PHE Screening inequalities strategy

Updated 22 October 2020

Note that Public Health England was disbanded in 2021. Its functions were taken over by the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID) in the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), and NHS England (NHSE).

The world-leading national NHS screening programmes save lives, improve health and enable choice. Every year across the UK around:

- 5,000 deaths are prevented by cervical screening[footnote 1]

- 2,400 bowel cancer deaths are avoided through screening[footnote 2]

- breast screening prevents 1,300 women dying of breast cancer every year[footnote 3]

- 7,000 people with sight-threatening diabetic retinopathy are referred to hospital eye services for urgent treatment[footnote 4]

- 2,500 men have a potentially life-threatening aneurysm detected[footnote 5]

- 1,000 babies, who may otherwise have been born with HIV are born free of the condition[footnote 6]

- 1,100 babies with hearing problems are helped to reach full educational and social potential through early diagnosis and treatment[footnote 7]

In addition, 24,000 fewer invasive tests were carried out over the last 10 years due to improved Down’s syndrome screening. These tests carry a small risk of miscarriage.

National screening programmes are population-based, meaning that a test is offered to everyone in a defined population group (for example, all women aged 50 to 70 or every newborn baby). Many of the conditions for which we offer screening and treatment disproportionately affect individuals from socioeconomically deprived backgrounds or those with the 9 protected characteristics, as described in the 2010 Equality Act. National screening programmes, therefore, have an important role to play in reducing health inequalities.

Variation in participation exists both within and between national screening programmes and, generally, people at higher risk of the condition being screened are less likely to participate.

In September 2015, Public Health England (PHE) Screening held a stakeholder workshop on inequalities in screening. The workshop demonstrated huge enthusiasm for addressing inequalities in screening. It identified a number of actions and, more significantly, it proposed that these should be developed into an overarching strategy to address what work PHE Screening could take forward to support local partners (including NHS England, local authorities, clinical commissioning groups (CCGs), primary care, providers and the third sector) to reduce inequalities in screening.

Work to address inequalities in screening is progressing both locally and nationally, but there is still more to be done to overcome the challenges we face. It is essential that we continue to explore how screening can be more effective at reaching those in greatest need. The time is right to bring this work together into a cohesive and coordinated strategy to reduce screening inequalities and make sure there is informed personal choice and equitable access for all.

PHE exists to protect and improve the public’s health and wellbeing and reduce health inequalities. We do this through world-class science, advocacy, partnership, education, knowledge and intelligence, and the delivery of specialist public health services.

PHE Screening works to support those responsible for the commissioning and local delivery of national screening programmes. This work includes a joint effort to promote equitable access to screening services.

Legislation

The health inequalities duty (Health and Social Care Act 2012)

The Health and Social Care Act 2012 introduced specific legal duties on health inequalities for the Secretary of State for Health, which PHE must meet on his behalf. The duty requires public authorities to have due regard to the need to reduce inequalities between the people of England with respect to the benefits they can obtain from the health service. It applies to all PHE public health functions, not just healthcare-focused work.

The public sector equality duty (Equality Act 2010)

The equality duty is a responsibility on public bodies and others carrying out public functions, which ensures they consider the needs of all individuals in their day-to-day work in shaping policy and delivering services, and in relation to their own employees. In the exercise of their functions, public bodies have a general duty to have due regard to the need to:

- eliminate unlawful discrimination, harassment and victimisation and other conduct prohibited by the Act

- advance equality of opportunity between people who share a protected characteristic and those who do not

- foster good relations between people who share a protected characteristic and those who do not

The Public Services (Social Value) Act 2013

This act requires people who commission public services to think about how they can also secure wider social, economic and environmental benefits.

The Accessible Information Standard

This standard ensures that people with a disability, impairment or sensory loss are given information in a way they can access and understand and any communication support they need.

Background

The strategy has been developed to support PHE Screening in discharging its professional and legal commitment to reduce inequalities, ensure equitable access to screening and to support its partners involved in the delivery of screening. This strategy is consistent with the PHE equality objectives: 2017 to 2020 and PHE’s Strategic Plan.

PHE produces evidence, resources and guidance to help support national, regional and local areas to reduce health inequalities.

The commissioning and delivery arrangements for screening, set out in the Immunisation and Screening National Delivery Framework and Local Operating Model mean that public health system leadership is required to tackle screening inequalities by establishing effective partnerships with local communities, third sector organisations commissioners, providers and local authorities.

In the future, ‘sustainability and transformation partnerships’ (STPs) and emerging accountable care systems and organisations are expected to shape further the commissioning and service delivery landscape.

This strategy seeks to address the unwarranted and unfair barriers that may mean people do not engage with an offer of, or participate in, screening or who are disadvantaged in maximising the benefits of screening. Examples of barriers to screening include physical and communication barriers, as well as cultural and social barriers.

Informed personal choice is central to the screening strategy. The decision to have a screening test or not is for the individual involved. The decision will be consistent with the values of the individual and their unique circumstances and should be free from pressure.

However, many people choose not to make a decision about screening, are not aware of the offer or simply do not attend their appointment or complete the self-test.

There is therefore an opportunity for stakeholders to engage further with this group of people. This engagement might include targeted community awareness initiatives, perhaps with community groups or faith leaders, as well as the provision of individual support and advice. It will also require services to address any barriers they might present.

We must also recognise that there will always be some degree of variation between different groups in their acceptance of a national screening programme.

The strategy’s development has been overseen by a strategy oversight group, made up of a range of stakeholders, including NHS England, PHE, local authorities and the third sector.

Screening is a way of identifying apparently healthy people who may have an increased risk of a particular condition with the aim of providing treatment to prevent the disease or illness arising from it.

The NHS screening programmes currently offered in England save lives, reduce illness and disability and promote choice. They are:

- NHS abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) programme

- NHS bowel cancer screening (BCSP) programme

- NHS breast screening (BSP) programme

- NHS cervical screening (CSP) programme

- NHS diabetic eye screening (DES) programme

- NHS fetal anomaly screening programme (FASP)

- NHS infectious diseases in pregnancy screening (IDPS) programme

- NHS newborn and infant physical examination (NIPE) screening programme

- NHS newborn blood spot (NBS) screening programme

- NHS newborn hearing screening programme (NHSP)

- NHS sickle cell and thalassaemia (SCT) screening programme

The aims of screening programmes are for:

- pregnant women, to offer women and their families screening tests to learn the likelihood that they or their baby has a higher chance of a specific health problem or congenital condition and, where appropriate, to receive early treatment and/or to support the process of making an informed decision

- newborn babies, to offer parents screening tests to identify certain medical conditions, or increased risk of conditions in their baby before becomes symptoms occur so that their baby can be offered an intervention or treatment that can reduce morbidity and mortality

- young people and adults, to offer information and training packages to support individuals to make personal choices and guide professionals in facilitating informed personal screening choices

Screening is a pathway, not just a test. Having offered a test, health care providers have an obligation to make sure that the individual is cared for throughout their screening journey.

All national screening programmes participate in regular quality assurance activities as led by the Screening Quality Assurance Service (SQAS), to drive continuous service improvement.

Screening inequalities and the case for action

Health inequalities are systematic, avoidable and unjust differences in health and wellbeing between different groups of people[footnote 8]. These differences arise from the wider social determinants of health as illustrated in Dahlgren and Whitehead’s model depicting the wider determinants of health, which includes:

- general socioeconomic, cultural and environmental conditions

- living and working conditions

- social and community networks

- individual lifestyle factors

- age, sex and hereditary factors

The Marmot review Fair Society, Healthy Lives (2010), a strategic review of health inequalities in England, highlights the social gradient of health inequalities from which the more disadvantaged the person’s social position, the worse their health. The review highlights the need for universal action that increases in scale and intensity in proportion to the level of disadvantage.

Health inequalities arise from:

- structural issues, the fundamental ‘causes of the causes’ are differences in experiences of the wider determinants of health between groups. For example, income, employment, education and housing, which influence people’s position in society

- unhealthy behaviours and other individual risks. We know that health behaviours are not equally distributed across the population and this difference contributes to inequalities in premature death

- inequitable access to or experience of services, which can be a result of discrimination due to inaccessible services, public information or healthcare sites that is relevant pertinent to their particular needs. For example, services that fail to make reasonable adjustments required by the Equality Act 2010

Health inequalities in England exist across a range of dimensions or characteristics and include some of the 9 protected characteristics of the Equality Act 2010, socioeconomic position and geography.

These dimensions include those who are not registered with a GP, homeless people and rough sleepers, asylum seekers, gypsy and traveller groups, sex workers, those in prison, those experiencing severe and enduring mental health problems, those with drug or alcohol harm issues and those with communication difficulties.

Screening stakeholders are limited in their ability to influence the structural causes of health inequalities but do have scope to address inequitable access to or experience of screening.

Screening inequalities can manifest themselves at any point along the screening pathway. The pathway consists of:

- cohort identification (invitation)

- provision of Information about screening

- access to screening services

- access to treatment

- onward referral

- outcomes

The inequalities may be at:

- national programme level

- regional level

- local programme level

- small geography (for example, local authority, hospital catchment or GP) level

Barriers that persist once a person has commenced the screening pathway may result in some people being unable to maximise the benefits of screening. For example, if a person has a higher chance result but does not get the follow-on treatments, they will not reduce their risk.

We know these inequalities in screening exist. However, we do not know the full extent of inequalities within all our screening programmes, because:

- we do not currently collect the relevant data

- data may be collected on IT systems but not easily accessible to us

- there is a lack of evidence on the reasons for the inequality and how we can effectively tackle the issues

The actions we take need to provide us with the information necessary to reduce the impact of inequalities in screening.

Examples of inequalities in screening include:

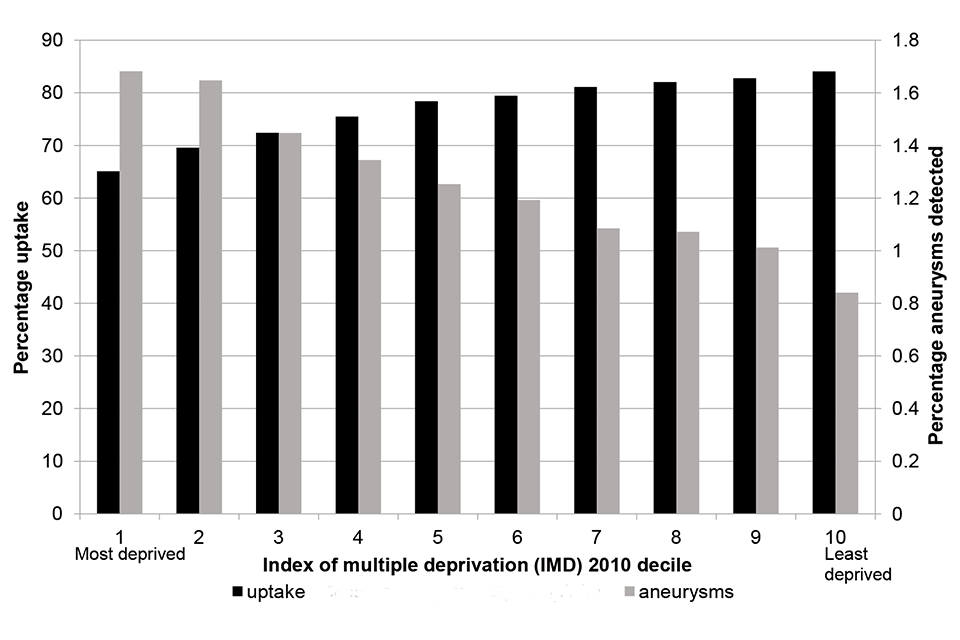

- within the NHS AAA screening programme those people experiencing social deprivation are less likely to attend and participate in screening and the proportion of aneurysms detected is inversely correlated with increasing deprivation

The figure below shows the uptake of AAA screening with prevalence of AAA by deprivation index (IMD 2010 decile), 1 April 2013 to 31 March 2015.

Uptake of AAA screening with prevalence of AAA by deprivation index (IMD 2010 decile), 1 April 2013 to 31 March 2015

| IMD 2010 decile | Screening uptake % | Aneurysms detected % |

|---|---|---|

| Decile 1 (most deprived) | 65.1 | 1.68 |

| Decile 2 | 69.6 | 1.65 |

| Decile 3 | 72.4 | 1.45 |

| Decile 4 | 75.5 | 1.34 |

| Decile 5 | 78.4 | 1.25 |

| Decile 6 | 79.5 | 1.19 |

| Decile 7 | 81.1 | 1.08 |

| Decile 8 | 82.0 | 1.07 |

| Decile 9 | 82.8 | 1.01 |

| Decile 10 (least deprived) | 84.1 | 0.84 |

- people in more deprived groups are less likely to complete bowel screening (35% for the most deprived group compared to 61% for the least deprived)[footnote 9] and are more likely to die from bowel cancer[footnote 10]

- women in the most deprived groups (most deprived quintile) are less likely to attend cervical screening (odds ratio (OR) 0.91 to 0.94 when compared to the least deprived quintile[footnote 11]) yet are more likely to have high-risk HPV, and a higher risk of being diagnosed with/dying from cervical cancer[footnote 12]

- women in the most deprived groups are generally less likely to participate in breast screening (relative risk (RR) 0.89 for the most deprived groups compared to the least deprived)[footnote 13] but are more likely to die from breast cancer[footnote 14]

- uptake of bowel screening in England is lower in the ethnically diverse areas (38% compared to 52% to 58% in other areas)[footnote 15]

- women from ethnic minority groups are less likely to attend cervical screening compared to White British women (OR 2.20 for White British women compared to ethnic minority women)[footnote 16] – the disparity is particularly great for certain ethnic minority groups. For example, the likelihood of non-attendance reaches OR 10.69 and OR 12.86 for Indian and Bangladeshi women respectively compared to White British women[footnote 17]

- there is some evidence that women from ethnic minority groups are less likely to attend breast screening compared to White British women, but estimates vary by study and by minority ethnic group[footnote 18]

- people from South Asian communities are known to be up to 6 times more likely to have type 2 diabetes than the general population; in addition, this population group tend to have poorer diabetes management, putting them at higher risk of serious health complications including diabetic retinopathy – data analysed from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) showed the prevalence of diabetic retinopathy to be highest in the South Asian population and also in the most deprived geographical group[footnote 19]

- in cervical screening, uptake is markedly higher among 50 to 64-year-olds than among 25- to 49-year-olds [footnote 20]

- women with disabilities are less likely to participate in breast screening (RR 0.64 compared to those without disabilities) – this is particularly the case for those with disabilities relating to self-care or vision, or for those with 3 or more disabilities[footnote 21]; women with learning disabilities are also less likely to participate in breast screening (incident rate ratio (IRR) 0.76 compared to those without learning disabilities)[footnote 22]

- women reporting any disability are less likely to participate in bowel screening (RR 0.75 compared to those without disabilities) – this is particularly the case for those with disabilities relating to self-care or vision, or for those with 3 or more disabilities[footnote 23] – people with learning disabilities are also less likely to participate in bowel screening (IRR 0.86 compared to those without learning disabilities)[footnote 24]

- women with learning disabilities are less likely to participate in cervical screening (IRR 0.54 compared to those without learning disabilities)[footnote 25]

- men have a lower uptake of bowel screening (51% compared to 56% for women)[footnote 26] but are more likely to be diagnosed and die from bowel cancer (male:female ratio 12:10)[footnote 27]

- overall, there is limited published evidence on inequalities in antenatal and newborn screening programmes; however, 2013 UK research using large survey data consolidated evidence that single women, those from ethnic minorities and younger women are more likely to make late bookings for antenatal care, have fewer antenatal checks and engage less with screening[footnote 28]

- in NHS London an equity audit undertaken in 2015 to 2016 found:

- evidence of inequalities in access to timely antenatal care across London

- many of the characteristics of women at greater risk of booking at more than 10 weeks gestation were also associated with social disadvantage, poorer pregnancy outcomes and poorer infant health

- there was considerably longer wait from referral to booking for women living in higher deprivation areas

- for several maternal characteristics (including a first language other than English, Jewish religion, unemployment and most black and minority ethnicities), a later referral is compounded by a longer wait from referral to booking

However, even when people who experience health inequalities attend for screening, the system and process may disadvantage them from maximising the benefits of screening.

Reducing health inequalities in screening can bring significant savings to both the individual and the NHS. For example:

- we know that patients diagnosed with bowel cancer through screening and elective routes have higher survival rates compared with patients diagnosed through emergency presentations

- for cervical cancer screening, the later the diagnosis, the more invasive the treatment options and the poorer the health outcomes; long-term modelling by Jo’s Cervical Cancer Trust has found incidence of cervical cancer is set to increase substantially in older women if current coverage of cervical screening remains the same – by 2040, incidence will increase by 16% among 60- to 64-year-olds and 85% among 70- to 74-year-olds [footnote 29]

- the NHS CSP cervical cancer audit, 2007 to 2010, found 56% of women aged 50 to 64 with fully invasive cancer had not been screened within 7 years, compared to only 16% of women without cervical cancer

We can do more to support individuals make an informed personal choice about whether to accept the offer of screening. However, behavioural change theory shows how complex this process can be. Community, cultural and economic factors all have an influence on the choices individuals make, as does access to screening services which are often worse in areas with the greatest need.

Strengthening efforts to understand and engage with specific community groups can help to address variations in participation. Jo’s Cervical Cancer Trust’s Cervical screening in the spotlight contains examples of campaigns or activities to target specific groups of women who had not engaged with screening.

There are significant challenges to be addressed in reducing screening inequalities, for example:

- training, recruitment and retention of specialist screening staff

- limited capacity within screening and immunisation teams and in the wider public health system

- the collection of core demographic data is compromised by deficiencies in some screening and national IT systems which can make assessing and evaluation effectiveness of service innovation harder

- limited resources for monitoring and the complex evaluation of screening inequalities

- the lack of timely access to data to enable monitor the impact of interventions

Vision, aim and objectives

Our vision is that all screening services can be accessed by all communities and that everyone, regardless of their social and personal circumstance, has an opportunity to make an informed personal choice about screening.

Our aim is to enable informed choice and reduce health inequalities across all programmes.

Our objectives are to:

- provide leadership and strategic direction to tackle inequalities in screening

- provide those responsible for the delivery and commissioning of screening services with the evidence and tools they need

The evidence and tools will:

- identify screening inequalities

- ensure pathways are designed that take account of the needs of people less likely to engage in screening

- engage with local communities and eligible screening groups, to understand barriers to screening

This will happen by:

- focusing on interventions that can have the greatest impact

- making evidence-based contributions to policy debate and to the wider system that support reductions in health inequalities

- influencing government and our partners to raise the profile of inequalities in screening

- empowering local action, recognising and supporting best practice, building innovation and facilitating sharing

- working collaboratively with local authorities and other partner organisations responsible for place-based community engagement

- using research to identify and address barriers that prevent people and communities from engaging with or participating in screening

- supporting informed personal choices with the provision of accessible, fit for purpose information and education for the public and health care staff

Workstreams

This section provides a brief summary of recent actions to tackle inequalities in screening.

Following recommendation by the UK National Screening Committee, PHE Screening worked with partners to accelerate replacement of the guaiac faecal occult blood test (gFOBt) with the faecal immunochemical test (FIT) in the bowel screening programme. A pilot of FIT in 2014 showed a marked impact on uptake, with a 7% increase overall, equivalent to an additional 290,000 participants per annum. It increased uptake in groups with low participation rates such as men, ethnic minority populations and people in more deprived areas[footnote 30].

PHE Screening commissioned a group to guide research into using FIT and additional risk factors to improve the accuracy of the screening test. These indicators include delayed or infrequent participation, which are particularly associated with deprivation and ethnic minority groups. When combined with FIT, these markers improve the detection of cancer and adenomas.

A PHE Screening Data Group is developing information about the availability of core screening data (Key Performance Indicators and standards) against the protected characteristics. This will support national and local research in relation to inequalities and public health initiative planning.

PHE Screening’s NHS CSP team has worked in partnership with NHS Digital and Jo’s Cervical Cancer Trust to produce an electronic data package. The package will support GP practices and CCGs to look at local screening access and coverage rates.

PHE Screening’s NHS AAA screening programme is developing an inequalities toolkit to give local providers clear data, enabling them to identify areas of inequality in their local area(s), produce guidance to enable local providers to use data to reduce inequalities and increase coverage within their local area(s). The toolkit will also share examples of good practice.

PHE Screening has a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to allow sharing of data with NHS England and public health commissioning teams. This MOU also enables NHS England to share data with other delivery partners including the Local Authority Directors of Public Health.

PHE Screening commissioned a rapid review of interventions to improve participation in cancer screening services.

Where we have good quality evidence, PHE Screening uses this information to inform revisions to national screening service specifications. For example, service specifications for cancer screening now include references to text messaging, timed appointments, reminder letters and GP endorsed appointment letters.

We know there is a great breadth of activity taking place across England to reduce inequalities in screening programmes. PHE Screening has introduced a mechanism to share good practice. This provides an opportunity to share innovative work to reduce inequalities with delivery partners.

PHE Screening and NHS England commission and provide IT systems to support screening programmes. These are variable in quality and how much of the pathway they cover. PHE Screening will, where possible, work to include protected characteristics into all screening data sets. PHE Screening will also work with suppliers and NHS England to include the ability to support a choice of alternative communication types (SMS messaging, email).

The NHS BSP and BCSP IT services have an additional care-needs flag. Where GP practices have obtained consent from their patients to share information about additional care needs, this enables the programme to notify, for example, learning disability teams of imminent invitations to take part in screening. A project is being taken forward to enable this additional care needs flag to be populated directly from a spine data feed which in turn will be populated by GPs.

PHE Screening will share learning on inequalities and share best practice through our PHE Screening blog.

National screening programmes have defined standards and guidance to ensure that services are safe, effective and of high quality. These are reviewed on a regular basis to drive improvement and understand the impact of standards on inequalities. Each programme has coverage and/or uptake standards to monitor and maximise uptake of screening in the eligible population who chose to accept screening. In addition, some screening programmes have developed standards to focus on specific areas that are or may be linked to inequalities. For example, diabetic eye screening has a standard to help identify patients who regularly miss screening appointments, and sickle cell and thalassaemia screening has developed a standard on the timeliness of offer or prenatal diagnosis.

A PHE Screening standards subgroup has been established and part of the group’s work is to explore and develop new standards to help monitor inequalities.

PHE Screening has produced high-quality information to support informed choice in screening. All information meets the Accessible Information Standard. We provide screening information in English and 12 other languages. A leaflet for trans (transgender) and non-binary people in England has been produced to explain the adult NHS screening programmes that are available in England and explains who we invite for screening. We are developing easy read leaflets across all screening programmes.

PHE has developed e-learning modules on health equity. PHE Screening is undertaking an in-house public health skills audit to make the best use of existing expertise, share learning and target training. All PHE Screening staff can access PHE’s Health Equity Assessment Tool (HEAT) to inform all major programmes of work and support them to systematically assess health inequalities.

PHE Screening works with its partners, including:

- colleagues within PHE leading on learning disabilities to take forward work to improve access to screening for people with these conditions

- the PHE health and justice team to develop a pathway to ensure all people in prison are offered screening for bowel cancer, abdominal aortic aneurysm and diabetic eye screening

- colleagues in NHS England to measure and improve NHS performance, by sharing data, providing clear evidence-based service specifications. We contribute to and follow up on actions from NHS England spotlight sessions on falling uptake in breast cancer and cervical screening

- the third sector, for example, supporting Jo’s Cervical Cancer Trust in their launch of Be Cervix Savvy Roadshows

The operating model for the screening quality assurance service (SQAS) 2018 and 2019 to 2020 and 2021 has identified a goal to contribute to the reduction of health inequalities across screening programmes. This will be measured by improvement trends identified from quality assurance visit reports and action plans. To support this goal, SQAS will take forward a QA inequalities plan of work that will ensure staff have access to the necessary tools, resources and training to enable the systematic and effective QA service actions to reduce screening inequalities.

PHE Screening will build on these actions and continue to support those in the health system with responsibility for the delivery of screening programmes. Updates will be reported through established communications channels, such as blogs.

Monitoring progress

PHE Screening will use a number of different mechanisms to engage with stakeholders, evaluate the strategy and demonstrate progress. This will include:

- the use of blogs to allow for ongoing stakeholder updates, input and feedback

- identification or development of measurable indicators focusing on tackling health inequalities

- collecting, collating and reporting on information gathered through formal and informal QA team contacts and visits

We will seek views on the strategy and its usefulness formally over time.

Governance

Equality is an objective for PHE Screening and the actions will be monitored and reported through PHE Screening, health improvement and PHE corporate scorecards.

-

Petro et al, The cervical cancer epidemic that screening has prevented in the UK, Lancet 2004; 364: 249 – 56 ↩

-

Parkin, D.M, Tappenden, P, Olsen, A.H., Patnick, J., Sasieni,P., Predicting the impact of the screening programme for colorectal cancer in the UK, Journal of Medical Screening, 2008. 15:p. 163 – 174 ↩

-

The Independent Review on Breast Cancer Screening, the Benefits and Harms of Breast Cancer Screening, October 2012 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3693450/ ↩

-

NHS Diabetic Eye Screening Programme ↩

-

NHS Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Screening Programme ↩

-

Peters H, Francis K, Sconza R, Horn A, Peckham C, Tookey PA, Thorne C. UK Mother-to-Child HIV Transmission Rates Continue to Decline: 2012-2014. Clin Infect Dis. 2017 Feb 15;64(4):527-528 ↩

-

UK NSC – Screening in England 2012/13 Annual Report ↩

-

Whitehead M. The concepts and principles of equity in health. Int J Health Serv 1992;22:429–445. (first published with the same title from: Copenhagen: World Health Organisation Regional Office for Europe, 1990 (EUR/ICP/RPD 414)) ↩

-

Von Wagner, C., et al, 2011. Inequalities in participation in an organized national colorectal cancer screening programme: results from the first 2.6 million invitations in England. International Journal of Epidemiology, 40(3), pp. 712-718 ↩

-

CRUK, 2016. Statistics by Cancer Type: Bowel Cancer. [Online] Available at https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/bowel-cancer [Accessed 11 2017] ↩

-

Tanton, C., et al, 2015. High-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and cervical cancer prevention in Britain: Evidence of differential uptake of interventions from a probability survey. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers, and Prevention, Volume 24, pp. 842-853 ↩

-

CRUK, 2016. Statistics by Cancer Type: Cervical Cancer. [Online] Available at https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/cervical-cancer [Accessed 11 2017] ↩

-

Douglas, E., et al, 2016. Socioeconomic inequalities in breast and cervical screening coverage in England: are we closing the gap?. Journal of Medical Screening, 23(2), pp. 98-103 ↩

-

CRUK, 2016. Statistics by Cancer Type: Breast Cancer. [Online] Available at https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/breast-cancer [Accessed 11 2017] ↩

-

Von Wagner, C., et al, 2011. Inequalities in participation in an organized national colorectal cancer screening programme: results from the first 2.6 million invitations in England. International Journal of Epidemiology, 40(3), pp. 712-718 ↩

-

Moser, K., et al, 2009. Inequalities in reported use of breast and cervical screening in Great Britain: analysis of cross-sectional survey data. British Medical Journal, Volume 338, p. b2025 ↩

-

Marlow, L. A. V., et al, 2015. Understanding cervical screening non-attendance among ethnic minority women in England. British Journal of Cancer, 113(5), pp. 833-839 ↩

-

Estimating attendance for breast cancer screening in ethnic groups in London. BMC Public Health, 10(157). Jack, R. H., et al, 2014. Breast cancer screening uptake among women from different ethnic groups in London: a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open, 4(10). Moser, K., et al, 2009. Inequalities in reported use of breast and cervical screening in Great Britain: analysis of cross-sectional survey data. British Medical Journal, Volume 338, p. b2025 ↩

-

Diabetic eye disease: A UK Incidence and Prevalence Study, Authors: Rohini Mathur, Ian Douglas, Krishnan Bhaskaran, Liam Smeeth, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Year of publication: 2017 ↩

-

HSCIC 2015 http://digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB15968 ↩

-

Floud, S., et al, 2017. Disability and participation in breast and bowel cancer screening in England: a large prospective study. British Journal of Cancer, 117(11), pp. 1711-1714 ↩

-

Osborn, D. P., et al, 2012. Access to cancer screening in people with learning disabilities in the UK: cohort study in the health improvement network, a primary care research database. PLoS One, 7(8), p. e43841 ↩

-

Floud, S., et al, 2017. Disability and participation in breast and bowel cancer screening in England: a large prospective study. British Journal of Cancer, 117(11), pp. 1711-1714 ↩

-

Osborn, D. P., et al, 2012. Access to cancer screening in people with learning disabilities in the UK: cohort study in the health improvement network, a primary care research database. PLoS One, 7(8), p. e43841 ↩

-

Osborn, D. P., et al, 2012. Access to cancer screening in people with learning disabilities in the UK: cohort study in the health improvement network, a primary care research database. PLoS One, 7(8), p. e43841. ↩

-

Von Wagner, C., et al, 2011. Inequalities in participation in an organized national colorectal cancer screening programme: results from the first 2.6 million invitations in England. International Journal of Epidemiology, 40(3), pp. 712-718 ↩

-

CRUK, 2016. Statistics by Cancer Type: Bowel Cancer. [Online] Available at https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancertype/bowel-cancer [Accessed 11 2017] ↩

-

https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2393-13-196 ↩