Final report

Updated 22 March 2022

Applies to England, Scotland and Wales

Summary

The CMA launched a market study into children’s social care in England, Scotland and Wales on 12 March 2021, in response to 2 major concerns that had been raised with us about how the placements market was operating. First, that local authorities were too often unable to access appropriate placements to meet the needs of children in their care. Second, that the prices paid by local authorities were high and this, combined with growing numbers of looked-after children, was placing significant strain on local authority budgets, limiting their scope to fund other important activities in children’s services and beyond.

We considered that the case for a market study in this area was particularly strong due to the profound impact that any problems would have on the lives of children in care. While we have approached this study as a competition authority, assessing how the interactions of providers and local authority purchasers shape outcomes, we have been acutely aware of the unique characteristics of this market, and in particular the deep impact that outcomes in this market can have on the lives of children.

Our market study is also timely. Each of the 3 nations in scope has significant policy processes underway which are aiming to fundamentally reform children’s social care. For one vital element of this – the operation of the placements market – our study provides a factual and analytical background, as well as recommendations for reform. We intend that these will prove useful for governments as they develop their wider policy programmes for children’s social care.

Overall, our view is that there are significant problems in how the placements market is functioning, particularly in England and Wales. We found that:

- a lack of placements of the right kind, in the right places, means that children are not consistently getting access to care and accommodation that meets their needs

- the largest private providers of placements are making materially higher profits, and charging materially higher prices, than we would expect if this market were functioning effectively

- some of the largest private providers are carrying very high levels of debt, creating a risk that disorderly failure of highly leveraged firms could disrupt the placements of children in care

It is clear to us that this market is not working well and that it will not improve without focused policy reform. Governments in all 3 nations have recognised the need to review the sector and have launched large-scale policy programmes. A key part of these programmes should be to improve the functioning of the placements market, via a robust, well-evidenced reform programme which will deliver better outcomes in the future. This will require careful policymaking and a determination to see this process through over several years.

We are therefore making recommendations to all 3 national governments to address these problems. Our recommendations set out the broad types of reform that are necessary to make the market work effectively. The detail of how to implement these will be for individual governments to determine, taking into account their broader aspirations for the care system and building on positive approaches that are already in evidence.

Our recommendations fall into 3 categories:

- recommendations to improve commissioning, by having some functions performed via collaborative bodies, providing additional national support and supporting local authority initiatives to provide more in-house foster care

- recommendations to reduce barriers to providers creating and maintaining provision, by reviewing regulatory and planning requirements, and supporting the recruitment and retention of care staff and foster carers

- recommendations to reduce the risk of children experiencing negative effects from children’s home providers exiting the market in a disorderly way, by creating an effective regime of market oversight and contingency planning

In recognition of the different contexts in each of England, Scotland and Wales, we differentiate between these in the text of this document where appropriate. We also draw together the main conclusions and recommendations for each nation in its own dedicated summary, which will be published on our case page.

Background: the placements market

At the date of publication, there are just over 100,000 looked-after children in England, Scotland and Wales. Most are in foster care, with a smaller proportion in residential care settings including children’s homes, secure children’s homes, independent or semi-independent living facilities and residential schools. The current annual cost for children’s social care services is around £5.7 billion in England, £680 million in Scotland and £350 million in Wales.

Children’s social care is a devolved policy responsibility, with key policy decisions being made by the Scottish, Welsh and UK governments. Each nation has its own regulator which is responsible for inspecting children’s social care provision to ensure it is of the appropriate standard: Ofsted in England, and the respective Care Inspectorates in Scotland and Wales. Both fostering services and children’s homes fall within the regulators’ remits.

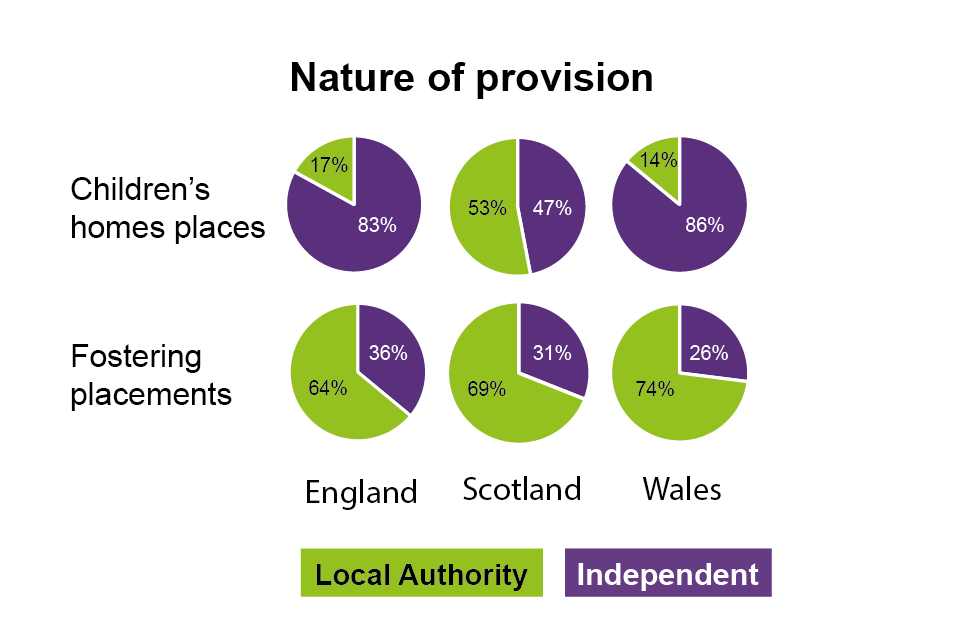

Local authorities in England, Scotland and Wales have statutory duties in relation to the children taken into their care. Local authorities are obliged to safeguard and promote children’s welfare, including through the provision of accommodation and care. In discharging their duties, local authorities provide some care and accommodation themselves, and they purchase the remainder from independent providers, some of which are profit-making. In general, local authorities rely more heavily on independent provision for residential placements than they do for fostering placements, and more in England and Wales than in Scotland.

Historically, children’s social care was largely provided either directly by local authorities using their own in-house provision, or by third-sector organisations working in partnership with the local authority. Over the past few decades, many local authorities and charities have reduced, or even ended, the provision of their own children’s homes. This was not due to a deliberate act of central policy, but rather to the independent decisions of hundreds of local authority and third-sector providers. While the reasons for this shift remain debatable, local authorities and advocacy bodies have told us that concerns around reputational risk following a number of scandals, as well as financial concerns, may have played a role in many of the relevant decisions.

In recent years, the number of looked-after children has increased steadily, both in absolute terms and as a proportion of the population. Between 2016 and 2020 the number of looked-after children rose 14% in England, and 27% in Wales, though it fell by 7% in Scotland. Needs were also shifting, with placements needed for a greater number of older children and unaccompanied asylum-seeking children, as well as those with more complex needs. These shifts have also increased demand for residential care and specialist fostering placements. We have seen an increasing gap between the number of children requiring placements and the number of local authority and third-sector placements available, particularly in England and Wales. Local authorities have placed increasing numbers of children in placements offered by private providers.

In children’s homes, over three-quarters of places in England and Wales now come from independent providers. In Scotland, this figure is lower but still substantial, with independent providers accounting for around one-third of placements. As well as shifting from local authority or voluntary sector to private provision, the average size of children’s homes has fallen. Most children’s homes now provide 4 or fewer places and there has been an increase in the number of single-bed homes.

In fostering, local authorities maintain their own in-house fostering agencies, but also use independent provision in the form of Independent Fostering Agencies (‘IFAs’). In England and Wales around 36% and 27% of foster placements, respectively, come from IFAs. In Scotland, IFAs provide around 31% of foster placements, but these are all not-for-profit providers, as for-profit provision is unlawful.

Finally, recent years have seen a significant increase in the use of “unregulated” placements in England and Wales, where children may be given accommodation and support, but not care, and which are not currently regulated by Ofsted or Care Inspectorate Wales. While local authorities sometimes use these placements by choice, to prepare older children to move towards independence, we understand that they have increasingly been used as a last resort to house children who the local authority wishes to place in a regulated placement but cannot find one.

Problems in the placements market

The placements market – the arrangements by which local authorities source and purchase placements for children – plays an important role in the provision of residential and fostering placements for children. As noted above, a significant proportion of placements are provided by private providers, particularly in children’s homes, and in England and Wales. Regulators assess most residential placements and fostering services as being of good quality, and there is no clear difference, on average, between their assessments of the quality of private provision, as compared with local authority provision.

Our study found problems in the way the placements market is operating. Children are not consistently gaining access to placements that appropriately meet their needs and are in the appropriate locations. Local authorities are sometimes paying too much for placements.

First, and most importantly, it is clear that the placements market, particularly in England and Wales, is failing to provide sufficient supply of the right type so that looked-after children can consistently access placements that properly meet their needs, when and where they require them. This means that some children are being placed in settings that are not appropriate for their own circumstances, for instance where they are:

- far from where they would call ‘home’ without a clear child protection reason for this, thereby separated from positive friend and family networks: 37% of children in England in residential placements are placed at least 20 miles from their home base

- separated from siblings, where their care plan calls for them to be placed together: 13% of all siblings in care in England were placed separately, contrary to their care plan

- unable to access care, therapies or facilities that they need: we were told consistently by local authorities in England, Scotland and Wales that it is especially difficult to find placements for children with more complex needs and for older children. We were also told that some children are placed in an unregulated setting due to the lack of an appropriate children’s home place, and so cannot legally be given the care they need. We also understand that in some cases children are being placed in unregistered settings, notwithstanding the fact that this is illegal

While the amount of provision has been increasing in England and Wales, primarily driven by private providers, this has not been effective in reducing difficulties local authorities face in finding appropriate placements, in the right locations, for children as they need them. That means, in tangible terms, children being placed far from their established communities, siblings being separated or placements failing to meet the needs of children, to a greater extent than should be the case.

Given the vital importance of good placement matches for successful outcomes for children, and particularly the negative impact of repeated placement breakdown, these outcomes should not be accepted. It is a fundamental failure in the way the market is currently performing.

Second, the prices and profits of the largest providers in the sector are materially higher than we would expect them to be if this market were working well. The evidence from our core data set, covering 15 large providers, shows that these providers have been earning significant profits over a sustained period. For the children’s homes providers in our data set we have seen steady operating profit margins averaging 22.6% from 2016 to 2020, with average prices increasing from £2,977 to £3,830 per week over the period, an average annual increase of 3.5%, after accounting for inflation. In fostering, prices have been steady at an average of £820 per week, and indeed have therefore declined in real terms, but profit margins of the largest IFAs appear consistently high at an average of 19.4%.

If this market were functioning well, we would expect to see existing profitable providers investing and expanding in the market and new providers entering. This would drive down prices as local authorities would have more choice of placements, meaning that less efficient providers would have to become more efficient or exit the market, and the profits of the largest providers would be reduced. Eventually, profits and prices should remain at a lower level as providers would know that if they raised their prices they would be unable to attract placements in the face of competition. The high profits of the largest providers therefore shows that competition is not working as well as it should be.

Third, we have concerns around the resilience of the market. Our concerns are not about businesses failing per se, but about the impact that failure can have on the children in their care. Were a private provider to exit this market in a disorderly manner – for instance by getting into financial trouble and closing its facilities – children in that provider’s care could suffer harm from the disruption, especially if local authorities were unable to find alternative appropriate placements for them. Given these potential negative effects on children’s lives, the current level of risk needs to be actively managed. This is less of a concern in the case of fostering, as foster carers should be able to transfer to a new agency with minimal impact on children. It is a greater concern in the case of children’s homes, where placements may be lost altogether.

We have seen very high levels of debt being carried by some of the largest private providers, with private equity-owned providers of children’s homes in our dataset having particularly high levels. This level of indebtedness, all else being equal, is likely to increase the risk of disorderly exit of firms from the market.

In addition to the above concerns about the market, some respondents have argued that the presence of for-profit operators is inappropriate in itself. We regard the issue of the legitimacy of having private provision in the social care system as one which it is primarily for elected governments to take a view on. Nonetheless we are well placed to consider the outcomes that private providers produce, as compared to local authority provision. While there are instances of high and low quality provision from all types of providers, the evidence from regulatory inspections gives us no reason to believe that private provision is of lower quality, on average, than local authority provision. Turning to price, our evidence suggests that the cost to local authorities of providing their own children’s home placements is no lower than the cost of procuring placements from private providers, despite their profit levels. By contrast, in fostering, there is indicative evidence that local authorities could provide some placements more cheaply than by purchasing them from IFAs. We have, therefore, made recommendations to governments to run pilots in certain local authorities to test the potential to make savings by bringing more fostering placements in-house. Finally, as noted above, we have seen that some private providers, particularly those owned by private equity investors, are carrying very high levels of debt. As local authorities need the capacity from private providers, but these providers can exit the market at any time, these debt levels raise concerns about the resilience of the market. We have, therefore, made recommendations to enable these risks to be actively monitored so that there is minimal disruption to children in care.

Given the importance of the functioning of the placements market for looked-after children, the problems we have found must be addressed. In the following 3 sections, we set out our findings on the main drivers of these problems, and the recommendations we are making to address them.

Commissioning

A key factor in determining how well any market functions is the ability of the behaviour of purchasers to drive the provision of sufficient supply at an acceptable price. The current shortfall in capacity in the placements‘ market therefore represents a fundamental failing in market functioning. In particular, we have found that there are severe limitations on the ability of the 206 local authorities in England, Scotland and Wales, who purchase placements, to engage effectively with the market to achieve the right outcomes.

In order to engage effectively with the market, local authorities, directly or indirectly, need to be able to:

- forecast their likely future needs effectively, gaining a fine-grained understanding of both the overall numbers of children that will be in their care, and the types of need those children will have

- shape the market by providing accurate and credible signals of the likely future needs of children to existing and potential providers, and incentivising providers to expand capacity to meet these needs

- procure placements efficiently, purchasing those places that most closely match the needs of children, in the most appropriate locations, at prices that most closely reflect the cost of care.

However, we have found that local authorities, across all 3 nations, face serious challenges when trying to do each of the above.

Individual local authorities face an inherently difficult task when trying to develop accurate forecasting. They each buy relatively few placements, and they experience significant variation in both the number of children requiring care and their specific needs. The absence of reliable forecasts means that there is greater uncertainty in the market than there needs to be. This acts as a barrier to investment in new capacity needed to meet future demand.

Even where future needs can be anticipated, local authorities struggle to convert this understanding into signals that providers will act on. Local authorities must often take whatever placement is available, even when it is not fully appropriate for the needs of the child. This blunts the ability of local authority purchasing decisions to shape the market to provide for their true needs. In England, Scotland and Wales, most local authorities told us that they do not attempt to actively shape the market by encouraging providers to invest in new provision. Local authorities acting alone face particular challenges in attempting to shape the market. For example, often the demand of an individual local authority for certain types of specialist provision is too low to justify contracting a whole service to meet these needs.

We have seen considerable evidence that working together can make local authorities more effective. Collaborative procurement strategies can strengthen the bargaining position of local authorities, and groups of local authorities can more effectively engage with private providers to support the case for investment in new capacity, which provides the right type of care in the right locations.

While we have seen varying degrees of cooperative activity between different groups of local authorities across the 3 nations, this has not gone far enough or fast enough. Despite regional collaboration being widely seen as beneficial the extent to which it takes place is patchy. Local authorities can struggle to collaborate successfully due to risk aversion, budgetary constraints, differences in governance, and difficulties aligning priorities and sharing costs. It is not clear how local authorities can sufficiently overcome these barriers even if given further incentive to do so. As such, without action by national governments to ensure the appropriate level of collaboration, local authorities are unlikely to be able to collaborate sufficiently to deliver the outcomes that are needed.

Recommendation 1.1: Larger scale market engagement

We recommend that governments in each nation require a more collective approach to engagement with the placements market. This should include:

- setting out what minimum level of activity must be carried out collectively. This should specify an appropriate degree of activity in each of the key areas of forecasting, market shaping and procurement

- ensuring there is a set of bodies to carry out these collective market shaping and procurement activities, with each local authority required to participate in one of them. While in Scotland and Wales it is plausible that this may be at a national level (building on the work of Scotland Excel and the 4Cs), we expect sub-national bodies to be appropriate for England

- providing an oversight structure to ensure that each body is carrying out its functions to the appropriate level. This should involve an assessment of the extent to which sufficiency of placements is being achieved within each area.

Each government should determine how best to implement this recommendation taking into account key issues that lie beyond the scope of our study. In examining the relative advantages and disadvantages of different options, governments should consider:

- the number of bodies: for any body or set of bodies created there will be a trade-off between gaining buyer power and efficiencies through larger size, versus difficulties of coordination and management that come with that. Governments should consider these factors in determining the appropriate approach

- what precise collective market shaping and procurement activities are assigned to the bodies: there is a range of options, from mandating only a small amount of supportive activity to be carried out collectively for example, forecasting, market shaping and procurement only for children with particular types of complex needs, through to mandating all of this activity to be carried out by the collective bodies

- the relationship between the new bodies and local authorities: national or regional bodies will decide on how the mandated level of collective activity is carried out. This could be with local authorities collectively reaching agreement or the regional bodies could be given the power to decide

- the governance of bodies: on the presumption that corporate parenting responsibilities (and therefore the ultimate decision of whether to place a particular child in a particular placement) will remain with local authorities, there may be a tension between the roles of the local authorities and the collective bodies that will need to be resolved via the governance structure

- how to best take advantage of what is already in place. There are benefits of building on existing initiatives in terms of avoiding transition costs and benefiting from organic learning about what works well in different contexts. For example, consideration should be given to using existing agreements, organisations and staff as the basis for future mandated collective action.

Wherever responsibility for ensuring there is sufficient provision for looked-after children sits, it is essential that these bodies are appropriately held to account. As such, we are also recommending that local authority duties should be enhanced to allow more transparent understanding of the extent to which sufficiency of placements is being achieved within each area. In order to do this, better information is required to understand how often children are being placed in placements that do not fit their needs, due to a lack of appropriate placements in the right locations. This will also help ensure that moving to a wider geographical focus helps support the aim of placing more children closer to home, unless there is a good reason not to do so.

Recommendation 1.2: National support for purchaser engagement with the market

We recommend that national governments provide additional support to local authorities and collective bodies for forecasting, market shaping and procurement.

With regards to forecasting, in each of England, Scotland and Wales, governments should establish functions at a national level supporting the forecasting of demand for, and supply of, children’s social care placements. These functions should include carrying out and publishing national and regional analysis and providing local authorities and collective bodies with guidance and support for more local forecasting, including the creation of template sufficiency reports.

For market shaping and procurement, each national government should support the increase in wider-than-local activity by funding collective bodies to trial different market shaping and procurement techniques and improving understanding of what market shaping and procurement models work well.

In England, the Department for Education should support the reintroduction of national procurement contracts covering those terms and conditions that do not need to reflect local conditions.

Recommendation 1.3: Support for increasing local authority foster care provision

We recommend that governments support innovative projects by individual local authorities, or groups of local authorities, targeted at recruiting and retaining more foster carers to reduce their reliance on IFAs.

While precise like-for-like comparisons are difficult to make, our analysis suggests that there are likely to be some cases where local authorities could provide foster placements more cost-effectively in-house rather than via IFAs, if they are able to recruit and retain the necessary carers. We have also heard from local authorities who have successfully expanded their in-house foster care offering and have seen positive results.

Governments should offer targeted funding support for innovative projects by individual local authorities, or groups of local authorities, targeted at recruiting and retaining more foster carers to reduce their reliance on IFAs. Any such projects should then be evaluated carefully to provide an evidence base to help shape future policy.

Recommendations we are not taking forward: banning for profit care; capping prices or profits

Some respondents have argued that we should directly address the problem of high profits and prices in the placements market by recommending that local authorities stop using private provision altogether, or that caps should be imposed on their prices or profits.

Turning first to children’s homes, as discussed above, we did not find evidence that providing local authority placements was any less costly to local authorities than purchasing placements from private providers. The central problem facing the market, especially in England and Wales, is the lack of sufficient capacity. At the moment, England and Wales relies on private providers for the majority of their placements. Similarly, most investment in new capacity is coming from private providers. Banning private provision, or taking measures that directly limit prices and profits, would further reduce the incentives of private providers to invest in creating new capacity (or even to maintain some current capacity) and therefore risk increasing the capacity shortfall. While this shortfall could be made up by increased local authority or not-for-profit provision, it would take significant political intervention to ensure that this was achieved at the speed and scale necessary to replace private provision, requiring very significant capital investment.

In the case of foster care, by contrast, we do see indicative evidence that using IFA carers may be more expensive for local authorities than using their own in-house carers in some cases. Compared to children’s homes, the capital expenditure required to in-source significant numbers of foster placements would also be lower. While we are recommending that governments support local authorities to explore this option, we do not recommend that governments take direct action to limit or ban profit-making in foster care. From the evidence we have seen is not clear that local authorities would be able to recruit the required number of foster carers themselves, nor that they would be able to provide the same quality of care at a similar price, across the full range of care needs and in every area.

While we are not recommending that governments directly limit for-profit provision, we are conscious that the Scottish and Welsh governments have each committed to move away from the model of for-profit provision in children’s social care. These decisions are rightly for democratically elected governments to make, and will involve considerations that go beyond our scope as a competition authority. Where governments do take this course of action, however, we recommend that they carefully consider the points we have raised as part of the planning, funding and monitoring involved in the process of directly restricting for-profit provision, to ensure that this is achieved in a way that does not inadvertently result in negative outcomes for children.

Overall recommended approach on commissioning

In our view, the best way to address the high levels of profit in the sector together with the capacity shortfall is to address the common causes of both problems, in particular the weak position of local authority commissioners when purchasing placements and removing unnecessary barriers to the creation of new provision (as discussed in the next section). Moving to a less fragmented approach to purchasing will provide local authorities with greater purchasing power and put them in a better position to forecast future demand and manage capacity requirements accordingly. Removing barriers to investment in new provision will help providers respond more effectively to the needs of children.

Over time, we believe that these measures would be successful in drawing more appropriate supply to the market and driving down prices for local authorities, without acting as a drag on required ongoing and new investment in provision. In doing so, they would move the market to a position where providers are forced to be more responsive to the actual needs of children, by providing places which fully meet their needs, in locations which are in the best interests of those children. Such placements ought also to offer better value to commissioners who are purchasing them, by being priced more in line with the underlying cost of provision.

We are aware that there have been calls in the past for greater aggregation in commissioning. In England, reviews for the Department for Education in 2016 and 2018 recommended that local authorities be required to come together in large consortia to purchase children’s homes and fostering placements, and that larger local authorities or consortia attempt to become self-sufficient using in-house foster carers. Similar issues have been raised in Scotland, including around the potential for children’s social care to be included within a National Care Service, and in Wales.

Each of the governments will rightly wish to consider our recommendations, and the appropriate way to implement them in the round, taking into account broader issues that are beyond our remit. Nonetheless, we are clear that excessive fragmentation in the processes of forecasting, market shaping and procurement are key drivers of poor outcomes in this market, and must therefore be addressed if we are to see significant improvement in the outcomes from this market.

Creating capacity in the market

We have also identified barriers that are reducing the ability of suppliers to bring new supply to the market to meet emerging needs. These barriers are in the areas of:

- regulation

- property and planning

- recruitment and retention.

By creating additional costs and time delays for providers, these factors may act as a deterrent to new investment, leading to provision being added more slowly, or even deterred completely. Unless addressed, over time, these will contribute to the ongoing undersupply of appropriate placements in the market.

Recommendation 2.1: Review of regulation

We recommend that the UK Government carries out or commissions a review of regulation impacting on the placements market in England.

Regulation is a vital tool to protect safety and high standards, and where it is well-designed to protect the interests, safety and wellbeing of children, it must not be eroded. We have seen evidence that in England there are areas where regulation is a poor fit for the reality of the placements market as we see it today. Despite the huge changes in the nature of the care system over the past 20 years, the regulatory system in England has remained broadly the same over this period.

For example, in England it is a legal requirement for a children’s home to have a manager. It is also a legal requirement for a manager to be registered and failure to do so is an offence. On that basis, Ofsted policy is that an application to register a home will be accompanied by an application to register a manager. This means that the manager usually has to be in place for some time before children will be cared for. Similarly, in England a manager’s registration is not transferable, so each time a manager wishes to move home they must re-register with Ofsted. We have heard from providers that these processes are costly, time-consuming and hinder the rapid redeployment of staff to a location where they are needed.

These are examples of the sort of areas where regulation as currently drafted may be preventing the market from working as well as it should, without providing meaningful protections for children. As a result, the net effect of these areas of regulation on children’s wellbeing may be negative. We have seen less evidence of these sort of problems in Wales and Scotland, where regulation appears to be more flexible, while still providing strong protections for children in care.

The UK Government should carry out, or commission, a thorough review of regulation relating to the provision of placements, during which protecting the safety and wellbeing of children must be the overriding aim, but also considering whether specific regulations are unnecessarily restricting the effective provision of placements. In Scotland and Wales, the regulatory system has been amended more recently, but governments should be aware of these considerations as they move through their respective policy processes to reshape the children’s social care system.

Recommendation 2.2: Review planning requirements

We recommend that the UK and Welsh governments review the impact of the planning system on the ability of providers to open new children’s homes.

Access to suitable property is another barrier to the creation of new children’s homes. While this is partly down to competition for scarce housing stock, one particular area of concern is in negotiating the planning system. We have repeatedly heard concerns that in England and Wales, obtaining planning permission is a significant barrier to provision because of local opposition, much of which appears to be based on outmoded or inaccurate assumptions about children’s homes and looked-after children. Similarly, we have heard that the planning rules are applied inconsistently in relation to potential new children’s homes.

The average new children’s home provides placements for only 3 children. As a result, the type of properties that are suitable to serve as children’s homes will also tend to be attractive to families in general. Where providers face delays imposed by the planning process, even where they are successful in getting planning permission, this can lead to them losing the property to a rival bidder for whom planning is not a consideration. It is therefore clear to us that market functioning would be improved by a more streamlined and consistent approach to planning issues.

In England and Wales, governments should review the planning requirements in relation to children’s homes to assess whether they are content that the correct balance is currently being struck. In particular, in order to make the planning process more efficient for children’s homes, we recommend that governments consider whether any distinction, for the purposes of the planning regime, between small children’s homes and domestic dwelling houses should be removed. This could include, for example, steps to make clear that small children’s homes which can accommodate less than a specified number of residents at any one time are removed from the requirement to go through the planning system notwithstanding that the carers there work on a shift pattern. Doing this will increase the prospect of enough children’s homes being opened and operated in locations where they are needed to provide the level of care that children need.

We also recommend that where children’s homes remain in the planning system (for example because they are larger) national guidance is introduced for local planning authorities and providers. The guidance should clarify the circumstances in which permission is likely to be granted or refused.

Recommendation 2.3: Regular state of the sector review

We recommend that each government commissions an annual state of the sector review, which would consider the extent and causes of any shortfalls in children’s home staff or foster carers.

Recruiting and retaining staff for children’s homes is a significant barrier to the creation of new capacity. This is a fundamental problem across all the care sectors. Given the high levels of profit among the large providers it is perhaps surprising that wages have not risen to ease recruitment pressure and that greater investment is not made in recruiting, training and supporting staff. We note, however, that there are many other factors aside from wages that impact on the attractiveness of roles within children’s social care, some of which are outside the control of providers. While there is no easy route to addressing this, more attention needs to be paid to this question at a national level. This should be an ongoing process building on existing work.

In each nation there should be an annual assessment of the state of the sector, including workforce issues, to provide a clear overview of staffing pressures and concerns, and to recommend measures to address bottlenecks. This would be similar in scope to the CQC’s annual State of Care review in England. Governments should also give attention to whether national measures, such as recruitment campaigns, measures to support professionalisation (such as investment in training and qualifications) and clearer career pathways are required.

Recruitment and retention of foster carers is a barrier to creating more foster places. While many local authorities and IFAs are adopting positive approaches to addressing this, again more can be done at the national level. In each nation there should be an assessment of the likely future need for foster carers and national governments should take the lead in implementing an effective strategy to improve recruitment and retention of foster carers.

Resilience of the market

We have found that some providers in the market, particularly those owned by private equity firms, are carrying very high levels of debt. These high debt levels increase the risk of disorderly firm failure, with children’s homes shutting their doors abruptly. Were this to occur, this would harm children who may have to leave their current homes. Local authorities may then have problems finding appropriate alternative provision to transfer them into.

In principle, a successful children’s home should be expected to be attractive to a new proprietor. There is, however, no guarantee that it will be sold as a going concern in every case. In particular, the expected move away from the ultra-low interest rate environment of recent times would place new pressure on highly-leveraged companies to meet their debt servicing obligations, increasing the risk of disorderly failure. Our assessment is that the current level of risk of disruption to children’s accommodation and care as a result of a provider’s financial failure is unacceptable, and measures must be taken to mitigate this.

In considering our recommendations in this area, we have taken into account the ongoing need for investment in the creation of appropriate placements, and the current level of reliance on private providers to make this investment, in particular in England and Wales. We have sought to balance the need to take urgent steps to reduce the level of risk to children against the need to avoid a sudden worsening of the investment environment faced by providers, which may exacerbate the problem of lack of appropriate supply in this market.

We are therefore recommending that governments take steps to actively increase the level of resilience in this market, in order to reduce the risk of negative outcomes for children. In particular, we recommend that they:

- introduce a market oversight function so that the risk of failure among the most difficult to replace providers is actively monitored

- require all providers to have measures in place that will ensure that children in their care will not have their care disrupted in the event of business failure.

Recommendation 3.1: Monitor and warn of risks of provider failure

We recommend that governments create an appropriate oversight regime that is capable of assessing the financial health of the most difficult to replace providers of children’s homes and of warning placing authorities if a failure is likely.

This regime could operate along similar lines to the Care Quality Commission’s (CQC) current market oversight role in relation to adult social care providers in England – a system that already exists for a similar purpose. Adopting this recommendation would provide policymakers and placing authorities with early warning of a potential provider failure.

Creating this function on a statutory basis would provide benefits such as giving the oversight body formal information-gathering powers, and a firmer footing on which to share information with local authorities. We recommend that in England, where the CQC already operates a statutory regime for adult social care, the statutory approach should be adopted. Due consideration should also be given to adopting a statutory approach in Scotland and Wales. Given the cross-border nature of many of the most significant providers, oversight bodies in the 3 nations need to be able to share relevant information in a timely and effective way.

Recommendation 3.2: Contingency planning

We recommend that governments take steps to ensure that children’s interests are adequately protected if a provider gets into financial distress.

Governments, via their appointed oversight bodies, should require the most difficult to replace providers to maintain a “contingency plan” setting out how they are organising their affairs to mitigate the risk of their provision having to close in a sudden and disorderly way in the event that they get into financial difficulties or insolvency. One important element will be to ensure that appropriate arrangements are in place to ensure that providers have the necessary time and financial resources to enable an orderly transition where the provision can be operated on a sustainable basis, either by its existing owners or any alternative owners. Contingency plans should seek to address these risks, for instance through ensuring that:

- appropriate standstill provisions are in place with lenders

- companies are structured appropriately to remove unnecessary barriers to selling the provision to another operator as a going concern

- providers maintain sufficient levels of reserves to continue to operate for an appropriate length of time in a stressed situation

These contingency plans should be subjected to stress testing by the government’s oversight body, to ensure that they are sufficiently robust to reduce the risk of negative impacts on children in potential stress scenarios. Where the oversight body considers that plans are not sufficiently robust, it should have the power to require providers to amend and improve them.

Taken together, we believe that these measures strike the right balance between minimising the risks of negative impacts on children and maintaining an environment that supports needed investment in the future, based on the current state of the market. As the measures that we are recommending take effect and capacity grows in the market, governments will however want to reflect on the appropriate balance between public and private provision In particular, as well as the resilience risks associated with the high levels of debt inherent in the business models of some providers, there is a risk that excessive reliance on highly leveraged providers will leave local authorities more susceptible to having to pay higher prices for services if the costs of financing debt increase.

In addition, as reforms to the care system are made (possibly resulting in fewer children being placed in children’s homes) the basis of this calculation may shift, meaning that imposing tougher measures, such as a special administration regime or steps to directly limit or reduce the levels of debt held by individual operators, may at that point be appropriate.

Next steps

If implemented, we expect that our recommendations should improve or mitigate the poor outcomes that we see in the placement market.

- Our recommendations in relation to commissioning placements in the market will put purchasers in a stronger position to understand their future needs, to ensure that provision is available to meet them and to purchase that provision in an effective way

- Our recommendations to address barriers to creating capacity in the market will reduce the time and cost of creating new provision to meet identified needs

- Our recommendations around resilience will reduce the risk of children experiencing negative effects from children’s home providers exiting the market in a disorderly way

Taken together, we expect these measures to lead to a children’s social care placements market where:

- the availability of placements better matches the needs of children and is in appropriate locations

- the cost to local authorities of these placements is reduced

- the risk of disruption to children from disorderly exit of children’s homes provision is reduced

Major policy processes in relation to children’s social care are currently ongoing in England, Scotland and Wales, and we hope that our recommendations will be considered as part of each. We will engage with policymakers, regulators and others to explain our recommendations, strongly encourage them to implement them and, support them in doing so.

1. Background

Purpose of the market study

In light of concerns around high prices and a lack of appropriate placements for looked-after children, on 12 March 2021 we launched a market study into the supply of children’s social care services in England, Scotland and Wales, specifically considering residential services and associated care and support, and fostering services. The purpose of the market study was to examine how well the current system is working across England, Scotland and Wales, and to explore how it could be made to work better, to improve outcomes for some of the most vulnerable people in our society.

Progress of the market study

Our invitation to comment set out the scope of the market study and the key themes we intended to focus on, namely: the nature of supply, commissioning, the regulatory system and pressures on investment. On 20 May 2021 we published 37 responses to the invitation to comment on our Children’s social care study case page.

On 9 September 2021 we published our decision not to make a market investigation reference.

We published our interim report on 22 October 2021, setting out our interim findings based on our initial analysis. This set out our concerns that the children’s social care sector is failing to consistently deliver the right outcomes for children and society, in that:

- the placements market overall is not providing sufficient appropriate places to ensure that children consistently receive placements that fully meet their needs, when and where they require them

- some prices and profits in the sector are above the levels we would expect in a well-functioning market

- some of the largest providers have very high levels of debt so that there is a potential risk that external events such as a tightening of credit conditions, could lead to unforeseen and significant market exit, significantly increasing the difficulties local authorities face in finding placements for children in their care

On 26 January 2022 we published 32 responses to our interim report on our case page, and we have carefully considered the responses we received.

Information gathered

Over the course of the market study we have gathered information from a wide range of sources to develop our understanding of the issues under consideration and the children’s social care sector more broadly, to assess outcomes in the sector in terms of the availability of appropriate places, prices paid by local authorities and the resilience of the sector, and to test our thinking on what recommendations may be appropriate. In addition to analysing the responses to our consultations, our information gathering activities included the following:

- We engaged with, and examined data held by, national governments in England, Scotland and Wales and the regulators in those nations

- We issued detailed information requests to, and received responses from, the 15 largest independent providers of children’s homes and fostering services and received 27 responses to our questionnaire issued to smaller providers

- We received responses from 41 local authorities to our initial questionnaire. We received responses from a further 4 local authorities when we issued additional questionnaires focussed on specific themes, and a combined response on behalf of Foster Wales and All-Wales Heads of Children’s Services

- We met with a range of parties involved in or with an interest in the sector, including: children’s commissioners, local authorities and their representative bodies; commissioning consortia and commissioning bodies; independent providers and their representative bodies; and private equity firms

- After publishing our interim report, we held 4 roundtables, focussed on commissioning (from a local authority perspective), commissioning (from an independent providers’ perspective), barriers to opening new provision and resilience of the sector

- We analysed a dataset compiled from the financial accounts of children’s social care providers filed with Companies House

- We visited a number of local authority and independent-owned children’s homes, speaking with staff and with children in their care

- We considered previous reviews and research reports that have examined the children’s social care sector

Structure of the final report

This final report on the market study sets out our findings and makes recommendations to address the issues we have identified during our market study.

The remainder of the report is structured as follows:

- Section 2 provides an overview of the children’s social care sector

- Section 3 describes the outcomes we have observed in the market, focussing on quality, supply of appropriate places, prices and resilience

- Section 4 sets out our findings on commissioning and our recommendations to improve commissioning

- Section 5 sets out our findings on barriers to creating capacity and our recommendations on how to reduce them

- Section 6 sets out our findings on resilience of the market and our recommendations on how to reduce the risk of disorderly provider failure having negative effects on children

- Section 7 provides a summary of our recommendations, describes how they will work together and sets out our approach to supporting their implementation.

In addition, further detail is provided in 2 appendices to the report:

- Appendix A sets out in detail the financial analysis we have undertaken

- Appendix B provides detail of aspects of the legal frameworks in England, Scotland and Wales which are relevant to the issues we have considered in the market study

2. Overview of the sector

This section provides an overview of the children’s social care sector – which is a devolved policy area – in England, Scotland and Wales and highlights some of the key differences in the policy, legislative and regulatory frameworks in each nation. It also considers how the sector has evolved over time.

Ensuring children live in safe, caring and supportive homes

All children need a safe, caring and supportive home and the children’s social care system exists to ensure that all children have access to one. For many children in the care of a local authority (‘looked-after children’) in England, Scotland and Wales, this is provided by foster carers and, for a smaller group, by children’s homes. In some circumstances, in England and Wales, children may be placed in unregulated accommodation: independent or semi-independent living facilities which provide support but not care. Children are often looked after for a short period of time or there may be a longer-term arrangement, and children may be looked after in different care settings at different times in their lives.

For these looked-after children – some of the most vulnerable people in our society – the state, through local authorities who act as corporate parents, is responsible for providing their accommodation, care and support. It does this in 2 main ways: local authorities may use their own in-house foster carers, children’s homes and, in some circumstances, unregulated accommodation or they procure these services from independent (private and voluntary) providers. Local authorities tend to use their own services as their first choice where appropriate local authority placements are available.

The necessity of ensuring that children receive accommodation and care as the need arises creates challenges for local authorities in terms of how they purchase placements. Time pressure can be immense as children may require placements urgently, often in response to a crisis. The requirements can vary considerably from case to case, due to the particular needs and circumstances of the child. The local authority must therefore seek the best option from among those placements that are available, often during a limited time period.

Children’s social care sector in England, Scotland and Wales

"

Six pie charts showing the nature of provision in England, Scotland and Wales.

- Independent providers of children’s homes places account for 83% in England, 47% in Scotland and 86% in Wales

- Local Authority provision of children’s homes places account for 17% in England, 53% in Scotland and 14% in Wales

- Independent providers of fostering placements account for 36% in England, 31% in Scotland and 26% in Wales

- Local Authority provision of fostering placements account for 64% in England, 69% in Scotland and 74% in Wales

"

A description of the policy context in England, Scotland and Wales.

- In England: Children’s social care system under review, through Independent Care Review

- In Scotland: Implementation of The Promise following independent review of children’s social care, including intention to eliminate for profit provision

- In Wales: Commitments made in the Programme for government 2021 to 2026, including intention to eliminate private profit

"

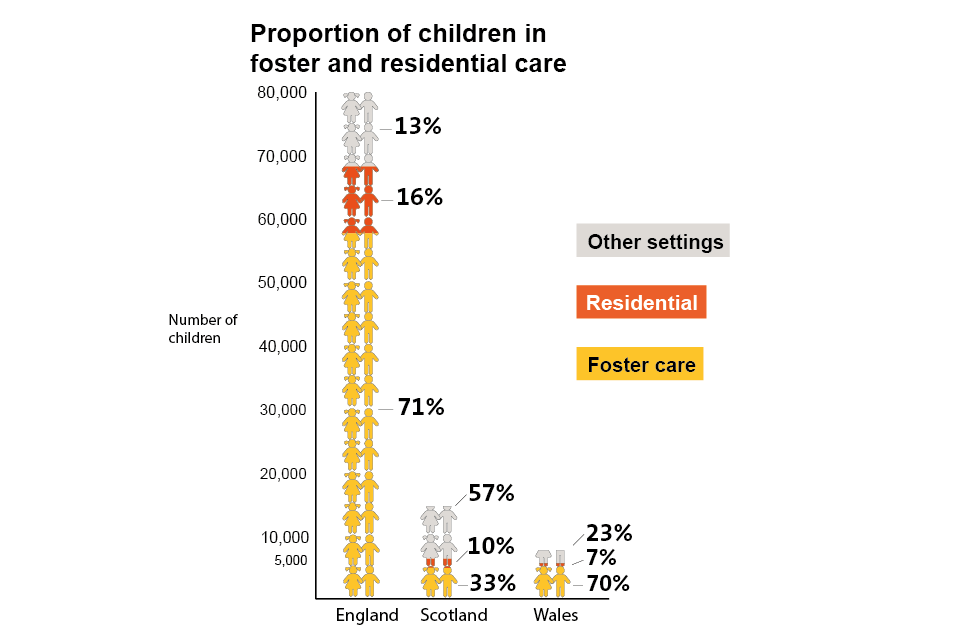

A bar chart showing the proportion of children in foster and residential care in England, Scotland and Wales.

- In England the total of children in care is 80,080. 71% are in foster care; 16% are in residential care; and the remaining 13% are in other settings

- In Scotland the total of children in care is 14,458. 33% are in foster care; 10% are in residential care; and the remaining 57% are in other settings

- In Wales the total of children in care is 7,170. 70% are in foster care; 7% are in residential care; and the remaining 23% are in other settings

Notes: In the chart showing the proportion of children in care, the 57% of children in ’other settings’ in Scotland, represents a broader definition of care than is applied in England and Wales. In the pie chart showing foster placements in Scotland, the independent providers are wholly not-for-profit.

Sources: as for tables 1, 5 and 6 below.

Looked-after children

There are currently just over 100,000 looked-after children in England, Scotland and Wales. Foster care is the most common form of care setting for these children in England and Wales: over two-thirds of looked-after children in England and Wales live in foster care; around a third of looked-after children in Scotland live in foster care.[footnote 1] 16% percent of looked-after childe ren live in residential settings in England, 10% in Scotland and 7% in Wales. Such settings include children’s homes, secure children’s homes, independent or semi-independent living facilities and residential schools. The remainder of looked-after children live in a variety of settings, for example, living with parents, placed for adoption or in other community settings.

Table 1: Children in care in fostering and residential settings in England (2021), Scotland (2020) and Wales (2021)

| Numbers of looked after children | England | Scotland | Wales |

|---|---|---|---|

| In foster care | 57,330 (71%) | 4,744 (33%) | 5,075 (70%) |

| In residential settings | 12,790 (16%) | 1,436 (10%) | 535 (7%) |

| In other settings | 11,850 (13%) | 8,278 (57%) | 1,655 (23%) |

| Total | 80,850 | 14,458 | 7,265 |

Notes: For England, the relevant file is ‘National - Children looked after at 31 March by characteristics’. Residential settings including secure units, children’s homes, semi-independent living accommodation, residential schools and other residential settings. Other settings include other placements, other placements in the community, placed for adoption and placed with parents or other person with parental responsibility.

For Wales other settings include placed for adoption, placed with own parents or other person of parental responsibility, living independently and absent from placement or other. In Scotland, other settings include at home with parents, with kinship carers, with prospective adopters and in other community. Sources: England: DfE Children looked after in England including adoptions. Scotland: Scottish Government Children’s social work statistics. Wales: StatsWales Children looked after at 31 March by local authority and placement type.

Table 2 below shows disproportionately high rates of children being taken into care among Black and Mixed ethnicity children and disproportionately low rates for Asian and White children in England.

Table 2: Percentage of looked-after children and percentage of under-18 population in England by ethnicity (England)

| Ethnic group | Looked-after children | Under-18 population |

|---|---|---|

| Asian | 4% | 10% |

| Black | 7% | 5% |

| Mixed ethnicity | 10% | 5% |

| Other ethnic groups | 4% | 1% |

| White | 74% | 79% |

Source: DfE, Adopted and looked-after children - GOV.UK Ethnicity facts and figures

Table 3 below shows a disproportionately high rate of children being taken into care among Mixed ethnicity children and a disproportionately low rate for Asian children in Scotland.

Table 3: Percentage of looked-after children and percentage of all children in Scotland by ethnicity (Scotland)

| Ethnic group | Looked-after children | All children in Scotland |

|---|---|---|

| Asian, Asian Scottish or Asian British | 1% | 3% |

| Black, Black Scottish or Black British | 1% | 1% |

| Mixed ethnicity | 2% | 1% |

| Other ethnic background | 1% | 0% |

| White | 84% | 95% |

Note: For 11% of looked-after children ethnicity is not known. Source: Children’s social work statistics: 2019 to 2020 - gov.scot, Table 1.2

Table 4 below shows a disproportionately high rate of children being taken into care among children from Mixed ethnic groups and a disproportionally low rate among Asian children in Wales.

Table 4: Percentage of looked-after children and percentage of all children in Wales by ethnicity (Wales)

| Ethnic group | Looked-after children | All children in Wales |

|---|---|---|

| Asian / Asian British | 2% | 3% |

| Black / African/Caribbean / Black British | 1% | 1% |

| Mixed / multiple ethnic group | 4% | 2% |

| Other ethnic group | 1% | 1% |

| White | 91% | 93% |

Source: Children looked after at 31 March by local authority and ethnicity and Data Viewer - Nomis - Official Labour Market Statistics

Children may become looked after for a number of reasons including as a result of abuse or neglect, family dysfunction, parental illness or disability and absent parenting, as well as where they arrive in the UK as unaccompanied asylum seekers.

The number of children entering children’s social care has increased over time, and we have been told by a number of parties including local authorities and independent providers that the needs of such children have grown and become more complex.[footnote 2] There are also increasing numbers of older children being looked after.[footnote 3]

The Institute for Government(PDF, 4.2MB) projected in its 2021 Performance Tracker that demand for children’s social care would grow by around 5% between 2019 to 2020 and 20204 to 2025, driven by increasing demand for foster and residential placements.[footnote 4] The Social Market Foundation (PDF, 852KB) projected that, in England, ‘based on the growth seen in the last 5 years, we could expect that close to 77,000 children will be in foster care by 2030; an increase of more than 30% from now.’[footnote 5] However, we note that while demand for children’s social care services is widely expected to grow, there are ongoing efforts to reduce the number of looked-after children, which makes it difficult to predict the level and profile of future demand with a high degree of certainty. For example, in September 2021 the Scottish Government announced as part of its latest Programme for Government a fund to significantly reduce the number of children and young people in care by 2030.[footnote 6]

Local authorities

Local authorities have statutory duties in relation to the children taken into their care. Given this is a devolved policy area, these vary across England, Scotland and Wales, as set out in Appendix B.

Local authorities are obliged to safeguard and promote the welfare of children in their care, including through the provision of accommodation and care. Where it is in the child’s best interests, this should be provided locally in order to ensure continuity in their education, social relationships, health provision and (where possible and appropriate) contact with their family.

A “sufficiency duty” is placed on local authorities in England, whereby local authorities are required to take steps to secure, so far as reasonably practicable, sufficient accommodation within the local authority’s area which meets the needs of the children it looks after. Similar duties apply in Wales. In Scotland, local authorities and the relevant health boards are required to produce strategic plans (Children’s Services Plans) every 3 years.[footnote 7]

Each local authority is responsible for providing, either themselves or by purchasing from another provider, the placements they require.

In terms of how local authorities approach procurement a 2020 Independent Children’s Homes Association (ICHA) survey found that a large proportion of children’s home placements (51%) are spot-purchased not from a framework. In such cases the terms for each placement are determined on an individual basis. The survey found that in 47% of cases, local authorities purchase placements using framework agreements, which set out the terms (such as the service offered and the price) under which the provider will supply the relevant service in the specified period. A much smaller number of placements (2%) are block contract placements.[footnote 8] A further ICHA survey in November 2020 found a higher level of block arrangements, with such arrangements accounting for almost 1 in 5 placements.[footnote 9] The National Association of Fostering Providers (NAFP) told us that the majority of foster care placements ‘are made with pre-tendered contractually defined relationships albeit with no commitment to make any placements with a particular provider’.[footnote 10]

There are different approaches to commissioning and purchasing in each nation:

- There is no national commissioning body in England. The National Contracts Steering Group (NCSG) – comprising the Local Government Association (LGA), a group of local authority commissioners, independent providers and trade associations – was established over a decade ago, supported by the Commissioning Support Programme. It developed 3 national contracts for placements in schools, foster care and children’s homes. However, the work of the NCSG ended when the Commissioning Support Programme came to an end, as discussed further in Section 4. Of the 152 relevant local authorities in England, some procure individually, while many form regional procurement groups with neighbouring local authorities. These groups vary in their design and purpose.

- Scotland Excel is a public sector organisation operating on behalf of Scotland’s 32 local authorities. It undertakes strategic commissioning of services and provides a wide range of national contracts for local authorities in Scotland, including contracts for the provision of fostering services and children’s residential care. It is up to individual local authorities whether they secure placements through Scotland Excel, and not all local authorities do so for every placement they require.

- In Wales, all 22 local authorities are members of the Children’s Commissioning Consortium Cymru (4Cs). Since 2018 the Framework Agreements for both residential and foster care have been reviewed – the All Wales Residential Framework was launched in 2019 and the All Wales Foster Framework launched in April 2021.[footnote 11]

Role of the market and nature of provision

In addition to local authorities making placements through their own in-house provision (where that is available), the market plays a significant role in the allocation of care placements that can be purchased by local authorities from private and voluntary providers.

Table 5 below shows that in England and Wales, the largest proportion of children’s home places are provided by the private sector – around 78% and 77% respectively. In contrast, in Scotland only around 35% of places are provided by the private sector.

Table 5: Number of children’s home places by provider type and nation

| Provider type | England | Scotland | Wales |

|---|---|---|---|

| Private provision | 7,555 | 362 | 769 |

| Voluntary provision | 501 | 130 | 89 |

| Local authority provision | 1,643 | 556 | 144 |

Sources: England: Main findings: children’s social care in England 2021. Scotland: Children’s social work statistics: 2019 to 2020. Wales: Invitation to comment response: Care Inspectorate Wales.

The majority of fostering placements are provided by local authority foster carers – 64% in England, 69% in Scotland and 74% in Wales, as illustrated by table 6 below. However, a significant minority are provided by private providers (except in Scotland where for-profit provision is not permitted) and voluntary providers.

Table 6: Number of children in foster care by provider type and nation

| Provider type | England (2021) | Scotland (end 2020) | Wales (2021) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent provision | 20,065 | 1,436 | 1,330 |

| Local authority provision | 35,925 | 3,151 | 3,745 |

Note: “Independent provision” refers to care which is not provided by local authorities.

Sources: England: Ofsted: Official Statistics Release, Capacity_and_occupancy_2014-21_ tab. Scotland - Care Inspectorate: Fostering and adoption 2020-21 A statistical bulletin, Figure 1.12. Wales - Children looked after in foster placements at 31 March by local authority and placement type

Development of the market for care placements

While today the majority of children’s homes places in England and Wales and a significant minority of fostering placements are provided by the private sector, this has not always been the case.

Historically, children’s social care was provided by charitable institutions, until the state took on responsibility in the twentieth century. As well as providing accommodation and care through voluntary providers, local authorities established their own in-house provision. However, the private sector has become increasingly involved in the provision of care over the years.

There have been a number of explanations as to why the sector has evolved in the way it has. For example:

- The ICHA told us that, in 1991, when the introduction of the Children’s Homes Regulations 1991 was being discussed in Parliament, the Secretary of State said ‘It is not part of our policy to see an explosion in the number of private children’s homes. We know that the trend is moving away from children’s homes of any kind towards fostering and adoption.’ The ICHA notes, however, that with the introduction of the 1991 regulations, local authority homes began to close, ‘as compliance with the regulations required significant investment, and private provision began to increase.’[footnote 12]

- Research carried out on behalf of the Local Government Association in 2021 observes that the current scale of private provision compensates ‘for a decline in provision by local authorities and the voluntary sector who have both greatly reduced their residential care home provisions over the past 30 to 40 years (much of which has been repurposed as short break provision).’[footnote 13]

- Children England highlighted ‘the almost complete withdrawal of charities from their formerly dominant role.’[footnote 14] While it has been suggested that fear of reputational damage in light of historical abuse scandals has deterred the return of the voluntary sector at scale,[footnote 15] Children England notes a range of reasons for the withdrawal of the voluntary sector from residential care.[footnote 16]

In more recent times there have been shifts in the nature of provision. Looking at these by nation:

- For England, Ofsted figures show that over the last 5 years, the private sector has increased its number of children’s homes by 26%, while the number of local authority homes has declined by 5%, and that the voluntary sector is very small and in decline.[footnote 17]

- Care Inspectorate Scotland (CIS) data shows that in Scotland, the private sector’s share of children’s homes increased from 33% in 2014/15 to 45% in 2021, the voluntary sector’s share decreased marginally from 21% in 2014/15 to 20% in 2021, and local authorities’ share reduced from 46% in 2014/15 to 34% in 2021.[footnote 18]

- The Care Inspectorate Wales (CIW) provided data showing that in Wales, the private sector’s share of children’s homes increased very slightly from 78% in 2014 to 81% in 2021, the voluntary sector’s share of homes increased from 4% in 2014 to 6% in 2021 and local authorities’ share of homes reduced from 18% to 13% over the same period.[footnote 19]

The reasons for these trends are not fully clear and are likely to be the result of a variety of factors. For example, CIS said that ‘the reasons for changes in provision over the last decade are nuanced, with a combination of local and national factors, changing needs and interdependencies contributing to a landscape that is not homogenous.’[footnote 20]

In relation to fostering, The Fostering Network, which operates across the UK, told us that it had seen a considerable rise in the number of independent foster providers in its membership over the years, reflecting the expansion of the independent fostering sector in that time.[footnote 21]

Looking at recent trends by nation the picture appears relatively stable:

- In England, since 2016 the total number of approved foster places has increased by 2%. There were 86,195 approved foster places at March 31 2016 of which 63% were local authority places and 37% IFA places. At March 31 2021, there were 88,180 approved places, of which 60% were local authority places and 40% IFA places.[footnote 22]

- In Scotland, where it is illegal for commercial for-profit firms to provide foster care, since 2016 the total number of approved foster care households has decreased by 11%. There were 3,970 approved foster care households as at 31 December 2016 of which 70% were local authority foster care households and 30% were approved by independent fostering services. As at 31 December 2020, there were 3,540 approved foster care households, of which 69% were local authority foster care households and 31% were approved by independent fostering services.[footnote 23]

- In Wales, since 2016 the total number of children looked after in foster placements has increased by 19%. There were 4,250 children looked after in foster placements as at 31 March 2016 of which 74% were with a relative or friend, or with a foster carer provide by a local authority and 26% with a foster carer arranged through an agency. As at 31 March 2020, there were 5,070 children looked after in foster placements with the same proportion with a foster carer arranged through an agency as in 2016.[footnote 24]

More broadly, we observe that there has been a move towards the provision of more kinship care – where children are cared for by wider family and friends - in Scotland and Wales.[footnote 25]

It would therefore appear that the placements market as it operates today is not the result of deliberate policy choices by national governments on how children’s social care should be delivered, but rather a reaction by multiple local authorities, voluntary providers and private providers to a range of factors – including regulatory developments, financial constraints and reputational risk – that have played out over time. Children England noted that ‘there was not a decisive point in time, nor any clear policy intervention, by which a ‘competitive market’ for procuring childcare was introduced…Competitive procurement and contracting has simply evolved over time as the predominant mechanism used in meeting children’s care needs today.’[footnote 26]

In the next section we describe significant policy developments in England, Scotland and Wales that have the potential to affect how the placements market evolves.

Policy context

Local authority expenditure for looked after children in England in 2020 to 2021 was £5.7 billion.[footnote 27] In Scotland, the annual cost in 2019 to 2020 was around £680 million.[footnote 28] In Wales, the cost for children looked after services in 2020 to 2021 was around £350 million.[footnote 29]

All 3 governments are engaged in significant policy processes to consider wider issues relating to children’s social care.

- In England, the Independent review of children’s social care published its case for change in June 2021. The Review will publish its final recommendations later this year.

- In Scotland, the findings of The Promise – Independent care review(PDF, 819KB) are being taken forward by The Promise Scotland. In 2021 it published its Change Programme ONE and Plan 2021 to 2024. In August 2021 The Scottish Government launched a consultation on a National Care Service (NCS) in Scotland, following on from the Feeley review of adult social care. Amongst other questions, the Scottish Government sought views on whether the NCS should include both adults and children’s social work and care services.

- In Wales, commitments around protecting, re-building and developing services for vulnerable people were made in the Programme for government 2021 to 2026. In October 2021, following consultation on its White Paper on Rebalancing care and support(PDF, 685KB), the Deputy Minister for Social Services said in a Written Statement that she is committed to introduce a strategic National Framework for care and support which would set standards for commissioning practice, reduce complexity and rebalance commissioning to focus on quality and outcomes. A ‘National Office’ for social care will be established to oversee implementation.

Both the Scottish Government and Welsh Government have expressed an intention to remove profit-making from the provision of care to looked-after children, as is already the case for fostering agencies in Scotland.

Regulatory environment

Children’s social care provision is highly regulated and each nation has its own statutory framework, regulations and guidance applicable to the sector. Where relevant, we draw out key differences in this report.

Broadly, as well as statutory duties placed on local authorities with regard to children in their care (as discussed above) the regulatory frameworks in each nation aim to protect and promote the welfare of children and young people. They do this through registration requirements, setting standards and inspection regimes which are intended to ensure children are safe and receive appropriate levels of care.