Detailed analysis of fires attended by fire and rescue services, England, April 2019 to March 2020

Updated 19 October 2020

Applies to England

Frequency of release: Annual

Forthcoming release: Home Office statistics release calendar

Home Office responsible statistician: Deborah Lader

Press enquires: 0300 123 3535

Public enquiries: FireStatistics@homeoffice.gov.uk

This release presents detailed statistics on fire incidents which covers the financial year year ending March 2020 (1 April 2019 to 31 March 2020) for fire and rescue services (FRSs) in England.

Key results

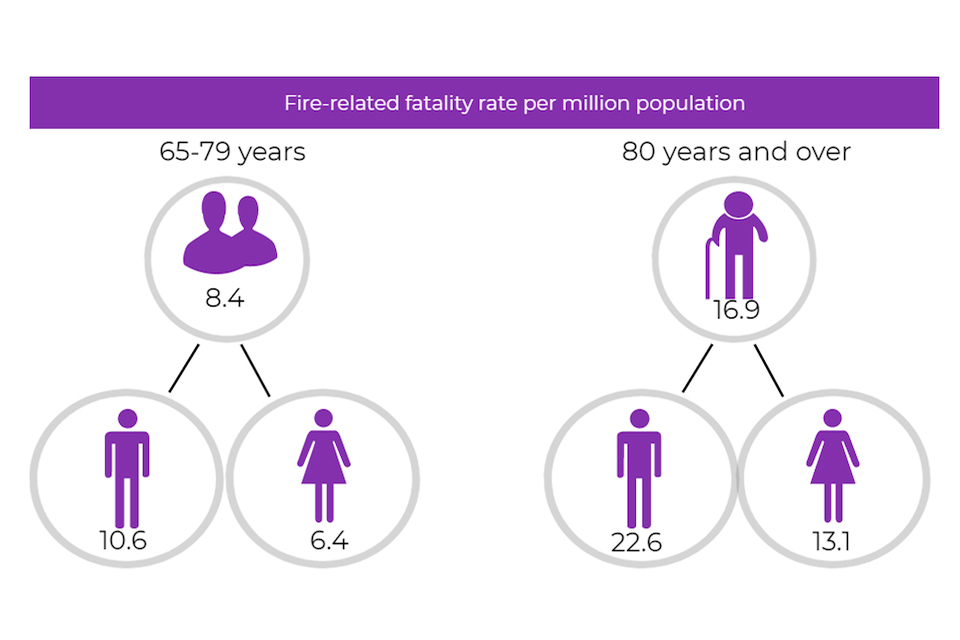

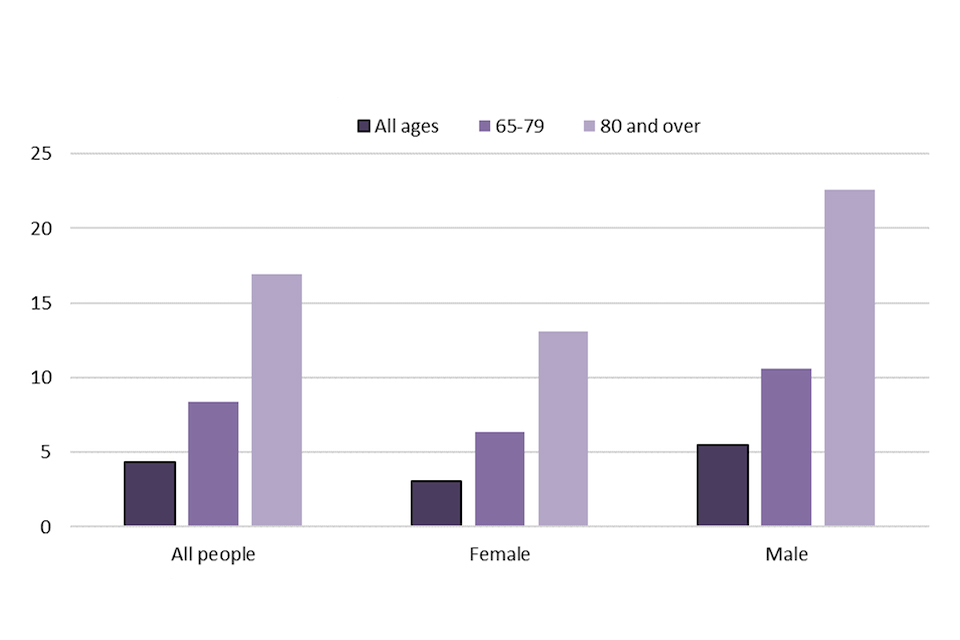

The fire-related fatality rate per million is higher for men and older people. For men aged 65 to 79 the fatality rate was 10.6 per million population while the equivalent rate for women was 6.4 per million. For those aged 80 and over, the rate for men was 22.6 per million and for women was 13.1 per million.

This infographic shows the increasing fire related fatality rate per million population for those aged 65-79 years (8.4) and 80 and over (16.9). It also shows in both age brackets that men have a higher rate - 10.6 rather than 6.4 for 65-79 years and 22.6 rather than 13.1 for 80 years and over.

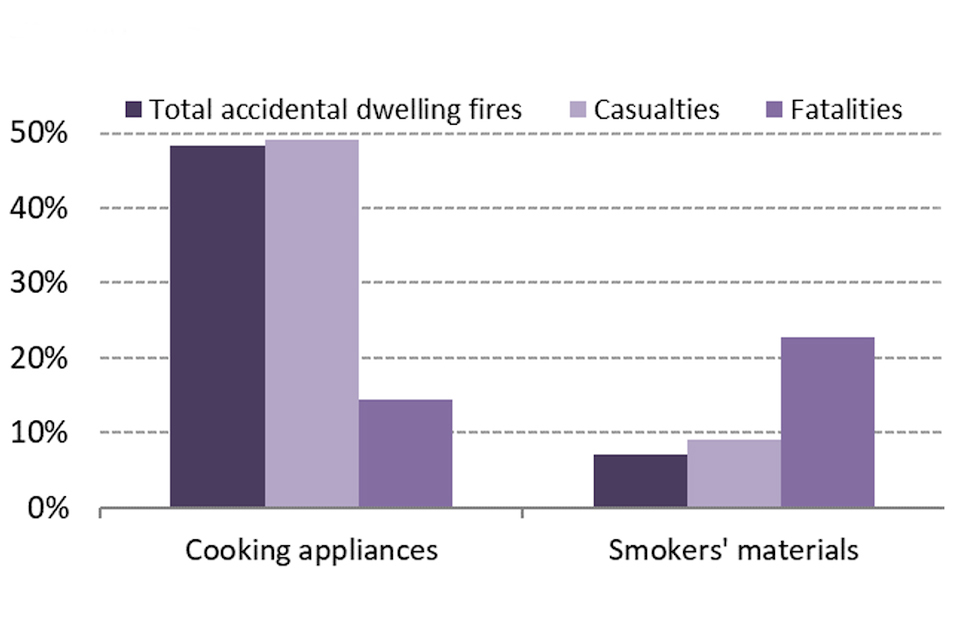

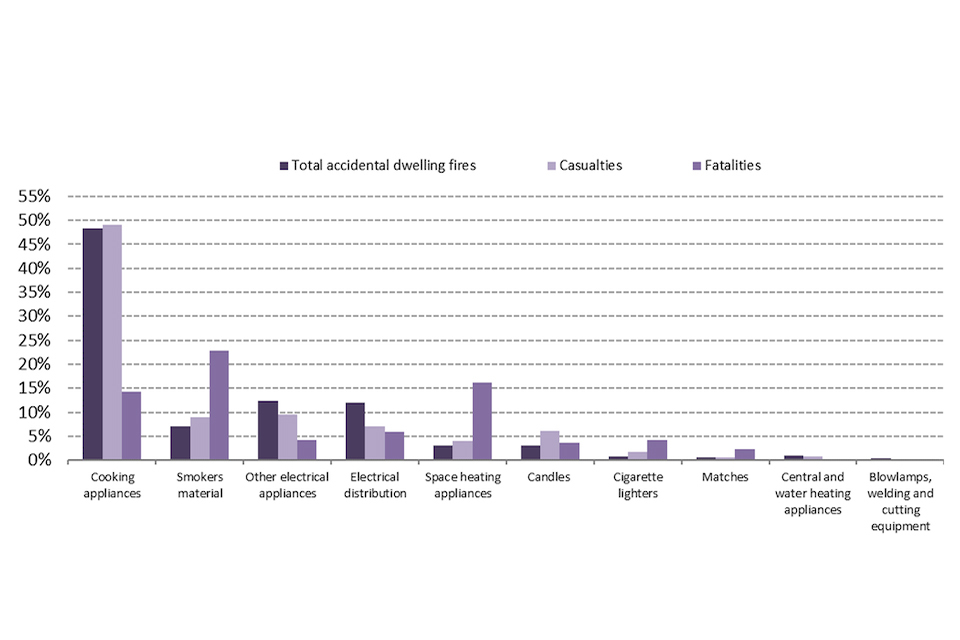

Whilst cooking appliances were by far the biggest ignition category for accidental dwelling fires in 2019/20 (48% of fires) those fires were responsible for 14 per cent of fatalities. Smoking materials showed the reverse with only seven per cent of fires resulting in 23 per cent of fatalities in accidental dwelling fires.

This chart shows while cooking appliances were the ignition source for almost half of all accidental dwelling fires and casualties, the percentage of fatalities is relatively low at just over 10%. The reverse is true of smokers’ materials which shows less than 10% of accidental dwelling fires and casualties but over 20% of fatalities.

1. Overview of incidents attended

1.1 Key results

- in year ending March 2020, 557,299 incidents were attended by FRSs in Englan; this was a three per cent decrease compared with the previous year (576,391) and was driven by a decrease in the number of fires attended, and in particular, secondary fires due to the hot, dry summer of 2018 now being in the comparator year. (Source: FIRE0102: Incidents attended by fire and rescue services in England, by incident type and fire and rescue authority)

- of all incidents attended by FRSs in year ending March 2020, fires accounted for 28 per cent, fire false alarms 42 per cent and non-fire incidents 31 per cent. (Source: FIRE0102: Incidents attended by fire and rescue services in England, by incident type and fire and rescue authority)

- these results are affected, in a small way, by the coronavirus lockdown which started in March 2020

The Fire and Rescue Incident Statistics publication provides information on a quarterly basis on types of and trends in fires, non-fire incidents and fire false alarms attended by fire and rescue services (FRSs). Key points are included here for background to the following chapters.

Types of fire as recorded in the Incident Recording System (IRS)

- Primary – potentially more serious fires that cause harm to people or damage to property; to be categorised as primary these fires must either: occur in a (non-derelict) building, vehicle or outdoor structure, involve fatalities, non-fatal casualties or rescues, or be attended by 5 or more pumping appliances

- Secondary – are generally small outdoor fires, not involving people or property

- Chimney fires – are fires in buildings where the flame was contained within the chimney structure and did not meet any of the criteria for primary fires

The IRS also captures the motive for a fire, which is recorded as either accidental, deliberate or unknown. Those recorded as unknown are included in the accidental category for the purposes of this report. Accidental fires are therefore those where the motive for the fire was presumed to be accidental or is unknown. Deliberate fires include those where the motive was ‘thought to be’ or ‘suspected to be’ deliberate and includes damage to own or other’s property. These fires are not the same as (although include) arson, which is defined under the Criminal Damage Act of 1971 as ‘an act of attempting to destroy or damage property, and/or in doing so, to endanger life’.

1.2 Trends in all incidents

In year ending March 2020, FRSs in England attended around 557,000 incidents, three per cent fewer than in year ending March 2019 (576,000) and 12 per cent more than five years ago in year ending March 2015 (496,000). The number of incidents has been on a general downward trend since the peak of around 1,016,000 incidents attended in 2003/04, levelling off between year ending March 2013 and and year ending March 2015, then increasing in the next four years before decreasing in year ending March 2020. The recent increases were mainly driven by higher numbers of non-fire incidents attended, whereas this year’s decrease in total incidents was driven by a decrease in the number of fires attended due to the hot, dry summer of 2018 being in the comparator year. (Source: FIRE0102: Incidents attended by fire and rescue services in England, by incident type and fire and rescue authority).

Of the total incidents attended in year ending March 2020 around 154,000 (28%) were fires, around 231,000 (42%) were fire false alarms and around 172,000 (31%) were non-fire incidents (also known as special service incidents). (Source: FIRE0102: Incidents attended by fire and rescue services in England, by incident type and fire and rescue authority).

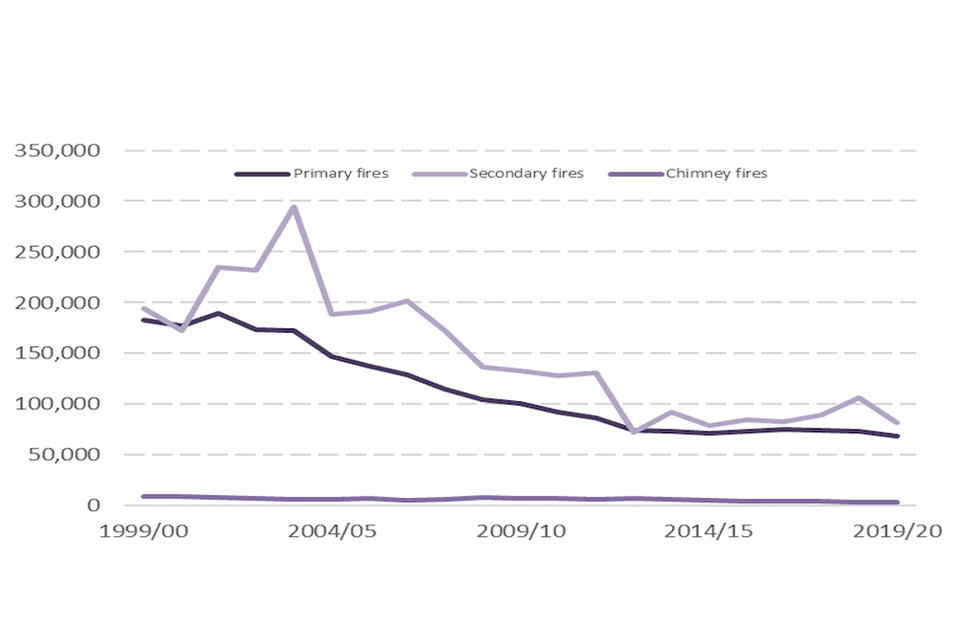

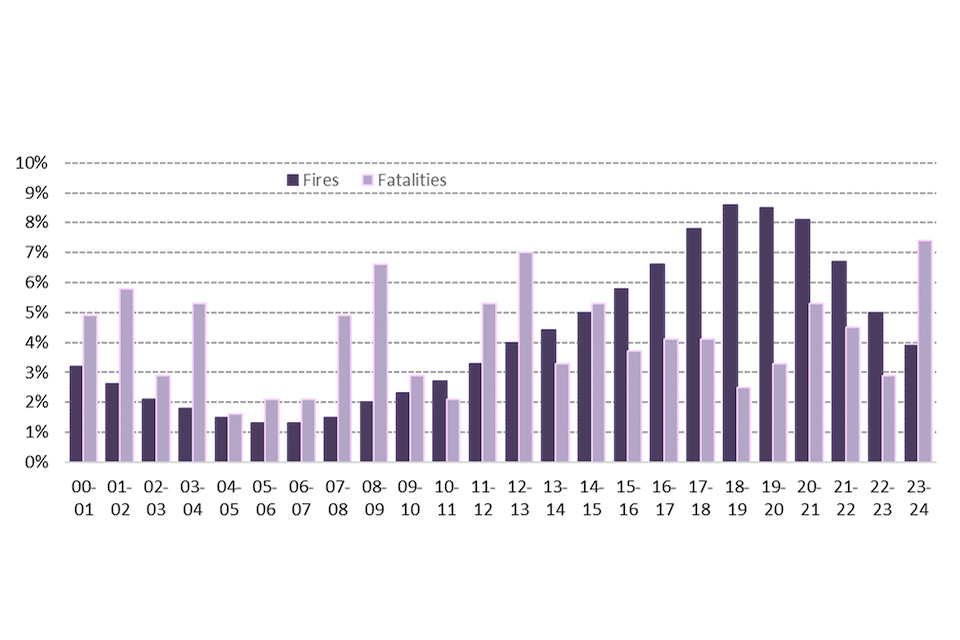

1.3 Fires attended

The total number of fires attended by FRSs decreased for around a decade, falling from a peak of around 474,000 in year ending March 2000 to the previous series low of just over 154,000 in year ending March 2013 (Figure 1.1). After that the number of fires varied between 155,000 (in year ending March 2015) and 183,000 (in 2018 tp 2019), changes that can in part be explained by the weather. In year ending March 2020 there was a new series low of just under 154,000, a 16 per cent decrease on the previous year.

Table 1: Number of fires, comparing year ending March 2020 with year ending March 2019, five years previously in year ending March 2015 and ten years previously in year ending March 2010

| Incident type | 2019/20 compared with: | 2018/19 | 2014/15 | 2009/10 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 153,957 fires | 182,915 | -16% | 155,040 | -1% | 241,462 | -36% | |

| 68,677 primary fires | 73,278 | -6% | 71,116 | -3% | 101,159 | -32% | |

| 28,447 dwelling fires | 29,595 | -4% | 31,334 | -9% | 38,376 | -26% | |

| 25,484 accidental dwelling fires | 26,562 | -4% | 28,321 | -10% | 33,032 | -23% | |

| 82,150 secondary fires | 106,303 | -23% | 78,743 | +4% | 132,941 | -38% |

Figure 1.1: Fires attended by type of fire, England; year ending March 2004 to year ending March 2020

Source: Home Office, FIRE0102: Incidents attended by fire and rescue services in England, by incident type and fire and rescue authority

This chart shows the decline in primary, secondary and chimney fires over the past 20 years with the secondary fires figure peaking in the hot summer of year ending March 2004. Since year ending March 2013 all three fire types have been relatively flat.

2. Fire-related fatalities, non-fatal casualties, rescues and evacuations

As the Incident Recording System (IRS) is a continually updated database, the statistics published in this release may not match those held locally by FRSs and revisions may occur in the future (see the revisions section for further detail). This may be particularly relevant for fire-related fatalities where a coroner’s report could lead to revisions in the data some time after the incident. It should also be noted that the numbers of fire-related fatalities are prone to year-on-year fluctuations due to relatively low numbers.

2.1 Key results

- there were 243 fire-related fatalities in year ending March 2020; this year’s figure is the lowest number in the annual series (from 1981 to 1982)

- 82 per cent (199) of fire-related fatalities were in dwelling fires in year ending March 2020

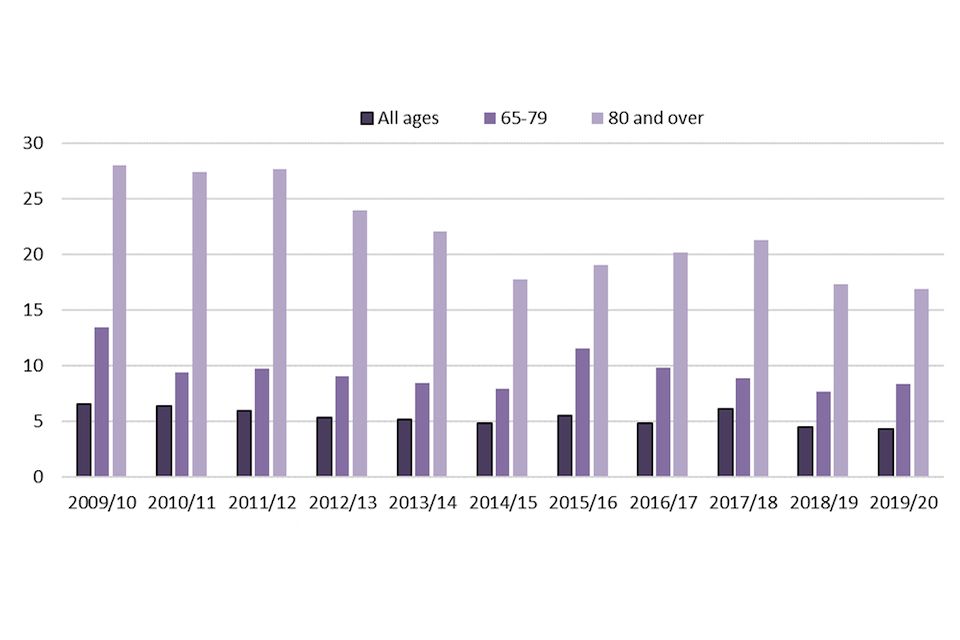

- for every million people in England, there were 4.3 fire-related fatalities in year ending March 2020: the fatality rate was highest among older people: 8.4 people per million for those aged 65 to 79 years old and 16.9 for those aged 80 years and over (Figure 2.1); the fatality rates for age bands within 54 years and younger were all below 5 fatalities per million population

- men have a greater likelihood of dying in a fire than women: the overall fatality rate per million population for males in year ending March 2020 was 5.5 while the rate for females was 3.1 per million; for men aged 65 to 79 the fatality rate was 10.6 per million while the equivalent rate for women was 6.4 per million; for those aged 80 and over, the rate for men was 22.6 per million and for women was 13.1 per million

- the most common cause of death for fire-related fatalities in year ending March 2020 (where the cause of death was known) was ‘overcome by gas or smoke’, given in 30 per cent (73) of fire-related fatalities

- in year ending March 2020, there were 2,998 rescues from primary fires; this was virtually unchanged compared with year ending March 2019 (2,987) and a decrease of six per cent from five years ago in year ending March 2015 (3,184)

- in year ending March 2020, there were 5,172 primary fires that involved an evacuation; this was a decrease of eight per cent compared with year ending March 2019 (5,650) and a decrease of 25 per cent from five years ago in 2014/15 (6,867)

In year ending March 2020, there were 243 fire-related fatalities and 6,910 non-fatal casualties in fires, a decrease of 10 fatalities and around 150 non-fatal casualties since year ending March 2019. The majority of fire-related fatalities in year ending March 2020 occurred in single occupancy dwellings (175; 72%) with the next largest category being other buildings (17; 7%). Single household occupancy (as opposed to homes in multiple occupancy) dwelling fires accounted for 70 per cent of non-fatal casualties in year ending March 2019 but, in contrast to fire-related fatalities, the next largest category was other buildings (15%) (Source: FIRE0501: Fatalities and non-fatal casualties by nation and population, FIRE0502: Fatalities and non-fatal casualties by fire and rescue authority and location group, England, FIRE0503: Fatalities and non-fatal casualties by age gender and type of location).

- the majority, 199 (82%) of fire-related fatalities, were in dwelling fires in year ending March 2020; this percentage is greater than the 198 (78%) in year ending March 2019, 264 (74%) five years previously in year ending March 2015 and 257 (76%) ten years previously in year ending March 2010

- there were 17 fire-related fatalities in other buildings in year ending March 2020, an increase of one from 16 fire-related fatalities in year ending March 2019

- seventy-four per cent (5,133) of non-fatal casualties were in dwelling fires in year ending March 2020: this is a similar proportion to previous years: 73 per cent in year ending March 2019, 78 per cent five years previously in year ending March 2015 and 77 per cent ten years previously in year ending March 2010

- the number of non-fatal casualties in other buildings decreased by 17 per cent from 1,062 in year ending March 2019 to 877 in year ending March 2020; non-fatal casualties in other buildings have fluctuated over the last six years; before this, the number of non-fatal casualties in other buildings was on a downward trend

Fire-related fatalities are those that would not have otherwise occurred had there not been a fire For the purpose of publications, a ‘fire-related’ fatality icludes those that were recorded as ‘don’t know’.

Non-fatal casualties are those resulting from a fire, whether the injury was caused by the fire or not.

2.2 Fire-related fatalities and non-fatal casualties by gender and age

The likelihood of dying in a fire is not uniform across all age groups or genders. Generally, the likelihood increases with age, with those aged 80 and over by far the most likely to die in a fire. Overall, men are nearly twice (1.7 times) as likely to die in a fire as women. Although the overall number of fire-related fatalities is relatively low, and so prone to fluctuation, these general patterns have been consistent since data became available in 2009/10. (Source: FIRE0503: Fatalities and non-fatal casualties by age gender and type of location)

Specifically:

- forty-six per cent of all fire-related fatalities in England (105 fatalities) were 65 years old and over in year ending March 2020, compared with 21 per cent (1,451) of all non-fatal casualties; these proportions are similar to the previous year, with 42% for all fire-related fatalities and 20% for non-fatal casualties; the figures for dwellings show a similar story

- for every million people in England, there were 4.3 fire-related fatalities in year ending March 2020: the fatality rate was highest among older people: 8.4 people per million for those aged 65 to 79 years old and 16.9 for those aged 80 and over (Figure 2.1); the fatality rates for age bands for 54 years and younger were all below five fatalities per million population

- men have a greater likelihood of dying in a fire than women; the overall fatality rate per million population for males in year ending March 2020 was 5.5 while the rate for females was 3.1 per million; for men aged 65 to 79 the fatality rate was 10.6 per million while the equivalent rate for women was 6.4 per million; for those aged 80 and over, the rate for men was 22.6 per million and for women was 13.1 per million (Figure 2.2)

- there were 152 male and 87 female fire-related fatalities in year ending March 2020, with four recorded as ‘not known’

Figure 2.1: Fatality rate (fatalities per million people) for all ages and selected age bands, England; year ending March 2010 to year ending March 2020

Source: Home Office, FIRE0503: Fatalities and non-fatal casualties by age gender and type of location

This chart shows that since year ending March 2010 those aged 65-79 and 80 and over have always had a greater fatality rate than “all ages”. The figures for those aged 80 and over have decreased from around 28 to around 16 fatalities per million people over this time.

Figure 2.2: Fatality rate (fatalities per million people) for all ages and selected age bands by gender, England; year ending March 2020

Source: Home Office, FIRE0503: Fatalities and non-fatal casualties by age gender and type of location

This chart shows the increasing fatality rate for both women and men from all ages to 65-79 and then 80 and over. It also shows male fatality rates are clearly higher for all three age groups shown.

2.3 Causes of deaths and injuries

The IRS records the cause of death or nature of injury for fire-related fatalities and non-fatal casualties in fires. As for almost every year since the start of the online IRS in year ending March 2010, the most common cause of death for fire-related fatalities in year ending March 2020, where known, was ‘overcome by gas or smoke’.

Specifically:

- the most common cause of death for fire-related fatalities in year ending March 2020 (where the cause of death was known) was ‘overcome by gas or smoke’, given in 30 per cent (73) of fire-related fatalities; this was followed by ‘burns alone’ (29%; 70 fire-related fatalities) and the combination of ‘burns and overcome by gas and smoke’ (20%; 48 fire-related fatalities)

- the proportions for causes of death in fire-related fatalities are fairly stable across most years, except for year ending March 2018 where the ‘unspecified’ category was higher (27% compared with a usual range of between 10–20%) due to the Grenfell Tower fire, where a large proportion of the fatalities are recorded as ‘unspecified’ while the public inquiry into the fire is still ongoing (Source: FIRE0506: Fatalities and non-fatal casualties from accidental dwelling fires by age and cause)

- there were 4,531 non-fatal casualties from accidental dwelling fires in year ending March 2020, including those who received first aid (1,450) and who were advised to seek precautionary checks (1,172); when these two groups are removed and non-fatal casualties requiring hospital treatment are looked at, the largest category of injury was ‘overcome by gas or smoke’ (913; 48%) followed by ‘burns’ (385; 20%) and ‘other breathing difficulties’ (297; 16%); all other categories combined comprised the remaining 16 per cent of injuries (Source: FIRE0506: Fatalities and non-fatal casualties from accidental dwelling fires by age and cause)

2.4 Rescues and evacuations

A rescue is where a person has received physical assistance to get clear of the area involved in the incident.

An evacuation is the direction of people from a dangerous place to somewhere safe.

The IRS records the exact number of people rescued from primary fires attended by FRSs. The number of people rescued from primary fires attended by FRSs has been on a downward trend since the online IRS was introduced, decreasing from around 4,400 in year ending March 2010 to around 3,000 in year ending March 2020 (Figure 2.3). This has been driven by a decrease in rescues from primary dwelling fires.

For evacuations from fires attended by FRSs, the IRS records how many people were assisted in eight separate bands (e.g. 6-20 means there were between 6 and 20 people evacuated from a fire). The number of primary fires attended that involved an evacuation has also been on a downward trend (Figure 2.4), decreasing from around 9,300 in year ending March 2010 to around 5,200 in year ending March 2020. This decrease has been mainly driven by those in primary other building fires but also by primary road vehicle and dwelling fires.

Specifically:

- in year ending March 2020, there were 2,998 people rescued from primary fires; this was virtually unchanged compared with year ending March 2019 (2,987) and a decrease of six per cent from five years ago in year ending March 2015 (3,184). In year ending March 2020, over three quarters (78%) of rescues were from primary dwelling fires with other building, road vehicle and other outdoor fires accounting for 16 per cent, four per cent and two per cent, respectively

- in year ending March 2020, there were 5,172 primary fires that involved an evacuation; this was a decrease of eight per cent compared with year ending March 2019 (5,650) and a decrease of 25 per cent from five years ago in year ending March 2015 (6,867); whilst the decreases can in part be explained by a reduction in primary fires, they only decreased by six per cent (compared with year ending March 2019) and three per cent (compared with year ending March 2015); the most common evacuation band was ‘1 to 5’ (i.e. there were 1 to 5 people evacuated from the fire), accounting for 89 per cent of primary fires that involved an evacuation (Source: FIRE0511: Rescues and evacuations from primary fires by location group, England).

Figure 2.3: Number of people rescued from primary fires, England; year ending March 2010 to year ending March 2020

Source: Home Office, FIRE0511: Rescues and evacuations from primary fires by location group, England

This chart shows the increasing fatality rate for both women and men from all ages to 65-79 and then 80 and over. It also shows male fatality rates are clearly higher for all three age groups shown.

Figure 2.4: Number of primary fires with an evacuation, England; year ending March 2010 to year ending March 2020

Source: Home Office, FIRE0511: Rescues and evacuations from primary fires by location group, England

This chart shows the number of primary fires with an evacuation in England decreased from around 9,300 in year ending March 2010 to around 5,200 in year ending March 2020.

3. Extent of damage and spread of fire

The IRS also records the extent of damage and the spread of fire. The extent of damage (due to smoke, heat, flame and water etc.) to dwellings and other buildings is recorded by the area in square metres broken down into thirteen categories, from ‘None’ up to ‘Over 10,000’ square metres[footnote 1]. The spread of fire in dwellings and other buildings is recorded according to the extent the fire reached different parts of the building based on eight categories from ‘no fire damage’ to ‘fire spread to the whole building’.

3.1 Key results

- the average area of damage to dwellings (excluding those over 5,000m2 in England in year ending March 2020 was 16.2m2, no change compared with the previous two years but a decrease of eight per cent from five years ago (17.6m2 in year ending March 2015) and an 18 per cent decrease from ten years ago (19.7m2 in year ending March 2010)

- the average area of damage to other buildings (excluding those over 1,000m2) increased by one per cent to 28.5m2 in year ending March 2020 compared with 28.3m2 in year ending March 2019; this was a decrease of four per cent from five years ago (29.6m2 in year ending March 2015) and a decrease of three per cent from ten years ago (29.4m2 in year ending March 2010)

- in year ending March 2020, seven per cent of fires in purpose-built high-rise (10+ storeys) flats spread beyond the room of origin, compared with seven per cent of fires in purpose-built medium-rise flats (4-9 storeys), nine per cent in purpose-built low-rise (1-3 storeys) flats and 14 per cent of fires in houses, bungalows, converted flats and other dwellings combined

3.2 Extent of damage

The average extent of damage to dwellings has generally fallen since year ending March 2004 but has levelled off over the last five years. The average extent of damage to other buildings has fluctuated since year ending March 2010 (from when the average extent of damage to other buildings started being more accurately recorded)[footnote 2].

Specifically:

- in year ending March 2020, the average area of damage to dwellings (excluding those over 5,000m2) in England was 16.2m2; this was no change compared with year ending March 2019 but an eight per cent decrease since year ending March 2015 (17.6m2) and an 18 per cent decrease since year ending March 2010 (19.7m2) (Source: FIRE0204: Average area of fire damage in dwelling fires, England)

- the average area of damage to other buildings (excluding those over 1,000m2) increased by one per cent from 28.3m2 in year ending March 2019 to 28.5m2 in year ending March 2020; this has fluctuated over the years: a decrease of four per cent since year ending March 2015 (29.6m2) and a decrease of three per cent since year ending March 2010 (29.4m2) (Source: FIRE0305: Average area of fire damage in other building fires, England)

Dwelling fires with more than 5,000m2 of damage and other buildings fires with more than 1,000m2 of damage can skew the averages, so were removed for the averages reported here. However, for completeness, other calculations are available in tables FIRE0204: Average area of fire damage in dwelling fires, England and FIRE0305: Average area of fire damage in other building fires, England, which accompany this release. It should be noted that excluding these area categories removed 1 dwelling fire (less than 0.01% of all dwelling fires) and 170 other building fires (1.2% of all other building fires) for year ending March 2020.

3.3 Spread of fire

In year ending March 2020, nearly one third (30%) of dwelling fires had no fire damage, in just under a third (32%) the damage was limited to the item first ignited and in just under a quarter (24%) the damage was limited to the room of origin. The remaining 13 per cent of dwelling fires were larger fires, either “limited to floor of origin”, “limited to 2 floors”, “affecting more than 2 floors”, “limited to roofs and roof spaces” and the “whole building”.

Seven per cent of fires in purpose-built high-rise (10 or more storeys) flats spread beyond the room of origin[footnote 3], a similar percentage to purpose-built medium-rise (4-9 storeys) flats (7%) and purpose-built low-rise (1-3 storeys) flats (9%) and lower than the 14 per cent for houses, bungalows, converted flats and other dwellings combined, all of which were similar to previous years.

In year ending March 2020, the proportion of fires affecting the ‘whole building’ in primary other building fires was 15 per cent, which is similar to previous years. Between year ending March 2011 and year ending March 2020 the proportion of primary other building fires that were ‘limited to item 1st ignited’ has been on a slow increasing trend from 26 per cent to 29 per cent. Over the same time period, the percentage of primary other building fires that had no fire damage has been on a slow decreasing trend from 27 per cent to 23 per cent.

In contrast, the proportion of fires affecting the ‘whole building’ in primary dwelling fires was two per cent in year ending March 2020, much lower than the 15 per cent for primary other building fires and is similar to previous years. Between year ending March 2011 and year ending March 2020 the proportion of primary dwelling fires that were ‘limited to item 1st ignited’ has been on a slow increasing trend from 28 per cent to 32 per cent, a trend shared with primary other building fires. Over the same time period, the percentage of primary dwelling fires that had no fire damage has been on a slow decreasing trend 33 per cent to 30 per cent.

Specifically:

- in year ending March 2020, 57 (7%) of the 775 fires in purpose-built high-rise flats spread beyond the room of origin compared with 68 (8%) in the previous year in year ending March 2019 and 38 (5%) five years ago in year ending March 2017. (Source: FIRE0203: Dwelling fires by spread of fire and motive)

- in year ending March 2020, 2,084 (15%) of the 14,308 primary other building fires affected the ‘whole building’ compared with 2,454 (16%) of the 15,025 primary other building fires in the previous year in year ending March 2019 and 2,084 (13%) of the 16,524 primary other building fires five years ago in year ending March 2014. (Source: FIRE0304: Other buildings fire by spread of fire and motive)

4. Causes of dwelling fires and fire-related fatalities

The IRS collects information on the source of ignition (e.g. ‘smokers’ materials’), the cause of fire (e.g. ‘fault in equipment or appliance’), which item or material was mainly responsible for the spread of the fire (e.g. ‘clothing/textiles’), as well as other factors, including ignition power (e.g. gas)[footnote 4].

4.1 Key results

- cooking appliances were the largest ignition category for accidental dwelling fires in year ending March 2020, accounting for 48 per cent of these fires and 49 per cent of non-fatal casualties but only accounted for 14 per cent of the fire-related fatalities

- smokers’ materials were the source of ignition in seven per cent of accidental dwelling fires and nine per cent of accidental dwelling fire non-fatal casualties but were the largest ignition category for fire-related fatalities in accidental dwelling fires, accounting for 23 per cent in year ending March 2020

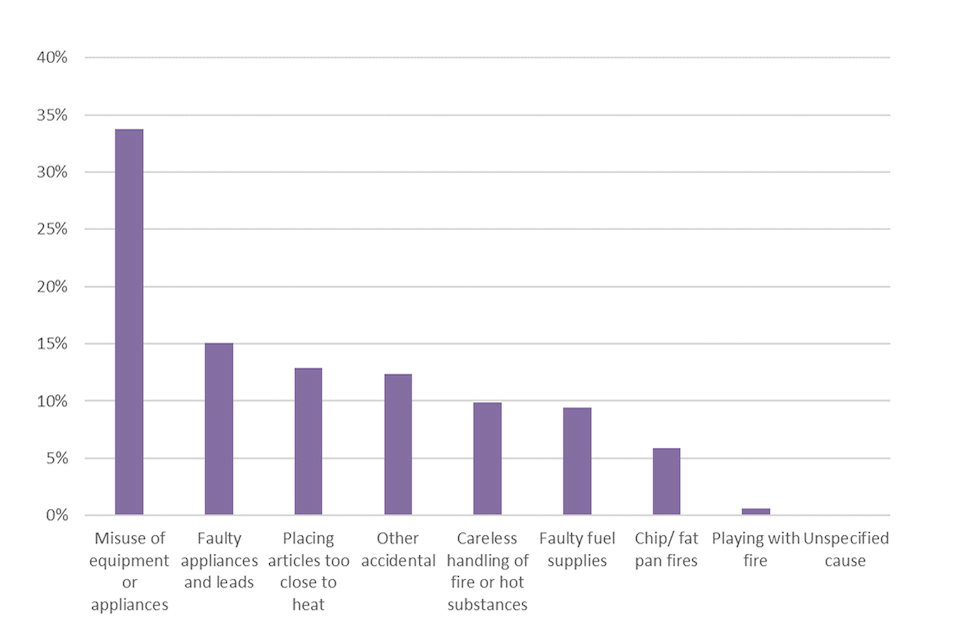

- of the 25,555 accidental dwelling fires in year ending March 2020, 34 per cent were caused by “misuse of equipment or appliances”, no change from year ending March 2019; the second largest cause category was “faulty appliances and leads” which caused 15 per cent of all accidental dwelling fires

4.2 Sources of ignition in accidental dwelling fires

Since year ending March 2011, the number of accidental dwelling fires has decreased by 20 per cent. This was in large part driven by a 22 per cent decrease (between year ending March 2011 and year ending March 2020) in fires where the ignition source was “cooking appliances”, as these make up nearly half of all accidental dwelling fires. Other ignition types that have contributed to the decrease include “space heating appliances” and “other electrical appliances” (decreases of 44% and 23% over the same time period, respectively). (Source: FIRE0602: Primary fires fatalities and non-fatal casualties by source of ignition)

Figure 4.1 shows the proportion of accidental dwelling fires, and their resulting non-fatal casualties and fire-related fatalities, attributable to different sources of ignition[footnote 5]. It shows that while some ignition sources cause many fires, they often result in relatively few fire-related fatalities, and vice versa. (Source: FIRE0601 to FIRE0605 Cause of fire)

Figure 4.1: Percentage of fires, non-fatal casualties and fire-related fatalities in accidental dwelling fires by selected sources of ignition, England; year ending March 2020

Source: Home Office, FIRE0602: Primary fires fatalities and non-fatal casualties by source of ignition

This chart shows while cooking appliances were the ignition source for almost half of all accidental dwelling fires and casualties, the percentage of fatalities is relatively low at around 14%. To a lesser extent this is true of “other electrical appliances” and “electrical distribution”. The reverse is true of smokers’ materials, space heating appliances, cigarette lighters and matches to varying degrees.

4.3 Main cause of, and material mainly responsible for, dwelling fires

Exactly how a fire originated, and then the material which was mainly responsible for it spreading, are both important determinants in the outcomes of fires. Notably, and similarly to sources of ignition, the most common causes and materials responsible for the spread of fires are not those that lead to the greatest proportion of fire-related fatalities.

Specifically:

- of the 25,555 dwelling fires with accidental causes in year ending March 2020, 34 per cent were caused by “misuse of equipment or appliances” (Figure 4.2), no change from year ending March 2019; the second largest cause category was “faulty appliances and leads” which caused 15 per cent of all accidental dwelling fires (Source: FIRE0601: Primary fires in dwellings and other buildings by cause of fire)

- the material mainly responsible for the development of the fire in 24 per cent of all dwelling fires and the item first ignited in 26 per cent of all dwelling fires in year ending March 2020 was “Textiles, upholstery and furnishings”; the former caused 59 per cent of all fire-related fatalities in dwellings (Source: FIRE0603: Primary fires fatalities and non-fatal casualties by item first ignited, FIRE0604: Primary fire fatalities and casualties by material responsible for development of fire)

- “Food” was the material mainly responsible for the development of the fire in 20 per cent of all dwelling fires and the item first ignited in 28 per cent of all dwelling fires in year ending March 2020; however, it was the material mainly responsible for the development of the fire in only three per cent of all dwelling fire-related fatalities

Figure 4.2: Percentage of fires in accidental dwelling fires by cause of fire, England; year ending March 2020

Source: Home Office, FIRE0601: Primary fires in dwellings and other buildings by cause of fire

This chart shows the cause of fire in accidental dwelling fires. Misuse of equipment or appliance was clearly the largest cause (34%) with faulty appliances and leads (15%), placing articles too close to heat (13%) and “other accidental” (12%). “Careless handling of fire or hot substance”, “Faulty fuel supplies”, “Chip/fat pan fires”, “Playing with fire” and “unspecified cause” all were below 10%.

5. Smoke alarm function

5.1 Key results

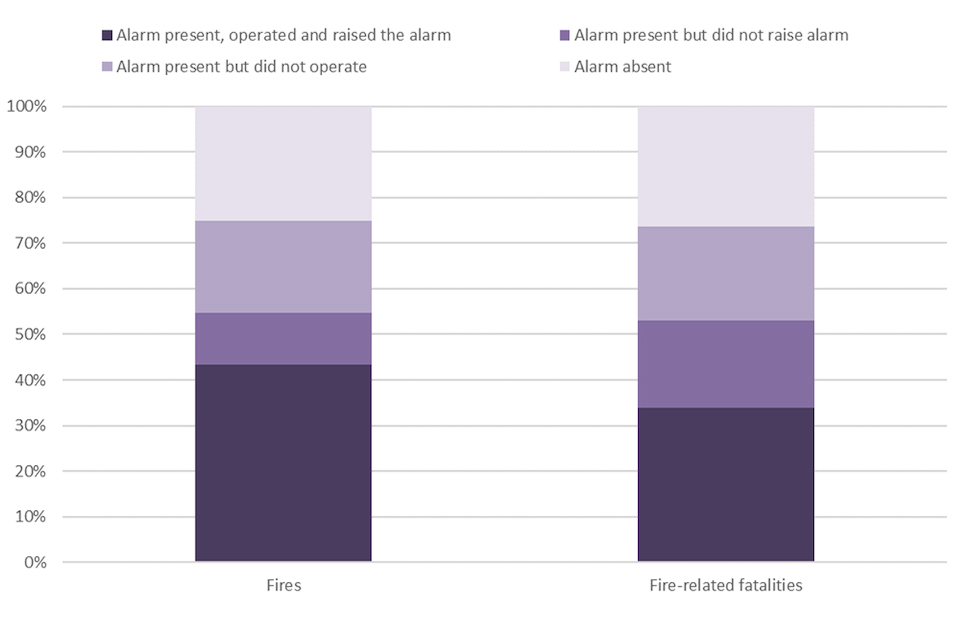

- fires where a smoke alarm was not present accounted for 24 per cent (6,988) of all dwelling fires and 26 per cent (52) of all dwelling fire-related fatalities in year ending March 2020; this is in the context of nine per cent of dwellings not having a working smoke alarm in year ending March 2019 (the latest year for which data are available)

- mains powered smoke alarms continued to have a lower “failure rate” than battery powered smoke alarms; 21 per cent of mains powered smoke alarms failed to operate in dwelling fires in year ending March 2020 compared with 37 per cent of battery powered smoke alarms

The IRS records information on whether a smoke alarm was present at the fire incident, as well as the type (mains or battery powered) and whether or not it functioned as intended i.e. if it operated and if it raised the alarm.

Reasons alarms did not function as expected

Did not operate: alarm battery missing; alarm battery defective; system not set up correctly; system damaged by fire; fire not close enough to detector; fault in system; system turned off; fire in area not covered by system; detector removed; alerted by other means; other; not known.

Operated but did not raise the alarm: no person in earshot; occupants did not respond; no other person responded; other; not known.

5.2 Smoke alarms in dwelling fires

Fires where a smoke alarm was present but either did not operate or did not raise the alarm accounted for just under a third (31%) of all dwelling fires in year ending March 2020, an unchanged percentage compared with year ending March 2019.

‘Fire products did not reach detector(s)’[footnote 6] and ‘fire in area not covered by system’ accounted for 66 per cent of mains powered smoke alarm failures and continued to be the principal reasons mains powered smoke alarms failed to operate in dwelling fires in year ending March 2020, as in previous years (Table 1). Similarly, the main reasons battery powered smoke alarms failed to operate in dwelling fires were due to ‘fire products did not reach detector(s)’ and ‘fire in area not covered by system’ (60% of dwelling fires in year ending March 2020). These have also been the principal causes of battery powered smoke alarm failures in previous years.

As for all years since year ending March 2011, in year ending March 2020 the most common category of smoke alarm failure in dwelling fires involving any casualties was ‘Other’ (including ‘alerted by other means’, ‘system damaged by fire’, ‘other’ and ‘don’t know’), which accounted for 31 per cent of these fires where battery powered smoke detectors were present and 35 per cent where mains powered detectors were present (Table 2). (Source: FIRE0704: Percentage of smoke alarms that did not operate in primary dwelling fires and fires resulting in casualties in dwellings, by type of alarm and reason for failure)

Table 2: Reason smoke alarms did not operate in dwelling fires and dwelling fires resulting in casualties, by type of alarm, England, year ending March 2020

| Reason for failure | Battery powered | Mains powered | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fires | Fire resulting in casualties |

Fires | Fire resulting in casualties |

|

| Missing battery | 10% | 12% | 1% | 3% |

| Defective battery | 9% | 17% | 0% | 3% |

| Other act preventing alarm from operating | 2% | 10% | 6% | 18% |

| Fire products did not reach detector(s) | 47% | 12% | 51% | 21% |

| Fire in area not covered by system | 13% | 10% | 15% | 9% |

| Faulty system / incorrectly installed | 2% | 10% | 4% | 12% |

| Other | 18% | 31% | 22% | 35% |

Notes:

Includes all non-fatal casualties and fire-related fatalities.

Mains powered smoke alarms includes those recorded as ‘mains and battery’ in the IRS, therefore there are a small number of mains powered smoke alarms where the reason for failure is ‘missing battery’ or ‘defective battery’.

5.3 Smoke alarm function and outcomes

A smoke alarm was present and raised the alarm (i.e. functioned as desired) in 45 per cent of dwelling fires in year ending March 2020 but in only 33 per cent of fire-related fatalities, highlighting the importance of having both working smoke alarms and enough of them to cover all areas in a dwelling. (Source: FIRE0701: Percentage of households owning a smoke alarm or working smoke alarm, England and Wales or England, FIRE0702: Primary fires, fatalities and non-fatal casualties by presence and operation of smoke alarms)

By combining IRS and English Housing Survey data, Home Office statisticians have calculated that you are around eight times more likely to die in a fire if you do not have a working smoke alarm in your home[footnote 7].

Figure 5.1, shows the proportion of dwelling fires and fire-related fatalities in dwelling fires where the alarm was “present, operated and raised the alarm”, “present but did not raise the alarm”, “present but did not operate” or “absent”. It shows that the proportion of dwelling fires where the alarm was present, operated and raised the alarm was higher than for fire-related fatalities in those fires. Alarms were absent in a slightly higher proportion for fire-related fatalities (26%) than in dwelling fires (24%). This pattern is consistent with previous years.

Figure 5.1: Smoke alarm operation outcomes in primary dwelling fires and fire-related fatalities, England; year ending March 2020

Source: Home Office, FIRE0702: Primary fires, fatalities and non-fatal casualties by presence and operation of smoke alarms

This chart shows that when an alarm is present, operated and raised the alarm there is a higher proportion of fires (43%) than fatalities (34%).

For fires the remaining proportions are alarm absent (25%), alarm present but did not operate (20%) and alarm present but did not raise alarm (11%).

For fire-related fatalities the remaining proportions are alarm absent (26%), alarm present but did not operate (21%) and alarm present but did not raise alarm (19%).

5.4 Smoke alarms in primary other building fires

Fires where a smoke alarm was not present accounted for 46 per cent of all primary other building fires in year ending March 2020. This has been relatively stable since year ending March 2013. (Source: FIRE0706: Primary fires and casualties in other buildings by presence and operation of smoke alarms)

Fires where a smoke alarm was not present accounted for 35 per cent of all primary other building fire-related fatalities and non-fatal casualties (combined) in year ending March 2020, two percentage points greater than in year ending March 2019. Considering the relatively small numbers involved this has been quite stable since year ending March 2013 ranging from 42 per cent to 29 per cent. (Source: FIRE0706: Primary fires and casualties in other buildings by presence and operation of smoke alarms)

Fires where a smoke alarm was present but did not raise the alarm accounted for five per cent, and fires where an alarm was present but did not operate 12 percent, of primary other building fires in year ending March 2020. These proportions have been relatively stable since year ending March 2011. (Source: FIRE0706: Primary fires and casualties in other buildings by presence and operation of smoke alarms)

6. Temporal and seasonal fire analyses

6.1 Key results

- in year ending March 2020, the number of fires showed a strong daily pattern, with 46 per cent of all fires occurring where the time of call was between 16:00 and 22:00

- the hourly number of fire-related fatalities does not show a daily pattern, with the number of fire-related fatalities roughly equal between day and night hours

- April experienced the most fires per day attended by FRSs in year ending March 2020 (an average of 627), whilst December and February had the fewest (both 301 fires per day on average); this is different to the previous year where July averaged the most fires per day (a much higher than average 1,039) while December had the fewest (297); July’s figures in year ending March 2019 were linked to the hot, dry summer of 2018.

Fires and fire-related fatalities are affected by both seasonality and time of day. Similar to previous years, there were generally fewer fires where the time of call was between midnight and 11am, but the number of fire-related fatalities remained relatively high despite lower incidence of fires and with no strong temporal pattern. This difference is also found for accidental dwelling fires.

6.2 Temporal fire analyses

Forty-six per cent of all fires in year ending March 2020 occurred where the time of call was between 16:00 and 22:00 (Figure 6.1). These were the six individual hours with the highest proportion of fires (by time of call), which was also true in year ending March 2019 and year ending March 2018. The peak hours were between 18:00 and 20:00 and accounted for at least 8.5 per cent of fires each in year ending March 2020, similar to previous years. (Source: FIRE0801: Percentage of fires and fire-related fatalities by hour of the day)

Figure 6.1 Percentage of fires and fire-related fatalities by hour of the day, England; year ending March 2020

Source: Home Office, FIRE0801: Percentage of fires and fire-related fatalities by hour of the day

This chart shows the proportion of fires through the day peaking in the evening between 18.00 and 20.00 and decreasing to 05.00 to 07.00.

The spread of fatalities through the day does not show a discernible pattern.

In contrast to the number of fires, the hourly number of fire-related fatalities showed less of a pattern across the day in year ending March 2020, as in previous years. Fire-related fatalities were roughly equal between day and night hours. The peak hours were 23:00-00:00 (7.4%), 12:00-13:00 (7.0%) and 08:00-09:00 (6.6%). While the six individual hours with the highest proportion of fires were continuous and accounted for 46 per cent of incidents, the six highest for fatalities were spread throughout the day and accounted for just 32 per cent (Figure 6.1).

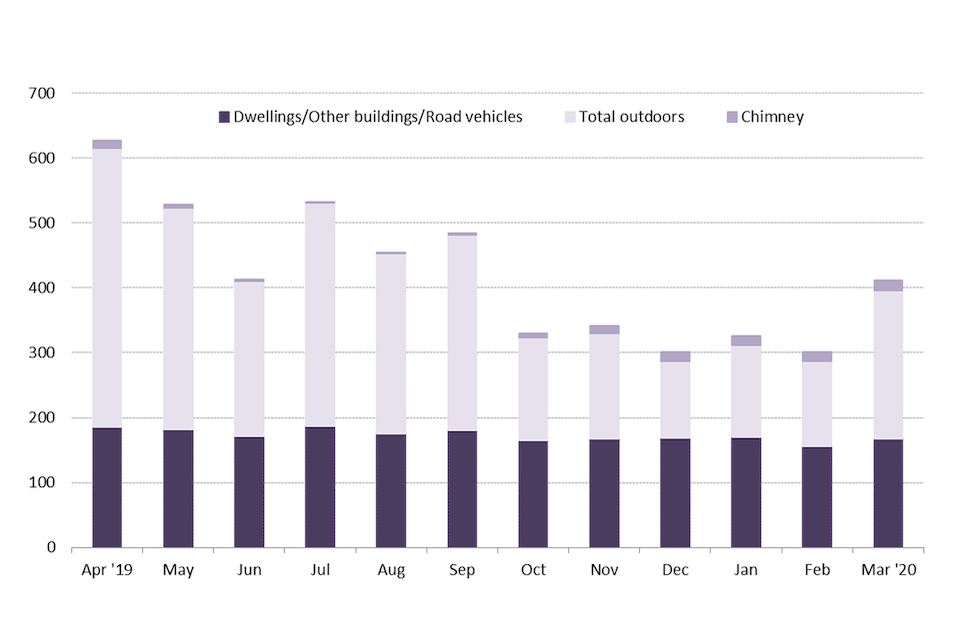

6.3 Seasonal fire analyses

Very little seasonality was evident in dwelling, other building and road vehicle fires, however outdoor fires and chimney fires showed much stronger seasonal effects. There tends to be more grassland, refuse and other outdoor fires in the summer months and these seem to reflect weather patterns. This was particularly so for the exceptionally hot and dry July 2018, which had the highest daily rate of fires for any month of any year recorded in the IRS from year ending March 2011 to year ending March 2020 (see FIRE0802: Daily rate of fire incidents by month and location). Conversely, chimney fires are more numerous in the winter months. These seasonal effects are broadly similar each year but are affected by changes in weather patterns specific to that year, e.g. in year ending March 2020 the values were skewed towards spring/early summer with a peak in April while in year ending March 2019 they were highest in June and July.

Specifically:

- the high rate of fires in April 2019 was driven by fires in ‘grassland, woodland and crops’, which had a daily rate 32 per cent greater than any other month (161 fires per day, compared to 122 in July) however refuse fires, other outdoor and secondary fires, dwelling fires and other building fires all recorded their highest rate that month

- the daily rate of all fires for year ending March 2020 was 421 fires per day. 57 per cent (239) of these were all types of outdoor fires

- fires in dwellings, other buildings and road vehicles showed relatively little seasonality, with a slight increase in summer months, and the daily rate of these fires attended varied between 156 and 186 per month in year ending March 2020

Figure 6.2 shows the average daily number of dwelling/other building/road vehicle, outdoor, and chimney fires in year ending March 2020 across the year. It shows how stable dwelling/other building/road vehicle fires are across months, compared with seasonal outdoor fires and, to a lesser extent, chimney fires.

Figure 6.2: Average daily fire incidents by month and location, England; year ending March 2020

Source: Home Office, FIRE0802: Daily rate of fire incidents by month and location

This chart shows that April had the most average daily fire incidents and December and February the least in year ending March 2020. It also shows that while dwelling, other building and road vehicle fire numbers are quite stable through the year outdoor fires are seasonal with higher numbers in the summer months.

7. Further information

This release contains statistics about incidents attended by fire and rescue services (FRSs) in England. The statistics are sourced from the Home Office’s online Incident Recording System (IRS). This system allows FRSs to complete an incident form for every incident attended, be it a fire, a false alarm or a non-fire incident (also known as a Special Service incident). The online IRS was introduced in April 2009. Previously, paper forms were submitted by FRSs and an element of sampling was involved in the data compilation process.

Fire and Rescue Incident Statistics and other Home Office statistical releases are available via the Statistics at Home Office pages on the GOV.UK website.

Data tables linked to this release and all other fire statistics releases can be found on the Home Office’s ‘Fire statistics data tables’ page.

Guidance for using these statistics and other fire statistics outputs, including a Quality Report, is available on the fire statistics guidance page.

The information published in this release is kept under review, taking into account the needs of users and burdens on suppliers and producers, in line with the Code of Practice for Statistics. If you have any comments, suggestions or enquiries, please contact the team via email using firestatistics@homeoffice.gov.uk or via the user feedback form on the fire statistics collection page.

7.1 Revisions

The IRS is a continually updated database, with FRSs adding incidents daily. The figures in this release refer to records of incidents that occurred up to and including 31 March 2020. This includes incident records that were submitted to the IRS by 14 June 2020, when a snapshot of the database was taken for the purpose of analysis. As a snapshot of the dataset was taken on 14 June 2020, the statistics published may not match those held locally by FRSs and revisions may occur in the future. This is particularly the case for statistics with relatively small numbers, such as fire-related fatalities. For instance, this can occur because coroner’s reports may mean the initial view taken by the FRS will need to be revised; this can take many months, even years, to do so.

7.2 COVID-19 and the impact on the IRS

The figures presented in this release relate to incidents attended by FRSs during the period April 2019 to the end of March 2020. In response to the coronavirus pandemic, restrictions in England and Wales started from 12 March 2020 and lockdown was applied on 23 March 2020, which imposed strict limits on daily life. The start of the restrictions and the first eight days of lockdown are therefore captured in IRS data for the year ending March 2020.

Home Office statisticians have been monitoring incidents on the IRS since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic lockdown to ensure that data quality has not been reduced, and that all incidents are recorded. In addition, FRSs were asked to upload the information more quickly after attending an incident so that the IRS could be used to produce Management Information to monitor the impact of COVID-19 on FRSs capacity. Analysis of this time period will be included in the next Fire and rescue incident statistics release, covering the year ending June 2020.

7.3 Other related publications

Home Office publish five other statistical releases covering fire and rescue services:

- Fire and rescue incident statistics, England: provides statistics on trends in fires, casualties, false alarms and non-fire incidents attended by fire and rescue services in England, updated quarterly

- Detailed analysis of non-fire incidents attended by fire and rescue services, England: focuses on non-fire incidents attended by fire and rescue services across England, including analysis on overall trends, fatalities and non-fatal casualties in non-fire incidents, and further detailed analysis of different categories of non-fire incidents

- Fire and rescue workforce and pensions statistics: focuses on total workforce numbers, workforce diversity and information regarding leavers and joiners; covers both pension fund income and expenditure and firefighters’ pension schemes membership; and includes information on incidents involving attacks on firefighters

- Fire prevention and protection statistics, England: focuses on trends in smoke alarm ownership, fire prevention and protection activities by fire and rescue services

- Response times to fires attended by fire and rescue services, England: covers statistics on trends in average response times to fires attended by fire and rescue services

The Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government publish one statistical release on fire:

- English housing survey: fire and fire safety report: focuses on the extent to which the existence of fire and fire safety features vary by household and dwelling type

Fire statistics are published by the other UK nations:

Scottish fire statistics and Welsh fire statistics are published based on the IRS. Fire statistics for Northern Ireland are published by the Northern Ireland Fire and Rescue Service using data from a system similar to the Incident Recording System, which means that they are not directly comparable to English, Welsh and Scottish data.

National Statistics

These statistics have been assessed by the UK Statistics Authority to ensure that they continue to meet the standards required to be designated as National Statistics. This statistical bulletin is produced to the highest professional standards and is free from political interference. It has been produced by statisticians working in accordance with the Home Office’s Statement of compliance with the Code of Practice for Official Statistics, which covers Home Office policy on revisions and other matters. The Chief Statistician, as Head of Profession, reports to the National Statistician with respect to all professional statistical matters and oversees all Home Office National Statistics products with respect to the Code, being responsible for their timing, content and methodology. This means that these statistics meet the highest standards of trustworthiness, impartiality, quality and public value, and are fully compliant with the Code of Practice for Statistics.

-

For a list of the damaged area size bands, see the Fire Statistics Definitions document. ↩

-

For detail on the discontinuity between year ending March 2005 and year ending March 2010 please see page 17 in the year ending March 2012 Fire incidents response times report. ↩

-

Fire spread beyond the room of origin comprises the following IRS categories: where the spread of fire was limited to the floor of origin, where the spread of fire was limited to 2 floors, where the spread of fire was affecting more than 2 floors and where the fire spread to the whole building. ↩

-

For a more detailed definition on the different types of cause of fire, see the definitions document and IRS Guidance. ↩

-

This excludes ‘Other/Unspecified’. ↩

-

Fire products did not reach detectors(s) can be where the smoke alarms present were poorly sited (e.g. not on the floor of origin) so the smoke did not reach the detector. ↩

-

For details of the calculation and assumptions made, see the definitions document. ↩