United Kingdom Food Security Report 2021: Theme 3: Food Supply Chain Resilience

Updated 22 October 2024

Part of the United Kingdom Food Security Report 2021

Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 19 of the Agriculture Act 2020

© Crown copyright 2021

ISBN 978-1-5286-3111-2

This chapter of the UK Food Security Report looks at food security in terms of key infrastructure underlying the supply chain. Sourcing and supplying food to consumers in the UK is dependent on a complex and interacting web of systems. The theme considers how efficient and resilient systems are to transport, store, manufacture, and sell food on its path from commodity to consumers. It describes the potential threats and vulnerabilities to the sophisticated ‘just-in-time’ supply chains underlying the modern food system and how industry and government collaborate to prepare for and respond to issues.

In terms of this theme, food security means a supply chain that is consistently able to deliver adequate quantities of food, both through preparing for disruption and having the capacity and flexibility to respond effectively to unexpected problems. A resilient supply chain is robust and resilient, possessing an ability to recover from disruption and which can re-orientate to alternate outcomes when necessary.

Key Messages

-

The UK is resilient to potential shocks in the food supply chain. Supply systems, which are owned and operated by the private sector, are adaptable and flexible in responding to problems. Government monitors risks and works with industry to respond to emerging issues and maintain supply chains.

-

Notable risks to the supply chain stem from its dependence upon other critical sectors including energy, transportation, borders, labour, key inputs (chemicals, additives and ingredients), and data communications. In addition, the threat of cyber-attack to UK businesses, including those in the agri-food sector, is significant and growing.

-

The food and drink sector’s dependency on energy has marginally declined thanks to increased energy efficiency, whereas demand for energy in the agricultural sector has remained stable in the last 20 years.

-

Both EU and non-EU food imports, via all modes of transport, are well spread across a number of ports of entry, with no port having a dominant share. There is, however, a reliance upon the Short Strait for some food products, including fruit and vegetables (62% of fruit and vegetable imports arrive from the EU via the Short Strait), meats (43%), and dairy (41%). Only simultaneous disruption to several ports would be serious enough to have a material effect on UK food supply.

-

Securing sufficient labour at appropriate skill levels presents additional issues for the agriculture and food sectors. This includes short-term challenges, mainly due to high levels of absenteeism caused by coronavirus (COVID-19), and the longer-term challenges of filling vacancies across the agri-food sector.

-

A number of pressures in recent years, including the COVID-19 pandemic widely impacted the UK food supply chain. However, it also demonstrated the resilience held within supply chains, through an effective industry-led response, supported by government, to apply key mitigations to uphold continuity in the food supply chain.

The UK’s food supply chain is a highly complex system. It encompasses:

-

primary producers (for example, farming, fishing)

-

food manufacturing (for example, factories, process plants, mills, refineries, production plans)

-

logistics (for example, storage, distribution centres, transportation, ports)

-

wholesale and retail (for example, wholesalers, supermarkets, local businesses)

-

food services (for example, restaurants, cafes and caterers).

The importance of the UK food supply chain cannot be overestimated. Food is one of 13 Critical National Infrastructure (CNI) sectors in the UK. CNI sectors are “those facilities, systems, sites, information, people, networks and processes necessary for a country to function and upon which daily life depends”.[footnote 1] Every element of the supply chain, from food manufacturing to retailers, relies on physical infrastructure (buildings, vehicles, machines, power and data connections); digital infrastructure (the digital technologies that provide the cyber foundation for information technology and operations); human infrastructure (the skilled people who work in the supply chain and their working relationships with each other) and economic infrastructure (the system of finance, contracts and agreements that allow businesses to make money and operate productively.) Problems arising anywhere in this system can cause disruption to the supply of food.

In the UK the underlying infrastructure of the supply chain is owned and operated by private industry. The agri-food sector holds the capability, levers, and expertise to respond to potential disruptions.

Food supply policy including risks relating to resilience and security is devolved to each national administration. National Security and Counter Terrorism (CT) policy is a specific reservation under the Home Affairs heading. As lead departments for food as a CNI sector, Defra and the Food Standards Agency (FSA) manage those risks specifically relating to National Security and CT across the UK government. However, the role of government is an indirect one; to plan for and coordinate responses and intervene only where necessary to ensure the continuity of supply.

Energy and other critical resource inputs

All stages of the food supply chain, including production, processing, packaging, distribution, transport, retailing and the consumption of food itself, are dependent on their use of energy, other key inputs, and the functioning of critical interconnected systems. Fluctuations in the energy market also affect the prices of commodities or key inputs such as carbon dioxide (CO2). These fluctuations can therefore affect the economic viability of food businesses.

Over the last 20 years, energy demands for UK agriculture have remained consistent whilst demand for energy from the food and beverage sector has declined in the same period, indicating increased energy efficiency. This reduces the risk posed to businesses by disruption to energy supply or price shocks, but the sector remains reliant on energy sources, which can be volatile. The source of risks to the supply of electricity, natural gas, and petroleum products varies, with the most significant current risks being a reliance on imported natural gas.

Disruptions to major power networks in August 2019 highlighted the challenge of energy supply for the food system. Though the power disconnection itself was relatively short-lived, the knock-on impacts to other services were significant. This event demonstrated the need for essential service providers, including those in the food sector, to have robust business continuity plans in place for disruptive events such as power outages.

Certain goods critical to the functioning of the food supply chain are known as ‘key inputs’ and their supply is monitored by government. Although the provision of these goods is industry led, government supports industry in developing plans and mitigations to ensure continuity of supply.

Key inputs in the food supply chain are diverse and interface with an array of different markets. Challenges to access for these key inputs can come from a range of sources and causes. As an example, disruptions to CO2 supply occurred both in 2018 (as a result of unexpected maintenance and operational challenges for fertiliser plants) and 2021 (as a result of complex economic factors ultimately caused by an increase in the price of natural gas). Where necessary, government can make targeted interventions to support continuity of supply, and over the longer-term, work with industry to build resilience.

Transport and logistics

The transport sector plays a strategic role in connecting the UK food supply chain. It links UK ports, farms, food manufacturers, retailers, food service providers, and consumers. It is essential to the import and export of food. Food is primarily transported by sea, road and rail, and recent challenges related to the COVID-19 pandemic and the UK’s departure from the EU have made clear just how reliant the food supply chain is upon the transport sector.

The UK food supply chain is dependent upon just-in-time logistics systems, which allow the transportation of all food within short timeframes and as close as possible to when it is needed. For fruit, vegetables, and other items with a short shelf life, this allows food to be as fresh as possible and avoids food waste. These transportation systems are highly efficient, regular, and predictable, and allow consumers to have widespread access to food on supermarket shelves.

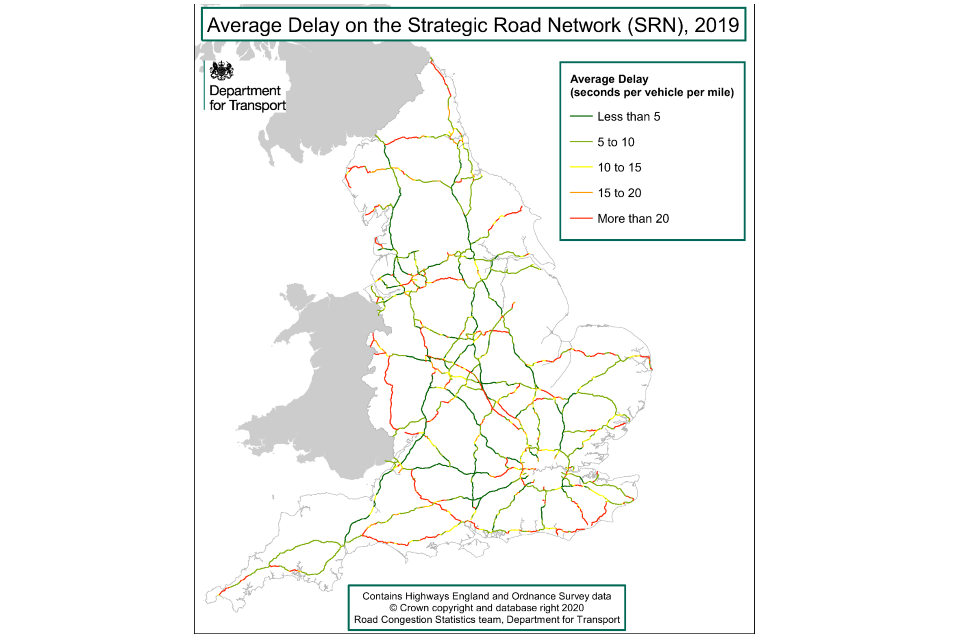

Just-in-time supply chains are sensitive to disruption to transport, particularly in road freight. Overall delay times on the Strategic Road Network, responsible for two thirds of all freight, have increased over the last five years.

Ports of entry to the UK are particularly important links in the just-in-time supply chain. As a nation the UK imports 46% of the food it consumes. Having a diverse range of international supply sources provides greater flexibility and makes food supply more resilient in the event of disruption. Equally, diversity in these access points provides flexibility and greater resilience in response to disruptions.

Around a quarter of the UK’s food imports pass through the Short Strait (Dover and the Channel Tunnel), and short-life products from the EU are highly reliant on these routes. 62% of fruit and vegetable imports from the EU arrive via the Short Strait, 43% of meats and 41% of dairy imports. Food and beverage imports are otherwise spread across a number of ports of entry, with no one port dominating.

Despite diversity of entry for the most part, UK ports are also subject to a variety of risks that may be geographically correlated, such as tidal surges on the East Coast. The impact of any disruption to ports would depend on the length and scale of the disruption, as well as the ability to find alternative points of entry in the timescales required. A further consideration is the dependency of the UK on the resilience and regulatory approach of ports, especially in the EU. For example, imports can be severely disrupted by border closures. Border issues may have different dynamics and affect freight differently. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the UK experienced two border closures, neither of which caused serious supply issues.

Labour and skills dependency

Throughout the supply chain, people are vital. In growing and harvesting, transporting goods, food manufacturing, and in retail of finished food products, the agri-food workforce employs 4.1 million people and represents 13% of Great Britain’s employment. The continuity of food supply is dependent upon securing sufficient labour with skills necessary to carry out specialised tasks.

The types of roles across the agri-food sector are vast. They include skilled and highly skilled roles – including, for example, engineers, butchers, supervisors, auditors, and veterinary nurses. The agri-food sector is also highly reliant upon roles classified as ‘low-skilled’. These roles are often labour intensive and common in the agriculture and hospitality sectors.

There are challenges securing sufficient labour across the agri-food chain. These challenges are both short-term and longer-term and interact with the wider challenges facing the UK economy, posing a threat to food supply resilience. They include dependency on agricultural seasonal workers and other skilled food chain labour from the EU along with the continued impact of COVID-19 on the workforce.

Food retail and wholesale

Diversity is essential to food security, not only in terms of trade in agri-food commodities, but also within the domestic supply chain which consists of retailers, food manufacturers, wholesalers, and food service operations. If one major supply chain or company were to fail, for example due to economic failure, cyber-attack, or power failure, there could be a significant impact on availability of, and access to, food, if other parts of the supply chain were not able to help to fill the gap.

The size and diversity of the UK food retail and wholesale sector provides economic resilience. The greatest risk is in the retail sector, where the five biggest retailers have 60% of market share between them. The size and diversity of the food supply chain allows flexibility when an agri-food business fails, however the COVID-19 pandemic has placed pressure on all parts of the food supply chain – especially in the wholesale sector. The closure of the hospitality sector due to COVID-19 and other lockdown impacts resulted in financial distress across significant parts of the wholesale market. However, despite these pressures the wholesale sector maintained financial viability and food supply was not compromised.

Consumer behaviour

The UK’s just-in-time food supply chain relies on balancing supply with consumers’ demand. Consumer behaviour can cause sudden demand shocks and impact the effectiveness of the food supply chain. Given the UK’s history of secure food supply, consumer shocks resulting from stockpiling are rare. However, during disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, industry proved effective in responding to increased demand, with government taking a supporting role. Consumer behaviour was characterised by a moderate increase in the amount of food purchased and in the number of shop visits made, rather than indiscriminate ‘panic buying’.

Cyber threats

The risk of cyber-attack to UK businesses is significant and continues to grow. It presents a threat to all CNI sectors. The nature of cyber-attacks means that they are varied and that attackers can adapt their approaches to their targets.

While the UK food supply chain has not been subject to significant attack, disruptions have been recorded in other areas of the globe with implications for their food security. Given the interconnectedness of the global food supply chain attacks elsewhere potentially also pose risks for UK food supply.

Indicator 3.1.1 Business resilience and response

Headline

The food supply chain is entirely owned and operated by private business, which is adaptable and flexible in responding to problems. Government monitors risks and works with industry to respond to emerging issues and maintain supply chains. A number of pressures in recent years, including the unprecedented stress of the COVID-19 pandemic, have threatened supply chains, but industry response, with government support, has succeeded in maintaining overall supply.

Context and Rationale

The threats which can impact the continuity of the UK food supply chain are diverse. The most significant risk of disruption lies in the agri-food sector’s reliance upon other critical sectors, for example energy and transport. Disruption experienced in one sector could put food supply chain continuity at risk. Given the wide range of potential shocks and disruptions that might occur within the agri-food chain – whether affecting energy, labour, data communications, raw materials (known as key inputs), or transport – government and industry need to be confident that adequate continuity and contingency planning is in place to mitigate against these risks.

The capability, levers, and expertise to respond to disruption lie with the agri-food industry, which is experienced in dealing with scenarios that can affect food supply disruption. Government’s role is to support and enable an industry-led response. This includes extensive and ongoing engagement to support industry in preparedness for, and response to, potential food supply chain disruptions.

Defra, other UK government departments, and the devolved administrations routinely identify, prepare, and respond to risks of national significance. This includes contributing to the National Security Risk Assessment, a classified and scientifically rigorous cross-government assessment of the most serious threats facing the UK and its interests overseas.[footnote 2] The National Risk Register (NRR) provides public information on the most significant risks that could occur in the next two years, and which could have a wide range of impacts on the UK.

The COVID-19 case study illustrates how the UK government, devolved administrations and industry collaborated effectively to mitigate against the risks of COVID-19. It also highlights the need for both industry and government to continue business continuity planning.

This indicator remains qualitative due to the commercial confidentiality of the agri-food sector.

Data and Assessment

The COVID-19 pandemic response demonstrated that the UK has a resilient food supply chain and a food industry which is good at responding to disruptions. Government actions, such as the temporary relaxation of UK Competition Law, supported industry in working collaboratively to minimise disruption, establish alternative supply routes and suppliers, and accommodate pressures in the supply chain.

The risks to the UK food supply chain from COVID-19 in 2020 were complex and unprecedented. The impacts were highly interrelated across the food supply chain and required a combination of mitigation measures to safeguard future continuity of supply. It is therefore difficult to identify the effectiveness of each individual mitigation measure, as it was the diversity of these actions which allowed product availability to steadily improve from late March 2020. It is clear that close collaboration between UK government, the devolved administrations and industry was critical to the effectiveness of the COVID-19 response.

Defra and the devolved administrations have continued to develop mitigations in response to evolving risks and issues associated with COVID-19. For example, in anticipation of border congestion in January 2021, government developed the Expedited Return Scheme (ERS) which allowed the prioritisation of empty food vehicles travelling from the UK to the EU through the Kent Traffic Management System. This allowed food vehicles to restock and return to the UK with fresh supplies. The ERS did not need to be activated and congestion issues were managed at the border.

In recent years the agri-food sector has experienced significant challenges not limited to COVID-19. This has included although is not limited to; the March 2021 disruptions to global supply chains in the Suez Canal; shortages of key inputs such as CO2; and labour and skill shortfalls in critical sectors. Although consumer choice may have been temporarily affected by these risks, the agri-food sector has ensured that there has not been an overall food shortage within the UK’s supply chain.

Case Study 3.1 COVID-19 response

Overview

The COVID-19 pandemic widely impacted the UK food supply chain. The government played a supportive role, utilising well-established ways of working with the food industry. This support enabled an industry-led response that met the demand placed on it.

Background

This case study reflects the UK’s response to COVID-19 across the agri-food sector at the start of the pandemic and the months that followed. Interventions differed in some ways across England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. COVID-19 and its impacts still present risks to the UK’s food supply despite the resilience of industry.

At the beginning of the crisis, early in 2020, risks to the UK’s food supply began to materialise. These included:

-

An upsurge in demand for certain products due to increased consumer purchasing. This represented a demand shock and led to temporary shortages of mainly non-food products, partly caused by a perception of potential shortages in the food supply chain.

-

Increased staff absences due to rates of COVID-19 and requirements to self-isolate.

-

Social distancing requirements meant businesses needed to adapt ways of working to maintain operability within their sectors, reducing capacity.

-

Financial difficulties in food sector businesses, particularly due to closures of some sectors, for example, in hospitality.

-

Minor international trade disruption and quotas leading to some temporary shortages of products.

-

Difficulties for those classified as ‘vulnerable’ (financially vulnerable/shielded/elderly) in accessing food throughout the lockdown stages.

Discussion

Defra worked closely and quickly with the food sector, other government departments, and the devolved administrations to understand key issues and develop interventions to ensure food supply to the UK population. A number of government measures were put in place to maintain food supply chain resilience.

Stakeholder Engagement

Stakeholder forums were used to maintain regular communication between industry, government departments and the devolved administrations. These included:

-

The Food Chain Emergency Liaison Group (FCELG): Defra’s long-established food industry sector working group for resilience and security issues. The group formally met regularly to identify and mitigate potential risks to food supply and interdependent sectors. The group also met in emergencies to act as a conduit between the food industry, UK government, and the devolved administrations. The FCELG has since been replaced by the Food Supply Resilience Planning Group, focusing on planning for medium- to longer- term risks to the food supply chain.

-

Food Resilience Industry Forum (FRIF): a bespoke forum which was established at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic to support the logistical and technical operations of food supply across the UK food supply chain.

-

Sector specific industry meetings aimed at providing effective communication between food sectors and government.

-

The Scottish Government’s Food Sector Resilience Group: specific to Scottish stakeholders, but similar to FCELG and FRIF, with regular ministerial involvement. A Scottish Public Sector Food Forum was also established.

Temporary measures introduced by industry

-

Communications to the public – government worked closely with retailers to develop and share messaging that aimed to help consumers understand the resilient nature of the supply chains and the impacts of their own actions.

-

Item limits on high demand goods (food and non-food) – to allow time for restocking of popular products.

-

Specific shopping slots allocated for vulnerable groups and key workers both online and in person – to ensure access to food.

-

Social distancing measures for public and staff – to safeguard individuals from COVID-19 infection.

-

Enhanced cleaning measures – to mitigate against the spreading of COVID-19.

Temporary measures introduced by government

Defra and wider government introduced a number of temporary mitigation measures:

-

Extended delivery and drivers’ hours – relaxing regulations on delivery times and driver regulations to allow a higher frequency of deliveries to and from stores.

-

Relaxation to UK Competition Law – two separate exclusion orders (the Competition Act 1998 (Groceries) (Public Policy Exclusion) Order 2020) allowed grocery retailers and their suppliers (directly or indirectly) to collaborate effectively to prepare for and, if required, respond to potential disruption only in the instance that it related to specified ‘qualifying activities’. This allowed more open discussion on areas such as stock levels, item limits, and store hours. A temporary relaxation to UK competition law was also made specifically for the dairy sector to allow further collaboration in the supply chain.

-

Relaxation of the plastic bag fee for minimum contact between deliveries and more time-efficient deliveries.

-

Labelling easements to allow for minor deviations on labels.

-

The Pick for Britain campaign and website - a collaboration with industry to ensure sufficient seasonal labour for domestic food production.

-

Food parcels for shielded groups - to ensure the clinically vulnerable had access to food during lockdown.

-

Government support for businesses experiencing increased costs and disrupted cash flow as a result of COVID-19. This included the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme, the Coronavirus Business Interruption Loan Schemes for small and large businesses (CBILS/CLBILS) and the Bounce Back Scheme for small and medium enterprises (SMEs)

-

The Trade Credit (TCI) Reinsurance Scheme which provided £10bn of guarantees on business-to-business transactions currently supported by TCI, backdated to April 2020 and running to 31 December 2020.

-

Legislation supporting information sharing agreements between industry and government. Defra included provisions in the Coronavirus Act (2020) which allowed government powers to obtain information from industry if necessary in a disruption. However, these provisions were not brought into effect due to the continued collaborative relationship between industry and government.

-

Adding essential food items to the Category 1 (CAT 1) goods list during COVID-19 response - to allow inclusion in mitigations where appropriate, such as prioritisation on commercial freight and access to hauliers.

Trends

The government will continue to review threats and risks as part of its responsibilities to food as a Critical National Infrastructure (CNI) sector. The risks exposed through the COVID-19 pandemic and transition planning for EU Exit have highlighted the significance of business continuity planning within industry and helped inform risk mitigation as part of their operations. Government intelligence suggests that broadly, industry continues to prioritise business continuity planning where possible. However, this is more likely to be possible for larger agri-food companies than for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

Indicator 3.1.2 Energy dependency in the food sector

Headline

The food supply chain is highly dependent upon the energy sector and vulnerable to both short-term supply disruption and medium-term energy price fluctuations. Demand for energy from the food and beverage sector has declined in the last 20 years, reflecting increased energy efficiency, but the sector remains reliant on imported natural gas. Demand has remained consistent for the agriculture sector for the past 20 years.

Context and rationale

The food supply chain depends directly and indirectly upon energy through its reliance upon common energy sources such as electricity, natural gas, and petroleum products. This dependency is evident across the supply chain, through production, processing, packaging, distribution, transport, retailing and consumption of food itself. Energy security is vital to the functioning of the whole economy. The food supply chain has high energy demands and is vulnerable to disruptions to energy supply or changes in energy prices. Capturing the energy intensity of the food supply chain is complex because it spans several sectors not all of which are purely food related. If the UK’s energy supply is not secure, the food supply chain will be vulnerable to disruptions.

Fluctuations in the energy market may affect the prices of commodities or key inputs such as carbon dioxide (CO2), and thus the economic viability of food businesses. Oil prices represent one of the most important drivers of change in global food commodity prices. Consumer prices also depend on wider factors including agri-food import prices, domestic agricultural prices, domestic labour and manufacturing costs, and Sterling exchange rates.

The UK meets its energy needs through production and trade. In 2020, total energy net import dependency was 28% of primary supply. This was 7.2 percentage points lower than 2019 and the lowest level since 2009, largely a result of lower demand during the COVID-19 pandemic.

For oil, import dependency varies by product. The UK is a net exporter of petrol meaning all demand could be met through indigenous production alone in the event of disruption. In 2020, the UK met close to 60 percent of road diesel demand through indigenous production. The UK imports diesel from a large number of sources which increases security of supply. The UK is self-sufficient in the production of gas oil (red diesel) which is commonly used by agricultural vehicles.

In recent years around half of natural gas demand was met through indigenous production, in 2020 this was 54%. The remainder is met through imports via pipelines and of liquefied natural gas (LNG). In 2020, a third of supply was met through imports from Norway. The UK has a large number of other import sources which increases security of supply.

A small proportion of UK electricity supply is provided by imports. In 2020, net imports accounted for 5.4% of supply. Whilst domestic generation capacity is sufficient to meet UK needs, interconnectors can provide additional flexibility and reduce costs. Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland have a single electricity market, by which electricity can flow freely across borders, balancing the market for the whole island of Ireland.

The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) is the lead UK Government Department for the risk of major power disruption. BEIS works closely with the Cabinet Office and other government departments to ensure that appropriate preparedness and mitigation measures are in place so that impacts from energy supply disruption are minimised.

This indicator includes data collected from BEIS through the Digest of UK Energy Statistics (DUKES) to illustrate energy demand in the food and drink manufacturing and agriculture sectors. A case study is provided on the major power disruption which took place on Friday 9 August 2019.

Data and assessment

Indicator: Aggregate energy demand for agriculture and food and drink manufacturing

Sources: DUKES

Figure 3.1.2a: Aggregate energy demand for agriculture and food and drink manufacturing.

Aggregate energy demand agriculture and food and drink manufacturing

In 2020, natural gas accounted for close to 60% of demand in the food and drink manufacturing sector, whilst electricity accounted for a third. Although minimal, demand for energy from bioenergy and waste has increased in recent years in line with substantial growth in renewable energy production. Continuing this trend in line with Net Zero targets may be challenging for manufacturing processes that use high temperature heat sources for which electricity is less effective than gas/petroleum products.

Figure 3.1.2b: Energy demand by energy type in the food and drink manufacturing sector.

Energy demand food and drink manufacturing energy type

Overall total demand for energy by the food and drink manufacturing sector has remained stable in the last 20 years. Natural gas meets 60% of energy needs followed by electricity at a third.

Figure 3.1.2c: Energy demand by energy type in the agriculture sector.

Energy demand agriculture energy type

Demand for energy in the agricultural sector shows an increase in 2016, which is somewhat explained by methodological updates. This includes apparent increased demand for petroleum products from 2015, in fact due to a change in method of estimating sector demand for oil products, and a peak in bioenergy and waste in 2013-14.[footnote 3] To note, further revisions and back casting were delayed due to COVID-19 and will likely be published in 2022.

Petroleum products play an important role in the agricultural sector, meeting more than 60% of energy needs. Within the DUKES balance this largely consists of burning oil, used for drying of crops and heating, and gas oil (commonly known as red diesel) used to power non-road machinery (NRMM). In addition, a small amount of propane is used, mainly for heating (most commonly on poultry farms). Indirect agricultural demand for energy inputs such as fertiliser are not captured within this sector of the balance, but in demand for energy by the chemical industry.

The drop off in demand for coal is in line with reducing coal demand across the board.

Trends

In absolute terms, energy used in food and drink manufacturing has generally been declining over the last 20 years (more significantly on a per capita basis), reflecting increased energy efficiency. For agriculture, energy use has been more stable, with a slight upward trend between 2016 and 2020. Energy use in agriculture is also likely to be impacted by other inputs such as fertiliser, which is not reflected here.

Case Study 3.2 9 August 2019 Power Outage: Food Sector Impact

Overview

On Friday 9 August 2019, over 1 million customers were affected by a major power disruption that occurred across England, Wales, and some parts of Scotland. Though the power disconnection itself was relatively short lived - as all customers were restored - the knock-on impacts to other services were significant. This event demonstrated the need for essential service providers, including those in the food sector, to have robust business continuity plans in place for disruptive events such as power outages.

Background

The 9 August power disruption was triggered by a lightning strike to an overhead transmission line and the near simultaneous loss of a number of generators. The loss of generation caused an imbalance between the amount of electricity being generated and the amount of electricity being used by businesses and the public. This triggered an automatic protection system (known as Low Frequency Demand Disconnection) which had the effect of disconnecting over 1 million customers to address the imbalance and protect the electricity network from a total shut down.

Although all customers were restored within 45 minutes, a number of sites and services were impacted including:

-

Rail – 371 cancelled services, 220 part cancelled services and 870 delayed trains; some signalling assets were also affected. Major delays extended into Sunday 11 August.

-

Hospitals – 4 hospitals automatically switched to their back-up generators.

-

Water Treatment – 3,000 customers experienced a reduction in water pressure and 1 water treatment plant needed to switch to its back-up generator.

-

Airports – 2 airports automatically switched to their back-up generators.

Discussion

The majority of these services were not disconnected by the Low Frequency Demand Disconnection Scheme. Instead, the service disruptions were caused by protection systems under the control of individual essential service operators, which reacted to the disturbance on the electricity network.

A number of investigations were carried out by the impacted industries to better understand why internal safety systems reacted to the frequency and voltage fluctuations in the way that they did and whether any mitigations are available. For example, the rail industry took proactive steps to assess why some trains stopped operating when the frequency on the power network dropped. Several engineering and incident response solutions were introduced to ensure resilience to future potential power disruptions. These are set out in the Office of Rail and Road’s report on the rail disruption.[footnote 4]

Impacts were further exacerbated by the ineffectiveness of essential services’ business continuity plans. Guidance developed by the Energy Emergency Executive Committee (E3C) was developed and cascaded to operators of essential services to ensure their preparedness and resilience to a range of possible power disruption scenarios. The E3C includes industry, regulators, UK government and devolved administrations who work together to build resilience in energy supplies.

Whilst the power outage did not have a large impact on the food sector - no disruptions were reported across the food production, distribution or sale - this event illustrates the importance of adequate preparation and planning for power disruptions, to minimise any disruption to customers and the public.

Indicator 3.1.3 Transport dependency in the UK

Headline

The functioning of the food supply chain depends on an efficient transport network, especially the road network. Just in time supply chains are sensitive to disruption to transport, particularly in road freight. Overall delay times on the Strategic Road Network, responsible for two thirds of all freight, have increased over the last five years.

Context and rationale

The transport sector plays a strategic role in connecting the UK food supply chain. It links UK ports, farms, factories, retailers, food service providers, and consumers. It is essential to the import and export of food. Food is primarily transported by sea, road and rail. Food products were the most common commodity imported by UK-registered heavy goods vehicles in 2020, with 1.2 million tonnes imported, accounting for 35% of all imports.[footnote 5],[footnote 6]

The UK food supply chain is dependent upon the use of ‘just-in-time’ logistics, which allow the transportation of food within short timeframes and as close as possible to when it is needed. For fruit, vegetables and other items with a short shelf life, this allows food to be as fresh as possible and avoids food waste. These transportation systems are highly efficient, regular, and predictable, and allow consumers to have widespread access to food on supermarket shelves. Food security disruption could however occur if the continuity of the transportation system was compromised. The reasons for transport disruption could include, for example, border delays, extreme weather events, flooding or any other accidental or malicious disruption affecting multiple points of the transportation network. As a result of the just-in-time approach, retailers do not usually hold substantial stock on-site, meaning that the supply chain is sensitive to sudden increases in demand and disruption is likely to be felt relatively quickly. However, on such occasions, the UK is unlikely to experience an overall shortage of food, though some products may experience temporary disruptions. On such occasions products in short supply may be able to be sourced from alternative suppliers.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the challenges related to EU Exit have illustrated how reliant the food supply chain is upon the transport sector. During the pandemic, despite shocks to the food system, food supply was maintained with only temporary disruptions. Although there are ongoing recruitment and retention challenges of Heavy Goods Vehicle (HGV) drivers which has caused significant challenges within the transport sector. Certain areas of the UK, in particular remote and island communities, are more vulnerable to disruption occurring in the transport system due to the length and complexity of their supply lines. EU Exit has also created new challenges for supply of food to Northern Ireland, which has in general a more complex supply chain due to the greater distances and ferry connections needed to ship goods from Great Britain.

As all food is transported at least part of the way via road, this indicator looks at the Road Congestion and Travel Time Statistics collected by the Department for Transport (DFT) which cover the Strategic Road Network (SRN) in England. The SRN is the most heavily used part of the national road network covering motorways and major A roads, and carries a third of all traffic and two-thirds of all freight. Delay indicators are only available for the SRN in England. However, as a high proportion of food to all parts of the UK travels through England, this indicator is relevant to the food supply of the entire UK.

Data and Assessment

Indicator: Road Congestion and Travel Time Statistics

Sources: Strategic Road Network

Figure 3.1.3a: Average speed on the Strategic Road Network (SRN).

Average speed Strategic Road Network

This indicator only includes data up to the end of 2019 as from March 2020 the average speed increased due to there being fewer vehicles on the road during the first COVID-19 lockdown. The DFT has published a report on the impact of the pandemic on travel time measures, including estimates of what average speeds would have been in 2020 without coronavirus impacts.[footnote 7]

The average monthly speed on the Strategic Road Network in England varied between 57 and 61 miles per hour from 2015 to 2019. Each year the month with the slowest average speed is November, while April often has the highest. There is seasonality within the congestion data, with higher speeds experienced around April and slower speeds in November, after the clocks change. This change causes a slight increase to average delays which might be due to darker mornings causing people to get up later, therefore increasing the number of people using the roads during peak times. In April, when the clocks go forward, the average delay is slightly lower, which could be attributed to people getting up earlier with the lighter mornings, decreasing the number of vehicles on the roads during peak times. This seasonality is generally incorporated into planning by hauliers and other logistics businesses.

Figure 3.1.3b: Average delay on the Strategic Road Network (SRN) in England, 2019.

Strategic Road Network delay

The average delay on individual main carriageway links was less than 10 seconds across England in 2019. Around major cities, the delay was approximately 20 seconds per vehicle per mile (spvpm). This could be due to the high demand on the network around them, relative to their capacity. The roads with the greatest year-on-year increases in delay also tended to have the greatest decreases in average speed. These were primarily in areas with ongoing roadworks, implemented as part of the Road Investment Strategy (RIS).

Figure 3.1.3c: Average delay on the Strategic Road Network (SRN).

Strategic Road Network average delay

For 2019, the average delay on the SRN was estimated to be 9.5 seconds per vehicle per mile (spvpm) compared to speed limits. This is 0.9% higher compared to 2018, which means on average there were more delays in 2019 than 2018. 2019 is used as a reference year because the travel restrictions under COVID-19 in 2020 affected traffic flow in a way that was atypical.

Since 2016, there has been a gradual increase in the average delay on the SRN in England, although the number of vehicles travelling on it over that time has increased at a greater rate.

Average speeds on the SRN have decreased slightly by 0.5 miles per hour (1% decrease) since 2016, while in the same period average delays have increased by 0.5 spvpm (5% increase).

Overall, continuity of the SRN system is expected to be maintained. There has been a slight worsening in average delay times which can be explained by the decrease in average speeds due to roadworks. However, in the past 5 years there have been no significant disruptions to just-in-time supply chains, suggesting high food security for food already within the UK.

Trends

In absolute terms there has been a slight increase in average delay times on the SRN, although this is not significant. It will be important to monitor any changes resulting from structural breaks caused by COVID-19 and the UK’s exit from the EU. Longitudinal evaluation of the SRN will be needed to determine its resilience.

The road freight sector has been impacted by a reduction in the number of drivers. An estimated 268,000 people were employed as HGV drivers between July 2020 and June 2021. This is 39,000 fewer than the year ending June 2019, and 53,000 fewer than the peak of 321,000 HGV drivers during the year ending June 2017.[footnote 8] The UK government is taking action to address this shortage.[footnote 9] This includes attracting drivers back to the industry by investing £32.5 million to improve facilities across the country, to investing £17 million to create new HGV Skills Bootcamps to train up to 5,000 more people to become HGV drivers in England.

Indicator 3.1.4 Points of entry in the UK

Headline

Food imports from the EU, particularly short shelf-life goods, are concentrated on the Short Strait (Dover and the Channel Tunnel). The risks of this concentration are discussed in Indicator 3.1.5. Imports are otherwise spread across a number of ports of entry, with no one port dominating non-EU imports.

Context and Rationale

The UK’s points of entry are the places where goods enter the country from abroad. Food from overseas, as well as animal feed and fertiliser inputs for domestic agriculture, enter the country through these international gateways. The following analysis focuses mainly on UK seaports, which are the most important of those gateways. The Channel Tunnel and airports (particularly Heathrow) handle the remainder of the UK’s food imports, around 15% of the total.

Understanding the spread of imports across the UK’s ports helps to identify key infrastructures such as port facilities, roads and railways which connect those ports to the food supply chain. Food security could be compromised where risks are not spread between a sufficient number of ports, or where there is a lack of flexibility to switch between suitable ports, should the need arise.

UK ports are also subject to a variety of risks that may be geographically correlated, such as tidal surges on the East Coast. The impact of any disruption to ports would depend on the length and scale of the disruption, as well as the ability to find alternative points of entry in the timescales required.

A further consideration is the dependency of the UK on the resilience and regulatory approach of ports in the EU from which the bulk of UK imports depart. This varies between countries like France, Spain, and the Netherlands, and affects the ease with which goods flow to the UK.

Data and Assessment

Indicator: Percentage share of UK food imports by port and mode of transport

Source: A report by Baker P, PRB associates (2020), commissioned by Defra

Figure 3.1.4a: Percentage share of UK food imports by port (EU countries, 2018).

Percentage share UK food imports by port EU

The graph above shows the main ports used for UK food imports from the EU in 2018. The top six ports responsible for EU imports account for 58% of total shipments. The port of Dover represents the biggest source of EU food imports, at 22% of the total. In 2018, the UK imported 28 million tonnes of food products from the EU.

Figure 3.1.4b: Percentage share of UK food imports by port (non-EU countries, 2018).

Percentage share UK food imports by port non EU

Non-EU imports are more concentrated within the top 6 ports. The graph above shows that the top 6 ports account for 72% of non-EU imports, with Liverpool the biggest source of shipments, at 18%. In 2018, a total of 11.3 million tonnes of food products were imported from non-EU countries.

Figure 3.1.4c: Percentage share of UK food imports by mode of transport (EU countries, 2018)

Percentage share UK food imports by mode of transport EU

Although equivalent data is not available for non-EU countries, the graph above demonstrates the split of UK imports from EU countries by mode of transport. Accompanied ‘roll on roll off’ (RoRo) accounts for just over half of EU imports, at 52% of the total. This is when freight is carried in trailers attached to a road goods vehicle, on sea-going vessels fitted with ramps for discharging without the use of cranes. The next most significant is Bulk Good Transport, accounting for 23% of the total and involving the import of agricultural commodities, such as sugar and grain. Unaccompanied RoRo (freight carried on unattached trailer) and container ‘load on load off’ (LoLo) (cargo carried in 20-foot and 40-foot containers) account for the remaining quarter of food imports from the EU between them.

In aggregate, both EU and non-EU food imports, via all modes of transport, are well spread across a number of ports of entry, with no port having a dominant share. Only simultaneous disruption to several ports would be serious enough to have an overall effect on UK food supply.

There are clusters of ports used for handling food import traffic, for instance in the South East and North East regions. Their geographical proximity suggests that they could share some risks of disruption from extreme events such as coastal flooding. A tidal surge on the east coast could have a concurrent impact across multiple key ports in the UK and on the European mainland. Government, ports, and many businesses have plans to reroute goods to other ports in this event, but the combined effect of rerouting all east coast traffic would likely cause delays and congestion at other ports.[footnote 10] The just-in-time nature of the supply chain makes it vulnerable to this kind of disruption, with the greatest impact on availability of fresh produce.

However, the resilience of port infrastructure is not solely a matter of having a range of ports to potentially divert to. Alternative ports must have the correct protocols, staffing capacity and suitable infrastructure to receive food imports and different cargo types. A port’s capacity and configuration govern both the types and sizes of sea-going vessels that can be received, and therefore the types and quantity of food cargo that can be discharged there. Currently, there is a data gap at both the individual port and UK level, to allow for an accurate assessment of the ease with which food import traffic can be switched between ports in the event of disruption. This is an area which could be considered for future Food Security Reports.

Trends

There has not been a significant change in the diversification of EU and non-EU food imports in recent years. It will be important to monitor any changes resulting from the UK’s exit from the EU, or any new developments in port capacity, such as the planned Poole-Tangier route.

Indicator 3.1.5 Food imports via Short Strait

Headlines

There is a degree of reliance on the Short Strait import routes for some food products, especially perishable goods such as fresh fruit and vegetables. In the event of disruption to the Short Strait, it is expected that the use of alternative points of entry could decrease the impact to food supply.

Context & Rationale

The Short Strait routes refer to the ferry connections between the port of Dover and Calais and Dunkirk, and the Channel Tunnel railway connection between Folkestone and Calais. The Short Strait routes are the shortest routes from Dover to continental Europe, and offer advantages in time, cost, and frequency of services. The short journey times are particularly important for the transport of goods with a short shelf life, such as fresh fruit and vegetables.

Given the perishability of many food products and the just-in-time basis of the food supply chain, food importers have increasingly used these routes through shipping in accompanied trailers. An over-reliance on the Short Strait routes could mean that an issue with one or both of them could significantly disrupt the supply of some imported food products.

It is estimated that 36% (10 million tonnes) of food imports from the EU arrived via the Short Strait in 2018, which equates to around 25% of total UK food imports. Given that around half of the food consumed in the UK is imported, it can be estimated that around 12.5% of food consumed in the UK is being imported via the Short Strait.

Data and Assessment

Indicator – Breakdown of the Short Strait food imports from the EU

Source: - The source of all the data in this section is a report by Baker P, PRB associates (2020), commissioned by Defra

Figure 3.1.5a: Percentage breakdown of the Short Strait food imports from the EU

Breakdown Short Straits food imports EU percentage

Figure 3.1.5b: Breakdown (in tonnes) of the Short Strait food imports from the EU.

Breakdown Short Straits food imports EU tonnes

The graph above presents volumes data on the breakdown of food imports from the EU and their corresponding shares of total food imports from the EU in 2018. The UK is reliant on the Short Strait for certain food groups, in particular: fruit and vegetables (62% of fruit and vegetables imported from the EU arrive via the Short Strait), meats (43%) and dairy (41%). Of the total EU food products imported via the Short Strait, it is estimated that 44% are fruit and vegetables, 19% are beverages, 9% are meats, and 9% are dairy.

In addition, there are 0.3 million tonnes of non-EU food imports that arrive via the port of Dover. Of those imports, 98% are “Edible fruit and nuts; peel of citrus fruits or melons.”

There is some reliance on Short Strait routes for food imports of certain products, there is potential for these imports to be redirected to other ports on the south and east coasts of England in the event of disruption at Dover and the Channel Tunnel.

Examples of ports that may be suitable for this substitution include Harwich, Portsmouth, Immingham, Hull, and Killingholme. The ability of these ports to take on additional shipments at potentially short notice will be determined by factors including:

-

current utilisation levels

-

competing demand for spare capacity from other sectors

-

having the relevant infrastructure

-

trained inspection staff in place to accommodate increased traffic flows

-

the ability of industry to reconfigure their supply chains.

Finding extra capacity could present significant challenges given the volumes involved. In an ordinary week, around 36,000 trailers use the Short Strait crossings, compared to 20,000 trailers on the North Sea and Western Channel routes, all of which are much longer sailings. The port of Dover handled 1.07 million imports of road goods vehicles in 2020, while Harwich, Portsmouth, Immingham, Hull and Killingholme handled 220,000 combined.

Trends

There has not been a significant change in the level of reliance on the Short Strait routes in recent years, but the UK’s exit from the EU could affect this in the future.

Indicator 3.1.6 Border closures

Headlines

Border closures intended to control disease have the potential to threaten food imports. Border issues may have different dynamics and affect freight differently. The below case studies draw on two border closures experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic; one imposed on the UK by France, and the other imposed by the UK on Southern Africa and South America, neither of which caused serious supply issues.

Context & Rationale

Border closures are the decision taken by a country to close its borders to people or goods entering from elsewhere. Border closures limiting the travel of people were used by the UK and other nations during the COVID-19 pandemic to limit the spread of the virus.

Border closures pose a risk to the food supply chain as the UK imports around 45% of the food it consumes. Consequently, border closures can cause temporary disruptions to the supply of certain food items, particularly fresh products from the EU as these often arrive via road accompanied by a driver. Freight which arrives unaccompanied is less susceptible to the impact of a border closure that prevents hauliers from entering the UK. This is because no single person is accompanying the food between countries. The container with the food inside is loaded onto a ship and then collected by another driver at the destination port.

Although disruption to certain foodstuffs may occur, border closures are unlikely to be a threat to overall food security as the UK’s food supply is diverse. In addition, accurate data, real-time intelligence sharing, and cross-government collaboration bolster the capacity of both government and industry to respond to border closures. However, delays to shipments of fresh food can lead to shortages on shelves due to the just-in-time supply chain, and economic losses through spoilage. This section will include two case studies on the French-imposed border closure in December 2020, and the UK imposed border closures for Southern Africa and South American countries in January 2021.

Case Study 3.3 French Border Closure, December 2020

Overview

In December 2020, France closed its border with the UK as a consequence of the Alpha variant of COVID-19 circulating amongst the UK population. France banned the entry of people, including accompanied freight (both sea and air), from the UK at 23:00 Sunday, 20 December for 48 hours.

Travel bans were also imposed on the UK by other countries, including the Netherlands, Belgium, and Italy, though these restrictions did not include accompanied freight.

Background

The border closure was a threat to the UK’s food supply due to the volume of food imports that come from or through France to the UK, and because of the lack of warning, which gave the UK little time to respond.

The UK imports many food items directly from France, such as 13.4% of cheese imports, 32.4% of yoghurt imports, 27.6% of apple imports, and 19.4% of bread, crispbread, and savoury imports. France accounts for 9.1% of the UK’s total food imports.

The France - UK route is also important for food imports from other EU nations. Many of these imports arrive accompanied, so the total ban on both people and accompanied freight posed a significant threat to the UK food supply.

This manifested in two ways. Firstly, hauliers transporting food were unable to travel to the UK from France. Secondly, hauliers were stuck in the UK and unable to return to mainland Europe to pick up more food.

Discussion

Despite the potential threat, no serious disruption to the supply of food into the UK occurred. The interruption was relatively short-lived, with the ban on accompanied freight lasting only 48 hours. Many businesses had sufficient stockpiles to mitigate this disruption to supply for this period.

French officials ended the restrictions after the UK government set up prioritised COVID-19 testing sites for hauliers, who could then return to France if they tested negative. Although the UK has a significant dependence on France-to-UK shipping lanes for its food imports, there are a number of other important routes such as from Rotterdam in the Netherlands, as well as domestic production.

The availability of data regarding UK imports of food and other key inputs in the food supply chain was significant in this situation. The government always had the evidence required to make informed decisions about the next steps. The availability of communicable and up-to-date trade data is crucial in combatting such instances of disruption.

Case Study 3.4 UK-Imposed Border Closures (southern Africa; South America), January 2021

Overview

In January 2021, the UK government imposed border closures due to the presence of COVID-19 variants in several countries. The first border closure was with South Africa in early January. It prevented aircraft travelling directly from South Africa to England, as well as a ban on entry for travellers who had been in or transited through South Africa in the previous 10 days. Equivalent restrictions were imposed on all southern African countries.

In mid-January a second border closure of the same nature was imposed, this time with Brazil and other South American countries.

Background

These border closures mirrored the French border closure in that only unaccompanied freight was permitted into the UK. As this travel ban impacted included over 20 countries, it posed a significant threat to food supply.

Discussion

Although direct flights were prevented from arriving in the UK, the arrival of unaccompanied ships continued. Many of the food items imported from southern Africa and South America such as bananas and grapes travel unaccompanied on ships, so the travel bans did not disrupt their supply.

The risk to food supply was further reduced because food imports from both regions remain relatively low in comparison to Europe. The three biggest suppliers, Brazil, South Africa, and Argentina, only account for 1.7%, 1.6% and 1.5% of the UK’s total food imports respectively.

Combining Defra’s trade data with an understanding of how food imports are transported, the government was able to impose travel bans without impacting the UK’s food supply. It is crucial that the government continues to gather up-to-date data in this area so that difficult decisions can be made efficiently and confidently.

Foreign-imposed border closures do not occur in a vacuum. Vulnerabilities that might normally be of minimal concern can be amplified in the context of a major incident. The French border closure occurred concurrently with two producers of a critical ingredient closing their UK production sites. In this instance, the supply of that ingredient was not severely disrupted but it is vital that the government tracks all such threats to the UK’s food supply, through live monitoring of issues as well as engaging with various stakeholders.

The UK imposed border closure was not inconsequential, but the impact on food supply was small, and the impact on food security was virtually non-existent.

Trends

The UK has experienced an increased number of border closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Whilst it is difficult to predict future incidents of border closures, the food supply chain has illustrated its resilience in responding to such disruptions.

Indicator 3.1.7 Key inputs to the food supply chain resilience

Headline

Certain goods are critical to the functioning of the food supply chain. Although the supply of these goods is industry led, government monitors the supply of these key inputs and supports industry in developing plans and mitigations to ensure continuity of supply. Where necessary, government is able to make targeted interventions to maintain supplies.

Context & Rationale

Key inputs are those chemicals, ingredients and additives used in the production, supply, and storage of essential food items. Essential food items are products that are recommended for a nutritionally balanced diet in line with the Eatwell Guide (for example cheese, fresh meat, bread).[footnote 11]

Key inputs include all inputs from farm to fork, with products as diverse as fertilisers and chilled meats. In manufacturing, sodium hydroxide (NaOH) is a key input as it is a cleaning agent necessary for the safe and hygienic manufacturing of food. Other examples of key inputs include ammonium nitrate (fertiliser), ethylene glycol (refrigerant), wheat flour (ingredient), tinplate (packaging), potable water, and fresh fruit and vegetables (ingredient).

Key inputs in the food supply chain are diverse and interface with an array of different markets. The same input could have a myriad of uses within the industry and therefore be vulnerable to several shocks in the system. An example of this is carbon dioxide (CO2) which is produced, in one instance, as a by-product of ammonium nitrate and used in the meat and drinks manufacturing and packaging industries.

Therefore, contingency planning is essential to ensure that industry and the government are prepared to respond to different shocks to the system. In general, key inputs are resilient to the most common disruptions.

The significance of key inputs to the food supply chain was highlighted during the summer of 2018 when there was a shortage of CO2. This incident revealed that for the government to have a comprehensive understanding of the food supply chain, it was crucial to map hidden inputs like CO2. Since then, government has gained foresight into the vulnerabilities in the supply of key inputs. Yet the 2021 shortage of CO2 has demonstrated that disruptions to key inputs are still a genuine possibility.

The causes of disruption to key inputs are diverse. They include border or transport disruption, company closures, shortages of HGV drivers or shortages of products required to produce the key input.

A ‘perfect storm’ of incidents like this can seriously disrupt the supply of key inputs, so it is important that government maps and monitors them. The initial work undertaken following the CO2 shortages in 2018, coupled with the work done when the UK left the EU, ensured that the government was in a good position to understand the potential vulnerabilities in the supply of key inputs into the food supply chain during the first wave of COVID-19.

Data and Assessment

The government plays an active role in engaging with the agri-food sector to develop industry-led mitigations. This includes providing advice on substitution and seeking alternative supplier routes to mitigate against shortages of key inputs. If disruption did occur, depending on the severity, and where industry mitigations were not possible (e.g., alternative supplier, substitution, reasonable production adjustment), the government would consider appropriate levers on a case-by-case basis and work with the relevant departments to alleviate the impact. This could include regulatory easements, laying legislation to relax food production or labelling regulations, competition law exclusions or prioritising critical products in freight transport into the UK.

An example of these mitigations is Government Secured Freight Capacity (GSFC), a legacy mitigation that was put in place to reduce disruption in a no-deal scenario to ensure a smooth movement of key input goods (known as Category 1 or CAT1 goods) into the UK through reserved freight capacity.

Within Defra, some industries produce certain CAT1 goods. This includes the food sector which is dependent on key inputs such as raw materials, refrigerants and additives (for example thiamine used in flour fortification). This intervention was used to support the flow of key inputs into the food supply chain. On the date it was stood down in June 2021, GSFC had never been used during the period of live monitoring of disruption to key inputs into the food chain. This is a reflection of the work done by Defra to anticipate a possible disruption in January 2021. Additionally, Defra’s role within the Capacity Management Centre (CMC) – the operation centre that ran GSFC – was highly successful in managing and resolving any potential issues without needing further progress into GSFC.

The government, and in particular Defra, conducts research into key inputs into the food supply chain and actively monitors their supply. Intelligence on supply of key inputs is shared across government departments (for example BEIS and the Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC)) and with industry, especially during instances of increased potential for disruption. This collaboration is vital for ensuring government has a clear view of threats to the food supply chain.

Collaboration was particularly important in the context of EU Exit and the COVID-19 pandemic, which had the potential to place stress on the supply of key inputs as a result of consumer-driven demand shocks, border closures, absenteeism, and delays at ports. In addition, regular horizon scanning for signals of change which might impact the supply of key inputs in the medium-term and long-term is undertaken by government.

Figure 3.1.7a: How Defra monitors the supply of key inputs into the food chain

Defra monitoring supply of key inputs

The aim of research into key inputs is two-pronged. Firstly, the research helps government understand the importance of any particular key input to the food supply chain. Secondly, it identifies vulnerabilities in the supply chain of each key input. The research is centred on five broad characteristics:

-

Supplier – including major supplying companies; major supplying countries.

-

Transport – including lorry type; ship type; accompanied vs. unaccompanied; driver qualifications required.

-

Supply Chain – including supply chain type; points of entry.

-

Production –including process automation; dependence on migrant labour.

-

Food Technology – including importance for essential food items; shelf life; stockpiles; substitutability.

The government also considers cross-sectoral demand for key inputs to aid prioritisation, as well as environmental questions such as the sustainability of their production.

Overall, such work continues to provide insight into food chain key inputs to understand their importance to the food supply chain and the vulnerabilities which might exist in their supply. This has afforded government a clearer, more detailed understanding of the food supply chain and has strengthened the capacity of Defra to plan for, and ultimately mitigate, potential threats to the UK’s food supply. The response to the carbon dioxide shortage illustrated government’s role in coordinating an industry response to a short-term supply issue.

The government’s work in preparation for leaving the EU and during COVID-19 has helped to increase knowledge of the supply of key inputs into the food supply chain. Within this, government has developed clear mitigations aimed at supporting industry should there be disruption to a key input.

Case Study 3.5 Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Shortage 2018

Overview

In June 2018 the agri-food sector experienced a shortage of carbon dioxide (CO2) due to several concurrent factors.

Background

Carbon dioxide is used extensively in the food supply chain, including in supply, storage, as a stunning gas in slaughterhouses, in the packaging of perishable foods, the carbonation of soft and alcoholic beverages, the refrigeration of food, and the refining of sugar.

The factors contributing to the shortage of carbon dioxide included:

-

CO2 is a by-product of ammonium nitrate fertiliser production, so low fertiliser prices across Europe affected the commercial viability of CO2 production.

-

Several UK and EU manufacturers capitalised on the opportunity to shut plants for maintenance works.

-

This coincided with high summer temperatures which created problems at some plants, made liquefying CO2 more difficult, and led to unforeseen failures in restarting plants.

-

High temperatures and the 2018 FIFA World Cup also raised demand for carbonated beverages. With low CO2 stocks, tight supply in continental Europe, and restrictions on sources of supply, many UK suppliers and manufacturers defaulted on contracts to supply CO2.

The response was led by industry and supported by the UK government.

Discussion

The Food Chain Emergency Liaison Group (FCELG) was used as a forum for obtaining a detailed view of the UK and European situation, exploring industry use of carbon dioxide and its alternatives, as well as for industry-supplier discussions. Government maintained awareness of emerging concerns and issues for the food and farming sectors, and concerns about their CO2 stock levels. Through established industry liaison, government understood that industry was assessing the viability of electric stunning and exploring alternatives to CO2 in packaging.

The pig and poultry sectors were identified as particularly vulnerable to interrupted CO2 supply due to its use for stunning before slaughter. The Food Standards Agency (FSA) worked to establish practical steps to keep abattoirs running.

Measures were quickly implemented such as the authorisation by the FSA of electric stun facilities and the use of CO2 alternatives at key sites. Staff working hours at plants were extended where required and a risk assessment was issued to businesses with technical advice on CO2 and gas substitutes for packaging.

Defra also shared intelligence with key government departments, including BEIS and the Cabinet Office (CO), in order to maintain an overview of the UK’s available CO2 supply.

Although some product lines were impacted by the shortages, the government’s close relationship with industry, alongside collaborative intel sharing across government, ensured that no serious food supply issues occurred.

The incident brought to light the vulnerabilities in the supply of CO2. This encouraged industry to put in place mitigations, such as increased storage capacity, and also motivated government to conduct research into the supply chain of CO2, and subsequently many other key inputs into the food chain.

Trends

There is a risk of disruption and government will continue to monitor the key inputs into the food supply chain and, where required, work with industry in cases of disruption.

Indicator 3.1.8 Consumer behaviour

Headline

Consumer behaviour can cause sudden demand shocks. During recent disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, industry proved effective in responding to increased demand, with government taking a supporting role. Consumer behaviour was characterised by a moderate increase in the amount of food purchased and in the number of shop visits made, rather than indiscriminate ‘panic buying’. Consumer behaviour was characterised by a moderate increase in the amount of food purchased and in the number of shop visits made, rather than indiscriminate ‘panic buying’.

Context and rationale

Consumer purchasing behaviours are the actions taken by consumers to purchase food, drink, and groceries. Consumer purchasing behaviours are complex and widely studied.[footnote 12] Most purchasing decisions are habitual and are reliant on unconscious biases, rules of thumb, and social and cultural norms. A range of factors can shape what consumers choose to buy, and how often, such as:

-

shopping priorities such as price or convenience

-

personal and household taste/preferences

-

advertisement and marketing

-

availability

-

public messaging

-

food concerns such as safety issues

-

values such as concern for animal welfare or sustainability

Stockpiling

The decision to stockpile food is an adaptation made by consumers when there is an anticipation that there will be disruption in food supply, a food shortage, or price increases. If this is perceived to be a likely event, then these may be rational behaviours for the individual, especially for consumers concerned with affordability or people with limited access to food shops.

In response to perceived risk to supply consumers can exhibit a range of stockpiling purchasing behaviours. These can range from considered purchasing, whereby consumers add a little more to their baskets, through to bulk buying, where consumers buy significantly more than they would of one item or more in either one or multiple trips, to more extreme behaviours such as looting. These can range from considered purchasing, whereby consumers add a little more to their baskets, through to bulk buying, where consumers buy significantly more than they would usually, to more extreme behaviours such as looting.

For the purposes of this report, stockpiling behaviour is defined as when individuals build up a reserve stock of goods over a period of time to mitigate against the loss of not having that product at a later date.

An individual’s assessment of whether a risk to food supply is credible is based on the information available to them. This information can take many forms, such as an official government response, media or news content, and also public discourse (such as social media discussion) and the behaviour of others. Depending on the perceived severity of the risk, consumer adaptation strategies sit on a spectrum from normal purchasing behaviour through to stockpiling, then to the more extreme behaviours of panic buying and looting.

Having (access to) more information does not necessarily always lead to a return of normal shopping behaviours. Any additional information, particularly sensationalist coverage on traditional and social media, can risk increasing the visibility of the issue, making it more plausible, thus creating an increased perception of risk and feeding into the overall stockpiling cycle.

Industry is effective in responding to fluctuations in demand including planned (such as Christmas and Easter) and unplanned events (for example, people stockpiling bread and milk during bad weather events). More severe shortages due to sustained consumer demand shocks or ‘buying’ may require additional interventions by industry, such as item purchasing limits, with government playing a supportive role. More severe shortages, due to sustained consumer demand shocks or ‘panic buying’, may require additional interventions by industry, such as item purchasing limits, with government playing a supportive role.

Demand spikes can exacerbate shortages of products and increase the pressure on supply chains, making it more challenging to manage stock through supply. Changes in consumer behaviour can cause potential impacts such as product shortages. Even incremental shifts in food purchasing behaviours at the population level can have significant impacts on just-in-time supply chains.

Data and Assessment

Behaviours driving purchasing spikes in a crisis are often reported in the media as irrational responses to perceived supply disruption. However, evidence suggests that the majority of consumer behaviour observed during March and April 2020 was not indiscriminate ‘panic buying’ to bulk buy goods, but a more moderate increase in purchasing in response to perceived supply uncertainty.

The cumulative effect of these small changes in shopping behaviours can play a significant role in disrupting just-in-time supply chains which are finely tuned to ‘normal’ consumer purchasing patterns. This disruption led to availability and supply issues which presented as empty shelves or reduced product range in shops. This was picked up by conventional and social media. Headlines about empty shelves further exacerbated consumer uncertainty and fed into the perception of shortages, which likely led to consumers continuing to purchase more than they normally would. There is a risk of headlines creating a real demand issue from a perceived one.