Our Vision for the Women's Health Strategy for England

Published 23 December 2021

Applies to England

Ministerial foreword

In March 2021, the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care and the Minister of State for Patient Safety, Suicide Prevention and Mental Health published a call for evidence seeking views on the first-ever government-led Women’s Health Strategy for England.

By the time the call for evidence closed 14 weeks later, we had received nearly 100,000 responses from women across the country, and over 400 written responses from organisations and experts working in the health sector and beyond.

As set out in the analytical report accompanying this publication, their stories make sobering reading. And we are determined to make sure that these women’s perspectives count. The system must be reformed along with its core values so that the voices of this 51% of the population are heard.

Reform is possible. In October 2021, in a debate on a Private Member’s Bill aiming to remove prescription charges on hormone replacement therapy (HRT), we heard frank personal testimonies from MPs, not only regarding menopause specifically but regarding their experiences of healthcare more broadly.

It was with great pride and heartfelt thanks to all those who stood up to speak that day that I (Maria Caulfield MP) was able to announce the government’s intention to slash HRT charges, along with the establishment of a UK Menopause Taskforce co-chaired by Carolyn Harris MP, who proposed the Private Member’s Bill, and myself. This action has shown us all what can be achieved when people and organisations work together to do the right thing.

It is time to re-set the dial on women’s health. This publication sets the government’s vision for a new healthcare system, which offers equal access to effective care and support, prioritising care on the basis of clinical need and not of gender.

Our vision is underpinned by the analysis of what you have told us through the call for evidence. When we publish the full strategy next year, we will set out our ambitions in more detail, and will follow up with full delivery plans where appropriate.

Women and healthcare professionals across England have made clear their voices and have told us what they need us to change. In some areas this change will come more quickly than in others; there are no silver bullets when it comes to decades of bias, and if change is to be meaningful then it must sometimes take time. But I know that there is real willingness across all parts of the health sector and beyond to make this moment count.

We will not let you down.

The Rt Hon Sajid Javid MP

Maria Caulfield MP

1. The call for evidence and the case for change

On 8 March 2021, the government launched a call for evidence to inform the development of England’s first Women’s Health Strategy. Our rationale was twofold.

First, to improve the way in which the health and care system listens to women, and to reset our approach to women’s health by placing women’s voices at the centre of this work. Independent reports and inquiries – not least the report of the Independent Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Review and the report of the independent inquiry into the issues raised by Ian Paterson – have found that it is often women whom the healthcare system fails to keep safe and to whom the system fails to listen. We are determined that the Women’s Health Strategy will be a catalyst for change.

Second, to improve women’s health outcomes. While women in the UK on average live longer than men, women spend a greater proportion of their lives in ill health and disability when compared with men, and there are growing geographic differences in women’s life expectancy. We also know that there are disparities between different groups of women in terms of access to services, experiences of healthcare, and health outcomes. We want to investigate the ways in which the healthcare system’s structure adversely affects women’s health.

The call for evidence

The call for evidence ran for 14 weeks from 8 March to 13 June 2021. There were 3 parts to this call for evidence:

-

a ‘Women’s Health – Let’s talk about it’ public survey, which was open to all individuals aged 16 and over in England

-

an open invitation for individuals and organisations with expertise in women’s health to submit written evidence

-

a focus group study with women across England, undertaken by the University of York in collaboration with the King’s Fund

We received 110,123 responses to the public survey, of which 97,307 were from individuals who told us that they lived in England and wanted to share their own experiences, the experiences of a female family member, friend or partner, or their reflections as a health or care professional.

We also received over 400 written responses. A separate report on the written evidence submitted by organisations and individuals with expertise in this field will be published in early 2022. The findings of the focus group study can be found on the PREPARE website. The call for evidence findings are summarised throughout this document and can be found in full in the call for evidence response.

We are extremely grateful to all the individuals and organisations who responded to our call for evidence. The public survey provides a rich source of data on women’s experiences of healthcare over the life course and on the interventions that would make the most difference to them. In turn, this provides a strong mandate for change, and the starting point for our future policy development.

The strategy’s aim is to improve the health of all women and girls, irrespective of whether they have undergone gender reassignment or are transgender. While in this document we refer to women, we recognise that some transgender men, non-binary people and people with variations in sex characteristics (VSC) or who are intersex may also experience some of the same issues covered. We also recognise that people who are trans, non-binary or have VSC will have specific needs and experiences, and work is ongoing across government to address these.

The call for evidence told us that women do not feel heard within the healthcare system. We are clear that this must stop. We commit to making change happen.

2. The ambition for women’s health

A new approach

Central to the Women’s Health Strategy will be a focus on women’s health across the life course. Unlike a disease-orientated approach, which focuses on interventions for a single condition often at a single life stage, a life course approach focuses on understanding the changing health and care needs of women and girls across their lives. It aims to identify the critical stages, transitions, and settings where there are opportunities to promote good health, to prevent negative health outcomes, or to restore health and wellbeing. Key considerations include the ways in which specific life events or stages of life can influence future health. For example, we know that women who have high blood pressure or pre-eclampsia during pregnancy are at greater risk of heart attack and stroke in the future.

This approach has already been adopted by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) in their report Better for Women. The main benefit of this approach is that it allows us to intervene earlier in order to prevent negative outcomes and to improve intergenerational health outcomes, as well as to improve overall quality of life.

Women’s health across the life course

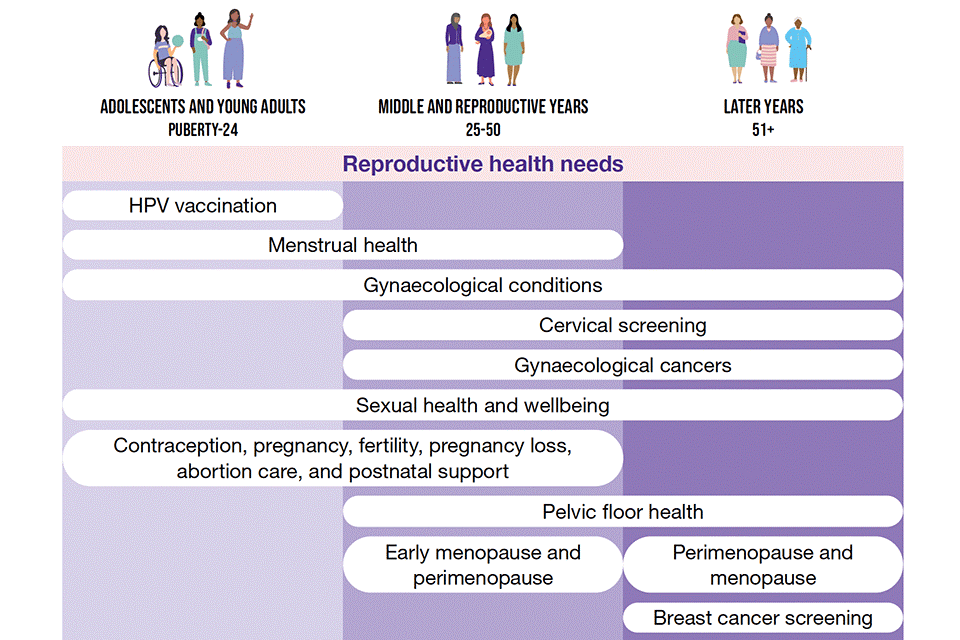

The diagram shows the reproductive health and general health needs of women throughout their life course.

The diagram has 3 columns, each representing a life course stage:

- first, adolescents and young adults, from puberty to 24 years

- second, middle and reproductive years, from 25 to 50 years

- third, the later years, from 51 years onwards

A horizontal bar represents each health need and show how many of the life-course stages it affects. These health needs are:

- reproductive health needs:

- HPV vaccination is limited to stage 1, adolescents and young adults

- menstrual health is across stages 1 and 2, adolescents and young adults, and middle and reproductive years

- gynaecological conditions is across all 3 stages

- cervical screening is across stages 2 and 3, middle and reproductive years and later years

- gynaecological cancers is across stages 2 and 3, middle and reproductive years and later years

- sexual health and wellbeing is across all 3 stages

- contraception, pregnancy, fertility, pregnancy loss, abortion care, and postnatal support is across stages 1 and 2, adolescents and young adults, and middle and reproductive years

- pelvic floor health is across stages 2 and 3, middle and reproductive years and later years

- early menopause and perimenopause is limited to stage 2, middle and reproductive years

- perimenopause and menopause is limited to stage 3, later years

General health needs:

- wellbeing and lifestyle, for example healthy weight, exercise and smoking is across all 3 stages

- mental health is across all 3 stages

- long-term conditions is across all 3 stages

- health impacts of violence against women and girls is across all 3 stages

- osteoporosis and bone health is limited to stage 3, later years

- dementia and Alzheimer’s is limited to stage 3, later years

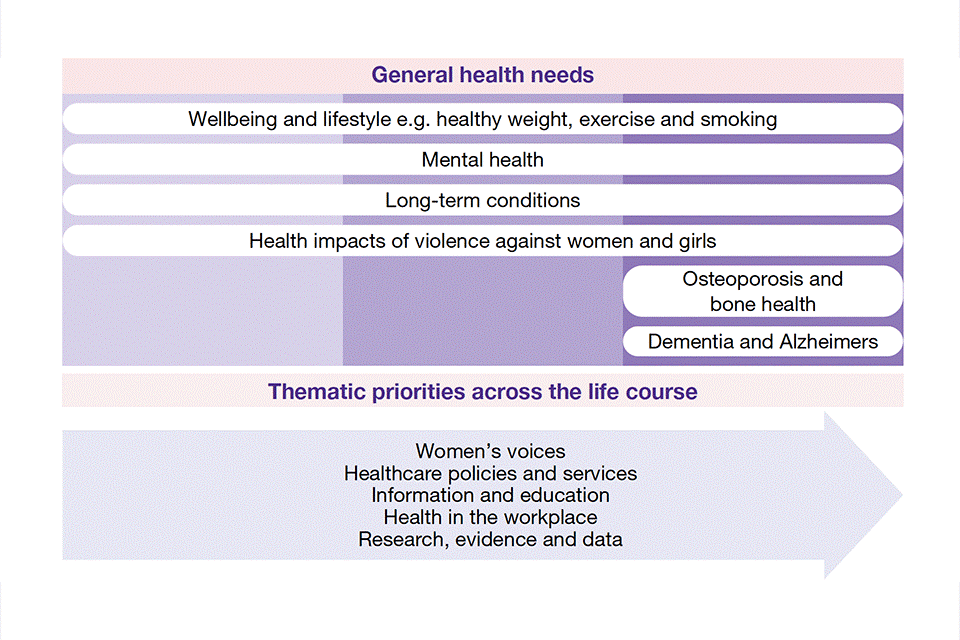

An arrow contains 5 key themes that the vision document focuses on and which impact all health needs of women throughout their life course. These themes are:

- women’s voices

- healthcare policies and services

- information and education

- health in the workplace

- research, evidence and data

A life course approach also enables action on wider determinants of health, for example social, economic and environmental factors. It is important to consider such factors in the round alongside opportunities for preventative action to support women and girls in improving their health outcomes, or to reduce the risk of ill health later in life.

We know that there are disparities between different groups of women in terms of access to services, experiences of healthcare, and health outcomes. A key priority of the Women’s Health Strategy will be to better understand and tackle disparities in experience and outcomes throughout women’s lives.

This vision document

This document, Our Vision for the Women’s Health Strategy for England, sets out what we were told in the call for evidence, and the key themes and areas of focus that make up our ambition.

The thematic chapters set out in both the call for evidence and in this vision were chosen because they are relevant to women’s health across the life course.

These themes are:

-

women’s voices (section 3)

-

healthcare policies and services (section 4)

-

information and education (section 5)

-

health in the workplace (section 6)

-

research, evidence and data (section 7)

Collectively, these themes set out the government’s vision for the health of women and girls going forwards. Against each theme, we have set out a summary of what we have heard in the call for evidence, followed by an outline of our ambition and next steps. This sets the bar for action across the health sector and wider government. We expect to be held to account against this action over the coming months.

Key themes

The diagram shows the 5 key themes that the vision document focuses on:

- healthcare policies and services

- information and education

- health in the workplace

- research, evidence and data

- women’s voices

The vision then focuses on priority areas relating to specific conditions or areas of health where the call for evidence highlighted particular issues or opportunities. These areas include, but are not limited to:

-

menstrual health and gynaecological conditions

-

fertility, pregnancy, pregnancy loss and post-natal support

-

the menopause

-

healthy ageing and long-term conditions

-

mental health

-

the health impacts of violence against women and girls

See section 8 for more information on these areas.

As with against the themes, against each topic we have set out what we have heard in the call for evidence, alongside government ambition and next steps.

In spring 2022 this vision will be followed by the Women’s Health Strategy, which will build on our vision and ambition, and which will set out in detail our plans for specific health needs and conditions that women experience at different stages. We will bring forward concrete action both on issues that only affect women, and on issues that affect everyone but that are more prevalent in women or where women have systematically poorer outcomes. At the same time, work is underway on the government’s forthcoming Sexual and Reproductive Health Strategy.

Next steps for the Women’s Health Strategy are set out in section 9 of this publication.

3. Women’s voices

What we’ve heard

Taboos and stigmas

In the call for evidence we heard that damaging taboos and stigmas remain in many areas of women’s health. These taboos and stigmas can prevent women from seeking help, and can reinforce beliefs that debilitating symptoms are ‘normal’ or something that must be endured. In the public survey, respondents felt more comfortable speaking about general health concerns such as diabetes or heart disease, compared with female-specific issues such as gynaecological conditions or the menopause. Respondents felt even less comfortable speaking about disability and mental health conditions. Some of these conditions are specific to women, such as postnatal depression. We also heard about are conditions that may present differently in women compared to in men, such as autism.

Feeling listened to by healthcare professionals

In the public survey, 84% of respondents said that there had been instances in which they had not been listened to by healthcare professionals. We heard that women had experienced this at every stage of the journey, from initial discussion of symptoms, to further appointments, discussion of treatment options, and follow up care. We heard concerns that women had not been listened to in instances where pain is the main symptom, for example in being told that heavy and painful periods are ‘normal’ or that the woman will ‘grow out of them’. We have also heard concerns from respondents that some healthcare professionals have reportedly used gendered stereotypes around women’s wish for children in order to deny procedures such as sterilisation.

Women’s voices within healthcare system

We heard the importance of listening to women at all levels of the healthcare system. This was a particular theme in some written submissions. We heard calls for more accountability and leadership for women’s health at local and national level. Some submissions also called for improved representation of women as individuals, or of women’s experiences, across different parts of the healthcare system. This included in the development of medical curriculums and training; in the design of specific healthcare services; on governance structures, for example boards; and in research career pathways. We heard about the importance of listening to individual women’s experiences and feedback, especially from groups of women who are usually under-represented in surveys and research studies.

Our ambitions

Our ambitions are:

-

women feel comfortable talking about their health, whether that be with healthcare professionals, friends or family; women know when they can seek help for symptoms; and women’s health issues are no longer taboo topics

-

women feel better listened to and heard by healthcare professionals, and women’s concerns and symptoms are taken seriously

-

women’s voices and experiences are represented and listened to at all levels and in all areas of the healthcare system

Next steps

On taboos and stigmas, we will take forward work through our thematic priorities of information and education, and health in the workplace (see sections 5 and 6).

On being listened to by healthcare professionals, we will take forward work to better understand the causes behind women not feeling listened to. This includes investigating themes such as the quality of conversations and shared decision making; the role of information, education and training for healthcare professionals; and how to embed changes within clinical practice.

On representation and listening at the system level, we will appoint a government Women’s Health Ambassador. We will continue to explore how best to gather women’s experiences and to embed their voices within the implementation of the strategy.

4. Healthcare policies and services

What we’ve heard

Women’s reproductive health services over the life course

In the call for evidence we heard the importance of women being able to access services that meet all their reproductive health needs, from the routine (for example choosing the right contraception) to the more specialist (for example specialist endometriosis care).

We heard that it can be difficult for women to access the reproductive healthcare services they need in ways that are convenient to them. We heard that fragmented delivery of sexual and reproductive health services negatively impacts women, with some respondents calling for more joined-up and holistic provision through women’s health clinics or hubs. We also heard concerns about geographical variation in access to some services, for example menopause clinics and NHS fertility treatment.

We heard concerns that the pandemic made it more difficult to access some services such as cervical screening or procedures for long-acting reversable contraception (LARC). We also heard of some positive changes, for example the offer of virtual or telephone appointments alongside face to face appointments.

Consideration of women and women’s health in the development of all policies and services

In the call for evidence we heard concerns that services for specialities or conditions which only or primarily affect women, for example reproductive health services, are perceived to be of lower priority compared to other services. However, in the public survey respondents also provided examples of a number of general health conditions where they thought that services could be improved, such as fibromyalgia, myalgic encephalomyelitis or chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and mental health services. We also heard that some general health conditions, for example ADHD and autism, are sometimes perceived as ‘male’ issues, and that women can face additional barriers to referral and diagnosis in these areas as services do not feel designed for women.

Ensuring equitable access to services and reducing disparities in health outcomes between women

In the public survey, 40% of respondents said that they, or the woman in mind, could conveniently access the services they needed in terms of location, and 24% said the same in terms of timing. In the call for evidence written submissions, we heard that some groups of women face additional barriers regarding access to and experience of services, and that there are disparities in health outcomes.

For instance, we heard that women with physical or learning disabilities can face additional barriers in accessing services such as contraception and cervical screening. We also heard that women in particular settings, such as the criminal justice system, face additional barriers to accessing healthcare, and have poorer health outcomes compared with women in general.

We heard about disparities in health outcomes between different demographic groups. For example, although maternal deaths are very rare, there are disparities in this area, with black and Asian women being more likely than white women to die during pregnancy and childbirth. We also heard that there are disparities in access to services and health outcomes that stem from economic and geographical disparities, for example differences in life expectancy across socio-economic groups.

Our ambitions

Our ambitions are:

-

women can access services that meet their reproductive health needs across the life course, and women’s experiences of services and reproductive health outcomes are improved

-

national healthcare policy and services consider women’s needs specifically, and by default

-

all women, including those with additional risk factors or who face additional barriers in accessing services, have equitable access to and experience of services, and disparities in outcomes are reduced

Next steps

On women’s reproductive health, we will look at how we can support and encourage joint commissioning. We will work with the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID) and others to support local systems to explore innovative models of care that improve women’s access to reproductive health services. We will work alongside the forthcoming Sexual and Reproductive Health Strategy to set out our approach to improving women’s sexual and reproductive health.

On consideration of women and women’s health as default in the development of all policies and services, we will take forward work to explore specific conditions and areas of healthcare in which disparities are greatest. We will work alongside other strategies being developed and other programmes of work to share insight from the call for evidence, and to ensure greater consideration of women’s health-specific implications.

On equitable access to services and reducing disparities in outcomes, we will work with OHID, NHS England and Improvement, government departments and others to ensure that the Women’s Health Strategy has a clear focus on better understanding and working to reduce disparities between groups of women, and that disparities between groups of women are considered as part of the wider levelling-up agenda.

5. Information and education

What we’ve heard

Information for women and wider society

In the call for evidence we heard of the importance of high-quality information provision, from school education for girls and boys, through to support for adults.

With regards to school education, respondents to the public survey placed importance on making sure that the relationships, sex and health education (RSHE) curriculum is taught to both girls and boys, so that boys are also educated on female health conditions. Respondents who stated that they were teachers also reflected that they were not adequately equipped to teach certain topics effectively, with suggestions including the introduction of modern teaching tools (for example webinars).

While we heard that the NHS website is a useful and trusted source of information, some women and organisations highlighted that it would be helpful if this website had a central area signposting up-to-date information on various aspects of women’s health. We also heard calls for more information on certain women’s health conditions, for example adenomyosis.

More widely, we heard calls for more trusted and easier to understand information regarding a range of women’s health issues such as fertility, the menopause, gynaecological conditions and gynaecological cancers. We heard that this information should be prepared and distributed in formats that are accessible in a range of ways, such as blogs or social media.

Education and training for healthcare professionals

Through the call for evidence we heard about the need for healthcare professionals to receive better education and training on women’s health conditions. This includes female-specific conditions and treatment options, in particular the menopause and HRT. We also heard about a lack of awareness amongst some GPs of the causes of infertility, miscarriages and their relationship with infertility, and the reasons for in vitro fertilisation (IVF) failure.

There was emphasis on education for GPs in particular, as GPs are often the first port of call for many women, and gatekeepers to other services. Some responses called for compulsory training for GPs on women’s health, and noted that this would create an empathetic, supportive and informed environment in which women would feel comfortable coming forward to discuss issues. Respondents felt that improvements in the ways in which healthcare professionals listen to, communicate with, and treat women are particularly important where women feel that they are not listened to (see section 3).

Our ambitions

Our ambitions are:

-

women have access to high-quality information and education, starting from childhood and continuing through to adulthood, to empower women to make informed decisions about their health and wellbeing across the life course

-

women receive accurate and up-to-date advice from healthcare professionals, supported through high-quality training for professionals, ensuring that clinical guidelines represent the latest evidence on women’s health conditions and consider differences between men and women; and healthcare professionals are supported in implementing these guidelines

Next steps

We are committed to ensuring that teachers have the necessary resources to teach RSHE effectively, and will work to better understand gaps in their knowledge and teaching materials.

Beyond school education, we will work to understand where symptoms and conditions are not currently captured. We will work with NHS Digital to progress the content transformation agenda to help ensure digital information is accessible and meets the health needs of women.

We will continue to explore how best to support healthcare professionals in implementing guidelines.

6. Health in the workplace

What we’ve heard

Through the call for evidence we heard that health conditions and disabilities can impact women’s experience in the workplace, and can increase women’s stress levels and impact their mental health and productivity. In order to support women with particular conditions, respondents called for a continued uptake of flexible working arrangements which, for some, were not available prior to the pandemic.

Another theme highlighted the importance of raising awareness and understanding of women’s health in the workplace, as well as of normalising discussions surrounding this topic. Organisations highlighted the need for more conversation on taboo topics including periods, and increased dialogue on the impact of the menopause at work to ensure that women can remain productive and supported. We also heard many examples of good practice, whereby employers have worked with employees and external experts to introduce new workplace policies and other support, and have encouraged open conversations in the workplace.

Finally, on average just 11% of respondents to the public survey said that they were aware of any provision of policies and/or protection by their current or previous workplace regarding domestic abuse. This dropped to 5% for respondents in the private sector, marking the need to progress this further.

Our ambitions

Our ambitions are:

-

women feel supported in the workplace, and that taboos are broken down through open conversation

-

employers feel well equipped to support women in managing their health within the workplace

Next steps

Flexible working can be important in helping individuals to work in a way that meets both their own personal needs, and those of their employer. We will link work on women’s health to the government consultations on ‘Making flexible working the default’ and ‘Health is everyone’s business’.

Work is underway to improve workplace support for specific health concerns or conditions. Within the Civil Service, in line with the findings of the call for evidence, we will work to implement our commitment to introduce a workplace menopause policy. Earlier this year the Minister for Employment commissioned from leading employer organisations an independent report on the issue of the menopause and the workplace. The report, Menopause and Employment: how to enable fulfilling working lives, was published on 25 November 2021 and the government will respond to the recommendations in the New Year. The recently announced UK Menopause Taskforce will also consider how we can improve workplace support for the menopause in particular.

We commend organisations who have taken the initiative to recognise the complex concerns women face around their healthcare. We want to work with, and support, employers, third sector organisations and professional bodies to strengthen or develop workplace guidance and other forms of support that will enable women to reach and/or maintain their full potential.

7. Research, evidence and data

What we’ve heard

Research and evidence

In the call for evidence we heard that there is currently a lack of research into women’s health issues, and that this has led to an overall gap in the data that is available. In particular, we heard that there is a need for more research into female-specific issues, such as endometriosis and the menopause.

The call for evidence also told us that we need more research into if, and where, there are differences between men and women in terms of symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment for general health conditions (such as autism and cardiovascular disease). We also heard that research outcomes from studies with only male participants should not automatically be applied to women.

We heard that findings from clinical studies and other types of research should be made more widely accessible. We also heard that research and evidence should be disseminated in a way that is accessible for women from all backgrounds. This would support women to be informed on issues that affect them, and raise awareness among friends and family members, who in the public survey were often used by respondents as a primary source of information on health conditions.

We heard similar reflections from the small proportion of self-identified health or care professionals in the public survey. Some even went further by suggesting that things are unlikely to change unless we also increase the diversity of those involved in designing research studies, and better support women in research roles.

Data

In the call for evidence, we heard that when data is collected, it should be broken down and analysed by demographic characteristics such as ethnicity, age, sex, and geography in order to identify and respond to disparities in outcomes and experience. Some written submissions focused on gaps in current evidence bases and data collection, for example in relation to specific conditions, medicines or medical devices. Others focused on the need for data from research studies to be analysed by sex, and by other demographic factors such as ethnicity.

We also heard in the call for evidence that future research should recruit and consider groups of women who have historically been under-represented in research and data collection, for example women of black and Asian ethnicity, to ensure that research outcomes can benefit all women in society.

We recognise that there may be a gap in understanding the views of healthcare professionals, as they represented just 2% of respondents to our public survey. Further research could help us to determine how we can best equip healthcare professionals to support women, and to ensure that women have comfortable and valuable interactions with healthcare professionals in the future.

Our ambitions

Our ambitions are:

-

women’s voices and priorities are at the heart of research, from identification of need through to participation in research, dissemination of research findings, and implementation in practice

-

we have the right data and make better use of the data we collect in order to tackle sex-based data gaps, with the aim of improving women’s health outcomes, reducing disparities and supporting a life course approach for women’s health

-

to embed routine collection of National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) research participant demographic data, including sex and ethnicity, and use this data to ensure that our research is representative of the society we serve

Next steps

We are pleased that in recent years there has been a significant amount of research into women’s health conditions. However, there is an overall need for more research into women’s health including that looking specifically at sex differences in conditions, and for greater monitoring of the diversity of research participants, including in NIHR-funded studies.

As we develop the Women’s Health Strategy, we will work alongside the forthcoming Data Saves Lives Strategy for health and social care to consider how we can make better use of, and increase access to, data collected from heath and care services. This will be crucial in efforts to tackle sex data gaps.

8. Priority areas

In the previous sections we have set out our approach to the cross-cutting themes which are relevant to the health of women and girls across the life course, and which will drive work across all areas of the strategy. Responses to the call for evidence have also highlighted issues specific to certain conditions or areas which will require targeted action.

We will address these areas in more detail through the strategy publication in 2022. In the meantime, we outline below what the call for evidence has told us, alongside our ambition and next steps.

Menstrual health and gynaecological conditions

What we’ve heard

In the call for evidence public survey, menstrual health was the topic most selected by respondents aged 16 to 17 for inclusion in the Women’s Health Strategy, and gynaecological conditions was the number one topic selected by those between the ages of 18 to 19, 20 to 24 and 25 to 29. Older respondents tended to feel more comfortable talking to healthcare professionals about gynaecological conditions than younger respondents did, and also about gynaecological cancers, but only 8% of respondents felt that they had access to enough information on gynaecological conditions, such as endometriosis and fibroids.

Women said that they persistently needed to advocate for themselves and to push for further investigation in order to secure a diagnosis, speaking to doctors on multiple occasions over many months or years for conditions such as endometriosis. These delays often had wider ramifications for their health and quality of life.

This was representative of written submission evidence from organisations who highlighted that women with endometriosis and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) report considerably long times to gain a diagnosis. Written evidence also reported that care needs can change over the life course, and that there needs to be more awareness and information on these conditions as women do not always realise that what they are experiencing is abnormal.

Our ambition

Our ambition is that every woman and girl can access the right information, support and diagnosis for menstrual health and gynaecological conditions.

Next steps

We will explore ways in which to improve awareness for, care of and treatment for those suffering with severe symptoms of conditions such as heavy menstrual bleeding, endometriosis and PCOS. The forthcoming strategy will set out our plans across menstrual health, gynaecological conditions, and gynaecological cancers in more detail.

Fertility, pregnancy, pregnancy loss and post-natal support

What we’ve heard

In the call for evidence public survey, the topic of fertility, pregnancy, pregnancy loss and post-natal support was the second most selected topic that respondents picked for inclusion in the Women’s Health Strategy, and the most selected topic for respondents aged 30 to 39. Responses to the public survey and written submissions covered a wide range of issues, including contraception, preconception health, fertility and infertility, pregnancy loss and stillbirth, support for expectant and new mothers and their partners, pelvic floor health, and patient experience and safety. Many of the written submissions in particular also spoke of the importance of continuing to tackle disparities in maternal and neonatal outcomes.

Information was another key theme, with calls for more information on the causes of infertility, the likelihood of a successful pregnancy at a later age, information relating to women’s health prior to pregnancy, and the realistic success rates of fertility treatments.

Another key issue raised was miscarriage and pregnancy loss. Women who responded to our public survey shared accounts of the devastating impact of pregnancy loss and the variation in the level of support available from healthcare services and employers.

Finally, some written submissions also focused on the ways in which pregnancy can be a key intervention point in a woman’s life course, and the ways in which pregnancy provides an opportunity to support improvements to women’s health, for example regarding advice on smoking, obesity, and specific interventions such as postnatal contraception.

Our ambition

Our ambition is that women are empowered to make purposeful choices about their reproductive health and care before, during and after pregnancy and pregnancy loss, with support from safe, high-quality health services.

Next steps

We will maintain our efforts to improve outcomes for mothers and babies, including a strong focus on reducing maternal and neonatal disparities. Improving our understanding of the underlying causes of pregnancy complications, as well as improving data collection and disaggregation, is vital in tackling these disparities.

In the strategy, we will consider how we can strengthen healthcare and workplace support for women and partners affected by pregnancy loss and other pregnancy and fertility-related issues. We will also consider the recommendations of the DHSC-commissioned Pregnancy Loss Review once published.

We will work with the forthcoming Sexual and Reproductive Health Strategy to ensure that the two strategies together set out our approach to improving women’s sexual and reproductive health.

The menopause

What we’ve heard

In the call for evidence public survey, the menopause was the third most selected topic that respondents picked for inclusion in the Women’s Health Strategy, and the most selected topic for respondents aged 40 to 49 and 50 to 59. In the survey, respondents reported that their comfort when talking about the menopause with friends, family and healthcare professionals was lower than when they were talking about other female-specific issues such as gynaecological conditions or pregnancy, demonstrating that for many the menopause may remain a taboo topic. In addition, only 9% of respondents felt that they had enough information on the menopause, and many responses reflected that respondents had not learnt about or been educated on the menopause until they themselves were experiencing it.

Another important theme was access to treatment, where we heard about challenges in accessing high quality menopause care. Respondents reported that symptoms were not taken seriously or recognised as the menopause, and that there were difficulties in accessing HRT, with some GPs reluctant to prescribe HRT. Women also called for more information on the menopause, and on treatment options, in particular in cases where HRT is not suitable. We also heard calls for healthcare professionals to be better educated on the menopause and HRT. This was primarily in relation to GPs as the first port of call. Some submissions also spoke of the need for all healthcare professionals, not just GPs and menopause specialists, to be well informed about the menopause.

Menopause in the workplace was another key theme, with responses to the survey and written submissions calling for more support through workplace policies and other initiatives such as staff training, and many examples of best practice were submitted.

Our ambition

Our ambition is that every woman has access to the care and support they need during the menopause, and is supported to fulfil their potential though this stage of life.

Next steps

We will work to take a holistic approach to improving care and support for people experiencing the menopause, and will set out our approach in the strategy.

We will work to implement recently announced reforms, including: measures to reduce the cost of and improve access to HRT, the establishment of the UK Menopause Taskforce, and the development of a Civil Service menopause workplace policy. We will consider the recommendations in the Women and Equalities Select Committee inquiry into menopause in the workplace, and the inquiry of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on menopause, when the reports are published.

Healthy ageing and long-term conditions

What we’ve heard

In the call for evidence public survey, healthy ageing was the ninth most selected topic that respondents picked for inclusion in the Women’s Health Strategy (23%), and the top topic for respondents aged 60 and over. A number of respondents to the survey also highlighted that they would like the Women’s Health Strategy to cover long-term conditions such as musculoskeletal conditions (8%) and heart disease and stroke (7%).

We also heard of the importance of supporting women and girls at all stages of the life course, and of supporting women in relation to non-female specific health concerns as well as in relation to reproductive health. We heard of the importance of high-quality information to support women in making healthier choices throughout the life course and to promote healthy ageing.

We also heard of the importance of recognising female-specific risk factors, for example the ways in which conditions such as gestational diabetes and hypertension during pregnancy can increase risk of health problems in later life. Many written responses also focused on the link between menopause, healthy ageing, and risk of future health issues such as musculoskeletal conditions. Some also focused on specific conditions which are more prevalent in women or where there are disparities in access to service or outcomes, such as osteoporosis.

Some responses also said that health in the workplace can be particular challenge for older women, who may experience menopause symptoms and other long-term conditions, and who may have caring responsibilities.

Our ambition

Our ambition is that women are supported to age well, and women’s needs are considered specifically and by default in work on long-term conditions and healthy ageing.

Next steps

The government is committed to extending healthy life expectancy by 5 years by 2035, while narrowing the gap between the experience of the richest and poorest. The NHS Long-Term Plan also has a focus on ageing well and ensuring that older people receive the right support to help them live as well as possible.

We will explore specific conditions and areas of healthcare in which disparities between men and women are greatest, including long-term conditions such as osteoporosis, and will set out this work in the strategy. We will also work alongside other programmes of work to share insight from the call for evidence, and to ensure greater consideration of women’s health-specific implications.

Mental health

What we’ve heard

In the call for evidence survey, mental health was in the top five most popular topics selected by respondents for inclusion in the Women’s Health Strategy (selected by 39% of respondents), and this was consistent across every age group.

Overall, 65% of women felt, or were perceived to feel, comfortable talking to friends about mental health conditions. This dropped by 13 percentage points to 52% when talking to family members. Only 34% of respondents said that they, or the woman they had in mind, had access to enough information on mental health conditions; however, this varied by age, gender identity, and health status. Mental health was also a common example used when respondents were asked to give an example of an area in which they felt that they had not been listened to by a healthcare professional.

We heard from respondents that mental health should be given equal consideration to physical health, and that a focus should be given to disparities in access and experiences of mental health care. Responses also highlighted the impact of domestic abuse and violence against women and girls (VAWG) on the mental health of women across the life course, and the ways in which this intersection should be addressed.

Many respondents flagged that they would like to see improved access to mental health services, and that they had struggled to access mental health services and support during the pandemic. More specifically, respondents highlighted that better mental health support in the workplace would help them, or had helped them, to reach their full potential.

Our ambition

Our ambition is to prevent the onset of mental health conditions wherever possible, address disparities in outcomes, and ensure equitable access to specialist support for those who are struggling with their mental health. Our plans must take account of differential experiences of women if we are to successfully reduce disparities in mental health outcomes.

Next steps

We recognise that mental health is a key issue for women, which intersects across the whole life course. In the forthcoming strategy we will set out our broader approach and aim to examine further the ways in which differential factors such as sex, pre-existing mental or physical health conditions, or ethnicity may impact the likelihood of a woman developing a mental health condition, and the outcomes they experience.

The health impacts of violence against women and girls (VAWG)

What we’ve heard

In the call for evidence survey, the health impacts of violence against women and girls was the eighth most selected topic that respondents picked for inclusion in the Women’s Health Strategy (30%). For those who belong to the mixed/multiple ethnic group, and those who identify with a gender different to their sex registered at birth, and those in younger age groups (aged 16 to 17, 18 to 19, 20 to 24 and 25 to 29), the health impacts of violence against women and girls featured in their top five topics selected for inclusion in the strategy (rather than the menopause, which took precedence for other groups).

Respondents highlighted that the effects of domestic abuse and VAWG on women’s health are wide ranging and extensive, and can have long-term impacts on an individual’s physical and mental health. We also heard that health settings should be a trusted environment which provide a primary interface for victims and survivors to access support. However, in the public survey, only 9% of respondents felt that they had enough information about specialist NHS services such as female genital mutilation (FGM) clinics or sexual assault referral areas.

We heard from organisations that access to services for domestic abuse survivors is lacking, and that more local, free services are needed. We also heard from organisations that women who have experienced sexual violence and abuse may have a range of health needs, and that these may vary depending on their ethnicity, disability, income, age and sexual orientation.

Our ambitions

Our ambition is that women and girls who are victims of violence and abuse are supported by the healthcare system and in the workplace, and the healthcare system takes an increased role in prevention, early identification and provision of support for victims.

Next steps

In the strategy we will set out our plans to build the evidence base on the impacts of trauma-informed practice and to better support victims of VAWG. We will also take forward work to consider the ways in which workplaces can be made more supportive and safer for women and other victims of violence and abuse.

We will continue to implement our commitment to ban virginity testing through the recent government amendment to the Health and Care Bill. We will also commit to introduce legislation to ban hymenoplasty at the earliest opportunity, following the recommendations of the expert panel on hymenoplasty which we established to investigate this procedure.

9. Next steps for developing the Women’s Health Strategy

In this publication we have set out Our Vision for the Women’s Health Strategy. This vision provides a new strategic framework for women’s health, based around a life course approach and the five key themes which connect different aspects of women and girls’ health, as well as different conditions and issues which arise at different points during the life course.

The actions set out in this vision are just the first step in delivering our ambition to improve experiences of healthcare services and health outcomes for women and girls, and to reduce disparities in women’s health.

We will publish a strategy that will set out more detailed delivery plans against each theme and against specific health needs and conditions, aligned with this vision. In the strategy we will set out concrete proposals both on issues that only affect women and girls, and on issues that affect everyone but where there are sex-based differences in prevalence, experience, or outcomes.

This strategy will be published in spring 2022.