Country policy and information note: Palestinians in Lebanon, Lebanon, March 2024

Updated 6 March 2024

Version 2.0, March 2024

Executive summary

In general, the treatment faced by Palestinians by non-state actors – or by ‘registered’ and ‘non-registered’ Palestinians by state actors – does not, by its nature or repetition, even when taken cumulatively, amount to a real risk of persecution and/or serious harm. The onus is on the person to demonstrate otherwise.

‘Registered’ Palestinians are likely to be excluded from the Refugee Convention by Article 1D, as persons eligible for UNRWA assistance.

However, state restrictions on the fundamental rights of ‘non-ID’ and Palestinians from Syria (PRS), taken cumulatively, are likely to qualify these persons for asylum. While PRS might be considered as excluded from the Refugee Convention under Article 1D, this is likely no longer the case given that UNRWA support has likely ceased to be available for reasons beyond the person’s volition due to their inability to return to Lebanon, having left, and their vulnerability to deportation to Syria.

Lebanon’s stateless Palestinians began arriving in 1948 from what is now Israel, and 2011 from Syria. The now-estimated 183,255 to 250,000 mostly Sunni Muslims, reside across Lebanon in 12 UNRWA camps, nearby gatherings, and other localities. Lebanese laws deny citizenship to most Palestinians, therefore relatively few have naturalised.

The state’s laws restrict Palestinians’ access to many areas of daily life to varying degrees, depending on their ‘categories’. This also determines entitlement to UNRWA services, which most Palestinians rely on for basic needs. ‘Non-ID’ Palestinians and PRS suffer disproportionately from employment restrictions, compounded by their relatively lacking freedom of movement and access to UNRWA services.

The Country Guidance cases, KK, IH, HE, and MM and FH, found that Lebanon’s discriminatory denial of Palestinians’ third category rights and its refugee camp conditions do not amount to persecution and/or serious harm. MM and FH also attributed Lebanon’s differential treatment of Palestinians to statelessness, not race.

Violent clashes periodically occur between armed factions operating within refugee camps, including Hezbollah which controls parts of Lebanon over the state, occasionally injuring Palestinians, or disrupting their access to UNRWA services.

In the case of H.A. v the UK, the European Court of Human Rights held that absent prior involvement with, and previous violent targeting by, armed factions, any previous refusal of recruitment attempts by extremist armed factions would not give rise to a risk of treatment in breach of Article 3 of the ECHR.

‘Non-ID’ Palestinians and PRS with a well-founded fear of persecution from the state would not be able to seek protection or relocate to escape that risk.

While a well-founded fear of persecution from non-state actors can unlikely be established, where a well-founded fear of persecution from Hezbollah is established, in general, neither protection nor relocation will be viable means to escape that risk.

Where a claim is refused, it is unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’.

Assessment

About the assessment

This section considers the evidence relevant to this note – that is information in the country information, refugee/human rights laws and policies, and applicable caselaw – and provides an assessment of whether, in general:

-

a person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution/serious harm by state or non-state actors because they are Palestinian

-

that the general humanitarian situation is so severe that there are substantial grounds for believing that there is a real risk of serious harm because conditions amount to inhuman or degrading treatment as within paragraphs 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules/Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)

-

a person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies)

-

a person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory

-

a grant of asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave is likely, and

-

if a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

Decision makers must, however, still consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts.

Points to note

Palestinian refugees in Lebanon who were receiving protection and/or assistance from the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) are excluded from the protection of the Refugee Convention under Article 1D unless such protection has ceased for any reason.

Exclusion under Article 1D of the Refugee Convention does not automatically exclude a person from humanitarian protection. Whether a person is entitled to humanitarian protection will depend on the facts of the case. For general guidance, see the Asylum Instruction on Humanitarian Protection.

This note must be considered alongside the Asylum Instruction on Article 1D of the Refugee Convention: Palestinian refugees assisted by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), which provides details on how to consider asylum claims made by stateless Palestinians whose habitual place of residence is the Occupied Palestinian Territories, Jordan, Lebanon, or Syria (see also, Exclusion).

Where a person does not qualify for asylum or humanitarian protection, and is not excluded from the Refugee Convention under Article 1D, it is open to them to apply for leave to remain as a stateless person. This cannot be done at the same time as the asylum claim is being pursued (see the Stateless guidance).

1. Material facts, credibility and other checks/referrals

1.1 Credibility

1.1.1 For information on assessing credibility, see the instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

1.1.2 Decision makers must also check if there has been a previous application for a UK visa or another form of leave. Asylum applications matched to visas should be investigated prior to the asylum interview (see the Asylum Instruction on Visa Matches, Asylum Claims from UK Visa Applicants).

1.1.3 In cases where there are doubts surrounding a person’s claimed place of origin, decision makers should also consider language analysis testing, where available (see the Asylum Instruction on Language Analysis).

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

1.1.4 The information in this section has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use only.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

1.2 Exclusion

1.2.1 Decision makers must consider whether there are serious reasons for considering whether one (or more) of the exclusion clauses is applicable. Each case must be considered on its individual facts and merits.

a. Applicability of Article 1D of the Refugee Convention

1.2.2 Article 1D of the Refugee Convention is one of the exclusion clauses in the Refugee Convention. It excludes persons receiving protection or assistance from organs or agencies of the United Nations (other than the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)) from the Refugee Convention, but its overall purpose is to ensure the continuing protection of Palestinian refugees until their position is settled in accordance with relevant United Nations General Assembly resolutions.

1.2.3 Palestinian refugees in Lebanon who were previously assisted by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) and continue to be eligible for such assistance but who seek asylum outside the area of UNRWA operation are excluded from the scope of the Refugee Convention unless they can show that UNRWA assistance or protection has ceased for any reason, which includes where a person ceases to receive protection or assistance beyond their control or independent of their volition.

1.2.4 A Palestinian eligible for UNRWA protection or assistance and previously registered with UNRWA, or (though not registered) in receipt of UNRWA protection or assistance, is not entitled to Refugee Convention refugee status simply by leaving the UNRWA areas of operation and claiming asylum elsewhere.

1.2.5 Situations where UNRWA protection or assistance may cease beyond the person’s control or independent of their volition may include the following circumstances:

-

where there is a threat to life, physical integrity or security or freedom, or other serious protection related reasons

-

situations such as armed conflict or other situations of serious violence, unrest and insecurity, or events seriously disturbing public order

-

more individualised threats or protection risks such as sexual and/or gender-based violence, human trafficking and exploitation, torture, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, severe discrimination

-

arbitrary arrest or detention

1.2.6 Additionally, practical legal and/or safety barriers to accessing UNRWA assistance may mean that UNRWA assistance is in practice no longer available and may include:

-

being unable to access UNRWA assistance because of long-term border closures, road blocks or closed transport routes

-

absence of documentation to travel to, or transit, or to re-enter and reside, or where the authorities in the receiving country refuse their re-admission or the renewal of their travel documents

-

serious dangers such as minefields, factional fighting, shifting war fronts, banditry or a real risk of other forms of violence or exploitation

1.2.7 Palestinian ‘refugees’ resident in Lebanon who were not receiving or eligible to receive protection or assistance from UNRWA are not excluded under Article 1D. These cases should be considered on their merits under the Refugee Convention, unless there are serious reasons for considering whether one (or more) of the other exclusion clauses is applicable. Each case must be considered on its individual facts and merits.

1.2.8 Further guidance on handling Palestinians assisted by UNRWA is set out in the Asylum Instruction on Article 1D of the Refugee Convention: Palestinian refugees assisted by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) (see also Other points to note).

b. Exclusion under Article 1F of the Refugee Convention

1.2.9 There are a number of armed groups operating in Lebanon, including (but not limited to) the military wings of Palestinian groups such as Hamas and the Palestinian Liberation Organisation. Some of these groups may be involved in terrorist activities (several are proscribed under the UK Terrorism Act 2000, see Proscribed terrorist groups or organisations) or are responsible for serious human rights abuses in Lebanon as well as neighbouring countries and areas including Syria, the Occupied Palestinian Territories and Israel (see Treatment by non-state actors).

1.2.10 If there are serious reasons for considering that the person has been involved with these groups then decision makers must consider whether any of the exclusion clauses under Article 1F are applicable.

1.2.11 If the person is excluded from the Refugee Convention under Article 1F, they will also be excluded from a grant of humanitarian protection (which has a wider range of exclusions than refugee status).

1.2.12 For guidance on exclusion and restricted leave, see the Asylum Instruction on Exclusion under Articles 1F and 33(2) of the Refugee Convention, Humanitarian Protection and the instruction on Restricted Leave.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information in this section has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use only.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

2. Convention reason(s)

2.1.1 Nationality. Most Palestinians are stateless i.e. without nationality.

2.1.2 Establishing a convention reason is not sufficient to be recognised as a refugee. The question is whether the person has a well-founded fear of persecution on account of an actual or imputed Refugee Convention reason.

2.1.3 For further guidance on the 5 Refugee Convention grounds see the Asylum Instruction, Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

3. Risk

3.1 General approach

3.1.1 In general, Palestinian refugees in Lebanon who are registered with UNRWA and/or the Lebanese authorities are not at risk of treatment amounting to persecution or serious harm by the state.

3.1.2 In general, Palestinian Refugees from Syria (PRS) and ‘Non-ID’ Palestinians are likely at real risk of treatment amounting to persecution or serious harm by the state.

3.1.3 Palestinian residents in Lebanon are categorised into four ‘groups’, determined by their registration (or eligibility for registration) with UNRWA and the Lebanese authorities, when they entered Lebanon and from which country they arrived from. Palestinian refugees face legal obstacles which have resulted in their social and economic marginalisation. However, the general nature and degree of treatment varies between the different Palestinian ‘groups’. See below and Palestinian population, legal status and ‘categories’ for more information on the different classifications of Palestinian groups.

3.2 Risk from the state to UNRWA (and government) registered Palestinian refugees (PRL)

3.2.1 Palestinian refugees resident in Lebanon and registered with UNRWA, or eligible to be, who comprise the majority of Palestinians in Lebanon, fall within the scope of Article 1D of the Refugee Convention.

3.2.2 In general such persons are not subject to treatment that is by its nature and/or repetition, even taken cumulatively, likely amount to persecution or serious harm. They are likely to be excluded from the Refugee Convention under Article 1D as persons eligible to receive assistance from UNRWA which has not ceased to be available for any reason.

3.2.3 However, each case will need to be considered on its merits. Some persons may be able to demonstrate that they face an individualised risk where UNRWA assistance ceases to be available. For more information see ‘Registered’ Palestinians.

3.3 Risk from the state to Non-UNRWA-registered Palestinian refugees

3.3.1 Palestinian refugees neither registered with UNRWA nor eligible to be, but who are registered with the Lebanese government do not fall within the scope of Article 1D of the Refugee Convention (although they may have, at some stage, received some assistance from UNRWA).

3.3.2 In general, while such persons face some restrictions in their access to services, employment and freedom of movement, this is not likely by its nature or repetition, even taken cumulatively, to amount to persecution or serious harm. The onus is on the person to demonstrate otherwise. For more information see ‘Non-registered’ Palestinians.

3.4 Risk from the state to Non-ID Palestinian refugees

3.4.1 The estimated 3,000 - 5,000 non-ID Palestinians do not fall within the scope of Article 1D of the Refugee Convention since they are not eligible to be registered with or receive assistance from UNRWA (although in practice they may have received some assistance from UNRWA).

3.4.2 In general, such persons are likely to face discrimination in accessing services and documentation, and restrictions on their employment rights, ability to purchase property and to move freely into and within Lebanon. These limits on fundamental rights, taken cumulatively, are likely by their nature and repetition to amount to persecution or serious harm. For more information see ‘Non-ID’ Palestinians.

3.5 Risk from the state to Palestinians from Syria (PRS)

3.5.1 Palestinian refugees registered with UNRWA in Syria (PRS) who have fled to Lebanon, estimated in 2023 to number approximately 32,000, potentially fall within the scope of Article 1D of the Refugee Convention since they have previously received assistance from UNRWA.

3.5.2 While PRS are likely to receive some assistance from UNRWA, it is generally more limited, and they may face more severe discrimination compared with most other Palestinian refugees. Significantly, PRS face additional restrictions on their movement within and into Lebanon, and may be vulnerable to deportation to Syria. Due to PRS’ likely inability to return to Lebanon having left, UNRWA support in practice ceases to be available for reasons beyond the person’s control or volition. Therefore, such persons are likely to no longer be excluded under Article 1D of the Refugee Convention.

3.5.3 Since PRS have already been recognised as refugees by the UN, they are likely to qualify for asylum.

3.5.4 However, all cases must be considered on their facts, with the onus on the person to demonstrate their status in Lebanon and the risk they face. For more information see Palestinians from Syria.

3.6 Risk from non-state actors

3.6.1 While Palestinian refugees are vulnerable to discrimination by non-state actors, which has included blocking access to basic goods such as food and fuel, in general this treatment is not sufficiently serious by its nature and/or repetition, even when taken cumulatively, to amount to persecution or serious harm.

3.6.2 A number of non-state groups operate in Lebanon. Most powerful is Hezbollah, an Iran-backed armed and political Shia group which maintains a vast political and military network in Lebanon. Hezbollah has effective control over southern Lebanon, southern Beirut, and parts of Beqaa. The group also maintains significant influence of Lebanon’s international airport in Beirut. The country evidence does not indicate that Hezbollah generally targets or discriminates against Palestinians and, while Hezbollah is reported to have used intimidation, harassment, unlawful detention, and violence against its Shia critics and opponents, sources indicate that it remains tolerant of criticism from non-Shias (most Palestinians are Sunni). However, should a person be of adverse interest to Hezbollah, it has the capability to locate and detain them within Lebanon (see Presence of Hezbollah (aka Hizballah/Hizbullah)).

3.6.3 In addition, a number of other armed groups exist, including Palestinian groups which primarily operate and govern most of the UNRWA refugee camps. Palestinian factions and some non-Palestinian groups sometimes enter into violent clashes with one another inside the refugee camps. The groups’ critics and opponents have faced harassment, threats, abuse and arbitrary detention, and Palestinian civilians may be caught in the cross-fire of factional disputes. However, information on abuses by these armed militias, or other non-state armed groups, indicates that they are not generally aimed at Palestinian civilians (see Presence of Other armed groups and Refugee camps).

3.6.4 The country evidence does not indicate that Hezbollah (which draws a predominantly Shia support base) and other armed groups generally forcibly recruit Palestinians. Some sources indicate that Palestinian children in refugee camps were recruited and used as child soldiers during 2021 and 2022, however more recent information, including the scale and extent of such recruitment, could not be found in the sources consulted (see Vulnerable groups, Presence of Hezbollah (aka Hizballah/Hizbullah), and Presence of Other armed groups).

3.6.5 In the case of H.A. v The United Kingdom (Application no. 30919/20), heard on 14 November 2023, promulgated on 5 December 2023, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) considered whether the refusal of previous recruitment attempts by extremist armed factions gave rise to a risk of treatment in breach of Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). The ECtHR held that absent particular individual circumstances, such as prior involvement with an extremist group and having been subjected to previous targeted acts of violence, in general, the refusal of recruitment attempts by extremist armed factions would not give rise to a risk of treatment in breach of Article 3 of the ECHR.

3.6.6 Sources indicate that long-standing anti-Palestinian societal attitudes exist in Lebanon, exacerbated by the arrival since 2011 of those displaced by the Syrian war. However, the associated societal discrimination is not sufficiently serious by its nature and/or repetition, even when taken cumulatively, to amount to persecution or serious harm. Furthermore, the mobilisation in recent years of wider Lebanese society in solidarity with Palestinian protests against discriminatory state policies, indicates a co-existence of sympathetic sentiment towards Palestinians, part of Lebanon’s socio-economic, cultural, and political tapestry for over 70 years (see Societal attitudes).

3.6.7 For further guidance on assessing risk, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

3.7 Humanitarian situation in refugee camps

3.7.1 While conditions in refugee camps are reportedly poor, they do not amount to inhuman or degrading treatment as per paragraphs 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules/Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

3.7.2 For more information see Overview of situation for Palestinians and Country Guidance and Refugee Camps.

3.7.3 For guidance on Humanitarian Protection see the Asylum Instruction, Humanitarian Protection.

3.8 Situation for Palestinians in Lebanon overview and Country Guidance

3.8.1 There are estimated to be between 183,255 to 250,000 Palestinians residing in Lebanon. Most Palestinians in Lebanon have never been afforded entitlement under the law to Lebanese citizenship and therefore remain stateless. This includes many who arrived from what is now Israel as early as 1948 during the Arab-Israeli war, and their descendants. Lebanon, neither a signatory to the 1954 and 1961 stateless conventions, nor the 1951 Refugee Convention, treats even its long-standing Palestinian residents as refugees and/or foreigners, despite them lacking the nationality of another country (see Background and recent history, Lebanese citizenship law, Status and statelessness).

3.8.2 Approximately 45% of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon reside in 12 UNRWA-leased refugee camps, where living conditions are generally poor and overcrowded. Governance and security within the camps is enforced by ‘popular committees’ and ‘security committees’ belonging to Palestinian groups and factions, including the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), Hamas, and Fatah. Although most camps are generally stable, violent clashes have occurred in 2022 and 2023, particularly in Ein el-Hilweh, the largest of the camps (estimated to house upwards of 63,000 registered refugees) and in the Mieh Mieh camp. While the camps are generally outside the control or reach of the Lebanese authorities, movement into and out of some of the camps, particularly those in southern Lebanon, is regulated by them. Palestinian refugees not residing in the designated camps, reside instead either in adjacent gatherings or neighbourhoods across national territories (see ‘Categories’ of Palestinians, Demography, Refugee camps).

3.8.3 Lebanese law does not specifically target Palestinians. However, the impact of the authorities restricting their access to state services such as healthcare and education, barring them from employment in multiple fields, and from acquiring new property and land, has led to Palestinians facing socio-economic marginalisation: experiencing high levels of unemployment and poverty, and poor infrastructure and housing conditions generally. This is, however, partially offset by the support services provided by UNRWA, which Palestinians largely depend upon. In recent years, Lebanon’s severe economic crisis (which saw rampant inflation while the Lebanese pound lost 95% of its value) has exacerbated the Palestinian community’s poverty levels and reliance on UNRWA for basic services. Simultaneously, forced closures of UNRWA installations, often due to inter-factional violence and protests linked to the socio-economic situation, have disrupted access to these services, while UNRWA’s own financial difficulties threaten future provision (see Daily life, Security in refugee camps, Other armed groups).

3.8.4 Available evidence indicates that during 2022 and 2023 a small number of Palestinians were arbitrarily arrested and detained, with those from Syria who entered Lebanon illegally and who are without legal status the most vulnerable to arrest and deportation to Syria. The country information does not, however, support that arrests of Palestinians with ID documents and residency in Lebanon are common or likely (see Treatment by state actors, Freedom of movement).

3.8.5 In the case of KK, IH, HE (Palestinians – Lebanon – camps) Lebanon CG [2004] UKIAT 00293, heard 24 May 2004, promulgated 29 October 2004, the Immigration Appeal Tribunal considered whether poor living conditions in the refugee camps in Lebanon amounted to a breach of Article 3 of the ECHR and if there was a real risk of persecution under the Refugee Convention. The Tribunal summarised the country evidence as described by UNRWA:

‘… Palestinian refugees in Lebanon… do not have social and civil rights and have a very limited access to the government’s public health or educational facilities, and no access to public or social services. The majority rely entirely on UNRWA as the sole provider of education, health and relief and social services. They are considered as foreigners and prohibited by law from working in some seventy-two trades and professions which has led to high levels of unemployment among the refugee population. It seems that popular committees in the camps representing the refugees regularly discuss these problems with the Lebanese government or with the UNRWA officials. As we say, UNRWA provides services and administers its own installations and has a camp services office in each camp which residents can visit to update records or raise issues about services with the camp services officer who will refer petitions etc. to the UNRWA administration in relevant areas. It is said that socio-economic conditions in the camps are generally poor. There is a high population density and there are cramped living conditions and an inadequate basic infrastructure as regards matters such as roads and sewers. As we have noted above, some two-thirds of registered refugees live in and around cities and towns.’ (para 83)

3.8.6 The Tribunal went on to find that ‘to the extent that there is a discriminatory denial of third category rights in Lebanon for the Palestinians, this does not amount to persecution under the Refugee Convention or breach of protected human rights under Article 3 of the ECHR [European Convention on Human Rights].’ The Tribunal also held that conditions in camps at that time did not amount to a breach of Article 3 of the ECHR (para 106).

3.8.7 In the country guidance case of MM and FH (Stateless Palestinians, KK, IH, HE reaffirmed), heard 29 June 2007 and promulgated on 4 March 2008, the Asylum and Immigration Tribunal (AIT) observed that it had ‘not been presented with any new or significant evidence that should cast doubt on the decision reached by the Tribunal in KK.’ (para 126)

3.8.8 It went on to find that:

i) ‘The differential treatment of stateless Palestinians by the Lebanese authorities and the conditions in the camps does not reach the threshold to establish either persecution under the Geneva Convention, or serious harm under paragraph 339C of the Immigration Rules, or a breach of Articles 3 or 8 under the ECHR.

ii) ‘The differential treatment of Palestinians by the Lebanese authorities is not by reason of race but arises from their statelessness.

iii) ‘The decision in KK, IH, HE (Palestinians-Lebanon-camps) Jordan CG [2004] UKIAT 00293, is reaffirmed.’ (Headnote)

3.8.9 The country situation since the promulgation of MM and FH in 2008 has not substantively changed. The available evidence considered in this note (see Bibliography for full list of sources) does not establish that there has been a significant and cogent change in the treatment of Palestinians by the government or in the conditions in refugee camps generally. There are not, therefore, ‘very strong grounds supported by cogent evidence’ to justify a departure from the Tribunal’s findings in MM and FH.

3.8.10 For further guidance on assessing risk, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

4. Protection

4.1.1 Where the person has a well-founded fear of persecution from the state they will not, in general, be able to obtain protection from the authorities.

4.1.2 Where the person has a well-founded fear of persecution from non-state actors, including ‘rogue’ state actors, decision makers must assess whether the state can provide effective protection.

4.1.3 The availability of protection will depend on who or which group the person is of interest to. Persons fearing Hezbollah are unlikely to be able to obtain effective protection from the state, UNRWA, or Palestinian groups. However, in some cases, persons who fear other non-state armed groups, including Palestinian factions within camps and gatherings, may be able to obtain effective protection from other Palestinian groups operating in the camps depending on their circumstances. While the state may be able to provide effective protection in some parts of Lebanon, it is unlikely to be willing to do so in practice (see Treatment by non-state actors and Protection).

4.1.4 However, each case must be considered on its facts, with the onus on the person to demonstrate that they are unable to obtain effective protection.

4.1.5 For further guidance on assessing state protection, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

5. Internal relocation

5.1.1 Where the person has a well-founded fear of persecution or serious harm from the state, they are unlikely to be able to relocate to escape that risk.

5.1.2 Where the person has a well-founded fear of persecution or serious harm from a non-state actor, internal relocation may be reasonable, depending on:

-

the person’s legal status in Lebanon

-

the non-state group, the nature of its interest in, and its capacity to pursue, the person

-

the person’s individual circumstances

5.1.3 Palestinians face restrictions in their freedom of movement, with entry and exit controls operated by the government which may be tightened during periods of heightened security. The government maintains checkpoints around Palestinian refugee camps and in other restricted areas, while Hezbollah has control in Shia-dominated areas. Palestinians without legal status and documentation risk arrest and detention at checkpoints, and are unlikely to be able to relocate. Palestinians who have legal status in Lebanon are generally able to move within the country and the Lebanese General Directorate of General Security (GDGS) has made provision for issuing travel documents to both ‘registered’ and ‘non-registered’ Palestinians (see Documents and Freedom of movement).

5.1.4 While the onus is on the person to establish a well-founded fear of persecution or real risk of serious harm, decision makers must demonstrate that internal relocation is reasonable (or not unduly harsh) having regard to the individual circumstances of the person.

5.1.5 For further guidance on considering internal relocation and factors to be taken into account, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

6. Certification

6.1.1 Where a claim is refused, it is unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

6.1.2 For further guidance on certification, see Certification of Protection and Human Rights claims under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 (clearly unfounded claims).

Country information

About the country information

This contains publicly available or disclosable country of origin information (COI) which has been gathered, collated and analysed in line with the research methodology. It provides the evidence base for the assessment.

The structure and content of this section follow a terms of reference which sets out the general and specific topics relevant to the scope of this note.

This document is intended to be comprehensive but not exhaustive. If a particular event, person or organisation is not mentioned this does not mean that the event did or did not take place or that the person or organisation does or does not exist.

Decision makers must use relevant COI as the evidential basis for decisions.

Section updated: 4 March 2024

7. Palestinian population, legal status and ‘categories’

7.1 Background and recent history

7.1.1 In May 2019, Amnesty International (AI) published a report entitled ‘Seventy+ Years of Suffocation’ which stated: ‘During the 1948 Arab-Israeli war hundreds of thousands of Palestinians fled or were expelled and displaced from their homes in what is now Israel. A large group of them sought refuge in neighboring Lebanon. Seven decades on, Palestinian refugees and their descendants, who are also considered refugees, still live in official and informal camps across the five governorates of the country.’[footnote 1]

7.1.2 For more information on the camps, including their locations and life inside the camps, see Demography, Daily Life and Refugee camps.

7.1.3 In May 2018, Medical Aid for Palestinians (MAP), ‘a non-political, non-religious, non-sectarian humanitarian organisation’[footnote 2] which ‘works in partnership with Palestinian communities to uphold their rights to health and dignity’,[footnote 3] published a report entitled ‘Health in Exile: Barriers to the Health and Dignity of Palestinian Refugees in Lebanon’, citing various sources, which stated:

‘Around 100,000 Palestinians originally fled to Lebanon at the time of the Nakba [‘“catastrophe” in Arabic, refers to the mass displacement and dispossession of Palestinians during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war’[footnote 4]]… They were joined by later waves of refugees following the 1967 war, and the 1970 fighting in Jordan… From 1948 to today, the lives of Palestinians in Lebanon have been blighted by repeated conflict, from the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990), including massacres in the camps of Tel al Zaatar (1976) and Sabra and Shatila (1982) and the brutal “War of the Camps” (1984), to the Nahr al Bared conflict (2007). More recently, the ongoing conflict in neighbouring Syria has forced Palestinian refugees to flee across the border in search of safety, with an estimated 32,000 remaining in Lebanon (as of the end of 2016).’[footnote 5]

7.2 Lebanese citizenship law

7.2.1 Lebanese citizenship law is set out in Decree No 15 on Lebanese Nationality, published on 19 January 1925, amended by regulations in 1934 and 1939, and by law in 1960[footnote 6].

7.2.2 The Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) published a ‘Country Information Report: Lebanon’ on 26 June 2023 which stated:

‘Article 1 of the Nationality Law (1925) states that a person is considered Lebanese if they were born of a Lebanese father; or were born in Lebanon and did not acquire a foreign nationality upon birth by affiliation; or were born in Lebanon of unknown parents or parents of unknown nationality… A child born of a foreign father can obtain a birth certificate, however the birth will be registered in the DGPS’ [Directorate General for Personal Status] Foreigner Events Department, even if the mother is Lebanese. Lebanese women cannot pass on citizenship by descent.’[footnote 7]

7.2.3 On 26 January 2020, The National, a journalistic publication which ‘reaches an influential, English-speaking audience to deliver the latest in news, business, arts, culture, lifestyle and sports, while leading the region [the Middle East] in analytical content and commentary’[footnote 8], published an article entitled ‘A matter of identity: The families who are affected by Lebanon’s nationality law’ which stated:

‘Lebanon’s French-Mandate-era nationality law dates back to 1925 and has only been changed once, in the 1960s, to allow women married to foreigners to keep their citizenship, as it was previously stripped from them. The current law bars women from passing on citizenship to their children and husband, if he is not Lebanese. Meanwhile, men can grant full citizenship to their foreign spouses after one year of marriage and their children are automatically considered Lebanese.

‘… In 1990, the Lebanese Constitution was amended to make sure “there will be no … settlement of non-Lebanese in Lebanon”. Palestinians made up the overwhelming majority of refugees in the country at the time. To this day, all the major political parties, even outspoken defenders of the Palestinian cause such as Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah, agree on the issue of non-resettlement unanimously. In a TV appearance in May [2020], Nasrallah referred to naturalisation as a “danger” and a “threat”. This idea was echoed in a tweet last year [2019] by Lebanon’s former Foreign Minister Gebran Bassil, who said opposing the naturalisation of Syrians and Palestinians in Lebanon was necessary to “defend the existence of Lebanon and to defend the rights of the Palestinian and Syrian people” against a set of “conspiracies aimed at moving from their home countries and resettling them in a land that is not theirs”.’[footnote 9]

7.2.4 The Forced Migration Review (FMR) of the Refugee Studies Centre at the Oxford Department of International Development, the objective of which is ‘to establish a link through which practitioners, researchers and policy makers can communicate and benefit from each other’s practical experience and research results’,[footnote 10] published an undated article entitled ‘Stateless Palestinians’ which stated: ‘Procedures to allow non-residents to apply for naturalisation in Lebanon… do not apply to stateless Palestinians.’[footnote 11]

7.2.5 In June 2020, the Danish Immigration Service (DIS) published a report entitled ‘Palestinian Refugees Access to registration and UNRWA services, documents, and entry to Jordan’, with an appendix attached comprising the minutes of a DIS/UNRWA meeting held at UNRWA’s Amman headquarters on 3 March 2020, which stated: ‘There are Palestinians with Lebanese citizenship… Almost all of them were Christian Palestinians, but a considerable number were Sunni Palestinians and even some Shiites that were registered with UNRWA [United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East] coming from border towns.’[footnote 12]

7.2.6 In June 2020, Oxford University Press published the second edition of a book written by legal scholars Dr. Francesca Albanese (currently the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian Territory[footnote 13]) and Professor Lex Takkenberg, entitled ‘Palestinian Refugees in International Law’, citing various sources, which stated: ‘Besides those Palestinians – mainly wealthy Christians and others with family connections – who acquired Lebanese citizenship between 1952 and 1958, the vast majority of Palestinians in Lebanon remain without citizenship, and in a precarious situation.’[footnote 14]

7.2.7 On 17 May 2023, the Higher Presidential Committee of Church Affairs in Palestine (HCC), the first dedicated committee, established under a presidential decree on 24 May 2012, to oversee legal, property, and institutional matters concerning churches and Christian places of worship[footnote 15], published an article entitled ‘The Nakba of the Birthplace of Christianity: The Case of Palestinian Christian Refugees in Lebanon’ which stated: ‘With a significant part of Lebanese Christians having immigrated under the Ottoman and French occupations, some members of the Christian parties in control of the country agreed to provide several Palestinian Christians with citizenship after 1948. Between 1949 and 1952, around 31,000 Palestinian Christians were granted Lebanese citizenship.’[footnote 16]

7.2.8 On 19 May 2023, the Congressional Research Service (CRS), ‘a research entity… that provides policy and legal analysis to committees and members of both chambers of the United States Congress’,[footnote 17] published a report entitled ‘Lebanon’, citing various sources, which stated that: ‘Like Syrian refugees, Palestinian refugees and their Lebanese-born children cannot obtain Lebanese citizenship, even though many are the third or fourth generation to be born inside Lebanon…’[footnote 18]

7.3 Status and statelessness

7.3.1 On 17 October 2007, AI published a report entitled: ‘Lebanon: Exiled and suffering: Palestinian refugees in Lebanon’ which stated: ‘… [V]irtually all stateless people in Lebanon are Palestinian refugees, and most Palestinian refugees are stateless.’[footnote 19]

7.3.2 An undated section of MAP’s website, entitled ‘The Issues’, states: ‘Since then [the Nakba in 1947-8], most Palestinians have not been granted Lebanese citizenship, instead remaining stateless.’[footnote 20]

7.3.3 On 20 June 2019, the European Network on Statelessness, ‘a civil society alliance of over 180 organisations and individual experts in 41 countries… committed to ending statelessness’,[footnote 21] published a blog entitled ‘A visit to Lebanon’ which stated

‘… Lebanon is not a signatory to either the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness or the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, creating a fundamental legislative gap in the legal framework and thus denying nationality to thousands of people in Lebanon. Simply put, the country is lacking any binding legal commitment to prevent or eradicate statelessness.

‘… Lebanon is neither a party to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees.’[footnote 22]

7.3.4 On 23 July 2019, Middle East Eye, ‘an independently funded digital news organisation covering stories from the Middle East and North Africa’,[footnote 23] published an article entitled ‘Palestinian refugees in Lebanon denounce new “inhumane” work restrictions’ which stated:

‘… [F]or the past 72 years Lebanese laws and regulations have failed to address the civil status of Palestinians.

‘The lack of clear status for Palestinians is in large part due to longstanding sectarian tensions in the country, with Christian political parties long opposing steps to integrate the majority Sunni Muslim Palestinian community in Lebanese society, fearing that doing so would upend the sectarian balance of power.

‘As a result, depending on the legislation, Palestinians can be treated as refugees, foreigners, or stateless persons.’[footnote 24]

7.3.5 Dr. Albanese and Prof. Takkenberg’s June 2020 ‘Palestinian Refugees in International Law’ stated: ‘Palestine refugees are also considered a “special category of foreigners” not benefitting from specific refugee rights nor being allowed to naturalise…’[footnote 25]

7.3.6 On 26 November 2020, Frontiers, a publisher of community-driven and peer-reviewed academic journals[footnote 26], published an article written by Yafa El Masri, a doctorate student at the department of Geosciences at the University of Padua, Italy[footnote 27], entitled ‘72 Years of Homemaking in Waiting Zones: Lebanon’s “Permanently Temporary” Palestinian Refugee Camps’, citing various sources, which stated: ‘Palestine refugees are categorized as “stateless,” meaning that they lack citizenship of a recognized state. And since the Lebanese state has no specific consideration or hospitality regulation for their particular statelessness, Palestinian refugees in Lebanon receive the treatment of foreigners with no recognized state documents, thus depriving them from access to the most basic life elements: labor maker, health and education.’[footnote 28]

7.3.7 On 4 February 2021, Deutsche Welle (DW), a German broadcaster[footnote 29], published an article entitled ‘Palestinians in Lebanon: “The world has forgotten us”’ which stated: ‘In Lebanon, Palestinian refugees pass on their refugee status to their children.’[footnote 30]

7.3.8 On 30 July 2021, Peace Direct, ‘an international charity dedicated to supporting local people to stop war and build lasting peace in some of the world’s most fragile countries’,[footnote 31] published a blog entitled ‘Palestinians of Lebanon: Generations of refugees denied integration and basic rights’ which stated:

‘Palestinians are considered by Lebanese authorities as “refugees”… Some argue that the Palestinians, smaller in numbers [than Syrians in Lebanon], possess a “special” status, falling under the mandate of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). They have their own international agency…

‘… Meanwhile, some populist Lebanese politicians are increasingly arguing that a refugee status is not inherited, implying that Palestinians born in Lebanon should not be considered as refugees but children and grandchildren of refugees.’[footnote 32]

7.3.9 On 20 March 2023, the United States Department of State (USSD) published a report entitled ‘2022 Country Report on Human Rights Practices: Lebanon’, covering events in 2022, (the USSD 2022 Country Report) which stated: ‘There were no official statistics on the size of the stateless population. The country contributes to statelessness, including through: discrimination against women in nationality laws; discrimination on other grounds, such as ethnicity, religion, or disability, in nationality laws or their administration in practice; and discrimination in birth registrations.’[footnote 33]

7.4 ‘Categories’ of Palestinians

7.4.1 In February 2016, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) published a report entitled ‘The Situation of Palestinian Refugees in Lebanon’, citing various sources, which stated:

‘Based on their legal status and registration with the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), Palestinian refugees in Lebanon can be categorized into four groups:

-

‘“Registered” refugees (“Palestine refugees”), which are registered with UNRWA and the Lebanese authorities;

-

‘“Non-registered” Palestinian refugees, which are not registered with UNRWA, but are registered with the Lebanese authorities;

-

‘“Non-ID” Palestinian refugees, who are neither registered with UNRWA nor with the Lebanese authorities; and

-

‘Palestine refugees from Syria, who have arrived in Lebanon since 2011.’[footnote 34]

7.4.2 Dr. Albanese and Prof. Takkenberg’s June 2020 ‘Palestinian Refugees in International Law’ stated: ‘Among these stateless Palestinians, only those registered in Lebanon – and holding a Lebanese ID – according to Lebanese regulations are considered legal residents… Ultimately only those registered with DPRA [Directorate of Political Affairs and Refugees] – i.e. Palestinians falling in the first two groups – are considered legally resident…’[footnote 35]

7.4.3 The different ‘categories’ of Palestinians are covered in more detail in the sections below.

7.4.4 For more information on the role of UNRWA for Palestinians in Lebanon, see United Nations Relief and Works Agency in the Near East (UNRWA) services.

7.5 ‘Registered’ Palestinians

7.5.1 An undated page on UNRWA’s website, entitled ‘Palestine Refugees’, states: ‘Palestine refugees are defined as “persons whose normal place of residence was Palestine during the period 1 June 1946 to 15 May 1948, and who lost both home and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 conflict.”… The descendants of Palestine refugee males, including adopted children, are also eligible for registration.’[footnote 36]

7.5.2 Dr. Albanese and Prof. Takkenberg’s June 2020 ‘Palestinian Refugees in International Law’ stated: ‘They [“1948 refugees”] are… registered with DPRA and hold a DPRA-issued “Identification Card for Palestine Refugee”, which officially confirms their legal residence in Lebanon.

‘While registration gives Palestine refugees legal residence… in practice, they remain foreigners in the country.’[footnote 37]

7.5.3 On 14 April 2022, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) published a report entitled ‘Increasing Humanitarian Needs in Lebanon’ which attributed UNRWA’s definition of Palestine refugees to the UNHCR’s first ‘category’ of Palestinians, namely ‘registered’ refugees, and referred to them as ‘Palestine Refugees in Lebanon (PRL)’ [footnote 38].

7.5.4 The USSD 2022 Country Report stated that Palestinian refugees who are registered with UNRWA are considered foreigners under Lebanese law[footnote 39].

7.5.5 DFAT’s June 2023 country report stated: ‘For political reasons, both Lebanese authorities and the PRLs themselves have long opposed moves to naturalise PRLs. Accordingly, despite their longstanding presence in Lebanon, PRLs remain excluded from key aspects of social, political, and economic life.’[footnote 40]

7.5.6 The 3 March 2020 DIS/UNRWA meeting minutes, published in an appendix to DIS’s June 2020 report, stated: ‘UNRWA explained that recently some Palestine Refugees in Lebanon have attempted to deregister from UNRWA, hoping that this would allow for them to fall under UNHCR’s mandate… UNRWA has communicated that deregistration in itself will not remove the individual from falling under the mandate of UNRWA.’[footnote 41]

7.6 ‘Non-registered’ Palestinians

7.6.1 UNOCHA’s April 2022 report defined ‘non-registered’ Palestinians in Lebanon as: ‘Those not registered with UNRWA who were displaced as a result of the 1967 and subsequent hostilities, and who are registered with the Lebanese Government (referred to as “Not-Registered” or NR by UNRWA) (numbers unknown)’.[footnote 42]

7.6.2 The UNHCR’s February 2016 report stated:

‘Lebanon’s regulation of Palestine refugees’ status reportedly dates back to 1959, when the Department of Palestinian Refugees Affairs (DPRA) [renamed as “Directorate of Political Affairs and Refugees” (DPAR) by the Lebanese government in 2010] was created… The Minister of Interior’s Ordinance No. 319 of 2 August 1962 details the process for the regularization of residency for Palestinian refugees, in which they are considered to be “foreigners who do not carry documentation from their countries of origin, and reside in Lebanon on the basis of [residency] cards issued by the Directorate of Public Security, or identity cards issued by the [DPRA]”. However, while the possession of a valid residency or identity card is required to regularize their residency status, there is no clear provision defining what categories of Palestinian refugees are entitled to such a card.

‘… Newborns are reportedly registered with the family’s original place of registration, regardless of where in Lebanon they were born.

‘… A refugee’s registration with DPAR is reportedly only cancelled in three specific events, namely, (i) in the case of a refugee’s death and upon request of the General Security to DPAR to cancel the person’s registration following their death, or (ii) if the refugee obtains the nationality of a third country, or (iii) if the refugee has submitted an application to the General Security to have his/her registration cancelled.’[footnote 43]

7.6.3 Dr. Albanese and Prof. Takkenberg’s June 2020 ‘Palestinian Refugees in International Law’ stated:

‘Approximately 35,000 refugees from Mandate Palestine and their descendants (i.e. “1948 refugees”), are not registered with UNRWA in Lebanon. They are often referred to as “NR”. Their lack of registration with UNRWA has various causes: they may have not been in need of humanitarian assistance in 1948, and hence not met UNRWA’s registration and eligibility criteria; they may have taken refuge outside UNRWA’s area of operations in 1948 and moved to Lebanon later on; or they may have arrived to Lebanon not in connection with the 1948 events (e.g. 1967, 1970). They are nonetheless registered with the Lebanese authorities and as such they hold the same DPRA-issued Identification Cards issued to registered Palestine refugees. The majority of them have a proof of nationality document from the Palestinian embassy in Lebanon. Lebanese authorities treat them similarly to UNRWA-registered refugees…’[footnote 44]

7.6.4 The USSD 2022 Country Report stated:

‘Children of Palestinian refugees faced discrimination in birth registration, as bureaucratic and administrative procedures at the Directorate of Political Affairs and Refugees (DPRA) made it difficult to register these children after the age of one year. According to the law, birth registration of children older than one year requires a court procedure, in some cases an investigation by the DGS [General Directorate of Security], and final approval from the DPRA. Where paternity is in doubt or the applicant is age 18 years more, he or she may also be required to take a DNA test. The birth registration process can take more than a year to complete and is extremely complex to navigate, especially for the DPRA-registered parents of Palestinian refugee children.’[footnote 45]

7.6.5 The 3 March 2020 DIS/UNRWA meeting minutes, published in an appendix to DIS’s June 2020 report, stated:

‘UNRWA began maintaining Palestine Refugees registration records in May 1950 and the initial registration process closed in June 1952. Therefore, in Lebanon individuals who wish to register with UNRWA who were not included in the initial registration will need prior approval from the Lebanese authorities before they can obtain an UNRWA registration. Persons residing outside of Lebanon, who wish to register with UNRWA in Lebanon, can apply for a preapproval through a Lebanese embassy. The Lebanese authorities also check against UNRWA registrations to see if the registration files match.’[footnote 46]

7.7 ‘Non-ID’ Palestinians

7.7.1 UNOCHA’s April 2022 report defined ‘non-ID’ Palestinians in Lebanon as: ‘Palestinian refugees who lack identity documents and are neither registered with UNRWA nor with the Lebanese authorities (referred to as “Non-IDs”), likely to be an estimated 5000’.[footnote 47]

7.7.2 In September 2020, UNRWA published a report entitled ‘Protection brief: Palestine refugees living in Lebanon’, citing various sources, which stated: ‘There are an estimated 4,000 Non-ID Palestinians in Lebanon. These are Palestinians who began to arrive in Lebanon in the 1960s and do not hold formal valid identification documents recognized by the GoL [Government of Lebanon]… they do not have valid legal status in the country.’[footnote 48]

7.7.3 Dr. Albanese and Prof. Takkenberg’s June 2020 ‘Palestinian Refugees in International Law’ stated:

‘This non-homogenous group includes: 1) Palestinians in Lebanon since the late 1960s and 1970s who are not registered with either the Lebanese authorities or UNRWA in Lebanon, although they may be registered with UNRWA elsewhere; they may have some form of documentation to prove their Palestinian identity, either from one of UNRWA’s “fields” of operations (e.g. Palestinians holding valid or expired Jordanian IDs, who are unable to return to Jordan or the West Bank if the holder was originally from there prior to 1988; 2) Palestinians from the Gaza Strip with Egyptian TDPRs [Travel Documents for Palestinian Refugees] who are not allowed either to stay in Egypt or to return to Gaza (those who left Gaza before 1967); 3) Palestinians expelled by Israel from the oPt post-1967 and not allowed to return; 4) Palestinians from any Arab country (e.g. Iraq, Egypt) who for various reasons are unable to return there. As such, these Palestinians fall in the category of “[f]oreign nationals who do not hold identity papers from their country of origin [ … ], residence cards issued by the General Directorate of General Security [Sûreté Générale] or identity cards issued by [the DPRA]”.

‘… As a result [of the harsher restrictions they face compared with Palestinians registered with Lebanese authorities and/or UNRWA in Lebanon], many have confined themselves to the camps, out of reach of the Lebanese authorities.’[footnote 49]

7.7.4 The USSD 2022 Country Report stated: ‘UNRWA estimated that 3,000 to 5,000 Palestinians remained unregistered with either it or the government… The government does not recognize their legal status in the country… [A]nd [they] encountered obstacles completing civil registration procedures.’[footnote 50]

7.7.5 DFAT’s June 2023 country report stated: ‘… [This] category is a group of between 3,000 to 5,000 Palestinians who arrived in Lebanon with the Palestine Liberation Organization after its defeat in the Black September conflict in Jordan. This group is effectively stateless: they are not registered with the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA); they are spread across the country; and they do not have any designated advocates.’[footnote 51]

7.8 Palestinians from Syria

7.8.1 UNOCHA’s April 2022 report defined Palestinians from Syria in Lebanon as: ‘Palestinian refugees from Syria (PRS), who have arrived in Lebanon since 2013 and who may or may not have regular status in Lebanon.’[footnote 52]

7.8.2 UNRWA’s September 2020 ‘Protection brief’ report stated:

‘In 2011, at the onset of the Syrian conflict, the General Security Office (GSO) initially facilitated access of PRS to Lebanon. However, these measures were never formalized by the GSO and in August 2013 and May 2014 facilitating measures were removed and additional restrictions imposed… Since then [January 2015], entry visas are only granted at the border to PRS with either a verified embassy appointment in Lebanon or a flight ticket and visa to a third country. Most are issued with a 24-hour transit visa. In addition, a very limited numbers of PRS can secure a visa for Lebanon by obtaining prior approval from the GSO, which requires a sponsor in Lebanon and cannot be processed at border posts.

‘Some PRS have sought to enter Lebanon through irregular border crossings, placing them at additional risk of exploitation and abuse both during the crossing and once they arrive in Lebanon.

‘Irregular entry into Lebanon is an obstacle to later regularizing one’s legal status and while several memoranda have been issued by the GSO since October 2015, allowing for a free-of charge renewal of residency documents, persons who have entered irregularly are exempted. A considerable number of PRS are therefore still unable to regularize their stay in Lebanon. In addition, lack of awareness has meant that some PRS have not renewed their documents and are therefore considered by the authorities as illegally staying in Lebanon.

‘The General Directorate of General Security announced on 17 July 2o2o [sic] that Arab citizens and foreigners who entered Lebanon irregularly and those whose legal residency and work permit have expired are able to regularize their status between 31/07/2020 to 31/10/2020. However, regularisation is only possible by securing a sponsor and a work permit. Hence, the impact on PRS is expected to be minimal.

‘… A survey conducted during the first half of 2020 indicated that 34 per cent of PRS in Lebanon do not hold valid residency documents.

‘… On 24 April 2019, a series of decisions announced by the High Defence Council in Lebanon resulted in stricter enforcement of national laws and the promulgation of a new regulation affecting refugees. The decision to deport Syrians who entered the country illegally after 24 April 2019, coupled with departure orders issued to Syrians and PRS without valid residency who entered before that date, has resulted in an increased fear of deportation among PRS. UNRWA recorded the first cases of PRS deportations, including of two women and four minors, in late 2019 and early 2020.

‘… In recent years, UNRWA has also recorded a number of spontaneous returns by PRS families and individuals to Syria. In 2019, UNRWA recorded the return to habitual residence of 2,240 PRS individuals. The numbers for 2020 were significantly lower, including due to COVID-19 containment measures.’[footnote 53]

7.8.3 On 13 February 2023, UNRWA published a ‘Protection Monitoring Report – Quarter 4 (Q4) 2022’, citing various sources, which stated:

‘Lack of residency was repeatedly raised by PRS as a major issue affecting them. For many, this is due to their entering the country irregularly after January 2014, after which date they have only been able to enter regularly in an extremely limited number of circumstances. Renewing residency was also a major concern for those PRS who were eligible for it. While the most recent figures for residency among PRS date from April 2021 and indicate that 51 per cent did not have residency, this is likely to have risen as transport and other associated costs have increased and government offices have often been shut.’[footnote 54]

7.8.4 CRS’ May 2023 report stated: ‘The Syria conflict displaced not only Syrian nationals, but also an estimated 27,700 Palestinian refugees from refugee camps inside Syria. PRS are not eligible for services provided by UNHCR, and must instead register with the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) to receive continued emergency support.’[footnote 55]

7.8.5 DFAT’s June 2023 country report stated: ‘Even later arrivals, such as PRSs who came after 2016, cannot get residency in Lebanon at all.’[footnote 56]

7.9 Demography

7.9.1 MAP’s May 2018 report stated: ‘Some 450,000 Palestinian refugees are registered with UNRWA in Lebanon, but in late 2017 the results of a census were announced stating that 174,422 Palestinian refugees were living in camps and gatherings in Lebanon (the number living outside of the camps and gatherings is not known) as well as a further 18,601 Palestinians who had fled to the country from Syria.’[footnote 57]

7.9.2 On 16 October 2019, the Central Administration of Statistics (CAS) - Lebanon, the Lebanese Palestinian Dialogue Committee (LPDC), and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS), published a joint detailed report of the 2017 census findings, entitled ‘Population and Housing Census in the Palestinian Camps and Gatherings in Lebanon 2017’. Describing the census as ‘… an ambitious project’,[footnote 58] the census was carried out across the following locations:

-

Palestinian Camps: ‘… a geographic area that has been placed at UNRWA’s disposal by the Lebanese host Government or leased by UNRWA for the purpose of housing Palestinian refugees and building facilities to address their needs. Areas not allocated for that purpose are not considered official camps.’[footnote 59]

-

Adjacent Gatherings (to the camps): ‘… considered an extension to the official camps due to wars, displacement and the need to expand the camps areas due to population increase.’[footnote 60]

-

Other Gatherings: ‘Areas where Palestinians live within the neighborhoods of villages and urban areas across national territories.’[footnote 61]

The report, however, also acknowledged it ‘… possibly excluded some “other places of residence on the Lebanese territory”’, and that only when a full population census of Lebanon is taken will isolated Palestinian refugees there also be included[footnote 62].

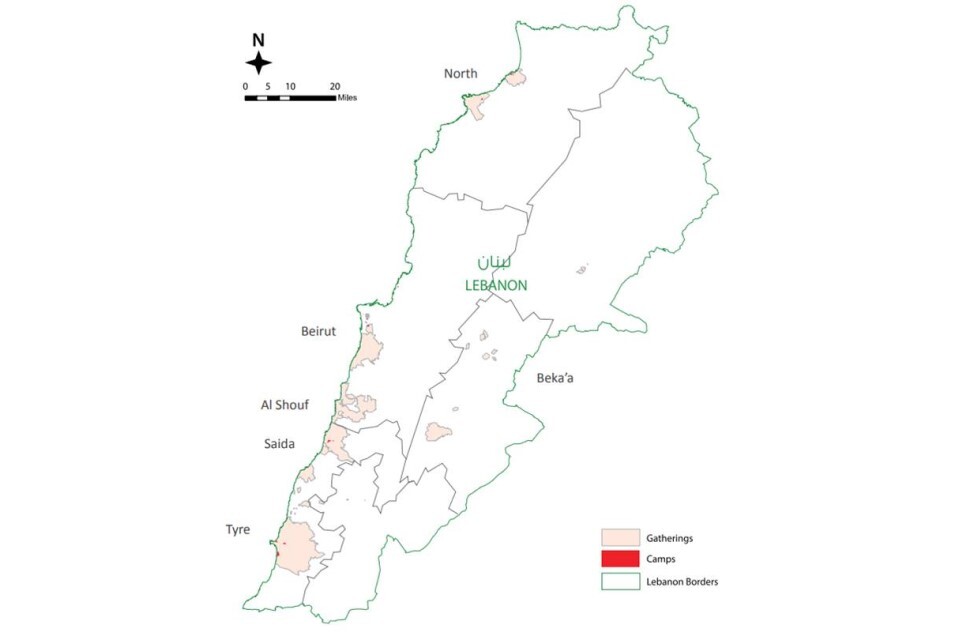

7.9.3 The same source published the following, undated, map showing the locations of the 12 Palestinian refugee camps and Palestinian gatherings in Lebanon:

[Map shows gatherings in the North, Beirut, Al Shouf, Saida, Tyre and Beka’a. Camps are shown to be mainly in Beirut, Saida and Tyre.]

7.9.4 The same source noted the following other salient points:

-

the census counted 183,255 Palestinian refugees across 168 localities in refugee camps, adjacent gatherings, and other gatherings. 23 of the other gatherings had fewer than 15 households each, totalling 554 individuals, while 10 localities (consisting of six camps, two adjacent gatherings, and two other gatherings) held a combined 29,216 households, totalling 119,208 individuals[footnote 64]

-

the highest number of Palestinian refugees (35.3%) were based in Saida, followed by the North (24.7%). The smallest numbers of Palestinian refugees were found in the Mount Lebanon (7.5%) and Beka’a (4.7%) regions. Of the 183,255 Palestinian refugees, 165,549 (90.3%) were Palestinian refugee residents in Lebanon (PRLs), while 17,706 were Palestinian refugees coming from Syria (PRSs)[footnote 65]

-

while the four ‘categories’ of Palestinians were acknowledged, for the purposes of reporting, the census split Palestinian refugees into just two categories. Namely, PRLs comprising both registered and non-registered Palestinians, and PRSs comprising Palestinian refugees displaced from Syria and the non-ID refugee population[footnote 66]

-

Ain el-Hilweh Camp, accommodates 11.1% of all refugees and 11.3% of the PRLs. Adjacent gatherings at Ain el-Hilweh, and other gatherings at Mount Lebanon, both account for more than 10% of PRSs, which also indicates that significant numbers of the refugees have settled away from the refugee camps[footnote 67]

-

Palestine refugees in Lebanon were found to be a young population, with approximately 39% under the age of 20, and 50% under the age of 25 (26 for females)[footnote 68]

7.9.5 UNRWA’s September 2020 ‘Protection brief’ report stated that the approximately 55% of Palestine refugees who do not reside in the 12 official Palestine refugee camps, instead reside in gatherings or cities in Lebanon[footnote 69].

7.9.6 In July 2023, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) updated their ‘Where We Work: Lebanon’ webpage, stating:

‘As of March 2023, the total number of UNRWA registered Palestine Refugees in Lebanon is 489,292 persons. In addition, UNRWA records show a total of 31,400 Palestine Refugees from Syria residing in Lebanon. However, registration with UNRWA is voluntary; deaths as well as emigration remain often unreported, and refugees can continue registering newborns as they move abroad through the UNRWA online registration system. In 2017, the… census among Palestinians living in Lebanon… reported a total of 174,000 persons. A total of 45 per cent of Palestine Refugees are estimated to live in the country’s 12 refugee camps. About 200,000 Palestine Refugees access UNRWA services in Lebanon every year. The Agency’s current estimation is that no more than 250,000 Palestine Refugees currently reside in the country.’[footnote 70]

Section updated: 4 March 2024

8. Daily life

8.1 United Nations Relief and Works Agency in the Near East (UNRWA) services

8.1.1 Yafa El Masri’s article, published by Frontiers on 26 November 2020, stated: ‘UNRWA, referred to in the local Palestinian community as “the witness to the Palestinian crisis,” is a UN agency established solely for the assistance and employment of Palestinian refugees… UNRWA provides a space of living for Palestine refugees by renting the area of refugee camps from the Lebanese government and private property owners, in addition to the provision of basic services such as health and education.’[footnote 71]

8.1.2 UNRWA’s undated ‘Palestine Refugees’ webpage states: ‘UNRWA services are available to all those living in its area of operations who meet this definition [see ‘Registered’ Palestinians for UNRWA’s definition], who are registered with the Agency and who need assistance.’[footnote 72]

8.1.3 Dr. Albanese and Prof. Takkenberg’s June 2020 ‘Palestinian Refugees in International Law’ stated that since 2004, UNRWA had continued to assist some ‘non-registered’ Palestinians as they too are refugees from Palestine with no assistance from Lebanese authorities[footnote 73].

8.1.4 DW’s February 2021 ‘The world has forgotten us’ article stated: ‘The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) is responsible for the Palestinian refugees in the 12 official camps in Lebanon. This is because Lebanon does not accept any costs for the Palestinians.’[footnote 74]

8.1.5 On 18 January 2022, UNRWA published a report entitled ‘Palestine refugees in Lebanon: struggling to survive’, citing various sources, which stated: ‘UNRWA remains the lifeline of Palestine refugees in Lebanon. However, the Agency is facing an ongoing financial crisis resulting from a chronic budget shortfall and austerity measures enforced for several years. As a result, the Agency’s ability to maintain and expand its protection and assistance role, and deliver quality services, is constantly at risk.’[footnote 75]

8.1.6 DFAT’s June 2023 country report stated: ‘PRLs are unable to access Lebanese public education, health or social services, and are generally dependent on UNRWA and NGOs for most aspects of their lives.’[footnote 76]

8.1.7 The USSD 2022 Country Report stated:

‘Undocumented Palestinians [also called ‘non-ID’ Palestinians] not registered in other countries where UNRWA operates, such as Syria or Jordan, were usually ineligible for the full range of UNRWA services. In most cases, and as part of its discretionary power to include vulnerable groups of Palestinians on an exceptional basis, UNRWA nonetheless provided primary health care, education, and vocational training services to undocumented Palestinians. The majority of these were men, many of them married to UNRWA-registered refugees or Lebanese citizen women, who could not transmit refugee status or citizenship to their husbands or children.’[footnote 77]

8.1.8 The same source stated: ‘Palestinian refugees who arrived from Syria since 2011 received limited basic support from UNRWA, including food aid, cash assistance, and winter assistance, such as cash to purchase fuel for heating. Authorities permitted children of PRS to enroll in UNRWA schools and access UNRWA health clinics.’[footnote 78]

8.1.9 On 26 June 2023, the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (Germany) (BAMF) published ‘Briefing Notes’ which stated: ‘On 22.06.23, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) announced that without short-term funding, the agency’s approximately 700 schools and 140 health centres in Lebanon would have to cease operations from around September 2023.’[footnote 79]

8.1.10 On 27 July 2023, UNRWA published a report entitled ‘Annual operational report 2022’ which stated:

‘Through the 2022 Syria, Lebanon and Jordan EA [emergency appeal], UNRWA continued to provide humanitarian assistance, including emergency cash, health, education and protection assistance to 30,134 PRS registered with the Agency in Lebanon and PRL impacted by the socio-economic crisis. During the reporting period [the 2022 calendar year[footnote 80]], cash grants for basic needs were provided to all PRS in Lebanon… with one-off emergency top-up payments provided to 9,606 PRS families in need.

‘… In the face of rampant inflation and the depreciation of the LBP [Lebanese pound], in July, the Agency provided cash assistance payments in US$ in an attempt to stabilise the value of its support… Violent incidents against UNRWA staff continued to pose a significant challenge to service delivery, particularly in health centres, where demand for medicines unobtainable through other health providers spiked.

‘… UNRWA installations were closed for a total of 246 working days in addition to 18 days of partial closures. These closures were largely due to demonstrations and sit-ins by Palestine refugees demanding discretionary services such as CfW [cash-for-work], rental allowances, cash assistance or hospitalisation support, or expressing their frustration at the perceived inadequacy of the Agency’s level of service provision.’

‘… [F]om January to December 2022… In Lebanon, UNRWA could only provide three rounds of assistance to PRL in need as the level of funding received did not allow for the provision of assistance on a monthly basis as initially planned… [T]argets for EiE [education in emergencies], emergency health, the repair of UNRWA installations, safety and security and environmental health, were not met due to insufficient funding.’[footnote 81]

8.2 Accommodation

8.2.1 The CAS, LPDC, and PCBS joint report on the 2017 census, published on 16 October 2019, stated:

‘UNRWA, mandated with the duty of providing shelter and services to Palestine refugees, established a number of recognized Camps (which have been repaired or rebuilt from time to time) dispersed in all Lebanese regions for the refugees to reside therein until 2001. Lebanese laws on the right of foreigners to ownership, applicable to Palestinian refugees being Arab nationals, have allowed them the right to own built real-estates, or real-estates dedicated to construction within certain limits. However, this provision was amended in April 2001 and it became virtually impossible for Palestinian refugees to purchase real estate thereafter.’[footnote 82]

8.2.2 A blog entitled ‘Housing Programmes in Lebanon’, published by Habitat for Humanity Great Britain, ‘An international charity fighting global poverty housing’[footnote 83], which, while undated, refers to events in 2019, stated: ‘Besides the 12 main camps that Lebanon has ringfenced to host their refugee communities, there are hundreds of smaller settlements scattered all over the country. Many are severely overpopulated and are in a state of general despair, but by making small renovations and improvements to abandoned, temporary, or war-torn homes, Habitat for Humanity in Lebanon has supported over 30,000 people.’[footnote 84]

8.2.3 UNRWA’s September 2020 ‘Protection brief’ report stated: ‘Since the adoption of Law 296/2001, Palestine refugees are prevented from legally acquiring and transferring immovable property in Lebanon. This has led to insecurity of tenure as many have been forced into informal rental arrangements and have been deprived of the benefits of property ownership. As a result of the ongoing economic crisis, Palestine refugees are increasingly at risk of evictions.’[footnote 85]

8.2.4 Yafa El Masri’s article, published by Frontiers on 26 November 2020, stated:

‘… [T]he camp [Borj Alabarajenah refugee camp] is only rented by the UNRWA from the public/private landowners. However, an entire market of property buying, renting, and selling has been established on this space by camp dwellers who are not actual owners of the properties involved in the exchange. Nevertheless, for organizational purposes, sale and purchase activities are recorded at the camp popular committee in a way to protect dwellers from potential property conflicts.’[footnote 86]

8.2.5 On 12 April 2022, the USSD published a report entitled ‘2021 Country Report on Human Rights Practices: Lebanon’, covering events in 2021, which stated that while Palestinians were legally excluded from buying or inheriting property in Lebanon, and were typically unable to own land, those Palestinians who owned and registered property prior to the 2001 change in the law, were able to pass it on to their heirs[footnote 87].

8.2.6 On 26 August 2022, UNRWA published a ‘Protection Monitoring Report – Quarter 2 (Q2) 2022’, citing various sources, which stated:

‘Focal points in Tyre, northern Lebanon and Beqaa areas noted that reports of eviction and/or threats of eviction increased in Q2. However, exact figures are unavailable as many Palestinian refugees are reportedly moving to cheaper accommodation voluntarily when landlords tell them their rent will be increased or required in US dollars, or that they will soon be evicted. This means that many cases go unreported.

‘Focal points in Tyre and the north report that some of those facing eviction have moved in with relatives as a temporary solution, leading to crowded living conditions. In the Beqaa, some are reportedly trying to move into cheaper accommodation inside the area’s only camp, Wavel, although there is very little housing available. PRS are considered to be more vulnerable to eviction threats than PRL, who, in light of their long-standing presence in Lebanon, often hold more secure tenure over their property. Popular Committees in the camps were previously said to have interceded and negotiated in cases of threatened eviction, but are now reported to be less willing to do so.’[footnote 88]

8.2.7 The USSD 2022 Country Report stated:

‘According to UNRWA, poverty rates increased among Palestinian refugee families from 73 percent in July 2021 to 86 percent in March. Many Palestinian refugees experienced significant difficulties paying for essential goods and services including… electricity, and rent. Many received only a few hours of electricity per day and… Increasingly, landlords raised rents and required tenants to pay them in U.S.dollars; Palestinian refugees’ income was in Lebanese pounds, a currency that has lost 95 percent of its value since 2019.’[footnote 89]

8.2.8 In May 2023, REACH, ‘a leading humanitarian initiative providing granular data, timely information and in-depth analysis from contexts of crisis, disaster and displacement’[footnote 90] and UNOCHA jointly published a report entitled ‘Multi-Sector Needs Assessment: Key Multi-Sectoral Findings’. The findings in the report were based on the multi-sector needs assessment (MSNA) carried out by REACH in 2022 which was based on a sample size of 3,944 Lebanese households, 590 Palestinian Refugees in Lebanon (PRL) households, and 1,125 migrant households[footnote 91]. The report stated that 49% of PRL households were found to have unmet shelter needs, as compared with 33% of Lebanese households and 32% of migrant households. Additionally, 18% of PRL households were found to have unmet shelter needs to an extreme severity. The indicators driving the shelter severity score included the percentage of households living under the threat of eviction or an eviction notice, those living without any shelter or living in inadequate shelter, those living in a functional domestic space, and the percentage of households by main source of, and number of hours of access to, electricity[footnote 92].

8.2.9 For further information about accommodation within Palestinian refugee camps, see Conditions in refugee camps.

8.3 Education