HPR volume 10 issue 40: news (18 November)

Updated 16 December 2016

1. Impact of changing nature of injecting drug use on infections in the UK

The fourteenth annual report on infections among people who inject drugs (PWID) in the United Kingdom – Shooting Up – has been published by Public Health England [1].

PWID are vulnerable to a wide range of infections – including those caused by viruses such as HIV and hepatitis B and C, and bacteria such as Clostridium botulinum and Staphylococcus aureus – that can cause significant morbidity and mortality. The report examines the extent of infections and the associated risks among PWID under five headings.

1.1 HIV levels remain low, but risks continue

HIV infection among PWID remains uncommon compared with many other countries. Only 1% of those who inject psychoactive drugs have HIV, and the prevalence is similar among those injecting image and performance enhancing drugs. Most of those infected with HIV are aware of their infection and are accessing care. However, HIV is often diagnosed at a late stage among PWID.

HIV transmission continues among PWID in the UK, and both injecting and sexual risks remain common. Among those currently injecting psychoactive drugs 16% reported needle and syringe sharing in 2015. Though sharing is less common among those injecting image and performance enhancing drugs, 13% reported ever sharing a needle, syringe or vial of drugs. Of those with two or more sexual partners during the preceding year, only 22% of those injecting psychoactive drugs reported always using condoms, as did only 17% of those injecting image and performance enhancing drugs.

The recent outbreak of HIV among people injecting heroin in Glasgow is a concern, as is the emergence of injecting drug use around or during sex among some groups of HIV positive men who have sex with men.

1.2 Many hepatitis C infections remain undiagnosed

Hepatitis C remains a major problem among PWID in the UK, with half of those who inject psychoactive drugs having antibodies to hepatitis C. Data indicate that hepatitis C transmission is probably stable in this group and further effort is needed to reduce this. Although the uptake of diagnostic testing is high (86%), about half of the hepatitis C infections remain undiagnosed.

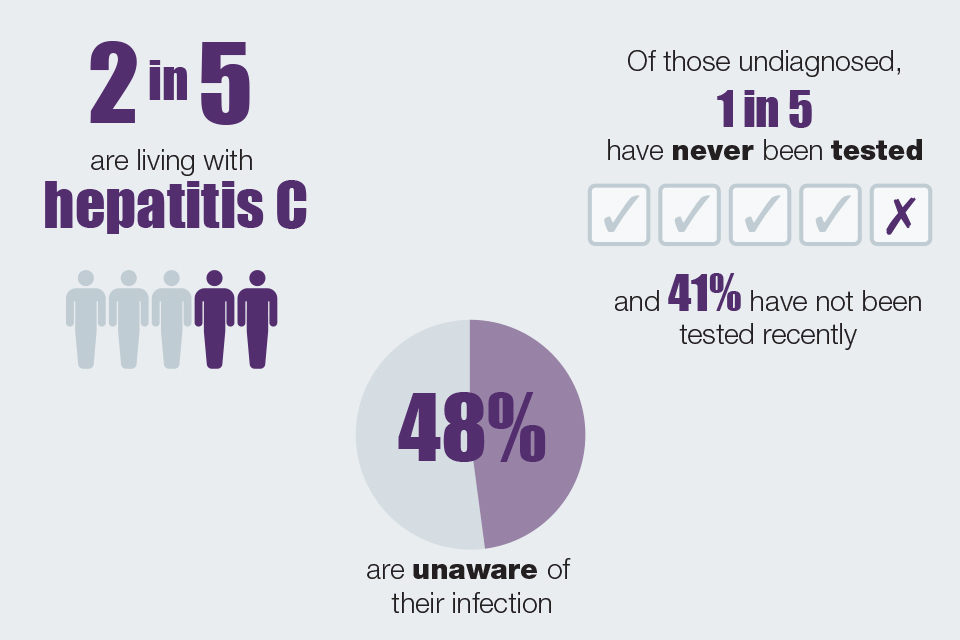

Key facts on the uptake of testing for hepatitis C are presented in an infographic associated with the new report (see extract below). Undiagnosed hepatitis C infection among PWID is either because people have never had a test (1 in 5) or have become infected since their last test (as 41% have not been tested recently). Those PWID with undiagnosed hepatitis C typically make use of a range of health services. This underlines the need to identify, and make use of, the opportunities for regularly offering tests to those at risk.

Infographic illustrating the extent of hepatitis C infections among those who injected psychoactive drugs like heroin and crack-cocaine in 2015

1.3 Hepatitis B remains rare, but vaccine uptake needs to be sustained

Less than 1% of those who inject psychoactive drugs are currently infected with hepatitis B. The proportion ever infected with hepatitis B has fallen from 26% in 2005 to 13% in 2015. This public health success reflects a marked increase in the uptake of the vaccine against hepatitis B during the 2000s. In 2015, 75% reported vaccination uptake, but this level is no longer increasing. Most of those who have not been vaccinated have been in contact with health services where they could have received a dose of the vaccine.

1.4 Bacterial infections continue to be a problem

A third (33%) of those who inject psychoactive drugs reported having a symptom of an injecting site infection during the preceding year. Outbreaks of infections due to bacteria, such as Clostridium botulinum, continue to occur in this group. Some of these infections are severe and place substantial demands on the healthcare system.

1.5 Changing patterns of psychoactive drug injection remain a concern

Heroin, alone or in combination with crack-cocaine, remains the most commonly injected psychoactive drug. However, there is evidence of an increase in the injection of stimulants, including recently emerged psychoactive drugs such as mephedrone. People injecting stimulants often report higher levels of risk behaviours.

1.6 Provision of effective interventions needs to be maintained

The findings presented in the report indicate a need to maintain, and improve services that aim to reduce injecting-related harms and to support those who want to stop injecting. A range of services, including locally appropriate provision of needle and syringe programmes, opioid substitution treatment, and other drug treatment, should be provided. Local areas need to be responsive to changes in drug use and the associated risks and offer these interventions in appropriate settings. Vaccination and diagnostic tests for infections need to be accessible, and routinely and regularly offered to people who inject or have previously injected drugs in line with guidance [2,3,4,5] to ensure sufficient coverage. Care pathways and treatments should be readily available to those testing positive

1.7 References

- PHE, Health Protection Scotland, Public Health Wales and Public Health Agency Northern Ireland (November 2016). “Shooting Up: infections among people who inject drugs in the UK, update November 2016”.

- Department of Health (2007). “Drug misuse and dependence – guidelines on clinical management: update 2007”.

- NICE (July 2007). Drug misuse: psychosocial interventions Clinical Guideline CG51.

- NICE (July 2007). Drug misuse: opioid detoxification Clinical Guideline CG52.

- NICE (March 2014). Needle and syringe programmes: providing people who inject drugs with injecting equipment Public Health Guidance, PH52.

2. Annual review of infections in UK blood, tissue and organ donors

PHE had published the NHSBT/PHE Epidemiology Unit’s annual review, Safe Supplies: A Picture for Policy, comprising a series of infographics to describe infections among blood, tissue, and organ donors during 2015, along with highlights on research and development activities [1]. Each infographic summarises information previously contained within individual chapters of the Annual Review report published in earlier years (blood, tissue, organs, research, etc). In each case, key findings relevant to policy decisions are emphasised. A set of data tables are published separately [1].

NHSBT/PHE Epidemiology Unit emphasises that donor selection policy ensures eligible donors are at low risk of infection and that routine donation testing mitigates most remaining risk. Blood donors are the biggest donor group: in 2015, 2.1 million whole blood and platelet donations were made by around one million donors in the UK. Routine screening for infectious disease markers found 198 positive (including one dual infection); this represents a low rate of detection – one in 10,000 donations – with markers of hepatitis B and syphilis the most common. Positive donations are removed from the blood supply. The overall rate of markers detected among blood donors has declined in recent years, and this trend continued in 2015.

The burden of infection remains disproportionately in new donors (one in 1,000), as testing donors for the first time identifies previously undiagnosed infections generally acquired a long time in the past. Very few recently-acquired infections were detected (26) suggesting donor selection remains effective at deferring most individuals with current high risk behaviour and as such the risk that a donation is made in the window period and not detected on testing is extremely low.

In 2015, the risk that testing would not detect an HBV, HCV or HIV window period infection was less than one per million donations tested; the highest risk was for HBV. Among the 19 recent infections detected in 2015 with a source of infection reported, 12 were through sex between men and women and six were through sex between men within 12 months and thus represents non-compliance with the MSM selection policy. MSM are disproportionately affected by HIV and syphilis.

The donor selection criteria concerning behaviours associated with increased risk of infection such as sex and injecting drug use are currently under review by the Advisory Committee on the Safety of Blood, Tissues and Organs (SaBTO) which advises UK ministers and health departments.

The number of living tissue donors is decreasing each year with falling demand for surgical bone. Among the 1,381 tested by NHSBT in 2015, five were positive for markers of infection, ie 3.6 per 1000 donors. Despite similarly stringent donor selection, this is approximately 3.5 times greater than the rate among new blood; reflecting the older age of surgical bone donors with higher rates of previously undiagnosed infections. In 2014 a new question was added to the Tissue Donor Health Check form to defer individuals with a past history of syphilis; while this significantly reduced the total number of donors found positive it has not eliminated it entirely and very low numbers of previously undiagnosed infections are detected. NHSBT also test deceased tissue donors who give bone, skin, heart valves, corneas and tendons, and donors are selected through a similarly stringent policy to other tissue donors. In 2015, among 2,917 donors tested, six were found positive for markers of infection, representing a rate of two per 1000 donors. Donations from tissue donors found positive are not used.

Donor selection policy also applies for deceased donors giving organs, but surgeons balance risk of using an organ from an infected donor against the risks for a patient who is waiting for a transplant. In 2015, there were 1879 potential organ donors who were consented for donation and tested; 1311 proceeded to donation, among whom 34 were positive for markers of HBV (HBsAg), HCV, HIV, HTLV and syphilis (18 per 1000 proceeding donors). Of those who proceeded to donation, 1237 became actual donors from whom 3422 organs were transplanted, including 10 who were positive for markers of HBV (HBsAg), HCV, HIV and syphilis (eight per 1000 actual donors), suggesting infection was not a barrier for transplant. The Unit is currently working to quantify the window period risk associated with transplantation.

In 2015, NHSBT tested 1,853 cord blood donors. One was positive for markers of HCV, one for syphilis and two for HTLV, representing a rate of 2.2 per 1000. Collection of cord blood by NHSBT is targeted at ethnically diverse populations in the London area to ensure a diverse supply of donations, accounting for the higher rates of infections detected. Positive donations are not used, and donors are referred for specialist advice, particularly on the risk of maternal HTLV transmission through breast feeding.

2.1 Reference

- PHE website (November 2016). Safe Supplies: annual review.

3. Gonococcal Resistance to Antimicrobials Surveillance Programme (GRASP) report 2016

PHE has published its annual Gonococcal Resistance to Antimicrobials Surveillance Programme (GRASP) report, presenting latest data from surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae [1].

Current first-line treatment for gonorrhoea involves dual therapy with ceftriaxone and azithromycin, but treatment effectiveness is threatened by antimicrobial resistance. Azithromycin resistance is of concern because GRASP sentinel surveillance indicates the prevalence of azithromycin resistance (minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) >0.5 mg/L) was approximately 10% in 2015, although 91% of these resistant isolates had MICs only just above the breakpoint for resistance. There were no ceftriaxone resistant isolates identified by the sentinel surveillance programme in 2015.

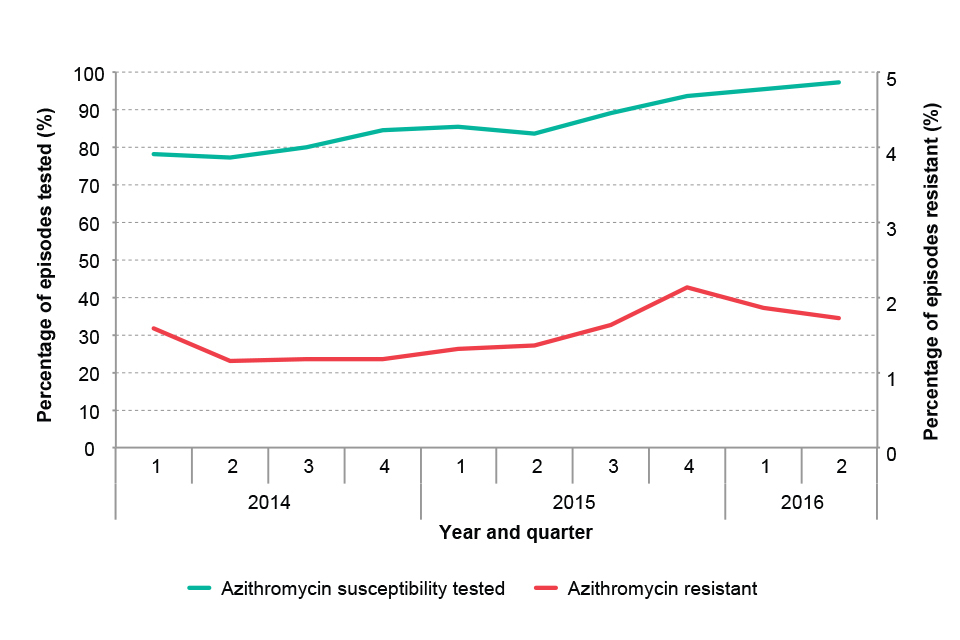

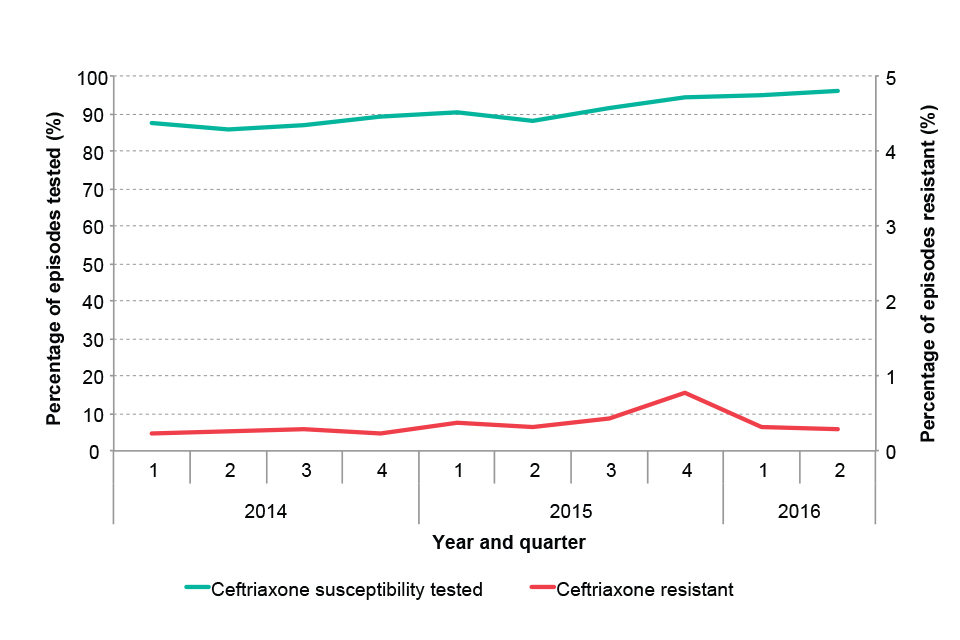

There has been an improvement in antimicrobial susceptibility testing of gonoccocal isolates within primary diagnostic laboratories. In 2016, isolates tested for azithromycin susceptibility increased to over 97% (figure 1). Isolates tested for susceptibility to ceftriaxone increased from 87% at the beginning of 2014 to 96% in the second quarter of 2016 (figure 2). However, the outbreak of high-level azithromycin-resistant N. gonorrhoeae (MICs ≥256 mg/L), first identified in Leeds in 2015, persists and in 2016 spread to other parts of England. Therefore, it is important that all primary diagnostic laboratories test gonococcal isolates for susceptibility to first-line antimicrobials and refer suspected azithromycin- and/or ceftriaxone-resistant isolates to the PHE reference laboratory for confirmation and follow-up.

Practitioners should ensure all patients with gonorrhoea are treated and managed according to national guidelines and be alert to changes in antimicrobials recommended for front-line use [2]. Sexual health services should report possible cases of treatment failure to PHE via the online HIV and STI web-portal (contact HIVSTI@phe.gov.uk for details.

Figure 1. Percentage of gonococcal isolates tested for azithromycin susceptibility and reported as resistant by primary diagnostic labs in England by quarter: 2014 to June 2016

Figure 2. Percentage of gonococcal isolates tested for ceftriaxone susceptibility and reported as resistant by primary diagnostic labs in England by quarter: 2014 to June 2016

3.1 References

- PHE (2016). “Surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria Gonorrhoeae. Key findings from the Gonococcal Resistance to Antimicrobials Surveillance Programme (GRASP). Data up to August 2016”.

- Bignell C, Fitzgerald M (2011). “UK national guideline for the management of gonorrhoea in adults, 2011”. Int J STD AIDS 22(10): 541-7.

4. Infection reports in this issue of HPR

The following bacteraemia report is published in this issue of HPR: