust and of high quality, supporting the flow of information from point of collection to output and ultimately public health action. Links with research should also be considered, within the appropriate governance framework.

It is also vital that the acknowledged surveillance activities of PHE are embedded in the business planning process. This will ensure that our organisation’s goals with regards to surveillance are clearly defined and the importance of these activities in delivering PHE’s vision is recognised.

10. How PHE’s role fits with other organisations

Many of PHE’s surveillance activities are dependent on other organisations for some aspect of the function, from data collection and provision to consultation with regards to outputs and intelligence to inform public health action. Equally, some organisations are dependent on our data, so engagement with the wider public health system is always critical to deliver many surveillance activities and we must not work in isolation.

PHE commissions, holds and reports on various surveys and works with other organisations to ensure that these data are available to inform public health actions. For example, population surveys provide routine information on a number of behavioural risk factors and are recognised as a key data collection tool for this type of information.

PHE should continue to work with devolved administrations to share data and produce joint reports where appropriate, and ensure that surveillance objectives can be fulfilled (for example, for outbreak detection). This can be codified in separate agreements.

11. Examples

Figure 1 describes 3 distinct layers within the overall model for health surveillance:

- data collection

- data analysis undertaken by surveillance experts

- sponsors: those who are responsible and make policy decisions

These layers are clearly apparent in PHE’s surveillance activities and examples are provided below to illustrate this.

11.1 Infectious disease: tuberculosis (TB)

PHE’s national mycobacterium reference laboratories are in the process of replacing conventional laboratory workflows with methods based on WGS. Tuberculosis surveillance schemes collect, link and analyse data obtained from clinicians and from laboratories, among other things, to describe and monitor trends in incidence and in antibiotic resistance and to detect and track clusters of infection and outbreaks.

Traditional laboratory methods have relied on separate processes to identify the mycobacterium species, determine susceptibility to a range of antibiotics and to ‘type’ the isolate to assess the likelihood of transmission between different infected patients. All of these conventional methods are time-consuming. WGS allows reasonably rapid identification to species, resistance/susceptibility prediction and measurement of genetic relatedness using a single method.

As a method, WGS is portable. Any laboratory can sequence isolates and upload data to a central national pipeline to generate a shared pool of data that can be linked with clinical data feeds for surveillance purposes. This approach could in theory be applied to any pathogen and applied globally, meaning WGS can be seen as a method that is driving the modernisation of laboratory microbiology, epidemiological investigation and surveillance.

In particular, WGS allows comparison of the genetic relatedness of isolates at higher resolution than is possible using conventional methods (for example, mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit variable number of tandem repeats (MIRU VNTR)). Unlike conventional, relatively low-resolution typing methods that assign isolates to a category (for example, ‘type A’ or ‘cluster B’), WGS provides an exact indication of the genetic differences (single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)) between isolates, allowing precise mapping of emerging clusters and transmission networks and exclusion of more distantly-related cases. This change necessitates a need to develop new tools to visualise and interpret the more informative but more complex data and familiarisation of users to allow full exploitation of the data.

11.2 Non-communicable disease: cancer clusters

The National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service (NCRAS) collects data on all cancers diagnosed in England. Cancer is a health issue that concerns many members of the public, and NCRAS receives a number of enquiries on cancer in small areas, sometimes referred to as ‘clusters’. It has a standard operating procedure in place to address these, which aligns with the 3 layers above. All investigations into cancer in small areas are at the request of the local director of public health, who is the project sponsor. Collection is undertaken by the registration section of NCRAS, with the analytical section undertaking the analysis. Analysis is frequently carried out in conjunction with colleagues in other parts of PHE (for example, the local Centre) and in local authorities.

There are also examples of longer-term surveillance of cancer in a specified area. The Oldbury (South Gloucestershire) nuclear power station closed in 2012 and is undergoing decommissioning. Since 2009 processor organisations to PHE have produced regular reporting on cancer incidence, mortality and trends in the area around the power station. The sponsors are the Oldbury Interest Group (public), Magnox Limited (the site owners), South Gloucestershire Unitary Authority, and PHE. In this instance, data collectors are NCRAS and the Office for National Statistics, with data analysed by NCRAS. The most recent report was produced in 2013 and was discussed at a public meeting attended by all the sponsors.

11.3 Non-communicable disease (environmental): radon

Radon is a radioactive gas that is continually formed in, and released from, rocks and soil. Inhaling radon and its radioactive decay products is recognised by the International Agency for Research into Cancer (IARC) as a Class 1 lung carcinogen and is included in the IARC European Code Against Cancer. Indoor radon levels vary greatly, both geographically and between individual buildings, by a factor of up to 1,000. Radon maps identify areas where measurement of properties is advised, and PHE provides guidance on levels at which domestic radon should be reduced. High levels can be reduced by appropriate modest building works.

Radon surveillance programme

PHE maintains a programme that:

- identifies radon-affected areas where it is worthwhile to test properties for high radon levels

- provides guidance and services on radon measurement in homes and workplaces

- delivers and promotes targeted projects to address radon in the most affected areas

- maintains and publishes a database of radon measurements

- undertakes research into important aspects of radon, its health risks and interventions

PHE’s work supports existing regulatory controls on radon, especially prevention against radon in new-build properties built in high risk areas, as well as workplace radon risk assessment and management. A recent European Union (EU) Directive (2013 - Basic Safety Standards against Ionising Radiation) is being transposed into UK law and will extend the range of statutory requirements on radon. To support this surveillance, PHE collects radon data, primarily from its radon measurement services for homes and workplaces. This database currently holds more than 700,000 records, mostly for homes. Main characteristics of the surveillance activities include:

- measurements are made to an established protocol (HPA-RPD-047)

- PHE’s work targets the areas where high levels (and therefore risks) are more likely

- results are reported to the customer with advice about remedial measures where necessary

- individual results are not published but statistical summaries are (for example, PHE-CRCE-031 to 034)

- those who remediate high levels are offered a free post-remediation re-test and questionnaire to obtain information about remediation performance, trends, among others

Analysis of surveillance activities

PHE’s radon surveillance includes a combination of regular and specific studies, including:

- review and update of radon risk maps in partnership with the British Geological Survey (BGS), using dwelling measurements combined with BGS digital geological mapping

- targeted surveys/campaigns in areas where high levels are most prevalent (for example, HPA-CRCE-042)

- long-term durability and performance of installed remediation systems

- performance of various remediation systems (for example, HPA-CRCE-019)

- radon knowledge and actions of purchasers of homes with ‘built-in’ radon prevention (for example, PHE-CRCE-024)

- significance of radon exposure in workplace basements (PHE-CRCE-028)

- epidemiology of radon

- equity analysis of radon knowledge and action (HPA-CRCE-013)

Other groups in Centre for Radiation, Chemical and Environmental Hazards (PHE-CRCE) undertake and contribute to the underlying understanding of the health risks from radon through research into the biokinetics, radiation dosimetry and epidemiology of radon, working with international bodies and relevant external partners.

Sponsors for PHE radon work

The main internal sponsor of PHE’s work on radon as an environmental hazard is the Director of Centre for Radiation, Chemical and Environmental Hazards (CRCE). Since radon is the single largest source of ionising radiation exposure to the UK population, both at home and at work, and PHE plays a central role in providing guidance, services, information and undertaking relevant research, an ongoing work programme is maintained. PHE works closely with a range of partners to maintain and develop the UK radon programme with the twin aims of reducing high exposures and reducing the overall level of radon exposure. Updates and reviews of the programme are presented through appropriate stakeholder channels including:

- PHE stakeholders through the environmental public health network

- regular liaison with the Department of Health, devolved administrations and the Health and Safety Executive

- external stakeholders (for example, through UK Radon Forum, 5 Nations Health Protection Forum)

- liaison with relevant specialist industry groups

A current development project is investigating the potential use of a radon indicator within the PHE Fingertips web-based tool, based on the prevalence of homes in areas of highest radon risk in English local authorities (derived from the PHE/BGS radon risk map dataset), coupled with information about how many local properties have been tested by PHE.

11.4 Knowledge – the Public Health Outcomes Framework

The Public Health Outcomes Framework (PHOF) sets out a vision for public health, desired outcomes and the indicators that help understand how well the public’s health is being improved and protected. The Department of Health are the sponsors of the PHOF and set out the policy framework (as originally published in Healthy Lives, healthy people: improving outcomes and supporting transparency (DH 2012)). The PHOF contains a large number of indicators across a broad range of topics and includes indicators on the wider determinants and health outcomes.

The indicators contained within the PHOF are derived from a variety of data sources. Typically, indicators include those routinely produced by other government departments, but can also include indicators produced by PHE using data held within PHE, such as hospital episode statistics (HES) data, mortality data and survey data. Indicators are produced at national level and local authority level.

The online web tool contains a number of features which allow for effective surveillance, for example:

- it is updated regularly on a quarterly schedule

- it is possible to compare a local authority against a choice of benchmarks to see whether they are performing significantly better or worse, including similar authorities, for example, ‘nearest neighbours’ or those geographically adjacent

- trends can be observed and the tool provides information as to whether these are statistically significant changes over time

The PHOF as a surveillance tool enables users to quickly understand the priorities within their local area. The main users of the PHOF online tool are public health departments located within local authorities, though it can include various users within PHE such as the Local Knowledge and Intelligence Service (LKIS), as well as other government departments, charities and third sector organisations and academics. The outputs from the PHOF are used to provide evidence and justification for decisions on commissioning or recommissioning services, for planning purposes and to inform local policy.

11.5 An evidence synthesis approach

Local estimates of hepatitis C virus (HCV) prevalence in people who inject drugs are produced every 2 to 3 years [footnote 13] [footnote 14]. This is based on unlinked, anonymous prevalence surveillance data, which is combined with information on those in drug treatment and Office for National Statistics (ONS) data on drug crime and age composition of the population. High levels of drug crime and proportions of young adults have been found to be associated with increased HCV prevalence, and these data can therefore be used to increase the precision of local HCV prevalence estimates where surveillance data are sparse.

Due to the difficulties in obtaining representative samples with which to monitor HCV prevalence, estimates are based on the combination of multiple evidence sources to simultaneously estimate risk group sizes (in particular people who currently inject, or have previously injected drugs) and prevalence therein [footnote 15]. Back-calculation approaches that link data on severe liver disease with estimates of disease progression have also been used to estimate the future burden of HCV and potential to avert rising disease through increased treatment [footnote 14] [footnote 15]. Work is currently underway to combine aspects of these approaches, making use of routinely collected datasets in order to monitor HCV prevalence and the impact of new treatments as these are rolled out by NHS England.

12. Appendix: PHE data catalogue of primary data collections

The primary data collections that PHE currently manages can be classified as follows:

- health protection incident/case management and outbreak control

- vaccination and immunisation services

- chemical, radiological and biological source and exposure monitoring

- communicable and non-communicable disease surveillance

- population disease screening programme management and quality assurance

- microbiological and other specialist laboratory testing and reporting services

- disease registration

- patient- and population-level health and social care service monitoring and evaluation

- environmental, socio-economic, behavioural, and genetic health risk factor monitoring

- health improvement service marketing and the provision of information, sign-posting and interventions

13. References

-

The Academy of Medical Sciences, 2016. ‘Health of the public in 2040’ ↩

-

Bernard C. K. Choi. ‘The Past, Present, and Future of Public Health Surveillance’ Scientifica 2012: volume 2012, Article ID 875253, 26 pages ↩

-

Public Health England. ‘Towards a public health surveillance strategy for PHE’. 2012 ↩ ↩2

-

John Newton personal communication ↩

-

CDC. ‘Updated Guidelines for Evaluating Public Health Surveillance Systems’. MMWR July 27, 2001: volume 50(RR13), page 1 to 35 ↩

-

WHO. ‘Evaluating a national surveillance system’ 2013 ↩

-

Proportion of persons identified as having cases who actually do have the condition under surveillance. ↩

-

A measurement or assessment scale that indicates the degree of progress made, with respect to the issue or problem that is being addressed. ↩

-

‘Healthy Lives, Health People: A public health workforce strategy’ ↩

-

Public Health England. ‘Health Protection and Epidemiology Training’ ↩

-

Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. ‘Training and Continuing Education Online’ ↩

-

Harris, R. and others). ‘Spatial mapping of hepatitis C prevalence in recent injecting drug users in contact with services. Epidemiology and Infection 2012: volume 140, pages 1054 to 1063 ↩

-

Public Health England. ‘Unlinked Anonymous Monitoring Survey of People Who Inject Drugs (PWID) ↩ ↩2

-

Harris RJ and others. ‘Hepatitis C prevalence in England remains low and varies by ethnicity: an updated evidence synthesis’ European Journal of Public Health 2012: volume 22, pages 187 to 192 ↩ ↩2