Migration Advisory Committee (MAC) annual report, 2022 (accessible)

Updated 31 January 2023

Foreword

The framework document that covers our governance requires us to produce an annual report to inform Parliament and the public of the work we have done and our use of resources. It also suggests that the report contain comment on, and recommendations relating to, all aspects of the immigration system.

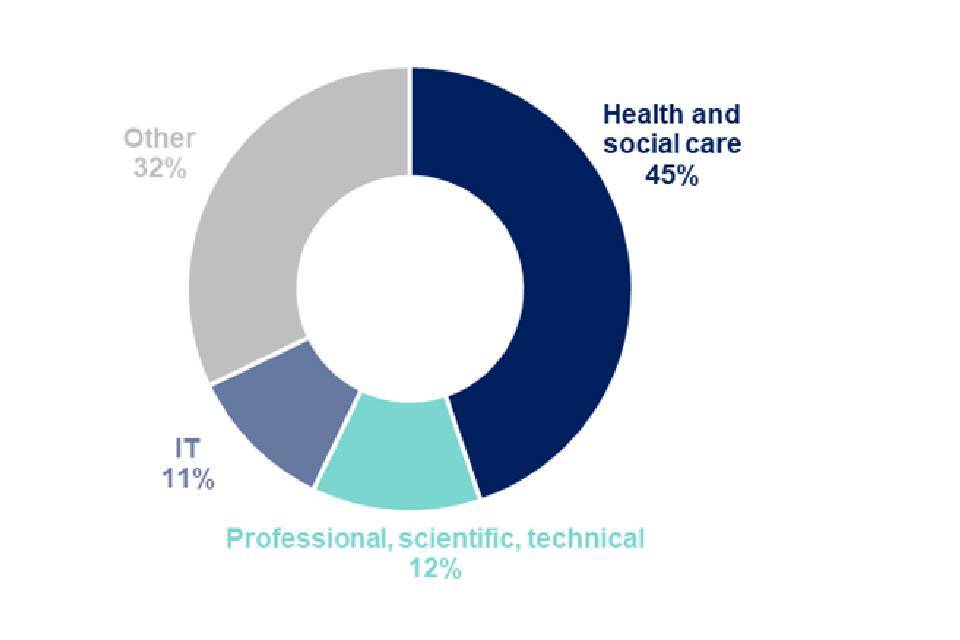

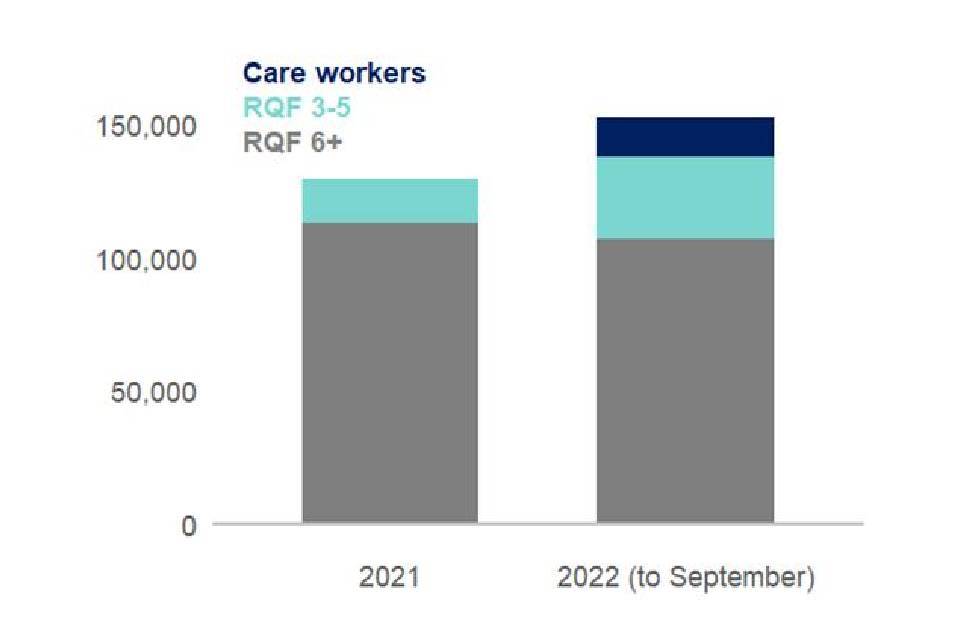

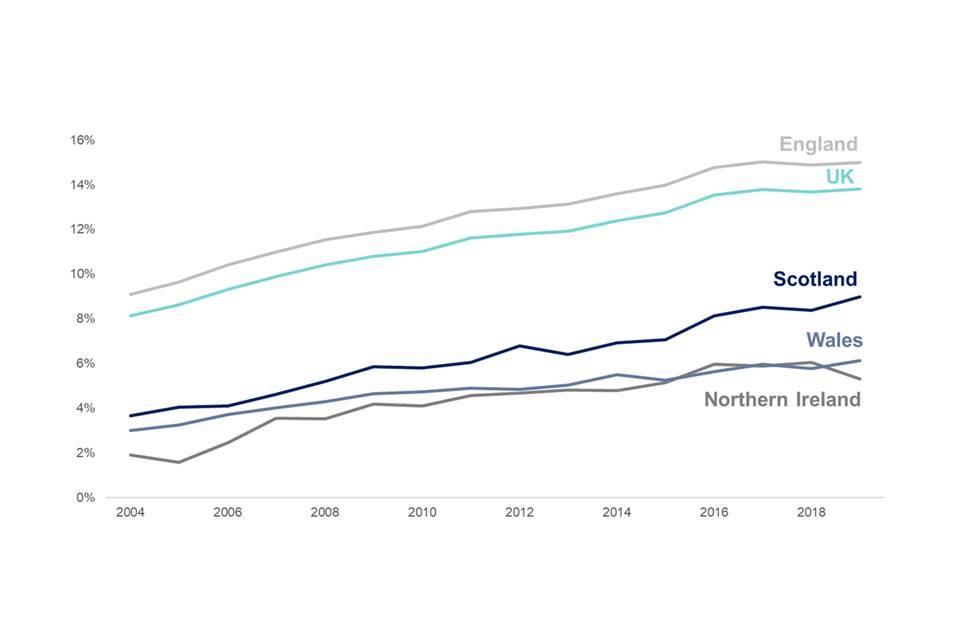

We completed our enquiry into the impact of the ending of Freedom of Movement on the Adult Social Care Sector in April and submitted the report to Government and Parliament. We recommended that care workers continue to be eligible to apply for a Health and Care Worker visa and made some additional recommendations for changes to the immigration system to ease the burden on social care employers and migrants. However, our main recommendation was that a minimum rate of pay should be established for care workers at a premium to the statutory minimum wage where care is being provided with public funds. We suggested that this should initially be set at £1 per hour above the National Living Wage but expected a more substantial premium to be needed to properly address the crisis in social care recruitment and retention. It is deeply disappointing that the Government have still not responded to our report. We note that the Governments of Scotland and Wales are taking clear action to address low pay in the sector and are bewildered by the lack of urgency exhibited by the Department of Health and Social Care.

Net migration in the 12 months to June 2022 reached 504,000, an increase of 331,000 compared to the previous year. A significant part of the rise was due to recently introduced visa routes such as those for Ukraine and Hong Kong citizens. In the short term, new visa routes lead to a sharp rise in net migration (since new people enter under these routes and few leave) but this will likely taper quickly as new visa issuance falls and some on the routes return to their country of origin. There has also been a significant rise in the number of international students coming to the UK. Since the vast majority will leave the UK after their studies are ended, most of the rise in net migration is likely to be temporary. The MAC has also previously highlighted the very substantial benefits that international students bring to the UK. In addition, the work routes have been deliberately designed to be flexible in terms of numbers depending on the state of the economy. When the labour market is tight, as it has been in recent months, we would expect employers to be recruiting more from overseas to address shortages. If, as predicted, the labour market weakens in coming months, we would expect a reduction in worker visa applications. We would caution the Government in becoming too focused on particular net migration numbers, and any change in objective would need to be consistent with the fiscal rules that the Government have in place.

There have been extensive reports in the media and from a variety of pressure groups and research organisations concerning exploitation through the immigration system. We document some of this work in this report and highlight a number of areas where we have concerns over how effectively the system is working to prevent abuse. We also comment on developments in the labour market and how businesses seem to be responding to the new immigration system. In addition, we provide an analysis of the geographic differences in migration across the UK and consider arguments for a more localised immigration policy.

We are again indebted to stakeholders who have taken the time during the year to assist us with our work, both in response to formal commissions and in on-going engagement and have also continued our active engagement with the Devolved Administrations. Finally, the Committee are grateful to the excellent work that the secretariat has done during the year.

We look forward in the coming year to continue in advising the Government on the development of an immigration policy that enhances the welfare of the people of the UK.

Prof. Brian Bell (Chair)

Prof. Dina Kiwan

Prof. Sergi Pardos-Prado

Madeleine Sumption MBE

Prof. Jo Swaffield

1: Migrant exploitation in the labour market

What is exploitation?

Why the MAC is interested in exploitation

Exploitation falls within the MAC’s remit for several reasons. As well as the need to protect migrants, the remit of maximising the welfare of the resident population is also relevant: if employers are able to exploit migrant (or other) workers through low pay and poor conditions then this has the potential to enable circumvention of the standards in the labour market more generally. The Director of Labour Market Enforcement (DLME) states that “Exploitation of workers is not just an offence against the individual – which is serious enough. It also undermines the competitiveness of compliant businesses who treat their workers fairly and with consideration. Worker exploitation can also have a destabilising impact on whole communities.”

A number of recent MAC commissions and papers have included findings relating to exploitation. These have been acquired through Calls for Evidence, qualitative research, discussion with stakeholders and Home Office Intelligence, and examination of the quantitative data. The recommendations we make as part of these commissions often influence the immigration rules. It is therefore imperative that our recommendations work to reduce the potential for exploitation, or at least do not increase the potential for exploitation as an unintended consequence.

Recent MAC commissions have resulted in several recommendations made with exploitation in mind. These include recommendations aimed at ensuring migrants can switch employers and that live-in workers in the social care system should be sponsored by an umbrella body rather than by individuals. Other recommendations and suggestions we have made may link to the reduction of exploitation as a secondary effect, for example the recommendations on English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) access and employment for asylum seekers in our 2021 Annual Report, which would (by increasing access to legal work) reduce reliance on the informal labour market.

What is exploitation?

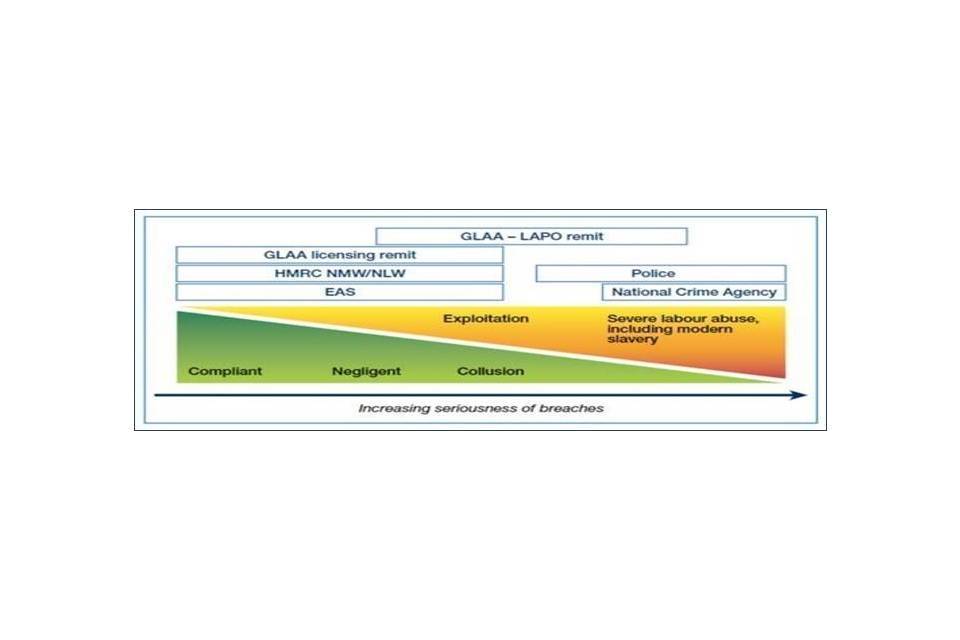

Exploitation is known to exist in the labour market. However, it is undefined in law (Weatherburn, 2021) and there is also no uniform supranational legal framework regulating labour exploitation (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA), 2019). Perhaps for this reason, organisations working in the field of labour market exploitation also do not provide a single definition of exploitation. Spectrum models (such as the one used by DLME shown in Figure 1.1, below) that encompass many forms and degrees of exploitation and levels of severity are often used. We find the DLME conceptualisation to be a particularly useful practical tool that also includes collusion and coercion. An exploitative situation is not necessarily static but may move along this spectrum. The most severe forms of exploitation and abuse, such as modern slavery, are also those where the worker tends to collude least. The forms of exploitation referenced in this diagram are discussed further in the next section.

Figure 1.1: Compliance spectrum across which DLME works

Source: Director of Labour Market Enforcement, 2021.

There is a range of views of what constitutes exploitation as it relates to the labour market. For example, at one extreme, Marx proposed that all capitalist employer/employee relations are inherently exploitative (because the worker does not receive the full value of their labour). Other definitions of exploitation concentrate on coercion or the most flagrant breaches of the law (such as that taken by FRA, 2019, which concentrates on severe labour exploitation: “work situations that deviate significantly from standard working conditions as defined by legislation or other binding legal instruments, concerning in particular remuneration, working hours, leave entitlements, health and safety standards and decent treatment, and which are criminal violations under the legislation of the EU Member State where the exploitation occurs. Hence, severe labour exploitation includes as a minimum coercive form of exploitation…”).

We take exploitation essentially to mean where someone benefits unfairly from another person or group, often their work, or from a situation, especially where the power dynamics are unequal. Even when defining exploitation in this way, the concept is not straightforward. Exploitative situations may arise in many different types of interaction, from personal relationships to criminal activity. For the purposes of this chapter, we have taken the definition of exploitation of migrants in the labour market to cover situations where individual employers are benefiting from workers in a way that is not compliant with their labour rights or general labour market standards. This may include both criminal and non-criminal situations, situations where a migrant colludes with an exploitative situation, and situations where features of the immigration system either facilitate or do not succeed in stopping exploitation. This is a wide definition but fits with the conceptualisation of exploitation as a scale (see above) and also enables the fullest possible examination of how exploitation relates to the conditions attached to migrants’ stay in the UK. We look at exploitation both in terms of the means by which employees may be exploited by employers, and the structural conditions (including features of the immigration system) that allow this to happen.

Many forms of exploitation, such as modern slavery, are illegal. However, migrants may also be exploited within the existing framework of the immigration system, without breaking UK law. Examples may include employees being charged recruitment fees outside the UK or being charged more than market rates for accommodation provided by employers. There are other ways in which migrants are not prevented from being exploited because there is an overall lack of enforcement.

In this chapter we define ‘migrants’ and ‘migrant workers’ as those who are subject to the immigration system, i.e., their continuing stay in the UK depends on meeting the conditions required of them by the immigration system. We exclude those who arrived in the UK as migrants but have subsequently acquired citizenship or Indefinite Leave to Remain (ILR). This differs from the way we generally define migrants, in order to enable us to look specifically at how the immigration system affects exploitation, and how employers are able to use the conditionality of migrants’ stay in the UK to enable exploitation compared to their counterparts whose right to live/work in the UK is not conditional.

We have largely excluded exploitative situations outside the labour market, for example abusive relationships, from the scope of this chapter, other than where these situations constitute a vulnerability that can be exploited by employers wishing to exploit individuals in the labour market. We may explore some of these situations (for example those relating to gendered dimensions or protected characteristics) in future work.

Types of exploitation in the labour market

As the above spectrum suggests, there are a number of ways in which exploitation in the labour market as a whole can be observed, which may apply to all workers and not specifically to migrants: the next section discusses exploitation in relation to migrants specifically. Some examples of exploitation provided in the literature are outlined below, but it is possible for several forms of exploitation to be happening simultaneously. Indeed, low-level violations are often a flag to enforcement bodies that more serious forms of exploitation may be happening – for example, the Gangmaster & Labour Abuse Authority (GLAA) compliance inspection triggers include non-compliance against non-critical licensing standards as a potential indicator of further abuse.

Some factors may increase individuals’ vulnerability to exploitation: these are outlined in a number of research studies and summaries/models (for example IOMs model of migrant vulnerability, 2019) and classified in various ways: for example Focus on Labour Exploitation (FLEX) provides a useful grouping of vulnerabilities as personal (relating to an individual’s characteristics), situational (relating to how an individual is positioned within their environment, including the conditions of being a migrant, with developing English skills or undocumented) or circumstantial (relating to events, for example unemployment). Vulnerabilities may also be pre-existing or ‘created’ (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), 2012).

-

Pre-existing vulnerabilities include poverty, debt, the presence of caring responsibilities that employers know will make it more difficult to move jobs, or discrimination on the basis of race, sex, disability, pregnancy or other personal characteristics (which may include migrant status) (FRA, 2019);

-

‘Created’ vulnerabilities are situations caused by external parties such as employers or systems (including the immigration system and related migrant-specific issues such as trafficking, explored more below) in place. They may also include vulnerabilities created through factors such as romantic attachment, domestic violence, isolation, or addictions.

Although these vulnerability factors do not cause the individual to be exploited, they increase the ease of inducing a migrant to enter an exploitative situation, the difficulty of leaving an exploitative employment situation or of finding an alternative job. Hence, vulnerabilities can compound each other, with a vulnerability in one area setting off a chain of vulnerability in other areas. For example, perpetrators of domestic violence/coercive controlling behaviour may not allow their partner the freedom to choose their own employer or the type of work that they do. This makes it easier for an exploitative employer to take advantage of the worker’s lack of alternatives by maintaining poor employment terms and conditions. As this example implies, some of these vulnerabilities may be experienced more strongly or commonly according to gender or protected characteristics.

Modern slavery, human trafficking, forced/compulsory labour and servitude

There are several different terms that have specific meanings which are or can be forms of exploitation, although it is not necessary for any of these terms to apply for exploitation to be taking place. These forms of exploitation may apply to migrants or to the resident population. Each of these terms has a distinct meaning, although there are also some overlaps between them.

-

Modern slavery and human trafficking are generally understood as being among the most extreme forms of exploitation. Modern slavery is the condition of being ‘owned’ as property. Unsurprisingly, this may involve a high degree of control by the employer, for example being paid into a bank account that is not owned by the individual. Human trafficking is the movement of individuals by others for the purposes of exploiting them and hence links closely to other forms of exploitation. Human trafficking and exploitation are linked, for example in the Human Trafficking and Exploitation (Scotland) Act 2015, which defines human trafficking as being carried out “with a view to another person being exploited” and in the Modern Slavery Act 2015;

-

Forced/compulsory labour and servitude are also similar and encompassed within the Modern Slavery Act 2015. Servitude is similar to slavery, but the victim is not ‘owned’; instead they may live and/or work with someone and be unable to leave. Forced labour is being forced to work, but not agreeing to this freely, for example, working due to being threatened. Although both UK and migrant workers may be at risk of these forms of exploitation, because of their other vulnerabilities, migrants are particularly affected by forced labour in the UK, as demonstrated in a number of studies including qualitative research carried out by Anderson and Rogaly (2005);

-

Forced/compulsory labour, servitude and modern slavery all involve work that the individual does not undertake voluntarily. They may involve unfree recruitment (for example deception regarding the nature of work), the impossibility of leaving the employer (whether because the employer refuses employment transfers, threatens the worker or their family, or because the worker is financially vulnerable because of debts to repay), risk of homelessness or the risk of losing the right to remain in the UK. As with exploitation of other kinds, they may also all involve abuse of vulnerability; deception; restriction of movement; isolation; physical and sexual violence; intimidation and threats; retention of identity documents; withholding of wages; debt bondage; and abusive working and living conditions (International Labour Organisation (ILO), 2012);

-

Labour exploitation in the workplace can include forced/compulsory labour, servitude, and modern slavery, but is explicitly exploitation in the labour market.

Salary non-payment and deductions

Poor employment practices involving salary such as non-receipt of holiday pay, sudden reductions in hours, non-payment of salary, lack of sick pay and non-receipt of payslips/P45 (Barnard et al., 2022) all come under the general umbrella of exploitation, as workers are not receiving what they should be entitled to as employees. Some employers may pay either at unfair levels (e.g., below National Minimum Wage (NMW)) or pay structures (e.g., those depending on unfeasibly high levels of productivity) (FRA, 2019). Weil (2010), in research with US workers, stresses that low wages in themselves constitute a vulnerability which may leave workers open to further exploitation.

Health and safety violations

Exploitative employers may also violate health and safety regulations or good practice, such as by preventing the worker from accessing medical care, taking sick leave, or being without the legal minimum requirement of safety equipment (FRA, 2019; Parliament of Australia, 2016, cited in Sumption and Fernández-Reino, 2018). Migrants in the greatest need of money (such as those on short-term visas, in debt, or who are given few hours or are underpaid), are unsurprisingly particularly vulnerable to this treatment: for example a small-scale survey and qualitative work carried out by Migrant Voice (2022) showed that those in financial difficulty were reluctant to take sick leave or proper rest hours when they needed to.

Precarity

Precarity in the labour market is characterised by intermittent or temporary work that does not enable financial stability, and may not give the worker enough money to live on (Anderson, 2010; Dwyer et al., 2015). Examples of this type of work can include ‘gig economy’ jobs such as delivery and taxi driving but may also include work on zero-hours contracts (such as care work) and jobs in agriculture. Precarity may also involve a lack of work-life balance, as the migrant overworks or works irregular shifts, often linked to the temporary nature of work and life in UK and the need to earn money in a short space of time: “the effect of precarious work is, as it were, the flipside of the celebration of the ‘work-life balance’, when a person’s economic productivity becomes the overwhelming priority” (Anderson, 2010).

Migrants may or may not choose this trade-off (Anderson and Ruhs, 2010): precarity, in itself, is not necessarily a form of exploitation. As noted in the MAC’s 2022 report on Adult Social Care, given some safeguards, zero-hours or variable contracts may suit workers who are balancing work with other commitments. However, precarity can leave workers vulnerable to exploitation because of the power imbalance insecure work creates in employment relationships (Weil, 2010): a survey of union members seeking advice, analysis of case notes, and qualitative work with migrants in low-paid work (FLEX, 2021), for example, provided several examples of power imbalances based on employees’ fear of losing work being worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic. Precarity represents a greater problem for people with fewer choices in the labour market as they are less able to move on if the situation does not suit them.

Precarity can be compounded to cause hyper-precarity (Dwyer et al., 2015; FLEX, 2021), for example by other vulnerabilities (including, for migrants, factors related to the immigration system). This can leave workers with no other choice than to perform exploitative labour (Dwyer et al., 2015), acting as ‘surplus labour-power’ that can be fired and hired to meet demand with little consequence (ibid.).

It is also possible for unscrupulous employers or managers to use precarity as leverage to exploit employees: for example Barnard et al. (2021) describes a situation where “some individuals pay line managers up to £20 cash per week in order to guarantee their shifts, with line managers exploiting and capitalising on the precarity of zero hour contracts”.

The MAC has previously commented (2018) that zero-hours contracts should benefit both the employer and employee, and we restate the importance of this here. While both employers and employees can benefit from the flexibility zero-hours contracts offer, if employers abuse such contracts to enable them to retain large numbers of people who cannot be guaranteed the means to make a living, this is not only unfair to the specific workers involved but degrades standards in the labour market more widely. It can also be harmful to the allocational efficiency of the labour market as a whole if employers are able effectively to reserve a pool of workers who they do not always need, while other sectors of the labour market suffer from unfilled vacancies. We will continue to revisit this issue in future commissions where it is relevant.

Sectors at most risk of non-compliance and exploitation

DLME (2021) describes the sectors it has assessed to be at risk of non-compliance in the labour market for 2021/22 (set out in the table below). Severe, high, and some medium risk sector threats are described as “Vulnerable workers are being exploited, some cases indicative of modern slavery. Many more in the sector are not receiving NMW/NLW”. All at-risk sectors have issues with non-compliance around NMW/National Living Wage (NLW).

Table 1.2: DLME’s assessment of labour market enforcement threats

|

Sector |

2020/21 assessment |

|---|---|

|

Hand car washes |

Severe |

|

Agriculture (horticultural seasonal workers) |

Severe |

|

Care sector |

High |

|

Construction |

High |

|

Hospitality |

Medium |

|

Shellfish gathering |

Medium |

|

Nail bars |

Medium |

|

Poultry and Eggs |

Medium |

|

Warehouses and distribution centres |

Medium |

|

Food industry (processing and packing) |

Medium |

|

Garments and textiles |

Medium |

Source: Director of Labour Market Enforcement, 2021.

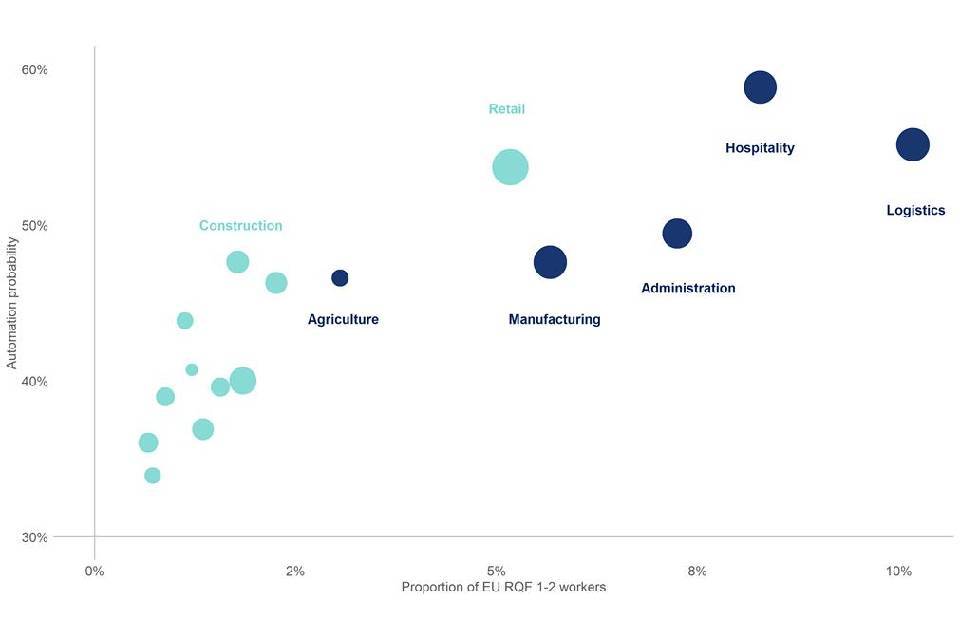

Although exploitation may be found throughout the labour market, there is widespread agreement between various parties with an interest in labour market exploitation about the types of work and sectors most at risk for non-compliance. As DLME’s table above suggests, jobs involving shorter training requirements (particularly at Regulated Qualifications Framework (RQF) 1 - 2 level) appear to be particularly common areas where workers are exploited. The Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner (IASC) (2022) indicates that “Hand car washes, fast fashion, care homes and agriculture are just some of the UK sectors that face distinctive challenges in the UK labour market, from minor non compliances to severe labour exploitation”. Similar industries are identified by the GLAA’s industry profiles where it deems exploitation to be particularly likely. The MAC has also previously raised the risk of non-compliance and exploitation in the construction, hospitality, logistics, manufacturing and food production, car wash, and cleaning industries.

How exploitation affects migrants in the labour market

As set out above, exploitation may be experienced by migrants and non-migrants and at all skill and salary levels. However, being a migrant may either increase the likelihood of some types of exploitation relative to UK workers or make the individual vulnerable to types of exploitation that do not apply to those who are UK citizens or have permanent leave to remain in the UK. There are also several ways in which factors relating to the immigration system in itself may act or combine to increase the risk of exploitation. These are explored further in the next section.

Areas where migrants are comparatively more vulnerable to exploitation than UK workers

Lower levels of English language may reduce migrants’ awareness of/ability to access information on their rights and their ability to report exploitation (DLME, 2021; Sumption and Fernández-Reino, 2018). Lower levels of English language skills may also be associated with increased precarity (Anderson, 2010).

The MAC has historically opposed reducing English language requirements where they exist, partly because this makes migrants more vulnerable to exploitation. This was one of the reasons we expressed concerns about butchers using the Seasonal Worker visa as an alternative to the Skilled Worker route in our 2021 Annual Report. We acknowledge that in some circumstances – such as Intra-Company Transfers – it may be important for reasons of flexibility and business continuity to have no English language requirement. However, on the whole we feel these exemptions should only be where strictly necessary, and that as far as possible government should resist the temptation to add additional occupations to existing routes with no English language requirement as a means of circumventing the rule. For routes where there is no English language requirement, we believe that – as the Government has stipulated for the Seasonal Workers pilot – it is important for the worker to receive a contract in their own language and for this requirement to be enforced.

Levels of unionisation are lower among migrants, something that has been observed both in the UK and the United States (US) (Sumption and Fernández-Reino, 2018; Weil, 2010). This may be related to the temporary nature of work programmes, and migrants’ expectations of their labour market rights may be lower because they have previously worked in countries with lower labour market standards than the UK (Sumption and Fernández-Reino, 2018; DLME, 2017).

Some factors make exploitation more likely by increasing dependence on the employer (FRA, 2019), for example, having accommodation provided by the employer and/or living in geographically isolated areas. Both these conditions are particularly common among migrants, for example among those living on farms. In some cases, this accommodation is not fit for purpose despite the employee being charged for it and having little realistic alternative but to take it: FRA (ibid.) cites examples of migrants sleeping in fields and construction sites, with very limited sanitary facilities. A small-scale survey of seasonal workers in Scotland by FLEX and Fife Migrant Rights Forum indicated that 57 of the 58 respondents were dependent on their employer for housing, with respondents also highlighting the poor quality of accommodation for the price paid, and unsafe accommodation. The 2021 review of the seasonal workers pilot indicated similar problems: 15% of respondents to an annual survey of pilot workers said their accommodation was neither safe, comfortable, hygienic nor warm and 10% said their accommodation had no bathroom, no running water, and no kitchen. In some cases migrants may voluntarily enter into such accommodation on the private market, for example sharing with several other people in order to save money. However, where accommodation is provided by employers (and the employee therefore has less choice in the matter) it is important (as we underlined in relation to other workers in our 2021 Review of the Intra-Company Transfers route) that it is fit for purpose, fairly priced, that the migrant has a free choice about whether they live there, and that these conditions are properly enforced.

Areas where migrant workers are uniquely vulnerable to exploitation

There are also forms of exploitation that are unique to migrant workers. Migrant workers may be unaware of the fact that they are being exploited, being forced to work, or trapped in an exploitative situation. Alternatively, for some migrants, collusion with exploitative working practices may be the most rational choice if the exploitative situation still leaves them better off than working in their home country (where it may be hard to find a job or where pay differentials mean that they can earn much more in the UK even if exploited). Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF, 2011) comment that “A wealth of research shows that people all over the world routinely make choices such as this, submitting themselves to precisely these kinds of exploitative labour relationships because doing so represents their best or only available option” and the collected literature provides numerous examples where migrants have made such decisions: in qualitative and quantitative research with migrant workers across the EU FRA (2019) found that more than two thirds of participants mentioned economic need as a driver of exploitation.

Research by University of Nottingham Rights Lab has demonstrated the existence of ‘pre-agreed’ exploitation. This is where the terms and conditions of the job are made clear to the migrant before they leave their home country, but the migrant is not made aware that these terms and conditions are comparatively poor in the UK. In these cases, migrants may not view themselves as exploited given that they had freely entered into the agreement with the agency.

Many migrants borrow money to pay the costs associated with coming to the UK. A small-scale study by Migrant Voice (2022) indicated that two thirds of migrants responding to the survey had gone into debt – to friends, families, banks or commercial lenders – to pay for their visas. A similar-sized study carried out by FLEX and the Fife Migrants’ Forum (2021) indicated that 62% of respondents had gone into debt to come to the UK on a Seasonal Worker visa. If migrants are indebted, this may prevent them leaving exploitative employment, and indeed force them to accept further exploitative conditions such as being obliged to pay inflated accommodation charges.

While it is illegal to charge recruitment fees in the UK (as set out in the GLAA licensing standards), it is legal to do so elsewhere (although doing so is contrary to ILO guidance on fair recruitment). Migrants may therefore end up paying recruitment fees in their home country in order to secure work in the UK. Several recent Parliamentary Questions have raised this issue, which has also been reported on extensively in the press during 2022, most specifically in relation to specific sectoral routes in both the care sector and agriculture. The number of countries – including India, the Philippines, Ghana, Zimbabwe, and Indonesia – cited in such reports indicates that the problem is (at the very least) geographically widespread even if statistical evidence of the extent of the problem is lacking. Migrants may be aware or unaware that these fees are illegal/unfair. There is evidence that these fees are often borrowed at high rates of interest using the family home as collateral, and that workers may not only be heavily indebted but go on to become trapped in debt bondage as a result. This, as well as the time-limited nature of these work schemes and the lack of options for redress where many organisations are involved, means that the situation often goes unaddressed.

The UK Government cannot control the fees charged in other countries. However, we believe it should look more broadly at whether it is possible to prevent those who charge such fees entering into the chain of recruitment organisations through which migrants enter the UK and build on existing work being carried out. For example, the GLAA has previously conducted effective upstream work on social media to inform Romanians who may be looking to move to the UK to work in construction of their rights, and this model may be able to be used with other nationalities in the sectors where recruitment fees are most likely to be charged. Promotional work on the importance of not paying fees that is currently being carried out by scheme providers and other stakeholders with an interest in seasonal workers also shows the importance of sector-based campaigning.

The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) is also conducting similar work in the health and social care sector. The DHSC code of practice for international recruitment sets out standards such as charging by UK agencies being illegal. Further guidance is currently being prepared around this, which, like the GLAA guidance, will be aimed at those who have come, or are interested in coming, to the UK to work. The guidance will be made available online, including on the visa application webpage for the Health and Care Worker (H&CW) visa, and disseminated via the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office in other countries in locations where people who may wish to work in the UK are most likely to see it (such as medical schools). It will include guidance on work standards and the costs of living in the UK and a list of ethical recruiters, as well as information on how to report violations. Stakeholders (government departments, UK-based recruiters and end employers) in other sectors may wish to collaborate on similar strategies to target specific audiences most at risk of exploitation.

How factors relating to the immigration system affect migrant vulnerability to labour market exploitation

There are several ways in which the immigration system itself can also create vulnerabilities. It is not necessary for migrants to be subject to the immigration system to be vulnerable: research with migrants in the care sector also revealed exploitation of European Economic Area nationals who had the right to work in the UK. However, the immigration system may facilitate exploitation through creating conditions where employers have a strong incentive not to comply with the rules, where reporting by employees is disincentivised, or because the rules are not enforced.

Lack of ability to work

Those who are not in the UK on a work route, but who are working in the UK, may also be vulnerable because of specific rules in the immigration system. For example, asylum seekers are not generally allowed to work legally (with some very limited exceptions) so may enter the informal economy on poorer wages and conditions, or students may be pressured to work more than their visa conditions allow under threat of reporting past violations. Finch and Cherti (2011) found this to be a particular issue for those who were living irregularly: in qualitative interviews with 80 migrants from 15 countries they found evidence that “irregular immigrants are frequently treated worse than British and regular migrant workers” including lack of holiday, sick and maternity pay; being paid less than NMW; abuse and threats; and having their papers taken away.

Work Rights Centre (2022) has carried out a survey with 191 Ukrainian refugees in the UK. They highlight in particular the population of Ukrainians who were in the UK at the outbreak of war but who did not have a valid immigration status. These people have been excluded from the 3 visa schemes (Ukraine Family Scheme, Ukraine Sponsorship Scheme and Ukraine Extension Scheme) set up to support Ukrainian nationals, and may therefore be particularly likely to seek work in the informal market and (with limited choices) find themselves in an exploitative situation. The caseworker guidance for the Ukraine schemes provides for some flexibility (explicitly stating that refusal should not be given on low-level immigration offences and allowing additional flexibility in terms of evidence submitted). However, this group is likely still to find it difficult either to regularise their status or to return home.

Restrictions on work for some groups of migrants may push them into exploitative situations by preventing them from obtaining safe and legal sources of income. For example, individuals seeking asylum ordinarily have no right to work other than after their application has been pending for 12 months, and then only in a Shortage Occupation List (SOL) role. The comparative restrictiveness of this rule, and the association between work restrictions and subsequent integration once refugee status is attained, are issues on which the MAC has previously commented. In our 2021 Annual Report we questioned the restriction that allows asylum seekers to work in SOL occupations only, and only after 12 months without a decision. We also recommended that the Government review their policy more generally on allowing asylum seekers to work.

Lack of ability to switch employers

Lack of ability to switch employers can increase vulnerability to exploitation. Where a visa is tied to a single employer and switching is not allowed, migrants in an exploitative situation face a choice between remaining in it or returning to their home country. For this reason, the MAC has made several recommendations in previous reports relating both to the importance of allowing switching, and to the importance of allowing time spent on non-settlement routes to count towards eventual settlement without needing to reset the clock. These include the recommendations made in the MAC’s 2021 Annual Report.

Migrants may also face problems where switching is allowed but the amount of time left on their visa is likely to mean that it is difficult to find a new employer: this can be a particular issue in situations where sponsorship has been cancelled or curtailed because of the timescales involved. Migrants may also be disadvantaged where the employer does not understand the rules.

Exploitation is more likely in a thin labour market, which may be a problem where the migrant is tied to a specific sector/geographical area where access to alternative employment is limited. For this reason, some commentators (e.g. Metcalf, 2018 cited in Sumption and Fernández-Reino, 2018) have suggested that tying workers to a specific job is relatively uncontroversial in high-skilled visa schemes, but potentially more problematic in low-wage work where the risks of underpayment or labour exploitation are higher. Historically, this is one reason that the MAC has generally not been supportive of occupation or sector-specific visas.

There is evidence that there is exploitation happening to workers who are in the UK under the new H&CW visa, onto which care workers and home carers were added following the MAC’s recommendation in our 2021 Annual Report. The GLAA has found evidence of labour abuse of migrants in the sector, and the number of modern slavery referrals has been rising, with the Care Quality Commission having made 14 referrals by July 2022 compared to 7 in 2021 and 3 in 2020. While we support the work DHSC is carrying out in this area (described above), we emphasise that in our report on Adult Social Care and Immigration in 2022 made several other recommendations which (if implemented) would help to improve life for all care workers in the UK and reduce the risk of exploitation.

Fees

Paying significant fees (visa application fees, visa renewal fees, immigration health surcharges) in relation to the immigration system can also be associated with a higher risk of exploitation, and a lack of ability to escape exploitative situations. The debt incurred as a result of these fees may not only force migrants to stay in work even if it is exploitative but can also have an impact on their family in their home country.

As well as the initial cost of visas and migration, the ongoing costs associated with visa renewals may make migrants more vulnerable to exploitation. The length of time it takes for a migrant on a settlement route to obtain this exacerbates the situation, with initial fees and ongoing renewal costs creating conditions that mean migrants are more likely than their UK counterparts to be vulnerable to exploitation. Qualitative and quantitative research carried out with migrants paying visa fees by Migrant Voice (2022) indicated that the financial need caused by these costs was a reason for migrants accepting exploitation at work.

Some employers use the knowledge of these high charges and the fact that migrant workers cannot afford to lose their jobs to keep them in more precarious work, such as giving them little notice of shifts, or to offer lower salaries than their UK counterparts because they know that they cannot afford to spend time out of work. Even where the fees are paid by the employer, the threat of repaying both fees and onboarding costs may also be used as a means of tying the migrant into the job for a certain period of time: this practice is used both in the public and private sector, including in NHS trusts. Even where it is possible to obtain fee waivers, it can be difficult and complex to do so.

We believe that settlement fees are currently too high: ILR costs £2,404 per person, even after substantial visa and other fees have been paid for 5 years. We have previously highlighted the generally high cost of these fees in comparison to other countries. In some cases the cost of fees prevents people from accessing settlement, meaning that they remain liable for ongoing visa and other costs – along with the associated application process and continued conditionality of status – until they can afford to apply for ILR. Reducing the level of fees charged would be a way of redressing the balance between employers and migrants in the labour market to some extent. We therefore suggest that the Government review fees for ILR, with a view to lowering them – this would have to be a multi-departmental solution given the extent of the fiscal impact on the Home Office. At a minimum, settlement fees should be waived for people on low incomes, as they are in many other visa categories. Doing this would reduce the ability of unscrupulous employers to use migrants’ financial situation, or the threat of fee repayment, to tie them into an exploitative situation. Being settled also reduces the risk of exploitation as the individual’s stay is no longer conditional. There is also evidence that facilitating paths to settlement through methods such as lowering ILR fees increases migrant wages and labour market performance in the long run (Pardos-Prado, 2022).

New routes and changes to the immigration system

New routes may come with an increased risk of exploitation, including through the labour market. For example, a survey with 191 Ukrainian refugees in the UK carried out by Work Rights Centre (2022), has indicated that entrants to the UK under the Homes for Ukraine scheme have found themselves vulnerable to exploitation as a result of lack of safeguarding oversight.

The situation in relation to those in the UK irregularly has been discussed above. However, migrants may also become irregular as rules change. When changes to the immigration system are made, those already in the UK, but who do not have ILR or equivalent status, may also find that they become more at risk of exploitation. For example, Sumption and Fernández-Reino (2020) discuss some of the groups of European Union (EU) migrants who were less likely to have applied for the EU Settlement Scheme (EUSS) and whose circumstances may therefore have become irregular as a result. As noted elsewhere, irregularity and associated issues such as compliant environment checks and no recourse to public funds (NRPF) may be factors in increasing individuals’ propensity to work in the informal market, and/or vulnerability to exploitation.

Temporary work schemes

Although temporary work and associated labour market problems are not exclusive to migrants, temporary visa schemes represent a specific set of issues in relation to migrant exploitation. By their nature “temporary visas provide less time for workers to develop language skills, knowledge of rights and networks that can increase their ability to protect themselves from exploitation” (Sumption et al., 2022). Anderson and Ruhs (2010) explore short-term working in the context of the wider trade-offs migrants make in the UK, with migrants who are in the UK only for the short term often being more interested in economic improvement than social integration, given the time-limited nature of their stay. Similar risks in relation to temporary work programmes exist in other countries such as Australia, the US, New Zealand, Sweden, and Finland (Sumption and Fernández-Reino, 2018). In general “low-skilled worker programmes around the world tend to offer fewer rights to workers than programmes targeted at high-skilled workers” (Ruhs 2013, cited in Sumption 2018).

Although temporary work is common for migrants, a number of the risk factors for exploitation are more common on temporary work routes which tie the migrant to an employer (often obtained through an agency/intermediary). As discussed earlier, this may be particularly problematic in low-waged work at RQF 1 and 2, as risk of underpayment and labour exploitation is higher due to their dependency on their employer. Research with migrants on these routes in the UK has demonstrated some evidence of this on both the Seasonal Worker visa and the Overseas Domestic Worker routes, on both of which the employer often also acts as the accommodation provider.

It can also be hard for migrants to access accurate information about their job in the UK before they leave their home country. Information available to the migrant on their eventual destination, contract/hours, and any fees they will be charged may be generic and insufficient to allow them to make an informed choice about participating. Disinformation on social media is also common. These work schemes also reduce the likelihood of some of the protective factors against migrant exploitation, such as developing their English language skills, knowledge of their rights or networks (Sumption et al., 2022; MAC, 2018), although there are efforts being made by various stakeholders to mitigate this (discussed above).

Looking at the Seasonal Worker visa in particular (a temporary visa allowing migrants to work in the UK in horticultural jobs such as fruit picking), seasonal workers in the UK in this sector (albeit under Freedom of Movement (FoM)) have described the long hours, hard work, and isolation, but also the positives that come with being in the UK on this route – the main positive being the amount of money they earn and save in the UK compared to their home countries.

Specific difficulties related to the Seasonal Worker visa include: fees being charged by recruitment agencies in migrant source countries; how isolated the locations can be; and the large migrant workforce due to the reliance on migrants to fill these roles. There is evidence of migrants not being provided a contract in their native language and of ill treatment (IASC, 2022); the 2021 review of the Seasonal Workers pilot (based on fieldwork carried out in 2019) also reported that almost half the compliance visits had found evidence of this happening. Farms have been found to be targeted by gangmasters who offer a supply of labour at cheap rates (HO, 2017). There is also evidence that farms may demand an unrealistic pace of work from their workers, who are then not allowed to work further if they cannot sustain it (FLEX and Fife Migrants’ Forum research with seasonal workers, 2021). It can also be difficult to carry out due diligence checks in countries of origin within the timeframes allowed by the scheme.

The 2021 review of the Seasonal Workers pilot found evidence of many of the problems cited above, with 22% of workers reporting unfair treatment from farm managers in interviews with the GLAA. Respondents also reported racism, discrimination, or mistreatment by managers allegedly on grounds of workers’ nationality. Previous studies have suggested that temporary schemes in theory offer opportunities to oversee conditions that less regulated schemes do not: “pay and conditions will not be worse for all sponsored migrant workers because employer-sponsored work permit schemes are also more regulated, e.g. minimum salaries higher than the minimum wage” (Sumption and Fernández-Reino, 2018).

Work is being done to protect seasonal workers’ rights, for example the Workers’ Rights leaflets being produced in several languages by the GLAA. Nevertheless, given the risk of labour market violations and the difficulty in enforcement in this sector, there are significant grounds for concern about lifting the cap for seasonal workers. We would like to see far more safeguarding of the workers who come to the UK for low-wage work, through increased compliance and enforcement visits. Given the limited resourcing available, we believe employers using this scheme should contribute significantly towards the costs of compliance, and that these costs should not be passed on to the worker.

Another way in which workers could be safeguarded more efficiently is by minimising barriers to the return of workers who have come to the UK on seasonal visas and who wish to repeat the experience. Returning workers are viewed positively by scheme operators, who have more time to carry out checks and who can be more confident that placements will work out with a worker who is a known quantity, and by retailers who welcome the added assurance and reduced risks of exploitation in recruitment. Growers also tend to prefer workers with experience of their sites’ specific ways of working, particularly in more specialist growing.

Over the last 2 years scheme quotas have been announced with little notice, leaving scheme operators less time to recruit and potentially delaying seasonal workers’ arrival into the UK. As the Seasonal Worker visa is for 6 months with a 6-month cooling-off period, it can then be difficult to bring workers back to the same place at the same time the following year. The Home Office may wish to look at whether any flexibility is possible, potentially by shortening the cooling-off period. Reducing barriers to enable those who wish to return to do so would also allow migrants the time to become more informed about their rights in the UK and increase their opportunities to learn English. Developing this pool of informed workers would also facilitate the spread of information in source countries about what seasonal workers should expect from a work placement in the UK.

Welfare exclusions and lack of access to Legal Aid and other forms of redress

As discussed above, financial need is a key driver for migrants entering or staying in exploitative work. Rules around NRPF and lack of access to benefits mean that migrants may find it more difficult to support themselves while changing employers, thereby discouraging them from looking for alternative work. Exploitative work may then be their only option to meet basic needs (JRF, 2011). Avoiding destitution (including rough sleeping, which in itself may lead to a migrant being deported) is also a reason for people becoming re-exploited having left exploitative employment.

Migrants are not eligible for some types of Legal Aid support. This support is often also difficult to access even if they do qualify, owing to the general reduction in availability of Legal Aid over the years. Other forms of redress may also be difficult to access. For example, most migrant partners of people on temporary routes cannot access specific leave for domestic violence victims (a restriction which disproportionately affects women). The National Referral Mechanism, by which victims of trafficking/modern slavery can regularise their status, also has long delays which mean that it is hard for migrants to use this route out of exploitation. Whatever the criteria to access leave to remain through this route, it should at least be sufficiently resourced to be usable.

Compliant environment policies

Compliant environment policies (including right to work checks, immigration enforcement raids, the criminal offence of illegal working) may also create a real or imagined fear of deportation/immigration enforcement action which employers can use as a tool to control or threaten migrant workers and trap them in exploitative working conditions (FLEX, 2022). FRA (2019) also provide evidence that migrants may endure exploitation rather than being reported to the authorities whereas Anderson and Ruhs (2010) explore migrants’ fears of being seen as ‘illegal’ or semi-compliant. In practice, it is also possible for labour market inspection bodies in the UK to share information with Immigration Enforcement. One partial solution to this may be the ability to report exploitation without personal data being shared in this way, a system used in the US. The Home Office and the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy may wish to consider working together to establish the feasibility of this, with a view to putting a similar agreement in place.

Lack of enforcement

Labour market enforcement is not well resourced: in 2014 the MAC expressed concern that enforcement of labour standards generally had been too limited, regardless of the origins of the workers. According to the DLME, the likelihood of being inspected is low enough to have only a weak deterrent effect (2018): “I have concerns that both the chances of being investigated by enforcement officers and the scale of financial penalties for those found to be non-compliant are too low.” In the UK Labour Market Enforcement strategy 2018/19, analysis of the number of closed cases showed that in 2016/17 the average UK employer could expect an inspection from HM Revenue & Customs minimum wage enforcement function around once every 500 years, and the average employment agency could expect an inspection from the Employment Agency Standards Inspectorate once every 20 years. Lack of enforcement, limited penalties and the potential profits to be gained by flouting the rules may also lead employers to make calculations and choose to carry out an “efficient breach” of labour law if the financial benefit to be gained is more than the likely cost of breaking the law. The DLME has warned that “employers are actively discounting these costs as part of their business model”.

We recognise that both immigration and labour market enforcement are finite resources that must be focused where there is the greatest risk of harm. To this extent, work migration (albeit this has historically largely been on highly-skilled routes) has not received a great deal of attention relative to other migration routes, although several threats under active Home Office investigation relate to the exploitation of migrants who are either in the UK for work or who are working while in the UK for other reasons. We would suggest that the Home Office looks at ways in which increased enforcement could be funded through fees paid by employers (whether existing or additional), with the proviso that these fees must not be passed on to migrants themselves as this would serve only to increase the prospects of exploitation.

MAC future work on exploitation

We expect that our work around exploitation in future commissions may involve:

Identification of trade-offs and recommendations for ways forward: a secondary effect of any recommendations that increase migrant restrictions (even if this is to reduce exploitation in the UK) may be to increase migrants’ vulnerability to exploitation in their home country, as a consequence of reducing their ability to move. We have a duty to weigh up the consequences of the recommendations we make. In some cases, this will mean identifying where there are trade-offs and the best way of balancing these.

-

Examples of the kinds of trade-offs (identified by the Migration Observatory, 2018) could include:

-

Linking a migrant’s presence in the UK to their employer: on the whole this reduces exploitation by making it easier to monitor compliance and target enforcement, but it also potentially makes it more difficult for migrants to leave their job (which may increase employers’ hold over their employees and hence the potential for exploitation);

-

Heavier regulation (which would reduce exploitation) depending on effective enforcement to be successful;

-

Efforts to direct employees to one part of the labour market through the use of sector-specific schemes increasing the potential for exploitation as a consequence by reducing those migrants’ opportunities to switch;

-

Some measures potentially preventing groups of migrants from moving to the UK at all: for example setting rules around language skills will reduce the potential for exploitation among those who enter the UK but may leave the group that cannot enter the UK vulnerable to exploitation by removing the chance to move.

We will consider similar trade-offs and attempt to strike a balance between ensuring the labour market is flexible enough to respond to the UK’s needs, while ensuring those who come to work here are properly protected.

-

Commenting on the potential for exploitation: shortage can give employees more bargaining power. However, for those who already have increased restrictions in terms of legality or coercion, shortage has the potential to fuel exploitative and/or illegal working practices where exploitative agents attempt to fill the gap in the market (for example because employers are less likely to insist on the same checks):

-

In particular, we will look at the potential for exploitation (including the abuse of zero-hours contracts) as part of our considerations around whether jobs should be added to the SOL, particularly at RQF 1 - 2;

-

We will also look at the potential for exploitation to vary or be experienced differently by gender and protected characteristics.

-

Commenting on good practice elsewhere, whether that is good practice in other countries or good practice suggested by other organisations. We can also share findings with other organisations who are better placed in the area, for example sharing findings with the DLME on specific sectors/industries they or we identify as those in which migrants are particularly likely to experience exploitation (e.g., nail bars and car washes) or in which changes to the immigration system, e.g., the ending of FoM, may increase the risks of exploitation;

-

Produce recommendations on areas requiring more enforcement, acknowledging the wider enforcement context, in particular the low levels of resourcing overall and the high degree of self-monitoring expected of work sponsors.

2: Labour Market and Immigration

The labour market this year has been characterised by highs and lows. The recovery from the pandemic has been tempered by stalling progress on employment and rising inactivity, an unprecedented level of vacancies, and soaring inflation, with the Consumer Prices Index rising by 11.1% in the 12 months to October 2022.

The after-effects of the first 3 waves of the pandemic, the Russian invasion of Ukraine and, uniquely to the UK, exit from the European Union (EU), have all played a role in influencing this climate. Against this backdrop, the Skilled Worker (SW) route continues to bed in, and it remains to be seen what the long run trend in volumes will be. This chapter focuses on the end of Freedom of Movement (FoM) in this climate, looking at both the labour market and the use of the SW route.

Overview of the labour market

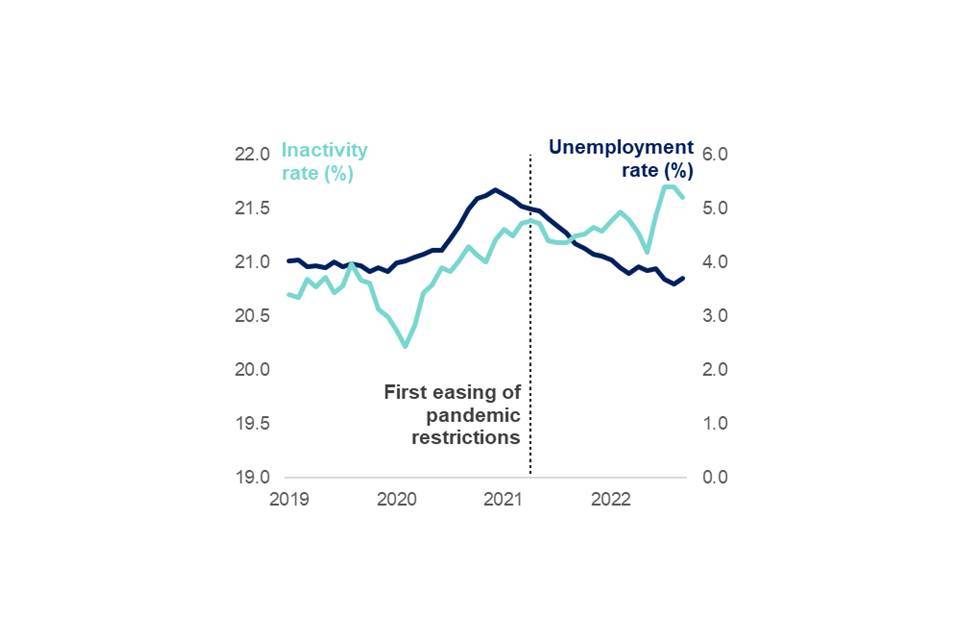

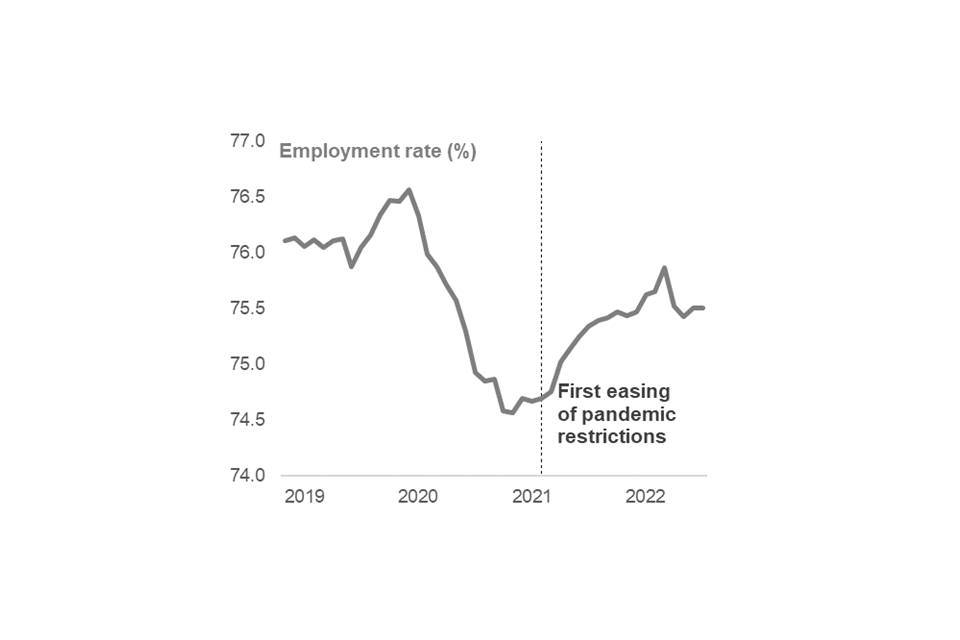

Since the first easing of pandemic restrictions in March 2021 there has been a substantial fall in unemployment, which has now dropped to below pre-pandemic levels, as shown in Figure 2.1, and to rates not seen since 1974. By contrast, employment, in Figure 2.2, has been more sluggish, recovering quickly in 2021 but stalling in 2022 and not yet back to pre-pandemic levels. This shortfall in total employment is driven by falls in total self-employed workers, which was, as of September, 733,000 lower than before the pandemic. The fall in self-employed workers has been offset in part by an increase in the number of employees of 464,000 over the same period. Economic inactivity has increased on pre-pandemic levels to above 21% of the population aged 16-64.

Figure 2.1: Economic inactivity and unemployment rates (%) aged 16-64, 2019-2022

Source: ONS Labour Market statistics, November 2022.

Note: Seasonally adjusted data, includes all aged 16-64.

Figure 2.2: Employment rate (%) aged 16-64, 2019-2022

Source: ONS Labour Market statistics, November 2022.

Note: Seasonally adjusted data, includes all aged 16-64.

These labour market conditions are not unique to the UK, with the temporary rise in unemployment replicated across Europe and the initial uptick in inactivity also seen in most G7 economies. Where the UK stands out is that economic inactivity remains stubbornly above pre-pandemic levels. While the UK’s absolute rate of inactivity is not as high as others in the G7 (most notably France and Italy), Figure 2.3 shows that since the end of 2019 most G7 countries have experienced a fall in their inactivity rate. This trend is evident in more than three quarters of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, whereas the UK has seen the inactivity rate increase. The reason that inactivity is higher in the UK compared to other countries is unclear. What is clear is that the UK’s increases in inactivity are the greatest in comparison to the G7 for men aged 15-24, but also notable for the 55-64 age group as whole.

Figure 2.3: Percentage point change in the economic inactivity rate across the G7, ages 15-64, 2019-2022

Source: OECD Q4 2019-Q2 2022.

There are several elements that make up the UK’s inactivity picture. From 2019 onwards there have been consistently large flows from employment and particularly self-employment into inactivity, with the percentage of self-employed entering inactivity peaking at more than 3% in Q2 2020 and a peak of more than 2% of employees entering inactivity in Q4 of 2020 and 2021.

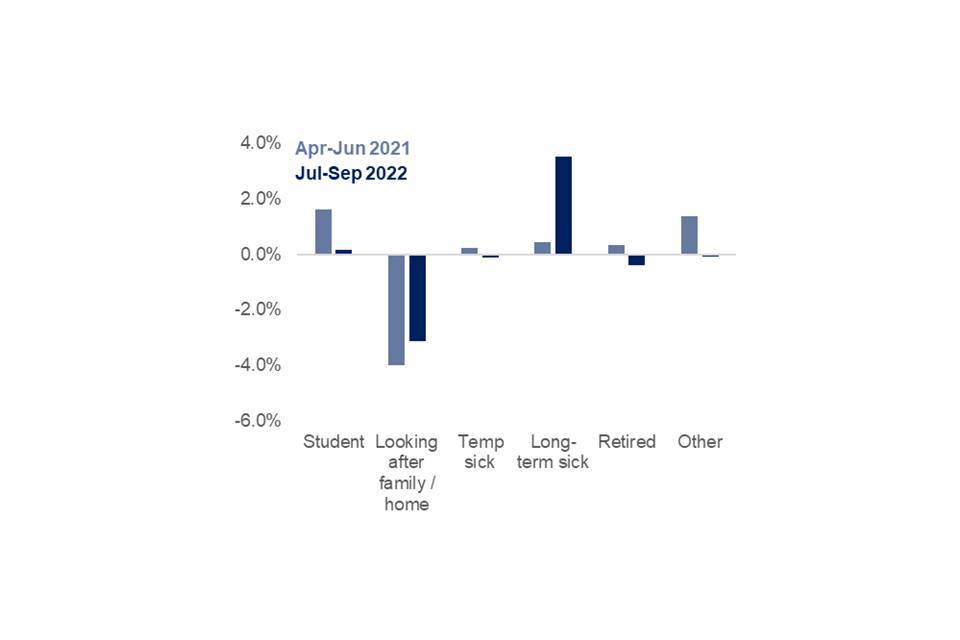

By age group, the drivers of inactivity have changed over time. Figures 2.4 and 2.5 break down these changes both in terms of age-group and self-reported reason for inactivity. The inactivity rate rose most for the 16–24 age group in 2021, as they entered or remained in full-time education given limited labour market opportunities at the height of the pandemic. This has begun to unwind in 2022, though around 100,000 more 16-24 year olds are inactive compared to 2019. Among 50-64 year-olds, the inactivity rate increased by a smaller amount in 2021, but has continued to increase in 2022, now sitting more than 2 percentage points above pre-pandemic rates. In terms of levels, 50-64 year-olds have been the largest driver of increased inactivity in the working age population both in 2021 and 2022, with nearly 300,000 more individuals inactive compared to 2019.

Figure 2.4: Percentage point change in inactivity rate by age group compared to 2019

Source: ONS Labour Market statistics, November 2022.

Note: Seasonally adjusted data, includes all aged 16-64.

Figure 2.5: Percentage point change in inactivity rate by reason compared to 2019

Source: ONS Labour Market statistics, November 2022.

Note: Seasonally adjusted data, includes all aged 16-64.

Sustained high inactivity is therefore predominantly being driven by the 50–64-year-old age group. Whether individuals in this group are likely to re-enter the labour market is unclear. The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) has suggested that greater inactivity is largely due to changes in lifestyle, which the Office for National Statistics (ONS) Over 50s Lifestyle Study corroborates. The Study also finds that a higher proportion of those surveyed would consider returning to work, particularly if they are offered flexible working hours, good pay, and the ability to work from home some or all the time.

Alongside the increase in students, inactivity due to long-term illness has risen considerably, particularly in 2022. While this has coincided with the pandemic, IFS research on labour market flows suggests that rates of long-term illness have increased among the stock of those already inactive, rather than directly forcing individuals out of the labour market. It remains unclear to what extent this reflects the rising NHS waiting lists or ‘long COVID’ and to what extent the long-term sick were formerly those with caring responsibilities (down by around 160,000 since the end of 2019). Significantly, Office for Budget Responsibility research notes that the rise in inactivity due to long-term sickness has been echoed by a rise in new claims for disability benefit, suggesting that many inactive people may not return to the labour market.

While the supply of labour has stalled amid low unemployment and high inactivity, demand for labour has been unprecedented as the economy recovers from the pandemic. Vacancies have increased to record highs in the UK: an estimated 1.3 million between March and May with the ratio of unemployed people per vacancy falling to below 1 from June to August 2022 for the first time on record. These numbers may now have peaked and sit at 1.23 million as of October 2022. This pattern of increasing vacancies is consistent with other developed nations, as shown in Figure 2.6, suggesting that whilst ending FoM may have contributed to higher vacancies, or at least slower turnover, it is not the sole cause. Pent-up demand from pandemic restrictions is likely to be a significant driver of some of this common trend across several countries.

Figure 2.6: Index of total vacancies among selected G7 countries, (Index=100, Q4 2019), 2019-2022

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, ONS, Statistics Canada, Institut für Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung, OECD.

Notes: 1) These data are not strictly comparable due to differences in measurement. 2) No data for Canada from Q2-Q3 2020. 3) UK statistics exclude agriculture.

The ending of Freedom of Movement

The end of FoM and the introduction of the SW route has introduced a more demanding process for European Economic Area (EEA) workers to come to the UK, requiring a job offer from a licensed sponsor before arrival and preventing recruitment directly into Regulated Qualifications Framework (RQF) 1-2 occupations (except care workers). At the same time, there has also been a relative relaxation in restrictions for non-EEA workers.

The EU Settlement Scheme (EUSS) has allowed the vast majority of EU workers already in the UK to remain without needing to meet visa requirements, theoretically allowing sectors to retain their stock of workers and add to their workforce as necessary through the SW route. However, this pool of workers will diminish over the long term and the introduction of the SW route may make filling vacancies more difficult – especially for sectors dependent on EEA workers at skill levels below RQF 3, who are now ineligible for sponsorship.

This therefore represents a shock to labour supply, particularly restricting access to workers with lower training and qualifications. Based on the framework set out in Dustmann and Glitz (2015), we may observe 3 trends amongst employers following this shock:

-

Employers may try to attract new workers by raising wages and improving conditions. This will aim to substitute EEA labour for those already in the UK, particularly UK born workers. There may be high barriers to doing so, in that these sectors may not have been traditionally attractive to domestic workers and employers may face more intense competition with each other over a relatively fixed pool of labour.

-

Employers may reduce the labour-intensiveness of work. This could be achieved through automation, raising the productivity of workers through education and training or, in some cases, relocating activity.

-

If employers can do neither of these things, they may ultimately produce less. If this is the case across a sector, that sector will decline in its share of the labour market.

Immigration, skill mix and capital skill complementarity (Lewis, 2011)

In the 1980s and 1990s, certain metropolitan areas in the United States experienced a wave of immigration due to the tendency of immigrants to regionally cluster. This constituted a shock to the labour supply, increasing the relative supply of less skilled labour.

Combining census, technology, and labour force data, Lewis (2011) examines the relationship between the relative supply of less skilled labour in a metro area (induced by migration) and a manufacturing plant’s use of automation machinery. This is a ‘natural experiment’ because it relates the change in labour supply due to immigration, something largely outside firms’ control, to their decision to automate.

He finds that firms in areas with high immigration flows adopted significantly less machinery per unit of output, despite having similar adoption plans initially, and his overall results are consistent with automation machinery being both a relative substitute for less skilled labour and a complement to higher skilled labour.

In the UK context, FoM can be interpreted as a similar shock to the labour supply, in that it increased the pool of labour available to employers, particularly in RQF 1-2 occupations. This may have historically dampened incentives to adopt machinery. The end of FoM is therefore a shock in the opposite direction, which could encourage firms to turn to automation to substitute for less skilled labour – though this is by no means guaranteed.

This picture has been complicated and exacerbated by the pandemic, during which many sectors lost large numbers of foreign workers (as they returned home), leading to shortfalls when restrictions were then eased, and demand recovered. In addition, the rise in inactivity already discussed has reduced potential labour supply. This has, to some extent, brought forward the labour shock in some sectors which may have developed more slowly otherwise.

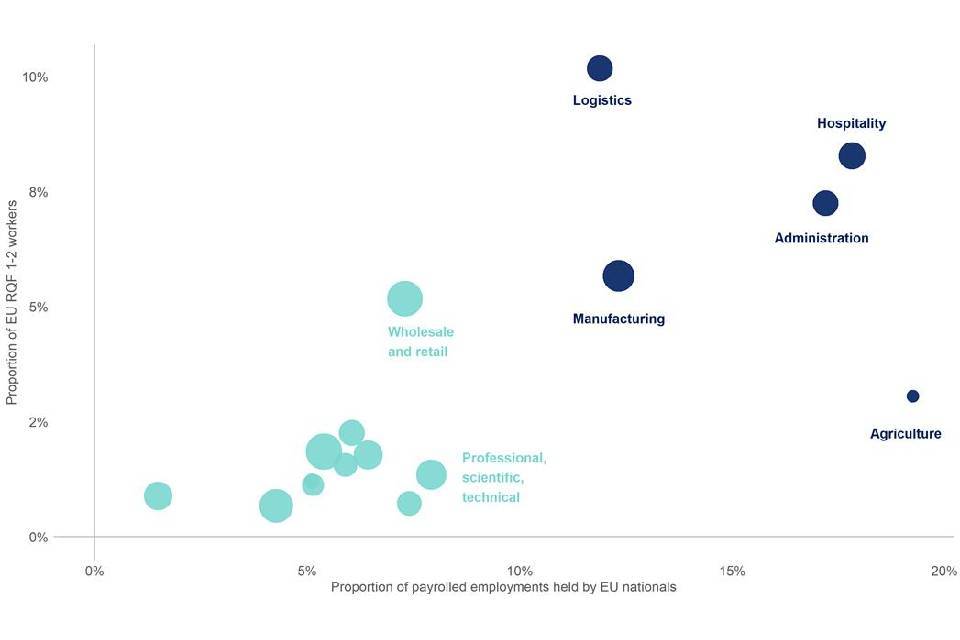

Figure 2.7 shows which sectors were most dependent on EU workers prior to the ending of FoM, both in their entirety and in terms of those working in RQF 1-2 occupations now ineligible for a SW visa. The manufacturing, logistics, administration (in particular cleaners, gardeners, security guards) and hospitality sectors stand out as the most reliant by both of these measures. We also focus on the agriculture sector, given that the Annual Population Survey (APS) (providing data on the proportion of EU RQF 1-2 workers) is likely to underestimate the sector’s dependence on hard-to-sample seasonal EU workers. These 5 sectors are likely to face the greatest shock as a result of the end of FoM.

Figure 2.7: Dependence on EU workers by sector

Source: APS 2019, HMRC PAYE RTI 2019.

Notes: 1) Dark blue dots refer to sectors identified as most likely to be impacted by the end of FoM. Turquoise dots show the sectors in the rest of the economy. 2) The APS (providing data on the proportion of EU RQF 1-2 workers, vertical axis) is likely to underestimate the sector’s dependence on hard-to-sample seasonal EU workers. 3) Under SIC 2007, ‘administration’ corresponds to ‘administrative and support service activities’, ‘agriculture’ corresponds to ‘agriculture, forestry and fishing’, ‘hospitality’ corresponds to ‘accommodation and food service activities’ and ‘logistics’ corresponds to ‘transportation and storage’.

Over the medium to long term, employers in these sectors in particular are likely to face the challenges outlined above: raise wages, improve the attractiveness of work or reduce the labour-intensiveness of work. If consumers are highly sensitive to price or if capital costs remain high relative to labour costs, it may be the case that neither of these options are palatable and sectors face relative decline.

This is not to say that all employers are equally exposed to these challenges, or equally able or unable to adapt. For example, an employer’s location will influence its reliance on EEA labour via the demography of a region, while an employer’s size will affect the degree to which it can make capital investments required to automate tasks. But at a sector level, it is likely that employment as a share of the workforce will decrease. FoM provided a relatively cheap supply of labour that may have incentivised recruitment over labour-saving capital investment or other restructuring activity towards fewer, higher productivity and higher paying jobs. Without FoM, many of these jobs may not have existed and may cease to exist in the future – and the period of adjustment to new labour market conditions may be difficult. This is not necessarily a negative development, and there is no obvious reason most private sector industries need to be a particular size.

As well as analysis of quantitative data, we have explored the impact of the labour market shock, and the ability of employers to transition to a ‘high wage, high skill’ economy, by speaking to employers in sectors that historically employed high proportions of EEA workers. To date this has included 7 site visits with companies across the manufacturing, logistics, hospitality, and agricultural sectors.

This work was carried out collaboratively between our independent research contractor, Revealing Reality, and the MAC secretariat. Evidence from this work is incorporated throughout this chapter, and the full report will be published separately by the MAC shortly.

Employment

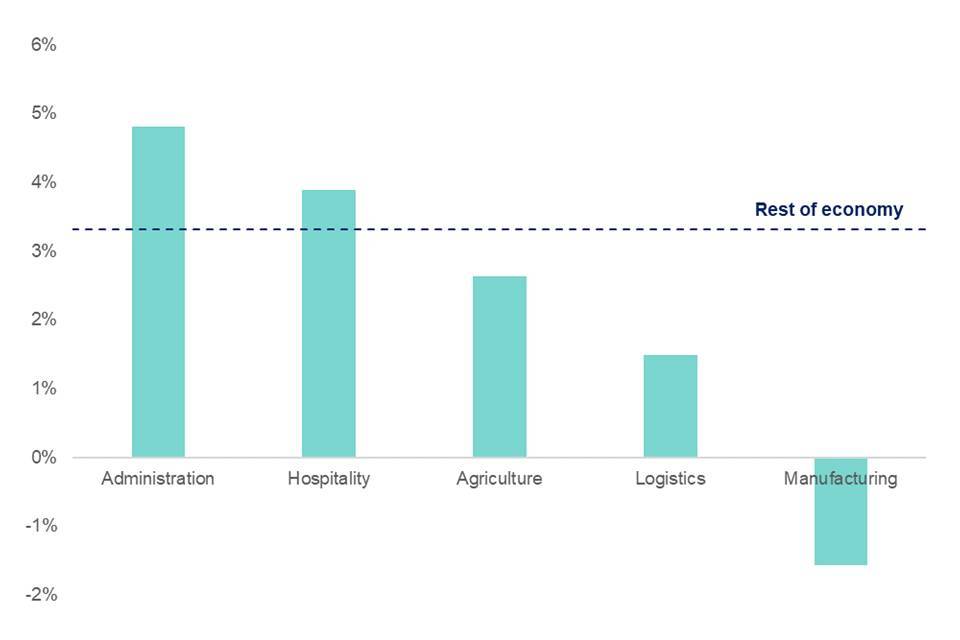

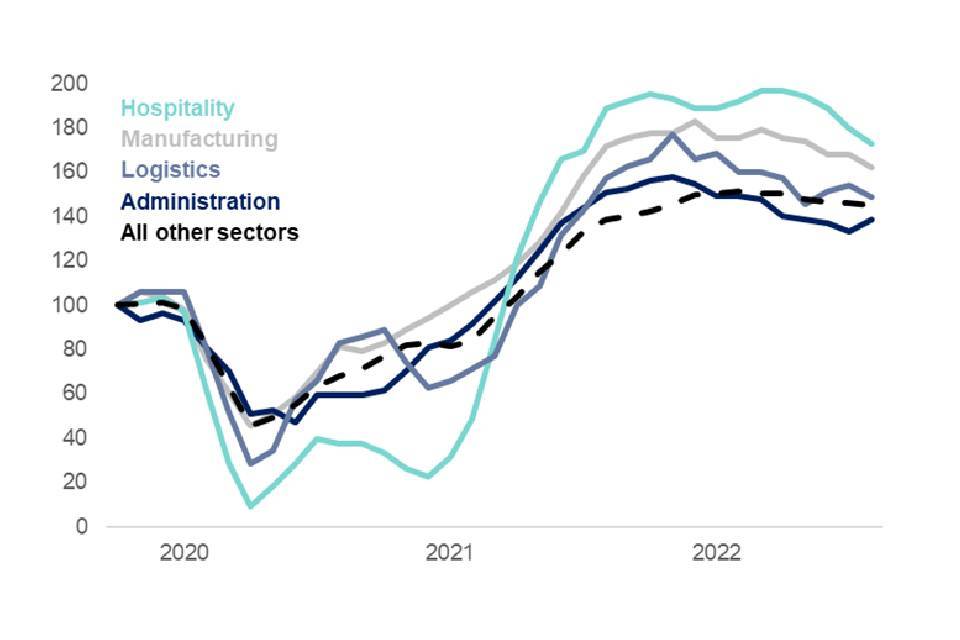

Figure 2.7 showed that there was significant variation in sectors’ reliance on EU labour prior to the end of FoM, with hospitality, logistics, administration, manufacturing, and agriculture the most dependent and therefore most likely to struggle as a result of any difficulties in recruiting EU workers. Figure 2.8 shows how the level of employees in these sectors has changed since the end of 2019.

Figure 2.8: Percentage change in payrolled employees in selected sectors, 2019-2022

Source: HMRC PAYE RTI October 2019 and October 2022 monthly estimates of payrolled employees.

Note: Under SIC 2007, ‘administration’ corresponds to ‘administrative and support service activities’, ‘agriculture’ corresponds to ‘agriculture, forestry and fishing’, ‘hospitality’ corresponds to ‘accommodation and food service activities’ and ‘logistics’ corresponds to ‘transportation and storage’.

This extends previous analysis by the ONS on payrolled employments held by UK, EU and non-EU nationals from June 2019 to June 2021. While data broken down by nationality are not available beyond this point, the ONS analysis showed that, as of June 2021, there had been significant outflows of EU workers from hospitality, administration and agriculture, while manufacturing and logistics were comparatively less affected.

Figure 2.8 (which tracks employees, rather than payrolled employments as in the ONS analysis) shows that the picture has been mixed since then. Comparing the latest data to 2019, employment growth in administration and hospitality has outpaced the rest of the economy since, suggesting that the shortfall in EU labour has been recovered. Employment growth in agriculture sits close to the overall trend, while the share of all employees in logistics has fallen since 2019 – and paid employments in manufacturing have fallen in absolute terms over the same period. Changes in demand for the goods and services produced by these sectors have influenced this picture, as has the sectors’ capacity to source labour. We do not have the data to attribute these changes to the UK, non-EU, or EU workforce since June 2021.

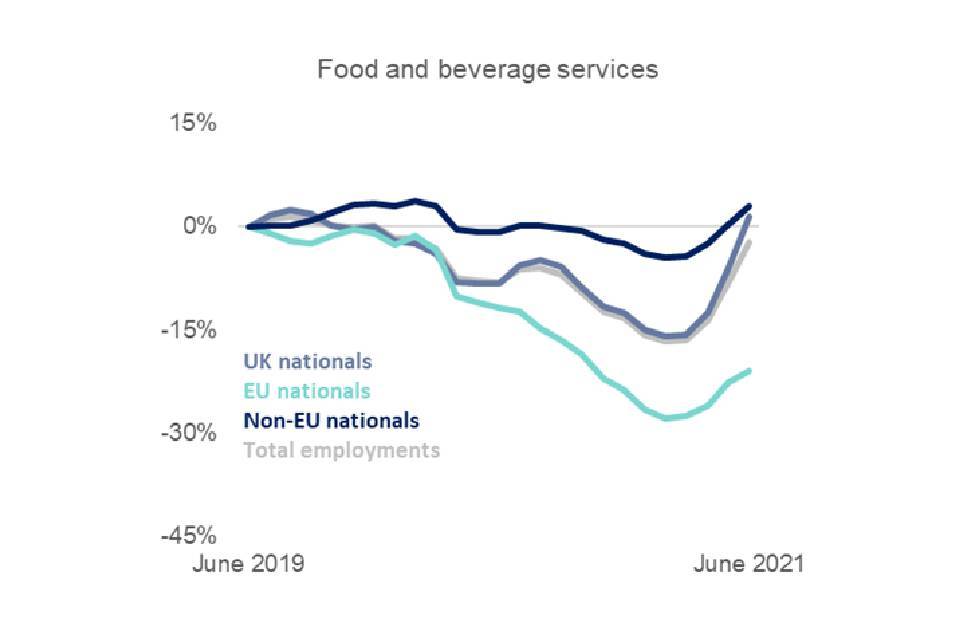

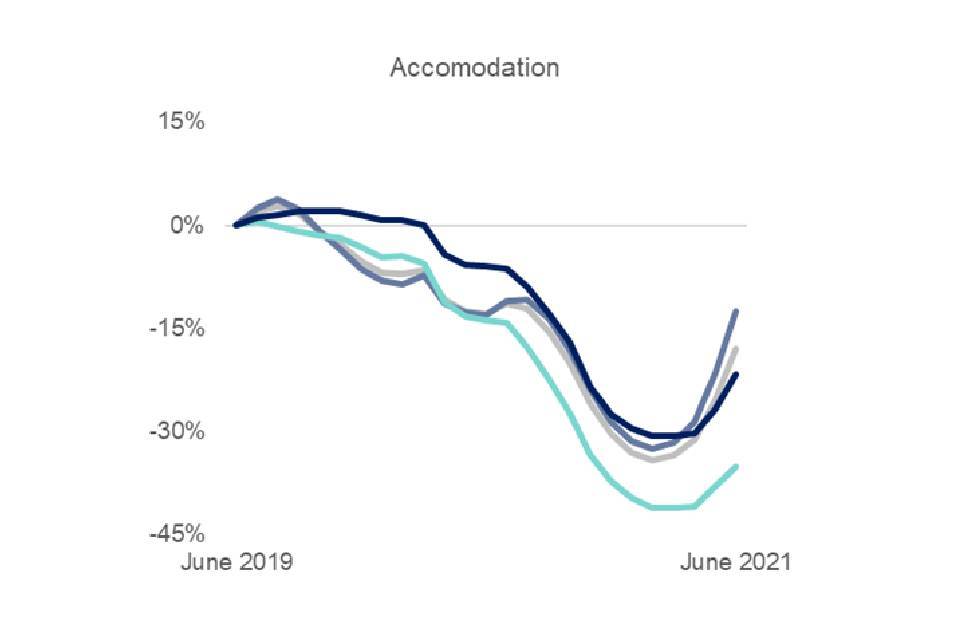

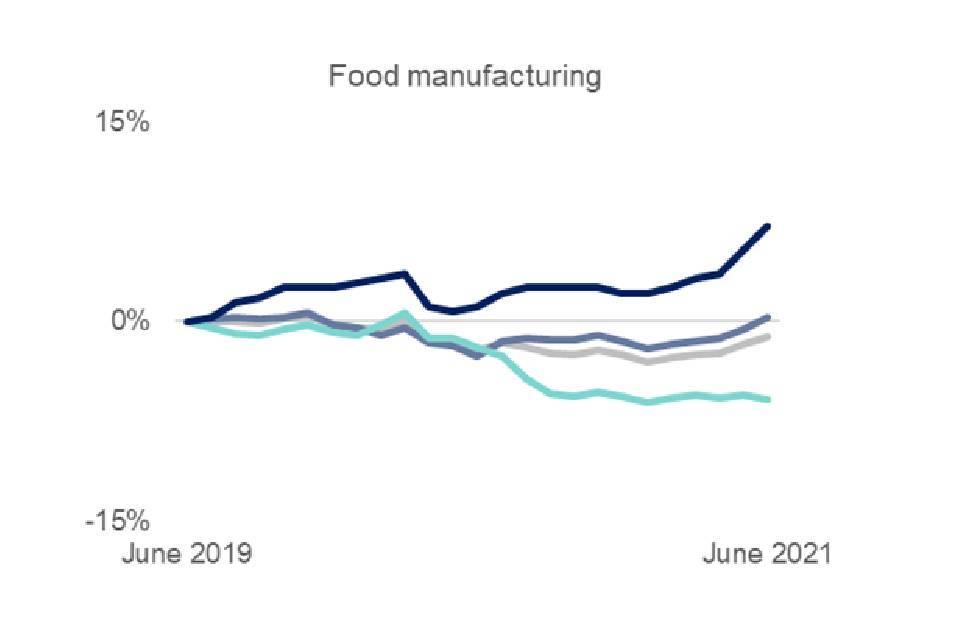

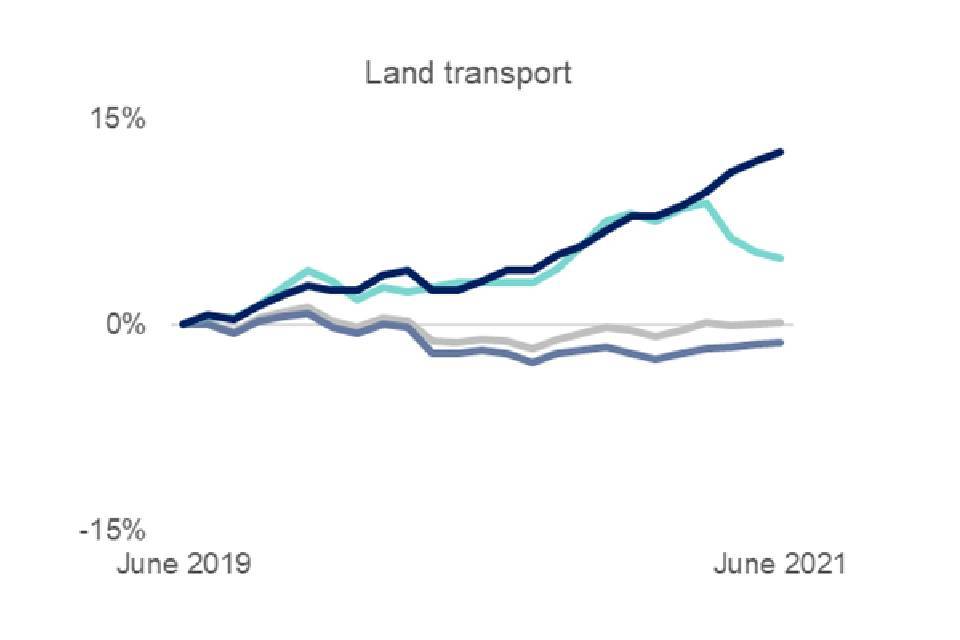

These sectors are large, and aggregate numbers likely mask variation within them. There is also limited evidence on the experience of specific industries or how the employment of different nationalities within them has changed. Figure 2.9 tracks the percentage change in payrolled employments by nationality as compared to June 2019 in selected industries which were among the most reliant on EEA labour under FoM. As the data only go to June 2021, this can only show the position in which these industries found themselves around the time pandemic restrictions were eased.

Food and beverage services and accommodation – the two industries that comprise hospitality and among the most directly affected by the pandemic – saw the most significant falls in EU workers, with little sign of UK or non-EU workers making up for this as of June 2021. In food manufacturing – the manufacturing industry most reliant on EU labour – there is some evidence of non-EU workers partially making up for a fall in EU workers. In land transport there was little to no fall in total payrolled employments from June 2019 to June 2021, with growth among both EU and non-EU nationals.

Figure 2.9: Relative change in payrolled employments held by UK, EU and non-EU nationals, June 2019-2021, selected industries

Source: Bespoke analysis using HMRC PAYE RTI 2019-2021, 2 digit SIC level.

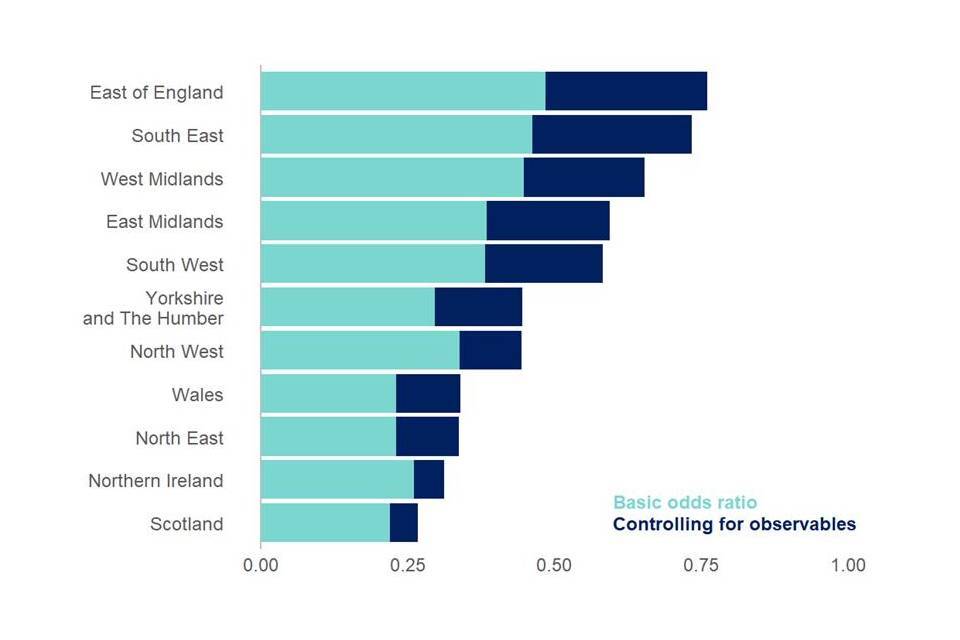

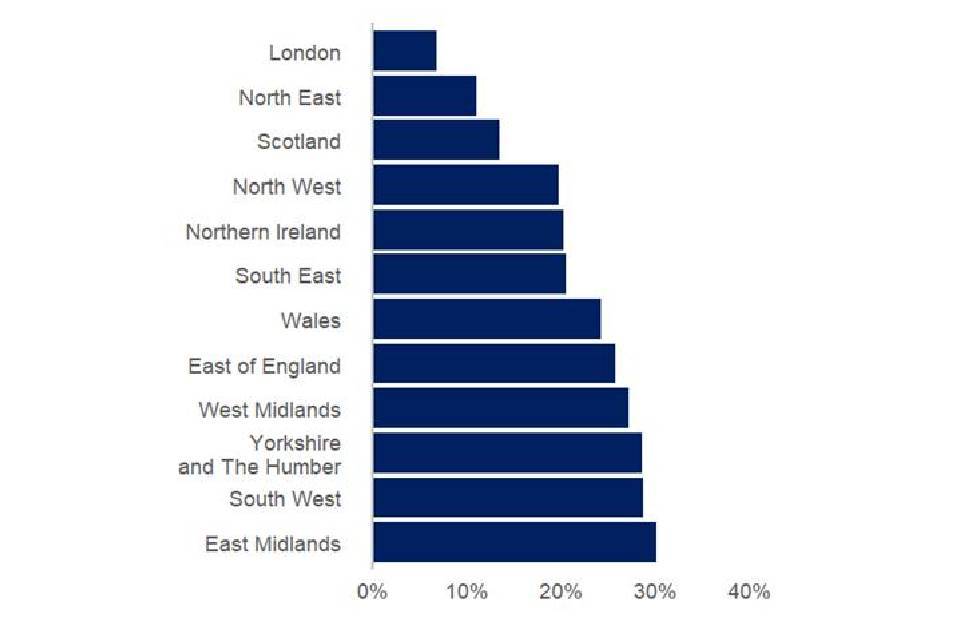

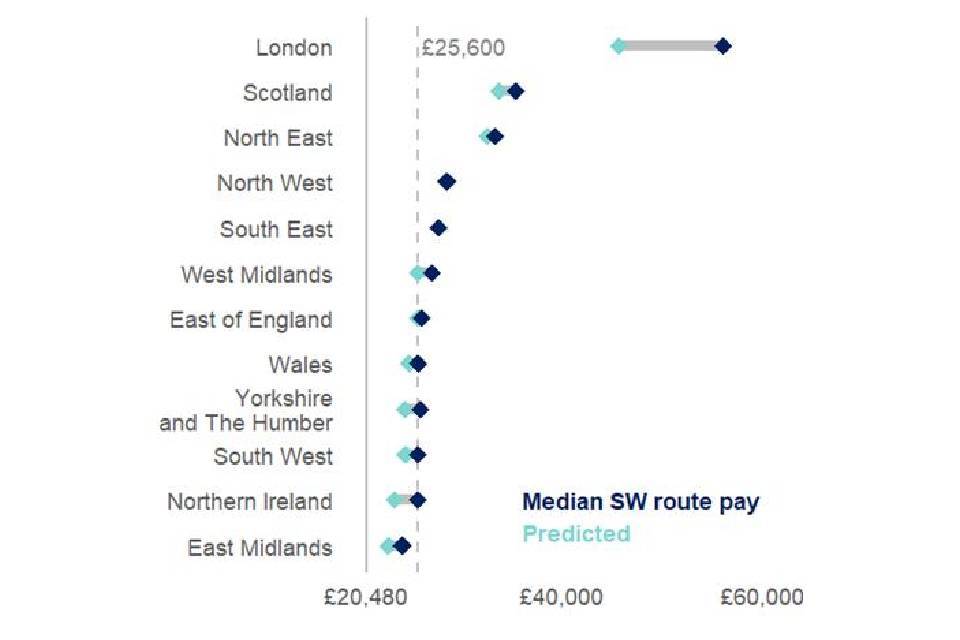

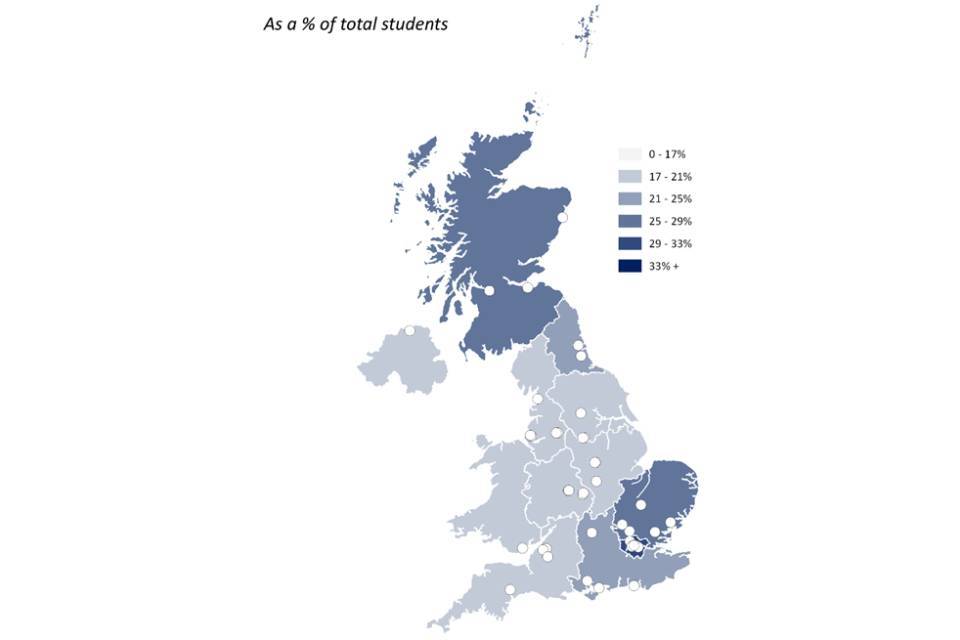

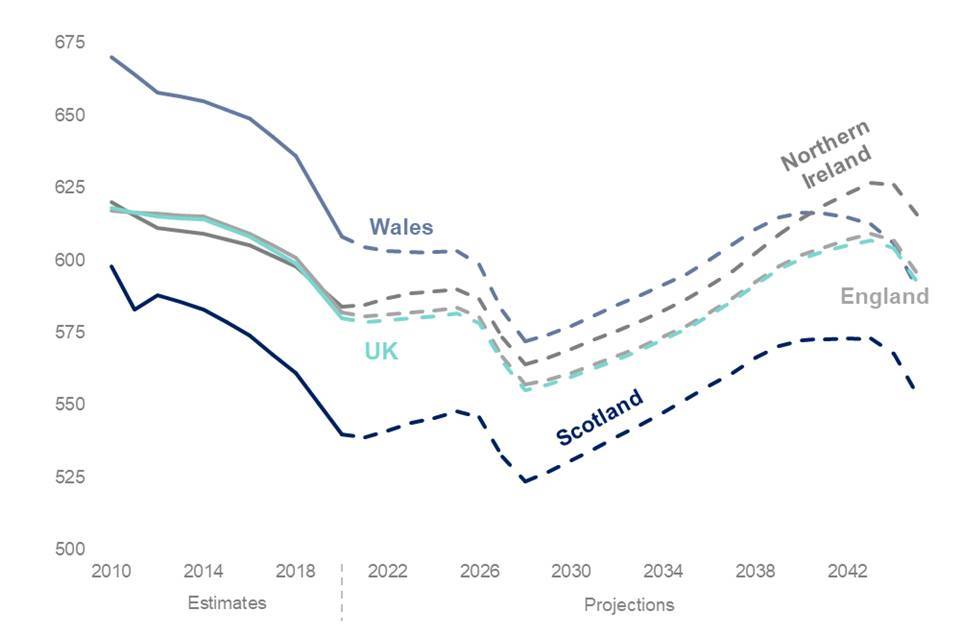

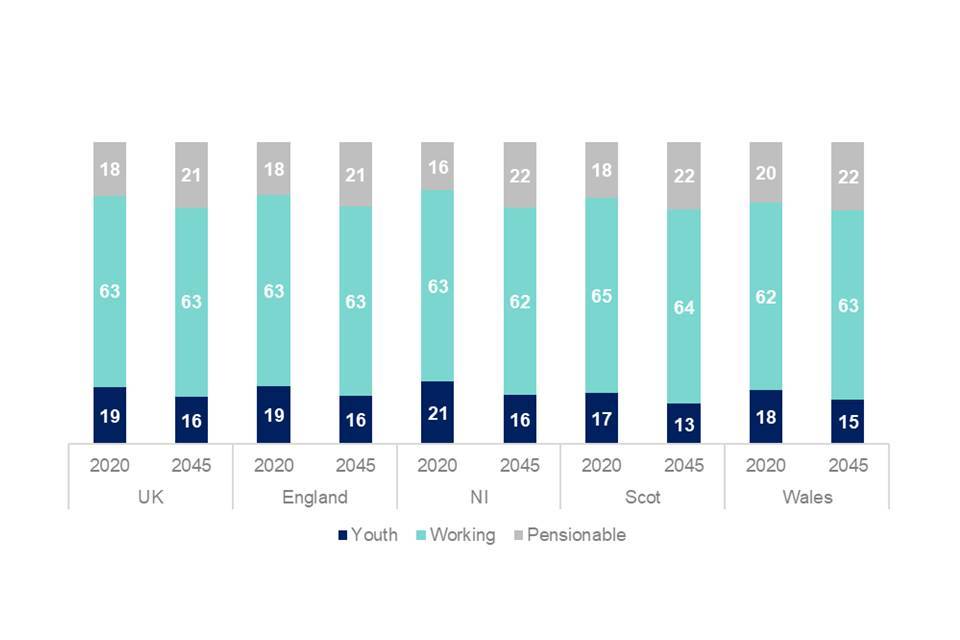

Due to data limitations, this analysis has focused on payrolled employments and not self-employment, for which there is limited evidence. Prior to the end of FoM and the pandemic, 27% of all the EEA self-employed worked in construction, making up 5% of the total workforce, as well as over 2% of employment in administration, logistics and the arts. According to the ONS, self-employment has fallen from a peak of 5 million at the end of 2019 to 4.2 million in Q2 2022. It is unclear to what extent this has been driven by exits of the EU born self-employed.