Implementation and 4-month outcomes report: Evaluation of the Health-led Employment Trials

Updated 8 April 2024

Applies to England, Scotland and Wales

DWP research report no.1033

A report of research carried out by the Institute for Employment Studies on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence.

To view this licence, visit the National Archives

Or write to:

Information Policy Team

The National Archives

Kew

London

TW9 4DU

Email: psi@nationalarchives.gov.uk

This document/publication is also available on our website at: Research at DWP

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email: socialresearch@dwp.gov.uk

First published July 2023.

ISBN 978-1-78659-545-4

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Executive summary

This report provides detailed insights into the implementation of the Health-led Employment Trial and a descriptive analysis of respondents to the survey that was undertaken 4 months post randomisation. It then explores the counterfactual impacts that could be discerned at this intermediate measurement point.

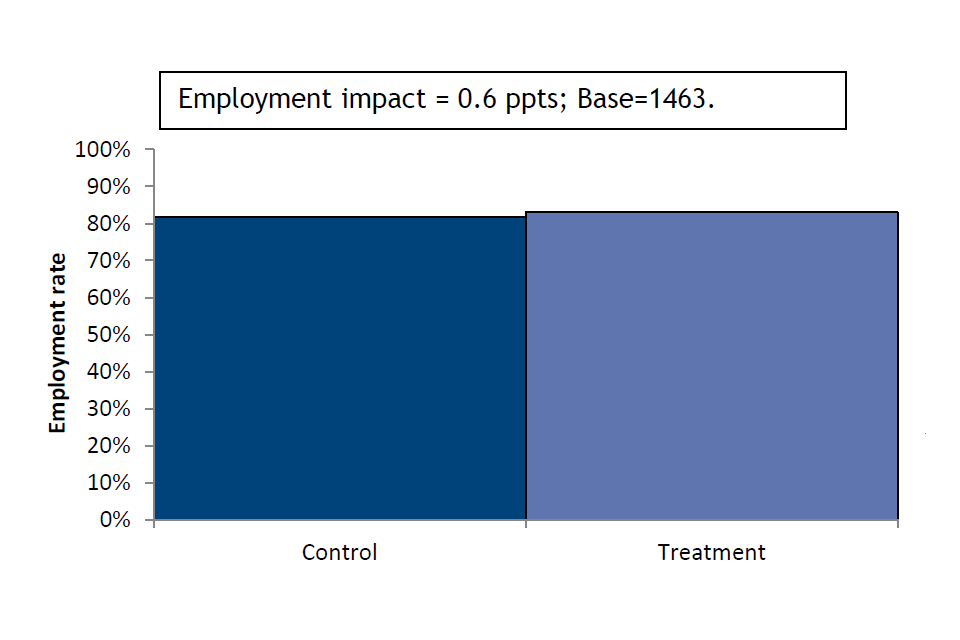

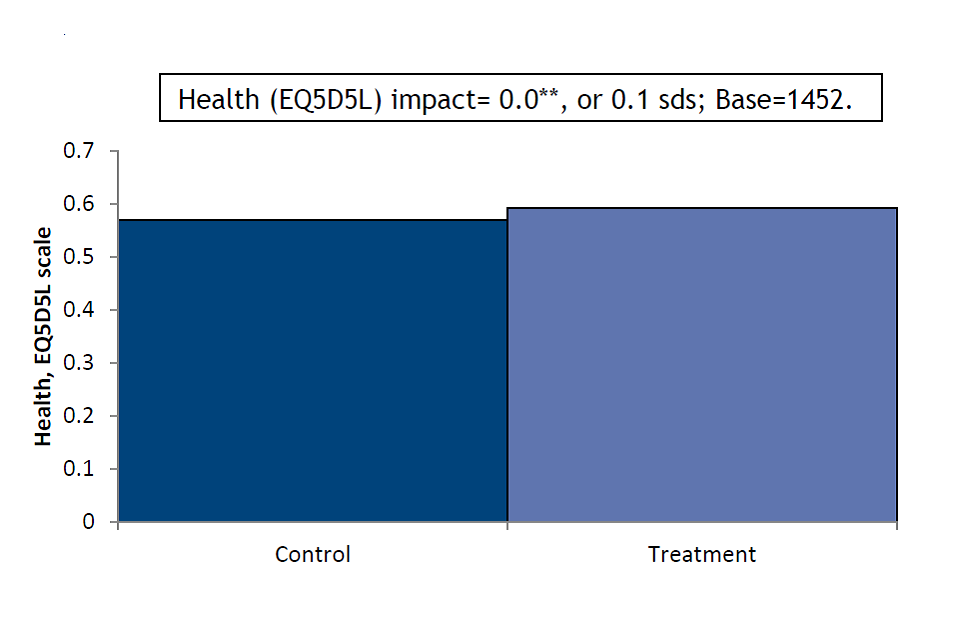

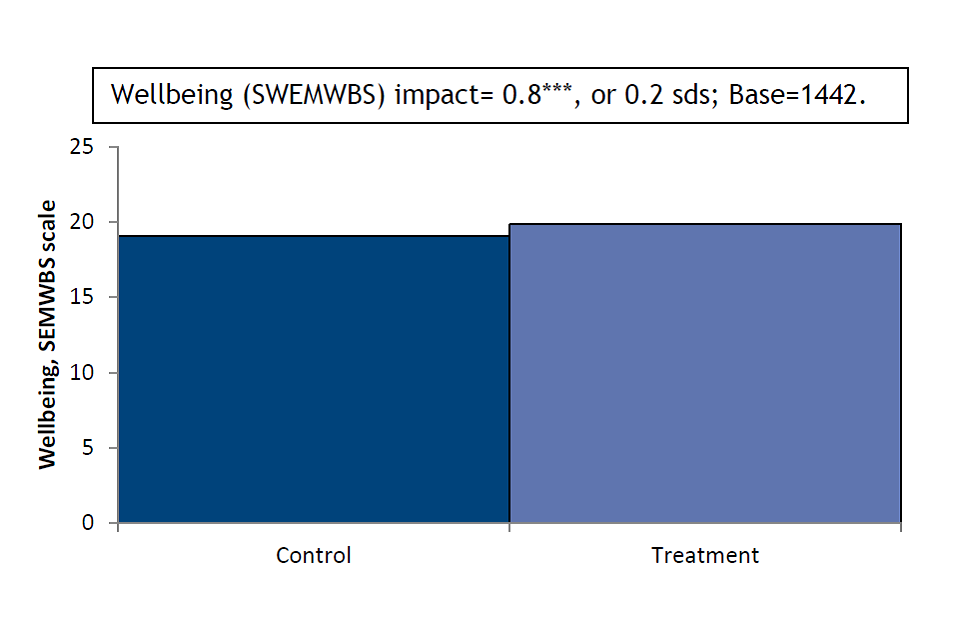

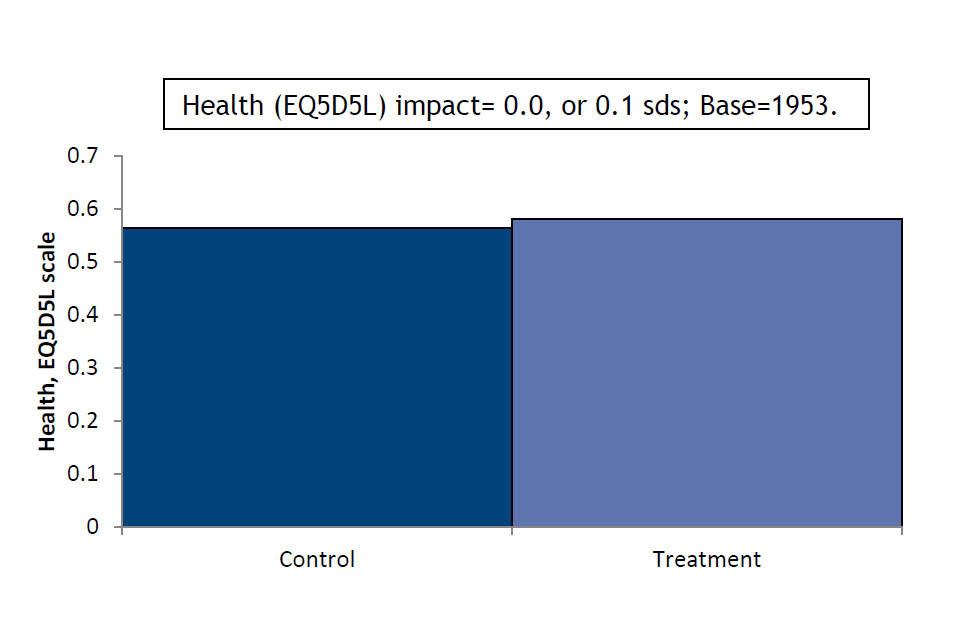

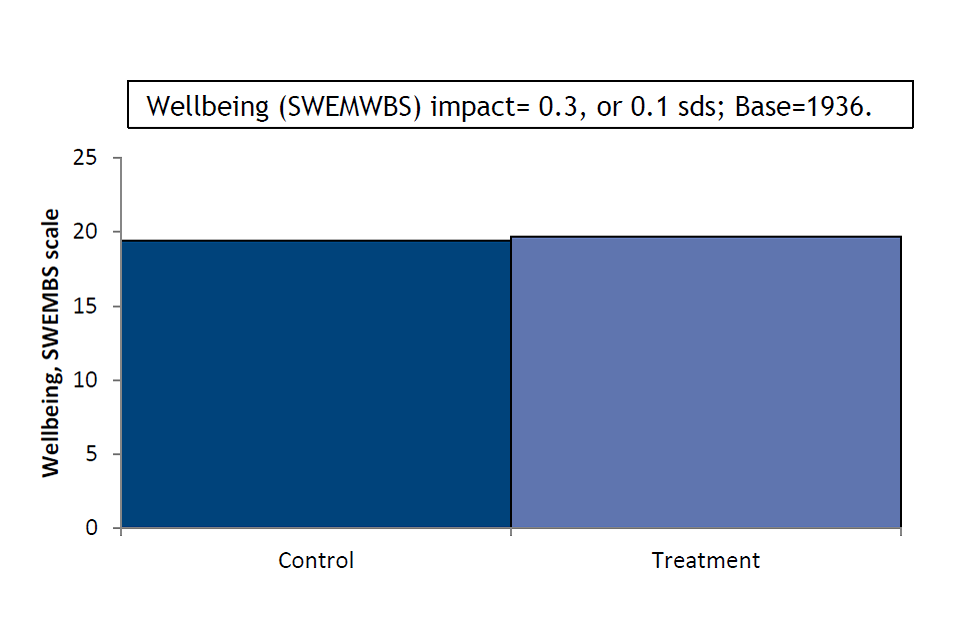

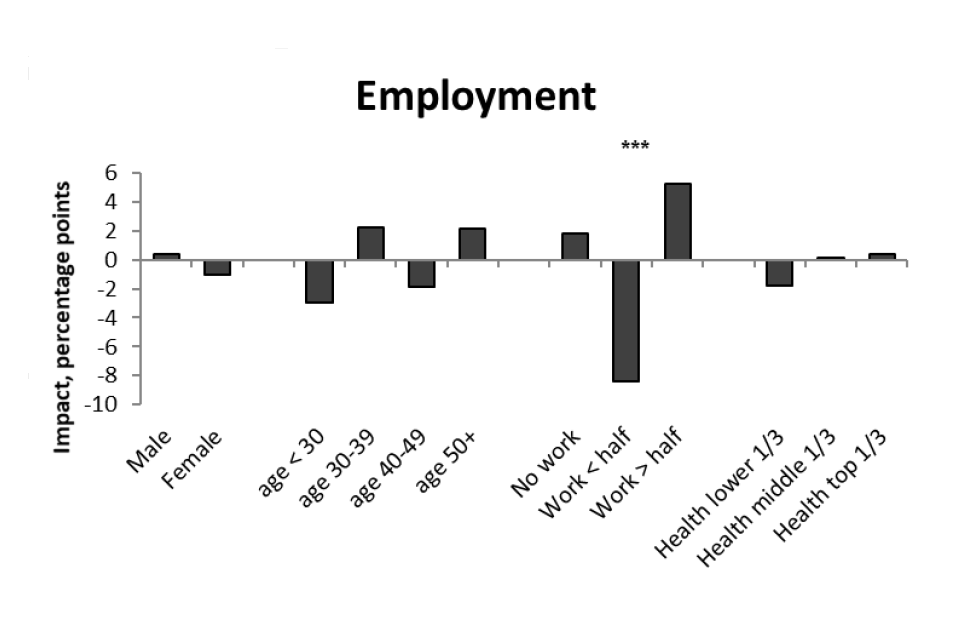

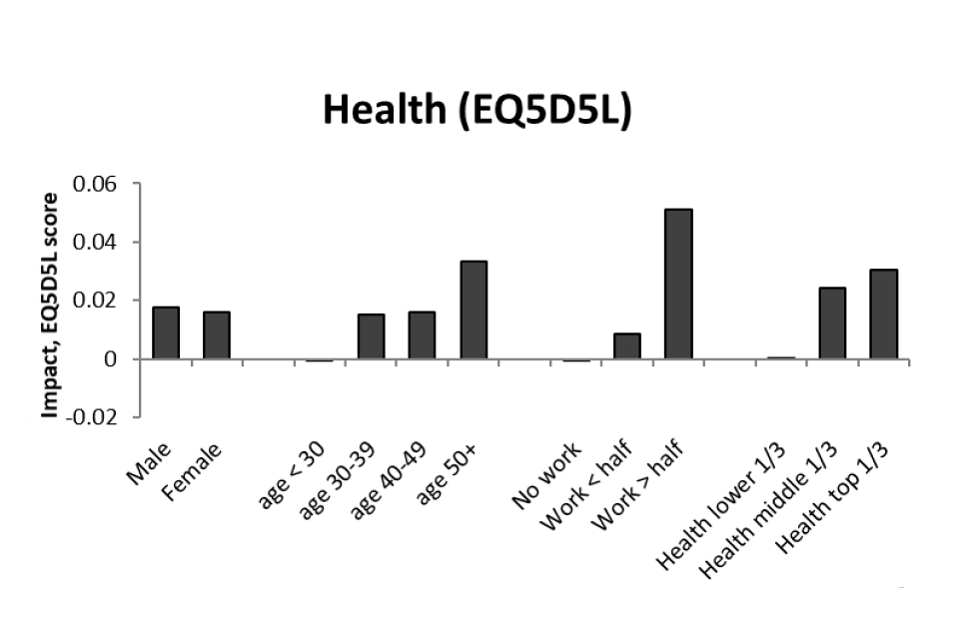

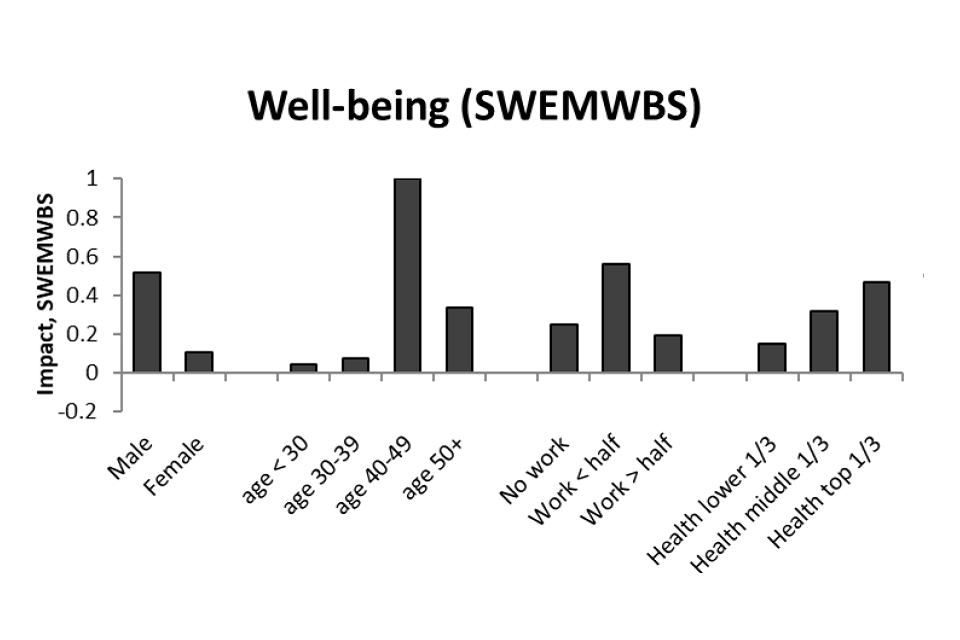

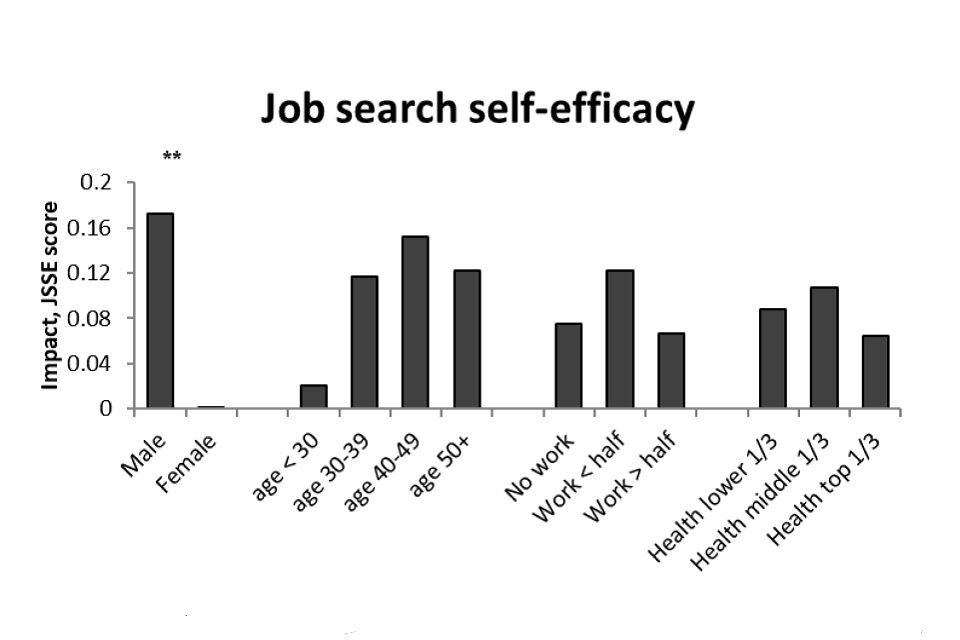

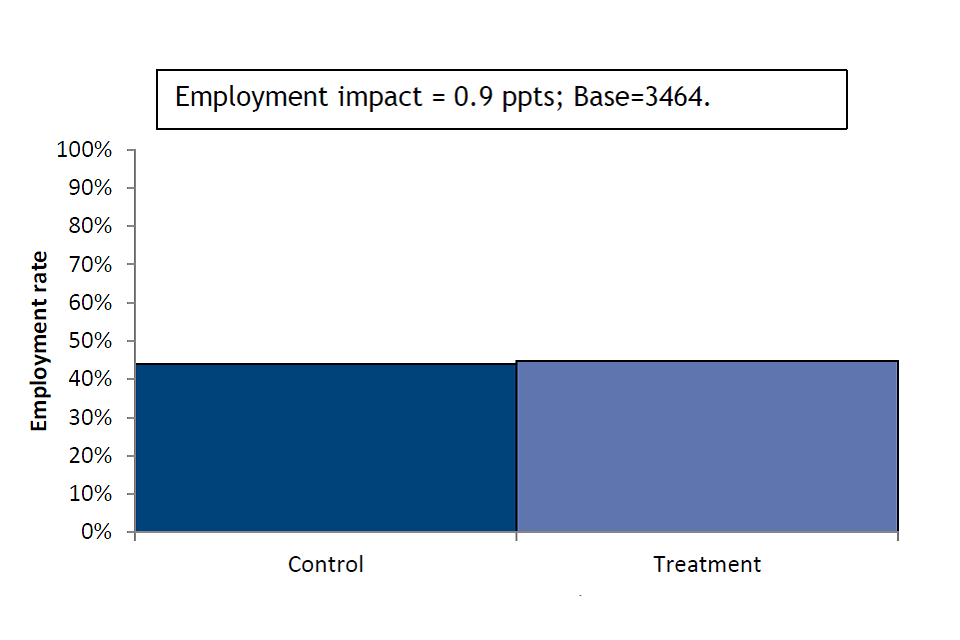

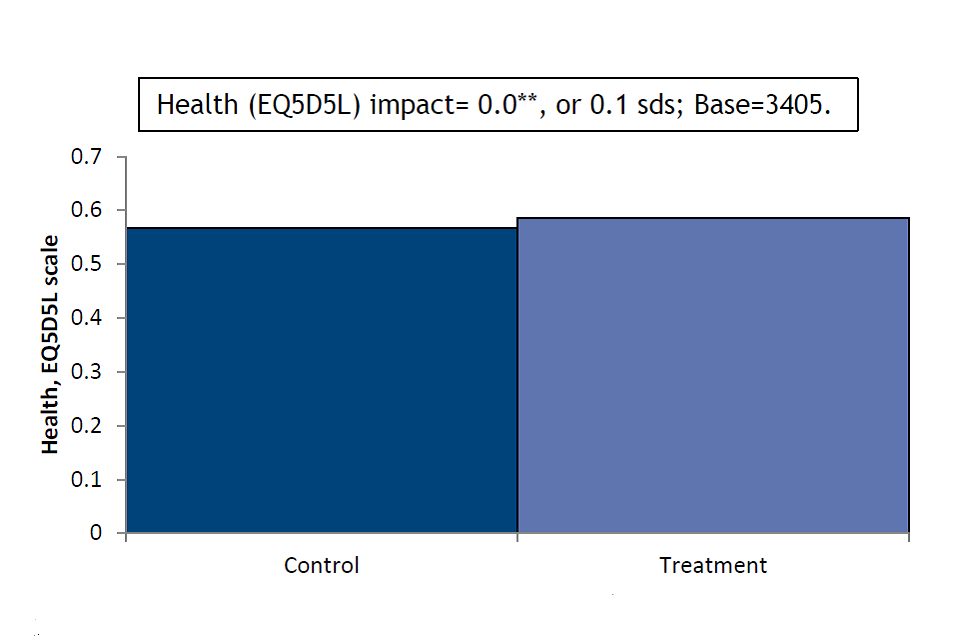

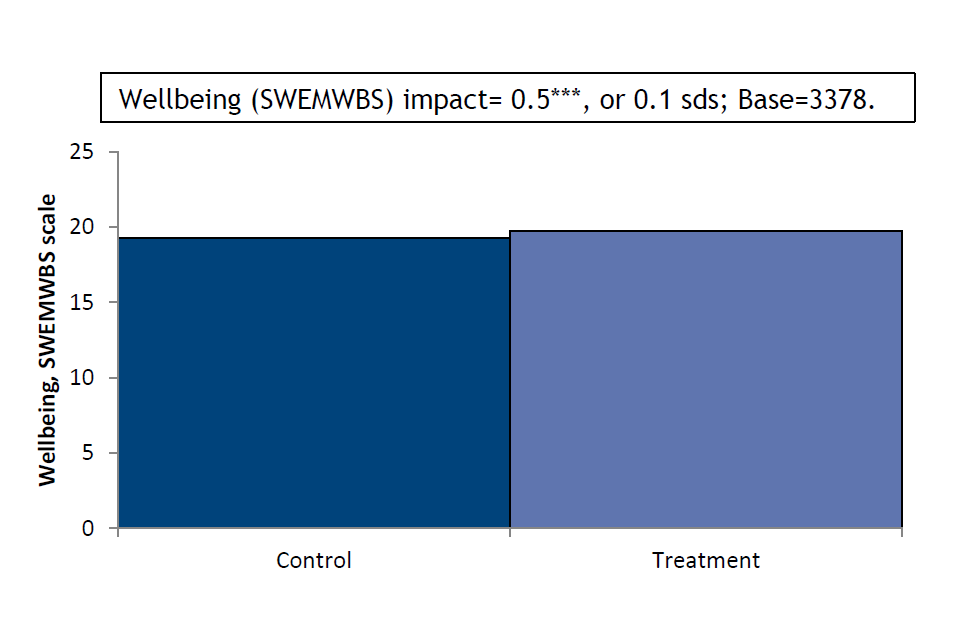

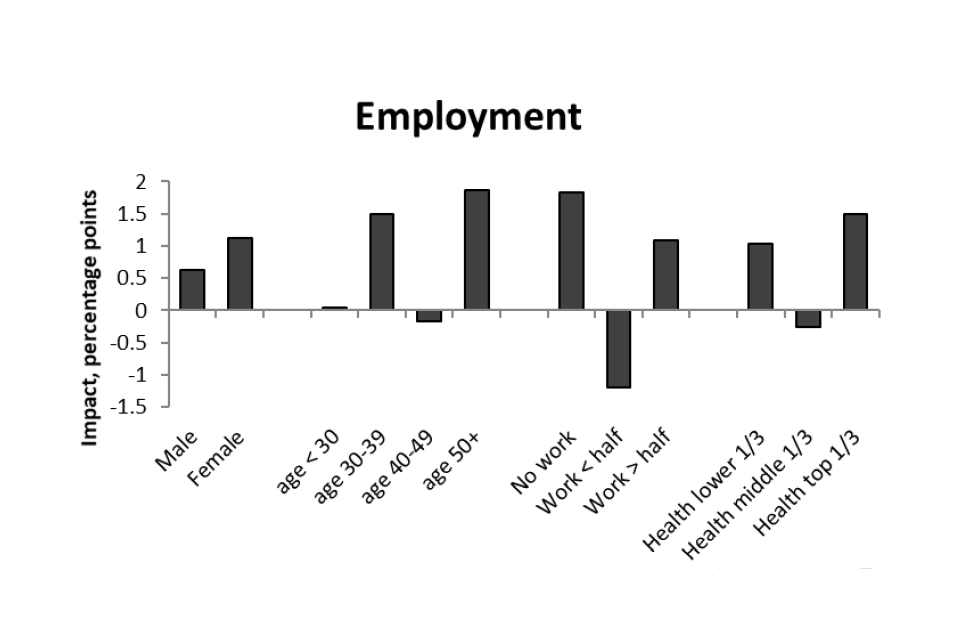

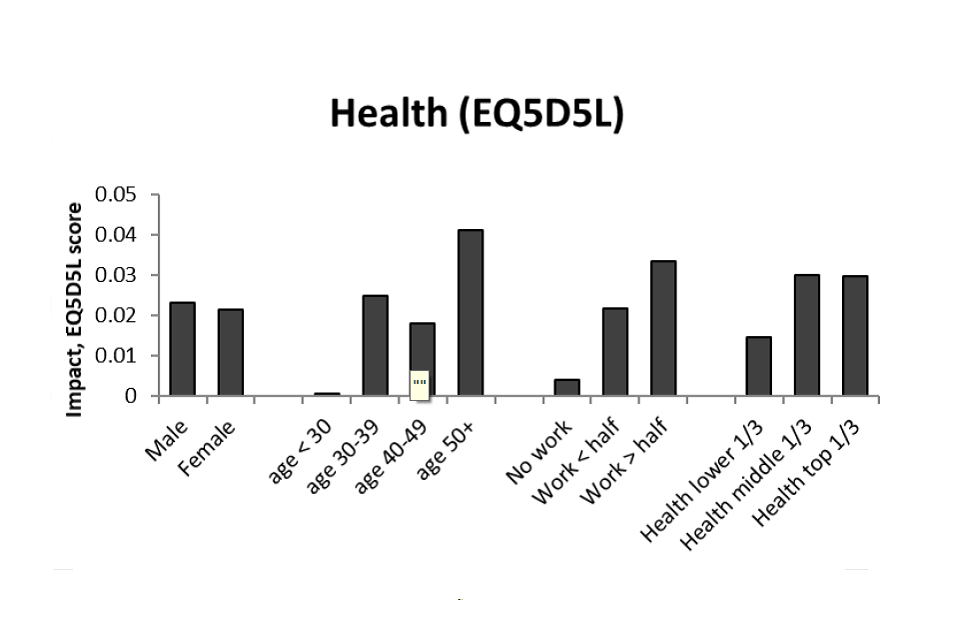

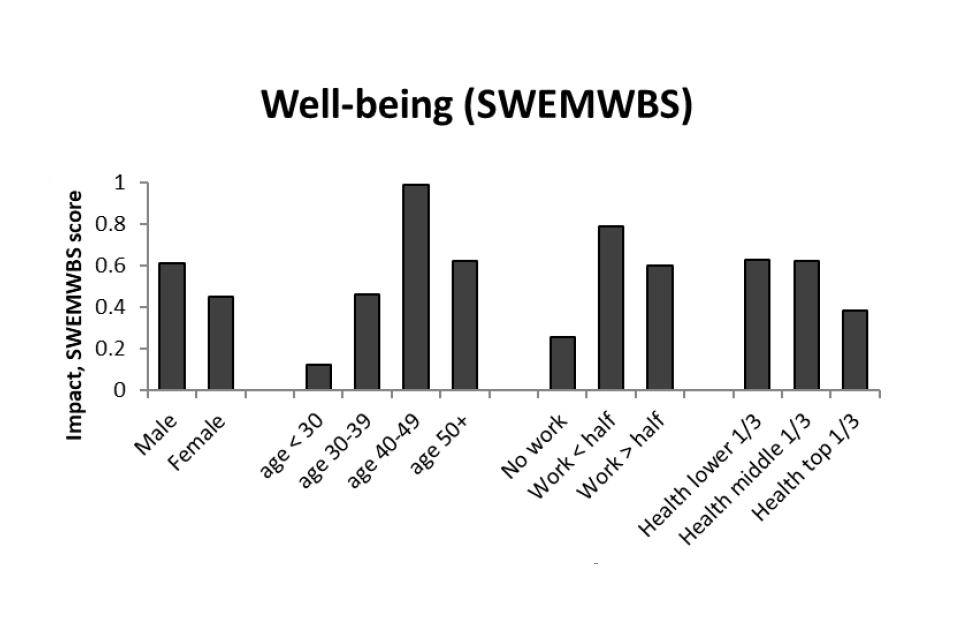

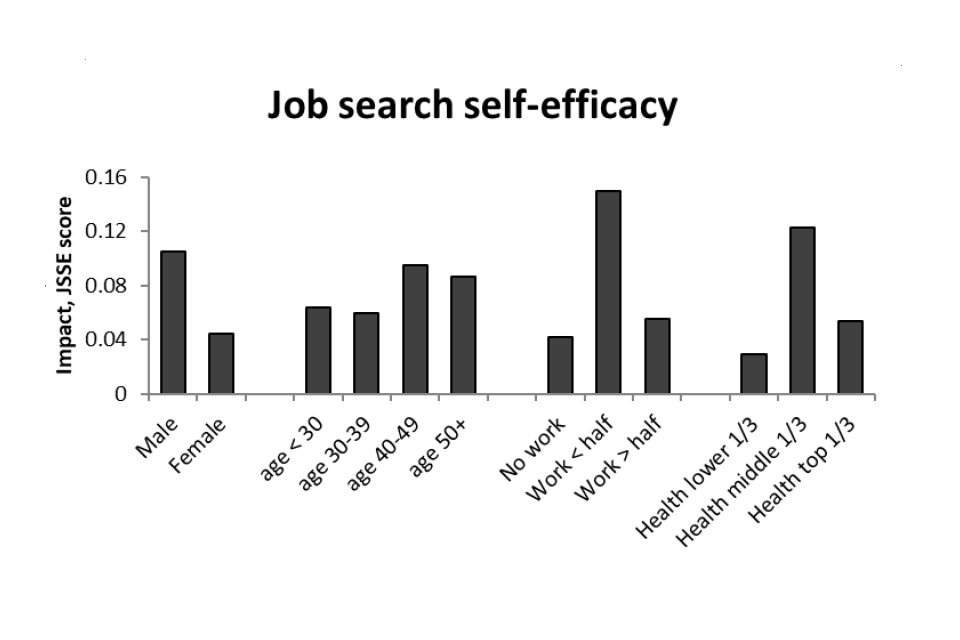

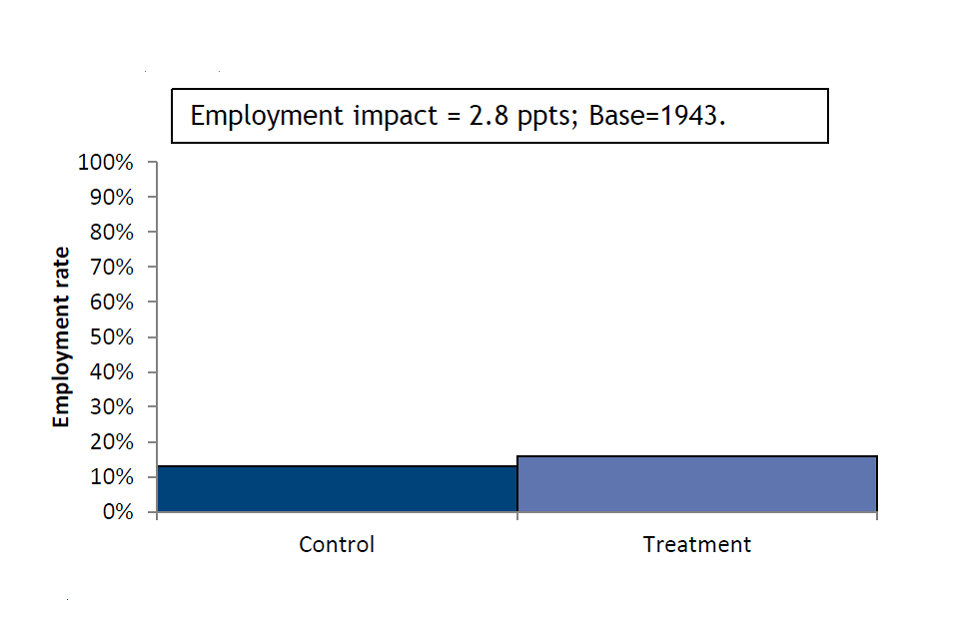

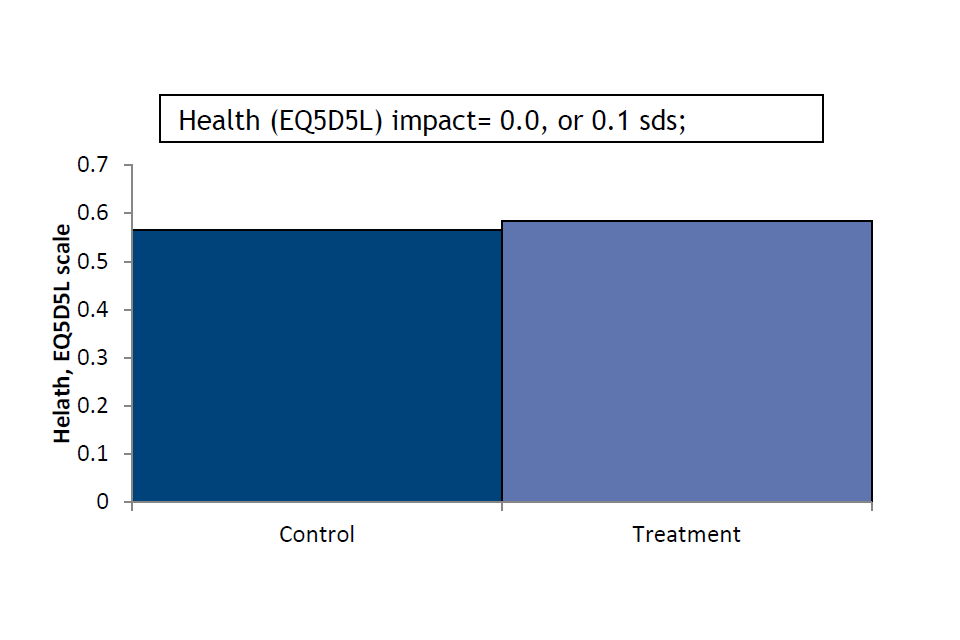

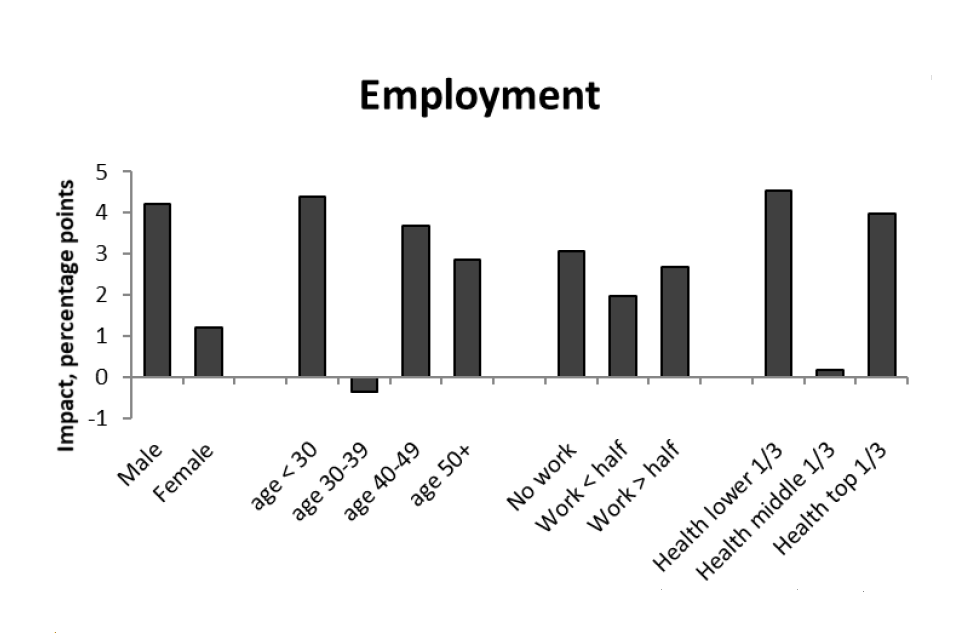

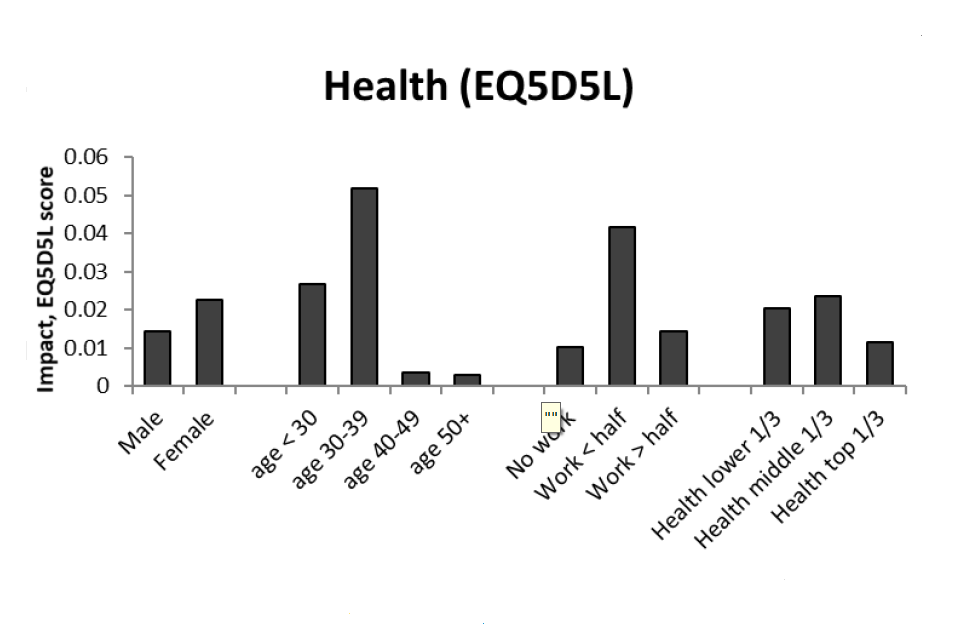

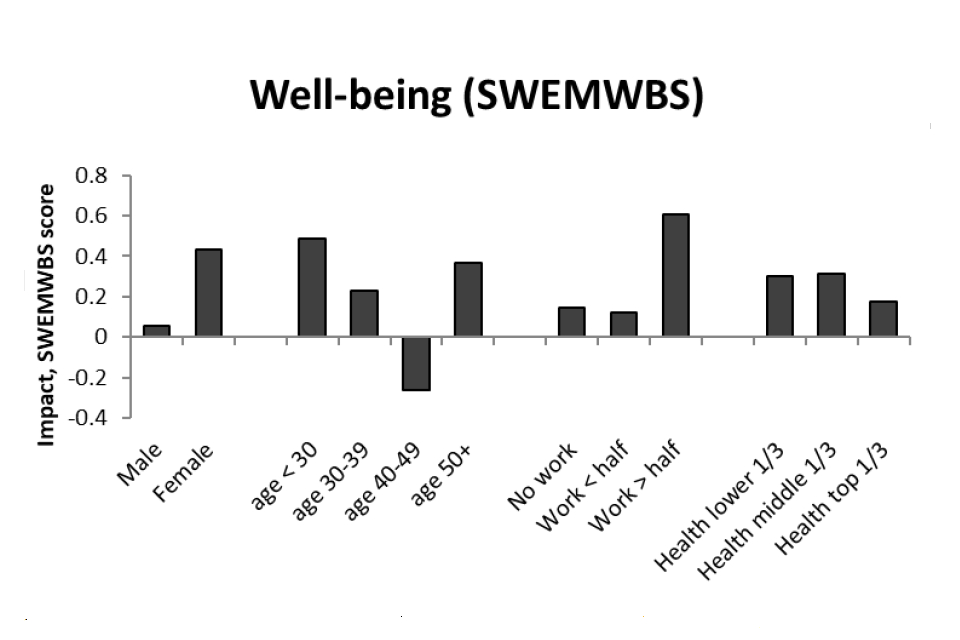

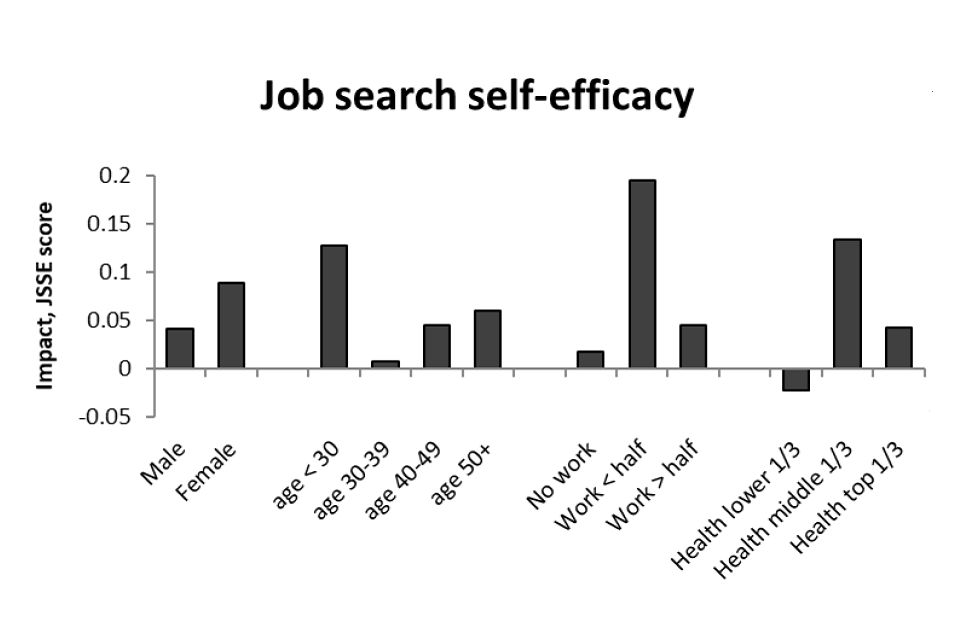

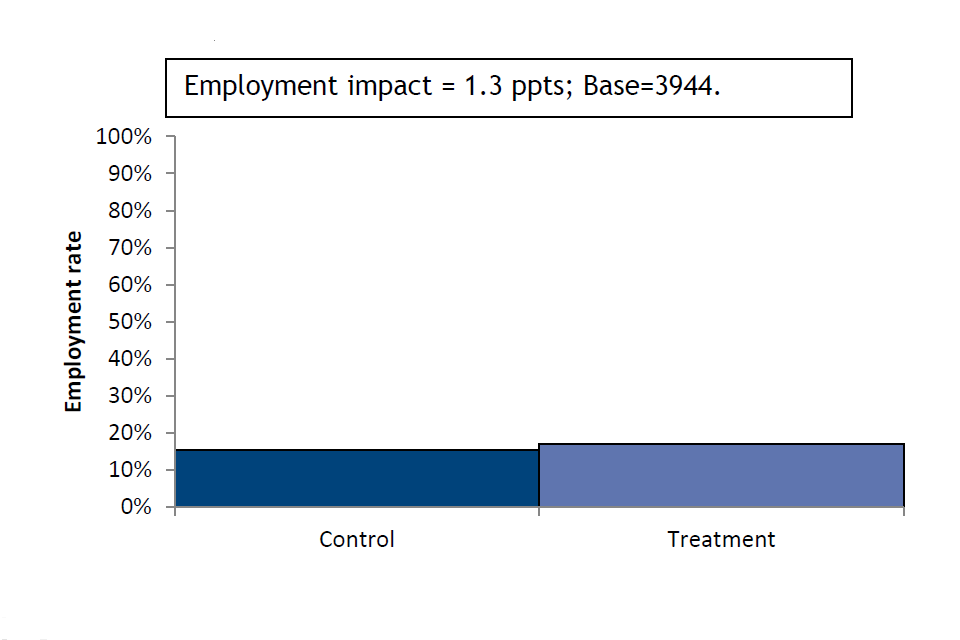

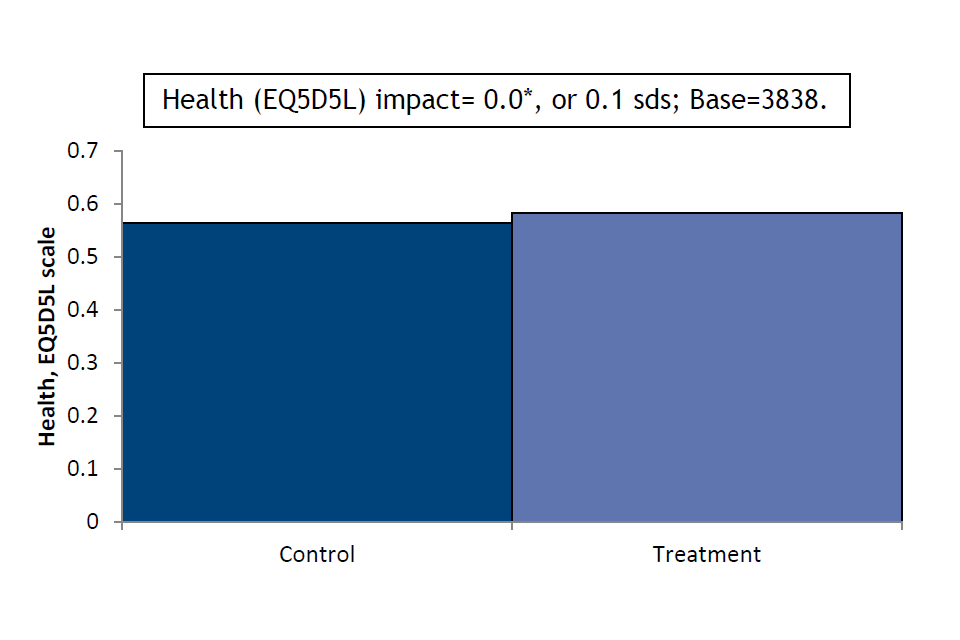

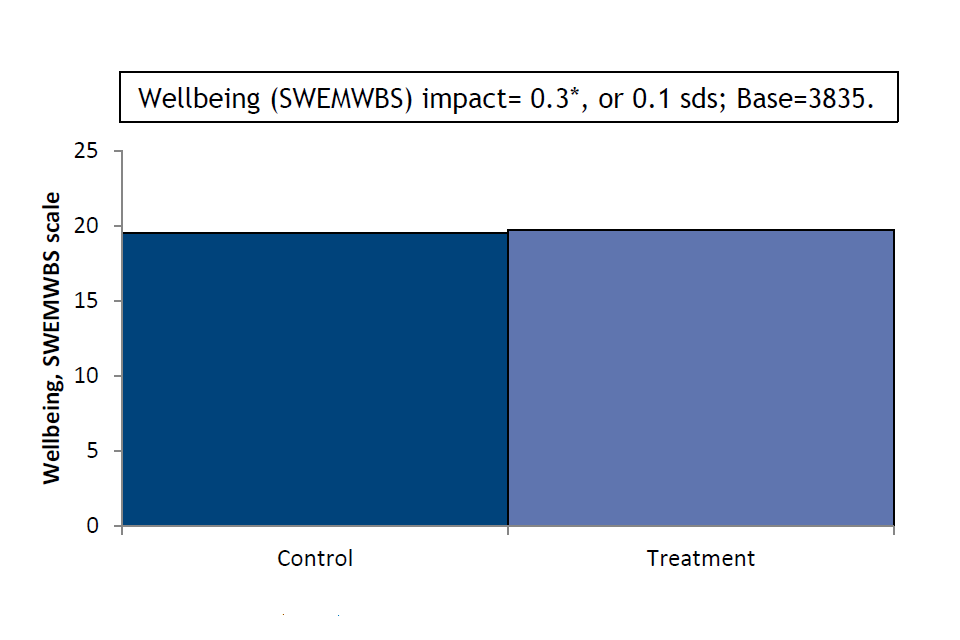

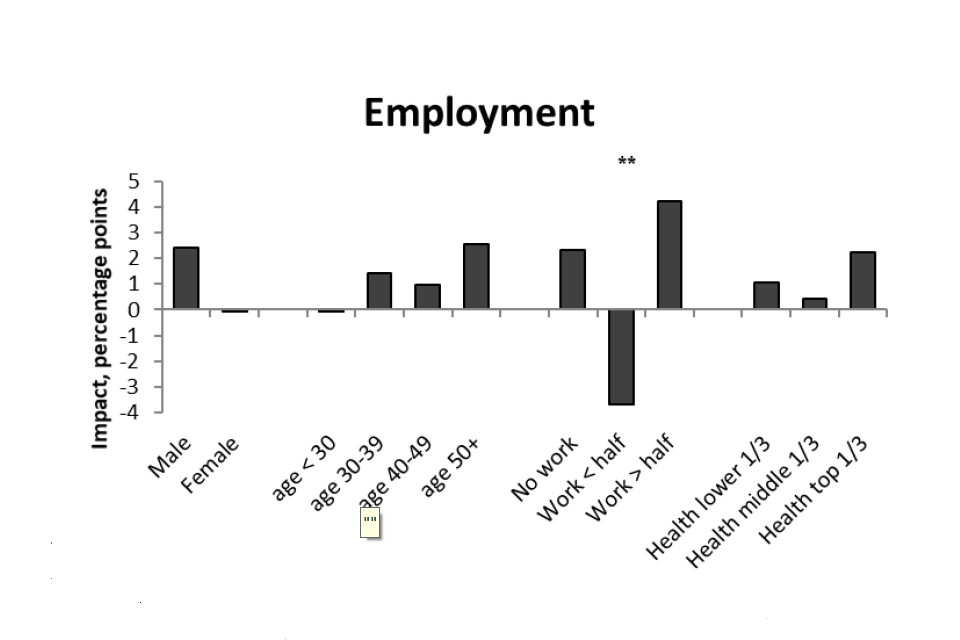

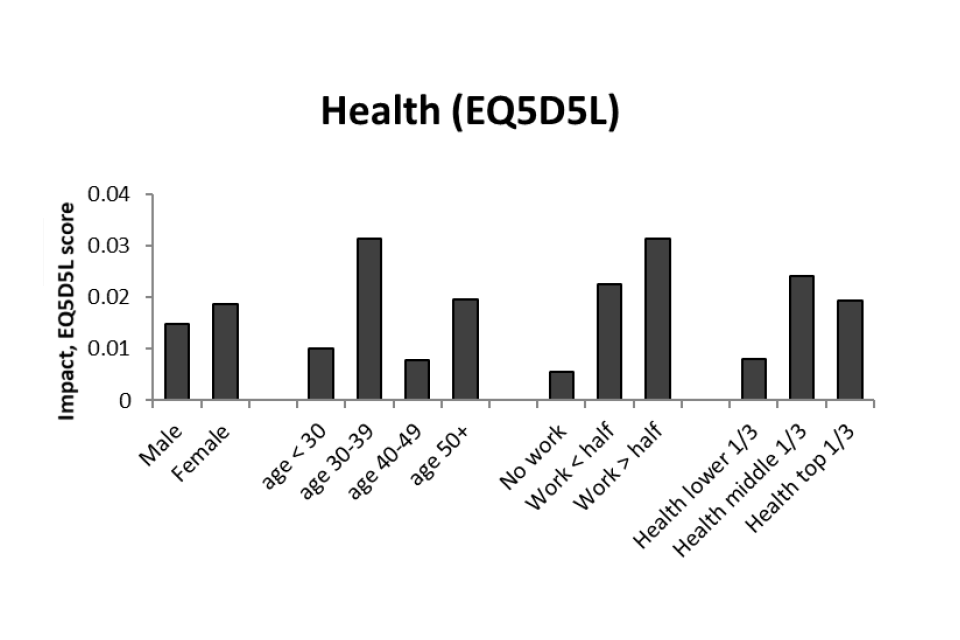

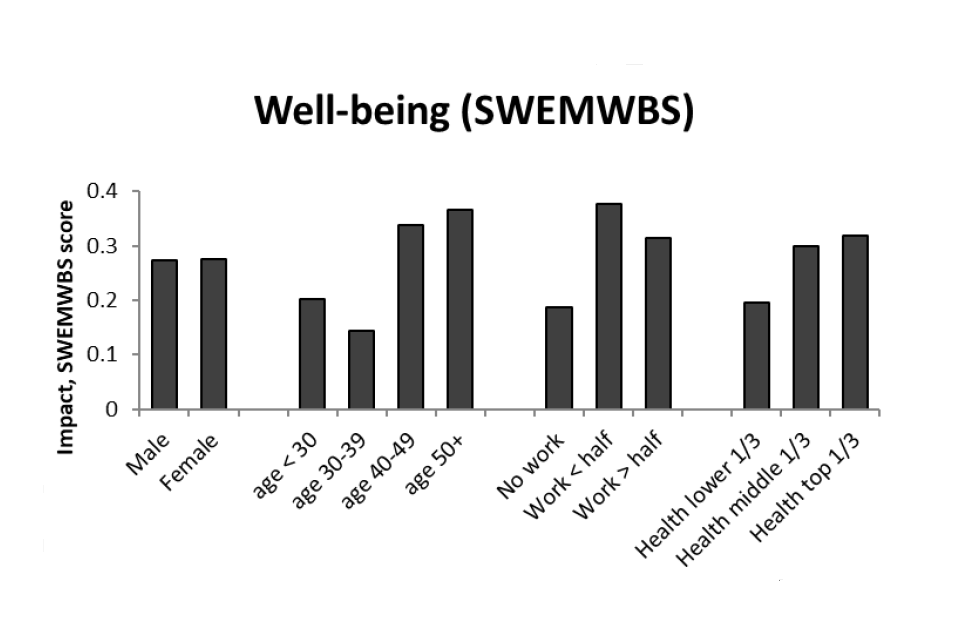

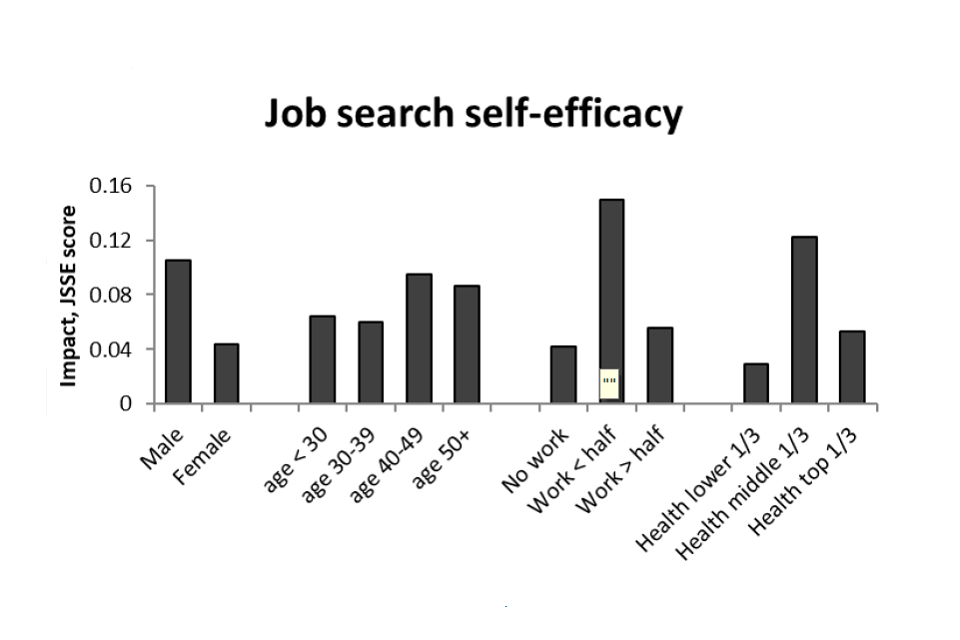

Four months after randomisation, the impact evaluation observed improvements in the treatment group’s confidence in their ability to look for and obtain employment, and small positive effects on the health and wellbeing primary outcome measures – all factors on the causal pathway established for the trial. The survey showed high degrees of satisfaction with the service provided.

The process evaluation provided insights into how the trial was implemented in each area, the issues and challenges encountered and factors that supported effective delivery. Some key lessons included the importance of ongoing staff training and particularly focusing on building capability for employer engagement, as employment specialists could struggle with this; continued attention to relationships with GPs and health partners to foster support; the importance of location in community settings as well as being able to co-locate with other services which supported integration. Equally, if recruits in future are sourced from Jobcentre, findings indicated the importance of continued briefing on the voluntary nature of IPS support.

Throughout the report, references are made to information and tables contained in the appendices report, ‘Evaluation of the Health-led Employment Trials: Appendices to the 4-month outcomes report’ – which is the companion piece to this, the main report from the 4-month evaluation. These references take the form of (Appendices, Chapter x, Table x:x).

The final report series for the trials covers:

- synthesis report – a high-level, strategic assessment of the achievements of the trial, drawing together the range of analyses from the evaluation.

- four-month outcomes report covering: an analysis of implementation, a descriptive analysis of the survey findings 4 months post-randomisation, and an assessment of impact at 4 months following randomisation.

- 12-month survey report providing a descriptive analysis of the final survey, based on the theory of change for those in the treatment group.

- context-mechanism-outcome (CMO) report, reporting evidence on outcomes from the trials and relating these to its theories of change.

- 12-month impact report covering the net effect on employment, health and wellbeing resulting from the trials 12 months after randomisation drawing on administrative and survey data.

- economic evaluation report exploring the costs and benefits arising from trial delivery, drawing on the administrative and survey data.

- the pandemic and the trial – an analysis of how the trial outcomes may have been affected by the onset of COVID-19.

Authors’ credits

Becci Newton is Director of Public Policy Research at the Institute for Employment Studies and specialises in research on unemployment, inactivity, health, skills and labour market transitions. Becci has managed the evaluation since its design and contributed to the process evaluation. She has led multiple evaluations for DWP including of the 2015 ESA Reform Trials and the Work Programme.

Rosie Gloster is a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute for Employment Studies. She supported the management of the evaluation consortium and contributed to the process evaluation. She is a mixed-methods researcher specialising in employment, and careers. She has authored several reports for the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), including the Evaluation of Fit for Work.

Richard Dorsett is Professor of Economic Evaluation at the University of Westminster. He has worked on numerous impact evaluations, mostly in the fields of employment, welfare and education/training. He led on the statistical design of the trials and the impact analysis.

James Cockett is a Research Fellow (Economist) at the Institute for Employment Studies. He has supported the 4-month impact analysis of the Health-led Trials. He is a Labour Economist with a particular interest in labour market transitions of disadvantaged groups. James has authored reports for both the Low Pay Commission and the Social Mobility Commission in his early career.

Matthew Gould is a Lecturer in Economics at Brunel University London. His research specialises in applying theory and computation to a range of economic problems. He has worked on several projects focussed on education, employment and taxation. He led on the development and maintenance of the randomisation tool.

Dr Karen Windle is Director of Health and Social Care at NatCen Social Research. She has extensive experience of complex research and evaluation assessing effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a range of innovative programmes and interventions. Karen is programme director of the Health-led Trials at NatCen, responsible for supporting the delivery and analysis of the 4-month and Final Surveys. Joe Crowley is a Senior Researcher in the Health and Social Care team at NatCen Social Research. His main methodological expertise lies in survey data collection and analysis. He has worked across a variety of large-scale surveys, including NatCen’s flagship British Social Attitudes survey and Family Resources Survey.

Amelia Benson is a Senior Researcher in the Health and Social Care team at NatCen Social Research. Her primary areas of research cover health, welfare and the labour market. Recent projects include an evaluation of the Personal Support Package for DWP and a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)-funded report into tobacco control measures in Europe and the UK.

James Yarde is a Senior Statistician at NatCen Social Research. He has supported the weighting of the surveys for the Health-led Trials. In his role at NatCen he is responsible for the sampling and weighting of surveys, as well as undertaking analytical work. His work covers a range of random probability surveys, including British Social Attitudes and the National Travel Survey.

Imogen Martin is a Research Assistant in the Health and Social Care team at NatCen Social Research. She has worked on areas across the policy spectrum including healthcare, disabilities and welfare. As part of the Health-led Trials, Imogen has assisted with the delivery and analysis of the 4-month and Final Surveys.

Becca Gooch is a Research Manager at Learning and Work Institute. She managed part of the process evaluation. She is a mixed-methods researcher who has worked on a range of research and evaluation projects, with a focus on employment, equalities and disadvantage within employment.

Jess Elmore is a Researcher at Learning and Work Institute. She contributed to the process evaluation. She is a qualitative researcher who has worked across a range of projects with a focus on disadvantaged or hard-to-reach groups and their access to education and employment.

Seana Friel is a Researcher at Learning and Work. She contributed to the process evaluation. Seana works on a range of research and evaluation projects at L&W, and has experience of conducting research with a variety of populations including disadvantaged groups such as care leavers, disabled people, people experiencing multiple disadvantage as well as people experiencing homelessness.

Joanna Hofman is a Research Leader at RAND Europe focusing on research and evaluation in the fields of employment and social policy. She has led several evaluations of the Individual Placement and Support (IPS) including of IPS for Alcohol and Drug Dependence for Public Health England (PHE). She contributed to evidence reviews that informed the trial design and this synthesis report and advised throughout the evaluation.

Rebecca Duffy is a Project Support Officer at IES who led proofing and formatting of this report.

Glossary of terms

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Area | A defined, geographic area within a trial site |

| Base | The number of observations or cases in a sample. For example, a survey may have a base=2,300 respondents. During analysis the base may become smaller, e.g. if not all respondents answer a question, or when analysing responses a subset of the full sample. |

| Baseline data collection | Data from the baseline assessment completed by provider staff who recruited people to the trial. |

| Binary variable | A variable measured with only two possible values: hot and cold, 0 and 1, or happy / unhappy. More complex variables (such as a happiness scale from 1 to 7) are sometimes re-coded as binary values during analysis. |

| Bivariate analysis | The analysis of two variables for the purpose of determining the statistical relationship between them. |

| Causal link | The connection between a cause and an effect. |

| Controlling for | In statistical modelling with multiple variables and factors, keeping one variable constant so to examine and test the relationship and effect between other variables in the model. |

| Correlation | In statistics, the association or relationship between two variables, not necessarily causal. For example, the rings in a tree trunk increasing with the age of the tree is an example of positive correlation. |

| Dataset | A collection of data or information such as all the responses to a survey or all the recordings from a set of research interviews. |

| Demographic | A particular section of the population. Also refers to characteristics of an individual of interest for research, such as age, gender, and ethnicity. |

| Derived variable | A variable that was not directly asked in a survey, but created at analysis stage, for example by merging two or more variables. |

| Descriptive analysis | Producing statistics that summarise and describe features of a dataset such as the mean, range and distribution of values for variables. |

| EuroQol-5D-5L (EQ5D5L) | Descriptive system for health-related quality of life states in adults, consisting of five dimensions (Mobility, Self-care, Usual activities, Pain & discomfort, Anxiety & depression), each of which has five severity levels described by statements appropriate to that dimension |

| Employment specialists | Staff employed by the trials to undertake randomisation appointments, provide IPS support to the treatment group, and undertake employer engagement. |

| Final survey | The survey completed by recruits 12 months after randomisation. |

| Health-led Employment Trials | Two trials, funded by the Work and Health Unit, to test a new model of employment support for people with long term health conditions. |

| 4-month survey | The survey completed by trial recruits four months after starting the trial. |

| Intervention | The work and health support provided in Sheffield City Region and the West Midlands Combined Authority as part of the trial. |

| In employment/working | Those in employment full-time, part-time, or less than 16 hours a week; those who are self-employed. |

| In paid work | Those in employment full-time, part-time, or less than 16 hours a week, not those who are self-employed |

| Individual Placement and Support (IPS) | IPS is a voluntary employment programme that is well evidenced for supporting people with severe and enduring mental health needs in secondary care settings to find paid employment. |

| IPS fidelity scale | A scale developed to measure the degree to which IPS interventions follow IPS principles and implement evidence-based practice. |

| Job search self-efficacy | Nine item scale to measure self-efficacy relating to finding employment. |

| Longitudinal surveys | Repeated surveys that study the same people over time. |

| Multi-morbidity | The occurrence of multiple chronic conditions within the same individual where no single condition holds priority over the co-occurring conditions. This term was selected as the evaluation does not hold information about the main condition affecting recruits. |

| Participants | Recruits allocated to treatment, who had 2+ meetings with an employment specialist. This is used in the 4-month impact analysis to differentiate between those who experienced limited support beyond randomisation, as in the impact evaluation intention to treat is the basis for analysis. Other terms are used to describe people taking part in the trial (recruits) and people taking part in the surveys (respondents) – see below. |

| Prevalence | The extent to which something occurs in a population or group, often expressed as a percentage. |

| Provider staff | Those working in provider organisations including employment specialists delivering IPS support, as well as managers and administrators |

| p-value | A measure of statistical significance. Low p-values indicate results are very unlikely to have occurred by random chance. p<0.05 is a commonly cited value, indicating a less than 5 per cent chance that results obtained were by chance. Research findings can be accepted with greater confidence when even lower p-values are cited, for example p<0.01 or p<0.001. |

| Randomised controlled trial | A study to test the efficacy of a new intervention, in which recruits are randomly assigned to two groups: the intervention group receives the treatment, the control group receives either nothing or standard treatment. |

| Recruits | People who agreed to take part in the trials and who were randomised to either the treatment or control group |

| Refer / referral | A recommendation that an individual should be considered for the trial, facilitated by a means to directly connect them to a trial provider |

| Respondents | Trial recruits who took part in the evaluation surveys. As such the descriptive analysis of the survey identifies treatment group respondents and control group respondents |

| Self-refer / self-referral | Individual applies for more information about the trial via the trial website or helpline and uses information there (phone number, web form, email) to make contact with the trial provider and request support. |

| Signpost | Recommendation to an individual from a support organisation that they consider joining the trial, by providing them with information (leaflets, reference to website or helpline) leading potentially to the individual self-referring into the trial |

| Site | The trials were delivered in two combined authorities, termed sites. |

| Statistical significance | This indicates that a result is unlikely to be caused by chance (to a specified degree of confidence) and can be accepted as valid. The significance level is the probability of the study rejecting the null hypothesis (that there is no relationship between two variables), demonstrated by the p-value of the result. |

| Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale | SWEMWBS is a short version of the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS). It was developed to enable the monitoring of mental wellbeing in the general population. |

| Survey | A research tool used to collect data by asking scripted questions or using lists or other items to prompt responses. |

| Tenure | Housing arrangement or status of an individual, for example owner occupier, private renter, or local authority or housing association renter. |

| Theory of Change (ToC) | A description and illustration of how and why a desired change is expected to happen in a particular context. It sets out the planned major and intermediate outcomes and how these relate to one another causally. |

| Thrive into Work | The name given to the trial in WMCA |

| Trial arm | This denotes the allocation of recruits to the treatment or control group, with these groups known as the trial arms |

| Trial group(s) | There are three trial groups: two out-of-work (OOW) groups (one in each combined authority), an in-work (IW) group in Sheffield City Region (SCR). Groups are pooled as All OOW and All SCR in the analysis |

| Variable | A variable is defined as any individual or thing that can be measured. |

| Weighting | During analysis of survey data, adjusting for over- or under-representation of particular groups, to ensure that the results are representative of the wider population. |

| Working Win | The name given to the trial in SCR. |

1. Process evaluation findings: Sheffield City Region

This chapter presents findings from the process evaluation of the Health-led Employment Trials in the Sheffield City Region (SCR)[footnote 1]. It documents recruitment to the trial and the delivery of support. It also covers intermediate outcomes, and the causal mechanisms it was possible to detect for these.

1.1. Introduction

The research reported in this chapter is based on the mix of interviews shown in Table 1-1. The analysis focuses on capturing information on implementation in order that lessons for delivery can be learned.

Table 1-1: Interviews in SCR

| Fieldwork period | Respondent type | SCR interviews |

|---|---|---|

| – | Recruits: treatment group | 24 |

| September to November 2018 | Staff | 14 |

| September to November 2018 | Stakeholders and partners | 5 |

| April to June 2019 | Recruits: treatment group | 11 |

| April to June 2019 | Recruits: Control group | 8 |

| April to June 2019 | Treatment group: Longitudinal panel 1 | 10 |

| April to June 2019 | Treatment group: Longitudinal panel 2 | 12 |

| April to June 2019 | Staff | 9 |

| January to March 2020 | Recruits: treatment group | 13 |

| January to March 2020 | Recruits: control group | 9 |

| January to March 2020 | Treatment group: longitudinal | 12 |

| January to March 2020 | Staff | 11 |

1.1.1. Local context in the site

The trials were designed differently in WMCA and SCR. These different approaches made it more challenging to separate out the impact of local contextual factors from the impact of the different approaches to commissioning. In SCR, the five local authorities and health bodies (CCGs) in the region came together to design the trial. This partnership commissioned a single provider – South Yorkshire Housing Association (SYHA) – to deliver the trial. A key difference was that in SCR the trial accepted people who were out-of-work (OOW) as well as people who were in-work (IW) who needed support to move roles or return to work after a period of sickness, whereas the trial in WMCA recruited only people who were unemployed.

1.2. Accessing the trial

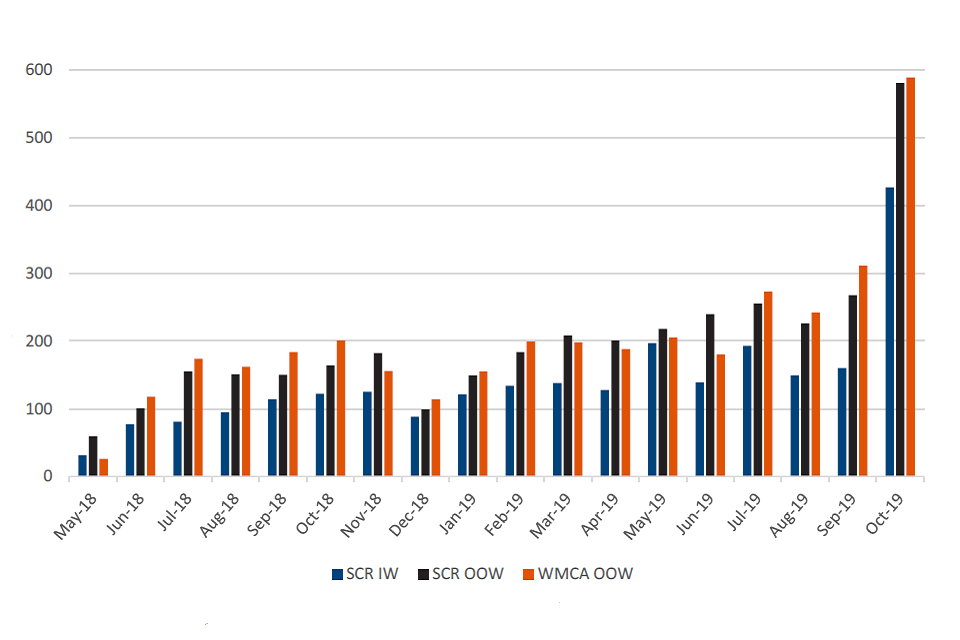

Staff across SCR sought to raise awareness with potential recruits, healthcare professionals, and other organisations that could make referrals. These activities continued throughout the trial, and intensified in the run up to the end of the referral period in October 2019.

1.2.1. Awareness raising

The main referral routes planned for the trial were primary care (e.g. through GPs), community care (e.g. Increasing Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) services), and self-referral. All promotional materials and messaging were approved by the Health Research Authority (HRA) to ensure they were clear, balanced and ethical in approach. In SCR, the trial was branded Working Win and the marketing strategy was developed by staff at the city region level.

Figure 2.1: Referral sources in SCR

| Referral source | % |

|---|---|

| Local GP | 18 |

| Specialist care service | 26 |

| Other or self referral | 56 |

Source: Service provider MI

Figure 1-1 shows the sources of referral in SCR; just under a fifth of recruits were referred by their GP, a quarter by a specialist care service, and more than half either self-referred or were referred by another organisation, a pharmacist for example. Recruits interviewed for the process evaluation had been referred by sources, including primary and community health services, or had self-referred after finding out about the trial through marketing materials or at local job fairs.

Engaging and activating primary and community care providers on recruitment

The trial planned for primary and community care providers to be the main source of referrals. The goal of raising awareness with these providers was to initiate an ongoing relationship whereby healthcare providers would refer patients to the trial, and integrate their work to enable individuals’ complex needs to be supported in a co-ordinated way.

The trial in SCR was commissioned via the CCG, and representatives from the CCGs and Integrated Care System (ICS) sat on the steering group. This supported SYHA to build links and access healthcare settings. This strategic level engagement and integration was supported by direct communications to healthcare staff. For example, provider staff used information sheets to outline the referral process and the support available for those in the treatment group. The information sheets were also used to answer a series of frequently asked questions including details of eligibility, potential benefits and a diagram explaining the RCT process[footnote 2].

The trial marketing team created webpages and videos targeted at healthcare professionals, providing a general introduction to the trial and how it worked. The use of key facts relating to the welfare benefit, Employment and Support Allowance (ESA), and mental health at work aimed to demonstrate to professionals the importance and local need for the trial. The website also contained short videos of healthcare professionals encouraging their colleagues to refer, making use of peer-to-peer messaging. Messages in these videos included the perception among health professionals that employment is significant for rehabilitation, that the trial could fill gaps in what health services can deliver, and that the trial provided a positive alternative to supplying Fit Notes.

How messages were received by health referrers

Staff felt that GPs were receptive to success case studies for the treatment group although several spoke of challenges in engaging GPs, noting variations between GP practices. Some GPs were reported to have had previous negative experiences of the Fit for Work service[footnote 3] which made them cautious about referring into the trial. Others were reluctant to ‘recommend’ another organisation to patients in case it negatively affected the patient relationship. Delays to trial launch meant some early momentum was lost, and relationships with some GPs were also lost. Some staff perceived that the delays to the launch caused some reputational issues about their delivery capability with healthcare providers.

There was also a lack of understanding about the trial among some healthcare professionals. One healthcare provider explained that at the start of the referral period they did not understand what the trial entailed, which meant they could not fully explain it to their patients and make referrals. Over time, repeated face-to-face contact between the SCR staff and healthcare partners was viewed as valuable by healthcare professionals and enabled them to better understand the trial and the eligibility criteria.

Time pressures in health referrers

Staff reported that it was easier to access receptionists and practice managers than GPs given the pressures on GPs’ time. These time pressures also manifested through limited appointment times with patients, such that GPs were not always able to refer directly during an appointment. The issue of limited time within appointments was not unique to GPs. For example, one healthcare partner identified that time was also limited in their patient appointments, making it challenging to fully introduce and discuss the trial with a potential recruit.

SCR Healthcare partner said:

We only have a 30-minute assessment with a patient and that’s quite a complex assessment. There is a lot that has to be done in that 30 minutes. I think a lot of people within our team really struggled to get a conversation into that 30 minutes that was adequate to inform that patient enough for them to make a decision as to whether that’s a service that they wanted to access or not.

Healthcare partners reported that a lack of time within appointments led them to provide potential recruits with information leaflets about the trial rather than make a direct referral. These would have been recorded as self-referrals at baseline, hence the true number of referrals from health settings is likely to be under-estimated.

Some concerns about the RCT

Some healthcare providers were concerned about the randomised controlled trial (RCT) and were reluctant to refer patients for fear of them being randomised into the control group. Their main concerns centred on patients with mental health issues and low confidence having their hopes raised about additional support, then dashed when randomised into the control group. Allocation to the control group was sometimes viewed by those recruits as rejection, which health partners feared would negatively impact their patients.

SCR healthcare partner said:

One of the main concerns is about the randomised control nature of it… we’re working with patients with depression and anxiety, low confidence, low self-esteem, and when you tell the patients that they might get the intervention or they might not get the intervention, and then they’re being referred through, and people do get their hopes up, and then they’re assessed, and [allocated to the control group]…it is like another rejection…with very vulnerable people…And as a result, the therapists have actually been quite reluctant to refer.

Maintaining health partner relationships was time-consuming

Once health settings were engaged, provider staff found it time-consuming to maintain this engagement, particularly where they were not co-located. This required greater efforts and ongoing engagement to remind GPs of the trial, speak to them about referrals and keep the trial on their agenda. To help combat the issue of time-limited appointments, SCR staff worked with GP practices to staple leaflets about the trial to Fit Notes. Some staff noted that this had worked well because messages were delivered to potential recruits at an appropriate time, and in a way that did not require time from GPs.

Part way through the delivery period a number of additional measures were put in place to help increase referrals from GPs. Staff worked with some GP practices to identify relevant patients from their caseload to be sent a text message introducing the trial and signposting patients to further information. Where this happened, staff felt it was an effective way to generate referrals, particularly in large practices, as GPs lists could identify eligible people without relying on GPs to engage with patients directly. However, some GP practices did not want to undertake this approach because they felt it crossed into marketing rather than patient care.

Provider staff noted examples of co-location in healthcare settings, such as with IAPT teams, and reported that there was an increased likelihood of referrals from these sources. Where co-location happened, SCR staff had closer relationships with healthcare teams and were able to speak to them about the trial and individuals they referred. Another factor which was seen to generate referrals was the IAPT teams’ understanding of IPS and the benefits of employment support more generally. Co-location with healthcare providers, such as physiotherapists, who support people with physical health conditions, was highly variable.

SCR Staff member said:

Physical health has worked brilliantly in some settings… it almost depends on where people feel their capacity is at to engage.

Staff felt that the trial was more successful at integrating and encouraging referrals from IAPT services and less so from musculoskeletal (MSK) services, although there were differences within, not just between, sites. The relative strengths of the links are likely to have affected not only the referral sources of recruits, but also the types of health conditions trial recruits experienced.

Referrals from community organisations and employers

Staff felt that they had built good partnerships with a range of community organisations to encourage referrals, including Jobcentre Plus, training providers, community groups and libraries. In some cases, this was fostered by co-location.

Provider staff worked from a variety of venues, which helped to nurture relationships and maintain continued engagement and referrals throughout the delivery period. Staff felt that where partner organisations understood the trial well, they were able to make relevant and effective referrals because of their existing knowledge about the needs and experiences of the community.

The trial in SCR aimed to build relationships with local employers both to gain access to job vacancies and for employers to refer employees who might need support to the trial. For example, staff worked jointly with one large service sector employer that advertised the trial to their staff, to encourage employees with health issues to self-refer. This included employees managing a health condition while continuing to work, as well as those on sick leave. The employer already offered an Employee Assistance Programme (EAP) and had well-developed line management practices, but felt there would be value to including Working Win as part of their ‘employee offer’ to help them to retain staff. A provider staff member was co-located at the company one day a week to brief potential recruits and meet with treatment group members to deliver support on the company’s premises during the working day. The employer described how they promoted the trial:

SCR employer and delivery partner said:

The agreement between us was that we’ll promote Working Win as part of our toolkit for our employees if you’ll come to site and make it easy for our employees to access you… And obviously we encourage them [employees] to get involved; we did quite a big comms drive about Working Win, and we did that at senior leadership team level, to get buy in and support for HR. And then we took it down to the office and managers and the team mangers were the people that we wanted to reach to.

Self-referrals

Self-referrals were the largest source of referrals, although it was not always possible to accurately determine where self-referrers first heard about the trial. The marketing campaign targeting potential referrals from the general public included adverts on buses and bus shelters, as well as local radio and TV, to encourage self-referrals via the website. The website also presented information about how employment can benefit mental and physical health, including case studies from recruits. Provider staff also attended job fairs and handed out leaflets in supermarkets to try to generate community awareness. This enabled the trial to access recruits who might otherwise have been missed, including people not already in contact with healthcare services or community organisations. However, staff reflected that it was challenging to communicate the RCT effectively through a poster/website campaign, which then affected recruits’ understanding of the trial. The general view was that the RCT needed to be explained in person for people to fully comprehend the offer.

1.2.2. Referral processes

There were two referral processes in SCR. Referrals from individuals or referring organisations, including self-referrals, were accepted via the website. Primary care services could also refer people directly using the EMIS system, the most widely used clinical record system for primary care in the UK. This process was designed to be as light-touch as possible to encourage referrals, especially by GPs and clinicians who had limited time. Staff believed that this helped with generating referrals. The online referral form for individuals and third sector organisations was designed to take around one minute to complete. There was consensus amongst staff that the referral process worked well and contributed positively to the number of referrals.

SCR staff member said:

What’s really helped is investing in our technology, our referral website, trying to keep the amount of information on that referral website to what we needed to know rather than everything we could possibly be interested to know to try and minimise the burden on people self-referring themselves or referrers signposting, referring in their patients.

One drawback, however, was that its ease and simplicity resulted in some inappropriate referrals, both from community organisations and through self-referrals. When staff followed up on referrals, they found some individuals did not want to work, and others were people with high English language needs who staff felt, despite the accommodations they might make in translating documents and ensuring they had someone to support them during the initial appointment, would not be able to participate fully without language support, which was not available for service delivery under the contract. This practice was in accordance with the process approved by HRA.

Because of the different ways in which people both found out about and were referred to the trial, there was significant variation in how the trial was understood among potential recruits. This varied understanding meant that staff needed to offer an initial phone call to discuss the trial and confirm interest and suitability prior to the initial appointment. Whether recruits had referred themselves or had been referred by others impacted on their engagement and motivation to join the trial. Staff felt self-referrals were more likely than those referred by others to be motivated to engage.

1.2.3. Reasons recruits engaged

The main reasons recruits – people who agreed to randomisation - reported joining the trial were a desire to re-enter the workforce and/or a need for support managing their health condition. Their priority in joining depended on their health and employment situation, and the information they had about the trial prior to the initial appointment. The eligibility which included people who were in employment (SCR IW) and those who were not (SCR OOW) meant reasons for engaging also varied between these groups.

Some of the OOW recruits engaged because they wanted support to manage their health condition(s); others joined to gain support to find work. The SCR IW group included some people who wanted support in managing a difficult situation in their current employment, whereas others sought help to understand their career options with a view to changing jobs. Some recruits believed the trial only offered employment support; others thought it primarily offered health support.

Recruits’ understanding of the trial fed through into their expectations and motivations. As such, some were motivated by the opportunity to receive health support, and others primarily focused on the chance to receive employment and job search support.

SCR OW treatment group said:

Well, at first, I thought it was about, you know, about my health, I thought it was about me getting help so when I went down to see, you know, the job worker it was about jobs and it was to do about my health as well.

SCR IW treatment group said:

Well, I was applying for all these jobs and really not getting anywhere and because of that, I thought my confidence was getting knocked. I thought it was me and I thought I was doing something wrong. I couldn’t understand why I wasn’t getting anywhere

Recall of information about the trial varied

The information that recruits could recall from the point of referral was very varied. Some had inaccurate views of the trial, such as one who was motivated to take part because they understood the trial to offer a befriending role. Some had an accurate but incomplete perception, while others had a very detailed understanding of the trial, positively impacting their motivations to engage.

SCR control group said:

To me it was an absolute no brainer, this is what people in my position need, somebody to actually help them to do what they want to do…and have the support ongoing as well over a long period of time…as well as the joined up thinking between the different organisations, contact with the CAB and the DWP and employers and everything.

Several recruits expected more support with job search. IPS is designed to support people with sourcing ‘hidden’ jobs – those which are not advertised online or on public jobs boards – alongside regular job search activities. However, some recruits were either unaware or did not seem to understand that this was something IPS could support them with.

SCR OOW treatment group said:

When I eventually did a couple of sessions it was quite clear that you were just… all you were doing was what you could do yourself, look on the internet and look for jobs. There were no insider deals or anything like that. They didn’t know…They couldn’t find jobs that we couldn’t.

Core to the IPS ‘place then train’ model is a focus on finding a job quickly and then continuing to provide support for people in their new role. As such, IPS recipients are encouraged to commence job search activities soon after starting to receive IPS support. Staff felt that this message was not impressed strongly enough during awareness raising and recruitment, which meant that some recruits were not necessarily ready for work in the short term, and thereby inappropriate for the trial.

SCR staff member (focus group) said:

Because some of our customers might have had a background from sickness benefits of ten years, they’ve had no interactions of job search with the Jobcentres of this world, so they’re coming absolutely raw. What their perception of the trial probably was, was about helping them around their health first and then get a job

Recruits who were not working, particularly those receiving benefits with conditionality, were not always clear that engagement was voluntary. Several recruits had been mandated to employment programmes before or were being supported by Jobcentre Plus and were concerned that the terms of engagement would be similar on the trial. For example, they thought they would be required to take any job offer. The culture of the referring organisation and the ways it engaged with recruits affected perceptions of the trial. Some recruits felt pressure to join the trial because of their benefits claim with Jobcentre Plus. In contrast, others believed they would not be pressurised to find work because they had been referred by an IAPT team.

SCR recruit said:

I just felt it was another hoop I had got to jump through for the DWP… I just thought I would try it because at least then if I wasn’t coming up with interviews for jobs, it was the DWP’s view when I went to sign on that I was with Working Win and they might leave me alone.

SCR recruit said:

So knowing that it’s been recommended from an IAPT team and that people would have more of an understanding regarding mental health, I just thought at least I’m going to be dealing with people that weren’t going to be pressuring me [to find work].

In-work recruits tended to have a different set of expectations and motivations for engaging with the trial than out-of-work recruits. These motivations included wanting support managing work situations or changing job roles. Some in-work recruits expressly reported that the confidentiality of the trial was important because they did not want their employer to know they were accessing support.

SCR recruit said:

I wanted somebody there that would help me, because it got to a point with work where I was going to quit… because I couldn’t cope, because I had a lot going on at home…And she sort of gave me that boost to say ‘no, come on, you need to do it. If you don’t like it, let’s have a look at what other options you’ve got’.

1.2.4. Views and experiences of the initial meeting

Waiting times and location

Nearly all of the recruits interviewed reported being contacted by a member of provider staff soon after their referral. Typically, this was less than two weeks and, in some cases, just a few days. Recruits felt that this amount of time was reasonable and felt they were engaged in a timely manner. Staff believed that arranging appointments quickly after a referral and holding subsequent ongoing support appointments as soon as possible was key to engagement. This was enabled by staff having sufficient capacity in their caseload to arrange and hold appointments:

SCR staff member said:

We know if we got customers in quicker they’re more likely to engage…We’ve been able to capitalise on the staffing numbers that we’ve had and get people actively going out and promoting the trial and talking to referrers and then being able to contact customers really quickly but also being able to see them really quickly as well.

Initial meetings were held in a variety of locations based on staff and recruits’ availability and preferences. Staff spoke of the importance of meeting people in places where they felt comfortable and which were convenient. These spaces included cafés as well as organisations where provider staff were co-located. In SCR, towards the latter part of the trial, staff were also able to offer initial appointments via Skype which better suited the needs of some recruits. Generally, recruits welcomed the choice and flexibility staff demonstrated in agreeing where to meet, although some, with hindsight, did not like responding to the baseline data collection and discussing personal and sensitive issues in an open space:

SCR recruit said:

It was a bit awkward because where we had it wasn’t private… it was in a big area where people were waiting to be seen and they just went into cubicles, so everybody could hear.

Understanding it was an RCT

Staff were aware that referral partners had limited time to explain the trial to potential recruits, and there were also limitations in the information that publicity materials such as posters could convey. This meant that recruits did not always know at the point of referral that the trial was an RCT and not a service. Staff noted the importance of providing clear information about the trial and what people could expect, in order to secure engagement. When an initial appointment was made, staff included the information sheet and materials explaining the trial as part of an email confirming the appointment. This meant potential recruits could read and digest this information before the initial meeting. In addition, staff tended to call recruits before their initial appointment to introduce themselves, discuss the trial and confirm the meeting:

SCR staff member said:

I always give them a courtesy call just to introduce myself, so they’ve always spoken to me. I confirm where we’re meeting that it’s going to be suitable for them…and usually just have a little chat while they’re on the phone so I actually know all that connection there’s a rapport starting up before that first meeting.

However, several recruits who had been allocated to the control group, said they had not understood that it was a trial rather than a service at the point at which they joined, which was a source of disappointment. Other recruits allocated to the control group remained unclear about their role on the trial when interviewed and believed that the member of staff would be in touch again to offer support. Others thought they were not eligible for the support based on their answers to questions at the initial meeting. However, some recruits allocated to the control group were able to clearly explain the process and result.

Baseline data collection and the randomisation process

The randomisation process included the collection of baseline information on characteristics, health and wellbeing, individual circumstances and barriers to employment. Several staff believed this was in conflict with the IPS strength-based approach which characterised on-going support appointments, but recruits did not particularly set out concerns.

Generally, recruits allocated to the treatment group found the randomisation process and initial meeting to be satisfactory, with information clearly explained:

SCR In-work treatment group said:

So everything was explained on that first session but explained at a good pace and they said even if we need to take two sessions to do this explanation we will do because obviously they wanted me to understand what I was getting into and what the pilot was for as well.

Disappointment at being allocated to the control group was expressed by several control group recruits and even where they understood that allocation was random, they felt dejected. For example, one recruit described being given a piece of paper with information of other services but said that she did not want to contact them and felt “very lost”. Some staff found the process of allocating recruits into the control group challenging, because they found it difficult to not support people whom they believed could benefit from being part of the treatment group.

To address this, part way through the delivery period the staffing structure was changed to have a member of the team dedicated to completing the initial appointment and randomisation process. Where this happened, the treatment group experienced a change in employment specialist between the initial appointment and further meetings. Some staff reported liking the new structure, both as it removed the RCT appointments for those who found them hardest, and made balancing different aspects of the job role easier. However, having tested this approach the trial reverted back to consistency between the employment specialists undertaking the initial appointment and on-going support for the treatment group, as this made caseload management easier and improved continuity for those receiving support.

1.3. Delivery of support

This section explores the support provided to the treatment group in SCR. The views and experiences of staff and the treatment group are explored in relation to caseload management, the types of support offered, the relationship between staff and the treatment group, as well as employer engagement and job brokerage. It considers the support offered in relation to the key elements of IPS and explores whether the experience of delivering and receiving support was different for those who are working and those who are not and for people with mental and physical health conditions.

1.3.1. Caseload management

Caseloads varied

Employment specialists had target caseloads of 30, in line with IPS models. However, they reported a wide variation, with 15 to 20 at the start and end of the trial, and peaks above 30 in the middle stages. Some reported caseloads significantly above target, in the mid-40s. This was mainly due to variations in both staff and recruitment. Employment specialists with higher caseloads reported finding their workload difficult to manage, making it challenging to fully implement IPS.

SCR staff member said:

I kind of feel as though following the IPS model I think to engage with 35 customers I think is quite challenging…in terms of meeting targets, meeting customers I don’t feel as though it’s enough time.

Some staff also reported that managing a high caseload was affecting their own work-life balance and was a source of stress and anxiety.

SCR staff member said:

Which… I mean it’s nice to support more people but it’s also quite stressful because I sometimes worry that the quality of service that I can provide people will be compromised because I have less time to prep.

Managers allocated those allocated to IPS support to staff based on their availability, their location and their referring organisation. However, sometimes it was not possible to keep within a geographical location, placing additional strains on staff time management. This was a particular issue in one local area in this site where at one stage referrals were made from Sheffield due to challenges in recruiting locally.

Flexibility was important

Staff were keen to meet flexibly with those receiving IPS and this could also create a challenge in terms of planning contact. As caseloads increased, some staff reported moving to a more structured approach and becoming more effective in caseload management.

SCR staff member said:

When I started the job, I’d just meet people whenever could suit them. Now I block certain days out for certain areas of the city and I’ll only offer them an appointment on that day.

Some staff found it particularly challenging to manage mixed IW and OOW client lists, where working people receiving IPS support required evening and weekend meetings while those who were not in employment could prefer daytime meetings.

COVID-19 placed constraints on operation

Before the move to remote support in March 2020 outreach was a significant feature, with appointments held close to people’s homes. While some support was delivered remotely prior to the COVID-19 lockdown, it was normally offered in addition to face-to-face support, often for shorter catch-ups. The effects of the pandemic on delivery are fully explored in the report in this series covering the pandemic and the trial.

High levels of engagement

Staff reported a high level of engagement from those in the treatment group – referring to the uptake of support and meetings[footnote 4], which generally only dropped on return to work or due to worsening health. Contact was most often fortnightly. However, contact was sometimes less frequent, particularly as the SCR IW group who were working or once the SCR OOW had started a job. Contact in these cases was sometimes only by phone, email or text message rather than face-to-face.

Those receiving IPS support were generally very satisfied with the regularity of contact with their employment specialists. They also reported regular contact between meetings by email, text or telephone with nearly all saying they felt staff were responsive to their needs. Contact was generally fortnightly, though this varied between weekly and monthly dependent on individual needs. Contact was also often different for those who were working and those who were not, with those who were working sometimes receiving less frequent support due to the demands of work. Frequency also often varied over time with more meetings at first or at critical times.

SCR treatment group said:

So, when things were quite bad it was weekly and then we dropped it down to fortnightly and then down almost to monthly, or just telephone calls, I think.

However, some people in the treatment group felt that contact was not frequent enough as it meant progress was too slow. This was more commonly cited by those who reported monthly meetings but also included some who met fortnightly.

The only significant issue reported by treatment group members in relation to case management was when there was a change in employment specialist. While handover was generally smooth, a small number reported sustained interruptions in their support with an unexplained loss of contact – either temporary or permanent. In cases where the handover was clearly explained and well managed, they did not feel their support was disrupted.

1.3.2. Types of support provided

Following on from initial appointments, provider staff completed a vocational profile with the treatment group. This involved capturing information to identify individual strengths and previous experience, so they could create an action plan of support.

Specialists offered employment support such as: supporting CV development, discussing career goals and identifying skills, help to search and apply for jobs, advice about interview techniques, and advice about declaring health conditions and/or disabilities at work and accessing reasonable adjustments. Health and wellbeing support included: ongoing advice and support about work and health issues, challenging the treatment group about what was possible with their condition, and support to negotiate a better relationship with their GP. This could include encouragement from employment specialists for individuals to ask their GP for help with changing medication, or more generally to ask their GP questions so they could get the help they needed.

SCR treatment group said:

I’m aware of different opportunities and I’m more aware of what employers are looking for. I think when I first met [employment specialist] I had a very fixed opinion of what employers were looking for… I think I was a little bit behind the times. I was locked in a time when people didn’t talk about health regarding work, you just kind of soldiered on regardless, you know

People in the treatment group also reported tailored support such as helping with homelessness, anger management techniques, accessing funding for interview clothes, and support using social media to promote self-employment.

From a research perspective, it was often difficult to isolate differences in support for physical and mental health conditions because many people with physical conditions also reported having depression, stress or anxiety. However, while mentoring and confidence building was important for everyone, those with physical conditions sometimes had more specific needs. For example, someone who had epilepsy needed help getting their driving licence back, while someone with a musculoskeletal condition needed physical adjustments at work such as a seated rather than standing role.

It is also important to note that some receiving IPS support found it difficult to recall and/or discuss the kinds of support they were receiving due to their own health conditions or disabilities that affected memory, concentration or communication. It is therefore challenging to build a full understanding of the experience of all those interviewed. This was also the case with one who spoke English as an additional language. Staff identified that they sometimes found it difficult to support members of the treatment group with language needs; however, other communication challenges were not raised. A staff member reported that the contract allowed them to commission interpreters for the initial meeting but not for the support experience and that some people had been recruited when their language needs meant delivering support was not possible. This suggests those leading the recruitment process had not been effective in assessing ability to engage in support in all cases.

More broadly, staff consistently reported following IPS principles and rapidly progressing the treatment group towards work. This was reflected in the interviews, where many members of the treatment group described action planning focused on their individual circumstances and a rapid move to targeted job search.

SCR staff member said:

From the first appointment we’d get their CV… all updated, all online if possible and then the next session after that we’ll just start applying for jobs, so it’s pretty much go from the beginning.

Where people were not moved towards job searching quickly, it was primarily due to having high needs and not yet being ready for employment. In line with this, a significant minority of the treatment group described themselves as not being ready to work, either from their perspective or from that of other professionals in their life, including their doctors. One identified that the support provided did not cater for her complex needs, again suggesting that some people were accepted onto the trial whose needs were not well aligned with the eligibility criteria (which focused on mild to moderate conditions).

SCR treatment group said:

I wasn’t sure what kind of support she was offering because I know that my support needs at work… it is not just that I need a different kind of chair to sit on, you know, or I can’t climb stairs. It is emotionally and physically… there are all sorts of things that employers in the past have refused, they just won’t budge, you can either do the job or you can’t.

Much of the employment support reported by staff and the treatment group was based around basic job search and application activities. This clearly met the needs of many; however, this was quite different to the aims of IPS in respect of sourcing ‘hidden’ jobs. Some staff saw their role as developing these basic job search skills as support for the long term, rather than carrying out job search activity on their behalf. They felt this would better equip the treatment group to find work after finishing the time-limited IPS support.

SCR staff member said:

I had a guy who had not worked for 16 years and he’d not got a CV. In the first three meetings it was literally talking about how to go and apply for a job and doing a CV and taking it step by step …. He’s now learned that technique. What we’re trying to do is empowering people. We’re giving them the skills even if they don’t get a job in the nine months, they’re with us they’ve got the skills to go forward and that will help them in the future.

However, there was some evidence that recruits in the treatment group with more established work histories felt that this basic level of employment support was limited and did not meet their needs.

SCR treatment group said:

I was getting no practical support. I was just being told, “You’re doing everything you can, you’re doing all the right stuff, I’m just not quite sure what’s happening. Just keep on doing what you’re doing, you’ll get something in the end.

People in the treatment group generally felt that they were being advised to get the right kind of job for them and placed a high value on this, often contrasting this to the approach of Jobcentre Plus staff. However, staff identified that supporting them to get the right job for them could be challenging when there was a mismatch between career ambitions or experience and a health condition or disability. Part of the support provided was to navigate this.

SCR treatment group said:

I felt a connection there in terms of somebody trying to help to not just get me a job but get me a job that I felt comfortable with.

SCR staff member said:

The individuals themselves don’t realise that perhaps although they are already in a job, that job isn’t going to be suitable for them in the future and they might need to readjust their career paths as well so sometimes that can be quite difficult for them to deal with because they have been continually in work and then all of a sudden they have a health condition that means they can’t go back into that type of work and that is all they have ever known.

There was a perception amongst some staff that the trial was better suited to support people who were not working as opposed to those in work, although this is not borne out in the wider evaluation data. These staff identified that some expectations for IPS such as rapid job search were not necessarily well aligned to the needs of people in the SCR IW group who were already working on joining the trial. This view was shared by some in the SCR IW treatment group who felt that the initial stages of the trial was not tailored to their needs. Again, this latter point was not supported in the surveys where the SCR IW group demonstrated some of the highest levels of satisfaction.

SCR staff member said:

I feel like maybe IPS is more aligned to out-of-work support than in-work support, perhaps. But it still is IPS in the fact that we engage with their employer and we try and become a middleman almost between the employer and the customer.

Mentoring or coaching was identified as the most significant element of support by many in the treatment group and staff. This applied to helping them achieve employment, health and wellbeing outcomes. Staff also saw this as a core component in a strength building approach to help them identify their strengths and develop their confidence.

SCR staff member said:

I think it is for the person to recognise their own strengths. Because no matter how good a CV is, or how good a covering letter is, or what job you apply for if you don’t feel your self-worth and you attend that interview and you can’t project that and you have never heard anybody tell you how well you are already doing, and the skills you need to be sharing with people you won’t pass that hurdle.

Some in the treatment group were able to articulate this approach as strength building, mentoring, or career counselling, while others focused on the value of having someone to talk to. Some felt this was likely to extend beyond the aims of the service, though using it in this way was helpful as other employment providers (such as Jobcentre Plus and other providers of employment services) were less responsive to their needs. This support to build confidence was often highly effective with those who reported low level mental health issues.

SCR treatment group said:

I’ve been using Working Win for more than really I should be using it for because I’m using it from a kind of counselling perspective but they’re not really counsellors. That’s because I get more response out of them than I do other providers.

However, others with higher needs felt that while this friendly approach was supportive, it did not help them with the systemic barriers they faced. Some who were dissatisfied felt that the support they received was too focused on mentoring and conversation rather than action such as referrals to health support services.

Health support often seemed secondary to employment support apart from the mentoring. Some in the treatment group, particularly those with physical conditions, believed the trial was concerned with their health only where it directly impacted on work. This was sometimes because they did not feel they needed health support rather than because it was not available.

SCR recruit said:

It’s mainly to do with work because that’s been the issue that I’ve had. The day to day management of the health is really more the doctor’s part, rather than her advice.

Support for those in the treatment group who were working often appeared more focused on health as they needed support managing their condition at work, while those who were out-of-work were focused on job search. Some staff also felt that it was easier to achieve positive outcomes for those who were working as they already had a connection to an employer and only needed limited intervention.

SCR staff member said:

In terms of keeping people in work to get the outcome of three months and job return can be easier as well because it can be that they just need a conversation to get things off their chest, you can do a wellness action plan and they can return to work within two weeks.

For SCR IW and OOW trial groups, some described receiving very useful support on managing their condition. However, others found the focus to be solely on employment and felt that they would have welcomed more discussion and support with their health. In addition, some staff were less confident in discussing and understanding health and disability as they felt they lacked knowledge on this and would have welcomed further training. This was particularly true for staff who had a background in employment support, rather than a focus on health and wellbeing. Some in the treatment group could, however, be referred to a health and wellbeing specialist within the service for additional support.

1.3.3. The advisory relationship

The positive relationships between staff and the treatment group were key to successful support, with many in the treatment group seeing this relationship as the most valuable part of the support they received. Relationships were seen as positive where people felt understood and supported. It was also seen as important that their specialist had a flexible, tailored approach that was responsive to their needs.

SCR treatment group said:

It’s mentoring and support from somebody who had an understanding of what it was actually really like to have health issues, physical or mental, and from a person who’s actually sympathetic to those issues as well.

SCR treatment group said:

She also has a very individualised approach as well because she often sends things that she says to me, “I saw this and thought of you”.

Some in the treatment group felt that it was important that their specialist had a good understanding of their specific health condition. This could be because they came from a health background or because they had personal experience of an issue.

SCR treatment group said:

Also, my Working Win advisor was previously a nurse so she could comment a little bit on the medical issues that I was having and maybe some advice into that as well, because I was still receiving treatment for the cellulitis and lymphoedema.

Staff felt confident that they were able to maintain positive relationships with those receiving IPS support. They said that they needed to understand their situations and respond to them on an individual basis to foster this positivity. The vocational profiling and the strengths-based approach they adopted was seen as an important part of this.

SCR staff member said:

There are challenges, you know, in keeping people engaged and motivated and keeping that hope alive but, you know, that is why some of the training that is offered to staff in terms of motivational interviewing, self-based approaches and sharing stories with customers about other customers’ outcomes.

One staff member identified that personality was also important, identifying some cases where in the treatment group were moved to a new specialist if they ‘didn’t click’. Beyond this staff did not discuss where relationships broke down; if someone stopped engaging in the trial it was generally attributed to their own circumstances such as worsening health. This was reflected in some of the treatment group interviews where an event such as an accident or a behaviour such as anger issues could be seen to impact on their relationship with their employment specialist.

Nearly all members of the treatment group taking part in interviews were very positive about their relationship with their employment specialist even where they may have been more critical of other parts of the support. In the very few cases where issues were identified, some believed their employment specialist was not proactive enough or did not have the relevant experience to understand their situation. In other cases, issues were due to a range of individual factors, for example one who had unspecified support needs reported a lack of understanding on both sides.

Consistency of support was important for many. Those in the treatment group who stayed with the same specialist saw this as an important part of their experience. When they were moved to a new specialist, the treatment group sometimes expressed anxiety and frustration at having to build a trusting relationship again. However, most who were moved to a new employment specialist managed to foster a good relationship, with some feeling that the second relationship was better. Some staff also commented that a lack of information in the handover process meant it could be more challenging to build relationships with those they took on mid-trial.

SCR treatment group said:

You know, you get to know each other, and you get this trust between each other as well, that’s very important, you know, being able to trust and understand each other.

1.3.4. Delivery partners

Staff worked with a range of national and local partners across SCR. Case conferencing was not evident to any real extent in the qualitative research. This was acknowledged by staff as perhaps the most significant variation from IPS and its fidelity scale. This was partly due to issues with co-locating due to a lack of physical space and infrastructure as well as the time it took to establish effective partnerships. Where staff described successful interactions with clinicians, co-location was seen as an essential tool in building relationships. Not all staff put the same emphasis on partnership working, and there were some indications that some preferred referring to in-house resources which included specialists such as wellbeing coaches and established, longstanding partners such as Citizens Advice Bureau (CAB).

Two of the most significant partnerships were intended to be with GPs and IAPT providers. While some in the treatment group described how the service helped them improve their relationship with their GP, this did not involve direct intervention or case conferencing in the qualitative sample. The relationship with IAPT providers was one of the most significant partnerships, with referrals in both directions. The only issue raised other than the challenge of co-location was that the those in the treatment group tended only to receive short-term IAPT support. This meant it was difficult for staff to fully engage with therapists in the way expected by IPS.

Staff also co-located in local community organisations such as employment support or health charities. The challenge of finding space within these organisations to hold these meetings was again identified, as well as the additional challenge of the trial as being seen as competition. One staff member described investing considerable time in building friendly relationships.

SCR staff member said:

So, I kind of worked with that and made sure that they were informed, and I made sure I referred into their services…I attended the services. I went to the running groups. I went to the cooking groups, the exercise classes. Like I was kind of just making myself part of the team.

Co-location in workplaces was seen as positive where it was in place and in one case contributed to a change in workplace culture. Through support gained through Working Win a person in the treatment group reported how their employer had embedded a strategy focused on health and wellbeing and ensured Wellness Action Plans were in place.

SCR treatment group said:

I mean the other positive thing is the wellness action plan has triggered changes at work which should have happened months and months ago but now they’ve put out a document saying that employee wellbeing is priority for this year…all that’s happened as a result of that action plan and me being ill. So it’s all good. It’s all gone in the right direction.

However, few of the treatment group reported meeting in their workplace. For some, this carried a risk of disclosure and concerns about confidentiality.

Being based in the community was welcomed by those in the treatment group, with many appreciating the convenience and the opportunity to leave the house. These meetings most commonly took place in cafes and libraries, rather than in community organisations themselves. However, where some expressed concerns with the location of meetings, they cited a lack of privacy to discuss what they felt were sensitive issues.

Beyond co-location, provider staff referred the treatment group to a range of different services and most regularly to CAB for support with debt or benefit claims. Other referrals varied significantly by individual with some referred to a wide range of services. These included referrals to counselling and therapy services, leisure centres, gardening or writing groups, and self-employment business support.

Most of the treatment group taking part in interviews who had been referred to external services were positive about the value this added, saying that these referrals had helped them address difficult issues in their lives such as how to manage their finances. For one member of the treatment group the referrals made by her specialist were a catalyst for significant changes to her wellbeing.

SCR treatment group said:

Because I literally couldn’t get anyone to help me [before the referral], I was just constantly beating my head against a brick wall.

A high number of the treatment group in qualitative interviews were receiving therapy or counselling, although this often pre-dated their time on the trial. For some, therapy was the most significant support they received, while for others their employment specialist was more important and the IPS employment support was seen as a better fit to their needs. Where they were unhappy with their referral to external services, it was generally because a referral had been made that was not followed up, or that was not suitable. The qualitative data suggested that these were often those in the treatment group with the highest level of need.

SCR treatment group said:

She’s offered me loads of things but nothing ever come about so she offered me a chiropractor appointment, she offered me a gym like a 12 week gym membership but at the time I did go and I spoke to the guy at the gym, but I was so ill or felt so ill that I no longer do a 20 minute walk and he basically said I can’t do ought for you basically because you can’t do anything without hurting so I said well no it doesn’t make a lot of sense to me really I don’t really know why so I kind of postponed that and I’ve tried to contact him since and nobody rings me back about that either.

1.3.5. Employer engagement and job brokerage

Employer engagement and job brokerage is another core aspect of the IPS service. There was a recognition from staff at all levels that this was not delivered frequently enough and they were not always able to follow IPS principles. In recognition of the challenges of employer engagement, a specialist member of staff was appointed to focus on this role. However, staff and managers felt that employer engagement became more of a focus once the recruitment and referral stage of the trial had finished giving them more time to dedicate to this aspect of delivery. Because of these factors, measures such as a central jobs website and other employment engagement activities were only introduced from October 2019.

Staff identified several barriers to employer engagement with many believing the IPS weekly target of six face-to-face interactions was too challenging, Firstly, staff felt that the fidelity model did not necessarily reflect working culture in England and that many employers were too busy to engage.

SCR staff member said:

[The treatment group] wanted to approach employers themselves or apply to jobs themselves and I think with the model being an American model, I think in America are probably more set to that sort of thing, and they are a bit more on the ball with it. I think, I hate to say this, but British employers can be a bit more dismissive of helping people and you are dealing with people, an individual manager’s perception of somebody’s health condition.

Some staff, typically those from a health background, found employer engagement difficult. Staff who had previously worked in employment support were more confident in engaging with employers and described a wider range of networking strategies. However, the most significant barrier to employer engagement was a lack of time; when caseloads were high, staff were not able to prioritise this part of their role. Nonetheless, some in the treatment group provided examples of employer engagement leading to them finding work; - an approach which was highly valued where it had been successful.

SCR treatment group said:

He said I’ll get cracking with getting in contact with some companies. It just happened the way it happened. The first company he rang to ask what qualifications I needed and what experience they were looking for, they said they wanted to see my CV. He sent it through and that’s who I got the job with.

However, others felt that their specialist did not support them enough through employer engagement, instead sourcing jobs from internet searches only. They were disappointed when they did not receive direct referrals to work that suited their needs.

Evidence of job brokerage beyond the recruitment stage was limited for those in the OOW treatment group. A significant barrier was that many either did not want to disclose their conditions to potential or current employers or did not want their specialist to directly intervene. However, they generally reported that they were supported to raise issues themselves and advised on discussing their rights.

SCR treatment group said:

We’ve talked about the Equalities Act… She explained my rights. She advised me to… because she’s always empowered me to do it myself and I am a person to do things myself, like to contact ACAS and get my rights, contact work. She would go with me and if I wanted her at any point, she would attend meetings, she would do the meetings without me there.

While evidence of job brokerage was limited, there were a small number of good examples, including an example of a treatment group member being recruited to work for the trial. The trial provider was supportive in adjusting hours to better suit the individual and provided additional training to support the individual in aspects of the role they were less confident with. Additionally, colleagues were so supportive that the individual concerned reported that they ‘feel like I have six work coaches’.