Understanding member engagement with workplace pensions

Published 30 January 2023

DWP research report number 1019.

A report of research carried out by Ipsos MORI on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP).

Crown copyright 2023.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence.

Or write to:

Information Policy Team

The National Archives

Kew

London

TW9 4DU

Email: psi@nationalarchives.gov.uk

This document/publication is also available on the GOV.UK website.

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email: socialresearch@dwp.gov.uk

First published January 2023.

ISBN 978-1-78659-494-5

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Glossary

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Automatic Enrolment (AE) | Under the Pensions Act 2008, every employer in the UK must enrol eligible employees into a workplace pension scheme and contribute towards it. Eligible staff are those classed as workers, aged between 22 and State Pension Age earning £10,000 or more per year. |

| Charge Cap | Limits the charges that may be paid by members in the default arrangement of pension schemes used for automatic enrolment. It covers all scheme and investment administration charges, excluding transaction costs. |

| Deferred pension(s) | A pension pot which members and their employer are no longer making active contributions to. |

| Defined Contribution (DC) | Contributions from members and their employers build up a pot of money which they can use to provide an income in retirement. |

| Financial Services Compensation Scheme | a scheme that protects customers from losing some of their money if an authorised financial services firms goes out of business. It protects up to £85,000 of savings per individual, per financial institution (not just per bank), and covers pensions, mortgages, insurance and investments. |

| Pension Provider | Commercial organisations that provide pension services to individuals and companies. |

| Master Trusts | A multi-employer occupational pension scheme that collectively manages pooled investments. Master Trusts enable employers and members to benefit from lower running costs (because the costs of services and fees are shared between larger number of employers and members) while still having the strong governance of a trustee. |

| Tax Relief on pensions | When part of the money an individual would have paid in income tax goes into their pension instead of being paid to the government. In the UK, pension tax relief is based on the individual’s contributions at the highest rate of income tax they pay. This means that the pension tax relief received depends on the individual’s income tax band. |

| Workplace pension | A way of saving for retirement which is arranged by the individual’s employer. |

Executive summary

This report sets out findings from qualitative research conducted by Ipsos into member engagement with workplace pensions. Sixty in-depth qualitative interviews were conducted with members who were saving into the default fund of their workplace pension scheme.

The research explored the understanding of and engagement with pensions amongst members who had been automatically enrolled into their workplace pension scheme. DWP were also interested in members’ responses to pension charges, including the clarity of charges and charging structures, and how members use that information.

Member engagement

Attitudes to pensions were characterised by detachment, fear and complacency, which acted as barriers to engagement.

Participants were not actively seeking information about their pension. However, they recognised the importance of information they were sent and engaged with it. Letters and other printed information about pensions were seen as being important and were likely to be engaged with. Emails were seen as being easily missed or disregarded. It was also important for information to be succinct and visually engaging.

A barrier to engagement with information about their pension was knowing how to assess what it meant for their future.

Pensions understanding and decision-making

In the interviews, participants understanding of their pension ranged from simply knowing who their provider was to knowing how much they had saved and what their future income projections were.

Participants trusted the decision their employers had made about which pension provider to use and felt it was safest to stay with the pension provider their employer had selected. Participants were concerned about losing their employer contributions if they changed pension provider.

Pension charges standardisation

Participants were shown an illustration of the current charging structures and found them hard to understand. They felt they would understand charges better if they were shown in pounds and pence rather than as percentages.

They were also asked to consider whether someone who found a pension provider with lower charges should switch. Participants felt it was better off to stay with their current provider to ensure they retained their employer pension contributions.

Consolidating deferred pots

Barriers to consolidating deferred pots were knowing whether or not they could; fear of scams; not knowing information about their deferred pensions; not knowing how to consolidate; believing it would be hard work or not understanding the benefits of consolidation.

Those who had consolidated deferred pots had been prompted to do so, either by a new pension provider, contact or reading about it online.

When presented with two options for consolidation, either deferred pots being put into a government approved service or being consolidated into a new pension with their current employers, participants were happy with either option as long as they were reassured about the security of the new pension and process for transferring their funds.

Encouraging member engagement with pensions

This research found that the following could help motivate people to engage with their pension:

- ability to interpret what information about their pension meant for their future and what impact making changes could have

- ability to influence their pension outcomes

- understanding the benefits of engagement

- ability to view information about their pension easily

Low understanding of pensions amongst participants suggests that increasing understanding of pensions in an important first step to set information on pensions charges in context. This could also increase member engagement, by helping to reduce feelings of fear and confusion in relation to their pension.

Authors

This report was written by researchers in the Ipsos Social Research Institute:

Joanna Crossfield, Research Director

Ayesha Lynn-Birkett, Senior Research Executive

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Grace Cassidy, Christopher Lord and Rob Hardcastle from DWP for their support and guidance during the design and conduct of this study.

We could not have carried out this research without the collaboration from the participants who shared their experiences, for which we are grateful.

Introduction

Ipsos were commissioned to carry out qualitative research on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP). The aim was to explore the current understanding and level of engagement members who have been automatically enrolled in their workplace pension scheme had with their pensions. DWP were also interested in members’ responses to current pension charges and proposed changes in this area.

The findings in this report cover the following areas:

- Current member engagement

- Pension understanding among members and decision-making influences

- Responses towards pension charges and potential standardisation of charging

- Current member behaviour towards small and deferred pension pots

- Recommendations to aid member engagement.

Background

Since its introduction in 2012, Automatic Enrolment (AE) has led to a significant increase in the proportion of employees who are saving for their retirement. By 2021 around 10 million people had been auto enrolled and were saving for their retirement[footnote 1], including many who previously had no pension savings.

Almost all people saving in a workplace pension scheme are invested in the default fund of their pension scheme and have not personally chosen how their pension is managed or invested[footnote 2]. For the vast majority of pension savers, engagement with pension products and financial literacy is very low.

As well as encouraging people to save for later life, DWP is committed to ensuring that pensions members get good value for money from their pensions savings. This is particularly important for lower earners, those who move in and out of work and those who change jobs frequently, as their pension pots will be smaller.

One measure the Government has introduced to help improve outcomes for members is the charge cap, which seeks to protect members from unfairly high charges. For those invested in the default funds of defined contribution workplace pension schemes used for automatic enrolment, scheme and investment administration charges can be a maximum of 0.75% of the funds under management. Previous research has found that the average administration charge for these funds is around 0.5%[footnote 3]. There are currently three permitted charging structures within the cap:

- a single percentage charge

- a combination of a percentage charge on each contribution and an annual percentage charge of funds under management

- an annual flat fee and a charge of an annual percentage of funds under management

The government sought evidence on a proposal for a single permitted charging structure as part of the 2021 Permitted Charges in DC Pensions consultation. The aim of the proposal was to contribute to increasing transparency and comprehension of charges and support members to compare pensions, and exercise choice if they wished. That consultation provided many useful insights; however, a broader evidence base was needed to support ongoing policy thinking in this area.

Evidence on pensions members’ knowledge and understanding is currently limited, but DWP hypothesise that better engagement will lead to better decision making and outcomes for members.

DWP commissioned Ipsos to supplement the existing evidence base with insight into how members view their pension, the extent to which they are likely to engage with their pensions savings and what could best support this engagement. Evidence was also required on what members understand about the current charging structures; what they understand about the proposal for charges standardisation and what the behavioural responses may be.

Research aims and objectives

To build DWP’s evidence base on member engagement and identify motivators or barriers to member engagement with their pensions.

To understand how members might make decisions, including switching or accessing guidance, and identify where members may need further support and guidance.

To outline how members respond to charges standardisation and identify benefits, barriers and comprehension.

Methodology

Methodology and sample

Ipsos conducted 60 scenario based semi-structured depth interviews either online (using Microsoft Teams) or over the telephone.

Sample design

All participants were currently saving into the default scheme of a Defined Contribution pension with their current employer. Minimum quotas were applied on age, gender, financial confidence and salary to ensure people from a broad range of circumstances were interviewed.

| Quota | Subgroup | Number of interviews |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 32 |

| Gender | Male | 28 |

| Age | 22 - 30 | 19 |

| Age | 31 - 40 | 24 |

| Age | 41 - 50 | 17 |

| Income | Up to £25k | 18 |

| Income | £25k – 40k | 27 |

| Income | £41k – 55k | 9 |

| Income | Over £55k | 6 |

| Pension provider | Master Trust - NEST, The People’s Pension, NOW: Pensions | 27 |

| Total number of interviews | 60 |

Interviews took place between the 25 October to 26 November 2021 and lasted up to 60 minutes.

Participants were recruited using free-find methods. As is standard practice in qualitative research, they were offered a gift of £40 to thank them for sharing their time to contribute to this study.

A full sample table can be found in Appendix A.

Fieldwork

The interviews were guided by a topic guide, agreed with DWP in advance to ensure the areas of interest were covered:

- members’ general confidence in managing their money and finances

- how members were saving for retirement

- members’ current engagement and understanding of their pensions

- members’ confidence in investigating different pension providers and whether they have ever changed their pension provider

- desired information about pensions

In addition to the semi-structured discussion, the interview included an exploration of three hypothetical scenarios relating to pensions charges and options for automatic consolidation.

Scenarios were used to help explore situations that participants might find difficult to discuss. We knew from our previous research on this topic that people would have little knowledge of the mechanics of how their pension worked. Therefore, direct questioning on the topic of charges would have been unlikely to elicit sufficiently detailed information on attitudes towards these. Using scenarios enabled the research team to illustrate the circumstances and impact on an individual, without requiring the participant to know what charges they were paying.

We also conducted short follow up interviews with a proportion of participants to understand what they recalled from the interview and if they had taken any action as a result.

Analysis

Data management was conducted using the Framework Approach, supporting comprehensive thematic analysis. Thematic code frames were used to systematically summarise the full dataset which included detailed interview notes for each interview. Regular team discussions to facilitate data analysis were held throughout the fieldwork period, a crucial component of any qualitative methodology which also supported the data management process.

Note on qualitative research

When considering these findings, it is important to bear in mind that a qualitative approach explores the range of attitudes and opinions of participants in detail. It provides an insight into the key reasons underlying participants’ views. Findings are descriptive and illustrative, not statistically representative.

Member engagement

This chapter sets out participants’ attitudes towards their workplace pension and how they engaged with information they were sent about their pension.

Chapter Summary

Pensions, specifically workplace pensions, were the main way in which participants in this sample were saving for their retirement. However, they had little understanding of what this would give them at retirement.

Attitudes to pensions were characterised by detachment, fear and complacency which acted as a barrier to engagement.

Participants were unlikely to actively seek information in relation to their pension. When they were sent information they recognised it was important and engaged with it. Of the regular information they were sent about their pension, participants were most likely to engage with tangible information, that is letters and other mailings, which were succinct and to the point. In contrast, information sent by email was easily disregarded. Participants who had access to information about their pension through their online banking app reported that this supported them to engage regularly with their pension savings as they saw it every time they logged in to their online banking.

Motivation to proactively engage with information about their pension was low. Participants could understand the information they were given about their pension but did not know what to do with it. They were not able to assess whether or not what they had saved was a ‘good’ amount; what their monthly savings would mean when they went to claim their pension; what impact saving more would be or what impact retiring earlier or later would have. This acted as a barrier to engagement.

To encourage people to engage with their pension, they need to be able to understand what their current savings mean for their future and what impact making changes could have.

Findings

Role of pension in retirement saving

For many participants, their pension was the main way they were saving for retirement. Other ways people were saving for retirement were funds from rental property, expecting to have paid off their mortgage, downsizing, expected inheritance and general savings. Those in couples considered their joint income, factoring in their partners pension as well as their own. Women were more likely to mention this than men. The State Pension was also a factor in people’s retirement savings plans.

However, although people were saving into their pension for retirement, many were doing so by default and had very little to no knowledge on what this would mean for them at retirement age.

Male, 30:

I don’t really know if it’s just the money I’ve invested that’s built my fund up or whether it’s something they’ve done that’s moved it up. I don’t really know or understand that.

Female, 47:

When the kids do finally move out, we’ll move out and downsize. I won’t be pushing them out, but that’s the plan.

Attitudes towards pensions

The interviews found that participants attitudes towards their pensions were characterised by detachment, complacency and fear. These attitudes acted as a barrier to engaging more with their pension.

Detachment

Participants had little sense of ownership of their pension. It did not feel like their money as it was taken at source, before they saw it in their bank account.

Even participants who were highly engaged with their wider finances demonstrated low engagement with their pension. This acted as a barrier to engagement as lacking a sense of ownership of the money in their pension meant participants lacked motivation to engage with it.

Female, 29:

All I know is that I pay into it and so does my employer, and that’s it. I don’t know what happens to that money.

Female, 34:

I don’t have a clue what they actually do with my money. I mean, I don’t think it’s like real money at this point. Until you actually get that money at retirement, it just doesn’t feel like real money. I guess it goes into a magical pot, who knows where it goes?

Complacency

Participants who demonstrated this attitude were satisfied knowing that they were enrolled in a pension and that payments were being made. They rarely thought about their pension. They trusted that their employer would have chosen the best and most suitable scheme for its employees. These participants placed their trust regarding their pensions with their employers. This acted as a barrier to engagement as participants could not see what they would gain from engaging more with their pension.

Male, 30:

[My pension] doesn’t really feel like it’s yours, almost. It is, but… you don’t see it as a bank account that’s building up… I just see it as something I’ll receive in later life… I just see it as a pot of money that almost like the Government’s holding for me.

Female, 27:

It was all set up by the company I work for, so I was just put in it. I know I pay an amount each month. I really don’t know much more than that - it’s really for when I’m much older.

Fear

Participants recognised that their pension was very important which led to a sense of concern and risk about losing it. Members’ fearful attitudes towards their pensions manifested in two ways. They were concerned about their pension being compromised through fraud or being lost if their employer went out of business. This was heightened by high-profile stories in the media about the collapse of pension schemes or people losing their pension if their employer went out of business. Participants were not aware that as a Defined Contribution scheme holder their pension was separate to their employer, nor that their scheme was protected by the Financial Services Compensation Scheme.

This led to fear of making decisions about their pension or being in control of it. They were worried about making a decision which could lead to them losing their pension, either directly or by being over-charged for something. This loss aversion then acted as a barrier to engaging with their pension.

Male, 30:

It’s not like you’re investing a grand, is it? You’re investing a lot of money into what potentially is your future… and it’s quite a scary proposition… when you’re talking that much money and to add risk into it sounds even more scary. But on the flipside, I don’t think the current scale I’m at is going to take me to what I would need in retirement. So it’s something I need to consider but, almost out of lack of understanding, I don’t approach it.

Engagement with information about their pension

Participants were unlikely to be actively seeking information about their pension. Participants who had sought information about their pension referred to talking to family and friends, colleagues or looking on the Money Saving Expert website.

Whilst participants were unlikely to actively seek information about their pension, they did engage with information they were sent, as they recognised this information was important.

Participants in the research remembered receiving different types of information from their pension provider about their pension. There was variability by pension provider and what was recalled by participant. Across the sample, participants recalled being sent information through:

- an introduction or welcome pack

- an annual statement

- monthly emails

- quarterly magazines

- summary statements

- having an online account and / or having access through their online banking app

Those who recalled receiving the welcome pack said that they filed it away after receiving it. Participants felt reassured to receive something which confirmed they were saving into their pension but could not remember reading this in detail nor the information which was in it.

The annual statement was the most strongly recalled piece of information among participants. Participants recognised that this was important and reported opening these to skim read what they felt was ‘key’ information. This was: their monthly contribution, its current value and projection. Participants who were most engaged with their pension and most confident about their ability to interpret the information in it had noticed information about charges. However, in the interview this was not the information which they most strongly associated with the annual statement. Participants would then file the statement away.

Female, 28:

I tend to just get the letter and it goes straight in my folder with all the pension information, but I’ve not chosen to read too much into it.

Those who recalled receiving monthly emails were unlikely to engage with these. These participants felt that the email was too easily passed over, especially if it was delivered to their work email address and arrived when they were busy. In addition, monthly communication felt too frequent.

Participants who received a quarterly magazine reported finding this quite long and overwhelming and too detailed to engage with.

Male, 38:

I did briefly look at the magazine [from my pension provider], but I’ve no real clue what it said. It’s [the pension] on the back burner, it does what it does. I do have a statement somewhere, I really don’t look at it very much.

In contrast, those who received regular summary statements of between two and three pages found these easy to engage with and digest.

Engagement with the online account varied. Gaining access and setting up a password was seen as hard work, which created a barrier to engagement. Losing or forgetting login details was also a further barrier to using this channel as an ongoing source of information. These issues meant that if the online account was the only source of information, participants who did not know how to log in risked not receiving any information at all. Those who did log in reported being pleasantly surprised by how accessible the information was. However, there was a lack of motivation to log in to the online account amongst participants as they did not know what information they would find or what they would need to do with it.

Participants whose bank was linked with their pension provider (for example, a bank account with Lloyds and a pension with Scottish Widows) reported seeing their pensions savings alongside their bank balance in their mobile banking app. Participants were checking their mobile banking regularly (for example, daily) and saw their pension balance every time they did so. Participants in this situation reported that this helped them feel more connected to and aware of their pension and increased their sense of ownership over it.

Life stage influenced how engaged participants were with any pension information received. Older participants, as well as those with dependants, reported wanting to feel more informed about their pension and were likely to engage more with the information provided. Younger participants spoke of retirement feeling ‘ages away’ with emphasis on wanting information and knowledge on closer milestones such as taking out a mortgage. Women were more likely than men to see pensions as being less relevant at the present time. This was particularly the case for those with young or school-age children who tended to be more focused on immediate financial concerns, for example whilst on maternity leave or paying school fees.

Female, 27:

It doesn’t really figure for me, apart from seeing it every month on my wage slip. It’s because I’m still young and it’s not something I’m thinking about until later on in life. Perhaps when I’m older I’ll think about it a bit more, but I don’t know when that would be.

Shorter communications were more likely to be engaged with. Participants expressed a preference for succinct information presented in a visually appealing way. They described being prepared to spend between two to five minutes engaging with the information about their pension.

Participant motivation to engage with information about their pension

Participants recognised that engaging with information about their pension was important. Reasons participants described for engaging with information about their pension included:

- checking that salary deductions had been paid in

- checking their employer contributions had been paid in

- seeing how much money had been built up so far

- seeing their projected future income

- curiosity

Female, 29:

I definitely logged on (to my pension account] when I started back at work part time. But I just like to have a look, I’m inquisitive.

Participants who were motivated to look at their pension information to see how much they and / or their employer were paying in were particularly motivated to do so after a pay rise or promotion.

Male, 41:

I would go on [to my pension online account] to look if my wage had gone up or was changing. I’d want to make sure that what’s taken is what’s going in.

Male, 34:

Online (access) is very useful as I can access it at the drop of a hat. I went and checked it last payday, to see what had happened with my new salary. I would say it is interesting, but not vital to have online (access), because retirement feels like a long way away.

However, overall motivation to engage with information about their pension was weak, reflected in a tendency not to actively seek information and not look deeply at the information they were sent. As set out earlier, participants had emotional barriers to doing so, such as detachment, complacency and fear and lack of confidence in their understanding of pensions. These factors combined to predispose them to believe that information about their pension would be difficult to understand and ‘wordy’ and/or ‘jargon-filled’. This created a sense of feeling overwhelmed or confused when looking at information about their pension.

There were examples of higher engagement and curiosity about pensions. These participants had looked into their pension but still lacked confidence in their understanding and felt that they did not have much knowledge about their pension. They also found information about pensions jargonistic. However, they were interested in finding out more. This higher engagement was idiosyncratic and determined by the individual’s personality and interests.

Whilst participants could understand the information presented to them about their pension, they did not know what to do with it. They did not know:

- how to assess whether what they had saved was enough or was a ‘good’ amount

- what their monthly savings would mean in real terms when they came to claim their pension

- what the impact on their savings, and income in retirement, would be if they decided to retire earlier or later

- what the impact of saving more would be

Participants could see the projection in their statement but did not know how to interpret this or what it was based on. For example, they wondered whether it assumed their salary, and therefore contributions, would remain the same for the rest of their working life or whether it assumed any annual increases.

Male, 50:

I’ve kept the investment in the recommended fund, it’s low risk with smoothing in the later years. I never like to fiddle with it, I don’t know enough, I like to play it safe. So, I don’t look at it much, it doesn’t change that much.

Overall, engaging with information about their pension could be a negative experience for participants. It could confuse or scare them and they did not know what to do with the information. This weakened motivation to engage.

Female, 32:

Unless I was going to increase my payments, I don’t know what else I would use it for, because I’d just be looking at money that I couldn’t access.

Participants needed a clear purpose for engaging with information about their pension and to feel confident that they understood it and knew what to do with it. Equipping people with the ability to understand what their current savings meant for the future or what the impact of making changes could help create motivation to engage.

Pensions understanding and decision-making

This chapter sets out participants’ understanding of their pensions and attitudes towards switching providers.

Chapter Summary

Understanding of pensions, both of their own pension and how pensions work in general, varied across the sample. Overall, participants felt that they had low understanding both of their own pension and how pensions worked. When asked to describe the specifics of their pension and how pensions work this was shown to be the case. Those with the lowest understanding knew just that they had a pension and that they couldn’t take it out until a particular age.

There were pockets of higher engagement and therefore deeper understanding about pensions. These participants knew that the money held in their pension is invested, not held in a bank account and that there are different risk levels which influence how the money is invested.

Participants had not considered switching pension provider and were not receptive to doing so. They trusted their employer to have researched the pension provider they chose on their behalf and it felt safer to stay with this choice. Participants also expressed concerns about losing their employer pension contributions if they changed provider.

Findings

Knowledge about pensions

Participants had very low confidence in their knowledge about pensions and felt they knew nothing about them. This acted as a barrier to engaging with their pension or making decisions about it, as they were worried about making a mistake and suffering negative consequences.

In the interviews participants were asked to describe what they knew about their pension and the moderator probed on different elements of pensions. In response to this, expressed knowledge was low.

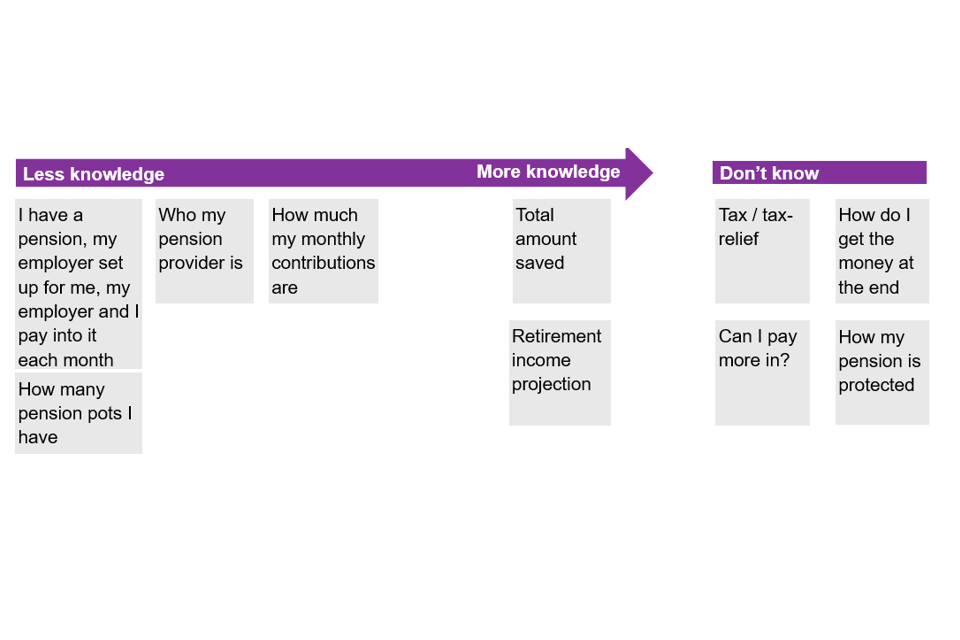

Figure 1.1 Overview of knowledge about pensions

Those with the least knowledge about their pension knew that they had a pension which their employer had set up for them, which they and their employer paid into every month. There were participants who did not know how long they had been paying into a pension for or who their pension provider was. Participants with more than one pension knew this, although it is also possible that there were people in the sample who had pensions they had lost track of.

Male, 34:

I can’t remember who they are (pension provider). The name that pops into my head is Domestic and General, but I can’t really remember. I might be getting confused, they might be for my life insurance.

Those who knew a little more knew who their pension provider was, in addition to this information.

Those with more knowledge again knew how much their monthly contributions were. Those with the most knowledge in our sample knew the total amount they had saved and what their projection for retirement income was.

Female, 47:

I know how much goes into it from my salary every month. I don’t know how much the whole thing is worth.

Participants in our sample did not talk about how their pension was protected, what the tax arrangements were on their pension or how they would get the money when they came to retire. They asked questions about these in the course of the interview.

Male, 38:

When I retire, how I actually get the money, that’s not so clear.

Understanding about how pensions work

Participants also had low understanding of the mechanics of pensions.

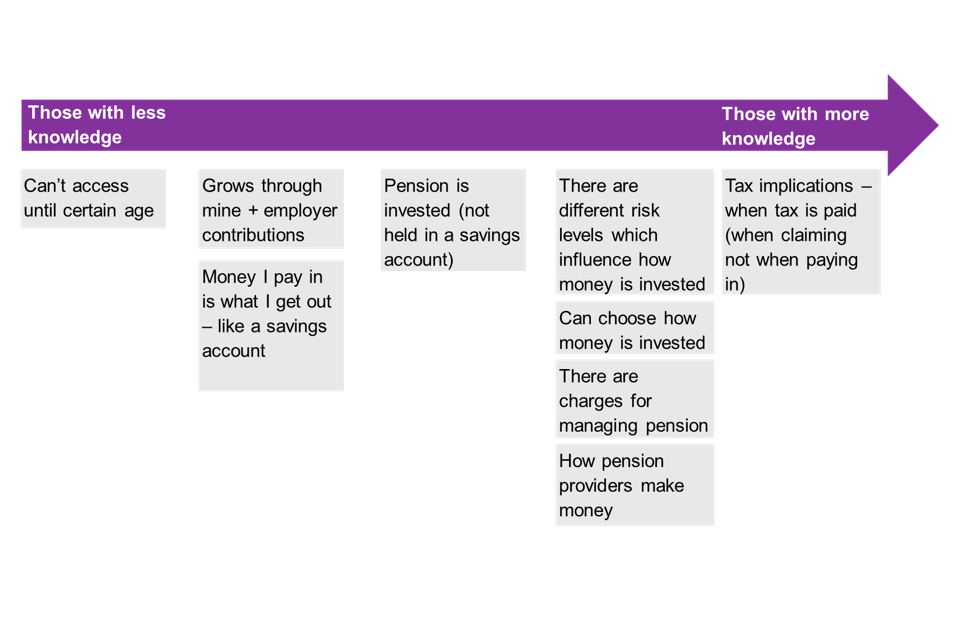

Figure 1.2 Overview of understanding about how pensions work

All participants understood that they could not access their pension until a certain age, although there was not a consistent understanding of what this age was.

There was confusion about how pensions grow. Those with the least understanding believed that pensions grow like a savings account or through contributions from themselves and their employer. These participants believed that they would get out what they paid in.

Female, 23:

It just seems like it’s kind of a bit like a bank… so that’s just me assuming, to be honest.

Female, 29:

What do they do with the money? I have no idea. Maybe they invest it? That’s all I can think of, but I really don’t know… I think they just pay the pension when you get to retirement, I don’t think you get a bonus. If I pay that money in, that’s what I get back.

Male, 34:

I think they just hold it until I reach retirement age and I’m entitled to it. Beyond that, I don’t think anything happens to it…I assume it would adjust for inflation. I’m not sure if it would actually grow. I guess it would depend on inflation, in line with the government?

Those with more knowledge understood that pensions are invested, rather than being held in a savings account.

Female, 44:

I might be completely wrong, (do) they invest it in stocks and shares or something, maybe… My dad’s private pension is invested privately. I think sometimes … it fluctuates, maybe, if that’s the right understanding?

Male, 30:

I don’t really know if it’s just the money I’ve invested that’s built my fund up or whether it’s something they’ve done that’s moved it up. I don’t really know or understand that.

Those with the most knowledge about how pensions work understood that there are different risk levels which influence how the money is invested; that they can choose how they money is invested and that there are charges for their pensions being managed.

Female, 31:

I’m not sure entirely how they grow my pot. I think they invest it in different funds, and that where the risk comes in. So, the funds the money is in might gain or lose, that’s the risk.

Participants had given little thought to how their pension worked, in part because they believed it was beyond their ability to understand. This meant they had not considered whether they would be charged for their pension and therefore, what good value for money from a pension would mean. When prompted to think about it during the interview they realised that there would be charges for managing their pension.

Attitudes to switching provider

Participants had not looked at other pension providers nor considered changing provider. Neither were they receptive to this idea when discussion in the interviews.

Participants knew that there were other pension providers who they could use but had typically not considered whether or not they could change provider. The primary barrier to switching pension provider was lack of understanding about what the benefit would be for them.

Decisions about their pension and pension provider were seen as significant ones which would have a long-term impact on them. This enhanced participants’ sense of the risk attached to decisions about their pension provider, making them more risk averse.

As such, they felt it was safest to remain with the provider their employer had chosen. They trusted that their employer had much more understanding of pensions than them and would have researched the available options to make the best decision on their behalf. Opting out of this felt risky, particularly as they believed themselves to have very little understanding of pensions. Some participants also worried about offending their employer by opting out of their workplace pension as they felt this could suggest they did not trust them. There was no evidence that participants had ever discussed switching pension provider with their employer nor that employers had tried to influence people one way or the other.

“Given that the company chose the pension and I tend to think they know more about it than me. They’re a large company and I like to think they know what they’re doing…I think overall the package is good, the performance is good, I can increase my contributions, as I have done and there’s a good rate going in from my employer.” Male, 50

Female, 23:

I’ve not really looked into it. I feel like I kind of would just go along with whatever pension the job gave me.

Female, 49:

I feel more secure that it is through work, rather than a separate one. You hear stories about people losing the money.

Female, 33:

Your company is making sure that you’ll be ok when you retire, it’s almost like rewarding you for a service. I would feel like if I set up one myself it’s like my employer would be evading their responsibility - I would be doing something that they should be doing for me.

Participants also worried about losing their employer contributions if they switched pension provider. Employer contributions were an important part of the reason why individuals were saving into their workplace pension and they did not want to lose these.

Female, 29:

I’m saving with Nest just because of the convenience - they were chosen by my employer. But I’d need to know if my employer would pay into any other pension. If they would do that, I’d certainly consider it (switching pension provider).

Male, 34:

I’d be reluctant to change my pension - you’re better off if the company contributes.

In addition to these risks of switching provider, participants also demonstrated a strong bias towards the status quo. They believed that changing provider would require a lot of effort on their part, such as researching providers and that they may also need support, for example from an Independent Financial Advisor or a knowledgeable friend or family member. Participants did not know where they would go for this information as they had not considered it before the interview. Because of their perceptions of the risks of switching pension, participants were unwilling to undertake the level of activity they thought it would require.

In the discussion about changing provider, participants with lower understanding about pensions demonstrated a further lack of understanding. They referred to considering taking an additional pension which they felt would be their ‘own’ pension, rather than a workplace pension which they already had. This demonstrated a lack of understanding of defined contribution pensions, what they can or cannot do with their workplace pension and the drawbacks to having multiple pensions. These participants did not understand that the money in their pension is their own, belongs only to them and is protected. Nor did they understand that having multiple pensions would mean paying charges on multiple pots.

Participants who were motivated to switch provider were those who were most highly engaged with their pension and had most understanding. This group, consisting only of men, were motivated to consider switching provider by the potential to have more control over their pension, for example to switch to a provider which offered a greater choice of the funds their pension was invested in.

Reluctance to switch provider was, therefore, not about the ease or difficulty of comparing providers it was about individuals’ lack of confidence about their understanding of their pension and high confidence in the decision that their employer had made on their behalf.

Pensions charges standardisation

This chapter sets out findings on customer responses to pensions charges standardisation. Presently, administration charges for members invested in the default funds of defined contribution pension schemes set up under automatic enrolment can be a maximum of 0.75% of the funds under management. Previous research has found that the average administration charge for these funds is around 0.5%[footnote 4]. There are currently 3 permitted charging structures within the cap:

- a single percentage charge

- a combination of a percentage charge on each contribution and an annual percentage charge of funds under management

- an annual flat fee and a charge of an annual percentage of funds under management

This section explored customer responses to the proposal to have a single charging structure and what this might be.

Chapter summary

Participants were shown a fictional scenario based on the current permitted charging structures to illustrate the different charges people could pay on their pension.

The information about charges was sometimes new information to participants. They had not considered what happened to the money that was in their pension and thought it was the same as the money in a savings account. In the sessions, participants came to the understanding that the pension providers made money to provide the service and so they would be charged for holding and investing their money with them.

Participants found it hard to understand current charging structure and from the three options shown could not work out who would pay more or least, nor that they would pay about the same. They felt that they would understand charges shown in pounds and pence better than charges shown as percentages.

A second scenario set out an individual finding a pension provider with lower charges and invited participants to consider whether they should switch or stay with their current provider. Participants felt that the individual was better off staying with their current provider to ensure they retained their employer’s contributions to their pension.

Findings

Customer response to pensions charges and standardisation

In this part of the interview participants were shown two scenarios relating to pensions charges and standardisation. The aim was to give participants examples of current pension charges on the default investment fund of a workplace pension. This was designed to test understanding of charges and the impact of charges standardisation on participants understanding and engagement. The scenarios were fictional but based on the existing three permitted charging structures.

Customer responses to scenario one

Scenario 1

Liz’s pension provider charges her 0.5% of her pension annually.

John’s pension provider charges him 1% of each contribution he makes to his pension and 0.4% of the total amount he has in his pension annually.

Angela’s pension provider charges her £10 a year and 0.4% of the amount she has in her pension annually.

Scenario one was designed to show the existing permitted charging structures. The examples given (Liz, John and Angela) illustrate the different permitted charging structure. Using the equivalisation tables these three charges equate to a similar overall charge. It was explained to participants that the three people in the example earned the same amount.

Response to charges

Participants with the least understanding found out about charges on their pension through the interview. This was not always welcome news, particularly for those who did not know that their pension was being actively managed and so could not understand what they would be charged for. However, as discussed earlier, through discussing how pensions work participants understood that this would be the case.

Female, 47:

What, why are they charging people? I did not know about this. I’m really annoyed about that and I’m going to be investigating what the situation is with my pension. I mean, why would we be charged?

Female, 33:

It enlightens me a bit and makes me think of course there’s going to be a charge for managing it for me and that’s their job.

When they were shown the charges in scenario one these were much lower than participants had assumed they would be. Participants could not calculate what the charges on their pension would be but felt that, based on the percentages in the example, the charges would be low. This was affirmed by those participants in the sample who had seen their pension charges on their annual statement.

Female, 29:

0.75%, it’s below 1%. It doesn’t sound like a lot. I mean I thought it was all free. That doesn’t sound like a lot, I could live with that.

Understanding of charges

Participants found how the charges were presented in scenario one confusing. They were not able to understand who was paying most or least, nor that they were paying about the same. This was the case amongst men and women and across participants of all different ages.

Male, 37:

If you’re going to ask me which one’s the cheapest, or which one’s the more expensive, I couldn’t tell you.

Female, 50:

I kind of switched off! It’s not clear, is it? Percentages just do not work. Monetary figures would be better.

Male, 38:

Cloak and daggers. They’re all probably the same, just worded differently. To be honest, you lost me on the first bit. Are any of them better? I’d say this is just to trick you. To me, this is just reflective of pensions, you need to know what you’re talking about.

Having different ways of showing the charges was seen as being designed to confuse people and was used as an example of how pensions are confusing.

Participants felt that showing the charge as either a single percentage or in pounds and pence would be easiest to understand. Through discussion, participants found a charge in pounds and pence easiest to understand suggesting that this would be the most effective way of increasing understanding of pensions charges rather than changes to the charging structure.

Male, 28:

It’s very confusing actually… if those are different options for how people get charged for their pensions… how is anyone supposed (to compare)… It’s smoke and mirrors… Whereas something like just a £10 annual fee, well there’s no hoodwinking there. It’s just 10 quid.

In follow-up interviews participants who had been motivated by the research interview to log into their online pension account had not been able to find information about the charges on their pension, suggesting that it is difficult to find.

Customer response to scenario two

Scenario 2

Liz’s pension provider charges her 0.5% of her pension annually.

She sees another pension provider that will charge 0.3% of her pension annually.

Liz’s employer is only required to pay into the pension that they set up. If she moves her pension she may no longer receive employer contributions and they may not make pension contributions for her directly from her salary.

Scenario two was designed to show how charges could vary between pension providers and assess participant understanding of the benefits and drawbacks of switching provider.

Response

Participants quickly understood that Liz was better off staying with her pension provider and ensuring that her employer continued to contribute to her pension. They believed that their employer would only have to contribute to the pension plan they set up for their employees.

It was clear to participants from looking at the scenario that the difference between the two charges was not enough to outweigh the benefit of the employer contributions which would be lost.

Female, 29:

For me, I would stay with my employer scheme. I don’t think it would benefit me. I’d be thinking of the employer contributions. With my situation, where they pay in at the moment, it would make sense to stay with that scheme. I think the saving you would make would not equal the contribution I get.

The perceived effort required to change pension providers was also seen as a barrier to changing.

Male, 38:

She needs to work out how much her employer is contributing to it. I wasn’t even aware you could switch. Now I know, I’d stay with my company, wouldn’t switch. If she loses the contribution, then she’s definitely losing out. I’d probably speak with the employer but the hassle of working it all out is off putting.

The response to this scenario illustrated that employer contributions were an important motivation for participants to save into their workplace pension.

Consolidating deferred pension pots

This chapter sets out findings on participant attitudes towards consolidating deferred pension pots.

Chapter summary

Amongst the participants in this research who had multiple deferred pension pots three broad attitudes towards consolidation were identified: Those who wanted to consolidate their deferred pensions but had not; those who had already consolidated them and those who had decided not to.

Participants with multiple deferred pensions spontaneously considered whether they could consolidate them, whether they knew that this was a possibility or not. They felt that this would reduce the administration burden of having multiple pension pots.

Barriers to consolidation were knowing whether or not they could; fear of being scammed; not knowing the information about their deferred pensions; not knowing how to consolidate or believing it would be hard work.

Participants who were not sure if they had deferred pension pots were interested in how they could find out.

Participants were shown two policy options for automatic consolidation of deferred pensions. In option A, all deferred pensions would be automatically brought together by a government-approved scheme/pension provider and in option B deferred pensions were automatically consolidated into their new pension. The simplicity of both these options strongly appealed to participants. Option A appealed because of the security associated with being backed by the government. Option B appealed because it was seen as being simpler to manage.

Findings

Attitudes towards consolidating deferred pension pots

Participants who had multiple deferred pension pots fit into one of three categories:

- those who wanted to consolidate their pots but had not yet

- those who had already consolidated their deferred pension pots

- and those who had decided not to consolidate their deferred pots [footnote 5]

Wanted to consolidate but had not yet

Even some participants who did not know whether they could consolidate their deferred pensions into one spontaneously expressed a desire to do so.

The benefit of consolidating deferred pots was seen to be making their pension savings less complicated by having them all in one place. This was seen to result in less administration and fewer communications from pension providers.

Male, 29:

I wouldn’t like the idea of having loads of different pots as it would just make it even more confusing. Ideally what I would like to do is just transfer then all into one pot, that I could easily understand and get one figure for them all, rather than thinking about pots and different monetary values.

Female, 34:

This is me! I want to know more - I’ve got a pot here, a pot there. How much is it worth together? How much now and how much will it be worth when I get to retirement? I know it makes sense to put it together, then I’ll know where I am. With it all in one place, you’re more aware, more in control.

Barriers to consolidating deferred pots were:

- did not know if they could consolidate deferred pension pots

- fear of being scammed and losing their savings

- did not know the details of their deferred pensions

- not knowing how to consolidate their deferred pensions

- perceived to be difficult or require a lot of effort

Female, 34:

I would like to bring the (pension) pots all into one place, and I just need to pull my finger out and do it. I’ve seen adverts about it, but it’s a bit scary. I hear about all these people that have been scammed. I don’t know an older person I can ask about it. I wish there was a government website I could trust to let me sort it out. I know they can’t give advice, but some guidance would be good.

Female, 31:

I’d like to put my pensions together, or at least know if I should do that. Periodically I make an effort to look at this. When I joined the pension scheme at work I was interested to see if I could combine them. I did get in touch with the old scheme, and got correspondence from them, but I didn’t understand what it said.

Decided not to consolidate

Participants who had considered consolidating their deferred pots but decided not to felt they could do it when they were closer to retirement age; that they only had a small amount in their different pensions so it was not worth consolidating; had been put off by perceived charges or thought that the Money Saving Expert website had recommended against it.

Had already consolidated deferred pots

Participants who had already consolidated their deferred pension pots had been prompted to do so in some way. For example, one participant who had consolidated their deferred pension pots had done so when starting a new job and signing up to the new pension. During this process they had been asked whether they wanted to move their pension from their previous employer and the transfer had been managed for them. In a similar circumstance, another participant said that a pension advisor at their new employer had suggested that they consolidate their deferred pension. Another person had seen it recommended on the Money Saving Expert website, illustrating how people can understand different things from the same pieces of information.

These experiences illustrate how lack of knowledge and understanding acts as a barrier to consolidating deferred pots. Because people did not understand that they were being charged to have their pension managed, a desire to minimise these could not act as a motivator to consolidate their pensions. It was also evident that the few of those who had consolidated had been prompted to do so by a trusted source of information who had made the process simple. This suggests that people may need support and directed information to encourage them to consolidate deferred pension pots.

Customer responses to small pension pots scenario

As part of the interview participants were shown a scenario about having multiple small pension pots and two potential policy options, to understand their thoughts on these.

Small pots scenario

Angela is 35 and has had 5 jobs which have paid into a pension, which she’s worked at for between 6 months – 3 years.

She has several different pension pots with different amounts in. She is currently paying into a pension pot with her current employer.

Each pension pot is being charged different fees.

Response

Participants who had multiple deferred pension pots strongly identified with the person in the scenario.

Those who had more understanding about pensions understood that having multiple pension pots was a negative and that Angela (and therefore they) should act on this by consolidating her / their pots.

Amongst those who saw having multiple pension pots as a negative, this was because they saw this as being confusing (even more so than their existing pension), difficulty keeping track of them all, for example, knowing how much they had in their pension savings in total. Those who understood about charges also knew that they would be paying charges on multiple pots.

Female, 23:

I think having five different (pensions) is very confusing…Trying to keep track of it all is quite hard to manage. I probably would get confused.

Female, 42:

I would want one pension pot to focus on, it’s just too much to do in my mind. Also, you could put it all in to the one charging the lowest fee.

The benefits of consolidating were seen as:

- having one pension rather than multiple ones was easier to manage

- consolidating their pensions would mean a saving on charges

However, those with less understanding about pensions did not always see any downside to having multiple pension pots.

The scenario raised some questions from participants:

- how to find out if they had multiple pension pots

- how they could find out how to consolidate their pensions

The response to this scenario shows that the first step to encouraging people to consolidate their pension pots is to support them to understand the downsides of having multiple pots and benefits of consolidation. Participants were interested in finding out if they had deferred pots. Signposting people to this information could help spark motivation to engage with information about pensions.

Response to policy options

Two options were presented to participants:

- Option A – when Angela leaves a job, all her pensions are automatically brought together by a government-approved scheme/pension provider

- Option B – when Angela leaves a job, her pension from her old company follows her and is added to the pension at her new company

Preference for the two different options was evenly split across the sample.

The benefits of option A were seen as being the security of a government-approved scheme, which helped to address some concerns about the perceived insecurity of pensions. This scheme was seen as being more secure than a private pension because it was government-backed. This suggests that participants did not know that their pension is already protected by the Financial Services Compensation Scheme or Master Trust authorisation, run by The Pensions Regulator to ensure that master trust schemes run in the best interests of their members.

Option A also appealed because it was seen as being neutral and not tied to their employer. Again, this suggests that participants were not aware that their pension was already their own, independent pension and not associated with their employer beyond the monthly contributions.

Female, 41:

You’re still associating it with the government. They’re putting their stamp on it… So, it must be trustworthy, it must be safe.

Female, 47:

I would worry about it going into the government agency. I mean it’s a long time until I retire - who knows what they might do with the money, what if they dipped into it to support the state pension and it were all to disappear?

Male, 41:

It sounds a bit safer that it’s government approved, and it’s neutral, it’s not tied to your current employer.

Option B was spontaneously requested in response to the scenario about deferred and small pots. In addition, there was already some evidence of people starting a new job being prompted by their new pension provider to switch their savings from their previous employer’s pension scheme into their new pension. Option B was seen as simpler, as there was only one overall pot to manage.

Female, 28:

It would be aligned with where you’re at now. And I don’t know whether the employer would have an issue with not using their current provider.

However, the drawbacks to having multiple pots were not always recognised which meant participants could lack motivation to take this option.

Female, 50:

Why can’t she have six pots now instead of combining them?

Both options appealed because of their simplicity for the customer. It was perceived that the transfer and consolidation process would be managed on their behalf in either case.

Overall, participants recognised that having fewer pots was simpler and easier to manage. The findings suggest that if participants had better understanding about how their pension is protected and that the money is always theirs they could prefer an option where their pensions are consolidated into their new pension.

Encouraging customers to engage with their pension

This chapter explores how customers could be encouraged to engage more with their pension.

Chapter summary

This research found that the following conditions could help motivate people to engage with their pension:

- ability to interpret information they are given about their pension

- being able to influence their pension outcomes

- understanding the benefits of engaging with their pension

- being able to view information about their pension without friction, for example, through an online app

- being sent information in a tangible format which signifies its importance and encourages engagement

The low understanding of pensions amongst participants suggests that increasing understanding of pensions will be important to set information about pensions charges in context. This could also increase member engagement, by helping to empower them to engage and reducing their feelings of fear and confusion in relation to their pension.

Findings

What could motivate people to engage with their pension?

Through this research the following themes emerged in how people could be motivated to engage with their pension more.

Being able to interpret the information

At present, participants could not always understand the information they were given about their pension in terms of what it would mean for them when they came to retire. This meant that engaging with information about their pension could be a confusing and overwhelming experience. Understanding what the information meant for them practically could help reduce this.

Participants in this research expected information about their pension to be confusing and hard to understand. To help counteract these beliefs it is important that information about pensions is simple, easy to understand and visually engaging.

Participants from the research who logged into their online account to find out about their pension after the interview reported being surprised by how accessible and engaging they found the information.

Female, 31:

It rather confuses me how much there will be at the end. I know how much I pay in annually, I hope it goes upwards. On the statement it gives illustrations, like what if this one stayed the same for 30 years, what it would be if it increased in line with RPI. But what I want to know is - what does that mean in real life? what I’m unsure of is, is the projected pay out based on what I’ve paid on so far, or does it assume natural wage growth over that time, so rising contributions? I am rather sceptical of these claims. I look to my parents, who worked all their life and don’t have a good retirement.

Being able to influence their pension outcomes

At present, participants felt they had little control over their pension savings. Demonstrating to individuals how they can influence the outcomes associated with their pension could help increase ownership and engagement with their pension. For example, being able to see what impact retiring later or saving more could have on their pension. In addition, some participants spoke of being motivated by ensuring that their pension was aligned to their interests and priorities on sustainable and ethical investing.

Understanding the benefits of engaging

Participants did not understand why they should engage or how this would benefit them. Better ability to understand the information and seeing how they can influence their pension outcomes could help people see the benefits of engaging with their pension, creating a positive cycle of motivation to engage.

Frictionless engagement

As described, participants were not willing to give a lot of time to engaging with their pension, particularly if logging on to their online account was difficult to achieve. Being able to access information about their pension in a frictionless way will be important to supporting engagement. An app was suggested as a way of achieving this. This was the way that people engaged with their online banking, which they found easy. Participants whose pensions savings were shown in their personal banking app reported that this made their savings more top of mind and meant engaging with it was a more regular experience.

Tangible information

Participants who received information about their pension in the post referred to recognising that this was important because it arrived in the post. Arriving by post also allowed participants to engage with the information on their own time. This was contrasted to the experiences of participants who received information by email which they said was easily missed and lacked the significance of tangible materials such as a letter or leaflet.

The information journey to contextualise pension charges

Given low levels of knowledge and understanding about pensions, evidence from this research suggests that ensuring customers have some wider knowledge about their pension before focusing on information about charges will help to set these in context. This could also increase member engagement, by helping to empower them and not feel afraid and confused by their pension.

The first piece of information to ensure all customers have is knowing who their pension provider is, so they can access information about their pension.

It also seems important for customers to know how much they contribute each month; how much they have saved in total and how they can access the money when they retire. This information helps to contribute to a sense of ownership over their pension.

Participants in this research had little understanding of how tax relief works. This meant that they felt they were taxed twice. Increasing understanding of this could help increase positivity towards the government and pension providers.

Ensuring customers know what happens to their contributions and that they can control what happens to their contributions and that they can choose to pay more in are also important pieces of information to contextualise charges. Understanding that they are in control of their pension means that charges can help people feel like pension customers. This in itself is a powerful motivation to engage with it. However, without this understanding, being told about charges could make people feel that their pension is something which is done to them, rather than something they do for themselves.

Conclusions

This chapter summarises the key findings from this research.

Knowledge, understanding and engagement with pensions

The attitudes participants expressed towards their pensions were characterised by detachment, complacency and fear. These acted as a barrier towards engagement. Greater engagement with pensions could be supported by addressing these attitudes. This would include encouraging a greater sense of ownership; establishing the belief that members can tangibly benefit from engaging with their pension and reducing fear of loss or making errors.

In the interviews, participants had low confidence in their knowledge about pensions. This was reflected in low expressed knowledge and understanding and led to low confidence about engaging with them.

When people were sent information about their pension they recognised it was important and engaged with it. However, they did not know how to act on this information or what to do with it, so typically reviewed it and filed it away. Members expressed a preference for information which was succinct and visually engaging.

Proactive engagement with information about pensions was driven by the desire to find something out. For example, members sought to confirm that their and their employers’ monthly payments were being paid in and how much money they had saved into their pension in total.

However, participants lacked understanding about what their current savings meant for their future or the impact that making changes now could have which reduced their likelihood of taking action in response to information about their pension.

This suggests that understanding what their current savings mean for their future and the impact of making changes, such as saving more or retiring later, could help to encourage greater member engagement.

Switching pension provider

Participants had not considered switching pension provider and when discussed in the interview had little desire to. They trusted the decision that their employer had made on their behalf about which pension provider to use. In addition, they believed that their employer would only have to pay into the pension provider they had selected and did not want to lose their employer contributions by switching.

Participants were shown an example of pension charges, which said that the employer contributions would be lost if the member switched to a pension provider which had lower charges. In this case, participants were able to trade off the reduction in pension charges against the loss of employer contribution and would stay with their employer. This part of the discussion also illustrated the importance of employer contributions.

Pensions charges and standardisation

Participants who had not thought about how their pension would be managed were surprised to hear that there were charges on their pension pot. As they reflected on this through discussion, they understood that there would be charges for managing their pension. When shown the example of charges they felt that these were lower than they had expected.

Those who already knew about pension charges felt that they were negligible amounts.

When shown the examples of the current permitted charging structures, participants found these hard to understand. They preferred for charges to be shown in pounds and pence so they could understand how much they would be.

Consolidating deferred pension pots

Barriers to consolidating deferred pension pots included lack of awareness of the ability to do so or the benefits of doing so or concerns about the risks of doing so. The perceived risks included falling victim to a scam or having to pay.

Motivations to consolidating included reduced administration, as a result of only having to monitor one pension pot. In this sample, those who had consolidated their pension pots had done so in response to an external prompt, for example from their new pension provider when changing employer.

Participants were open to both policy options for automatic consolidation as long as it was simple for them and safe.

Encouraging customers to engage with their pension

This research found that the following understanding could help motivate people to engage with their pension:

- being able to interpret information they are given about their pension

- being able to influence their pension outcomes

- understanding the benefits of engaging with their pension

- being able to view information about their pension without friction, for example, through an online app

- being sent information in a tangible format which signifies its importance and encourages engagement

The low understanding of pensions amongst participants suggests that increasing understanding of pensions will be important to contextualise pensions charges. Without this, there is a risk that people will not understand what they are being charged for. Greater understanding of pensions could also increase member engagement, by helping to empower them to engage and reducing their feelings of fear and confusion in relation to their pension.

Appendix A

Appendix 1: Technical information

Qualitative methodology

This section provides more detail on the qualitative methodology.

Materials Development

The depth interviews were guided by a topic guide (this can be found in Appendix 2: Materials) . The topic guide was developed in discussion with the DWP and were designed to reflect the aims and objectives of the study.

Depth interviews

The study comprised a total of 60 depth interviews. Participants were purposively recruited using free-find methods.

All participants were saving into the default fund of their workplace pension scheme. Participants were purposively to ensure a broad spread of age, gender, income level, life-stage, self-perceived financial confidence, whether or not they were saving in other ways in addition to their pension and geographical region.

Table A1.4: Sample breakdown of the depth interviews

| Quota | Subgroup | Number of interviews |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 32 |

| Gender | Male | 28 |

| Age | 22 - 30 | 19 |

| Age | 31 - 40 | 24 |

| Age | 41 - 50 | 17 |

| Income | Up to £25k | 18 |

| Income | £25k – 40k | 27 |

| Income | £41k – 55k | 9 |

| Income | Over £55k | 6 |

| Pension provider | Master Trust - NEST, The People’s Pension, NOW: Pensions | 27 |

| Total number of interviews | 60 |

Data management and analysis approach

Interviews were all recorded, with informed consent being gained from respondents. Recordings were either transcribed verbatim or researchers wrote detailed notes, listening back to recordings to ensure no data was lost.

The data collected from the qualitative research was entered into an analysis grid in Microsoft Excel, used as the basis for thematic analysis. The analysis grid grouped the findings from the interviews into themes, based around the study objectives and those which emerged through analysis. In addition, analysis considered similarities and differences amongst different subgroups such as age, gender, working status (full or part time), income and location.

Please note: qualitative research is used to map the range and diversity of different type of experiences rather than indicate the prevalence of any one particular experience; as such numerical language is not used and findings are not aimed to be statistically representative.

Appendix 2: Materials

Standardised Pensions Charges Discussion guide

Note to interviewers

The following conventions are not shown in this appendix.

We use several conventions to explain to you how this guide will be used:

- Bullet = Question or read-out statement: Questions that will be asked to the participant if relevant. Not all questions are asked during fieldwork, based on the moderator’s view of progress and whether the material has already been covered spontaneously

- Italics = prompt: Prompts are not questions, they are there to provide guidance to the moderator if required

- Italics in bold = prompt that needs to be covered

Interviewer – please check information collected at recruitment to help with probes throughout.

1. Introduction

(Timing for this part: 2 to 3 minutes)

- Thank participant for taking part. Introduce self and explain nature of interview: informal conversation; gather opinions; all opinions valid. Interviews should take 45-60 minutes.

- Introduce research and topic – DWP has asked Ipsos MORI to help them with some research with people about their pensions. There are no right or wrong answers, we are interested in your thoughts and experiences, so please be as open and honest as possible. Participation is voluntary and will have no impact any dealings you may have with DWP or other government departments now or in the future.

- Role of Ipsos MORI – Independent research organisation (i.e. independent of government), we adhere to the MRS Code of Conduct.

- Confidentiality – reassure all responses anonymous and that identifiable information about them will not be passed on to anyone, including back to DWP.

- Consent – Ipsos MORI’s legal basis for processing is their consent to take part in this research. check that they are happy to take part in the interview and understand their participation is voluntary (they can withdraw at any time).

- As a thank you for taking part they will receive £40

- Ask for permission to digitally record – check back when writing our notes, recordings held securely and destroyed once project has finished. Not shared with DWP.

- Any questions before we begin?

2. Individual context

(Timing for this part: 5 to 10 minutes)

This section aims to warm up the participant and gain some background information about them.

To start with, ask them to talk a little about themselves: