The future of working age contributory benefits for those not in paid work

Updated 12 September 2023

About this report

This project was conducted as part of the Social Security Advisory Committee’s independent work programme, under which the Committee investigates pertinent issues relating to the operation of the benefits system.

As ever, we are grateful to our extensive stakeholder community for their engagement with this project and, in particular, to the individuals who have shared their direct and personal experiences of the benefits examined in this report. We are also grateful for the assistance of our secretariat, and to operational staff, policy officials and Research Librarians from the Department for Work and Pensions who provided factual information. We also thank staff at the Department for Communities (Northern Ireland) and G4S for their help with our evidence gathering.

The views expressed and recommendations presented in the report are solely those of the Committee.

Chair’s foreword

Contributory benefits for working age families have historically played a significant role within the social security system. However, as a policy area they have been neglected for some time. The contributory principle has diminished in importance as the role of other working age benefits has increased, for example with the expansion of means-tested support for families with children, renters, and in-work support.

The introduction of Universal Credit offered an opportunity for a root and branch reform. Either by removing entirely the contributory principle from out-of-work support for working-age individuals, relying solely on means-tested support; or through the integration of contributory support into Universal Credit, so that an enhanced offer would be made to those meeting certain contributory criteria.

However, that opportunity was not seized, and neither path of action of was followed. This means that New Style Jobseeker’s Allowance and New Style Employment and Support Allowance exist in a largely unreformed guise alongside Universal Credit. But the debate about contributory benefits and their principle has not gone away. If anything, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the vital role that some form of income protection can play for those who do not fall within the bounds of means-tested support.

For as long as contributory out-of-work benefits remain part of the social security system, there is a compelling case that the quality of administration and support provided should be at least comparable to that provided by Universal Credit, especially in terms of access to job support. While there was a pragmatic argument for accepting these differences as Universal Credit is rolled out, the argument to retain such disparities, as part of a longer-term design, is less persuasive. We therefore urge the Secretary of State to consider committing to longer-term alignment of the experience of those on New Style benefits with Universal Credit claimants as part of the Government’s programme of social security reform.

There is a range of options for achieving greater alignment, from operational level change that would deliver access to Universal Credit technology and unifying work coaches for those on dual claims, through to delivery on the same platform and full integration of working-age benefits.

While the decision about the role of the contributory principle is one for the Government, it is appropriate that Ministers clearly articulate the role that they want this historically-important component of working-age social security to play in the 21st century. We appreciate that such reforms can take time and are not the most immediate development priorities. However, we would welcome commitment to make early discrete operational changes, with a clear statement of longer-term intent to provide claimants and wider stakeholders with a clear direction of travel.

Dr Stephen Brien

Executive summary

For the past decade, the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) has focussed on introducing Universal Credit nationwide, as it moves claimants of six individual working age means-tested benefits onto one. This has been a huge challenge, amounting to the largest single change to the UK’s working age benefits system since Beveridge.

It is perhaps understandable then that the two contributory working-age benefits for those unable to work – New Style Jobseeker’s Allowance (NS JSA) and New Style Employment and Support Allowance (NS ESA) – have received considerably less attention over this period. However, this also represents the most recent phase of a long running trend. Successive Governments have allowed these benefits to wither away quietly rather than develop a considered strategy for what used to be the most substantial element of the UK benefits system. This is explicitly referenced in the 2010 Universal Credit White Paper Welfare That Works, which states[footnote 1]:

Governments have wrestled with what to do with the contributory principle for working-age benefits ever since the Beveridge system was introduced.

Then, when referring to what it describes as piecemeal reforms that limited the role of contributory working age benefits for those unable to work, it continues:

These proposals are consistent with that direction of travel and recognise the fact that we need to allocate limited resources where they will have the best effect.

More people claim – and Government spends more on - means-tested benefits than contributory benefits. There has been relatively little attention given to contributory benefits such as New Style ESA and New Style JSA. Yet the experience of the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting lockdowns highlighted the importance of New Style JSA in particular as the number of new claims more than doubled in the space of just three months[footnote 2].

In an earlier piece of work we did with the Institute for Government, we looked at some of the long-term issues that COVID-19, and the associated lockdowns, raised for social security policy[footnote 3]. One of the things that our report, Jobs and Benefits: the COVID-19 challenge, highlighted was the extent to which the reward from having paid into the system via National Insurance contributions had reduced over the past eight decades.

The report concluded saying:

Finally, we would note that the recommendations here to strengthen contributory benefits are modest. There is a case, which we would urge the government carefully to consider, for going appreciably further – without necessarily moving wholesale to the earnings-related systems that are common in Western Europe and Scandinavia.

Following on from the Committee’s earlier study, our latest research provides a more detailed analysis of the two current contributory benefits for working age people who are not in paid work, and makes recommendations to the Government where improvements can be made.

How we approached this

Our research looked at published statistics and literature, and we spoke to expert stakeholders at two roundtable discussions. The data used in the findings mainly result from a series of interviews with staff from the DWP in Great Britain and the Department for Communities (DfC) in Northern Ireland, as well as claimants from across England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. We also undertook a small-scale survey of claimants.

Our report provides a history of contributory benefits from 1945 to the current day. We explain how, after changes introduced by various governments (of different political parties), we have moved from a mainly contributory benefits system with a means-tested safety net, to one that is mainly means-tested with a much smaller contributory element.

This has often occurred in response to changing challenges. For example, the rising cost of rent led to the introduction of targeted support for housing costs. Increased means-testing has also occurred as a response to other changing factors, such as increased worklessness and the rise in numbers of single parent households.

Perhaps the most pertinent example of this with regards to contributory benefits is the considerably increased complexity in disability and incapacity benefit, with means-tested support also playing an increasing role, reflecting a growing recognition of the additional costs of long-term disability and sickness.

The move towards greater means-testing concluded with the introduction of Universal Credit. This was intended to reduce complexity within the social security system by combining six means-tested working-age benefits and remove all contributory benefits from the unemployment benefit system. In practice some contributory out-of-work benefits were kept by the creation of New Style JSA and ESA.

These have however, shrunk in importance and visibility as Departmental energy has, understandably, been focussed on successfully rolling out Universal Credit. This history of contributory benefits is the focus of Chapter 2 of this report.

This paper also illustrates the context and policy thinking from the time that New Style benefits were introduced, up to today. The Universal Credit White Paper acknowledges the difficulty faced by successive governments in creating a long-term strategy for contributory benefits. It concedes that New Style benefits are the latest incarnation in a policy trend of shrinking contributory benefits scale and importance within the benefit landscape[footnote 4].

The decline of the contributory principle in unemployment benefit has, in recent decades, taken place alongside a fall in public support for the amount of public money spent of benefit, with this reaching a low point in the early 2010s[footnote 5]. In more recent years however, this trend has begun to reverse, with public support for such spending returning to levels last seen in the early 1990s.

Around the point of lowest public support for welfare spending, which coincided with the publication of the publication of the Universal Credit White Paper[footnote 6], a renewed appreciation for the notion of contribution emerged among some scholars. In 2012 Bell and Gaffney argued that enhancing the contribution principle could improve public attitudes to welfare by diminishing the “something for nothing” perception provoked by means-testing[footnote 7].

In the past decade several think tanks and research bodies have suggested possible structures for a re-invigorated contributory unemployment benefit system. The think tanks Policy Exchange[footnote 8] and Centre for Social[footnote 9] Justice have suggested variations of privately administered insurance against job loss. The Resolution Foundation, on the other hand, proposes a publicly provided and funded benefit that provides much greater levels of income replacement for a limited period, more similar to models used in Scandinavia[footnote 10].

The recent context and current policy thinking around contributory benefits for those not in paid work is the subject of Chapter 3.

In Chapter 4, we set out how New Style JSA and New Style ESA operate in practice. Here we identify some aspects potentially in need of reconsideration. First, how contributions made over two recent financial years are measured. Second, the means-tests of New Style ESA and New Style JSA against receipt of some private pension income which are in need of review in an era of “pension freedoms” for those with defined contribution pensions. Third, the National Insurance credits awarded to those in receipt of a New Style benefit and how these differ from those awarded to some in receipt of Universal Credit.

Our report seeks to develop an understanding of how New Style JSA and New Style ESA currently operate in practice and therefore where they are currently performing well and where the system needs to be improved.

The findings and recommendations from our research seek to answer the following questions:

- How DWP distinguishes between those who have paid into the system and those on means-tested support?

- What is the typical journey onto the New Style benefits, and can more be done to promote / enable take-up?

- Is the National Insurance contributions requirement to qualify appropriate or are some individuals unfairly excluded?

- How do New Style benefits work in conjunction with Universal Credit and what is the interplay between them?

- What is the claimant experience of starting, receiving and ending a claim for New Style benefits?

Our Findings

Elements that have been working well

We found many examples of contributory benefits working well in terms of being administered effectively with a good service being provided to claimants. Those who had claimed an unemployment benefit before often stated that the service provided for their current claim was far better. One claimant of New Style ESA told us:

I think the service is far better now, the Jobcentre staff were really respectful and professional compared to when I claimed decades ago. When claiming income support in the past, I was as treated like a bit of dirt. Of the DWP and DfC staff we spoke to, a respectful and often compassionate attitude towards claimants was the norm. Most of the claimants we spoke to were aware of the time limit for the benefit that they were receiving, and those in receipt of JSA were highly motivated to return to work prior to that point and generally confident that they would do so.

Areas for Improvement

Our study has identified a number of areas where the quality of service provided to those receiving these contributory benefits falls short of what should be delivered and where the service is not administered as efficiently as it could be.

New Style is analogue

We found that the largely non-digital nature of the two New Style benefits does not make full use of websites, emails, texts and other technology to make it easier for people. It still relies a lot on paper. This potentially means that more limited and less effective services are offered to claimants of New Style benefits; and inefficiencies and poor services arising from the inability of the systems to interact with Universal Credit.

Organisational focus on Universal Credit

There has been a focus on Universal Credit, which has contributed to a lack of investment in the New Style systems. Universal Credit has been the priority at all levels within the DWP. Within DWP there is a consensus that Universal Credit has been the priority, from director through to administrative level.

Understanding outside of area of immediate expertise

Pre-COVID, DfC had a member of staff who greeted those entering the Jobcentre. This person would identify the customer’s requirements and direct them to the right place. Staff said the knowledge of the first member of staff to interact with a prospective claimant was important in ensuring a smooth journey onto the benefit. At the time this research was conducted, this post did not exist, and staff were concerned that this would lead to less straightforward customer experiences. We found examples of staff signposting customers to a helpline, for fear of providing advice that might be inaccurate. One person we spoke to described this in terms of removing culpability for providing incorrect information. It is clear that all too often there was a risk that out of work people who were potentially entitled to JSA or ESA were not told they could claim it.

Utility of work-based support offer

Claimants of both New Style JSA and New Style ESA sometimes found the support to help them return to paid work was ineffective. For New Style JSA claimants this could mean poor or non-existent targeting of support. For New Style ESA claimants, generally very little was expected with regards to work-related activity requirements, indeed there was understandably a much lower level of appetite for work. However, for some, there was a genuine desire to move into paid work within the confines of their condition. Some in this group, felt that they were being discouraged from doing the types of work open to them.

Work coach perception of JSA claimants

The lack of support felt by some claimants could be in part explained by the work coach perception of the customer. Across Great Britain and Northern Ireland, work coaches perceived New Style JSA claimants as being keen to move into paid work, requiring relatively little input from them. At times this appeared to lead to a more hands-off approach with New Style JSA claimants, with a view that these claimants did not need the support, and were actively uninterested in it. One exception within the group of New Style JSA claimants were older people within a few years of the state pension age, particularly in Northern Ireland. Here staff reported there could be a sense of entitlement to support without a requirement to engage with any work search requirements.

Work coach perception of ESA claimants

For New Style ESA claimants the picture was quite different. Staff tended to view such claimants with much compassion, and they were much more likely to express a lenient attitude towards claimant commitments (for those in the work-related activity group). The focus here tended to be on making payment. However, as noted above, our research suggests this might have disadvantaged some New Style ESA claimants who did wish to find work. Very few references were made to any potential benefit to New Style ESA claimants from finding appropriate work by staff interviewed as part of this research.

Variation in practice

During our discussions with staff from different operational sites, we found evidence of a large variation in the practices between Jobcentres. It seems possible – perhaps even likely – that these will have led to some claimants receiving a consistently better service throughout their time on the benefit than others. As most of the variation in practice evidenced in this report occurred in validating work search activity, New Style JSA claimants appear to be disproportionately affected. However, that is not to say ESA claimants are not affected, and as noted earlier, ESA claimants as a population may be more vulnerable to negative unintended consequences in practice.

Contribution requirements

There is a potential deficiency in the way contributions requirements are measured to determine eligibility for New Style benefit. These are supposed to reflect whether contributions have been recently made, yet because of the design of how these are measured, for someone who became unemployed in December 2021 their work and contribution history for the previous 21 months is discounted (as the assessment would be based on their activity in 2018-19 and 2019-20). This also underpins concerns that those with certain employment types can have claims turned down due to seasonal work patterns. Though we recognise contribution requirements can be relaxed in some cases e.g., where one has been in receipt of Carer’s Allowance in the previous tax year, this does not address the issue around seasonal work patterns. This also opens questions around the fairness of a contribution system that prioritises a specific two-year window of contribution. If an individual has an unbroken record for 30 years, followed by two years where fewer contributions were made, should they then be excluded from claiming these contributory benefits?

Recommendations

Recommendation 1

That the Government sets out a clear articulation of what it wants the two New Style benefits to provide and the extent to which those deemed to have paid into the system should be able to access support on a preferential basis to those qualifying for means-tested support.

Having set out its strategy for these benefits they should also be renamed to reflect their role better, as the name “New Style” will not convey that to claimants. For example, their legal names, contributory ESA and contribution-based JSA, could instead be used.

Recommendation 2

We recommend the long-run goal of New Style policy should be to integrate both New Style JSA and New Style ESA into Universal Credit.

Recommendation 3

All claims for Universal Credit should be automatically assessed for entitlement to New Style JSA / New Style ESA.

Recommendation 4

For dual claimants of both UC and NS benefit, the Universal Credit system should measure – and then adjust automatically in response to changes in – receipt of New Style benefits.

Recommendation 5

New Style payments should be automatic, requiring the work coach to intervene to reduce or stop payment if a claimant breaches their agreement.

Recommendation 6

New Style JSA should be assessed and paid monthly, the same as Universal Credit.

Recommendation 7

New Style JSA claimants should automatically receive National Insurance credits when they reach the time limit for benefit payment.

Recommendation 8

Review the National Insurance credits awarded to claimants of Universal Credit and to claimants of New Style benefits with a view to crediting both in the same way.

Recommendation 9

Contributory requirements to qualify for New Style benefits should be reviewed and reassessed.

Recommendation 10

The means-tests against some private pension income in New Style ESA and New Style JSA should be reviewed in the light of “pensions freedoms” with a view to removing them.

Recommendation 11

Ensure a professional level of customer service and support that considers the claimant’s situation in an accurate/consistent/prompt way.

Recommendation 12

Those on New Style benefits should be entitled by default to access all of the employment programmes available to those on Universal Credit.

Recommendation 13

When a claimant moves from New Style to Universal Credit they should, by default, keep the same work coach unless it is explicitly decided that a change could be beneficial.

Recommendation 14

Provide appropriate and tailored employment support for JSA and ESA claimants following initial assessment of needs.

Recommendation 15

The Department should adopt a Universal Credit style of journal for New Style claimants.

Chapter 1: Introduction

New Style Employment and Support Allowance (NS ESA) and New Style Jobseeker’s Allowance (NS JSA) are out-of-work working-age benefits that sit alongside Universal Credit. They are distinct from Universal Credit in that, generally, they are not means-tested. In very broad terms eligibility for New Style benefit is dependent upon being out of paid work, and having made sufficient National Insurance contributions in the relevant two financial years prior to the point at which the claim is made. Unlike Universal Credit, eligibility for New Style benefits is not dependent on the level of household savings, or the earnings of a partner.

Over the longer-term the trend has clearly been for these contributory benefits to be made less generous in an attempt to restrain the overall working-age benefits bill. As we stated in a report carried out jointly with the Institute for Government and published last year:

…for those of working-age, the reward for paying what used to be known as ‘the stamp’ – i.e. National Insurance Contributions (NICs) – has shrunk over the years as the social security system has become more means-tested and more conditional. Indeed, one contributor at the webinar suggested that there is a view in DWP, particularly since the arrival of Universal Credit, that the contributory benefits are an irritating anachronism that should be dispensed with. Given their small size, there is a case for that. But there is also a case the other way. There remain some advantages for claimants of contribution-based JSA. Unlike Universal Credit, it is an individual benefit, not a household one, so a partner’s income does not affect entitlement – and there are no savings rules. That means it can help significantly reduce the fall in household income where a partner is still in paid work.[footnote 11]

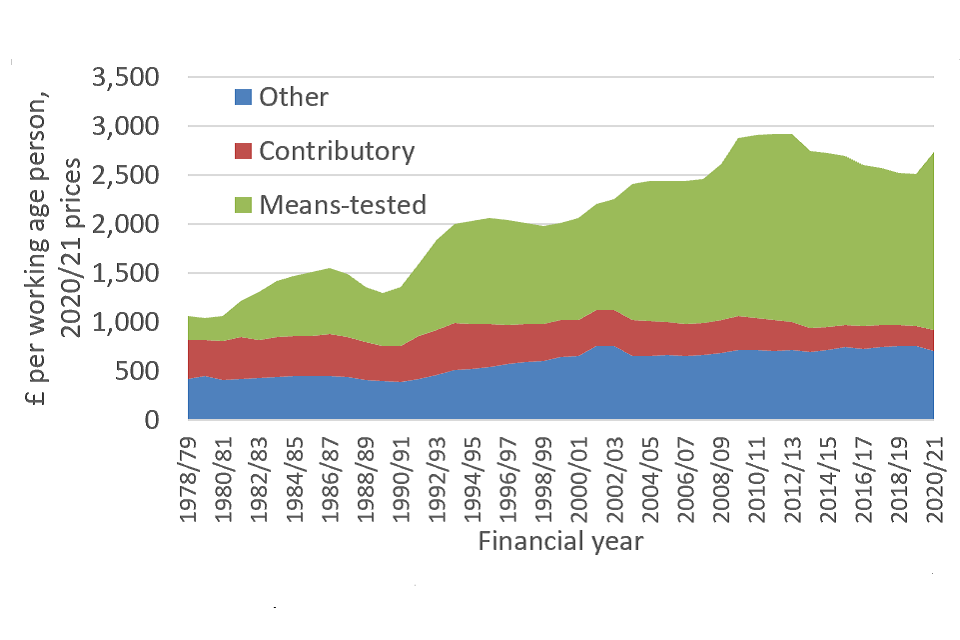

The relative decline of the importance of contributory working age benefits is shown in Figure 1. In 1978-79, for every £1 the then Government spent on means-tested benefits £1.63 was spent on working age contributory benefits. By the eve of the pandemic this relationship had more than flipped: in 2019-20 for every £1 spent on contributory benefits £8.74 was spent on means-tested benefits.

Figure 1. Spending per person on working age benefits, 1978–79 to 2019–20

Source: Hoynes, H., Joyce, R. and Waters, T. (forthcoming). “The transfer system”, in IFS Deaton Review: Inequalities in the 21st Century.

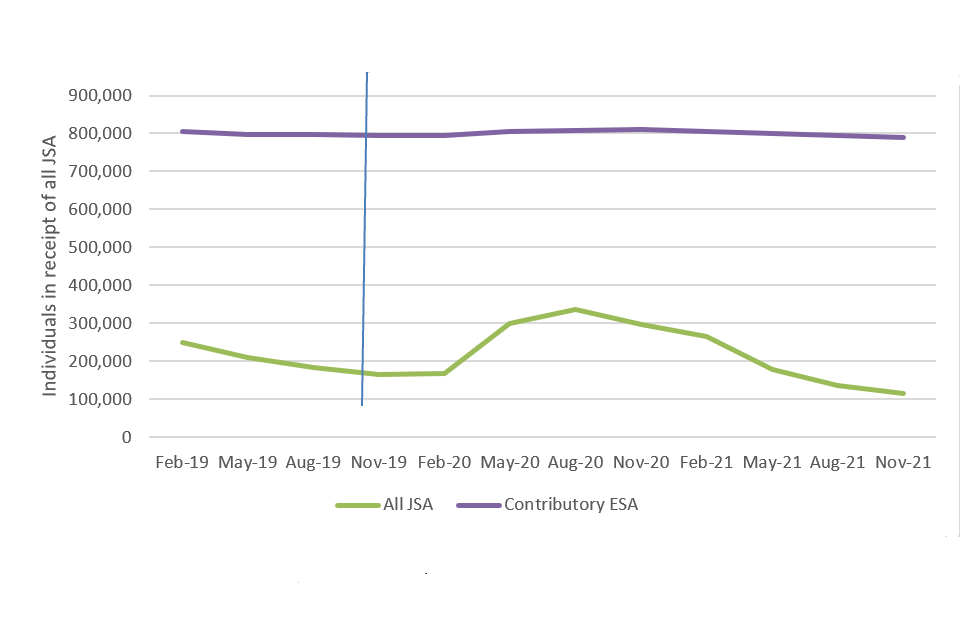

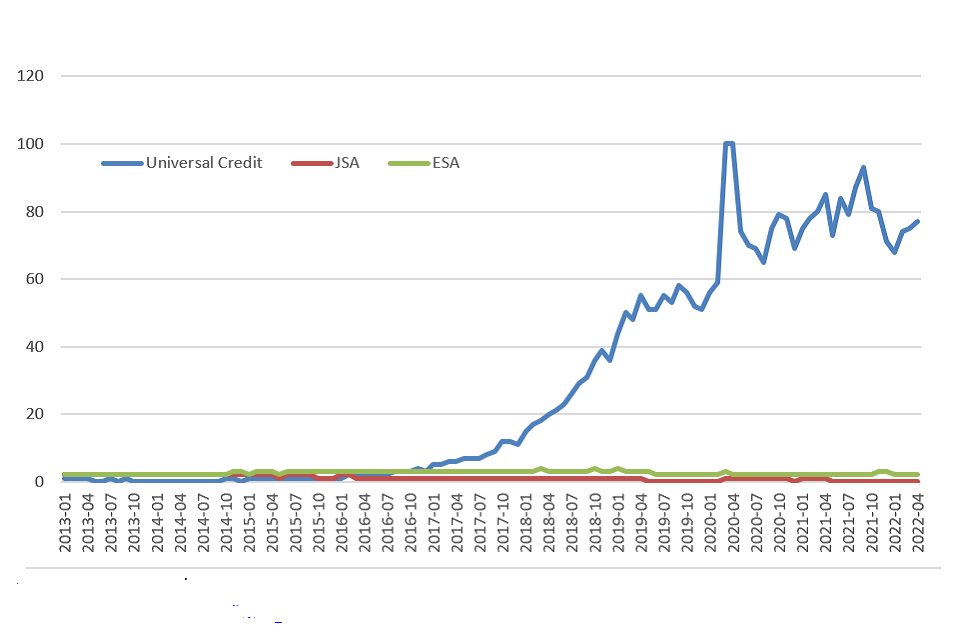

Despite this reduction in generosity, contributory benefits became relevant during the COVID-19 pandemic in a way that they had not been for decades, with some households turning to the benefits system for the first time ever. As shown in Figure 2, the volume of people accessing JSA more than doubled at the start of the pandemic before returning to pre-pandemic levels in August 2021. Given that new claims to income-based JSA stopped from February 2019 onwards (with these individuals instead claiming Universal Credit), this increase was entirely driven by claims to New Style JSA.

A similar pattern was not seen for contributory ESA claims, which appear to have been unaffected by the pandemic. It is not entirely clear why this was the case, although it could suggest those who became unemployed due to the pandemic generally did not qualify for ESA. One alternative explanation is that individuals who might otherwise have moved onto ESA instead moved onto JSA, as it does not require a health assessment, and work search requirements usually required for JSA were eased during lockdown, removing a barrier for those whose health meant they were unable to engage in work search activities.

Figure 2. Caseload for all JSA, and contributory ESA

Note and source to Figure: caseloads calculated using stat Xplore data from February 2019 Monthly caseload data onwards. Contribution based ESA group uses legacy contribution-based ESA and New Style ESA data. All JSA group uses legacy income based JSA and New Style JSA data.

As shown in Table 1 below, the combined Great Britain caseload for individuals in receipt of New Style benefits for the financial year 2020/21 were around 13% of the total households in receipt of Universal Credit. The caseload in Northern Ireland is very different. Although we only have a snapshot for Northern Ireland, we can see that the caseload for New Style ESA is almost equal to that of the Universal Credit household caseload. This is a long running trend, rather than an effect of the pandemic.

Table 1. Numbers claiming New Style benefits and Universal Credit

| Benefit Type | Great Britain caseload (2020/21) | Northern Ireland caseload (November 2021) |

|---|---|---|

| New Style JSA | 156,000 | 9,000 |

| New Style ESA | 384,000 | 110,000 |

| Total New Style JSA and ESA (individuals) | 540,000 | 119,000 |

| Universal Credit (households) | 4,052,000 | 117,000 |

| Universal Credit (individuals) | 4,846,000 (estimate) | 133,000 |

Note on source of Table 1: data for GB from DWP Autumn forecast 2021 and Stat-Xplore. Data for Northern Ireland from DfC benefit statistics Summary November 2021. Individuals in receipt of UC for GB estimate calculated taking monthly household and individual claimant outturn data for 2020/21 from Stat-Xplore, calculating the difference between these, and applying to Autumn forecast figures for 2020/21 household outturn. All data rounded to nearest thousand[footnote 12].

Given the increased importance of New Style JSA in the pandemic, we considered it timely to examine how well the two New Style benefits are delivering to claimants. The importance of this is highlighted by findings from The Heath Foundation at the University of Salford, which estimates 0.7% (around 290,000 individuals) of the UK working age population had unsuccessfully attempted to claim either Universal Credit, New Style JSA or New Style ESA between March 2020 and August 2020[footnote 13]. It observes that 20% of claims failed as they were never completed or were retracted as the claim was no longer required. Removing these from the equation, 90% (around 140,000 individuals) of remaining claims failed because household earnings or savings were too high. However, this would only preclude an individual from claiming Universal Credit, not New Style benefits. Crucially, the study estimates that of those rejected from Universal Credit due to partner earnings or savings being too high, just under two thirds – i.e., a majority – did not consider applying for New Style ESA or JSA, for which they might have been eligible. These findings could imply a failure in signposting claimants towards appropriate support.

Alongside the increased importance of New Style JSA in the pandemic, it is also the case that Universal Credit – which provides means-tested support to working age households – is now fully rolled out to all new claims across the United Kingdom. The factors led us to conclude that a review of the two New Style benefits, their purpose in the 21st Century labour market and the efficacy with which they are operating, particularly in conjunction with Universal Credit, was overdue.

Our study therefore seeks, at least in part, to redress this – and will hopefully lead to others, both inside and outside government, putting greater thought into the role these New Style benefits could – and should – play and what improvements ought to be made. In particular, we consider the following research questions:

1. Does the DWP distinguish between those who have “paid into” the system and those on means-tested support in the way it delivers and thinks about insurance and means-tested benefits? If it does not then should it recognise a distinction, and if so, how? For example, does the support provided by / requirements imposed by work coaches differ for those on Universal Credit, and if so, are these supports appropriately set?

2. How do individuals end up on New Style JSA and New Style ESA and should more be done to promote and enable take-up among those who are entitled (for example those applying for Universal Credit and being turned down on the basis of their financial assets or their partner’s earnings) and, if so, what?

3. Are the National Insurance contribution requirements to qualify appropriate or are some individuals excluded for reasons that may be considered inappropriate? For example, as noted by the Taylor Review, the self-employed are not able to move onto New Style JSA[footnote 14].

4. To what extent do individuals tend to flow from New Style benefits onto Universal Credit (perhaps having been timed out on these benefits or due to moving into low paying work) and does this process work well?

5. What is the claimant experience of the process of starting, receiving and ending a claim for New Style benefits?

Across all areas of examination, we consider whether the system is performing as well as it could be and whether any aspects of it might be improved either for claimants or indeed for those administering the system.

Evidence for this report is predominantly based on qualitative evidence collected through eight semi-structured interviews and 12 focus groups, through which we spoke to 19 claimants of one of the New Style benefits and 29 operational staff from the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), Department for Communities (DfC) and G4S. The report also draws evidence from 16 respondents to a small-scale claimant survey, quantitative data analysis using various published statistics and evidence from two roundtable discussions – the first with non-government organisations that seek to support claimants and a second with think tanks and others with experience in social security policy design and administration.

Chapters 2 and 3 of this report look at the history of contributory benefits designed to support those who have moved out of paid work in the UK, how we have moved to the current predominantly means-tested system and evidence on what the current system is trying to achieve. Chapters 4 and 5 look at how the current system is designed to work, and whether it is currently working well. Chapter 6 identifies the need for a long-term strategy for New Style benefits and provides recommendations for how to improve the current system.

Chapter 2: How did we get here?

Prior to the introduction of Universal Credit in 2013, contribution-based JSA and contributory ESA sat alongside their means-tested counterparts within the same policy framework, simply known as JSA and ESA. The means-tested elements of JSA and ESA were gradually subsumed into Universal Credit from 2013 onwards. The contributory elements remained separate and were newly branded as New Style benefits.

Since 2013, New Style benefits have taken a backseat as the policy focus of the DWP has – for understandable reasons – been on the nationwide roll-out of Universal Credit for new claimants. Caseloads of claimants on Universal Credit vastly outstrip those on New Style benefits, as does the overall amount spent on support through the two systems[footnote 15]. This focus is also true in terms of monitoring and evaluation activity. However, there has been a renewed interest in the contributory principle as a potential means to restore confidence in an often publicly maligned benefits system[footnote 16].

This landscape has also changed somewhat. First, Universal Credit is now fully rolled out for all new claimants across the UK. Second, following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and the first UK-wide economic lockdown, caseloads of New Style JSA increased dramatically in the space of a few weeks. Though caseloads have now fallen below pre-pandemic levels, the experience of COVID-19 highlights the role that a system of support targeted at those not covered by means-tested support can provide. Given these factors it seems timely to consider how effective these benefits are, how easy or otherwise it is to claim them, how well they are operating alongside Universal Credit across the UK, and how they can be made fit for a post-pandemic future.

A brief history of contributory out-of-work benefits

Contributory Unemployment Benefit (UB) and contributory Sickness Benefit (SB) were a cornerstone of the 1942 Beveridge Report, from which the current benefits system descends.[footnote 17] Indeed, contributory UB and SB funded by National Insurance are the origin of our current working age benefit system. Beveridge envisaged the design of these benefits should be based on six principles:

1. Flat rate of subsistence benefit: a set rate of benefit, irrespective of the amount of earnings which have been interrupted by unemployment, disability, or retirement.

2. Single flat rate of contribution: all, regardless of wealth or risk to employment, pay the contributions at the same rate for the same security.

3. Unification of administrative responsibility: social security offices set up in each locality to make administration simple, efficient, and economic.

4. Adequacy (of the benefit): benefit payments will provide the minimum income needed for subsistence in all normal cases.

5. Comprehensiveness: in respect of both those covered and their needs.

6. Classification: Insurance must consider the different ways of life of different sections of the community. The term classification refers to the adjustments made in insurance to the differing circumstances of those in different classes. Examples of classes are: employed earners, one beyond the age of earning, one below the age of earning or unpaid workers such as a person with caring responsibility.

This system of support would be triggered by a break in employment, and payment would be based directly on having made contributions previously, meaning there would be no extra burden on the taxpayer.

For those who did not qualify for either SB or UB due to a deficient National Insurance contribution record, National Assistance was introduced, replacing the existing poor laws. This provided assistance grants to those who could satisfy the local authority they were “without resource”. The legislation focussed in part on those with disabilities, formalising requirements of care expected from care homes and providing local authorities with the power to enact these[footnote 18].

Under the system introduced in 1948, the primary benefits were national insurance based, with means-tested National Assistance playing a subsidiary role, protecting those who had not made sufficient National Insurance contributions or whose needs exceeded its limits. This was a popular policy at the time[footnote 19].

The system put in place diverged from Beveridge’s original conception in many ways, and there has been further divergence from his blueprint over the subsequent 80 years. Several incremental factors have therefore led to the current position, whereby the contributory element of unemployment benefit makes up a small part of the current system:

- Rising costs from growth in private sector rents and increasing recognition of disability.

- Polarisation of the employment market, making some people more at risk than others[footnote 20].

- Changing social attitudes constraining political will.

- Rising numbers of single parents[footnote 21].

- The rise of dual working families – and in-work poverty – and the decline of the single breadwinner household.

- The move from full employment in the 1960s and 1970s to large-scale unemployment in the 1980s.

The current system is targeted and means-tested, rather than universal and contribution-based. The policy changes that have led to this position are too numerous to go into in detail here. However, it is worth emphasising that this is not the result of a wholesale overhaul of the benefits system by a single government. Rather the move away from Beveridge’s original insurance principles commenced as soon as his ideas began to be operationalised, with a move to means-testing accelerating from the 1980s through to the 2010s. As stated in our recent joint report with the Institute for Government, a key driver of reforms has been attempts to restrain the overall working-age benefits bill, which has risen as a share of national income over successive decades since at least the late 1970s as the costs of living for lower-income households (due to many of the reasons set out in the bullets above) have risen.

Unemployment Benefit

The idea that individuals would make provision beyond that offered by UB was built into Beveridge’s original concept but, from the start, payments were set below subsistence level somewhat undermining this objective. Further erosion of the insurance principle occurred as the flat rate of contribution was lifted, meaning higher earners paid more without being entitled to larger payments were they to lose their jobs (unlike the policies developed in many other Western European and Scandinavian countries where often out-of-work payments are, for a period, higher for those who had made larger contributions).

Simultaneously, the contributory principle was eroded with the introduction of means-testing under National Assistance, reducing the return from having paid into the system. National Assistance, was originally intended to be substantially less attractive than UB[footnote 22]. However, Supplementary Benefit, which superseded National Assistance, was uprated more regularly than contributory benefits. This meant not only that the value of means-tested benefits held up better over time, but at times those in receipt of contributory benefits also qualified for a top-up from the equivalent means-tested support, diminishing the distinction between these types of support[footnote 23]. As successive governments expanded or restricted the benefit system, one constant was a relatively greater role for means-testing and a relatively diminished one for the contribution element.

The shrinking importance of a distinct contributory unemployment benefit culminated with the introduction of JSA in 1996, which combined means-tested Income Support and contributory UB. This was in part driven by a commitment to reduce complexity within the benefits system, but it also shows that policy makers accepted that the overlap between these two forms of support was a permanent structural feature of social security.

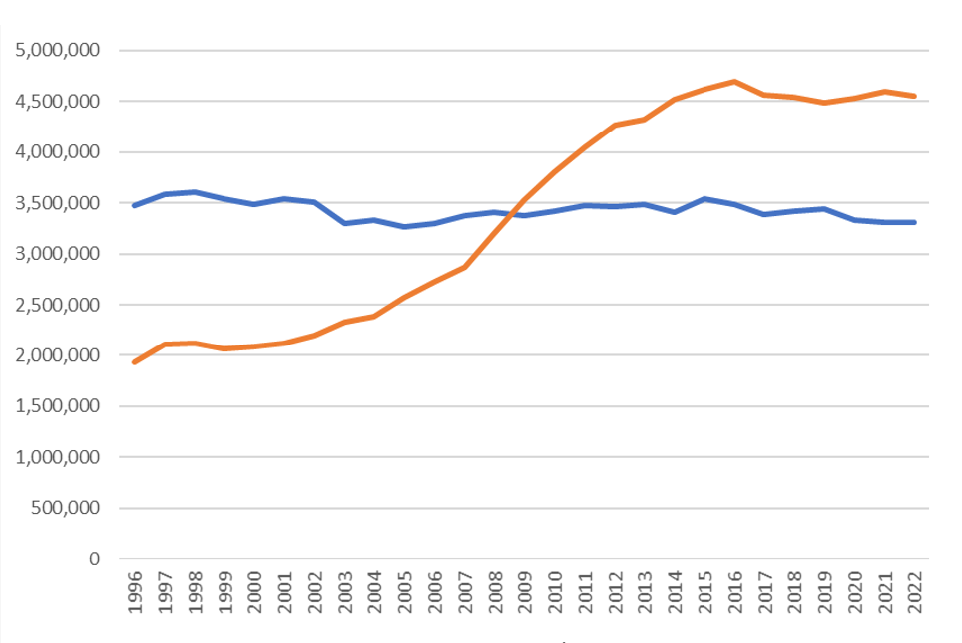

The introduction of a means-tested housing element became necessary, as the original contributory UB intentionally discounted housing cost[footnote 24]. Beveridge referred to this as “the problem of rent”, preferring a system that maintained a flat rate of contribution and payment to one that varied by region depending on cost of rent[footnote 25]. In the decades following his report, housing has become more expensive. This was partly driven by growth in the private rented sector (where rents are typically higher) relative to the social rented sector (when rents are often lower), and the widening differences in rents and house prices across the UK. Figure 3 shows that whereas the number of homes rented socially has been roughly flat over the last 25 years the number of homes privately rented has more than doubled. As a result, while as recently as 1999 there were 70% more homes rented socially than privately just 15 years later there were 30% more home rented privately than socially. Government changes to housing policy meant that the cost of housing has also risen in the social rented sector. Housing associations began taking on private loans to facilitate greater building capacity, with the extra cost passed onto renters resulting in an increasing Housing Benefit bill.

Figure 3. Changes in housing tenure type over time

Volume of rented houserholds by sector

Source: Households by housing tenure and combined economic activity status of household members: Table D - Office for National Statistics - ons.gov.uk

Consider this in the context of a labour market that has been polarising dramatically since the start of the 1980s. High earners contribute the most to this system, receive a lower level of income replacement and face a lower risk from immediate loss of earnings. This is in contrast to lower earners for whom low paying work is coupled with a social security system which is highly targeted at the poorest and provides relatively little financial support for those who sit outside the targeting criteria (compared internationally against other OECD countries).

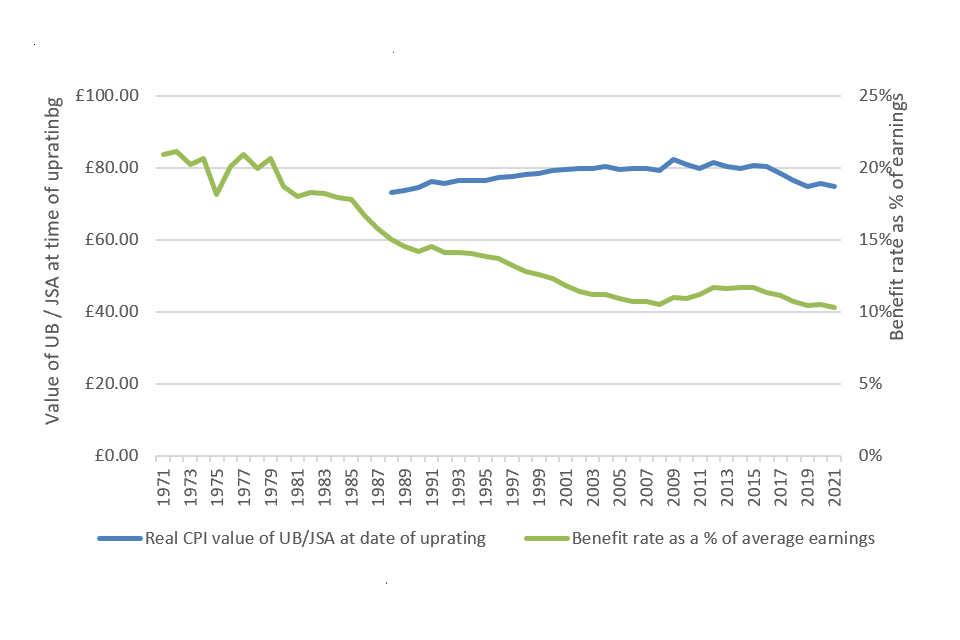

Over time, as shown in Figure 4, we can see that JSA has become less generous as a proportion of earnings and over the second half of the 2010s failed to keep up with growth in prices (as measured by the Consumer Price Index).

Figure 4. Rate of JSA over time

Source: Abstract of DWP benefit rate statistics 2021 - www.gov.uk

Disability and Sickness Benefit

Sickness Benefit (SB) follows a similar trajectory to UB, with greater targeting followed by an expansion of the means-tested offer starting in the 1960s. SB was introduced in 1948, representing the first earnings-replacement out-of-work disability benefit. In line with UB, SB was a contributions-based rate benefit thereby providing relatively greater insurance (in terms of income replacement) for low earners. Unlike UB, which was (initially) limited to 12 months, SB was not time-limited and therefore did not distinguish between those who were short-term sick and those with a long-term illness. As with UB, this had a weakened association with the contributory principle than that exemplified in Bismarckian models[footnote 26].

Disability benefits began to diverge from the contributory principle significantly in the 1970s. This was driven by a recognition that the existing disability benefit regime did not meet the needs of many who relied on it. Invalidity Benefit (IVB) replaced SB for those who remained off work for longer than six months. This was a contributory benefit and was more generous than SB. It was originally set at the same rate as UB, but by the end of the 1970s payments were 20% higher.

1983 saw the introduction of Statutory Sick Pay (SSP), which introduced a legal requirement that employers administer the first eight weeks of sick pay (rather than the Government). This was financed by a reduction in employer National Insurance contributions for the period for which SSP was paid to an employee. Crucially this removed one of the primary interactions between working people and the social security system, as rather than receiving a return on their contributions when sick, people were paid by their employers. The period was extended to 28 weeks in 1986. While there were some changes in 1991 and 1994 the scheme has been left largely untouched since then and is in need of a comprehensive review, not least given its perceived failings during the pandemic.

The reforms of the 1970s and 1980s increased the complexity of the disability benefits system whilst widening the parameters of those eligible for support. This, and the changing labour market through the 1980s, resulted in the number of people relying on disability benefits increasing by the 1990s[footnote 27]. The next iteration of disability benefit sought to address these challenges. In 1995, IVB and SB were replaced with Incapacity Benefit (IB). This saw further tightening of the eligibility criteria, with eligibility capped at state pension age and a tighter personal capability assessment. As with JSA, the contributory element was further eroded when a partial means-tested element was introduced, and the contributory requirement raised[footnote 28].

Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) was introduced in 2008. It replaced IB, as well as Severe Disablement Allowance and Income Support where these benefits were awarded on the grounds of incapacity. ESA is both a contributory and/or income-related allowance aimed to support those whose ability to work is affected by a disability or health condition. It introduced the Work Capability Assessment, an assessment process to determine whether claimants are entitled to ESA. Through this process, a claimant is categorised into one of three groups:

1) fit for work

2) the Work-Related Activity Group

3) the Support Group

Those deemed capable of work are not eligible for ESA. ESA claimants in the Work-Related Activity Group (WRAG) are found to have a limited capability for work but are capable of doing suitable work-related activity, meaning they are required to comply with conditionality. Those in the Support Group are those deemed to have both limited capability for work and limited capability for work-related activity.

Table 2. History of contributory out-of-work disability benefits

Duration of incapacity to work

| Year | 1-8 weeks | 9-28 weeks | 29-52 weeks | More than 1 year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1948-1971 | Sickness Benefit | Sickness Benefit | Sickness Benefit | Sickness Benefit |

| 1971-1982 | Sickness Benefit | Sickness Benefit | Invalidity Benefit (IVB) Invalidity Benefit (IVB) | |

| 1983-1985 | Statutory Sick Pay | Sickness Benefit | Invalidity Benefit (IVB) Invalidity Benefit (IVB) | |

| 1986-1995 | Statutory Sick Pay/Sickness Benefit | Statutory Sick Pay/Sickness Benefit | Invalidity Benefit (IVB) Invalidity Benefit (IVB) | |

| 1995-2008 | Statutory Sick Pay/Incapacity Benefit short term lower rate Statutory Sick Pay/Incapacity Benefit short term lower rate | Incapacity Benefit short-term higher rate | Incapacity Benefit long-term rate | |

| 2008-2013 | Statutory Sick Pay/Employment and Support Allowance | Statutory Sick Pay/Employment and Support Allowance | Employment and Support Allowance Support Group / WRAGa | Employment and Support Allowance Support Group / income-based Employment and Support Allowance Support Group / WRAG |

| 2013-2013 | Statutory Sick Pay / New Style Employment and Support Allowance / Legacy Employment and Support Allowance | Statutory Sick Pay / New Style Employment and Support Allowance / Legacy Employment and Support Allowance | Legacy Employment Support Allowance Support Group / WRAG / New Style Employment and Support Allowance support group / WRAG | Legacy Employment and Support Allowance support group and WRAG / New Style Employment and Support Allowance support group |

| 2021- | Statutory Sick Pay / New Style Employment and Support Allowance | New Style Employment and Support Allowance support group and WRAG | New Style Employment and Support Allowance support group |

a WRAG refers to work-related activity group, this group is expected to complete some work-related tasks such as attending some courses and meetings with work coaches.

Universal Credit as the single means-tested benefit

In 2010, the coalition government announced the most radical reform to the working age benefits system since Beveridge: the introduction of Universal Credit. This subsumed six means-tested working age benefits into one and therefore formed the core of our current working age social security system.

Though arguments for a Universal Credit style of benefit stretch back long before the coalition government of 2010, the Centre for Social Justice’s 2009 report Dynamic Benefits is considered to be the genesis of the system we have today[footnote 29]. In short, the report posits that (among many other things) the benefits system had become too complex and convoluted as successive governments had incrementally amended legislation to try and deliver the policy objectives of the day. This has led to the original insurance principles on which the system was ultimately founded, uneasily stitched to now much larger targeted and means-tested elements. This is clearly visible in legacy JSA and ESA but also through spending on Housing Benefit and in-work tax credits, that were by now much bigger programmes (in terms of expenditure and number of claimants) than the contributory out of work benefits.

Dynamic Benefits argued that in the interest of a simplified and rationalised benefit system, the distinction between contributory and means-tested benefits should be removed[footnote 30]. The new benefits system would therefore be entirely targeted, either through means-testing or another form of eligibility tests (e.g., capability for work assessment). Crucially, an individual would not have their access to support based on their contribution record and employment status alone.

The DWP’s White Paper – and the reforms that were subsequently implemented – instead maintained a contributory element within the working age social security system. The two contributory working age benefits were essentially left to the operate alongside Universal Credit. This was in sharp contrast to the concept of Universal Credit originally put forward in Dynamic Benefits. That vision of a purely means-tested working age social security system did not come to pass.

Chapter 3: The purpose and principles of contributory benefits

This chapter will address three aspects of the contributory system:

- the policy intent for the new style contributory benefits, why they were retained and the current role they play;

- the policy discourse on the contributory principle; and

- public attitudes to benefits and reciprocity.

The original policy intent of New Style contributory benefits

DWP’s 2010 White Paper Universal Credit: welfare that works provides an explanation of the need to continue to have contributory benefits at the point that Universal Credit would be introduced[footnote 31]:

Governments have wrestled with what to do with the contributory principle for working-age benefits ever since the Beveridge system was introduced. Piecemeal reforms have followed, such as the abolition of earnings-related supplements in the 1980s, restricting the period of entitlement to unemployment benefits in the 1990s and means testing Incapacity Benefit from 2001 in respect of income from occupational pensions. These proposals are consistent with that direction of travel and recognise the fact that we need to allocate limited resources where they will have the best effect.

Under the new system, contributory benefits would retain an insurance element, but in most circumstances would only be paid for a fixed period, only to facilitate a transition back to work.

Contributory Jobseeker’s Allowance will continue in its current form but with the same earnings rules (such as disregards and tapered withdrawal) as Universal Credit, as well as sharing the payment mechanisms and modernised administrative systems. This will ensure a seamless service for people who are entitled to both contributory Jobseeker’s Allowance and Universal Credit.

Contributory Employment and Support Allowance will also continue, with administration and earnings rules aligned with Universal Credit. However, for those in the assessment phase and those assessed as being in the Work-Related Activity Group their contributory Employment and Support Allowance will now be time-limited to a maximum of one year. After this time, qualifying recipients may be able to receive Universal Credit instead. We also intend to simplify the support for people aged under 25 who have been unable to pay the normal amount of National Insurance contributions as a result of their disability or health condition.

It acknowledges that the element of contributions to the benefits system have been decreasing over time and that this would not be reversed – these changes are “consistent with that direction of travel”. Despite that, explicit reference is made to the desire to maintain the principle of insurance as put forward in the original Beveridge reports. The White Paper also suggests that maintaining a contributory element allows for mechanisms such as rights towards state pensions to continue to accrue. The explanation of why either of these objectives could not be achieved within the Universal Credit framework is opaque. One explanation may have been that it was simpler to have a single benefit guided by a single principle of entitlement, i.e., by separating benefits that are means-tested from those that are insurance based. An alternative potential explanation could be concerns around the cost of benefit export to claimants who since moving out of paid work had moved to other European Union countries.

We wrote to the Department asking for the policy intent behind New Style ESA and New Style JSA. In its response the Department set out the direction of travel since the introduction of JSA in 1994 and ESA in 2008[footnote 32]. A particular feature that the Department highlighted is that, as New Style JSA claimants’ awards are unaffected by capital or the income of their partner, they are able to access employment support from Jobcentres. Following the completion of the nationwide roll-out of Universal Credit, and the experiences of the pandemic, it is a good time for the Government to formulate and set out a long-run strategy for the role that it wants these working age out-of-work contributory benefits to play.

Contemporary views on the role of the contributory principle

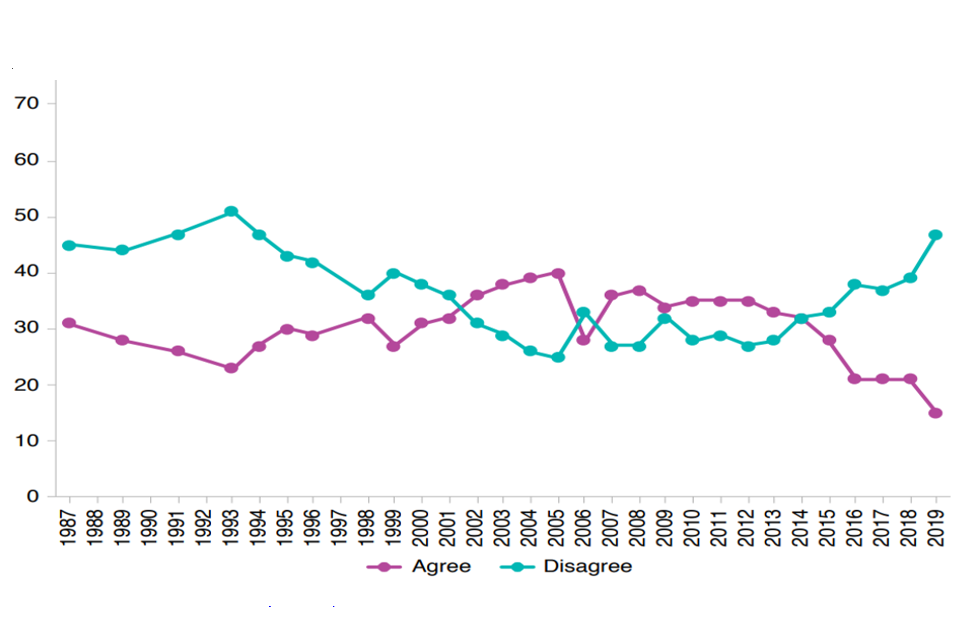

Attitudes towards the social security system have fluctuated in the past three decades. The late 1980s through to the early 2010s saw a long-standing decline in support for the social security system in the UK. This is exemplified in findings from the British Social Attitudes survey, which shows that the level of agreement with spending more on welfare benefits for the poor fell from 61% in 1989 to 27% in 2009[footnote 33]. However, this trend started to reverse from the mid 2010s, and in recent years support for welfare spending has increased markedly.

Around the time that the Universal Credit White Paper was published, a renewed appreciation for the notion of contribution emerged. This saw a revival of the principle of contribution as an antidote to the public loss of confidence in the working age social security system. Bell and Gaffney, in their 2012 report Making a Contribution, argue this is achieved by replenishing the equitable nature of the working age support[footnote 34]. Simply, those who have contributed more, receive more when having to rely on the benefits system. They argue that negative public attitudes towards working age social security and those who use it were in part driven by the perception of a “something for nothing” system, where those who had contributed over many years received very little when the need arose[footnote 35].

Hughes and Miscampbell take a similar stance in their paper Welfare Manifesto, published by Policy Exchange[footnote 36]. To address the “something for nothing” concern they propose a system that re-centres the insurance principle, as opposed to the ‘pay as you go’ tax on earnings that National Insurance contributions have become. They proposed that this should be administered privately and underwritten by government, with every worker in the UK contributing a small proportion of their weekly earnings into both a nationwide unemployment insurance scheme and a nationwide pot, the cost of which would be offset by a reduction in National Insurance contributions. The individual would then be entitled to three months of unemployment benefit from the insurance scheme. After three months they would move onto the nationwide pot, or Universal Credit.

Another proponent of a private scheme is the Centre for Social Justice. In Reforming Contributory Benefits (2016), the authors argue that the contributory principle is becoming redundant. They assert that this is occurring as a result of:

- the decreasing value of contributory benefits;

- the tenuous relationship to amount contributed to and that received from the benefit.

They also highlight the additional complication New Style benefits present to Universal Credit, which was designed to be simple. Therefore instead, the Centre for Social Justice advocates for a low premium insurance scheme for employees with auto enrolment by their employers. So, unlike the Hughes and Miscampbell proposal, it would not be compulsory; rather it would be strongly encouraged by the State. Aimed at those with over £16,000 in savings (precluding them from receiving Universal Credit) and administered by private sector, this would pay out at £900 per month (at 2016 rates). This would be in payment for one year before moving onto state benefits (if eligible).

The Resolution Foundation, writing in the post pandemic landscape, propose a publicly administered and publicly funded system with much greater earnings replacement, moving away from the flat rate system[footnote 37]. In contrast to the Centre for Social Justice and Policy Exchange papers, they suggest achieving this greater earnings replacement by significantly increasing the benefit amount available through contributory JSA and ESA. They argue that in the past too much emphasis has been placed on work incentives, ignoring wider economic and social benefits of greater earnings replacement.

Public perception

In practice, contribution-based benefits under the guise of New Style benefits have, if anything, become less visible under Universal Credit, which has dominated much of the discussion around working age social security in the UK. This is demonstrated in Figure 5, which shows Google searches for Universal Credit, New Style JSA and New Style ESA over the past five years (with searchers for Universal Credit clearly spiking with the onset of the first lockdown in March 2020).

Figure 5. Google searches for “Universal Credit” “JSA” and “ESA”

Source: Google trends

Public attitudes towards the benefits system saw a marked change from the late 1980s to the early 2010s, moving from largely positive to broadly negative (see figure 6). As discussed in Chapter two, this is in a context of an erosion of the contributory element of the out of work contributory benefits, polarising labour markets and an expanding private rental sector. At the point at which Universal Credit and New Style benefits were being developed, attitudes to those claiming social security were at historic lows. Having been less prevalent as part of public discourse during the period of the Labour government, unemployment benefits were making headlines during the coalition government, predominantly as part of its programme of reducing public spending.

Figure 6. Responses to the question “Many people who receive social security don’t really deserve it”

Source: British Social Attitude Survey

Following Bell and Gaffney’s line of reasoning, and given the current primacy of Universal Credit, public perception of welfare might have been expected to have slipped further. Yet in the latter half of the 2010s, as shown in Figure 6, public attitudes towards working age working age social security have begun to become more favourable. Around half of people in the UK disagree with the statement “Many people who receive social security don’t really deserve it”, the highest rate since the early 1990s. We also see the lowest rate of people agreeing with this statement since 1987. The British Social Attitudes Survey also reveals that 60% of people in England agree the Government should provide a decent standard of living for the unemployed, with this figure rising to 65% in Scotland[footnote 38]. In Northern Ireland, according to data from NI Life and Times survey (May 2022) more than 80% of those surveyed believe that social security should enable the recipient(s) to live with dignity[footnote 39]. Moreover with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 and the subsequent lockdowns resulting in large contractions within the employment market, it seems likely that attitudes towards unemployment benefit will continue to soften.

Chapter 4: How New Style benefits work

New Style benefits are intended to ensure at least a subsistence level of earnings protection for workers, predominantly employees, who find themselves temporarily unemployed. At its core, New Style benefits are an insurance-based system, therefore an individual must have paid-in, in order to get out. In spirit, its purpose is to provide a stop-gap to allow the worker to either recover from illness or find new employment – although where the worker is deemed to have limited capability for work or work-related activity due to illness or disability, support can be extended indefinitely.

Eligibility

New Style benefits are out-of-work benefits for working age people who have a (relatively) recent work history, and require that sufficient Class1/Class 2 National Insurance contributions have been paid or credited in the two financial years preceding the claim[footnote 40]. New Style benefits are payable only to claimants who are unemployed, or working fewer than 16 hours a week and earning less than £152 a week; who have not made a previous successful claim in the preceding six months. For New Style JSA claimants who are working, awards are reduced pound for pound against earnings in excess of £5 per week. There is provision that allows New Style ESA claimant to take a break from ESA to try paid work, then return to the benefit, providing the break is no more than 12 weeks and the claim was not closed because the claimant was found fit to work. In this instance the claimant does not need to be re-assessed to receive ESA when returning to the benefit.

New Style ESA and JSA cannot be claimed at the same time, as they are intended to fulfil the same policy function for different groups, thus – sensibly – qualifying for New Style ESA disqualifies an individual from claiming New Style JSA and vice versa.

New Style JSA and ESA can be claimed alongside Universal Credit, as the qualifying criteria differ. However, if claiming New Style alongside Universal Credit as a dual claim, the net value of the Universal Credit award is offset pound for pound. For example, if an unemployed renter receives Universal Credit and New Style JSA, the effect is as if the personal element of Universal Credit is set to zero, but the housing element of Universal Credit is unaffected.

The eligibility criteria for New Style benefits and Universal Credit are summarised below.

Table 3. Eligibility criteria for New Style JSA, ESA and Universal Credit

| Benefit Type | New Style JSA | New Style ESA | Universal Credit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employment status | Must be unemployed or working less than 16 hours per week | Must be unemployed or: * working less than 16 hours per week * earning less than £143 per week in supported permitted work * must not be entitled to SSP |

Can be in or out of work |

| National Insurance contributions | Must have sufficient Class 1 or special Class 2 contributions | Must have sufficient Class 1 or special Class 2 contributions | NA |

| Assessment period for National Insurance contributions | 2 to 3 tax years prior to year of claim | 2 to 3 tax years prior to year of claim | NA |

| Age | Must be between 16 and state pension age | Must be between 16 and state pension age | Must be between 18 and state pension age (some exceptions for those aged 16-17) |

| Savings | N/A | N/A | £16,000 or under |

| Household Earnings | N/A | N/A | HH earning up to £335 before taper rate of 55p in each £ |

| Availability to work | Must be available to work | Does not need to be available for work | Must be available to work unless: * Ill / Disabled * Main carer * In work earning over minimum wage / self employed |

| Illness or disability status | Must not have illness or disability that stops you from working | Must have disability or illness that stops you from working | Can receive extra benefit component if ill or disabled |

| Currently in full time education? | Must not be in full time education | Can be in full time education if: * Already in the support group * Have sufficient National Insurance contributions in preceding two years |

Can be in full time education in certain circumstances |

| Country of Residency | Must be resident in the UK | Must be resident in the UK | Must be resident in the UK |

| Required period between separate claims | 6 months | 6 months (unless trying work for up to 12 weeks before returning to benefit) | N/A |

| Time limiting | 6 months | 1 year (365 days) for those not in the support group | N/A |

Benefit rates

Benefit rates for New Style ESA and New Style JSA are for single individuals, and currently harmonised with the equivalent means-tested elements of Universal Credit, as shown in Table 4. This appears to be the level at which subsistence is set in the UK context, although when setting the rates of benefit there is no explicit reference to any measure of adequacy: for example, that provided by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation[footnote 41].

Table 4. Rates of New Style JSA, ESA and Universal Credit for a single individual

| Weekly £ April 2022 | New Style ESA: Assessment rate | New Style ESA: WRAG | New Style ESA: Support group | New Style JSA | UC equivalent JSA | UC equivalent Income-related ESA: Assessment rate | UC equivalent Income-related ESA: WRAG | UC equivalent Income-related ESA: Support group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 25 | 61.05 | 77.00 | 117.60 | 61.05 | 61.05 | 61.05 | 77.00 | 117.60 |

| Over 25 | 77.00 | 77.00 | 117.60 | 77.00 | 77.00 | 77.00 | 77.00 | 117.60[footnote 42] |

However, if we look at couple claims, we can see that JSA is more generous than Universal Credit, as shown in Table 5. This is because for a couple where both receive New Style JSA the amounts paid are twice that of a single individual receiving that benefit, whereas that is not the case in Universal Credit.

Table 5. Rates of New Style JSA and Universal Credit for a couple

| Benefit Type (weekly award £) | New Style JSA | Universal Credit |

|---|---|---|

| Both Under 25 | 122.10 | 96.21 |

| One under 25 one over 25 | 138.50 | 121.32 |

| Both Over 25 | 154.00 | 121.32 |

International Comparison

Comparing internationally, we see that for a period, the UK has a relatively low level of average income replacement, particularly for those with an uninterrupted contribution history. Table 6 shows benefit replacement rates in the UK against the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) average. A key difference here being that UK benefits, including New Style, pay out a flat rate of benefit regardless of previous earnings. If we look at the average replacement rate across the OECD other systems often – for a period – pay a level of benefit that varies positively with the claimant’s previous earnings and therefore provide greater insurance against job loss.

Table 6. Replacement rates for different family types for workers on average earnings, 2018

| Family type | UK | OECD Average without contributory benefits | OECD Average with contributory benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single, no children | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.55 |

| Single, 2 children | 0.35 | 0.40 | 0.66 |

| Couple, no children | 0.20 | 0.31 | 0.57 |

| Couple, 2 children | 0.41 | 0.47 | 0.66 |

Source: IFS Green Budget 2020 - Institute For Fiscal Studies - IFS

This table is based on a family with one worker paid average earnings. ‘UK’ refers to those in receipt of either New Style benefit or the unemployment element of UC (which are set at the same rate). ‘With contributory benefits’ shows replacement rates for a worker, aged 40 and having worked uninterrupted since age 19, receiving unemployment benefit. ‘Without contributory benefit’ refers to those who do not have access to contributory benefit. All figures relate to the second month of unemployment and ignore housing benefits. It assumes two children aged four and six years old. The average is measured across 36 OECD countries (Turkey is excluded due to a lack of data). Replacement rate measures out-of-work income as a share of in-work income.

Divergence between New Style and Universal Credit

There are two final points of note where New Style benefits and Universal Credit are not harmonised. First of these is regularity of payment. For New Style claimants, payment is made every two weeks, whereas payment for Universal Credit is, by default, once a month. The second is the type of National Insurance Credits afforded individuals in receipt of the benefit. New Style claimants receive Class 1 National Insurance Credits[footnote 43]. Those in receipt of Universal Credit receive Class 3 National insurance credits[footnote 44].

A further difference is that New Style benefit income is subject to income tax, whereas Universal Credit is not. This will matter for those individuals who are in receipt of New Style benefit income in part of the tax year and have a higher income, for example from earnings, at a different point in the year. For these individuals the receipt of New Style benefit income will affect their income tax position.

One final difference between the two New Style benefits and Universal Credit is the seven-day waiting period between becoming unemployed/having limited capability for work in New Style benefits, whereas a claim for Universal Credit can, since February 2018, be made immediately.

Means-testing

As stated earlier New Style benefits do not take into account the level of household savings, or the earnings of a partner. Yet New Style benefits are, in some cases, means-tested against an individual’s income. This applies in two cases:

1. A claimant’s earnings may impact the amount of New Style JSA the claimant receives. Beyond the earnings disregard (£5 p.w. per single, £10 p.w. for couple / joint award), New Style JSA is tapered pound for pound with personal earnings. If a New Style JSA claimant (even if working fewer than 16 hours per week) earns more than their award of New Style JSA plus the appropriate earnings disregard, they will not be paid any New Style JSA. For those on New Style ESA earnings of less than £140 per week are disregarded (but still have to be reported) and claimants are not allowed to earn more than this or work for 16 hours or more per week under the permitted work rules.

2. A further means-test also applies: an individual’s income from a private pension or an occupational pension can affect an award of New Style benefits (but not the private pension of a partner). For New Style ESA claimants their NS benefit is reduced by 50p for every £1 of income from a private or occupational pension in excess of £85 per week. So, for example, someone receiving an occupational pension of £100 per week would see their New Style ESA reduced by £7.50 a week (50% of £100 less £85). The threshold of £85 per week has not been uprated since it was introduced in 2001. For New Style JSA claimants their NS benefit is reduced by £1 for every £1 of income from a private or occupational pension in excess of £50 per week. The threshold of £50 per week has not been uprated since 1996.

Work search and sanctions

There are certain circumstances in which an individual can do limited work and claim New Style benefits. New Style JSA claimants can work up to 16 hours per week, but must devote most of their time to finding full time work. New Style ESA claimants can also do up to 16 hours per week of work, and can work more hours than this if the work is either voluntary, supervised by someone who organises work for disabled people or part of a treatment programme under supervision. New Style ESA claimants are not permitted to earn over £143 per week. This differs from Universal Credit claimants, who have no limit on the hours they can work but have their benefit reduced by 55p for every pound earned, referred to as the earnings taper. Some claimants, such as those with a disability or children, have a work allowance that protects earnings from the taper up to a set amount. This is £573 per month for those not in receipt of Housing Benefit and £344 per month for those in receipt of housing costs benefit[footnote 45].

Work search activities within New Style are harmonised with their Universal Credit equivalent. When claiming New Style benefits, the individual is generally expected to complete certain work-related activities. As with Universal Credit claimants, the exception to this are those found to have limited capability to work and work-related activity, under New Style this group is placed in the ESA Support Group. New Style ESA claimants and Universal Credit claimants placed in the Work-Related Activity Group (or UC equivalent) are required to complete an interview with a work coach to ascertain their past work history and steps that could help lead to future employment[footnote 46]. The claimant will then be expected to meet with the work coach on a regular basis to discuss their progress. Depending on the outcome of this interview, the New Style ESA claimant might be expected to take part in sessions to help with:

- basic maths

- confidence building

- CV writing

- managing a disability or condition[footnote 47]

Claimants of New Style JSA have a Claimant Commitment similar to that of people in receipt of Universal Credit. The Commitment is agreed between the work coach and the claimant in their first meeting. This determines the amount of work search activity required, which may vary depending on individual circumstance. It can also stipulate the type of work search activity required, for example uploading a CV to a particular site.

For both New Style ESA and New Style JSA, if work-related activities are not met the individual is liable to be sanctioned.

Until November 2021, New Style claimants were not sanctioned if they did not uphold their Claimant Commitments[footnote 48]. This was a divergence from the Universal Credit regime with which the requirements placed on New Style claimants are otherwise harmonised. As of November 2021, sanctions have been included for New Style claimants. Sanctions for New Style do not perfectly mirror those of Universal Credit, with the level of - and reasons for - sanctions differing slightly between New Style ESA, New Style JSA and Universal Credit[footnote 49].

Chapter 5: How does it work in practice?

Elements of the system that are working well

It is important to state that in researching this report, the Committee has found numerous instances of the New Style systems working well. We spoke to individuals for whom the process of moving through the claimant journey, for both New Style JSA and New Style ESA, was for the most part smooth and functional. This is to say, for the cases we reviewed, when the system performs well a good service is provided to the claimants relying on it.

Amongst some of the positive aspects of the process we heard about, a recurring theme was that there had been an improvement in the service offered compared to past interactions that claimants recalled having with the Department.

“I think the service is far better now, the Jobcentre staff were really respectful and professional compared to when I claimed decades ago. When claiming income support in the past, I was treated like a bit of dirt.”

Claimant of New Style ESA (England)

As illustrated above, this was often attributed to an improvement in the perceived interaction between claimants and the Department. Claimants generally reported that they were treated respectfully and compassionately by DWP staff, although this was not a uniform experience.

A respectful attitude towards claimants was also evidenced in the discussions with DWP operational staff. New Style JSA claimants tended to be viewed positively, as a “good group to work with” (DWP work coach from the South of England). New Style ESA claimants tended to be viewed with compassion, though we found evidence this was sometimes manifested in a willingness to forego the usual contact / work-related activity requirements of those in the WRAG. This is not necessarily unambiguously positive and, as we discuss later in the report, it may lead to individuals in receipt of New Style ESA missing out on desired support back into employment.

Anecdotally, DWP staff reported that the vast majority of those in receipt of New Style JSA to whom they spoke were well motivated to return to paid work and indeed left the benefit to go into paid work before reaching the six-month time limit. Equally, all the JSA claimants we spoke to came across as highly motivated to re-enter the labour market. One claimant reported having been made aware of the six-month limit at the start of their claim, stating:

”I am very much hoping to have another job by then”.

Claimant of New Style JSA (Wales)