Country policy and information note: Kurds and Kurdish political groups, Iran, October 2025 (accessible)

Updated 7 January 2026

Executive summary

Estimates of the number of Kurds in Iran vary from 7 to 15 million (c.8–17% of the total population). They reside mostly in northwestern Iran, along the borders with Turkey and Iraq.

While the Constitution provides for equal rights for ‘all people of Iran whatever the ethnic group or tribe to which they belong’, this is not observed in practice. Kurds face discrimination by the state which affects their access to basic services.

Kurds who are members or sympathisers of Kurdish political parties, or who are involved in Kurdish civil and cultural activities may be surveilled, arrested and detained, and charged with broadly defined security offences, often leading to lengthy prison sentences, and in some cases the death penalty.

Kurds fearing persecution from the Iranian authorities on account of their ethnicity and/or their engagement in activities that are, or are perceived to be, political and against the state of Iran are likely to fall within the Refugee Convention on the grounds of race and/or actual or imputed political opinion.

Kurds are unlikely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm from the state based on ethnicity alone. However, Kurdish ethnicity is a risk factor which, when combined with others, increases the risk of persecution/Article 3 ill-treatment.

Kurds found to be engaged in activities that are, or are perceived to be, political and against the state of Iran, which may include promoting Kurdish rights, are likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm.

Whether a person of Kurdish ethnicity is likely to be at risk on return to Iran will depend on a nuanced consideration of factors outlined in the relevant Country Guidance cases:

- BA (demonstrations), including the nature of the sur place activity, the risk that the person has been, or will be, identified, and whether the profile or history of the person is likely to trigger further inquiry or action on return to Iran

- XX (online), including a person’s position on a “social graph”, whether they are likely to have been the subject of targeted online surveillance, and whether a person has, or is likely to, close their social media account(s) prior to any potential “pinch points”, when basic searches on the person are likely to be carried out.

Where the person has a well-founded fear of persecution or serious harm from the state, they will not, in general, be able to obtain protection nor be able to internally relocate to escape that risk.

Where a claim is refused, it is unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

All cases must be considered on their individual facts, with the onus on the person to demonstrate they face persecution or serious harm.

Asessment

Section updated: 1 October 2025

About the assessment

This section considers the evidence relevant to this note – that is the country information, refugee/human rights laws and policies, and applicable caselaw – and provides an assessment of whether, in general:

- a person faces a real risk of persecution/serious harm by the state because of the person’s Kurdish ethnicity and/or their actual or perceived affiliation with a Kurdish political group

- internal relocation is possible to avoid persecution/serious harm

- a claim, if refused, is likely or not to be certified as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

Decision makers must, however, consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts.

1. Material facts, credibility and other checks/referrals

1.1 Credibility

1.1.1 For information on assessing credibility, see the instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

1.1.2 Decision makers must also check if there has been a previous application for a UK visa or another form of leave. Asylum applications matched to visas should be investigated prior to the asylum interview (see the Asylum Instruction on Visa Matches, Asylum Claims from UK Visa Applicants).

1.1.3 Decision makers must also consider making an international biometric data-sharing check, when one has not already been undertaken (see Biometric data-sharing process (Migration 5 biometric data-sharing process)).

1.1.4 In cases where there are doubts surrounding a person’s claimed place of origin, decision makers should also consider language analysis testing, where available (see the Asylum Instruction on Language Analysis).

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information on this page has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

1.2 Exclusion

1.2.1 Most Kurdish political parties have at some point launched armed campaigns against Iran. Decision makers must consider whether there are serious reasons to apply one (or more) of the exclusion clauses. Each case must be considered on its individual facts.

1.2.2 If the person is excluded from the Refugee Convention, they will also be excluded from a grant of humanitarian protection (which has a wider range of exclusions than refugee status).

1.2.3 For guidance on exclusion and restricted leave, see the Asylum Instruction on Exclusion under Articles 1F and 33(2) of the Refugee Convention, Humanitarian Protection and the instruction on Restricted Leave.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information on this page has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

2. Convention reason(s)

2.1.1 Race and/or actual or imputed political opinion.

2.1.2 Establishing a convention reason is not sufficient to be recognised as a refugee. The question is whether the person has a well-founded fear of persecution on account of an actual or imputed Refugee Convention reason.

2.1.3 For further guidance on the 5 Refugee Convention grounds, see the Asylum Instruction, Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

3. Risk

3.1 Kurdish ethnicity

3.1.1 Kurds are unlikely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm from the state based on their Kurdish ethnicity alone. However, Kurdish ethnicity is a risk factor which, when combined with other factors, may create a risk of persecution or Article 3 ill-treatment (HB, see paragraphs 3.1.4 to 3.1.5).

3.1.2 Estimates of the number of Kurds in Iran vary from 7 to 15 million (c.8–17% of the total population). Approximately half a million Iranian Kurds reside in the capital, Tehran, but they mostly live in northwestern Iran, along the borders with Turkey and Iraq, in an area which the Kurds refer to as Rojhelat (Eastern Kurdistan) (see Demography and Maps).

3.1.3 The Constitution provides for equal rights for ‘all people of Iran whatever the ethnic group or tribe to which they belong’, however this is not observed in practice. Kurds in Iran face discrimination by the state which affects their access to basic services such as housing, political office, employment and education. Kurdish regions in Iran have some of the highest unemployment rates in Iran and face economic neglect, underdevelopment, and poverty. Use of the Kurdish language is restricted, with some Kurdish literature, and Kurdish instruction in public schools, prohibited despite the Constitution allowing for regional and tribal languages to be used for teaching their literature in schools. While Kurdish can be taught in private settings, recent arrests of Kurdish language teachers affects the ability of Kurds to exercise their linguistic and cultural rights. In early 2025, the Iranian parliament rejected a proposal to allow non-Persian languages to be taught in schools (see Discrimination, Education and Employment, and Language).

3.1.4 In the country guidance case of HB (Kurds) Iran CG [2018] UKUT 430 (IAC) (heard 20 to 22 February and 25 May 2018 and promulgated 12 December 2018), the Upper Tribunal (UT) found: ‘Kurds in Iran face discrimination. However, the evidence does not support a contention that such discrimination is, in general, at such a level as to amount to persecution or Article 3 ill-treatment.’ (paragraph 98 (2)).

3.1.5 In HB, the UT also found:

‘Since 2016 the Iranian authorities have become increasingly suspicious of, and sensitive to, Kurdish political activity. Those of Kurdish ethnicity are thus regarded with even greater suspicion than hitherto and are reasonably likely to be subjected to heightened scrutiny on return to Iran.

‘However, the mere fact of being a returnee of Kurdish ethnicity with or without a valid passport, and even if combined with illegal exit, does not create a risk of persecution or Article 3 ill-treatment.

‘Kurdish ethnicity is nevertheless a risk factor which, when combined with other factors, may create a real risk of persecution or Article 3 ill-treatment. Being a risk factor it means that Kurdish ethnicity is a factor of particular significance when assessing risk.’ (paragraph 98 (3) to (5)).

3.1.6 The country information in this note does not indicate that there are ‘very strong grounds supported by cogent evidence’ to depart from these findings.

3.1.7 See also Returnees and the Country Policy and Information Note, Iran: Illegal exit.

3.1.8 For further guidance on assessing risk, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

3.2 Actual or perceived Kurdish political activities

3.2.1 Kurds found to be engaged in activities in Iran that are, or are perceived to be, political and against the state of Iran, which may include promoting Kurdish rights, are likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm.

3.2.2 Each case must be considered on its facts with the onus on the person to show that the activity engaged in is likely to be viewed by the Iranian authorities as Kurdish political activity or support for Kurdish rights.

3.2.3 The headquarters of a number of Kurdish opposition parties are based in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI). They are illegal in Iran, so their presence and level of activity in the country is limited. While Kurdish political parties are often described as separatists and have previously engaged in armed activities against Iran, most no longer pursue a separate Kurdish state and increasingly favour peaceful political activities over continued military action. Members generally meet in secret to discuss politics. Members and supporters (also referred to as sympathisers), are encouraged, often via Kurdish TV and social media, to take part in peaceful propaganda activities such as protests, general strikes, or more symbolic actions such as wearing traditional Kurdish clothing. Party members and supporters are often organised in small, secret, ‘cells’ and tend not to disclose their political affiliation to others (see Iranian Kurdish political groups, Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (PDKI) / Kurdistan Democratic Party of Iran (KDPI / KDP-I), Kurdistan Freedom Party (PAK), Komala, and Kurdistan Free Life Party / Free Life Party of Kurdistan (PJAK)).

3.2.4 Intelligence agencies and security forces operating in Kurdish regions monitor people who partake in activities deemed to oppose the Iranian government. Kurds who are members or sympathisers of Kurdish political parties, or who are engaged in, or associated with, civil and cultural activities asserting their ethnic and religious identity, may be surveilled, arrested and detained. Some are charged with broadly defined security offences which may lead to social restrictions, floggings, lengthy prison sentences, and in some cases the death penalty. One human rights organisation reported that of 630 Kurds it verified as having been arrested/abducted by Iranian security forces in 2024, 153 of them (24%) were sentenced to imprisonment, flogging, or social restrictions for being political, religious, and civil activists. A further 11 Kurds (under 2% of arrested Kurds) were reportedly sentenced to death in 2024 (see State treatment).

3.2.5 Kurds are arrested, convicted, and sentenced in relation to their civic and political activities in disproportionate numbers. According to one human rights organisation, during 2024 and the first half of 2025, between 45% and 51% of all those it verified as having been arrested were Kurds. It also recorded, during the same time period, that approximately 30% of political, religious, and civil activists who were sentenced to prison terms, flogging, and social restrictions, were Kurds. The same human rights organisation reported that approximately 77% (10 of 13) of political or religious activists executed in 2024 were Kurds. An annual death penalty report noted that in 2023, of 39 people executed under the security-related charges, 8 of them (20.5%) were Kurds. A database of verified political prisoners and prisoners of conscience recorded that between 1980 and 2025, at least 29% were Kurds, with that figure likely higher due to the ethnicities of some prisoners being uncertain or unknown. The Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) also use excessive force against those participating in political demonstrations in Kurdish areas (see State treatment).

3.2.6 According to Danish Immigration Service sources, the likelihood of a Kurd being arrested in connection with their political activities increases with their level of participation, irrespective of their status as either a member or sympathiser of a political party. Prison sentences for Kurds charged depends on the personal views of the Judge towards Kurds, whether any party affiliation can be proven, whether actions of a military nature are involved, whether a confession exists, and whether the charges are intended only to deter the person, or to make an example of them. Harsher penalties are reportedly handed down to Kurds who admit party affiliation during questioning (see Political activists and protestors and Arrests, convictions and imprisonment).

3.2.7 Confessions extracted through torture are reported by various sources. Approximately 50% (76 of 154) of all political affiliation-related executions between 2010 and 2023 were carried out against Kurds. Additionally, most of the demonstrators who were killed by the Iranian authorities’ excessive use of force during the ‘Women, Life, Freedom’ protests, that began in September 2022, were also Kurds (see Detention and torture, Executions and extra-judicial killings and Political activists and protestors).

3.2.8 Iranian state forces operate in the KRI, monitoring the activities of Iranian Kurdish political parties, their members and supporters, journalists, and human rights defenders. Iran has also carried out bombings, targeting Kurdish groups in the KRI, despite an Iran-Iraq security agreement. Iran has additionally requested that Iraq extradites party members and leaders for trial in Iran (see Monitoring in the Kurdish Region of Iraq (KRI)).

3.2.9 Family members of people engaged in social or political activities, or affiliated to Kurdish political parties, particularly if that affiliate is abroad, may experience exclusion from employment and education, reporting obligations, travel bans, surveillance (of phones, computers, and movements), threats, interrogation, arrest, detention, torture and in some cases criminal charges. The closer the relationship with the activist, the more likely a family member is to be detained, with the severity of the treatment dependent on the level of activity of the person of interest (see Targeting of activists’ family members).

3.2.10 In HB the UT found factors, which when combined with Kurdish ethnicity, may create a real risk of persecution or Article 3 ill-treatment (paragraph 98 (5)). These factors include:

‘A period of residence in the KRI by a Kurdish returnee is reasonably likely to result in additional questioning by the authorities on return. However, this is a factor that will be highly fact-specific and the degree of interest that such residence will excite will depend, non-exhaustively, on matters such as the length of residence in the KRI, what the person concerned was doing there and why they left.

‘Kurds involved in Kurdish political groups or activity are at risk of arrest, prolonged detention and physical abuse by the Iranian authorities. Even Kurds expressing peaceful dissent or who speak out about Kurdish rights also face a real risk of persecution or Article 3 ill-treatment.

‘Activities that can be perceived to be political by the Iranian authorities include social welfare and charitable activities on behalf of Kurds. Indeed, involvement with any organised activity on behalf of or in support of Kurds can be perceived as political and thus involve a risk of adverse attention by the Iranian authorities with the consequent risk of persecution or Article 3 ill-treatment.

‘Even “low-level” political activity, or activity that is perceived to be political, such as, by way of example only, mere possession of leaflets espousing or supporting Kurdish rights, if discovered, involves the same risk of persecution or Article 3 ill-treatment. Each case, however, depends on its own facts and an assessment will need to be made as to the nature of the material possessed and how it would be likely to be viewed by the Iranian authorities in the context of the foregoing guidance.

‘The Iranian authorities demonstrate what could be described as a “hair-trigger” approach to those suspected of or perceived to be involved in Kurdish political activities or support for Kurdish rights. By “hair-trigger” it means that the threshold for suspicion is low and the reaction of the authorities is reasonably likely to be extreme.’ (paragraph 98 (6) to (10)).

3.2.11 The country information in this note does not indicate that there are ‘very strong grounds supported by cogent evidence’ to depart from these findings.

3.2.12 For further guidance on assessing risk, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

3.3 Sur place activities

3.3.1 Whether a person of Kurdish ethnicity is likely to be at risk on return to Iran will depend on a nuanced consideration of factors outlined in the relevant Country Guidance cases:

- BA (demonstrations), including the nature of the sur place activity, the risk that the person has been, or will be, identified, and whether the profile or history of the person is likely to trigger further inquiry or action on return to Iran (see paragraph 3.3.6). Decision makers should keep in mind that where a Kurd returning to Iran is likely to be identified (see paragraphs 3.3.5 and 3.3.8) as having participated sur place in demonstrations, even ‘low-level’ political activity, or activity that is perceived as political, is likely to result in a risk of persecution or Article 3 ill-treatment, as in the case of HB (see paragraph 3.3.9)

- XX (online), including a person’s position on a “social graph”, whether they are likely to have been the subject of targeted online surveillance, and whether a person has, or is likely to, close their social media account(s) prior to any potential “pinch points”, when basic searches on the person are likely to be carried out (see paragraphs 3.3.12 to 3.3.16, with particular regard to the findings made in respect of Kurdish ethnicity in paragraphs 3.3.14 to 3.3.16).

3.3.2 Where a Kurd’s sur place political activities are likely to be known to the Iranian authorities on return, whether they are opportunistic is unlikely to make a material difference to the risk level faced by that person on return to Iran (BA and XX, see paragraphs 3.3.7 and 3.3.16 respectively). However, where it is unlikely that a Kurd’s sur place political activities are known to the Iranian authorities, the motivation behind the person’s sur place activities is of significance, because a person would not be required to volunteer information about non-genuine political beliefs or activities on return to Iran (S, see paragraphs 3.3.17 to 3.3.18).

3.3.3 Decision makers should also refer to the Country Policy and Information Note, Iran: Social media, surveillance, and sur place activities when considering a case relating to a person of Kurdish ethnicity who participates ‘sur place’ in demonstrations or online activities that are, or are perceived to be, political and against the state of Iran.

3.3.4 Each case must be considered on its facts with the onus on the person to show that they would be at real risk of serious harm or persecution on account of their actual or perceived political opinion or race.

3.3.5 In the Country Guidance case of BA (Demonstrators in Britain – risk on return) Iran CG [2011] UKUT 36 (IAC), heard on 5 and 6 October 2010 and promulgated on 10 February 2011, the UT held that:

‘Given the large numbers of those who demonstrate here and the publicity which demonstrators receive, for example on Facebook, combined with the inability of the Iranian Government to monitor all returnees who have been involved in demonstrations here, regard must be had to the level of involvement of the individual here as well as any political activity which the individual might have been involved in Iran before seeking asylum in Britain.

‘Iranians returning to Iran are screened on arrival. A returnee who meets the profile of an activist may be detained while searches of documentation are made. Students, particularly those who have known political profiles are likely to be questioned as well as those who have exited illegally.

‘There is not a real risk of persecution for those who have exited Iran illegally or are merely returning from Britain. The conclusions of the Tribunal in the country guidance case of SB (risk on return -illegal exit) Iran CG [2009] UKAIT 00053 are followed and endorsed.

‘There is no evidence of the use of facial recognition technology at the Imam Khomeini International airport, but there are a number of officials who may be able to recognize up to 200 faces at any one time. The procedures used by security at the airport are haphazard. It is therefore possible that those whom the regime might wish to question would not come to the attention of the regime on arrival. If, however, information is known about their activities abroad, they might well be picked up for questioning and/or transferred to a special court near the airport in Tehran after they have returned home.

‘It is important to consider the level of political involvement before considering the likelihood of the individual coming to the attention of the authorities and the priority that the Iranian regime would give to tracing him. It is only after considering those factors that the issue of whether or not there is a real risk of his facing persecution on return can be assessed’ (headnotes 1 to 3).

3.3.6 The UT in BA also held that:

‘The following are relevant factors to be considered when assessing risk on return having regard to sur place activities:

‘(i) Nature of sur place activity

- Theme of demonstrations – what do the demonstrators want (e.g. reform of the regime through to its violent overthrow); how will they be characterised by the regime?

- Role in demonstrations and political profile – can the person be described as a leader; mobiliser (e.g. addressing the crowd), organiser (e.g. leading the chanting); or simply a member of the crowd; if the latter is he active or passive (e.g. does he carry a banner); what is his motive, and is this relevant to the profile he will have in the eyes of the regime?

- Extent of participation – has the person attended one or two demonstrations or is he a regular participant?

- Publicity attracted – has a demonstration attracted media coverage in the United Kingdom or the home country; nature of that publicity (quality of images; outlets where stories appear etc)?

‘(ii) Identification risk

- Surveillance of demonstrators – assuming the regime aims to identify demonstrators against it, how does it do so, through filming them, having agents who mingle in the crowd, reviewing images/recordings of demonstrations etc?

- Regime’s capacity to identify individuals – does the regime have advanced technology (e.g. for facial recognition); does it allocate human resources to fit names to faces in the crowd?

‘(iii) Factors triggering inquiry/action on return

- Profile – is the person known as a committed opponent or someone with a significant political profile; does he fall within a category which the regime regards as especially objectionable?

- Immigration history – how did the person leave the country (illegally; type of visa); where has the person been when abroad; is the timing and method of return more likely to lead to inquiry and/or being detained for more than a short period and ill-treated (overstayer; forced return)?

‘(iv) Consequences of identification

- Is there differentiation between demonstrators depending on the level of their political profile adverse to the regime?

‘(v) Identification risk on return

- Matching identification to person – if a person is identified is that information systematically stored and used; are border posts geared to the task?’ (headnote 4)

3.3.7 The UT in BA also held that: ‘While it may well be that an appellant’s participation in demonstrations is opportunistic, the evidence suggests that this is not likely to be a major influence on the perception of the regime.’ (paragraph 65).

3.3.8 The UT in BA additionally held that: ‘… [F]or the infrequent demonstrator who plays no particular role in demonstrations and whose participation is not highlighted in the media there is not a real risk of identification and therefore not a real risk of consequent ill-treatment, on return.’ (paragraph 66).

3.3.9 The factors cited in BA should be taken into account in view of the findings in HB, in that:

‘Even “low-level” political activity, or activity that is perceived to be political, such as, by way of example only, mere possession of leaflets espousing or supporting Kurdish rights, if discovered, involves the same risk of persecution or Article 3 ill-treatment. Each case however, depends on its own facts and an assessment will need to be made as to the nature of the material possessed and how it would be likely to be viewed by the Iranian authorities in the context of the foregoing guidance’ (paragraph 98 (9)).

3.3.10 In the Court of Appeal (EWCA) case of S v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2024] EWCA Civ 1482, heard on 27 November 2024 and promulgated on 6 December 2024, the EWCA considered whether it was necessary for the UT to have considered whether the Appellant in S, an Iranian citizen of Kurdish ethnicity, whose political activities in the UK (demonstrations and Facebook posts) were accepted as opportunistic and not based on genuinely held beliefs, would disclose, or would have to disclose, any of his sur place activities given the likelihood of him being interviewed on return to Iran. It was argued on behalf of the Appellant in S that the UT ought to have considered the type of issues which Lord Dyson mentioned in the case of RT (Zimbabwe) v SSHD [2012] 1AC 152, (“RT”) (paragraph 57) before being properly able to reach a view as to the risk to the appellant on his return to Iran. In particular, it was argued on behalf of S that the UT ought to have considered what the Appellant might be asked by the authorities on his return to Iran and how well he would be able to lie to them. The EWCA held that:

‘… [A]s was pointed out in XX at (98), the issues which the Supreme Court were considering in RT, arose in a very different context, namely the return of a non-political Zimbabwean to an area in which it was likely that he would have to provide a convincingly false account of his allegiance to the ruling party when stopped and questioned by ill-disciplined militia at roadblocks.

‘In contrast, as was pointed out in XX at (99) the Iranian authorities do not persecute individuals because of their political neutrality. Moreover, in the present case, and in the light of both the retained findings and those made by [UT] Judge Kebede as to the unlikelihood of the appellant having already come to the attention of the authorities and his lack of genuine political belief in the PJAK, the appellant was not in a position where he would have to prove his political loyalty, rather it would be one in which, as Judge Kebede found, the appellant would not be required to volunteer information about his activities in the UK.

‘… In my judgment … these finding[s] were ones which the [UT] judge was entitled to find on the basis of the evidence before her, and were reached in accordance with the relevant country guidance.’ (paragraphs 55 to 57).

3.3.11 In the country guidance case XX (PJAK – sur place activities - Facebook) Iran CG [2022] UKUT 23 (IAC), heard 8 to 10 June 2021 and promulgated on 20 January 2022, the UT held that:

‘The cases of BA (Demonstrators in Britain – risk on return) Iran CG [2011] UKUT 36 (IAC); SSH and HR (illegal exit: failed asylum seeker) Iran CG [2016] UKUT 00308 (IAC); and HB (Kurds) Iran CG [2018] UKUT 00430 continue accurately to reflect the situation for returnees to Iran. That guidance is hereby supplemented on the issue of risk on return arising from a person’s social media use (in particular, Facebook) and surveillance of that person by the authorities in Iran’ (paragraph 120).

3.3.12 Regarding surveillance by the Iranian authorities, in the country guidance case XX the UT held that: - Surveillance

‘There is a disparity between, on the one hand, the Iranian state’s claims as to what it has been, or is, able to do to control or access the electronic data of its citizens who are in Iran or outside it; and on the other, its actual capabilities and extent of its actions. There is a stark gap in the evidence, beyond assertions by the Iranian government that Facebook accounts have been hacked and are being monitored. The evidence fails to show it is reasonably likely that the Iranian authorities are able to monitor, on a large scale, Facebook accounts. More focussed, ad hoc searches will necessarily be more labour-intensive and are therefore confined to individuals who are of significant adverse interest. The risk that an individual is targeted will be a nuanced one. Whose Facebook accounts will be targeted, before they are deleted, will depend on a person’s existing profile and where they fit onto a “social graph;” and the extent to which they or their social network may have their Facebook material accessed.

‘The likelihood of Facebook material being available to the Iranian authorities is affected by whether the person is or has been at any material time a person of significant interest, because if so, they are, in general, reasonably likely to have been the subject of targeted Facebook surveillance. In the case of such a person, this would mean that any additional risks that have arisen by creating a Facebook account containing material critical of, or otherwise inimical to, the Iranian authorities would not be mitigated by the closure of that account, as there is a real risk that the person would already have been the subject of targeted on-line surveillance, which is likely to have made the material known.

‘Where an Iranian national of any age returns to Iran, the fact of them not having a Facebook account, or having deleted an account, will not as such raise suspicions or concerns on the part of Iranian authorities.

‘A returnee from the UK to Iran who requires a laissez-passer or an emergency travel document (ETD) needs to complete an application form and submit it to the Iranian embassy in London. They are required to provide their address and telephone number, but not an email address or details of a social media account. While social media details are not asked for, the point of applying for an ETD is likely to be the first potential “pinch point, ” referred to in AB and Others (internet activity - state of evidence) Iran [2015] UKUT 257 (IAC). It is not realistic to assume that internet searches will not be carried out until a person’s arrival in Iran. Those applicants for ETDs provide an obvious pool of people, in respect of whom basic searches (such as open internet searches) are likely to be carried out’ (paragraphs 121 to 124).

3.3.13 For further information and guidance on Facebook and social media use, see the Country Policy and Information Note on Iran: Social media, surveillance and sur place activities.

3.3.14 The UT in XX acknowledged that ‘… the Iranian state targets dissident groups, including religious and ethnic minorities, such as those of Kurdish ethnic origin’ (paragraph 85).

3.3.15 In respect of the finding that a person of significant interest is, in general, reasonably likely to have been the subject of targeted Facebook surveillance, the UT in XX added:

‘We refer to the level of political involvement of an individual, as in BA and HB; and the nature of “real-world” sur place activity, which would prompt such surveillance. By way of summary, relevant factors include: the theme of any demonstrations attended, for example, Kurdish political activism; the person’s role in demonstrations and political profile; the extent of their participation (including regularity of attendance); the publicity which a demonstration attracts; the likelihood of surveillance of particular demonstrations; and whether the person is a committed opponent’ (paragraph 92).

3.3.16 In XX the Upper Tribunal also found, ‘Discovery of material critical of the Iranian regime on Facebook, even if contrived, may make a material difference to the risk faced by someone returning to Iran. The extent of the risk they may face will continue to be fact sensitive. For example, an Iranian person of Kurdish ethnic origin may face a higher risk than the wider population’ (paragraph 103).

3.3.17 Also pointed out in the case of XX, and upheld in the EWCA case of S, the Iranian authorities do not persecute individuals because of their political neutrality. The EWCA found in S that where a person has carried out sur-place activities for reason(s) other than a genuinely held political belief, and where it is unlikely that the person has already come to the attention of the Iranian authorities, the person would not be required to volunteer information about their activities in the UK on return to Iran (see also paragraph 3.3.10).

3.3.18 The EWCA in S also held, in view of the finding on the non-genuine nature of the appellant’s activity, that ‘… there was no reason why the appellant could not close his Facebook accounts prior to the first pinch-point, when he applied for his emergency travel document, nor why he should disclose the existence of them, which would not have previously been known to the authorities, as like his attendance at demonstrations, their apparent contents did not reflect any genuinely held belief by the appellant …’ (paragraph 49).

3.3.19 The country information in this note and in the Country Policy and Information Note on Iran: Social media, surveillance and sur place activities does not indicate that there are ‘very strong grounds supported by cogent evidence’ to justify a departure from these findings.

3.3.20 For further guidance on assessing risk, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

4. Protection

4.1.1 Where the person has a well-founded fear of persecution or serious harm from the state, they will not, in general, be able to obtain protection.

4.1.2 For further guidance on assessing state protection, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status

5. Internal relocation

5.1.1 Where the person has a well-founded fear of persecution or serious harm from the state, they will not, in general, be able to internally relocate to escape that risk.

5.1.2 For further guidance on internal relocation and factors to consider, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

6. Certification

6.1.1 Where a claim is refused, it is unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

6.1.2 For further guidance on certification, see Certification of Protection and Human Rights claims under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 (clearly unfounded claims).

Country information

About the country information

This section contains publicly available or disclosable country of origin information (COI) which has been gathered, collated and analysed in line with the research methodology. It provides the evidence base for the assessment which, as stated in the About the assessment, is the guide to the current objective conditions.

The structure and content follow a terms of reference which sets out the general and specific topics relevant to the scope of this note.

This document is intended to be comprehensive but not exhaustive. If a particular event, person or organisation is not mentioned this does not mean that the event did or did not take place or that the person or organisation does or does not exist.

The COI included was published or made publicly available on or before 18 August 2025. Any event taking place or report published after this date will not be included.

Decision makers must use relevant COI as the evidential basis for decisions.

7. Kurds - Background

7.1 History

7.1.1 For a brief history of Kurds and the Kurdish region of Iran, see the undated articles, ‘Kurdish History’ and ‘Iran (Rojhelat or Eastern Kurdistan)’, published by The Kurdish Project, ‘a cultural-education initiative to raise awareness in Western culture of Kurdish people’.[footnote 1]

7.2 Demography

7.2.1 Estimates of the size of the Kurdish population in Iran vary between sources. The Zagros Human Rights Center (Zagros), a Switzerland-based human rights NGO with consultative status with the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC)[footnote 2], submitted a written statement on the situation of Kurds in Iran to the Secretary General prior to the 57th session of the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC). Dated 12 August 2024, the statement noted: ‘In Iran, the Kurds make up approximately 16 to 17% of the population, roughly 14 to 15 million people.’ They mainly reside in the provinces of West Azerbaijan, Kurdistan, Kermanshah, Ilam, Lorestan, and Hamadan, with some also living in the Khorasan provinces.’[footnote 3]

7.2.2 An article published on 27 January 2025 by the American Kurdish Committee (AKC), a non-profit organisation that advocates for US policies ‘that protect Kurdish interests and further American national security’[footnote 4], stated: ‘Second only to Turkey, Iran is believed to have the largest Kurdish population, with estimates ranging from 7 to 10 million … Although they make up roughly 10 percent of Iran’s total population, demographics within Iran are particularly difficult to confirm.’[footnote 5]

7.2.3 An article published on 17 June 2025 by the Kurdish Peace Institute, an independent, nonpartisan, research and policy institute that focuses on Kurds and the Kurdish region of the Middle East[footnote 6], stated: ‘An estimated eight to 10 million Kurds live in Iran, constituting about 10% of the country’s population and about 25% of the 40 million Kurds in the Middle East. They are concentrated in the northwestern regions of the country, including the provinces of Kurdistan, West Azerbaijan, Kermanshah and Ilam. Kurds refer to these regions as Rojhelat, or Eastern Kurdistan.’[footnote 7]

7.2.4 The Kurdish Institute of Paris (Institut Kurde de Paris), described as ‘an independent, non-political, secular organisation, embracing Kurdish intellectuals and artists from different horizons as well as Western specialists on Kurdish Studies’[footnote 8], indicated in an undated article on the Kurdish population that there were around half a million Kurds living in Tehran.[footnote 9]

7.2.5 Minority Rights Group International (MRGI) a ‘human rights organization working with ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities, and indigenous peoples worldwide’[footnote 10] published a profile on Faili Kurds which described them as an ‘… ethnic group historically inhabiting both sides of the Zagros mountain range along the Iraq-Iran border, and can be considered a cross-border population.’[footnote 11]

7.2.6 In June 2024, the European Union Agency for Asylum (EUAA) published a ‘Country Focus’ report on Iran (the EUAA Country Focus report) which cited various sources. Regarding Faili Kurds, the report stated that: ‘In Iran, they reside primarily in the provinces of Kermanshah and Ilam, where they are known as Sawqi, in particular in Ilam province … [however, they] are not considered as citizens in Iran.’[footnote 12]

7.2.7 On 24 July 2023, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade for the Australian Government (DFAT) published its ‘Iran Country Information Report’. It stated: ‘Some [Faili Kurds] are Iranian citizens, however others are registered or unregistered refugees from Iraq. Accurate population estimates for citizens and refugees are not available, however DFAT understands they are not a significant proportion of the population.’[footnote 13] The same DFAT report also stated: ‘Faili Kurds who are citizens of Iran enjoy the same rights as other Iranians.’[footnote 14]

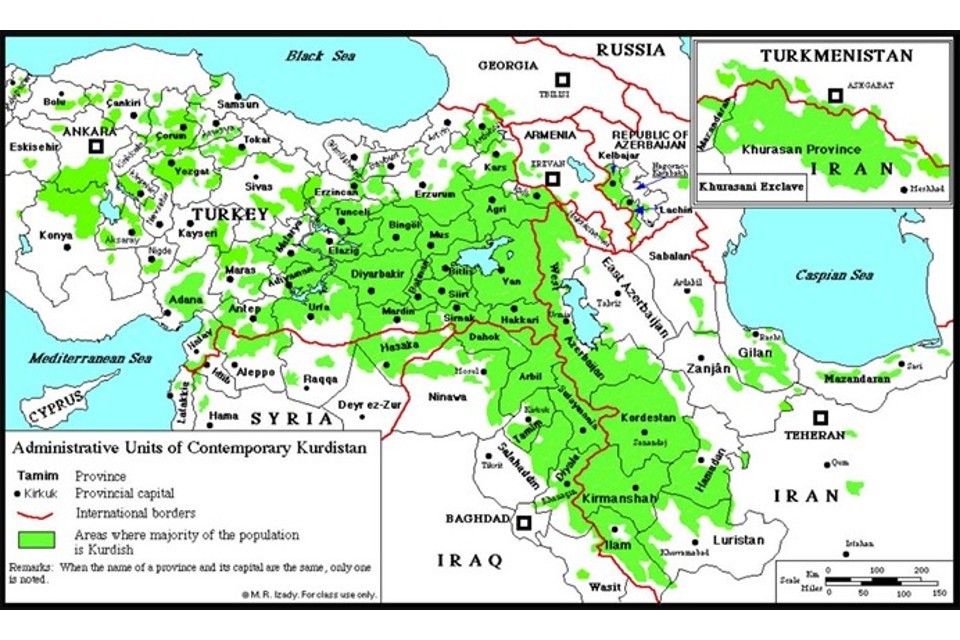

7.3 Maps

NOTE: The maps in this section are not intended to reflect the UK Government’s views of any boundaries.

7.3.1 The below maps show areas with a majority Kurdish population, highlighted in green:

Map showing areas of majority Kurdish settlement

Map showing administrative units of contemporary Kurdistan

7.4 Religion and faith

7.4.1 An undated webpage published by the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO), which described itself as ‘an international membership organization dedicated to empowering unrepresented nations and peoples around the world’[footnote 17], noted the religion of the people of ‘Iranian Kurdistan’ to be: ‘Sunni Muslims 66%, Shi’a Muslims 27%, indigenous and Minority Religions 6% (Yarsan, Yazidis, Yarsan), Christians and Jews.’[footnote 18] The same webpage also stated: ‘The Iranian Kurdistanh population is made up of Shi’a and Sunni, as well as followers of the pre-Islamic Kurdish religion of Yarsan, however, religion does not form a part of the Iranian Kurdistan identity.’[footnote 19]

7.4.2 The Zagros statement to the UN Secretary General, dated 12 August 2024, stated: ‘Religiously, the majority of Kurds in Iran are Muslims, predominantly Sunni, with a notable presence of Shia, as well as adherents of other beliefs such as Yarsanis (Ahl al-Haq [People of Truth[footnote 20]]), Baha’is, and Zoroastrians.’[footnote 21]

7.4.3 The MRGI Faili Kurds profile stated: ‘Unlike the majority of Kurds, who are generally Sunni Muslims adhering to the Shafi’i school of Islam, Faili Kurds are Shi’a Muslims.’[footnote 22]

7.5 Language

7.5.1 An undated entry in the Encyclopaedia Britannica states that the Kurdish language is ‘… a West Iranian language, one of the Indo-Iranian languages, chiefly spoken in Kurdistan. It ranks as the third largest Iranian language, after Persian and Pashto, and has numerous dialects [with 3 main dialects being Kurmanji, Sorani and Palewani[footnote 23]]. It is thought to be spoken by some 20 – 40 million people [mainly in Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria[footnote 24].’[footnote 25]

7.5.2 The Iran Data Portal, an online portal which hosts social science data on Iran in English and Persian and is a US-funded project that is run by a collaboration of academics based outside of Iran[footnote 26], published an English translation of the The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran. It stated: ‘Article 15 (Official Language): The Official Language and script of Iran, the lingua franca of its people, is Persian. Official documents, correspondence, and texts, as well as text-books, must be in this language and script. However, the use of regional and tribal languages in the press and mass media, as well as for teaching of their literature in schools, is allowed in addition to Persian.’[footnote 27]

7.5.3 On 23 April 2024, the USSD published its ‘2023 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices’ (USSD 2023 Country Report) which stated: ‘The constitution provided for equal rights to all ethnic minorities, allowing minority languages to be used in media. The law provided for the right of citizens to learn, use, and teach their own languages and dialects.’[footnote 28] The same report also stated: ‘Authorities did not universally prohibit the use of the Kurdish language’[footnote 29], and ‘The government reportedly banned some Kurdish-language newspapers, journals, and books and punished publishers, journalists, and writers for criticizing government policies …’[footnote 30] The USSD report further stated: ‘The government consistently barred use of minority languages in school for instruction.’[footnote 31] The USSD published its 2024 Iran Country Report on 12 August 2025 but provided no coverage of racial or ethnic violence and discrimination, nor of the education of children.[footnote 32]

7.5.4 An undated article entitled ‘Kurdish language’, published by The Kurdish Project, which cited various sources, stated:

‘Kurdish dialects are broken into three main groups: Northern Kurdish, Central Kurdish and Southern Kurdish.

‘… Northern Kurdish dialects, the most common of which is called Kurmanji, are spoken … in the extreme northern strips of Iranian … Kurdistan [and in Turkey, Syria, the Soviet Union, and Iraqi Kurdistan, where it is known as ‘Behdini’[footnote 33]].

‘… The Central Kurdish dialect, called Sorani, is spoken by Kurds in parts of Iraq and Iran. Sorani is written with the Arabic script, and borrows the spelling of many words from Arabic, although the pronunciation differs.

‘… The third group of regional dialects, Southern Kurdish [also called Pehlewani[footnote 34]], is spoken primarily in Iran and in parts of Iraq. The Southern Kurdish dialect group encompasses over nine sub-dialects.’[footnote 35]

7.5.5 Words of Relief, a crisis response translation service run by Translators without Borders, ‘a global community of over 100,000 language volunteers offering language services to humanitarian and development organizations worldwide’[footnote 36], published an undated Kurdish ‘Language Factsheet’ which noted there were between 5 and 6 million Kurdish Sorani speakers in Iran.[footnote 37]

7.5.6 The undated Encyclopaedia Britannica article went into further detail about the Kurdish Sorani language, stating that ‘… [it] emerged as the major literary form of Kurdish. It is spoken within a broad region that stretches roughly from Orūmīyeh, Iran, to the lower reaches of traditional Kurdistan in Iraq. It is usually written in a modified Perso-Arabic script, though Latin script is increasingly used.’[footnote 38]

7.5.7 The MRGI World Directory published a profile on Kurds which stated: ‘In southern Iran, Gurani which is a distinct language is spoken, but Kurds around Kirmanshah speak a dialect closer to Persian.’[footnote 39]

7.5.8 For more information about the the prohibition of Kurdish language instruction in schools in Iran, see Access to Kurdish education.

7.6 Documentation

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information on this page has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

8. Education and employment

8.1 Access to Kurdish education

8.1.1 On 23 February 2024, Hengaw Organization for Human Rights (Hengaw), an organisation that covers human rights violations across Iran[footnote 40], published an article about Kurdish language teachers in Iran which stated:

‘The Kurdish language, alongside other minority languages, has been marginalized in Iran since the establishment of the modern nation-state. The policy of linguistic homogenization and denial has persisted, with the justification of preventing separatism. Under the rule of the Islamic Republic of Iran, this policy has intensified, with security forces exerting full control over educational, cultural, and judicial policies. The authorities have consistently refused to implement Article 15 of Iran’s Constitution, which minimally acknowledges the right to use minority languages in education. Furthermore, Kurdish language activists who voluntarily teach Kurdish people have faced security charges, leading to their arrest and severe prison sentences.’[footnote 41]

8.1.2 Citing information from Barzoo Eliassi, an associate professor at Linnaeus University in Sweden, with extensive experience on statelessness and Kurdish minorities[footnote 42], the EUAA Country Focus report stated: ‘Kurds do not have the right to education in their mother tongue.’[footnote 43]

8.1.3 The Zagros statement to the UN Secretary General, dated 12 August 2024, stated:

‘The teaching of the Kurdish language is … absent from public schools, occurring only in private settings, posing a major obstacle to the preservation of Kurdish language and culture.

‘… The lack of educational infrastructure and the absence of teaching in the Kurdish mother tongue constitute major obstacles to the education of Kurdish children. The prohibition of Kurdish language instruction in public schools deprives young Kurds of the opportunity to be educated in their native language, threatening the transmission of their culture and identity.’[footnote 44]

8.1.4 On 27 February 2025, Kurdistan 24, a Kurdish multi-media, multi-language news outlet[footnote 45], published an article which stated:

‘The Iranian Parliament has rejected a proposal that aimed to introduce the teaching of non-Persian languages in schools, despite Iran’s diverse ethnic composition.

‘The proposal, put forward by the Parliamentary Committee on Education, Research, and Technology, was struck down with 130 votes against, 104 in favor, and five abstentions, out of 246 members present.

‘… Critics expressed concerns that implementing multilingual education might threaten national cohesion, particularly in border regions where Iran’s ethnic minorities are concentrated.

‘The parliament ultimately recommended further consultations to develop a more comprehensive proposal, with plans to revisit the issue in six months.’[footnote 46] CPIT was unable to find any further updates regarding the bill in the sources consulted (see Bibliography).

8.1.5 On 28 April 2025, Amnesty International (AI) published its annual ‘The State of the World’s Human Rights’ report, covering 2024. The report stated: ‘Persian remained the sole language of instruction in primary and secondary education, despite repeated calls for linguistic diversity.’[footnote 47]

8.2 Employment rates

8.2.1 The July 2023 DFAT report stated: ‘Kurdish-majority areas tend to be relatively underdeveloped. High levels of unemployment have forced many Kurds to undertake smuggling work between Iran and Iraq.’[footnote 48] For more information about Kurds involved in smuggling, see the Country Policy and Information Note, Iran: Smugglers.

8.2.2 The same DFAT report also stated: ‘… [U]ndocumented Faili Kurds are not legally entitled to work …’[footnote 49]

8.2.3 Citing the EUAA’s communications with Barzoo Eliassi, the Country Focus report also stated: ‘… Kurdish regions are sidelined by the Islamic Republic. As there is no work in Kurdish areas, they go to Tehran, Karaj or Tabriz for work. In these cities, authorities often screen Kurds to see to what class or ethnic group they belong to … The many Kurds in Tehran do not belong to any privileged group - political and economic factors push them to leave their regions.’[footnote 50]

8.2.4 The Zagros statement to the UN Secretary General, dated 12 August 2024, stated: ‘Kurdish regions in Iran exhibit some of the highest unemployment rates in the country, a problem exacerbated by economic marginalization and the lack of public investment in these areas.’[footnote 51]

8.2.5 On 14 April 2025, Kurd Press, an Iranian Kurdish news agency[footnote 52], published an article which stated: ‘According to the latest results published by the Statistical Centre of Iran, Kurdistan Province in winter 2024, with an unemployment rate of 13.7 percent, has been introduced as the second most unemployed province in the country. This rate has been recorded while the average unemployment rate in the country was announced as 7.8 percent; a figure that shows Kurdistan’s 5.9 percent difference from the national average.’[footnote 53]

N.B. the information quoted above was originally published in Farsi. All COI from this source has been translated using a free online translation tool. As such 100% accuracy cannot be guaranteed.

8.3 Military service

8.3.1 Military service is compulsory for up to 24 months for all Iranian men aged between approximately 18 to 19 years and approximately 40 years.[footnote 54]

8.3.2 For more information on military conscription see the Country Policy and Information Note, Iran: Military service.

9. Iranian Kurdish political groups

9.1 Political parties

9.1.1 On 3 January 2024, The Jerusalem Post, an English-language daily newspaper and news website in Israel[footnote 55], published an article which stated: ‘Iran has numerous groups that have various causes and reasons to dislike the regime … There are … Kurdish groups that want rights for Kurds in northwest Iran.’[footnote 56]

9.1.2 In September 2023, the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs (BZ, Dutch abbreviation), published a ‘General Country of Origin Information Report on Iran’ (the BZ Iran COI report), covering the period from April 2022, up to and including August 2023.[footnote 57] The report, which cited various sources, stated:

‘… [D]uring the reporting period a number of the Kurdish political parties engaged in activities had their bases in the Kurdish region of Iraq. All of these parties are illegal in Iran. The authorities consider all Kurdish parties to be terrorist organisations …

‘A number of these Kurdish parties are listed below. This overview is by no means exhaustive.

- ‘the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (PDKI) This party is working for Kurdish autonomy in a federal and democratic Iran.

- ‘the Free Life Party of Kurdistan (PJAK). PJAK has ideological ties with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) [a ‘militant Kurdish nationalist organization founded by Abdullah (“Apo”) Öcalan in the late 1970s’[footnote 58]]. This party seeks self-governance for Kurds in Syria, Iraq, Türkiye and Iran.

- ‘the Komala Party of Iranian Kurdistan (Komala-PIK). Like the PDKI, this party is working for a federal and democratic Iran.

- ‘the Komala Communist Party of Iran (Komala-CPI). This party consists of a faction led by Ibrahim Alizadeh and a smaller faction led by Salah Mazoji.

- ‘the Kurdistan Freedom Party (PAK). This party is working for a large, independent Kurdistan.’[footnote 59]

9.1.3 On 24 November 2022, the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation (ACCORD) published a report about the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (PDKI), Komala, and other Iranian opposition political parties (The ACCORD Iranian opposition parties report), which, citing various sources, stated:

‘In January 2018, six political organisations (PDKI, [Kurdistan Democratic Party – Iran] KDP-I, Komala [PIK], [Komala Kurdistan Toilers’ Party] Komala KTP, [Communist Party of Iran] CPI [see sections 11 and 13], and Khabat [The Organization of Iranian Kurdistan Struggle[footnote 60]]) founded the Cooperation Centre of Iranian Kurdistan’s Political Parties (CCIKPP). Due to differences, CPI and Khabat left the cooperation centre. Both PDKI and Komala-KTP published news in September and October 2022, respectively, in the name of the CCIKPP using the following logo:

N.B. the information quoted above, and all other COI quoted from this source throughout the rest of this CPIN was originally published in German. All COI from this source has been translated using a free online translation tool. As such 100% accuracy cannot be guaranteed.

9.1.4 On 13 September 2023 the Fikra Forum, ‘an initiative of the Washington Institute [for Near East Policy, TWI] designed to provide on-the-ground perspectives and insight on the most pressing current events facing the Middle East’[footnote 62], published an article by Wladimir van Wilgenburg, a political analyst based in Erbil in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) since 2014.[footnote 63] The article stated: ‘Most of the Iranian Kurdish parties are located in areas controlled by the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) [in the KRI], apart from fighters of the Kurdistan Free Life Party (PJAK) …’[footnote 64]

9.1.5 An article published on 19 July 2024 by RFE / RL stated: ‘Many offices of Kurdish parties [along Iraqi Kurdistan’s eastern border with Iran] that oppose Tehran have since [March 2023] been shut down.’[footnote 65]

9.1.6 The EUAA Country Focus report noted that according to Barzoo Eliassi, between 1 January 2023 and 17 April 2024, Kurdish anti state resistance groups in Iran did not have territorial control.[footnote 66]

9.1.7 On 30 March 2025, an article posted on IranNews.ge, a news platform run by a self-described ‘independent group of activists and specialists’[footnote 67] stated: ‘In a sense, compared to some other ethnic groups (such as Arabs or Baluchis), Iranian Kurds have more cohesive political parties and organizations, which is the result of decades of efforts by Komala and other groups.’[footnote 68]

9.2 Political activities in Iran

9.2.1 According to sources consulted by the DIS for a report it published on Iranian Kurds in February 2020, when referring to the activities of members and supporters of Iranian Kurdish parties:

‘The level of civil political activities conducted by the Iranian Kurdish opposition parties, specifically [the Kurdish Democratic Party of Iran] KDPI [also known as the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (PDKI)[footnote 69], see also Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (PDKI) / Kurdistan Democratic Party of Iran (KDPI / KDP-I)] and Komala [see Komala] in Iran is generally limited due to the scrutiny they are faced with. When the parties do conduct civil political activities, this is done in secrecy to prevent the authorities clamping down on them. However, the parties support the activities of others, such as organisations that focus on environmental issues as well as social issues.

‘The Kurdish political parties are conducting propaganda activities to create awareness regarding the Iranian government’s policies, encouraging people to protest by various peaceful and resolution oriented methods, such as demonstrations, general strikes and symbolic means, like wearing Kurdish clothes on special occasions.

‘Most activities carried out by the Kurdish parties take place in public spaces, including schools. For instance, when the anniversary of the assassination of KDPI leader Abdul Rahman Ghassemlou occurs or the anniversary of the foundation of Kurdistan Republic in Iran, letters are hung on government buildings to inform people of these anniversaries. The parties usually encourage their members, supporters and the public to undertake actions through social media, TV, and radio channels.’[footnote 70]

9.2.2 The July 2023 DFAT report stated: ‘Some groups that advocate for Kurdish separatism are non-violent. In-country sources told DFAT most Kurds accept that a separate Kurdish state within Iran is not a realistic goal and that most Kurds are not involved in armed separatism.’[footnote 71]

9.2.3 The EUAA Country Focus report stated: ‘As noted by [expert] Barzoo Eliassi … Kurdish groups have rather chosen to conduct political activities rather than military confrontation …’[footnote 72]

9.2.4 The Kurdish Peace Institute article, published on 17 June 2025, stated:

‘Today, several significant Kurdish opposition parties exist. These groups have waged on-and-off armed campaigns against the Iranian state and engage in political organizing both clandestinely within Iran and openly in exile.

‘… All major Iranian Kurdish parties demand the overthrow of the Islamic Republic. PDKI, Komala, and PJAK call for Kurdish national rights within a democratic, secular, federal Iran, while PAK calls for the creation of an independent Kurdish state. The parties have expressed interest in collaborating with other opposition groups in Iran and, in particular, with other ethnic minorities.’[footnote 73]

9.2.5 CPIT was unable to find any recent information in the sources consulted (see Bibliography) on whether or, if so, to what extent, Kurdish political groups in Iran produce, print, and/or distribute written political materials, such as leaflets. For historic information on this topic, see the previous version of this CPIN (Version 4.0), published in May 2022 and pages 13 to 14 of a joint report published in September 2013 by the Danish Immigration Service (DIS) and the Danish Refugee Council (DRC), about a joint fact-finding mission they conducted in Erbil and Sulaimania, Iraq, between May and June 2013.[footnote 74]

9.2.6 For more information on political activities see the relevant sub-sections for each of the political parties, PDKI/KDPI/KDP-I – Activities and roles of members and supporters, Komala activities and PJAK – Membership structure and activities.

9.3 Kurdish military activity

9.3.1 An article published by ACLED on 6 July 2023, stated: ‘Several Iranian Kurdish armed groups – including PJAK and others – have been engaged in armed struggle against the Iranian government for decades demanding cultural rights, autonomy, and in some cases, outright independence.’[footnote 75]

9.3.2 The Kurdish Peace Institute article, published on 17 June 2025, stated: ‘All major Iranian Kurdish parties … have engaged in armed conflict with the Iranian state at various points in their history … Local and international media reports indicated an uptick in young Kurdish men and women joining armed groups in response to the 2022 “Women, Life, Freedom” uprising. However, no Iranian Kurdish armed force took direct action against the state this time, likely to avoid inviting further retaliation against protestors.’[footnote 76]

9.3.3 The July 2023 DFAT report stated:

‘Various groups are involved in armed separatist insurgency. Groups including the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan, Kurdistan Free Life Party (KFLP), Komala and Kurdistan Freedom Party. Although all groups fight for a separate Kurdistan, their activities can be diverse. For example, some fight in Iraq or were involved in the fight against Islamic State. Other groups have no such affiliation but may be separately recognised as terrorist groups, including the KFLP which is designated by the United States (but not by Australia [nor by the UK[footnote 77]]) as a terrorist group.’[footnote 78]

9.3.4 The RFE / RL article, published on 19 July 2024, stated:

‘… Tehran has long accused unspecified Kurdish opposition groups, without providing evidence, of coordinating with Israel, its archfoe, to stage attacks on Iran from Iraqi Kurdistan. Kurdish opposition groups deny the allegation … In a security pact agreed between Tehran and Iraq’s central government in March 2023, Baghdad agreed to secure Iraqi Kurdistan’s lengthy eastern border with Iran, as well as to disarm and relocate Iranian-Kurdish opposition groups based in the region.’[footnote 79]

9.3.5 In an article, updated on 4 November 2024, the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), which describes itself as, ‘an independent, impartial global monitor that collects, analyses, and maps data on conflict and protest’[footnote 80], noted the main armed Kurdish groups represented in the ACLED Middle East Actor File for Iran were:

- ‘KSZK: Komala Party of Iranian Kurdistan …

- ‘HAK-R: Kurdistan Freedom Eagles for East Kurdistan [the armed peshmerga units of the Kurdistan Freedom Party (PAK)[footnote 81] …

- ‘PDKI: Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan …

- ‘PJAK: Kurdistan Free Life Party …

- ‘YRK: Eastern Kurdistan Units [the armed wing of the Kurdistan Free Life Party (PJAK)[footnote 82]] …’[footnote 83]

9.3.6 On 15 September 2023, The New Arab (TNA), a London-based ‘English-language news and current affairs website’ covering the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region[footnote 84], published an article which stated:

‘In a significant development, authorities in the Iraqi Kurdistan region have reportedly taken steps to disarm and relocate factions of Iranian Kurdish opposition groups from their bases in northern Iraq, Kurdish sources revealed to The New Arab on Thursday, 14 September [2023], marking a notable shift in regional dynamics.

‘… According to exclusive information obtained by TNA, Kurdish descendants living in Iran have widely gained access to smuggled weapons from the Iraq-Iran borders, and in case of any rebellion, it would not be easy for Iran to overcome local turmoils.

‘Iran accuses the Iranian Kurdish parties of “affiliating” with Israel; Iran often voices concern over the alleged presence of the Israeli spy agency Mossad in the semi-autonomous Kurdish region. Iran moves heavy weapons along borders with Iraqi Kurdistan.

‘The Islamic regime also accused Kurdish parties of stoking the nationwide protests triggered by the death in custody in September [2022] of Iranian Kurdish woman Mahsa Amini.

‘Kurdish groups, in turn, strongly deny these accusations, saying that their activities are mainly “peaceful”.’[footnote 85]

9.3.7 The BTI 2024 Iran report stated: ‘Iran’s government accuses Kurdish (and other) armed groups of separatism, terrorism and “relations with foreigners.” These groups in turn accuse the Islamic Republic of violating the rights of Iranian Kurds and claim to defend the rights of the Kurds.’[footnote 86]

9.3.8 A June 2024 fact-finding mission report published by the Danish Immigration Service (DIS), entitled ‘Iranian Kurds in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq’ (the DIS FFM report), which cited various sources, stated:

‘Sources differed on whether the Iranian Kurdish parties have been disarmed …[An] Iranian Kurdish scholar did not have actual knowledge on whether the parties have been disarmed, but stated that official statements from Iran, Iraq and KRG prevail. Iran has thanked both Baghdad and the KRG for their assistance in making the Iranian Kurdish parties disarm, implying that both relocation and disarmament have taken place in accordance with the official announcements. A local human rights NGO also stated that disarmament has taken place, but the source was unaware of the fate of the weapons. An International Organisation in Iraq also stated that the Iranian Kurdish parties made the decision to disarm, have confirmed that they have disarmed, and that there is no evidence that contradicts this. The Iranian Kurdish parties, however, want to keep small arms for personal protection.

‘In contrast to the above, according to [political analyst] Wladimir van Wilgenburg, most of the Iranian Kurdish parties have not been disarmed.’[footnote 87]

9.3.9 The Kurdish Peace Institute article, published on 17 June 2025, stated: ‘It is unclear the degree to which each party has military forces present in Iran now.’[footnote 88]

9.3.10 An article published by TNA, also on 17 June 2025, stated:

‘In the days after the Israel-Iran war began [on 13 June 2025[footnote 89]], all four [of the main Iranian Kurdish] parties [KDPI, Komala, PAK and PJAK] called on the Kurdish people to work for the collapse of the Iranian regime. However, some were blunter about whether this should be achieved through immediate armed struggle.

‘“We call on all forces, parties, and civil society organisations - with Iranian women at the forefront - to launch a new phase of the “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” [Women, Life, Freedom] revolution. We declare our readiness to help initiate it,” PJAK said in a statement on 14 June [2025].

‘Far more militantly, PAK leader Hussein Yazdanpana urged Kurdish youth “to seize IRGC and intel bases” in the Kurdish provinces.’[footnote 90]

10. Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (PDKI)

10.1 Background

10.1.1 It should be noted that a number of sources referred, and continue to refer, to the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (PDKI) and the Kurdistan Democratic Party of Iran / the Kurdistan Democratic Party - Iran (KDPI / KDP-I), and other close iterations of these names, interchangeably to describe the same party.[footnote 91] The country information in this note is therefore reflective of this practice.

10.1.2 The ACCORD Iranian opposition parties report stated: ‘In 2006 … [a] dispute over the election of their next chairman led to some senior members leaving the party. Under the leadership of Khalid Azizi, they founded the Iranian Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP, also KDP-I to distinguish it from the KDP in Iraq). During the split, the party removed the word Iran from its Kurdish and Persian original names … The KDP-I remained ideologically linked to the [Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan] PDKI.’[footnote 92]

10.1.3 In 2022, the PDKI and the KDP-I reunited; as Kurdistan 24 reported on 22 August 2022: ‘Two Iranian Kurdish parties on Sunday [21 August 2022] announced that they unified their parties again, after 16 years of being separated. The Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (PDKI) and the Kurdistan Democratic Party – Iran (KDP-I) decided to reunite again after long negotiations. The parties in a joint statement said … “The people of East Kurdistan (Iranian Kurdistan) never accepted this separation and did not recognize it officially,” …’[footnote 93]

10.1.4 A Rudaw article published on 21 August 2022, citing the parties’ joint statement, noted: ‘Going forward, the party’s organizations and bodies will reunite and resume under the name of the KDPI and through the “guidance of a common leadership” and “bilateral agreements” …’[footnote 94]

10.1.5 The Kurdistan Democratic Party of Iran (KDPI) is an Iranian-Kurdish opposition group based in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI).[footnote 95] It is the oldest and largest of the four main Iranian Kurdish parties[footnote 96], having been established in August 1945 by ‘notable Kurdish figure’, Qazi Muhammad.[footnote 97]

10.1.6 On its own website, the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (PDKI) describes itself as a social democratic party with the stated aim of attaining ‘Kurdish national rights within a federal and democratic Iran.’[footnote 98]

10.1.7 On 4 December 2023, citing various sources, the Norwegian Country of Origin Information Centre, Landinfo, published a query response which stated that the PDKI ‘fought an armed struggle for control over the Kurdish areas in northwestern Iran following the Iranian revolution in 1979, but were driven out of the country by Iranian government forces in the first half of the 1980s. Since then, the parties have operated from exile bases in Iraq and have only had a clandestine existence in Iran.’[footnote 99]

N.B. the information quoted above, and all other COI quoted from this source throughout the rest of this CPIN was originally published in Norwegian. All COI from this source has been translated using a free online translation tool. As such 100% accuracy cannot be guaranteed.

10.1.8 A September 2023 article published by Amwaj.media, a UK-based news website that covers Iran, Iraq and the countries of the Arabian Peninsula[footnote 100], noted Mustafa Hijri as the leader of the KDPI, and included the below logo for the party[footnote 101]:

10.1.9 For the logo of the formerly-separate KDP-I party, see page 8 of the ACCORD report, published in November 2022. Khalid Azizi, the former leader of the KDP-I became the spokesperson and head of external relations for the newly merged KDPI party.[footnote 102]

10.1.10 The same Amwaj.media article stated: ‘… [S]ome reports have emerged that the KDPI and Komala have left the mountains near the Iranian border district of Piranshahr, destroying their bases in the process. Iraqi officials have also separately confirmed that Kurdish fighters are now being moved away from the border area.’[footnote 103]

10.1.11 The DIS FFM report stated ‘… [S]ources agreed that PDKI is located in Erbil Governorate, but their exact location is disputed. A local Human Rights Organisation claimed PDKI is now based outside Erbil, while Wladimir van Wilgenburg stated that PDKI was near Koye and near Baharka in Erbil Governorate. An International Organisation in Iraq informed the delegation that PDKI was relocated to two camps in unspecified locations in Erbil Governorate.’[footnote 104]

10.1.12 The DIS FFM report also noted that according to Wladimir van Wilgenburg, the PDKI retained its weapons despite the Iran-Iraq Border Security Agreement (see paragraph 9.3.4 and section 3.1.1 of the DIS report for further information).[footnote 105]

10.1.13 The March 2025 IranNews.ge article stated: ‘The Democratic Party, with its longer history [than Komala] and charismatic figures … has a major share in the political authority of the Kurds.’[footnote 106]

10.2 Membership structure and recruitment

10.2.1 CPIT found limited recent information on membership structure and recruitment into the PDKI / KDPI in the sources consulted (see Bibliography). For historic information on this topic, see the previous version of this CPIN (Version 4.0), published in May 2022.

10.2.2 The ACCORD Iranian opposition parties report stated:

‘The PDKI has a network of members and supporters in Iran. According to representatives of the PDKI, members in Iran are organised into secret cell structures. Each city has its own separate organisational structure. Members in the cells are not allowed to know other members outside the cell and only receive the information necessary to perform their tasks. A cell can consist of one, three, or five members (and in the past between three and nine).

‘… The organisational structure in Iran is completely separate from the organisational structure in northern Iraq …’[footnote 107]

10.2.3 The DIS report on Iranian Kurds, dated February 2020, cited the Kurdistan Human Rights Association – Geneva (KMMK-G), an independent non-affiliated association, who said in regard to recruiting PDKI members in Iran that training for new members is conducted in Koya and Qandil (on the Iran/Iraq border).[footnote 108]

10.2.4 According to the KMMK-G:

‘The training course takes 3 months. It includes the teaching of Kurdish language, Kurdish history, the political party’s history takes and geopolitics. Then according to the new comers’ educational background, s/he will be sent to different departments. For instance, if the new comer is a journalist, s/he will be sent to KDPIs media department.

‘The newcomers come voluntarily due to the fact that the level of repression is very high in Iranian Kurdistan and they have lost hope in reforms within the system; in addition to the repression, they suffer also discrimination because of the “Gozinesh” law [mandatory pre-employment screening that assesses adherence to Islam and loyalty to the Islamic Republic[footnote 109]]. KDPI generally encourage people, especially highly educated volunteers, to stay in Iran to work for KDPI in order to reinforce the party’s presence in the villages and towns. It is also costly and requires space to house recruits in the bases in Iraqi Kurdistan.’[footnote 110]

10.2.5 Sources in a Landinfo report on the PDKI, published in April 2020, indicated that new members in Iran were usually recruited on recommendation, that background checks were made, and they were monitored for a period of time before acceptance into the party:

‘Recruitment within Iran usually occurs through acquaintances. Those who wish to become members of the party need recommendations from other members to gain approval. There is no fixed trial period before being accepted as a member. Those being considered for membership are often monitored over a period, and a background check is conducted before they are accepted as members of a secret cell. An Iranian-Kurdish journalist who became a member of a secret PDKI cell while living in Iran explained that he was contacted by acquaintances and asked if he would join the party. He was privately teaching Kurdish language at the time and was well-known among educated Kurds in the area. He also explained that those being considered for membership were typically observed over a period, and a background check was conducted to try to prevent Iranian intelligence from infiltrating the cells.’[footnote 111]

N.B. the information quoted above, and all other COI quoted from this source throughout the rest of this CPIN was originally published in Norwegian. All COI from this source has been translated using a free online translation tool. As such 100% accuracy cannot be guaranteed.

10.2.6 The same Landinfo report referred to a youth group belonging to the party: ‘The party has its own youth organisation, Lawan, for members between the ages of 15 and 35. Lawan has offices in the Azadi camp [northern Iraq] and operates both in the KRI and inside Iran. The youth organisation also has offices in various European countries …’[footnote 112]

10.2.7 The ACCORD Iranian opposition parties report also noted the Democratic Youth Union of Iranian Kurdistan (Lawan) as an organisation affiliated with the party, in addition to the Democratic Women Union of Kurdistan, and the Democratic Students Union of Kurdistan.[footnote 113] For the logos of the Democratic Women Union of Kurdistan and the Democratic Students Union of Kurdistan, see page 11 of the ACCORD Iranian opposition parties report.

10.2.8 In May 2017, a report about Iranian Kurdish militias was published by the Combating Terrorist Center at West Point (CTC), which researches, trains, and advises on terrorism and counterterrorism-related matters.[footnote 114] The report stated: ‘Outside of official sources, the numbers on armed Iranian Kurds remain opaque and should be considered best-guess estimates and averages. The KDPI may have 1,000-1,500 fighters …’[footnote 115]