Work Choice impact evaluation

Updated 16 April 2025

Applies to England, Scotland and Wales

DWP ad hoc research report no. 110

A report of research carried out by the Department for Work and Pensions.

Crown copyright 2025.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. View this licence or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email psi@nationalarchives.gov.uk.

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email socialresearch@dwp.gov.uk.

First published February 2025.

ISBN 978-1-78659-804-2

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Summary

Work Choice provided specialist employment support to disabled people. This report assesses the impact of Work Choice on the labour market and benefit outcomes of participants and presents a cost-benefit analysis of Work Choice.

Executive Summary

This report estimates the impact and cost-effectiveness of Work Choice.

Work Choice was a voluntary employment programme for people with disability barriers to employment, and people at risk of losing their job as a result of their disability, for whom other DWP provision was not suitable. DWP contracted external providers to deliver Work Choice. Providers offered both work entry support to help participants find and obtain employment, and in-work support to help participants progress and develop in work.

Work Choice was introduced across England, Scotland, and Wales in October 2010. The final referrals to Work Choice occurred in February 2018 and Work Choice support ended in March 2019.

This report provides estimates of the impact of Work Choice using Propensity Score Matching (PSM). The labour market outcomes of 144,838 Work Choice participants are compared against a carefully constructed comparison group of non-participants. The results presented might be subject to some degree of over or underestimation of the programme’s impacts. This depends on the extent to which the analysis controls for any selection effects whereby Work Choice participants may systematically differ from non-participants.

Due to contractual changes impacts are estimated separately for those referred to Work Choice between October 2010 and October 2015, under pre 2015 contract terms (early cohort), and those referred between April 2015 and February 2018 under 2015 or 2017 contract terms (later cohort). Labour market outcomes for the early cohort can be observed for eight years following referral, which is considerably longer than for most DWP employment programme evaluations.

Eight years after referral to Work Choice early cohort participants had a payrolled employment rate 10.9 percentage points (pp) higher than the comparison group, and had spent, on average, 337 more days in payrolled employment (11.5pp) over that time. Early cohort participants were also 7.3 pp less likely to be receiving looking for work or low-income benefits than the comparison group, and had spent, on average, 215 fewer days receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit (-7.4pp) over that time.

Similar results were found for the later cohort. Four years after referral to Work Choice later cohort participants had a payrolled employment rate 11.4 pp higher than the comparison group and had spent 179 more days in payrolled employment (12.3pp) over that time. Participants were also 7.5 pp less likely to be receiving looking for work/low-income benefits than the comparison group, and had spent, on average, 106 fewer receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit (-7.3pp) over that time.

In addition, Work Choice reduced the likelihood of individuals being neither in payrolled employment nor receiving looking for work/low-income benefits. Eight years after referral to Work Choice early cohort participants were 2.6 pp less likely to be neither in employment nor receiving looking for work/low-income benefits than the comparison group, and had spent, on average, 101 fewer days in this state (-3.5pp) over that time. Four years after referral to Work Choice, later cohort participants were 2.3 pp less likely to be neither in employment nor receiving looking for work/low-income benefits than the comparison group, and had spent, on average, 45 fewer days in this state (-3.1pp) over that time.

Analysis of participants referred between October 2010 and March 2012 suggests that the above impacts will persist longer than the eight years assessed for the early cohort.

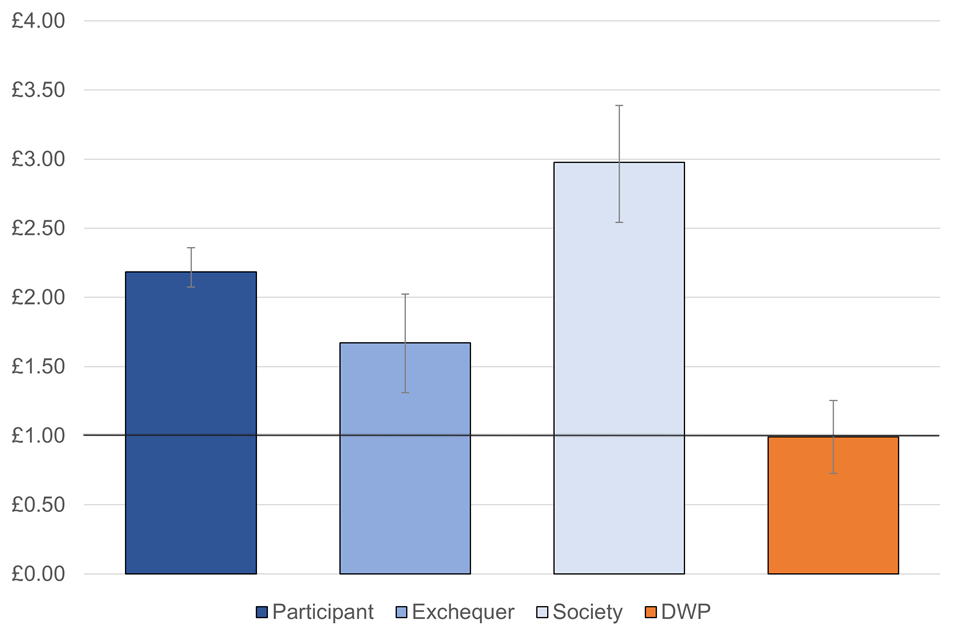

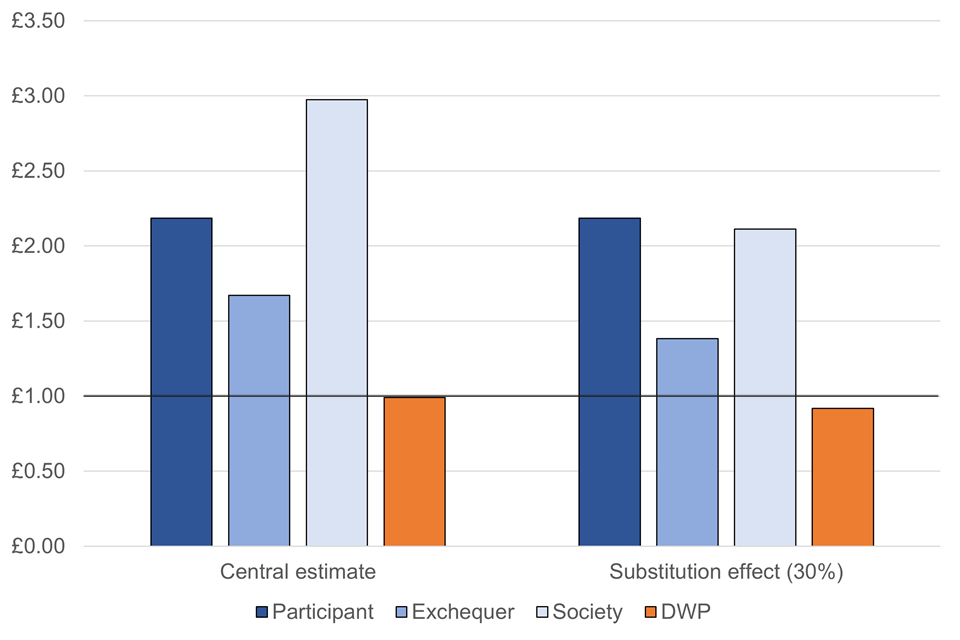

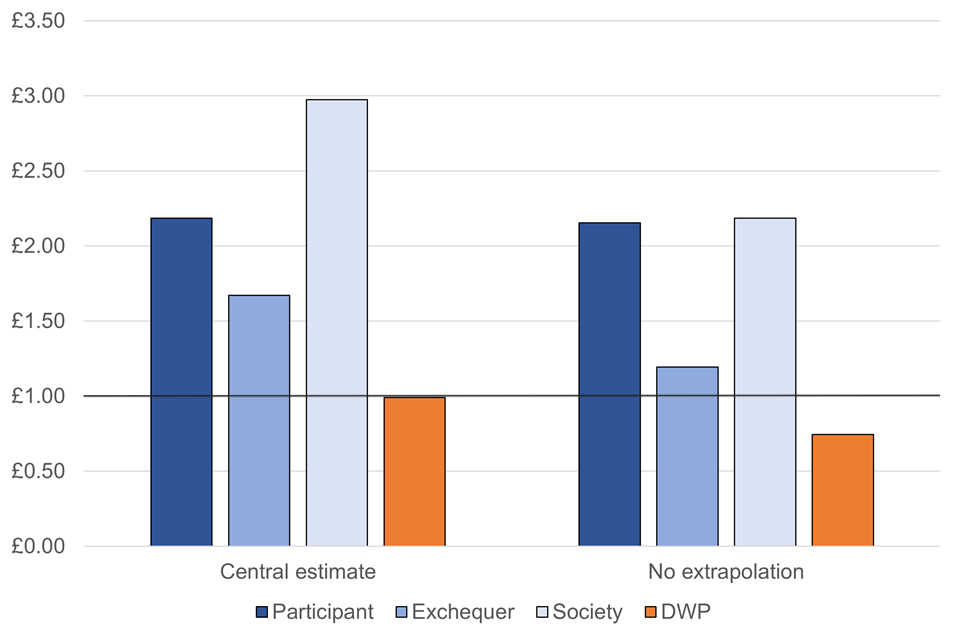

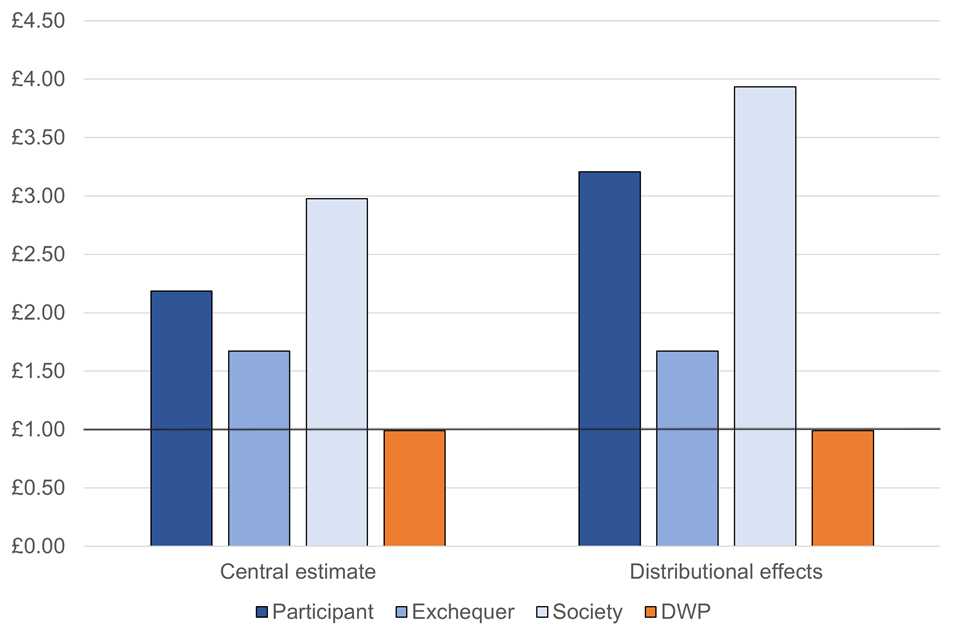

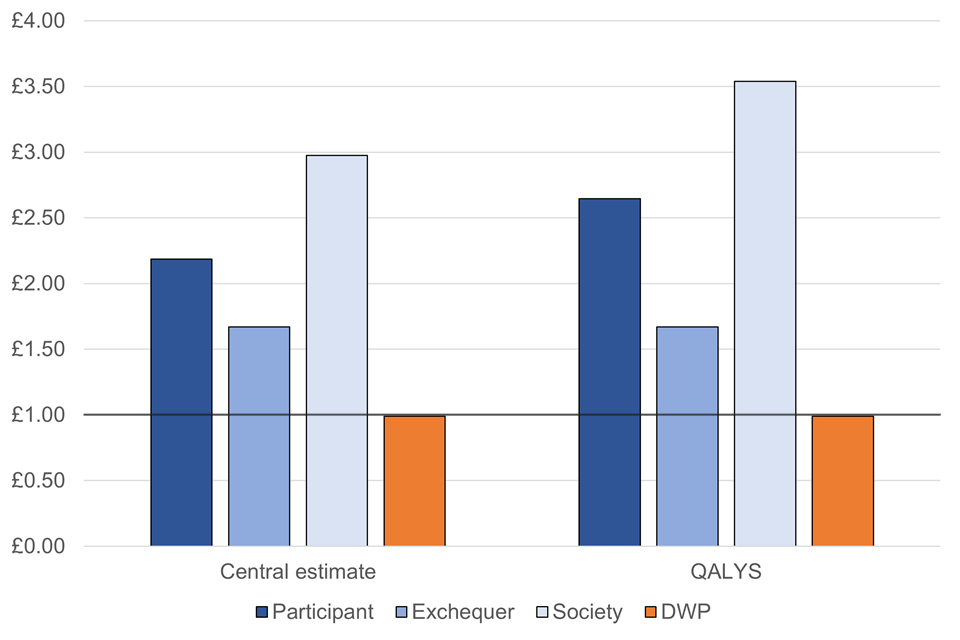

At an estimated cost of £4,590 per participant, cost benefit analysis based on the estimated impacts shows that, per £1 of cost, the returns from Work Choice were:

- For the participant: £2.19, with a range of £2.07 to £2.36

- For DWP: £0.99, with a range of £0.73 to £1.25

- For the Exchequer: £1.67, with a range of £1.31 to £2.02

- For society: £2.98, with a range of £2.36 to £3.39

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor Richard Dorsett of the University of Westminster for his considered and thoughtful advice on the analysis.

We also thank Simon Marlow and Diane Hume for their insight and guidance, and Ali McAuley and James Lind for their previous work on Work Choice.

Author details

Beth Atkinson, Operational Research Analyst at the Department for Work and Pensions

Connor Lowe, Economist at the Department for Work and Pensions

Glossary

| Term | Meaning |

|---|---|

| BCR | Benefit cost ratio |

| Caliper | The maximum distance between propensity scores acceptable for a match |

| CBA | Cost benefit analysis |

| Common support | The overlap in matched treatment and comparison group observations based on their propensity scores. |

| Comparison Group | Carefully selected subset of the comparison pool, selected to have characteristics as similar as possible, to act as a counterfactual |

| Confidence interval | A 95% confidence interval is a range within which the true population would fall for 95% of the times the sample was repeated. For example, for a 95% confidence interval, the true (unknown) value of the estimate would be expected to lie within it 19 times out of 20 |

| DEA | Disability Employment Adviser |

| DLA | Disability Living Allowance |

| DWP | Department for Work and Pensions |

| ESA | Employment Support Allowance |

| HMRC | HM Revenue and Customs |

| IB | Incapacity Benefit |

| IS | Income Support |

| JCP | Jobcentre Plus |

| JSA | Jobseeker’s Allowance |

| NHS | National Health Service |

| OBR | Office for Budget Responsibility |

| ONS | Office for National Statistics |

| Payrolled employment | Employment paid via the HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) Pay As You Earn (PAYE) system. This excludes self-employment and a small number of employees. |

| Participant Group | The group of individuals who participated in the programme being evaluated |

| PIP | Personal Independence Payment |

| PRaP | Provider Referrals and Payments system |

| Propensity Score | The probability that an individual with a given set of characteristics has some chosen attribute, for example, participates in an intervention |

| PSM | Propensity Score Matching. A statistical technique in which individuals are identified as statistically similar to each other based on a set of characteristics |

| QALY | Quality-adjusted life years |

| SCBA | The DWP Social Cost Benefit Analysis model |

| SDA | Severe Disablement Allowance |

| SMD | Standardised Mean Difference. A statistic which indicates how different the treatment and comparison groups are across characteristics at various stages of the propensity score matching procedure. |

| SRO | Statutory Referral Organisation. Must be an organisation that has been commissioned by, or has a formal contract or agreement with, an agent of a statutory body. Specifically, they must act on behalf of a Local Authority, the National Health Service (or in Wales, Local Health Boards and in Scotland Health Boards, or a Local Education Authority |

| TA | Training Allowance |

| UC | Universal Credit |

1. Work Choice policy and design

1.1 Policy background

Prior to Work Choice DWP offered support to disabled people seeking work through WORKSTEP and Work Preparation. WORKSTEP was an employment programme providing support to disabled people facing complex barriers to obtaining and keeping a job. It included a supported placement scheme that paid wage subsidies to employers who hired disabled people and subsidised the wages of workers in sheltered workshops and factories. Work Preparation was an individually tailored programme that helped disabled people prepare for work.

In response to an evaluation of WORKSTEP (Purvis, Lowrey, and Dobb, 2006), the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) conducted a review of disability employment support, and a public consultation proposing reform of the existing disability employment provision.

The Green Paper ‘No one written off: Reforming welfare to reward responsibility’ (Department for Work and Pensions, 2008a), and the White Paper ‘Raising expectations and increasing support: Reforming welfare for the future’ (Department for Work and Pensions, 2008b) led to the replacement of WORKSTEP and Work Preparation with Work Choice.

Work Choice aimed to bring together the best elements of these programmes into a single programme. In line with the approach of providing support in kind to employers rather than a direct financial subsidy, the Job Introduction Scheme, which paid employers a weekly grant towards the cost of employing a disabled person for the first six weeks of their employment, was also discontinued.

Shortly after the introduction of Work Choice the findings of the Sayce review into disability employment support were published in ‘Getting in, staying in and getting on’ (Sayce, 2011).The Government subsequently published ‘Disability Employment Support: Fulfilling Potential’ (Department for Work and Pensions, 2012a).

1.2 Work Choice participants

Participation in Work Choice was voluntary. Eligibility rules were broad; participants must have been of working age, resident in England, Scotland, or Wales, and disabled as defined by the Equality Act 2010. The rules also allowed an individual to participate in the programme multiple times, subject to individual suitability tests for each spell.

Suitability was determined through assessment of individual circumstances by Jobcentre Plus (JCP) Work Coaches and Disability Employment Advisers (DEAs). Suitable candidates for Work Choice met all the following criteria:

- experienced complex work-related support needs arising primarily from disability

- had in work requirements which could not immediately be overcome through workplace adjustments required under the Equality Act 2010 and/or by Access to Work support

- needed support in work as well as help with finding work

-

could not be more appropriately helped through other DWP programmes

- following initial support were expected to be able to work for a minimum of 16 hours per week.

Work Choice had three customer groups, supporting both unemployed and employed customers:

- Transition: Participants of the predecessor programmes WORKSTEP and Work Preparation. These people migrated to Work Choice support in contract Year 1. They were typically in supported employment at the point of migration.

- New Flow: Participants with severe and complex disability related barriers to work. Most of this group were receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit, but this was not a requirement. 86% of this group were out of work at the point of referral.

- Retention: Employed participants at risk of falling out of work without the support of the programme. For example, if an employee became newly disabled or their existing disability changed in a way that put their prospects of continued employment at risk.

Of the 246,000 starts on Work Choice, 211,000 (86%) were from the new flow group, and 35,000 (14%) were from the transition or retention groups.

Only new flow participants in receipt of a looking for work/low-income benefit were considered for inclusion in this analysis. DWP holds the data required for this analysis for benefit recipients. DWP does not hold up to date data for all individuals not receiving looking for work/low-income benefits at referral. Most people in the transition and retention groups were in work at the point of referral to Work Choice, and therefore less likely to be receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit.

1.3 The routes to Work Choice participation

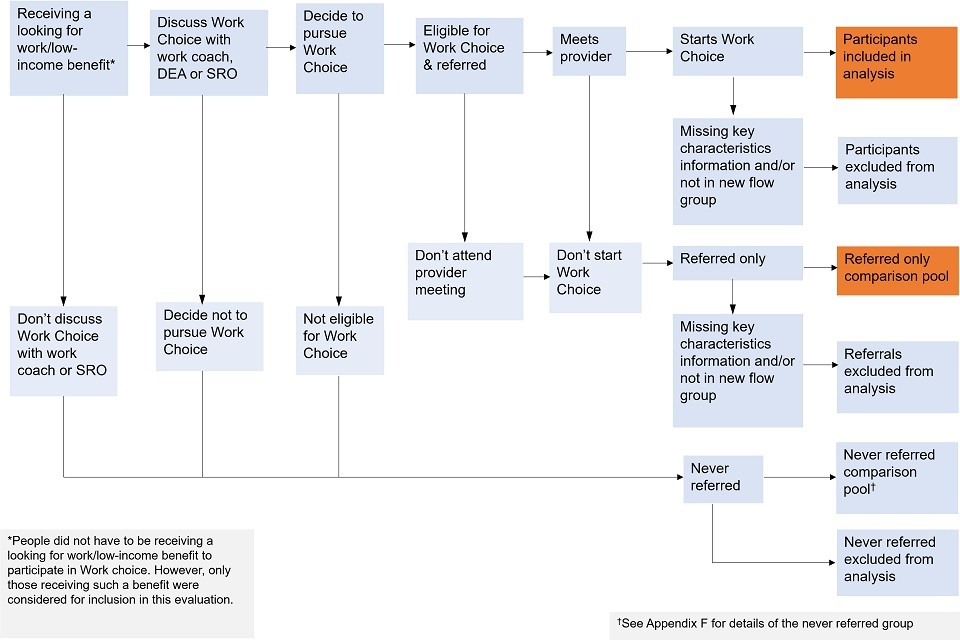

The different groups of participants had different routes into Work Choice.

When Work Choice superseded WORKSTEP in October 2010, all WORKSTEP participants were invited to transfer to the new programme (including people in supported businesses in subsidised places). Those who chose continued support were termed ‘transition’ customers and were migrated to Work Choice.

Retention customers found Work Choice through similar routes to new flow participants, but from a starting position of wanting support to retain their existing job rather than to find and enter employment. For transition and retention customers we expect a different set of participation considerations and decisions to the new flow volunteers who are the focus of this analysis.

For new flow participants the route to participation had two stages:

- Referral to Work Choice

- Starting on Work Choice

The main route to Work Choice was through JCP Work Coaches or DEAs, but potential participants could also be introduced by specialist Statutory Referral Organisations (SROs) such as social services and secondary mental health services. Where SRO introductions occurred, Jobcentre staff undertook suitability assessments and made referrals to employment provision.

Referral to a Work Choice provider was the outcome of decisions made by both the individual and Work Coach/DEA, and either could propose participation in the programme. Following consultation with individuals about what kind of support, if any, would be appropriate, Work Coaches/DEAs decided whether to refer them to Work Choice. Work Coaches/DEAs considered multiple factors including client eligibility, suitability, distance from the labour market, motivation, and the availability of other provision. This decision process differed between individual Work Coaches/DEAs (Purvis and others, 2013). Potential participants also made their own decision on whether to agree to a referral.

Once referred using the Provider Referrals and Payments (PRaP) IT system volunteers met with the Work Choice provider. These meetings were expected to take place within ten working days of referral. At this meeting, if both parties were content, the referral was registered as a ‘start’ on the PRaP system, and the individual was considered to have started Work Choice provision as a participant.

78% of referrals resulted in a start on Work Choice. 19% of referrals resulted in a provider meeting but no start. Non-participation identified at the provider meeting was registered as ‘did not start’ on the referral record, but data doesn’t capture whether this was customer or provider driven non-participation. Although forbidden within provider guidance, the 2013 research (Purvis and others, 2013) showed that some potential participants were deemed to be unsuitable and rejected by the provider. Providers reported that the main reasons they thought some volunteers were unsuitable were motivation and distance from the labour market, i.e., that they did not wish to find work or that they were unlikely to be supported into work within the time-limits of Work Choice. Guidance allowed for providers to reject potential participants where their provision had reached capacity but there are no records of this occurring.

1% of referrals did not result in an initial provider meeting. These were logged on PRaP as ‘did not attend’. These individuals may have changed circumstances post-referral but pre-meeting, such as a worsening health condition, a move into employment, or other life changes that reversed the initial decision to volunteer. Participation decisions may have also been indirectly influenced by provider behaviour. For example, the length of time from referral to provider meeting is partly determined by provider business processes such as caseworker availability, premises, location, and booking systems. This affects when the initial meeting takes place. The longer the waiting period the higher the likelihood that an individual’s circumstances change, which could affect their participation decision.

The remaining 2% of referrals resulted in non-participation because the referred individuals could not be contacted by the provider.

1.4 Work Choice support

Work Choice support had three stages:

-

Module one (work entry support): Individuals received help with personal and job skills, and work-related advice including; vocational guidance, job-search support, job application support, labour market advice e.g., Better Off In Work calculations and assistance with tax credit applications, brokerage between employers and participants, Access to Work support, and support for participants wanting to enter self-employment. For most participants six months in module one was considered adequate. If providers believed a participant would benefit from extra time up to twelve months in module one was allowed.

Participation in Work Choice ended if participants did not find employment during module one or moved directly into employment not supported by the Work Choice provider (‘unsupported employment’). If they moved into employment/self-employment of 16 hours or more a week directly supported by the Work Choice provider (‘supported employment’) they entered modules two or three depending on the support required. -

Module two (short/medium-term in-work support): Under supported employment the Work Choice provider kept in regular contact with the employed participant, and regularly reviewed development plans with the participant and employer to check necessary support was in place and that participants were progressing and developing in their job. Providers ensured that, for at least eight hours per month, participants were engaged in activity that would aid progression towards unsupported employment within two years. Support was tailored to individuals. Examples of support included mentoring, job coaching, assistance with Access to Work applications, advising on workplace adjustments, problem solving in response to issues arising, and sourcing suitable training (Purvis and others, 2013). The maximum duration of module two was two years. If a participant entered unsupported employment during module two their Work Choice participation ended.

-

Module three (Longer term in-work support): Providers ensured that, for at least four hours per month, participants were engaged in activity aimed at developing their full potential at work. Module three had no durational limit and participants could move between modules two and three as required. If a participant entered unsupported employment during module three their Work Choice participation ended.

From April 2017 modules two and three were combined into a single ‘In Work Support’ module. All in-work participants received help and intensive support towards reaching the goal of sustained unsupported employment. Provider support ended after two years in the combined ‘In Work Support’ module. The design of Work Choice is described in detail in the provider guidance (Department for Work and Pensions, 2011 and 2017).

Within this modular structure providers had flexibility in their support offer, and Work Choice support can be described as ‘black box’.

Participants could remain on Work Choice for only a few months if they found unsupported employment quickly, or, prior to April 2017, they could remain on Work Choice indefinitely if they remained in long term supported employment. However, most participant journeys lasted less than a year.

The participants included in this analysis all started Work Choice in module one (work entry support).

DWP contracted external providers to deliver Work Choice across 28 geographic areas known as ‘Contract Package Areas’ (CPAs). These primary providers managed supply chains of subcontracted providers to deliver the service. Over the life of the programme eight prime providers delivered Work Choice services.

Initially, one of the prime providers, Remploy, delivered Work Choice as a non-departmental government body, operating as a company limited by guarantee, and directly funded by DWP under Grant in Aid arrangements. In April 2015 grant funding arrangements ended. Remploy continued to deliver Work Choice as a commercial entity through a contracted prime provider model identical to other providers.

At launch, in all but two delivery areas participants could choose between Remploy and one of the other eight prime providers delivering Work Choice. However, in the 2013 research (Purvis and others, 2013) it was found that participants would often ask for advice from their Work Coach/DEA. When giving advice DEAs considered geographical location, particular support needs, type of work sought and previous knowledge of provider delivery standards.

1.5 Provider payment model

Contracted providers were paid by DWP through a structured funding model. Payments were primarily made through service fees, but providers also received payment by results outcome fees when individual participants achieved specific employment-duration based outcomes.

There were two payment by results outcomes. First, a 13-week short-duration outcome where eligible employment included either supported employment or unsupported employment. Secondly, a longer-duration outcome fee was paid if participants undertook 26 weeks of unsupported employment within a 30-week period, beginning on the first day of unsupported work. Time in supported employment was excluded from the longer-duration outcome definition.

Contract changes introduced in 2015 and 2017 made modifications to the delivery model and cost structure of Work Choice. These should be considered when interpreting the impact estimates and cost-benefit analysis. Work Choice had three commercial phases of delivery with different cost structures. Minor service offer changes were also introduced in each phase:

- 2010-15 contracts – Remploy, grant in aid funded, and seven prime providers funded through a service fees and payment by results model, with a ratio of 7 to 3 between elements.

- 2015-17 contract extension – Remploy commercialisation in April 2015, contract changes for seven prime providers introduced in October 2015. Funding was split equally between service fees and payment by results. The short duration outcome definition changed from ‘employment expected to last 13 weeks’ to ‘employment that has lasted 13 weeks’.

- 2017 contract extensions – contracts delivering in England and Wales extended to 2019 with the same funding model, but overall contract value reduced by around 20%. Referrals ended in February 2018. Participants were supported until March 2018, and outcomes could be claimed by providers until October 2019. Contracts delivering in Scotland took on no new participants but continued to support existing caseloads until October 2018.

Service delivery changes combined modules two and three into a single ‘In Work Support’ module. Prior to the 2017 contract extensions, Work Choice was European Social Fund (ESF) match funded[footnote 1].

1.6 Take up of Work Choice

Over 316,000 referrals to Work Choice were made between 2010 and 2018, and 245,700 starts were recorded from 194,800 participants.[footnote 2] 19% of participants started on Work Choice more than once, resulting in more starts than individual participants. On average there were 1.26 starts per participant.

In the first two months of the provision a large flow of transition WORKSTEP and Work Preparation participants migrated on to Work Choice. Following this there were on average 2,000 referrals per month across the remainder of provision.

1.7 Work Choice contractual performance

Commercial management of Work Choice was centred on minimum performance levels. These represented the minimum acceptable performance of each provider based on the number of individuals within any given cohort expected to achieve short-duration and longer-duration outcomes (see section 1.6 ‘Provider payment model’). Targets were agreed with providers and differed between providers. The overall expectation was that 39% of starts would result in a short-duration outcome, and 25% in a longer-duration outcome.

Performance fell below this expectation; 35% of Work Choice starts achieved a short-duration outcome and 23% achieved a longer-duration outcome. However, it is important to note that this is a measure of success against a commercial expectation, not a measure of the impact of the programme. To obtain an estimate of the impact on labour market outcomes, participants are compared to a counterfactual group of non-participants.

For further information on contractual outcomes achieved see the Work Choice statistics (Department for Work and Pensions, 2020).

1.8 Previous analysis of Work Choice

Two qualitative evaluations of Work Choice have been published. Thompson and others (2011) evaluated the transition process, the impact of transition on participants, and the early operation of Work Choice. Purvis and others (2013) examined factors which influenced access to the programme, participant profiles and the commissioning of Work Choice, and explored what works in specialist disability employment provision.

2. Evaluation methodology and sample selection

The impact of Work Choice is defined as the outcomes that participants achieved under Work Choice, minus the outcomes that would have occurred had they not participated.

The outcomes of Work Choice participants can be directly observed from data on benefit receipt held by DWP, and employment information from HM Revenue and Customs’ (HMRC) PAYE system. However, it is impossible to know what outcomes participants would have achieved if they had not participated (the counterfactual). To estimate impact, it is therefore necessary to form a credible estimate of what these outcomes would have been. Provided the approach to estimating counterfactual outcomes is sound, any difference between counterfactual estimates and observed participant outcomes can be attributed to the impact of the Work Choice.

The best method for estimating impacts is usually believed to be a randomised controlled trial (RCT) where a proportion of volunteers are assigned to a control group instead of the ‘treatment’ assessed (e.g. Work Choice). A well-constructed randomly assigned control group enables a robust counterfactual to be inferred, as the only difference between the treated individuals and the control group is the treatment.

Work Choice was not delivered with an RCT. Instead, a comparison group of non-participants is used to estimate the counterfactual. Outcomes for this group are compared to participants’ outcomes to estimate the impact of Work Choice.

A good comparison group of non-participants will be as similar as possible to the participant group, ideally with the only difference being participation in Work Choice. However, as described in ‘1.3 The routes to Work Choice participation’, Work Choice participation is the outcome of decisions made by the individual, the work coach/DEA and potentially the contracted provider. It is likely that individuals who participate will be, on average, different from those who do not. The ways in which these groups differ may include factors which influence the outcomes being measured. Indeed, we compared characteristics of participants and non-participants included in this analysis and found such differences (see 2.4 ‘Comparing participants and the comparison pool’). Differences between participant and non-participant groups introduce bias into the impact estimate when calculated as the difference between participant and non-participant outcomes.

Propensity score matching (PSM) is used to attempt to control for factors that influence whether someone participated in Work Choice. In PSM a comparison group is constructed by matching participants to similar individuals from a pool of non-participants. This PSM approach is consistent with the approach taken in a number of previous DWP impact assessments of labour market initiatives, for example for Work Experience (Haigh and Woods, 2016) and evaluations conducted by the DWP Employment Data Lab.

Under PSM propensity scores for participants and individuals in the comparison pool are calculated. These represent their likelihood of participating in Work Choice given a set of observed characteristics. Participants are then matched to non-participants with the same, or similar, propensity score to create the matched comparison group. Rosenbaum and Rubin (1983) showed that matching participants to non-participants with similar propensity scores can remove differences between these two groups in the variables included in the propensity score calculation.

The credibility of matching is dependent on the ‘Conditional Independence Assumption’ (CIA). That is, all important influences on participation and outcomes are controlled for, and we can assume that without Work Choice participation the participant and non-participant group would have had the same outcomes. If all important influences on participation and outcomes are included in the estimation of propensity scores, comparing the outcomes of participants and matched non-participants provides an unbiased estimate of programme impact. Any differences in outcomes between the groups can be attributed to Work Choice, and not compositional differences between groups.

However, some differences between participants and non-participants are not directly observable. Therefore, it is assumed that that by controlling for sufficient observed characteristics that the full range of factors, both observed and unobserved, that are likely to affect whether an individual participates in Work Choice can be controlled for.

To reduce the risk of residual, uncontrolled, bias we have restricted the comparison pool to those who were referred to Work Choice but did not start. These individuals should be more similar to participants than those never referred. Furthermore, DWP has rich and detailed data which can be linked to those referred to Work Choice (see ‘Appendix A: Data Sources’), improving the likelihood of satisfying the conditional independence assumption. See section ‘4 Caveats and limitations’ for further discussion of the CIA and potential sources of bias in this analysis.

Contractual changes were made to the provider payment model in 2015 (see ‘1.6 Provider payment model’). This may have affected the outcomes and impacts of Work Choice. The impact of Work Choice is therefore estimated separately for participants before (the ‘early cohort’) and after this change (the ‘later cohort’).

2.1 Outcomes measured

The impact of work choice on the following outcomes is analysed:

1. Payrolled employment:

a) Whether in payrolled employment (employment paid via the HMRC PAYE system)

b) Days spent in payrolled employment

To reflect that some people in work may also be in receipt of looking for work/low-income benefits the in payrolled employment outcome is further split into:

c) In payrolled employment and receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit

d) In payrolled employment and not receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit

2. Looking for work/low-income benefits:

a) Whether receiving looking for work/low-income benefits

b) Days spent receiving looking for work/low-income benefits

Further divided by:

c) JSA or UC with Searching for Work conditionality

d) Other looking for work/low-income benefits

Receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit indicates an individual is actively searching for work, and is defined as receiving one of the following:

- Jobseeker’s Allowance (JSA)

- Income Support (IS)

- Employment and Support Allowance (ESA)

- Incapacity Benefit (IB)

- Severe Disablement Allowance (SDA)

- Training Allowance (TA)

- Universal Credit (UC) excluding the ‘Working – No Requirements’ conditionality group (i.e., excluding individuals with individual or household earnings over the level at which mandatory work-related activities apply)

3. ‘Neither’ (not in payrolled employment nor receiving looking for work/low-income benefits)

a) Whether in the ‘neither’ outcome

b) Days spent in the ‘neither’ outcome

We do not know the status of people in the ‘neither’ outcome group. While it could include, among others, individuals moving into self-employment and not receiving looking for work/low-income benefits, or individuals still looking for work but with no access to looking for work/low-income benefits, it most likely captures individuals who have, by choice or otherwise, temporarily, or permanently, left the labour market.

2.1.1 Rollout of Universal Credit

Universal Credit is replacing six benefits, commonly referred to as ‘legacy benefits’:

- Income-based JSA

- Income-related ESA

- Income Support

- Working Tax Credit

- Child Tax Credit

- Housing Benefit

UC rollout began in 2013, initially in a small number of Jobcentres for eligible households in specific circumstances. By the end of 2018 UC was available to all eligible households across Great Britain. By April 2023 over 5.5 million people were receiving UC but there remained people receiving legacy benefits.

The analysis here spans the time from when only legacy benefits existed through to the UC rollout period to April 2023. This change in the benefits system and the gradual roll out of UC complicates the looking for work/low-income benefit outcome measure. The proportion of each group receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit may change over time simply due to UC rollout and the difference in eligibility rules between UC and legacy benefits.

The design of UC explicitly allows claimants to engage in employment activity whilst still being in receipt of the benefit, whereas JSA was designed to be an out of work benefit. UC claimants do not automatically move off UC when working over a certain number of hours as JSA claimants do. UC places claimants into conditionality groups which determine the amount and type of work-related activity that an individual is required to do to remain eligible for the benefit. Lower levels of conditionality mean fewer work-related requirements. In order of lowest to highest levels of conditionality, the groups are as follows:

- Working – no requirements

- No work requirements

- Planning for work

- Preparing for work

- Working – with requirements

- Searching for work

UC conditionality groups do not map directly on to legacy benefit types. For the purposes of this analysis, the following approximations have been made:

- Jobseeker’s Allowance to Universal Credit searching for work.

- All other legacy looking for work/low-income benefits to; Universal Credit planning for work, preparing for work, working – with requirements, and no work requirements.

The impact of Work Choice is estimated on the above two groups of benefits in addition to the overall impact on looking for work/low-income benefits.

2.2 Participant selection

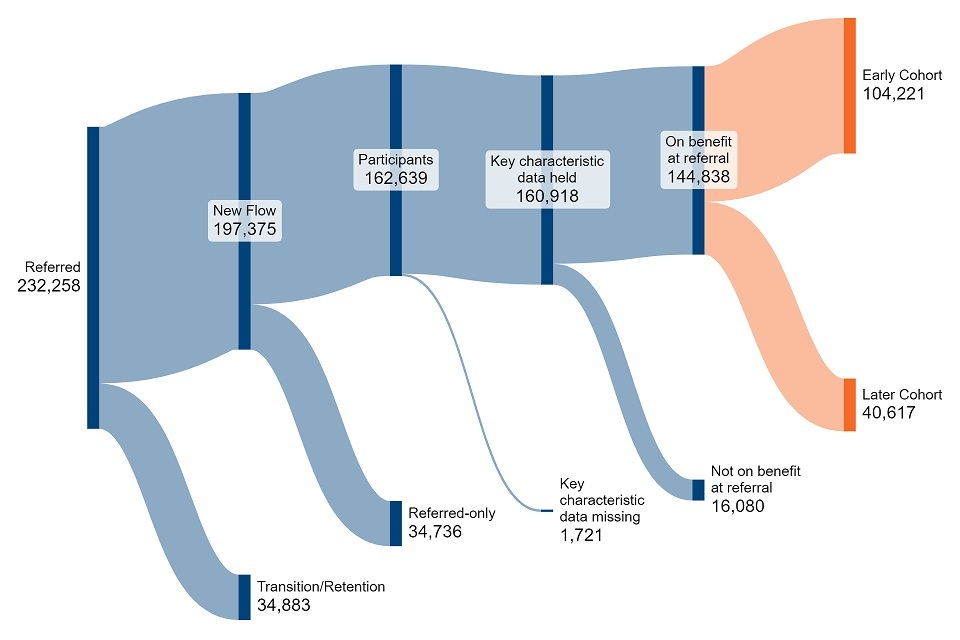

Referrals to Work Choice were identified using the DWP Provider Referral and Payments (PRaP) dataset, which captures all referrals to contracted provision. 232,258 referred individuals were identified. 197,375 (85%) of these were from the new flow group. Of these 162,639 started Work Choice.

New flow group participants who met both the following criteria were included in this analysis:

- Have a record on DWP’s Labour Market System (LMS), the main course of personal characteristics data used in this analysis (see ‘Appendix A: Data Sources’)

- Were receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit at the point of referral

1,721 participants (1.1%) were excluded because they did not have a record on the LMS. A further 16,080 participants (9.9%) were excluded because they were not receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit at the point of referral.

The resulting group of 144,838 participants was then split into an ‘early cohort’; those referred under the 2010 contract terms, and a ‘later cohort’; those referred under the 2015 or 2017 contract extension terms. The early participant cohort has 104,221 individuals referred between October 2010 and October 2015. The later participant cohort has 40,617 individuals referred between April 2015 and February 2018.[footnote 3]

Where participants had multiple referrals, the earliest referral leading to a start was selected for inclusion in the analysis and used as the date from which to track outcomes. 6.9% (7,191) of early cohort participants and 8.8% (3,584) of later cohort participants had at least one prior referral that did not result in Work Choice participation.[footnote 4]

Figure 2‑1 illustrates the exclusion of individuals from the pool of all referred individuals to form the two participant cohorts included in this analysis.

Figure 2‑1: Selection of participant cohorts from all referred individuals.

2.3 Selection of a referred-only group

The comparison pool comprised individuals who had been referred to Work Choice but did not start. People in this group have undergone the same selection into referral as people who ultimately participated in Work Choice. They were eligible for Work Choice, volunteered, and a work coach or DEA agreed that they were a suitable candidate. People in this referred-only group should be more like Work Choice participants than people never referred. For this reason, they were chosen as the preferred comparison group (for more information on the consideration of a never referred comparison group see ‘Appendix F: A never referred comparison group’).

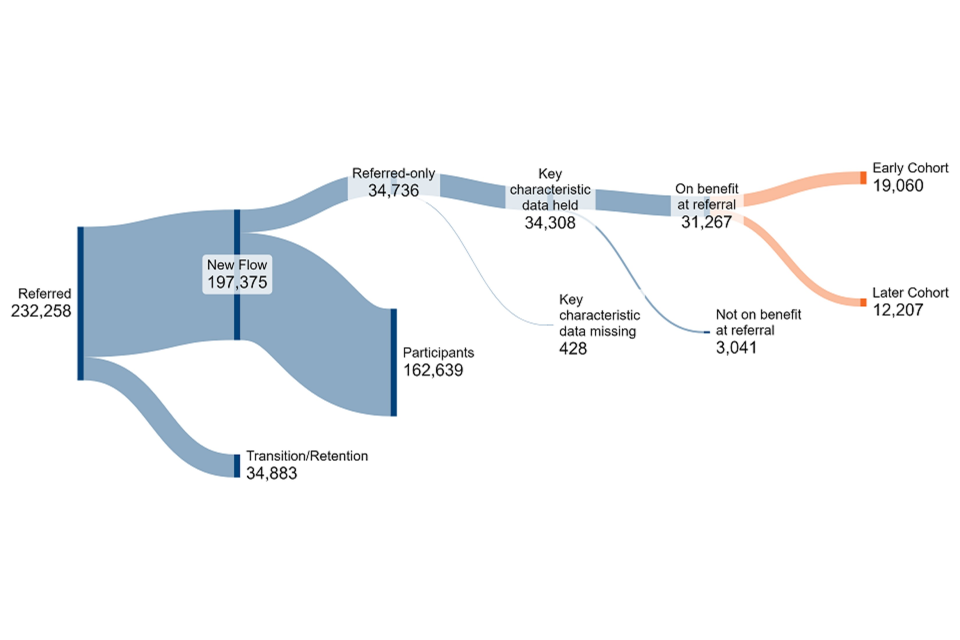

As for the participant group, referrals to the new flow group were identified using the DWP Provider Referral and Payments (PRaP) dataset. Of the 197,375 individuals referred from the new flow group 34,736 individuals did not start Work Choice.

The same criteria as used for selecting the participant group was then used to select referred-only individuals to be included in the comparison pool i.e.:

- Have a record on the LMS

- Were receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit at the point of referral

This resulted in similar proportions being excluded: 428 (1.2%) were excluded because they did not have a record on the LMS, and a further 3,041 referrals (8.8%) were excluded because the individuals were not receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit at the point of referral.

This resulting group of 31,267 referred-only individuals was then split into an ‘early’ and a ‘later’ cohort. The early cohort has 19,060 referred-only individuals and the later cohort has 12,207 referred-only individuals.

Where individuals had multiple referrals, the earliest referral was selected for inclusion in the analysis and used as the date from which to track outcomes. 14.1% of the early referred-only cohort (2,685 individuals) and 9.8% of the later referred-only cohort (1,197 individuals) had multiple referrals.

Figure 2‑2 illustrates the exclusion of individuals from the pool of all referred individuals to form the two referred-only cohorts included in this analysis.

Figure 2‑2: Selection of referred-only cohorts from all referred individuals.

2.4 Comparing participants and the comparison pool

Together the participant cohorts and referred-only cohorts include 176,105 individuals referred to Work Choice between October 2010 and February 2018. This represents 76% of all individuals referred to Work Choice and 89% of individuals referred to the new flow group.

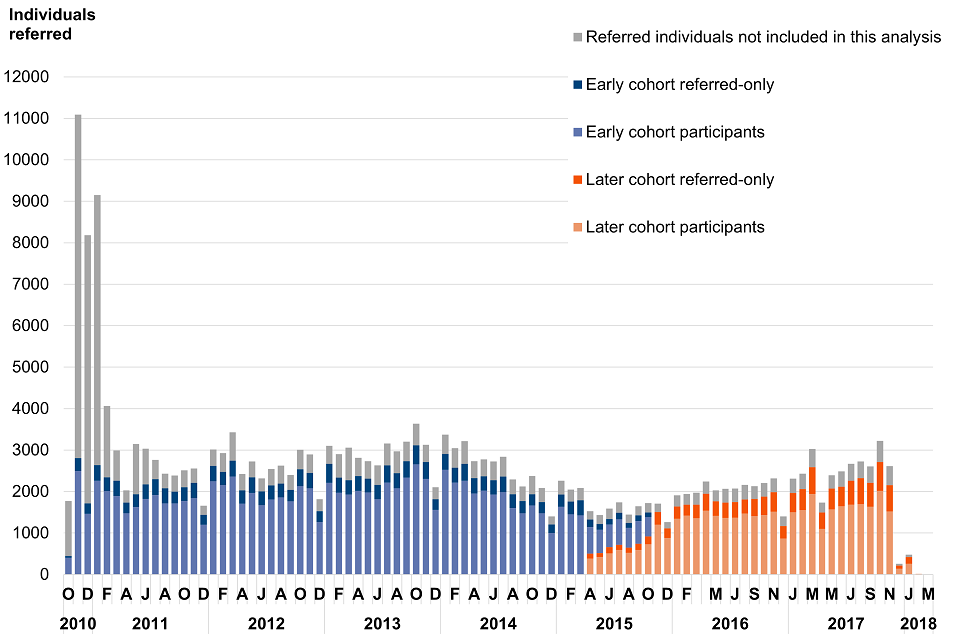

Figure 2‑3 shows the number of individuals referred, and the subset in the participant and referred-only cohorts, across time. The large spike in referrals at the beginning of the programme is due to transition cases. Transition and retention participants are not included in this analysis. Early and later cohorts overlap because contract changes came into effect at different times for different providers.

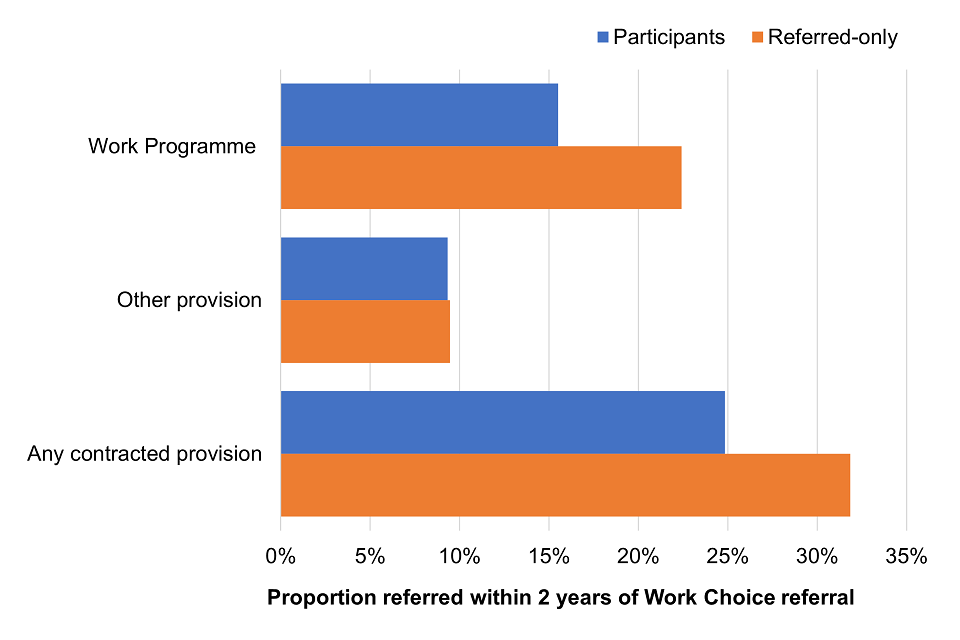

Figure 2‑4 shows the different pathways taken by the participant and referred-only groups. We do not know why referred-only individuals did not start Work Choice. Some potential participants were rejected by providers as they felt the potential participants lacked motivation or were unlikely to move into work quickly (Purvis and others, 2013). This suggests that the referred-only group could be less likely to move into work and/or have higher support needs than those who started Work Choice. This could lead to overestimating the impact of Work Choice. Alternatively, some non-starts, including all exits before the first provider meeting, were customer choice. Customers may have found work or felt that they did not need Work Choice support. This could lead to underestimating the impact of Work Choice.

Figure 2‑3: Individuals referred to Work Choice by referral month. Where individuals are referred more than once only their earliest referral that led to a start on Work Choice, or their earliest referral if they never started, is counted.

The characteristics of the participant and unmatched referred-only group are compared in Table 2‑1 and Table 2‑2. Table 2‑1 shows what proportion of the groups were receiving each looking for work/low-income at referral. For both cohorts, most participants were receiving JSA, with the referred-only group slightly less likely to be receiving it than participants. Similar proportions of both cohorts were in receipt of ESA at referral to Work Choice, with the referred-only group more likely to be receiving ESA than participants. Due to the gradual roll-out of UC (see ‘2.1.1 Rollout of Universal Credit’), only a few people in the early cohorts were receiving UC at the point of referral. However, 17% of the later cohort participants and 16% of the later cohort referred-only group were in receipt of UC at referral, with lower proportions receiving JSA.

Figure 2‑4: Work Choice referral process and group allocation for analysis

Table 2‑2 summarises key characteristics and the employment history of the participant group and the unmatched referred-only group (see ‘Appendix C: Post matching balance assessment’ for a larger list, and ‘Appendix A: Data Sources’ for descriptions of the data sources).

Although there are many similarities between the early and later cohorts, there are some differences. For example, the early cohort is younger, has spent fewer days in payrolled employment over the two years before referral, and is more likely to have been referred to the Work Programme prior to referral to Work Choice.

Table 2‑1: Looking for work/low-income benefit received at the point of referral to work choice for unmatched participants and referred-only groups.

| Looking for work/low-income benefit received at referral | Early cohort participant | Early cohort referred-only | Later cohort participant | Later cohort referred-only |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jobseeker’s Allowance (JSA) | 79.5% | 74.8% | 65.2% | 63.0% |

| Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) | 16.2% | 20.8% | 16.8% | 19.9% |

| Universal Credit excluding ‘Working – No Requirements’ (UC) | 0.2% | 0.3% | 16.9% | 16.1% |

| Income Support (IS) only | 1.0% | 1.1% | 1.1% | 1.0% |

| Incapacity Benefit (IB) only | 1.8% | 1.7% | 0.1% | 0.0% |

| IS and IB together | 1.2% | 1.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Severe Disablement Allowance (SDA) | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Training Allowance (TA) | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

Table 2‑2: Characteristics of individuals in the un-matched participant and referred-only groups.

| Variable | Early participant group | Early referred-only group | Later participant group | Later referred-only group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aged 18 to 24 | 25.2% | 24.4% | 17.8% | 16.5% |

| Aged 25 to 49 | 51.4% | 52.3% | 51.3% | 52.0% |

| Aged 50+ | 23.4% | 23.3% | 30.8% | 31.5% |

| Male | 64.7% | 64.0% | 63.1% | 63.3% |

| Ethnicity - White | 86.2% | 83.3% | 84.5% | 82.8% |

| Ethnicity - Black | 3.3% | 4.3% | 4.3% | 4.9% |

| Ethnicity - Asian | 3.1% | 4.1% | 3.8% | 4.4% |

| Ethnicity - Mixed | 1.2% | 1.3% | 1.4% | 1.6% |

| Ethnicity - Other | 1.0% | 1.8% | 1.1% | 1.5% |

| Ethnicity - Prefer Not to Say | 5.2% | 5.1% | 4.6% | 4.5% |

| Disability: Conditions Restricting Mobility / Dexterity | 15.0% | 15.3% | 15.9% | 16.9% |

| Disability: Visual Impairment | 2.3% | 2.5% | 1.9% | 1.8% |

| Disability: Hearing and / or Speech Impairment | 3.9% | 3.4% | 2.9% | 2.3% |

| Disability: Long-term Medical Conditions | 11.1% | 11.8% | 12.4% | 12.5% |

| Disability: Moderate to Severe Learning Disability | 6.4% | 6.4% | 4.0% | 4.3% |

| Disability: Mild Learning Disability | 13.6% | 11.6% | 9.5% | 7.5% |

| Disability: Severe Mental Illness | 1.0% | 1.3% | 1.0% | 1.3% |

| Disability: Mild to Moderate Mental Health condition | 18.9% | 20.8% | 17.6% | 18.2% |

| Disability: Neurological Conditions | 4.0% | 4.2% | 3.1% | 3.0% |

| Disability: Multiple Conditions | 12.0% | 12.3% | 13.5% | 13.8% |

| Referred to Work Programme at any time prior to Work Choice referral | 10.8% | 11.7% | 38.5% | 41.9% |

| Referral to any contracted employment support in the two years prior to referral | 21.8% | 16.6% | 18.8% | 11.7% |

| Adverse sanction decision in the two years before referral | 22% | 26% | 17% | 19% |

| Days in P45 employment over the two years prior to referral | 182.2 | 135.8 | 191.9 | 144.0 |

| Days receiving JSA or UC with Searching for Work conditionality over the two years prior to referral | 240.7 | 227.7 | 261.7 | 254.4 |

| Days receiving other looking for work/low-income benefits over the two years prior to referral | 231.1 | 283.2 | 220.8 | 276.8 |

| Days receiving any looking for work/low-income benefits over the two years prior to referral | 471.8 | 510.9 | 482.5 | 531.1 |

For both the early and late cohort, Work Choice participants were more likely to have been referred to other contracted employment support prior to referral to Work Choice. They were also less likely to have received a benefit sanction in the two years prior to referral. Such differences may be correlated with a difference in motivation to find employment and, therefore, outcomes.

For both cohorts Work Choice participants had, on average, spent more days in payrolled employment, and fewer days receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit (although more days in receipt of JSA/UC with searching work conditionality), in the two years before referral to Work Choice than those referred only. A difference in employment history may lead to a difference in outcomes. There were also differences in ethnicity and disability type between the participant and referral-only groups. Demographic differences such as these may also be correlated with different outcomes.

The aim of matching is to control differences between the participant and referral-only groups as much as possible using observed characteristics.

2.5 Estimating propensity scores

The propensity score is the probability of starting Work Choice given a set of observed characteristics. Observed factors that influence either participation in Work Choice or the outcomes achieved were included as variables when calculating propensity scores. ‘Appendix B: Variables used in propensity score matching’ shows the complete list of variables chosen from available DWP and HMRC datasets. These included:

- Individual characteristics (e.g., age and sex)

- Family circumstances (e.g., parental status)

- Payrolled employment history in the two years prior to referral, including the total number of days spent in employment and weekly payrolled employment flags.

- Benefit history in the two years prior to the claim start, including the total number of weeks spent receiving specific benefits, and weekly flags indicating receipt of looking for work/low-income benefits.

- Benefit sanctions history in the two years prior to referral

- History of employment programme participation in the two years prior to referral

- Geography

- Disability type

- Occupation sought (Standard Occupational Classification (SOC))

- Provider level variables that may influence participation:

- proportion of referrals to provider that did not result in a provider meeting

- proportion of referrals to provider that resulted in a provider meeting but not a start

- the average time between referral to the provider and participant start

- Local unemployment rate one year before referral

- Timing of referral to Work Choice

Propensity scores were estimated using logistic regression with the set of observed characteristics as independent variables.

2.6 Matching

Within each cohort participants were matched to the individual in the comparison group with the closest propensity score within a specified range (the caliper). This is ‘nearest neighbour’ matching. The inclusion of a caliper prevents poor matches where there is a large difference between a participant’s propensity score and the closest propensity score in the comparison group. The caliper was set at 0.1 standard deviations of the propensity scores.

The referred-only group is smaller than the Work Choice participant group. Matching with replacement was therefore required so that every participant could potentially be matched to an individual from the referred-only group. This means that individuals from the referred-only group could be matched to multiple individuals in the participant group.

See ‘Appendix D: Sensitivity checks’ for assessment of the sensitivity of impact estimates to different matching methods.

2.7 Assessing the quality of the match

2.7.1 Common support

Before estimating impacts, it is important to check the overlap in the range of propensity scores for each group (the ‘common support’). For a participant to be matched, and therefore included in the analysis, there must be an individual in the comparison pool with the same or similar propensity score. The results of this evaluation are only valid for these ‘on support’ participants. Participants that cannot be matched are excluded from the analysis. The more participants that are excluded the less representative impact estimates become.

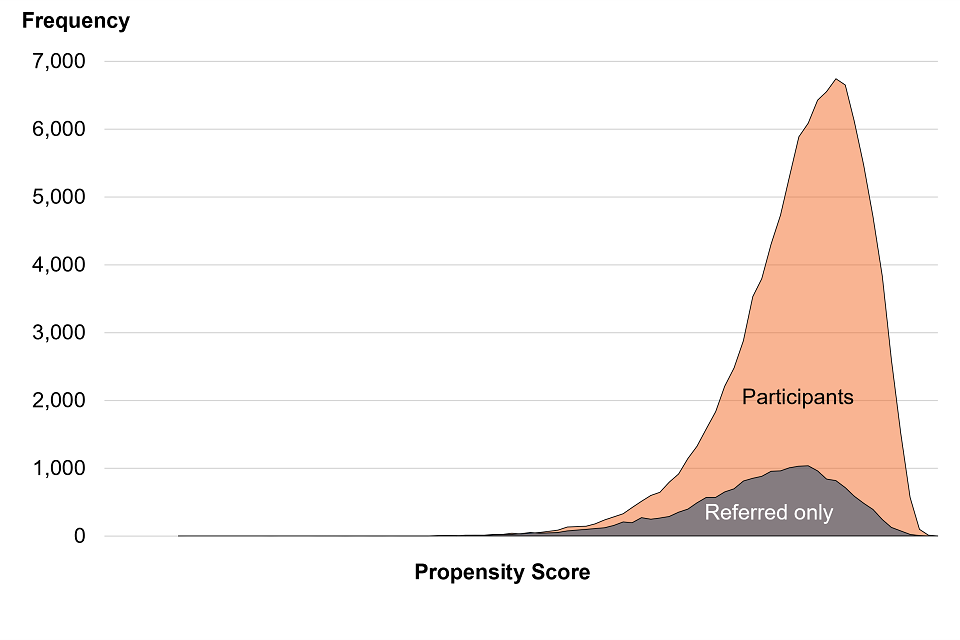

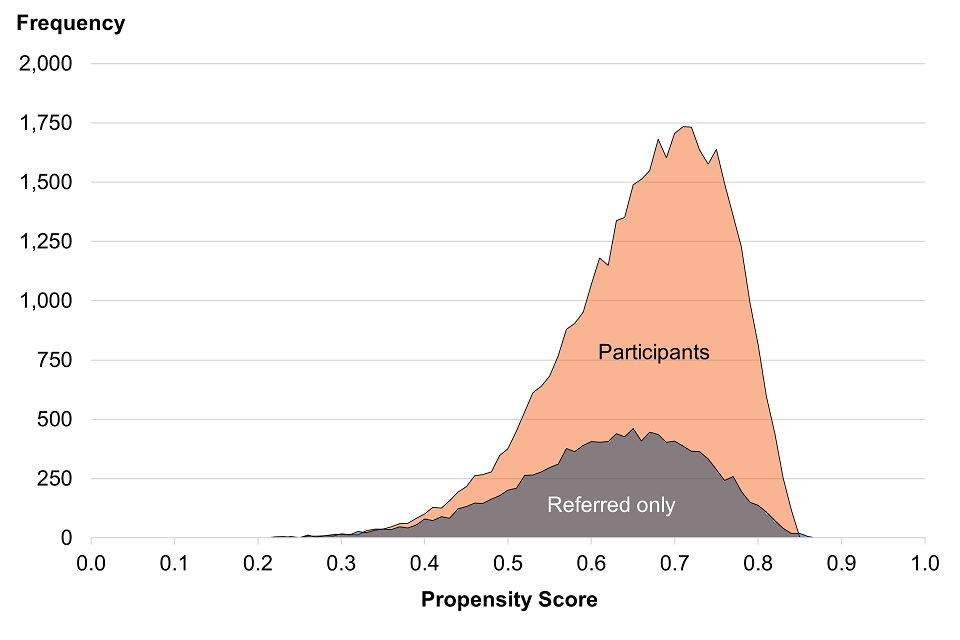

For both the early and late cohort there was extensive overlap between the propensity scores for Work Choice participants and scores for the referred-only group (Figure 2‑5). For the early cohort 99.9% of the participant group was ‘on support’; following matching only seven of the participants (<0.1%) remained unmatched and were excluded from the analysis (Table 2‑3). For the later cohort 99.98% of the participant group was ‘on support’; following matching only four of participants (<0.1%) remained unmatched and were excluded from the analysis (Table 2‑4).

On average individuals in the early cohort referred-only group were matched to six participants. The maximum number of participants an individual in the referred-only group was matched to was 73 (Table 2‑3). In the later cohort, on average, individuals in the referred-only group were matched to four participants. The maximum number of participants an individual in the referred-only group was matched to was 74 (Table 2‑4).

Figure 2‑5: Propensity scores for work choice participants and the unmatched referred-only group for a) the early cohort, and b) the later cohort.

a.

b.

Table 2‑3: The size of the early cohort participant and referred-only groups before and after matching.

| Matching group | Size before matching | Size after matching | Max replacement | Mean replacement | Proportion on support |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant | 104, 221 | 104, 217 | N/A | N/A | >99.99% |

| Referred-only | 19,060 | 16,964 | 73 | 6 | N/A |

Table 2‑4: The size of the later cohort participant and referred-only groups before and after matching.

| Matching group | Size before matching | Size after matching | Max replacement | Mean replacement | Proportion on support |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant | 40,617 | 40,609 | N/A | N/A | 99.98% |

| Referred-only | 12, 207 | 9,740 | 74 | 4 | N/A |

2.7.2 Variable balance

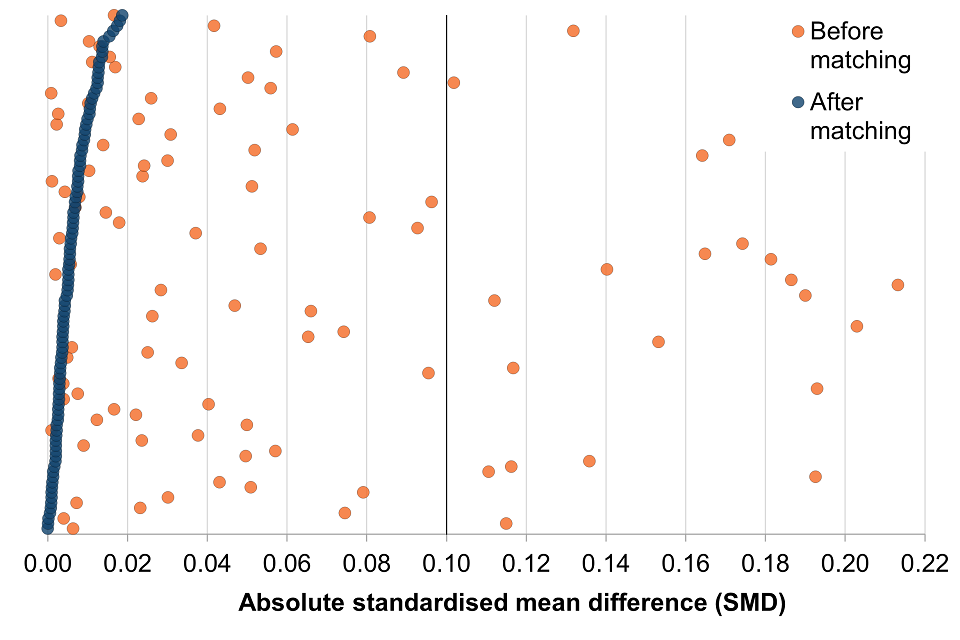

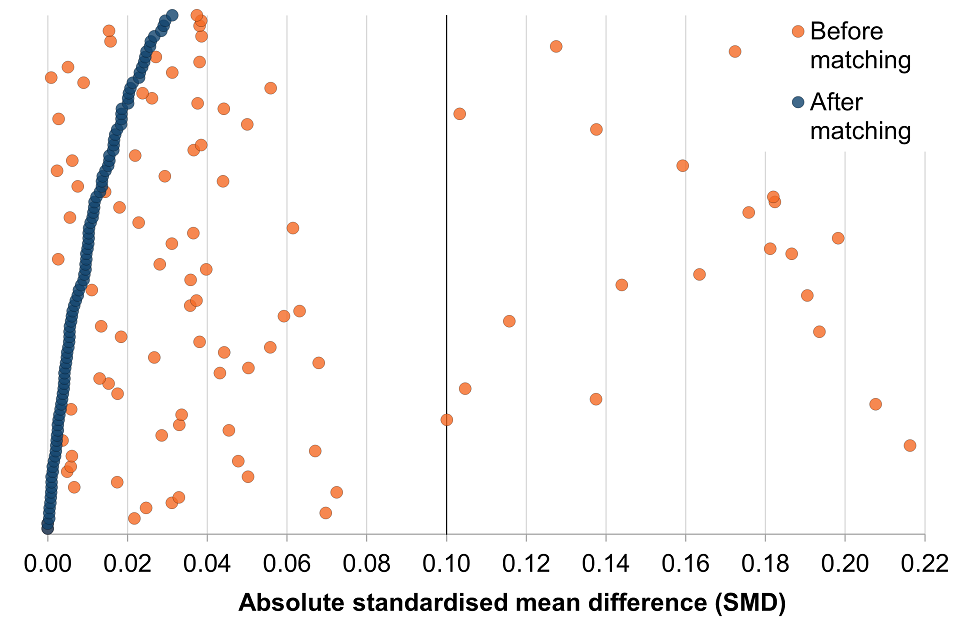

After matching, the characteristics of the matched comparison group should be similar to, or ‘balanced’ with, those of the matched participant group. If there are differences between the groups, impact estimates may not be reliable. Characteristics are compared using standardised mean differences (SMD): the difference between the means of the participant and matched comparison group divided by the square root of the mean sample variance. An SMD of zero indicates no difference between groups. An absolute SMD of below 0.1 is commonly used to indicate a good balance between groups. The absolute SMD was calculated for all variables included in the propensity score calculation.

Figure 2‑6 shows the absolute SMD before and after matching for all matching variables except the weekly payrolled employment/benefit receipt/neither flags (see ‘Appendix B: Variables used in propensity score matching’). Before matching, 22 variables had an absolute SMD of 0.1 or greater for the early cohort, and 23 variables for the later cohort. After matching the mean values are much closer and no observed characteristics for either cohort had an absolute SMD of 0.1 or greater. For both cohorts, all weekly flag variables had an absolute SMD of 0 before and after matching.

Figure 2‑6: Absolute standardised mean differences for observed characteristics between the participant and referred-only groups for a) the early cohort, and b) the later cohort

a.

b.

Table 8‑1 and Table 8‑2 in ‘Appendix C: Post matching balance assessment’ provide more detail on variable balance. Before matching the differences between the values of variables show that the participant and referred-only groups were not well matched. For example, prior to matching, participants spent, on average, more days in payrolled employment over the two years before referral than the referred-only group (46 more days for the early cohort and 48 more days for the later cohort). After matching the difference between the participant group and matched referral-only group is less than two days for both cohorts.

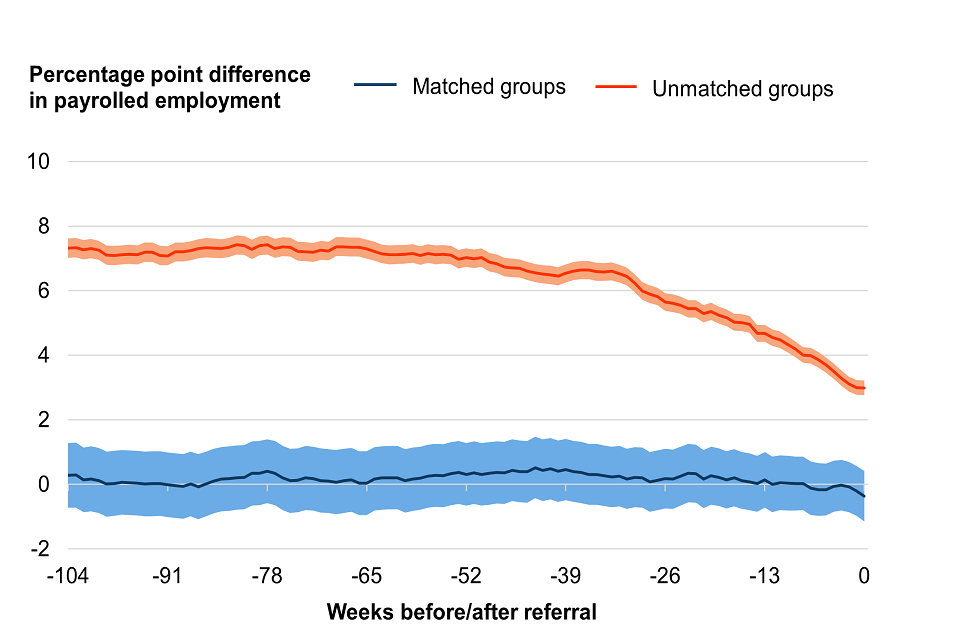

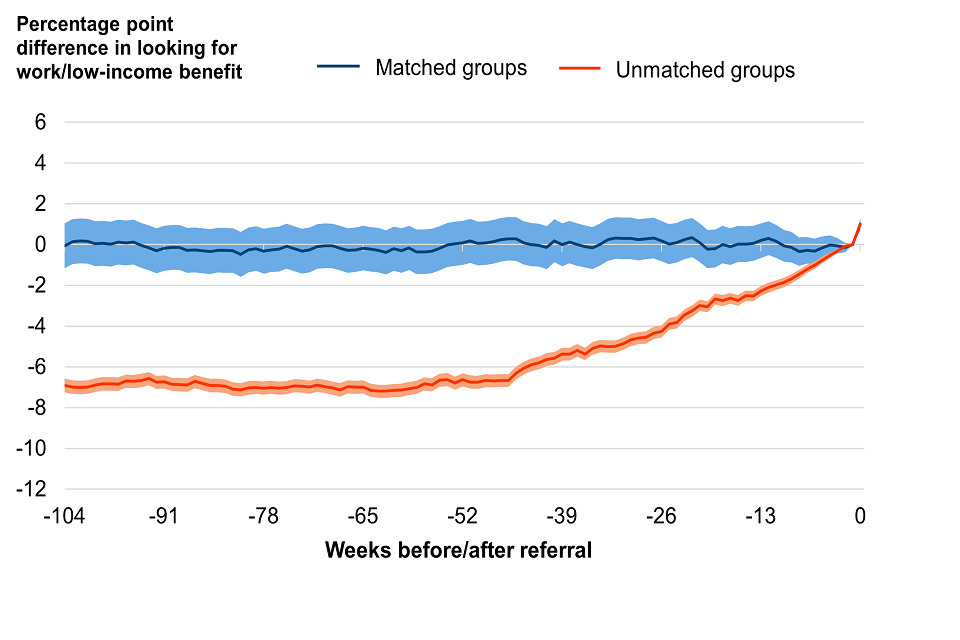

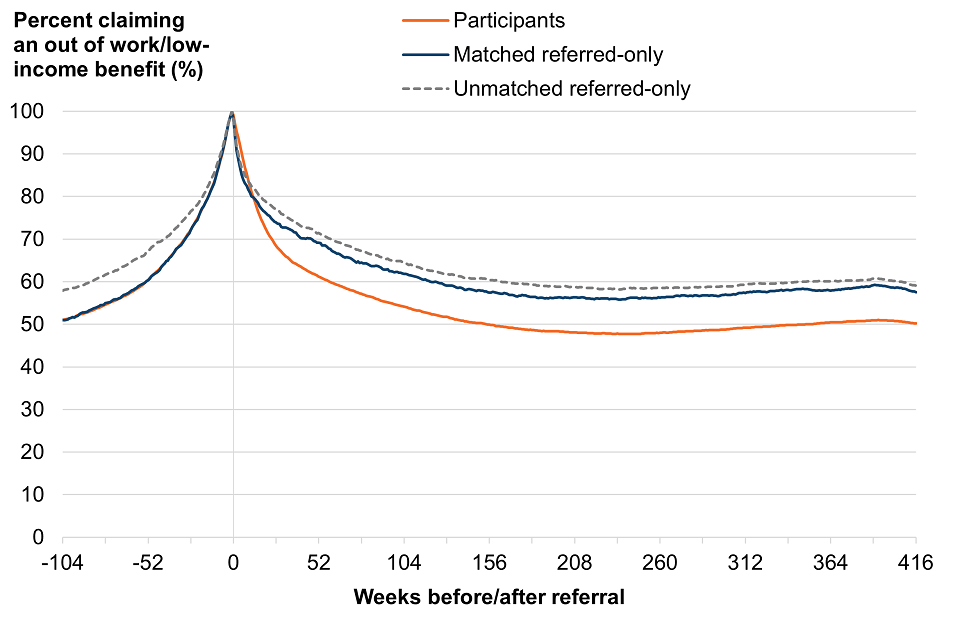

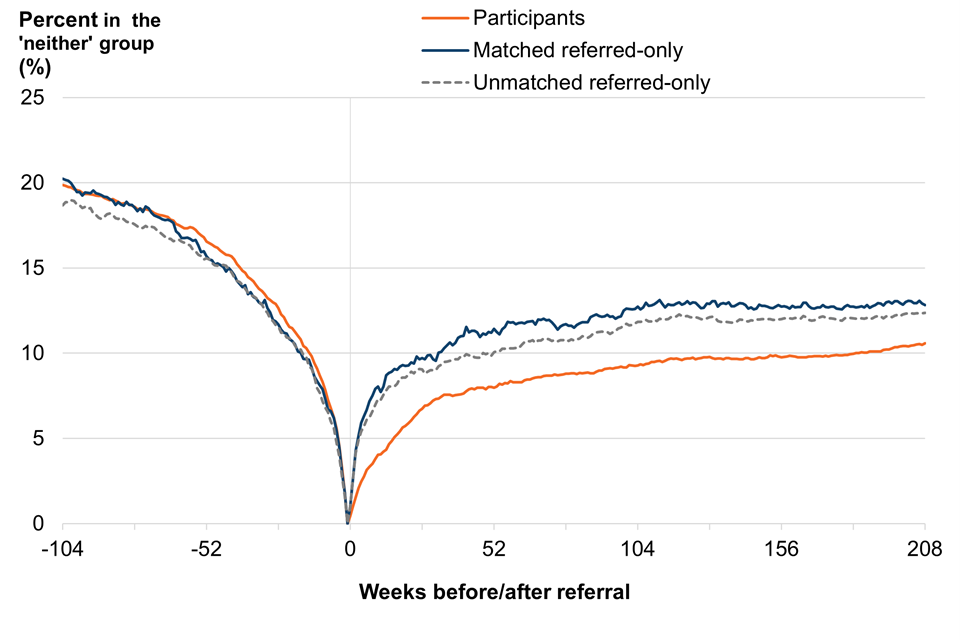

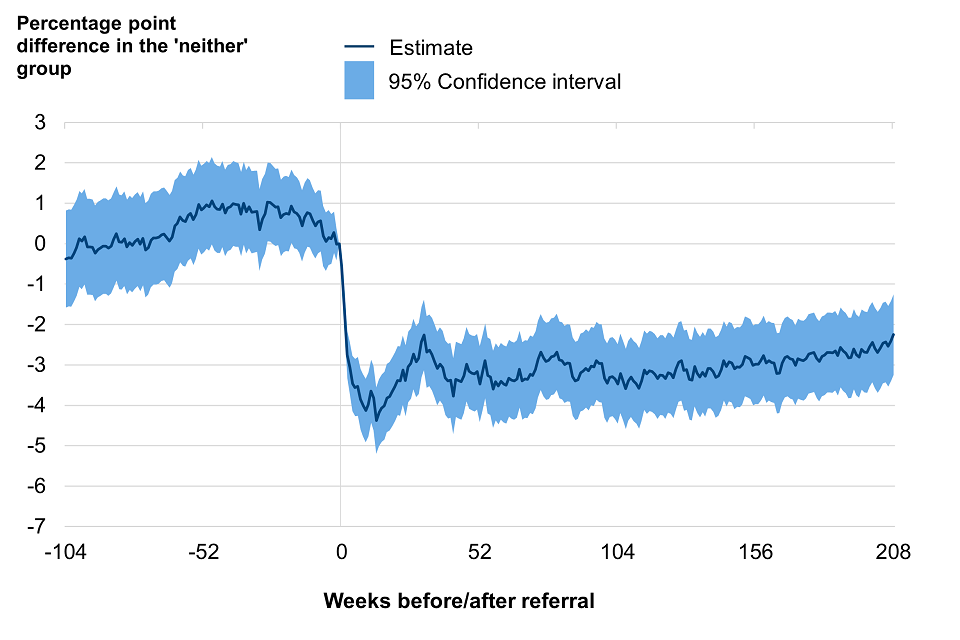

Figure 2‑7 shows that matching has minimised the difference in employment history between the participant and referred-only groups. Before matching the pre-referral employment rate of Work Choice participants is higher than that of the referred-only group. After matching the matched referred-only group has a similar pre-referral employment rate to the participant group. For all weeks pre-referral the confidence interval of the difference in the payrolled employment rate between matched groups includes zero.

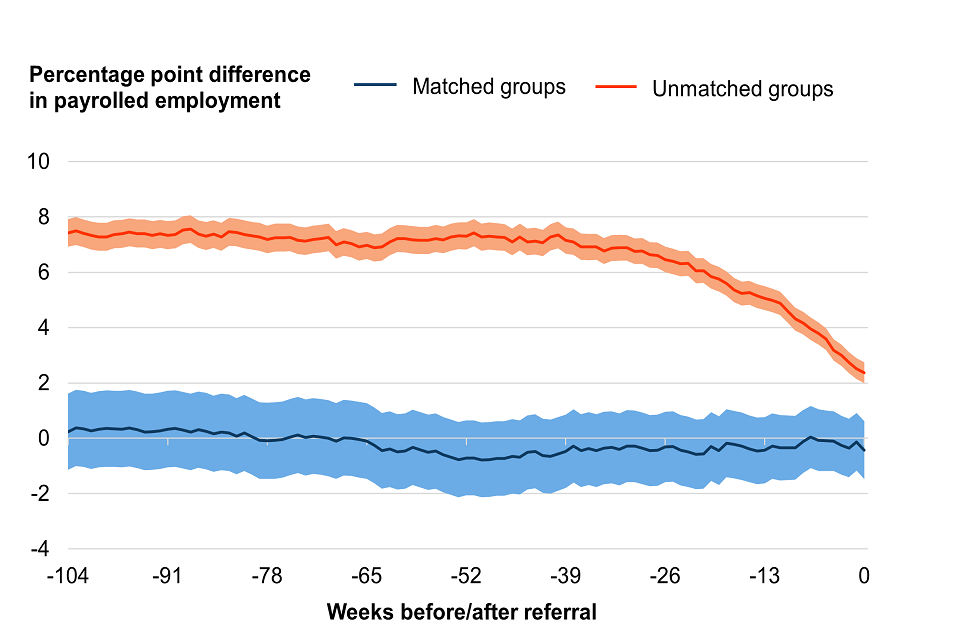

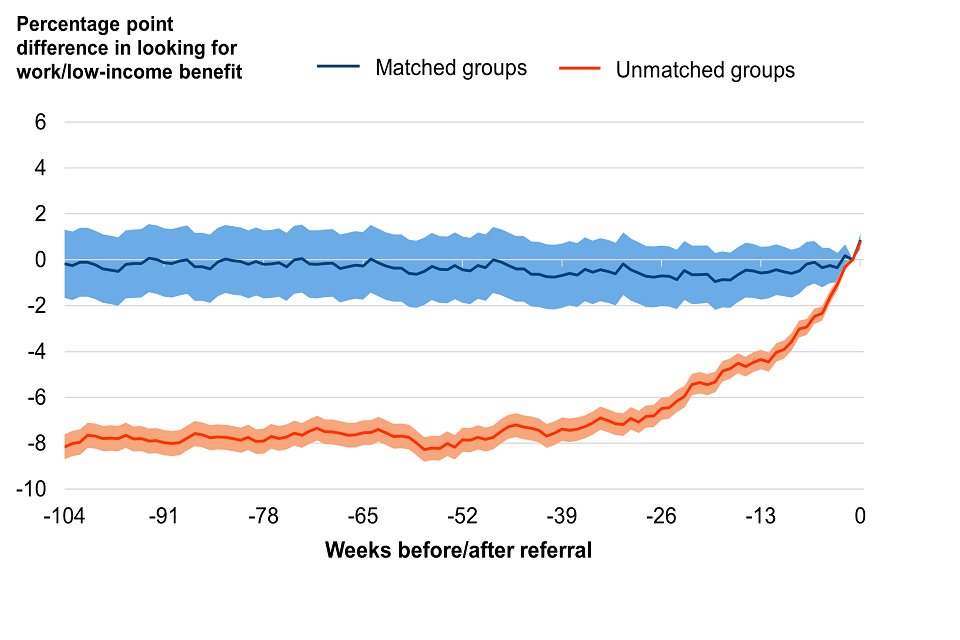

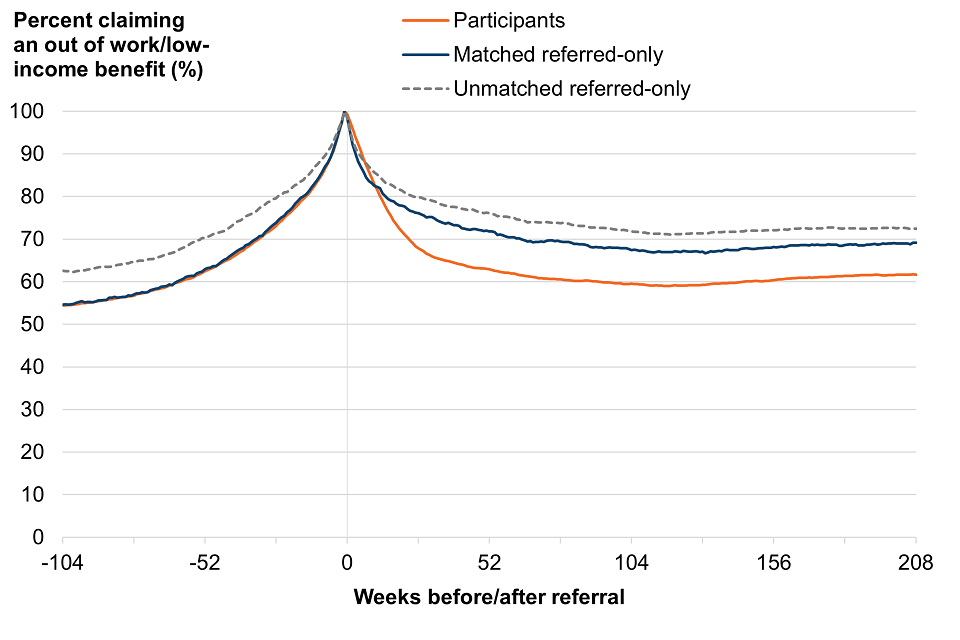

Figure 2‑8 shows that matching has also minimised the difference in looking for work/low-income benefits history between the participant and referred-only groups. Before matching the proportion of Work Choice participants receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit pre-referral was lower than that of the referred-only group. After matching the matched referred-only group had a similar proportion of people receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit pre-referral as the participant group. For all weeks pre-referral the confidence interval of the difference in looking for work/low-income benefit receipt between matched groups includes zero.

Whilst we can assess the balance of observed factors that influence participation in Work Choice and labour market outcomes, we cannot know if we have successfully matched unobserved factors such as motivation. Relevant differences between the later cohort participant and referred-only groups may therefore remain.

Figure 2‑7: The difference between the payrolled employment rate of participants and the referred-only group, before and after matching, by weeks before referral for a) the early cohort, and b) the later cohort.

a.

b.

Figure 2‑8: The difference between the percentage of participants and the percentage of the referred-only group receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit, before and after matching, by weeks before referral for a) the early cohort, and b) the later cohort.

a.

b.

2.8 Estimating impact

For each week post-referral, the proportion of individuals in each outcome state was calculated for both the matched participant and matched referred-only groups. The outcomes of the referred-only group represent the outcomes that participants would have achieved without Work Choice participation. To estimate the impact of Work Choice these outcomes are subtracted from the outcomes of the participant group.

3. Impact on employment and benefits

Estimates of impact are presented along with values showing the upper and lower confidence limits around the impact. These values define the range that 95% of the time you would expect the estimate to fall within if the evaluation were to be repeated (the 95% confidence interval (CI)).

Estimates relate specifically to the impact of Work Choice on new flow participants included in this analysis and may not be generalisable to other Work Choice participants. Furthermore, the impact of Work Choice may be affected by the wider context in which the programme operated including the labour market conditions, wider economy, DWP benefit regime, and other support available.

Caution should be taken when interpreting and using these results. The validity of the technique used in this report rests on the assumption that all the characteristics linked to a person’s participation in the programme and the outcomes of interest have been sufficiently accounted for in the analysis, either explicitly or otherwise. We carefully considered such characteristics and included variables to control for these. However, this assumption cannot be tested and depends on the data available and on the nature of the programme and its participants. Therefore, we are less confident that the results are an unbiased estimate of impact than would be the case with a well-designed and well-implemented randomised controlled trial.

3.1 The impact of Work Choice on payrolled employment

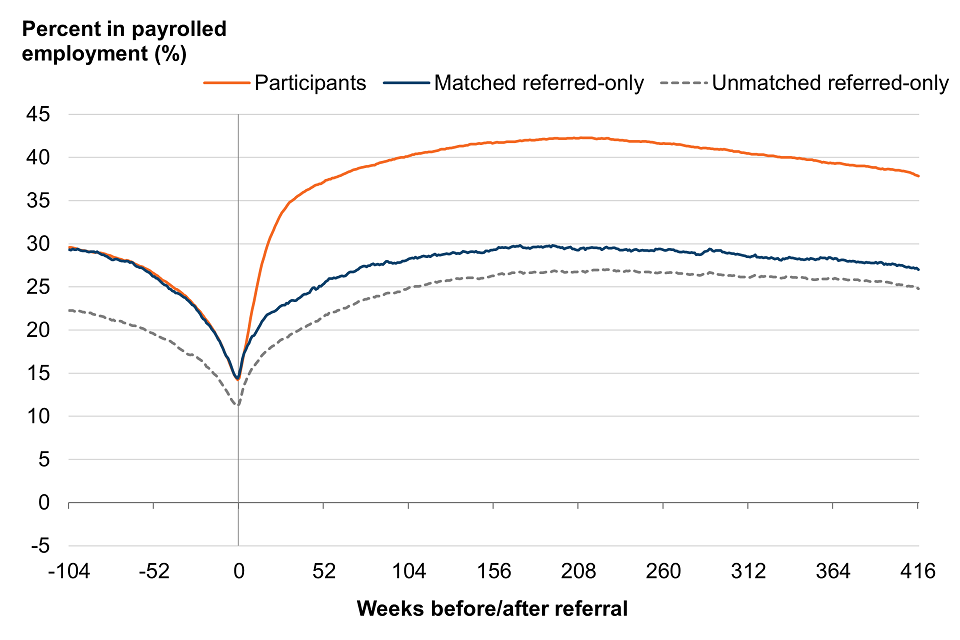

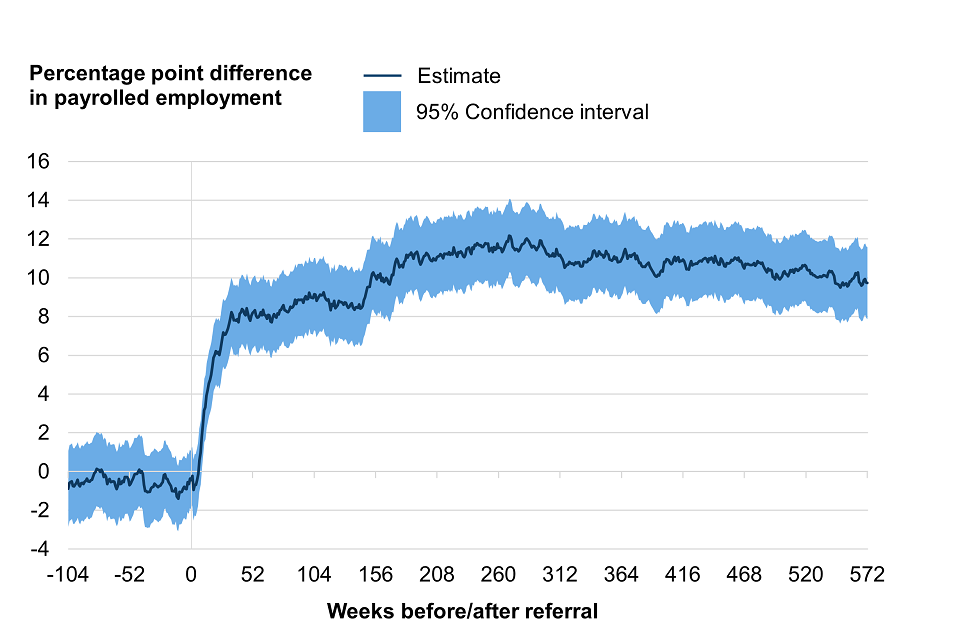

Following referral to Work Choice the payrolled employment rate of both the participants and referred-only individuals increased for both cohorts (Figure 3‑1 and Figure 3‑2). This increase was greater for Work Choice participants than the referred-only group.

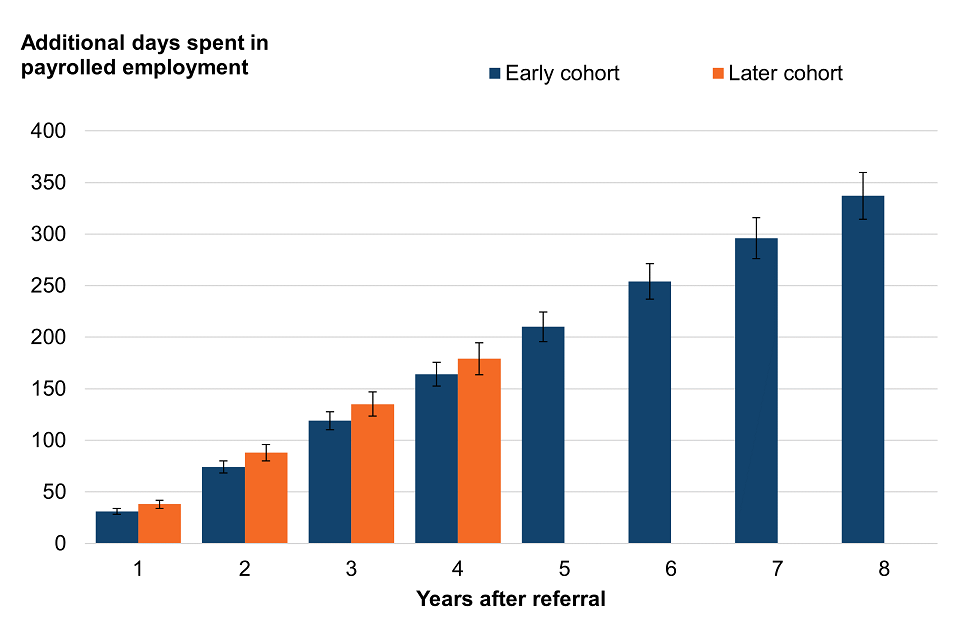

52 weeks after referral, early cohort participants were 11.8 percentage points (CI: 10.8 to 12.8) more likely to be in payrolled employment than the referred-only group (37.2% vs. 25.4%, Figure 3‑1 b). This increased likelihood of employment slowly declined over the remainder of the tracking period, but after 416 weeks Work Choice participants were still 10.9 percentage points (CI: 9.9 to 11.8) more likely to be in employment than the matched comparison group (37.9% vs 27.0%, Figure 3‑1 b). On average participants spent 337 more days (CI: 314 to 359) in payrolled employment (11.5 percentage points, CI: 10.8 to 12.3) over that time.

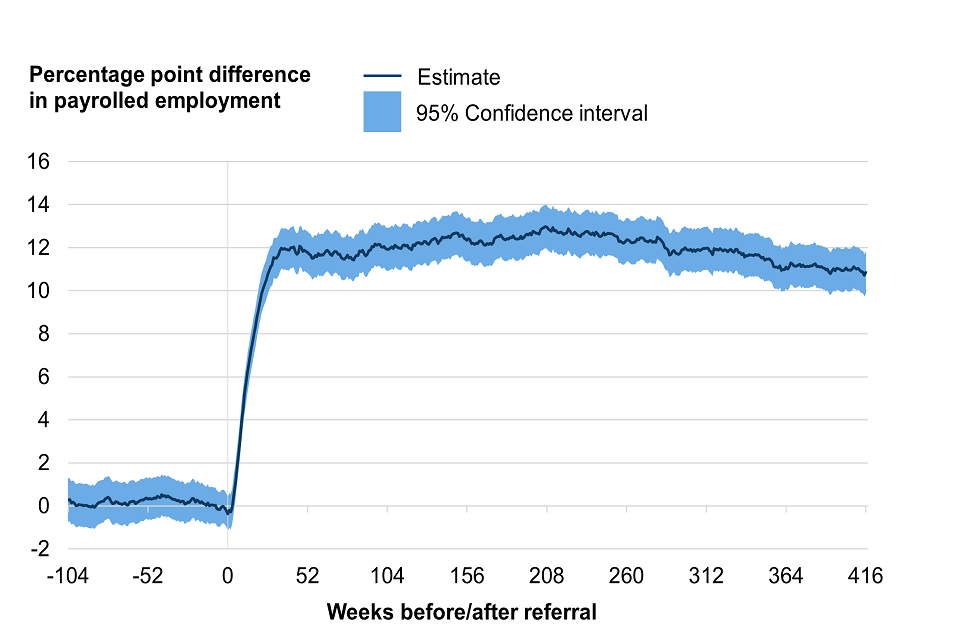

52 weeks after referral to Work Choice, later cohort participants were 13.7 percentage points (CI: 12.3 to 15.0) more likely to be in payrolled employment than the referred-only group (39.3% vs 25.6% Figure 3‑2 b). As for the early cohort this impact slightly declined over the remainder of the tracking period, but after 208 weeks Work Choice participants were still 11.4 percentage points (CI: 10.1 to 12.7) more likely to be in employment than the matched comparison group (38.1% vs 26.7% Figure 3‑2 b). On average participants spent 179 (CI: 163 to 194) more days in payrolled employment (12.3 percentage points, CI: 11.2 to 13.3) over that time.

Figure 3‑1: a) The percentage of the early cohort participant and matched referred-only group in payrolled employment by weeks after referral. b) The difference between the payrolled employment rate of the early cohort participants and matched referred-only group by week after referral. This difference is the impact of Work Choice.

a.

b.

Figure 3‑2: a) The percentage of the later cohort participants and referred-only comparison group in payrolled employment by weeks after referral. b) The difference between the payrolled employment rate of the later cohort participants and matched referred-only group by week after referral. This difference is the impact of Work Choice.

a.

b.

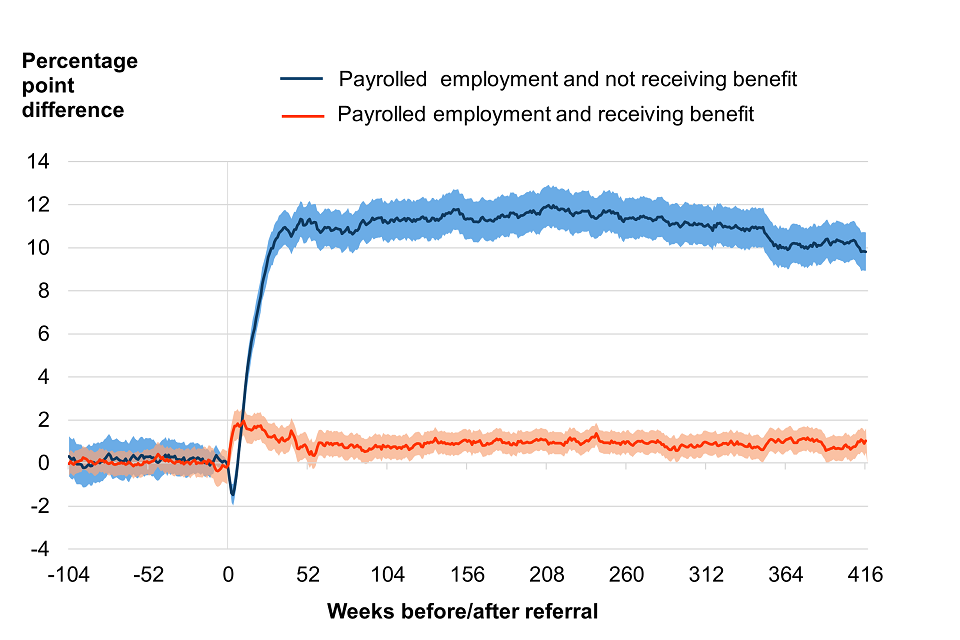

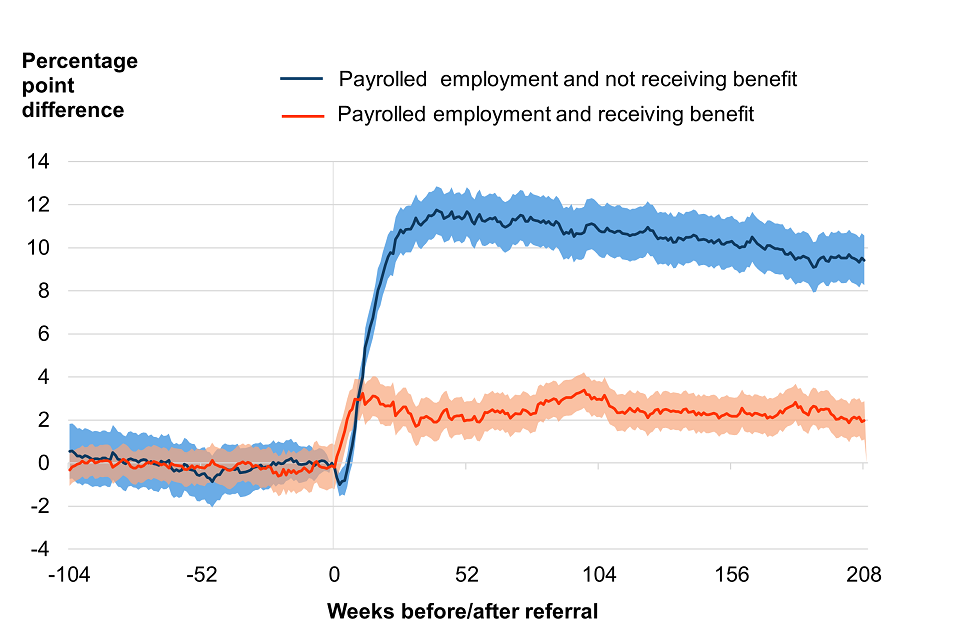

Payrolled employment figures include people receiving looking for work/low-income benefits whilst in payrolled employment. Figure 3‑3 shows the impact on payrolled employment whilst not receiving looking for work/low-income benefits, and the impact on payrolled employment whilst receiving looking for work/low-income benefits. This shows that some of the impact on payrolled employment is due to employment where individuals are also in receipt of looking for work/low-income benefits.

Figure 3‑3: The difference between the proportion of participants and proportion of the referred-only comparison group in payrolled employment split by in payrolled employment and not receiving looking for work/low-income benefit (blue line), and payrolled employment and receiving looking for work/low-income benefits (orange line) for a) the early cohort, and b) the later cohort.

a.

b.

Payrolled employment does not include self-employment, and overall employment rates (i.e., the proportion in either payrolled employment or self-employment) for both the participant and referred-only groups may be different from the payrolled employment rates. If the self-employment rates of the participant and referred-only groups are the same, then the estimate of the impact of Work Choice on overall employment is the same as presented here. If the self-employment rates differ between the two groups, then the impact on overall employment may be higher or lower than presented here.

3.2 The impact of work choice on looking for work/low-income benefit receipt

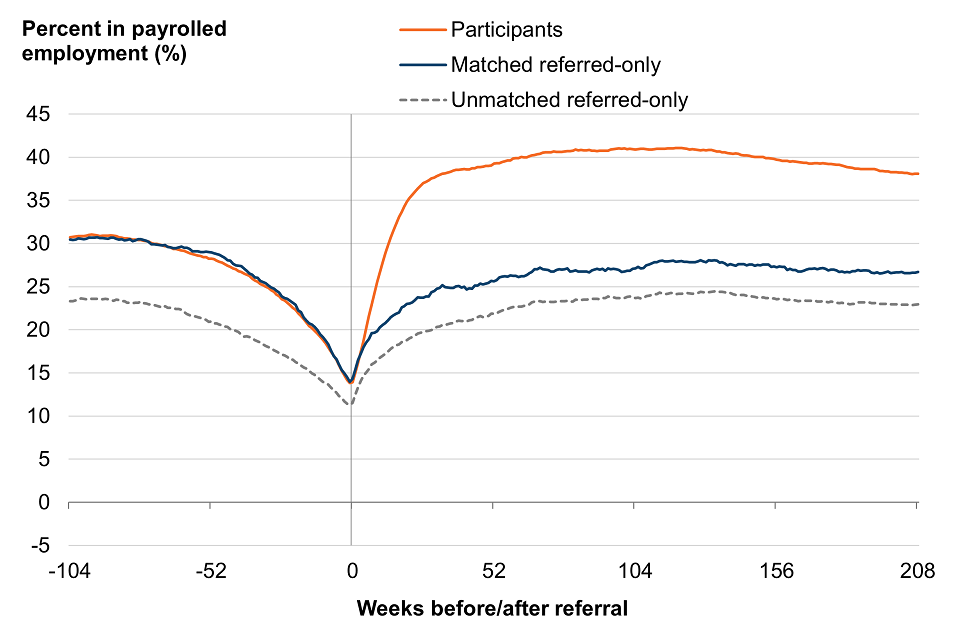

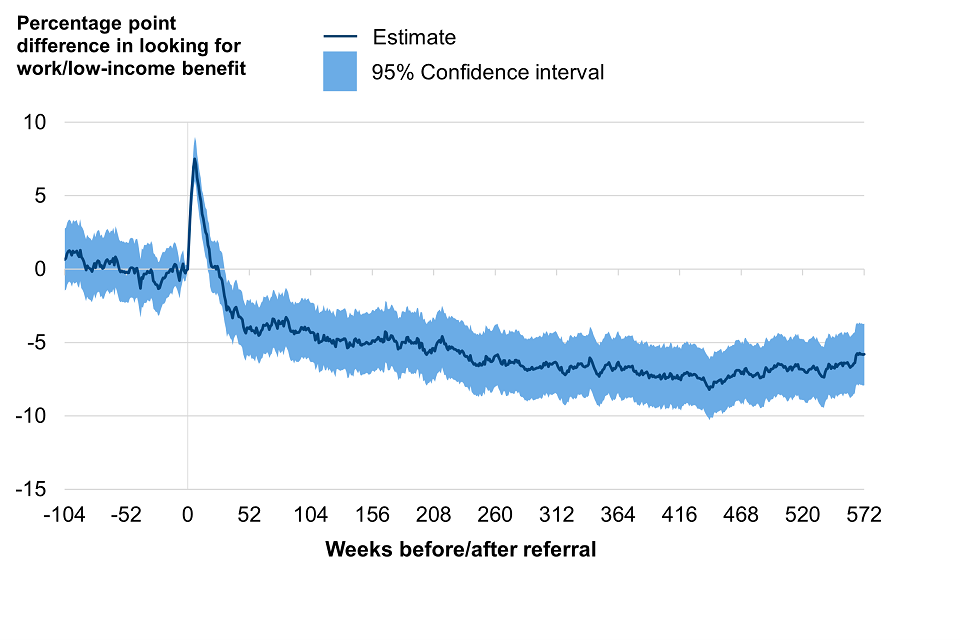

Over the years following referral, the proportion of people receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit fell for both the Work Choice participant and matched referred-only groups (Figure 3‑4 and Figure 3‑5). This decrease was greater for Work Choice participants than the referred-only groups.

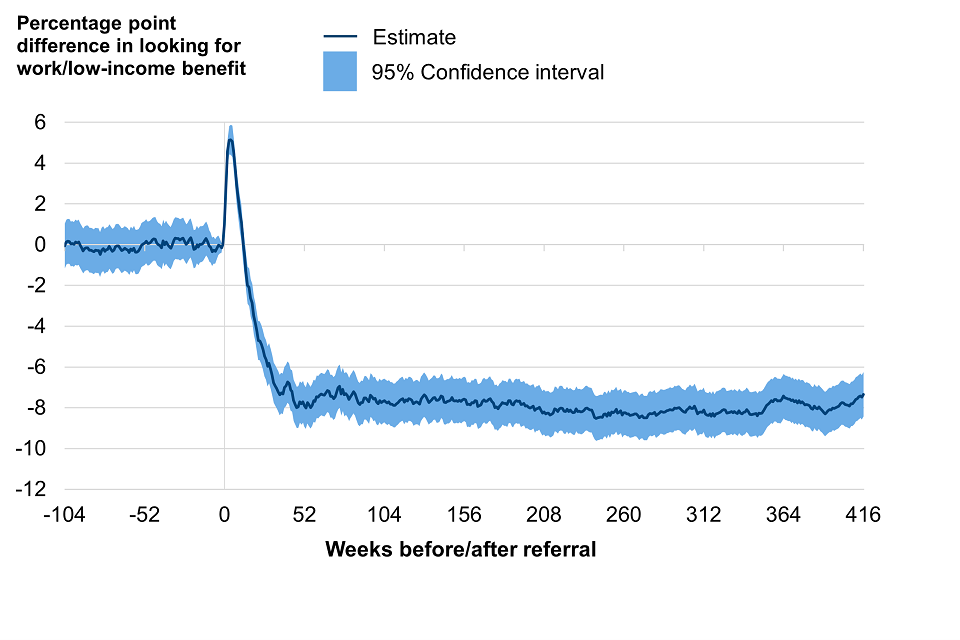

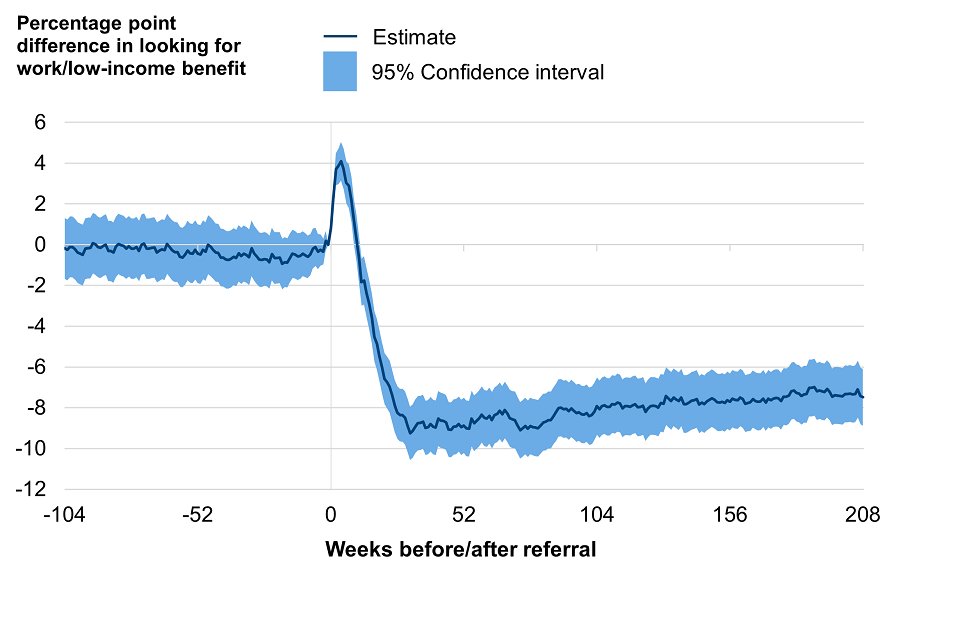

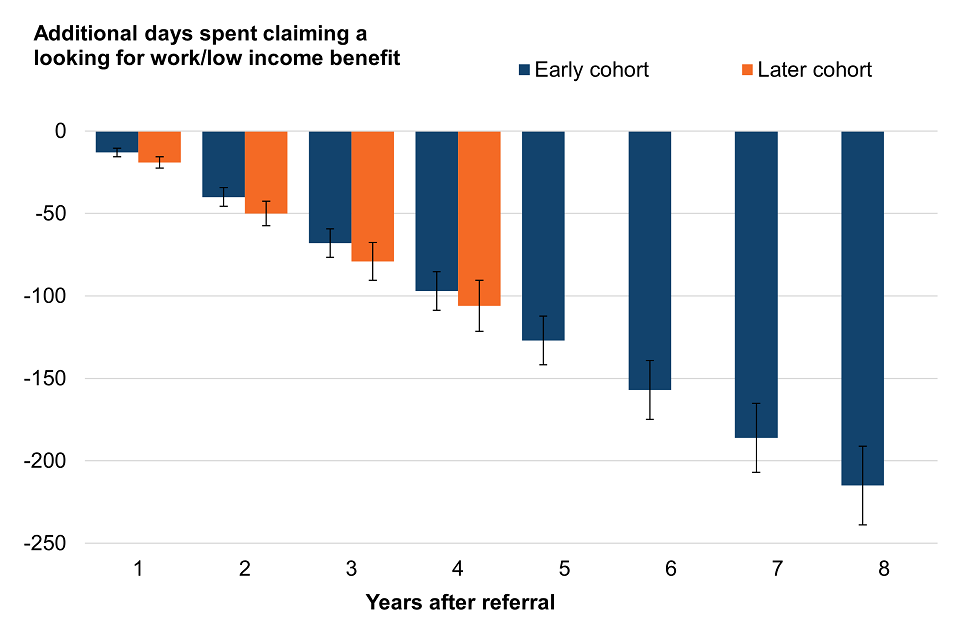

For the first 12 weeks following referral, early-cohort participants were more likely to be receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit.[footnote 5] However, for the remainder of the tracking period participants were less likely than the comparison group to be receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit. 52 weeks after referral to the programme, participants were 7.9 percentage points less likely (CI: -8.9 to -6.9) to be receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit (61.2% vs 69.1% Figure 3‑4 b). This impact declined slightly over the tracking period, but after 416 weeks early cohort Work Choice participants were still 7.3 percentage points less likely (CI: ‑8.4 to -6.2) to be receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit than the referred-only group (50.2% vs 57.5% Figure 3‑4 b). On average participants spent 215 fewer days (CI: -238 to -191) receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit (-7.4 percentage points, CI: -8.2 to ‑6.5) over that time.

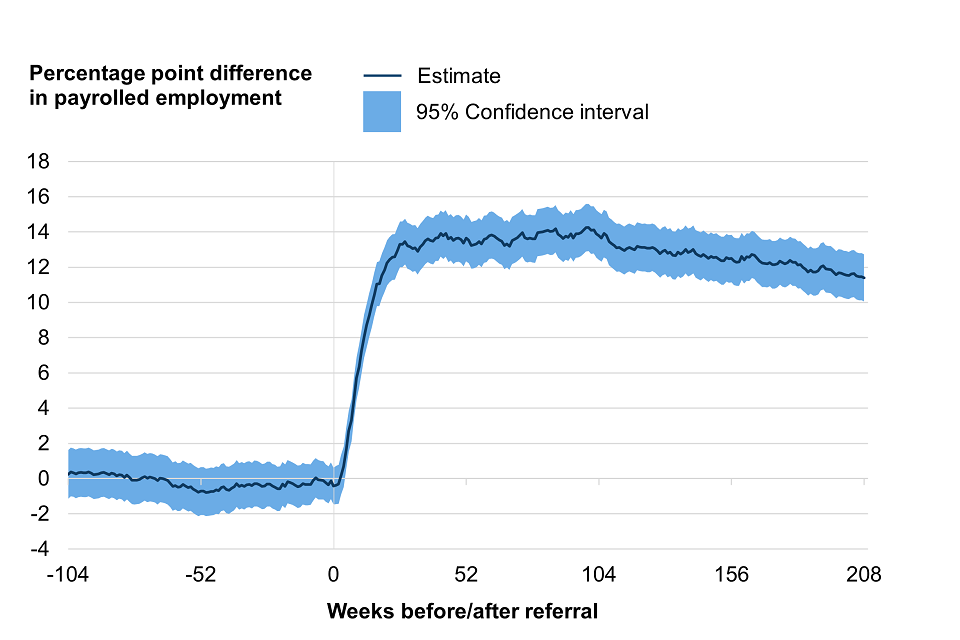

A similar pattern was seen for the later cohort. For the first ten weeks following referral, participants were more likely to be receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit.[footnote 6] After this, participants were less likely to be receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit. 52 weeks after referral to the programme participants were 8.9 percentage points less likely (CI: -10.2 to -7.5) to be receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit (63.0% vs 71.8% Figure 3‑5 b). This impact fell slightly but after 208 weeks later cohort Work Choice participants were still 7.5 percentage points less likely (CI: -8.9 to -6.1) to be receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit than the referred-only group (61.7% vs 69.2% Figure 3‑5 b). On average participants spent 106 fewer days (CI: -121 to -90) receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit (-7.3 percentage points, CI: -8.3 to -6.2) over that time.

Figure 3‑4: a) The percentage of the early cohort participant and matched referred-only group receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit by weeks after referral. b) The difference between the proportion of the early cohort participants and matched referred-only comparison group receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit by week after referral. This difference is the impact of Work Choice.

a.

b.

Figure 3‑5: a) The percentage of the later cohort participant and matched referred-only group receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit by weeks after referral. b) The difference between the proportion of the later cohort participants and matched referred-only comparison group receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit by week after referral. This difference is the impact of Work Choice.

a.

b.

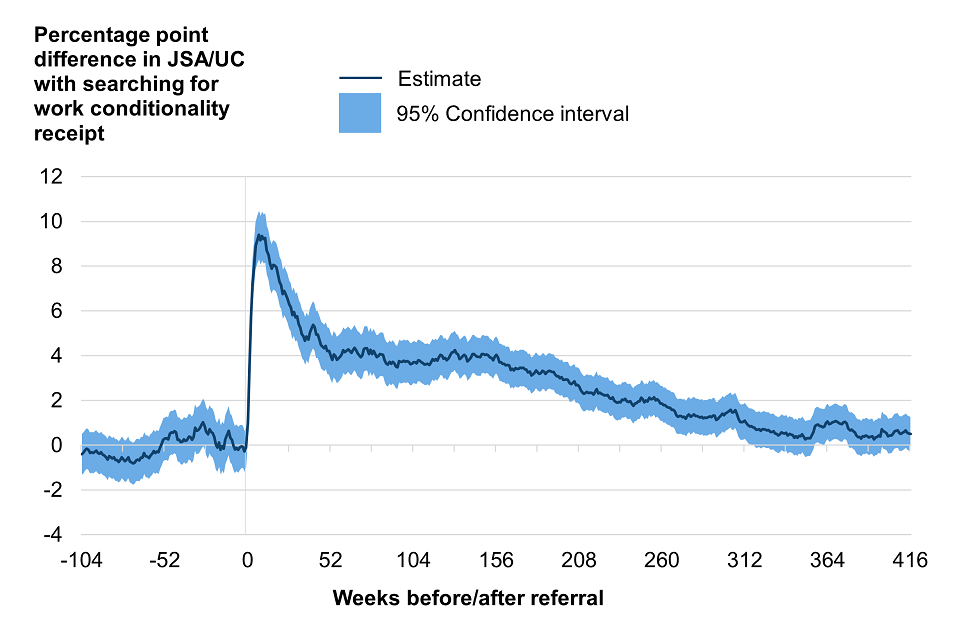

The impact of Work Choice was not the same for all individuals in receipt of looking for work/low-income benefits. For the early cohort, following the first 12 weeks post referral, Work Choice participants were less likely to be receiving any looking for work/low-income benefit but were more likely to specifically be receiving JSA or UC with Searching for Work conditionality (Figure 3‑6 a). After 416 weeks the average participant had spent 81 more days receiving JSA or UC with Searching for Work conditionality than the average person in the comparison group (CI: 64 to 98).

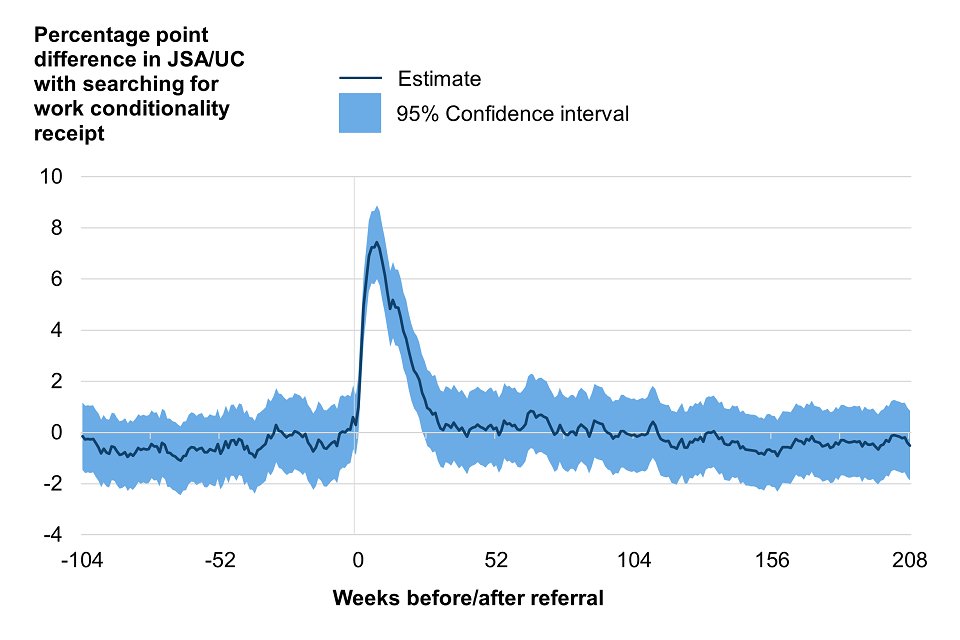

The same pattern was seen for the later cohort. Between weeks ten and 25 following referral, participants were less likely to receive any looking for work/low-income benefit but more likely to be receiving JSA or UC with Searching for Work conditionality (Figure 3‑6 b). For the remainder of the 208-week tracking period there was no impact of Work Choice on receiving JSA or UC with Searching for Work (Figure 3‑6 b).

Figure 3‑6: The difference between the proportion of the participant and matched referred-only comparison groups receiving JSA or UC with Searching for Work conditionality by week after referral for a) the early cohort and b) the later cohort.

a.

b.

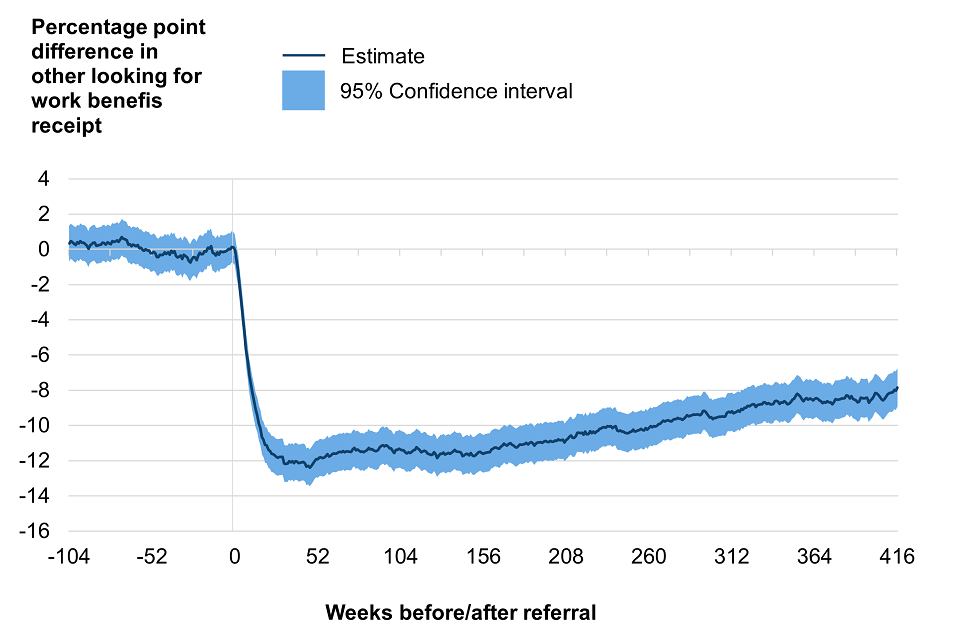

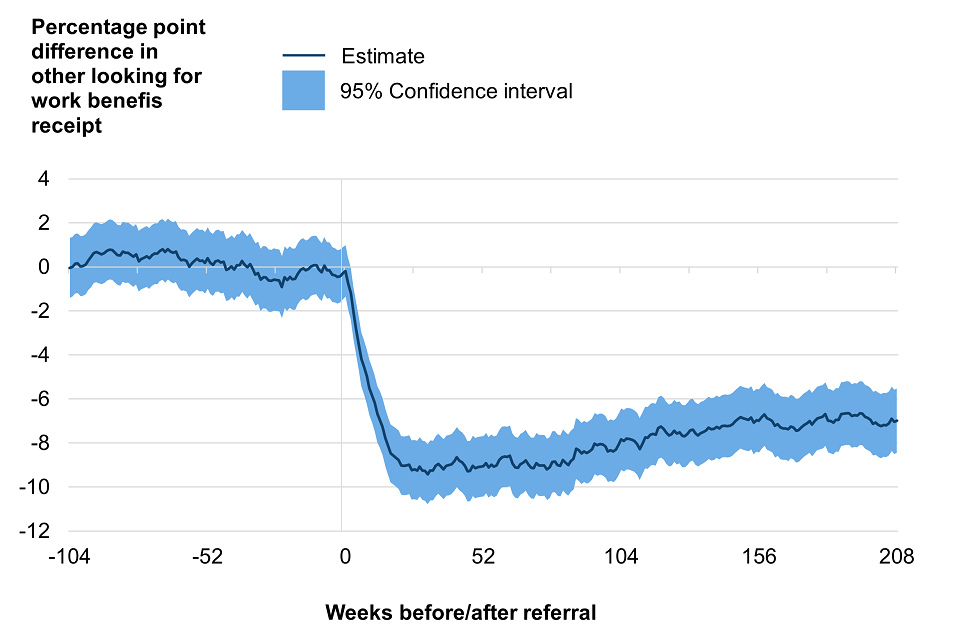

There was an opposing impact on receipt of other looking for work/low-income benefits. Work Choice participants were less likely than those in the referred-only group to be receiving other looking for work/low-income benefits (Figure 3‑7). After 416 weeks, the average Work Choice participant in the early cohort had spent 296 fewer days in receipt of other looking for work/low-income benefits (CI: -272 to -320). After 208 weeks, the average Work Choice participant in the later cohort had spent 112 fewer days in receipt of other Looking for work/low-income benefits (CI: -96 to -129).

Figure 3‑7: The difference between the proportion of the early cohort participant and matched referred-only comparison groups receiving other looking for work/low-income benefits by week after referral for a) the early cohort and b) the later cohort.

a.

b.

This was driven by a decrease in receipt of ESA. At referral 79% of participants and 81% of the matched comparison group in the early cohort, and not receiving JSA or UC with Searching for Work conditionality, were receiving ESA. At referral 90% of participants and 88% of the matched comparison group in the later cohort, and not receiving JSA or UC with Searching for Work conditionality, were receiving ESA.

416 weeks after referral to Work Choice early cohort participants had spent on average 264 fewer days in receipt of ESA than comparison individuals (CI: -241 to -288), and after 208 weeks later cohort participants had spent on average 98 fewer days in receipt of ESA than comparison individuals (CI: -83 to -113).

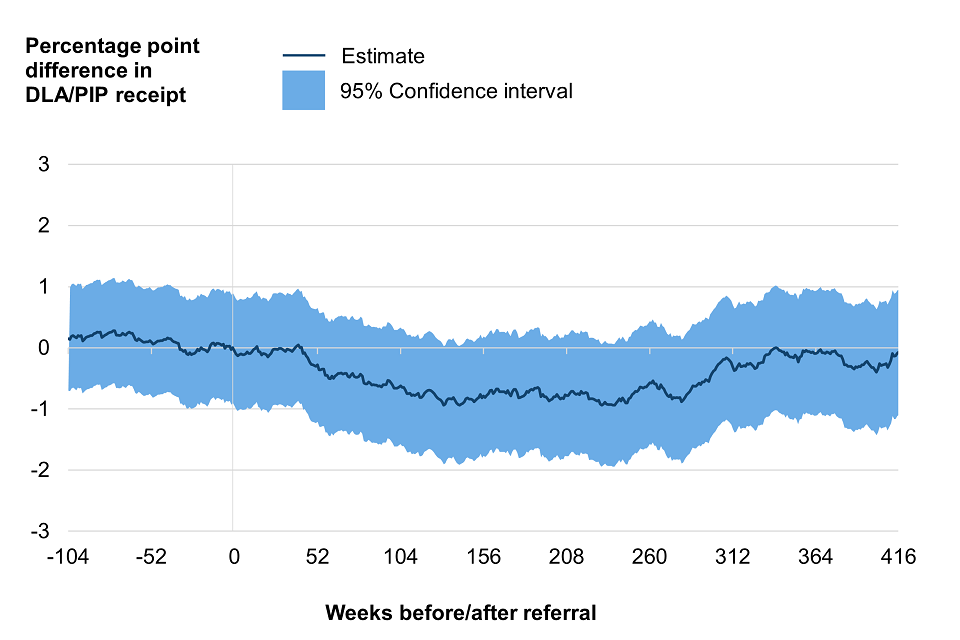

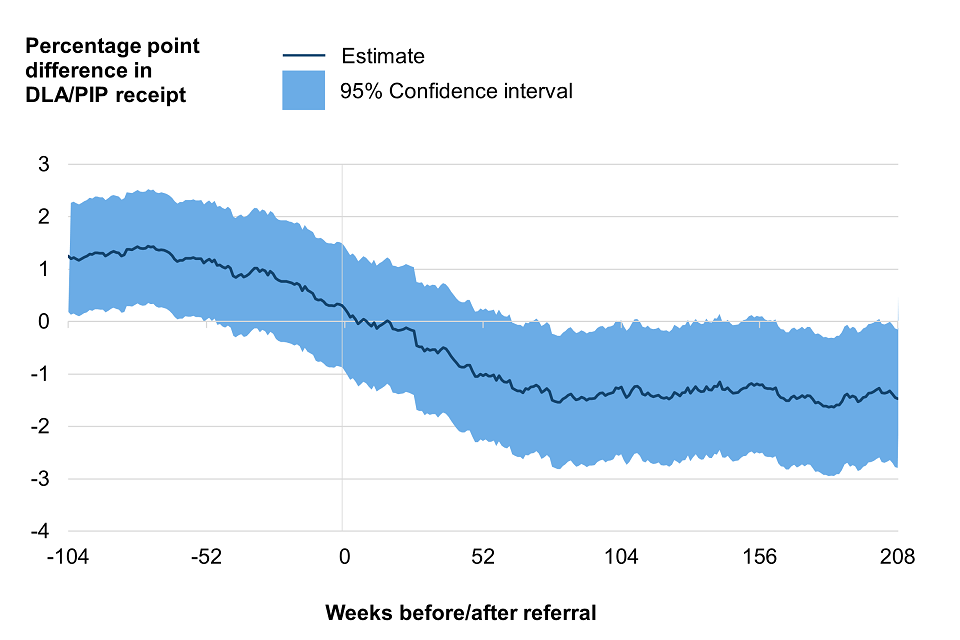

3.2.1 Impact on DLA/PIP

DLA/PIP are not income related benefits and can be claimed regardless of employment status. Work Choice was not designed to have an impact on receipt of these benefits but an association between ESA and DLA/PIP receipt has previously been observed. Work Choice could therefore have an indirect effect on DLA/PIP.

A positive impact would suggest that Work Choice participation leads to a rise in take up; Work Choice support may have better helped people understand their eligibility to disability benefits. A negative impact would suggest that Work Choice leads to a reduction in disability benefit, possibly via a reduction in ESA receipt.

Figure 3‑8a shows that for the early cohort there was no statistically significant impact on PIP/DLA receipt after referral. Figure 3‑8b shows that for the later cohort there is a small impact of about -1.5 percentage points for some months following referral. However, DLA/PIP receipt was not well balanced prior to referral.

Figure 3‑8: The difference between the proportion of the participant and matched group receiving DLA or PIP by week after referral for a) the early cohort and b) the later cohort.

a.

b.

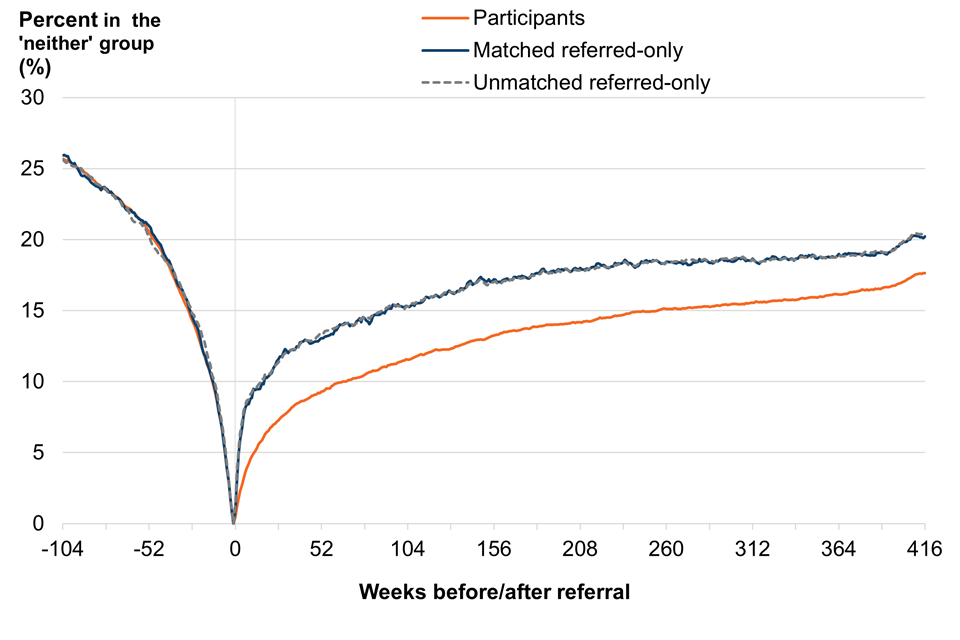

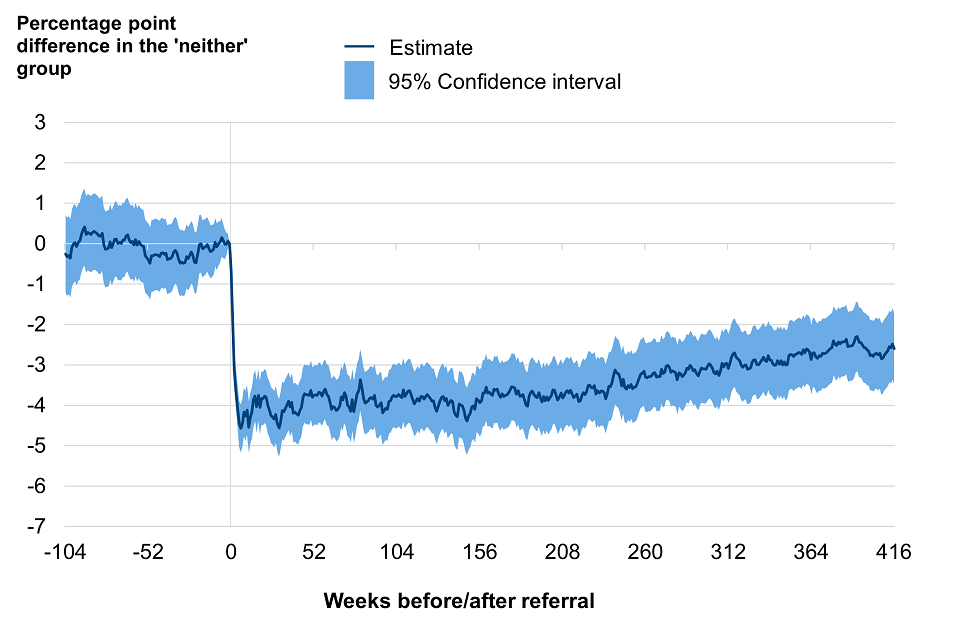

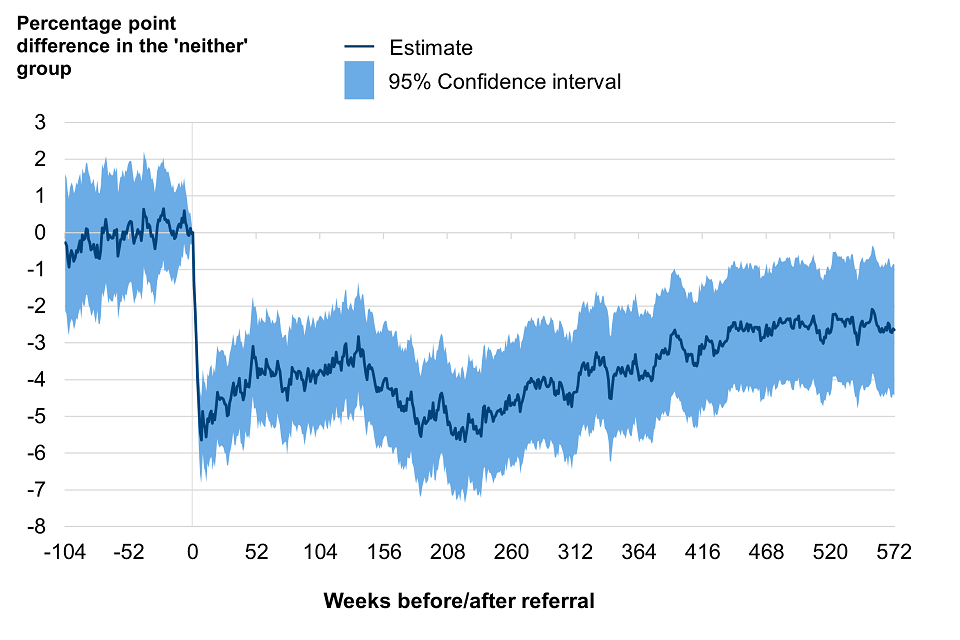

3.3 The impact on ‘neither’

The ‘neither’ outcome consists of people not in payrolled employment nor receiving looking for work/low-income benefits. Following referral to Work Choice, the proportion of both the participants and referred-only individuals in the ‘neither’ outcome increased for both cohorts (Figure 3‑9a and Figure 3‑10a). This increase was greater for the comparison group than for Work Choice participants.

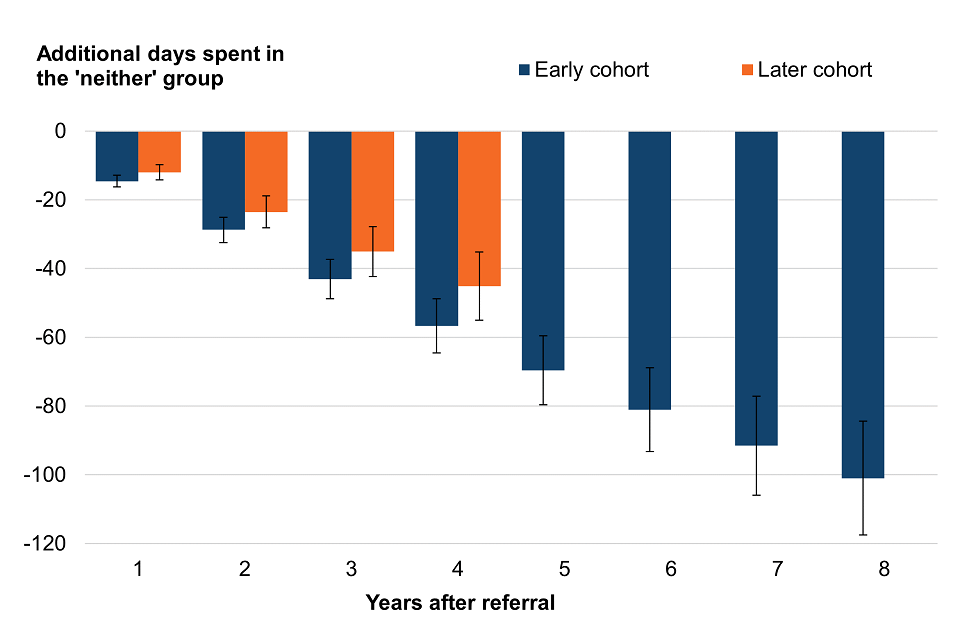

52 weeks after referral early cohort participants were 3.8 percentage points less likely (CI: -4.5 to -3.0) to be in the ‘neither’ outcome than the comparison group (9.3% vs 13.0% Figure 3‑9 b).This impact slowly declined over the remainder of the tracking period but after 416 weeks, Work Choice participants were still 2.6 percentage points less likely (CI: -3.5 to -1.7) to be in the ‘neither’ outcome than the matched comparison group (17.6% 20.2% Figure 3‑9 b). On average participants spent 101 fewer days (CI: -118 to -84) in the ‘neither’ outcome (-3.5 percentage points, CI: -4.0 to -2.9) over that time.

The results for the later cohort were similar. 52 weeks after referral, later cohort participants were 3.5 percentage points less likely (CI: -4.4 to -2.5) to be in the ‘neither’ outcome (8.0% vs 11.4% Figure 3‑10 b). This impact slowly declined over the remainder of the tracking period, but after 208 weeks Work Choice participants were still 2.3 percentage points less likely (CI: -3.2 to -1.3) to be in the ‘neither’ outcome (10.6% vs 12.8% Figure 3‑10 b). On average participants spent 45 fewer days (CI: -55 to -35) in the ‘neither’ outcome (-3.1 percentage points, CI: -3.8 to -2.4) over that time.

Figure 3‑9: a) The percentage of the early cohort participants and matched comparison group in the ‘neither’ outcome by weeks after referral. b) The difference between the percentage of the early cohort participants and matched comparison group in the ‘neither’ outcome. This difference is the impact of Work Choice.

a.

b.

Figure 3‑10: a) The percentage of the later cohort participants and matched comparison group in the ‘neither’ outcome by weeks after referral. b) The difference between the percentage of the early cohort participants and matched comparison group in the ‘neither’ outcome. This difference is the impact of Work Choice.

a.

b.

3.4 How long will impacts last?

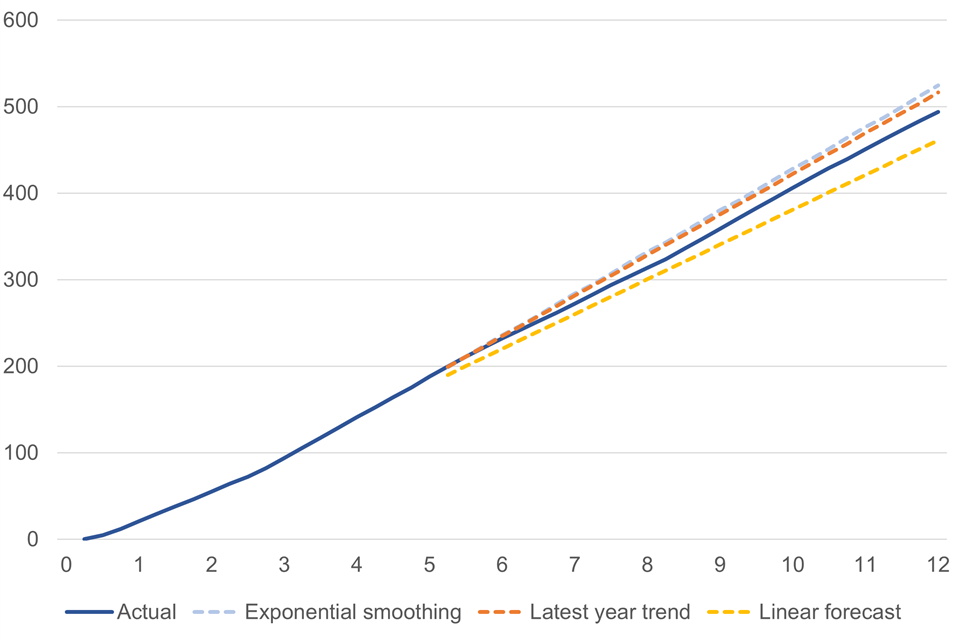

The early cohort of referrals from October 2010 to March 2015 can be tracked for eight years (416 weeks), which is considerably longer than for most DWP programme evaluations. By looking only at referrals up to March 2012 we can track outcomes for 11 years (572 weeks). For this cohort there was still an impact of Work Choice on labour market outcomes after 11 years. This suggests that the impact of Work Choice will be sustained for longer than the eight years observed for the later cohort.

After 11 years, participants were 9.7 percentage points more likely (CI: 7.9 to 11.6) to be in payrolled employment than the matched comparison group (35.1% vs 25.3% Figure 3‑11), and the average participant had spent 398 more days (CI: 341 to 455) in payrolled employment (9.9 percentage points, CI: 8.5 to 11.3) over this time.

Figure 3‑11: The difference between the payrolled employment rate of the participant and matched comparison groups referred before 5th April 2012, by week after referral. This difference is the impact of Work Choice.

Additionally, participants were 5.8 percentage points less likely (CI: ‑7.9 to -3.7) to be receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit than referred-only individuals (51.6% vs 57.4% Figure 3‑12), and after 11 years the average participant had spent 221 fewer days (CI: ‑282 to ‑160) in receipt of looking for work/low-income benefits (-5.5 percentage points, CI: -7.0 to -4.0) over this time.

Figure 3‑12: The difference between the participant and comparison groups receiving a looking for work/low-income benefit referred before 5th April 2012 by week after referral. This difference is the impact of Work Choice.

There was also an impact on the proportion who were in the ‘neither’ outcome. After 572 weeks participants were 2.7 percentage points less likely (CI: ‑4.4 to ‑0.9) to be in the ‘neither’ outcome than referred-only individuals (20.4% vs 23% Figure 3‑13), and had on average spent 149 fewer days (CI: -194 to -105) in the ‘neither’ outcome (-3.7 percentage points, CI: -4.8 to -2.6) over this time.

Figure 3‑13: The difference between the participant and comparison groups in the ‘neither’ outcome referred before 5th April 2012 by week after referral. This difference is the impact of Work Choice.

3.5 Subgroup analysis

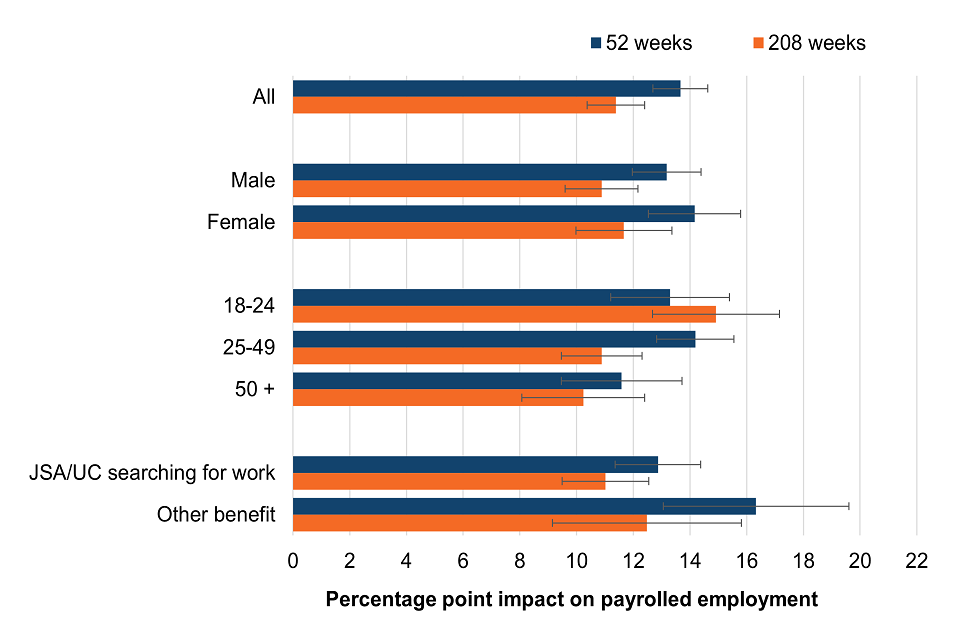

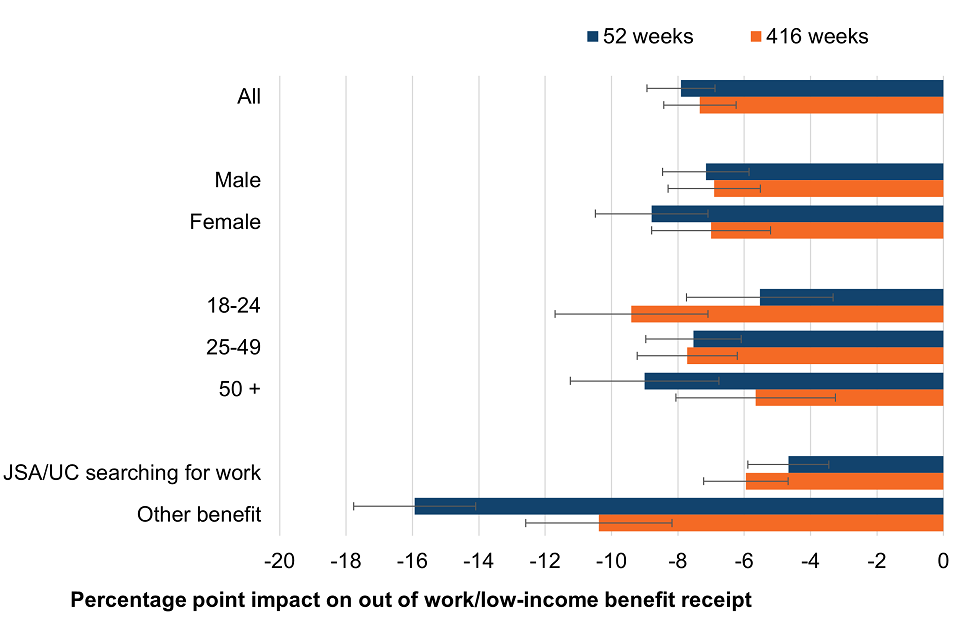

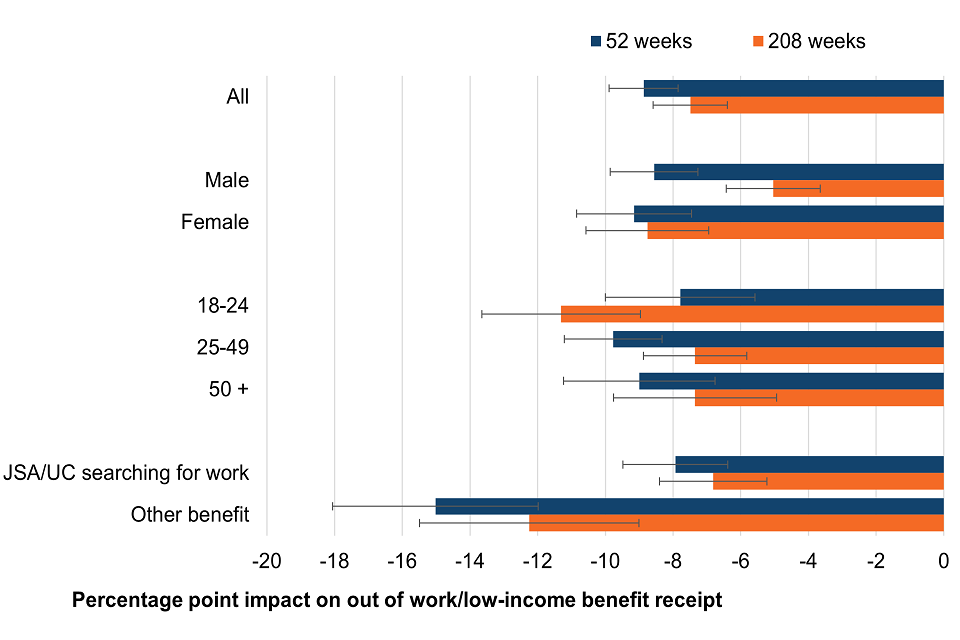

The impact of Work Choice on subgroups of participants was also investigated. This allowed us to investigate if impacts differ across participants with different characteristics. Specifically, we split participants by sex, age-group, and benefit at referral. This was done by including only individuals (both participant and referred-only) who met the specific subgroup criteria in the analysis. For each subgroup matching was performed following the method described in sections ‘2.5 Estimating propensity scores’ and ‘2.6 Matching’.

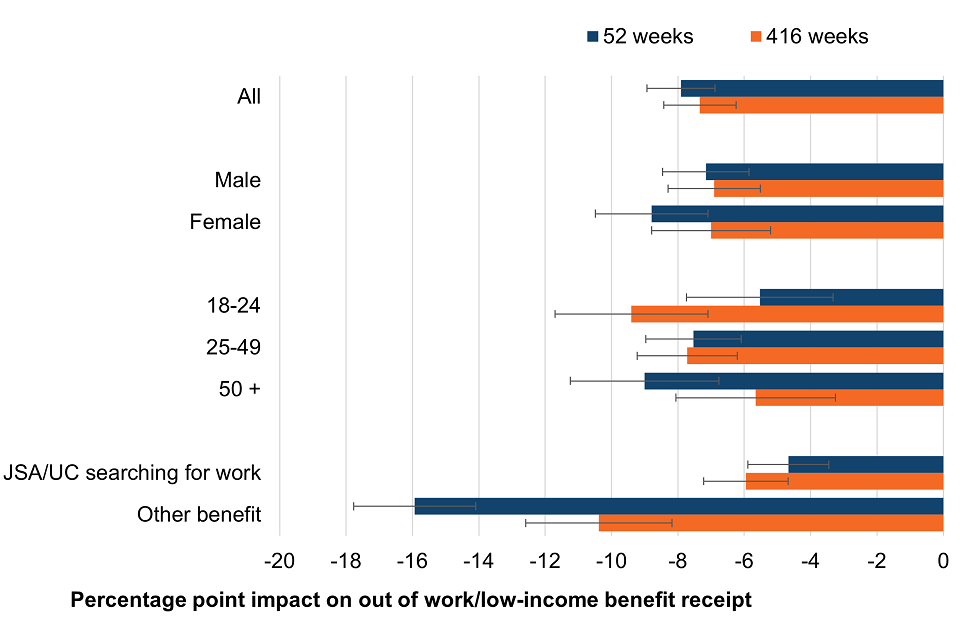

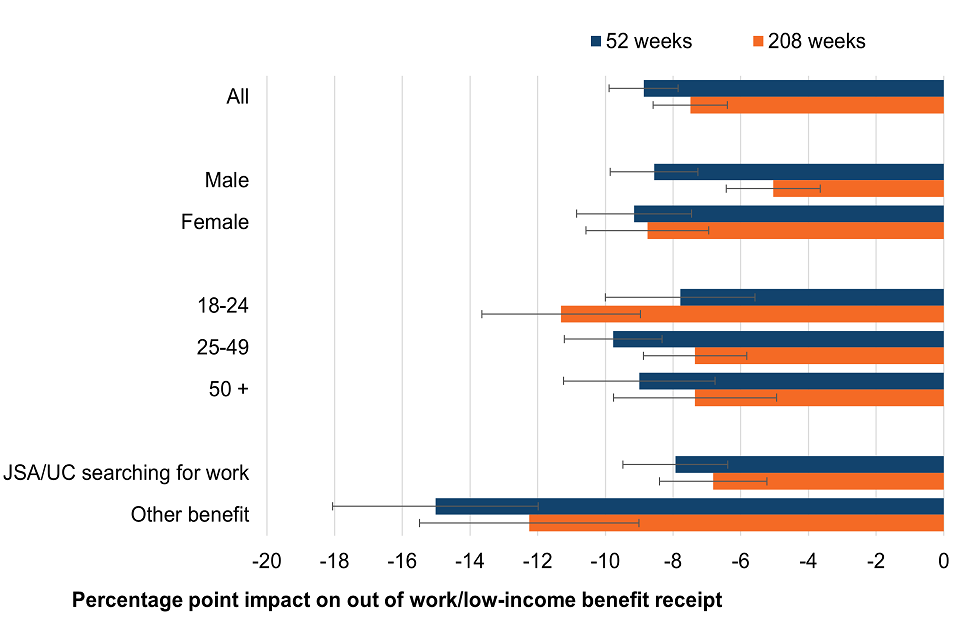

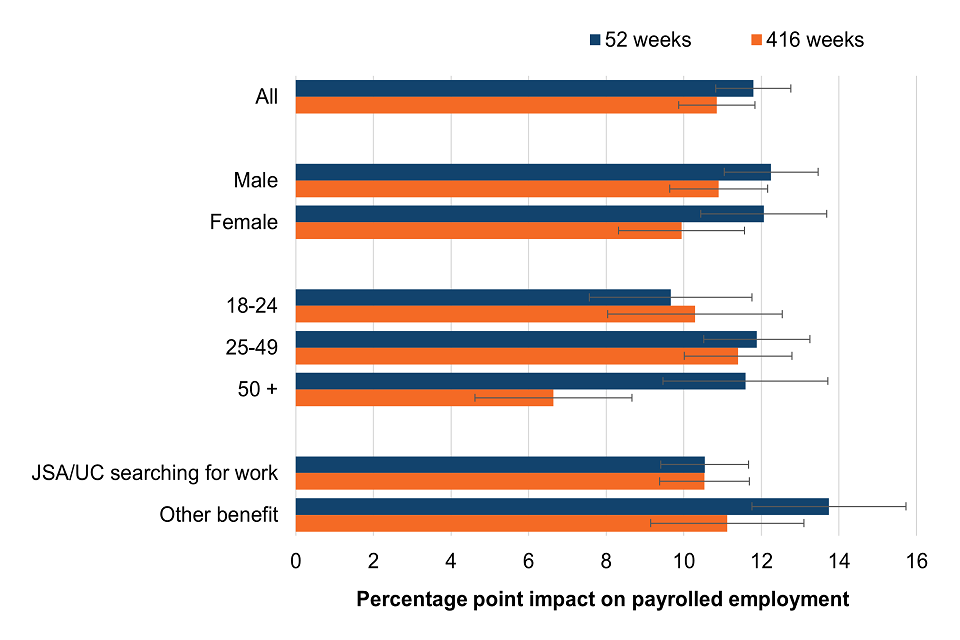

Across all groups analysed, at the end of the tracking period (208 or 416 weeks), Work Choice has a positive impact on payrolled employment, and a negative impact on looking for work/low-income benefit receipt. However, there are differences between subgroups in the magnitude of impacts. There is a larger negative impact on looking for work/low-income benefits, and a larger positive impact on payrolled employment, for those receiving benefits other than JSA or UC with searching for work conditionality at referral. The impacts on the ‘neither’ outcome are more mixed and confidence intervals are large.

Subgroup analysis is discussed in more detail in ‘Appendix E: Subgroup analysis’.

3.6 Summary of results

Work Choice had an impact on both payrolled employment and looking for work/low-income benefit receipt. Compared to referred-only individuals Work Choice participants were more likely to be in payrolled employment and less likely to be receiving looking for work/low-income benefits over the years following referral (Table 3‑1and Table 3‑2). Movement off a looking for work/low-income benefit is normally due to moving into employment where the hours worked, or earnings gained, are enough to lose looking for work/low-income benefit entitlement.

Work Choice participants were also less likely to be in the ‘neither’ outcome (neither in payrolled employment nor receiving looking for work/low-income benefits) (Table 3‑3). We do not know the composition of this group. This group includes, among others, individuals in self-employment and not receiving looking for work/low-income benefits, and those still looking for work but with no access to looking for work/low-income benefits. However, it will also include individuals who have left the labour market and are not receiving looking for work/low-income benefits, for example due to education/training, retirement, or caring responsibilities.

One possible explanation of the impact of Work Choice on this group is that Work Choice might cause some participants who would otherwise have been self-employed to become PAYE employees instead. Even if this is the case, and this represents a reduction in self-employment, there is still a positive impact on total employment (PAYE employment plus self-employment). Another possible explanation is that Work Choice prevented some individuals from leaving the labour market and they instead either found employment or were searching for work and entitled to looking for work/low-income benefits.

The impacts of Work Choice differed in magnitude between the two cohorts. This could reflect several things including different labour market contexts, differences in the characteristics of the cohorts, or possibly increasing effectiveness of the programme over time. Subgroup analysis also shows that the impact of Work Choice differs between participants with different characteristics.

Overall Work Choice had a positive impact on labour market outcomes through additional time in employment, less time receiving looking for work/low-income benefits, and less time in the ‘neither’ outcome (Table 3‑1 to Table 3‑3, Figure 3‑14). Analysis of the earliest referrals suggests that these impacts will be sustained for several more years.

Table 3‑1: The impact of work choice on payrolled employment, and total additional days spent in payrolled employment, by year after referral. Confidence intervals in parentheses.