Country policy and information note: humanitarian situation, Iraq, May 2023 (accessible)

Updated 5 November 2025

Version 2.0

23 May 2023

Executive summary

Updated: 23 May 2023

After the military defeat of ISIS in Northern Iraq in 2017, the humanitarian situation in Iraq has improved but remains fragile; characterised by internal displacement and limited access to sufficient housing, basic services and livelihood prospects.

The overall number of people in need in Iraq decreased by 41% from 4.1 million people in 2021 to 2.5 million people in 2022. Those in need are generally Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) or those who have returned to their home areas of origin following the conflicts.

In general, the humanitarian situation in Iraq is not so severe that there are substantial grounds for believing that there is a real risk that conditions amount to torture or inhuman or degrading treatment as set out in paragraphs 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules/Article 3 ECHR.

In general, there are parts of the country where it will be reasonable for a person to relocate. Consideration must be given to a person’s particular circumstances, civil documentation held and the details of where they originally lived in Iraq when assessing if internal relocation is viable.

Decision makers still need to read the assessment in full and use relevant country information as the evidential basis for decisions.

Assessment

Updated: 23 May 2023

About the assessment

This section considers the evidence relevant to this note – that is information in the country information, refugee/human rights laws and policies, and applicable caselaw – and provides an assessment of whether, in general:

-

that the general humanitarian situation is so severe that there are substantial grounds for believing that there is a real risk of serious harm because conditions amount to inhuman or degrading treatment as within paragraphs 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules/Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)

-

a person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory

-

a claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and

-

if a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

Decision makers must, however, still consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts.

1. Material facts, credibility and other checks/referrals

1.1 Credibility

1.1.1 For information on assessing credibility, see the instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

1.1.2 Decision makers must also check if there has been a previous application for a UK visa or another form of leave. Asylum applications matched to visas should be investigated prior to the asylum interview (see the Asylum Instruction on Visa Matches, Asylum Claims from UK Visa Applicants).

1.1.3 In cases where there are doubts surrounding a person’s claimed place of origin, decision makers should also consider language analysis testing, where available (see the Asylum Instruction on Language Analysis).

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information in this section has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

1.2 Exclusion

1.2.1 Decision makers must consider whether there are serious reasons for considering whether one (or more) of the exclusion clauses is applicable. Each case must be considered on its individual facts and merits.

1.2.2 If the person is excluded from the Refugee Convention, they will also be excluded from a grant of humanitarian protection (which has a wider range of exclusions than refugee status).

1.2.3 For guidance on exclusion and restricted leave, see the Asylum Instruction on Exclusion under Articles 1F and 33(2) of the Refugee Convention, Humanitarian Protection and the instruction on Restricted Leave.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information in this section has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

2. Convention reason(s)

2.1.1 A severe humanitarian situation does not in itself give rise to a well-founded fear of persecution for a Refugee Convention reason.

2.1.2 In the absence of a link to one of the 5 Refugee Convention grounds necessary to be recognised as a refugee, the question to address is whether the person will face a real risk of serious harm in order to qualify for Humanitarian Protection (HP).

2.1.3 However, before considering whether a person requires protection because of the general humanitarian and/or security situation, decision makers must consider if the person faces persecution for a Refugee Convention reason. Where the person qualifies for protection under the Refugee Convention, decision makers do not need to consider if there are substantial grounds for believing the person faces a real risk of serious harm meriting a grant of HP.

2.1.4 For further guidance on the 5 Refugee Convention grounds see the Asylum Instruction, Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

3. Risk

3.1.1 Humanitarian conditions are, in general, not likely to be so severe as to result in a breach of paragraphs 339C and 339CA (iii) of the Immigration Rules/Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). However, decision makers must consider each case on its merits. There may be cases where a combination of circumstances means that a person will face such as breach.

3.1.2 In the country guidance case of SMO & KSP (Civil status documentation; Article 15) Iraq CG [2022] UKUT 110 (IAC), heard on 4 to 5 October 2021 and promulgated on 16 March 2022, the Upper Tribunal held:

The living conditions in Iraq as a whole, including the Formerly Contested Areas, are unlikely to give rise to a breach of Article 3 ECHR or (therefore) to necessitate subsidiary protection under Article 15(b) QD. Where it is asserted that return to a particular part of Iraq would give rise to such a breach, however, it is to be recalled that the minimum level of severity required is relative, according to the personal circumstances of the individual concerned. Any such circumstances require individualised assessment in the context of the conditions of the area in question.

(Paragraph 6 of part A of the headnote. The headnote for Civil Status Identity Documentation is at paragraphs 11 – 22 of part C).

3.1.3 At the time of writing there are not very strong grounds supported by cogent evidence to depart from the findings of SMO & KSP (Civil status documentation; Article 15) Iraq CG [2022] UKUT 110 (IAC).

3.1.4 In assessing whether an individual case reaches this threshold, decision makers must consider the person’s:

-

previous location/residence (as humanitarian conditions are more severe in some areas than others, and this may also impact on whether the person becomes an IDP on return, if they were not already prior to leaving the country)

-

individual profile and circumstances, including, but not limited to, their age, gender, state of health, ethnicity and means to support themselves

-

vulnerability to discrimination because of perceived or actual affiliation to extremist groups

-

ability to relocate to another area and access a support network.

3.1.5 For more information to assess individual cases see Humanitarian situation.

3.1.6 For guidance on Humanitarian Protection see the Asylum Instruction, Granting humanitarian protection. For further guidance on assessing risk, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

4. Protection

4.1.1 The state is not able to provide protection against a breach of Article 3 because of general humanitarian conditions should this occur in individual cases.

4.1.2 For further guidance on assessing risk, see the instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status and Granting humanitarian protection.

5. Internal relocation

5.1.1 Internal relocation may be possible for a person depending on their circumstances and what civil documentation they possess. See the CPIN Iraq: Internal relocation, civil documentation and returns for more information. When considering the possibility of non-Kurds relocating to the IKR, the findings of SMO & KSP (Civil status documentation; Article 15) Iraq CG [2022] UKUT 110 (IAC) state that “particular care must be taken in evaluating whether internal relocation to the IKR for a non-Kurd would be reasonable. Given the economic and humanitarian conditions in the IKR at present, an Arab with no viable support network in the IKR is likely to experience unduly harsh conditions upon relocation there.” (See para 35).

5.1.2 For further guidance on considering internal relocation and factors to be taken into account see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

6. Certification

6.1.1 Where a claim is refused, it is unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

6.1.2 For further guidance on certification, see Certification of Protection and Human Rights claims under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 (clearly unfounded claims).

Country information

About the country information

This contains publicly available or disclosable country of origin information (COI) which has been gathered, collated, and analysed in line with the research methodology. It provides the evidence base for the assessment.

The structure and content of this section follow a terms of reference which sets out the general and specific topics relevant to the scope of this note.

Decision makers must use relevant country information as the evidential basis for decisions.

Section updated: 24 March 2023

7. Geography and demography

7.1.1 Estimates of Iraq’s population vary according to different sources. According to the United Nations Population Fund, Iraq’s population in 2022 is 42,200,000 people[footnote 1]. According to the CIA World Factbook Iraq has an estimated population of 40,462,701 in 2022[footnote 2].

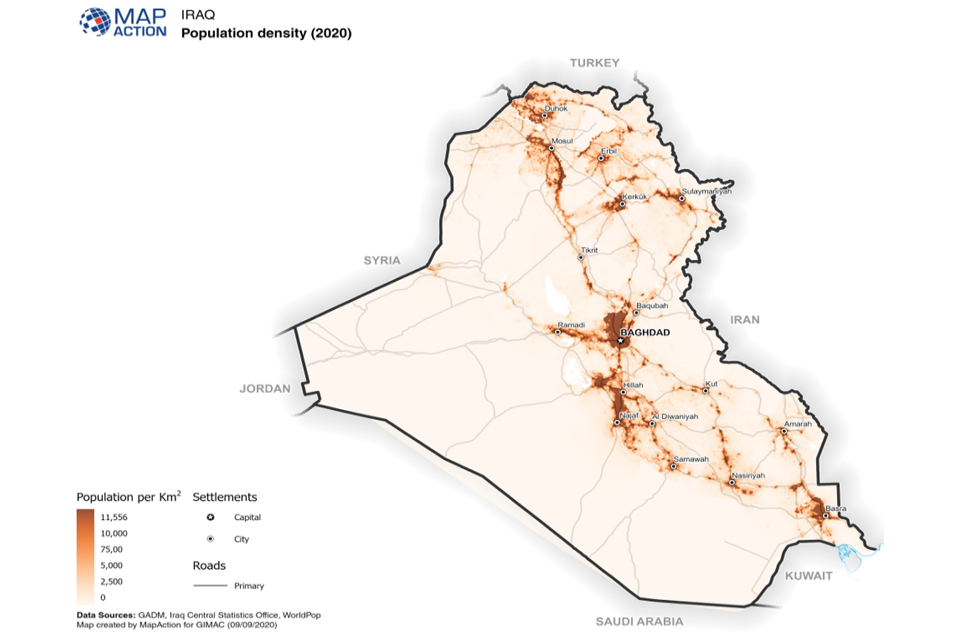

7.1.2 On 9 September 2020 MapAction published the below map[footnote 3] showing the population density of Iraq:

Map of Iraq showing the population density (per square kilometre) in 2020

Section updated: 23 May 2023

8. Economic situation

8.1 Overview of the economy of Iraq

8.1.1 On 27 March 2022 the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) published a report (the UNOCHA report) on the projected humanitarian situation in Iraq in 2022. The report entitled ‘2022 Humanitarian Needs Overview: Iraq’ stated:

In 2020, the Iraqi economy contracted by 15.7 per cent due to OPEC [Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries] oil cuts and COVID-19. Partially in response to this, the GoI [Government of Iraq] devalued the currency by 18.5 per cent in December 2020, which had a significant impact on citizens. However, oil prices recovered in 2021 (from US$45 per barrel to above $79 per barrel by November 2021), leading to predictions of a $10 billion budget surplus for the year. Accordingly, the World Bank predicts that Iraq’s GDP will grow by 2.6 per cent in 2021, 7.3 per cent in 2022 and 6.3 per cent in 2023.

… Despite increasing oil revenues and the reversal of initial economic shocks caused by COVID-19, future stability and prosperity of the country and her people is not assured. Any reduction in the price of oil; failure to implement necessary fiscal reforms; election-related instability; delays in widespread vaccination; and deterioration in security conditions amidst high regional geopolitical tensions would undermine the economic stability of the country.[footnote 4]

8.1.2 The United States Department of State (USSD) 2022 Investment Climate Statements of Iraq, published in April 2022, stated that:

The security environment, including the threat of resurgent extremist groups, remains an investment impediment in many parts of the country. Other lingering effects of the fight against ISIS include major disruptions of key domestic and international trade routes and the negative impacts on respective economic infrastructure. Many militia groups that participated in the fight against ISIS remain deployed and are only under nominal government control. Militia groups have been implicated in a range of criminal and illicit activities in commercial sectors, including extortion. However, the security situation varies throughout the country and is generally less problematic in the Iraqi Kurdistan Region (IKR).[footnote 5]

8.1.3 On 16 June 2022 the World Bank stated that:

Iraq’s economy is gradually emerging from the deep recession caused by the pandemic and the plunge in oil prices in 2020. After contracting by more than 11 percent in 2020, the economy grew by 2.8 percent in 2021 supported by the solid expansion of non-oil output, in particular services, as COVID-19 movement restrictions were eased. Oil GDP also started growing in the second half of 2021 as OPEC+ production cuts started to be phased out. Higher oil revenues pushed Iraq’s overall fiscal and external balances into a surplus in 2021, however, fiscal rigidities and high level of unaccounted arrears remain.

… [T]he turnaround in oil markets has improved Iraq’s economic outlook in the medium term. The economy is projected to grow in 2022-24 by 5.4 percent on average per year in 2022-24 as oil production increases in line with production capacity and higher investments finance by the oil windfall drives non-oil GDP growth. In the absence of structural reforms, the limited absorptive capacity of the economy remains a binding constraint on Iraq’s growth potential and macroeconomic stability.[footnote 6]

8.1.4 The media outlet Deutsche Welle (DW) stated in a report dated 28 October 2022 that Iraq’s new prime minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani ‘…said ‘“The epidemic of corruption that has affected all aspects of life is more deadly than the corona pandemic and has been the cause of many economic problems…”’[footnote 7]

8.2 Economy in the KRI

8.2.1 Author Nijdar S. Khalid noted in ‘Chapter 4, The State of the Institutions of Economic Freedom in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq’, of the public policy research organisation, Cato Institute’s Economic Freedom of the World report, published in September 2021, that:

The institutions of economic freedom in the KRI are young and fragile. They have been influenced by the economic, political, and security inheritance of previous Iraqi regimes, as well as traditional social and cultural norms. Since 1991, the KRI authorities have attempted to modify the structure and pattern of political and economic institutions in the KRI, through legislation and issuance of new laws and regulations to promote free markets and democracy, although institutions in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq continued to function according to the Iraqi institutional framework.

… between 2014 and 2017 the federal government cut off the KRI’s share of the federal budget as a result of the political conflict between the parties (World Bank Group, 2015: 19). The KRI’s share has not yet been fully restored and the KRI has not passed a public budget bill since 2014. During that period, the KRG declared economic independence and decided to sell its oil independently of Baghdad and rely on local revenues to finance public expenditures, but it failed to do either. The KRG relied on revenues from border crossings, local tax revenues, and oil revenues, but these financial resources did not cover the huge volume of government expenditures that were the result of the lack of transparency and the waste of public resources. So far, there is no accurate data for the total volume of public revenues in the KRI[footnote 8].

8.2.2 The same source added that:

In 2013, the KRG put in place comprehensive and ambitious reform program, The Kurdistan Region of Iraq 2020: A Vision for the Future, that covers public and private institutions in the economic, civil, and security sectors. The goals are to reduce bureaucracy and corruption, and to support start-up companies and entrepreneurship by lessening the regulatory burden. The plan also established free economic zones. These measures opened the economy and helped spur foreign investment, which flowed into the KRI faster than it did the rest of Iraq…

However, challenges still face the institutions of economic freedom in the KRI. Most of the laws, regulations, and reform programs are dead letters. Laws and regulations regarding property rights, doing business, investment, trade, and labor have not been fully implemented. They have been used to support the interests of the ruling parties and enrich political elites and tribal leaders. This led to the creation of an extensive patronage network [limiting access to jobs and business based on nepotism and tribal affiliation], crony capitalism, and rent-seeking…[footnote 9]

8.2.3 Nijdar S. Khalid further noted that:

Most commercial transactions are executed without free competition and transparency. The major investment and commercial projects, such as infrastructure projects, housing, oil and gas, telecommunications, and the pharmaceutical and cigarette trade, among other sectors, have been distributed in favor of certain individuals within specific tribes who are loyal to the ruling parties, in addition to controlling most government jobs. Consequently, an extensive predatory network of patronage, favoritism, and crony capitalism has been established that dominates main economic activities. Therefore, traditional tribal values and norms have distorted the ethics of business and freedom of investment and trade, diminished individuals’ confidence in the market system, and impeded the development of the institutions of economic freedom in the KRI.[footnote 10]

8.2.4 In March 2022, economic expert Mohammed Hussein stated in a political economy of public finance management paper published in the Iraqi Economists Network (IEN), a non-commercial network of politically independent Iraqi economists, that ‘One way to see how the KRG’s services are delivered is examining the government’s policy for outsourcing some services.

The government has more than 800 thousand employees on its payroll, but it hired an international accounting firm, Deloitte, to produce financial reports on its oil sector. Of this number on the payroll, more than 300 thousand are armed men (including members of Peshamrga [sic], police, and other types of security forces,) but the government has hired various private security companies to protect oil fields and facilities.

In the financial sector, similar to the rest of Iraq, the KRI’s public banks deliver no digital services to better meet consumers’ expectations and needs. The economy is still heavily cash-based, and most of the transactions are taking place through money transfer offices in the informal market.

…not surprisingly, the KRG has not done well in term of financial governance. No statistical data are available on the government’s public spending and revenues.’[footnote 11]

8.2.5 The same source added that also

The region’s economy has been strictly controlled by two patronage networks of Masud Barzani’ Kurdistan Democrats Party (KDP) and Bafel Talabani’s Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK). The two rival parties control economic activities in the private sector and manipulate public jobs to keep their domination. They monopolize construction and service contracts to politically linked companies that usually bypass competition in exchange for sharing some profits with the key figures in the ruling parties, which have governed the KRI since 1991.

Moreover, the patronage networks have a few cartels to conduct illicit and extortion activities that clearly undermine the KRG’s ability to collect revenues. Some leaders of the parties facilitate imports without paying tariff in the border ports of KRI (Skelton). The smuggling activities (conducted by the cartels belong to the same parties) still take huge part of the customsrevenues [sic]. According to one of the border ports’ directors, 80% of customs revenues go to some companies and not the KRG’s treasury (Wali).

Apart from the high level of corruption, KDP’s and PUK’s deep-state networks of power have divided KRI into two zones (yellow and green zones respectively) according to their parties’ military influences. They monopolize extortion activities and other gains from the revenue streams. This political economy that basically generated the fiscal challenges always hinders reform efforts.[footnote 12]

8.3 Employment

8.3.1 With regards to employment, the UNOCHA report stated:

Loss of income and livelihoods, prompted by COVID-19 in 2020, increased vulnerabilities and aggravated the humanitarian needs of IDPs and returnees. As of January 2021, the national unemployment rate was more than 10 percentage points higher than the pre-pandemic 12.7 per cent, and while some jobs have since been recovered, unemployment remains particularly high among IDPs and returnees, with women and people previously employed in the informal sectors mostly affected…As a result, unemployment and debt levels among conflict-affected households are higher in 2021 compared to 2020…[footnote 13]

8.3.2 The same report stated:

The precarious socioeconomic situation compels many to resort to negative coping strategies, exposing both adults and children to grave protection risks. The situation disproportionately affects women and people living with disabilities who often find it harder to find employment and be self-sufficient due to institutional and cultural barriers; and children who get married or engage in work to support their families. On average, among conflict-affected communities, 1 per cent of children are married and 6 per cent work to contribute to the family’s income; however, these issues are known to be underreported.[footnote 14]

8.3.3 The same report observed that:

While some camp residents find seasonal work or find employment within or near the camps, many adults are unemployed and seeking work. In the camps, 28 per cent of households have at least one adult member unemployed and seeking work, while 90 per cent of households report taking on debt to afford health care, food, education and basic household expenditures. IDPs in camps note increased competition, jobs being too far away and lack of qualifications as the main barriers to employment. In-camp IDP households with members living with disabilities and female-headed households are two and three times more likely, respectively to face unemployment compared to the rest of the households…[footnote 15]

8.3.4 With regards to employment opportunities for out-of-camp IDP households, the UNOCHA report stated:

Insufficient and inadequate food consumption is the result of limited or no income which is exacerbated by lack of livelihoods opportunities. Some 30 per cent of out-of-camp IDP households have at least one family member who is unemployed and seeking work. Many adults cannot find employment due to increased competition which is an issue for 73 per cent of out-of-camp IDPs households; perceived lack of opportunities for women (inclusive of both the failure of the market to open certain jobs for women and the perceived social and cultural barriers) noted by 17 per cent of the households; and lack of qualifications which is a barrier for 12 per cent of the households.[footnote 16]

8.3.5 With regards to employment opportunities for returnees, the UNOCHA report observed that:

Some 25 per cent of all households that have returned to their areas of origin have at least one family member above the age of 18 who is unemployed and seeking work, an increase from 18 per cent in 2020. Although returnees are more likely to rely on paid public sector jobs than IDPs, reliance on informal commerce or daily labour has reportedly also increased among returnees since 2020… Returnees cannot find employment primarily because of increased competition for jobs.[footnote 17]

8.3.6 Reporting from Sulaymaniyah on 30 November 2021, the BBC Arabic service noted that ‘… since the so-called Islamic State took control of areas adjacent to the region in 2014, the economic situation in Iraqi Kurdistan has been affected both in terms of the absence of investors and in terms of declining revenues from the center in Baghdad.’[footnote 18]

8.3.7 The non-partisan international affairs think tank, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (CEIP), noted on 8 September 2022, that ‘…Iraq’s unemployment rate sits in double-digits, and about a third of its youth population is neither in employment nor training.’[footnote 19]

8.3.8 Nalia Radio and Television (NRT), an independent media network in the Kurdistan region, reported on 19 September 2022 that ‘…Duhok has the highest unemployment among the Kurdistan Region’s provinces at 24.1 percent… the unemployment rate in Erbil province at 17.7 percent, and in Sulaimani and Halabja at 11.9 percent… [It] also showed Baghdad’s unemployment rate at 13.5 percent.’[footnote 20]

8.3.9 The same source added that ‘… Nineveh has the highest rate of unemployment rate in all of Iraq at 32.8 percent and Babil the lowest, which is 5.5 percent.’[footnote 21]

8.3.10 The Middle East Monitor (MEMO), an independent media research institution covering Middle Eastern issues noted in a report entitled ‘More than 6m unemployed in Iraq’ on 7 October 2022 that ‘The unemployment issue in Iraq is one of the most prominent files that have witnessed an escalation, especially in recent years, and most of the unemployed are university graduates who hold higher education degrees. Despite the promises made by successive governments to find solutions to this issue, including providing job opportunities and government appointments to reduce unemployment rates, it is to no avail.’[footnote 22]

8.3.11 The same source noted that ‘According to the Chairman of the GFTU [General Federation of Trade Unions], Sattar Danbous Barrak, “there are 6 million unemployed people in Iraq, and this issue does not have any government solutions”, noting in a statement to the official Iraqi news channel “the unemployment crisis in the country is worsening”.

‘He pointed out that “there are also 6 million workers in Iraq, including 650,000 registered in the Social Security Department, and that the minimum salary for a worker is only 350,000 dinars ($237.60)”, adding that “no amendment has been made to the Social Security Law in 51 years, while only 10 per cent of the private sector is activated and registered within the guarantee[d] department.”

‘Barrak also noted that “foreign labour enters Iraq without the knowledge of the Ministry of Labour and, according to the statistics we have, the number of foreign workers in Iraq is over one million.”’[footnote 23]

8.3.12 Amwaj, a media outlet covering news and analysis in Iraq, Iran, and the Arabian Peninsula, noted in its economy report published on 27 October 2022, that ‘Iraq has a major unemployment problem. For the past decade, official unemployment rates have seen a continuous rise, reaching 14.2% in 2021. The lack of jobs has sparked popular protests in the past, including contributing to mass anti-establishment demonstrations in Oct. 2019, and continues to spark social unrest.

Demographic pressures are likely to exacerbate the challenges faced by the authorities. The Ministry of Planning anticipates that the country’s population will rise to 51.2M in 2030 from the current 41.1M, creating a further squeeze on jobs. Competition for employment is heightened by the presence of foreign labor.

The true number of foreign workers in Iraq is unclear. Former Labor Minister Basim Abdul-Zaman stated in July 2019 that the figure stood at around 750,000. This is while last year the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs maintained that there were 400,000 illegal foreign workers in Iraq. However, the latest figures presented by the parliament’s Labor and Social Affairs Committee in March [2022] asserted that there are 1.5M foreign laborers in the country, including illegal workers.[footnote 24]

8.3.13 The same source added that:

Much of the concern among some Iraqis focuses on foreign workers without necessary permits. The Ministry of Interior has alleged that 95% of foreign workers in Iraq are employed illegally and said it deported 32,000 laborers in the second half of 2020. An increase in deportations is anticipated now that Covid-19-related travel restrictions have eased; Interior Ministry spokesman Khalid Al-Muhanna has said the authorities are “following strict procedures” by expelling illegal workers and restricting permit applications for foreign workers.

The issue has recently also come into political focus. In February [2022], then-deputy parliamentary speaker Hakem Al-Zameli warned that the phenomenon was leading to a “significant increase in unemployment rates” and taking a toll on the country’s “economy, social, and security situation.” Zameli called for increased coordination between the various authorities to determine the “need for foreign labor” and to “diagnose the entry points of illegal workers and tighten control over them.”[footnote 25]

8.3.14 Regarding categories of foreign labour and societal norms, Amwaj reported:

Economic researcher Rami Mohsen Jawad [had] told Amwaj.media that “skilled labor” is useful to Iraq as it “contributes to the productivity and the advance of projects as a whole” and ultimately to the overall economy. On the other hand, Jawad warned that a mass influx of “unskilled labor” could have “many negative consequences on the country’s economy”, most evidently in “increasing both unemployment and poverty rates.” He further highlighted that some employers are more inclined to hire unskilled foreign labor for reasons including lower wages and that they could be exploited by being pressured to work longer hours. This is especially true in the absence of strong laws to protect workers.[footnote 26]

8.3.15 The same source added

…for many Iraqis, “Hiring female labor to work inside homes, particularly in what is known as housekeeping, is not acceptable.” Therefore, workers are brought from abroad in great numbers to meet the high local demand. Agencies which facilitate their entry into Iraq receive 500 to 1,000 USD [£413.20 to £826.41 as on 10 February 2023[footnote 27]] per worker according to Jawad, in addition to commissions from the Iraqis who hire them.

Moreover, regional crises including economic strife and conflict have meant that “semi-skilled” workers are spreading wider in Iraq, mainly coming from Lebanon, Syria, and Turkey, according to Jawad. He noted that this category of workers competes with middle-income Iraqis who often work in the private sector, have degrees and some training. This includes professions such as teachers and journalists.[footnote 28]

Section updated: 23 May 2023

9. Humanitarian situation

9.1 Overview

9.1.1 The UNOCHA report stated: ‘Four years after the end of large-scale military operations against ISIL [Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant], the humanitarian context in Iraq remains fragile, characterized by protracted internal displacement; eroded national social cohesion; extensive explosive ordnance contamination; and incomplete rehabilitation of housing, basic services and livelihoods opportunities.[footnote 29]

9.1.2 In a news report on 7 December 2022, France24 said ‘Five years after it emerged from the Islamic State group’s jihadist rule, Iraq’s once thriving cultural centre of Mosul has regained a semblance of normalcy despite sluggish reconstruction efforts.

‘However, like in much of oil-rich but war-ravaged Iraq, ramshackle public services… continue to hamper people’s daily lives.’[footnote 30]

9.2 People in need (PIN) – numbers and location

9.2.1 The UNOCHA report stated:

Protracted displacement has come to characterize the post-conflict environment in Iraq; about 1.2 million people remain internally displaced, more than 90 per cent of whom fled their areas of origin more than four years ago; more than two thirds fled between January 2014 and March 2015. Returns have largely stagnated, with the number of displaced Iraqis only decreasing by 35,000 people from December 2020 to September 2021. Spontaneous returns remain slow in most areas and are often unsustainable due to unresolved challenges in areas of origin, including limited infrastructure, services and livelihoods; safety and security issues; and social tensions.’

Of the 6.1 million people originally displaced, 2.5 million [6.17% of the population] continue to face humanitarian needs, including 728,000 IDPs [Internally Displaced Persons] and 1.7 million returnees; of these just under 1 million people are in acute need, including 382,000 IDPs and 579,000 returnees.

The overall number of people in need (PIN) in Iraq decreased from 4.1 million people in the 2021 HNO to 2.5 million people in the 2022 HNO, a decrease of 41 per cent that partially reflects the stabilizing socioeconomic impact of COVID-19 and partially the result of a narrower focus on people with multiple humanitarian needs that require life-saving and life-sustaining assistance, rather than longer-term development and recovery assistance. [see paragraph 4.2.3 for more information].

The 2.5 million people in need include 180,000 in-camp IDPs, 549,000 IDPs displaced outside camps; and 1.7 million people who have returned to their areas of origin. Among them, there are 685,000 women, 543,000 girls, 676,000 men and 550,000 boys.[footnote 31]

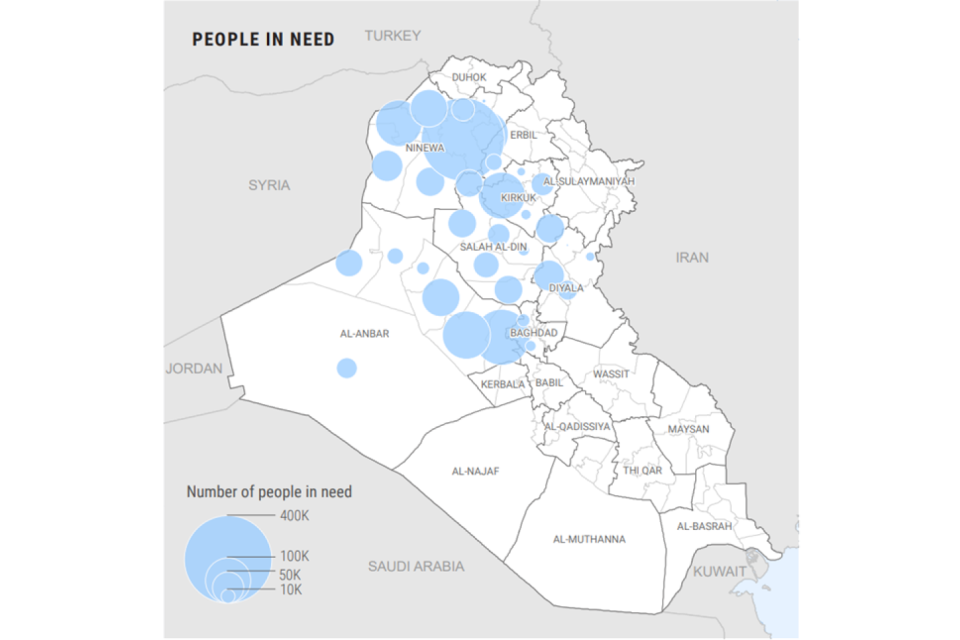

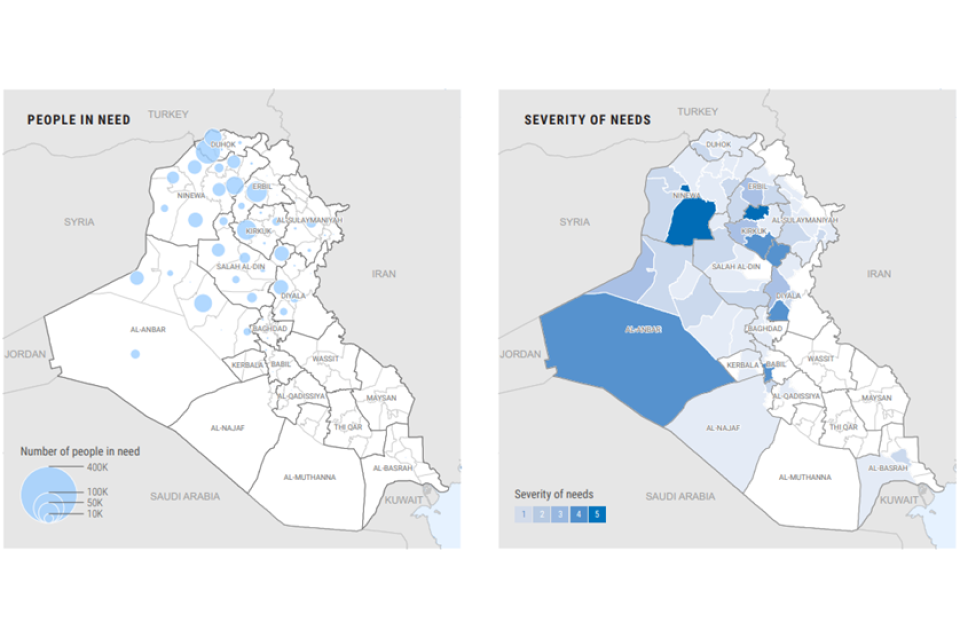

9.2.2 The same source also produced the following map[footnote 32] showing the number and location of the people in need across Iraq and also the breakdown of people in need by sex, age and disability[footnote 33]:

Map showing the number and location of the people in need across Iraq and the breakdown of people in need by sex, age and disability

People in need by sex, age and disability

| Population group | Population | PIN | Female | Male | Children | Older people | With disability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-camp IDPs | 180,000 | 180,000 | 93,000 | 87,000 | 84,000 | 7,000 | 27,000 |

| Out-of-camp IDPs | 1.01 million | 549,000 | 275,000 | 273,000 | 250,000 | 19,000 | 27,000 |

| Returnees | 4.88 million | 1.73 million | 843,000 | 883,000 | 714,000 | 80,000 | 259,000 |

| Overall | 6.1 million | 2.5 million | 1.2 million | 1.2 million | 1.1 million | 96,000 | 368,000 |

9.2.3 Estimates of the size of the population of Iraq vary according to different sources. Please note that figures on PIN therefore may also vary (see also Geography and Demography).

9.2.4 On 27 March 2022 UNOCHA published its humanitarian response plan for Iraq in 2022. The report stated the following regarding a refinement to the criteria used for assessing humanitarian needs which decision makers should take into account when reading the following sections:

…, the humanitarian community in Iraq refined the criteria for assessing humanitarian needs. The revised criteria aimed to better identify people with the highest levels of vulnerability, particularly those with a multitude of needs, focusing on those needs that are a direct result of the impact of the ISIL crisis.

As a result of this revised approach to humanitarian needs analysis the 2022 Humanitarian Needs Overview (HNO) for Iraq identified 2.5 million people in need (PIN), of whom 961,000 people have acute humanitarian needs, reaching extreme or catastrophic levels……[t]he number of people in need decreased by 41 per cent compared to last year, while the number of people in acute need, reaching extreme or catastrophic levels, decreased by 61 per cent. This reduction is largely attributable to the narrower definition of humanitarian needs, and does not reflect significant improvement in the lives of internally displaced persons (IDPs) and returnees in Iraq.[footnote 34]

9.3 Shelter and non-food items (NFI)

9.3.1 The UNOHCA report stated’[a]pproximately 1 million people need emergency shelter and non-food items (NFI) support, a 60 per cent reduction since 2021. Among them, over 533,000 people are in acute need. The decrease in needs is primarily due to a narrower definition of humanitarian shelter needs, focusing on people living in critical shelter, including tents, unfinished and abandoned structures, makeshift shelter, and non-residential, public and religious buildings; and in sub-standard shelter that poses risks to residents’ health, safety and dignity. A far greater number of conflict-affected people, particularly returnees, have shelter needs that require longer-term solutions falling outside the scope of the humanitarian response.’[footnote 35] Regarding the affected population the same source stated:

In-camp IDPs: All 180,000 in-camp IDPs live in critical shelter and depend on humanitarian support for regular tent replacement and replenishment of worn-out NFIs, including fuel for cooking and heating. Of these about 134,000 are particularly vulnerable as they are in urgent need of tent replacement and NFI replenishment.

… Up to 197,000 out-of-camp IDPs have emergency shelter and NFI needs. This includes 143,000 out-of-camp IDPs who live in critical shelter, including in tents, unfinished and abandoned structures, makeshift shelter, and non-residential, public and religious buildings. Of these, 122,000 people are estimated to be in acute need due to living in unfinished and abandoned buildings or makeshift shelter…

… Overall, 661,000 returnees have humanitarian needs related to shelter and NFIs. This includes the 7 per cent of the overall returnee population who live in critical shelter (331,000 individuals) and 260,000 who live in shelter conditions that pose direct threats to their health, safety and dignity. Of them, 42 per cent are in acute need, with almost all (83 per cent) concentrated in 10 districts.[footnote 36]

9.3.2 The same source additionally stated:

-

Government-led camp closures in the final three months of 2020 led to a reduction in the number of people living in camps

-

Of the 657,000 people who live in critical shelter, most are in Sumail District in Duhok Governorate, Sinjar District in Ninewa Governorate and Al-Falluja District in Al-Anbar Governorate.

-

Additionally, 620,000 people – some of whom also live in critical shelter – are in need of humanitarian shelter assistance due to living in shelters exposed to hazards… or lacking safety and security… Most are concentrated in Al-Mosul District in Ninewa, and Al-Ramadi and Al-Falluja districts in Al-Anbar.

-

Among out-of-camp IDPs, families missing documentation are five times more likely to be at risk of eviction.

-

The most cited shelter improvement needs across all population groups are the insufficient insulation from cold and hot weather… including rain leakage, the need for improved privacy… and improved safety, and protection from hazards… Overcrowding in informal sites and other out-of-camp settings due to insufficient housing options greatly impacts out-of-camp IDPs. Access to affordable essential household items, a prerequisite for a minimum standard of living, continues to be a challenge, with about 15 per cent of the affected population reporting that they do not have at least one essential item, including mattresses, bedding items and cooking utensils, despite regular large NFI distributions by humanitarian actors.[footnote 37]

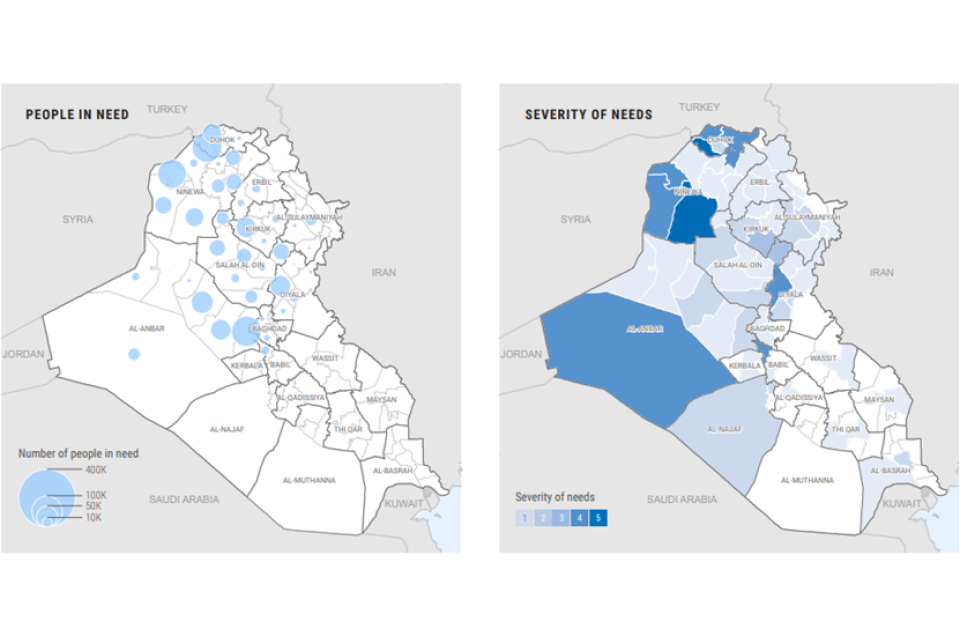

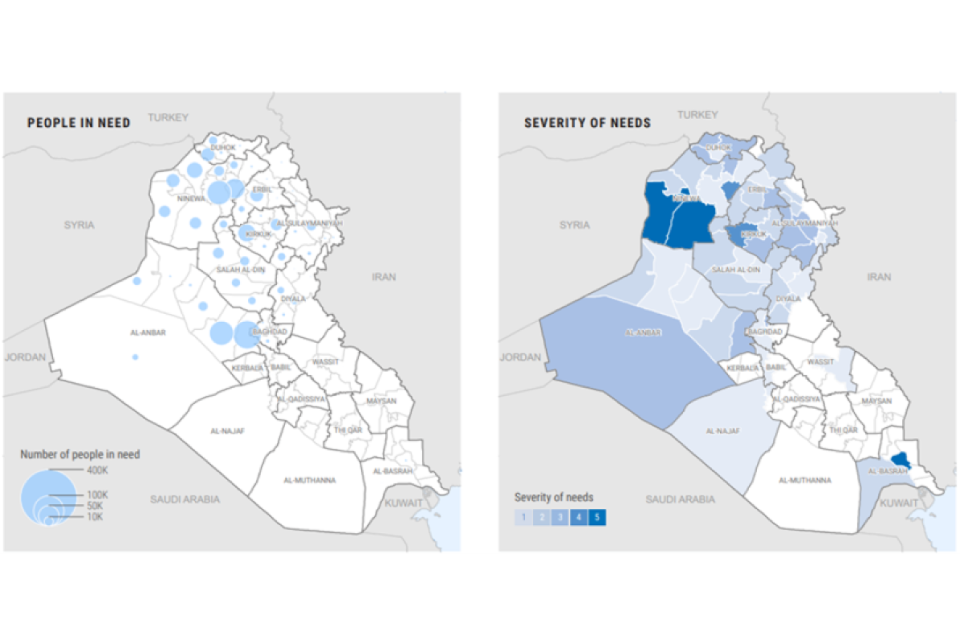

9.3.3 The same source additionally produced the following maps[footnote 38] showing the numbers of people in need of shelter and non-food item assistance and the severity of that need in each governorate:

Maps showing the numbers of people in need of shelter and non-food item assistance and the severity of that need in each governorate

9.4 Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH)

9.4.1 The UNOHCA report stated ‘[a]pproximately 1.6 million IDPs and returnees in 62 districts need emergency WASH support, a 38 per cent reduction since 2021. Among them, 694,000 IDPs and returnees are in acute need of assistance, a decrease of 54 per cent from 2021. The decrease in needs is primarily due to the adoption of a narrower definition of humanitarian WASH needs.’[footnote 39]

9.4.2 Regarding the affected population the same source stated:

… As of November 2021, about 180,000 IDPs reside in camps that require comprehensive and continuous WASH services to ensure sufficient quantity and quality of water, operation of WASH facilities, and solid waste management. The greatest need is for access to an adequate quantity of water; just 67 per cent of in-camp IDPs report that they have access to enough water…

… Approximately 37 per cent of IDPs living in out-of-camp settings have humanitarian WASH needs, with 154,000 of those experiencing acute needs. There has been a 13 per cent increase in needs among out-of-camp IDPs from 2021, with IDPs living in informal settlements and unable to return to their areas of origin, being a major driver of this increase. The greatest need is for improved water quality, which is required by 234,188 out-of-camp IDPs, followed by increased water quantity, required by 177,000…

… More than 1.1 million returnees have emergency WASH needs, with 397,000 of those in acute need. Among them, the greatest need is for improved water quality, which is required by 89 per cent of the returnees in need…[footnote 40]

9.4.3 The same source additionally stated:

-

In 2021, there has been a reduction in humanitarian WASH needs for conflict-affected populations in Al-Anbar, Baghdad, Duhok, Kirkuk, Ninewa and Salah Al-Din.

-

However, in Al-Basrah, Al-Sulaymaniyah, Diyala and Erbil, an increase in WASH needs is observed. These governorates are facing water shortages due to a decrease in rainfall in the Tigris and Euphrates river catchment in the 2020-2021 rainy season, coupled with insufficient release of water upstream.

-

The highest severity of needs is in hard-to-reach districts hosting out-of-camp IDPs and returnees. The top districts in terms of severity are Sinjar, Al-Baaj and Al-Hatra, all in Ninewa Governorate, which have access issues and high numbers of returnees in areas recovering from ISIL occupation.

-

High severity of needs is also evident in locations recently impacted by water scarcity issues. Al-Basrah, while only hosting 2,304 IDPs, has over 50 per cent of those IDPs in severe need of WASH support.

-

Districts with large caseloads of in-camp IDPs also have severe needs, particularly seen in Zakho and Sumail districts in Duhok Governorate.[footnote 41]

9.4.4 The same source also produced the following maps[footnote 42] showing the numbers of people in need of WASH assistance and the severity of that need in each governorate:

Maps showing the numbers of people in need of WASH assistance and the severity of that need in each governorate

9.5 Poverty

9.5.1 The NGO World Vision noted on 18 February 2022 that:

Prior to the pandemic, one in five children in Iraq lived in poverty. Since the onset of COVID-19, with a rise in unemployment in an already fragile economy, that figure has risen to up to 40%. There are also signs that violence against children is increasing, and access to basic services, such as routine health care, is limited. The economic impacts of the pandemic, along with the extended school closures, have led to an increase in negative coping strategies, including school drop-out, child marriage and child labour.[footnote 43]

9.5.2 Al-Jazeera reported on 17 October 2022 that ‘Poverty has reached about 25 percent of the population, while the number of poor people in the country is estimated at 11 million out of the 42 million population of Iraq.

According to official data, nearly 3 million Iraqis receive monthly financial grants from the government. They are out of 9 million who deserve assistance, and the government cannot provide it to all of them due to poor allocations and the failure to approve the general budget.

… the poverty rate in Iraq ranges between 22-25%. Muthanna governorate (southwest) leads the poorest governorates with 52%, followed by Diwaniyah and Dhi Qar governorates in the south with 49%.

… the poverty rate in the provinces “liberated from ISIS” reached 41%, as in the province of Ninawa (north). In the middle, the poverty rate ranges between 15-17%, while the capital Baghdad has exceeded 12%, which applies to the cities of the Kurdistan region…

Meanwhile, humanitarian activist Saeed Yassin Moussa believes that poverty in Iraq has turned into a social scourge, especially since about a quarter of the country’s population is suffering from poverty due to the absence of development policies and the loss of social justice that has led to high unemployment…

The community activist [Moussa] links the high rate of poverty in Iraqi society to the expansion of the scourge of corruption, organized crime and drugs, “as vulnerable and poor groups are exploited in promoting them,” calling for the need to impose the law and adopt development policies within large and realistic programs that provide a decent life for Iraqis.[footnote 44]

9.5.3 The media outlet Deutsche Welle (DW) stated in a report dated 28 October 2022 that Iraq’s new prime minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani ‘…said ‘“…corruption…has been the cause of… weakening the state’s authority, increasing poverty, unemployment, and poor public services…”’[footnote 45]

9.6 Climate change

9.6.1 In a Country Brief published in May 2022, the World Food Programme summarized that ‘In Iraq, intermittent conflict and impact of climate change continue to affect the lives of people of Iraq. In the post-conflict context, there are approximately 1.2 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) and 4.1 million people in need of humanitarian assistance. Insecurity, lack of livelihoods, and destroyed or damaged housing hamper people’s ability to return home.’[footnote 46]

9.7 Food security

9.7.1 The UNOCHA report stated that ‘[a]pproximately 730,000 IDPs and returnees in 101 districts face challenges meeting their daily food needs… The number of people in need has remained similar to 2021, while the number of people in acute need has decreased by 48 per cent.’[footnote 47] Regarding the affected population the same source stated:

In-camp IDPs: All IDPs living in formal camps continue to rely on food assistance to meet all of their daily food needs. While nearly all (96 per cent) in-camp IDPs report little to no hunger, most continue to rely on external assistance to avoid deterioration of their food security status…

Out-of-camp IDPs: An estimated 130,000 IDPs living out of camps are food insecure. Governorates with the most food insecure out-of-camp IDPs are Erbil (50,000), Ninewa (18,000), Duhok (15,000) and Al-Sulaymaniyah (11,000)… Compared to IDPs living in camps, they more frequently face moderate or severe hunger, and rely on crisis- and emergency-level coping strategies, such as child labour or child marriage to generate income to meet their basic food needs. The number of food insecure out-of-camp IDPs has slightly increased compared to 2021, linked to secondary displacement due to camp closures and challenges for out-of-camp IDPs in accessing livelihoods opportunities…

Returnees: An estimated 420,000 returnees are food insecure and lack access to livelihoods. Returnees living in critical shelter are up to five times more likely to experience food insecurity than those in more sustainable dwellings. Governorates with the highest number of food insecure returnees are Ninewa (158,000), Al-Anbar (124,000), Salah Al-Din (59,000) and Kirkuk (28,000).[footnote 48]

9.7.2 The same source additionally stated:

-

Food insecurity among IDPs and returnees in Iraq continues to be primarily linked to their displacement status, resulting in high levels of aid dependency, particularly in camps, as well as challenges establishing sustainable livelihoods and accessing predictable income sources.

-

This is particularly true for people missing civil documentation required for employment or to access the government’s social safety nets, and for people living in displacement or returns areas with limited job opportunities.

-

Of the 730,000 IDPs and returnees with humanitarian food security needs, 626,000 have borderline or poor food consumption, 425,790 of whom are returnees, 179,629 out-of-camp IDPs and 21,000 in-camp IDPs. Of the mentioned total, 213,000 individuals face poor food consumption and severe hunger.

-

The highest levels of food insecurity are found in Al-Falluja District (189,000 people), followed by Al-Hawiga (49,000), Heet (50,000), Erbil (49,000) and Al-Hatra (31,000) districts.

-

Among out-of-camp IDPs, those missing core civil documentation are three times more likely to experience food insecurity, while among returnees, female-headed households are nearly three times more likely to face moderate or severe hunger. For both population groups, households with a family member living with disabilities are 2-3 times more likely to experience food insecurity. [footnote 49]

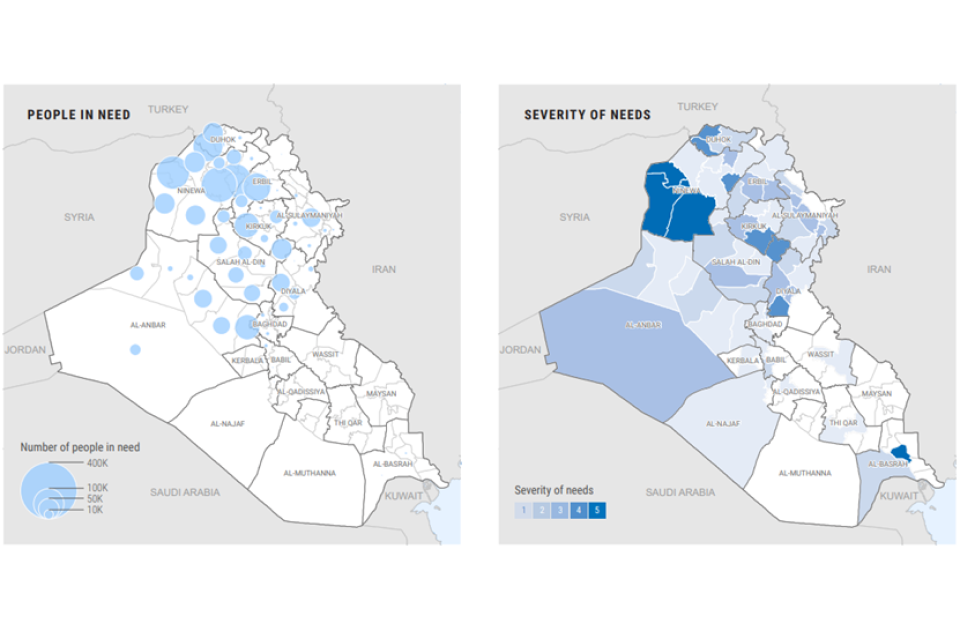

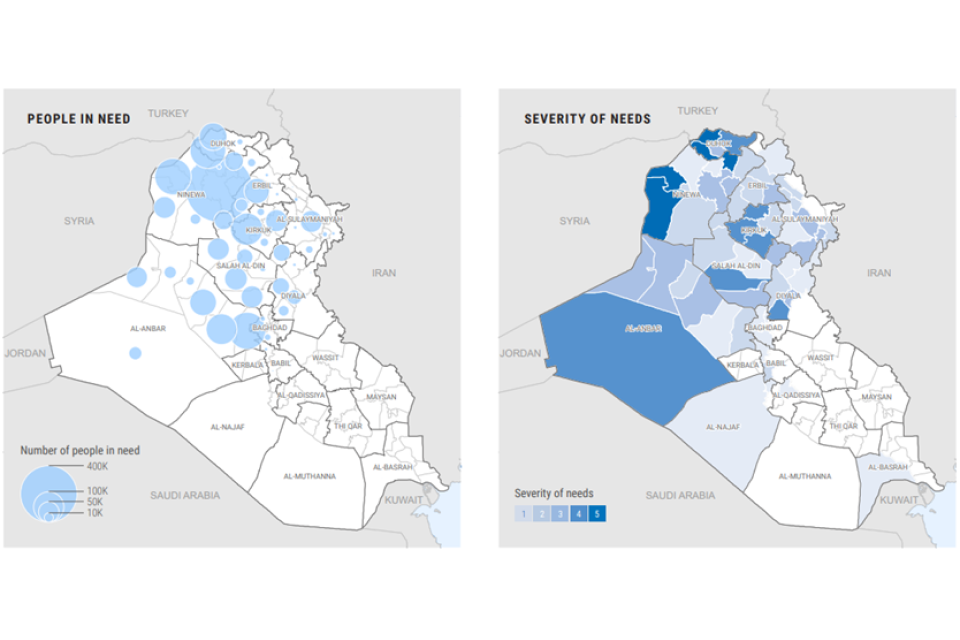

9.7.3 The same source additionally produced the following maps[footnote 50] showing the numbers of people in need of food assistance and the severity of that need in each governorate:

Maps showing the numbers of people in need of food assistance and the severity of that need in each governorate

9.7.4 On 16 June 2022, the World Bank stated that: “Iraq’s existing food security challenges have intensified with the recent surge in global commodity prices, while domestic food production fell short of demand from the country’s rapidly growing population.”[footnote 51]

9.7.5 In a report of the UN Secretary General on the implementation of resolution 2576 (2021), it was observed that:

The conflict in Ukraine had a severe impact on global supply chains during the reporting period, negatively affecting food prices and wheat imports and threatening food security in Iraq. In that regard, WFP noted a 16 per cent increase in the average price of vegetable oil in Iraq during the first two weeks of March, while the average price of wheat flour increased by 9 per cent at the national level during the same period. The year-on-year increase in the price of wheat flour was 26 per cent.[footnote 52]

9.8 Children

9.8.1 In a report of the UN Secretary-General on Children and Armed Conflict in Iraq, it is stated that ‘During the reporting period [1 August 2019 to 30 June 2021], the country task force verified 317 grave violations against 254 children…Denial of humanitarian access was the second most verified violation, with 62 verified incidents.’[footnote 53]

9.8.2 The International Rescue Committee (IRC), an NGO working to help people affected by crisis and conflict[footnote 54] published a press release on 20 November 2022 regarding a survey undertaken on 211 households in neighborhoods in East Mosul and additional surveys with 265 children who had been identified as engaged in child labor[footnote 55]. It was found that:

… 90% of caregivers reported having one or more children engaged in labor. While 85% of children reported that they did not feel safe in their place of work, describing instances of harassment and not having proper equipment to protect themselves during work in factories or on the streets.

…Child labor rates were highest in returnee households, with more than 50% reporting one or more children engaged in work activities. For those who remain displaced, more than 25% of households reported one or more child participating in labor, and for host community households the percentage reporting child labor was over 20%.

Around 75% of the children surveyed reported working in informal and dangerous roles such as trash collection, daily construction labor, and collecting scrap metals.

Caregivers reported that nearly half the children in their households were not attending school, with many stating child labor as a leading cause of dropouts.[footnote 56]

9.8.3 A 2021 report by the US Department of Labour noted that:

In 2021, Iraq made minimal advancement in efforts to eliminate the worst forms of child labor. The Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs launched a campaign with the International Labor Organization to raise awareness about child labor among students, families, and employers in sectors in which child labor is present. However, despite new initiatives to address child labor, Iraq is assessed as having made only minimal advancement because it continued to implement a practice that delays advancement to eliminate child labor.[footnote 57]

9.9 Education

9.9.1 UNOCHA noted in a report dated 20 November 2022 that ‘…Iraq is a signatory to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and enshrines mandatory primary education for all children in its constitution. Despite the protections for Iraqi children in law, the reality is far different for many children across the country.’[footnote 58]

9.9.2 The UNOCHA report stated that approximately 681,000 IDP and returnee children need education support which is a decrease of 57% from 2021[footnote 59]. The report clarifies that: ‘The decrease in education needs is largely due to the adoption of a narrower definition of humanitarian education needs, focused on access to distance learning, school enrolment rates, barriers to accessing education opportunities, and lack of civil documentation.’[footnote 60]

9.9.3 Regarding the affected population the same source stated:

In-camp IDPs: Overall, 80 per cent of school-aged children (49,000 school-aged children) displaced in camps have emergency education needs, and 50 per cent are in acute need. Overall, their greatest need is for civil documentation, with nearly 24 per cent of in-camp IDP households having at least one child reportedly missing a key individual document, hindering access to education services. Camp populations are among the most vulnerable, and often lack the resources and facilities to access distance education.

Out-of-camp IDPs: An estimated 121,000 schoolaged children displaced outside formal camps need education assistance. Out-of-camp IDP children face significant barriers to accessing both in-person and remote learning opportunities. Their greatest need is for support with education costs, with one third of out-of-camp IDPs reporting that the cost of schooling is the main barrier hindering attendance Psychosocial support is also a critical need with 11 per cent of out-of-camp IDP households reporting that their children have experienced psychosocial distress.

Returnees: Nearly 511,000 school-aged returnee children face challenges in accessing education. An estimated 12 per cent of school-aged returnee households reported that children had dropped out of school in the previous year. Increased dropout rates are likely attributable to child labour, early marriage or barriers to accessing remote learning modalities.[footnote 61]

9.9.4 The same source additionally stated:

-

IDP and returnee children’s physical, cognitive and mental well-being continues to be impacted by the years of armed conflict and protracted displacement, and by the COVID-19 pandemic. School offers a protective environment against negative coping mechanisms. Protection threats related to child recruitment into armed groups and explosive hazards are higher for boys, while girls are at increased risk of targeted kidnappings, rape, sexual violence and forced marriage, with serious mental and physical health consequences.

-

Female-headed households are generally more likely to engage in negative coping strategies, with child marriage being slightly more prevalent in female-headed households. Children in female-headed households are also significantly more likely to engage in family or non-structured work than children in male-headed households. Furthermore, school-aged girls living with disabilities are three times more likely to experience gender-based violence (GBV).

-

In 2021, an estimated 223,000 vulnerable displaced and returnee girls and boys dropped out of school, an increase of 8 per cent compared to the 2018-2019 school year, which was the last full school year without COVID-19-related school closures.

-

Of the 681,000 children with emergency education needs, more than 485,000 vulnerable boys and girls have not enrolled in school and are missing civil documentation, have psychosocial distress or are exposed to explosive hazards. National identity cards are necessary to access essential services, including school registration for formal education in places of displacement or returns areas.

-

People without documentation are more likely to experience other negative conditions such as increased risk of eviction, reliance on negative coping strategies, having at least one child unable to access distance learning, increased exposure to child protection risks, and little or no access to improved sanitation.

-

In 2021, approximately 650,000 vulnerable displaced and returnee girls and boys did not access distance learning or in-person education, facing severe barriers. Among these, 21 per cent (138,000) experience severe barriers that put their health and safety at risk.

-

Access to online and blended education resources remains a serious challenge for displaced and returnee children due to the lack of reliable internet connectivity, unreliable electricity supply, inability to afford proper equipment for remote engagement, and related unfamiliarity with such programmes.[footnote 62]

9.9.5 The same source additionally produced the following maps[footnote 63] showing the numbers of people in need of educational support and the severity of that need in each governorate:

Maps showing the numbers of people in need of educational support and the severity of that need in each governorate

9.10 Healthcare (and COVID-19)

9.10.1 Reuters reported on 2 March 2020 that ‘Around 20,000 doctors, a third of Iraq’s 52,000 registered physicians, have fled since the 1990s, the association said. One doctor interviewed by Reuters said that of the 300 doctors in his 2005 graduation class, half have left Iraq.’[footnote 64]

9.10.2 A non-profit organisation, the Borgen Project, noted on 28 July 2020 that ‘Around half of the primary care facilities in the country are currently not staffed by doctors. The majority of these buildings have no access to running water, worn-out machines and shortages of medicine along with other basic medical supplies. The doctors present are often overspecialized and in need of more thorough training.’[footnote 65]

9.10.3 The Washington Institute’s Fikra Forum, a platform which provides current information in both English and Arabic of events in the Middle East noted in an article published on 15 July 2021 that

Corruption has played a major role in this ongoing collapse of infrastructure. Iraq is one of the most corrupt countries in the world according to Transparency International, and this naturally extends to the health system as well…

In fact, the Iraqi government actually impedes providing better health care for Iraqis in both the public and private sectors. There is fierce competition between Iraqi politicians to win the Health Ministry because this ministry allows its holder to embezzle money from medicine contracts. There is also evidence presented in U.S. courts against companies that bribed the Health Ministry to win contracts. In fact, the Iraqi government and the Health Ministry are accused of selling medicine intended to the ministry on the black market. As such, when COVID-19 spread in the Middle East, the Iraqi government and society were caught underprepared.[footnote 66]

9.10.4 Uppsala Reports, a news magazine of the World Health Organisation (WHO) Collaborating Centre which provides information on the regulations of controlled medicines, noted on 17 August 2021 that a 2019 Iraqi Ministry of Health (MOH) report had stated that in Iraq’s medical private sector ‘…around 60-70% of medicines in the private sector do not enter the country through official processes (they are neither registered nor quality tested) – a problem that arose in Iraq after 2003, when the importation of medicines to the private sector became decentralised.’[footnote 67]

9.10.5 The UNOCHA report stated ‘[a]pproximately 1.7 million IDPs and returnees in 59 districts need essential primary health-care services, a decrease of 30 per cent from 2021. Among them, about 231,000 IDPs and returnees are in acute need, a decrease of 64 per cent from 2021.’[footnote 68] Regarding the affected population the same source stated:

… Nearly 142,000 IDPs residing in camps require comprehensive primary health-care services to minimize morbidity and mortality from communicable and non-communicable diseases, as well as alleviate mental health and physical rehabilitation needs. Cost was cited by nearly 90 per cent of in-camp IDP households as a barrier to accessing health care. Furthermore, more than 50 per cent of in-camp IDP households reported spending more than 25 per cent of their total household expenditure on health care…

… More than 300,000 out-of-camps IDPs have challenges meeting their basic health care needs due to barriers accessing primary health-care services, including unavailability of health services and lack of documentation, the latter mainly in accessing hospital services. Out-of-camp IDPs are often not eligible for free health care due to lack of accepted documentation of displacement status, which is required to access free, public services provided by the government…

… Approximately 1.2 million returnees are estimated to need essential health-care services, including 64,000 returnees who are in acute need…[footnote 69]

9.10.6 The same source additionally stated:

-

Iraq’s public health system has been severely impacted by years of conflict, emigration of healthcare practitioners, and limited physical infrastructure.

-

Humanitarian health needs are most severe in Al-Rutba, Al-Amadiya, Sumail, Zakho, Baquba, Al-Hawiga, Daquq, Dibis, Al-Baaj, Al-Shikhan, Sinjar and Samarra districts.

-

Individuals living in critical shelter are 7.8 times more likely to have low access to primary health-care services within one hour of travel.

-

An estimated 44 per cent of returnee households and 47 per cent of out-of-camp IDP households reported having an unmet health need in the past three months due to the prohibitive cost of health-care services.

-

Although access to health care for IDPs and returnees has improved since 2015, there are still risks for the most vulnerable populations caused by increased water scarcity and future waves of COVID-19, which could exacerbate health needs in the year ahead.[footnote 70]

9.10.7 The same source additionally produced the following maps[footnote 71] showing the numbers of people in need of health assistance and the severity of that need in each governorate:

Maps showing the numbers of people in need of health assistance and the severity of that need in each governorate

9.10.8 According to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Covid-19 dashboard, as of 17 May 2023 there have been 2,465,545 confirmed cases of Covid-19 and 25,375 deaths. As of 2 January 2023, a total of 19,557,364 vaccine doses have been administered[footnote 72].

9.10.9 The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) National News reported on 2 December 2022 that ‘Iraq’s corrupt healthcare system lies at the centre of the country’s failure to overcome conflict, an expert has said.

Citizens of the fifth oil-richest nation in the world struggle to access basic medicine and treatment for conditions and injuries under a network blighted by inadequacy and upheaval.

Medicine destined for public use too often ends up being sold for private profit in under-the-table deals in which the Iraqi upper-class benefits at the expense of the poor. What is left for the public health system is often unusable because it has expired or is not genuine.[footnote 73]

9.10.10 In a report by the UN Assistance Mission for Iraq (UNAMI), it was stated that:

Persons with disabilities in Iraq, who have been disproportionately affected by armed conflict, violence and other emergencies, experience multiple challenges in accessing equitable services, thereby hindering full enjoyment of their rights and meaningful participation in society. Their situation has been worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has compounded obstacles they face in accessing protection and humanitarian

assistance.[footnote 74]

9.11 Humanitarian response plan (HRP)

9.11.1 On 13 April 2022 UNOCHA published a humanitarian update which looked at events between January and March 2022. The bulletin provided a summary of UNOCHA’s humanitarian response plan (HRP) for 2022:

Based on the tighter humanitarian needs analysis and the agreed targeting criteria, the 2022 Iraq HRP will prioritize life-saving and life-sustaining humanitarian assistance for 991,000 Iraqi IDPs and returnees, including 180,000 IDPs in formal camps, 234,000 IDPs living in out-of-camp areas, and 577,000 returnees. The total cost of the response, as outlined in the HRP, amounts to US$400 million. The 2022 HRP focuses on providing safe and dignified living conditions, protecting IDPs and returnees from physical and mental harm related to the impact of the ISIL crisis.

Humanitarian actors seek to improve unsafe living environments for people living in camps, informal sites or other critical shelter—or in areas with EO contamination—while also providing specialized protection services to the people most at risk of rights violations, violence, abuse and other serious protection risks. Humanitarian partners will provide support to vulnerable IDPs and returnees to access essential services that they are otherwise unable to access, either because they face specific barriers or because they live in areas where services and infrastructure have not yet been rehabilitated. The most acutely vulnerable IDPs and returnees will be supported with emergency food assistance, emergency livelihoods support and temporary cash to meet their most basic needs and avoid reliance on harmful negative coping mechanisms for their survival.

The 991,000 acutely vulnerable people who will be the focused target of this HRP, are located across 14 of the 18 governorates of Iraq. The six governorates with the highest target populations are Ninewa (356,000 people), Al-Anbar (166,000), Duhok (155,000), Salah Al-Din (92,000), Kirkuk (66,000) and Diyala (55,000). The largest numbers of in-camp IDPs targeted through the HRP are in Duhok (110,000), Ninewa (45,000), Erbil (14,000) and Al-Sulaymaniyah (11,000), while the governorates hosting the most out-of-camp IDPs are Ninewa (60,000), Duhok (46,000), Erbil (34,000) and Al-Anbar (24,000). For returnees, the largest number is also in Ninewa (249,000), followed by Al-Anbar (141,000), Salah Al-Din (73, 000), Kirkuk (54,000) and Diyala (45,000).[footnote 75]

9.12 Humanitarian aid access

9.12.1 The USSD annual report covering the human rights situation in 2021 noted:

Government forces, including the ISF and PMF, established or maintained roadblocks that reportedly impeded the flow of humanitarian assistance to communities in need, particularly in disputed territories such as the Ninewa Plain and Sinjar in Ninewa Province…

Security considerations, unexplode ordnance, destruction of infrastructure, COVID-19 curfews, and travel restrictions, as well as official and unofficial access restrictions, limited humanitarian access to communities in need…

Out of the estimated 2.4 million persons in need of humanitarian assistance in the country, in September alone more than 18,000 were affected by restrictions imposed on humanitarian movements, according to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). OCHA reported that while there were occasionally location- and context-specific restrictions on humanitarian NGO operations, these were usually temporary and eventually resolved. There were few to no areas where humanitarian NGOs were categorically prevented from working. There were, however, areas of high sensitivity where militias or local security actors were less comfortable with NGOs’ presence, which generally diminished the scale and pace of humanitarian operations in those areas.[footnote 76]

For information on internal travel and freedom of movement generally, see CPIN Internal relocation, civil documentation and returns.

Research methodology

The country of origin information (COI) in this note has been carefully selected in accordance with the general principles of COI research as set out in the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), April 2008, and the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation’s (ACCORD), Researching Country Origin Information – Training Manual, 2013. Namely, taking into account the COI’s relevance, reliability, accuracy, balance, currency, transparency and traceability.

All the COI included in the note was published or made publicly available on or before the ‘cut-off’ date(s). Any event taking place or report/article published after these date(s) is not included.

Sources and the information they provide are carefully considered before inclusion. Factors relevant to the assessment of the reliability of sources and information include:

-

the motivation, purpose, knowledge and experience of the source

-

how the information was obtained, including specific methodologies used

-

the currency and detail of information

-

whether the COI is consistent with and/or corroborated by other sources

Wherever possible, multiple sourcing is used and the COI compared and contrasted to ensure that it is accurate and balanced, and i provides a comprehensive and up-to-date picture of the issues relevant to this note at the time of publication.

The inclusion of a source is not, however, an endorsement of it or any view(s) expressed.

Each piece of information is referenced in a footnote.

Full details of all sources cited and consulted in compiling the note are listed alphabetically in the bibliography.

Terms of reference

A ‘Terms of Reference’ (ToR) is a broad outline of what the CPIN seeks to cover. They form the basis for the country information section. The Home Office’s Country Policy and Information Team uses some standardised ToR, depending on the subject, and these are then adapted depending on the country concerned.

For this particular CPIN, the following topics were identified prior to drafting as relevant and on which research was undertaken:

- Humanitarian conditions

- socio-economic indicators, including statistics on life expectancy, literacy, school enrolment, poverty rates, levels of malnutrition

- socio-economic situation, including access and availability to:

- food

- water for drinking and washing

- accommodation and shelter

- employment

- healthcare – physical and mental

- education

- support providers, including government and international and domestic non-government organisations

- variation of conditions by location and/or group

- internally displaced persons (IDPs) – numbers, trends and location

Bibliography

Sources cited

Al-Jazeera,

-

‘Corruption is draining Iraq. How big is it and what is the role of the government in fighting it?’, 8 October 2022. Last accessed:13 February 2023

-

‘A quarter of Iraqis are poor. This is how wars, corruption and political stalemate have weighed on one of the oil-rich countries’, 17 October 2022. Last accessed: 13 February 2023

Amwaj, ‘Iraq’s unemployment crisis puts spotlight on foreign workers’, 27 October 2022. Last accessed: 10 February 2023

BBC News, ‘Migration from Iraqi Kurdistan: Do Migrant Caravans Continue from the Region?’, 30 November 2021. Last accessed: 10 February 2023

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (CEIP), ‘Economic Costs of Iraq’s Intra-Shia Power Struggle’, 8 September 2022. Last accessed: 10 February 2023

Cato Institute, ‘The State of the Institutions of Economic Freedom in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq’, September 2021. Last accessed: 23 March 2023

CIA World Factbook, ‘Iraq – People and Society’, updated 1 July 2022. Last accessed: 26 July 2022

Deutsche Welle (DW), ‘Iraq gets a new government after a year of deadlock’, 28 October 2022. Last accessed: 14 February 2023

Fikra Forum, ‘Iraq’s Health System: Another Sign of a Dilapidated State’, 15 July 2021. Last accessed: 15 February 2023

France 24, ‘Iraq’s Mosul healing slowly, five years after IS defeat’, 7 December 2022. Last accessed: 14 February 2023

International Rescue Committee,

-

‘About us’, nd. Last accessed: 18 May 2023

-

‘High child labor rates in Iraq continue to disrupt children’s education, childhood and basic rights, the IRC warns’, 20 November 2022. Last accessed: 18 May 2023

Iraqi Economists Network (IEN), ‘Public Finance Management as a Driver of Instability in KRG’, 3 March 2022. Last accessed: 23 March 2023

MapAction, ‘Iraq – Population density (2020)’, 9 September 2020. Last accessed: 26 July 2022

Middle East Monitor (MEMO), ‘More than 6m unemployed in Iraq’, 7 October 2022. Last accessed: 10 February 2023

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA),

-

‘Humanitarian Needs Overview 2022: Iraq’, 27 March 2022. Last accessed: 20 June 2022

-

‘Humanitarian Response Plan 2022: Iraq’, 27 March 2022. Last accessed: 23 June 2022

-

‘Iraq: Humanitarian Bulletin, January – March 2022’, 13 April 2022. Last accessed: 23 June 2022

-

‘High child labor rates in Iraq continue to disrupt children’s education, childhood and basic rights, the IRC warns’, 20 November 2022. Last accessed: 14 February 2023

Nalia Radio and Television (NRT), ‘Dohuk leading unemployment rate in Kurdistan Region- Report’, 19 September 2022. Last accessed: 13 February 2023

The Borgen Project, ‘6 Facts About Healthcare in Iraq’, 28 July 2020. Last accessed: 14 February 2023

The National News, Middle East and North Africa (MENA), ‘Iraq’s fragmented healthcare system ‘at the heart of the struggle to overcome war’, 2 December 2022. Last accessed: 14 February 2023

Reuters, ‘The medical crisis that’s aggravating Iraq’s unrest’, 2 March 2020. Last accessed: 14 February 2023

Uppsala Reports, ‘Substandard falsified medications in Iraq’s private sector’, 17 August 2021. Last accessed: 15 February 2023

United Nations Population Fund, ‘World Population Dashboard Iraq’, no date. Last accessed: 26 July 2022

U.S. Department of Labor, ‘2021 Child Labor and Forced Labor Reports, Iraq’, 28 September 2022. Last accessed: 14 February 2023

Unites States State Department (USSD), ‘2022 Investment Climate Statements: Iraq’, April 2022. Last accessed: 23 March 2023

World Bank, ‘Iraq Economic Monitor, Spring 2022: Harnessing the Oil Windfall for Sustainable Growth’, 16 June 2022. Last accessed: 26 July 2022

Health Organization, ‘Iraq: WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard with Vaccination Data’, 18 May 2023. Last accessed: 18 May 2023

World Vision, ‘Child Protection and COVID-19: Iraq Case Study’, 18 February 2022. Last accessed: 14 February 2023

Xe, ‘Currency Converter’, Last updated on 10 February 2023. Last accessed: 10 February 2023

Sources consulted but not cited

Reuters, ‘Covid-19 Tracker – Iraq’, 23 June 2022. Last accessed: 23 June 2022

United Nations Development Programme, ‘Human Development Report 2020’, 15 December 2020. Last accessed: 13 June 2022

World Bank, ‘Literacy rate, adult total (% of people ages 15 and above) Iraq’, 2017. Last accessed: 13 June 2022

Version control and feedback

Clearance

Below is information on when this note was cleared:

-

version 2.0

-

valid from 23 May 2023

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information in this section has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

Changes from last version of this note

Updated COI following the Independent Advisory Group on Country Information (IAGCI)-commissioned review of February 2023 and executive summary added.

Feedback to the Home Office

Our goal is to provide accurate, reliable and up-to-date COI and clear guidance. We welcome feedback on how to improve our products. If you would like to comment on this note, please email the Country Policy and Information Team.

Independent Advisory Group on Country Information

The Independent Advisory Group on Country Information (IAGCI) was set up in March 2009 by the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration to support him in reviewing the efficiency, effectiveness and consistency of approach of COI produced by the Home Office.

The IAGCI welcomes feedback on the Home Office’s COI material. It is not the function of the IAGCI to endorse any Home Office material, procedures or policy. The IAGCI may be contacted at:

Independent Advisory Group on Country Information

Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration

1st Floor

Clive House

70 Petty France

London

SW1H 9EX

Email: chiefinspector@icibi.gov.uk

Information about the IAGCI’s work and a list of the documents which have been reviewed by the IAGCI can be found on the Independent Chief Inspector’s pages of the gov.uk website.

-

United Nations Population Fund, ‘World Population Dashboard Iraq’, no date ↩

-

CIA World Factbook, ‘Iraq – People and Society’, last updated 1 July 2022 ↩

-

MapAction, ‘Iraq – Population density (2020)’, 9 September 2020 ↩

-