Malaria imported into the UK: 2021

Updated 3 December 2024

Introduction

Malaria is a serious and potentially life-threatening febrile illness caused by infection with protozoan parasites of the genus Plasmodium. It is transmitted to humans by the bite of the female Anopheles mosquito in tropical and subtropical regions of the world. There are 5 species of Plasmodium that infect humans: P. falciparum (responsible for the most severe form of malaria and the most deaths), P. vivax, P. ovale, P. malariae and P. knowlesi.

Malaria is not currently transmitted in the UK, but travel-associated cases occur in those who have returned to or arrived in the UK from malaria-endemic areas.

More information about malaria is available on the Malaria: guidance, data and analysis web page.

Methodology

This report presents data on malaria imported into the United Kingdom (UK) in 2021, mostly based on figures reported to the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) Malaria Reference Laboratory (MRL).

The MRL data set is the most complete source of information about malaria available in the UK, and one of the most complete internationally. A capture-recapture study estimated that the MRL surveillance system captured 56% of cases in England (66% for Plasmodium falciparum and 62% for London cases) (1). For identified cases, some of the epidemiological information is incomplete (2). The MRL relies on information supplied by the notifying laboratory, medical personnel or coroner, and where this information is not known or not supplied, some of the epidemiological information is incomplete. Where a malaria-associated death is notified, further detailed information is requested as part of a national audit into deaths from imported malaria.

Malaria surveillance data is used to inform the UK malaria prevention strategy (3) so it is essential that the data is as complete as possible. Since 2013, the UKHSA Travel Health and International Health Regulations (IHR) team (previously the PHE Travel and Migrant Health Section Health) has further improved the quality of this data set by ensuring that cases, and additional epidemiological information, reported in the UKHSA public health case management database (HPZone) are also included in the final data set.

Malaria is a notifiable disease in the UK and clinical and laboratory staff are obligated under law to notify cases to their proper officer (4). However, in 2021, only 10% of malaria cases reported to MRL were officially notified (5). Clinical and laboratory staff are therefore reminded of the need to notify cases to the designated local public health authority and to report all cases to the UKHSA MRL. Download the Malaria: risk assessment form.

Data analysis for this report was conducted by the UKHSA Travel Health and IHR team and colleagues at MRL have reviewed and approved the report. For the purpose of the analysis, the United Nations (UN) regions were used to assign region of travel and each region was assigned based on the stated country of travel (6).

General trend

In 2021, 1,012 cases of imported malaria were reported in the UK (954 in England, 29 in Scotland, 21 in Wales and 8 in Northern Ireland). This is 79% higher than numbers reported in 2020 (564 cases) and 29% below the mean number of 1,425 cases reported annually between 2012 and 2021.

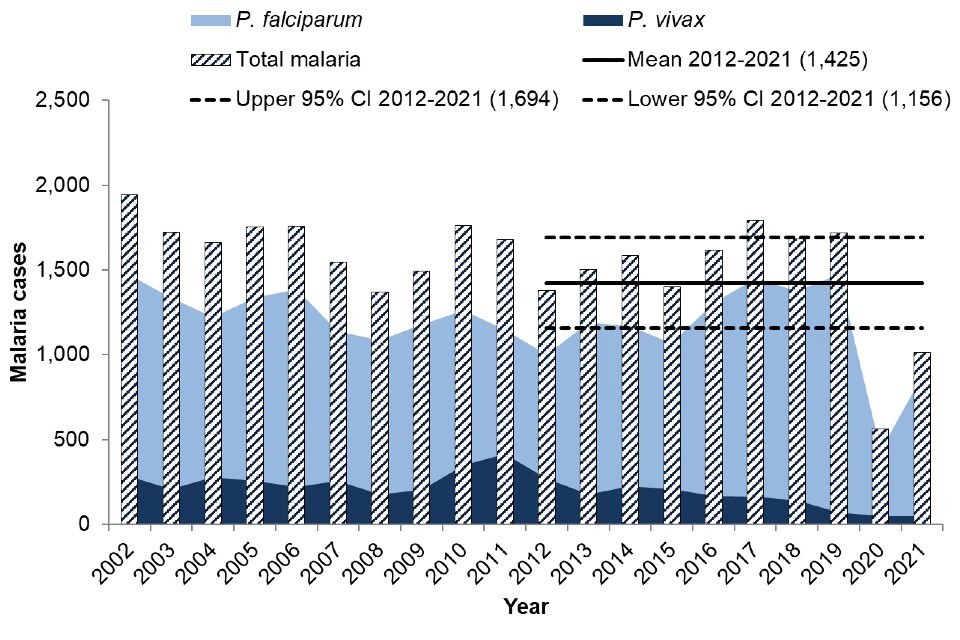

Figure 1. Cases of malaria in the United Kingdom: 2002 to 2021

In the 10 years between 2012 and 2021, the total number of malaria cases reported in the UK each year has fluctuated around a mean of 1,425 (95% CI: 1,156 to 1,694), which is slightly lower than the mean for 2011 to 2020 (1,492, 95% CI: 1,239 to 1,744), and much lower than the mean for 2010 to 2019 (1,612, 95% CI: 1,508 to 1,715). This continued decrease can be attributed to the drastically reduced case numbers in 2020 and 2021.

The great majority of malaria cases diagnosed in the UK in 2021 were caused by P. falciparum, which is consistent with previous years and reflects the global epidemiology of malaria. The total proportion of cases caused by P. falciparum increased in 2021 compared to 2020, whereas the proportion of cases caused by both P. vivax and P. ovale decreased. The number of cases caused by other species remained similar (see table 1). Malaria caused by P. falciparum is of the most interest, because as well as accounting for the most cases, it also causes the most serious disease. Although P. ovale accounts for a slightly higher proportion of cases than P. vivax, P. vivax is of greater interest as it can have more serious disease implications. Of the parasites that cause malaria, P. falciparum is the most prevalent species in Africa and P. vivax is the dominant species in most other countries (7).

Table 1. Malaria cases in the UK by species: 2020 and 2021

| Malaria parasite | Cases (% of total): 2021 | Cases (% of total): 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| P. falciparum | 868 (85.8%) | 437 (77.5%) |

| P. vivax | 50 (4.9%) | 48 (8.5%) |

| P. ovale | 66 (6.5%) | 57 (10.1%) |

| P. malariae | 26 (2.6%) | 17 (3.0%) |

| Mixed infection | 2 (0.2%) | 4 (0.7%) |

| P. knowlesi | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.2%) |

| Total | 1,012 | 564 |

Death from malaria

Three deaths were reported in malaria cases in the UK in 2021, which is a decrease compared to to an annual average of 6 deaths between 2012 and 2021. The proportion of cases resulting in death was 0.3% in 2021: a slight decrease from the average of 0.4% between 2012 and 2021 although numbers are too small to make comparison meaningful. All 3 deaths in 2021 were cases diagnosed with falciparum malaria. Of the fatal cases, 2 were male and one was female. Ethnicity was known for 2 cases, of which one was black African and the other was of African descent.

One patient died at home following travel that included, but may not have been limited to, Southern Africa. The diagnosis of cerebral malaria as the cause of death was made at post-mortem; a nasal swab was incidentally positive for SARS-CoV-2. The other 2 patients both died in hospital with diagnoses of COVID-19 and malaria, one patient had visited Middle Africa and the other visited Eastern Africa.

Reason for travel was known for all 3 cases: 2 travelled abroad from the UK (one for a holiday and one travelled to visit friends and relatives (VFR)) and the other case travelled for business. UK geographical region was known in all cases: 2 deaths were in malaria cases presenting in London and the other presented outside London, giving case fatality rates of 0.4% and 0.2% respectively. History of malaria prophylaxis use was known in 2 cases: in one case no prophylaxis was taken, in the other an unknown herbal medication was taken. Time from onset of symptoms to initiation of treatment was known in one case and was 12 days.

Age and sex

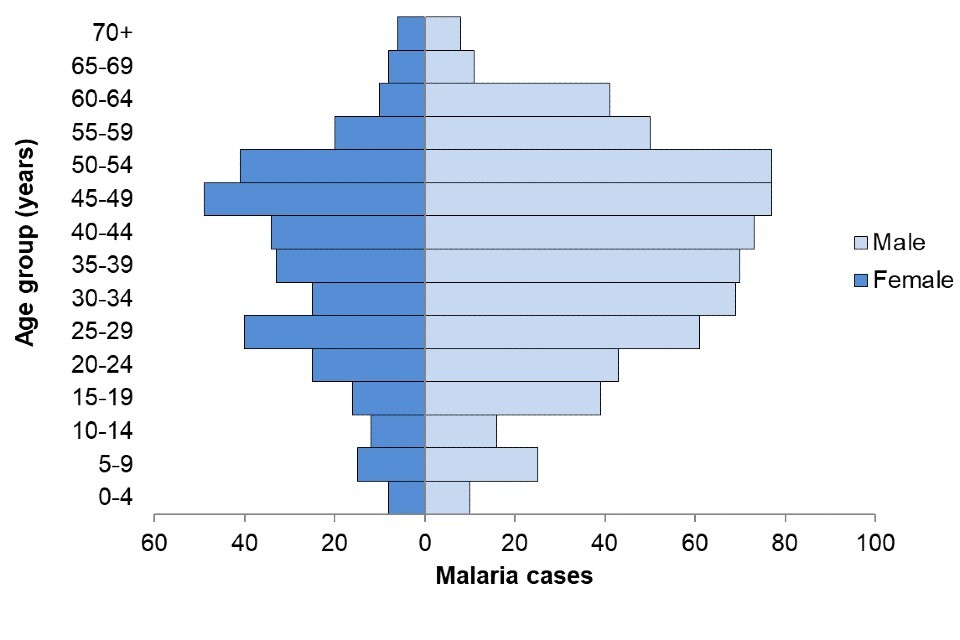

Age and sex were known for all malaria cases (1,012 cases). The majority of cases (66%, 670 out of 1,012) were male, consistent with previous years. The median age was 40 years for males and 39 years for females. Children aged less than 18 years old accounted for 12% (118) of all cases. During the period 2000 to 2021, the median age of those who died from falciparum malaria was 52 years. UKHSA MRL data over 27 years demonstrates that older age is a major risk factor for both falciparum malaria and severe vivax malaria (8, 9).

Figure 2. Cases of malaria in the United Kingdom by age and sex: 2021 (total 1,012 cases)

Geographical distribution

Consistent with previous years, London reported the largest proportion of malaria cases in the UK in 2021, accounting for almost half of all UK cases (49%, 498 out of 1,012). All UKHSA regions saw a large increase in cases in 2021 compared with 2020, ranging from a relatively small increase of 17% in the East Midlands (England) to a 950% increase in Wales (see table 2).

Table 2. Cases of malaria in the United Kingdom by geographical distribution, 2021 and 2020

| Geographical area (UKHSA Centre) | 2021 | 2020 | % change |

|---|---|---|---|

| London | 498 | 285 | 75% |

| South East | 92 | 39 | 136% |

| East of England | 91 | 39 | 133% |

| North West | 75 | 47 | 60% |

| West Midlands | 71 | 45 | 58% |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 52 | 28 | 86% |

| South West | 30 | 24 | 25% |

| East Midlands | 27 | 23 | 17% |

| North East | 18 | 8 | 125% |

| England total | 954 | 538 | 77% |

| Scotland | 29 | 20 | 45% |

| Wales | 21 | 2 | 950% |

| Northern Ireland | 8 | 4 | 100% |

| UK total | 1,012 | 564 | 79% |

Travel history and ethnic origin

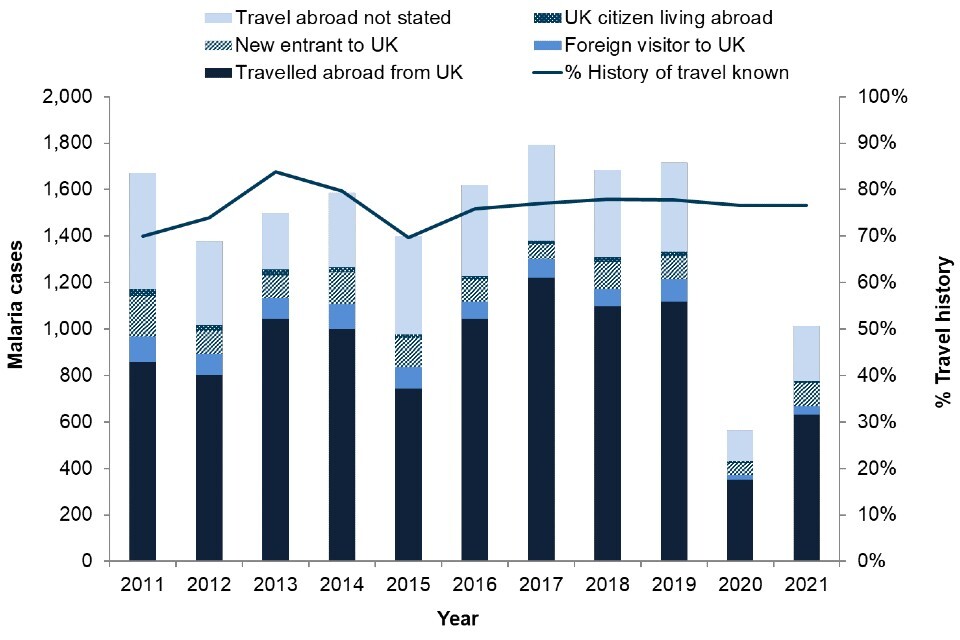

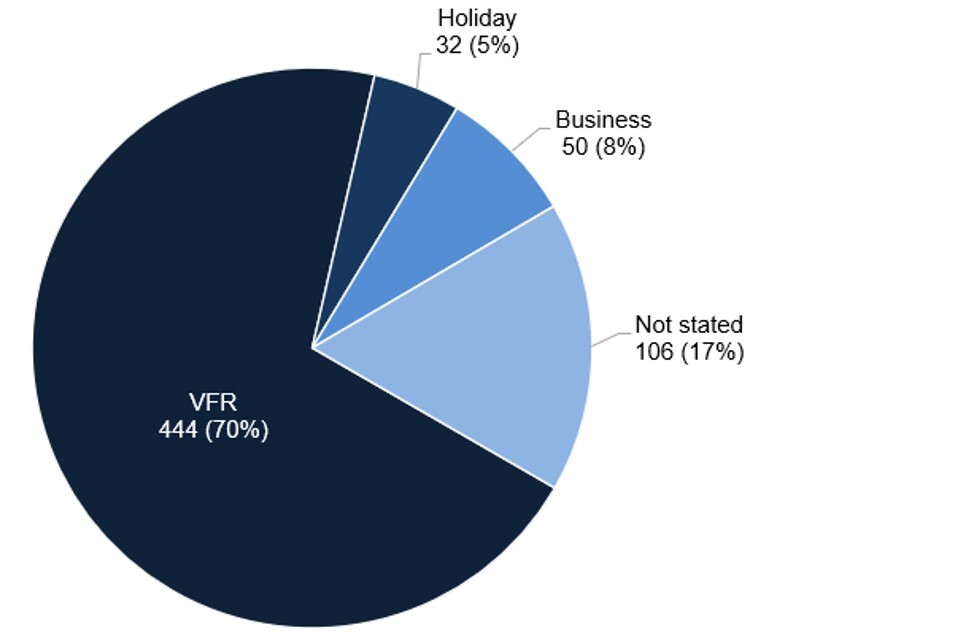

Of malaria cases with information available on travel history, reason for travel, and/or country of residence (960 out of 1,012, 95%), the majority were UK residents travelling abroad (632 out of 960, 66%) (see figure 3). Of the cases in UK residents who travelled abroad, reasons for travel were known in 526 cases (83%) (see figure 4) and include:

- visiting friends and relatives (VFR): 444 out of 526 (84%)

- business or professional (including armed forces and civilian/air crew): 50 out of 526 (10%)

- travel for holiday: 32 out of 526 (6%)

Of the remaining cases where travel status was known, 10% (99 out of 960) were new entrants to the UK (also includes foreign students), 4% (36 out of 960) were foreign visitors to the UK and less than 1% (8 out of 960) were UK citizens living abroad who travelled to the UK.

Figure 3. Travel history and reasons for travel in malaria cases in the UK: 2012 to 2021

Figure 4. Reason for travel for malaria cases that travelled abroad from the UK: 2021 (total 632 cases)

Country or region of birth for cases that travelled abroad from the UK

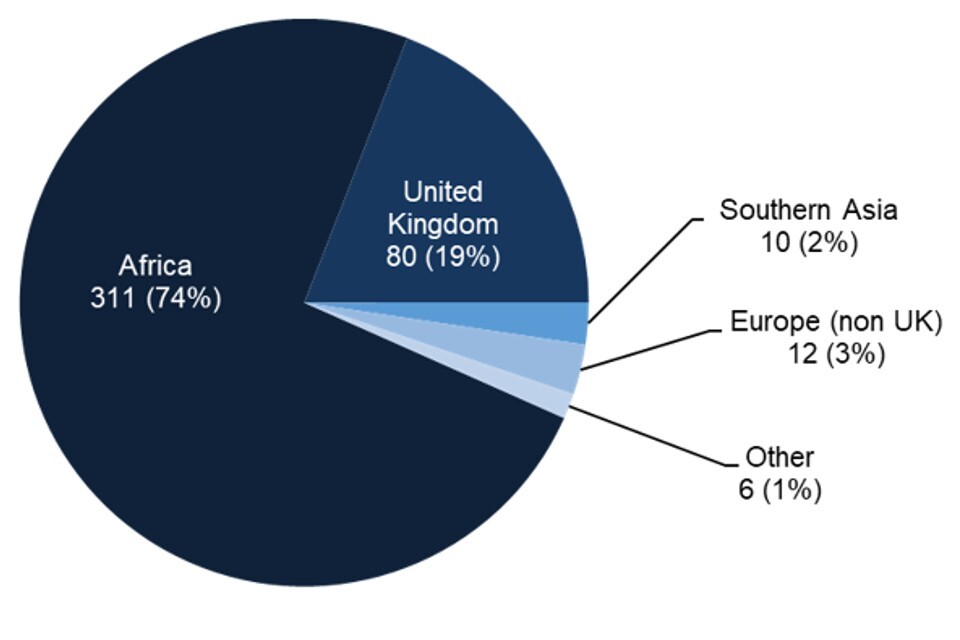

Country or region of birth information was known for 419 (66%) of 632 cases that travelled abroad from the UK, of which almost three-quarters (311, 74%) were born in Africa, 80 cases (19%) were born in the UK, 12 cases (3%) were born in non-UK Europe, 10 cases (2%) were born in Southern Asia, and 6 cases (1%) in other regions. The breakdown of region of birth for malaria cases that have travelled abroad from the UK is shown in (see figure 5).

Figure 5. Region of birth for malaria cases who travelled abroad from UK: 2021 (total 419 cases)

Table 3. Malaria cases who travelled abroad from the UK by region of birth and proportion of VFR travellers: 2021 (total 377 cases)

| Region or country of birth | N | VFR | % VFR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 280 | 273 | 98% |

| UK | 70 | 35 | 50% |

| Indian subcontinent | 10 | 8 | 80% |

| Other (includes non-UK Europe) | 17 | 10 | 59% |

Notes:

- N is the number of cases where region of birth and reason for travel was known.

- the Indian subcontinent comprises Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

Ethnicity of cases that travelled abroad from the UK

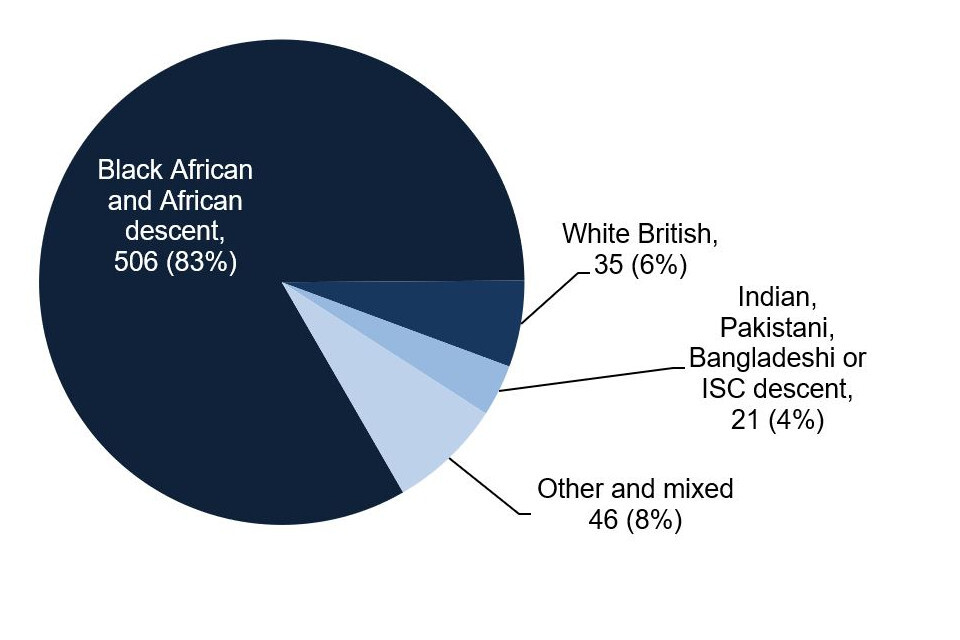

Of the malaria cases that travelled abroad from the UK, (where ethnicity was known) more than 4 out of 5 were of black African ethnicity and/or of African descent (83%, 506 out of 608) Of the remaining cases, 35 (6%) were white British, 21 (4%) were Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi or Indian subcontinent (ISC) descent, and 46 (8%) were of other or mixed ethnicity. The breakdown of ethnicity for malaria cases that have travelled abroad is shown in figure 6.

For non-white British cases that travelled abroad from the UK, 438 out of 572 (77%) were visiting friends or relatives. For white British cases that travelled abroad from the UK, 2 out of 35 (6%) travelled to visit friends or relatives.

Of the 3 deaths reported, 2 cases were of black African ethnicity and/or of African descent, and the other was of other white ethnicity. Reason for travel was visiting friends and relatives in one death, holiday in one death and work in the other.

Figure 6. Ethnicity for malaria cases that travelled abroad from the UK: 2021 (total 608 cases)

Country or region of travel for cases that travelled from the UK

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 there has been a significant decrease in worldwide travel as many countries, including the UK, imposed restrictions on arriving and departing travellers (10). Data on travel to and from the UK was obtained from the Office of National Statistics (ONS) International Passenger Survey (IPS).

In 2021 UK residents made 19.1 million visits abroad, which was a 20% decrease from 2020 (23.8 million visits) and an 80% decrease from 2019 (93.1 million visits), and there were 6.4 million visits made by overseas residents to the UK, a 43% decrease compared to 2020 (11.1 million visits) and an 84% decrease compared to 2019 (40.9 million visits) (11).

In line with falling numbers of travellers arriving in the UK, the number of malaria infections diagnosed in the UK also decreased in 2021 compared with 2019. However, despite even lower numbers of travellers to and from the UK in 2021 compared with 2020, there was an increase of cases of malaria diagnosed in the UK compared with 2020.

Travel by UK residents from the UK reduced by 83% for holiday travellers between 2019 (51 million visits) and 2021 (8.8 million visits), and reduced by 80% for business travellers between 2019 (7 million visits in 2019) and 2021 (1.4 million visits). In comparison, travel by VFR travellers only reduced by 30% between 2019 (11.7 million visits) and 2021 (8.2 million visits). A large majority of malaria cases who travelled abroad from the UK were VFR travellers, consistent with previous years (87% in 2021, compared with 88% in 2020 and 84% in 2019). Data on overall travel for specific countries was not available for 2020.

Of the top 20 overall most visited countries by UK residents between 2015 and 2021 from the IPS (excluding 2020), India is the only country that is also in the top 20 countries of travel by malaria cases in 2021. Overall travel by UK residents to the top 20 countries of travel for malaria cases in 2021 (listed in table 5) reduced by 58% overall in 2021 compared to 2019 (data not available on overall travel to specific countries for 2020). Travel to Côte D’Ivoire, Sierra Leone and Sudan increased overall in 2021 compared to 2019, but decreased for the remaining 17 countries.

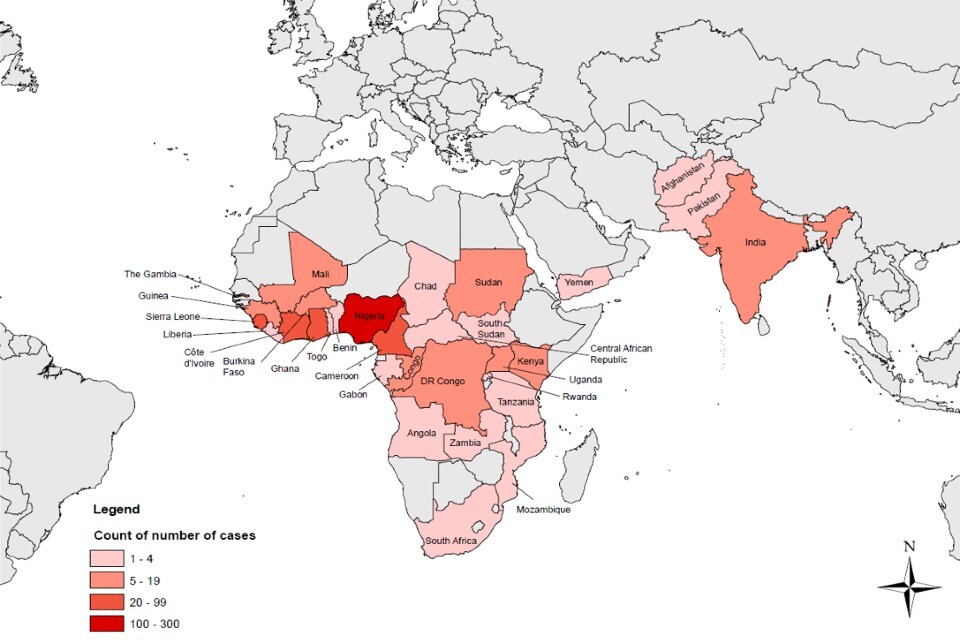

Table 4 shows the breakdown of malaria cases reported by region of travel and parasite species, and the top 20 countries of travel are shown in table 5. Countries of travel for malaria cases reported in 2021 by count of cases is shown in a map in figure 7. The majority of cases (where travel history was known) continue to be acquired in Western Africa, particularly Western Africa where 78% were acquired (491 out of 632), 10% in Middle Africa (61 out of 632) and 6% in Eastern Africa (38 out of 632) in 2021. These numbers reflect in general the global prevalence of malaria infection. In 2021, 29 countries accounted for 96% of malaria cases globally, and 4 countries accounted for almost half of all cases globally (12):

- Nigeria (27%)

- the Democratic Republic of the Congo (12%)

- Uganda (5%)

- Mozambique (4%)

Table 4. Cases of malaria that travelled abroad from the UK by species and region of travel: 2021 and 2020

| Region of travel | P. falciparum | P. vivax | P. ovale | P. malariae | Mixed | 2021 total | 2020 total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western Africa | 457 | - | 24 | 10 | - | 491 | 195 |

| Middle Africa | 58 | - | 2 | 1 | - | 61 | 40 |

| Eastern Africa | 33 | - | 3 | 1 | 1 | 38 | 72 |

| Southern Asia | - | 14 | - | - | - | 14 | 16 |

| Northern Africa | 6 | 5 | 1 | - | - | 12 | 12 |

| Southern Africa | 2 | - | - | - | - | 2 | 1 |

| Africa unspecified | 2 | - | 1 | - | - | 3 | 0 |

| South America | - | - | - | - | - | 0 | 1 |

| Western Asia | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 |

| Not stated | 9 | 1 | - | - | - | 10 | 15 |

| Total | 568 | 20 | 31 | 12 | 1 | 632 | 352 |

Table 5. Cases of malaria that travelled abroad from the UK by Plasmodium species and top 20 countries of travel: 2021 and 2020

| Country of travel | P. falciparum | P. vivax | P. ovale | P. malariae | Mixed | 2021 Total | 2020 Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nigeria | 263 | - | 16 | 7 | - | 286 | 86 |

| Ghana | 62 | - | - | 3 | - | 65 | 27 |

| Sierra Leone | 53 | - | 1 | - | - | 54 | 49 |

| Côte D’Ivoire | 37 | - | 4 | - | - | 41 | 19 |

| Cameroon | 34 | - | 2 | 1 | - | 37 | 14 |

| Uganda | 19 | - | - | - | - | 19 | 26 |

| Sudan | 6 | 5 | 1 | - | - | 12 | 12 |

| Congo | 11 | - | - | - | - | 11 | 14 |

| Guinea | 9 | - | - | - | - | 9 | 3 |

| India | - | 8 | - | - | - | 8 | 9 |

| Gambia | 6 | - | - | - | - | 6 | 2 |

| DR Congo | 6 | - | - | - | - | 6 | 4 |

| Burkina Faso | 5 | - | - | - | - | 5 | 1 |

| Mali | 5 | - | - | - | - | 5 | 1 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 5 | - | - | - | - | 5 | - |

| Kenya | 4 | - | 1 | - | - | 5 | 19 |

| Benin | 4 | - | - | - | - | 4 | 1 |

| Zambia | 4 | - | - | - | - | 4 | 4 |

| Tanzania | 3 | - | - | - | - | 3 | 8 |

| Liberia | 3 | - | - | - | - | 3 | 5 |

| Other Western Africa | 5 | - | 3 | - | - | 8 | 1 |

| Other Eastern Africa | 3 | - | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 15 |

| Other Middle Africa | 7 | - | - | - | - | 7 | 8 |

| Southern Africa | 2 | - | - | - | - | 2 | 1 |

| Other Southern Asia | - | 6 | - | - | - | 6 | 7 |

| Africa unspecified | 2 | - | 1 | - | - | 3 | 5 |

| Western Asia | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | - |

| South America | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| Not stated | 9 | 1 | - | - | - | 10 | 10 |

| Total | 568 | 20 | 31 | 12 | 1 | 632 | 352 |

Figure 7. Countries of travel for cases of malaria that travelled abroad from the UK by count of cases, 2021

Prevention and treatment

Chemoprophylaxis

Among malaria cases that travelled abroad from the UK, where the history of chemoprophylaxis (antimalarial medication to prevent infection) was known, 404 out of 456 (89%) had not taken chemoprophylaxis. This proportion is similar to recent years.

Of those who had taken some form of chemoprophylaxis (52 cases), the choice of drug was stated in all cases, and 43 (83%) had taken a drug that was recommended to UK travellers for their destination by the UKHSA Advisory Committee for Malaria Prevention (ACMP). This represents 9% (43 out of 456) of the total cases where chemoprophylaxis information was available in 2021. The proportion of the total cases with chemoprophylaxis information that took a drug recommended by the ACMP has remained between 9% and 16% between 2000 and 2020, and therefore this one of the lowest proportions of cases in 21 years. Of the 43 cases that took a drug recommended to UK travellers, just 3 (7%) reported that they had taken it regularly. Data on adherence to prophylaxis is subject to recall bias and this should be taken into consideration when interpreting this data. When taken correctly, the agents recommended for prophylaxis against falciparum malaria (atovaquone-proguanil, doxycycline and mefloquine) are more than 90% effective (3).

Among malaria cases that travelled abroad from the UK, where the history of chemoprophylaxis was known, a slightly higher proportion of females had taken some form of chemoprophylaxis than males: 13% of females (19 out of 149 cases) compared with 11% of males (33 out of 307 cases). The median age of cases who had taken some form of chemoprophylaxis (and had travelled abroad from the UK) was 42 years, compared with an median age of 43 years for all cases that had travelled abroad.

This data implies that health messages about the importance of antimalarial chemoprophylaxis still are not reaching groups who are at particular risk of acquiring malaria, or that travellers either are not understanding or are not acting on these messages.

The groups at particular risk of not using chemoprophylaxis include those who are visiting family in their country of origin, particularly those of black African heritage and/or born in Africa. The reasons for this heightened risk have not been investigated systematically, but could include:

- individuals in these groups may not seek or may not be able to access medical advice on malaria prevention before they travel

- they may not receive accurate advice

- they may not adhere to recommendations on chemoprophylaxis

They may not perceive themselves to be at risk (they may have been born or lived in a malaria-endemic area for many years), or they may have concerns about the cost of drugs. The burden of falciparum malaria in particular falls heavily on those of black African heritage, and this group is important to target for pre-travel advice.

Taking fever seriously on return from a malaria risk area

P. falciparum can progress to severe and life-threatening illness, including cerebral malaria, if it is not diagnosed and treated promptly. Travellers returning from malaria risk areas should seek urgent medical advice, including a same-day result malaria blood test, for any symptoms, especially fever, during their trip or in the year following their return home.

Treatment guidelines and algorithms for clinicians are available from the British Infection Association.

Reliability of malaria diagnostic tests

In the UK, malaria is diagnosed by microscopic examination of thick and thin blood films and by rapid immunochromatographic diagnostic tests (RDTs) which detect circulating parasite antigens. RDTs have satisfactory diagnostic accuracy in most clinical situations but should not be relied on alone (13). The most commonly used RDTs detect circulating P. falciparum histidine-rich proteins (HRP2 and HRP3). However, deletions of pfhrp2 and pfhrp3 genes occur in some P. falciparum populations, particularly in regions of the Amazon River basin in South America, and in East Africa, reducing the sensitivity of some RDTs (14). Among 113 UK P. falciparum samples from East Africa in 2018, 23 (20.4%) showed evidence of deletion of at least one of these 2 genes (15). The MRL has characterised in detail a further 5 cases where a false-negative HRP2 RDT result was obtained by the sending laboratory, prior to confirmation of P. falciparum infection by microscopy (16). The implications of pfhrp2 and pfhrp3 gene deletions for RDT use is under investigation by the WHO, and further guidance is expected, but these tests remain an important additional diagnostic tool for imported malaria in the UK. In the UK, blood film microscopy is of a high standard and should be performed on all suspected malaria cases, whether or not an RDT is used. The British Society for Haematology Guidelines for the laboratory diagnosis of malaria, revised in May 2022 (16), provide the necessary guidance.

Antimalarial treatment failure in UK patients

In 2017 the MRL reported 4 cases of treatment failure among UK patients receiving artemether-lumefantrine (Riamet™) for P. falciparum infections (17). Since that time a further 21 suspected cases have been reported and are under investigation by the MRL. Mutations in the pfk13 gene, associated with reduced parasite susceptibility to artemisinins in South-Eastern Asia, were not found except in a single case of P. falciparum imported from Cambodia. Treatment failures represent a tiny proportion of notified P. falciparum cases in the UK - in 2019 8 suspected P. falciparum post-treatment recurrences were identified by passive surveillance at the MRL, out of a total of 1,475 reported cases (0.05%). Riamet™ remains highly effective and recommended for treatment of UK cases. However, clinicians should be aware of this issue, and of the potential need for prolonged or alternative treatment in rare cases of parasite recrudescence.

Prevention is key

Malaria, an almost completely preventable but potentially fatal disease, remains an important issue for UK travellers. Failure to take chemoprophylaxis correctly is associated with the majority of cases of malaria in UK residents travelling to malaria-risk areas. The number of cases in those going on holiday is small but associated with greater mortality (8). Those of African or Asian ethnicity who are non-UK born and who travel to visit friends and relatives are at increased risk of malaria, as well as a number of other infections (18). Older patients are at particular risk of dying from malaria if they acquire the infection. Those providing advice should engage with these population groups wherever possible, including using potential opportunities to talk about future travel plans outside a specific travel health consultation, such as during new patient checks or childhood immunisation appointments (19).

The ACMP guidelines (3) and National Travel Health Network and Centre are available to assist clinicians in helping travellers to make rational decisions about protection against malaria.

Useful resources for travellers, including translated leaflets, are also available at Malaria: health advice for travellers.

References

1. Cathcart SJ, Lawrence J, Grant A, Quinn D, Whitty CJ, Jones J, and others. ‘Estimating unreported malaria cases in England: a capture-recapture study’ Epidemiology and Infection 2010: volume 138, issue 7, pages 1,052 to 1,058.

2. UKHSA. ‘Imported malaria in the UK: statistics’ (accessed 27 October 2022).

3. Chiodini PL, Patel D, Goodyer L and Ranson H. ‘Guidelines for malaria prevention in travellers from the United Kingdom, 2022’.

4. UKHSA. ‘Notifications of infectious diseases (NOIDs)’ (accessed 27 October 2022).

5. UKHSA. ‘Notified diseases: 2020 annual figures’ (accessed 27 October 2022).

6. United Nations Statistics Division. ‘Composition of macro geographical (continental) regions, geographical sub-regions, and selected economic and other groupings’ (accessed 27 October 2022).

7. World Health Organization (WHO). ‘Malaria factsheet’ (accessed 15 December 2022)

8. Checkley AM, Smith A, Smith V, Blaze M, Bradley D, Chiodini PL and others. ‘Risk factors for mortality from imported falciparum malaria in the United Kingdom over 20 years: an observational study’ British Medical Journal 27 March 2012: volume 344, page e2116.

9. Broderick C, Nadjm B, Smith V, Blaze M, Checkley A, Chiodini PL, Whitty CJM. ‘Clinical, geographical, and temporal risk factors associated with presentation and outcome of vivax malaria imported into the United Kingdom over 27 years: observational study’ British Medical Journal 16 April 2015: volume 350:h1703.

10. Office for National Statistics (ONS). ‘Coronavirus and the impact on the UK travel and tourism industry’ (accessed 27 October 2022).

11. ONS. ‘Travel trends: 2021’ (accessed 27 October 2022).

12. WHO. ‘World malaria report 2021’ (accessed 27 October 2022).

13. Rogers CL, Bain BJ, Garg M, Fernandes S, Mooney C, Chiodini PL, British Society for Haematology. ‘British Society for Haematology guidelines for the laboratory diagnosis of malaria’ British Journal of Haematology May 2022: volume 197, issue 3, pages 271 to 282.

14. ML Gatton and others. ‘Impact of Plasmodium falciparum gene deletions on malaria rapid diagnostic test performance’ Malaria Journal 4 November 2020: volume 19, issue 1, page 392.

15. Grignard L, Nolder D, Sepulveda N, Berhane A, Mihreteab S, Kaaya R and others. ‘A novel multiplex qPCR assay for detection of Plasmodium falciparum with histidine-rich protein 2 and 3 (pfhdpr2 and pfhrp3) deletions in polylclonal infections’ EBioMedicine 2020: volume 55, page 102,757.

16. Nolder D, Stewart L, Tucker J, Ibrahim A, Gray A, Corrah T and others. ‘Failure of rapid diagnostic tests in Plasmodium falciparum malaria cases among travelers to the UK and Ireland: identification and characterisation of the parasites’ International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2021: volume 108, pages 137 to 144.

17. Sutherland CJ, Lansdell P, Sanders M, Muwanguzi J, van Schalkwyk DA, Kaur H and others. ‘pfk13-independent treatment failure in 4 imported cases of Plasmodium falciparum malaria treated with artemether-lumefantrine in the United Kingdom’ Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2017: volume 61: pages e02382 to e02316.

18. Wagner KS, Lawrence J, Anderson L, Yin Z, Delpech V, Chiodini PL and others. ‘Migrant health and infectious diseases in the UK: findings from the last 10 years of surveillance’ Journal of Public Health 2014: volume 36, issue 1, pages 28 to 35.

19. Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID). Migrant health guide (accessed 27 October 2022).