HPR volume 11 issue 43: news (1 December)

Updated 15 December 2017

Infections among people who inject drugs in the UK: annual report in summary

Shooting Up, the annual report on infections among people who inject drugs (PWID) in the United Kingdom, has been published by Public Health England [1]. The report was produced jointly by PHE, Health Protection Scotland, Public Health Wales, and Public Health Agency Northern Ireland.

PWID are vulnerable to a wide range of infections – including those caused by viruses such as HIV and hepatitis B and C, and bacteria such as Clostridium botulinum and Staphylococcus aureus – which can result in high levels of illness and death. The report examines the extent of infections and the associated risks among people who inject psychoactive drugs, such as heroin and cocaine.

Hepatitis C prevalence remains high and half of those infected are undiagnosed

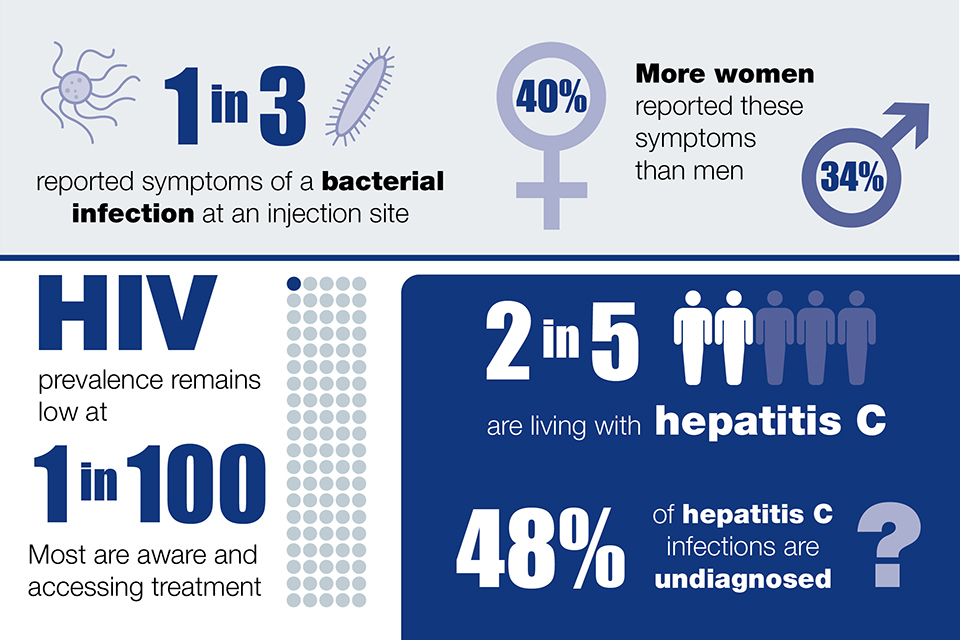

Hepatitis C remains the most common blood-borne infection among PWID, and there are significant levels of transmission among this group in the UK. Two in every five PWID are living with hepatitis C. The increasing availability of the new direct-acting antiviral drugs provides an opportunity to reduce morbidity and mortality from hepatitis C, and to decrease the risk of onward transmission. Improving the offer and uptake of testing for hepatitis C is particularly important as approximately half (48%) of hepatitis C infections among PWID remain undiagnosed. Of those who were unaware of their infection, 22% reported that they had never been tested, and of those unaware but tested, 44% reported that their last test had been more than two years earlier.

HIV levels remain low, but risks continue

In the UK, around one in every hundred PWID are living with HIV. Most have been diagnosed and will be accessing HIV care. However, HIV is often diagnosed at a late stage among PWID. Localised outbreaks of HIV continue to occur among PWID, as highlighted by the HIV outbreak in Glasgow that has been ongoing since 2015 (see following news report) and a cluster of HIV infections that occurred in South West England in 2016.

Hepatitis B remains rare, but vaccine uptake needs to be sustained, particularly in younger age groups

In the UK, around one in every two hundred PWID are currently infected with hepatitis B infection. About three-quarters of PWID report taking up the vaccine against hepatitis B, but this level is no longer increasing, and is particularly low in younger age groups (54%) and among those who recently began injecting (54%).

Bacterial infections continue to be a problem

Bacterial infections in PWID are often related to poor general hygiene and unsterile injection practices. Bacterial infections can result in severe morbidity in PWID, with severity compounded by delays in seeking healthcare in response to the initial symptoms. Around a third (36%) of PWID report that they had a symptom of an injecting site infection during the preceding year, which is an increase from 28% in 2011-2013. More women reported these symptoms than men. Outbreaks of infections due to bacteria, particularly Group A streptococci, are continuing to occur among PWID.

Infographic illustrating the extent of hepatitis C, HIV and bacterial infections among those who inject psychoactive drugs

Injecting risk behaviours have declined but remain a problem

The level of needle and syringe sharing among PWID has fallen across the UK, but sharing remains a problem, with over one in six reporting sharing of needles and syringes in the past month.

Changing patterns of psychoactive drug injection remain a concern

Heroin remains the most commonly injected drug in the UK. Injection of crack has increased in recent years in England and Wales, with 53% of those who had injected in the preceding four weeks reporting crack injection in 2016 as compared to 35% in 2006. In recent years there has been an increase in the number of “new psychoactive substances” (NPS) being used in the UK. Some NPS, typically short-acting stimulants, can be injected and this is a concern due to the observed higher occurrence of risky injecting practices in this group. There is evidence, however, that the injection of some NPS, such as mephedrone, has declined.

Provision of effective interventions needs to be maintained and optimised

The findings presented in the report indicate a need to maintain and improve services that aim to reduce injecting-related harms and to support those who want to stop injecting. A range of services, including locally appropriate provision of needle and syringe programmes, opioid substitution treatment, and other drug treatment, should be provided [2,3]. Vaccinations and diagnostic tests for infections need to be routinely and regularly offered to people who inject or have previously injected drugs [3]. Care pathways and treatments should be optimised for those diagnosed with blood-borne viruses and bacterial infections.

References

-

PHE, Health Protection Scotland, Public Health Wales and Public Health Agency Northern Ireland (November 2017). “Shooting Up: infections among people who inject drugs in the UK, 2016”.

-

NICE (2014). Needle and syringe programmes: providing people who inject drugs with injecting equipment Public Health Guidance, PH52.

-

DH (2016). Drug Misuse and Dependence: UK guidelines on clinical management.

World AIDS Day: HIV in Scotland

In 2016, 4,412 of the 91,987 people living with diagnosed HIV infection in the UK live in Scotland. New figures from the end of September 2017 from Health Protection Scotland show that there were 256 HIV diagnoses in Scotland in 2016 [1].

The UK is one of the first European countries to witness a decline in HIV in gay and bisexual men [2] with Scotland observing a reported 40% decline in this group – from 131 in 2015 to 80 new diagnoses in 2016 – which is likely to be due to increasing availability of PrEP in addition to HIV testing and treatment. In July 2017, PrEP became available through NHS prescription in Scotland and as of November 2017, several hundred individuals who are deemed to be at a high risk of HIV infection, according to eligibility criteria, are now receiving NHS funded PrEP [3].

Unprotected sex among gay and bisexual men is the main risk factor for HIV acquisition in Scotland. However since 2015, there has been an outbreak of HIV among people who inject drugs (PWID) observed in NHS Greater Glashow & Clyde [4]. This outbreak has led to an increase in public health initiatives which have included raising awareness of HIV in this specific risk group and offering an increase in the number of testing opportunities and support services to those who have been recently infected [4].

HIV testing remains central in Scotland’s response to the HIV epidemic. In 2016, 57 (39%) of those newly diagnosed were diagnosed at a late stage of infection – this number has remained steady since the initial decrease was observed in 2014.

According to 2016 estimates, approximately 700 people in Scotland remain undiagnosed and are living unaware of their HIV infection. In order to end the AIDS epidemic by 2030, UNAIDS created the 90:90:90 targets [5] which aim to have 90% of people living with an HIV infection diagnosed, 90% of those diagnosed receiving treatment and 90% of those receiving treatment virally suppressed by 2020. In Scotland, the first of these targets has not yet been reached though access to treatment and care for HIV infections is good, with 4,575 individuals reported to have attended specialist services for treatment and care between July 2016 and June 2017. Of those attending these services, 96% were receiving antiretroviral drugs and of these people, 96% showed evidence of being virally suppressed, surpassing the UNAIDS targets surrounding these measures.

The Scottish Government’s Sexual Health and Blood Borne Virus Framework [6] exists to support improvements in sexual health and wellbeing, whilst addressing the impact of blood borne viruses in Scotland. It aims to reduce the number of HIV transmissions occurring in Scotland through increased preventative measures, by reducing the number of people living with undiagnosed infection and through maintaining high quality services that provide treatment to those infected.

Note: Records from Health Protection Scotland are incorporated into data for the rest of the UK. These data are then de-duplicated, with diagnoses or deaths regarded as relating to the same individual being assigned to the earliest country or region. Therefore UK figures may differ from those presented by Scotland.

References

- World AIDS Day – HIV in Scotland (2017). Health Protection Scotland Weekly Report 51(47), 28 November 2017.

- PHE (15 November 2017). Towards elimination of HIV transmission, AIDS and HIV-related deaths in the UK: 2017 report.

- HIV Scotland website.

- NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde website.

- UNAIDS (2014). 90-90-90: an ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic.

- Sexual Health and Blood Borne Virus Framework 2015-2020.

Scarlet fever upsurge in England, 2014 to 2016

The impact of the current upsurge in scarlet fever in England – which has led to significant increases in outbreaks and hospitalisations – is the subject of a recent Lancet Infectious Diseases paper [1].

Based on an analysis of notifications of scarlet fever in England and Wales between 1911 and 2016, the report concludes that the recent upsurge was unprecedented in terms of the relative increase in incidence, being greater in scale than seen during the four-yearly epidemic cycles of peaks and troughs in incidence over the last century. Population rates of scarlet fever rose from 8.2 to 27.2 per 100,000 between 2013 and 2014, with further increases in each of the following two years, resulting in 19,206 cases notified in 2016. Although most cases of scarlet fever are not severe, the rates of hospital admission during 2014-2016 increased in line with the elevation in disease incidence. One in 40 notified cases in 2014 were identified as having been admitted to hospital for the management of scarlet fever or complications. The impact on public health was substantial, the paper concludes, particularly with regards to the management of outbreaks, seen primarily in schools (67%) and nurseries (31%).

The authors considered a number of possible explanations for the sudden escalation in scarlet fever. Although England was the first western hemisphere country to record such an upsurge, similar increases are being recorded in east Asia, with no detectable microbiological link to the UK situation. Whilst data from 2017 are suggesting a slight drop [2], disease incidence remains high and uncovering the cause(s) of the upsurge remains priority. In the meantime, the authors stress the importance of patients with scarlet fever being treated with antibiotics to lower the risk of complications and onward spread to others. Guidelines for PHE health protection teams on management and recording of outbreaks were updated in October 2017 [3].

References

- Lamagni T, Guy R, Chand M, Henderson KL, Chalker V, Lewis J, et al (2017). Resurgence of scarlet fever in England, 2014-16: a population-based surveillance study, Lancet Infect Dis online, 27 November.

- Group A streptococcal infections: third update on seasonal activity, 2016/17, HPR 11(18), 12 May 2017.

- PHE (2017). Guidelines for the public health management of scarlet fever outbreaks in schools, nurseries and other childcare settings (October).

Infection reports in this issue of HPR

The following infection reports are published in this issue of HPR.