Jobs and benefits: the COVID-19 challenge

Updated 18 March 2022

A joint report by the Institute for Government and Social Security Advisory Committee

Nicholas Timmins and Gemma Tetlow

Institute for Government

Carl Emmerson and Stephen Brien

Social Security Advisory Committee

About this report

This report looks at what can be learned from the experience of the coronavirus pandemic about the opportunities for reforms to government financial support for working age people and the key features of a social security system that has flexibility to respond rapidly to new labour market conditions. It was produced jointly by the Social Security Advisory Committee and the Institute for Government. It draws on discussions among former senior civil servants, academics and other experts at two roundtables, hosted by the Institute for Government, in autumn 2020.

Institute for Government

@instituteforgov

Social Security Advisory Committee

@The_SSAC

Foreword

The COVID-19 pandemic has posed challenges to government of a nature and scale that were impossible to imagine a year ago. As both the Institute for Government (IfG) and the Social Security Advisory Committee (SSAC) have highlighted in previous work, the Department for Work and Pensions responded impressively quickly in adjusting policy and delivering support to those who needed it.

But the pandemic has also thrown up deeper questions about the structure of financial support provided to working age people in the UK and COVID-19 is likely to have a lasting impact on the labour market. Both the IfG and SSAC have a strong interest in ensuring that government continues to respond well to these challenges. SSAC is an independent statutory body that provides impartial advice and assistance to the secretary of state for work and pensions. The IfG is the leading think tank working to make government more effective. It conducts rigorous research and analysis to explore the key challenges facing government and provides a space for discussion and fresh thinking to help senior politicians and civil servants think differently and bring about change.

To help examine the questions thrown up by the experience of COVID-19 and provide advice to the government on the areas most in need of attention over the coming months and years, IfG and SSAC organised two virtual roundtable meetings. These brought together a group of former senior civil servants, academics and other experts to discuss what should be learnt from the past year. This report is the result of those discussions. It would not have been possible without the contributions of those who attended the roundtables, but the conclusions and recommendations expressed are those of the SSAC and IfG, rather than those of the participants.

The report highlights that, while the current social security system has held up very well to the pandemic, there are ways in which it could be fine-tuned to make it more effective. There is also a strong case for the government to reassess what the benefit system is for and to change the language used to describe it – re-adopting the language of social security in place of the widespread use of ‘welfare’. The most important emerging challenge in 2021 is likely to be how to deliver a return to full employment in the UK. There is an important role for the government to play in this, and the approach for managing the return to employment and the sectoral shifts involved needs to be systemic.

Dr Stephen Brien

Chair, Social Security Advisory Committee

Bronwen Maddox

Director, Institute for Government

[Someone losing his job in] middle England will want to feel there is a high-quality health and education system on which his family can depend. He will want to know that there is a modernised, affordable, welfare system which will assist him to retrain and find new employment.

Kenneth Clarke, Conservative chancellor of the exchequer, 1994

Introduction

COVID-19 has posed and is posing what can fairly be described as unprecedented challenges to both social security systems and employment services around the world. The UK is no exception. The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) responded remarkably well to the immediate impact of the pandemic, redeploying its own and others’ staff for the better in a number of its processes. Through Universal Credit (UC), it coped with an entirely unprecedented surge in claims and it is now recruiting more job coaches to help people back into work while repurposing some of its estate. But the pandemic has also exposed weaknesses in the UK’s social security system.

To assess what lessons could be learnt and what issues should be addressed – with a focus less on the immediate response and more on the medium-term and beyond – the Social Security Advisory Committee (SSAC) and the Institute for Government (IfG) held 2 webinars in October 2020 under the Chatham House rule.* Those present are listed at the end of this report. It must, however, be stressed that this summary is what the IfG and SSAC drew from what was said at the meetings and none of the attendees, who held some divergent views, are responsible for what follows.

We start with 2 propositions reviewing the immediate and likely longer-term impact of the pandemic. We then provide a brief account of how the UK benefits system has come to be the way it is, before making recommendations for changes both to that system and on the measures needed to tackle the crucial task of getting people back into work. This set of recommendations has not been costed at this stage as a number serve to illustrate a direction of travel, rather than highly specific policy options.

*This reads: ‘When a meeting, or part thereof, is held under the Chatham House Rule, participants are free to use the information received, but neither the identity nor the affiliation of the speaker(s), nor that of any other participant, may be revealed.

Propositions

1. There is a need to reassess the concept of social security

Those on contributory working age benefits – Jobseeker’s Allowance (JSA) and the Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) – to which people are entitled if they have paid the requisite National Insurance contributions - found themselves left out of the increased generosity put into Universal Credit. Significant numbers of others found that they could not claim UC because their savings, while not enormous, were too large.

When people find themselves out of work, the UK’s income replacement rates are low by the standards of many other developed countries. And over the past couple of decades, the UK has lost the concept of ‘social security’ in its benefit system. In the early 2000s, tax credits – a mainly in-work benefit – were taken out of DWP and paid via Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC). This was done in an attempt to remove the perceived stigma of means-tested benefits. The result, however, is that the benefit system has increasingly come to be discussed largely in terms of ‘welfare’ – the means-tested bit – when the UK’s social security system has always been more than just a safety net for the least well off. It has not helped that the public debate around Universal Credit has been so focussed on the difficulties that the initial 5 week wait for the first payment has caused – with the arguments that it has led to a rise in the use of food banks, rent arrears and other forms of debt. In practice, precisely because it unifies the in-work tax credits with out of work benefits, it is not just a benefit for the least well-off, crucial though that role is. Universal Credit is also key in providing security to millions of those in paid work. When it is fully rolled out more than 7 million households will be in receipt of at least some support from it – roughly a third of the working age population. Over time – and these calculations preceded the pandemic – 40% of adults are likely to be.[footnote 1]

2. Training and employment services need to become stronger and more flexible

The pandemic has dramatically reinforced some trends already under way – for example the shift to on-line retail, working from home, and, perhaps, towards greener energy. This in turn creates new challenges. A significant number of those who become unemployed may need to change the sector in which they work, or the location of their work, and possibly both. Support for people to cope with that needs to be strengthened, and in ways that make it more adaptable for future challenges.

Previous labour market shocks

The impact of the coronavirus pandemic on unemployment, and on the likely pattern of services needed to help people get back into work, differ from any of the shocks to the UK labour market in recent decades. But the nature of those, and what might be learnt from them, are worth very briefly rehearsing, by way of introduction.

The huge rise in unemployment in the early 1980s was the product of a generalised recession. But the most permanent scars from this period were left in cities, towns and villages that were hit by the closure over the decade of coal mines, steel work, ship building and other manufacturing sectors – with their knock-on effects to other supply industries and the local economy. The worst effects – which can still be seen more than 3 decades on – were localised, even if localised on a large scale.

Central and local government and employers struggled to find replacement economic activity in the areas hardest hit. Those who suffered most included young people who faced prolonged periods of unemployment, and older workers – in particular older male workers – who had very limited prospects of another job locally. Although this was the better part of 40 years ago, both people from those areas and policy makers remember such times. Indeed, many of these areas are the focus of the prime minister’s ‘levelling up’ agenda.

The recession of the early 1990s was less localised. Youth unemployment rose sharply. But – and these are broad generalisations – employers tended also to shed jobs rapidly, in particular stripping out middle management in the face of technological change. As the economy improved, a significant number of employers found they had lost key skills that were difficult and expensive to re-recruit.

That experience appeared to produce a reaction following the financial crisis of 2008. Employers hoarded labour more than in past recessions, and a significant number of private sector employees accepted pay or hours reductions – perhaps themselves remembering the impact of the 1990s recession. The government rapidly expanded the numbers working in Jobcentres – not just to handle benefit claims, but to help people back into paid work. It also introduced a number of innovative employment measures – including the Future Jobs Fund,[footnote 2] which provided heavily subsidised employment for those unemployed aged under 25. The net result was that while unemployment rose sharply, it peaked well below the level that many had feared.

Each of these recessions produced short-term unemployment. But all of them, though to differing degrees, also led to longer-term unemployment, to more people becoming economically inactive (not having a job or no longer actively seeking work, but not being required to because they were not themselves claiming unemployment benefits), and to other issues that often accompany job loss (debt, family breakdown, health problems and, in the case of one of these recessions at least, a sharp rise in the numbers receiving disability benefits).

Much of the same is likely to happen this time round, especially as the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS, or ‘furlough’) programme is unwound. Measures that successfully reduce these longer-term impacts would benefit both the individuals affected and, most likely, the wider economy.

Possible labour market impacts from COVID-19

The impact of the pandemic has yet to play out in full. Unlike the 3 recessions detailed above, this one is not the product of imbalances in the economy. Initially the hope was that the economy could largely be held in stasis until the pandemic had passed, and then it could be switched back on rapidly and fully. At this stage much remains uncertain, even though the likely successful arrival of rapid testing and vaccines improves the outlook. It is unclear whether, at the end of the day, there will be different impacts in different parts of the country. There has been a huge increase in working from home – a trend already underway, although on a much smaller scale. Unless that trend is reversed entirely, it does look likely that there will be a lasting reduction in the numbers working in city centres, and thus on the hospitality and retail sector jobs that those locations have supported.

What is clear, however, is that particular sectors of the economy have been hit particularly hard – airlines, airline suppliers, oil, hospitality, shops, the performing arts and some other creative industries, for example. In these both people with fewer skills and some who are highly skilled are losing their jobs when they had no reasonable prior expectation that was likely to be the case. While some of these sectors will recover in time, not all are likely to do so quickly.

In others, the impact of the virus looks to have accelerated trends that were already underway – the shift to online shopping for example, which implies more warehouse and delivery jobs (though warehousing is undergoing its own automation) but many fewer ‘bricks and mortar’ retail jobs. Equally, engineering jobs were already moving away from fossil fuels and into greener forms of energy – indeed, for the UK to achieve its net zero target by 2050 they will need to. These are sectors where the skills, though not necessarily the location of the jobs, may well be transferrable. The same could apply, for example, to engineering jobs in airlines and engine making, while the shift towards a greener economy will more generally provide new job opportunities.

But it is much less clear, for example, how the skills of an airline pilot might be redeployed, and while people will, of course, continue to fly, it is entirely possible that for a long time at least, airlines will have a smaller footprint. Many customer-facing roles in city centres may never return, even if, as again seems likely, they re-appear in suburbs and commuter towns in a less concentrated form. It seems likely that, among private sector employees, women will be affected at least as badly as men because more women than men work in the hardest hit sectors like hospitality and retail. For example, over the period from July 1 2020 to October 31 2020 between 4% and 11% more women were furloughed than men.[footnote 3] This is another difference from the previous recessions, where it was men rather than women who were much more likely to lose paid work.

There are vacancies and indeed new jobs in areas of growth – tech, green energy and social care, although the latter, especially, will not be for everyone. In some sectors where skills seem eminently transferrable – cabin crew for example may well have at least some of the skills needed for social care – their earnings, if they take such jobs, are likely to be smaller.

The, at least temporary, conclusion is that large numbers of people will end up needing to shift sectors. They may well need to retrain. They may well have to move geographically. The new realities of life outside the European Union – with the Brexit transition period having ended on 31 December 2020 – will also produce differential impacts on different parts of the economy and different parts of the country, and those impacts will themselves differ to those of COVID: affecting the tradeable sector rather than consumer-facing industries.[footnote 4]

All of this presents new demands on the social security system and on the employment services needed to help people into paid work.

Immediate response to the pandemic

The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) performed extremely well in its immediate response to the March lockdown.[footnote 5] Universal Credit handled an unprecedented surge of claims – almost a million in the fortnight after the first lockdown was announced, and more than 100,000 on one day alone, 10 times the normal rate. Given the scale of the challenge, there were inevitably some teething troubles. But the automated nature of much of UC, the rapid re-deployment of staff within DWP and across government, and the speedy development of home working saw 93% of claims paid on time and, crucially, at no point did the system fall over. Had it done so a very large number of families would undoubtedly have experienced much more substantial hardship.

The legacy means-tested unemployment benefits that Universal Credit replaced were never tested on anything like this scale, and it is far from clear that their less automated processes would have been able to cope. And, despite the 5-week wait for the first payment (softened to some extent by advances being available) it got money to recipients much faster than the CJRS got money to employers, or the Self Employed Income Support Scheme got money to the self-employed, impressive though both those exercises were in their execution.[footnote 6]

The government added a ‘temporary’ £20 a week, or £1,040 a year, to the standard personal allowance in Universal Credit for 2020 to 2021. It also added a ‘temporary’ uplift to the housing element, in recognition of the fact that rents being paid for private rented accommodation had become increasingly detached from the rents benefit recipients in practice pay. That increase has been made permanent, as confirmed by the work and pensions secretary in September. However, according to the November spending review, it will not be indexed. It will remain the same in cash terms, unless a later decision is taken to increase it.[footnote 7]

DWP took some crucial further decisions. The ‘claimant commitment’ requirements to be available for paid work, look for it and take it up were suspended – and as a result sanctions for failing to comply fell dramatically. The department also solved the huge load on its call lines by adopting a process where its operational staff called claimants, rather than claimants queuing on the phone. The roundtable heard that claimants much appreciated this more personal approach.[footnote 8] On social media, while there are inevitable criticisms, there has also been appreciable praise for DWP from the many who have had to deal with the means-tested benefit system for the first time.

Against that, as was said at the webinars, some who had previously not had to rely on benefits were stunned to discover just how low benefit rates for the unemployed are, and that savings of £16,000 debar a claim for Universal Credit.[footnote 9]

A little more history and background

It was noted at the roundtables that, outside academic circles, there has not for a long time been much public debate about the purpose of the benefits system. For example, how far is the goal to return people to paid work as fast as possible? To what extent does it seek to return people to jobs of a similar pay and security to the one they have left as opposed to any job? How far is it there to prevent poverty, both for those in paid work and out of it? How should benefit levels be set – in relation to earnings or some objective definition of a poverty line? At present, the amounts are largely a reflection of historic levels.

What is clear however, as the webinars noted, is the direction of travel since at least the mid-1990s, under governments of all colours – Conservative, Labour, the coalition and now Conservative again.

The UK system has become more means-tested, and more conditional

Throughout that period the working-age system has become increasingly means- tested. It has also become increasingly conditional: the requirements have risen for those receiving out-of-work benefits to prepare for, look for and take work, including for some with health and disability issues. In addition, as was pointed out at the webinars, DWP’s labour market approach has essentially been one of ‘work first’, it being judged important to get people to any type of paid work as a first step, rather than necessarily waiting for a job that might better match their skills.[footnote 10]

The point was also made that other changes have been introduced on the argument that people face choices that they need to make.[footnote 11] For example the relatively low percentile of local housing costs that Housing Benefit and the equivalent part of Universal Credit covered (from the 50th percentile in 2012 to at most the 30th percentile now), and the 2-child limit in means-tested payments. The roundtable also heard arguments that, outside of recessions, many politicians have for some time now regarded most unemployment as essentially voluntary.

The role of contributory benefits has shrunk

As part of this shift, the already limited role of contributory benefits (those that individuals are entitled to through having paid sufficient NICs) has shrunk.[footnote 12] There is no room here for a full history. The drivers, however, have included attempts to restrain the overall working-age benefits bill, which has risen as a share of national income over successive decades since at least the late 1970s.[footnote 13] The drivers of this include many reasons well outside the control of DWP and its predecessors, including how the cost of living has grown for those on lower incomes.

For example, seeking to limit the housing benefit bill has largely been a case of trying to run up a down escalator due to housing policies over many decades that have seen strong growth in private sector rents alongside increasing numbers of renters in typically more expensive private sector (as opposed to social sector) properties. Changing family structures – in particular growth in the number of single parents in the 1980s and 1990s – added to the benefits bill. There has also been an increase over the years in disability benefits paid for reasons of mental as well as physical health. And much more is now spent on in-work support (via tax credits and Universal Credit and in meeting child care costs) to counter the effects of low earnings.

The department is in many cases being asked to pick up the consequences of wider issues and problems in society – as highlighted in an earlier joint IfG/SSAC paper.[footnote 14] To criticise it for at times struggling to do that is less than fair. One effect of such trends, however, has been to increase pressure to restrain growth in the overall working-age benefit bill, which in turn has meant that over the years it is not just that more conditionality has been attached to the remaining contributory benefits, but their value has also been reduced (for example through harsher time limiting).

So, for example, Unemployment Benefit (UB), the predecessor of JSA, was often paid at a slightly higher rate than the means-tested Income Support – the benefit for those who had not paid sufficient NICs or whose time on UB had expired. UB was paid for 12 months, with relatively little in the way of work-search conditions attached. In 1996, Unemployment Benefit and Income Support for the unemployed were combined into JSA, which had both the contributory elements (the old Unemployment Benefit) and means-tested elements (Income Support) in it. Contribution-based JSA became payable for 6 months only, rather than a year, and more demanding conditions to ‘actively seek work’ were attached to it.

More recently, recipients of contributory JSA have had to accept the claimant commitment which, as standard, has yet stronger work search requirements, including one to look for work for up to 35 hours a week.[footnote 15] Prior to the COVID-related changes, JSA was paid at the same rate as the standard personal allowance in Universal Credit. Equally, Incapacity Benefit, the National Insurance-based benefit for those unable to work due to health conditions became more means-tested, even ahead of its replacement by the ESA.

In other words, for those of working-age, the reward for paying what used to be known as ‘the stamp’ – i.e. NICs – has shrunk over the years as the social security system has become more means-tested and more conditional. Indeed, one contributor at the webinar suggested that there is a view in DWP, particularly since the arrival of Universal Credit, that the contributory benefits are an irritating anachronism that should be dispensed with. Given their small size, there is a case for that. But there is also a case the other way.

There remain some advantages for claimants of contribution-based JSA. Unlike Universal Credit, it is an individual benefit, not a household one, so a partner’s income does not affect entitlement – and there are no savings rules. That means it can help significantly reduce the fall in household income where a partner is still in paid work. However, unlike means-tested JSA or Universal Credit, it does not come with any entitlement to additional assistance, such as free prescriptions or free school meals, and more conditions are attached to it than in the past.

And public attitudes to social security benefits change

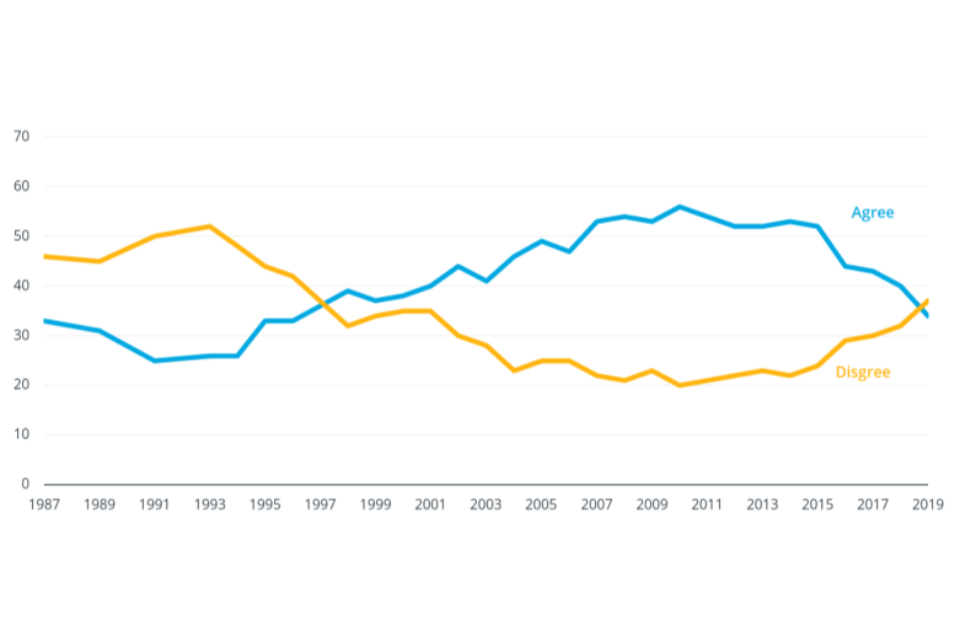

How far it is politicians who have driven the view that the working-age benefit system should be more means-tested, more conditional and less generous, and how far they have been reflecting changes in public attitudes, is a matter of debate.[footnote 16] What is clear, from the British Social Attitudes Survey – the long-running annual snapshot of what Britons think – is that attitudes to the unemployed hardened from the late 1990s on, as Figure 1 shows.

An increasing proportion of people agreed rather than disagreed with the statement that ‘if welfare benefits weren’t so generous, people would learn to stand on their own two feet.’ That reached a peak in 2010 when 54% agreed and only 21% disagreed. Since 2015, however, the picture has gradually changed, to the point where in 2019 – ahead of the pandemic – only 34% agreed, while 37% disagreed with the notion that welfare benefits are too generous. The scale of change is significant and means that there is now an evenly-divided debate among the public about the generosity of benefits. These levels have not been seen since the mid-to-late 1990s.

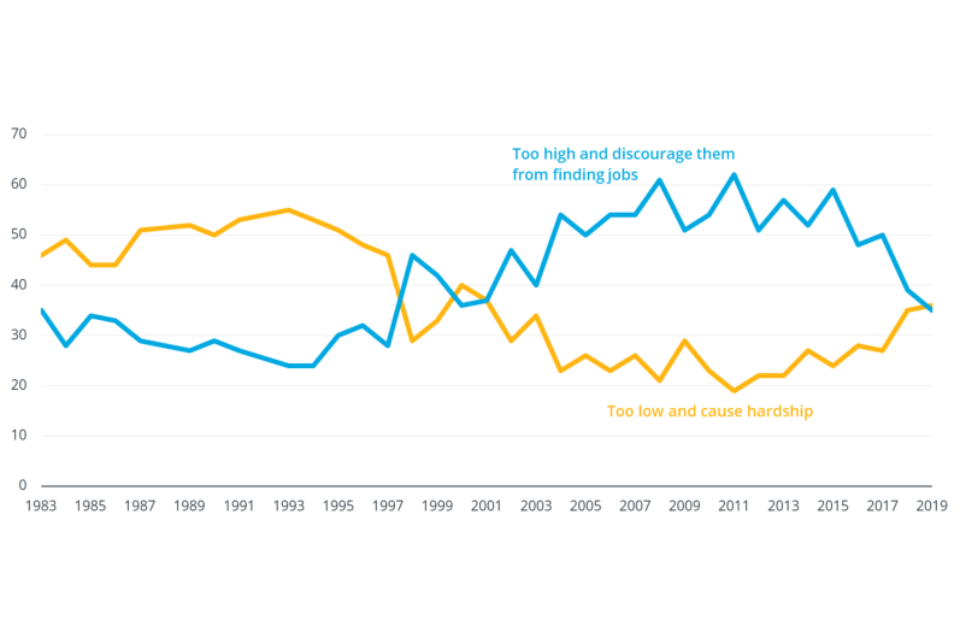

It would be surprising if the recent trend did not continue – if not accelerate – through the pandemic, in the same way that attitudes changed following the rise in unemployment in the early 1990s. A very similar pattern is seen in a question specifically focussed on unemployment benefits, as Figure 2 shows.

Figure 1 ‘If welfare benefits weren’t so generous, people would learn to stand on their own 2 feet’

""

Source: British Social Attitudes Survey. ‘Agree’ shows the percentage of respondents who either agreed or strongly agreed with the statement. ‘Disagree’ shows the percentage of respondents who either disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement.

Figure 2 ‘Benefits for unemployed people are too high/low’

""

Source: British Social Attitudes Survey.

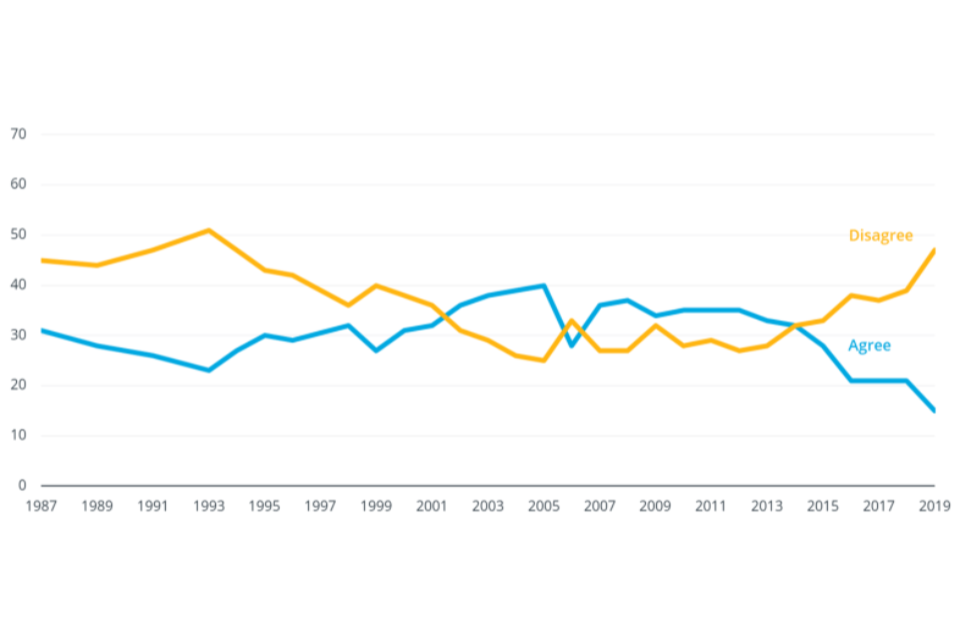

Furthermore, when the question is asked in terms of whether people agree or disagree with the statement ‘people who receive social security don’t really deserve help’ (shown in Figure 3), the gap between those who agree with the statement and those who disagree has since the 1990s never been remotely as large as when a related question (Figure 1) is asked in terms of ‘welfare’. The recent gap – i.e. the predominance of those who believe that those receiving social security do need help – is striking.

This in our view reinforces the argument that the language used here matters – and it is time to re-assess the concept of ‘social security’ and indeed re-instate that language. These trends in attitudes might also provide a reason why contributory benefits might be strengthened going forwards rather than, as the path of history would suggest, weakened further.

Figure 3. ‘Many people who receive social security don’t really deserve help’

""

Source: British Social Attitudes Survey. ‘Agree’ shows the percentage of respondents who either agreed or strongly agreed with the statement. ‘Disagree’ shows the percentage of respondents who either disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement.

Rates of working age benefits have been at historically low levels

While attitudes may be changing, the longer-run effect of policy makers’ decisions and public attitudes has been that financial support for the childless who are out of work has fallen to historic lows – on the basis that they should be in paid work. For the past decade until the April 2020 uprating, benefit rates for those with children have also been in decline relative to price inflation. The financial crisis of 2008 left a large structural deficit in the government’s finances that was in part dealt with by a large dose of austerity that affected benefit rates for all of those of working-age, as well as spending on many public services.

Between April 2010 and April 2013, some benefits were frozen and that was then followed by an increase of only 1% for 3 years running in working-age benefits followed by a 4-year freeze in cash terms. As a result, prior to the COVID-related increases, the rates for what might be dubbed the means-tested safety net benefits – JSA, Income Support and ESA and their equivalents in Universal Credit – were 9% below where they would have been if uprated by the Consumer Prices Index since 2010. Child benefit rates, and many of the elements of the Working Tax Credit, would have been between 13% and 16% higher on the same basis.[footnote 17] Other measures have had the effect that, while 9 out of 10 families were eligible for the child tax credit in 2010, in 2015 that was reduced to only 5 out of 10.[footnote 18]

Those were the rates ahead of the £20-a-week ‘temporary’ increases in Universal Credit in response to the pandemic. It is a measure of its impact for the childless non-disabled aged 25 and over who are out of work that the £20 increase is bigger than the cumulative real increase over the whole of the past 45 years.[footnote 19] For example, for a single, childless person the basic amount was, in real terms, £61.35 per week in 1975 to 1976 and prior to the pandemic was set to be £74.33 in 2020 to 2021: i.e. a total real- terms increase of just £12.39 prior to an additional £20 increase this year.[footnote 20] For singles and couples without children, depending on age, the temporary increase has raised the standard personal allowance by between 19% and 36%.[footnote 21]

For those with children, however, the percentage increases to overall income from the ‘temporary’ increase in Universal Credit are appreciably smaller – how much smaller depending on the number of children. The flat rate nature of the increase has given a larger percentage rise to those who would normally receive less from the benefit system. This raises a question. Had the increases been intended to be permanent, and designed with more time to spare, would they have been targeted differently?

The language used about the benefit system has changed

Aside from the benefit changes outlined, the language around the system has also changed over the years. Only rarely these days do politicians – or indeed the public – refer to social security. The phrase has largely fallen out of the political lexicon, being replaced by welfare. ‘Welfare’ in this context is essentially a term adopted from the US. As was pointed out at the webinars, it carries connotations close to the opposite of its original meaning. Not so much to fare well, as to be someone in receipt of somewhat stigmatised benefits – ‘in need of welfare’. One sign of that is that the traditional means-tested benefits – ‘welfare benefits’ – tend across the board to have lower rates of take up than contributory ones, and that applies not just to working-age benefits but to Pension Credit, the main means-tested element of state financial support for pensioners.

The use of language matters. Not least currently. As the quote at the top of this report implies, those who unexpectedly lose their job for the first time are looking for a degree of security in uncertain times, not for a handout for ‘scroungers’, as some parts of society have labelled the working-age benefits system (though, interestingly, not the benefit system for pensioners). It is worth recalling that tax credits, which are mainly in-work benefits,[footnote 22] were so named to distinguish them from out-of-work benefits, in an effort to avoid the stigma that some attach to means-tested out-of-work payments.

Universal Credit – also a benefit – adopts the same presentational approach: it is called Universal Credit, not Universal Benefit. Indeed, the move in 2010 to Universal Credit, as both an in-work and out-of-work benefit, reinforces the idea that we should return to the language of social security. It provides support – and therefore security – for those in low-paid work. With unemployment low ahead of the pandemic, many more recipients of Universal Credit would have been in paid work than would have been receiving the out-of-work elements, once it was fully rolled out. Language, in both politics and the benefit system, matters.

The UK’s benefit system for those who lose jobs is much less generous than the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) average

The webinars also heard that the UK’s system is appreciably less generous, and operates very differently, to that in many other countries. Social insurance contributions elsewhere are higher than NICs in the UK but in return workers receive earnings-related benefits.

Thus in many other European countries, the contributions individuals pay into their social security system do much more to preserve their and their family’s income, at least initially and usually for many months, than the UK’s. In the UK people essentially fall back on to a flat-rate – and largely means-tested – safety net when they lose a job. Across the other 36 members of the OECD, benefits are typically more earnings related.

Table 1 sets out replacement rates in the UK against the OECD average. While the level of out-of-work benefits available in the UK has been broadly the same whether or not someone has a contributory record, it is a very different picture in most other OECD countries. On average across the OECD, the income someone will receive if made redundant is substantially higher if they have an adequate contribution history than if they do not.

Table 1 Replacement rates for different family types for workers on average earnings, 2018

| UK | OECD average – Without contributory benefits | With contributory benefits | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single, no children | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.55 |

| Single, 2 children | 0.35 | 0.40 | 0.66 |

| Couple, no children | 0.20 | 0.31 | 0.57 |

| Couple, 2 children | 0.41 | 0.47 | 0.66 |

Source: Bourquin P and Waters T, ‘The temporary benefit increases beyond 2020–21’, Chapter 8 of C. Emmerson, C. Farquharson and P. Johnson (eds) IFS Green Budget: October 2020, Institute for Fiscal Studies. Based on a family with one worker paid average earnings. ‘With contributory benefits’ shows what replacement rates would be for a worker receiving unemployment benefit who is aged 40 and has worked uninterrupted since age 19. All figures relate to the second month of unemployment. Ignores housing benefits. Children are 4 and 6 years old. The OECD average is measured across 36 OECD countries (Turkey is excluded because of lack of data availability). The replacement rate measures out-of-work income as a share of in-work income.

Table 1 shows, for example, that a lone parent with 2 children in the UK who had been on average earnings receives around 35% of their previous wage, against – for a period – 66% on average for those who have paid into contributory benefits in the OECD. Even without a contribution history, the replacement rate is on average still 40%, which is considerably above the UK’s 35%.

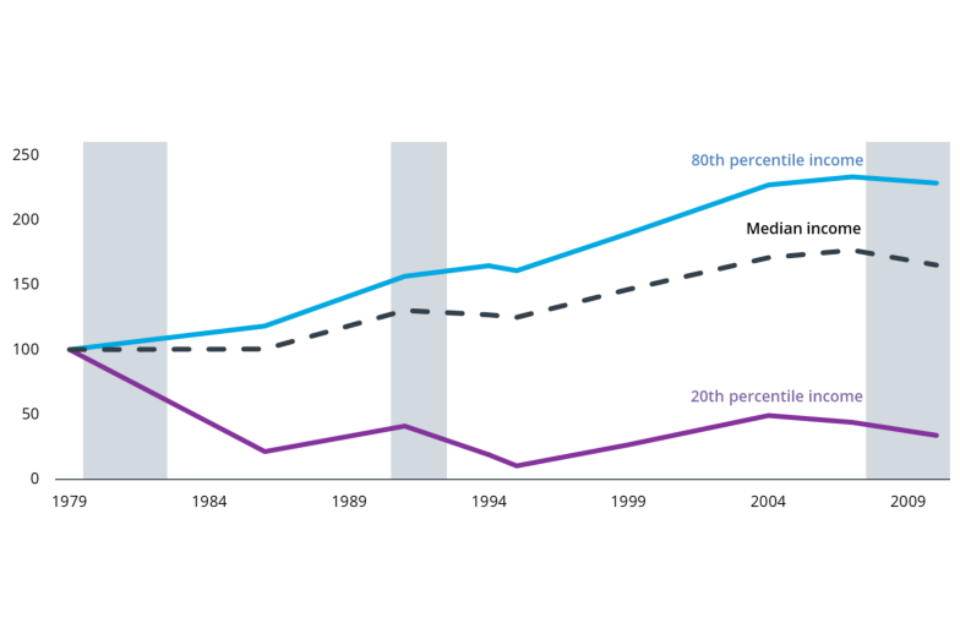

The evidence suggests that low replacement rates lead to longer term damage

At the webinar the point was made that these lower replacement rates tend to leave the UK more scarred by recessions.[footnote 23] Low levels of benefit and the DWP’s ‘work first’ approach can encourage individuals to take any job, rather than one well-matched to their skills and experience. So, aside from the initial financial blow of unemployment, the better skilled can end up in lower-paying jobs with limited promotion or progression prospects, with a lasting impact on productivity and wages. The need for individuals to retrench rapidly in the face of unemployment also takes spending out of the economy. It was also argued – and this was in October, prior to the substantial extension of the CJRS – that the UK’s low out-of-work benefit levels will make it harder for the government to withdraw from the new COVID-era employment support schemes, because doing so will have a much larger impact on living standards and family expenditure in the UK than it would in countries with, at least initially, more generous out of work benefits. There is also at least a suggestion from analysis done by the OECD (see Figure 4) that the low levels of support offered during recessions may be a longer-term driver of income inequality in the UK. In other words, there looks to be a wider economic cost, as well as that to those out of work on low incomes, from the UK’s low levels of working-age benefits.

Figure 4. Real-terms market incomes of working-age households (index, 1979=100)

""

Note: Periods of recession are shaded grey.

Source: OECD (2014), The crisis and its aftermath: a stress test, Figure 1.6.

A chance to think afresh about the UK’s approach to benefits and employment services

An absolutely primary aim of the DWP is to get people back into paid work in the wake of the pandemic. But the international comparisons, the language in which the benefit system is currently discussed, the boost from the additional spending on Universal Credit during COVID-19 as well as the changes to the economy that has caused, the continual shift over the years towards a more means-tested and conditional working- age benefit system centred around a ‘work first’ approach – all these factors, combined with the pandemic, offer an opportunity, and indeed provide a requirement, to at least think again about both the benefits system and employment services. How could they, and how should they, adapt to COVID-19 and its aftermath?

Strengthen contributory benefits

The webinar debated long-term versus short-term generosity in the benefits system. In the past, those who remained on means-tested benefits for long periods of time received a higher rate. They did so in recognition that more durable goods – overcoats, shoes, washing machines – that would see people through shorter spells on benefit would eventually need replacing and so living costs would become higher. Those longer-term rates have disappeared, in part because they were seen to undermine work incentives and in part because the benefit system, particularly for those with more severe and therefore often longer term health problems and disability, has been recast to provide more support for those who are not expected to prepare for work.

The debate in the webinars tended to favour the exact opposite approach to that taken over the past couple of decades: namely participants favoured providing time-limited additional generosity, as is the case in many other countries where time limited more generous contributory benefits are provided. The benefits of this are believed to be 2-fold. First, it would reduce the immediate impact of job loss and the resultant economic scarring. Second, it would retain spending in the economy during recessions – those on lower incomes spend higher proportions of their income than those able to save and job loss, by definition, lowers income.

The point was made by some in the webinar that there is a case for strengthening what remains of the working-age contributory benefits. When big macro-economic shocks happen – either nationally, or on a much smaller scale locally if a large employer suddenly closes – contributory benefits provide a stronger buffer against the drop in income that job loss entails. Contributory benefits are not subject to a savings rule and they allow a working partner to carry on earning without a means test. That is good for the individual and good for the family if they have one. It is also good for the economy when abnormal shocks such as the pandemic occur – with more people in better-paid jobs suddenly losing them – because people are likely to reduce short-term expenditure by less than would be the case if they relied purely on means-tested benefits.

The £20-a-week uplift in Universal Credit has been widely welcomed. But a similar increase was not put into the contributory versions of JSA and ESA (or given to those receiving the legacy means-tested versions of these benefits prior to the pandemic). This was because, according to the government, their less automated nature made that impossible to do quickly. Thus, the standard weekly rate for someone over 25 on contributory JSA remains at just over £74 a week, against just over £94 for those on UC. This hardly seems equitable, when those who qualify for contribution-based JSA do so precisely because they have directly paid into the system. Whatever happens to Universal Credit rates going forwards – for example whether or not the ‘temporary’ £20 increase is made permanent – the contributory JSA rate should not be left below the rate of UC.

People losing jobs that were sufficiently well paid for them to have paid NICs will, the webinar believed, be highly motivated to find new work. Providing them with at least a short-term cushion that is independent of their partner’s earnings and does not require them to run down savings reduces the immediate financial hit of a job loss. Allowing it once again to run for a year, rather than 6 months, would reduce the pressure to take any job – allowing them to stand a better chance of finding a job that would enable both them and the economy to benefit from their skills.

It would also reduce housing pressures. Many private rental contracts are for a year, and while some have 6-month break clauses, sudden pressure to find lower-cost housing only complicates the lives of those already facing reduced income and needing the time to find new employment. Furthermore, encouraging claimants to move quickly to cheaper areas, where well-paid jobs may be scarcer, could be counterproductive.

There is some precedent in the existing system for giving people more time than the 6 months for which contributory benefit is paid, namely in the 9 months given to people moving out of paid work before the household benefit cap bites. And it is worth noting that both the CJRS and, for its brief existence, the Job Support Scheme are or were both earnings-related – the former paying 80% of earnings up to a cap and the latter 67%.[footnote 24] These, of course, are not strictly speaking benefits. They are paid to employers to support jobs. But their effect is earnings related support for employees.

Tackle the savings rule

As already noted, one of the surprises facing some of those seeking to claim Universal Credit for the first time was the discovery that a claim is disbarred if the household – not the individual – has £16,000 of savings. Indeed, the award is reduced until savings fall to £6,000.

In more normal times, when the move out of work and back into it on Universal Credit tends to affect the lower-paid most, the savings rule has relatively little impact. Average household savings in the UK are only around £7,400. The average, of course, hides the fact that many people, and in particular younger households, have much less. For example among working-age households half of single childless households have less than £1,700; half of couples with children have less than £3,700, while half of lone parents with dependent children have less than £300 in liquid financial assets.[footnote 25]

In a typical month in 2019, ahead of the pandemic, it is reported that only around 500 Universal Credit claims a month – some 6,500 out of almost 2.9m claims made that year – were not awarded because claimants had £16,000 or more in savings. During the early months of the pandemic, however, it was reported that the numbers hit by the savings rule rose ten-fold as people in better paying work either lost their jobs or had a significant fall in earnings and applied for UC.[footnote 26]

That raises the question of what – if anything – should be done about the savings rule. It should be acknowledged that there is a policy dilemma here. The state wants to encourage saving for a whole range of reasons that include individuals and families being able to invest in their future, save for retirement and withstand financial shocks caused by whatever reason, not just unemployment. But it can feel immensely harsh that those with some modest savings have to run them right down when they may have been saving to pay for education, a house, their retirement, or indeed another worthy cause ahead of unexpected unemployment. Against that, the taxpayer has a very real interest in there being some sort of saving limit to prevent those who are asset rich but income poor claiming state benefits. Furthermore, if the desire is to target Universal Credit resources to those who have low incomes across their entire lives, then an asset test can help to achieve that.

The savings rule can be particularly punitive for those who have lost work in later life – say in their fifties – when savings being built up for retirement have to be run down at a time of life when there is limited time available to restore them. Pension assets are excluded from the means test. But that in turn can be particularly harsh on the self- employed. Because their income is more volatile they are more likely to save in liquid forms such as an ISA (including Lifetime ISAs) to save for their retirement – given that, by definition, they do not have an employer to enrol them automatically into a pension and then make the required employer contributions.

The £16,000 limit has not been raised since 2006. At that time, it was roughly doubled in cash terms, having not been increased since 1990.[footnote 27] Had the limit kept pace with the rise in prices since 2006 it would be close to £23,500 now. By contrast the ISA contribution limit – into which many of the self-employed might decide to save for retirement – was £7,000 a year in 2006, but is now £20,000 a year. In other words, the annual ISA contribution limit has gone from being less than half the capital limit in means-tested benefits to 25% larger.

The issue of indexing – raising thresholds and limits in line with prices or earnings – goes well beyond just the savings rules. It applies equally, for example, to the household benefit cap, child benefit withdrawal thresholds and UC’s housing element. It also applies equally outside social security, for example in the means-testing of social care.[footnote 28] The failure to index means that growing numbers get caught by limits that become progressively less generous relative to prices and earnings – and indeed, in the case of social security, to the relative standard of living provided by the base amount of out-of-work support. There is a case for raising the savings limit and indexing it.

There is also a strong case that the Lifetime ISA should be excluded from the savings limit. It is there to provide savings for a house or for retirement income and the government tops up the saving, up to a cap, by 25%. As already noted, individuals, and particularly the self-employed, use it as a form of pension saving, and other pension savings are not included in the savings rule. It seems bizarre for the taxpayer actively to contribute to these savings but then demand that they are run down to qualify for Universal Credit. In addition, people can find themselves in the distinctly odd situation where, if they had used the saving to help buy a house just ahead of losing their job the money would not be counted against this means-test, but if they are still saving it does.

What to do about the “temporary” increase in the generosity of Universal Credit

There was strong support from many at the webinars for the additional funds put into Universal Credit through the £20-a-week extra on the standard allowance – brought in in April 2020 and due to cease on 31 March 2021 – to become permanent, although, at the time of writing, this does not appear to be the chancellor’s intention. The initial cost was £6.6 billion.

For speed and simplicity’s sake, the £20 increase was, understandably, flat rate. But, as already noted, that means that it has given a larger percentage rise to those in the benefit system to whom it would normally provide less. In percentage terms it is worth appreciably more to singles and to couples without children than to those with children – and there has been growing concern about child poverty.

We acknowledge the political difficulty of taking away something that has been given, even if it was said to be given on a temporary basis. Its introduction, however, did at least appear to be a tacit acknowledgement that benefit rates had become too low (as we have noted above). There is a strong case for maintaining this expenditure, even if, as the ‘temporary’ increase is reviewed, there is a case for changing the way it is distributed between different types of claimant.

Furthermore, as the economy recovers from the pandemic, and the numbers claiming Universal Credit because of unemployment and reduced earnings start to decline, there is a case for diverting some of the public expenditure that will then be saved into other improvements to Universal Credit.

For example, it has long been a feature of Universal Credit that it provides weaker incentives to have a second earner in a household than is the case with tax credits. Improving the work incentives for second earners in Universal Credit could help tackle child poverty since, at lower incomes, 2-earner families, particularly those with children, are less likely to be defined as being in in-work poverty than single- earner families. In the same vein, if the wish was to improve work incentives, it would be better to put money into higher work allowances and/or a reducing the taper (the percentage by which Universal Credit is withdrawn as income rises), rather than increasing the standard amount.

In addition, before the pandemic, several other improvements to Universal Credit were canvassed, including some with cross-party support. At present, new claimants of Universal Credit who are already on JSA, ESA, Income Support and Housing Benefit receive a 2 week non-repayable ‘run on’ of benefit which substantially reduces the impact of the 5-week wait for the first payment – thereby also reducing the need for and scale of repayable advances. The cost of those run-ons is time-limited because, once Universal Credit is fully rolled out, no-one will be transferring from the legacy benefits. At present, however, those starting entirely new claims, and those transferring from tax credits because their circumstances have changed, receive no such run-on payments. The absence of such a payment for those transferring from tax credits is a transitional issue because all those on tax credits are to be migrated across to Universal Credit – in theory by 2024, although how far the pandemic will affect that already long delayed timetable is so far unclear. A ‘starter payment’ for entirely new claims, who will otherwise face the 5-week wait, would, however, be a permanent cost.

There is an endless, somewhat semantic, debate about whether the advances create a debt or merely result in the same sum being paid to claimants over the first year but in differently sized instalments. But in keeping with our view that the benefit system would be strengthened by greater time-limited generosity at the outset, a starter payment would reduce the need for advances. It would also be in line with the recognition that the government has already made, by introducing the run-ons, that the 5-week wait is causing hardship and creating debt, even with the availability of advances. Measures would need to be taken to reduce the risk of fraudulent starter payments. But that looks to be manageable by defining the starter payment as a loan that is then written off say 3 or 6 months in, once a claim is established as genuine.[footnote 29]

The webinars also noted one or 2 particular features of Universal Credit that are not working well but should be relatively easy to fix – for example, that a tax rebate can raise savings to the level to disqualify people from receipt of UC, as can savings that are earmarked to pay a forthcoming tax bill. Allowing that to happen makes little sense.

As outlined above and according to the British Social Attitudes Survey, the public’s view that unemployment benefits should be more generous is nothing like as strongly held as it was in the 1980s (see Figures 1, 2 and 3. But anything that made the benefit system more generous and strengthened the bits of the working-age contributory system that remain would still appear to be going with the tide of public opinion – which may shift further as unemployment climbs towards the levels seen at previous peaks.

Helping people find jobs

Providing financial support for people when they lose jobs is one thing. Getting them back into work – clearly seen by the DWP as a key priority – is another.

In the longer run, do we once again need a Ministry of Labour?

From the mid-1990s on, central government’s employment services have increasingly been tied to benefit receipt. In the early 2000s the employment part of the Department for Education and Employment was merged with the then Department for Social Security to create DWP. This marriage, and DWP’s essentially ‘work first’ approach, has been shown to be effective at getting people back into work, at least in times of relatively low unemployment.[footnote 30]

But, as already noted, one effect of the pandemic has been to throw out of paid work larger numbers than usual of people who are caught by the savings rule and therefore do not qualify for Universal Credit. Once it is clear they do not qualify, for that or for other reasons, it is not entirely easy to discover on the government’s website GOV.UK that they might be eligible for contributory JSA. Or indeed that they can claim national insurance credits while unemployed – if they comply with the job search requirements for JSA. The department’s website does not seem actively to point people to the possible qualification for contributory JSA.

Those who are unemployed but not on means-tested benefits can use the digital ‘Find a Job’ service, the modern equivalent of the original Unemployment Exchange. But typically they do not have access to any other DWP services such as a work coach and the resources to which work coaches can point, including those that can help people raise their earnings or, in the jargon, achieve the pay progression that is one of the goals of Universal Credit. That is in contrast to the public employment services in many other countries.

Indeed, one further effect of the creation of DWP is that England is unusual internationally in no longer having a Ministry of Labour or its equivalent – one with a wider remit than just addressing opportunities for working-age individuals receiving benefits. Responsibility is instead split across at least 5 departments. The Home Office deals with immigration; the education department is involved in training, as is the department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy which also has responsibility for the minimum wage; DWP’s employment services deal with those on benefits.[footnote 31] In England, the Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC) and the NHS have important roles in helping those with health issues that can make getting into, and staying in, work harder. Indeed there is already a joint DWP/DHSC taskforce, and it is almost certain that the mental health toll levied by the lockdowns will exacerbate challenges at a time when the NHS is already under huge pressure, both from the virus and the backlog of other treatments that have built up during the pandemic.

There are differing departmental responsibilities in the devolved nations, with further complicated overlaps of responsibilities.

Behind all this, of course, sits the Treasury – which is not just the source of funds but will always have its own large impact on labour market policy (as indeed the furlough scheme and other employment support measures during the pandemic illustrate vividly).

The department is already taking steps to achieve closer working but one message that emerged forcefully from the webinars was that an urgent priority for the government is to go further in bringing the various labour market functions of the departments closer together. The middle of a crisis is not a time for a major machinery of government change, not least because there is good evidence that such changes lead to lower productivity and effectiveness for a time.[footnote 32] But there clearly is a need to co-ordinate well the various aspects of these departments’ work that affect the labour market.

Alternatives to a machinery of government change include a joint committee of civil servants overseen by a minister, with clear accountability, or a cabinet committee.[footnote 33] Should the latter be chosen it would need to be more focussed than the existing Domestic and Economy Implementation Committee, which has too wide a membership. That would imply either a new cabinet committee or using the existing Economic Operations Committee, but with a wider membership.

The essential point here, however, is that greater co-ordination of the work of the various departments involved needs to be achieved to rise to the challenges posed by the labour market effects of the pandemic. And whenever the next substantial machinery of government change is embarked on (which, to stress, we are not recommending for now) careful consideration should be given to bringing together at least some of the different aspects of labour market policy into a single department.

However, a departmental restructure can never be a panacea and it would be impossible to bring together all aspects of policy that touch on the labour market – not least because the Treasury will always play a crucial role in economic management. Therefore, ministers and officials will always need to ensure that the various parts of government that are responsible for different aspects of labour market policy work more closely together.

The answer to restoring employment is local as well as national

The other important message was that there is a strong role for the local here, supporting local authorities’ economic and employment plans, as well as using the network of 38 employer-led Local Enterprise Partnerships in England and the equivalent agencies in the other nations of the UK.

Councils know – or should know – their local labour markets well and are already working with the government’s Kickstart programme. Local authorities, or Jobcentres themselves, are able to act as convenors to bring together employers, the Jobcentres, the National Careers Service, the Education and Skills Funding Agency and local further and higher education providers.[footnote 34] It is crucial that someone makes this happen.

One important tool that could help local authorities is rapid automated access to DWP’s Universal Credit data, with more detail than is currently published. Local authorities currently have access to Housing Benefit data and have been using it to identify vulnerable low-income families to provide, for example, support that can help prevent them spiralling into debt. But councils are losing such information as working-age housing benefit is rolled into Universal Credit and, despite pleas from local authorities, they have much less access to individualised data on Universal Credit claimants. The councils argue that the legal powers exist to allow such data to be supplied.[footnote 35] Providing them with details of where Universal Credit claimants live, their age, gender, number and ages of children, prior occupation and any disabilities would, we heard, allow more rapid local responses to changing circumstances and would allow local employment initiatives to be well-targeted.

The Office for Statistics Regulation made the same point in its recent assessment of the benefit statistics:

There is a lot of untapped potential in DWP’s benefit statistics… COVID-19 has brought to light users’ interest in information on the characteristics of individuals or households claiming benefits. Solving these data gaps would aid understanding of which groups have been most impacted by the pandemic so that services and policies can be targeted effectively.[footnote 36]

DWP itself is taking on an extra 13,500 work coaches in response to the huge rise in the Universal Credit caseload. Turning them into effective work coaches – able to provide genuinely effective advice on job and training opportunities, as opposed merely to ensure that individuals are undertaking job search – will take time. Certainly, much is being asked of them – and this is a role which, at least as of January 2018, was advertised as paying between £24,000 and £26,000 a year.[footnote 37]

The future course of the pandemic will also raise questions about how far, and how vigorously, DWP enforces conditionality – the requirement to look for, and take-up, work and the imposition of sanctions for those failing to comply. Much conditionality was suspended during the first wave of the pandemic but has since been partially re-instated.

Conditionality clearly does need to return in time. There should, however, be flexibility over where, when and how vigorously it and the corresponding sanctions are applied. We understand that it is DWP’s intent but it will be important not least if Jobcentres are to work closely with local authorities to understand their local job markets. We are also clear that there should be no return to the punitive, and unproductive, sanctions regime that operated between 2011 and 2015, peaking in 2013. Following criticism from the NAO and an independent government commissioned review, it was, sensibly, moved away from.[footnote 38]

An appealing proposition at the webinars came through a quote from Ernest Bevin, the Minister of Labour, to staff from employment exchanges during the Second World War:

If something needs to be done quickly, just get on with it and do it. Don’t wait for headquarters to give you instructions. And if you make mistakes I will back you up so long as you respond quickly to the immediate circumstances in your area.[footnote 39]

As we noted in a previous piece of joint work between SSAC and the Institute for Government, both clients and the department’s own frontline staff can often have better insight into what needs to be done locally than policy designers in Whitehall. This needs to be fostered, for example through encouraging work coaches to make appropriate use of the flexibilities available to them, particularly in these circumstances.[footnote 40]

Services need to become more digital

DWP has made real progress in making services more digital – notably for Universal Credit but also in the way the Child Maintenance Agency now operates. More needs to be done and there are some silver linings even amid the pandemic. Private recruitment agencies faced lockdowns like everyone else that prevented face-to-face meetings. But they have found that online contacts work well. The webinar also heard that there is international evidence that online support for job search can work well in publicly run services. Estonia might not be the first country to which many people in the UK would automatically look to learn lessons but, while Universal Credit is now essentially a digital service, the webinar heard that Estonia has gone much further. It provides remote career guidance via email, phone and interactive web-based platforms for older school pupils and those aged up to 26.[footnote 41]

Interestingly for those worried about digital exclusion, phone is the most popular form of contact in the Estonian system. It offers online training courses, along with digital tools for both the public employment service and alternative providers. These can profile a client’s chances of entering employment, and for exiting it once employed, pointing to the support services they therefore need.[footnote 42] Given that tech is one of the areas that has not only become more important during the pandemic but is likely to grow further, the webinars also heard that some countries undertake an audit of digital skills among the unemployed, linked to training courses to raise them. Those countries include Estonia but also Australia, where such a scheme is starting to be rolled out.[footnote 43]

Government support for re-training is needed

The UK already has a vibrant tech sector, which will need additional recruits, and the government should embrace approaches to digital skills audits and training of the sort already used in other countries. There will also be a need for government support (such as vouchers) for training by employers in other sectors, with the important proviso that the training that these support must be carefully regulated to ensure that it is of sufficient quality. This will, inevitably, involve an element, if only in broad terms, of the government ‘picking winners’ in the sectors where it decides to support such schemes. But given the likely impact of the pandemic on employment, there is a case for that.

In the past, various levels of government have used their contracting ability to influence unemployment. For example, past home insulation programmes have included in the contract a requirement to take on, and if necessary train, people currently unemployed. If there is to be a significant investment in green technologies, for example, such conditions could again be used and should be actively considered.

Particular groups must not get left behind

The webinars also debated priorities. Attendees were clear that, despite the large- scale impact that the pandemic will have, it is crucial that particular groups do not become permanently detached from the labour market – as happened in the 1980s. Measures the government has already announced – the Kickstart programme for the younger unemployed modelled on the previously successful Future Jobs Fund,[footnote 44] and the Restart programme for the long-term unemployed – address 2 of those groups. Both should reduce the scale of long-term unemployment with all the attendant damage that does to individuals, families and the wider economy through economic scarring and a larger on-going benefit bill. But the webinar also noted that more intensive efforts to help those with health and disability issues tend to get side-lined when unemployment rises only to become a focus again as it falls.

There were mixed views at the webinar on how far the government should seek to segment those out of work into different work streams, so to speak. Some recalled the New Deals of the late 1990s and early 2000s that provided separate support streams for lone parents, young unemployed, the sick and disabled and even, briefly, for musicians. Some argued that such an approach allowed work coaches to specialise and be more effective. Others felt that individual needs can often cross such categories, with the labelling effect running the risk of creating stigma. One option might be to ensure, if a more generalised approach is taken, that work coaches have easy recourse to specialists within local Jobcentres or Jobcentre areas who have additional expertise in for example health problems or the challenges for the self-employed.

There is a public/private debate over the provision of employment services

DWP has recently detailed a new framework it will use to contract with external providers for Employment and Health Related Services, and it seems likely that DWP will extend its use of the profit and not-for-profit sectors in response to the pandemic. Indeed, this might be unavoidable given the scale of resources that could be needed. In doing so, it needs to draw on not just experience of the Work Programme, but on international evidence as to how best to ensure that excessive risk, particularly financial risk, is not inappropriately transferred to smaller, often voluntary-sector, providers who can otherwise be among the most effective in getting those with health and disability issues into work.

Experience with the Work Programme shows that incentives in contracts designed to achieve one outcome can in fact achieve the opposite if not carefully designed.[footnote 45] It was also noted that if the DWP faces a challenge in getting its expanded number of work coaches up to speed, the same will apply to both the for-profit and not-for- profit sectors. There were mixed views at the webinar – as there are mixed views in the literature[footnote 46] – over the relative effectiveness of using the for-profit sector to provide employment services at scale. Some saw advantages in that. Others argued that the task can be undertaken equally well in the public sector. All we would do is counsel against any blind faith that large private providers hold all the answers, not least because we see local responses, involving both local and nationally based charitable and not-for-profit enterprises, having a key role to play.

Recommendations

We make 3 sets of recommendations as steps towards improving the structure of the UK’s system of benefit and employment support in the light of issues that the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted. As already noted, these have not been costed because, in general, we are more concerned about the direction of travel than producing at this stage highly specified recommendations.

First, there are several ways in which the current system could be fine-tuned to make it more effective.

- the £16,000 savings rule in Universal Credit needs to be updated. Savings at that level debar receipt of UC whether the claimant is in or out of paid work. The limit has not been increased since 2006. Had it risen in line with prices it would be nearer £25,000. We recommend it is increased to £25,000. Funds held in a Lifetime ISA – a longer-term saving instrument – should also be exempt from the savings rule

- the savings rule should then in future be indexed automatically each year so that its value is maintained over time. This should also apply to all other such thresholds and limits, including the household benefit cap, child benefit withdrawal points and local housing allowances, the last of which was frozen in cash terms in the autumn

- when individuals or households are debarred from UC by their savings, the government should much more actively – on its websites and in its contacts via Jobcentres – point individuals to the possibility that they may qualify for contribution-based JSA or ESA

- the government should consider introducing a non-repayable ‘starter payment’ for new claims to Universal Credit, where a run-on of legacy benefits is not otherwise provided. Its precise level, and the steps needed to reduce the risk of fraud, still need to be debated and designed. But as with our recommendations for contributory-JSA below, this would provide a little more initial generosity in the face of unemployment, easing the 5-week wait for the first payment and reducing the need for, and scale of, repayable advances. The government has already conceded the principled need for such a payment in the 2 week ‘run-ons’ provided for existing claimants of non-contributory JSA, ESA, Income Support and Housing Benefit

- many benefit rates over the 45 years prior to the pandemic had fallen appreciably relative to average earnings and, in the last decade, in real terms. In some cases, they had reached historic lows. This is the long-term background that has led to arguments being made in favour of the ‘temporary’ £20-a-week (or £1,040-a-year) increase to the standard allowance in Universal Credit being made permanent. Allowing the increase to expire would doubtless be difficult for – and may well surprise – many recipients. For understandable reasons of speed and simplicity the temporary Universal Credit increase was a flat rate amount. This means it is not as well targeted as it could perhaps have been if there had been more time available. In percentage terms, it is worth appreciably less to families with children than to childless singles and couples and there has been growing concern over poverty amongst in-work families. Therefore, we recommend that the level of support provided by Universal Credit to those out of work is carefully reviewed in the context of the government’s objectives for reducing poverty. Any enhancement to Universal Credit should also apply to legacy benefits and (as argued below) to contributory benefits

- as the unemployment costs caused by the pandemic start to fall, however, some of those savings could be used to adapt Universal Credit (and legacy benefits) to the changing needs of both claimants and the economy. They could be used, for example, to increase work incentives either by increasing the work allowances and/ or reducing the taper in Universal Credit and/or providing stronger incentives than Universal Credit currently does to encourage second earners: a move that would reduce in-work poverty

- the pandemic has shown that the system can change effectively (and dramatically) if it needs to. In future, it should be much more open to continuous improvement, greater transparency and flexibility

Second, the COVID-19 experience has shown that the approach for managing the return to employment and the sectoral shifts involved needs to be systemic. There is a big policy and organisational question about how we deliver the return to employment; this is likely to be the most important emerging challenge in 2021.

- the differential impact of the pandemic on different sectors of the economy raises, to a higher level than usual, the need for re-skilling and re-training. Some people will need to change sectors. The UK has become unusual by international standards in no longer having a Ministry of Labour or its equivalent. Responsibilities for education, training and labour market policy reside in multiple different departments (including DWP, BEIS, DfE and MHCLG). Health issues lie with the Department of Health and Social Care and the NHS, while the Treasury has a clear interest in all aspects of labour market policy. Now is not the time for machinery of government changes. Departments understand the need to work together and are already doing so but a fully co-ordinated response is essential, especially around training and re-skilling. That could be achieved by either an inter-departmental joint committee or a cabinet committee

- the already announced Kickstart (providing work subsidies for the young unemployed) and Restart (aimed at the long term unemployed) programmes are welcome. But a purely centralised response it unlikely to be fully effective. Jobcentres need to work even more closely with local government – with its knowledge of local labour markets and its ability, alongside the Jobcentres, to bring together employers, education providers and career advice services. To assist them, DWP should seek to provide, automatically, much more detailed data as swiftly as possible on the local UC claimant population – including information on last job held, gender, family make up, disabilities, and whatever information it holds about skills. DWP should also learn from other countries that conduct audits of the digital skills of claimants, provide training to enhance them while also offering online and telephone delivery of careers advice that is available more widely than to just those claiming benefits

- there will, as already noted, be a significant need for re-training and re-skilling, not just for Universal Credit claimants but for those who have lost jobs but whose savings debar them from benefits. Vouchers for training could help there, even though that will involve an element of ‘picking winners’ – that is, choosing the sectors to which they will apply, while ensuring the eligible training is carefully regulated to make sure that it is of sufficient quality. In the past it has been made a condition of some local and central government contracts that individuals are taken on for training. That approach can be used again

- the government is likely to have to enlist the independent sector in delivering ‘welfare-to-work’ programmes. It is crucial that DWP learns lessons from the experience of the Work Programme and from international evidence about how to contract effectively with external organisations – including ensuring that undue risk is not transferred to smaller organisations, whether for profit or not-for-profit. Getting the right balance between ‘payment only for results’ and service payments will be crucial

- greater conditionality should return within Universal Credit. But there should be flexibility locally in how and when that is applied. A constructive relationship between work coaches and claimants in finding not just any job but suitable jobs is likely to yield better enduring results for both individuals and the economy than merely enforcing work search conditions

Finally, although this is our shortest set of recommendations, it is in many ways our overarching: that there should be a reassessment of what the benefit system is for and a re-adoption of the language of social security. COVID-19 has shown how important out-of-work benefits can be in the face of macroeconomic shocks for those with usually more secure jobs. The system – from low levels of benefit and tight restrictions of savings – has been found wanting by those who believe they have ‘paid into’ the system but have now lost higher-paying jobs or face losing them.