Planning and Preparing for Later Life 2024

Updated 14 August 2025

DWP research report no. 1103.

A report of research carried out by National Centre for Social Research (Nat Cen) on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions.

Crown copyright 2025.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence.

Or write to:

Information Policy Team

The National Archives

Kew

London

TW9 4DU

Email: psi@nationalarchives.gov.uk

This document/publication is also available on the GOV.UK website.

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email socialresearch@dwp.gov.uk

First published July 2025.

ISBN 978-1-78659-862-2

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Executive summary

Planning and Preparing for Later Life is a nationally representative survey of adults aged 40 to 75 in Great Britain commissioned by the Department for Work and Pensions. The 2024 survey, which collected data from 4,036 adults via an online survey at the end of 2024, is the second in the survey series. It provides an opportunity to understand more about how people prepare for retirement and how this process may have been affected by changes to economic circumstances and pensions policy since the first wave of data collection in 2020 to 2021.

This report presents some key findings from the survey and covers:

- The Later Life Landscape: including background context of people’s working arrangements and pension provision as they approach retirement. According to PPLL, 24% of 40 to 75 year olds were fully retired and a further 10% were semi-retired. 75% of people had a private pension, though this was less common among the self-employed, people on low incomes and renters.

- Expectations around retirement: Most people expected to fund their retirement at least in part through the State Pension, with 44% of 40 to 75 year olds not yet retired expecting half or more of their income in retirement to come from the State Pension. 65% of people said the State Pension amount was very important or important in their decision around when to retire. The median age at which people expected to retire was 66 whereas the median ideal age at which people wanted to retire was 60.

- Planning for retirement: Most people (59%) started saving for their retirement in their 20s or 30s while people generally started actively planning for their retirement in their 50s (45% of people who were semi-retired and 40% of people who were fully retired). 53% of people had used at least one source of information in the past 12 months to help them plan for retirement. However, only 18% had used regulated advice or guidance (a financial advisor or Pension Wise).

- Income adequacy in retirement: People aged 40 to 75 were less confident that they would be able to achieve the lifestyle they wanted in retirement in 2024 compared with 2020/2021. 41% of people aged 40 to 75 said they ’had no idea’ how much income they would need in retirement. 33% of those who had some idea of their income needs said they would need a higher proportion of their current income in retirement than they expected to have.

- Pension decision making: People who had already accessed their pension were generally confident about the decision they had made (rating their confidence an average of 7.3 on a 0 – 10 scale). However, 77% of DC pension holders aged 40 to 75 and yet to access their DC pension did not have a clear plan for how to do so. 21% did not know they had to make a choice of how to access their pension.

A separate report, looking at people’s willingness to pay for pension products and services, is also available.

Acknowledgements

This research was commissioned by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) and was carried out by the National Centre for Social Research (NatCen) in collaboration with WPI Economics, the Institute for Employment Studies (IES) and Pensions Policy Institute (PPI). The authors would like to thank Inez Gallagher, Kieran Phillips, Sarah Kate O’Grady, Matthew Lawless and Rachel Riggs for their support during the project.

The successful delivery of the Planning and Preparing for Later Life Survey relied on input from a wide range of people at NatCen, including survey programmers Pamela Ritchie and Jatin Bhatt, data managers Migle Aleksejunaite and Martin Hogg, statisticians Christos Byron and Tobi Li, Telephone Unit managers Sonia Shirvington and Joy Linstead, the telephone interviewers working on the project, and Alun Humphrey, Head of Household Surveys at NatCen. Head of NatCen’s Questionnaire Design and Testing hub Joanna D’Ardenne, along with Sophie Pilley, oversaw the cognitive testing of the questions. Helena Wilson also worked on the questionnaire. The segmentation analysis was carried out by Sam Beardsworth and Ekaterina Khriakova.

We would like to thank James Edgar, Rob Fontana-Reval and Edward McPherson at WPI Economics for their invaluable expertise around asking questions to capture people’s willingness to pay for pension products and services. Lauren Wilkinson and John Upton at the Pensions Policy Institute and Zofia Bajorek and Jonny Gifford at the Institute for Employment Studies provided useful feedback on both the survey questionnaire and the report.

Author details

The report was written by Sarah Butt, Bethany Chapman, Olivia Cottis Black, Amy Dyer and Sinead Palmer at the National Centre for Social Research.

Glossary

Annuity: A form of insurance policy that consumers can buy with their pension pot. This will typically provide the consumer with a guaranteed income for life, or for a fixed number of years.

Automatic Enrolment: A legal requirement that every employer must automatically enrol its workers into a quantifying pension scheme subject to certain criteria. Employers gradually enrolled all eligible workers into qualifying pension schemes between 2012 and 2018.

Default pathways for accessing Defined Contribution pension: The government is legislating in the Pension Schemes Bill introduced in 2025 to require pension providers to offer pension holders a default option for how to access their DC pension. Under this approach pension providers would propose an option for the pension holder based on what they know about the pension holder’s needs and financial circumstances. The pension holder would be consulted on the default solution and would have the option to choose an alternative if they wanted. The survey referred to a version of this policy, using the language of ‘default pathway’ to describe a situation where a decumulation decision is made by a provider on behalf of a pension holder. The survey did not specify that the pension holder would be able to choose an alternative option like in the measures proposed in the Pension Schemes Bill.

Defined Benefit (DB): A scheme in which the benefits are defined in the scheme rules and build up regardless of the contributions paid and investment returns. The benefits are most commonly related to members’ earnings at the point they leave the scheme or retire, and the length of their pensionable service. These are also known as ‘final salary’ or ‘salary-related’ schemes. DB benefits are guaranteed or underwritten by the sponsoring employer.

Defined Contribution (DC): A scheme in which a member’s benefits are determined by the value of the pension fund. The value of the fund at any time depends on contributions and performance of investments.

Financial literacy: Respondents’ financial literacy score was calculated based on their answers to 3 financial questions. These questions were the same as those used in the Financial Conduct Authority’s Financial Lives survey.

Income drawdown: Flexi-access income drawdown products involve investing a pension pot into a fund or funds which allow the consumer flexible access. The consumer can withdraw funds when they want and use this as an income. Income drawdown providers offer a range of different funds, with different investment objectives, risks, and levels of charges.

Midlife MOT: A Midlife MOT is a service for individuals in mid-life that helps them take stock of their finances, skills and health, and enables them to better prepare for their retirement and build financial resilience. A Midlife MOT can take the form of a discussion (such as the Job Centre Plus Midlife MOT group sessions) or a web-based tool such as the DWP Midlife MOT website which was launched in 2023.

Pension Wise: A free and impartial service set up by the Government in 2015 offering guidance for people regarding Pension Freedoms introduced in the 2014 UK budget. The service is available to people aged 50 years and over with a DC pension to help them understand what they can do with their pension pot(s). Guidance is delivered via telephone, face to face appointments, or online.

Retirement Pack: Packs pension providers are required to send to people 4-6 months before they may be accessing their pension. Packs are aimed at ensuring people receive timely, relevant and adequate information about their retirement options to enable them to make an informed decision about accessing their pension savings. Some pension providers (those regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority) are now also required to provide a single page summary retirement pack from age 50, and every 5 years after that, until the pension pot is accessed. Retirement packs are sometimes referred to as ‘wake-up packs’.

Semi-retirement: The report distinguishes between people who are fully retired and people who are semi-retired. Survey respondents over 50 were given the opportunity to self-define their retirement status as “not yet retired”, “semi-retired” but doing some paid work/may do some paid work in the future or “fully retired” and not intending to do any more paid work.

Simple Annual Benefit Statement: A short document (no more than 2 pages) provided by pension providers to people with Defined Contribution pensions which sets out: how much money people have in their pension pot, how much they are likely to have by the time they retire and what they could do to give themselves more money in retirement.

State Pension Age (SPa): The age at which an individual can claim their State Pension.

Abbreviations

AE: Automatic Enrolment (into workplace pension)

DB: Defined Benefit (pension)

DC: Defined Contribution (pension)

PLSA: Pensions and Lifetime Savings association

PPLL: Planning and Preparing for later Life Survey

SP: State Pension

SPa: State Pension age

TRR: Target Replacement Rate

Summary

The Planning and Preparing for Later Life Survey (PPLL) 2024 was commissioned by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) to provide up to date information on people’s attitudes and behaviours around planning for retirement. This survey is the second in the series, following on from the first wave of PPLL conducted in 2020 to 2021.

The 2024 survey had 4 main objectives:

- to understand attitudes and behaviours around pension saving and planning for later life

- to provide evidence to support policy development around income adequacy in retirement

- to gather evidence on attitudes and knowledge around the State Pension system

- to gather evidence on the value consumers place on DWP products, policies and services

PPLL collected data from a nationally representative sample of 4,036 adults aged 40 to 75 in Great Britain. Data were collected via a 45 minute online self-completion survey (with the option to complete via the telephone on request) between 30 October and 7 December 2024.

The sample for the survey was drawn from respondents to the 2022 to 2023 and 2023 to 2024 Family Resources Surveys aged 40 to 75 who had agreed to be contacted for further research. The data have been weighted to ensure that findings can be generalised to the population of 40 to 75 year olds in Great Britain. The final data have been calibrated against ONS mid-year population estimates and Labour Force Survey estimates to ensure that they closely resembled the target population in terms of sex, age and region.

Read a separate report discussing survey findings on people’s willingness to pay for different products and services.

The later life landscape: This chapter presents headline findings from the survey on the working and pension saving habits of the 40 to 75 population covered by the report. The chapter also presents the results of a segmentation analysis identifying 5 different groups within the 40 to 75 year old population with different levels of preparedness for retirement. Key findings include:

- 24% of 40 to 75 year olds were fully retired and 10% were semi-retired. From the age of 65, there was a sharp increase in the proportion of people who said they were fully retired (66% of people aged 65 to 69).

- 60% of people 40 to 75 in paid work said they wanted to work less as they approached retirement. When asked what would help them keep working longer, 46% of people who had not yet retired from paid work mentioned working fewer hours or being able to take more holidays.

- 75% of people aged 40 to 75 had a private pension. People on lower incomes, renters and with a long-term limiting health condition were less likely to have a private pension. 54% of people without a pension mentioned not being able to afford it as a reason for not having a pension.

- 38% of 40 to 75 year olds had no savings, while a further 2 in ten (20%) had savings of under £15,000. 78% of social renters and 66% of private renters reporting having no savings, compared with 17% of people who owned their home outright.

- A segmentation analysis revealed 5 distinct groups with different levels of preparedness for retirement among the 40 to 75 population (including those already retired and those yet to retire). This included 14% of the population who were classed as “Secure and Confident” but also 16% who were classed as “Unprepared and financially vulnerable”.

Expectations for retirement: This chapter presents findings on the importance of the State Pension in people’s planning for retirement, including people’s knowledge of and understanding of the State Pension and whether they expect to retire above or below State Pension age. Key findings include:

- Around two-thirds (65%) of people below State Pension age said the amount of State Pension they receive would be very important or important in their decision on when to retire.

- 52% of people below State Pension age said they had ever checked their State Pension age while 41% had ever checked what the amount of State Pension they might receive is. These proportions increased with age.

- One in ten people below SPa were able to identify the full rate of the new State Pension (although not all people in this age group would be entitled to this amount). However, a further 35% were within 10% of the actual figure. People were far more likely to underestimate (71%) than to overestimate (19%) the amount.

- The median ideal retirement age for 40 to 75 year olds who had not yet retired was 60. However, the median expected retirement age was 66, with 72% of people who had not yet retired expecting to retire later than their ideal age.

- 44% of people expected to retire before their State Pension age. Working beyond State Pension age was more common among the self-employed, people without a Private Pension, people on low incomes and renters.

Planning for retirement: This chapter presents findings on when people start planning for retirement, the information sources they use to plan for retirement and how actively engaged they are in managing any private pensions. Key findings include:

- People were most likely to say they started saving for their retirement in their 20s or 30s with 59% having done so. People started actively planning for their retirement at a later age. 45% of people who were semi-retired and 40% of people who were fully retired started planning in their 50s, with only 22% of semi-retired people (21% fully retired) starting earlier.

- 52% of 40 to 75 year olds had used at least one source of information to help them plan for retirement in the last 12 months. 33% had used less formal information sources such as family and friends or their employer whereas only 16% had used a regulated source of advice or guidance (either an independent financial advisor or Pension Wise).

- How confident people felt making decisions about pensions varied. The mean confidence score on a 0 to 10 scale was 5.1. Nearly half (48%) of 40 to 75 year olds rated their confidence between 6 and 10 on the scale but 13% rated their confidence as 0. People with high financial literacy, who had used regulated advice or guidance in the last 12 months and with a private pension felt more confident making decisions about pensions.

- Engagement with private pensions was limited. Most DC pension holders aged 40 to 75 (79%) recalled having received a simple annual benefit statement. However, only 46% of all private pension holders aged 40 to 75 said they had reviewed the value of their private pension in the last 12 months while 25% had reviewed the investment strategy of their pension.

- 24% of private pension holders aged 40 to 75 said they found it fairly or very difficult to keep track of their pension. The government is developing a pensions dashboard to help people keep track of their pension(s). Most people aged 40 to 75 said they would be very (50%) or fairly likely (31%) to use a pensions dashboard.

Income adequacy in retirement: This chapter presents findings on how confident people are that they will be able to achieve the lifestyle they want in retirement, their expectations for their income and expenditure in retirement, and the extent to which housing tenure plays a role in that. Key findings include:

- People aged 40 to 75 were less confident that they would be able to achieve the lifestyle they wanted in retirement in 2024 compared with 2020/2021. When asked to rate their confidence on a scale from 0 to 10 the mean confidence score in 2024 was 4.7, compared with 5.8 in 2020 to 2021.

- 41% of people aged 40 to 75 said they ’had no idea’ how much income they would need in retirement. This figure was higher among younger age groups and the less financially secure, that is those on lower incomes and renters compared with owner occupiers.

- Among people who had some idea of the income they would need in retirement, the median estimated income needed was £24,000 - below the PLSA threshold of £31,700 for a single person to live a moderate lifestyle. However, £24,000 is broadly in line with what a median earner would need to achieve their Target Replacement Rate.

- 33% of people aged 40 to 75 who had not yet fully retired from paid work and who had some idea of their income needs said they would need a higher proportion of their current income in retirement than they expected to have.

- 82% of people aged 40 who had not yet retired expected to fund their retirement at least in part via a private pension. People with a private pension were more likely than people without a private pension to also have access to other sources of income in retirement including savings and investments. Nearly half (49%) of people without a private pension expected 90-100% of their income in retirement to come from the State Pension.

- People varied in how reliant they expected to be on their partner’s income in retirement. On average, women rated their level of reliance on a partner (5.3 on a 0 – 10 scale) higher than men did (3.0 on a 0 – 10 scale).

- 68% of 40 to 75 year olds who had not yet retired expected to own their own home outright by the time they fully retired from paid work. Among those who did not expect to own their own home, the main reason given (by 80%) was not being able to afford it.

Pension decision making: This chapter presents findings on when and how people choose to access their Defined Contribution Pension, how confident people feel making decisions around accessing their pension and what, appetite there is for pension providers to offer default benefit options for accessing pensions:

- Among people who had already accessed their pension, the average age at which they did so was 60. Employees, people on higher incomes, and those buying a home with a mortgage were all more likely to have accessed a pension by age 60.

- 53% of people aged 40 to 75 wanted their pension to provide them with a guaranteed income for life. This compares with 31% who wanted a flexible income and 12% who wanted a flexible income up to a certain age and then a guaranteed income thereafter. Younger age groups and people with smaller pension savings were the most likely to want a guaranteed income for life.

- The majority (77%) of DC pension holders yet to access their pension did not have a clear plan for how to do this. This includes 56% who knew they had to make a choice but did not have a clear plan, and 21% who were not aware they had to make a choice. Only 22% had a clear plan.

- 41% of DC pension holders who knew they had to make a choice said they planned to take an annuity compared with 58% who planned to move their pension into flexi-income drawdown. 67% said they would take some of their pension as a cash lump sum while only 16% planned to fully cash in their pension.

- People aged 55 and over who had accessed their DC pension since 2015 were generally confident that they had made the right choice to meet their retirement goals. Asked to rate their confidence on a scale from 0 to 10, the mean score was 7.3.

- 83% of people who had accessed a DC pension since 2015 had taken at least some of their pension as a lump sum. 37% of people who took a partial lump sum used it for a one-off purchase while 30% paid off debts. Most people (87%) were either very or quite satisfied with their decision to take a lump sum.

1. Introduction

This report presents new evidence on planning for retirement among 40 to 75 year olds. The findings are based on analysis of a representative survey of 4,036 40 to 75 year olds in Great Britain conducted in November and December 2024.

Research aims

The Planning and Preparing for Later Life Survey (PPLL) 2024 was commissioned by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) to provide up to date information on people’s attitudes and behaviours around planning for retirement. It is the second in the survey series, following on from the first wave of PPLL conducted in 2020 to 2021.

Since the 2020 to 2021 survey was conducted, the context in which people are planning for retirement has changed. People’s employment and financial circumstances may have been affected by the legacy of the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the rising cost of living experienced since 2022. In addition, the pensions policy landscape has continued to evolve with the government publishing its response to the latest State Pension age Review and announcing a new Pension Schemes Bill in the 2024 King’s Speech. The new survey provides evidence to inform future developments.

The 2024 survey had 4 main objectives:

- to understand attitudes and behaviours around pension saving and planning for later life

- to provide evidence to support policy development around income adequacy in retirement

- to gather evidence on attitudes and knowledge around the State Pension system

- to gather evidence on the value consumers place on DWP products, policies and services

Policy context and research questions

This report focuses on people’s attitudes and behaviour in 3 key areas: awareness of, and expectations around, the State Pension; people’s level of active engagement with planning for retirement and, in particular, managing any private pensions they might have; and people’s expectations around, and confidence in, having an adequate income in retirement.

As described more fully in the next chapter, the UK has an ageing population. This has necessitated changes to State Pension arrangements to ensure that the system can be sustained and remain consistent with the principle that people should spend around a third of their adult life in receipt of the State Pension. The new State Pension was introduced in 2016. Legislation has also been introduced to increase the State Pension age (SPa) from 66 to 67 between 2026 and 2028 and to 68 from 2044 to 2046. As recommended in the 2023 State Pension age review, these increases will be retained, though the timing of the increase to age 68 remains under review (Neville-Rolfe, 2022; GOV.UK, 2023). The review also acknowledged the importance of continuing to regularly monitor State Pension age and financial awareness, particularly amongst vulnerable groups and young people, to support improvements and feed into ongoing communications and education activity. PPLL 2024 provides an opportunity to understand more about the extent to which people are aware of changes to the State Pension, including their State Pension age, as well as how their expectations of the State Pension may influence their decisions around when to retire.

Increased life expectancy and a later SPa necessitate that people continue working for longer, not only for the economic benefits working provides, but also the potential improvements to health and wellbeing (Neville-Rolfe, 2022). This in turn requires recognition of barriers that people may face to working in later life and that older workers may need additional support. Adults aged 55 to 64 are the ones most likely to be providing unpaid care for example (FRS, 2025) and may require flexible working arrangements to accommodate these caring needs. The gap in labour market participation between younger and older people has narrowed and the age at which people are leaving the workforce has increased (ONS, 2024). Nevertheless, many people leave the labour market before they reach State Pension age. In 2024, only 40% of 65 year olds were in paid work (DWP, 2024). PPLL 2024 provides evidence on how people’s expected age of retirement varies across the population as well as what people want from work as they get older and what might enable them to stay in the workforce for longer.

The private pensions landscape has also seen considerable changes in recent years. The introduction of Automatic Enrolment has led to a significant increase in the proportion of people with private pension provision (DWP, 2024). However, there remain gaps in pension coverage – for example for part-time and self-employed workers. Furthermore, increased pensions enrolment has not necessarily led to an increase in pensions engagement and may mean people are complacent about their workplace pensions (DWP, 2023). The move away from Defined Benefit (DB) to Defined Contribution (DC) pensions (The Pensions Regulator, 2024) along with the introduction of Pension Freedoms in 2015 - which allowed people to access their pension from age 55 and take a cash lump sum - has raised questions about whether people are sufficiently well informed and making the best decisions about how to access their pensions (The People’s Pension, 2021). The government has introduced a number of products and services such as Pension Wise and the Midlife MOT website to help people make informed choices. It is also seeking to introduce new policies to address specific issues such as the proliferation of small pension pots. However, questions remain about how aware people are of these services, their attitudes towards them and the likely take up. PPLL 2024 can shed light on this, as well as providing evidence on how people engage with and make decisions about how to access their DC pensions.

Finally, questions remain around whether people will have an adequate income to live on in retirement. The move from DB to DC pensions risks leaving people with less pension income than would previously have been the case (Lane, Clark and Peacock, 2022). The potential impact on retirement incomes of small pot sizes is further exacerbated by the risk of people taking the short-term decision to take a large proportion of their income as a cash lump sum rather than using it to purchase an annuity (The People’s Pension, 2021). The introduction of Automatic Enrolment in 2012 alongside a mandatory 8% minimum contribution from 2019 should help to increase pension pot sizes. However, the benefits of those arrangements will take time to be realised. Analysis from DWP, which assumes that pension holders convert all of their pension into an annuity, suggests that as many as 44% of people retiring in the 2030s will not reach their Target Replacement Rate (TRR, that is the percentage of pre-retirement earnings an individual would need to achieve to meet an adequate income in retirement After Housing Costs), although this will fall to 36% of people due to retire in the 2050s (DWP, 2023). A higher proportion of renters (47%) compared with home owners (37%) are predicted to not meet their TRR (After Housing Costs) (DWP, 2023). This is notable in light of declining rates of home ownership (see findings from the English Housing Survey) and the likelihood that a higher proportion of retired people in future cohorts will be in the rented sector. PPLL 2024 provides an opportunity to assess how realistic people’s expectations for their income in retirement are and who is/is not confident that they will be able to achieve an adequate standard of living in retirement.

Methodology

The Planning and Preparing for Later Life survey collected data from a nationally representative sample of 4,036 adults aged 40 to 75 in Great Britain. Data were collected via a 45 minute online self-completion survey (with the option to complete via the telephone on request) between 30 October and 7t December 2024.

The sample for the survey was drawn from respondents to the 2022 to 2023 and 2023 to 2024 Family Resources Surveys aged 40 to 75 who had agreed to be contacted for further research. The sample consisted of all 40 to 75 year olds who were sampled for FRS 2023 to 2024 between April and September 2023 as well as a random sample of respondents aged 40 to 75 who responded to FRS 2022 to 2023. A total sample of 14,069 individuals was invited to complete the survey. Responses were received from 4,036 individuals, 29% of the issued sample.

The data have been weighted to ensure that findings can be generalised to the population of 40 to 75 year olds in Great Britain. The final data have been calibrated against ONS mid-year population estimates and Labour Force Survey estimates to ensure that they closely resembled the target population in terms of sex, age and region.

Some of the questions in PPLL 2024 were also asked in 2020 to 2021 allowing for comparisons to be made over time. There is, however, a need for caution when looking at change over time given a change in methodology between 2020 to 2021 (when the survey was conducted solely on the telephone) and 2024 (when the survey moved online). Where the change in methodology may have particularly influenced the comparability of findings this is flagged in the report.

Further details of the survey methodology can be found in the accompanying Technical Report.

Data from the 2020 to 2021 and 2024 surveys are publicly available via the UK Data Service.

This report

Outline of the report

The report is divided into 5 substantive chapters covering: The later life landscape: This chapter sets the scene for the rest of the report. It presents:

- external evidence on the ageing population, employment patterns among older workers and trends in private pension participation to provide context for the PPLL findings

- headline findings from PPLL on the characteristics of the 40 to 75 population covered by the report regarding their working life and pension saving habits

- a discussion of the underlying economic and personal circumstances of the 40 to 75 population and how these may combine to influence retirement planning

- the results of a segmentation analysis which identifies 5 different groups within the 40 to 75 year old population with different levels of preparedness for retirement

Expectations for retirement: This chapter presents findings from the PPLL survey on:

- how important is the State Pension in people’s planning for retirement?

- what do people know about the State Pension, including their State Pension age?

- when do people expect to retire from paid work? Who is more/less likely to continue working beyond State Pension age?

Planning for retirement: This chapter presents findings from the PPLL survey on:

- when do people start planning for retirement?

- what information sources do they use to plan for retirement?

- how confident are people taking decisions about pensions?

- how actively engaged are people in managing their private pension?

Income adequacy in retirement: This chapter presents findings from the PPLL survey on:

- how confident are people that they will be able to achieve the lifestyle they want in retirement?

- how much money do people expect to need in retirement?

- how does this compare with what they expect their retirement income to be?

- how do people expect to fund their retirement?

- what is the role of housing wealth in retirement?

Pension decision making: This chapter presents findings from the PPLL survey on:

- when do people access their pensions?

- how do they access their Defined Contribution pensions?

- how confident are people in the decisions they make around accessing their pension?

- what appetite, if any, is there for pension providers to offer default options for accessing pensions?

The report is accompanied by tables which show the results broken down by demographic subgroups.

Caveats and limitations

This report contains bivariate analysis only. It considers how people’s experiences of and requirements around preparing for retirement may vary by characteristics including age, gender, retirement status, employment status, income, tenure and financial knowledge (see Chapter 2 for more on how these characteristics are defined). However, many of these factors will of course be interrelated. For example, women tend to have lower incomes than men and there is a positive association between income and financial literacy. Where a difference between men and women is observed, it is not possible to determine, from the analysis in this report, whether this difference is the result of differences in income or financial literacy between men and women or another factor. The data will be made publicly available via the UK Data Service for people wishing to conduct further analysis.

Retirement planning is closely related to age. PPLL findings, which apply only to those aged 40 to 75, may therefore look somewhat different to those from other sources which cover the whole adult population.

When discussing the association between income and pension planning, the focus is on respondents’ individual income from all sources (including, but not limited to, paid work). Focusing on individual income rather than household income or wealth may not fully reflect people’s overall economic circumstances or the resources they can utilise when planning for retirement. Nevertheless, given the focus of this report is on how individuals, rather than households, plan for retirement, findings are most commonly discussed in terms of individual income. A further breakdown of selected results by household income is provided in selected accompanying tables.

The information on pensions reported in this survey is based on individuals’ self-reports of the pensions they hold. It should be borne in mind that people may not know or be able to recall every detail of their pensions. PPLL is not intended to provide complete or precise estimates of people’s pension holdings. Figures presented here, for example regarding the number of pensions people hold or their pension pot size, may differ from data available from other sources such as from pension providers. Nevertheless, despite some possible inaccuracies in recall, the PPLL pensions data provide a valuable opportunity to evaluate how much people know/can report regarding their pensions and to explore how people’s pension saving may be related to a wide range of other factors including their personal, family and employment situation.

Reporting conventions

Where the report discusses differences between groups defined by a particular characteristic (such as age or sex) on a particular measure, or differences over time between 2020 to 2021 and 2024, the differences can be assumed to be statistically significant at the 5% significance level unless otherwise stated.

The statistical tests used in this report only allow us to identify whether the relationship between 2 variables is significant overall. Multiple tests of significance between different categories of a variable were not performed. For example, a passage which reports that saving increased with age may illustrate this by saying x% of 40 to 49 year olds had savings compared with y% of those 65+. The overall relationship between age and savings will have been tested for statistical significance but the specific difference between x% and y% will not have been tested separately.

Numbers quoted in the text or displayed in figures which combine 2 or more answer categories are calculated based on unrounded numbers and so may differ slightly from the rounded numbers shown in the accompanying tables. Don’t know and refusal responses are excluded from table bases unless otherwise stated. This may mean that the bases shown in tables for sub-groups will not always sum to the base shown in the total column. For the same reason, tables with the same base description, for example “All respondents” may include different numbers of respondents. Percentages less than 0.5% are shown in tables with a *. ‘-‘ indicates that no one selected that response option. Numbers shown in [ ] were calculated on a base size of less than 50.

2. Later life landscape

- 24% of 40 to 75 year olds were fully retired and 10% were semi-retired. From the age of 65, there was a sharp increase in the proportion of people who said they were fully retired (66% of people aged 65 to 69).

- 60% of people 40 to 75 in paid work said they wanted to work less as they approached retirement. When asked what would help them keep working longer, 46% of people who had not yet retired from paid work mentioned working fewer hours or being able to take more holidays.

- 75% of people aged 40 to 75 had a private pension. People on lower incomes, renters and with a long-term limiting health condition were less likely to have a private pension. 54% of people without a pension mentioned not being able to afford it as a reason for not having a pension.

- 38% of 40 to 75 year olds had no savings, while a further 2 in 10 (20%) had savings of under £15,000. 78% of social renters and 66% of private renters reporting having no savings, compared with 17% of people who owned their home outright.

- A segmentation analysis revealed 5 distinct groups with different levels of preparedness for retirement among the 40 to 75 population (including those already retired and those yet to retire). This included 14% of the population who were classed as “Secure and Confident” but also 16% who were classed as “Unprepared and financially vulnerable”.

This chapter provides an overview of the 40 to 75 year old population covered by this report, giving context for the rest of the findings. It highlights the long-term trends around the ageing population, older people in the workforce and increased pensions enrolment that shape the current later life landscape. It then goes on to discuss PPLL survey findings with respect to the experience of work in later life, including what people want from work as they get older and what might encourage people to remain in the workforce for longer. Next, it considers findings on private pension provision, who has a pension, what type, and how many. The chapter also considers the wider socio-economic and demographic characteristics of the 40 to 75 population and the range of circumstances – caring responsibilities, health, home ownership, financial literacy – that might influence retirement decisions and experiences.

The chapter ends by presenting the results of a segmentation analysis which identifies 5 different groups within the 40 to 75 year old population with different levels of preparedness for retirement.

An ageing population

The population is ageing (ONS, 2025a, 2025b). This trend is driven by increases in life expectancy as well as the baby boomer generation born in the 1960s reaching retirement age. Between mid-2022 and mid-2032, the number of people in the UK at State Pension age is projected to increase by 1.7 million, from an estimated 12.0 million to 13.7 million people (a 13.8% increase). In mid-2022, there were 6.1 million people aged 75 and over, making up 9.1% of the population. By mid-2047, this is projected to increase to 10 million, representing 13% of the total UK population. People aged 65 in 2023 can expect to live on average a further 19.8 years for males and 22.5 years for females. At the same time, declining fertility rates mean that there are projected to be fewer children in the population by mid-2032 and 2047 compared with 2022. These trends have implications for the future funding of the State Pension system as well as individuals’ thinking around retirement, when to retire, and how much they will need to fund their retirement.

Work in later life

People are now remaining in the workforce for longer. Although the employment rate among the 50 to 64 year old age group decreased between 2019 and 2023, the overall trend over the last 30 years was one of increased employment among this age group. The employment rate for 50 to 64 year olds stood at 70.9% in 2024 compared with 57.2% in 1995. The economic inactivity rate of people aged 65 has decreased over the last decade, from 72.8% in 2014 to 58.1% in 2024. The average age at which people exit the labour market is now at its highest since records began in 1984; 65.7 years old for men and 64.5 for women (ONS, 2024).

Alongside this general upward trend in older working people, it is important to bear in mind that people’s experiences can vary and that some groups may face greater barriers to working later in life. For example, people in low-paid and physically demanding jobs are up to 6 times more likely to leave the workforce due to ill health compared with those in managerial and professional occupations (TUC, 2021). At the same time, work is becoming more transient, as shown by the growth in the gig economy. This may exclude workers from pension provision altogether, or leave them with a more fragmented provision consisting of multiple small pension pots (DWP, 2024). Since 2018 UK workers aged 55-64 with long-term health conditions have become more likely to be economically inactive (Litsardopoulos et al., 2025). This section looks in more detail at people’s experiences of paid work in later life.

Employment and retirement rates

Data from the PPLL survey showed that nearly a quarter (24%) of people aged 40 to 75 were fully retired, and a further 10% were semi-retired[footnote 1].

People started to report being retired from age 50, with more initially considering themselves semi- than fully- retired (6% of people aged 50 to 54 semi-retired compared with 1% fully retired). From the age of 65, there was a sharp increase in the proportion of people who said they were fully retired, with 66% of people aged 65 to 69 saying this (compared with 19% who were semi-retired). A minority of people had delayed retiring until later, with 10% of 70 to 75 year olds saying they were semi-retired and a further 4% not retired (see Chapter 3 for more on people’s expectations around their age of retirement). (Table 2.01 and Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1 Retirement status, by age

| Age | Not retired % | Semi-retired % | Fully retired % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 40 to 44 | 100% | 0% | 0% |

| 45 to 49 | 100% | 0% | 0% |

| 50 to 54 | 93% | 6% | 1% |

| 55 to 59 | 77% | 14% | 9% |

| 60 to 64 | 55% | 21% | 23% |

| 65 to 69 | 16% | 19% | 66% |

| 70 to 75 | 4% | 10% | 85% |

Source: Planning and Preparing for Later Life Survey 2024

Base: All adults 40 to 75 (n=4,036)

The proportion of 40 to 75 year olds who said they had fully retired in 2024 (24%) was slightly lower than in 2020/2021 (27%). However, more people said they were semi-retired in 2024 (10% compared with 8%). (Table 2.01_Trend).

Most people aged 40 to 75 were in paid work, either as employees (52%) or self-employed (8%). The proportion of people in paid work started to decline from age 55, with only 72% of 55 to 59 year olds in paid work compared with 84% of 50 to 54 year olds. The proportion of 60 to 64 year olds in paid work was even lower at 54%. (Table 2.02 and Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2 Employment status, by age

| Age | Employee % | Self-employed % | Not working % | Fully retired % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 to 44 | 79% | 7% | 14% | 0% |

| 45 to 49 | 72% | 8% | 20% | 0% |

| 50 to 54 | 75% | 8% | 15% | 2% |

| 55 to 59 | 57% | 14% | 20% | 9% |

| 60 to 64 | 46% | 9% | 22% | 23% |

| 65 to 69 | 16% | 8% | 11% | 66% |

| 70 to 75 | 6% | 3% | 5% | 85% |

Source: Planning and Preparing for Later Life Survey 2024

Base: All adults 40 to 75 (n=4,036)

A sizeable minority of people aged 40 to 75 (16%) were not currently in paid work, but did not consider themselves to be fully retired. This group included people who were unemployed, in full-time education, or looking after the home as well as people who were economically inactive due to ill-health. Among those who defined themselves as semi-retired, around half (54%) were in paid work, including 18% who were self-employed, while the remaining 46% were not in paid work.

Of those not in paid work and not fully retired, the majority said they definitely (27%) or probably (45%) expected to return to paid work. This expectation was similar to that in 2020/2021 (66%). (Table 2.03 and 2.03_Trend).

Type of work

The majority of 40 to 75 year olds in paid work were employees. Only 16% of workers were currently self-employed. However, rates of self-employment increased notably from the age of 55 onwards. Around 1 in 5 (22%) people aged 55 to 59 in paid work were currently self-employed, rising to over a third of those aged 66 to 69 (37%) or 70 to 75 (38%). Self-employment may offer opportunities for people to keep working longer in life, with many potentially taking up new roles prior to full retirement. People who were semi-retired were especially likely to currently be self-employed – 37% compared with 14% of those not yet retired. The overall rate of self-employment among 40 to 75 year olds has declined since 2020 to 2021, when 20% were currently self-employed and 33% had at least some experience of self-employment, compared with 16% and 27% respectively in 2024. This decline may be related to a sharp drop in self-employment following the COVID-19 pandemic (ONS, 2022). (Table 2.04, 2.04_Trend and Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3 Whether people in paid work currently or ever self-employed, by age

| Age | Currently self-employed % | Ever self-employed % |

|---|---|---|

| 40 to 44 | 10% | 17% |

| 45 to 49 | 14% | 25% |

| 50 to 54 | 11% | 22% |

| 55 to 59 | 22% | 34% |

| 60 to 64 | 17% | 31% |

| 65 to 69 | 37% | 45% |

| 70 to 75 | 38% | 43% |

Source: Planning and Preparing for Later Life Survey 2024

Base: Adults 40 to 75 in paid work (n=1,984)

Overall, nearly two-thirds of people aged 40 to 75 in paid work were working full-time (64%). The proportion of people working part-time increased with age. Over two-thirds of 65 to 69 year olds (69%) were working less than 35 hours a week, while around half (52%) of those aged 70 to 75 were working fewer than 16 hours a week. Nearly all of those who were semi-retired worked part-time (92%) compared with less than a third of people who were not retired (31%). Women were more likely to work part-time (51% compared with only 22% of men), as were those self-employed. The higher rates of part-time working among the self-employed are consistent with the higher rates of self-employment among the semi-retired. (Table 2.05).

Around half of 40 to 75 year olds had jobs they described as either very (18%) or fairly (37%) physically active. There was no evidence that the proportion of people in physically active jobs declined with age. This suggests that many people are keeping physically active through employment in later life. (Table 2.06).

Most people in paid work (77%) reported being satisfied with their current work arrangements, including 33% who were very satisfied. Levels of satisfaction did not vary much by age, although the oldest workers (perhaps remaining in the workforce through choice) were the most likely to report being very satisfied with 57% of workers aged 70 to 75 saying this. Satisfaction with working arrangements had declined since 2020 to 2021. In 2024 33% said they were very satisfied compared with 44% in 2020/2021. (Table 2.07, 2.07_trend and Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.4 Satisfaction with current working arrangements 2020 to 2021 and 2024

| Age | Very satisfied % | Satisfied % | Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied % | Dissatisfied % | Very dissatisfied % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPLL 2020 to 2021 | 44% | 44% | 6% | 4% | 2% |

| PPLL 2024 | 33% | 45% | 16% | 5% | 1% |

Source: Planning and Preparing for Later Life Survey: 2020 to 2021 and 2024

Base: Adults 40-75 in paid work (2024: n=1,982, 2020 to 2021: n=1,241)

What do people want from work as they approach retirement?

This section looks specifically at what people aged 40 to 75 currently in paid work but not yet retired want from paid work as they approach retirement, and what might enable them to keep working for longer.

Most people (60%) said they wanted to work less than currently as they approached retirement, while only 3% said they wanted to work more. The proportion of people saying they wanted to work less decreased with age, with more people instead saying they wanted to work the same amount. This likely reflects the fact people approaching retirement had already reduced their working hours. (Table 2.08 and see Table 2.05).

The majority of people in paid work wanted to continue working for the same company as they approached retirement (62%). One in ten (10%) said they wanted to continue being self-employed, while a similar proportion (9%) said they wanted to become self-employed. This is consistent with the move towards self-employment among older, semi-retired workers described above. (Table 2.09 and see Table 2.04).

Around 1 in 4 (27%) workers said they would like to decrease their responsibilities in various ways as they approached retirement, such as taking responsibility for fewer tasks (18%). Among workers that did not indicate a desire to decrease responsibility, 16% said they would like to increase their responsibilities as they approached retirement, for example by managing more staff (9%) or larger projects (10%). People in the 40 to 44 age group – and furthest from retirement – were most likely to want an increase in responsibility. The findings point to the fact that different people may have different expectations and requirements of work as they approach retirement. (Table 2.10 and 2.11).

A quarter of people in paid work mentioned wanting to reduce the amount of physical activity in their job as they approached retirement, either by adapting their existing job (16%) or changing job (9%). The desire to reduce physical activity was particularly prevalent among those with a limiting health condition. This group were more likely to want to adapt their current job (24%), than those without a limiting condition (14%). Unsurprisingly, the more physically active a person’s current job, the more likely they were to want to reduce this activity as they approached retirement. However, still only 56% of people whose current job was very physically active wanted a reduction in physical activity as they approached retirement, with 38% wanting to adapt their current job and 18% wanting to change jobs. (Table 2.12).

When asked what would help them to work longer, people most frequently mentioned being able to work fewer hours or take more holidays (46%), closely followed by more flexible working (39%). Fewer people mentioned being able to take on a less demanding role (19%) or being able to access their pension while still working (19%). One in 4 (25%) said nothing would encourage them to work longer. Perhaps not surprisingly, this figure increased with age, with 37% of people aged 60 to 64 saying nothing would help them to keep working longer. This was also the case for 32% of people who were already semi-retired. (Table 2.13 and Figure 2.5).

Figure 2.5 What would help keep working longer before retirement

| Reasons | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Being able to work fewer hours or take more holidays | 46% |

| More flexible working | 39% |

| Being able to take on a less demanding role | 19% |

| Being able to access pension while still working | 19% |

| Your employer being actively supportive of your caring needs | 16% |

| Work-place adjustments for health condition or disability | 15% |

| Change in your employer or workplace attitudes towards older workers | 10% |

| None of the above | 25% |

Source: Planning and Preparing for Later Life Survey 2024

Base: Adults 40 to 75 not fully retired (n=2,474)

Note: Respondents could select more than one category so figures may sum to more than 100%

Pension provision

The introduction of Automatic Enrolment (AE) into a workplace pension led to a significant increase in the proportion of people with a private pension, specifically a workplace pension. The proportion of people with a workplace pension has stabilised in recent years but has increased significantly since the introduction of AE from 2012. Between 2012 and 2023, the number of employees enrolled in a workplace pension increased from 10.7 million (55% of eligible employees) to 20.8 million (88% of eligible employees) (DWP, 2024).

The move away from Defined Benefit (DB) to Defined Contribution (DC) pensions, which started in the mid-1990s as DB schemes became too expensive to support, has continued, The Pensions Regulator, (2024) estimates that the number of DB schemes has declined by an average of 3% a year since 2021. Data from the Wealth and Assets surveys shows that DC pensions generally provide less pension wealth than DB pensions (ONS, 2025).

Who has a private pension?

Data from the PPLL survey showed that three-quarters (75%) of people aged 40 to 75 in 2024 held a private pension. This proportion is similar to 2020/2021 (76%). People aged 40 to 49 (68%) were less likely to have a private pension than older age groups but otherwise there were not large differences observed by age. People aged 50 to 54 (81%) were the most likely to have a private pension. The level of private pension provision did vary significantly depending on people’s wider economic position. (Table 2.14):

- People who were self-employed (62%) or not working (42%) were less likely than employees (85%) – who have the benefit of automatic enrolment into a workplace pension – to have any private pension provision.

- Renters (55% of private renters and 48% of social renters) were less likely than those buying their home with a mortgage or who owned their home outright to have a pension (85% and 82%, respectively).

- People on lower incomes were less likely to have a private pension. Only around half (54%) of people with an income of less than £12,500 a year had a private pension compared with nearly everyone (95%) with an income of £53,000 a year or more.

- People with a limiting health condition were less likely than people without to have a private pension (58% compared with 81%).

Figure 2.6 Reasons for not having a private pension

| Reasons | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Can’t afford to pay into a pension | 54% |

| It’s too late to start a pension | 18% |

| Don’t know enough about pensions/not interested | 15% |

| Will rely on other sources of income in retirement | 15% |

| Don’t think will live that long | 12% |

| Not working at the moment/still in education | 11% |

| Don’t trust pensions | 6% |

| It’s too early to start a pension | 5% |

| Saving for something else e.g. buying a home | 4% |

Source: Planning and Preparing for Later Life Survey 2024

Base: Adults 40 to 75 without a pension (n=671)

Respondents could select more than one category so figures may sum to more than 100%

The strong association between a person’s financial situation and whether or not they had a pension is mirrored in the reasons people gave for not having a pension. The main reason given – mentioned by 54% of people without a pension – was not being able to afford contributions. This is the same as 2020 to 2021 when 53% of people without a private pension gave this as a reason. Older age groups also mentioned that it was too late to start a pension, with 17% of 55 to 59 year olds and 26% of 60 to 64 year olds giving this as a reason. (Table 2.15, 2.15_trend and Figure 2.6).

Nearly half (47%) of people with a private pension had a single pension. Nearly a quarter (22%) of people had 3 or more. This is a similar picture to 2020 to 2021. (Table 2.16 and 2.16_trend).

Types of pensions held

Workplace and personal pensions

Most people 40 to 75 with a private pension (85%) had a workplace pension. Workplace pensions were far more common than personal pensions, which were held by only 27% of private pension holders. Personal pensions were more common among older age groups. At least 1 in 3 pension holders aged 55 and over had a personal pension compared with only around one in ten aged 40 to 44 (12%). Conversely, younger age groups were more likely to hold a workplace pension, most likely following the introduction of automatic enrolment (see DWP, 2024). Nearly all private pension holders aged 40 to 44 (93%) or 45 to 49 (94%) had a workplace pension. (Table 2.17 and 2.18).

Figure 2.7 Proportion of pension holders with a personal or workplace pension, by employment status

| Pension | Employee % | Self-employed % | Not working % | Fully retired % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal pension | 21% | 60% | 29% | 32% |

| Workplace pension | 91% | 65% | 80% | 81% |

Source: Planning and Preparing for Later Life Survey 2024

Base: Adults 40 to 75 with a pension (n=3,208)

Self-employed people were 3 times as likely as employees to have a personal pension (60% compared with 21%). Employees (91%) were more likely than the self-employed to have a workplace pension. However, around two-thirds (65%) of self-employed pension holders had a workplace pension, presumably from a period of previous employment. (Figure 2.7).

There was no change in the proportion of pension holders with a workplace pension between 2024 and 2020 to 2021 (85%). However, the proportion of pension holders with a personal pension fell slightly, from 31% to 27%. (Table 2.17_trend and 2.18_trend).

Defined contribution and defined benefit pensions

Defined contribution (DC) pensions were much more common than Defined Benefit (DB) pensions. 72% of people aged 40 to 75 with a private pension had a DC pension, compared with 42% who had a DB pension. Consistent with the shift away from DB pensions, younger people were less likely than older people to have a DB pension. Only 27% of pension holders aged 40 to 44 had a DB pension, compared with 56% of 70 to 75 year olds. Conversely, 80% of pension holders aged 40 to 44 had a DC pension, compared with 59% of 70 to 75 year olds. Overall, the proportion of 40 to 75 year olds with a DC or DB pension is comparable to 2020/2021 (72% and 44% respectively, Table 2.19_trend and 2.20_trend, Table 2.19 and 2.20 and Figure 2.8).

Figure 2.8 Proportion of pension holders with a DB or DC pension, by age

| Age | DC pension % | DB pension % |

|---|---|---|

| 40 to 44 | 80% | 27% |

| 45 to 49 | 79% | 30% |

| 50 to 54 | 78% | 40% |

| 55 to 59 | 73% | 43% |

| 60 to 64 | 71% | 47% |

| 65 to 69 | 61% | 52% |

| 70 to 75 | 59% | 56% |

Source: Planning and Preparing for Later Life Survey 2024

Base: Adults 40 to 75 with a pension (DC pension = 3,039, DB pension= 2,987)

Figure 2.9 shows the mix of different types of pensions held by people. Around 1 in 5 people (19%) had a mix of DC and DB pensions. Relatively few people (8%) held multiple DB pensions. It was more common (26%) for people to hold multiple DC pensions. The mix of pensions held by people in 2024 looked very similar to the mix 90% of pensions held in 2020 to 2021, although there was an increase (from 23%) in the proportion with multiple DC pensions. (Table 2.21 and 2.21_trend)

Figure 2.9 Mix of private pensions held

| Pensions | Percentage |

|---|---|

| 1x DC pension only | 30% |

| 1x DB pension only | 18% |

| Multiple DC pensions (no DB) | 26% |

| Multiple DB pensions (no DC) | 8% |

| Mix of DB and DC pensions | 19% |

Source: Planning and Preparing for Later Life Survey 2024

Base: Adults 40 to 75 with a pension (n=2,862)

Current status of private pension

Fewer than half of people aged 40 to 75 with a pension and who had not yet retired (46%) were actively saving into a pension. The proportion of people actively saving varied by age and was highest (60%) among those aged 50 to 54. Employees were more likely to be saving (63%) than the self-employed (21%) or those not in work (4%). (Table 2.22).

Two-thirds (67%) of people aged 55 and over had accessed their pension. The proportion who had accessed their pension increased sharply between the age of 55 and 64. Only 33% of 55 to 59 year olds had accessed a pension, compared with 62% of 60 to 64 year olds. Chapter 6 looks in more detail at when and how people decide to access their pensions. (Table 2.23).

Pension size

The size of Defined Contribution (DC) pension pots varied considerably. Around 3 in ten people (31%) who had not yet accessed their pension had total pension savings of £100,000 or more. However, around 2 in ten (21%) had total pension savings of £10,000 or less. Larger pensions were more common among older age groups and, perhaps not surprisingly, among people with higher incomes. People with an income of £53,000 or more a year were almost 3 times as likely to have total pension savings of £100,000 or more than people with an income of less than £12,500 a year (61% compared with 21%). Men (40%) were more likely than women (21%) to have total pension savings of £100,000 or more. This is likely related to differences in employment (including higher part-time working among women) and income by gender, as described elsewhere in this chapter. (Table 2.24).

Most people (74%) who had not yet accessed their pension expected an income of less than £10,000 a year from their DB pension. (Table 2.25).

Figures presented here regarding the total value of people’s pension pots, or the income generated from DB pensions, are estimates only. Pension holders gave a banded estimate for the pot size/estimated income from each pension held. These estimates have been summed together using the mid-point of the relevant band to produce an overall estimate. Only 32% of pension holders consulted pension statements when providing figures. The figures provide an indication of what people perceive their pension holdings to be and which groups are likely to have more/less generous pensions. More precise estimates on actual pension size are available from other sources (see, for example, the Wealth and Assets survey).

Economic and personal circumstances

The next section of this chapter looks in more detail at different aspects of the economic and personal circumstances of people aged 40 to 75. This provides an insight into the experiences of people who have already retired as well as highlighting factors which might influence people’s planning for and decisions around retirement, including decisions around working in later life.

The findings highlight how many of these characteristics are interconnected, with, for example, a strong association between income and financial literacy or gender and income. These overlaps should be borne in mind when considering the findings presented throughout this report. It is not possible, from the findings presented here, to determine which, if any, of these characteristics specifically is driving the attitudes and behaviour reported on.

Economic circumstances

People who were semi- or fully retired tended to have lower incomes than people who had not yet retired. 34% of people who had semi-retired and 32% of people who had fully retired had an income of less than £12,500 a year, compared with 20% of people aged 40 to 75 who had not yet retired. Chapter 5 discusses income adequacy in retirement in more detail. (Table 2.26 and Figure 2.10).

Figure 2.10 Income, by retirement status

| Status | Under £12,500 % | £12,500 to under £32,500 % | £32,500 to under £53,000 % | £53,000+ % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not retired | 20% | 39% | 25% | 16% |

| Semi-retired | 34% | 37% | 19% | 10% |

| Fully retired | 32% | 50% | 14% | 3% |

Source: Planning and Preparing for Later Life Survey 2024

Base: All adults 40-75 (n=3,720)

Women were around twice as likely as men to have an income of less than £12,500 (32% compared with 16%). As discussed below and in Chapter 5, women were more likely to expect to be financially dependent on a partner in retirement than men. Focusing on individual income rather than household income or wealth may not fully reflect people’s overall economic circumstances or the resources they can utilise when planning for retirement.

Nevertheless, given the focus of this report is on how individuals, rather than households, plan for retirement, findings are most commonly discussed in terms of individual income. A further breakdown of results by household income is provided in selected accompanying tables.

The majority of 40 to 75 year olds were owner occupiers, either buying with a mortgage (30%) or owning their property outright (44%). The proportion of people who owned their own home was strongly associated with age. Nearly 8 in ten 70 to 75 year olds (79%) owned their own home outright, compared with around one in ten (11%) of 40 to 44 year olds. Although most people who were fully retired owned their own home outright (80%), not all retirees had the financial security afforded by home ownership. 6% of people who were fully retired were still paying a mortgage, while 14% were renting, either from a private landlord or social housing. (Table 2.27 and Figure 2.11).

Figure 2.11 Tenure, by age

| Age | Rent-free % | Social rent % | Private rent % | Buying with mortgage (inc. shared ownership) % | Own outright % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 to 44 | 2% | 9% | 28% | 50% | 11% |

| 45 to 49 | 0% | 19% | 15% | 50% | 16% |

| 50 to 54 | 1% | 15% | 8% | 46% | 30% |

| 55 to 59 | 1% | 17% | 9% | 30% | 43% |

| 60 to 64 | 2% | 16% | 6% | 15% | 61% |

| 65 to 69 | 1% | 10% | 5% | 8% | 76% |

| 70 to 75 | 1% | 11% | 6% | 3% | 79% |

Source: Planning and Preparing for Later Life Survey 2024

Base: All adults 40-75 (n=3,885)

Whether or not people have savings, in addition to or instead of any private pension provision, is likely to be important when it comes to how people fund their retirement and their expected standard of living in retirement (see Chapter 5). Overall, nearly 4 in ten (38%) 40 to 75 year olds had no savings, while a further 2 in ten (20%) had savings of under £15,000[footnote 2]. There was considerable variation in the level of savings people had. Older people were more likely than younger people to have savings. However, 24% of 65 to 69 year olds and 21% of 70 to 75 year olds had no savings. People who were renting – and thus did not have access to housing wealth – were less likely to have savings. 78% of social renters and 66% of private renters reported having no savings, compared with 17% of people who owned their home outright. Some of this difference may be explained by the fact that both savings and home ownership increase with age. However, it points to the potential financial vulnerability of renters. (Table 2.28 and Figure 2.12).

Figure 2.12 Total savings, by tenure

| Savings | Own outright % | Buying with mortgage (inc. shared ownership) % | Private rent % | Social rent % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No savings | 17% | 39% | 66% | 78% |

| <£15,000 | 16% | 27% | 23% | 16% |

| £15,000-£59,999 | 23% | 19% | 5% | 5% |

| £60,000-£99,999 | 14% | 4% | 1% | 1% |

| £100,000 or more | 31% | 10% | 5% | 0% |

Source: Planning and Preparing for Later Life Survey 2024

Base: All adults 40 to 75 (n=3,600)

Note: Savings exclusive of any private pension provision

Health, caring and dependants

Around half (49%) of 40 to 75 year olds reported having financial dependants. Around a third (36%) had children who were financially dependent on them, and just over 1 in 5 (22%) had a spouse or partner that was dependent on them. Men were more likely than women to have a spouse or partner as a financial dependent (36% compared with 8%). People under the age of 50 were especially likely to have children who were financially dependent on them. Chapter 5 looks in more detail at how reliant people expect to be on their partner’s income in retirement. (Table 2.29).

It was relatively uncommon for people who were semi- or fully retired to have a family member who was fully financially dependent on them. However, 7% of people who were semi-retired and 4% of people who were fully retired had at least one other person who was fully dependent on them. (Table 2.30).

Around a third of people (34%) aged 40 to 75 said they provided unpaid care to friends or family members, a small decrease since 2020 to 2021 (37%). Women (38%) were more likely to provide unpaid care than men (29%). Semi-retired people were more likely to be providing unpaid care (42%) compared with people who were not yet or fully retired (both 33%). It is not, however, possible to determine, whether both semi-retirement and caring are related to age or whether caring responsibilities influenced people’s decision to become semi-retired. People on lower incomes were more likely to be providing unpaid care, with 39% of people with an income of less than £12,500 doing so compared with 27% of those with an income of £53,000 or more. Again, it is not possible to determine the nature, if any, of a causal link between unpaid care and income from these findings. (Table 2.31).

People’s health status may affect their capacity to work and, therefore, their financial situation, as they approach retirement. Just over a quarter (28%) of people aged 40 to 75 reported having a long-term limiting health condition. The proportion with a health condition increased with age, with around a third (35%) of those aged 65 and over reporting a long-term limiting health condition. Women (33%) were more likely than men (23%) to report a health condition. People not in paid work (58%) were more likely than the self-employed (23%) or employees (19%) to report a health condition. Consistent with this association between employment and health, people on lower incomes were also more likely to report having a long-term limiting health condition. (Table 2.32).

Financial literacy

How well informed and knowledgeable people are about pensions and other financial matters is likely to be an important factor in how people approach planning for retirement. Chapters 3 and 4 look in more detail at people’s specific knowledge about pensions, including the State Pension. This section looks at people’s overall level of financial literacy, that is, their familiarity with financial concepts such as earning interest on savings.

A financial literacy score was calculated based on people’s answers to 3 financial questions. These questions were the same as those used in the Financial Conduct Authority’s Financial Lives survey, which assess understanding of basic financial concepts: calculating interest on savings, the effect of compound interest, and the impact of inflation on purchasing power of savings. Nearly half (48%) of people aged 40 to 75 got all 3 questions correct and were classed as having high financial literacy. This is higher than for the population as a whole (42% according to the 2022 Financial Lives survey). A quarter (25%) got none or only one of the questions correct and were classed as having low financial literacy. Levels of financial literacy varied considerably, with the following groups more likely to have high financial literacy. (Table 2.33 and Figure 2.13):

- Financial literacy was highest in the 55 to 59 and 60 to 64 age groups (55% of whom had high financial literacy). This is the group most likely to be faced with decisions around how to take their pension. Related to this, financial literacy was highest among the semi-retired, 65% of whom had high financial literacy.

- Men (58%) were more likely than women (39%) to have high financial literacy.

- People who were self-employed (56%) or employed (49%) were more likely to have high financial literacy than those not working (and not yet fully retired) (35%).

- Higher incomes were strongly associated with higher financial literacy. Most people with an income of £53,000 or more (82%) had high financial literacy, compared with 38% of people with an income of less than £12,500.

Figure 2.13 Financial literacy, by income

| Literacy | Under £12,500 % | £12,500 to under £32,500 % | £32,500 to under £53,000 % | £53,000+ % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low financial literacy | 34% | 27% | 18% | 5% |

| Medium financial literacy | 28% | 31% | 25% | 14% |

| High financial literacy | 38% | 42% | 57% | 82% |

Source: Planning and Preparing for Later Life Survey 2024

Base: All adults 40 to 75 (n=3,830)

When considering how attitudes and behaviour around planning for retirement vary between subgroups, it is important to bear in mind the associations between financial literacy, income, and other socio-demographic characteristics as described in this chapter. Based on the descriptive findings presented in this report it is not possible to determine which of these factors, if any, is the cause of any differences observed. The findings can point to associations only.

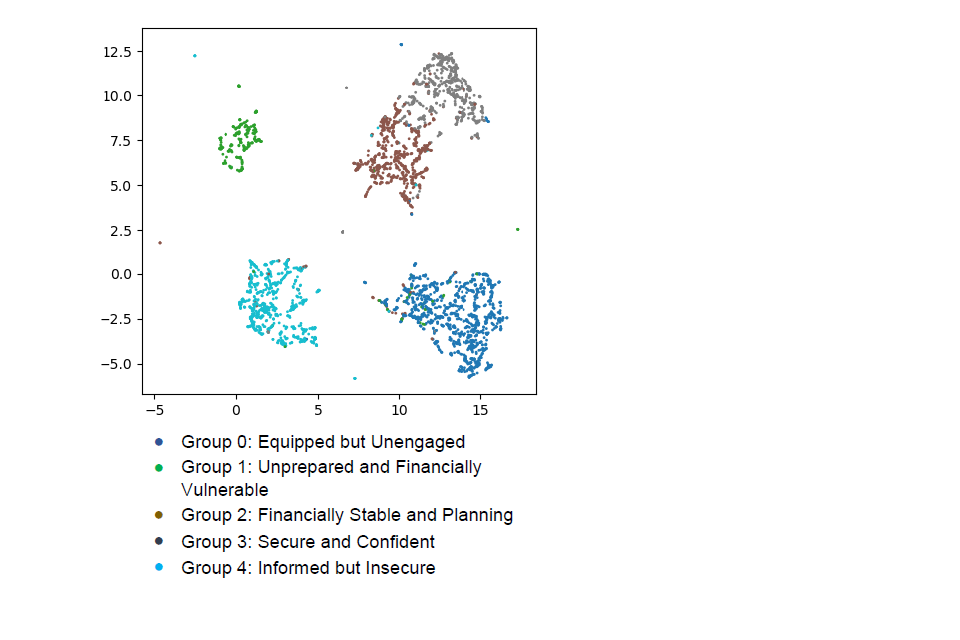

Preparedness for retirement: A typology

Planning and preparing for retirement is complex. How and when people plan for retirement, and their resulting expectations for and experiences of retirement will be influenced by many factors. To take account of how these different factors may combine to explain people’s level of preparedness for retirement, Partitioning Around Medoids (PAM) Clustering was used to divide the population into distinct groups or segments. This technique helps identify groups of people that are as similar as possible within each group and as different as possible between different groups, based on their responses to selected questions. Different models with different numbers of segments were tested. The final model was chosen based on statistical measures of how well the model fit the data and the interpretability of the resulting segments (see Technical Annex for more information).

Segments were defined using the following characteristics:

- current financial resources: Income, tenure, savings

- level of engagement with retirement planning: When they started saving for retirement, whether they reviewed value of pension in last 12 months, and whether they know the income they will need in retirement

- pensions knowledge: Self-assessed pensions knowledge, confidence in making pensions decisions, and objective financial literacy

- expectations for retirement: Confidence in being able to afford their desired lifestyle, whether they expect expenditure in retirement to go up/down, and reliance on State Pension/private pension as a source of income

The resulting segmentation can be used to identify those groups which may need additional support to successfully prepare for retirement, their relative prevalence in the population and the demographic profile of these groups.

Five distinct groups of people aged 40 to 75 were identified based on their level of preparedness for retirement:

- Unprepared and financially vulnerable (16%): This group had few financial resources at their disposal. They were likely to be renting, to have an income of less than £12,500 a year, and to have little or no savings. They expected to be heavily reliant on the State Pension in retirement and were generally not confident that they would be able to obtain the standard of living they wanted. Most had not yet started saving for retirement, and a high proportion had not thought about their income needs or expenditure in retirement.

- Informed but insecure (24%): Many of this group had started planning for retirement in their 20s to 40s. They had thought about their income and expenditure needs and had medium to high levels of financial literacy. However, this group was not confident in their ability to make decisions about pensions, and many rated their own pensions knowledge as patchy or basic. They were not particularly confident that they could achieve the standard of living they wanted in retirement and expected their expenditure to go up in retirement. This group was not renting, but many had no savings, and they were likely to have an income of less than £32,500 a year.