Country policy and information note: sexual orientation and gender, Uganda, March 2025 (accessible version)

Updated 20 March 2025

Executive summary

Same-sex consensual sex for men and women is illegal. In May 2023 the Anti-Homosexuality Act was passed which provides for the death penalty for ‘aggravated homosexuality’ and criminalised the ‘promotion of homosexuality’. Same-sex marriage is also illegal. There are no specific laws regulating gender identity. The law allows for intersex people (which it describes as ‘hermaphrodites’) to register a change of sex.

Civil society groups advocating for and providing support to lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and people of other minority sexual orientations and gender identities (LGBT+) are able to operate but do so in an increasingly restrictive legal and civic space.

LGBT+ people are arrested and detained but convictions and imprisonment under the anti-LGBT+ laws remain uncommon.

Homophobia and transphobia are widespread. LGBT+ people experience discrimination, violence, verbal and sexual harassment, extortion and blackmail by community and family members as well as state actors. LGBT+ people also face discrimination in accessing housing, education, employment, and healthcare.

LGBT+ people form a particular social group.

A LGBT+ person is likely to face persecution.

Protection is not likely to be available.

Internal relocation is not likely to be viable.

Where a claim is refused, it is not likely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

Each case must be considered on its facts, with the onus on the person to demonstrate that they are at risk.

Assessment

About the assessment

This section considers the evidence relevant to this note – that is the country information, refugee/human rights laws and policies, and applicable caselaw – and provides an assessment of whether, in general:

- a person faces a real risk of persecution/serious harm by the state and or none state actors because of their sexual orientation and/or gender identify and expression

- the state (or quasi state bodies) can provide effective protection

- internal relocation is possible to avoid persecution/serious harm

- a claim if refused, is likely to be certified as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

This note provides an assessment of the situation of actual and perceived lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and people of other minority sexual orientations and gender identities (LGBT+). Sources often refer to LGBT+ people collectively, but the experiences of each group may differ. Where information is available, the note will refer to and consider the treatment of each group discretely.

Decision makers must, however, consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts.

1. Material facts, credibility and other checks/referrals

1.1 Credibility

1.1.1 For information on assessing credibility, see the instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status and the Asylum Instruction on Sexual identity issues in the asylum claim and Gender identity issues in the asylum claim.

1.1.2 Decision makers must also check if there has been a previous application for a UK visa or another form of leave. Asylum applications matched to visas should be investigated prior to the asylum interview (see the Asylum Instruction on Visa Matches, Asylum Claims from UK Visa Applicants).

1.1.3 Decision makers must also consider making an international biometric data-sharing check (see Biometric data-sharing process (Migration 5 biometric data-sharing process)).

1.1.4 In cases where there are doubts surrounding a person’s claimed place of origin, decision makers should also consider language analysis testing, where available (see the Asylum Instruction on Language Analysis).

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information on this page has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

The information on this page has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: not for disclosure – end of section

1.2 Exclusion

1.2.1 Decision makers must consider whether there are serious reasons for considering whether one (or more) of the exclusion clauses is applicable. Each case must be considered on its individual facts.

1.2.2 If the person is excluded from the Refugee Convention, they will also be excluded from a grant of humanitarian protection (which has a wider range of exclusions than refugee status).

1.2.3 For guidance on exclusion and restricted leave, see the Asylum Instruction on Exclusion under Articles 1F and 33(2) of the Refugee Convention Humanitarian Protection and the instruction on Restricted Leave.

Official – sensitive: not for disclosure – start of section

The information on this page has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: not for disclosure – end of section

2. Convention reason(s)

2.1.1 Lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and people of other minority sexual orientations and gender identities (LGBT+) form a particular social group (PSG) in Uganda within the meaning of the Refugee Convention.

2.1.2 This is because they share an innate characteristic or a common background that cannot be changed, or share a characteristic or belief that is so fundamental to identity or conscience that a person should not be forced to renounce it and have a distinct identity because the group is perceived as being different by the surrounding society.

2.1.3 Although LGBT+ people form a PSG, establishing such membership is not sufficient to be recognised as a refugee. The question to be addressed is whether the person has a well-founded fear of persecution on account of their membership of such a group.

2.1.4 For further guidance on the 5 Refugee Convention grounds, see the Asylum Instruction, Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

3. Risk

3.1.1 LGBT+ people are likely to face persecution or serious harm.

3.1.2 Same-sex sexual acts and same-sex marriages are illegal for both men and women. Same-sex sexual acts are proscribed in the Penal Code Act under ‘unnatural offences’ and ‘indecent practices’ and are punishable with up to life imprisonment. In addition, the Anti-Homosexuality Act 2023 (AHA 2023) criminalises same-sex sexual acts, with the death penalty imposed for ‘aggravated homosexuality’, and up to 20 years in prison for the ‘promotion of homosexuality’ (see Legal framework and Anti-Homosexuality Act, 2023).

3.1.3 The law does not recognise changes in gender. Trans and gender diverse people have been indirectly criminalised under the offences of ‘personation’ (false representation), public indecency and the criminalisation of consensual same-sex sexual acts. The law allows for intersex people (which it describes as ‘hermaphrodites’) to register a change of sex (see Legal framework).

3.1.4 LGBT+ people are arrested and sometimes prosecuted under the anti-LGBT+ laws but convictions and imprisonment are uncommon. LGBT+ people are also arrested and detained under other laws in the penal code although often no charges are made. Exact numbers of cases are limited amongst the sources consulted. The US State Department (USSD) observed that NGOs reported ‘numerous’ arrests of LGBT+ people but did not cite the source of this data. The NGO Human Rights Awareness and Promotion Forum (HRAPF) documented 103 cases and 168 persons who were arrested because of their sexual orientation and/or gender identity between June 2023 and December 2024. While another NGO, the Strategic Response Team (SRT), documented 69 arrests of 89 LGBT+ people between September 2023 and May 2024, 47 of these were under the AHA 2023. Neither HRAPF or SRT indicated what the eventual outcomes were of these arrests (see Legal framework and State treatment).

3.1.5 State officials, religious leaders and elements in the media used homophobic rhetoric which reinforced anti-gay sentiment (see Government officials, Media, Political leaders, Anti-LGBT+ actors use of social media and Religious leaders).

3.1.6 Societal homophobia and transphobia remain widespread and societal stigma pervasive. The 2021/22 Afrobarometer survey found that 94% of Ugandans would ‘somewhat dislike’ or ‘strongly dislike’ having a ‘homosexual’ neighbour; 97% said homosexuality was incompatible with their culture and religious norms and should remain illegal and 94% to 95% would report a family member, close friend, or co-worker to the police if they were involved in a same-sex relationship (see Societal attitudes).

3.1.7 There have been significant violations of LGBT+ rights, with a spike after the AHA was adopted in May 2023. The USSD noted that human rights activists refer to ‘numerous’ incidents of violence and harassment of LGBT+ people. The Ugandan NGO the Strategic Research Team reported 1,031 cases of human rights violations, which included 1,043 LGBT+ people who suffered 1,253 human rights violations and 1,228 perpetrators (state and non-state) between September 2023 and May 2024. The violations include forced evictions, violent attacks and threats of violence, outing, denial of services and family rejection. HRAPF documented 716 cases between June 2023 and October 2024 affecting a total of 912 LGBT+ persons targeted because of their sexuality. The UN’s High Commission for Human Rights noted in April 2024 that around 600 people were reportedly subject to human violations based on sexuality or gender identity since May 2023. Other sources also report LGBT+ people facing various violations including physical attacks, mob attacks, forced evictions, involuntary conversion therapies, corrective rape, forced marriages, doxing (making public identifiable information about a person, usually on the internet), outing and blackmail. Non-state actors were the main perpetrators, but state actors have also subjected people to abuse (see General treatment of LGBT+ people and Societal treatment).

3.1.8 LGBT+ people face widespread discrimination in accessing services such as housing, education, employment, and healthcare (see Access to services).

3.1.9 Although there are LGBT+ NGOs which provide assistance, they experience obstacles in advocating for and supporting LGBT+ people. These include attacks on premises and staff, police raids, harassment, evictions, and refusal of registration. NGO activities on behalf of the LGBT+ community are also criminalised under the AHA 2023 as ‘promotion of homosexuality’ (see Shelters and LGBT+ organisations).

3.1.10 In the country guidance case of JM (homosexuality: risk) Uganda CG [2008] UKIAT 00065, heard on 30 November 2007 and promulgated on 11 June 2008, the Asylum and Immigration Tribunal (AIT) held that:

‘(1) Although there is legislation … which criminalises homosexual behaviour there is little, if any, objective evidence that such is in fact enforced.

‘(2) Although the President and government officials have made verbal attacks upon the lifestyle of homosexuals and have expressed disapproval of homosexuality in the strongest terms, the evidence falls well short of establishing that such statements have been acted upon or would be provoked or should provoke in themselves any physical hostility towards homosexuals in Uganda.

‘(3) Although a number of articles have been published, in particular the Red Pepper article identifying areas where the gay and lesbian community meet and indeed identifying a number by name, the evidence falls very short of establishing that such articles have led to adverse actions from either the authorities or non-state actors and others in the form, for example, of raids or persons arrested or intimidation.

‘(4) Although it is right to note a prevailing traditional and cultural disapproval of homosexuality, there is nothing to indicate that such has manifested itself in any overt or persecutory action. Indeed, there was evidence placed before us that a substantial number of people favour a more liberal approach to homosexuality.

‘(5) A number of support organisations exist for the gay and lesbian community and their views have been publicly announced in recent months. There is no indication of any repressive action being taken against such groups or against the individuals who made the more public pronouncements.

‘In general, therefore, the evidence does not establish that there is persecution of homosexuality in Uganda.’ (paragraphs 170 and 171)

3.1.11 However, as set out above, the available evidence indicates the situation for gay men and LGBT+ people generally is significantly worse than described in the evidence before the Tribunal in JM (which also predates the Supreme Court’s judgement in HJ Iran and HT Cameroon, given on 7 July 2010, establishing the correct approach for considering claims based on sexual orientation). There are therefore very strong grounds supported by cogent evidence to depart from the existing caselaw.

3.1.12 If a LGBT+ person is not ‘out’ about (or conceals) their sexual orientation and/or gender identity consider why. If it is because they fear persecution or serious harm and this is well-founded, they are likely to require asylum.

3.1.13 For further guidance on assessing risk, see the Asylum Instructions on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status and the Sexual identity issues in the asylum claim and Gender identity issues in the asylum claim.

4. Protection

4.1.1 Where the person has a well-founded fear of persecution or serious harm from the state, they are unlikely to be able to obtain protection.

4.1.2 A person who has a well-founded fear of persecution or serious harm from a rogue state and/or a non-state actor is unlikely to obtain effective protection because the state is able but not willing to do so given that same-sex sexual acts are criminalised (see State protection).

4.1.3 LGBT+ people distrust law enforcement officials and often do not seek assistance for fear of arrest or reprisal, and when victims do report assaults the police are reported not to act (see State protection).

4.1.4 For further guidance on assessing state protection, see the Asylum Instructions on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status and the Sexual identity issues in the asylum claim and Gender identity issues in the asylum claim.

5. Internal relocation

5.1.1 Internal relocation is unlikely to be viable.

5.1.2 The state exercises control throughout the country and societal homophobia and transphobia, manifest in acts of violence and discrimination against LGBT+ people, are widespread (see General treatment of LGBT+ people, State treatment, Societal attitudes, Societal treatment and Protection).

5.1.3 For further guidance on internal relocation and factors to be taken into account see the Asylum Instructions on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status and the Sexual identity issues in the asylum claim and Gender identity issues in the asylum claim.

6. Certification

6.1.1 Where a claim is refused, it is unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

6.1.2 For further guidance on certification, see Certification of Protection and Human Rights claims under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 (clearly unfounded claims).

Country information

About the country information

This section contains publicly available or disclosable country of origin information (COI) which has been gathered, collated and analysed in line with the research methodology. It provides the evidence base for the assessment.

The structure and content follow a terms of reference which sets out the general and specific topics relevant to the scope of this note.

This document is intended to be comprehensive but not exhaustive. If a particular event, person or organisation is not mentioned this does not mean that the event did or did not take place or that the person or organisation does or does not exist.

The COI included was published or made publicly available on or before 31 January 2025. Any event taking place or report published after this date will not be included.

Decision makers must use relevant COI as the evidential basis for decisions.

7. Demography

7.1.1 The World Bank estimated that as of 2023 Uganda had a population of around 48.5 million [footnote 1].

7.1.2 The Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS), which collects, analyses, and publishes statistical information [footnote 2], preliminary results of the national population and housing census conducted in May 2024 put the population of Uganda at 45.9 million[footnote 3].

7.1.3 There is no information in the sources consulted on the size of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersex (LGBTI) population in Uganda (see Bibliography).

7.1.4 Ingham and others January 2025 noted ‘Uganda’s religious heritage is tripartite: indigenous religions, Islam, and Christianity. About four-fifths of the population is Christian, primarily divided between Roman Catholics and Protestants (mostly Anglicans but also including Pentecostals, Seventh-day Adventists, Baptists, and Presbyterians). About one-eighth of the population is Muslim. Most of the remainder practice traditional religions …’[footnote 4]

8. Legal framework

8.1 Constitution and penal code

8.1.1 The US Department of State (USSD) in their 2023 Country Report on Human Rights Practices (USSD 2023 human rights report) noted: ‘The law prohibited discrimination based on sex, among other categories, but did not explicitly prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, or sex characteristics … The law did not recognize LGBTQI+ individuals, couples, or their families … The law did not address so-called corrective rape of LGBTQI+ persons.’[footnote 5]

8.1.2 The International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA), an international organisation campaigning for lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersex human rights[footnote 6] (ILGA database no date report) noted with respect to Uganda : ‘The Constitution of Uganda does not explicitly include “sexual orientation”, “gender identity”, “gender expression” or “sex characteristics” as protected grounds of discrimination. To the best of ILGA World’s knowledge, laws in force in Uganda do not offer protection against discrimination based on “sexual orientation”, “gender identity”, “gender expression” or “sex characteristics” in the provision of goods and services.’[footnote 7]

8.1.3 The penal code has provisions effect criminalise same-sex sexual relationships

- section 145 on ’unnatural offences’ states: ‘Any person who - (a) has carnal knowledge of any person against the order of nature; (b) has carnal knowledge of an animal; or (c) permits a male person to have carnal knowledge of him or her against the order of nature, commits an offence and is liable to imprisonment for life.

- section 146 states: ‘Any person who attempts to commit any of the offences specified in section 145 commits a felony and is liable to imprisonment for seven years.

- section 148 on ‘indecent practices’ states: ‘Any person who, whether in public or in private, commits any act of gross indecency with another person or procures another person to commit any act of gross indecency with him or her or attempts to procure the commission of any such act by any person with himself or herself or with another person, whether in public or in private, commits an offence and is liable to imprisonment for seven years.’[footnote 8]

8.1.4 On 23 October 2024 Amnesty International (AI), an international human rights organisation, published a report which documented the impact of technology-facilitated gender-based violence (TfGBV) on LGBT+ people’s and organisations’ digital presence and behaviour. The report is based review of social media posts, academic literature, reports by civil society organizations and United Nations agencies and mechanisms as well as 64 interviews conducted in Uganda between June 2023 and February 2024 with LGBT+ individuals, and organisations, human rights defenders and other civil society organisations working on gender and sexuality, technology, and human rights[footnote 9] (AI October 2024 report). The report observed:

‘Section 148 criminalizes “indecent practices” which constitute “gross indecency”, without specifying what “gross indecency” entails and thereby allowing for very broad interpretations. The Amendment to the Section introduced in 2000, to include “any persons” within its purview allows acts between women to be criminalized as well.

‘Besides the provisions directly criminalizing consensual same sex relations, other provisions of the Penal Code Act are used to prosecute [lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and queer/questioning] LGBTQ persons, encompassing a wide range of actions and behaviours. These include provisions on public nuisance (Section 160), being idle and disorderly (Section 167) and being rogue and vagabond (Section 168).

‘Even though there are no direct laws criminalizing transgender and gender diverse people, criminalization of consensual same-sex sexual conduct, sex work, impersonation, public indecency, and public order provisions have been used to subject transgender and gender diverse people to police harassment, arrest, and detention.’[footnote 10]

8.1.5 Article 31 (2a) of the constitution amended 5 January 2018 states: ‘Marriage between persons of the same sex is prohibited.’[footnote 11]

8.2 Gender recognition

8.2.1 The undated ILGA database noted that a person can change their name:

‘Article 36 of the Registration of Persons Act (2015) allows adults to change their name through a deed poll. Applicants are required to publish their intention to change their names in the Official Gazette at least one week before they approach a registry office with the necessary forms. Nevertheless, it should be noted that this law is not trans-specific. While the law technically places no limitations on who can apply, trans and gender-diverse people are at greater risk of targeting by authorities under the oppressive laws currently in force.’[footnote 12]

8.2.2 The same source observed: ‘There is no specific law in Uganda permitting legal gender recognition, though Article 38 of the Registration of Persons Act (2015) provides for “a child born a hermaphrodite” [sic]’ who “through an operation, changes from a female to a male or from a male to a female and the change is certified by a medical doctor” to be given a new gender marker.’[footnote 13]

8.2.3 The USSD 2022 human rights report noted:

‘Legal gender recognition was not available, and the law did not provide the option of identifying as “nonbinary/intersex/gender nonconforming.” Transgender persons could officially change their names, but the law did not provide an option for changing gender markers on official documents.

‘The country did not permit individuals to change their gender identity marker on legal and identifying documents to bring them into alignment with their gender identity. The law also did not provide the option of identifying as “non-binary/intersex/gender non-conforming.” Human rights activists reported that transgender persons could officially change their names, but government officials blocked them from changing their gender marker on official documents. One individual, however, Cleopatra Kambugu, legally changed her gender identity marker to female in 2021.’[footnote 14]

9. Anti-Homosexuality Act, 2023 (AHA)

9.1 Offences and penalties

9.1.1 A November 2023 report by ILGA (ILGA November 2023 report) noted:

‘On 26 May 2023, the Anti-Homosexuality Act (2023) was signed into law … Section 2 of the Act criminalises any person who “performs a sexual act or allows a person of the same sex to perform a sexual act on him or her” and imposes a penalty of life imprisonment for such acts and 10 years’ imprisonment for any attempt to commit such acts.

‘Moreover, Section 3 prescribes the death penalty for “aggravated homosexuality” in cases where the individual convicted is a “serial offender” (which includes anyone with a prior conviction for engaging in same-sex sexual acts between consenting adults). Additionally, the death penalty is also mandated when “the person against whom the offense is committed contracts a terminal illness” [this was repealed by the constitutional court in April 2024]. According to the Act’s definitions, this provision could be applied to impose capital punishment if one of the individuals involved contracts HIV as a result of the sexual act. Furthermore, the death penalty could potentially be applied when one of the adults involved is a person with a disability [this was repealed by the constitutional court in April 2024] , or is elderly, regardless of their ability to consent.

‘Minors face three years’ imprisonment if convicted of homosexuality under Section 4 of the law. [footnote 15]

9.1.2 The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office travel advice for British Citizens travelling to Uganda, updated 6 February 2025, noted:

‘In May 2023, Uganda brought in the Anti-Homosexuality Act 2023. This act introduces harsh prison sentences, and the death penalty in some cases, for same-sex sexual activity. There are also severe penalties for promoting LGBT+ rights.

‘Sexual activity with someone of the same sex carries the punishment of life imprisonment.

‘Offences classed as “aggravated homosexuality” carry a sentence up to the death penalty. “Aggravated homosexuality” is defined as sexual activity with someone of the same sex who is:

- a person aged 17 or under

- a person aged 75 or above

- a relative or someone under your care

- disabled or suffering from mental health issues

- a person who is unconscious or under the influence of medicine or other substances that impair their judgement

- under duress or misrepresentation

- threatened or intimidated

‘A person who has a previous conviction of homosexuality or related offences can be charged with aggravated homosexuality for subsequent offences.

‘Promoting or supporting homosexuality carries up to a 20-year prison sentence. This includes, but is not limited to:

- encouraging or persuading someone to perform a same-sex sexual act or anything that is an offence under the act

- publishing, printing, broadcasting by any means, information that promotes or encourages homosexuality

- providing financial or other support that encourages homosexuality or the normalisation of acts prohibited by the act

‘Some of the language in the law is vague and open to interpretation, and it remains unclear how this law will be implemented. The law could affect those who are exercising their freedoms of expression, peaceful assembly and association to show support for LGBT+ people and rights.’[footnote 16]

9.2 Legal challenges against the AHA

9.2.1 On 18 December 2023 the BBC reported that rights groups were challenging the AHA, 2023 in Ugandan courts. According to the report, the rights groups had urged judges to strike down the law, claiming it infringed on the rights to equality and dignity. Meanwhile, the government defended the law in the Constitutional Court, arguing that it upholds traditional family values[footnote 17].

9.2.2 A 3 April 2024 Ugandan Judiciary news release stated:

‘The Constitutional Court has today delivered its decision … and declared that the Anti Homosexuality Act of 2023 complies with the Constitution of Uganda except in only four aspects …

‘The Constitutional Court of Uganda has nullified Sections 3(2)(c), 9, 11(2)(d) and 14 of the Anti-Homosexuality Act, 2023 for contravening the Constitution of Uganda, 1995 … The nullified Sections had criminalised the letting of premises for use for homosexual purposes, the failure by anyone to report acts of homosexuality to the Police for appropriate action, and the engagement in acts of homosexuality by anyone which results into the other persons contracting a terminal illness.’[footnote 18]

9.2.3 The Human Dignity Trust, a UK-based organisation working globally to use strategic litigation to defend the human rights of LGBT people[footnote 19], noted in its Uganda profile page updated on 4 December 2024:

‘On 3 April [2024], the Ugandan Constitutional Court dismissed a legal case challenging the constitutionality of the Anti-Homosexuality Act 2023 (AHA). In a unanimous decision, the Court upheld the constitutionality of all but 4 provisions of the AHA, and held that the individual rights to self-determination, self-perception and autonomy had to be balanced against the “societal right to social, political and cultural self-determination.” The Court found that the “uniqueness” of Uganda’s Constitution required the Court to consider Uganda’s socio-cultural norms in any constitutional challenge …

‘The provisions that the Court struck down as unconstitutional included the “duty to report” suspected acts of homosexuality to the police and allowing the use of premises for any offence under the AHA. The Court also struck down a provision that imposed the death sentence for transmission of HIV, which was found to violate Ugandan’s right to health.’[footnote 20]

9.2.4 The table below provides a summary of main offences and penalties under the AHA, 2023[footnote 21] following the Constitutional court judgement of 2 April 2024:

| Section | Offence | Penalty |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | Act of homosexuality | Life imprisonment |

| 2 | Attempted homosexuality | Up to 10 years imprisonment |

| 3 | Aggravated homosexuality | Death penalty |

| 3 | Attempted aggravated homosexuality | Up to 14 years imprisonment |

| 4 | Child convicted of homosexuality or aggravated homosexuality | Up to 3 years imprisonment |

| 8 | Child grooming | Life or up to 20 years |

| 9 | Knowingly allow premises to be used for homosexuality | Annulled |

| 10 | Prohibition of marriage between persons of same sex | Up to 10 years imprisonment |

| 11 | Promotion of homosexuality (individual) | up to 20 years imprisonment |

| 11 | Promotion of homosexuality (legal entity) | Up to fifty thousand currency points [One currency point is equivalent to 20,000 shillings); or suspension of license for 10 years; or cancellation license |

| 13 | Failure to disclose of conviction sexual offence under AHA to child care employer | Up to 2 years and termination of employment |

| 14 | Duty to report acts of homosexuality | Annulled |

| 15 | False sexual allegations | Up to one year imprisonment |

10. State and societal attitudes

10.1 Government officials

10.1.1 In 2023, GATE, an international advocacy organisation working towards justice and equality for trans, gender diverse and intersex communities[footnote 22], published a report, ‘Impact of anti-gender opposition on the trans and gender diverse (TGD) and LGBTQI movements’. The survey was conducted online and was open to participants from 26 July 2022 to 1 November 2022, with the questions covering respondents’ experiences over the previous 12 months. The data in the report covers the period from July 2021 to July 2022 (GATE 2023 report). With respect to Uganda 3 valid responses were received from ‘respondents affiliated with unregistered collectives that work with TGD communities.’ The report noted:

‘Respondents report that some [anti-gender] AG actors in Uganda are in government (MPs and ministers), that AG actors have coordinated communication with each other, and that the government rarely investigates alleged crimes committed by these actors. Moreover, respondents claim that the government financially supports AG actors. 1 Respondent states that the government is the main AG actor in the country. AG actors target cis women, migrants, religious minorities, LGBTQI, TGD, and intersex communities, and use sex education, “family values”, and “western ideas” as their main discursive topics to spread and gain support for their agenda. Respondents report that AG groups are growing in terms of the number of people supporting them on social media, and more people are participating in their events and providing them with more funding, political power, and connections, thereby increasing their ability to impact policies.’[footnote 23]

10.1.2 On 9 October 2022, the Uganda Radio Network (URN), an independent news agency that supplies news articles and programs to over 80 radio stations and other media platforms in Uganda[footnote 24], reported President Yoweri Museveni stating at the 24th annual national prayer breakfast which brings together political, religious, and other leaders from the continent:

‘“The preacher from Holland told you about respecting our heritage, the positive points in our heritage. We have been having pressures from some of these groups, who say that there are two ways of life … there is the normal way and the parallel way of the homosexuals and so on … but this is not our interpretation.”

‘He explained that such things are a deviation from normal and that this perception cannot be changed by any pressure from outside Africa …

‘He wondered why acts of homosexuality are publicized and commended the keynote speaker, Prof. Christiaan Alting, the President of the International Theological Institute for encouraging Africans to resist any pressure from Western countries that is against the culture.’[footnote 25]

10.1.3 On 1 February 2023, Geofrey Kabyanga, the Minister of State for Information Communication Technology and National Guidance said during a TV debate about LGBTQ rights: ‘“It [homosexuality] is not something we should see emerging and we just keep quiet … We should start fighting it as fast as possible. It is a bad habit that is coming up which we must stop as early as possible. It is a big problem in schools. Therefore, we shouldn’t keep quiet about it.”’[footnote 26]

10.1.4 On 16 March 2023, Voice of America (VOA), part of the US Agency for Global Media providing news and information[footnote 27] reported that President Yoweri Museveni described gay people as “deviants” and called for an investigation into homosexuality during a state of the nation address before lawmakers. President Museveni is quoted saying: ‘“The homosexuals are deviations from normal. Why? Is it by nature or nurture. We need to answer these questions … We need a medical opinion on that. We shall discuss it thoroughly … Western countries should stop wasting the time of humanity by trying to impose their practices on other people”…’[footnote 28]

10.1.5 On 3 April 2023, The Guardian (UK) reported:

‘The Ugandan president, Yoweri Museveni, has called on African leaders to reject “the promotion of homosexuality”…

‘Speaking on Sunday, Museveni said homosexuality was “a big threat and danger to the procreation of human race [sic]”.

‘He said: “Africa should provide the lead to save the world from this degeneration and decadence, which is really very dangerous for humanity. If people of [the] opposite sex stop appreciating one another then how will the human race be propagated?”

‘His comments followed a two-day inter-parliamentary conference held at State House in Entebbe on “family values and sovereignty”, attended by MPs and delegates from 22 African countries …

‘Museveni praised Ugandan MPs for passing the anti-gay bill [of 2023] and vowed “never to allow the promotion and publicisation of homosexuality in Uganda, stressing that it will never be tolerated”.’[footnote 29]

10.1.6 On 1 June 2023 Reuters reported:

‘Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni has defended signing one of the world’s harshest anti-LGBTQ laws … saying it was needed to prevent LGBTQ community members he said were “disoriented” from “recruiting” others …

‘”The signing is finished, nobody will move us,” Mr Museveni said during a meeting with lawmakers …

‘Mr Museveni told his party’s lawmakers that before signing the law he had consulted widely to try to determine whether homosexuality was genetic and had been persuaded by experts that it was not, describing it instead as “psychological disorientation”.

‘”The problem is that, yes, you are disoriented. You have got a problem to yourself. Now, don’t try to recruit others. If you try to recruit people into a disorientation, then we go for you. We punish you,” he said.

‘”But secondly, if you violently grab some children and you rape them and so on and so forth, we kill you. And that one I totally support, and I will support.”’[footnote 30]

10.1.7 The AI October 2024 report noted:

‘In the Ugandan context, misinformation and disinformation campaigns often portray LGBTQ people as being influenced by a Western imperial agenda, as “un-African”, as incompatible with Christianity and Islam, as “a threat to Ugandan culture and society”, and as “sexual predators”, particularly interested in recruiting children into their sexual practices. The use of the latter, in particular, has been a harmful stereotype used to create moral panic, and significantly sway the Ugandan public, leading to severe harassment, violence and discrimination against LGBTQ persons. Public officials have also engaged in spreading disinformation targeting LGBTQ people. A case in point is Thomas Tayebwa, the Deputy Speaker of the Ugandan Parliament, whose tweet conflating homosexuality with child abuse.’[footnote 31]

10.2 Politicians

10.2.1 On 1 November 2022, The Independent (Uganda), a privately owned weekly newspaper[footnote 32], reported:

‘Uganda’s delegation to the joint parliamentary Assembly of the Organisation of the African, Caribean, and Pacific States and the European Union led by Deputy Speaker of Parliament Thomas Tayebwa, has stated that it will oppose plans to make them adopt and adapt to homosexuality.

Tayebwa said Uganda is deeply concerned over coercive and persistent calls to the African, Caribbean, and Pacific – ACP States by the EU, and partners to adopt homosexuality.

‘Tayebwa says that Uganda demands a broad definition of the issue of human rights because the Post-Cotonou agreement has hidden clauses around human rights, especially those relating to sexuality, the promotion of homosexuality, and abortion. He explains that such practices are un-African in nature.’[footnote 33]

10.2.2 In a January 2023 post on X Thomas Tayebwa said: ‘I am getting painful stories about homosexuality and many people are dying in silence. It seems our schools have been infiltrated and recruitment centres are open. It’s extremely sad. Our children have been grabbed and sodomised. We must tackle this issue head on without fear.’[footnote 34] On 1 February 2023, MP Ojara Mapenduzi , an opposition leaning independent MP, stated during a TV debate about LGBTI rights that ‘[homosexuality] is an attack on our norms, principles and practices.’[footnote 35]

10.2.3 On 6 March 2023, Parliament Watch, which monitors and reports on the work of the Uganda parliament[footnote 36], MP Asuman Basalirwa when moving a Private Member’s Bill titled the Anti-Homosexuality Bill, 2023, that seeks to prohibit same-sex relationships described homosexuality as ‘a cancer eating up the world’ and that ‘Homosexuality is a human wrong that needs to be tackled through a piece of legislation.’[footnote 37] Basalirwa told parliament, ‘… there is a need to improve the Penal Code Act, which he argued was enacted by British colonialists to prohibit recruitment, promotion, and funding of same-sex practices because the vice threatens the continuity of the family, the safety of children, and the continuation of humanity through reproduction.’[footnote 38]

10.2.4 Parliament Watch also noted that ‘Sarah Opendi, the Tororo District Woman MP seconded the motion and called upon the enforcement bodies such as the Police and NGO Bureau to ensure that homosexuality is not promoted. According to the same report, Anita Among the House Speaker ‘warned legislators against accepting bribes from the promoters of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex, and Queer (LGBTIQ+) agenda with a view of frustrating the Bill, noting that the House will vote physically on the matter to expose those who are against the country’s anti-homosexuality position. ‘“It’s our children who are suffering because of homosexuality. Time for lamenting is over. The western world says they are assisting us; we don’t want their assistance if they are going to destroy our morals and cultural beliefs,” Among said.’[footnote 39]

10.2.5 On 8 May 2023 Mamba online, a South African website which reports on LGBTI-related news[footnote 40], stated:

‘… MPs in Uganda have demanded that a tax be imposed on adult diapers because they believe that they are primarily used by gay men. They also argued that not doing so would be “promoting homosexuality” …

‘The Value Added Tax (Amendment) Bill, 2023 recommended taxing children’s diapers but exempting adult diapers. The Finance Committee opposed the taxation on adult diapers on the basis that they are used by elderly individuals and adults with medical conditions.

‘Some MPs, however, argued that all diapers should be taxed as the tax exemption would benefit members of the LGBTIQ+ community …

‘“We just passed the [Anti-]Homosexuality Bill here, and you know for a fact that the biggest number of people who use diapers for adults are actually homosexual people,” MP Aisha Kabanda reportedly said. “So, when you say diapers for adults, you are going to benefit, to a big extent, the homosexuals.”

‘MP Agnes Kirabo agreed, telling her colleagues that “These adult diapers could be a result of homosexuals. If we do not tax them, we are going to be promoting homosexuality.”

‘The legislators ultimately approved the bill’s tax on all diapers, rejecting the proposal to exempt adult diapers.’[footnote 41]

10.2.6 On 4 January 2024, the Independent (UK) reported:

‘A well-known gay rights activist in Uganda who was stabbed by unknown assailants this week attributed the attack to what he described … as a growing intolerance of the LGBTQ+ community fueled by politicians.

‘The climate of intolerance is being exacerbated by “politicians who are using the LGBTQ+ community as a scapegoat to move people away from what is really happening in the country,” Steven Kabuye said in an interview from a hospital bed on the outskirts of Kampala … Kabuye is the executive director of the advocacy group Colored Voice Truth to LGBTQ …’[footnote 42]

10.3 Religious leaders

10.3.1 On 29 March 2022, Erasing Crimes 76, a news site that focuses on information relating anti-LGBTI laws and attempts to repeal them[footnote 43], reported:

‘Human rights activists in Uganda have launched a new campaign to end religious inspired homophobia …

‘Faith and church leaders are some of the most influential people in social, economic, political, and moral debates that shape society’s perceptions of LGBT people and communities.

‘… the political alignment of anti-LGBT faith leaders has resulted in the passage of laws that criminalise the existence of LGBT people, thus escalating violent attacks, homelessness, and unemployment.

‘Anti-LGBTI religious messages are amplified through radio, television and social media (Internet). Religious leaders and institutions play a large role in Uganda’s media, including religiously affiliated TV stations.’[footnote 44]

10.3.2 On 16 February 2023, the Daily Monitor, an independent Ugandan daily newspaper[footnote 45], reported:

‘The Inter-Religious Council of Uganda (IRCU) [an indigenous, national faith-based organization uniting efforts of religious institutions to jointly address issues of common concern[footnote 46] has vowed to do everything possible to have the anti-same-sex Bill returned to Parliament, as one of the measures to tackle the spread of homosexuality, especially in schools.

‘Addressing a joint media briefing at the offices in Kampala yesterday, the clerics said the lack of a stringent enabling law to tackle the vice is currently fuelling the Lesbian, Gay Bisexual Transgender Intersex, Queer and others (LGBTIQ)+) movements in the country, adding its high time they are stopped.

‘“Parliament had passed the Anti-Homosexuality Bill which the president accented [sic] to and became law in 2014, but some people went to court and nullified it. But it (law) is still our stand and as religious leaders, we urge government and his excellence the president that if it means bringing it back that law, we are in support because that law will bury the LGBTQ practice in Uganda” the Mufti of Uganda, Sheikh Shaban Ramadhan Mubaje said.

‘He added: “We also call upon the legislature to join hands so that this law is passed to protect Ugandans from this vice.”’[footnote 47]

10.3.3 On 23 February 2023 the Daily Monitor reported that several religious leaders across multiple dioceses condemned homosexuality as a global threat targeting the younger generation, as well as a sin, evil and against God’s design for procreation[footnote 48]. In a 30 March 2023 report the Daily Monitor stated: ‘The Catholic Church in Kampala has condemned homosexuality as sinful and must be fought by all followers … “We shouldn’t condone what the church takes as evil, so homosexual tendencies and acts according to the teachings of the Catholic Church are sinful and Jesus came to fight sin. So if we are fighting immorality that’s fine, but you should know that Jesus came to fight sin but did not fight a sinner,” Archbishop Ssemogerere said.’[footnote 49]

10.3.4 A March 2023 analysis of Uganda’s anti-gay bill by Kristof Titeca, an associate professor at the Institute of Development Policy, University of Antwerp, published by Africa Arguments, a pan-African platform for news, investigation and opinion[footnote 50] noted:

‘The religious communities became involved in the issue [in supporting the Anti-Homosexuality Bill of March 2023], and strongly amplified widespread anxieties … An important trigger was the 10 February announcement by the Ugandan Anglican Archbishop, Stephen Kaziimba, declaring his intention to break links with the Church of England. This followed the latter’s decision to allow priests to bless same-sex marriages and civil partnerships with Uganda’s archbishop stating that the “church is under attack” …

‘On 15 February 2023, the Inter-Religious Council of Uganda (IRCU) issued a statement, expressing concern about the increasing promotion of the LGBTI agenda in the country, and asking for a new and stringent law to address this. Addressing President Museveni directly, Archbishop Kaziimba implored “that the [Anti-Homosexuality Act] you signed previously against homosexuality should be revisited and signed again” …

‘Soon after, the Uganda Muslim Supreme Council called on all Muslims to hold peaceful demonstrations after the Friday sermon to express their disagreement with homosexuality, a vice which has “reared its ugly head targeting, especially young people”. The demonstrations were cancelled at the last minute, but still went ahead in some locations …

‘Popular singer, Jose Chameleon was forced to apologise for having embraced and kissed (on the cheek, that is) his brother - fellow singer Weasel - at a recent concert. It led to an uproar on social media after influential pastor Martin Ssempa demanded that Chameleon apologize, finding the kissing morally offensive, and asking the police to investigate.’[footnote 51]

10.3.5 On 30 May 2023, Africa Press, a pan African news platform, reported:

‘Leaders of Uganda’s biggest religious denominations yesterday chorused support for President Museveni’s decision to sign the Anti-Homosexuality Act into law, saying it will safeguard indigenous cultures, morals and children.

‘“We are grateful the President has signed into law the Anti-Homosexuality Act, 2023 … The LGBTQI-affirming countries have shown us the negative consequences. We thank the President for not surrendering to their threats and for protecting Uganda from their paths of self-destruction,” Church of Uganda Archbishop Samuel Kaziimba noted in a statement.

‘Rev Fr Dr Pius Male, the chancellor of Kampala (Catholic) Archdiocese, told this newspaper by telephone last evening that the biblical teachings against homosexuality are clear and should not be compromised.

“Thanks that he (Museveni) has done it [signed the Act into law],” he said.

‘The Deputy Mufti of Uganda, Sheikh Muhammad Ali Waiswa, while welcoming the presidential assent said “of course, we are not segregating others, but we are doing it in the interest of guarding our traditional values and morals” …

‘Archbishop Kaziimba said homosexuality is a challenge in Uganda because it is being imposed on the country by outsiders and “against our culture and our religious beliefs” under the guise of human rights.’[footnote 52]

10.4 Social attitudes

10.4.1 Freedom House, a US-based non-government organisation that monitors freedom and democracy across the world, in their Freedom in the World 2024 report covering events in 2023 (FH 2023 report) noted: ‘LGBT+ people face overt hostility from the government and society.’[footnote 53] USSD 2023 human rights report observed: ‘LGBTQI+ activists reported LGBTQI+ persons endured intense social pressure to change their sexual orientation.’[footnote 54]

10.4.2 On 2 February 2023, Daily Monitor, reported:

‘Ugandan authorities announced the removal of a rainbow painting from a children’s park following an uproar by parents who alleged that the “satanic” design promoted homosexuality in the largely Christian country. A local organisation had painted one of the park towers in Entebbe in rainbow colours as part of an effort to refurbish the site …

‘Emmanuel Mugabe from the national Parents Association of Uganda told this reporter that the tower’s rainbow colours were “satanic” and signalled an “invasion of homosexuality though manipulation of children’s minds”.’[footnote 55]

10.4.3 Equaldex, ‘a collaborative knowledge base for the LGBTQ+ … movement … Data is contributed, maintained, and community-verified by thousands of volunteer editors, with the help of reports from the general public’[footnote 56], reported on a Gallup poll conducted on 21 June 2023 which asked people in 123 countries including Uganda: ‘“Is the city or area where you live a good place or not a good place to live for gay or lesbian people?” 35% of the people in Uganda said it’s a good place. According to Equaldex, Gallup’s publicly available version of this poll did not include the per-country results of the “not a good place” answers.’[footnote 57].

10.4.4 Afrobarometer, a non-partisan, pan-African research network, which conducts public attitude surveys on democracy, governance, the economy, and society[footnote 58] published a report about Ugandan’s attitudes towards same sex relations in May 2023 based on a survey of 2,400 randomly selected adult Ugandans between 7 and 25 January 2022 (Afrobarometer May 2023 report)[footnote 59]. The survey assessed citizens’ levels of tolerance defined ‘as the ability or willingness to accept the existence of opinions, beliefs, or behaviours that one dislikes or disagrees with by asking them whether they would like it, dislike it, or not care if they had people from various groups as neighbours’[footnote 60]. The report noted:

‘… [M]ore than nine out of 10 (94%) [of Ugandans] say they would “somewhat dislike” or “strongly dislike” having a homosexual neighbour. These views have not changed significantly over the past seven years …

‘Ugandan adults of all ages and education levels overwhelmingly continue to express intolerance for same-sex, relationships, think they should be illegal, and are willing to report their own family member or close friend to the police if they engage in homosexual activity. Their level of intolerance for sexual difference is the highest among 37 African countries surveyed in 2021/2022.’[footnote 61]

10.4.5 The below chart by Afrobarometer shows levels of tolerance for people in same-sex relationships in Uganda from 2015 to 2022[footnote 62]. It shows that tolerance during this period averaged at 5% with lowest being in 2017 at 3 % and highest in 2019 at 8%.

Figure 3: Social tolerance: Uganda 2015-2022

| 2015 | 2017 | 2019 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Different religion | 95% | 95% | 94% | 93% |

| Different ethnicity | 93% | 90% | 88% | 85% |

| Immigrants | 78% | 76% | 82% | 74% |

| Homosexuals | 5% | 3% | 8% | 5% |

Respondents were asked: For each group of the following types of people, please tell me whether you would like having some people from this group as neighbours, dislike it, or not care. (% who say “strongly like”, “somewhat like” or “would not care”)

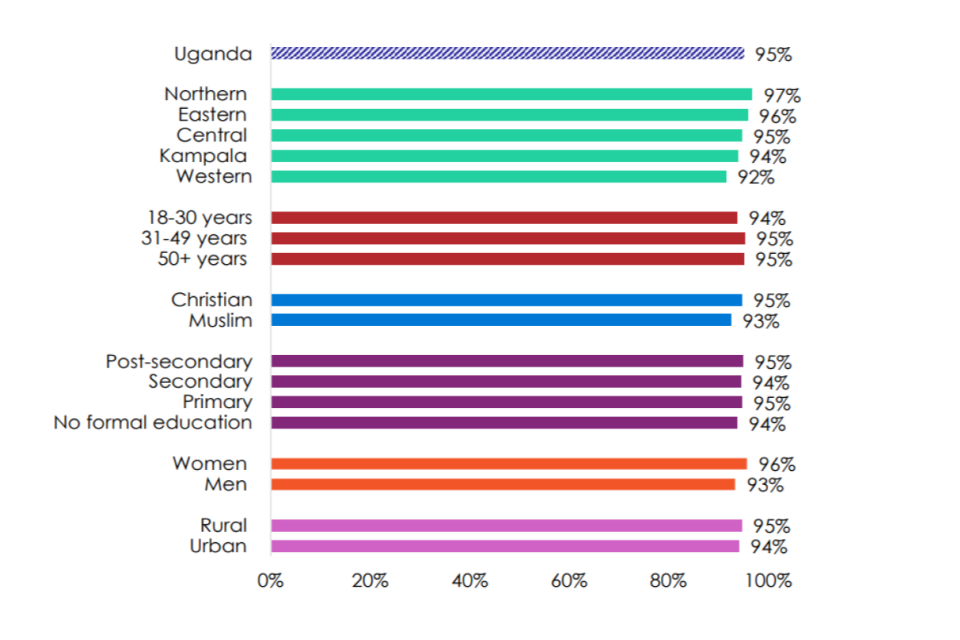

10.4.6 Afrobarometer produced the charts below showing intolerance for people in same-sex-relationships by demographic group. It shows that all demographic groups displayed high levels of intolerance that ranged from 92% to 97%, with the national average being 95%:

Figure 2: Intolerance for people in same-sex relationships by demographic group: Uganda 2022

| Demographic | % |

|---|---|

| Uganda | 95% |

| Northern | 97% |

| Eastern | 96% |

| Central | 95% |

| Kampala | 94% |

| Western | 92% |

| 18-30 years | 94% |

| 31-49 years | 95% |

| 50+ years | 95% |

| Christian | 95% |

| Muslim | 93% |

| Post-secondary | 95% |

| Secondary | 94% |

| Primary | 95% |

| No formal education | 94% |

| Women | 96% |

| Men | 93% |

| Rural | 95% |

| Urban | 94% |

Respondents were asked: For each of the following types of people, please tell me whether you would like having people from this group as neighbours, dislike it, or not care: Homosexuals? (% who say “somewhat dislike” or “strongly dislike”)

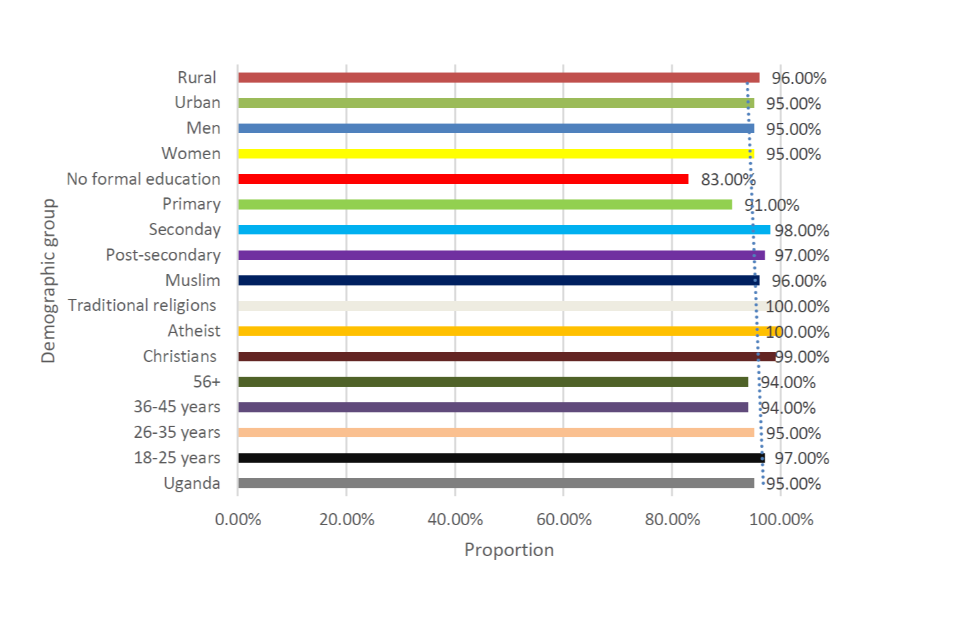

10.4.7 The Afrobarometer online data analysis tool (ODA) contains data sets from 39 African countries since 2019. The data set is searchable by country, survey round and survey question[footnote 64]. In the Round 10 Survey conducted in November 2024 in Uganda 2,700 adults were asked: ‘For each of the following types of people, please tell me whether you would like having people from this group as neighbours, dislike it, or not care: Homosexuals?’[footnote 65] The graph below has been created using the Afrobarometer data, which shows that intolerance towards people in same sex relationship in 2024 was the same as in 2022.

Intolerance for people in same sex relationships by demographic group

| Demographic group | Proportion |

|---|---|

| Rural | 96% |

| Urban | 95% |

| Men | 95% |

| Women | 95% |

| No formal education | 83% |

| Primary | 91% |

| Secondary | 98% |

| Post-secondary | 97% |

| Muslim | 96% |

| Traditional religions | 100% |

| Atheist | 100% |

| Christians | 99% |

| 56+ | 94% |

| 36-45 years | 94% |

| 26 - 35 years | 95% |

| 18-25 years | 97% |

| Uganda | 95% |

10.5 Media including social media

10.5.1 On 2 March 2023, Erasing 76 Crimes reported that a television debate on government owned Uganda Broadcasting Corporation entitled ‘The LGBTQ Debate: An attack on our social fabric’ revealed ‘the show[‘]s, bias against LGBT people.’[footnote 66]

10.5.2 On 23 March 2023, Edge Media Network, a network of local Lesbian, Gay Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) news and entertainment publications in the world[footnote 67] reported that: ‘Anti-gay sentiment in Uganda has grown in recent weeks amid press reports alleging sodomy in boarding schools.’[footnote 68]

10.5.3 In September 2023, the Strategic Response Team (SRT), consortium of five entities operating in Uganda that documents and coordinates community response and referral mechanisms to providers of safe shelter, legal, safety, and protection services to LGBTI people across Uganda[footnote 69] produced a report on the rights and well-being of LGBTI people between January to August 2023 (SRT report September 2023). It noted: ‘Frequently, the media sensationally reported cases of suspected LGBTIQ+ persons and called for their elimination.’[footnote 70]

10.5.4 The GATE 2023 report, which covered the period July 2021 to July 2022 stated with respect to Uganda:

‘Respondents indicate that [anti gender] AG actors actively engage in creating and spreading false information about TGD communities in Uganda, and mostly use local forum webpages and FaceBook, followed by TV and print media, Twitter, and webpages to communicate with their audiences. Respondents fully (2) or somewhat (1) agree that social media platforms are the main mobilization means for AG actors, and fully agree that these platforms are not sufficiently enforcing their community safety rules to prevent harmful and/or fake news from spreading, and/or violent actions from being planned. In the Survey, respondents did not report any pro-human rights posts being blocked on any social media platform.’[footnote 71]

10.5.5 In 2024 February Jakob Svensson, a professor of media and communications at Malmö University, Emil Edenborg, a professor of gender studies at Stockholm University and Cecilia Strand an associate professor at the department of informatics and media Uppsala University, published an article examining the visibility of LGBT+ activism in Uganda. The article is based on secondary sources and 28 interviews conducted in Kampala between 20th December 2021 and 17th January 2022. Interviewees included unaffiliated individuals with same-sex desires, individuals working for an LGBT + organisations and international donors/actors in the country[footnote 72] (Svenson and others 2024). The article observed:

‘Ugandan print and broadcast media have been reluctant to provide balanced coverage of human rights and LGBT + advocacy, at best and outright hostile at worst. Furthermore, with the Ugandan media landscape full of discriminatory dis/misinformation pertaining to LGBT + people, self-controlled digital media spaces play a crucial role in the community to become visible for distant others both inside and outside Uganda on their own terms. Social media platforms thus allow LGBT + activist and organizations to curate their visibility to support individual and/or organizational objectives. Digital spaces are vital arenas for the community to communicate and socialize, as well as to engage in mobilization and coordination of community activities. Digital spaces are, however, far from unproblematic. Social media platforms open for other types of harassment and human rights abuses and may, in some cases, even increase the LGBT + community’s vulnerability.’[footnote 73]

10.5.6 The AI October 2024 report noted with respect to social media:

‘Amnesty International found widespread derogatory and offensive language against LGBTQ people in Uganda, which dehumanized and, at times, encouraged violence against them, reinforced harmful stereotypes and biases, and in some cases led to physical acts of violence. The online attacks came from a range of different actors, including known people, unknown members of the public, religious and cultural leaders, as well as political leaders.’ [footnote 74]

10.5.7 The same source further noted:

‘Organizations working on human rights and rights of LGBTQ persons told Amnesty International that disinformation … is rampant in Uganda and has contributed to widespread homophobia and transphobia and increased support for government actions to criminalize and penalize LGBTQ persons and their allies through harsh penalties. Mass circulation of clips wrongly alleging people and organizations of “promoting homosexuality” has exposed them to homophobic and transphobic sentiments by the public and the state, putting their safety at risk.

‘… [M]isinformation and disinformation campaigns, often with the patronage of religious and political elites, has contributed to fostering a climate whereby harmful stereotypes, bias, prejudice and discrimination against LGBTQ people are repeatedly circulated on social media platforms.’[footnote 75]

11. General treatment of LGBT+ people

11.1 State and societal acts

11.1.1 This section includes information about human rights violations against LGBT+ people from sources that do not (clearly) distinguish between state and societal actors. In addition, sources often refer to LGBT+ people collectively but the experiences of each group may differ. For information about treatment attributed to particular actors, see the following sections.

11.1.2 The USSD 2023 human rights report observed: ‘Human rights activists reported numerous instances of state and nonstate actor violence and harassment against LGBTQI+ persons and noted authorities did not adequately investigate the cases.’[footnote 76]

11.1.3 FH 2024 reporting on events in 2023 noted: ‘LGBT+ people in Uganda are not represented in politics and face pervasive discrimination, which became more severe after President Museveni signed the AHA in May 2023.’[footnote 77]

11.1.4 Following the passing of the AHA 2023 the BBC reported on 24 March 2023:

‘In the weeks before the debate, anti-homosexual sentiment was prominent in the media, an activist who wanted to remain anonymous told the BBC. “Members of the queer community have been blackmailed, extorted for money or even lured into traps for mob attacks,” the activist said.

“In some areas even law enforcers are using the current environment to extort money from people who they accuse of being gay. Even some families are reporting their own children to the police.”’[footnote 78]

11.1.5 An April 2024 report by Human rights Watch (HRW), a non-government organisation that monitors human rights, on the Constitutional Court’s decision on the AHA 2023 noted:

‘Even before the introduction of the 2023 act, LGBT Ugandans had frequently faced discrimination, harassment, and physical attacks. The Ugandan authorities have banned LGBT organizations, and accused some of “promoting homosexuality” and luring children into homosexuality through “forced recruitment”…

‘After the law came into force in May 2023, local groups reported that LGBT people in Uganda were experiencing increased attacks and discrimination by both officials and other people. These included beatings, sexual and psychological violence, evictions, blackmail, loss of employment, online harassment, and denial of health care based on their perceived or real sexual orientation or gender identity.’[footnote 79]

11.1.6 A 30 May 2024 article, by Edward Mutebi, a human rights activist and the founder and executive director of Let’s Walk Uganda, an NGO that seeks to advance the rights and well-being of marginalized individuals[footnote 80] and published by Bond, a UK network for organisations working in international development, (Mutebi May 2024 article) stated:

‘The enactment of this discriminatory law [AHA, 2023] has not only stripped LGBTQ+ individuals of their inherent rights but has also perpetuated a climate of fear, persecution, and violence that has reached alarming levels …

‘The pain and suffering endured by LGBTQ+ people in Uganda under the Anti-Homosexuality Act cannot be overstated. Forced evictions have left many individuals homeless, while others have been subjected to blackmail, extortion, and unwarranted arrests simply for being who they are. The dehumanising practice of forced anal examinations and other forms of torture in police custody has become distressingly common, highlighting the harsh realities faced by LGBTQ+ individuals in the country.

‘Violent attacks on Human Rights Defenders (HRDs) and activists advocating for LGBTQ+ rights have further exacerbated the challenges faced by the community …’[footnote 81]

11.1.7 The SRT June 2024 report noted:

‘Although law [AHA 2023] became legally enforceable after the presidential assent on 20th May 2023; suspected, perceived and or known LGBTQ+ persons, organisations and allies faced immense challenges following the misleading campaigns, misinformation in the media with allegations of “promotion of homosexuality and recruitment of young persons into homosexuality” in spaces like schools. As a result, LGBTQ+ persons were subjected to violence and threats, denial of services such as access to justice and health services …

‘[From September to May 2024] … Known and/or perceived LGBTQ+ persons were arrested, tortured, beaten, exposed, including evictions and banishments, blackmail, loss of employment, and health service disruptions. This was sustained by frequent fake and false news shared on different platforms and a sustained campaign to paint LGBTQ+ persons as persons who are not only acting against African and religious morals but also as persons who are out there to recruit children into homosexuality, destroy society and cause some form of apocalypse in Uganda.

‘In the reporting period the Uganda Police, Landlords, Local Councils (LCs), and family members are among the top violators of rights. This category of people especially Landlords, Mobs and LCs were generally enforcing provisions of the AHA that required individuals to report cases of violations and not to allow tenants in their houses.’ [footnote 82]

11.1.8 The AI October 2024 report noted:

‘Amnesty International documented various violations of the right to privacy of LGBTQ persons in Uganda, including through practices such as outing, doxing, hacking of individual and organizational accounts, and accessing devices and data of LGBTQ persons without their consent.

‘Doxing involves revealing personal information, identifying documents or details about someone without their consent online, typically with malicious intent. This can include a person’s home address, real name, children’s names, phone numbers or email address. Outing refers to the disclosure, online or offline, of a person’s sexual orientation and/or gender identity or their HIV status, without their consent and in violation of their right to privacy. In the interviews conducted by Amnesty International, doxing frequently led to outing of LGBTQ persons as often their SOGIE status was not known to others outside the community …

‘Amnesty International found that both state and non-state actors (private individuals) have engaged in acts of revealing identifying personal information about LGBTQ persons with the aim of shaming and maligning their reputation.

‘A prominent LGBTQ organization told Amnesty International that outing is a common phenomenon in Uganda which has several deleterious consequences on LGBTQ people.’[footnote 83]

11.1.9 The same source added:

‘… In countries such as Uganda, where people are forced to hide their sexual orientation and/or gender identity and/or expression, for fear of prosecution, violence, and discrimination, blackmail and extortion is endemic.

‘Data and messages stored on people’s devices and social media accounts played a pivotal role in arming blackmailers with “evidence” of the person being LGBTQ or being associated with LGBTQ people and organizations …

‘Perpetrators ranged from ex-partners, other LGBTQ community members, clients, to unknown members of the public, as well as police authorities. In cases of blackmail by private individuals, state authorities not only failed to effectively investigate them, but were also responsible for creating an environment where these crimes can occur with impunity.’ [footnote 84]

11.2 Numbers of incidents

11.2.1 In April 2024 Volker Türk, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, noted: ‘Close to 600 people are reported to have been subjected to human rights violations and abuses based on their actual or imputed sexual orientation or gender identity since the Anti-Homosexuality Act was enacted [in May 2023].’’[footnote 85] The report did not provide details on how the figure was arrived at or what constituted a human rights violation.

11.2.2 In June 2024 the SRT published a report based on documented reports of violations and threats to LGBTQ+ persons in Uganda covering the between September 2023 and May 2024 (SRT June 2024 report). It noted:

‘A total number of 1031 cases were recorded [by SRT] in the period under review involving 1043 LGBTQ+ persons who suffered 1253 human rights violations and abuses documented. These involved forced evictions and loss of shelter, violent attacks and threatening violence, exposure and outing, leading to violation of the rights to equality and non discrimination, freedom from torture inhuman and degrading treatment, access to social services, family rejection, mental and physical health challenges, among others. 1,228 persons categorised as state and no[n] state actors were responsible for violating the rights of LGBTQ+ persons.’[footnote 86]

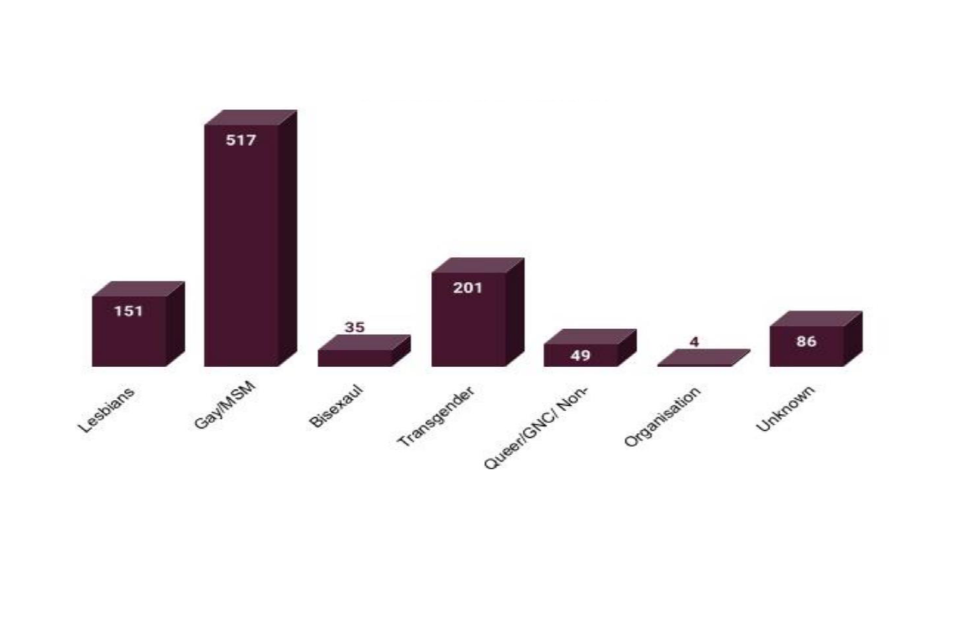

11.2.3 The same source noted that: ‘The most affected persons were gay men, followed by transgender women and lesbians. The graph below shows the most affected persons in the number of cases documented:

Victims’ categories

| Category | Number of cases |

|---|---|

| Lesbians | 151 |

| Gay/MSM | 517 |

| Bisexual | 35 |

| Transgender | 201 |

| Queer/GNC/Non | 49 |

| Organisation | 4 |

| Unknown | 86 |

11.2.4 The Human Rights Awareness and Promotion Forum (HRAPF), a non-governmental human rights advocacy organisation that seeks to promote respect and protection of human rights of marginalised persons and ‘most at risk populations’[footnote 88]publishes monthly reports of violence and human rights violations against LGBTI people compiled from cases handled by HRAPF’s network of lawyers and community paralegals. In its January 2025 report, HRAPF noted that: ‘In the first 19 months of the AHA 2023, a total of 1,485 cases involving LGBTIQ persons have been handled across the HRAPF legal aid network, of which 760 (51.2%) targeted LGBTIQ people on the basis of their sexuality, affecting a total of 967 persons.’[footnote 89]

11.2.5 The numbers of incidents for specific violations is presenting in below sections see sections on Evictions; Attacks and threats of violence, Arrests and harassment, Prosecutions

12. State treatment

12.1 Arrests and harassment

12.1.1 The March 2023 African Arguments article noted ‘… LBGTI people are routinely harassed: there have been … numerous arrests … there have been raids on LGBT-friendly bars and shelters, leading to numerous arrests. The Ugandan gay community has also witnessed the return of forced anal examinations (a form of cruel and degrading treatment, which could constitute torture).’[footnote 90] In a May 2024 report HRW noted that ‘Over the years, Ugandan police have … forced some detainees to undergo anal examinations, a form of cruel, degrading, and inhuman treatment that can, in some instances, constitute torture.’[footnote 91]

12.1.2 The USSD 2023 HR report observed that ‘Although the law prohibited arbitrary arrest and detention, security forces often arbitrarily arrested and detained persons, especially opposition supporters, activists, demonstrators, journalists, and LGBTQI+ persons.’[footnote 92]

12.1.3 The USSD 2023 HR report also noted:

‘LGBTQI+ activists reported police arrested numerous individuals on the basis of their sexual orientation or gender identity and subjected many to forced anal exams, a medically discredited practice with no evidentiary value that was considered a form of cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment and could amount to torture. LGBTQI+ activists under the umbrella association Convening for Equality reported 18 instances of forced anal exams by police between January and August. On August 23, the prosecutor charged a spa manager in Njeru Magistrate’s Court with homosexuality, promotion of homosexuality, and knowingly allowing her premises to be used for homosexuality, with potential sentences of life in prison, 20 years in prison, and seven years in prison, respectively. Police arrested the accused after complaints from the spa’s neighbors [sic], who reported the accused featured her workers in same-sex pornography video shoots. On August 22, prosecutors charged Elisha Mukisa, a prominent “ex-gay” activist, and his partner with homosexuality in breach of the AHA. The prosecution stated Mukisa lured his partner into same-sex relations and offered him accommodation in a government-sponsored apartment. Police detained the men and conducted anal exams on both. The court remanded the two to prison.’[footnote 93]

12.1.4 The SRT May 2024 report covering the period September 2023 to May 2024 observed:

‘A total 69 of the arrests were documented. 47 of these are arrests and charges were under the AHA while 22 were with no charges. Of those charged under the AHA 31 were charged with homosexuality, 11 with aggravated homosexuality, 3 attempted homosexuality and 2 promotion of homosexuality. In 22 cases there were no charges preferred and these were documented as arbitrary arrests. These involved 89 persons in total. It should be noted that there are various arrests and charges of sodomy, possession of narcotics, inciting violence among others that have not been included in the cases reported here. The cases preferred under other existing laws such as the Penal Code Act cap 120 and under Control of Narcotics and Psychotropic Substances Act, to mention Computer Misuse Act. 33 forced anal examinations were recorded by police. These violate the right to health and other multiple human rights enshrined in the Constitution including right to liberty, freedom from discrimination, freedom from torture inhuman and degrading treatment.’[footnote 94]

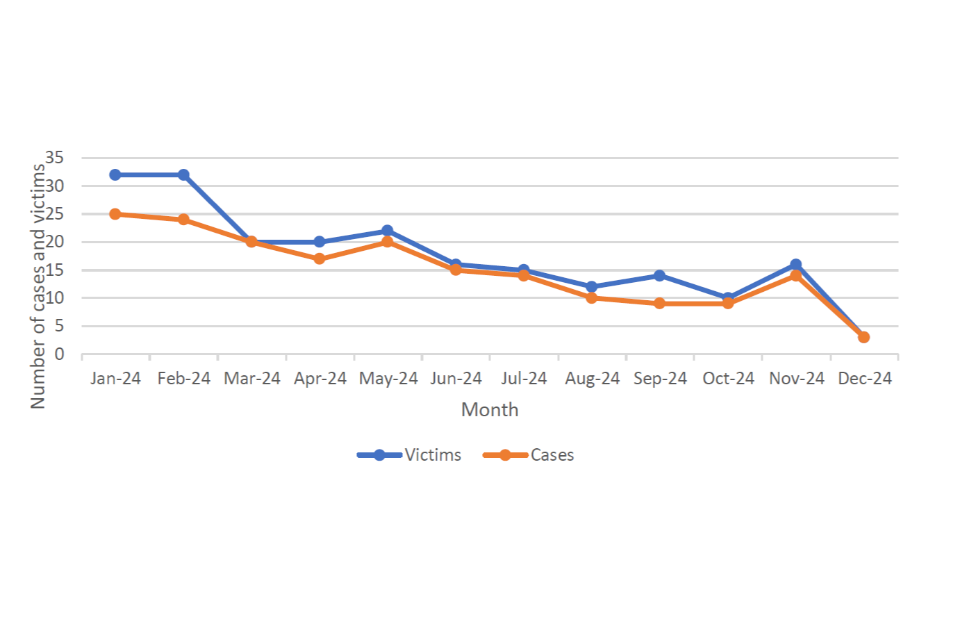

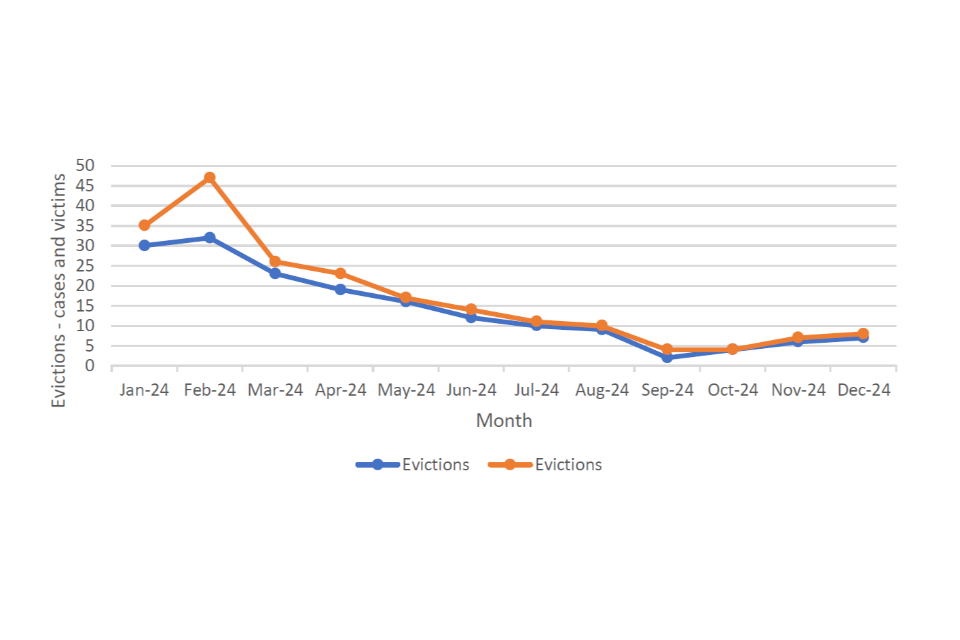

12.1.5 HRAPF January 2025 report noted that from June 2023 to December 2024 it documented 103 cases and 168 victims of sexual orientation and gender identity or expression (SOGIE) related arrests. Of these 65 cases and 109 victims were reported between January and December 2024. Those arrested were charged with homosexuality under the AHA 2023, unnatural offences, having carnal knowledge against the order of nature and personation under the penal code[footnote 95]. The below table shows trends in arrests from January to December 2024 based on HRAPF documentation.

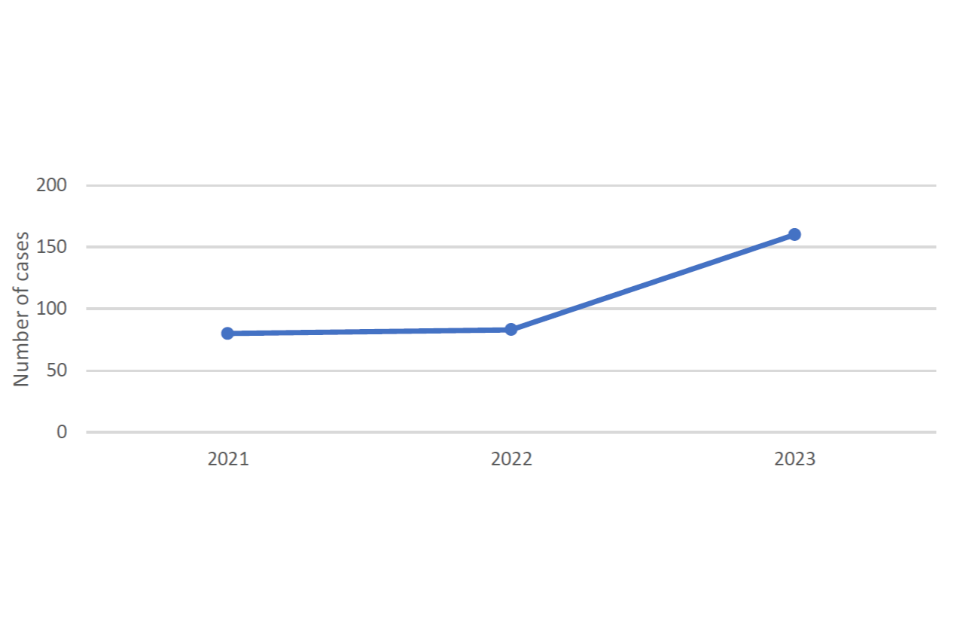

SOGIE related arrests January to December 2024

12.1.6 The Ugandan Police Force (UPF) annual Crime Reports contain a category ‘Sex related crimes’, which includes indecent assault, incest, and unnatural offences. The graph below uses data on unnatural offences from the UPF Annual Crime reports for 2022[footnote 97] and 2023 [footnote 98] covering 3 years (2021, 2022 and 2023). Section 145 of the penal code which legislates for ‘unnatural offences’ and acts against the ‘order of nature’ includes same-sex between men, bestiality and non-conventional sex between men and women, for example anal sex[footnote 99]. The UPF data under the unnatural offence subcategory does not state how many arrests were related to homosexuality and should therefore not be taken as the definitive number of SOGIE related arrests.

Unnatural offences

12.1.7 Unnatural offences comprised 0.6% of all sex related offences in 2022 (a total of 14,693) [footnote 100]] and 1% in 2023 (a total of 14,846)[footnote 101].

12.2 Prosecutions

12.2.1 The World Prison Brief, a database providing information about prison systems throughout the world operated by Birkbeck College, University of London. Country information is updated monthly, using data largely derived from governmental or other official sources[footnote 102]. The Uganda country page noted that as October 2024, the prison system operated at 367.2% of its intended capacity. There was a population of 78,057 (including pre-trial detainees/remand prisoners) against a prison capacity 21,257. The same source noted that 46.8% of total prisoners were pre-trial detainees/remand prisoners. The WPB further noted that the number of pre-trial/remand prisoners fluctuates from day to day, month to month and year to year, as a result the figures provide only an indication of the trend but the picture is inevitably incomplete [footnote 103] The data does not provide a breakdown of prisoners, hence it is not clear how many of the prisoners are LGBT+.

12.2.2 The SRT May 2024 report covering the period September 2023 to May 2024 noted:

‘In September 2023, the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) issued a directive to suspend the implementation of the AHA. The DPP directed that all such cases should be sent to her office for advice and that officers needed to build the capacity to understand the law before it is implemented. It should be noted that despite the directive by the DPP not to enforce some aspects of the law, police and other officers continued the arrest and charging of LGBTQ+ persons. In some cases, these persons were charged with other charges or given holding charges.

‘On 4th April 2024 following the Constitutional Court ruling on AHA, the DPP issued another directive that required all State Attorneys to forward cases under the nullified sections of the AHA to the headquarters for proper management. It should also be noted that in the second circular, the DPP did not stop the enforcement of other provisions of the AHA, nor had there been a capacity building of officers which the DPP had promised in the first circular. This has resulted in continued enforcement of the AHA even when the Court of Appeal decision has been appealed.’[footnote 104]

12.2.3 The same source further noted: ‘A total of 69 persons were arrested, 22 of these were released without charge after spending more than 48 hours in police custody, a direct violation of their right to liberty. 47 of these are arrests and charges were under the AHA while 22 were with no charges. Of those charged under the AHA, 31 were charged with homosexuality, 11 with aggravated homosexuality, 3 attempted homosexuality and 2 promotion of homosexuality.’[footnote 105]

12.2.4 The AI State of the World’s Human Rights report covering events in 2023 (AI 2023 report) noted: