Embedding a Culture and Heritage Capital Approach

Published 17 December 2024

Applies to England

Authors: Harman Sagger and Matthew Bezzano

Published: December 2024

Acknowledgements

The Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) is working closely with partners, including Historic England, Arts Council England, the British Film Institute and many others to develop this paper. This document has been endorsed by the Culture and Heritage Capital Advisory Board with the following membership:

| Name | Organisation |

|---|---|

| Lord Mendoza (Chair) | Chairman, Historic England |

| Prof Hasan Bakhshi, MBE | Director of the Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre |

| Prof Ian Bateman, OBE | Professor, University of Exeter Business School |

| Prof May Cassar, CBE | Founding Director, UCL Institute for Sustainable Heritage |

| Prof Geoffrey Crossick | Professor, School of Advanced Study, University of London |

| Darren Henley, OBE | Chief Executive, Arts Council England |

| Sir Laurie Magnus | Chair, Heritage of London Trust |

| Eilish McGuinness | Chief Executive, National Lottery Heritage Fund |

| Prof Susana Mourato | Professor, LSE, Department for Geography and the Environment |

| René Olivieri, CBE | Chair of the National Trust |

| Jessica Pulay, CBE | Chair, Wallace Collection |

| Prof Christopher Smith | Executive Chair of the Arts and Humanities Research Council |

| Prof David Throsby, AO | Professor, Macquarie University, Department of Economics |

| Duncan Wilson, CBE, OBE | Chief Executive, Historic England |

This paper has sought guidance and feedback from leading experts with particular thanks to:

-

Arts Council England (Andrew Mowlah)

-

DCMS Colleagues (Anya Harvey, Dave O’Brien, Krishea Aswani)

-

DEFRA (Colin Smith, Matthew Bardrick)

-

Forestry England (Lawrence Shaw)

-

Historic England (Adala Leeson, Thomas Colwill)

-

IPSOS (Dr. Ricky Lawton)

-

National Trust (Callum Reilly, Dr. Hannah Fluck, Rebecca Clark, Tom Dommet)

-

The Audience Agency (Patrick Towell)

-

University of Exeter (Aditi Samant Singar, Dr. Amy Binner, Dr. Ethan Addicott, Tatiana Cantillo)

1. Executive Summary

‘Embedding a Culture and Heritage Capital Approach’ provides an update to ‘Valuing Culture and Heritage Capital: A framework towards informing decision making’, published by DCMS in January 2021.[footnote 1]

The overall ambition of the Culture and Heritage Capital Programme

The creative, cultural and heritage sectors shape our cities, towns and villages, foster vibrant communities, and strengthen the fabric of our national identity. Alongside their acknowledged contribution to economic growth, the creative, cultural and heritage sectors improve wellbeing, happiness, and create long-lasting impacts on our quality of life.

However, the creative, culture and heritage sectors are some of the few sectors that do not have sector specific guidance on valuing their impact. This is why ‘Valuing Culture and Heritage Capital: A framework towards informing decision making’ set out the need for DCMS sectors to have similar guidance as the environmental, health and transport sectors, allowing transformational change to assessing value for money, which is a fundamental part of the decision making process in public policy.

DCMS launched the Culture and Heritage Capital (CHC) Programme in 2021 with our arms length bodies (ALBs). The aim is to ensure the economic, social and cultural value is included in appraisals and evaluation, following best practice guidance set out by HM Treasury’s Green Book. Without an agreed method for valuing the flow of services that CHC assets provide, the impact of proposals on specific groups, households, communities and businesses is underestimated, particularly during social cost benefit analysis (SCBA).

Therefore, at the heart of the CHC programme is the need for economic analysis across the creative, culture and heritage sectors to more comprehensively value their impact on sustainable growth and long-term standards of living. This means articulating and informing decisions based on the economic, social and cultural contribution the sectors make to society. This involves, for example, considering the Creative Industries’ £124.6 billion contribution to the economy alongside the £29 billion per annum wellbeing value of residing near heritage assets,[footnote 2][footnote 3] and the distributional impact of proposals on specific groups, households, communities and businesses.

The CHC programme aligns with the Office of National Statistics and United Nations work on moving ‘Beyond GDP’.[footnote 4] This is a holistic view on how society is doing, beyond purely economic measures, to ensure decisions fully account for their impact on society and the natural environment.

Our ambition is for CHC to enable different disciplines to adopt a shared framework and understanding in terms of practical applications and future research. However, we also recognise that CHC is a conceptual approach that may not be relevant for all purposes, and the language used may not always resonate with all groups. This means valuation of cost and benefits through SCBA should always be conducted proportionally, and sit alongside a wider set of evidence that can inform decision making.

The aims of the Programme are to:

-

enable the culture and heritage sector to articulate its value to society more comprehensively, and therefore make more effective decisions

-

help other sectors, such as transport and housing, measure the impact their interventions may have on culture and heritage

-

help private organisations make better informed decisions about their own culture and heritage assets, and/or decisions that affect culture and heritage capital and service flows in the local area

Evidence of economic values developed through the programme should be used in SCBA to enable culture and heritage organisations to demonstrate their full value to society.

Key outputs of the Programme are:

-

supplementary guidance to the HM Treasury Green Book, complete with a toolkit of evidence, similar to the Enabling a Natural Capital Approach (ENCA) toolkit

-

Culture and Heritage Capital accounts that show annual flows from these assets, providing a clearer picture of their value to the economy and society

-

sector-specific tools that will help organisations across different fields, including transport, housing, and private enterprises, understand how their actions affect culture and heritage

The role of CHC alongside other decision making processes and disciplines.

Social cost-benefit analysis (SCBA) plays an integral part in informing public funding decisions by aiming to place costs and benefits in the same ‘unit of account’, meaning pounds and pence, to enable them to be compared on an equivalent basis. This is particularly important to understand the value for money to the public when making an investment case that requires a complete valuation of costs and benefits.

However, the CHC approach should not replace, for example, existing artistic decisions but should be an additional tool to allow for improved articulation and understanding of the value of culture and heritage in decision-making. Where it is not possible to monetise certain costs or benefits they should be recorded and presented as part of the appraisal. Therefore qualitative research and expert opinion are important and play a role in making the case for investment and can provide more robust appraisals and evaluations, where SCBA can not capture the full cost and benefits to inform decision making.[footnote 5]

Although the CHC approach is economic-led, it is multidisciplinary and similar to the approach taken by Natural Capital. CHC aims to present values for benefits and disbenefits in monetary units for comparability but it must be informed by other disciplines, for example, arts and humanities, social science, and physical and environmental sciences, particularly where monetisation and/or quantification is not possible. Arts and humanities will play an important role in our understanding why people value and therefore the values derived from economic valuation techniques. This is why in October 2023 the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and DCMS announced £3.1 million in funding for a programme of six multidisciplinary projects that included academics and researchers from social science, arts and humanities and heritage sciences.[footnote 6]

What sectors are in scope and who will benefit from from this publication

The cultural, creative and heritage sectors make up a set of interrelated sectors that together form an ecosystem. While this publication uses the terms culture and heritage, this approach also includes the wider creative industries.[footnote 7]

The CHC Programme is designed to benefit a wide array of stakeholders across the public and private sectors. From government bodies and public sector economists, to private practitioners and academics, the framework will offer a tool for deeper understanding and better decision making. Cultural and heritage organisations will be able to use this approach to demonstrate their full value to society, helping them secure investment, and ensure long-term sustainability.

Undertaking SCBA has always been a formal part of how decisions are made regarding the spending of DCMS and its public bodies, particularly large capital projects from our largest organisations such as the British Museum, British Library, British Film Institute, Science Museum and Tate. In addition, SCBA is fundamental to many cross-government funds, where the inclusion of CHC is starting to influence the assessment of culture’s impact on public funding.

CHC can overlap with Natural Capital and the approach and guidance developed by the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs. This is particularly relevant in the historic environment, where heritage assets can also be Natural Capital assets providing ecosystem services. It is important to consider how these frameworks can be implemented to provide a broad evidence base for decision making, while also avoiding double counting, and ensuring that the underlying philosophies are consistent.

The focus of ‘Embedding a Culture and Heritage Capital Approach’

‘Embedding a Culture and Heritage Capital Approach’ presents a baseline description of stocks, and the flow of services and benefits.[footnote 8] While the framework can be used to help articulate the impact of culture and heritage interventions, it is still very much in development and will evolve through consultation with the sector and academia.

This publication also summarises the growing evidence base of CHC research outputs that can be used within appraisal and evaluation, and our long-term ambition of establishing a set of Culture and Heritage Capital Accounts.[footnote 9] The ONS has already developed a set of UK Natural Capital Accounts that the CHC Programme will look to emulate to ensure work on Beyond GDP, related to the System of National Accounts (SNA), incorporates the full impact of the creative, cultural and heritage sectors. Table 1 sets out the benefits of both SCBA and capital accounting.

The final chapters are aimed at practitioners and researchers who are looking to understand how to implement the latest research, and are looking to address evidence gaps in economic appraisals and evaluation. While this is aimed at people with some existing knowledge or experience in appraisals, evaluations and conducting SCBA, this chapter will also help anybody who is interested in understanding how to articulate and use these economic-led methods and evidence when making the case for culture and heritage investment and management strategies.

While there are still evidence gaps which can limit the full application of SCBA, the CHC Programme aspires to fill these gaps and ensure all impacts are assessed during appraisal when considering culture and heritage. Current guidance and research are available on the DCMS, ACE (Arts Council England), and HE (Historic England) CHC Portals.[footnote 10]

Table 1: The benefits of a CHC approach to decision makers

| SCBA | Capital accounting |

|---|---|

| Articulate the impact of specific culture and heritage projects or interventions in a consistent and unified way, aligned with language used in public policy, such as HMT’s Green and Magenta Books. | Monitor and evaluate the quantity, extent, condition and value of culture and heritage assets over time, including changes to stocks and flows. |

| Significantly reduce the risk of impacts on culture and heritage (whether monetised or not) being ignored in decision making. | Assess the value of future services provided by an asset. |

| Enable a more comprehensive SCBA and risk assessment, and allow for a stronger strategic case (case for change) to be made for investment. | Identify priority areas for investment, and inform resourcing and management decisions. |

| Facilitate the identification of policy solutions. | Highlight links with economic activity and pressures on CHC assets. |

| By providing a more thorough assessment of impact, SCBA enables more efficient use of resources to ensure interventions provide value for money. | Provide a common framework to bring together scientific, economic and social evidence with analysis for a particular subject or place. |

| Promote transparency and accountability in decision making processes. | Understand the links between different types of capital. |

2. Introduction

2.1. Development of the Culture and Heritage Capital Framework

In 2021, DCMS published its ambitions to develop a formal approach for valuing the costs and benefits of culture and heritage to society, called the Culture and Heritage Capital (CHC) Framework.[footnote 11] The publication set out that there was currently no consistent approach to measure the benefits of culture and heritage to society within social cost-benefit analysis (SCBA) and national accounting. Without a consistent approach, the benefits of culture and heritage are often undervalued or implicitly valued at zero, meaning the amount or allocation of funding for projects involving culture and heritage capital might be inefficient.

‘Embedding a Culture and Heritage Capital Approach’ (ECHCA) builds on the 2021 CHC Framework by providing a starting point for the development of assets, services and benefit flows definitions, which will evolve over time working with the sector and academics. ECHCA also provides an update on the research published since 2021, plans for future research and potential applications of the research.[footnote 12]

At the heart of the CHC Framework is the need for economic analysis of demand and the capacity to supply assets, goods and services within the creative, cultural and heritage sector. This is in order to combine standard measures of economic contribution with social and/or cultural values to ensure that the full impact on welfare, sustainable growth and long-term standards of living is fully accounted for.[footnote 13] Therefore, as well as valuing the sector’s economic contribution (for example, productivity and jobs), [footnote 14] the CHC approach will also look to value benefits (as well as disbenefits) that may not already be included in existing economic statistics, including, but not limited to, health, education and social cohesion, alongside dimensions of cultural value, such as aesthetic, emotional, spiritual, historical, symbolic and authenticity value.

This is consistent with HMT Green Book (2022), which defines the welfare approach as:

The appraisal of social value, also known as public value, is based on the principles and ideas of welfare economics and concerns overall social welfare efficiency, not simply economic market efficiency. Social or public value therefore includes all significant costs and benefits that affect the welfare and wellbeing of the population, not just market effects. For example, environmental, cultural, health, social care, justice and security effects are included. This welfare and wellbeing consideration applies to the entire population that is served by the government, not simply taxpayers.

The CHC programme also aligns with the Office of National Statistics and United Nations work on moving Beyond GDP.[footnote 15] This is a holistic view on how society is doing, beyond purely economic measures, to ensure decisions fully account for their impact on society and the natural environment.

Alongside the overarching framework, DCMS and its arm’s length bodies (ALBs) are looking to develop:

-

a bank of evidence and values for a range of culture and heritage assets, including economic, cultural and heritage values.

-

supplementary guidance to the Green Book that can be used in policy and project appraisal and evaluation, where there is need for organisations to undertake appraisal (SCBA), evaluation, and/or provide a strategic rationale for intervention.

-

a longer-term ambition of developing a set of Culture and Heritage Capital accounts (see Section 4.5),[footnote 16] consistent with the approach taken by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) for inclusive measures of growth and moving beyond GDP, based on the inclusive wealth framework, set out in Dasgupta & Maler (2000).[footnote 17]

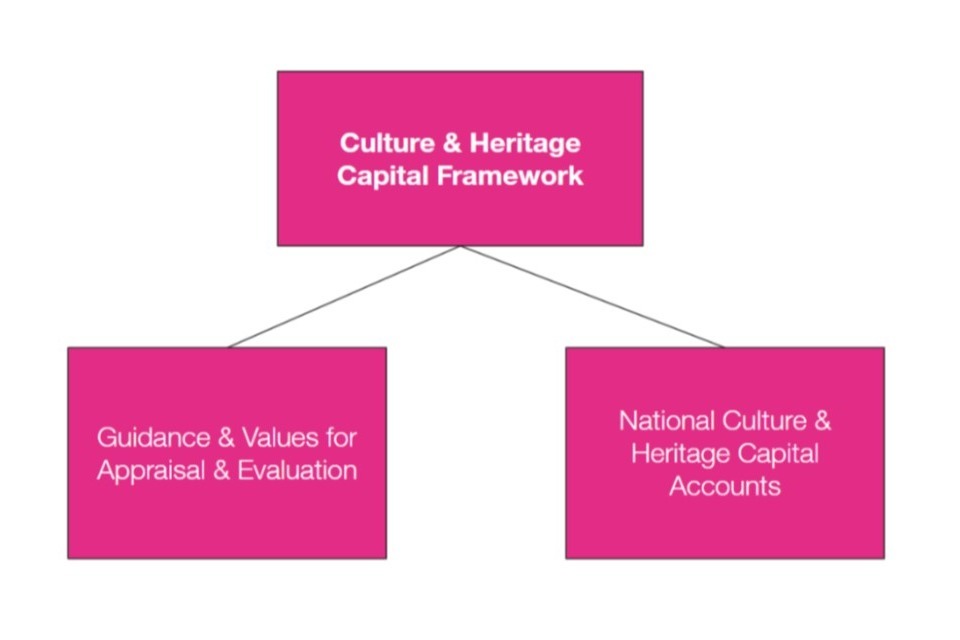

Figure 1 sets out the three pillars of the CHC programme in which DCMS and ALBs will deliver these outputs. These are the conceptual framework, guidance for appraisal (SCBA), evaluation, and National Culture and Heritage Capital accounts.

Figure 1: The Culture and Heritage Capital Programme

SCBA and national accounts are tools used to address different policy questions - see Box 1 for the differences between the two. Guidance for appraisal and evaluation allows central and local government, cultural organisations and practitioners to appraise, or demonstrate the value of, specific policies regarding culture and heritage assets without the need for costly and resource-intensive primary research.

SCBA should always be conducted in a proportional way - in some cases it may be more appropriate to use different variations of SCBA. For instance, Social Cost-Effective Analysis can be applied when socially agreed outcome levels need to be achieved. HM Treasury’s Green Book provides guidance to help make a decision on the most suitable method. This is particularly important when making the case for an investment that requires full valuation of costs and benefits, and an understanding of value for money to the public.

However, SCBA should also sit alongside a wider set of evidence that can inform decision making, and should not replace, for example, existing artistic decisions and their objectives, but instead provide an additional tool to allow for improved articulation and understanding of the value of culture and heritage in decision making. Combining qualitative and quantitative evidence (mixed methods) and expert opinions are also still important, and play a role in strategic cases to complement SCBA where monetisation is difficult. They can also provide more robust appraisals and evaluations where SCBA can not capture the full costs and benefits to inform decision making.

Accounts, on the other hand, help track stocks and flows of assets in physical quantities and values over time. A set of Culture and Heritage Accounts would provide a ‘big picture’ view of the state of culture and heritage assets in the UK, and help understand whether CHC assets are being managed sustainably. Decision makers are likely to ask several types of questions regarding the management of CHC and therefore a suite of tools, from specific SCBA guidance to national accounting methods, are required.

Developing a comprehensive set of National Culture and Heritage Capital Accounts, a longer-term ambition of the programme, will help centre sustainable management of CHC in decision making through systematic, standardised and regular assessments of the contribution of culture and heritage to the economy. CHC accounting will help to measure, value, monitor and communicate the state of culture and heritage assets, bringing together a coherent body of physical and monetary information on the assets themselves and the flows of services they supply (see Section 4.5 for more information on the CHC approach to capital accounting).

Box 1 sets out the differences between SCBA and capital accounting.

Box 1: Differences between social cost-benefit analysis (SCBA) and capital accounting

| Difference | SCBA | Capital accounting |

|---|---|---|

| Scope | Assesses the impact of different interventions (options) on social welfare. All relevant costs and benefits are valued in monetary terms, unless it is not proportionate or possible to do so.[footnote 18] | Used to measure, value, monitor and communicate the state of CHC assets over time within a given boundary.[footnote 19] Not specific to a particular policy. Works at various spatial scales. |

| Focus | Informs decision making for specific policy or spending interventions by appraising an intervention’s overall impact on social welfare against its costs. | Informs the strategic context, and will be ongoing and repeated. Production costs not included. |

| Who | Can be used by organisations that need to reflect the costs and benefits of culture and heritage to understand value for money, interventions and options analysis. For example, government and other public sector economists or analysts at national and local level, and private practitioners that are advising or undertaking appraisals and evaluation of projects that involve culture and heritage. | Can be used by organisations that need to assess and monitor the state of CHC assets which can change over time. For example, government and other public sector economists or analysts, and private practitioners that want to understand the strategic context of assets. |

| Valuation concept | Reflects welfare values. | Based mostly on exchange value (values that reflect prices were a market to exist). However, welfare values can be accounted for where appropriate. |

See Section 4.5 for more information on capital accounting.

Chapter 3 of this publication provides a greater discussion of the overarching CHC framework; while the framework can be used to articulate the impact of culture and heritage interventions, a capitals approach is also taken to help inform the continued development of the framework. However, it should be noted that the CHC Framework is still very much in development and subject to change.

Chapter 4 of this publication is aimed at practitioners looking to understand how to implement the latest research to incorporate CHC into economic appraisals and evaluations and researchers who would like to contribute to future research and address evidence gaps. While this is aimed at people with some existing knowledge or experience in appraisals and evaluations, this chapter will also help anybody who is interested in understanding how to articulate these economic-led methods when making the case for culture and heritage investment and management strategies.

The cultural, creative and heritage sectors make up a set of interrelated sectors that together form an ecosystem. As set out in the executive summary, while this publication uses the terms culture and heritage, this approach also includes the wider creative industries. However, for the purposes of this publication the term culture and heritage will be used.

2.2 Why measure the value of culture and heritage

As set out in Valuing Culture and Heritage Capital: a framework towards informing decision making (2021), HM Treasury’s Green Book recommends expressing the full costs and benefits of a proposal in monetary terms, known as Social Cost Benefit Analysis (SCBA).[footnote 20] In the public sector, SCBA is used to quantify the effects of a policy or project on UK social welfare. HM Treasury’s Green Book provides guidance and theoretical foundations for instruments of public economics, including appraisal, to inform decision making.

To ensure that the preferred policy option delivers value for money and maximises public welfare relative to alternatives, all benefits and costs to society need to be included in SCBA, not just financial benefits, for example wages, and other standard measures of economic output, such as productivity. In fact, standard economic measures are an incomplete measure of public welfare and value added, as they do not take into account assets and services that do not have market prices.

Valuation enables comparisons of interventions supporting culture and heritage that deliver a wide range of benefits to different people. Through converting the value of these benefit flows into a common monetary metric, valuation enables like-for-like comparisons. This ensures resources are allocated to projects and programmes that maximise public welfare and therefore value for money. Table 2 outlines how a Culture and Heritage Capital approach (including both SCBA and capital accounting) will aid decision makers.

Table 2: The benefits of a CHC approach to decision makers

| SCBA | Capital accounting |

|---|---|

| Articulate the impact of specific culture and heritage projects or interventions in a consistent way, aligned with language used in public policy, such as HMT’s Green and Magenta Books. | Monitor and evaluate the quantity, extent, condition and value of culture and heritage assets over time, including changes to stocks and flows. |

| Significantly reduce the risk of impacts on culture and heritage (whether monetised or not) being ignored in decision making. | Assess the value of future services provided by an asset. |

| Enable a more comprehensive SCBA and risk assessment, and allow for a stronger strategic case (case for change) to be made for investment, particularly where SCBA is required by funders. | Identify priority areas for investment, and inform resourcing and management decisions. |

| Facilitate a more innovative approach to identifying policy solutions. | Highlight links with economic activity and pressures on CHC assets. |

| By providing a more thorough assessment of impact, SCBA enables more efficient use of resources (value for money). | Provide a common framework to bring together scientific, economic and social evidence with analysis for a particular subject or place. |

| Promote transparency and accountability in the decision making processes. | Understand the links between different types of capital. |

At the Valuing Culture and Heritage Capital Conference in 2022,[footnote 21] DCMS set out the following important points regarding the CHC Programme:

-

The framework and guidance on valuation techniques is not just for the public sector, but is also applicable to private sector organisations that want to demonstrate their full value to society.

-

It is relevant to decisions that affect culture or heritage outside of the sector, where SCBA is used for decision making; for example, in transport planning and place-based funds. In these situations, culture and heritage investments are often undervalued, or not valued at all, putting them at a disadvantage when it comes to decisions that use SCBA.

-

It enables use of a more comprehensive evidence base to inform decision making. The CHC approach should be used in conjunction with a wider set of evidence, for example, expert opinions, case studies and qualitative approaches in decision making processes. CHC provides another approach to articulating value, using similar approaches employed for health, the environment and crime.

-

The Programme is developing an economic led multidisciplinary approach, similar to the Natural Capital approach. While the aim of the CHC Framework is to use an economic perspective to help inform decision making and articulate the contribution of culture and heritage on UK social welfare (which should include benefits, disbenefits and costs), it needs to be informed by other disciplines, for example, arts and humanities, social sciences, and physical and environmental sciences. Therefore, through the CHC programme, AHRC and DCMS have funded six multidisciplinary projects that include researchers from social sciences, arts and humanities, and heritage science.[footnote 22]

3. The Culture and Heritage Capital Framework - the stocks and flows model

DCMS’ 2021 Culture and Heritage Capital Framework set out a high-level systems approach to demonstrate and increase understanding of how culture and heritage assets contribute to achieving the outcomes we seek as individuals and society.

‘Embedding a Culture and Heritage Capital Approach’ provides further developments of this framework. This will evolve through consultation with the sector, particularly through the AHRC and DCMS funded research programme, launched in 2023.

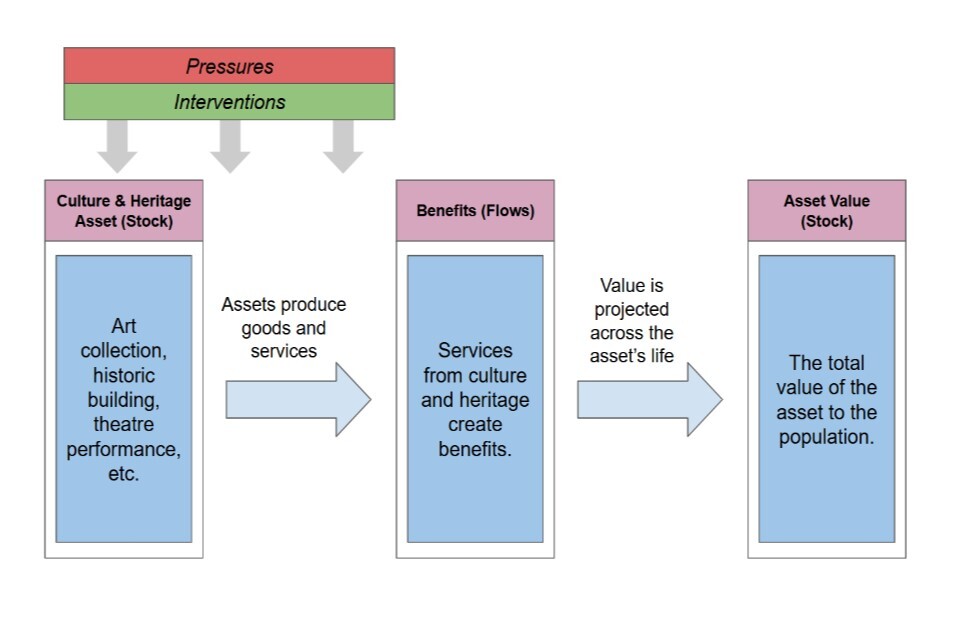

Figure 2: The Culture and Heritage Capital Framework[footnote 23]

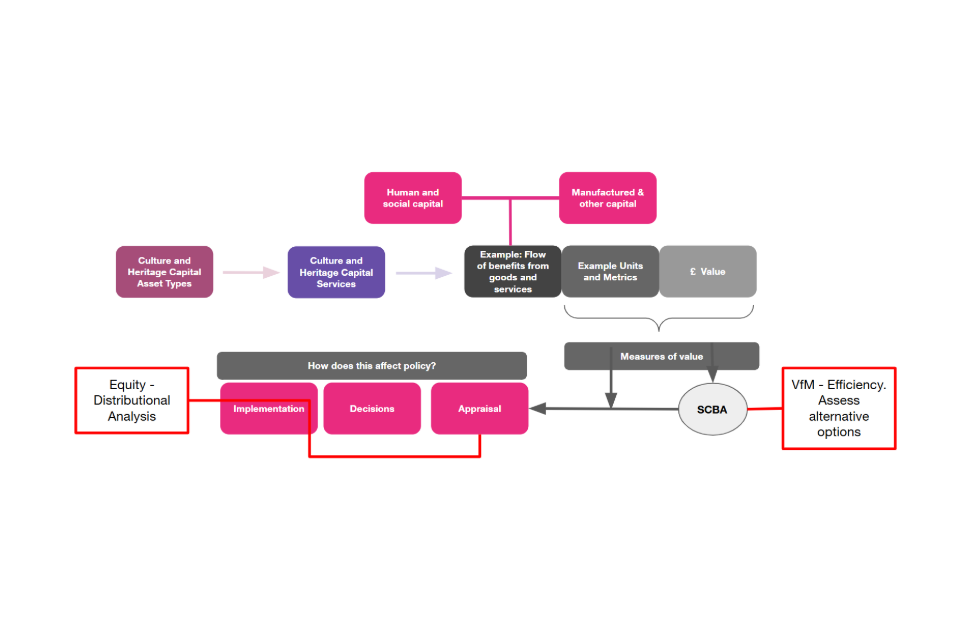

In the CHC Framework, culture and heritage assets (for example, an art collection, historic building or theatre production) are the “stock”. These stocks provide “flows” of CHC services (or disservices) over time. Services, along with production, are inputs to diverse benefits (or disbenefits) to society - some services have direct benefits, while others produce benefits when they are combined with other forms of capital (such as human or natural processes).

The stock of CHC assets at any point in time is determined by investment in the creation and maintenance of assets and their services, as well as the negative effects of pressures. Pressures such as environmental change can cause the asset to degrade over time, as well as negatively affecting the services provided by an asset and/or the demand for those services. However, these may be mitigated by interventions such as effective management.

This means the preservation and conservation of culture and heritage capital is an important component of a sustainable socioeconomic system.[footnote 24] However, in some instances, degradation may result in new or altered services and benefits.[footnote 25] The CHC framework could help better understand and support those changing services (for instance, when an archaeological site is excavated).

The Natural Capital approach has influenced the development of the CHC Framework, specifically the ‘Enabling a Natural Capital Approach guidance’ published by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA).[footnote 26] From a theoretical point of view, the parallel between the two capitals has been successfully used in recent decades to interpret in economic terms the key characteristics of cultural heritage.[footnote 27] While there are similarities between Natural Capital and CHC, and instances where Natural Capital assets overlap with culture and heritage assets, culture and heritage has distinct and unique stocks and services flows that must be accounted for, and measured in conjunction with those natural environment service flows. For example, authenticity services such as historical significance, uniqueness, symbolism, and many others (see Table 4).

The Natural Capital approach has been developed over more than a decade, and there is still no complete consensus on the framework. This is expected to be the case with the CHC Framework, which is why this paper provides the beginning of an iterative conversation between DCMS, the sector and academia that is anticipated to evolve over time.

This framework has been informed by previous commissioned research. In 2023, DCMS commissioned IPSOS to undertake a review of the literature around existing literature on cultural capitals. Culture and Heritage Capital (CHC) Proto-Typology provides a further in-depth review of:[footnote 28]

-

Contributions from Natural Capital and cultural studies, to provide further insights on the types of cultural and heritage services which should be captured in a CHC typology. The contributions include The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB) classification[footnote 29] and the most recent version (5.1) of the Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services (CICES).[footnote 30] These are standardised frameworks for classifying and describing the benefits received from ecosystems.

-

Three alternative models of proto-typologies, reflecting the fact that the Lawton et al (2024) study aimed to open doors and set out options, rather than to posit a single finalised proto-typology, which could be explored in future projects. These include one based on the approach from natural capital, one bespoke model reflecting the understanding of value from the arts and humanities, cultural studies and cultural sector, and one based on a strategic practice perspective.

-

Recommendations for future research for each of the three proto-typology options.

The framework has been further developed beyond Lawton et al (2024), through additional evidence collection and feedback from the CHC steering group, Advisory Board and discussions with stakeholders. DCMS acknowledges the systems-based approach, as set out in Figure 2, has meant simplifying complex processes and in some cases, the flows of services and benefits are hard to articulate in words. However, this simplification is necessary in order to produce something that can then be usable in practice.

The following sections are not exhaustive lists; we also recognise that CHC is a conceptual approach that may not be relevant for all purposes, and the language used may not always resonate with all groups. We also expect definitions of assets, services and welfare benefits to evolve following feedback and further discussion. If you have any feedback, DCMS would be grateful to receive this at chc@dcms.gov.uk.

3.1 Culture and heritage assets (stock)

At its simplest, a Culture and Heritage Capital (CHC) approach is about thinking of an asset, or set of assets, that embody culture or heritage. The ability of a culture and heritage asset to provide goods and services is determined by its characteristics, which could include, but are not limited to, condition, history or design. Defining these characteristics is more difficult for culture and heritage than for other forms of capital, as the services are often derived from how a person interprets or feels about their interaction with both tangible and intangible assets. Further research is ongoing to understand the relationship between the characteristics of a culture and heritage asset, and the services they provide.

DCMS is taking an assets-based approach, consistent with the approach taken by the Natural Capital Committee. Some assets are geographically fixed and long-lasting, such as a historic house or listed building, or mobile such as a stream train; others such as museums, art galleries and archives are fixed buildings that house and display collections which are themselves drawn upon to be loaned for exhibitions elsewhere; still others are art forms such as music, theatre and dance whose individual productions are ephemeral; while some have no physical existence, such as intangible heritage.

DCMS has grouped culture and heritage assets into eight broad categories (see Table 3). These have been kept deliberately high level, and while Table 3 includes many examples under each category, these are not exhaustive so the focus should be on the broad category types. Over time these categories will be refined to allow for a more comprehensive and applicable asset categorisation, particularly through the DCMS/AHRC funded research Developing a taxonomy for Culture and Heritage Capital (see Section 5.1).

At this stage of development there are overlaps between asset classes, for example, a museum collection housed in a listed building. In some cases, overlaps might be important to acknowledge, as some assets may form an ensemble, which together provide greater value, such as a historic high street. Further research will be required to understand the overlaps.

With some asset categories, there are grey areas that must be acknowledged. For example, digital assets could be classified as sub-categories of other asset types, such as collections. Similarly, intellectual property and copyright could be a way to govern the use and attribution of assets, and rather shape the service flows and resulting benefits provided, much like permits in Natural Capital. Therefore, this list requires further discussion and research, and may be updated in the future.

DCMS also recognises that some asset definitions are often determined by people and communities. Therefore, some assets may be considered ‘cultural’ but are not present in Table 3. There may also be new and emerging assets, especially in the digital space, which are missing. DCMS is interested to hear if any assets may be missing or incorrectly defined.

Table 3: Culture and heritage assets

| Asset | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Built historic environment[footnote 31] |

Buildings and structures of heritage or historical significance and/or use. | Historic buildings and structures Structures of significance including high streets, sports heritage, places of worship, other recreation buildings and skylines. |

| Cultural venues and production facilities | Assets that provide venues for cultural activities, and culture and creative production. | Cultural venues including theatres, cinemas, galleries, concert halls, libraries, museums, and other heritage attractions. Production and post production facilities, for example, film, games, music, visual arts, theatre and dance studios.[footnote 32] |

| Historic landscapes | Land and nature of cultural, and/or historical significance. | Landscapes (including protected landscapes such as national parks), field-scapes, seascapes, woodlands, and views. Designed cultural landscapes such as parks, gardens and trails. Land used for cultural or creative activities (for example, festivals). Archaeological sites and deposits, battlefields, and shipwrecks. |

| Collections and archives | Managed groups of objects (both movable and immovable) with cultural, heritage and/or historical interest, which may have a store of knowledge. | Archives, library art, museum collections, plaques, and steam trains. |

| Creative & artistic works | Creative or artistic outputs by individuals or groups. | Paintings, crafts, sculptures, textiles, fashion, and photography. Film, TV, radio, music, video games, and publications. Theatre and dance productions, exhibitions, and festivals. Associated copyright, performance, design, and other IP rights. |

| Digital assets[footnote 33] | Digitalised collections, archives and creative / artistic content, as well as born-digital content. | Digital archives, digital collections and online creative content. |

| Intangible heritage | Cultural heritage that is living and practised. | Traditions and social practices, including storytelling, folklore, performance, customs and crafts. |

| Creative and cultural knowledge[footnote 34] | Creative and cultural skills, abilities and knowledge, and the information and knowledge required to safeguard it. | Skills and knowledge that enable the creation of creative and artistic content (for example, drawing, painting, designing, writing, singing, dancing, ceramics, weaving and glassmaking). Knowledge of culture and heritage and creative practices (contemporary and historical). |

3.2 Culture and heritage services

Culture and heritage assets can be said to create a flow of services: by understanding the nature of an asset, and its context, it is possible to define the diverse ‘flows’ of services and the benefits they provide. Services can be described as actions, processes, attributes or qualities that lead to benefits, both directly or indirectly, perceived and experienced by society. Services can be produced directly from an asset or combined with other capitals, such as human capital, through production.

This section provides an outline of potential services to be included within the CHC framework. For a further discussion of service definition please see accompanying research by Lawton et al (2024).[footnote 35] There is currently no agreed definition for cultural services. However, the basis for many of the services outlined in this document is Throsby (2003), who defines cultural capital on the basis of its cultural value.[footnote 36]

Throsby writes:

The characteristics of cultural goods which give rise to their cultural value might include their aesthetic properties, their spiritual significance, their role as purveyors of symbolic meaning, their historic importance, their significance in influencing artistic trends, their authenticity, their integrity, their uniqueness, and so on.

These services focus predominantly on those that involve culture and heritage. They acknowledge that culture and heritage interconnects with individuals, society and the environment in complex and diverse ways.[footnote 37]

Table 4 sets out eight broad categories of cultural and heritage services. This includes, for example, aesthetic and authenticity services which are part of shaping places in terms of character, attractiveness, design, brand and distinctiveness. Communal and identity services drive place based relationships through diverse cultural expressions, traditions and histories that contribute to a community’s identity and sense of belonging. Knowledge services, both formal and informal learning, involve the acquisition, creation and dissemination of knowledge and learning that supports personal development, inspiring creativity.[footnote 38]

It is important to note that the table does not provide a definitive list or categorisation of services, nor does it replicate any one of the three proto-typology options presented in Lawton et al (2024). Rather, it sets out a broad set of service categories informed by the underlying CHC proto-typology work in Lawton et al (2024), and will be subject to further development, drawing on the CHC Programme and other research. Therefore, while Table 4 includes many examples under each category, similarly to the asset definitions, focus should again be on the broad category types.

Services can not only be hard to measure but also hard to define, and must therefore be acknowledged in other ways; for example, using qualitative and expert evidence. The expectation is not to separate and monetise each individual service, but instead allow for the identification and understanding of welfare impacts. During monetisation, many of the examples presented in the table will be grouped together, and future research will allow us to understand these overlaps (see Section 4.3 for more information on economic valuation).

As such, some of these service types will be combined until further in depth work has been carried out. DCMS will be looking for the AHRC and DCMS funded research project Developing a taxonomy for Culture and Heritage Capital to further iterate on this approach. The project will also tackle issues of overlap between categories (for instance, communal and identity services), and the links to associated benefits outlined in Section 3.3.

Condition of assets is anticipated to be a key characteristic, as this will impact the flow of services the asset can provide. Albeit a complex topic, a recent DCMS publication outlined how heritage science could be used to assess condition and the link to economic valuation.[footnote 39] This approach looks to estimate the potential loss of welfare from delaying or stopping conservation, protection, repair and/or maintenance of assets, including for intangible assets such as skills and traditions.

However, conservation is defined as the management of change, and in many instances it may not be possible, or desirable, to maintain a constant condition. In such circumstances CHC could become an important tool to help navigate how benefits can be realised by better understanding the services and potential services of assets in different conditions.[footnote 40]

Table 4: Culture and heritage services

| Service | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Aesthetic services[footnote 41] | Provide individuals with sensory, emotional and intellectual stimulation as a result of the asset’s appearance - design, beauty, and architectural character and artistic endeavour.[footnote 42] | Aesthetic enrichment, architectural character, attractiveness, beauty, captivation, congruence, design, distinctiveness, escapism, pleasure, reflection, spirituality. |

| Authenticity services[footnote 43] | Considers authentic value of culture and heritage assets, derived through their meaning, existence and historical significance, and reflect a unique and irreproducible character, meaning identity, symbolism and significance. | Atmosphere, distinctiveness, experiences, historical significance, inheritance, meaning, motivation, symbolism, uniqueness. |

| Communal services | Reflect the qualities of the relationships between humans and culture and heritage that foster a sense of identity, belonging and pride. | Attachment, civic engagement, communal meaning, community identity, networks, peace, political dialogue, reflection, sanctuary, social bonding, social connectedness and contact. |

| Inspirational and creative services | Services that inspire and motivate individuals, providing satisfaction and information through performing, celebrating and promoting culture and heritage. | Aspiration, captivation, creativity, curation, design, escapism, expression, hope, imagination, innovation, intellectual exploration, intellectual stimulation, motivation, pleasure, reflection, resonance, spiritual uplift. |

| Identity services | Recognise, protect, and promote diverse cultural expressions, traditions and histories that contribute to a community’s identity and sense of belonging. | Connectedness, cultural interpretation services, curiosity, empathy, empowerment, inquisitiveness, introspection, purpose, reflection, spiritual meaning, traditions, understanding of diverse cultures. |

| Knowledge (educational) services | Formal and informal learning that involves the acquisition, creation and dissemination of knowledge and learning that supports personal development, creativity and innovation. | Access, comprehension, education, flourishing, historic understanding, knowledge sharing, memory, research and development, skills development, teaching. |

| Health services | Services that improve overall health, quality of life and mental wellbeing of individuals, providing supportive and preventative interventions. | Physical and mental health services, wellbeing practices. |

| Environmental services | Services provided through the interactions of culture and heritage with nature (including natural resources and natural processes and functions underpinning them).[footnote 44] | Diversity in species, habitat, reductions in flood risk and soil erosion, removal of urban air pollution by trees, settings for recreation, water supplies and regulation. |

Most culture and heritage assets are produced by humans and therefore actions, processes, production and interventions can play an even greater role in enhancing their impact.

Some culture and heritage services are currently captured within the Natural Capital framework. We acknowledge that natural assets and culture and heritage assets are often intertwined. Therefore, some environmental services have been included within the culture and heritage services framework to ensure we are capturing the full spectrum of benefits.

Interactions with the Natural Capital Framework (including potential gaps and overlaps) will need additional consideration to resolve uncertainty about how to combine the CHC and Natural Capital Frameworks. The relationship and practical integration between the two will be explored as part of an AHRC/DCMS Research Programme project led by Dr. Amy Binner titled Understanding the Value of Outdoor Culture and Heritage Capital for Decision Makers.[footnote 45]

Another category that does not yet feature in Table 4 is capital services. These are defined as the flow of productive services from an asset, for example, service flows from a building including floorspace accommodating recreation activities or employment space. Further work is needed to understand how these are incorporated into the framework, and as such, could be added at a later date.[footnote 46]

A further category of services that has been discussed with stakeholders has been conservation, maintenance, preservation and interpretation. While these may not produce outputs for final consumption or production, they are essential for the functioning of other services denoted in Table 4. Therefore, it is our opinion that these would be better classed as inputs, not services, within the framework.

3.3 Services create benefits (flows) - welfare impacts

Goods and services produced by culture and heritage assets provide traded and non-traded benefits (or disbenefits) to people. These include, for example, improving wellbeing, increasing knowledge, and further spillovers to the wider population, such as contributing to a more productive workforce. Some services can also create dis-benefits; for example, a theatre in poor condition can be perceived to be unattractive (negative aesthetic services), while identity services can impact community cohesion.

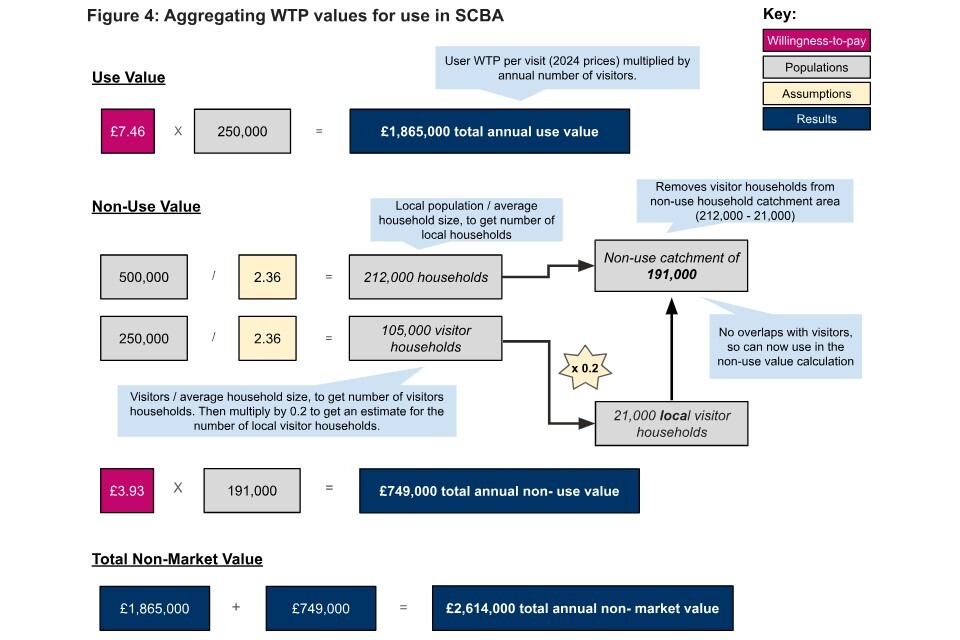

The values of such benefits can be estimated using market and non-market valuation techniques. Once monetary values are estimated for the flows, it is possible to estimate the value of the asset as a whole by forecasting values over time, and calculating their present value.[footnote 47] However, it is changes to these flows that are the focus of valuation in appraisal.

Table 5 shows the culture and heritage service categories and the final welfare effects to be valued and monetised in SCBA. These have been developed using a distillation of the outcomes laid out in the proto-typology options in Lawton et. al (2024), as well as DCMS expertise. This table does not provide a definitive list of welfare benefits, and will be subject to further development. In many cases, services will have similar benefits flows, for example economic outcomes and wellbeing may flow across many services.

However, there may also be certain values that cannot be quantified, let alone captured using economic valuation. Such benefits still need to be identified so current approaches will need to be connected to arts and humanities to understand the link between assets, services and welfare benefits.

Equally, some of these welfare effects may overlap, so should not be aggregated and attributed to the asset value in their entirety, as this will lead to double counting. Similarly, most valuation techniques will capture multiple services and welfare effects, and isolating the value of each individual welfare effect will be difficult. Further research will be undertaken to understand the extent to which these welfare effects are monetisable and overlapping, as well as what different economic valuation methods are capturing - for instance, the CAVEAT: Triangulation of Methods project.

Table 5 should not be interpreted as just the benefits arising from culture and heritage services. In some cases, these can also be disbenefits where interventions may have the opposite effect on welfare, e.g. reducing wellbeing or social cohesion, or increasing pollution. These costs also need to be captured in SCBA.

Table 5: Welfare outcomes of culture and heritage services

| Service | Associated welfare outcomes |

|---|---|

| Aesthetic services | Emotion, employment, enjoyment, final production of goods and services, happiness, income, mental and physical health, self-esteem, wellbeing. |

| Authenticity services | Creativity, emotion, employment, enjoyment, final production of goods and services, happiness, income, mental and physical health, identity, nostalgia, wellbeing. |

| Communal services | Altruism, belonging, bequest, community identity, inclusion, national identity, pride in place, social cohesion, trust, wellbeing. |

| Inspirational and creative services | Emotion, employment, enjoyment, final production of goods and services, happiness, income, personal development, productivity, wellbeing. |

| Identity services | Attachment, belonging, emotional development, developing new knowledge, inclusion, personal development, pride, sense of identity. |

| Knowledge (educational) services | Educational attainment, employment, final production of goods and services, income, innovation, non-cognitive skills, productivity, skills and qualifications. |

| Health services | Increased physical and mental health, personal and community wellbeing, productivity, quality of life. |

| Environmental services | Diversity in species, improvements in drinking water supplies and quality, reductions in air pollution, reductions in impacts of flooding, resilient biodiversity. |

These welfare effects should be monetised using appropriate economic valuation methods and metrics where possible, as set out in Sections 4.3 and 4.4, respectively.

4. Application of Culture and Heritage Capital

4.1 Culture and Heritage Capital in policy or project appraisal

This section is consistent with, and builds on, HM Treasury’s Green Book. It provides guidance on how the Culture and Heritage Capital (CHC) approach can be applied at each stage of the appraisal cycle (rationale for intervention, options appraisal, and assessing impacts) to help answer specific policy questions or provide social cost benefit analysis (SCBA) to different interventions. During appraisal, the risks, opportunities, costs, benefits, and uncertainties should be identified. Before taking this approach it will be important to understand who the analysis is for, and how it will be used within the decision making process. This will ensure that the approach taken is proportional and meets the needs and context in which decisions are being made.

While there are still evidence gaps, which can limit the full application of SCBA, the CHC Programme aspires to fill these gaps and ensure all impacts are assessed when considering culture and heritage interventions. The CHC Programme will provide sector specific guidance that does not currently exist, despite guidance already existing for crime, the environment, health and transport, and allow cultural organisations to undertake SCBA without the need for costly primary research. Current guidance and research is available on the DCMS, ACE, and HE CHC Portals.[footnote 48]

This chapter is aimed at practitioners looking to understand how to implement the latest CHC research into economic appraisals and evaluations, and researchers who would like to contribute to future research and address evidence gaps. While this is aimed at people with some existing knowledge or experience in appraisals and evaluations, this chapter will also help anybody who is interested in understanding how to articulate these economic-led methods when making the case for culture and heritage.

Incorporating CHC into appraisal of proposed projects and policies supports a range of policy goals. It enables more comprehensive appraisal, which considers how proposals affect stocks of culture and heritage assets directly, and how they impact the benefits those assets and their services provide to society (both positively and negatively). The purpose of estimating monetary values of impacts on benefits of CHC is to place all costs and benefits of the policy or project into the same ‘unit of account’, meaning pounds and pence, to ensure they can be compared on an equivalent basis.

The use of CHC in economic appraisal is one tool for decision making, and should be used in conjunction with a suite of other options, such as expert opinions, case studies, qualitative and narrative approaches. This applies not only to the appraisal but other parts of a business case, particularly the strategic case, which plays an important role in setting out the evidence base and rationale for intervention. As such, this approach should aid, but not replace alternatives, such as artistic decisions. SCBA may be used to allow for improved articulation and understanding of the value of culture and heritage in decision making, where making the case for investment should include the full valuation costs and benefits and an understanding of value for money to the public where possible.

HMT’s Green Book should be consulted for greater detail on rationale, generating options (long and short lists) and undertaking appraisal and evaluation. This section provides key concepts for further context on the current and future outputs of the CHC programme.

Rationale for intervention

To ensure that public funding is being invested in projects and programmes that offer value for money and provide additionality, public sector interventions must be addressing a particular issue within the market, such as market failure or equity concerns.

Market failure can occur for several reasons. When present, markets may undervalue the benefits of culture and heritage, leading to an undersupply of goods and services and/or individuals undervaluing the benefits of engagement, leading to socially inefficient levels of demand. Where market failure exists, markets and individuals acting alone cannot be relied on to produce a socially optimum level of supply and demand. A strong rationale proposes government intervention will overcome market failure and increase overall societal welfare.

Culture and Heritage Capital is associated with several types of market failures which can justify government intervention. At the beginning of an appraisal, it is important to outline a strategic case for investment, which includes outlining the potential market failures the intervention is attempting to rectify. Annex A sets out a more detailed description of types of market failures, which include:

- externalities

- public goods

- information failure

- coordination failure

- market power

- merit goods

Alongside these market failures there might be equity considerations - this is the redistribution of resources to allow for greater levels of equity. Some groups may be targeted (for example age, race, gender, disability, employment status or socio-economic group) in pursuit of equity and fairness.

Government intervention in the absence of market failures can disrupt markets and reduce welfare, known as government failure. Government failure can also occur when the cost (such as expenditure or regulation) of intervention exceeds the benefits to society. This is why the identification of market failure is a necessary step in justifying a policy intervention, but it is not sufficient on its own. To prove that an intervention is worthwhile, there needs to be a body of evidence which verifies the market failure and illustrates the impact that results from intervention. A key element of this is establishing additionality, that is, showing that the impacts derived are greater than those that would have occurred without government intervention and therefore benefits of provision outweigh the costs.

Generating options

Where enhancing or protecting Culture and Heritage Capital is the objective of policy or spending (for example, the restoration or redevelopment of a museum), the standard Green Book approach to identifying a range of options applies.

As set out in the Green Book, a longlist of possible options should be generated, which can be filtered down to a shortlist suitable for detailed social cost benefit analysis. Guidance can be found in the Green Book - supplementary guidance specific to culture and heritage based options and how approaches can support policy goals will be developed in due course.

Assessing impacts

A stocks and flows model has been adopted for the Culture and Heritage Capital (CHC) framework, as set out in Figure 3 and explained in Chapter 3. The approach demonstrated how an asset, or set of assets, that embodies culture and heritage, contributes to achieving the outcomes sought as individuals and society, and how these benefits are captured.

Figure 3 - The Culture and Heritage Capital framework[footnote 49]

The following steps can be used to guide the assessment of how a proposal may affect culture and heritage assets, what it means for welfare, and how these effects can be valued. They do not intend to provide detailed guidance on how to write a full SCBA or business case - the HMT Green Book should be consulted when preparing appraisals and business cases.

Step 1: Consider the culture and heritage assets

The first step is to understand the relevant culture and heritage assets that may be affected or contribute to outcomes associated with the specific proposal or intervention. These assets, for instance a museum or art collection, are the stock (the broad categories of assets are set out in Section 3.1.

Step 2: Consider the culture and heritage services

As aforementioned in the stocks and flows model in Section 3.2, culture and heritage assets provide services to society (for example aesthetic services). It is important during appraisal to consider the full range of services provided to fully articulate the impact of an intervention. For instance, a museum can provide aesthetic, authenticity and educational services, amongst many others.

Defining these characteristics is more difficult for culture and heritage than for other forms of capital as services are often derived from how a person interprets or feels about an asset. Examples of services are outlined in Table 4. Step 1 and 2 facilitate the identification and assessment of welfare effects in step 3.

Further research is needed to identify a comprehensive range of goods and services provided by culture and heritage assets, and to understand the relationship between the characteristics of assets and the services they provide. This will be taken forward as part of the AHRC/DCMS Research Programme (see Section 5.1).

Similarly to the assets, definitions of services will also evolve over time, and should only be seen as a guide. We would also like these to be informed by real world application. If you have any feedback, DCMS would be grateful to receive this at chc@dcms.gov.uk.

Step 3: Consider the welfare impacts

Once the appropriate services are outlined, this helps facilitate an assessment of the benefits provided by them, and the welfare effects attributable to the services over time. An important step in this approach before monetisation is to measure the change created by a proposed intervention through metrics (for example, users, employment, wellbeing) and wider qualitative and quantitative evidence. It is the marginal impacts and changes to these benefits with respect to the counterfactual which are the focus of valuation in appraisal. For instance, if an intervention is focused on improving the services provided by an asset, only the additional benefit provided by the proposal above the status-quo (or ‘do nothing’ option) should be considered.

Step 4: Monetise the welfare impacts

SCBA requires that benefits are estimated in monetary terms where feasible, to ensure they are in the same unit of account as costs. As set out in Figure 3, where possible, each outcome will be linked to a specific metric to consistently monetise the welfare impact. However, the extent to which this is possible will depend on the outcome, and further research is required to understand potential overlaps and interlinkages. Section 4.3 discusses potential methods for economic valuation and monetisation of benefits produced by culture and heritage assets, as well as potential metrics for consistent measurement.

As set out in HMT Green Book, as part of a shortlist appraisal, proportionate effort should be made to monetise the significant costs and benefits of each option. Economic valuation assumes we know what is to be valued, but in some cases there might be assets and services that are not fully understood and outcomes from loss or enhancement are uncertain. DCMS also recognises the CHC Programme is in an early stage, so some benefits are still unquantifiable and/or unmonetisable.

However, it is important to still record and present all services and benefits as part of the appraisal, even if they cannot be quantified and/or monetised at this stage, to present a balanced assessment. Significant unmonetisable values that are important enough to affect key choices about options should be considered at the longlist stage. At the shortlist stage unmonetisable values should form part of the consideration for determining the preferred option and set alongside the net present social value (NPSV).[footnote 50]

It is also important to consider distributional impact, and the spatial nature and scale of impacts as per HM Treasury’s Green Book guidance on distributional, equalities and place-based analysis, such as whether impacts are localised or widespread (for instance, national, regional or local). Distributional analysis is important where there may be significant redistributive effects between different groups within the UK, and plays a key role in understanding who is affected by interventions.[footnote 51] More specific supplementary guidance on implementing place-based CHC approaches will be developed in due course.

Step 5: Project future benefits across the asset’s life to estimate total asset value

To make effective decisions about culture and heritage assets, it is necessary to consider the likely timeframe of effects (immediate, short term, or longer term), to assess how interventions will impact the total value that the asset provides to individuals and society over its lifetime. This is done by projecting annual monetary values calculated over the relevant time period and discounting appropriately, using HM Treasury Green Book discounting guidance.[footnote 52] As noted in the CHC Scoping Study[footnote 53] it could be argued that, for some CHC assets, due to their irreplaceability and potentially increasing value with time, a specific set of discount rates is required. This will be explored as part of the Programme (see Section 5.3).

However, the ability of culture and heritage assets to provide services across their lifetimes is determined by characteristics including condition, their history or design, and other factors such as the length of the policy or intervention. To assess condition and quality, the CHC Programme will bring together economic methodologies and the work of heritage scientists, who are best placed to estimate the impact of conserving assets, and therefore rates of degradation and irreversible loss.

Following these steps will allow users to undertake value for money assessments that can feed into appraisal, decision making and implementation of the policy.

4.2 Monitoring and evaluation with Culture and Heritage Capital in mind

According to HM Treasury’s Magenta Book, evaluation involves understanding how an intervention has been, or is being implemented and what effects it has, for whom and why.

It is important to consider the monitoring and evaluation strategy at the beginning of an intervention. The risks, opportunities, costs, benefits and uncertainties identified during appraisal should inform the evaluation. For instance, appraisals can identify expected impacts and inform data collection required for monitoring and evaluation. Learnings from previous similar projects, as well as findings from ongoing evaluations can also improve and inform evaluations.

The stocks and flows model (see Chapter 3), including the assets, services and benefits, while not a theory of change, can help in its development . Theories of change identify how and why an intervention is expected to lead to specific change, the anticipated final benefits, the associated risks, assumptions and the importance of context in delivering final benefits.

Interventions linked to CHC are often complex and require innovative monitoring and evaluation methods. The evaluation strategy developed should generate and/or confirm values set out in the appraisal. These should then be used in subsequent appraisals and decision making, strengthening the evidence base further.

Specific monitoring and evaluation guidance for CHC will be made available as the Programme develops. In the meantime, supplementary guidance to the Magenta Book is available, providing guidance on tackling this challenge.[footnote 54]

4.3 Economic valuation of culture and heritage

Economic valuation methods measure how much an asset, product, activity or service is worth in terms of the benefits that are experienced or enjoyed by individuals or organisations. Traditional market methods for valuing culture and heritage, that is, things for which there is an observable market price, are readily available.

However, many of the benefits of culture and heritage are not (or only partially) supplied in private markets, so are not (fully) observable in market prices, for four main reasons:

-

Admissions are often subsidised and not reflective of market powers. For example, many culture or heritage assets are free at the point of use (e.g. some museums, libraries, or digital assets).

-

Heritage and culture are often consumable without entry. For example, admiring a historic house during your commute.

-

Individuals attribute value to culture and heritage without directly consuming it themselves (non-use value). How individuals interpret an asset or its services is also an important consideration for valuation.

-

Culture and heritage that forms part of the market sector often have a social and cultural value above the market price which are often not captured in the market price.

As previously mentioned, this can lead to culture and heritage often being undervalued in decision making, as market based methods only capture a small proportion of the full value of culture and heritage. There are many other social and cultural benefits (see Table 5 - for instance, health and wellbeing, education, use and non-use values, research and development) that are not accounted for in markets that must be valued.

Therefore, we must look beyond market prices to measure the full value of culture and heritage - known as ‘non-market values’. These are harder to identify than market values, but by observing individuals’ behaviour or willingness to pay through the application of non-market valuation methodologies, it is possible to uncover their full value.

The principal current valuation methods can broadly be split between ‘revealed preference’, ‘stated preference’, direct ‘wellbeing’, and cost based approaches. Knowing these methods and their advantages/limitations can help make better use of existing evidence.

One limitation that is important to be aware of is double counting between methods, and as such, some non-market valuation methods cannot be used in conjunction with each other and should be used with caution. For instance, there are known overlaps between contingent valuation (CV) and discrete choice modelling (DCM), wellbeing and CV, and quality adjusted life years (QALYs) and wellbeing adjusted life years (WELLBYs). Similarly, revealed preference methods (such as travel cost or hedonic pricing) can overlap with stated preferences (such as contingent valuation).

Therefore, it is important when presenting results in an appraisal to be clear how far economic valuation captures the full range of relevant effects. Similarly, most valuation techniques will capture multiple welfare effects (which are currently uncertain), and isolating the value of each individual welfare effect will be difficult, if not impossible. See Annex B for more detail on the various methods and their potential limitations.

Further research is required to understand the degree to which double counting and biases are present within each method, and whether the welfare value captured in these methods reflects the diverse range of benefits including improvements to health, wellbeing and education. In many cases, valuation methods will measure a range of benefits that individuals may not be aware of, either for themselves or others.[footnote 55]

As such, methodologies are being developed and further tested, as outlined in Chapter 5. The CAVEAT: Triangulation of Methods project (part of the AHRC/DCMS Research Programme), is hoping to understand the extent of these overlaps, which methods are most appropriate in different scenarios, and what each valuation method is actually capturing. Due to the current limitations with valuation techniques, some mitigations should be taken:

-

Optimism Bias - evidence shows that analysis is often overly optimistic about the outcomes that will be delivered by an intervention. Adjustments for optimism bias should be applied to reflect the level of uncertainty in the data or assumptions used to derive the economic benefits, in line with HM Treasury’s approach. Tables 7A and 7B in Supporting public service transformation outline confidence grades for costs and benefits, respectively.

-

Sensitivity Analysis - to test potential variation in key variables and assumptions used within an appraisal. It can demonstrate, for example, the robustness of results, changes in key assumptions required to change the preferred option, or find the break-even point of an intervention.

DCMS previously published a Rapid Evidence Assessment (REA) of culture and heritage valuation studies to assess the current state of the literature on valuing culture and heritage assets, and to compile a collection of studies that align with best practice. Some of this work is summarised in Table 6, and includes the typical non-market valuation methods used, as well as examples of evidence forming part of the CHC Programme. Please note the list of techniques and papers is not exhaustive, and Table 6 only includes research that DCMS (or its ALBs) have been directly involved in. The majority of studies to date have focused on stated preference techniques. Future work in the CHC Programme will also address revealed preference methodologies, including hedonic pricing and travel cost methods.

Examples and lessons from other relevant and cutting-edge valuation studies from outside of the CHC Programme will be considered, such as the Natural Capital Programme or the value of data assets.[footnote 56] DCMS are keen to hear about other projects that might have been undertaken; please contact the CHC mailbox at chc@dcms.gov.uk.

Table 6: Examples of evidence of the value of Culture and Heritage Capital

4.4 Metrics

In order to develop a consistent approach to monetising the benefits associated with culture and heritage, it is important to have an agreed set of metrics against which each associated benefit can be measured, as set out in Section 4.1 (step 3). Metrics will be developed over time, working with the sector and academics.

Metrics will capture changes in volumes and benefits before valuation takes place. For example, measures of engagement, subjective well-being, identity, social cohesion, and employment will be considered. This is important as it may be not feasible for each outcome or benefit to be monetised, particularly in the early stages of the framework development. These metrics can still demonstrate the desired change has been achieved, before any valuation takes place.

DCMS will be looking to the AHRC and DCMS funded research project Developing a taxonomy for culture and heritage capital to further develop the discussion of appropriate metrics for measuring culture and heritage. DCMS work on metrics will also be informed by ESRC funded research to develop a UK National Cultural Data Observatory,[footnote 58] and Culture Connect: Open Access Data Observatory for Devolved Culture Informatics[footnote 59].

4.5 An introduction to Culture and Heritage Capital accounting

National accounts provide detailed, systematic and comparable quantitative measures of economic activities within a country. The most common headline indicator produced by national accounts is Gross Domestic Product (GDP). However, GDP does not provide adequate information about the sustainability of a country’s economy – because, for example, it does not take into account depreciation of capital stocks, or the welfare of its inhabitants. It only captures market prices and misses environmental externalities, such as the value of home production or leisure. The Office for National Statistics has already developed a set of UK Natural Capital Accounts that the Culture and Heritage Capital Programme will look to emulate, going Beyond GDP.

The methods used (including valuation methods) need to be consistent with the System of National Accounts (SNA) to be comparable with other countries’ accounts and extrapolated across the United Kingdom. Note that guidance for accounting from the SNA differs in important ways from the Green Book guidance for project or policy appraisal because these are different tools addressing different questions, as discussed in Chapter 4.

Culture and heritage accounts can provide a strategic overview of the state and value of culture and heritage assets.

In particular, accounts can:

-

raise awareness of the importance of culture and heritage assets which offer real value to the individuals, communities and the economy

-

identify evidence gaps and priority areas for investment

-

monitor culture and heritage outcomes over time, identify key trends and dependencies to support target setting and encourage greater accountability

-

generate physical and monetary indicators which can facilitate accountability and transparency with stakeholders relating to the benefit and funding of CHC assets

-

highlight the value of non-market benefits (including drivers and main beneficiaries), and enable aggregation and comparison of culture and heritage services and assets at a national level

-