Victim services commissioning guidance

Published 12 December 2024

Applies to England and Wales

Foreword from Victims’ Minister:

Halving violence against women and girls is a landmark mission of this Government. But where these horrific crimes do happen, we want every victim to know they can access the right support to help them rebuild their lives. When victims know they will be heard, helped and taken seriously, confidence in the justice system grows - empowering more victims to come forward and see through their cases, so we can bring more criminals to justice.

Most victims need at least some level of support to recover from what has happened to them, even more so in the worst, most life-altering cases. Some also need help to navigate a system that can be complex and confusing. In many ways, victim support services are the backbone of the justice system - ensuring that victims can access whatever support they need, wherever they are in the process.

Local commissioning of victims’ services is now well-established under Police and Crime Commissioners (PCCs) – with more focus on local collaboration in the pursuit of better outcomes for victims. The work done by PCCs – as well as Integrated Care Boards, local authorities, and other local partners – to support the commissioning of victim support services is invaluable. That’s because they understand what their communities need and can both plan and commission the right services.

The Victims Funding Strategy was published in May 2022, and included a pledge to review and refresh existing guidance to reflect updated priorities and changing funding models. This guidance delivers on that promise.

This document aims to enable local commissioners to achieve national commissioning standards and reflect this Government’s priorities. It includes specific information on collaboration and co-commissioning, support for child victims and those from marginalised groups, and examples of best practice and advice to support sound decision-making.

The guidance captures the breadth of depth of services for victims as they exist today, taking account of how they have developed over the last decade – a contemporary guide to commissioning and developing better services for victims.

Supporting victims properly strengthens our justice system to get the right outcomes. That doesn’t just mean more victims get the justice they deserve. It allows the system to convict more offenders, prevents further crime and, ultimately, reduces the number of victims there are in the future. This guidance will support those commissioning services for victims at the local level to raise standards in the pursuit of those crucial aims.

Alex Davies-Jones MP

Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Victims and Violence Against Women and Girls

Foreword from Association of Police & Crime Commissioners (APCC):

Police and Crime Commissioners, Police Fire and Crime Commissioners, and Deputy Mayors representing the Mayoral Authorities commission a wide range of services including reducing re-offending, diversion and other crime prevention and community safety services. We take a leading role in commissioning support services for victims of crime, supporting them to cope and recover. Victims’ advocacy is at the heart of everything PCCs do, from those critical commissioned services to the way we hold our chief constables to account, and our central role as local leaders in bringing statutory agencies and partners together to deliver better outcomes and innovative solutions.

This guidance is a useful reference for PCCs and their offices in developing their approaches, recognising the importance of local flexibility in delivering the right services for victims at the right time. It provides an overview of key commissioning principles, such as delivering needs assessments, engaging victims, and working with a variety of providers which are hugely important for PCCs. The guidance considers commissioning services for children and young people, and victims from marginalised groups, and PCCs should examine how they might utilise these approaches.

This guidance shows how PCCs are effectively developing resources, delivering innovative methods, and collaborating with other commissioners to ensure that victims’ voices are reflected in service provision. By engaging by-and-for and grassroots service providers, Commissioners strive to make a difference to some of the most vulnerable in our communities.

Effective collaboration and partnership working is another vital opportunity for PCCs to deliver a quality and joined-up service for victims. We continue to do so with support from our strategic partners including service providers, third-sector organisations, the health sector and local government.

However, I recognise the very real challenges that sit alongside any guidance, sufficient and sustained funding, workforce retention and support, court backlog, victims’ trust and confidence in the system, and the opportunities that accompany both local and national elections. Though this guidance will certainly support us to reflect on our approach to these challenges, there must be a wider conversation about how to address them.

PCCs will continue to deliver quality services for victims and promote victims’ voices, through the services we commission, and our wider work. I am delighted to have worked with the Ministry of Justice to jointly produce the refreshed guidance on victims’ commissioning and are hugely grateful for the valuable contributions from PCC offices to developing this guidance.

Emily Spurrell

Chair of the Association of Police and Crime Commissioners

About this guidance

This guidance has been developed jointly by the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) and the Association of Police and Crime Commissioners (APCC).

The guidance is aimed at commissioners of victim-specific support services such as Police and Crime Commissioners, Police, Fire and Crime Commissioners and Mayoral Authorities (from here on, all are referred to collectively as ‘PCCs’). Local Authorities (LAs) and Integrated Care Boards (ICBs)[footnote 1] are encouraged to take account of this guidance where they commission support for victims, for example supporting victims within safe accommodation, and Sexual Assault Referral Centres (SARCs).

The guidance is aimed to support commissioners in their role in providing local support services to victims of crime. It is not intended to be an exhaustive ‘how to’ on commissioning local victim support services, and instead should stand as a benchmark of good practice which can be utilised by commissioners when creating local commissioning strategies. This guidance has been written with commissioning holistic victim support services in mind, and not all elements will be relevant for commissioners conducting targeted commissioning for a specific crime type. This guidance is not statutory, but advisory, and is meant to support commissioners in making the best commissioning decisions.

Other agencies, such as His Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS), the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) and local police forces, as well as national Government departments, are invited to take account of the guidance in their capacity of supporting victims and commissioning victims’ services.

The Victims Funding Strategy, and therefore this guidance, is primarily focused on funding and commissioning that supports victims of crime, whether or not they report the offence. This does not mean that the information would not be applicable in other similar or overlapping areas such as services for witnesses.

This guidance was developed with input from PCCs, LAs, National Health Service (NHS) England and other government departments including Welsh Government, whose valuable insight supported the scope and direction of the document. The chapters in the document reflect areas which came up frequently during this engagement.

Terminology

For the purposes of this guidance:

‘Victim’ - refers to a person who has suffered harm (physical, mental or emotional, and economic loss) as a direct result of (one or more of the below):

- Being subjected to criminal conduct;

- Where the person has seen, heard, or otherwise directly experienced the effects of criminal conduct as the time the conduct occurred;

- Where the person’s birth was the direct result of criminal conduct;

- Where the death of a close family member of the person was the direct result of criminal conduct;

- Where the person is a child who is a victim of domestic abuse which constitutes criminal conduct.[footnote 2]

A person is a victim and can seek support regardless of whether they have reported the crime to the police.

‘Child or Children’ - refers to any person under the age of 18.

‘Young Person or People’ - can be context specific, but usually refers to any person or group of people aged between 18 and 25 years.

‘By-and-for services’ - These are specialist services that are led, designed and delivered by and for the users and communities they aim to serve (for example, victims and survivors from ethnic minority backgrounds, deaf and disabled victims and LGBT victims).[footnote 3]

1. Introduction

Following the publication of the Victims Funding Strategy[footnote 4] in May 2022, the MoJ committed to reviewing and refreshing existing commissioning guidance, so that it reflects updated priorities, as well as the evolving funding and commissioning landscape. The original Victim Services Commissioning Framework was published in 2013, when PCCs were newly established, and victims commissioning had just moved to a mixed national and local model.

Since then, the local commissioning process has become well-embedded in the victim support landscape, with PCCs commissioning a significant portion of victims services at a local level, alongside LAs and ICBs. This is on the basis that these commissioners are well placed to understand and meet the needs of their local populations.

With the introduction of the Victims and Prisoners Act, we are now more than ever focused on how to improve commissioning of support for victims of crime. This refreshed guidance will set out updated practice for commissioning and focus on a few key areas – effective collaboration and co-commissioning with other local agencies, services for children and young people, and services for victims from marginalised groups.

1.1 Funding for local commissioners for services supporting victims of crime

Grant funding for the commissioning of victim support services continues to be provided to PCCs by the MoJ under powers given to the Secretary of State by section 56 of the Domestic Violence, Crime and Victims Act 2004[footnote 5]. This provides that the Secretary of State may “pay such grants to such persons as he considers appropriate in connection with measures which appear to him to be intended to assist victims, witnesses or other persons affected by offences”. Section 143 of the Anti-Social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014[footnote 6] gives PCCs the power to provide, or arrange of the provision of, support services for victims of crime. To note, these powers do not supersede procurement regulations[footnote 7].

Funding for local authorities to meet their statutory duty under Part 4 of the Domestic Abuse Act 2021 to provide support within domestic abuse safe accommodation for victims and their children is provided by the Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG). Local authorities should commission services that reflect the needs of all victims in the local area. Local authorities are required to report back to MHCLG annually on support provided to victims in delivering their duties.

Local authorities have wide-ranging powers to provide services for the benefit of local residents, and so, depending on local priorities, they may choose to provide community-based services to domestic abuse victims funded from their general budget.

The Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC) provides funding to local authorities under the public health grant, which is used to provide preventative services to support health, including sexual health services which may support victims of crime. The NHS Act 2006[footnote 8] requires DHSC to formally set out mandated objectives which NHS England must seek to deliver. Financial Directions to NHS England set the NHS budget. Detail set out within the directions includes any ringfenced budgets to meet specific policy aims.

NHS England is responsible for funding allocations to ICBs. This process is independent of government and is based on underlying formulae which provides a ‘target allocation’ for each area, based on an assessment of factors such as demography, deprivation, and morbidity.

1.2 The Victims’ Code and Witness Charter

The Victims’ Code[footnote 9] sets out a minimum level of service that criminal justice bodies are expected to provide to victims of crime. This includes offering appropriate support to a victim of crime but is clear that victims can access support regardless of whether they report. It is also important to note that the Code recognises victims under the age of 18, and those who have been the victims of certain crimes, as vulnerable, and therefore entitled to enhanced rights.

The Witness Charter[footnote 10] sets out standards of care for witnesses in the criminal justice system. It applies to all witnesses of crime, and covers both prosecution and defence witnesses, setting out the help and support they can expect to receive at each stage of the process.

1.3 Victims Funding Strategy

The Victims Funding Strategy (VFS) is a cross-government Strategy, published in 2022, that sets out a framework to improve the way we fund victim support services across government, seeking to better align and co-ordinate funding to enable victims to receive the support they need. The VFS outlines core metrics and outcomes that commissioners should collect data against, to monitor and evaluate the services they choose to fund. The VFS built on the work undertaken as part of the Victims Strategy[footnote 11] in 2018, and was developed as a response to the changing commissioning landscape as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic.

In the VFS, three key strategic aims were introduced:

- Fund the victim support sector more strategically

- Remove barriers to access

- Implement clear and consistent outcomes

Working towards these three aims forms the basic principles of this guidance, focusing on how effective commissioning can enable services to deliver quality support to improve outcomes for victims.

Under the aim of removing barriers to access, the VFS introduced national commissioning standards, applicable to commissioners of victim support services, which encourage an expected quality of service for victims. These standards are:

- Victims at the centre of commissioning, including seeking victim voices as part of the commissioning cycle and commissioning services in response to need.

- A whole-system approach to commissioning, encouraging join-up with other commissioners and agencies where possible.

- Equitable access to services, ensuring that all victims can access the services that are right for them, including tailored services.

- Clear and consistent mechanisms for reporting and evaluation, ensuring that reporting requirements are clear, and services are regularly evaluated for improvement.

Promote sustainable funding, encouraging commissioners to look for alternative funding sources and build up relationships with the third sector.

For more detail on the commissioning standards, commissioners are encouraged to read the VFS in detail[footnote 12]. Annex B outlines the core metrics and outcomes that were also introduced as part of the VFS.

1.4 Wider victims’ strategy

1.4a Victims and Prisoners Act 2024

The Victims and Prisoners (VAP) Act 2024 introduced measures which aim to create a more strategic and coordinated approach to funding local victim support services, and make sure victims know about their rights in the Code, and that agencies deliver them.

With the commencement of the VAP Act, a new duty will be placed on PCCs, LAs and ICBs in England to collaborate in the commissioning of support services for victims of domestic abuse, sexual abuse, and serious violence (“the Duty”). The Duty aims to bring together relevant bodies when commissioning these services to increase join-up and improve strategic co-ordination. We expect this duty to result in strengthened collaborative commissioning processes and improve victims’ experiences of quality and timely support services. Further guidance for commissioners will accompany the Duty.

The VAP Act will also require the Secretary of State to issue statutory guidance for victim support roles that will be specified in regulations. The initial intention is to use this to publish guidance about Independent Sexual Violence Advisors (ISVAs) and Independent Domestic Violence Advisors (IDVAs) roles, as well as Independent Stalking Advocates (ISAs), to offer improved consistency in how these roles operate.

1.4b Other legislation

In the past few years, there has been a range of new legislation introduced relating to the duties and responsibilities of local commissioners. This includes the introduction of the duties placed on local authorities as part of the Domestic Abuse Act (2021)[footnote 13] and the Serious Violence Duty as part of the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act (2022)[footnote 14]. The Modern Slavery Act (2015) also placed a duty on local authorities to identify and refer modern slavery child victims and consenting adult victims through the National Referral Mechanism (NRM).[footnote 15] A longer list of legislation can be found in Annex C.

This commissioning guidance supplements any guidance accompanying legislation, including the Serious Violence Duty and the upcoming Duty to Collaborate as part of the Victims and Prisoners Act. It should also be used to supplement the existing guidance for local authorities in fulfilment of their duties under Part 4 of the Domestic Abuse Act.

1.5 Devolved Administrations

The guidance will apply to PCCs in England and Wales, and to Local Authorities and Integrated Care Boards in England only. In Wales, LAs and local health boards are devolved. In Wales, Welsh PCCs are encouraged to participate in partnership delivery to support victims of domestic abuse and sexual violence through separate legislation. The Violence Against Women, Domestic Abuse and Sexual Violence (Wales) Act 2015 (VAWDASV) places a duty on Welsh local authorities and Local Health Boards to jointly prepare, publish and from time to time, review a local strategy setting out how they will improve local arrangements and support regarding VAWDASV, in line with the principles of the Act, namely prevention of gender-based violence, domestic abuse and sexual violence, and protection and support for those affected.

Funding and commissioning for victim support services is completely devolved in Scotland and Northern Ireland.

2. Commissioning Process

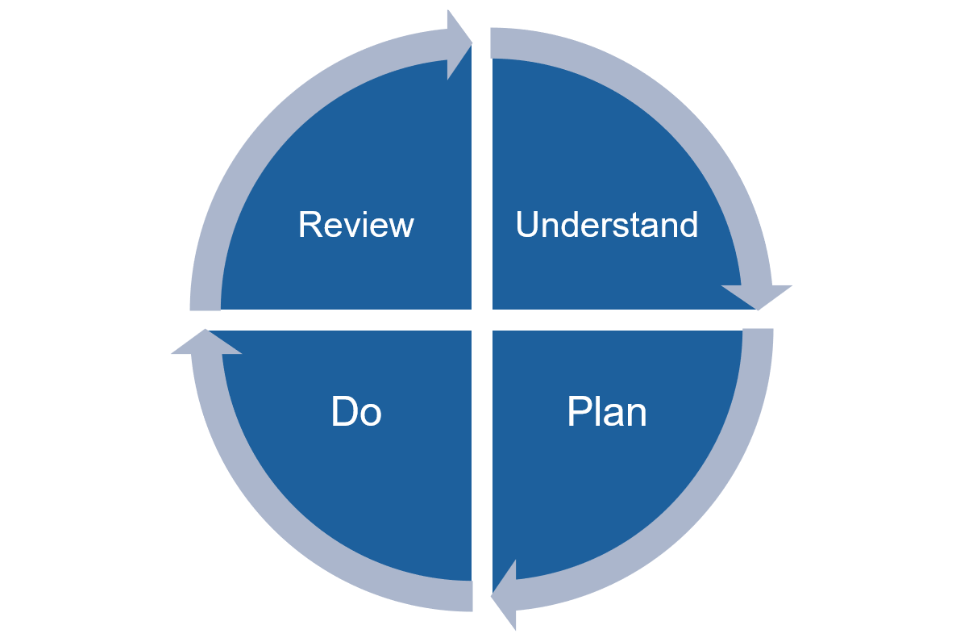

All commissioning cycles are similar, in that they follow a continuous service improvement model with a four-stage approach. The process of ‘understand, plan, do, and review’ are the basis of the victim support commissioning cycle.

Whilst PCCs are the main audience for this guidance and therefore this process reflects their commissioning cycle, local authorities and ICB commissioning best practice will follow similar principles.

-

Understand: Within this strand of work, commissioners should scope the needs of the community by recognising outcomes that the community want to be achieved, and identifying resources and priorities. This should include speaking to communities, gathering an understanding of what services are needed, engaging with victims and local partners, and completing needs assessments. This should include learning from previously commissioned services. Information should also be gathered through other service providers irrespective of whether that have been commissioned by the PCC, which will help with further understanding of key needs and creating continuous innovation in the provision of services. Within this, commissioners should understand ‘hidden’ and ‘unmet’ demand from marginalised groups and consider sources wider than police or statutory service data to ensure a more holistic picture is captured.

-

Plan: This section utilises needs assessments and expands on the information gathered in the ‘understand’ phase. Commissioners should map out ways to address the needs identified and the best route of providing them. They also should identify potential service providers and undertake due diligence, which could be done within procurement stages, such as at pre-market engagement. During this phase and throughout the commissioning cycle, commissioners should continue to build on the relationships with other partners and engage service providers for their expertise. It is important to note this should be done in a way that does not impact the procurement routes; for example, creating bias to one service provider based on questions asked and proposals. As and where possible, commissioners may build the capacity and capability of services from the Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise (VCSE) sector. Based on the information gathered, the service will either align better to a contract route or a grant route.

-

Do: Commissioners undertake the contracting or grant process once the budget and/or funding to secure services and activities has been agreed. This process should be done in alignment with procurement regulations and in a fair and transparent process for all organisations who have expressed interest. Commissioners may choose to utilise a combination of contracts, grants, co-commissioned and/or co-funded activity to meet their priorities. Commissioners may also have the service delivered through a single organisation or as a consortium where organisations have combined resources to deliver the service.

-

Review: This involves continuous monitoring of services against agreed outcomes and decommissioning of services as and when needed. In doing so, commissioners should seek feedback from victims, service users, providers, and partners. This stage also informs the ‘understand’ strand, with feedback as a key source to inform understanding in this iterative cycle of commissioning. The level of review will be dependent on if the service is under a contract or a grant.

It is important to recognise that the model can be adapted by commissioners at a local level, as they choose, providing that the process covers a shared model for understanding needs, planning, delivering value for money outcomes. There should be an open review of the effectiveness of these services, to support victims to cope and build resilience to move forward with their daily life against the backdrop of diverse, intersecting, multiple and complex needs.

2.1 Understand

2.1a Assessing Need

Assessing need ensures that commissioning intentions are informed by an understanding of the need of victims and whether these needs are met by existing services. As such, this should include an evaluation of the current and future needs of the local population to establish a suitable strategy. It also provides opportunities to support service improvements, reduce service overlaps, address gaps, and move resources.

As highlighted in the Home Office’s Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG) Commissioning Toolkit[footnote 16], meaningful needs assessments must consider the different backgrounds and experiences of victims. This includes understanding the different ways in which they prefer to access support, for example does the assessment fully consider the distinct needs and overlapping experiences of women from ethnic minority backgrounds.

There are different ways to approach needs assessments and this will vary locally. Commissioners may effectively utilise data analytics teams and in-house facilities for comprehensive analysis of local needs, or they may outsource. It is important to note all data collected is stored securely in relation with the Data Protection Act (2018).

The structure of a needs assessment will vary between commissioners, allowing for local flexibility. Key components should include the following:

1. Defining the needs assessment objectives – what does the needs assessment need to tell us to commission the most effective services?

- a. Barriers – What barriers may exist for victims when accessing services? For example, language, neurodiversity, disability.

- b. Victims’ voice – Has there been sufficient feedback from victims, service users and individuals with lived experience, from both those who have, and have not, engaged with the criminal justice process? This should include victims who are not currently accessing existing services, with engagement conducted in a trauma-informed way with appropriate aftercare. Consideration should also be given to compensating if done outside of service provision feedback.

- c. Resources and capacity of commissioners to complete a thorough needs assessment.

- d. Scope - Commissioners should also set the scope, i.e. consider what services are outside of the scope and may be commissioned by other partners.

Commissioners should ensure opportunities for all those impacted by crime to engage in consultations, and actively reach out to those from seldom heard, or less engaged communities. For example, a Safelives report on the experiences of blind and partially sighted domestic abuse victims found that the prevalence of abuse against these individuals was high, but those who had received support was very low, due to a number of barriers to seeking that support.[footnote 17]

Engagement with VCSEs can be crucial to understanding the local community, as these organisations can be the closest to service users and may be involved in advocating on their behalf. In Wales, PCCs engage where relevant and necessary, with the Welsh Council of Voluntary Action (WCVA). The WCVA, like the VCSEs, offers engagement opportunities with a range of voluntary agencies and services, and service users to provide effective and needs based services across Wales. Ensuring ongoing engagement with VCSEs can also encourage seldom heard groups to become involved in shaping local service provision. Smaller grassroots providers or community leaders are also likely to have specific expertise on issues affecting local communities.

West Midlands PCC – Support for small grassroots community organisations

West Midlands PCC and Victims’ Commissioner of the West Midlands ran an annual victims’ fund, which made available a proportion of the core victims’ budget to small grassroots community organisations. This funding has supported many organisations by providing seed-funding, enabling them to develop their services and go on to win larger contracts. Organisations were encouraged to develop their capacities in areas such as data collection and victim outreach. One organisation supported through this fund was Sikh Women’s Aid, which delivers one-to-one person-centred support to women and families from the Sikh/Panjabi community.

West Midlands PCC has also commissioned an organisation called DORCAS, which supports victims of female genital mutilation (FGM). DORCAS deliver FGM Awareness programmes in both primary and secondary schools, and their Born to Move/My Body Belongs to Me activity sessions are available for the under 5s. The PCC has funded costs towards counselling and support sessions, so that DORCAS can further develop these services.

2. Data – commissioners should consider the following data when collating a comprehensive needs assessment. Note, this is not an exhaustive list.

- a. Census data (including demographic data)

- b. Crime data

- c. Data from service providers – Data of victims who have accessed services

- d. Data from public sector services – Particularly looking at children’s social care, adult social care, housing and homelessness services and substance misuse services

- e. Health data – Information Sharing to Tackle Violence (ISTV), GP data, anonymised hospital and primary care data.

3. Reports – Evidence of need identified in Domestic Homicide Reviews[footnote 18], (DHRs) serious case reviews, HMICFRS reports on VAWG and child sexual exploitation reports for commissioners from the Child Sexual Exploitation Centre. This can also include reports which are issued by the Domestic Abuse, Victims’, Children’s, and Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioners’ offices.

4. Outreach – commissioners should consider who should provide evidence to support the needs assessments, and who can provide constructive feedback.

- a. Victims’ voice, in particular hearing from marginalised communities – as discussed in chapters 4 and 5.

- b. Working groups, boards, forums, and local community engagement groups.

- c. Local, regional and national subject matter experts – for example, if commissioning for children and young people services.

- d. Providers of services and the wider voluntary sector, including those who are not currently funded by the commissioner.

5. Evaluation and analysis of existing provision and gap analysis – including outcome information on existing provision. This can include services which sit within Local Authorities, Health and the VCSE sector that are not funded through government but through different funding streams.

2.1b Collaboration

The National Audit Office’s (NAO) Successful Commissioning Toolkit[footnote 19], highlights that needs assessments may be carried out in conjunction with other commissioners. Likewise, within the VFS aim to remove barriers to access, the following standard is identified: ‘A whole-system approach to commissioning’. To meet this standard, commissioners will ‘work with other commissioners and agencies in their area to agree what is needed locally and to ensure different agencies who may be supporting individuals do so in a sensitive and joined up way – taking account of requirements as part of any relevant statutory duties. This will differ depending on the service and local circumstances, and the Duty to Collaborate will also impose requirements for commissioners. Partnerships should include Police and PCCs, local authorities, ICBs, and other local commissioners, agencies, and providers.’ Working in collaboration or co-commissioning is further mentioned in chapter 3.

2.1c Engagement with victims

Commissioners must engage with victims to understand what support they would like to access, what their experience of accessing support has been like, and how they originally engaged with services. Whilst it can vary, engagement with victims may be initiated through service providers or engagement groups. It is also important to obtain the views of children who have or may need to access services. Commissioners should follow safeguarding processes which may involve parents, guardians or other advocates who can speak to, or on behalf of, the child, including child specific ISVAs and IDVAs.

Merseyside PCC – Lived experience focus groups

Merseyside PCC hosted a series of lived experience focus groups with women across Merseyside to inform a delivery plan to tackle Violence against Women and Girls (VAWG). Hosted in independent, safe, and confidential environments, these sessions were an opportunity to hear from women across the region, where they shared their views and experiences of the police and criminal justice process. Alongside capturing the views of individuals with lived experience, the PCC hosted a region-wide summit at which more than 80 knowledgeable professionals working directly with victims and survivors of VAWG were brought together to share their expertise, identify best practice, and help drive work forward. The feedback from this extensive consultation process informed a series of survivor-led actions and a commitment between the Merseyside PCC, and local leaders through the delivery plan.

2.2 Plan

Engagement with service providers

Most organisations that commissioners fund will belong to the VCSE sector as registered charitable organisations. Engaging with these organisations can increase understanding of:

- what services have to offer as potential providers of public services (and as potential partners in a financial relationship with commissioners);

- whether there is any scope for specialist service providers to work together to provide services. This would be in the context of consortia partnerships and sub-contractual arrangements;

- the maturity of the market, whether there is any scope or necessity for capacity building to improve service sustainability;

- key issues in the sector and gaps to current provision.

Whilst engagement with service providers should occur at the beginning of the commissioning process, it should be an ongoing activity. It is understood that the concerns of commercial advantage can limit engagement but there are methods of co-production, and engagement prior to the design stage that will allow for engagement that do not impact on procurement guidance.

Durham PCC – Victims’ Champions

Durham PCC appointed three Victims’ Champions, one each for Crime, Domestic Abuse and Anti-Social Behaviour. The Victims’ Champion for Crime engages with victims to learn of their ‘lived experience’ through their criminal justice journey. Emerging themes, with case studies and further research, inform policy, planning and the commissioning of services for victims.

Examples of current research include:

- The difficulties of successfully progressing through the criminal justice system for victims with a cognitive impairment.

- The retraumatising of victims of rape and serious sexual offences due to initial over-listing and repeated re-listing of cases.

- The difficulties encountered in getting to, and being at court, such as transport, childcare and the upfront financial costs.

Victims of crime can often feel they have been victims of the criminal justice process too. Both Durham Constabulary and the Office of Durham’s Police and Crime Commissioner have written ‘victim impact assessments’ into their respective governance statements, to ensure key decisions are assessed for their potential impact on victims.

2.3 Do

2.3a Procurement of services and arrangements with service providers

After the needs assessment, commissioners should map local provision as far as possible to understand existing services. The services are then planned, and a service specification is produced. Commissioners should also consider the most appropriate procurement method.

There are several commissioning approaches which include,

- Contracts with providers for goods and services

- Co-commissioning with other partner agencies

- Grant awards and agreements for specific organisations/service

- Funding opportunities for organisations to bid to deliver particular projects

When considering which providers to commission and how to do this,

- Consideration should be given to the service, project, or initiative to be delivered, the funding available, the outcomes to be achieved, other similar services that may be in place and how these are being funded.

- Commissioners will need to decide which method of commissioning services is the most suitable and likely to provide the best value for money, engaging with the appropriate stakeholders to ensure there is a non-biased approach.

- Commissioners should consider the Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012[footnote 20] The Social Value Act requires commissioners to consider broader social, economic, and environmental benefits to the area when making commissioning decisions. Commissioners should require a social value consideration in tender opportunities. For example, consider service providers that employ local people or support local charities, and in doing so create an additional social value for communities.

- Commissioners should ensure there are robust due diligence checks in place to review things like providers’ safeguarding policies and whistleblowing policies.

- Commissioners are also encouraged to consider the suitability of organisations to provide specific services, such as looking at their accreditation statuses.

- When considering grant agreements, service providers must demonstrate that they are not solely reliant on the funding given by the commissioner.

2.3b Procurement

Procurement and tendering should be conducted in a fair, open and transparent manner, allowing for public scrutiny of all aspects of expenditure and delivery. Procurements can be advertised on the national public sector supplier portal BlueLight Commercial, where providers can register as suppliers.

Example of the procurement process as noted by Avon and Somerset PCC[footnote 21]:

- The procurement will be managed using the BlueLight eTendering Portal.

- Providers can register as a supplier on BlueLight and search under tender reference for the OPCC.

- Providers will have approximately ten weeks to draft their tender submissions from the opening of the tender before submitting final bids through the BlueLight portal.

- There will be a period allocated for tender clarification questions where bidders can submit questions, via the BlueLight tendering portal.

- All bid responses will have their responses to Statement of Requirement Questions evaluated and will have a total Weighted Quality Score for each aspect of the process.

- This figure will then be used in the “Cost Per Quality Point” calculation. Social value will be included in the Quality criteria with bidders asked to express the social value they propose to offer during the lifetime of the contracts.

- The evaluation will be undertaken by a mixed panel of evaluators with tender submissions evaluated in accordance with published marking guidelines and weighting criteria. Evaluation panels will include subject matter experts as required to assess proposals against the specification, including victims. Avon and Somerset PCC utilise an external organisation, TONIC, to support this.

Alongside this option, there are a number of procurement processes commissioners can choose such as:

- Open tendering: allows any organisation to submit a tender to supply the service that are required. This can be done as a single stage or as Competitive Procedure with Negotiation which allows the department to hold dialogue and/or negotiations with bidders on various aspects of the procurement.

- Single sourcing: Where a particular service provider is chosen by the commissioner even when other providers, who offer the same service, are available.

- Two-stage procurement: where a service is initially appointed to provide some of the services, and then appointed to carry out the provision in a second stage.

- Direct Award: Depending on if the service can only be provided by a specific supplier, and there is clear reasoning to award the agreement/contract to them, then a direct award might be used. This tends to be for niche requirements. There should be consideration of scale, complexity, market maturity and timescales which determines the best approach. See Annex C for further signposting on legislation and regulations.

2.3c Grants and Contracts

A grant is the agreement for money to be paid to an individual or entity to fund activities that align with the commissioner’s policies and strategy for service provision. Grants should be considered when a project, service or action can be delivered quickly and effectively. Conditions of the grant will be issued that outline the specific conditions concerning use of the grant. Service providers will be required to provide performance data and progress reports. Requests for reports on how effective the grant has been, is proportionate to the service provided and the level of funding that has been allocated.[footnote 22] Grants are a useful way for a commissioner to fund an activity of a VCSE organisation that is in line with one or more of the commissioner’s objectives. The grant agreement with the provider will set out the purposes for which the grant is to be used, for example to assist victims of crime to cope and build resilience, and the expenditure which may be covered by the grant. Most grants will define requirements for accounting how the funding has been used and the repayment of any surplus funding.

Grants can be considered, but not limited to, the following circumstances[footnote 23]:

- To provide some one-off funding arrangements.

- Where the application for funding meets a clear objective in PCC’s Police and Crime Plan.

- To support the development or continuation of a strong provider network in the voluntary/community sector.

- Predominately used to support community and voluntary groups where formal contracts are unsuitable and not appropriate.

A contract is an agreement for money to be paid to specified services/party for the purchase of products (assets or goods) or activities (services or works). In law a contract requires an offer and a corresponding acceptance; a consideration (meaning an exchange of payment or something else of value) and an intention to create legal relations. Currently requirements are set out in the Public Contracts Regulations 2015 but will be replaced by the Procurement Act 2023 which comes into effect on 1st October 2024. Both the Regulations and the Act set out remedies, including damages, for unsuccessful bidders who successfully challenge contracts which have not been lawfully awarded. It should be noted that for the procurement of health services, not including other goods and services procured by the NHS, the Public Contracts Regulations 2015 no longer applies and is instead governed by the NHS Provider Selection Regime[footnote 24] which was introduced by the Health and Care Act 2022[footnote 25].

When entering into a contract with providers for goods and services, commissioners should act in line with the Public Contract Regulations 2015. This involves, testing the market in some form, discussed in the ‘understand’ section; agreeing to a service specification; and entering a contractual relationship to meet those requirements. The approaches that can be used are at the discretion of local commissioners and will be proportionate to the value of the contract, length of contract, and available procurement frameworks.

Services may vary and switch between grants and contracts at the end of each cycle.

| Contracts | Grants |

|---|---|

|

Positives: Commissioners have greater control over the funds spent. A legally enforceable agreement. Specific targets can be identified and monitored to ensure high service performance. |

Positives: Relatively flexible means of funding service provision with a range of grant sizes and length. Commissioners provide the funds and service providers take ownership of the activities. Commissioners can still monitor performance. More flexible with regards to changes to service and specification. |

|

Disadvantages: Depending on the value of the contract, it can be a lengthy procurement process. It can exclude smaller service providers due to capability. Most, though not all, contracts have a profit element to the payment and consideration, which may not always be appropriate. |

Disadvantages: There can be high levels of competition. Not legally binding in the same way as contracts, but terms can be defined, and termination provisions can be included in grant agreements. Risk of non-compliance between funds being awarded and spent. |

2.3d Multi-year funding

Commissioners are also encouraged to pass on any multi-year funding commitments that they receive from their funding source to their provider organisations. This can ensure that services benefit from the increased certainty and sustainability which comes with multi-year funding agreements. Commissioners can also commission for longer periods based on assessment of risk, and often implement break clauses into contractual agreements.

2.4 Review

2.4a Monitoring performance

Once services have been commissioned, the effectiveness of the services must be regularly reviewed between the commissioner and the provider. The process for this should be clear from the outset of the grant or contract, and success will be measured against agreed outcomes. Commissioners should have regular outcome monitoring meetings with service providers.

As part of contractual arrangements with any commissioned service providers, robust reporting requirements should be implemented as part of the service delivery requirements and specification. Several data requirements are outlined in the VFS, as such a set of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) should be agreed with providers following the contract award.[footnote 26] Commissioners are encouraged to consider local strategies and blueprints to develop a common set of core KPIs for their services to benefit from standardised reporting and performance metrics.

Commissioners should also include a range of quantitative and qualitative measures to monitor performance including risk and needs assessment completed, demographic data captured and referral metrics both quantitative and feedback from victims.

Commissioners should receive regular reporting data from their commissioned services, as this will provide a measure for the demand of the service in a given area. This data should provide commissioners with an idea of where there are gaps or potential duplication of services.

Commissioners are encouraged to use the baseline metrics which were set out in the VFS for reporting, to build a consistent evidence base of the demand for victim support services.[footnote 27] This data will be asked from commissioners in government reporting.

Through regularly measuring performance, commissioners can understand the effectiveness of the service and implement changes during the contracting timeline. This can be done during the commissioner and service provider’s outcome monitoring meetings where risks and outcomes are considered.

Sussex PCC - Funding Network

Sussex PCC created the Safe Space Sussex Funding Network to provide a level of due diligence and quality assurance across the local sector and those who are eligible to receive funding.

We recognised that with the PCC receiving more responsibility for commissioning local services and the local VCSE sector growing, we needed a consistent way of not only quality-assuring but measuring outcomes and outputs to holistically see the impact of funding. Additionally, we identified that the sector was working in isolation, with limited funding and cross-cutting different crime types. We needed organisations to work in partnership and knowledge share.

As part of the Network, providers must sign up and evidence a variety of requirements across the following categories: organisation, staff and management, information sharing, safeguarding, monitoring and evaluating, partnership working and financial management. The PCC additionally hosts training and networking sessions for those on the Network to increase knowledge across the sector, share specialisms and enhance partnership working. As one of the requirements, providers must also sign up to monitor any funding provisions against an outcome monitoring framework, allowing the PCC to view and monitor the difference the services are making across the county.

The network now joins up regularly on funding bids, and frequently exchanges knowledge which includes ‘swapping’ of training to upskill staff. This has greatly improved working relationships. Sussex PCC can showcase the outcomes across the sector and consider where more improvement could be made, or where some injection of funding could be utilised best.

2.4b Evaluating service impact

Victims’ service providers are expected to demonstrate that the service they are providing is of good quality and achieving the desired outcomes. As noted in the VFS, data and feedback should be gathered from victims throughout their engagement with the support service, and not just at the start or end of their support. Service providers should measure quality of service against the core outcomes as outlined in the VFS[footnote 28] - see Annex B for more detail.

2.4c Decommissioning

As services are commissioned, embedded and improvements demonstrated, new services or a change of provider may be required. Where necessary, the PCC will reduce services or decommission services that are no longer needed or when at the end of a commissioning cycle and in preparing for a new cycle. The decommissioning process usually begins in the final year of funding. Commissioners should maintain transparency and communicate to service providers at the earliest opportunity to support them through the project closure period whilst being mindful of keeping victims’ experience at the forefront.

There are several guidelines that commissioners should share with service providers at the beginning of the last year of funding. Such as:

- Keeping a watchful eye on referral numbers month on month, and depending on the victim intervention type, be practical on when to stop taking new referrals.

- Depending on the support being delivered, be practical on when to start victim disengagement with the service/caseload closure.

- Service providers should consider re-profiling the delivery to build resilience. This could mean regularly promoting peer support work in terms of both group activities and a 1-2-1 buddy scheme. Signpost victims to similar local services throughout the whole year.

- During the final year it is important that providers are financially aware, providing accurate and timely spending reports to the commissioner. Therefore, in support of this, commissioners should request a move to quarterly financial monitoring.

- As with each year, and via a directive from the government, any underspend must be returned to the commissioner in a timely manner.

- To assist with controlling spending, when a funded position becomes vacant, service providers should discuss with the commissioner before deciding to recruit – it could be that an internal secondment is an option to support the remaining delivery of services for the rest of the year.

- Service providers should also be given the option to not accept the final year of funding, or to end the agreement early if that fits better with their delivery model, existing caseload, and length of interventions.

2.5c Timeline of Activity example (Cambridgeshire OPCC)

The following outlines the decommissioning timeline, and activity between the commissioner and the service provider.

Quarter 1: April - June

- Discuss decommissioning timelines and guidelines

- Discuss how message of closure programme will be conveyed to victims and staff

- Agree strategy for supporting victims, encouraging peer support work throughout the year

- Risk register established

Quarter 2: July - September

- Review referral numbers, with a discussion on how to limit/reduce numbers every month

- Agree on the current financial position on underspending

Quarter 3: October - December

- Set expectations on year-end data and funding recovery if applicable

- Service providers to consider website messages with communications sent to the sector and partners

Quarter 4: January - March

- Hold the year-end review early around February to account for service wrap-up

- Year-end outcome data needs to be collected

- Deliver an accurate report on expenditure

- Administer any signature protocol and closure documentation

3. Collaboration and co-commissioning

For some services or types of support, it may be appropriate to collaborate on or co-commission services for victims with other local agencies.

VFS standard - A whole system approach to commissioning

One of the national commissioning standards introduced as part of the VFS was encouraging a whole system approach to commissioning. This section offers some further guidance on how this can be achieved, and the partners that may be involved.

3.1 What is a whole system approach to commissioning?

A whole system approach to commissioning includes making sure that all commissioners with some responsibility for commissioning support services are involved when devising a local strategy to support victims of crime.

Victims can often have complex and intersectional support needs which cannot be met by one organisation alone. This can include needing help to access financial or housing support or requiring therapy or medical care. Where children are involved, it may be the case that they require a specific support service tailored to their needs, or whole family support is required.

Collaborating and co-commissioning services can help to provide a holistic journey through a service (or services) for victims and ensure that the right support is provided from the outset. A whole system approach can include many different methods of working together, including collaboration – where partner agencies, the local community, and victims themselves can come together to discuss and agree a support journey – through to co-commissioning services – where two or more commissioners come together to provide a specific service for their local area(s).

Co-commissioning is a more involved process than collaboration and includes commissioners coming together to jointly provide a service or multiple services in their local area(s). Co-commissioning can take many forms and will often have a ‘lead’ commissioner who oversees the process – this is usually the agency best placed to manage the service being commissioned, based on factors such as most resource to oversee the process or more expertise in responding to that crime type, or an existing relationship with the service provider.

Where a service is co-commissioned, all commissioners who are involved will agree monitoring and finance arrangements for the service.

Bringing different commissioners and agencies together can lead to innovative ways of viewing and providing local victim support. This can include a public health approach[footnote 29] to criminal justice, focusing on prevention, and working closely with communities.

3.2 Benefits of a whole system approach

The benefits of closer collaboration and co-commissioned services include:

- A wide and varied range of expertise around the table, for example clinical commissioners who can bring a more health-focused approach to commissioning.

- More sophisticated referral pathways into services, and easier management of victims once they are in the support system.

- If pooling budgets, this can mean a larger overall funding pot for commissioning, which could in turn mean a larger service or more collaboration between multiple commissioned services[footnote 30].

- More support when it comes to overseeing and managing the contract or grant with the service provider, plus improved governance structures across the local area as relationships are developed between agencies. This includes easier routes to facilitate data sharing between commissioners.

- More coordinated review of service provision, meaning gaps can be identified across sectors (i.e. mental health or accommodation support for victims) and the complex needs of victims can be considered.

For victims, co-commissioned services can mean only having to tell their story once, instead of multiple times to different providers. This is especially welcome where a victim has complex needs and requires additional support from different sources – for example, mental health support as well as community-based or advocacy support.

Given these benefits, a whole system approach to commissioning victim support services should result in better overall outcomes for victims.

3.3 Collaboration and co-commissioning with Local Authorities

Local government – including county, district, borough, city, and unitary councils – are responsible for a range of vital services for people and businesses in their area. These include functions such as social care, schools, and housing.

Local authorities may use some of their funding to commission community-based support services for victims. Local authorities have a range of partnerships which contribute to the victim support landscape, and it is important that PCCs understand how these boards and partnerships function and where they can add value.

Norfolk PCC – Norfolk Integrated Domestic Abuse Service (NIDAS)

Norfolk PCC is lead Commissioner of NIDAS. The service is funded by the PCC and various local authorities in the county. The service is provided by a consortium of local and national charities. NIDAS is about creating a whole system approach to supporting survivors in communities, starting with the commissioning of the service, to integrating the support pathways through Norfolk‘s Early Help Structure, and drawing on community assets to support recovery.

The service is county wide, across seven districts, to help mitigate any postcode lottery to access support. There is a centralised triage and assessment team – one point of contact, so no victim or professional needs to navigate systems to access service. The service offers support to high and medium risk victims, with the same IDVA supporting that client as the risk changes. It includes direct support for children and young people (5-18) if their adult is or has been in the service.

NIDAS offers a rolling recovery programme so that when clients are ready, they can access this when they need it. Training for the workforces of the funding partners and management of the county’s Domestic Abuse Champion network (over 900 strong), builds the front line of early intervention to identify domestic abuse and guide people into NIDAS support at the earliest opportunity.

Funding has been invested into NIDAS to create resilience as well as the creation and development of a team of specialist IDVA’s. The specialist team of additional IDVA’s are dedicated to client groups who are seen to be hidden victims of domestic abuse, and who have unique barriers.

3.3a Community Safety Partnerships

PCCs and Community Safety Partnerships (CSPs) share many mutual priorities, including in crime prevention and support for victims.

CSPs were established in 1998, and are statutory partnerships which bring together councils, police, health, fire and rescue services, and probation services to work together in formulating and implementing strategies to tackle local crime in the area.

Under the Police Reform and Social Responsibility Act (2011)[footnote 31], PCCs must act in co-operation with CSPs and must have regard for their priorities when developing local strategy. CSPs bring together a valuable forum of partners, working on the principle that no single agency can address the root causes of crime and antisocial behaviour.

CSPs also have responsibility for coordinating DHRs. DHRs are reviews into the circumstances around a death following domestic abuse. The reviews are used to understand the circumstances surrounding the death, offer learning to local professionals, public bodies, and voluntary organisations, and raise awareness in the wider community on how to help victims of domestic abuse and prevent future deaths. DHRs can be valuable tools for commissioners to take learnings from and offer ways to improve the support available to domestic abuse victims.

3.3b Local Partnership Board

Under Part 4 of the Domestic Abuse Act 2021, tier one local authorities are required to set-up a multi-agency Local Partnership Board consisting of key partners with an interest in tackling domestic abuse and supporting victims and their children. This should include at least one representative of policing and criminal justice such as PCCs.

The Local Partnership Board should support local authorities by providing advice on: assessing the scale and nature of the needs of all victims and their children for support within safe accommodation; preparing and publishing a whole-area domestic abuse support in safe accommodation strategy; giving effect to this strategy by making commissioning and decommissioning decisions; monitoring and evaluating the effectiveness of the strategy; and reporting on progress to MHCLG.

MHCLG’s Statutory Guidance encourages local authorities to ensure their strategies for accommodation based domestic abuse support services are aligned with wider relevant strategies for DA and VAWG, community safety and victim support.

3.3c Health and Wellbeing Boards

Local authorities with adult social care and public health responsibilities in England are required to have a local Health and Wellbeing Board (HWB). These boards “provide a forum where political, clinical, professional and community leaders from across the health and care system come together to improve the health and wellbeing of their local population.”[footnote 32] The boards have a core statutory membership which includes a representative from local ICBs, but they have local discretion to invite additional members who are not required to sit on the board, such as PCC representatives or other criminal justice agencies.

HWBs have a duty to prepare Joint Strategic Needs Assessments (JSNAs) and Joint Health and Wellbeing Strategies (JHWSs). Local authorities and health bodies have “equal and joint duties” to prepare these as part of the HWB. JSNAs prepared and developed by HWBs assess the current and future health and social care needs of their local community, and as part of this process can consider how to meet the needs of victims of crime. The JHWSs follow the needs assessments and set out the ways in which local agencies will meet the needs identified in the JSNAs.

Whilst not a statutory requirement for PCCs to attend these boards, it is encouraged that they do where possible. This allows all three commissioners with the most responsibility for victim support to consider the wider needs of victims, particularly where they may intersect with services such as mental health support.

3.4 Collaboration and co-commissioning with Integrated Care Systems, Partnerships and Boards

Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) are partnerships of health and care organisations that provide joined-up care and support to people in their local area. ICSs consist of two statutory bodies: Integrated Care Boards (ICBs) and Integrated Care Partnerships (ICPs).

ICBs have taken over from Clinical Commissioning Groups as responsible for commissioning the majority of health services, including services which victims may access such as mental health support. Sexual Assault Referral Centres (SARCs) continue to be commissioned by NHS England, with collaboration and input from police forces and PCCs.

ICPs bring together the ICB and other commissioners and partners to promote partnership arrangements. Many PCCs will already be a part of their local ICPs, who are responsible for producing the Integrated Care Strategy, a document which sets out how the area will offer health and wellbeing care and support. These strategies are supported by a Joint Forward Plan which provides the operational detail around how the strategy’s vision will be realised. These plans are published and reviewed at the start of each financial year. Under Section 25 of the Health and Care Act 2022[footnote 33], when developing their Joint Forward Plans, ICBs must “set out any steps that the ICB proposes to take to address the particular needs of victims of abuse (including domestic abuse and sexual abuse, whether of children or adults).”

Some areas may also have a Sexual Assault and Abuse Services (SAAS) Partnership board or network. These bring together national, regional, and local commissioners who are responsible for commissioning sexual assault and abuse services[footnote 34].

Some areas may have different or additional boards or partnerships which are already in place. PCCs are encouraged to utilise any group which is available to them, as these can be an effective way to ensure join-up between agencies, and across crime types.

Cambridgeshire and Peterborough PCC – Ensuring an equitable ISVA service

In 2020, Cambridgeshire PCC, two local authorities (with funding from public health budgets) and NHS England agreed to pool their ISVA funding and commission a single service.

Two local charities working in a consortium arrangement successfully bid for the five-year contract, which also included the wider rape and sexual violence emotional and practical support service. This partnership working has transformed the support available to victims and survivors of rape and sexual violence in the area.

A jointly developed Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) sets out the roles and expectations of both the ISVA service and officers from the Constabulary’s Rape Investigation Team (RIT). This ensures victims and survivors receive a seamless service from both agencies.

Through the MOU, the officers will offer all victims reporting to the police a referral to the ISVA service and will personally ensure that referral goes in through the single countrywide pathway. A duty ISVA will contact the victim within 48 hours to make an initial assessment and allocate a member of the team. Every effort will be made to ensure the same ISVA supports the victim throughout their journey through the criminal justice system, building strong and trusting relationships. The ISVA service and RIT officers liaise on a regular basis and provide updates to victims in a way that meets their needs.

3.5 Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise sector

The VCSE sector is independent of the Government, and refers to an incorporated voluntary, community or social enterprise organisation which services communities within England and is not-for-profit[footnote 35]. The sector includes charities, foundations, informal community groups, co-operatives, and not-for-profit businesses. Most victim service providers, such as community-based services, will belong to this sector.

As outlined in chapter 2, commissioners are encouraged to work alongside the VCSE sector when designing, developing, and commissioning services, as they have a lot of varying experience and can provide connections to communities that may be seldom heard.

Charitable Foundations can also be an invaluable partner when commissioning and delivering victim support services. They can offer everything from expertise in a specific area, to additional or match-funding to bolster a project. The APCC and the Association of Charitable Foundations (ACF) recently released guidance on how PCCs and charitable foundations can work together[footnote 36].

Commissioners should also consider engaging with the VCSE sector when looking for match funding, as organisations such as the National Lottery Community Fund or Comic Relief may be able to offer support.

3.6 Other agencies and partners

3.6a Collaboration and co-commissioning with probation - Restorative Justice

Restorative justice can be effectively co-commissioned between PCCs and Regional Probation Directors because it can benefit both victims and offenders. Victims who take part have reported increased levels of satisfaction with the justice system, and when targeted appropriately restorative justice reduces the likelihood of serious and persistent offending which benefits the wider criminal justice system and society.

Restorative justice is a process that brings those harmed by crime and those responsible for the harm into communication, so that they can play a part in repairing the harm and finding a positive way forward. Communication may take many forms - for some this may mean a victim meeting the offender face-to-face; for others, this could be communicating via letter, recorded interviews or videos.

There are no specific case types where there should be a blanket exclusion of the use of restorative justice. However, it should only be used in cases where both the victim and offender voluntarily agree to participate, and all parties, including facilitators and prison or probation practitioners, agree that it is safe and appropriate to proceed. There is good evidence of effectiveness in property-related or violent offence cases where there is a clear identifiable victim, but limited evidence in cases of hate crime, extremism, domestic abuse, and sexual offending, where there could be risk of re-victimisation.

Delivery of restorative justice in cases of this nature may raise potential risks to one or more parties involved, which will need careful consideration by agencies with responsibility for supporting the victim(s) or supervising the offender(s).

When commissioning restorative justice services, we encourage commissioners to review the relevant guidance such as the national occupational standards and the guidance available for agencies and restorative justice practitioners, to consider the appropriate offer and risk management procedures within commissioned services. Service providers should have effective initial risk assessments in place to identify risks before any process starts and that dynamically assess risk on an ongoing basis. The Restorative Justice Council’s Practice Guidance (2020) provides a useful non-exhaustive list of factors that may be relevant to an assessment of risk to participants in a restorative process and possible mitigating measures. For serious and complex cases involving offenders in prison or on probation His Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS) will also need to consider any risks to parties and that this is likely to affect potential volumes of appropriate cases.

Hampshire & Isle of Wight PCC - Restorative Justice

Hampshire and Isle of Wight PCC funds Restorative Solutions to deliver the Restorative Justice Service across Hampshire and Isle of Wight. It aims to ensure that Restorative Justice is accessible to every victim of crime and anti-social behaviour across the whole force area regardless of where the victim lives, the offence committed against them and the time that has elapsed since the offence was committed (subject to the willing participation of the offender). Restorative Justice is also accessible to every offender across Hampshire and the Isle of Wight. This is subject to an appropriately trained/registered practitioner being assured of the motive behind the desire, the willingness and free informed consent of the victim to take part and a robust assessment to ensure there is no further risk of re-victimisation.

The service is predominantly resourced through funding devolved to the PCC by the MoJ for services that support victims of crime. However, the PCC has provided additional funding to ensure there is a focus on prevention and reducing re-offending. This enables offenders to self-refer and Police to refer low-level cases of neighbourhood dispute, where there is no clear harmed or harmer, however a restorative approach may prevent the escalation of the situation, a crime being committed, and a victim being created.

Additional funding has also been provided by South Central Probation. This enables offender-initiated referrals from HMPPS, training for staff and further exploration of the use of Restorative Justice in responding to conflict within the secure estates across Hampshire and the Isle of Wight.

A multi-agency Restorative Justice Joint Working and Quality Assurance Group (chaired by the OPCC) oversees the delivery of Restorative Justice for youth and adult offenders in Hampshire and Isle of Wight. It led the development of a local strategic policy for the delivery of Restorative Justice in cases of domestic and sexual abuse. The policy was co-produced by the partnership and specialist VAWG providers to ensure that victims are not prevented from accessing Restorative Justice. It also sets clear expectations in terms of safeguarding to ensure that Restorative Justice will not re-victimise or re-traumatise the victim and that Restorative Justice Services will adopt a partnership approach to risk management with the victim being involved with and at the centre of all decisions.

3.6b Education

Commissioners should also look to work closely with education settings – this can include primary and secondary schools, universities, Pupil Referral Units (PRUs) and other groups or networks which have safeguarding responsibilities for children. Children and young people may disclose and receive support in educational settings, which should be linked into wider support structures to allow referrals to other services. The next section looks in more depth at specific services for children and young people.

4. Services for children and young people

4.1 Children and young people as victims of crime

Measuring the extent to which children and young people are victims of crime is difficult, because it is often hidden from view, may never be reported, or is not separated from data on adult victims of crime.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS), who administer the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW), report that the proportion of children aged between 10-15 years who were victims of crime in the year ending March 2023 was 9.8%[footnote 37]. In the year ending March 2019, the CSEW also estimated that approximately 8.5 million adults aged 18 to 74 experienced at least one form of child abuse before the age of 16[footnote 38]. Analysis from the Centre of Expertise on Child Sexual Abuse found that, despite making up only 20% of the entire population, children account for 40% of all victims of sexual offences[footnote 39]. The Children’s Commissioner estimates that 1 in 15 children under the age of 17 live in abusive households[footnote 40].

Children and young people can be the victims of many types of crime and will likely need additional or tailored support to help them to cope and build resilience to move forward with their daily lives. This support may necessarily look different from the support that adults receive, and may need to be provided via specific services for children and young people. It will consider the additional complex circumstances which affect children who are victims of crime, such as potential separation from family members or inability to understand what has happened to them. This section looks at what commissioners should consider with regards to victim support for children and young people.

4.1a Legislation regarding children and young people as victims

Following introduction of Section 3 of the Domestic Abuse Act (2021) in January 2022, children who see, hear, or experience the effects of domestic abuse, and are related to the victim or perpetrator, are now considered victims of domestic abuse within their own right. This includes in instances where the child was not present during the crime. The Duty to Collaborate within the Victims and Prisoners Act will set out the expectation that commissioners consider the specific needs of children when preparing their joint strategies, and when delivering advocacy services.

VFS standard – equitable access to services

All victims, including children and young people, should be able to access support regardless of any complex needs or barriers which they may face.

4.2 Designing services for children and young people

Whilst the commissioning process will follow that which was outlined in chapter 2, there are additional challenges that commissioners should consider when commissioning support for children and young people.

Commissioners should employ a ‘child first’ approach[footnote 41]. This means putting children at the heart of service provision, ensuring they are consulted in the design and commissioning of services, and recognising the distinct needs that children and young people have. These needs could include using age-appropriate language when discussing harms, working jointly with the non-abusive parent or guardian, or offering longer support sessions.

Active participation and engagement is a key tenet of Child First, and ensures children and young people have a voice in the services for them. Engagement can include outreach exercises in their local communities (utilising forums such as youth community groups), joining up with educational settings such as schools or colleges, or collaborating with children’s service providers in their area, who can assist with appropriate sessions for children and young people using their existing networks. Commissioners should pay due care and attention to the design and implementation of any consultation with child victims, to avoid re-traumatisation, and ensure all necessary safeguards are in place.

Once an understanding of the needs of children and young people in an area is established, services should be commissioned to meet those needs. Specific services for children and young people may, operationally, be completely standalone, or form part of a wider service that offers support to the whole family unit. Support may also include roles such as Child IDVAs, who are specifically trained to represent and support child victims of domestic abuse. Commissioners should commission trauma-informed services for children and young people, understanding that they are at risk of adverse experiences if they do not get the right support, which could continue to affect them later in life.

Where standalone services are not available in an area to children and young people, commissioners should consider encouraging other services to upskill their staff and ensure they are trained to meet the needs of younger victims, where they have the resource capacity to do so.

4.2a Wrap-around support

A whole system approach is crucial in supporting children and young people who are the victims of crime, as well as supporting the family, professionals, or community around them, given the specific needs outlined above.