Kickstart Scheme - process evaluation

Updated 21 July 2023

DWP research report no. 1032

A report of research carried out by IFF Research on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence.

Or write to:

Information Policy Team

The National Archives

Kew

London

TW9 4DU

Email: psi@nationalarchives.gov.uk

This document/publication is also available on the GOV.UK website

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email:

socialresearch@dwp.gov.uk

First published July 2023.

ISBN 978-1-78659-542-3

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Summary

Background

The Kickstart Scheme was one of the government’s flagship employment programmes to help young people in the wake of the economic downturn caused by the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. The scheme provided funding to create new jobs for 16- to 24-year-olds on Universal Credit who were at risk of long-term unemployment. Funding applied to jobs starting between September 2020 to the end of March 2022. Employers of all sizes could apply for funding for 100% of the national minimum wage for 25 hours per week for a total of 6 months. This included the option of applying through ‘gateway’ organisations which acted as an intermediary to help employers manage their Kickstart Scheme grant. Further funding was available for training and support (up to £1,500) so that young people on the scheme would be more likely to get a job in the future.

More details about the scheme can be found on the government’s website about the Kickstart Scheme.

Aims of the research

The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) commissioned IFF Research to conduct an evaluation of effectiveness of the Kickstart Scheme as a means of supporting young people during the pandemic and preventing them from becoming long-term unemployed. The study aimed to evaluate how Kickstart was experienced by participants; early outcomes for Kickstart participants; how the experience had contributed to longer-term employment or career aspirations, and how experiences and outcomes differed for different groups.

Methodology

This evaluation involved both qualitative (case study) and quantitative (survey) strands. Audiences for both strands included young people participating in Kickstart, gateways, and employers. Additionally, qualitative case studies explored the experience of Jobcentre Plus (JCP) staff — local authority leads, Kickstart District Account Managers (KDAMs), and work coaches — involved in the set-up and delivery of the scheme.

Quantitative interviews with young people took place approximately:

- one-to-three months after they started a Kickstart job (‘Starters’)

- seven months after they started a Kickstart job (‘Leavers at seven months’)

- a follow-up survey with those that took part in the Leavers at seven months survey, ten months after they started a Kickstart job which equates to around three months after completing (‘Leavers at ten months’)

Main findings

How did young people experience the Kickstart Scheme?

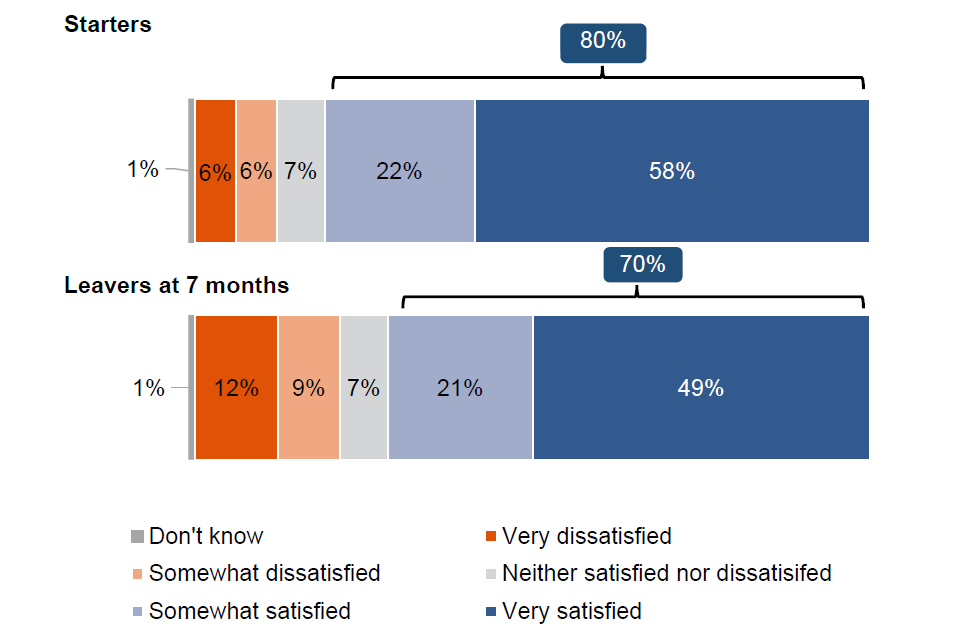

Most young people were satisfied with their Kickstart job. Seven-in-ten Leavers at seven months reported that they were satisfied. ‘Working with friendly staff or having a good team’ was the most common reason spontaneously offered as to why young people were satisfied with their Kickstart job (34% of Starters and 35% of Leavers at seven months who were satisfied).

Most young people reported that they worked for the 25 hours that Kickstart jobs were funded for (74% of Starters and 66% of Leavers at seven months), although small proportions worked more or fewer hours. Nearly all young people reported they were paid at least the National Minimum Wage (NMW) for their age in their Kickstart job (93% of Starters and 92% Leavers at seven months).

The majority of Kickstart jobs were with private sector organisations (70% of Leavers at seven months) and over half were with relatively small organisations (34% of Leavers at seven months had their Kickstart job with an organisation with two-to-nine employees, 23% ten-to-49 employees; for a small minority (4%) the Kickstart job was with a sole trader).

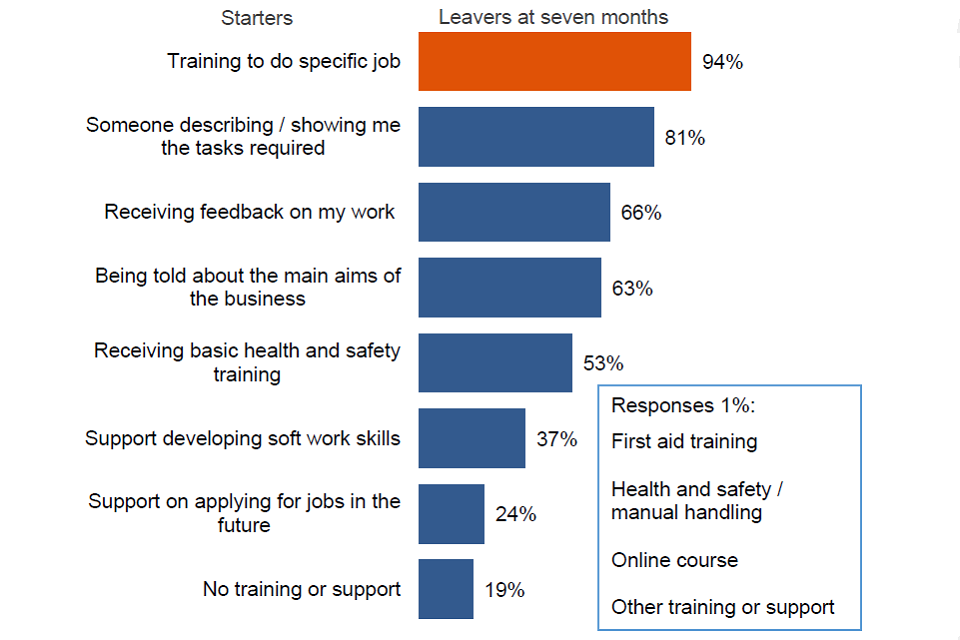

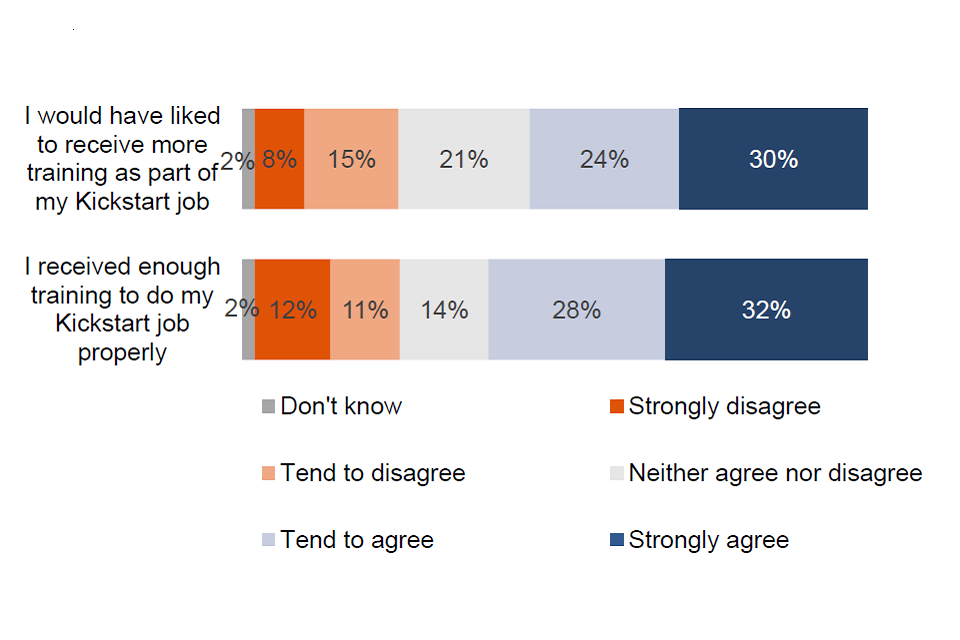

Nearly all young people (94% Leavers at seven months) reported having received some on-the-job training during their Kickstart role. However, over half (53%) of Leavers at ten months agreed they would have liked more training in their role. Much smaller proportions reported receiving employability support: only 37% of Leavers at seven months reported receiving support to develop soft skills, and 24% reported receiving support applying for jobs. When it was received, most young people found training and employability support useful.

Many young people who took part in the qualitative research had additional needs, including physical health conditions, mental health conditions, learning difficulties, neurological challenges, caring responsibilities, transport barriers, and language barriers. There were many positive examples where employers had made efforts to accommodate these either through day-to-day flexibility or formal reasonable adjustments. Anxiety was a widespread issue, and employers who reported this had tried to help through close mentoring, regular wellbeing calls, and taking a gentle approach to professional development review meetings.

Early Leavers

Among Leavers at seven months, nearly one-third (32%) had left their Kickstart job early. Receiving another job offer (22% of early leavers) or the employer terminating the role (21% of early leavers) were similarly likely to be a reason for leaving early.

Support from the Jobcentre Plus (JCP)

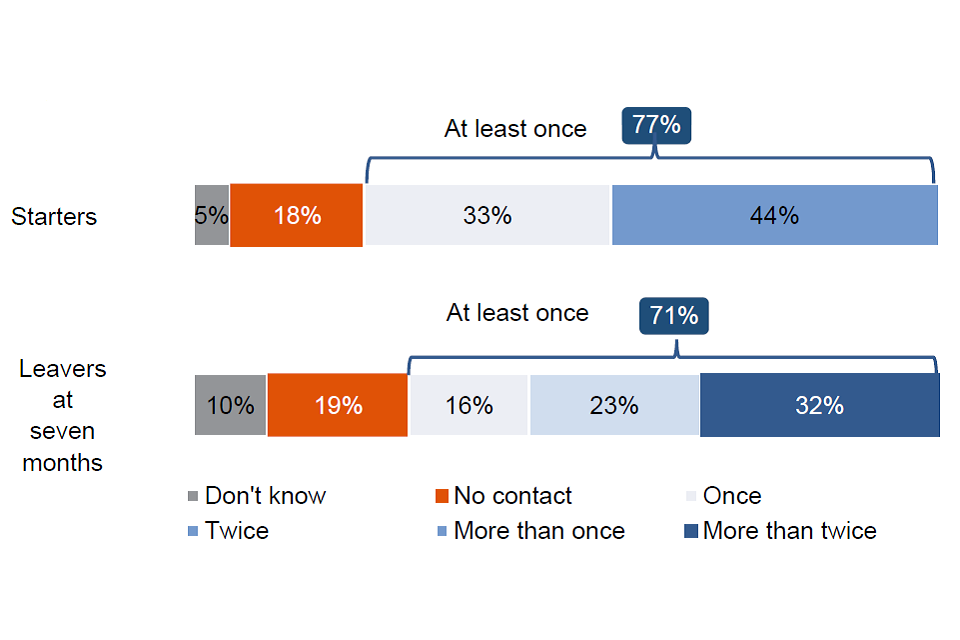

Around three-quarters of young people had contact from their work coach or other JCP staff while on their Kickstart job (77% of Starters; 71% of Leavers at seven months).[footnote 1]

Not having any contact with their work coach or JCP staff was more common among young people who were dissatisfied with their Kickstart job (24% of Leavers at seven months who were dissatisfied, compared to 18% of those satisfied).

What were the early employment, education, and training outcomes for young people?

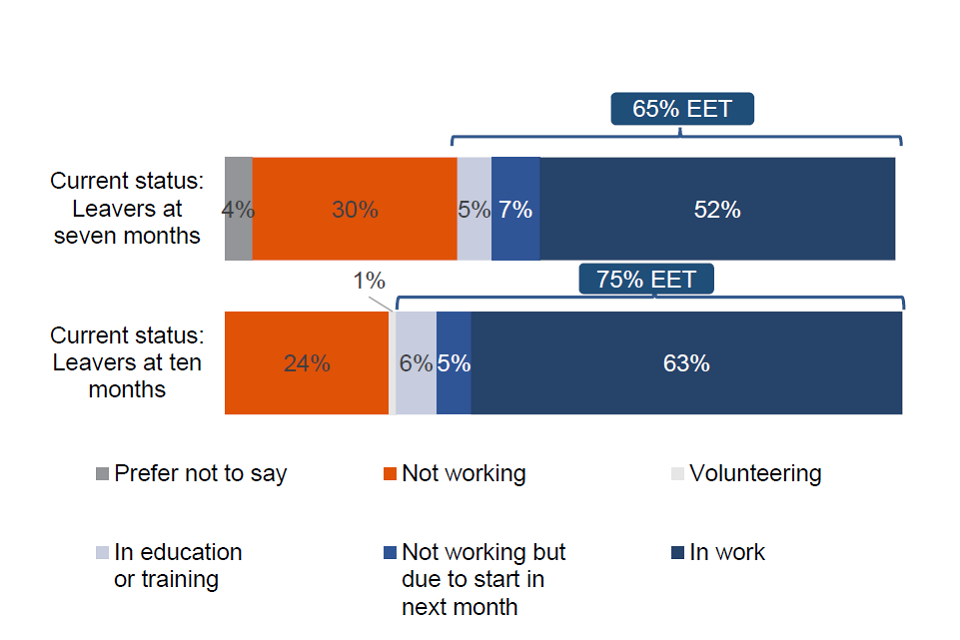

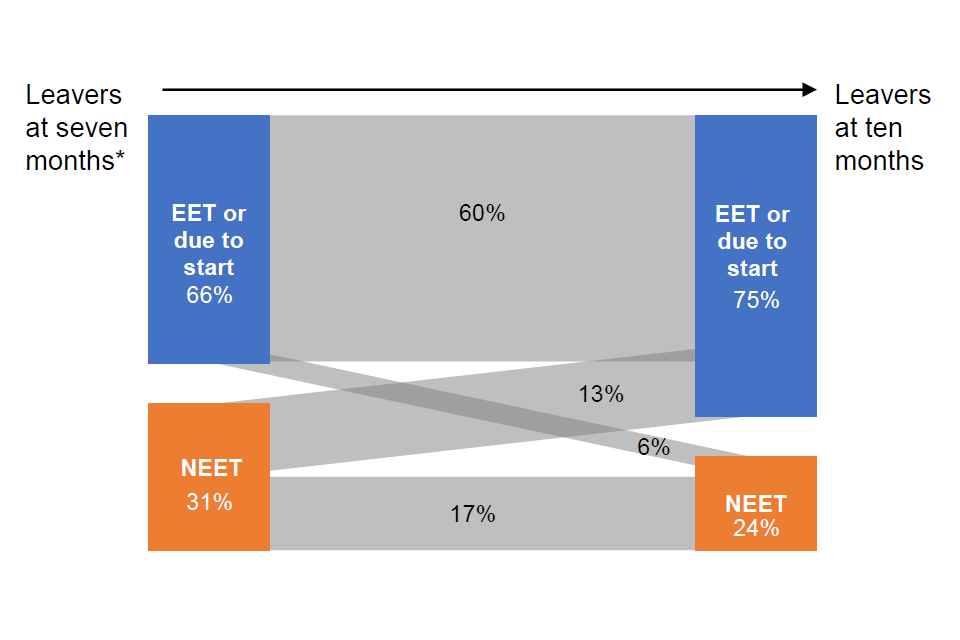

Kickstart Leavers often had positive employment, education, and training (EET)[footnote 2] early outcomes. Two-thirds (65%) of Leavers at seven months reported that they were EET and three-in-five (60%) Leavers reported that they were in work. For Leavers at ten months, the proportion of EET young people increased to more than three-quarters (75%) and 63% reported that they were in work. Seven per cent of Leavers at seven months and 5% of Leavers at ten months reported completing an apprenticeship.

Three-in-ten (31%) Leavers at seven months and one-fifth (24%) of Leavers at ten months reported that they were not in education, employment, or training (NEET). DWP will be carrying out a separate quasi-experimental analysis of the impact of the scheme, which will allow for a greater understanding of the extent of the impact compared to the counterfactual (whether or not the young people would probably have remained NEET without the existence of Kickstart).

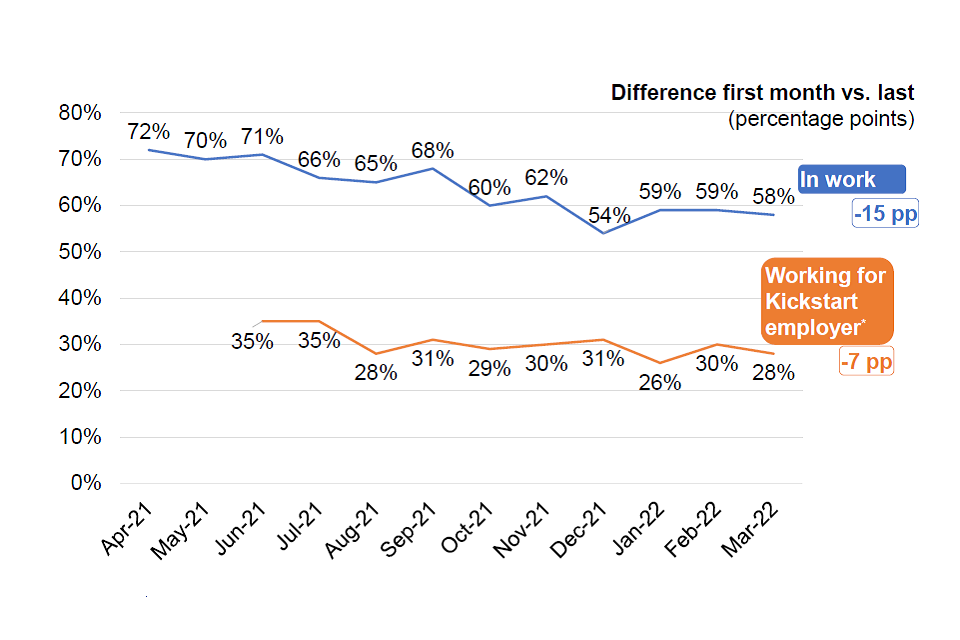

Continuing with their Kickstart employer

Three-in-ten (31%) Leavers at seven months were in paid employment with their Kickstart employer. For Leavers at ten months, the proportion in work that were still with their Kickstart employer had reduced slightly to 27%. This indicates that some Leavers had only remained with their Kickstart employer for a short time beyond the Kickstart job and had then moved on to alternative employment or become NEET.

Job quality of those in work after Kickstart

Most Leavers at ten months who were in work after Kickstart were satisfied with their current job overall (79%), hours worked (72%) and pay (61%). They also tended to agree with statements related to positive opportunities through their job, for example three-quarters (75%) felt their job offered opportunities to develop their career. A similar proportion (74%) were motivated to stay in their job.

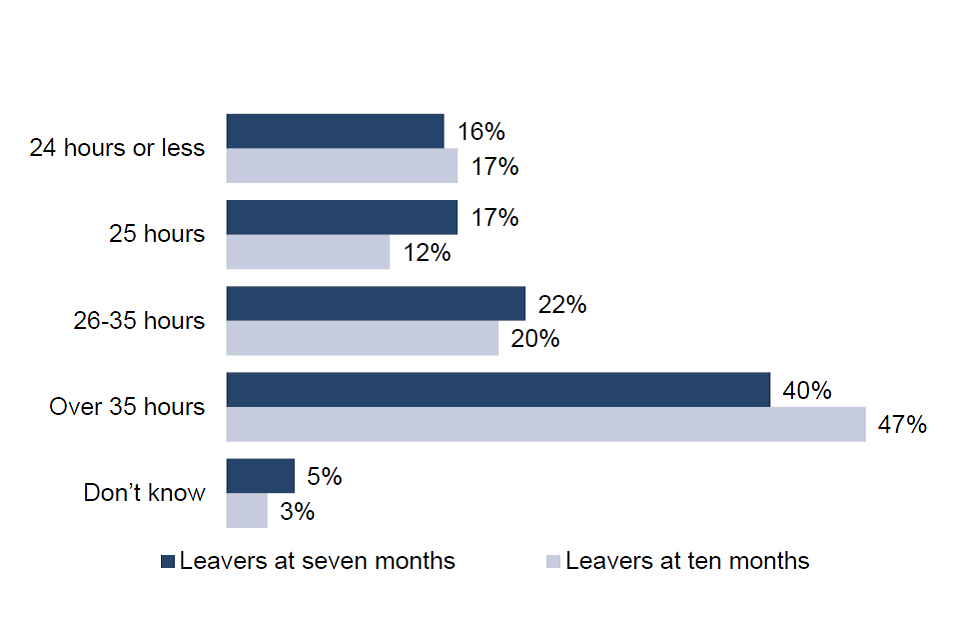

Nearly half of Leavers at ten months (47%) were working over 35 hours per week. The vast majority of Leavers in work at ten months (93%) were earning at least the National Minimum Wage (NMW) for their age. Just over three-fifths (64%) earned more than the NMW at ten months.

In education or training

A small proportion (5%) of Leavers at seven and (6%) at ten months went into education or training after their Kickstart job. Those in education or training were usually studying at degree level or above (54% at seven months, 62% at ten months).

Universal credit

Approximately one-third of Leavers at seven and ten months (37% and 38%, respectively) were claiming Universal Credit (UC) and expecting or receiving payments. At seven months, a further quarter (25%) were claiming UC but not expecting payments (for example, due to income or earnings); 15% were doing the same at ten months. A third (31%) at seven months and almost half (45%) at ten months were not claiming UC at all.

How has the experience contributed to longer-term employment aspirations?

Participation in Kickstart appears to have an impact on young people’s views on their prospective careers. Just under two-thirds (63%) of Starters said they would like to develop their careers in the same area of work as their Kickstart job. Among Leavers at seven and ten months, the proportion agreeing was lower (54% and 55%, respectively).

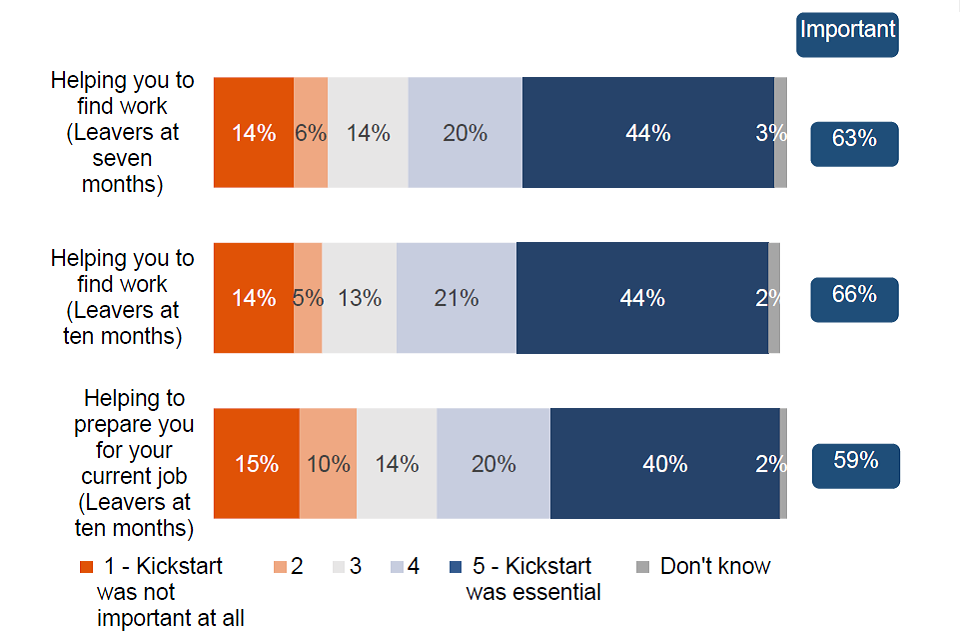

The majority of Leavers at seven and ten months (63% and 66%, respectively) who were in work said that the skills and experiences they gained through Kickstart had been important in helping them find work.

What other benefits have young people gained from taking part?

Self-assessment of employability and soft skills tended to be at high levels from young people one-to-three months into their Kickstart job through to Leavers at ten months. Qualitative interviews with both young people and employers indicated that Kickstart jobs tended to have the most influence on young people’s confidence (generally and professionally) and teamwork.

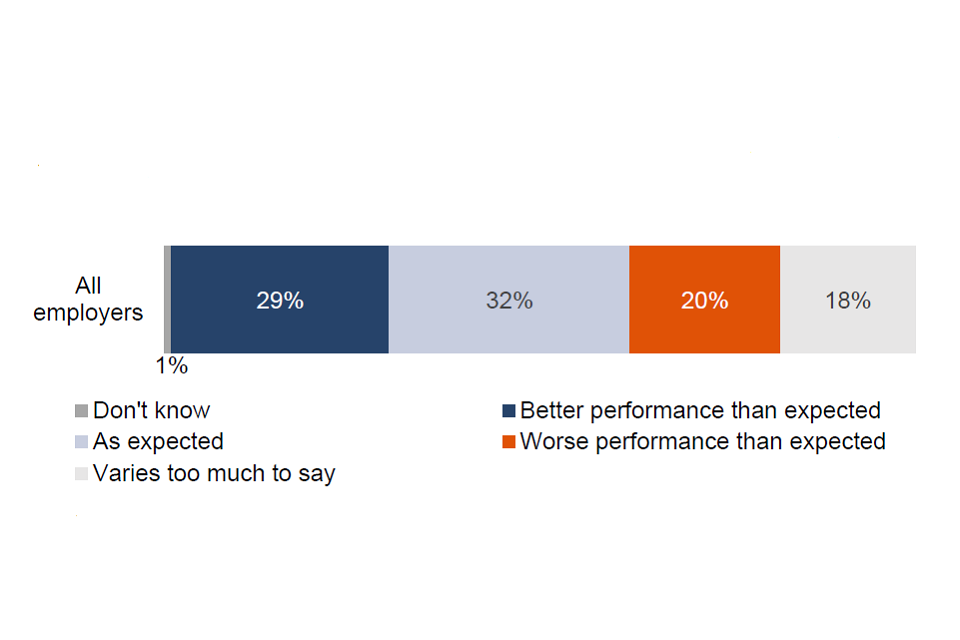

The majority of Kickstart employers reported large improvements in various soft skills among the young people they employed as part of the scheme. The soft skill which employers were most likely to report a large improvement in was self-confidence (72%). This was closely followed by working with others (70%), in line with young people’s qualitative accounts of where they felt they had strengthened.

Did experiences and outcomes differ for different groups of young people?

Young people with a health condition, particularly those for whom it substantially impacted their daily life, tended to have poorer experiences and outcomes from the Kickstart Scheme (although they were still more likely to have positive outcomes than not).

Starters with a health condition that substantially impacted their daily life[footnote 3] recorded relatively high levels of dissatisfaction with their Kickstart job. More than twice as many Starters were dissatisfied (23%) compared to those without a long-term health condition (10%), with the same trend for Leavers at seven months. Starters with a health condition that impacted daily life substantially were also more likely to have left the job early (21% compared to 10% of those with no long-term health condition). When providing reasons for dissatisfaction, lack of support was more likely to be reported as an issue by young people with a condition that impacted daily life substantially (25% of Starters in this group, compared to 11% with no long-term health issues).

Regarding outcomes, young people with any long-term health condition were more likely to be NEET at seven and ten months (51% and 32%). Furthermore, among those in work at ten months[footnote 4] those with a health condition were less likely to be satisfied in their role overall (75% compared to 81% with no long-term health condition).

Young people with a long-term health condition that impacted daily life substantially were also more likely to be claiming Universal Credit and receiving or expecting payments at the end of Kickstart, both at seven months (61%) and at ten months (60%).

Young people who were from ‘mixed or multiple ethnic groups’ or who were ‘Black, African, Caribbean or Black British’ were more dissatisfied than others (24% and 27% of Leavers at seven months compared to 21% of those who were ‘White (including White minorities)’), although the reasons given for dissatisfaction were similar between ethnic groups.

Other characteristics that were correlated[footnote 5] with satisfaction with Kickstart and outcomes include age, work experience prior to Kickstart and education level.

For Leavers at seven months, there was also a higher level of dissatisfaction among those who had at least 12 months’ prior experience of work (25% compared to 18% of those with no prior experience) and those with degree-level qualifications (24% compared to 19% of those with no or lower qualifications[footnote 6]). These differences were less evident for Starters, suggesting by the end of their Kickstart job, the experience started to feel less relevant or appropriate to these higher qualified / more experienced individuals.

NEET status at both seven and ten months was more common among the following groups of Leavers:

- those aged 18-to-21 (32% and 27%, respectively)

- those with lower or no qualifications (37% and 37%)

- those who had no prior work experience (37% and 29%)

However, when in work, these groups tended to be more satisfied with their job overall, including hours and pay, and were more motivated to stay in the job in the long term.

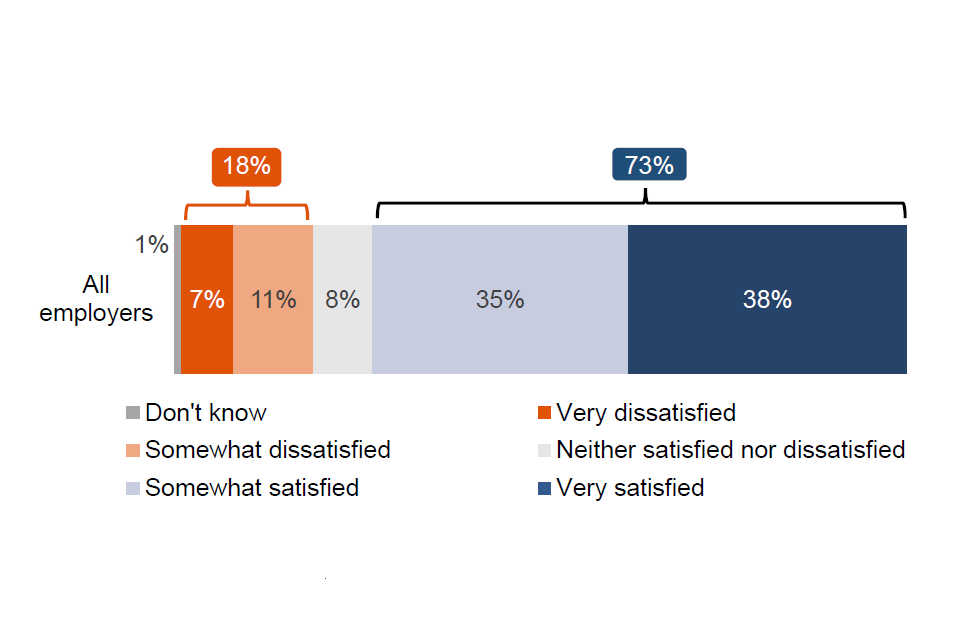

What were the experiences of Kickstart employers?

Experience of employing young people through the Scheme

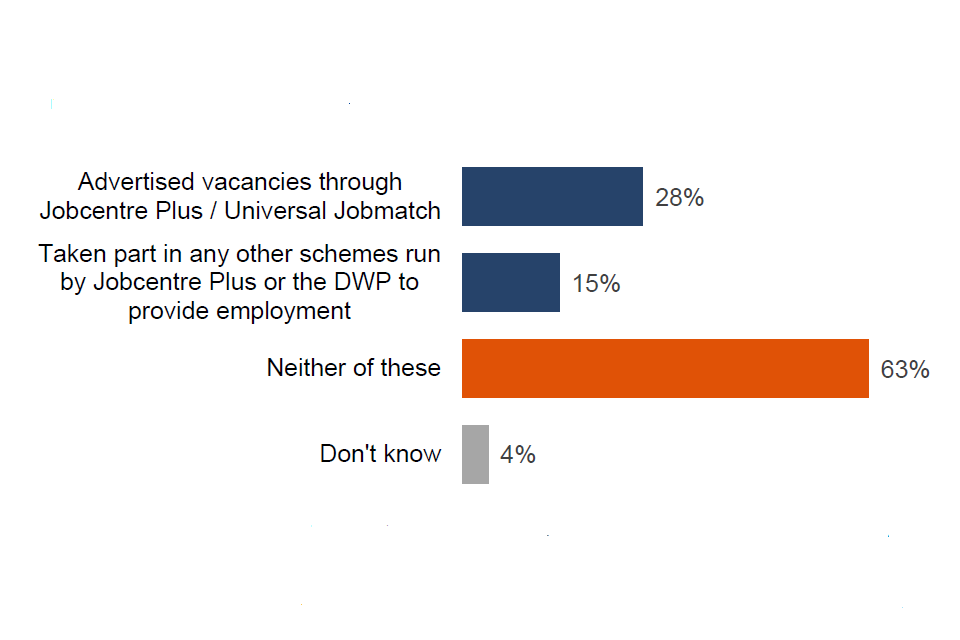

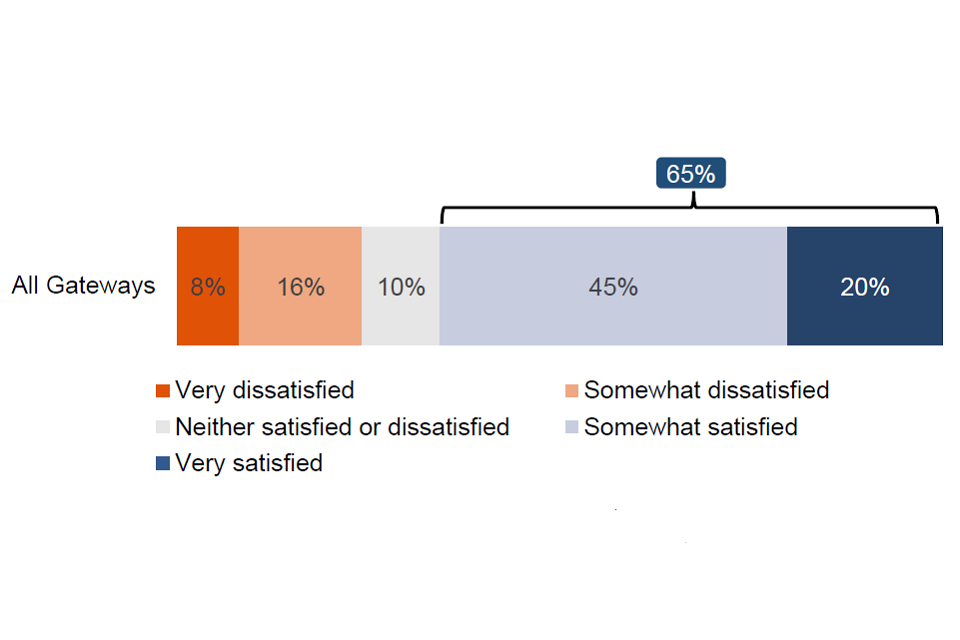

Overall, nearly three-quarters (73%) of employers were satisfied with their experience of Kickstart, even though many were new to this sort of scheme (63% had neither advertised vacancies through Jobcentre Plus / Universal Jobmatch or taken part in any schemes run by JCP or DWP to provide employment). Direct employers (those employers who had a grant agreement directly with DWP) were more likely to be satisfied with the scheme than Gateway organisation employers (GOEs, those employers who engaged in the scheme through a grant holding Gateway organisation) (77% compared to 71%).

In qualitative interviews, some employers described struggling with young people with poor workplace etiquette and low motivation, initiative, and confidence. Yet, employers often felt able to overcome these issues through open discussions and coaching. In some instances, usually among smaller organisations, employers found it difficult to support young people with mental health conditions.

Three-quarters (75%) of employers that had a young person complete the full six months, made at least one job offer to a young person. The volume of jobs offered versus taken up were broadly aligned, showing the majority of these offers were accepted.

Application and set-up

Gateway organisation employers (GOEs) tended to find the process of setting up as an employer via a gateway easy (74%), with many stating in qualitative interviews that the gateway ensured they were supported and informed throughout the process.

Overall, 71% of employers found it easy to get their Kickstart application approved and to demonstrate that they met the requirements.

Two-fifths (40%) of employers found the process of getting Kickstart jobs filled more difficult than expected; 18% found it easier than expected.

Being a GOE (as opposed to those employers who applied for and received grant funding directly from DWP, referred to as ‘direct employers’) was correlated with greater ease across all Kickstart processes, indicating that gateways may be having a positive influence on employers’ experiences:

- higher proportions of GOEs reported ease than direct employers in both the application itself (74% compared to 68%) and getting approved as a Kickstart employer (75% compared to 67%)

- GOEs were more likely than direct employers to have found getting Kickstart jobs approved easy (74% compared to 67%)

- GOEs cited greater ease in filling Kickstart vacancies; 20% of GOEs compared to 12% of direct employers found this element easier than expected

Many employers and gateways experienced a shortage of applications for Kickstart jobs. Three-in-five (60%) employers received too few applications and there was little variance in this proportion between different types of employers. In qualitative interviews, employers explained that poor engagement with the recruitment process (for example, not submitting a CV following application, not turning up to a scheduled interview) was an additional challenge. Employers and DWP Jobcentre staff collaborated to overcome these challenges in various ways, including attending job fairs, getting additional support from work coaches, and attending events where interviews could be done ‘on the spot’.

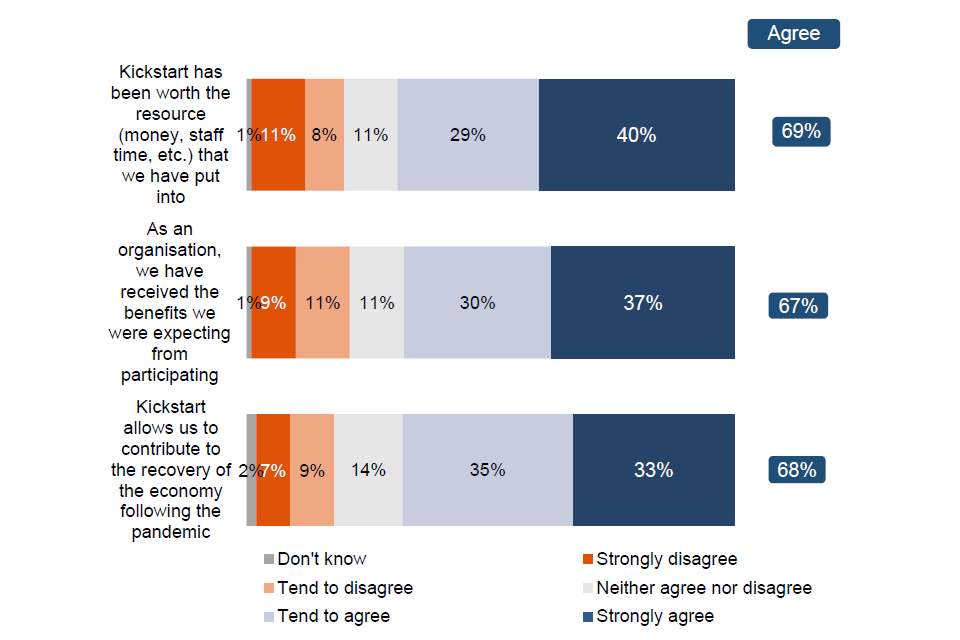

Did the Kickstart Scheme deliver its intended outcomes?

Evidence from this evaluation[footnote 7] suggests that the Kickstart Scheme delivered against its intended purpose. Most young people on Kickstart went on to employment, education, or training (EET). Although many felt they would have achieved an EET outcome in the absence of Kickstart, there are indications in the data and qualitative evidence that Kickstart provided young people with greater direction, experience, and confidence to take forward into future roles.

The extent to which the programme reached young people who were the furthest from the labour market can be questioned. For example, nearly half (46%) of Starters had a Level 3 or above qualification and three in ten (31%) already had more than twelve months paid work experience.

However, the Kickstart Scheme was created in the context of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic which had created new challenges for both young people and employers. Impacts on young people meant that even those who may not have previously struggled to find work found it challenging (due to limited pools of vacancies, at least through the initial months of the pandemic). While employers were less likely able to hire new staff, let alone staff that were new to the workforce and would require a lot of training and support. With this in mind, the scheme has worked well; it provided some innovative opportunities for both young people and employers that would not have been available otherwise. The scheme helped keep young people engaged in productive activity, mitigating against the negative impacts of prolonged unemployment in the challenging context of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic.

The Kickstart Scheme seems to have opened access to a wider range of opportunities (job roles, sectors, and employers), which hitherto had been difficult for young people to access. As reported above, a majority of employers had not advertised vacancies through JCP or Universal Jobmatch or taken part in any other schemes run by JCP or the DWP to provide employment prior to Kickstart. The new reach and positive experiences of employers on Kickstart has opened the pool of employers willing to help and support young people through work experience (for example, 74% would engage with a DWP employability scheme in the future). JCP now has a stronger base to develop this potential.

A requirement for Kickstart positions was that they offered additionality. This means, Kickstart employees should not have displaced another employee or taken the role away from a potential paid employee. Furthermore, the role should be adding economic value. Qualitative interviews with both employers and young people had varying — and often incorrect — understandings of additionality. Many viewed this as a requirement to create a job where the young person would be delivering completely new tasks for the business. There were varying degrees of additionality in the positions filled through Kickstart.

An added success of engagement with employers was the encouragement and adoption of more ‘flexible’ approaches to recruiting and supporting young people into work. A key part of this was gateways and JCP working with employers to ensure they understood the ethos of the scheme. This allowed employers to feel reassured about the recruitment approach and, more generally, by recruiting a Kickstart employee. Gateways and JCP also worked to improve challenges around employer expectations of Kickstart candidates. Initially, some employers had too high expectations in terms of qualification levels and amount of experience desired from candidates. With these employers, gateways and JCP staff explored how job opportunities could be adapted.

1. Introduction

The Kickstart Scheme was the government’s flagship employment programme to help young people in the wake of the economic downturn caused by the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. The scheme provided funding to create new six-month jobs for 16- to 24-year-olds on Universal Credit (UC) who were at risk of long-term unemployment. Employers of all sizes could apply for funding, which covered:

- 100% of the national minimum wage for 25 hours per week for a total of six months

- associated employer National Insurance contributions

- employer minimum automatic contributions

- £1,500 per position of additional funding to cover set-up costs, training, and employability support

Employers could pay Kickstart employees a higher wage and for more hours, but the funding did not cover this.

The Kickstart Scheme was initially planned to run between September 2020 and December 2021. In November 2021, it was announced that the scheme would be extended for a further three months, to March 2022. Employers could spread job start dates up until 31 March 2022. They received funding for six months once the young person had started their job.

The Kickstart Scheme was part of the Department for Work and Pension’s (DWP) Plan for Jobs: a range of government programmes, some of which offered financial incentives, available for employers who were considering hiring employees, offering work experience or the upskilling of existing staff. It was possible for a young person to move to another employment scheme when they finished their six-month Kickstart Scheme job.

Kickstart Scheme job role requirements

The jobs created with the Kickstart Scheme funding were required to be new, additional jobs. This meant, they must not replace existing or planned vacancies, or cause existing employees, apprentices, or contractors to lose work or reduce their working hours.

The jobs needed to:

- be a minimum of 25 hours per week, for six months

- pay at least the National Minimum Wage (NMW) or the National Living Wage (NLW) for the employee’s age group

- only require basic training

In each job, employers were required to help the young person become more employable. This support could include:

- looking for long-term work, including career advice and setting goals

- support with curriculum vitae (CV) and interview preparations

- developing their skills in the workplace

Role of gateway organisations

Gateway organisations acted as an intermediary to help employers manage their Kickstart Scheme grant.[footnote 8] Employers could either apply to the scheme via a gateway (these employers are referred to as gateway organisation employers, or ‘GOEs’) or apply directly online (‘direct employers’).

Essential responsibilities of a Kickstart gateway included ensuring the employer had the capacity and capability to support the Kickstart Scheme workers; and paying employers funding from the scheme.

In addition, gateways had the optional responsibility of offering employability support to young people on the scheme:

- sharing expertise with the employers to help them onboard and train young people employed through the scheme, for example supporting those from disadvantaged groups or working in certain sectors

- providing employability support directly to young people employed through the scheme

Where employability support was provided, the Kickstart gateway and employer needed to agree on how this was done. Gateways were able to offer employability support to an employer outside of their grant agreement should they wish.

Gateway Plus

A Gateway Plus was a specific type of Kickstart gateway. They helped smaller organisations, such as sole traders, with the Kickstart Scheme.

Alongside the essential responsibilities of a Kickstart gateway, they also:

- added the young person to their own organisation’s payroll

- paid the young person’s wages on the small employer’s behalf using the funding from DWP

- provided the employability support on the small employer’s behalf

A very small number of organisations signed up to be a Gateway Plus.

Additional employability funding

Further to the wage and contributions, £1,500 of additional funding was available for training and support to make it more likely that young people on the scheme would get a job in the future. It was intended that this fund would be spent on set-up costs and supporting the young person to develop their employability skills. For example:

- training and employability support (provided by the employer, a Kickstart gateway, or another provider)

- IT equipment and software

- uniform or Personal Protective Equipment

For GOEs, this funding was paid via their gateway organisation. The structure of this additional payment was decided by the gateway and employer as the service provided could vary (for example the employability support might be provided by the employer or the gateway). DWP could ask gateways and employers for records to show that the funding had been spent as intended.

More details about the scheme can be found on the government’s website about the Kickstart Scheme.

Overview of the research objectives

The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) commissioned IFF Research to conduct an evaluation of effectiveness of the Kickstart Scheme as a means of supporting young people during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and preventing them from becoming long-term unemployed. The study aimed to evaluate:

- outcomes for Kickstart participants after they finished their Kickstart job

- what Kickstart was like, as experienced by participants

- what benefits were gained in terms of personal, employability and vocational skills through the Kickstart job

- how the experience contributed to longer-term employment/career aspirations

- what additional support young people might need

- whether there have been any negative or unintended outcomes from taking part

- whether, and how, experiences and outcomes differ for different groups

Methodology

This evaluation involved both quantitative (survey) and qualitative (case study) strands with multiple audiences.

IFF Research conducted all quantitative fieldwork, and they conducted the qualitative fieldwork with the support of Professor Sue Maguire (Institute for Policy Research, University of Bath), on behalf of the DWP.

Data for all audiences have been weighted to reflect the population characteristics.

Survey fieldwork

Three audiences took part in the surveys: young people who participated in Kickstart, gateways, and employers.

Young people surveys

Interviews with young people who participated in Kickstart took place approximately:

- 1-to-3 months after they started a Kickstart job (‘Starters’)

- seven months after they started a Kickstart job (‘Leavers at seven months’)

- a follow-up survey with those that took part in the Leavers at seven months survey, ten months after they started a Kickstart job, so three months after completing ‘Leavers’ at seven months’ survey (‘Leavers at ten months’)

IFF Research conducted fieldwork in monthly ‘waves’ by sending out an online survey link to Starters (seven waves, between November 2021 and March 2022) and Leavers at seven and then ten months (both twelve waves, Leavers at seven months in field between November 2021 and October 2022, and Leavers at ten months in field between February 2022 and January 2023). Leavers at ten months who did not complete online were then invited to take part via telephone. The surveys took around 10-15 minutes to complete.

The total numbers of interviews achieved were:

- starters: 8,063 at a response rate of 17.8%

- leavers at seven months: 11,665 at 16.8%

- leavers at ten months: 3.396 at 40.8%

All cohorts included those who started Kickstart jobs but left early.

Coverage of young people’s surveys

The Starters’ survey focused on young people’s background and experience prior to starting their Kickstart job as well as the process of applying to their Kickstart role. It also asked about their current Kickstart role and future career aspirations.

The Leavers’ survey at seven months focused primarily on young people’s overall experience with the Kickstart Scheme and the specifics of their Kickstart roles. It also asked about skills and career aspirations.

The Leavers’ survey at ten months followed up on their experiences, including their thoughts and feelings towards their current situation and career aspirations.

Employer and gateway surveys

IFF Research conducted the employer survey among employers at least six months after they first employed young people via Kickstart. The survey included both direct employers and GOEs. The gateway survey was an attempted census, all gateways on record were invited to complete it.

The total numbers of interviews achieved were:

- direct employers: 520 interviews at a response rate of 31%

- GOEs: 462 interviews at a response rate of 33%

- Gateways: 401 interviews at a response rate of 35%

There were two waves of surveys with employers and gateways. The first, in February 2022, The second, in July 2022.

Coverage of employer and gateway surveys

Both surveys covered signing up to Kickstart, offering Kickstart jobs, providing support to young people, and overall views of Kickstart. In addition, GOEs were asked about their experience of working with a gateway.

Case studies

IFF Research, with support from Professor Sue Maguire, carried out a total of 12 case studies. These were in a mix of Kickstart districts across England, Wales, and Scotland including rural, urban, and mixed rural/urban locations. The case studies involved interviews and focus groups with a range of Kickstart employers, gateways, and Jobcentre Plus (JCP) staff involved in delivery of the scheme. It also included qualitative research with young people, which comprised of a five-day online diary and follow-up interview about their experiences of the scheme approximately three to four months into their Kickstart job. As it was intended to capture ‘a week in the life’ of someone in Kickstart job, young people who had left their Kickstart job early were not included in online diaries. A small minority of young people left their Kickstart role early between their online diary and follow-up diary. This means qualitative insights from young people who left Kickstart early are very limited.

All qualitative fieldwork took place between December 2021 and June 2022.

About this report

This report aims to inform DWP about the experiences of staff and participants involved in the scheme to date, reflect on whether intended outcomes were being achieved, and highlight what worked well or less well, with implications for future programmes in mind.

Throughout this report only statistically significant findings are reported between sub-groups — please note that it is not possible to infer causation from these, only that they are correlated.

Structure of subsequent sections of this report:

Chapter 2 describes the experience of Kickstart implementation from the perspective of JCP staff, gateways, and employers.

Chapter 3 describes the profile of young people who participated in Kickstart and why they chose to be involved.

Chapter 4 explores experiences of the Kickstart Scheme, first presenting young people’s experiences before looking at employer and gateway perspectives.

Chapter 5 presents the early outcomes young people participating in the Kickstart Scheme have experienced.

Chapter 6 concludes the findings of the research, exploring the extent to which the intended outcomes have been achieved, and key learnings for future programmes.

2. Implementation of the Kickstart Scheme

This chapter describes views of Jobcentre Plus (JCP) staff, gateways, and employers about Kickstart implementation and the experience of signing up and recruiting young people onto jobs.

Summary

Jobcentre Plus (JCP) staff viewed Kickstart as a good fit with existing provision for young people, particularly in England. JCP staff, employers, and gateways all reported some problems in the early stages of the scheme, particularly around trying to get responses from the DWP about how to run the scheme. Although they recognised the challenges of starting the scheme quickly, most staff agreed that launching in this manner and resolving issues as they emerged had been the right course of action.

Over half (56%) of gateways felt the time between submitting an employer application and hearing back from DWP was not reasonable. Three-in-ten (29%) felt it was reasonable.

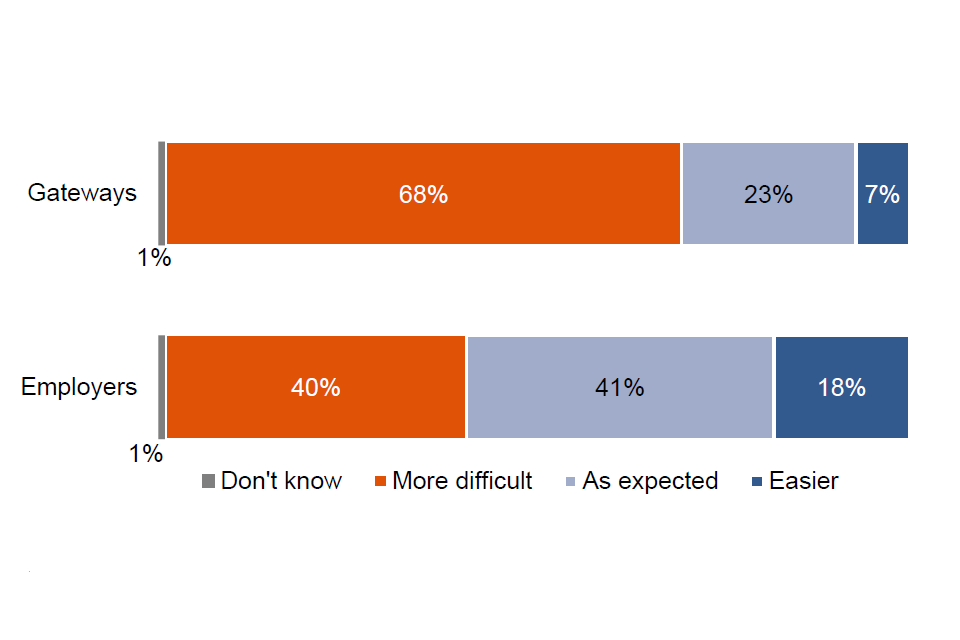

Over two-thirds of gateways (68%) found filling their employers’ Kickstart vacancies more difficult than they had expected. Among employers, two-in-five (40%) found the recruitment process for their Kickstart jobs more difficult than expected. Employers were more likely than gateways to have found the process of filling their vacancies ‘as expected’ (41% compared to 23% of gateways), and one-in-five employers (18%) found it easier than expected.

Gateways and JCP staff reported some challenges around managing employer expectations of Kickstart candidates. The most reported problem was employer expectations being too high in terms of qualification levels and amount of experience desired.

Employers, overall, felt there were not enough young people applying for the jobs. Three-in-five employers (60%) reported they received too few applications for each Kickstart vacancy, while a third (34%) received about the right number.

In the qualitative interviews, employers also reported that young people varied in their engagement with applying for a vacancy, and that low engagement could make jobs more challenging to fill. Examples of this included young people not submitting a CV after having been referred to a vacancy by a JCP work coach or not turning up for a scheduled job interview.

Employers overcame these challenges in a variety of ways, including: attending job fairs; receiving additional support from work coaches (for example, to arrange meetings with suitable candidates); attending JCP events with employers and young people, where interviews could be done ‘on the spot’ and jobs offered immediately.

Profile of employers who participated in Kickstart

Employers

Almost half of the employers who participated in Kickstart (46%) had under 10 employees[footnote 9] (excluding those taken on as part of the scheme). The scheme had also engaged larger organisations: a third of employers (34%) had between 10 and 49 employees; 11% had 50-to-249; 9% had 250 or more.

Direct employers were more likely to be large organisations (18% had 250 or more employees compared to 3% of GOEs. Half (53%) of GOEs had under ten employees compared to a third (35%) of direct employers. This indicates that smaller employers tended to access the scheme via gateways, which was the intention at the outset of the scheme.

Among participating private sector employers, a third (34%) had a turnover of no more than £250,000 in the UK in the previous financial year. However, just over a fifth (22%) had a turnover of over £1 million. The high proportion of employers who did not disclose their turnover (20%) to the evaluation makes analysis less straightforward. Of those who did disclose their turnover, 43% reported a turnover of no more than £250,000 and 27% reported a turnover of over £1 million.

Three-quarters (75%) of employers who participated in Kickstart were in the private sector, 20% were in the third sector and 4% were in the public sector. Compared to the profile of all organisations in the UK, private sector businesses were underrepresented among Kickstart employers (making up 96% of the wider business population) with third sector and public sector overrepresented (comprising 3% and 0.5% of the wider business population respectively).[footnote 10] GOEs were less likely than direct employers to be in the public sector (3% versus 7%).

Kickstart had employers across a range of sectors. Overall, the most common sectors were ‘health and social work’[footnote 11] (16%), ‘professional, scientific and technical’[footnote 12] (11%), ‘education’[footnote 13] (10%), ‘manufacturing’[footnote 14] (10%), and ‘wholesale and retail’[footnote 15] (9%). The breadth of sectors reached was similar for both grant types, the majority of both direct employers (59%) and GOEs (54%) were in these five sectors.

Direct employers were more likely to be in the ‘health and social work’ or ‘education’ sectors (19% and 13% respectively compared to 13% and 9% of GOEs). Gateways appeared to have been more successful at engaging employers in the ‘information and communication’ sector (7% of GOEs versus 3% of direct employers).

Kickstart employers were based across Great Britain, as were young people on the scheme. Employers were most often based in the more populous South East (16%) and London (15%), and these were the most common regions where employers had Kickstart employees working (18% and 17% respectively). Employers were less likely to be based in the East of England (4%) and the North East (5%), and these were the regions where employers were less likely to have had Kickstart workers (each 7%).

Perceptions and experiences of Jobcentre Plus staff

Response to the introduction of Kickstart

Jobcentre Plus (JCP) staff viewed Kickstart as a good fit with existing provision for young people, particularly in England.

We asked JCP delivery staff, employers, and representatives from gateways to comment on how Kickstart fitted in with other provision available to young job seekers across their localities. Kickstart was reported to be unique in that it:

- was implemented at a time when there was an acute shortage of labour market opportunities due to the pandemic

- was targeted solely at young people

- offered paid and supported work experience, as opposed to intensive job-search support and/or job and is available to all groups of Universal Credit young claimants, regardless of their proximity to the labour market

While the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) staff mentioned programmes such as JETS (Job Entry Targeted Support) and the Work and Health Programme as alternative interventions, it was emphasised that these programmes focus on a wider age catchment with an emphasis on supporting harder to help/reach groups. Moreover, it was asserted that, while there was adequate education and training provision available in most localities, access to paid and supported work experience opportunities was much more limited.

JCP staff also noted that Kickstart helped to support the local economy. The scheme was seen as particularly beneficial to small companies that were significantly impacted by the pandemic. Such companies were seen as less likely to be able to independently afford to hire new staff, so having a young person as an ‘extra pair of hands’ benefitted both the employer and the young person.

Preparing for Kickstart and initial implementation

Only a minority of the JCP staff interviewed were involved from its inception — many moved into their Kickstart roles after the scheme had started. Consequently, the rest of this section reports findings from a smaller pool of respondents. Of the staff who were involved in implementing the scheme, three common challenges were reported, although not universally consistent across areas.

The first of these was the time between the initial announcement of Kickstart in July 2020 and its implementation just two months later. This speed of implementation was felt to be necessary to address the workforce challenges created by the global Coronavirus pandemic. That said, it meant that staff felt rushed to understand and implement the scheme.

The second was perceived lack of clear guidance from central teams about exactly how the regional and local JCP staff should implement and run Kickstart. ‘Lack of processes’ was identified as an issue across many case study areas.

Thirdly, staff reported that the scheme grew more quickly than anticipated, so the initial number of staff allocated to the scheme (both centrally and at a local level) was insufficient to meet the resource demands, and others had to be quickly recruited to new roles.

Taken together, these three challenges meant that the scheme did not initially run as efficiently as it did later. However, staff generally acknowledged that the extraordinary circumstances of the pandemic created a need for swift action and that there had been little time to plan the scheme more extensively and in more detail. Across all job roles there was general agreement that, despite a steep initial learning curve, their understanding quickly improved, processes were put in place, and the scheme then ran more smoothly.

Recruiting employers and gateways

Across Kickstart areas, JCP staff (predominantly KDAMs) described a similar process for recruiting both employers and gateways. The process was often described as two-way, with some employers / gateway organisations proactively approaching JCP staff and vice versa. No substantial differences were reported in methods of recruiting employers versus gateways, so these are detailed together.

In terms of initial engagement, KDAMs generally reported initially reaching out to employers and relevant organisations (for example, Chambers of Commerce and local authorities) with whom they had good existing relationships. These early discussions focused on explaining the scheme, particularly the additionality requirement for all jobs, to gain buy-in.

For employers and gateways with which JCP staff had no prior relationship, staff utilised multiple methods of engagement. No single method was reported to be successful, but rather a range of approaches was felt to be key. Examples included:

- giving talks to local organisations (for example, local councils) to target as wide an audience as possible

- in-person employer events

- snowballing and networking — referrals through word of mouth

- setting up Twitter events, including gathering questions in advance and tweeting answers within the event

- setting up a webinar for employers/gateways to attend, so staff could explain Kickstart and answer general enquiries (this method was referenced by only one respondent and not reported as having been highly attended)

- advertising via LinkedIn or social media

- local recruitment/marketing campaigns (for example, local radio)

- sending posters and leaflets to local employers and potential gateway organisations

This local targeting and engagement activity was supplemented by national advertising activity and public relations. For example, there was a national communications and public relations campaign via press and social media.

Initial Employer Engagement

Gateways’ experience of recruiting employers onto scheme

Three quarters (76%) of gateways found it easy to identify employers who wanted to offer Kickstart jobs.

The average number of employers that gateways supported was 80. Nearly two-in-ten (18%) had supported between one to nine employers, and a quarter (25%) had supported between 10 to 29 employers.

Gateways in the private sector were more likely to report having supported a higher number of employers: an average of 104 (compared to an average of 77 for gateways in central or local government and an average of 63 for gateways in the third sector).

Employers’ Initial Concerns Related to Kickstart

Before taking part in the scheme, three-in-five employers (63%) were concerned about how prepared the young people would be for work. Some had concerns about the application process, including the period between signing up to Kickstart and a Kickstart job starting (30%) and the likelihood of getting approved for the scheme (24%).

A smaller proportion had concerns relating to what they would be able to provide to the young people that would be given the Kickstart jobs. Nearly a quarter (23%) were concerned about having enough capacity to develop young people’s employability skills, while over one-in-ten (13%) were concerned about having enough work to give to young people in the jobs. Gateway organisation employers (GOEs) were more likely to be concerned about having capacity to develop employability skills (26% versus 17% of direct employers).

Motivations to becoming a Kickstart employer

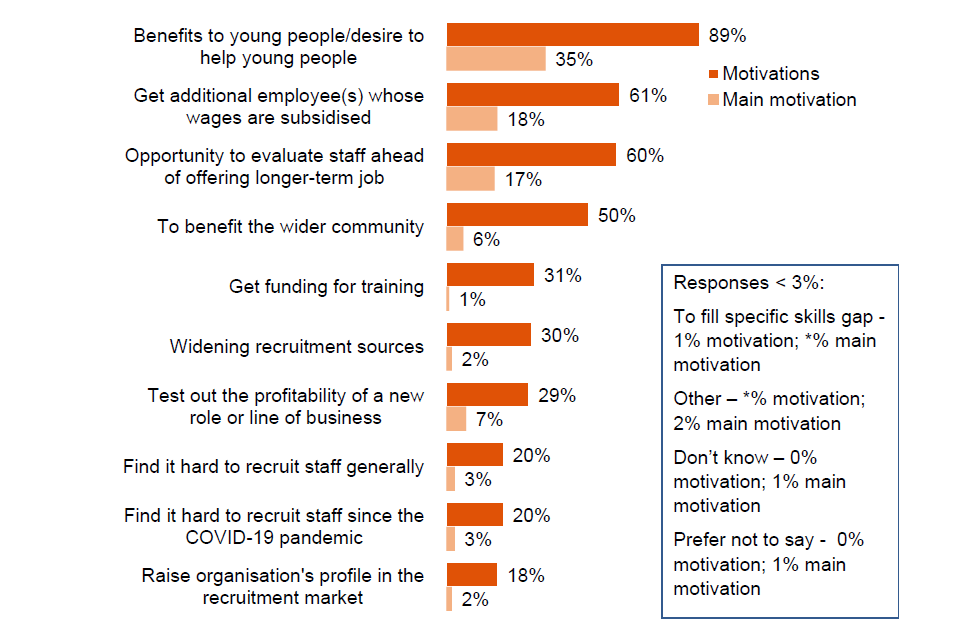

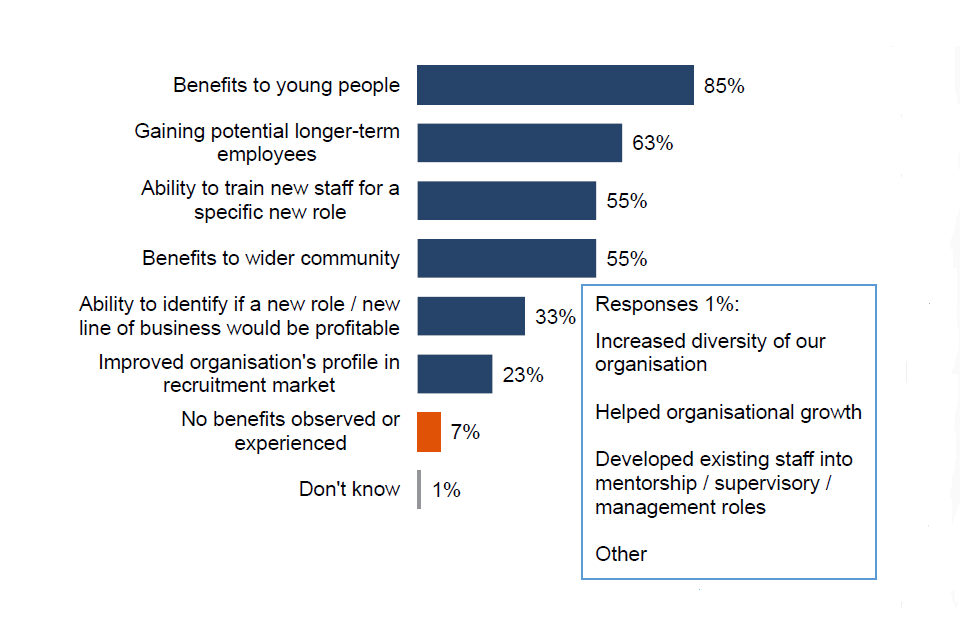

The most commonly reported motivation for employers to sign up to Kickstart was being able to benefit young people. This was reported by nine-in-ten (89%) employers (Figure 2.1). Benefitting young people was also most commonly considered to be the main motivation (35%). Half of employers (50%) reported being motivated by the potential benefits to the community.

Employers were also commonly motivated by factors that would benefit their organisation. Four-in-five reported being motivated by the addition of subsidised employees (61%) and the opportunity to evaluate staff before offering them a job (60%).

Motivations for joining the scheme varied according to the size of employer. Larger employers were more likely to be motivated by benefits to others outside their organisation, medium employers by the chance to evaluate staff in a role, and smaller employers by gaining subsidised staff.

Figure 2.1 What motivated your organisation to sign up to Kickstart?

A2. What motivated your organisation to sign up to Kickstart? / A2A-All. And which was your main motivation? Base: All employers (1,008).

Setting up with a gateway

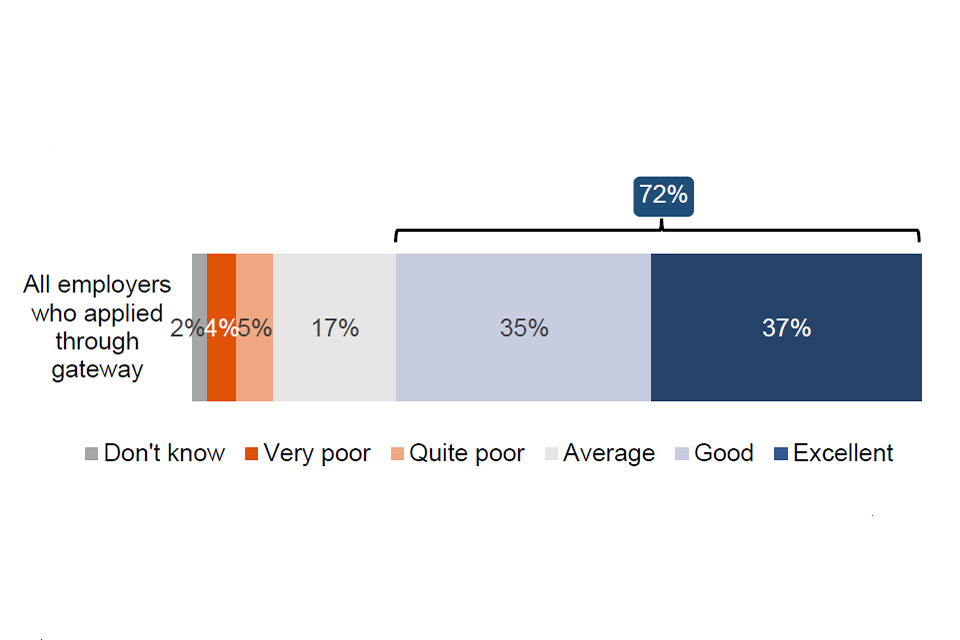

Among employers that applied through a gateway, the majority found it easy (74%). Less than one in ten employers who applied through a gateway found the process difficult (10%).

Application and approval process

Applying directly or via a gateway

The majority of employers who took part in qualitative interviews applied to the Kickstart Scheme directly rather than applying via a gateway. Employers who applied directly reported three main reasons for doing so:

1. Having more control over the process 2. Assumption that the process would happen more quickly without a ’middleman’ 3. Receiving more of the available funding In making the applications, gateways were more likely to have found it difficult (42%) to get employer applications approved than to have found it easy (38%). Almost a fifth (18%) found getting employer applications approved very difficult.

Gateways that supported a larger number of employers were more likely to have found it difficult getting employer applications approved. Over half (56%) of gateways that supported 100 or more employers found getting employer applications approved difficult compared to only 38% of those supporting fewer than 100. It is likely that because they made a higher number of applications, they were more likely to encounter difficult scenarios.

Employers, in contrast to gateways, were more likely to report their application process was easy than difficult. Overall, 71% of employers found getting their application approved or showing that they met the scheme requirements easy and 14% found it difficult.

Among GOEs, 75% found getting their employer application approved easy (compared to 67% of direct employers). This suggests that gateways had some level of influence on the ease of the process and likelihood to get approved.

Fifty-six per cent of gateways felt the time between submitting an employer application and hearing back from DWP was unreasonable, with 29% feeling it was reasonable.

Rejections of employer applications

Only around a tenth (11%) of gateways had all their employer applications approved first time, the remainder had received at least one rejection. Three-in-ten (30%) gateways had over 90% of their employer applications accepted first time, but 14% had less than half accepted first time and 2% had none accepted initially.

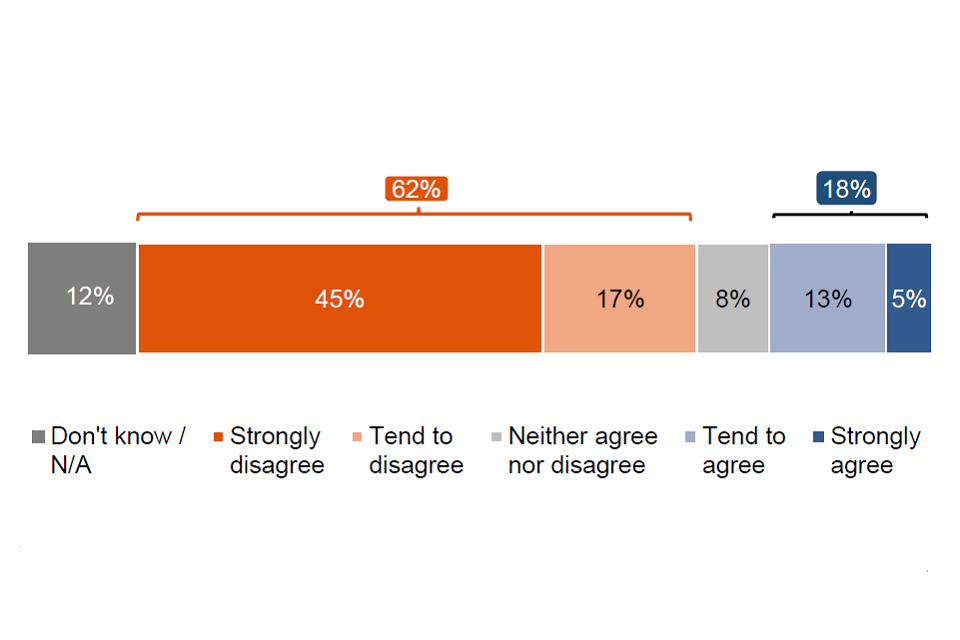

Among the gateways who had not had all their employer applications accepted, most (62%) felt the reasons given for rejection were not valid, as shown in Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2 Whether gateways agreed that rejections of employer applications were for valid reasons

A14_2. To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements? When employer applications are rejected, the reasons given for rejection are valid. Base: gateways who had employer applications rejected (340).

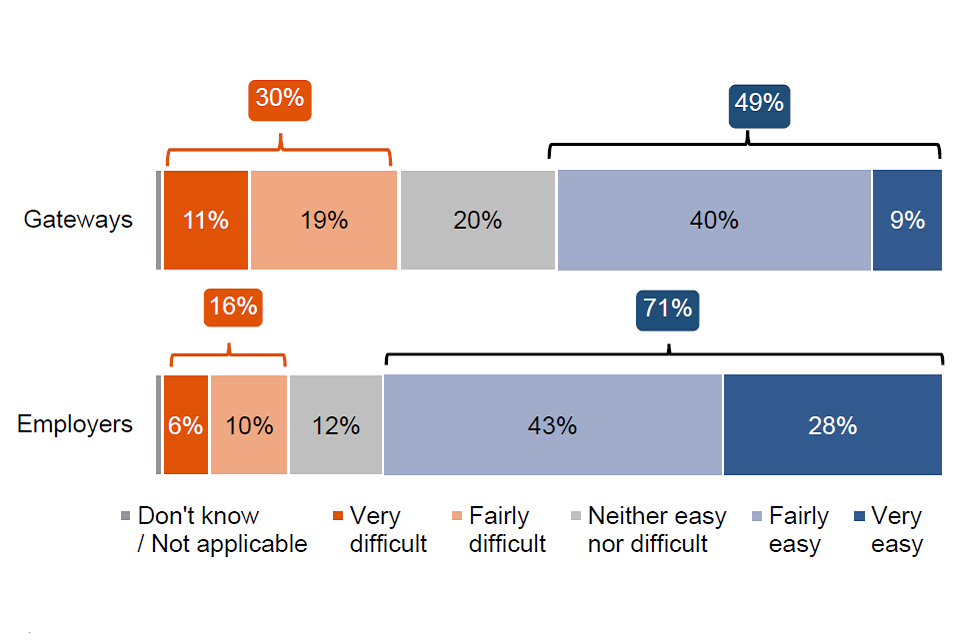

Kickstart job approval

Both employers and gateways were more likely to have found getting Kickstart jobs approved easy (71% and 49% respectively) than difficult (16% and 30% respectively). Gateways found getting Kickstart jobs approved more difficult than employers, as shown in Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3 Whether gateways and employers found it easy or difficult to get Kickstart jobs approved

A9_3. How easy or difficult do you find the following? Getting Kickstart jobs approved. Base: All gateways (401) / A4_5. How easy or difficult did you find the following? Getting your Kickstart job(s) approved. Base: All employers (1,008).

Gateways who supported more employers were more likely to find getting jobs approved difficult (mirroring their higher likelihood of difficulties with employer applications). Half of gateways (50%) who had filled 250 vacancies or more found getting jobs approved difficult compared to 29% of those who had filled fewer than 30 vacancies. Similarly, the more vacancies employers had filled the more likely they were to have found getting them approved difficult (28% of those who filled 26 or more compared to 11% who filled one). This appears to indicate the issues were not due to misunderstanding the process or requirements the first time, but in perhaps trying to get a wider range of jobs approved. GOEs were more likely than direct employers to have found it easy (74% compared to 67%), suggesting that gateways were successful in their role as a support for employers.

Gateways were more likely to disagree (49%) that the time between submitting Kickstart jobs for approval and receiving a response from DWP was reasonable than to agree (36%). Over a fifth (22%) of gateways ‘strongly disagreed’ that the DWP response time was reasonable. This was similar to, but a little less negative than, views about response times on employer applications.

Rejections of Kickstart jobs

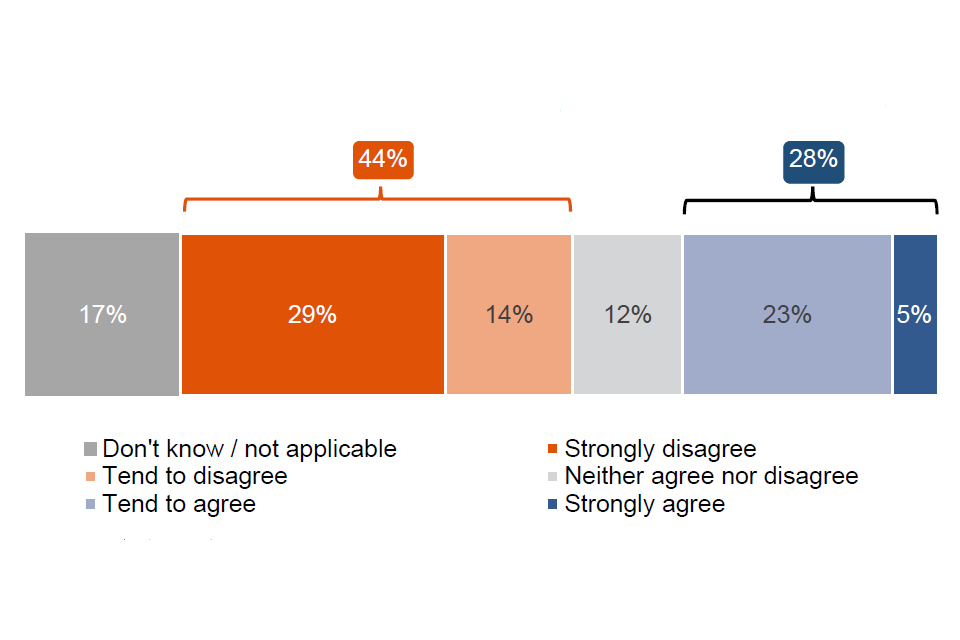

A quarter (26%) of gateways had all their Kickstart jobs approved first time, and almost half (47%) had nearly all[footnote 16] of their jobs accepted first time. However, seven in ten (69%) gateways had received at least one rejection.

Among gateways who had Kickstart jobs rejected, more disagreed that the reasons for rejection were valid (44%) than agreed (28%), as shown in Figure 2.4.

Figure 2.4 Whether gateways agreed that rejections of Kickstart jobs were for valid reasons

A14_4. To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements? When Kickstart jobs are rejected, the reasons given for rejection are valid. Base: gateways who had employer jobs rejected (279).

Lack of communication was the main reason for gateways feeling rejections were not valid. Of the 55% of gateways that had employer applications or Kickstart jobs rejected for what they felt were invalid reasons, 62% reported this was because they were not given any reasons for the rejection and 60% that they were given insufficient detail. Feeling that the rejection was wrong, invalid, or incorrect was reported by 7% of those who thought rejection reasons were invalid.

JCP staff, who had a good overview of the submission process, discussed in the qualitative research why some vacancies were initially rejected by DWP. Three main reasons were offered: 1) The vacancy was poorly worded (for example, misleading or inaccessible); 2) the vacancy did not offer employability support; 3) The vacancy was not seen as additional — for example, a low ratio of permanent job roles compared to Kickstart vacancies, suggesting that the Kickstart vacancies were taking the place of permanent roles rather than being additional. Both JCP staff and gateways reported helping employers to correct these where possible, so the second time a vacancy was submitted it was more likely to be accepted by the DWP.

Some gateways commented that the inability to create more vacancies[footnote 17] (if current vacancies were not filled) had impacted negatively on attracting the types of vacancies that young people want. For example, if there was a large number of care positions entered into the system that were not filled (a sector with existing labour shortages), then there was not the scope to add further vacancies in a more popular sector, for example, construction.

Offering and recruiting vacancies

Filling Kickstart jobs

Number of Kickstart jobs filled

A quarter (26%) of gateways had agreed 250 or more Kickstart jobs and almost a further quarter (23%) had agreed between 100-249 jobs.

On average, gateways reported 88% of agreed job vacancies had been advertised, and half of gateways (50%) had advertised all agreed vacancies.

On average, gateways reported over half (56%) of agreed vacancies had been filled. A small minority (3%) of gateways reported all their agreed vacancies had been filled, a quarter (24%) had filled at least 70%. However, a third of gateways (34%) had filled less than half their agreed vacancies.

Turning to employers, they had an average of nine jobs approved and an average of six jobs filled. Overall, on average employers had 82% of their approved jobs filled.[footnote 18]

Direct employers were more likely to have filled more vacancies; 28% had filled more than five compared to 13% of GOEs. Two-fifths (39%) of GOEs had filled one job vacancy, compared to only 23% of direct employers. However, GOEs were more likely to have filled a higher proportion of their jobs: 61% had filled all agreed vacancies.

Factors considered when filling vacancies

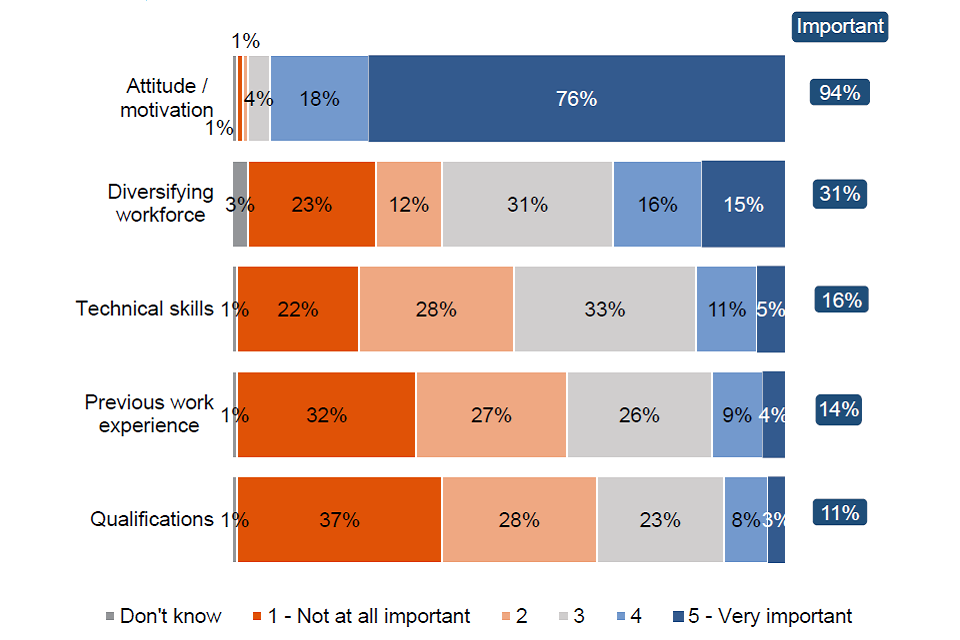

For nearly all employers (94%), a candidate’s attitude or level of motivation was an important factor when selecting Kickstart employees. All other factors asked about were far less likely to be regarded as important, as shown by Figure 2.5.

Diversifying the workforce was the second of the listed factors most likely to be important when selecting young people (31% of employers). It was more likely to be important for public or third sector employees (37% compared to 29% of those in the private sector).

Figure 2.5 Relative importance of listed factors when appointing young people for Kickstart vacancies (for employers)

B6. How important were each of the following factors when deciding which candidate to appoint to a Kickstart job vacancy? As listed. Base: All employers (1,008).

Challenges with filling Kickstart jobs

How easy or challenging it was to fill Kickstart roles greatly varied. This depended on a variety of factors including sector, type of job, location of job, local labour market needs, existing skills gaps, and employer expectations.

Over two-thirds of gateways (68%) found getting their employers Kickstart jobs filled more difficult than they had expected (Figure 2.6). A smaller proportion of employers (40%) reported the same, and a similar proportion found the process of filling their vacancies ‘as expected’, 41% (compared to 23% of gateways).

Figure 2.6 Gateways and employers’ experience of getting Kickstart jobs filled compared to their expectations

B5. How did the ease or difficulty of getting your employers’ Kickstart jobs filled compare to expectations? Base: All gateways (401). / B2 How does your organisation’s experience of the process of recruiting your Kickstart young people to job(s) compare to expectations? Base: All employers (1,008).

Difficulty filling vacancies did not appear to vary by the number filled. However, the more employers that a gateway supported, the more likely they were to have found getting jobs filled difficult (77% of those who supported 100 or more, compared to 56% who supported fewer than ten).

A lack of candidates was the most common reason for difficulty (for 79% of gateways that found it more difficult to fill Kickstart jobs than expected). Poor quality candidates were also an issue for around half (52%).

Some employers reported challenges related to DWP, but these were mainly relating to earlier stages of the process as reported above GOEs were more likely to have found recruitment for their Kickstart jobs easier than expected (20% versus 12% of direct employers), suggesting that the gateways successfully supported GOEs in this.

The following types of employers were more likely to have found the recruitment process more difficult than expected:

- larger employers (56% of those with 250 or more paid employees compared to 39% of smaller employers)

- public or third sector (45% compared to 38% of those in the private sector)

- filled a higher number of vacancies (53% of those who had filled more than 25 compared to 36% who had filled one)

The relationship between having a higher number of vacancies and finding the process difficult again indicates that difficulties did not appear to be due to “teething” issues that were ironed out over time. This contrasts to gateways, where there was little difference in views by number of vacancies filled.

Among the 40% of employers who had found it more difficult than expected to recruit young people to Kickstart jobs, the most common spontaneously reported difficulties were around the supply of young people: finding suitable candidates (31%) or too few referrals (16%). Some employers were of the perception that young people did not want the work, including not attending interviews or responding to job offers (27%). Too few referrals making applications (11%) may also indicate that demand from young people was higher than the number of jobs available or that the jobs on offer did not meet the expectations of young people.

Another theme for some employers was difficulty with the process, central operational DWP, or JCP staff. This included employers feeling work coaches were: not actively promoting the vacancies or sending unsuitable candidates (16%); a lack of support from DWP (9%); problems communicating with DWP (9%); and the timeframe, delays, or length of the process (8%).

In terms of the time taken, for half (49%) of employers, it took longer than a month to fill their Kickstart vacancies on average. Half of employers (49%) reported that the time taken was as expected, but it was longer than expected for 38%.

Quality and quantity of candidates

Among employers who found recruitment difficult, GOEs were more likely to report difficulties finding suitable candidates (35% versus 23% of direct employers). This was possibly linked to having less control over the process.

Gateways and JCP staff reported some challenges around managing employer expectations of Kickstart candidates. Typically, the main reported problem was employer expectations being too high in terms of qualification levels and amount of experience desired. For example, some JCP staff reported that employers looking to recruit for roles in construction often wanted unrealistic amounts of experience from applicants. Requiring candidates to have a driving license was a commonly referenced stumbling block.

Gateways commented that the scheme was most successful when employers were able to look past their usual CV criteria when considering a young person for a Kickstart role. Examples of this included relaxing the typical minimum educational grades or previous work experience. When employers were able to adapt more ‘traditional’ recruitment process, for example replacing them with approaches such as employer ‘speed dating’, it exposed them to a wider range of potential candidates. In many cases, employers needed some encouragement to do this. It was usually achieved by Jobcentre staff presenting the scheme as also aiming to help the young person gain useful skills and experience, rather than just meeting their labour needs.

Some Jobcentre staff thought that matching young people to vacancies would have been easier if job creation had been targeted toward roles and sectors that matched young people’s interests, rather than being driven primarily by employers’ labour demand.

The Department for Work and Pensions] should have placed greater focus in the planning stage on identifying from young people what they wanted from the programme in terms of work experience placements. Instead, they focused the marketing on identifying employers’ needs - in hindsight, it should have been a better balance. Young people apply for what is available from employers.

(KDAM, Urban area)

In the qualitative interviews, JCP staff also felt that they needed to work to get employers to adapt their job descriptions for applicants with less confidence or lower qualifications.

Initially, they saw it as just another job opportunity…. We needed to get through that this is somebody to add value, that we can invest in for six months, and you can get some value to your company. So, you can take any young person on as long as they’ve got the potential and the right attitude.

(District-level JCP staff, Urban area)

However, both gateways and JCP staff were able to overcome these challenges by taking the time to clearly explain the scheme to employers who initially held unrealistic expectations. After these employers understood that Kickstart was not simply a quick/cheap recruitment solution, and that helping to develop the young person was a key part of the scheme’s ethos, their expectations became more realistic, and they became more accommodating in terms of their requirements for Kickstart roles.

Gateways and JCP staff also emphasised that Kickstart could act as an affordable way for a small business to trial a potential employee who may eventually be kept on in a permanent role and encouraged employers to take risks on young people they may not otherwise have considered. After understanding this, these employers become more willing to adapt roles to account for lower qualifications and experience.

Despite these interventions, employers, overall, felt there were not enough young people applying for the jobs. Most employers (60%) reported that they received too few applications for each Kickstart vacancy, while a third (34%) received about the right number.

3. Engaging young people in Kickstart

This chapter describes the profile of young people who participated in Kickstart and why they chose to be involved. It explores the application process for Kickstart jobs from the perspective of young people, including any challenges and support needed.

Summary

Kickstart reached a wide spectrum of young people. A third (34%) were long-term Universal Credit (UC) claimants (over 18 months) and a similar proportion (35%) were short-term (six months or less) claimants. Almost a quarter had no prior experience of paid work at all. A quarter were qualified at Level 4 or above, but one in five had a Level 1 qualification or no qualifications at all.

Many young people had been struggling with their job search prior to being involved with Kickstart, finding it very difficult to find vacancies that interested them but did not require work experience that they did not have. By comparison, searching for Kickstart jobs often felt different because the adverts were more accessible, employers did not require experience and they were more willing to provide training.

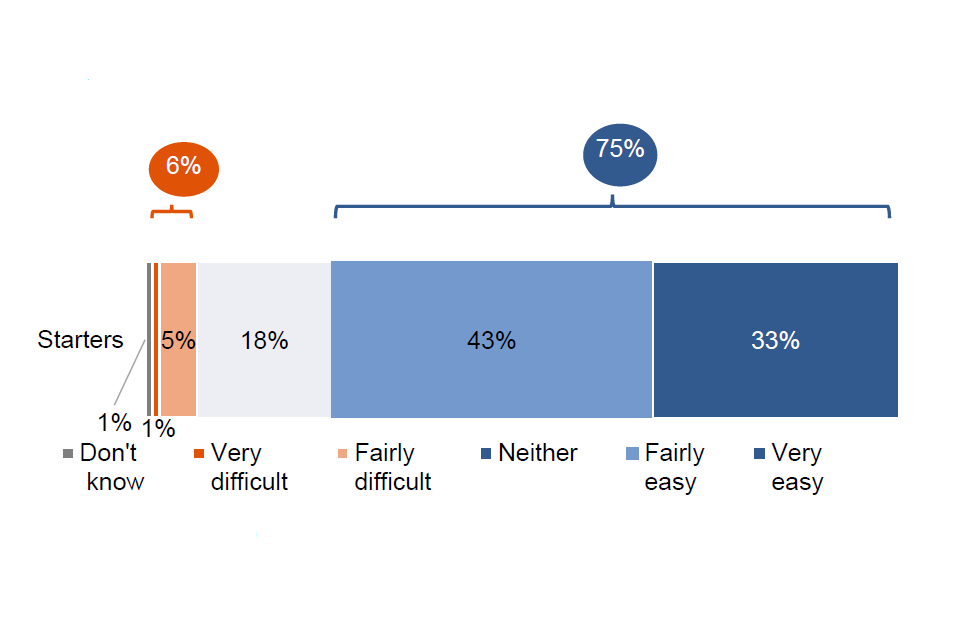

Most young people found the application process for Kickstart jobs easy (75%).

Employers were often very flexible in terms of adapting their recruitment approaches to make them more accessible to young people including through more informal interviewing approaches. Jobcentre Plus staff often mentioned having to work with employers to encourage this.

Jobcentre staff felt that the longer appointments that they could offer under Kickstart were valuable in helping them support young people and give them the confidence to apply for the scheme.

Characteristics of young people on Kickstart

Demographic profile of young people[footnote 19]

Gender, age and ethnicity

Just over half of Starters described themselves as male (53%), 45% as female. Half of Starters were aged 18-to-21 (50%) with almost all other Starters aged 22-to-24 (46%).

Three-quarters of Starters described their ethnic group or background as ‘White’ (or a ‘White’ minority).[footnote 20] Just over one-in-five (22%) were of another ethnic group or background (excluding ‘White’ minorities), most commonly ‘Asian or Asian British’ (9% overall).

Younger Starters aged 18-to-21 were more likely to be ‘White’ (including ‘White’ minorities) than those aged 22-to-24 (78% compared to 72%), while those aged 22-to-24 were more likely to be from an ethnic minority background (excluding ‘White’ minorities) than 18-to-21 (25% compared to 19%).

Education

Young people taking part in Kickstart had a wide range of qualification levels. A fifth of Starters (20%) held only lower, ‘other’ or no qualifications. Almost a quarter of Starters (24%) held a Level 4 qualification or above, as shown in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1 Qualification level of Starters

E3. Which of these is the highest level of qualification you have? Base: All Starters (8,063)

Starters from ‘Asian or Asian British’ ethnic backgrounds and from ‘Black, African, Caribbean or Black British’ ethnic backgrounds were more likely to hold a qualification at Level 4 or above (37% and 38% respectively, compared to 21% of ‘White’ Starters (including ‘White minorities’)), and were less likely to have only lower or no qualifications (12% each, compared to 22%). This may partly reflect that Starters from ethnic minority backgrounds were more likely to be older. Both the age skew and the greater rates of higher-level qualifications may be due to greater participation in post-16 education among those from ethnic minority backgrounds overall.[footnote 21]

Health

Overall, 30% of Starters had a health condition or illness expected to last for at least 12 months, and 22% of all Starters (74% of those with a health condition or illness expected to last for at least 12 months) were limited in their ability to carry out day-to-day activities.

Female Starters were more likely to have a health condition or illness (36% compared to 25% of male Starters), and more likely to report this was limiting to some degree (77% of female Starters with a health condition compared to 70% of male Starters with a health condition).

‘White’ Starters (including ‘White minorities’), and those from ‘Mixed or multiple ethnic groups’ backgrounds were more likely to report a health condition or illness (34% and 30% respectively, compared to 15% of those from an ‘Asian or Asian British’ ethnic background and 16% of those from a ‘Black, African, Caribbean or Black British’ ethnic background). ‘White’ Starters (including ‘White minorities’) were more likely to report this was limiting (75% of ‘White’ Starters (including ‘White minorities’) with a health condition compared to 70% of Starters with a health condition from an ethnic minority background, excluding White minorities).

It was notable across interviews with Jobcentre staff, employers, and gateways that many flagged that anxiety, poor mental health, and low self-esteem were widespread among young people on Kickstart.

Living arrangements

Two-thirds of Starters (66%) lived with their parents. The qualitative research suggested that many of the young people who lived with their parents were receiving financial or other support from their parents. A small minority of Starters lived with their children (7%), so may have had parental responsibilities and constraints on their time, and indeed in the qualitative research, young people who were carers emphasised that they required a job that was flexible enough to fit around their caring responsibilities.

Starters with a health condition that impacted daily life substantially were notably less likely to live with their parents (58% compared to 70% of those without a health condition) and more likely to live alone (10% compared to 5% of those without).

Length of claim, prior employment and job search activity

Length of UC claim

Prior to starting their Kickstart job, a third of Starters (34%) had been registered for UC for over 18 months (‘long-term’), 28% for seven to 18 months (‘medium-term’), and 35% for six months or less (‘short-term’).[footnote 22]

Likelihood of being a long-term UC claimant decreased with qualification level Less than one-fifth of Starters with a qualification at Level 4 or above (17%) were long-term UC claimants versus over two-fifths of those whose highest qualification was at Level 2 or had lower or no qualifications (43%). Less than a quarter of Starters with lower or no qualifications (23%) were short-term claimants versus half of those with a qualification at Level 4 or above (51%).

Starters with a health condition that substantially impacted their daily life were more likely to have had long-term claims (39% versus 31% without a health condition), and less likely to be short-term claimants (33% versus 38% without a health condition).

Prior experience of paid work

Over seven-in-ten Starters (72%) had undertaken paid work before starting their Kickstart job. Two-fifths (42%) had done unpaid work (for example, shadowing, work placement, work experience, or volunteering), leaving only 13% reporting they had never worked.

However, less than a third of Starters (31%) had undertaken paid work for over a year and just over a quarter (28%) had no paid work experience at all.

Starters who were more likely to have had no work experience (paid or unpaid) prior to Kickstart included those who were:

- younger (16% aged 18-to-21 versus 8% aged 22-to-24)

- from an ‘Asian or Asian British’ ethnic background and from a ‘White (including White minorities)’ background (14% and 13% versus 9% of those from a ‘Black, African, Caribbean or Black British’ background)

- males (14% versus 11% of females)

The qualitative research provided further insight into the types of prior employment young people had held prior to Kickstart. Often, they had been employed on a casual basis on a zero-hours contract, and typically, young people described their financial situation as ‘unstable’ and ‘unpredictable’ as they were often not paid enough to cover their basic living expenses. Hence, even among those who had some work experience prior to Kickstart, this was often not felt to be meaningful or sustainable employment.

Changes in the profile of Starters as Kickstart continued

The section above shows the average profile of Starters throughout the duration of Kickstart. However, some characteristics became more prevalent in the Starter population as the scheme continued.

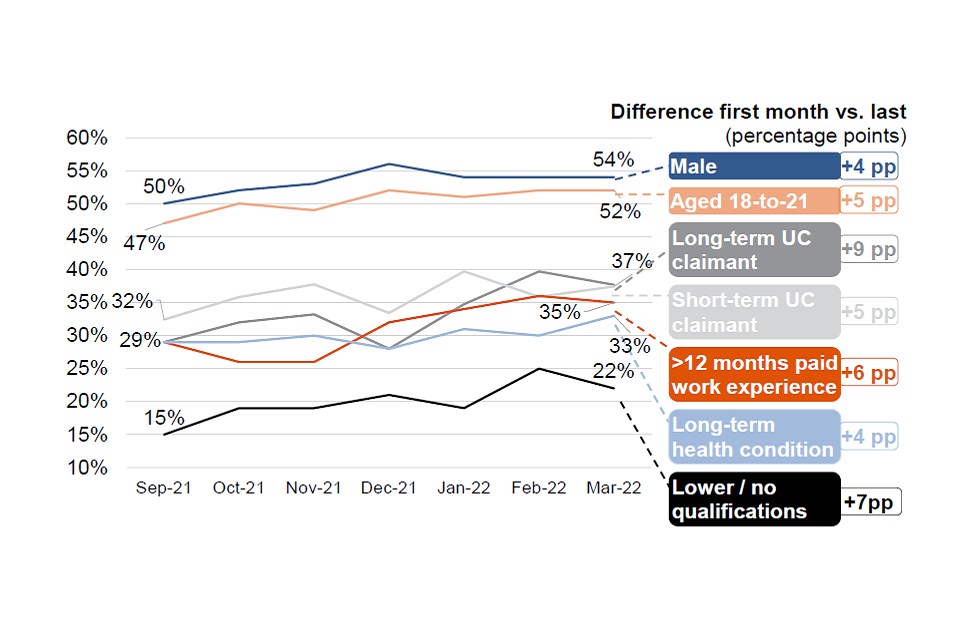

The greatest increases were in the proportions of Starters in groups typically considered harder to help or reach. There was an increase of nine percentage points in the proportion who were long-term UC claimants prior to their Kickstart job (from 29% of those who started their Kickstart jobs in September 2021 to 38% who started in March 2022), as shown in Figure 3.. There was an increase of seven percentage points in the proportion who had lower or no qualifications.

Kickstart was also reaching groups who would not typically be considered harder to help. Nevertheless, these groups could be considered at risk of long-term unemployment in the context of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. The proportions of Starters who had more than 12 months paid work experience; were aged 18-to-21; and who were short-term UC claimants also each grew by five or six percentage points as the scheme continued. Starters with medium-term prior UC claims accounted for a lower proportion of Starters as the scheme progressed (14 percentage point decrease, from 39% in September 2021 to 25% in March 2022).

Figure 3.2 Characteristics which accounted for a higher proportion of Starter population as Kickstart continued (by month started Kickstart job)

DWP records and survey responses Base: All Starters who started Kickstart jobs in September 2021 (1,144), in October 2021 (996), in November 2021 (1,382), in December 2021 (873), in January 2022 (810), in February 2022 (1,281), in March 2022 (1,577). Length of UC claim base: those for whom DWP hold records (7,784).

Introduction to Kickstart

Motivations for taking part

During the qualitative research, young people spoke about being motivated to take part in the Kickstart Scheme for various reasons.

Many young people described the difficulties they had experienced searching and applying for jobs outside of the Kickstart Scheme. When searching job sites, young people found it challenging to find a role that would both meet their interests and match their level of experience.

Some young people were looking for roles in a specific industry to apply specialist skills, while others described looking for anything with secure hours or within a certain travel distance.

Young people were attracted by the opportunity to gain transferable skills that they could bring to their future career and the offer of training was very appealing to them.

I knew through Kickstart I would be given training for different things and I really wanted to get experience in different aspects of hospitality so that when I move on from this job I have plenty training and I know what I’m doing.

(Young person, 21, Hospitality)

There were a few young people motivated to join the Kickstart Scheme out of boredom.

Truthfully I accepted the job because … I was sick of sitting at home and wasting my days away, I wanted to learn, I wanted to progress and I wanted to make people proud.

(Young person, 22, Car Mechanic)

Many young people were driven to take part in the Kickstart Scheme to improve their mental health and wellbeing (see Chapter 5 for findings from the qualitative research relating to confidence and resilience). Prior to getting their Kickstart job, young people reported feeling frustrated and confused following repeated job rejections, which led to low confidence levels. Young people reported that the pandemic had also increased their level of social anxiety and many young people felt that they lacked resilience.

Applying to Kickstart jobs

During the scheme a total of 2,969,000 referrals were made to Kickstart jobs, for 429,000 young people.[footnote 23] A referral is where a work coach had highlighted a Kickstart job vacancy to a claimant as an opportunity for them to consider. Multiple young people could be referred to, and apply for, each job vacancy.

Searching for appropriate roles

Young people mainly found appropriate Kickstart vacancies through suggestions from their work coach, although some also searched online themselves. More than four-fifths of Starters (84%) reported that they had also actively been looking for other paid jobs in the wider labour market during the period when they were searching for a Kickstart vacancy.

In the survey, most Starters reported that they heard about the Kickstart job that they started through their work coach (76%). For three-in-five (59%), this was during a meeting or call. The UC journal was the source of information about the vacancy for one-in-eight Starters (17%).

One-in-ten Starters (9%) heard about their Kickstart job via online job listings and 6% through recruitment sources such as job fairs. Four per cent heard about the vacancy directly from employers.

Partway through the scheme, Kickstart jobs were added to the GOV.UK Find A Job service. The impact of this can be seen in an increase in the proportion of Starters hearing about their job online. In the final wave of Starters (who started their jobs in March 2021), 15% had heard about their Kickstart job this way.

Kickstart jobs informed about through Universal Credit journal

Eighty-six per cent of Starters reported they were sent information about Kickstart jobs in their UC journal, 10% were unsure if this had happened and 4% reported they were not sent information in this way.

Three-fifths of Starters (62%) received information about between one and ten Kickstart jobs and 41% received information about up to five jobs. A quarter (25%) received information for more than 10 jobs and 11% received information for more than 20 jobs.

Experience of independently finding Kickstart jobs

During the qualitative depth interviews young people provided feedback on independently searching for Kickstart jobs. In addition to the time-intensive referral process of matching job seekers with vacancies (via their UC journal), there were also examples of Jobcentres sharing all available vacancies. In one case, the Jobcentre had a physical jobs wall that job seekers were encouraged to browse. In another case, the Jobcentre printed a list of all the new vacancies that week for the coaches to look through in coaching meetings. Later in the scheme, once Kickstart roles were added to the Find A Job website, independent searching became easier.