Infection prevention and control: resource for adult social care

Updated 1 March 2024

Applies to England

Introduction

This resource contains general infection prevention and control (IPC) principles to be used in combination with advice and guidance on managing specific infections. It is for those responsible for setting and maintaining standards of IPC within adult social care in England.

Adult social care is a broad term covering a wide range of activities, outside of NHS-provided services, which help people who are older, living with disability or physical or mental illness, or people with a learning disability to live independently and stay well and safe.

Preventing and reducing the transmission of infectious diseases is essential to ensuring people stay healthy. People who have contact with social care should have confidence in the cleanliness and hygiene of services and services provided. Not all the contents of this resource will be applicable to every situation or type of care and support. This resource should be used as a guide in the practice of adult social care, to ensure people receive person-centred support that follows effective IPC measures.

Antimicrobial resistance is a global problem that makes infections harder to treat with existing medicines. High standards of IPC reduce the opportunities for infections to spread and for resistance to develop.

The term ‘pathogen’ is used throughout to describe microorganisms or germs which can infect people and cause disease. Within this resource, the terms ‘people’ and ‘person’ are used to describe anyone drawing on adult social care or support. The term ‘worker’ is used to describe anyone providing adult social care or support. Unpaid carers are family and friends who provide care to loved ones. Information within this resource may be useful to unpaid carers.

IPC practices should be based on person centred care and the best available evidence and guidance - see appendix 1 (below) for further information. This document does not replace any clinical or public health advice. The information within this resource draws upon several sources including the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE), NHS, government departments and professional regulators. Providers registered with the Care Quality Commission (CQC) must comply with the regulations and consider the Code of Practice for the prevention and control of infections in the delivery of their services.

1. Preventing infection

Chain of infection

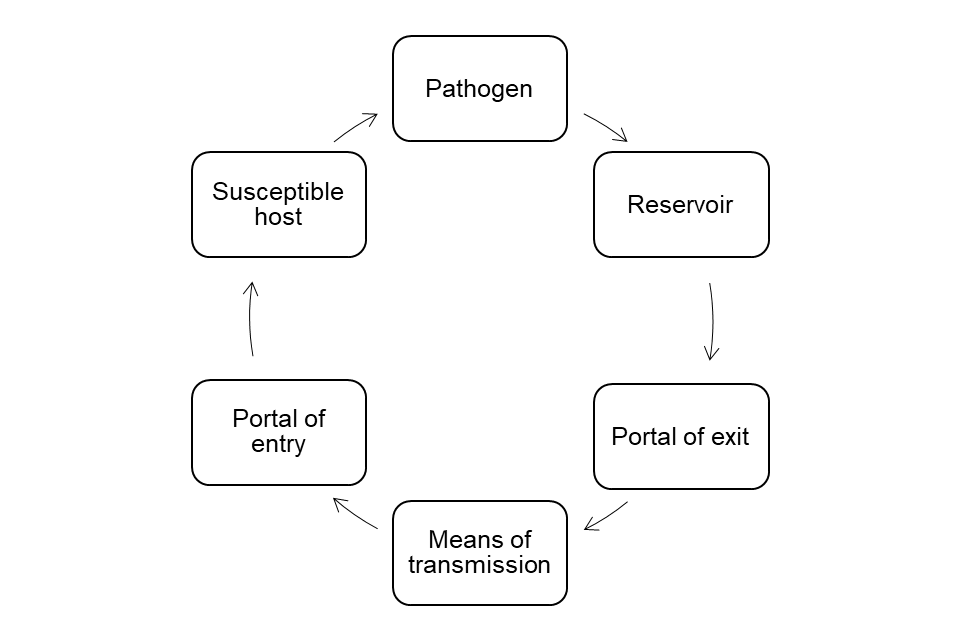

Understanding how infection is spread is crucial for effective IPC. The chain of infection contains 6 links (see the image below). There are opportunities to break the chain at any link, and the more links that are broken the greater the protection.

The links are pathogen, reservoir, portal of exit, means of transmission, portal of entry and susceptible host.

The 6 links are:

- pathogen

- reservoir

- portal of exit

- means of transmission

- portal of entry

- susceptible host

A pathogen is the micro-organism or germ that causes disease. For example, norovirus can cause diarrhoea and vomiting, or the influenza virus can cause flu.

A reservoir is where pathogens live and replicate. For example, this could be a person, the environment or food and drink.

A portal of exit is how pathogens leave the reservoir. This could be through coughs and sneezes of someone with a respiratory illness such as flu, or through the faeces or vomit of someone with gastroenteritis (diarrhoea and vomiting).

A means of transmission is how pathogens are moved from one person or place to another. This could be from one person’s hands to another person, through touching a contaminated object, through the air, or contact with blood or body fluids.

A portal of entry is how pathogens enter another person. This could be by inhalation, through mucus membranes (linings of the nose and mouth), or via a wound or invasive device such as a catheter.

Susceptible host is the person who is vulnerable to infection. This could be for a variety of factors such as age, lack of immunity, or underlying health conditions.

Table 1: examples of breaking the chain

| Link | Example of breaking the chain |

|---|---|

| Pathogen | Completing prescribed course of antibiotics reduces the opportunity for the pathogen to become resistant to treatment. |

| Reservoir | Regular cleaning or decontamination requirements will reduce the number of pathogens present in the environment and on equipment. Isolation or distancing, keeping away from others when infectious, reduces the opportunity for the pathogen to find a new host (reservoir). |

| Portal of exit | Covering nose and mouth when coughing or sneezing reduces the chances of spread of respiratory infections. Having dedicated toilet facilities and access to vomit bowls reduces the chances of spread of gastrointestinal infections. |

| Means of transmission | Hand hygiene removes many pathogens and stops them moving between people. Ventilation can help dilute certain pathogens such as viruses which cause respiratory illness. |

| Portal of entry | Fluid repellent surgical face masks and eye protection reduce the risks of pathogens entering the body through mucus membranes. Ensure any wounds are covered and only use indwelling devices, such as catheters, when absolutely necessary. |

| Susceptible host | Vaccination helps fight off infection and prevent disease, illness and death. |

Infection risk assessment

Assessing a person’s risk of catching or spreading an infection and providing them with information about infection is essential in supporting safety.

An assessment of a person’s risk of infection should be carried out before they start using the service and should be kept under review for as long as they use the service. The assessment should contribute to the planning of the person’s care and should determine whether any extra IPC precautions are required, such as whether they need to isolate or whether workers need to wear additional personal protective equipment (PPE). The assessment should include all factors which place the person at a higher risk of catching or spreading infection and may include:

- symptoms:

- history of current diarrhoea or vomiting

- unexplained rash

- fever or temperature

- respiratory symptoms, such as coughing or sneezing

- contact:

- previous infection with a multi-drug resistant pathogen (where known)

- recent travel outside the UK where there are known risks of infection

- contact with people with a known infection

- person risk factors:

- vaccination status which will assist assessment of their susceptibility to infection and allow protective actions to be taken when necessary

- wounds or breaks in the skin

- invasive devices such as urinary catheters

- conditions or medicines that weaken the immune system

- environmental risk factors, such as poor ventilation in the care setting

Reducing risk

The hierarchy of controls is a system that helps to reduce risk at work. Its principles can be broadly interpreted for social care settings under the following headings:

- reducing the hazard

- changing what we do

- changing where we work

- changing how we work

- use of PPE

These controls are ranked in the order of effectiveness. PPE is the last control in the hierarchy, used when all other controls have not reduced the risks sufficiently. To be effective, PPE must be used correctly - for example, putting it on and removing it correctly and safely. This relies on individual compliance, which is considered less reliable as a way of reducing risk.

See more information in the hierarchy of control chapter of the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) guidance PPE at work regulations from 6 April 2022.

Reducing the hazard

Public health measures such as vaccination, testing and isolation help to reduce the risk of infection. Vaccination against respiratory illnesses such as flu and COVID-19 is an important measure in reducing the risk of severe disease. Measures such as not coming to work when ill, advising people to isolate while infectious and recognising and reporting infections promptly, all help to prevent infections spreading at work.

Changing what we do

When faced with a particular risk, such as an outbreak, we may need to change what we do. This might include reducing communal activities, limiting visiting, or adding disinfection into a more frequent cleaning schedule, for example.

Changing where we work

We may not be able to change where we work but the work environment can be made as safe as possible. For example, by improving ventilation, ensuring fixtures and fittings are in good repair and can be easily cleaned and following water safety guidelines, we reduce opportunities for pathogens to survive in the environment.

Changing how we work

Changing the way we organise work can reduce risk. Examples include reducing the number of people in a space at any one time and minimising the movement of staff between different settings. Administrative controls such as risk assessments, training, audit, and providing clear signage and instructions also help to reduce the risk of infection at work.

Standard infection control precautions

To ensure safety, standard infection control precautions (SICPs) are to be used by all workers for all people whether infection is known to be present or not. SICPs are the basic IPC measures necessary to reduce the risk of spreading pathogens.

These basic IPC measures are:

- hand hygiene

- respiratory and cough hygiene

- PPE

- safe management of care equipment

- safe management of the environment

- management of laundry

- management of blood and body fluid spills

- waste management

- management of exposure

Sources of infection include blood and other body fluids, secretions or excretions (excluding sweat), non-intact skin, or mucous membranes, and any equipment or items in the environment that could have become contaminated.

The application of SICPs is determined by assessing risk to and from people. This includes the task, level of interaction, and/or the anticipated level of exposure to blood and/or other body fluids.

Hand hygiene

Hand hygiene is a way of cleaning hands that reduces potential pathogens on the hands. To be successful, hand hygiene needs to be performed at the right time, with the right product, using the right technique and making it easy to perform.

The World Health Organization (WHO) describes ‘moments’ for workers to practice hand hygiene:

- before touching a person

- before a clean or aseptic procedure (where applicable)

- after exposure to blood or body fluid

- after touching a person or significant contact with their surroundings

See the WHO poster Your moments for hand hygiene, healthcare in a residential home (pdf, 781kb).

There are other situations where hand hygiene should be performed including:

- after removal of PPE

- after using the toilet

- between different care activities with the same person (such as feeding them, assisting them with washing)

- after cleaning or handling waste

- before and after handling food

The hand hygiene product should be appropriate to the situation. Alcohol-based handrub should be used, except in the following circumstances when liquid soap and water must be used:

- hands are dirty, contaminated or soiled or may have come into contact with body fluids

- when caring for a person with diarrhoea and/or vomiting - pathogens that commonly cause such illnesses are not destroyed by alcohol (for example, Clostridioides difficile or norovirus)

Alcohol-based handrubs must have a minimum alcohol concentration of 60% and conform to the British Standard BS EN 1500:2013. Alcohol-based handrubs are harmful if swallowed and are flammable so their use must be risk assessed.

Alcohol-based handrubs should be applied using the correct technique which involves applying the solution, rubbing hands together vigorously ensuring solution contacts all surfaces of the hand until the solution has evaporated.

See the WHO poster How to handrub.

When washing hands, workers should:

- use liquid soap (bars of soap can harbour pathogens)

- use tepid running water

- dry hands with paper towels

- not use nailbrushes as they can damage the skin, creating an environment for pathogens to thrive

Hands should be washed using the correct technique:

- Wet hands using tepid running water (reduces skin irritation caused by soap).

- Apply liquid soap, rubbing hands together vigorously for 20 seconds ensuring soap contacts all surfaces of the hand and wrists.

- Handwashing should include the forearms if they have been accidentally exposed to body fluids and after skin-to-skin contact.

- Rinse thoroughly.

- Dry with paper towels (damp hands transmit pathogens more readily than dry hands).

See the WHO poster How to handwash.

An emollient hand cream should be applied regularly to protect skin from the drying effects of regular hand hygiene. Communal tubs of hand cream should not be used. If a particular soap or alcohol product causes skin irritation a clinician should be consulted.

Make hand hygiene safer and more effective when providing personal care:

- be ‘bare below the elbows’ when carrying out personal care. This means:

- having short sleeves or sleeves securely rolled up above the elbow

- removing hand and wrist jewellery

- one plain metal ring may be worn - this should be moved slightly during hand washing to enable cleaning under the ring

- bangles worn for religious reasons should be secured higher up the arm to enable cleaning of the hands and wrists

- have clean, short, fingernails which are free from nail products including artificial nails

- cover cuts or abrasions with a waterproof dressing

- locate hand hygiene facilities as close to the point of delivery of care as possible or consider the use of personal alcohol-based handrubs

- if you cannot wash your hands properly, use alcohol-based handrub following handwashing

- where there is difficulty accessing running water for handwashing, use hand wipes followed by an alcohol-based handrub. However, there is limited evidence for this and hand washing with soap and water should be performed at the first available opportunity

Respiratory and cough hygiene

Good respiratory hygiene reduces the transmission of respiratory infections. Being alert to people with respiratory symptoms is important as this may indicate infection.

To help reduce the spread of infection:

- cover the nose and mouth with a disposable tissue when sneezing, coughing, wiping and blowing the nose - if unavailable use the crook of the arm to catch a sneeze or a cough

- ensure a supply of tissues is in reach of the person or those providing care

- dispose of all used tissues promptly into a waste bin, which should be provided

- clean hands after coughing, sneezing, using tissues, or after contact with respiratory secretions or objects contaminated by these secretions

- keep contaminated hands away from the eyes, nose and mouth

- support people who need help with respiratory hygiene where necessary

Personal protective equipment

Assess the use of PPE considering the likelihood of exposure to blood, body fluids, secretions or excretions, risks associated with the procedure and risk of transmission of pathogens to the worker.

PPE should always be used when assessed as necessary to reduce the risk of transmission of pathogens and other risks associated with care tasks. PPE is the last element of the hierarchy of controls and used only when all other controls are considered insufficient to manage the risk of infection.

If it is not removed at the right time PPE can spread infection between people and wearing unnecessary PPE impacts on worker comfort, increases costs, and has adverse environmental impacts. The use of PPE should therefore be based on a risk assessment approach. When unsure what PPE is suitable in certain situations, advice can be sought from regional IPC teams.

Store PPE close to the point of use, if possible, and in a clean, dry and covered container or dispenser. When determining where to store PPE, take into account practicality and ease of use, as well as the safety of the people you are caring for. This may include storing PPE in lidded containers or dispensers. PPE should never be stored on the floor. For workers supporting people in their own home, arrangements may include storing in a dry, clean area protected from dust - for example, in sealed containers in the person’s home (with their permission and if safe to do so) or in sealed containers in the worker’s vehicle.

PPE is single use unless identified as reusable by the manufacturer, in which case it is important the instructions for decontamination are understood and followed.

Perform hand hygiene before putting on and after taking off PPE.

Change PPE if damaged or contaminated following the correct order for putting on and taking off (donning and doffing). All used PPE must be appropriately disposed of following local procedures for disposal of infectious waste.

See the quick guide for putting on and taking off standard PPE.

Gloves

In assessing the need for gloves and the selecting the type of glove, consider the risks to the person and the worker. For example, polythene gloves should not be used for personal care or where there is a risk of exposure to body fluids.

The assessment should include:

- who is at risk, and whether sterile or non-sterile gloves are required

- what the risk is - that is, the potential for exposure to blood, body fluids, secretions or excretions

- where the risk is - that is, contact with non-intact skin or mucous membranes during general care and any invasive procedures

Gloves are not an alternative to hand hygiene and should generally not be worn except when a specific care task requires them.

Wear gloves for care tasks involving contact with non-intact skin, or mucous membranes, and all activities where exposure to blood, body fluids secretions or excretions is anticipated - such as dressing wounds or carrying out personal care. Gloves should be worn when applying topical creams or medications which might be absorbed into the skin of the care worker applying them.

Gloves should also be worn when handling chemicals as recommended by a control of substances hazardous to health (COSHH) assessment, for example when handling cleaning products which may cause irritation. See HSE advice on carrying out COSHH assessments.

An aseptic procedure is a technique to prevent the transfer of pathogens from a contaminated area into a sterile area in the body. Wear sterile gloves for aseptic procedures and when inserting invasive devices such as urinary catheters.

Ensure gloves used for direct care are single use, fit for purpose and well fitting. Put them on immediately before the care activity, and change gloves between different care activities for the same person (for example, between continence care and oral care).

Dispose of gloves following infectious waste policy after and between caring for different people and between different care activities for the same person - for example, after helping a person to use the toilet and before helping a person to brush their teeth, and before contact with other items such as door handles. This will prevent the spread of pathogens within the environment. Do not decontaminate and reuse gloves.

Perform hand hygiene following removal of gloves, as the integrity of gloves is not guaranteed, and hands may become contaminated during their removal.

The table below provides advice on when different types of gloves could be used. There is also advice from HSE on what to consider when choosing gloves.

Table 2: glove use

| Type of glove | Care tasks |

|---|---|

| No gloves | Social contact, or physical contact where there is no risk of exposure to blood or bodily fluids and no contact with non-intact skin or mucous membranes. Domestic duties where no risk of exposure to hazardous chemicals. |

| Vinyl gloves | Offer sufficient protection for most duties in the care environment. If there is a risk of gloves tearing, or the task requires a high level of dexterity, or an extended period of wear, then an alternative better fitting glove (for example, nitrile) should be considered. |

| Nitrile gloves | Tasks where gloves will be worn for an extended period of time or high levels of manual dexterity are required. |

| Sterile gloves | Not routinely required in care settings. Should be used for aseptic procedures such as insertion of catheters. |

| Latex gloves | Equivalent to nitrile gloves for protection and dexterity but not routinely recommended due to risk of latex allergies or sensitivities. |

Latex gloves are not routinely recommended due to the risk of latex allergies or sensitivities among the workforce and people receiving care. Where providers wish to use latex gloves, they should ensure they are low protein and powder free and follow the HSE advice on selecting latex gloves.

Aprons

Wear plastic disposable aprons when there is a risk that clothing may be exposed to blood, body fluids, secretions or excretions. This could include activities such as personal care or handling dirty laundry.

Use plastic disposable aprons for one procedure or one episode of care. Gowns should be worn where there is a risk of extensive splashing of body fluids and aprons would provide insufficient cover.

Dispose of aprons when contaminated, after the completion of the care activity and between care of different people.

Face masks

Type IIR fluid-repellent surgical masks protect the wearer by providing a fluid repellent barrier between the wearer and the environment. They provide additional protection from respiratory droplets.

Consider wearing fluid-repellent type IIR masks where there is a risk of splashing of blood or body fluids into the worker’s nose or mouth. These should be well-fitting and cover the nose, mouth and chin and should not be touched when worn. Type IIR masks should be worn when carrying out aerosol-generating procedures (AGPs).

Fluid-resistant type IIR masks should not be worn for longer than 4 hours. They must be disposed of after the episode of care is completed, when damaged or when the mask becomes moist. Care workers should move to a safe area to remove the mask.

For additional advice on the use of masks specific to acute respiratory infections, including COVID-19, see the acute respiratory infection guidance.

Respiratory protective equipment

Respiratory protective equipment (RPE) is a type of PPE designed to protect the wearer against airborne hazards. The most commonly used RPE in social care settings is the filtering facepiece class 3, also known as an FFP3.

RPE is not routinely necessary and is used in a limited number of situations where respiratory protection is needed. If someone receiving care has a pathogen which requires care workers to use RPE, their primary care provider should advise on this.

There are specific legal requirements when using RPE including fit testing and fit checking. The organisational responsibility for the risk assessment of care activity is covered by health and safety regulations. See HSE information on the legal requirement of risk assessments.

RPE may be considered if there is a significant risk of exposure to infectious airborne particles that cannot be mitigated by the application of other control measures. All other control measures to reduce risk must be applied before considering RPE.

RPE may be recommended for use in social care settings when undertaking AGPs where there is a risk of infection or more broadly in response to a novel infection spread through the airborne route. A risk assessment in response to a novel airborne infection would need to consider:

- if workers will need to be in close contact with people who are infectious (for example, to carry out personal care)

- if the environment cannot be well ventilated

- whether use of FFP3s would be likely to reduce the risk of transmission

On its own, RPE will not provide total protection and should only be used when a risk assessment indicates this is an appropriate action for the care task, the client, the care worker and the environment. Not many people would willingly want to wear RPE for any length of time as it can be uncomfortable to wear. HSE provides further information as to why RPE is referred to as the last resort in terms of protection.

Additional guidance will be issued if a novel infection requires routine use of RPE, but care providers may wish to consider how they would react to this need, such as how they would arrange or access fit testing for workers.

See the HSE website for further information on respiratory protective equipment (RPE).

Eye protection

Consider wearing eye protection such as goggles or visors where there is a risk of blood or body fluids splashing into the worker’s eyes. Do not touch the eye protection when wearing. Decontaminate reusable eye protection in accordance with manufacturer’s instructions and store safely.

Regular spectacles do not provide sufficient protection. Visors may offer greater comfort for those who wear spectacles.

PPE recommendations summary

Table 3: the recommended PPE that should be used as standard precautions

| Activity | Face mask | Eye protection | Gloves | Apron |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Care or domestic task involving likely contact with blood or body fluids (giving personal care, handling soiled laundry, emptying a catheter or commode) | Risk assess if splashing likely Type IIR if splashing likely |

Risk assess if splashing likely | Yes | Yes |

| General cleaning with hazardous products (disinfectants or detergents) | Risk assess if splashing likely Type IIR if splashing likely |

Risk assess if splashing likely | Risk assess | Risk assess |

| Undertaking an AGP on a person who is not suspected or confirmed to have an infection spread by the airborne or droplet route | Yes - type IIR to be used for single task only | Yes | Yes | Yes (consider a gown if risk of extensive splashing) |

For people with an infectious illness, follow the above principles and any additional advice for the specific infection.

Safe management of care equipment

Pathogens may be transferred between people through the use of care equipment if it is not properly stored and cleaned, including consideration to how equipment is safely transported between people’s homes, so it does not become contaminated.

Reusable care equipment must be decontaminated after each use. It must be clear who is responsible for decontaminating the equipment, the frequency, and method of decontamination which conforms with the manufacturer’s instructions.

Poorly maintained equipment can also increase the risk of infection. Care equipment should be standardised wherever possible and be stored to ensure it does not become contaminated, including during transport between people’s homes. It is easier for staff to clean and safely use equipment they are familiar with.

There are 3 categories of decontamination processes:

- cleaning - a process that physically removes contamination but does not necessarily destroy pathogens

- disinfection - a process that reduces the number of viable pathogens, but which may not necessarily inactivate some pathogens such as certain viruses and bacterial spores

- sterilisation - a process used to make an object free from all viable pathogens including viruses and bacterial spores

The choice of decontamination process for reusable care equipment depends on the assessment of risk. Risks fall broadly into 3 categories: high, medium and low.

Table 4: risk level

| Level of risk | Description | Method | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Items that come into contact with intact skin. Items that do not come into contact with people. | Cleaning. Disinfection if an increased infection risk is suspected. | |

| Medium | Items that come into contact with intact mucous membranes or items contaminated with particularly virulent or readily transmissible pathogens. Items used with people who are immunocompromised. Low risk items contaminated with blood or body fluids. | Cleaning (followed by disinfection or sterilisation if being used for more than one client). | Respiratory equipment, thermometer, commodes, urinals, bedpans. |

| High | All reusable medical devices that are used in close contact with a break in the skin or mucous membranes, and devices that enter a sterile area of the body. | Follow manufacturer’s instructions. This may include chemical disinfectant methods or sterilisation through an authorised sterilisation centre. | Wound dressing - sterile and single use. |

Single-use items

Symbol depicting the number 2 in a circle with a line through it. This indicates that an item with this symbol should only be used once.

A device designated as single use should not be re-used as this can affect safety, performance and effectiveness, exposing people to unnecessary risk. Anyone reprocessing or reusing devices designated as single use bears the full responsibility for its safety and effectiveness.

A single-use device should only be used on an individual person during a single procedure, and then safely disposed of. It is not intended to be used again, even on the same person.

Single person use items

These items are intended to be used by only one person for a limited number of uses. They must not be used by different individuals. Follow the manufacturer’s instructions regarding re-use and decontamination.

Cleaning of the environment

It is important those carrying out cleaning duties understand their responsibilities as required under the Health and Safety at Work etc Act 1974 and associated regulations including COSHH. Workers should be provided with the PPE required to safely undertake cleaning tasks. See HSE advice on carrying out COSHH assessments.

Where cleaning is the responsibility of the worker it is important all understand their responsibilities such as:

- whose responsibility it is for cleaning different areas of the environment

- the frequency of cleaning the different areas of the environment

- the method of cleaning, including the products to use

- the method, frequency and responsibility for cleaning equipment which includes reference to the manufacturer’s guidance for cleaning

- the training required for cleaning

- how cleaning standards will be monitored

- arrangements for cleaning outside of usual frequencies

- arrangements to prevent cross contamination - for example colour coding of cleaning materials

- how to safely dispose of items such as cleaning cloths and gloves

For further advice on cleanliness in all healthcare settings including care homes, see NHS England’s National standards of healthcare cleanliness 2021.

Ventilation

Ventilation is an effective measure to reduce the risk of some respiratory infections, by diluting and dispersing the pathogens which cause them. Open windows and vents more than usual - even opening a small amount can be beneficial.

Opening high level windows is preferable to low level windows where there is a danger of creating draughts and causing discomfort. Where the room has multiple windows, it is usually possible to create a more comfortable environment by opening all windows a small amount rather than just one a large amount.

Opening windows on different sides of a room will allow greater airflow. Where possible, opening external doors can improve ventilation. However, this may present security and safety issues, so would need proper consideration and risk assessment.

In care establishments, removing window restrictors is not advised due to safety and security issues. Keeping internal doors open may increase air movement and ventilation rate. However, it is important that fire doors are not kept open, unless fitted with approved automatic closers. Internal doors should be kept closed if a client is being cared for in isolation where there is a risk of infection to others.

Refurbishment

Where refurbishment or new builds of care with accommodation services are planned, the risk of infection should be considered in the design, alongside creating a homely environment. Considerations should include:

- sufficient and appropriate storage to protect equipment from damage and contamination

- quality finishes which can be readily cleaned and are resilient

- flooring that is slip resistant and easily cleaned

- surfaces that are easily accessed, not affected by detergents and disinfectants, and will dry quickly

- sufficient provision of hand hygiene facilities

- sufficient ventilation and heating

- sufficient space to:

- store waste

- process and store linen

- store cleaning equipment hygienically

- sufficient toilets, bathrooms, en-suites, sluice rooms and clean utility rooms

Management of laundry

People are supported in a variety of different environments, and workers have differing degrees of control and responsibility for the management of laundry depending on the setting.

It is important to ensure workers have the required information in relation to laundry management that is appropriate to the setting within which they are supporting people.

The key principles for safely handling laundry are:

- wash hands between handling clean and used or infectious laundry

- prevent cross contamination between clean and used or infectious laundry

- use separate containers for clean and used or infectious laundry

- do not shake used or infectious laundry

- do not place used or infectious laundry on the floor or on surfaces

- use an apron to protect worker clothing from used or infectious laundry

- infectious laundry:

- do not wash by hand

- use the appropriate pre-wash cycle

- launder separately from other items

- launder at appropriate temperatures

There are 3 categories of laundry:

- clean - laundry that has been washed and is ready for use

- used - used laundry not contaminated by blood or body fluids

- infectious - laundry used by a person known or suspected to be infectious and/or linen that is contaminated with blood or body fluids, for example faeces

Clean

Store clean linen in a clean, designated area, preferably an enclosed cupboard.

Used

All dirty linen should be handled with care, and attention paid to the potential spread of infection. Within a care home, place used laundry in an impermeable bag immediately on removal from the bed, or before leaving the person’s room. Place the laundry receptacle as close as possible to the point of use, for immediate laundry deposit.

Handle used laundry safely by wearing a single use or washable apron to protect your clothing if necessary. Avoid:

- shaking or sorting laundry on removal from beds

- placing used laundry on the floor or any other surfaces

- re-handling used laundry once bagged

- overfilling laundry receptacles (not more than two-thirds full)

- placing inappropriate items in the laundry receptacle

Infectious

Infectious laundry includes laundry that has been used by someone who is known or suspected to be infectious and/or linen that is contaminated with body fluids.

Seal infectious laundry in a water-soluble bag (appropriate for the washing machine used) immediately on removal from the bed, and then place this within an impermeable bag.

Place water-soluble bags containing infectious laundry directly into the washing machine without opening the bags.

Use separate containers for transporting clean laundry, and used or infectious laundry, and wash infectious laundry separately.

Clean hands between handling different categories of laundry.

Where workers are responsible for laundering the clothing of a person with an infectious illness, these should be laundered at the highest temperature possible recommended by the manufacturer. For delicate items of infectious laundry consider using a laundry bleach or alternative laundry disinfectant. Heavily soiled items should have a pre-wash cycle or sluice cycle selected where available.

Within care homes, consider processes that will help ensure dirty laundry will not contaminate clean laundry. Consider having a dirty to clean flow system in laundry rooms so clean and used laundry are physically separated and ensure hand washing facilities are available where possible to do so.

Management of blood and body fluid spills

A spillage is an accidental escape of substances into the environment. Blood and body fluids may contain a high number of pathogens.

In the event of a spillage of body fluids, keep people away from the area until removed.

Spillages of blood and other body fluids may spread infection and must be cleaned immediately.

Consideration as to what is being cleaned will guide the choice of product and approach to cleaning. Chlorine releasing agents must not be used directly on a urine spill.

Use and store products safely following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Waste management

Waste management is important to ensure waste does not pose a risk of injury or infection. In addition to safe working practices, appropriate management of waste has additional benefits in terms of cost and lessening the environmental impact of waste.

People are supported in a variety of different environments and workers have differing degrees of control and responsibility for the management of waste. All workers responsible for management of waste should understand how to segregate and store waste before collection or disposal according to the hazard.

There are several types of waste including recycling, household, offensive or hygiene, infectious, sharps and medicines. Where any doubt exists as to the classification of waste, the local authority or the Environment Agency should be consulted.

An assessment of how waste will be disposed of will include:

- who generates, and where the waste is generated

- whether the waste contains blood or body fluids from a person with a known or suspected infection

- whether the waste is assessed as non-infectious but has the potential to offend those who come into contact with it

NHS England’s Health Technical Memorandum (HTM) 07-01 is a useful guide to assist with waste management.

Principles of waste management:

- systems should be in place to ensure that waste is managed in a safe manner and expensive (infectious) waste streams used only where indicated

- all outer packaging should be removed and recycled, where possible

- waste involving sharps such as needles should always be disposed of in a sharps box designed for this purpose

- waste should be placed in an appropriate waste bag, no more than three-quarters full and tied. Sharp items should not be disposed of into waste bags

- hands should be cleaned after handling waste

- waste bins should be foot operated, lidded and lined with a disposable plastic waste bag

- collection of waste from care services should be arranged through a licensed waste contractor

In care homes typically, waste bags are colour coded:

- black - general or household waste

- yellow with black stripe - offensive waste

- orange - infectious waste

- yellow - infectious waste contaminated with medicines and/or chemicals

However, waste contractors may operate a different colour coding system.

Management of exposure (including sharps injuries)

There should be a plan to minimise the risk of exposure to potential pathogens. Examples of exposure include sharps injuries, human bites, failures in PPE, splashing of blood or body fluids into eyes. Where sharps are used a risk assessment should be carried out, and a safe system of work developed. Sharps should not be passed directly from hand to hand.

Needles must not be bent, broken, dissembled or recapped, and should be disposed of by the person generating the sharps waste into a sharps container.

Sharps containers must be located in a safe position which reduces the risk of spillage. Containers should be taken to the point of use, and the temporary closing mechanism used when not in use.

Only sharps waste should be disposed of in a sharps container, and it must not be filled above the fill line.

If an incident occurs, such as a staff member is injured by a sharp object, or there is a risk of contamination, medical attention should be sought without delay, and there should be an immediate assessment of any exposure. Immediate actions should be taken to reduce risks, including reporting the incident to an appropriate person.

Investigation to understand the circumstances of the incident should be undertaken and any identified actions to prevent similar incidents should be taken. Sharps handling should be eliminated or reduced, and approved safety devices used where appropriate.

For more information on the management of exposure, see:

-

HSE guidance on how to deal with an exposure incident

-

NHS England’s National infection prevention and control manual (NIPCM) - and specifically the NIPCM appendices page for ‘Appendix 10: best practice - management of occupational exposure incidents’

2. General information

Vaccination

Vaccination is an important component of good IPC. Vaccinations protect people against vaccine preventable infectious diseases, including respiratory diseases. Staying up to date with recommended vaccinations including booster and seasonal doses, helps reduce risk from these infections.

People working in adult social care, and people receiving care, are encouraged to make sure they receive the vaccinations they are eligible for. Providers should undertake risk assessments to ensure the safety of people who receive care and workers wherever possible

The Green Book has the latest information on vaccines and vaccination procedures for vaccine preventable infectious diseases in the UK.

Antimicrobial resistance

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a global problem that impacts all countries and people.

AMR arises when pathogens evolve to survive treatment. Once standard treatments are ineffective, it is easier for infections to persist and spread. The UK’s ambition is to reduce the burden of treatment resistant infections, and improve the use of antibiotics.

Taking antibiotics when you do not need them means they are less likely to work in the future. Not all infections need antibiotics and many mild bacterial infections get better on their own. Antibiotics do not work for viral infections such as colds and flu, and most coughs and sore throats.

When there are indications a person may need antibiotics, the following should be considered:

- provision of accurate information to prescribers, such as symptoms, temperature, and any difficulties with swallowing

- understanding the risks and benefits of antibiotics

- understanding changes in prescribing practices may mean antibiotics may not be prescribed as they were previously

If antibiotics are prescribed:

- use antibiotics as directed - if directions are not precise, refer to the prescriber to clarify

- some foods and other medications (such as milk and antacids) hamper absorption of some antibiotics, so it is important to check the instructions to avoid this

- store antibiotics appropriately - some require refrigeration and can have short expiry dates

- ensure the course of antibiotics is completed, even if the person is feeling better before the course ends

- if liquid antibiotics are prescribed, use a medical measuring spoon or oral syringe to ensure accurate dosing

- many antibiotics cause mild, time-limited side effects such as abdominal discomfort and occasional diarrhoea, which resolve without intervention. However, some people develop allergies requiring medical intervention

Invasive devices and wounds

People with non-intact skin or an invasive device (such as urinary catheter, vascular access device or enteral feeding tube) are at increased risk of infection.

Evidence-based clinical guidelines for wound management and management of invasive devices should be followed. Specific training to ensure competency is needed for those supporting people with invasive devices or wounds.

People and their family members or carers (as appropriate) should be supported in understanding and applying safe management of invasive devices or equipment, including techniques to prevent infection where this is appropriate to do so.

Decisions should be reviewed regularly by a clinician. People with invasive devices or wounds should have a documented plan of care, providing detailed guidance as to the care and management and monitoring for infection.

Accurate and complete records should be kept regarding the care and maintenance of any device.

Manufacturers’ instructions for use, storage and changing intervals must be followed.

NICE guidance on Healthcare-associated infections: prevention and control in primary and community care provides further useful information on long-term urinary catheters, enteral feeding and vascular access devices.

Moving between settings

People have contact with multiple health and social care services. Appropriate provision of information regarding a person’s infections not only ensures they receive the appropriate care and support, but also assists others in their risk assessments to ensure that other people are protected from any risk of infection.

It is important that services and workers are aware of any infections the person has, and are aware of the signs of infection, particularly in older people - for example, fever, diarrhoea or vomiting, unexpected falls and confusion - so that the appropriate care and support can be provided and to ensure continuity of care.

Providing the information in advance of the person using a health and care service allows that service to risk assess and plan the person’s care.

It may be appropriate to delay a person attending a particular appointment if they pose a risk of spreading an infection. This decision should be made by the professional providing the service, who will also consider the urgency of the appointment and the needs of the person.

If a person is being admitted to a service it is important that their medicines, including any antibiotics, are transported with them.

3. Managing infection

Standard precautions alone may not be sufficient to prevent the spread of infection. There is a need to assess any additional measures needed when a person is suspected or known to have an infection. Additional precautions are based on:

- which pathogen is causing the suspected or known infection or colonisation

- how the pathogen is spread

- the severity of the illness

- where the person is supported or cared for

- the procedure or task being undertaken

Identifying people who have an infection, and the pathogen causing it, is essential to ensure appropriate support is provided to minimise the risk of spreading it to others.

Be alert to people experiencing symptoms of infection, or exhibiting any changes in their usual behaviour. Be curious if more than one person is experiencing similar symptoms - this may indicate spread, even where the people have no obvious links. Consider who may need to know this information, for example the health protection team, primary care network, social care providers and local infection control team.

Reducing opportunities for infection to spread can be achieved by minimising contact with the person during their infectious period.

Workers who have a confirmed or suspected infection which can be spread to others should not work until they are no longer at risk of passing on infection to others. This will require an individual assessment of the pathogen causing the infection and the individual circumstances.

People should continue to be supported while infectious, but the arrangements for their care will be different. People may be encouraged to minimise contact with others or be isolated and staff may wear different PPE equipment.

Extra precautions are categorised according to the way the pathogen spreads, noting that some pathogens are spread by multiple routes. The 3 categories are:

- contact precautions - used to prevent and control infections that spread via direct contact with the person or indirectly from the person’s immediate environment (including care equipment). This is the most common route of cross-infection spread

- droplet precautions - used to prevent and control infections spread over short distances (at least 3 feet or 1 metre) via larger droplets from the respiratory tract of one individual directly into the eyes, nose, or mouth of another individual. Droplets enter the upper respiratory tract

- airborne precautions - used to prevent and control infections spread without necessarily having close contact with the person via aerosols (smaller than droplets) from the respiratory tract of one individual directly into the eyes, nose, or mouth of another individual. Aerosols enter the lower respiratory tract

These categories help identify the additional precautions which may include isolation and additional PPE depending on the pathogen.

Respiratory protective equipment

See the section on RPE above.

Isolation

The aim of isolation is to prevent spread of infection to others. How this aim is achieved will differ depending on the setting the person is in.

During their infectious period, the person should be encouraged to remain in one area, usually their bedroom to reduce the risk of spread to others in their household or care home. People can find it difficult to remain isolated. Where they have the desire and feel able, opportunities to access outside space should be provided. Consideration should be given to distancing measures and restricting mixing with people susceptible to infection, depending on the pathogen causing the infection.

Extra cleaning of isolation areas should be considered. Ideally this area will have its own toilet and washing facilities - where this is not possible, consider a routine for use and cleaning communal or shared facilities. Consideration should be given to any additional PPE.

Workers need to be aware of the person’s infection and how they should be supported. Workers should be aware of signs of infection in their clients, for example fever, diarrhoea or vomiting, and the more atypical signs in older people such as unexpected falls and confusion. Ensure people’s nutrition and hydration are maintained, and additional checks by staff may be required.

Arrangements should consider the additional time required to provide psychological support. The person should be involved in the decision regarding isolation, and a plan to address psychological isolation formulated. Consideration should be given to capacity and understanding of the need to isolate. People may become disorientated and anxious, and need reassurance and to be provided with information.

In residential settings, people should be supported to continue seeing their friends and family wherever possible. This could include enabling visits to take place within the person’s private room and providing visitors with information and support to comply with any additional IPC measures such as increased handwashing or the use of additional PPE.

Consideration should be given to having a smaller number of workers dedicated to supporting the person during their infectious period.

The decision to stop isolation should be assessed and decided based on individual factors. For example, those who are immunocompromised may shed pathogens for a longer period. Advice from clinicians or infection control teams should be sought as necessary.

Outbreaks (residential services)

It is important to recognise potential outbreaks promptly, and to implement control measures as soon as possible, to prevent further cases. An outbreak is defined as 2 or more linked cases of the same (confirmed or suspected) infection occurring around the same time and associated with the service or location.

It is important to identify people with signs and symptoms of illness even if they have not yet reported feeling unwell. This may include staff.

An outbreak management plan should be in place, detailing the actions that should be taken in the event of an outbreak.

Advice and support

Inform others of the outbreak or suspected outbreak and obtain any support and advice. This may include:

- UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) local health protection team

- infection control team

- local authority or commissioners

- integrated care system

- environmental health if suspected food related outbreaks

- people’s relatives and significant others

- hospital or outpatients if anyone in the home has an imminent appointment

- primary care network

- other care providers if a person is, has been, or will be, supported by others

Outbreak response

Once an outbreak has been identified, the care providers should review their outbreak plan to ensure the control measures are appropriate for the pathogen causing the outbreak, those at risk, and the management of the environment.

Workers must follow professional advice from health protection teams or infection control teams to control the outbreak and support those infected, ensuring any recommended specimens are collected as directed and without delay.

Workers should receive information regarding the outbreak, including signs and symptoms of infection, who is affected, and the necessary controls.

Increased monitoring of infection control practices should be implemented to ensure high standards of infection control practice are being maintained to bring the outbreak under control.

Enhanced monitoring of signs and symptoms of all people should be implemented to quickly identify potential spread. Any suspected or new cases should be encouraged to isolate for the duration of their infectious period and referred for clinical review as appropriate.

Workers should be alert to any deterioration in the person’s condition and refer for clinical advice as appropriate.

Workers should be excluded from work if experiencing signs or symptoms of infection. Staffing requirements should be reviewed including contingency planning.

Cleaning arrangements should be reviewed and amended as necessary, considering the efficacy of the products used and frequency. Waste management procedures should also be reviewed if larger quantities are expected to be generated.

Sufficient stocks of PPE, hand hygiene products, and paper products such as tissues and toilet tissue should be available and conveniently located.

Consider the use of shared areas, and whether distancing measures need to be increased.

Consider whether arrangements for visits in and out need to be modified following a risk assessment, and whether it is appropriate to admit new people to the service during the outbreak. Contact with relatives and friends is fundamental to care home residents’ health and wellbeing. The right to private and family life is a human right protected in law (Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights).

There should be a clear decision on when the outbreak is over and when additional infection control measures are no longer needed. Other professionals, such as health protection teams or outbreak management teams may be involved in this decision.

Consider reviewing the outbreak to identify areas of outbreak management which went well, what was challenging and what has been learnt to inform future practice. Review the outbreak management plan in light of this learning.

Taking specimens

Guidance on specimen collection, supplies of containers, and transport requirements should be obtained from the local laboratory supplying the diagnostic service. This should be done with consent of the person, and in line with relevant guidance.

All specimens should be safely contained in an approved leak proof container, which should be provided by the healthcare provider requesting the test. This should be enclosed in another container, commonly a sealable polythene bag. The request form should be placed in the side pocket of the polythene bag, and should not be secured with clips or staples as these may puncture the bag.

Care should be taken to ensure the outside of the container and the bag remains free from contamination with blood and other body fluids.

The request form should be completed fully along with the label on the specimen container. This includes the person’s identifier, date and time the sample was taken, the test required and relevant clinical details.

Specimens to be sent by post must be in an approved Post Office container surrounded by absorbent material. The specimen must be sent by first class post.

Specimens should be transported directly to the testing laboratory as soon as collected. Where this is not possible, appropriate arrangements for storage must be made to ensure the viability of the sample.

4. Leadership and governance

Creating a culture where everyone is empowered to speak up and be receptive to feedback about IPC behaviours has positive impacts on safety. Organisations with strong visible leadership, and exemplary role modelling from managers and team leaders, usually achieve excellence in IPC.

In regulated services, registered persons have legal obligations in relation to the prevention and control of infections as detailed in the Health and Social Care Act 2008 (Regulated Activities) Regulations 2014.

CQC must take the Health and Social Care Act 2008: code of practice on the prevention and control of infections into account when making regulatory decisions. By following the code, services will be able to show how they meet regulatory requirements for service providers and managers, as well as implementing best practice.

In each regulated care service there should be an identified lead with the knowledge and skills who takes responsibility for IPC.

Arrangements for IPC should include:

- assessment of the IPC measures needed

- how IPC policy, guidance and procedures will be reviewed and updated

- how workers will be supported to understand their responsibilities to reduce the risks of infection, and the frequency and content of training and education needed

- how the standards of IPC will be monitored to ensure the highest standards

- how episodes of infection will be reviewed, and learning disseminated

- the arrangements for cleaning and how these will be monitored

- how information regarding infection will be shared with other providers, when people move between services

- how people and those significant to them will be supported to understand IPC measures

- how IPC practices will be promoted

- how staff and people who access services will be supported with vaccination, in line with national guidance and local risk assessment

- provide suitable accurate information on infections to ensure people’s safety and reduce risk of spread

- the person responsible for developing IPC procedures should consider the relevant legislation applicable to the setting, for example Health and Safety at Work Act 1974, COSHH, Health and Social Care Act 2008 and the related regulations. They should also consider how they will ensure the implementation of IPC procedures complies with requirements in legislation such as the Mental Capacity Act 2005, the Equality Act 2010 and the Human Rights Act 1998

Annual statement for residential settings

An annual statement should be produced by registered services which includes:

- outbreaks of infection and actions taken

- audits and subsequent actions

- training and education received

- reviews and updates of policies, procedures and guidance

- risk assessments undertaken for prevention and control of infection

Promoting IPC

Promoting IPC is effective in supporting high standards in IPC. Several resources are nationally available to support promotion, such as the ‘Every Action Counts’ toolkit on Skills for Care Infection prevention and control page.

IPC champions have been advocates for promoting good infection control practices and driving local initiatives. Run by the Queen’s Nursing Institute, the network of champions scheme has been developed locally, nationally and within provider organisations.

Training and education

Training and education are essential to protect people from the risks of infection, along with maintaining competence in applying the principles of IPC. Each care service should have a policy which sets out the training required and the frequency, along with how ongoing competency will be assured.

Usual topics included in IPC training include:

- understanding how infections are spread and how to prevent it

- when and how to effectively perform hand hygiene

- how to risk assess and use PPE

- how to identify and respond to someone with a confirmed or suspected infection to prevent transmission

- how to respond to an outbreak of infection

- how to manage waste (including sharps) and laundry safely

- the importance of cleaning of equipment and maintaining the care environment

- prevention and management of exposure to infection (including sharps injury)

- specific training for those whose duties involved in supporting people with needs place them at high risk of infection - such as people with invasive devices (for example, urinary catheters and those with wounds)

A number of organisations provide support and advice for IPC training and education, both nationally and regionally. Commissioners and the local integrated care system will have details of local arrangements. Nationally, Skills for Care and the Social Care Institute for Excellence provide resources.

Uniforms and workwear

Social care is delivered in multiple different environments, including people’s own homes, and workwear should be appropriate to the relevant environment. All workwear and uniforms should be clean and appropriate for the role and environment.

When providing direct, hands-on care, workers should be ‘bare below the elbows’ (see earlier section on hand hygiene for details). Long hair should be tied up and off the collar. If wearing a head scarf, it should be unadorned and tied neatly. Lanyards and neckties should not be worn during personal care.

Workers should wear clean clothes at the start of each shift, and change immediately if clothes become visibly soiled or contaminated. To enable this, workers may wish to consider storing spare, clean clothing at their workplace or in their vehicle.

To avoid risk of injury, workers should not carry pens, scissors or other hard or sharp objects in the pockets.

All elements of the laundry process contribute to the removal of infectious agents from fabrics. The washing process includes use of detergent, agitation and rinsing.

Uniforms and workwear should be washed at the hottest temperature the fabric will tolerate. Heavily soiled items should be washed separately to eliminate the risk of cross contamination.

Visiting (residential services)

Contact with relatives and friends is fundamental to care home residents’ health and wellbeing and visiting should be supported. There should not normally be any restrictions to visits into a care home and visits out should also be encouraged as much as possible in line with resident’s preferences.

Even during outbreaks, as a minimum, one visitor at a time should always be able to visit each resident inside a care home. This number can be flexible in case the visitor requires accompaniment (for example if they require support, or for a parent accompanying a child).

See guidance on acute respiratory infection for further details on visiting arrangements during viral acute respiratory infection outbreaks, including COVID-19.

Appendix 1: further information

Hand hygiene

WHO, Hand hygiene

WHO, How to handrub

WHO, Your moments for hand hygiene, healthcare in a residential home (pdf, 781kb)

Personal protective equipment

HSE, Respiratory protective equipment (RPE)

Quick guide for putting on and taking off standard PPE

Safe management of care equipment

Single-use medical devices: implications and consequences of re-use

Cleaning and laundry

NHS England, HTM 01-04: decontamination of linen for health and social care

NHS England, National standards of healthcare cleanliness 2021

NICE, Helping to prevent infection: a quick guide for managers and staff in care homes

NICE, Healthcare-associated infections: prevention and control in primary and community care

HSE, COSHH essentials for service and retail publications, (including SR4 - manual cleaning and disinfecting surfaces)

Environment

NHS England, Health Building Note 00-09: infection control in the built environment

The Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers, Emerging from lockdown

NHS England, HTM 03-01: specialised ventilation for healthcare buildings

Royal Academy of Engineering, Infection resilient environments

NICE, Indoor air quality at home

WHO, Guidelines for indoor air quality: dampness and mould

WHO, Natural ventilation for infection control in healthcare settings

Ventilation: approved document F

British Occupational Hygiene Society (BOHS), Ventilation tool: breathe freely

HSE, Ventilation in the workplace

Waste management

NHS England, HTM 07-01: management and disposal of healthcare waste

Classify different types of waste: healthcare and related wastes

Management of exposure

HSE, Blood-borne viruses (BBV)

HSE, How to deal with an exposure incident

NHS England, National infection prevention and control manual (NIPCM) - and specifically the NIPCM appendices page for ‘Appendix 10: best practice - management of occupational exposure incidents’

Uniforms and workwear

NHS England, Uniforms and workwear: guidance for NHS employers

Vaccination

Immunisation against infectious disease: the Green Book

Immunisation of healthcare and laboratory staff: the Green Book, chapter 12

Antimicrobial management

UK 5-year action plan for antimicrobial resistance 2019 to 2024

UK 20-year vision for antimicrobial resistance

Leadership and governance

Health and Social Care Act 2008: code of practice on the prevention and control of infections

CQC, Guidance for providers on meeting the regulations

Promotion

Skills for Care, Infection prevention and control

Queen’s Nursing Institute, Network of champions

NICE, Helping to prevent infection: a quick guide for managers and staff in care homes

Training and education

Skills for Care, Care certificate

Social Care Institute for Excellence, Infection control e-learning course

High risk interventions

NICE, Healthcare-associated infections: prevention and control in primary and community care

Moving between settings

NICE, Moving between hospital and home, including care homes

Appendix 2: roles and responsibilities

Registered persons

Providers of health and care services providing regulated activities and registered with the CQC are required to comply with regulations associated with preventing and controlling the spread of infection and ensuring the cleanliness of premises and equipment where care is delivered.

The code of practice on the prevention and control of infections and related guidance provides a framework to assist registered providers develop and maintain high levels of infection prevention. The code supplements the legal requirements set out in regulation.

Local authority

The local authority must act jointly with the Secretary of State to appoint a director of public health who acts as an officer for the local authority. The local authority may also be required to exercise any of the public health functions of the Secretary of State, should regulations be imposed.

The local authority must take such steps it considers appropriate for improving the health of people in its area. These steps may include providing services or facilities of the prevention, diagnosis or treatment of illness. Commissioning organisations may wish to assure themselves that the services they commission meet the expected standards of IPC.

Director of Public Health (local authority)

The Director of Public Health is accountable for the delivery of their local authority’s public health duties, and is a statutory chief officer of their authority. The role is wide ranging, and has both statutory and non-statutory responsibilities.

The Director of Public Health provides advice and expertise to the local authority and public on a range of health issues, from outbreaks of disease and emergency preparedness through to improving the health of local populations.

UK Health Security Agency

UKHSA is responsible for protecting every member of every community from the impact of infectious disease, and providing intellectual, scientific and operational leadership at national and local level, as well as on the global stage, to make the nation’s health secure. Local health protection teams provide specialist public health advice and operational support.

Department of Health and Social Care

There is a provision contained in the Health and Social Care Act 2008 for the Secretary of State to issue and keep under review a code of practice relating to the prevention and control of infections. The Secretary of State must, by regulations, impose requirements which they consider necessary to ensure registered care providers cause no avoidable harm to persons for whom the services are provided.

The Secretary of State must act jointly with each local authority to appoint a director of public health.

Care Quality Commission

CQC’s statutory objective is to protect and promote the health, safety and welfare of people who use health and social care services. In performing its functions, the commission must have regard to such aspects of government policy as the Secretary of State may direct.

CQC must have regard to any code of practice relating to health care associated infections when making decisions. In registering a service provider to carry out regulated activities, CQC must be satisfied that the provider can comply with the requirements of the regulations. Once registered, service providers are required to comply with the regulations. See the Health and Social Care Act 2008: code of practice on the prevention and control of infections.

The regulations require service providers to assess the risk of, and prevent, detect and control the spread of infection. They further require any equipment and premises be kept clean, and that cleaning be done in line with current legislation and guidance.

Appendix 3: common types of body fluid

High-risk body fluids are:

- blood

- cerebrospinal fluid

- peritoneal fluid

- pleural fluid

- synovial fluid

- amniotic fluid

- semen

- vaginal secretions

- breast milk

- wound exudate

- any other body fluid with visible blood

Other body fluids are:

- urine

- faeces

- saliva

- sputum

- vomit

If visible blood is present, treat as high risk.

Appendix 4: glossary of terms

Antimicrobial: a drug that selectively destroys or inhibits the growth of microorganisms. Sometimes referred to as an ‘antimicrobial agent’. Examples include antibiotics (also known as antibacterials) antiviral and antifungal agents.

Antibiotic resistant bacteria: bacteria with the ability to resist the effects of an antibiotic to which they were once sensitive.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR): occurs when the microorganisms that cause disease (including bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites) cease to be affected by the drugs we use to kill them and treat the disease.

Cleaning: a process that physically removes contamination but does not necessarily destroy microorganisms.

Decontamination: a process which removes or destroys contamination and thereby prevents microorganisms or other contaminants reaching a susceptible site in sufficient quantities to initiate infection or any other harmful response. Three processes of decontamination are commonly used: cleaning, disinfection and sterilisation.

Disinfection: a process used to reduce the number of viable microorganisms, but which may not necessarily inactivate some bacterial agents, such as certain viruses and bacterial spores.

Alcohol-based handrub: a preparation applied to the hands to reduce the number of viable microorganisms. This guideline refers to handrubs compliant with British standards (BS EN1500: standard for efficacy of hygienic handrubs using a reference of 60% isopropyl alcohol).

Impermeable bag: bags that a liquid does not leak or pass through at any time during their use or during the washing process.

Pathogen or pathogenic: an infectious agent (bug or germ), a microorganism such as a virus, bacterium, or fungus that causes disease in its host.

Personal protective equipment (PPE): equipment that is intended to be worn or held by a person to protect them from risks to their health and safety while at work. Examples include gloves, aprons and eye and face protection.

Reuse: another episode of use, or repeated episodes of use, of a medical device, which has undergone some form of reprocessing between each episode.

Single use: a medical device intended to be used on an individual person during a single procedure, and then discarded. It is not intended to be reprocessed and used on another person.

Standard infection control precautions (SICPs): the basic infection prevention and control measures necessary to reduce the risk of transmitting infectious agents from both recognised and unrecognised sources of infection.

Sterilisation: a process used to make an object free from all viable microorganisms including viruses and bacterial spores.

Water-soluble bags (sometimes referred to as ‘alginate’ bags) are:

- bags that dissolve or break apart when processed in a washing machine

- impermeable bags with a water-soluble seam