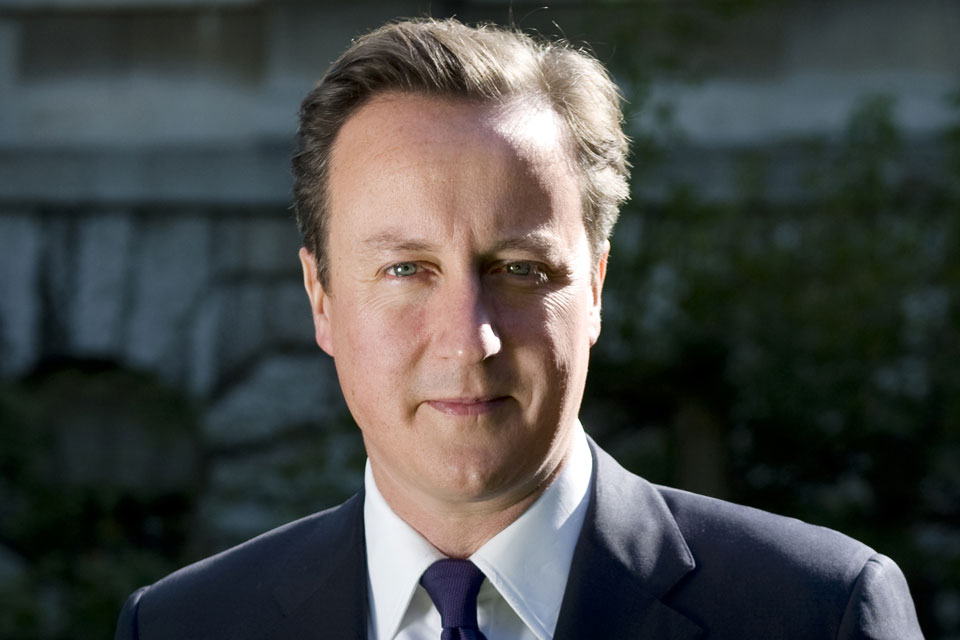

Watch out, universities; I'm bringing the fight for equality in Britain to you: article by David Cameron

Writing in the Sunday Times, the Prime Minister explained the government's plans to achieve real equality in Britain.

When you look at Britain today, it is much harder to see the open discrimination and blatant racism of decades gone by. Instead there is a grown-up country that, despite our challenges, is largely at ease with the diversity of our open society. We also know what we are trying to achieve. Not a process of total assimilation, where people lose their whole identity. Nor is it ‘separate development’ where we encourage — or even tolerate — communities living apart. But instead, we are in the process of building a common home together, where our shared British values should help us to live side by side. And we aim for a land where at last, everyone — no matter their gender, race, background or sexuality — can be accepted for who they are and expect to be treated with true equality.

But when you look more under the surface, it’s clear that we’ve still got some distance to travel to achieve the ‘one nation’ ideal. Consider this: if you’re a young black man, you’re more likely to be in a prison cell than studying at a top university. Only 1 in 10 of the poorest white boys go into higher education at all. There are no black generals in our armed forces and just 4% of chief executives in the FTSE 100 are from ethnic minorities.

What does this say about modern Britain? Are these just the symptoms of class divisions or a lack of equal opportunity? Or is it something worse — something more ingrained, institutional and insidious? We’ve come a long way — including in my own party. When I became an MP in 2001, I barely had a single colleague from an ethnic minority background. Today our MPs include the sons, daughters and grandchildren of Ghanaians, east African Indians, Iranian dissidents, Pakistanis and Indians. But there is much more to do, and these examples I mention should shame our country and jolt us into action.

So what are we going to do? First, we’ve got to extend life chances. Last month I spoke about the subtle social inequality that can hold people back. It can start with poor parenting, and that damage can then be compounded in a poor or coasting school. And later, in adolescence, young people can lack access to vital, life-enriching experiences, mentors and support networks. We’ve got to think radically here — and with expanded parenting provision, teaching character in schools, and new mentoring and work experience programmes, I think we can rise to the challenge.

But improving life chances only gets you part of the way there. You can have a great start in life, but still be held back — often invisibly — because of your background or the colour of your skin. So the second thing we need to do is tackle discrimination. I don’t care whether it’s overt, unconscious or institutional — we’ve got to stamp it out. We don’t need politically correct, contrived and unfair solutions. Quotas don’t fix the underlying problems. To succeed, we must be far more demanding of our institutions, and be relentless in the pursuit of creative answers.

One area we should look at is the criminal justice system. It’s disgraceful that if you’re black, it seems you’re more likely to be sentenced to custody for a crime than if you’re white. We should investigate why this is and how we can end this possible discrimination. That’s why I have asked David Lammy MP to lead a review of the overrepresentation of black and minority ethnic (BME) communities in the criminal justice system. And this will include possible sentencing and prosecutorial disparity.

Another area where we need action is our universities. It’s striking that in 2014, our top university, Oxford, accepted just 27 black men and women out of an intake of more than 2,500. I know the reasons are complex, including poor schooling, but I worry that the university I was so proud to attend is not doing enough to attract talent from across our country. And these problems go deep elsewhere, too: white British men from poor backgrounds are 5 times less likely to go into higher education than others.

There is a real chance to help nudge universities into making the right choices and reaching out in the right ways. For example, there was compelling evidence that people with ethnic-sounding names were less likely to get call-backs for jobs, even with the same qualifications. That’s why, last year, I persuaded universities and many other organisations to introduce name-blind applications.

Today I can announce a further step. We intend to legislate to place a new transparency duty on universities to publish data routinely about the people who apply to their institution, the subject they want to study, and who gets offered a place. And this will include a full breakdown of their gender, ethnicity and socioeconomic background. And to focus minds further, Sajid Javid, the business secretary, will chair a summit tomorrow in Downing Street with schools and universities to help chart other ways forward.

This is all part of our ambitious ‘2020 agenda’ for BME communities. Not just greater numbers at university, but many more jobs, apprenticeships and start-up loans. And I am determined to fix that stubborn problem of underrepresentation in our police and armed forces. To succeed, I want to issue a great call to arms to institutions all across our country. It’s not enough to simply say you are open to all. Ask yourselves: are you going that extra mile to really show people that yours can be a place for everyone, regardless of background? We can all dig deeper — but I’m confident we can get there. This is Britain; there’s nothing we can’t achieve together.

We have a claim to be the most successful multiracial, multifaith democracy on earth. In Britain, the children and grandchildren of migrants sit at the Cabinet table, run world-beating companies and win Oscars, Turner prizes and Olympic golds. But our relative success isn’t enough so long as there are young people who don’t feel like there’s a fair chance for them. Discrimination and disadvantage only feed those who preach a message of grievance and victimhood — and that makes building one nation a harder and longer task. I want this to be the government that finally makes the difference. So let’s ask those big questions. Let’s find the solutions. Let us together finish the fight for real equality in Britain.