Health matters: antimicrobial resistance

Published 10 December 2015

Summary

Antibiotic consumption in England is on the rise and increased antibiotic prescribing is fuelling increased resistance in bacteria.

Public Health England (PHE) wants to see a reduction in the number of infections caused by antibiotic resistant bacteria.

This resource focuses on what we know works to help improve appropriate prescribing. It is aimed at those responsible for prescribing, local authorities and public health policymakers.

Keep up to date with Health matters

Sign up to the bulletin or read the Health Matters blog for regular updates.

For any questions on this resource, please email: healthmatters@phe.gov.uk

The scale of the problem

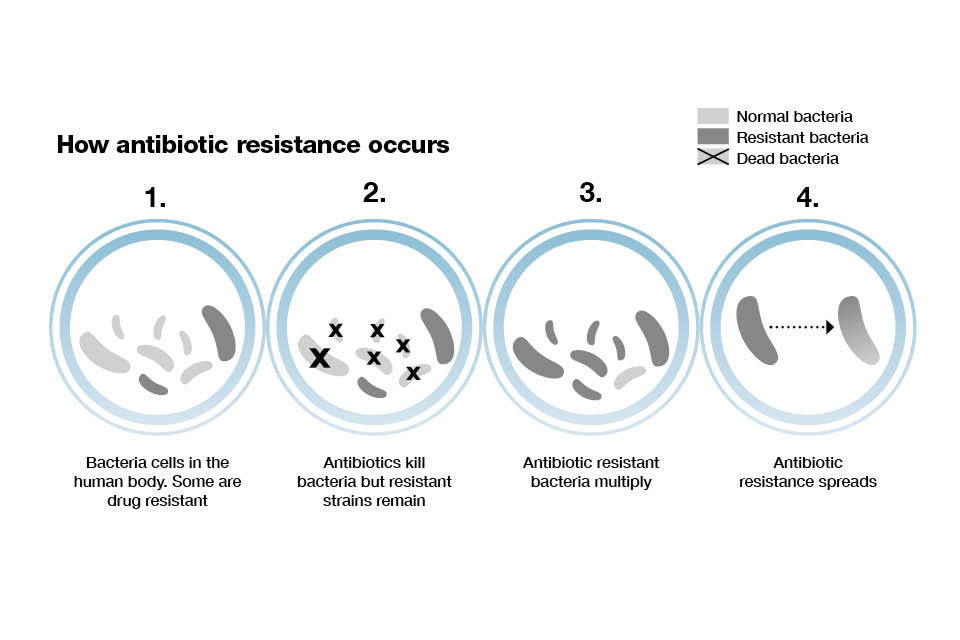

Antibiotics are unlike many other drugs used in medicine, as the more we use them the less effective they become against their target organisms. With antibiotics, overuse or inappropriate use allows bacteria to develop resistance.

Infographic showing how antibiotic resistance occurs.

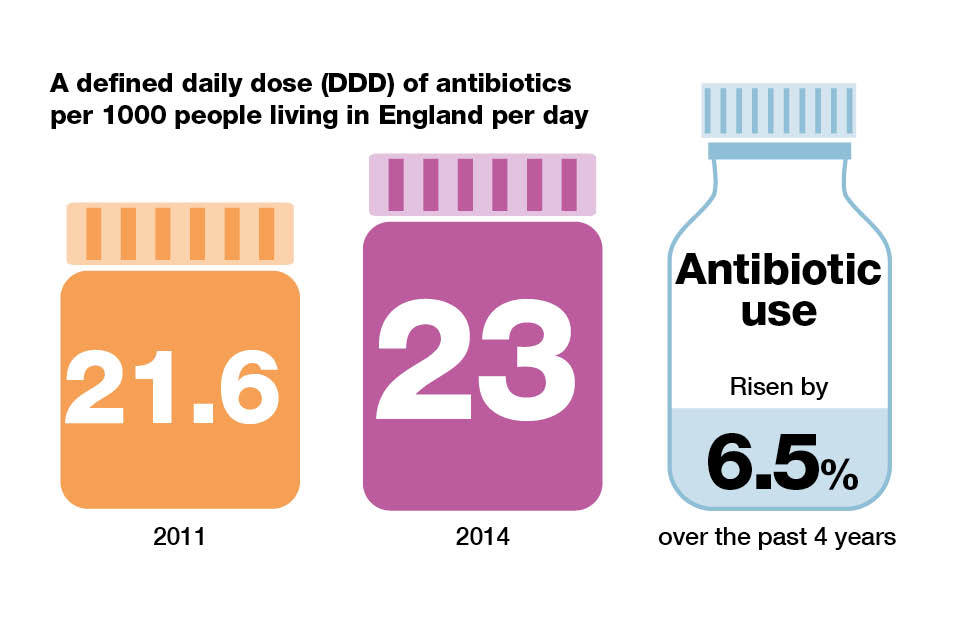

Antibiotic consumption increased by 6.5% over the past 4 years in England. Prescribing is measured as the defined daily dose (DDD) of antibiotics taken by an individual per 1,000 inhabitants per day.

Prescribing increased from 21.6 DDD per 1,000 inhabitants per day in England in 2011 to 23 DDD per 1,000 inhabitants per day in 2014.

Infographic explaining defined daily dose of antibiotics per 1000 people living in England per day.

Many patients have been inappropriately prescribed an antibiotic, most commonly to treat:

- coughs and colds

- sore throats

- ear infections

Estimates suggest that as many as half of all patients who visit their GP with a cough or cold leave with a prescription for antibiotics. Viruses cause many of these infections, meaning antibiotics are of no use.

Infographic explaining antibiotic use by the public and patients in England per year.

What is fuelling antibiotic resistance

A third of the public believe that antibiotics will treat coughs and colds. 1 in 5 people expect antibiotics when they visit their doctor. GPs commonly express concerns that they feel pressurised by patients asking for antibiotics. For example, people asking on behalf of a child to treat infections that don’t respond to the drugs.

Antibiotic prescribing and antibiotic resistance are inextricably linked. Areas with high levels of antibiotic prescribing also have high levels of resistance.

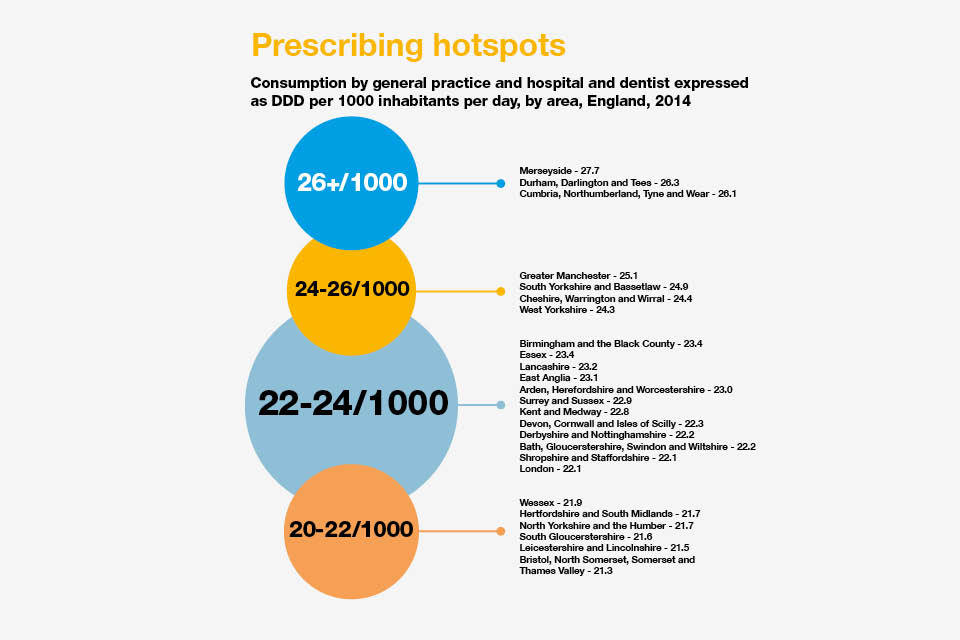

The highest combined general practice, hospital and dentist usage in England in 2014 was in Merseyside at 27.7 DDD per 1,000 inhabitants per day. This was 30% higher than in the Thames Valley, which had the lowest usage of antibiotics at 21.3 DDD per 1,000 inhabitants per day.

The highest prescribing from general practice was in Durham, Darlington and Tees at 21.1 DDD per 1,000 inhabitants. This was over 40% higher than in London which had the lowest level of antibiotic prescribing from general practice in England at 14.3 DDD per 1,000 inhabitants.

This may reflect healthcare access and delivery in London, where there may be a shift from general practice prescribing to local hospitals and private healthcare.

Inforgraphic explaining the precrisbing hotspots in England.

It’s not just inappropriate prescribing that is encouraging resistance to the drugs. The way people use antibiotics is also a big problem.

Patients must ensure that they take their antibiotics as prescribed, and do not:

- skip any doses

- share them with others

- stop taking them when they start to feel better

Why we need to act now

Antibiotics are a vital tool for modern medicine. Not only for the treatment of infections such as pneumonia, meningitis and tuberculosis. We also need them to avoid infections during chemotherapy, caesarean sections and other surgery.

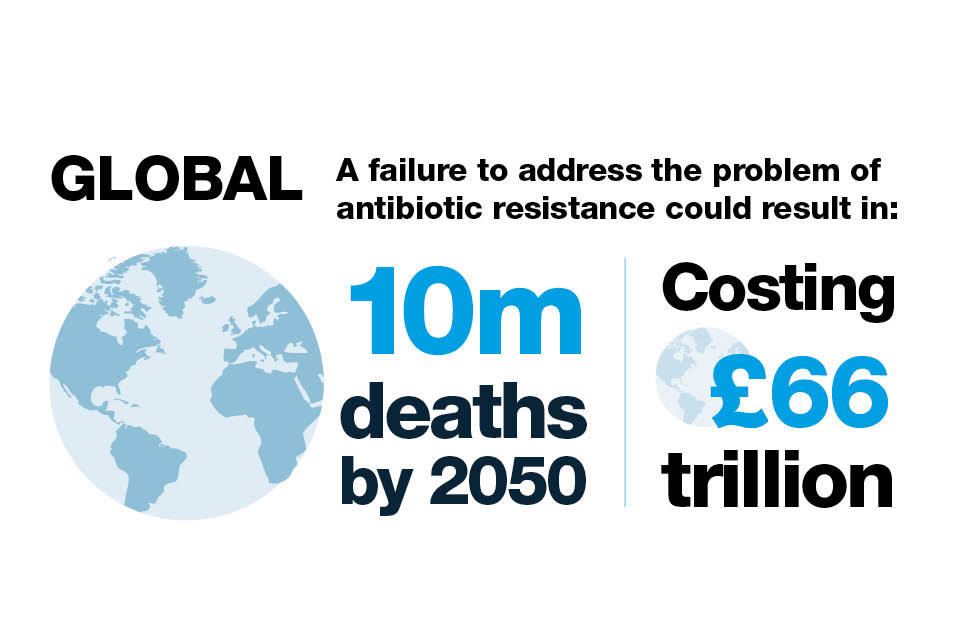

A failure to address the problem of antibiotic resistance could result in:

- an estimated 10 million deaths every year globally by 2050

- a cost of £66 trillion in lost productivity to the global economy

Infographic explaining the possible human and financial cost of failing to address antibiotic resistance.

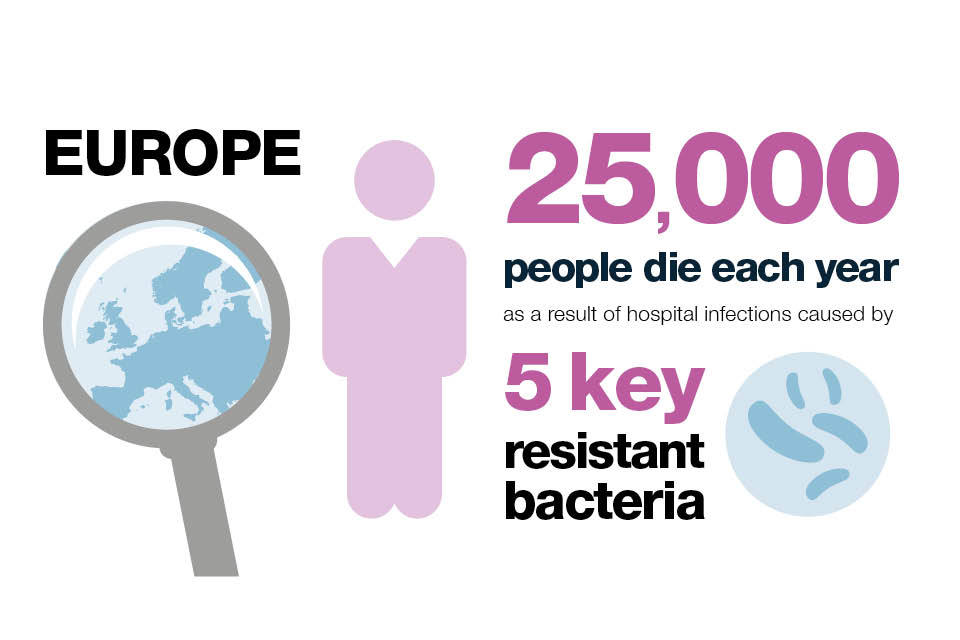

Across Europe, an estimated 25,000 people die each year as a result of hospital infections caused by the following 5 resistant bacteria:

- Escherichia coli (E. coli)

- Klebsiella pneumoniae (K.Pneumoniae)

- Enterococcus faecium

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)

This adds over £1 billion to hospital treatment and societal costs.

Infographic explaining how many people in Europe die each year as a result of hospital infection caused by 5 key resistant bacteria.

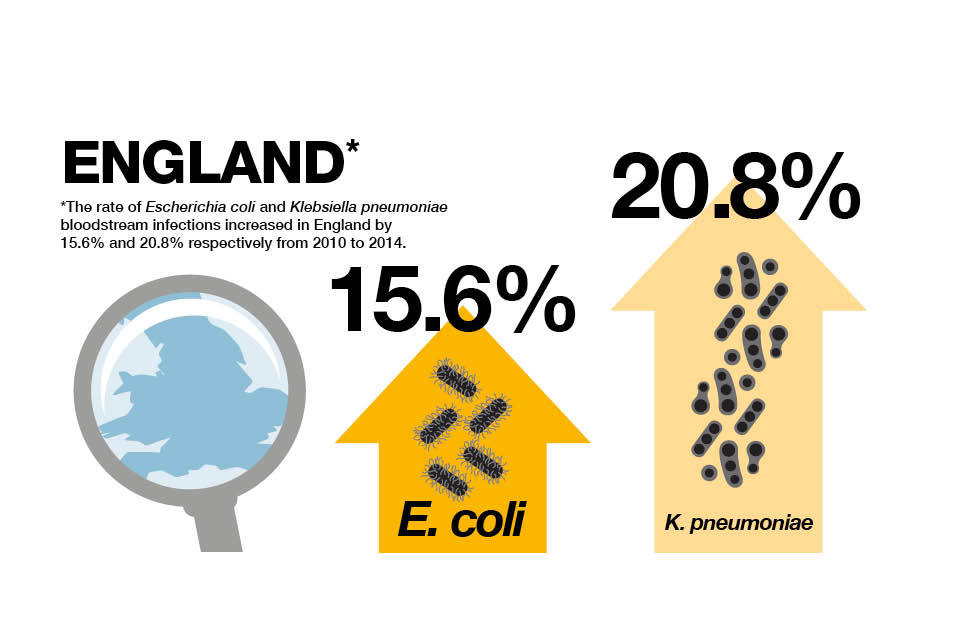

In England, E. coli is the most common cause of bacterial infection in the blood.

Although the proportion of E. coli that are resistant to antibiotics used to treat infections has remained constant, the increased incidence of bloodstream infections means that more individuals have had a significant antibiotic resistant infection.

Increases in K. pneumoniae bloodstream infections and the proportion of these infections which were drug resistant means the number of individuals with antibiotic resistant infections have increased substantially in the last 5 years.

Infographic explaining the increased rate of bloodstream infections from 2010 to 2014.

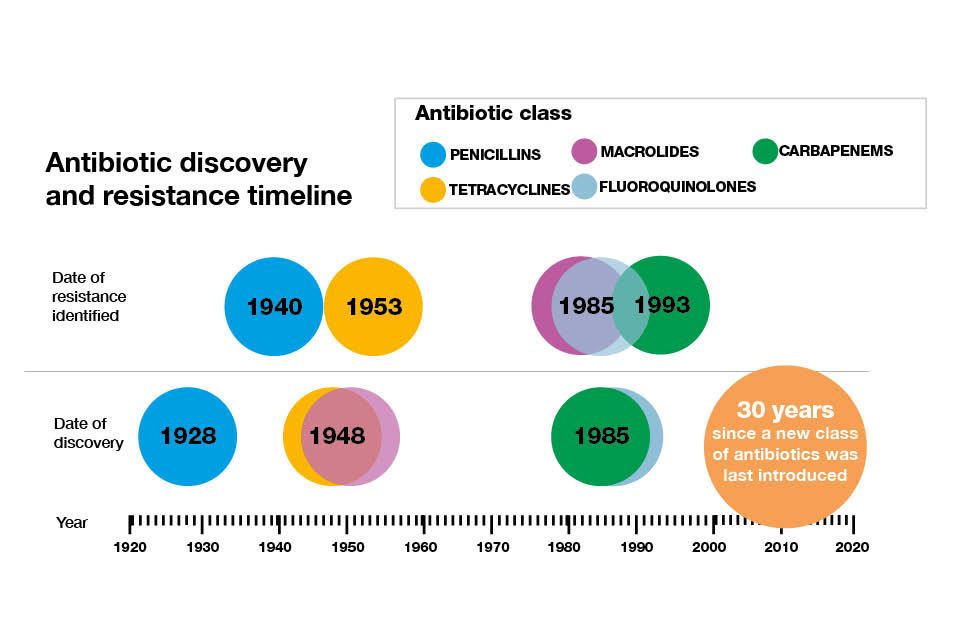

Global concern about antibiotic resistance is compounded by the fact that the discovery of new classes of antibiotics is at an all-time low. It has been 30 years since a new class of antibiotics was last introduced.

Only 3 of the 41 antibiotics in development have the potential to act against the majority of the most resistant bacteria.

An antibiotic discovery and resistance timeline.

The UK government considers the threat of antibiotic resistance as seriously as:

- a flu pandemic

- major flooding

Without action to address antibiotic resistance, doctors will lose the ability to treat infections. Routine operations could become deadly in just 20 years.

Encouraging responsible prescribing

Types of prescribed antibiotics and prescribers

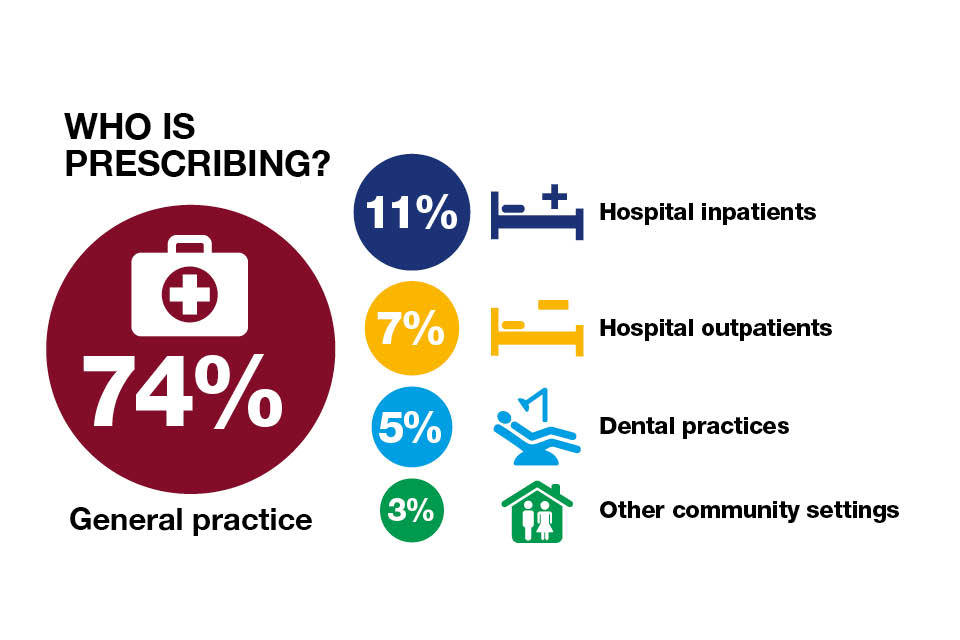

GPs are the first point of contact for most patients seeking medical help. The majority of antibiotics prescribed in England in 2014 were done so in general practice (74%).

Infographic setting out the percentage of antibiotic prescribers in England.

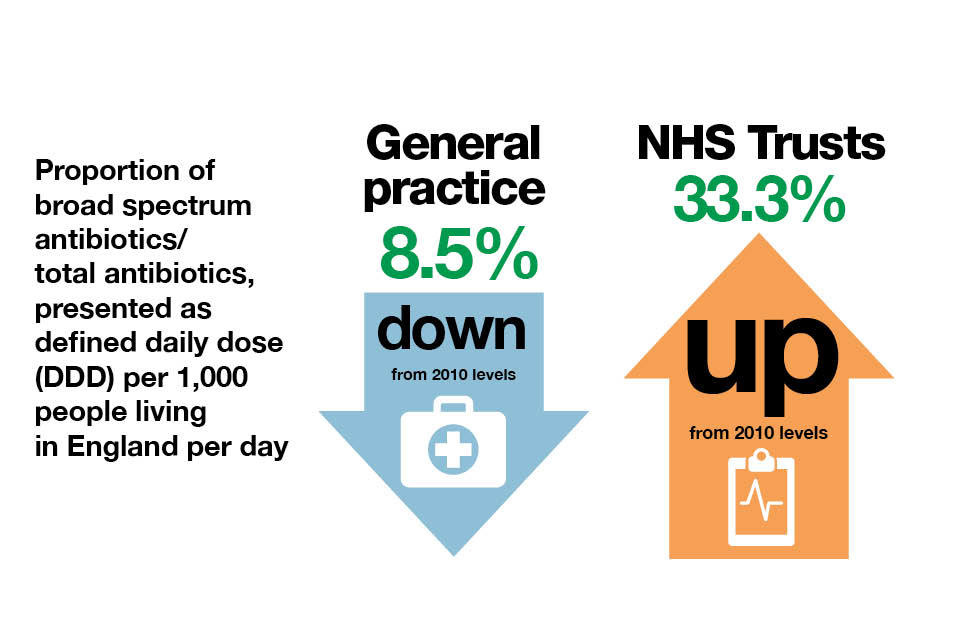

The amount of antibiotics consumed increased from 2010 to 2014 by 6.5%. However, antibiotic use measured in primary care:

- increased when measured by DDD

- decreased when measured by prescription

This suggests that longer courses or higher doses are being used.

Inforgraphic explaining the proportion of broad spectrum antibiotics

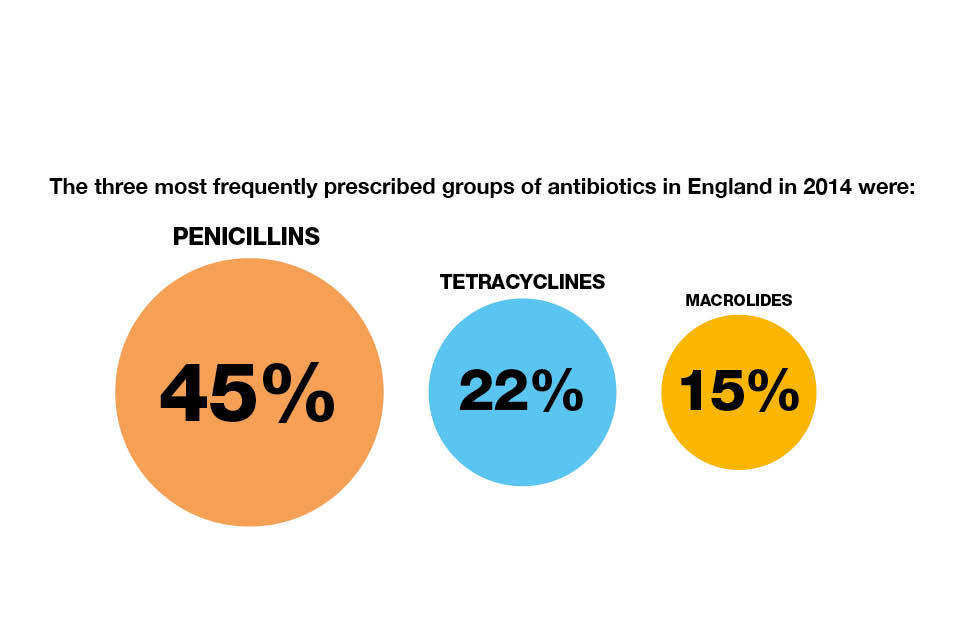

Penicillins are the most frequently prescribed antibiotic in general practice. Within secondary care, doctors tend to prescribe the “last line” broad-spectrum antibiotics, carbapenems and piperacillin-tazobactam, rather than narrow spectrum antibiotics. These antibiotics need to be reserved to treat resistant infections and used only when standard antibiotics are ineffective.

Infographic showing the 3 most frequently prescribed groups of antibiotics in England in 2014.

PHE has developed the English Surveillance Programme for Antimicrobial Utilization and Resistance (ESPAUR) programme. This monitors the way antibiotics are prescribed and obtained from pharmacies across the NHS in England.

Improvements

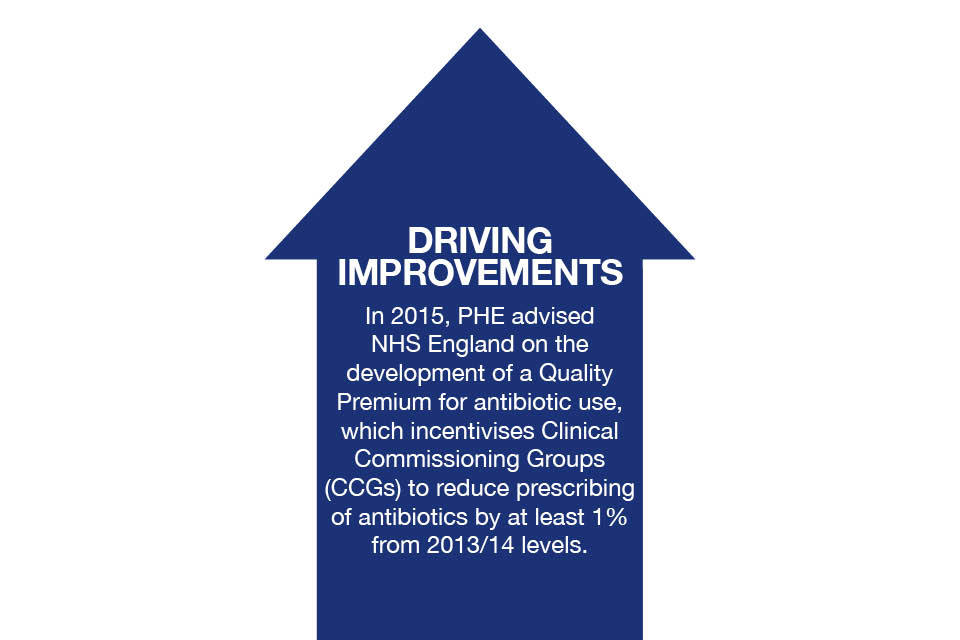

We can improve effective prescribing across England. There are a number of incentives in place to help healthcare professionals reduce antibiotic prescribing.

In 2015, PHE advised NHS England on the development of a Quality Premium for antibiotic use. This encourages Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) to reduce prescribing of antibiotics in primary care settings by at least 1% from 2013 to 2014 levels.

CCGs have also been asked to reduce broad-spectrum antibiotic prescribing as a percentage of the total antibiotics prescribed in primary care by 10% from each CCG’s 2013 to 2014 levels.

Within secondary care, the Quality Premium aims to ensure that secondary care providers, with 10% or more of their activity being commissioned by the relevant CCG, have validated their total antibiotic prescription data. The validated total antibiotic prescribing data will be available for each Trust at the end of each financial year on GOV.UK.

PHE is advising NHS England on appropriate areas of prescribing to incentivise in 2016.

Infographic explaining PHEs involvement in developing a Quality Premium for antibiotic use.

The influence of peers

Improving prescribing practice can be difficult, especially in the face of patient demand. Evidence suggests to inform prescribers of their prescribing patterns compared with peer professionals. This can then help them change their practice.

A national guideline on antimicrobial stewardship has been published by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). This recommends developing systems to provide regular updates to individual prescribers and prescribing leads on individual prescribing. These are benchmarked against local and national antimicrobial prescribing rates and trends collated by PHE.

PHE has developed a web-enabled surveillance system that provides a range of modern analytical tools to enable health professionals to:

- securely view laboratory data

- produce reports

In 2016, PHE will publish data on the PHE Public Health Profiles for local government and health services. This will relate to:

- healthcare associated infections

- antimicrobial prescribing

- antibiotic resistance

- infection prevention and control measurements

Toolkits to put guidance into practice

PHE has developed two national toolkits to support a reduction in inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in England. These are:

- Treat Antibiotics Responsibly, Guidance, Education, Tools (TARGET) for primary care

- ‘Start Smart, then Focus’ (SSTF) for secondary care

The NICE guidelines recommend that primary and secondary care healthcare professionals use these toolkits as part of their improvement of practice to assess their antibiotic prescribing rates against others.

The toolkits also provide advice on the importance of shared decision making with patients.

Infographic explaining how to encourage responsible prescribing.

Hygiene and infection control

All healthcare professionals have a role to play in educating the public about good hygiene practices, such as hand washing, and how this can prevent the spread of infection and reduce the need for antibiotics.

Diagnostic tests

There is a need for rapid diagnostic tools to help GPs identify within minutes the strain of bacterial infection present and the antibiotics to which it is resistant or susceptible.

The tests most readily available to most GPs are the C reactive protein (CRP) test and urinalysis, which provide an indication that infection may be present. CRP testing has reduced antibiotic prescribing for respiratory tract infections by 25%.

We all have a role to play

The situation is becoming critical. In the next few years, people could start dying of everyday infections that have become untreatable. We can ill afford to lose the power of antibiotics to treat infections.

Ensuring responsible and less frequent use of antibiotics will not happen overnight. It will require the full commitment and engagement of healthcare professionals and the public. Everyone has a responsibility and a role to play in making this happen.

One way to improve working together is to establish antimicrobial stewardship programmes led by antimicrobial stewardship teams. The NICE guideline on antimicrobial stewardship recommends this practice.

The recommended core members include an antimicrobial pharmacist and medical microbiologists. Additional members may include GPs and nurses.

Infographic illustrating how everyone has a role to play in beating antimicrobial resistance.

Local authorities

Directors of public health within local authorities can:

- work with stakeholders to provide information and advice to the public regarding steps they can take to address antimicrobial resistance

- work with CCGs to ensure effective antimicrobial stewardship

- support the implementation of the NICE guideline on antimicrobial stewardship

- ensure there are effective infection prevention and control governance arrangements in their local area

Health and Wellbeing Boards need to be aware of the strategic nature and priority of antimicrobial resistance. The topic must receive due attention in the Joint Strategic Needs Assessment and at Health and Wellbeing Boards.

GPs

Many GPs admit concern about what might happen if they withhold antibiotics. One way that has been shown to be effective is to issue a delayed or back-up prescription. Patients can then collect antibiotics at a later date if symptoms do not improve or get worse.

GPs should also highlight that taking an antibiotic is not risk free and can result in side effects including:

- diarrhoea

- thrush

- skin rashes

- vomiting

Involving patients in shared decision making can reduce the number of antibiotics prescribed for acute respiratory infections. This is promoted in the TARGET toolkit and the NICE guideline on antimicrobial stewardship.

The ideal process combines the best evidence about the benefits and harms of taking an antibiotic with the patient’s values and preferences, as part of a discussion with their GP. As a result, the GP and patient jointly make the decision about what to do next.

Hospital prescribers

Prescribers should ensure that they are up to date with local knowledge on the best antibiotic for each condition. They should seek advice from infection specialists when their patients are prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotics.

This will ensure appropriate use of these “last resort” antibiotics, preserving them for when they are needed.

Read a case study from the Royal Free Hospital explaining how a new drug chart improved antimicrobial stewardship.

Nurses

Nurses should use the principles of ‘making every contact count’ to influence public and patient knowledge and expectations of antibiotic prescribing.

Nurses have a big role to play in reducing inappropriate prescribing and can contribute through their roles in:

- infection prevention and control

- medicines management

- immunisation and vaccination programmes

- promoting health and well-being and immunity

Pharmacists

Community pharmacists have an important role in managing patient expectations about antibiotics.

They can support local GP practices and CCGs by providing:

- effective self-care advice and reassurance

- advice of what warning symptoms patients should look out for

- appropriate referral where required

They can also reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for flu symptoms by increasing uptake of flu vaccination.

There is a great opportunity for CCG lead pharmacists to make sure that antimicrobial stewardship is central to commissioning strategies. They can help to develop and co-ordinate a primary care antimicrobial stewardship programme.

Hospital pharmacists should work closely with the multidisciplinary clinical team to ensure antibiotics prescribed for inpatients are appropriate for their indication and compliant with local and national guidelines and protocols.

Directors of infection prevention and control

Directors of infection prevention and control within the NHS, as well as medical and nursing directors, should ensure that they have an active surveillance programme of antibiotic resistance and antibiotic use.

Antimicrobial stewardship and microbiology laboratory teams should ensure their laboratory is reporting antimicrobial resistance data to PHE.

Medical Royal Colleges and Health Education England

Undergraduate and postgraduate curricula should include topics on antibiotic use and resistance. Use the PHE and Antimicrobial Resistance and Healthcare Associated Infections (ARHAI) antimicrobial prescribing and stewardship competences to develop learning content.

Schools, colleges and universities

Educational settings provide opportunities to raise awareness among students about preventing infections and reduce the need for antibiotics. This includes:

- the importance of hand washing

- vaccination uptake

- other hygiene measures

Become an Antibiotic Guardian

Logo for the Antibiotic Guardian campaign.

PHE is urging all healthcare professionals and members of the public to become an Antibiotic Guardian and help overcome antimicrobial resistance.

Over 25,000 people have already signed up, with a goal to reach 100,000 Antibiotic Guardians by 31 March 2016.

Together we could achieve this goal if one in every 25 NHS clinical staff, one in every 100 NHS non-clinical staff, and one in every 1000 members of the public across the UK register to become Antibiotic Guardians.

Why we are aspiring to this

By encouraging people to become Antibiotic Guardians and collecting pledges, we can go beyond simply raising awareness and help people to take at least one concrete personal action, leading to much wider changes in behaviour.

Download a complete set of references for this document.