Malaria imported into the UK: 2020

Updated 3 December 2024

Malaria is a serious and potentially life-threatening febrile illness caused by infection with protozoan parasites of the genus Plasmodium. It is transmitted to humans by the bite of the female Anopheles mosquito in tropical and subtropical regions of the world. There are 5 species of Plasmodium that infect humans: P. falciparum (responsible for the most severe form of malaria and the most deaths), P. vivax, P. ovale, P. malariae and P. knowlesi.

Malaria is not currently transmitted in the UK, but travel-associated cases occur in those who have returned to the UK or arrived in the UK from malaria-endemic areas.

More information about malaria is available at Malaria: guidance, data and analysis.

Methodology

This report presents data on malaria imported into the UK in 2020, mostly based on figures reported to the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) Malaria Reference Laboratory (MRL).

The MRL dataset is the most complete source of information about malaria available in the UK, and one of the most complete internationally. A capture-recapture study estimated that the MRL surveillance system captured 56% of cases in England (66% for Plasmodium falciparum and 62% for London cases) (1). For identified cases some of the epidemiological information is incomplete (2).The MRL relies on information supplied by the notifying laboratory, medical personnel or coroner, and where this information is not known or not supplied, some of the epidemiological information is incomplete. Where a malaria-associated death is notified, further detailed information is requested as part of a national audit into deaths from imported malaria.

Malaria surveillance data are used to inform the UK malaria prevention strategy (3) so it is essential that the data are as complete as possible. Since 2013, the UKHSA Travel Health and International Health Regulations (IHR) team (previously the PHE Travel and Migrant Health Section) has further improved the quality of this dataset by ensuring that cases and additional epidemiological information, reported in the UKHSA public health case management database (HPZone) are also included in the final dataset.

Malaria is a notifiable disease in the UK and clinical and laboratory staff are obligated under law to notify cases to their proper officer (4). However, in 2020, only 10% of malaria cases reported to MRL were officially notified (5). Clinical and laboratory staff are therefore reminded of the need to notify cases to the designated local public health authority and to report all cases to the UKHSA MRL. Download the Malaria: risk assessment form.

Data analysis for this report was conducted by the UKHSA Travel Health and IHR team and colleagues at the MRL have reviewed and approved the report. For the purpose of the analysis, the United Nations (UN) regions were used to assign region of travel and each region was assigned based on the stated country of travel (6).

General trend

In 2020, 564 cases of imported malaria were reported in the UK (538 in England, 20 in Scotland, 4 in Northern Ireland and 2 in Wales). This is 67% lower than numbers reported in 2019 (1,719 cases) and 62% below the mean number of 1,492 cases reported annually between 2011 and 2020.

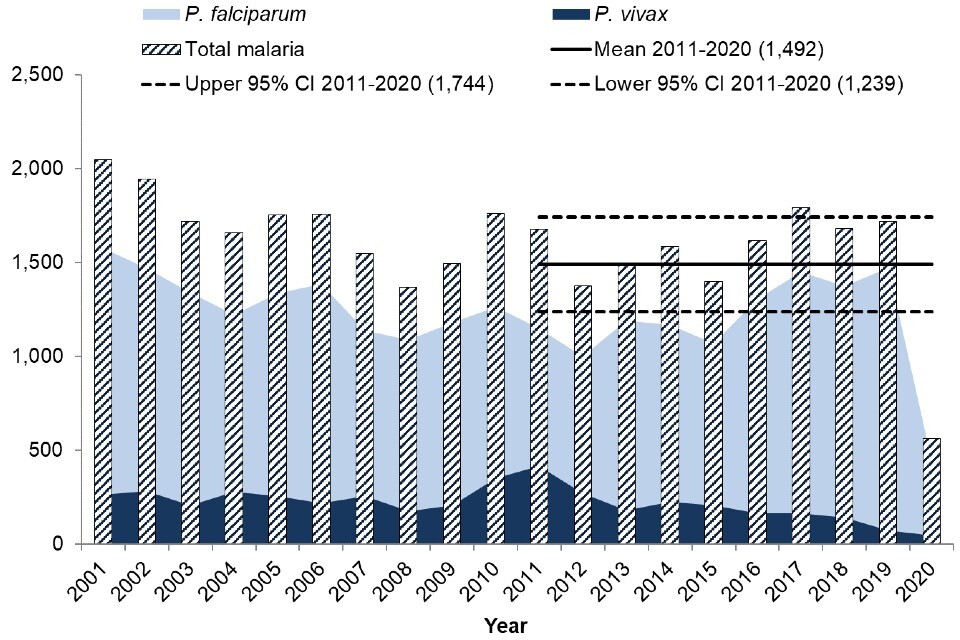

Figure 1. Cases of malaria in the United Kingdom: 2001 to 2020

In the 10 years between 2011 and 2020, the total number of malaria cases reported in the UK each year fluctuated around a mean of 1,492 (95% CI: 1,239 to 1,744), which is lower than the mean for the period 2010 to 2019 (1,612 (95% CI: 1,508 to 1,715)). This decrease can be mostly attributed to the drastically reduced case numbers in 2020.

The great majority of malaria cases diagnosed in the UK in 2020 were caused by P. falciparum, which is consistent with previous years and reflects the global epidemiology of malaria. The total proportion of cases caused by P. falciparum decreased in 2020 compared to 2019, whereas the proportion of cases caused by both P. vivax and P. ovale increased, possibly due to their propensity to present later. The number of cases caused by other species remained similar (see table 1).

Malaria caused by P. falciparum is of the most interest, since as well as accounting for the most cases it also causes the most serious disease. Although P. ovale accounts for a slightly higher proportion of cases than P. vivax, P. vivax is of greater interest as it can have more serious disease implications. Of the parasites that cause malaria, P. falciparum is the most prevalent species in Africa and P. vivax is the dominant species in most other countries where malaria is found (7).

Table 1. Malaria cases in the UK by species: 2019 and 2020

| Malaria parasite | Cases (% of total) 2020 | Cases (% of total) 2019 |

|---|---|---|

| P. falciparum | 437 (77.5%) | 1,475 (85.8%) |

| P. vivax | 48 (8.5%) | 72 (4.2%) |

| P. ovale | 57 (10.1%) | 114 (6.6%) |

| P. malariae | 17 (3.0%) | 43 (2.5%) |

| Mixed infection | 4 (0.7%) | 14 (0.8%) |

| P. knowlesi | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (<0.1%) |

| Total | 564 | 1,719 |

Death from malaria

Five deaths from malaria were reported in the UK in 2020. This is a slight decrease compared to the annual average of 6 deaths between 2011 and 2020, however the proportion of cases resulting in death was much higher in 2020: 0.9% compared with an average of 0.4% between 2011 and 2020. All 5 deaths in 2020 were from falciparum malaria and were known to be acquired in Africa: Eastern Africa (2), Western Africa (2) and Middle Africa (1).

Reason for travel was known in 4 cases: 2 travelled abroad from the UK (one for a holiday and one travelled to visit friends and relatives (VFR)), and 2 were UK citizens living abroad. UK geographical region was known in all cases: 3 deaths were in malaria cases presenting in London and 2 presented outside London, giving case fatality rates of 1.1% and 0.7% respectively. History of malaria prophylaxis use was known in 3 cases: one took no prophylaxis, one took intermittent prophylaxis and one of the cases was reported as taking a drug recommended to UK travellers for their destination by the UKHSA Advisory Committee for Malaria Prevention (ACMP) with regular adherence.

Of the fatal cases, 3 were male and 2 were female: 2 were white British, 2 were of African descent and one was of other white ethnicity. The median age was 54 years (range 28 years to 88 years). Four of the cases were treated in hospital and one person died in the community without having accessed medical treatment. Of the 3 cases where time from onset of symptoms to initiation of treatment was known, it took 4 days for initiation of treatment for 2 of the cases and 2 days for the remaining case. It is unknown whether the remaining 2 cases received any treatment for their malaria infection. Parasitaemia in the 3 fatal cases where this information was available was 7.6%, 12% and 23% with schizonts.

The higher proportion of fatal cases in the context of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic is of significant concern. NHS advice during this period was to stay at home if you have a fever, and a delayed presentation to hospital contributed to a fatal outcome in at least one case.

Numbers are too small to draw definite conclusions from these data, but the higher case fatality rate seen in those born outside Africa reflect published data from a large observational study of UK malaria deaths (8).

Age and sex

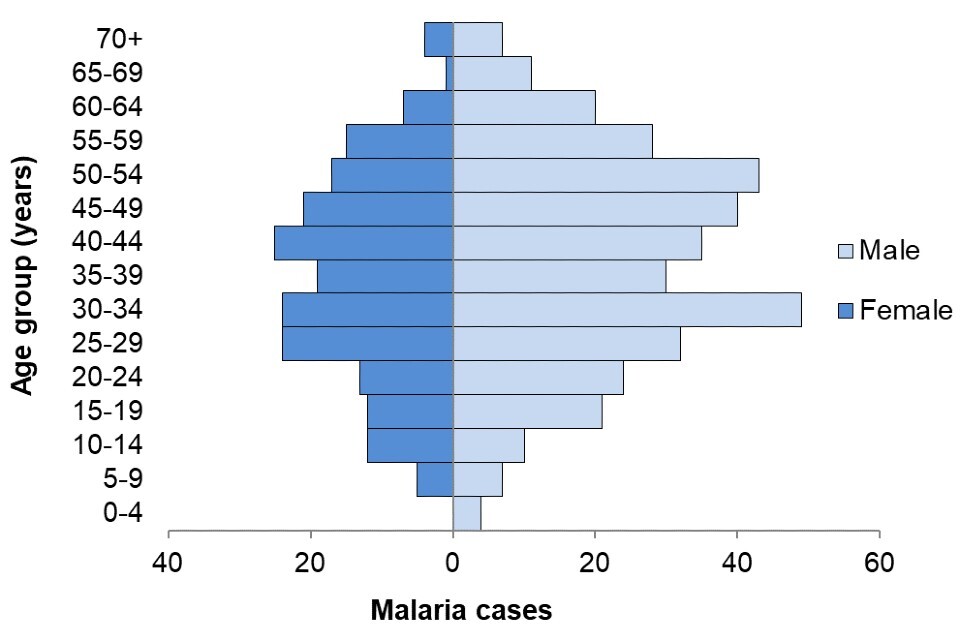

Age and sex were known for 99% of malaria cases (561 out of 564). The majority of cases (65%, 362 out of 561) were male, consistent with previous years. The median age was 40 years for males and 37 years for females. Children aged less than 18 years old accounted for 10% (58) of all cases. During the period 2000 to 2020, the median age of those who died from falciparum malaria was 52 years. UKHSA MRL data over 27 years demonstrate that older age is a major risk factor for both falciparum malaria and severe vivax malaria (8, 9).

Figure 2. Cases of malaria in the United Kingdom by age and sex: 2020 (total 561 cases)

Geographical distribution

Consistent with previous years, London reported the largest proportion of malaria cases in the UK in 2020, accounting for more than half of all UK cases (51%, 285 out of 564). All UKHSA regions saw a large decrease in cases in 2020 compared with 2019, ranging from a decrease of 53% in the South West of England to a decrease of 92% in Wales (see table 2).

Table 2. Cases of malaria in the United Kingdom by geographical distribution, 2020 and 2019

| Geographical area (UKHSA centre) | 2020 | 2019 | % change |

|---|---|---|---|

| London | 285 | 880 | -68% |

| North West | 47 | 173 | -73% |

| West Midlands | 45 | 121 | -63% |

| South East | 39 | 122 | -68% |

| East of England | 39 | 112 | -65% |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 28 | 81 | -65% |

| South West | 24 | 51 | -53% |

| East Midlands | 23 | 61 | -62% |

| North East | 8 | 25 | -68% |

| England total | 538 | 1,626 | -67% |

| Scotland | 20 | 58 | -66% |

| Wales | 2 | 25 | -92% |

| Northern Ireland | 4 | 10 | -60% |

| UK total | 564 | 1,719 | -67% |

Travel history and ethnic origin

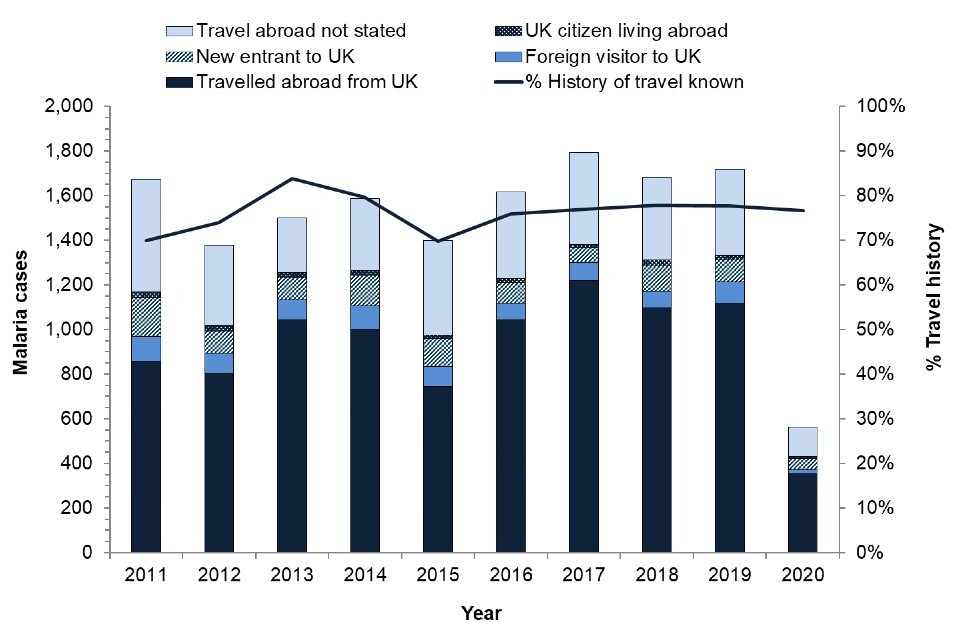

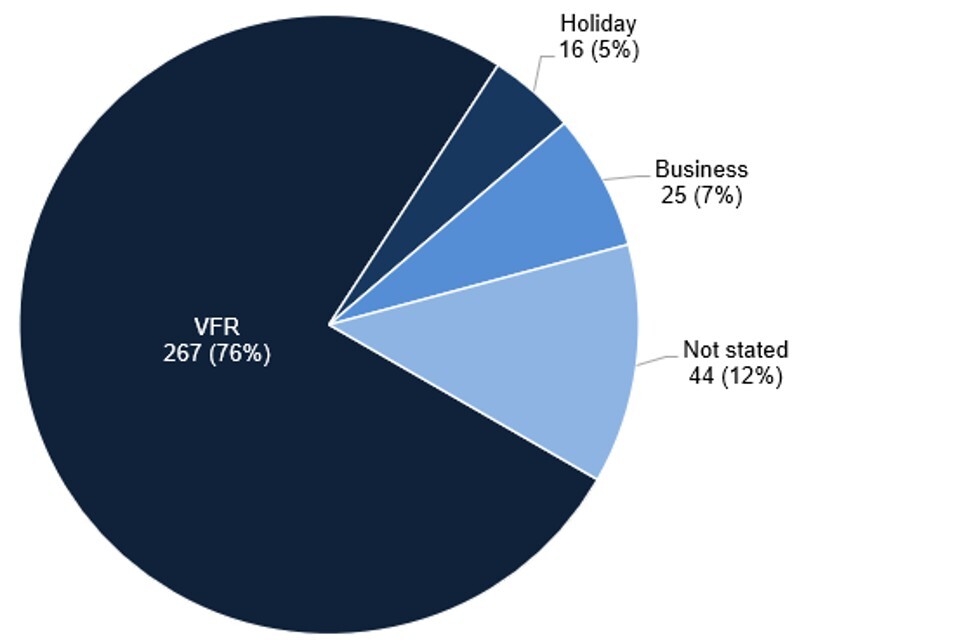

Of malaria cases with information available on travel history, reason for travel, and/or country of residence (523 out of 564, 93%), the majority were UK residents travelling abroad (352 out of 523, 67%) (see figure 3). Of the cases in UK residents who travelled abroad, reasons for travel were known in 308 cases (88%) (see figure 4) and included:

- visiting friends and relatives: 267 out of 308 (87%)

- business or professional (including armed forces and civilian or air crew): 25 out of 308 (8%)

- travel for holiday: 16 out of 308 (5%)

Of the remaining cases where travel status was known, 10% (50 out of 523) were new entrants to the UK (also includes foreign students), 4% (20 out of 523) were foreign visitors to the UK and 2% were UK citizens living abroad who travelled to the UK. One case of malaria with no recent history of travel was reported, in a case who had lived in a malaria endemic country in Africa over 14 years previously. This individual was a semi-immune person whose malaria infection had become clinically active due to pregnancy (not shown in figure 3).

Figure 3. Travel history and reasons for travel in malaria cases in the UK: 2011 to 2020

Figure 4. Reason for travel for malaria cases that travelled abroad from the UK: 2020 (total 352 cases)

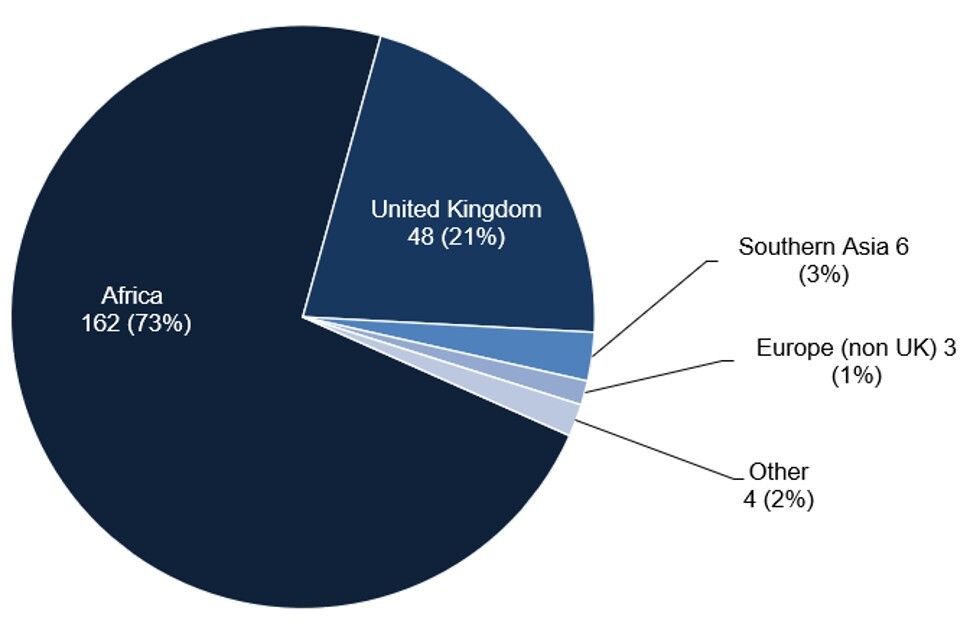

Country or region of birth for cases that travelled abroad from the UK

Country or region of birth information was known for 223 (63%) of the 352 cases that travelled abroad from the UK, of which almost three-quarters (162; 73%) were born in Africa, 48 cases (22%) were born in the UK, 6 cases (3%) were born in Southern Asia, 3 cases (1%) were born in non-UK Europe and 4 cases (2%) in other regions. The breakdown of region of birth for malaria cases that travelled abroad from the UK is shown in figure 4.

Figure 5. Region of birth for malaria cases who travelled abroad from UK: 2020 (total 223 cases)

Table 3. Malaria cases who travelled abroad from the UK by region of birth and proportion of VFR travellers: 2020 (total 210 cases where region of birth and reason for travel was known)

| Region or country of birth | N | VFR | % VFR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 155 | 154 | 99% |

| UK | 43 | 22 | 51% |

| Indian subcontinent | 6 | 5 | 83% |

| Other (includes non-UK Europe) | 6 | 3 | 50% |

Notes:

- N is the number of cases where region of birth and reason for travel was known.

- the Indian subcontinent comprises Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

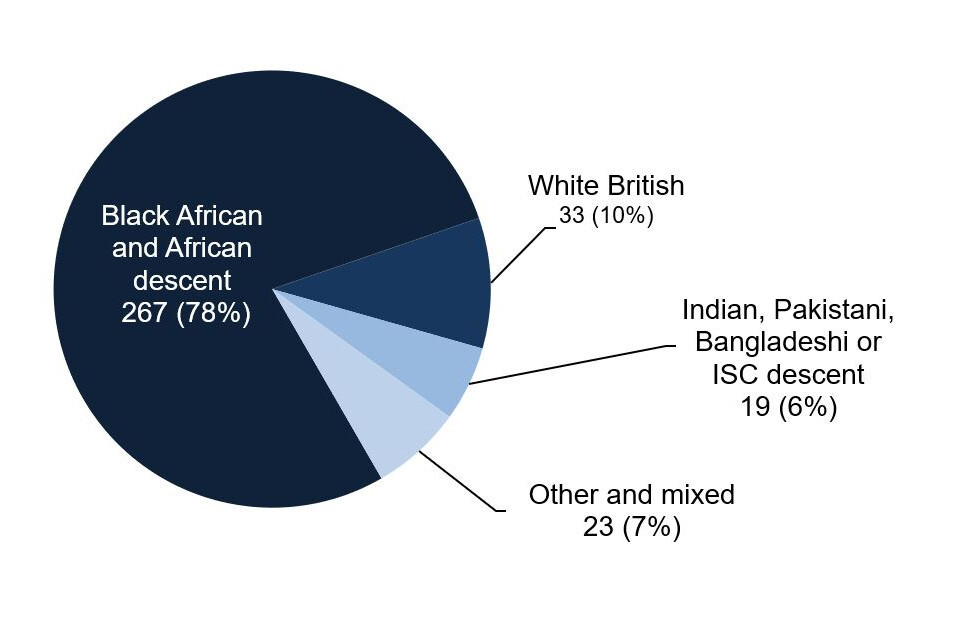

Ethnicity of cases that travelled abroad from the UK

Of the malaria cases that travelled abroad from the UK, (where ethnicity was known) more than three-quarters were of black African ethnicity and/or of African descent (78%; 267 out of 342) (African descent is determined from country of birth if ethnicity is not given). Of the remaining cases, 33 (10%) were white British, 19 (6%) were Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi or Indian subcontinent (ISC) descent, and 23 (7%) were of other or mixed ethnicity. The breakdown of ethnicity for malaria cases that travelled abroad is shown in figure 5.

For non-white British cases that travelled abroad from the UK, 264 out of 309 (85%) were visiting friends or relatives. For white British cases that travelled abroad from the UK, one out of 33 (3%) travelled to visit friends or relatives.

Of the 5 deaths reported, 2 cases were of black African ethnicity and/or of African descent, 2 were white British, and one was of other white ethnicity. 4 of these 5 cases had known travel history. Of these cases, 2 had travelled abroad from the UK (one was a VFR traveller and one was a holiday traveller) and the remaining 2 were UK citizens living abroad.

Figure 6. Ethnicity for malaria cases that travelled abroad from the UK: 2020 (total 342 cases)

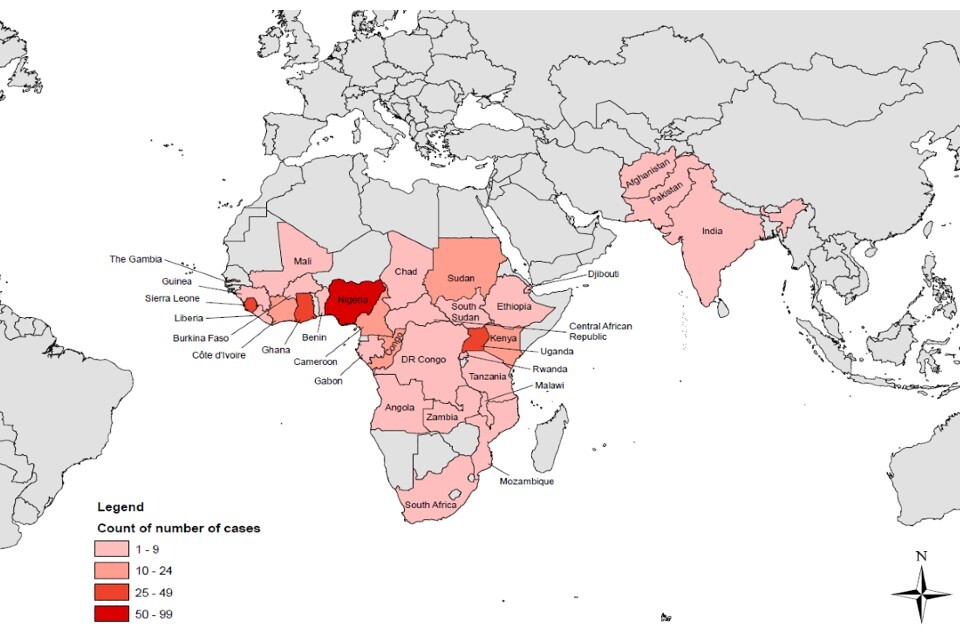

Country or region of travel for cases that travelled from the UK

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 there has been a significant decrease in worldwide travel as many countries, including the UK, imposed restrictions on arriving and departing travellers (10).Data on travel to and from the UK was obtained from the Office of National Statistics (ONS) International Passenger Survey (IPS).

In 2020, UK residents made 23.8 million visits abroad, which was a 74% decrease from 2019, and there were 11.1 million visits made by overseas residents to the UK, a 73% decrease compared to 2019 (11). In line with falling numbers of travellers arriving in the UK, the number of malaria infections diagnosed in the UK also decreased.

Of the top 20 overall most visited countries by UK residents between 2015 and 2019 from the IPS, India is the only country that is also in the top 20 countries of travel by malaria cases in 2020 (data not available on overall travel to specific countries for 2020).

Table 4 shows the breakdown of malaria cases reported by region of travel and parasite species, and the top 20 countries of travel are shown in table 5. Countries of travel for malaria cases reported in 2020 by count of cases is shown in a map in figure 6. The majority of cases (where travel history was known) continue to be acquired in Africa, with 55% acquired in Western Africa (195 out of 352), 20% in Eastern Africa (72 out of 352) and 11% in Middle Africa (40 out of 352) in 2020. These numbers reflect in general the global prevalence of malaria infection. In 2020, Nigeria accounted for the greatest burden of malaria infection (27% global cases), followed by the Democratic Republic of the Congo (12%) then Uganda (5%) (12).

Table 4. Cases of malaria that travelled abroad from the UK by species and region of travel: 2020 and 2019

| Region of travel | P. falciparum | P. vivax | P. ovale | P. malariae | 2020 total | 2019 total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western Africa | 172 | 1 | 16 | 6 | 195 | 753 |

| Eastern Africa | 63 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 72 | 159 |

| Middle Africa | 35 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 40 | 92 |

| Southern Asia | 1 | 15 | - | - | 16 | 38 |

| Northern Africa | 12 | - | - | - | 12 | 37 |

| Southern Africa | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | 1 |

| South-Eastern Asia | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| Africa unspecified | - | - | - | - | - | 11 |

| South America | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 |

| Not stated | 14 | - | 1 | - | 15 | 25 |

| Total | 298 | 19 | 25 | 10 | 352 | 1,118 |

Table 5. Cases of malaria that travelled abroad from the UK by Plasmodium species and top 20 countries of travel: 2020 and 2019

| Country of travel | P. falciparum | P. vivax | P. ovale | P. malariae | 2020 total | 2019 total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nigeria | 71 | 1 | 10 | 4 | 86 | 413 |

| Sierra Leone | 44 | - | 3 | 2 | 49 | 140 |

| Ghana | 26 | - | 1 | - | 27 | 97 |

| Uganda | 23 | - | 3 | - | 26 | 58 |

| Côte D’Ivoire | 17 | - | 2 | - | 19 | 49 |

| Kenya | 18 | - | 1 | - | 19 | 44 |

| Cameroon | 12 | - | - | 2 | 14 | 37 |

| Congo | 13 | - | 1 | - | 14 | 24 |

| Sudan | 12 | - | - | - | 12 | 36 |

| Tanzania | 7 | - | 1 | - | 8 | 11 |

| India | 1 | 8 | - | - | 9 | 11 |

| Liberia | 5 | - | - | - | 5 | 2 |

| Malawi | 4 | - | - | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| DR Congo | 4 | - | - | - | 4 | 13 |

| Pakistan | - | 4 | - | - | 4 | 18 |

| South Sudan | 2 | - | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Zambia | 4 | - | - | - | 4 | 6 |

| Afghanistan | - | 3 | - | - | 3 | 9 |

| Ethiopia | 3 | - | - | - | 3 | 3 |

| Gabon | 3 | - | - | - | 3 | 2 |

| Other Western Africa | 9 | - | - | - | 9 | 52 |

| Other Eastern Africa | 2 | 1 | - | - | 3 | 27 |

| Other Middle Africa | 3 | 1 | 1 | - | 5 | 16 |

| Southern Africa | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | 1 |

| Africa unspecified | 4 | - | 1 | - | 5 | 11 |

| South America | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 |

| Not stated | 10 | - | - | - | 10 | 25 |

| Other Northern Africa | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| South-eastern Asia | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| Total | 298 | 19 | 25 | 10 | 352 | 1,118 |

Figure 7. Countries of travel for cases of malaria that travelled abroad from the UK by count of cases, 2020

Prevention and treatment

Chemoprophylaxis

Among malaria cases that travelled abroad from the UK, where the history of chemoprophylaxis (antimalarial medication to prevent infection) was known, 208 out of 239 (87%) had not taken chemoprophylaxis. This proportion is similar to recent years.

Of those who had taken some form of chemoprophylaxis (31 cases), all stated which drug they had taken and 29 (94%) had taken a drug that was recommended to UK travellers for their destination by the ACMP. This represents 12% (29 out of 239) of the total cases where chemoprophylaxis information was available. The proportion of the total cases with chemoprophylaxis information that took a drug recommended by the ACMP has remained between 9% and 16% since 2000. Of the 29 cases that took a drug recommended to UK travellers, none reported having taken it regularly. When taken correctly, the agents recommended for prophylaxis against falciparum malaria (atovaquone-proguanil, doxycycline and mefloquine) are more than 90% effective (3). Of note, a malaria fatality occurred in an individual who reported complete adherence to an appropriate prophylaxis regime. Although forgotten missed doses are a possible explanation, prescribers should be aware that no regimen is 100% effective. Bite avoidance and awareness of the need to seek same day medical attention with a fever during or following travel are also important.

Among malaria cases that travelled abroad from the UK, where the history of chemoprophylaxis was known, a higher proportion of females had taken some form of chemoprophylaxis than males: 18% of females (16 out of 87 cases) compared with 10% of males (15 out of 152 cases). The median age of cases who had taken some form of chemoprophylaxis (and had travelled abroad from the UK) was 31 years, compared with an overall median age of 42 years for all cases that had travelled abroad.

These data imply that health messages about the importance of antimalarial chemoprophylaxis still are not reaching groups who are at particular risk of acquiring malaria, or that travellers either are not understanding or are not acting on these messages.

The groups at particular risk of not using chemoprophylaxis include those who are visiting family in their country of origin, particularly those of black African heritage and/or born in Africa. The reasons for this heightened risk have not been investigated systematically, but could include:

- individuals in these groups may not seek or may not be able to access medical advice on malaria prevention before they travel

- they may not receive accurate advice

- they may not adhere to recommendations on chemoprophylaxis

They may not perceive themselves to be at risk (they may have been born or lived in a malaria-endemic area for many years), or they may have concerns about the cost of drugs. The burden of falciparum malaria in particular falls heavily on those of black African heritage, and this group is important to target for pre-travel advice.

Taking fever seriously on return from a malaria risk area

P. falciparum can progress to severe and life-threatening illness, including cerebral malaria, if it is not diagnosed and treated promptly. Travellers returning from malaria risk areas should seek urgent medical advice, including a same-day result malaria blood test, for any symptoms, especially fever, during their trip or in the year following their return home.

Treatment guidelines and algorithms for clinicians are available from the British Infection Association.

Reliability of malaria diagnostic tests

In the UK, malaria is diagnosed by microscopic examination of thick and thin blood films and by rapid immunochromatographic diagnostic tests (RDTs) which detect circulating parasite antigens. RDTs have satisfactory diagnostic accuracy in most clinical situations but should not be relied on alone (13). The most commonly used RDTs detect circulating P. falciparum histidine-rich proteins (HRP2 and HRP3). However, deletions of pfhrp2 and pfhrp3 genes occur in some P. falciparum populations, particularly in regions of the Amazon River basin in South America, and in East Africa, reducing the sensitivity of some RDTs (14). Among 113 UK P. falciparum samples from East Africa in 2018, 23 (20.4%) showed evidence of deletion of at least one of these 2 genes (15). The MRL has characterised in detail a further 5 cases where a false-negative HRP2 RDT result was obtained by the sending laboratory, prior to confirmation of P. falciparum infection by microscopy (16).

The implications of pfhrp2 and pfhrp3 gene deletions for RDT use is under investigation by the WHO, and further guidance is expected, but these tests remain an important additional diagnostic tool for imported malaria in the UK. In the UK, blood film microscopy is of a high standard and should be performed on all suspected malaria cases, whether or not an RDT is used. The British Society for Haematology Guidelines for the laboratory diagnosis of malaria, revised in May 2022 (13), provide the necessary guidance.

Antimalarial treatment failure in UK patients

In 2017 the MRL reported 4 cases of treatment failure among UK patients receiving artemether-lumefantrine (Riamet™) for P. falciparum infections (17). Since that time a further 21 suspected cases have been reported and are under investigation by the MRL. Mutations in the pfk13 gene, associated with reduced parasite susceptibility to artemisinins in South-Eastern Asia, were not found except in a single case of P. falciparum imported from Cambodia.

Treatment failures represent a tiny proportion of notified P. falciparum cases in the UK - in 2019, 8 suspected P. falciparum post-treatment recurrences were identified by passive surveillance at the MRL, out of a total of 1,475 reported cases (0.05%). Riamet™ remains highly effective and recommended for treatment of UK cases. However, clinicians should be aware of this issue, and of the potential need for prolonged or alternative treatment in rare cases of parasite recrudescence.

Prevention is key

Malaria, an almost completely preventable but potentially fatal disease, remains an important issue for UK travellers. Failure to take chemoprophylaxis correctly is associated with the majority of cases of malaria in UK residents travelling to malaria-risk areas. The number of cases in those going on holiday is small, but associated with greater mortality (8). Those of African or Asian ethnicity who are non-UK born and who travel to visit friends and relatives are at increased risk of malaria, as well as a number of other infections (18). Older patients are at particular risk of dying from malaria if they acquire the infection. Those providing advice should engage with these population groups wherever possible, including using potential opportunities to talk about future travel plans outside a specific travel health consultation, such as during new patient checks or childhood immunisation appointments (19).

The ACMP guidelines and National Travel Health Network and Centre are available to assist clinicians in helping travellers to make rational decisions about protection against malaria.

Useful resources for travellers, including translated leaflets, are also available at Malaria: health advice for travellers.

References

1. Cathcart SJ, Lawrence J, Grant A, Quinn D, Whitty CJ, Jones J and others. ‘Estimating unreported malaria cases in England: a capture-recapture study’ Epidemiology and Infection 2010: volume 138, issue 7, pages 1,052 to 1,058.

2. UKHSA. ‘Imported malaria in the UK: statistics’ (accessed 27 October 2022).

3. Chiodini PL, Patel D, Whitty CJM and Lalloo DG. ‘Guidelines for malaria prevention in travellers from the United Kingdom, 2021’ UKHSA September 2022.

4. UKHSA. ‘Notifications of infectious diseases (NOIDs)’ (accessed 27 October 2022).

5. UKHSA. ‘Notified diseases: 2020 annual figures’ (accessed 27 October 2022).

6. UN Statistics Division. ‘Composition of macro geographical (continental) regions, geographical sub-regions, and selected economic and other groupings’’ (accessed 27 October 2022).

7. World Health Organization (WHO). ‘Malaria factsheet’ (accessed 15 December 2022).

8. Checkley AM, Smith A, Smith V, Blaze M, Bradley D, Chiodini PL and others. ‘Risk factors for mortality from imported falciparum malaria in the UK over 20 years: an observational study’ British Medical Journal 27 March 2012: volume 344, page e2116.

9. Broderick C, Nadjm B, Smith V, Blaze M, Checkley A, Chiodini PL, Whitty CJM. ‘Clinical, geographical, and temporal risk factors associated with presentation and outcome of vivax malaria imported into the UK over 27 years: observational study’ British Medical Journal 16 April 2015: volume 350, page h1703.

10. Office for National Statistics (ONS). ‘Coronavirus and the impact on the UK travel and tourism industry’ (accessed 27 October 2022).

11. ONS. ‘Overseas travel and tourism: 2020’ (accessed 27 October 2022).

12. WHO. ‘World malaria report 2020’ (accessed 27 October 2022).

13. Rogers CL, Bain BJ, Garg M, Fernandes S, Mooney C, Chiodini PL, British Society for Haematology. ‘British Society for Haematology guidelines for the laboratory diagnosis of malaria’ British Journal of Haematology May 2022: volume 197, issue 3, pages 271 to 282.

14. ML Gatton and others. ‘Impact of Plasmodium falciparum gene deletions on malaria rapid diagnostic test performance’’ Malaria Journal 4 November 2020: volume 19, issue 1, page 392.

15. Grignard L, Nolder D, Sepulveda N, Berhane A, Mihreteab S, Kaaya R and others. ‘A novel multiplex qPCR assay for detection of Plasmodium falciparum with histidine-rich protein 2 and 3 (pfhdpr2 and pfhrp3) deletions in polylclonal infections’ EBioMedicine 2020: volume 55, page 102,757.

16. Nolder D, Stewart L, Tucker J, Ibrahim A, Gray A, Corrah T and others. ‘Failure of rapid diagnostic tests in Plasmodium falciparum malaria cases among travelers to the UK and Ireland: Identification and characterisation of the parasites’ International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2021: volume 108, pages 137 to 144.

17. Sutherland CJ, Lansdell P, Sanders M, Muwanguzi J, van Schalkwyk DA, Kaur H and others. 2017. ‘pfk13-independent treatment failure in 4 imported cases of Plasmodium falciparum malaria treated with artemether-lumefantrine in the UK’ Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2017: volume 61, pages e02382 to e02316.

18. Wagner KS, Lawrence J, Anderson L, Yin Z, Delpech V, Chiodini PL and others. ‘Migrant health and infectious diseases in the UK: findings from the last 10 years of surveillance’ Journal of Public Health 2014: volume 36, issue 1, pages 28 to 35.

19. Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID). ‘Migrant health guide’ (accessed 27 October 2022).