Towards Zero - An action plan towards ending HIV transmission, AIDS and HIV-related deaths in England - 2022 to 2025

Updated 21 December 2021

Applies to England

Ministerial foreword

I’m so proud of how far we’ve come as a country on HIV. It’s a consequence of some incredible work across our health and care system, local government, the voluntary and community sector and so many more. Now, if diagnosed early and with the right treatment, people with HIV can expect to live a normal life. Not only does this HIV Action Plan set out our commitment to zero new transmissions of HIV by 2030, it sets out a plan for how we achieve it.

To realise our ambitious commitments – including our interim commitment to an 80% reduction in transmissions by 2025 – we should take enormous encouragement from the progress we’ve already made. We’ve met the UNAIDS 90-90-90 target for 3 years in a row. This means we’re diagnosing over 90% of people who live with HIV, over 90% of those who are diagnosed are getting treatment, and over 90% of those who are treated have quantities of HIV so small that it is undetectable. Should we achieve our commitment to reach zero new HIV transmissions by 2030, we would become the first nation in the world to do so.

We should also be encouraged that this is a government prepared to play its part on HIV. We’re making PrEP routinely available across the country, ensuring local authorities have the funds to get it to those who need it. We know that black African people, gay and bisexual men, and other groups experiencing health disparities continue to be disproportionately affected by HIV.

Of course, this is not a fight we will make alone. I’m very grateful to all the incredible partners who stand with us on this mission, especially the Independent HIV Commission and HIV Oversight Group under the leadership of Dame Inga Beale: we are all the stronger for our partnership. Working together, I believe it is not only possible to achieve our commitment, but compulsory. We must do it. And with this Action Plan, I believe that we will.

Sajid Javid MP

Secretary of State for Health and Social Care

Executive summary

The reduction in HIV transmission in England is a success story.

There was a 35% reduction in new HIV diagnoses in England between 2014 and 2019. In 2019 an estimated 94% of people living with HIV had been diagnosed, 98% of those diagnosed were on treatment, and 97% of those on treatment having an undetectable viral load – meaning they cannot pass on the infection.

The government is committed to achieving zero new HIV infections, AIDS and HIV-related deaths in England by 2030

This vital, highly stretching and world-leading ambition will require a doubling down on existing efforts and the adoption of new strategies to reach everyone we need to. We will need to maintain the excellent progress made with key groups – gay and bisexual men, younger adults, those in London – and significantly improve diagnoses for other groups. More progress is needed on heterosexuals, and black Africans remain the ethnic group with the highest rate of HIV, making them a priority for HIV prevention and testing. To achieve this, it is essential that we maintain our focus on combination prevention and testing levels, including opt-out testing in high and very high prevalence areas, must rapidly increase.

National Health Service England and NHS Improvement (NHSEI) will expand opt-out testing in emergency departments in the highest prevalence local authority areas, a proven effective way to identify new cases, and will invest £20m over the next three years to support this activity.

We also need to make up lost ground due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and understand how it has affected HIV prevention, testing, diagnosis, HIV care and the health of people living with HIV. As new infections reduce, they become harder to find, so we will need to continually adapt and evolve our strategy, tailoring our efforts to new groups and needs.

Prevent, test, treat and retain

To achieve our ambitions, we will ensure that partners across the health system and beyond maintain and intensify partnership working around 4 core themes – prevent, test, treat and retain. We will enhance, expand and bring together single elements of evidence-based HIV prevention activities into a comprehensive combination prevention programme. Components include preventing people from acquiring HIV, ensuring those who acquire HIV are diagnosed promptly, preventing onward transmission from those with diagnosed infection and delivering interventions which aim to improve the health and quality of life of people with HIV.

This HIV Action Plan sets the framework for how, together, we will achieve this. Over the coming months as we put this framework into practice, we and the range of partners necessary to achieving our 2025 and 2030 ambitions, will set out more detail on the specific actions we will take, the timetable for delivery, and how we will monitor progress. A national HIV Action Plan Implementation Steering Group comprised of all key partners, including the voluntary sector, will ensure we drive forward progress in line with our aims, and Parliament will be updated annually on progress by the Secretary of State.

Due to reduced testing, reconfiguration of clinical services and changes in behaviour associated with COVID-19 pandemic measures, 2019 has been taken as the baseline for the Action Plan.

On 1 December 2021, annual data for 2020 will be published here by the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA).

HIV in England today

HIV prevention is working. The total number of people newly diagnosed with HIV in England has decreased to 3,770 in 2019, a 35% fall from a peak of 5,790 new diagnoses reported in 2014. Of new HIV diagnoses made in England in 2019, 24% were first diagnosed abroad. We use diagnoses first made in England, so that we are focusing on transmission within England.

Life expectancy of people living with HIV is now near that of the general population. People diagnosed with HIV can expect to receive HIV care that is world class, free and open access. People living with HIV rate their HIV services highly.

New HIV diagnoses

The recent decline in new HIV diagnoses in England has largely been driven by reductions in diagnoses in gay and bisexual men who accounted for 41% of all new diagnoses first made in England in 2019.

Between 2015 and 2019 there have been greater declines in new HIV diagnoses in London compared to the rest of England, and in younger, white and UK-born people compared to those who are older, from other ethnic groups, and those not born in the UK. Levels of HIV transmission through routes other than sex remain low. Gay and bisexual men and black Africans continue to experience disproportionately high rates of HIV infection.

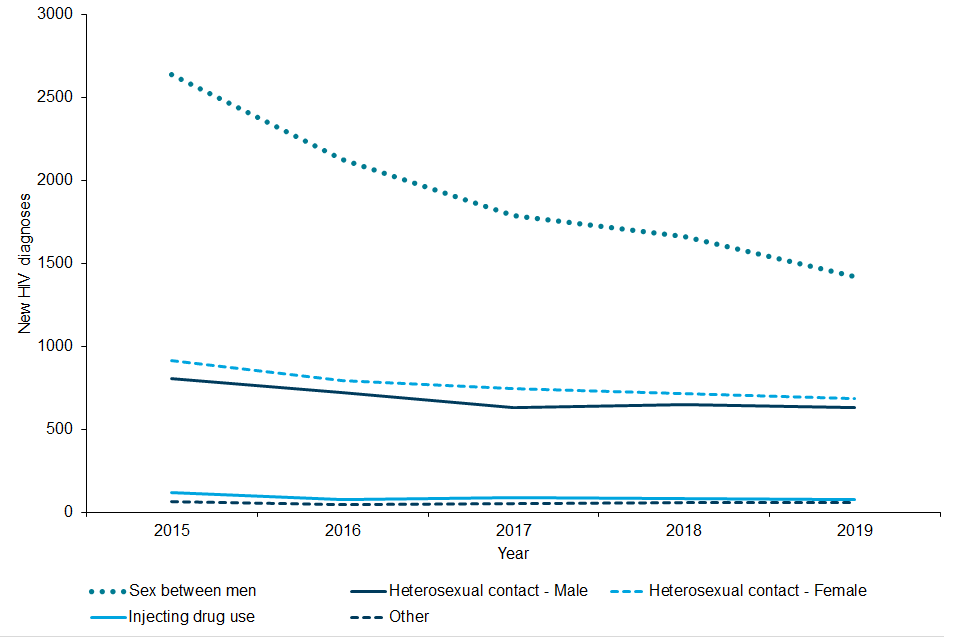

Figure 1: new HIV diagnoses first made in England by probable exposure route, 2015 to 2019[footnote 1]

Figure 1 is a line graph showing new HIV diagnoses among people living in England (persons first diagnosed in the UK) by probable exposure route, 2015 to 2019. The graph shows a decreasing trend in new HIV diagnoses over time for sex between men, and to a lesser extent among heterosexual adults. ‘Other’ and ‘Injecting drug use’ both show low levels of new HIV diagnoses.

Undiagnosed infections

In England, an estimated 96,200 people were living with HIV in 2019, including an estimated 5,900 with an undiagnosed HIV infection, equivalent to 6% of the total[footnote 2]. An estimated 2,800 gay and bisexual men were living with undiagnosed HIV and 2,900 heterosexuals. If untreated, the time from HIV infection to AIDS and death is a decade on average.

Late diagnosis

Late diagnosis (a person diagnosed with a CD4 count under 350 within 3 months)[footnote 3] is the most important predictor of morbidity and premature mortality among people with HIV infection and increases the risk of onward transmission. In 2019, 41% of all new diagnoses were made late.

Prompt treatment and retaining people in HIV care

Rapid referral into treatment and retention in treatment over time is essential to achieving good health outcomes and preventing onward transmission. With effective treatment, HIV can be supressed below transmittable levels.

In 2019, analysis by UKHSA showed that up to 18,160 people living with HIV in England had transmissible levels of virus, equivalent to 19% of people living with HIV in England. Of these 18,160, an estimated 5,930 (CrI 4,430 to 8,710) (33%) were undiagnosed, 3,890 (21%) were diagnosed but not referred to specialist HIV care or retained in care, 1,630 (9%) attended for care but were not receiving treatment, and 2,110 people (12%) were on treatment but not virally supressed. The remaining 4,600 (25%) had attended for care but were missing evidence of viral suppression.

Our objectives and actions

To progress towards our 2030 goals, this plan describes the progress we want to see by 2025:

- to reduce the number of people first diagnosed in England from 2,860 in 2019, to under 600 in 2025

- to reduce the number of people diagnosed with AIDS within 3 months of HIV diagnosis from 219 to under 110

- to reduce deaths from HIV/AIDS in England from 230 in 2019 to under 115

To achieve this, we will:

- keep doing what we know works – the progress we have made has required focus, effort and investment across the health system and beyond. To maintain it, we cannot take our foot off the pedal or change track and must redouble efforts to make up ground lost during COVID-19

- expand, improve, tailor and innovate – to ensure we reach everyone at risk of acquiring and transmitting HIV and deliver effective combination prevention including testing, treatment and care. As numbers decrease, we will need to keep refining our approach to find and support the people who need it

Our plan has 4 key objectives:

Objective 1: ensure equitable access and uptake of HIV prevention programmes

To prevent people without the virus from acquiring HIV infection, we will invest over £3.5 million to deliver a National HIV Prevention Programme over 2021 to 2024. We will deliver an annual national HIV Testing Week to get 20,000 higher risk people to test for HIV, deliver a wide range of prevention campaigns and innovative promotion activity, and provide extensive expert cross-system support for local HIV prevention activities. We will invest in HIV PrEP and develop a plan to drive innovation in PrEP delivery to improve access for key groups including provision in settings outside of sexual and reproductive health services. PrEP is funded at £23 million through the Public Health Grant – the grant funds the appointments and testing in sexual health services, with additional NHSEI funding for the drugs themselves.

Objective 2: scale up HIV testing in line with national guidelines

To ensure early identification of HIV infection, we will scale up HIV testing, focusing on those populations and settings where testing rates must increase, drawing on the experience of areas who have successfully scaled opt-out testing in key settings. We will drive far higher rates of testing offered in sexual health services and introduce testing into a wider range of settings. Overall, 97% of local authorities are already offering innovative online postal and/or collection HIV self-sampling services and we will work with those areas not providing this currently to make this 100%. We will work across the clinical and professional communities to reduce missed opportunities for HIV testing and late diagnosis of HIV. We will scale up capacity and capability for effective partner notification (PN) for people diagnosed with HIV, which allows us to uncover a linked chain of people unaware they are living with HIV and refer them to care.

Objective 3: optimise rapid access to treatment and retention in care

We will reduce the number of people newly diagnosed with HIV who are not promptly referred to care, monitoring and driving performance improvements across the system. We will boost support to people living with HIV to increase the number of people retained in care and receiving effective treatment, through galvanising innovations in care models and additional support for those with multiple or complex needs.

Objective 4: improving quality of life for people living with HIV and addressing stigma

We will work across the system to optimise the quality of life of those living with HIV, to support their health outcomes and reduce the chances of onward transmission. And we will tackle stigma and improve knowledge and understanding across the health and care system about transmission of HIV and the role of treatment as prevention, by enhancing the training of the health and care workforce and drawing on the best of innovation on public awareness and health promotion.

Achieving our 2030 goals will require sustained commitment from many partners across the health system and beyond. This Action Plan describes the role each partner will play in this vital endeavour, and the government’s commitment to supporting the whole system in securing progress. The success of recent years – and the scale of the task which still remains - should give us the belief and the drive to go further in the years ahead. This is a framework for the actions ahead and marks the start of the next phase in this vital journey.

1. Introduction

The care of people living with HIV has been transformed with effective treatment since the mid-1990s so that life expectancy is near that of the general population. Our world leading approach has led to a reduction in the number of people who acquire HIV in England in recent years. People diagnosed with HIV can expect to receive HIV care that is world class, free and open access. People living with HIV rate their HIV services highly.

1.1 Purpose and background

In January 2019 the government committed to a new ambition to achieve zero new HIV infections, AIDS and HIV-related deaths in England by 2030.

This ambition was warmly welcomed and in response 3 national charities, Terrence Higgins Trust, National AIDS Trust and Elton John AIDS Foundation established the HIV Commission to support its delivery. The commission, endorsed by government, included individuals from a range of backgrounds and people living with HIV who considered the evidence and made recommendations on how to meet the 2030 ambition. The commission’s comprehensive and compelling report was published on World AIDS Day 2020 and made many important recommendations that include an interim ambition of an 80% reduction in new infections, and reductions in AIDS diagnoses and HIV-related deaths by 2025[footnote 4]. This Plan outlines the actions that are needed across the health system to achieve this interim ambition which is an important milestone towards achieving the overall goal to end HIV transmission, AIDS diagnoses, and HIV-related deaths by 2030. A different approach and a new Action Plan are likely to be needed after 2025 as numbers of new infections decline even further.

The HIV Action Plan has been jointly developed by the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID, part of the Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC)) and the UKHSA.

A wide range of partners have also helped inform and shape the HIV Action Plan. To ensure continuity with the work of the independent HIV Commission, the government established an HIV Oversight Group, chaired by Dame Inga Beale, and membership of the group included a diverse range of organisations who offered their expertise and ensured that the voices of people living with HIV were represented. The terms of reference and membership can be found at Annex A.

The HIV Action Plan forms a part of the government’s wider Sexual and Reproductive Health Strategy. The strategy which will be published in 2022, will address overarching themes such as system leadership, workforce and inequalities which are relevant across Sexual Health, Reproductive Health and HIV. For this reason, these themes are not included in this Action Plan.

Annex B is a comprehensive background document developed by UKHSA that outlines the evidence base to support the actions proposed. Where possible England specific data has been included although UK wide data is considered to be a reasonable proxy for England given the very high distribution of new diagnoses and people living with HIV in England compared to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Annex C has a list of upper tier local authority areas with high (more than 2 diagnoses per 1,000 residents) or very high (more than 5 diagnoses per 1,000 residents) HIV prevalence.

We have also reviewed our Action Plan approach considering international evidence on what works for the elimination of infectious diseases. The HIV Action Plan aligns with this set of social and political criteria identified by the USA Centers for Disease Control and Prevention:

- societal and political commitment

- the disease under consideration for eradication must be of recognised public health importance, with broad international appeal with specific reasons for eradication

- a technically feasible intervention and eradication strategy must be identified

- consensus on the priority and justification for the disease must be developed by technical experts, the decision-makers, and the scientific community

- political commitment must be gained at the highest levels, including informed discussion at regional and local levels

- eradication requires an effective alliance with all potential collaborators and partners. The eradication programme must address the issues of equity and be supportive of broader goals that have a positive impact on the health infrastructure to provide a legacy in addition to eradication of the disease

- care must be taken that eradication efforts do not detract or undermine the development of the general health infrastructure

- the favourable attributes and potential benefits of eradication programmes are a well-defined scope with a clear objective and endpoint, and the duration is limited

- disease elimination and eradication programmes can be distinguished from ongoing health or disease control programmes by the urgency of the elimination and eradication programmes and the requirement for targeted surveillance, rapid response capability, high standards of performance, and a dedicated focal point at the national level. Eradication and ongoing programmes constitute potentially complementary approaches to public health

1.2 Where we are now

New HIV diagnoses

The recent decline in new HIV diagnoses has largely been driven by reductions in diagnoses in gay and bisexual men who accounted for 41% of all new diagnoses first made England in 2019 (see Figure 1). HIV has had a disproportionate impact on gay and bisexual men, however the gap between gay and bisexual men and the heterosexual population in terms of numbers of new diagnoses is narrowing (see Figure 1). We must continue to build on successful approaches to identifying new diagnoses in gay and bisexual men at an early stage of infection, while at the same time achieve similar success among heterosexual people at high risk of HIV infection.

Newly diagnosed HIV infections first made in England have declined less steeply among heterosexual men and women. In England, among people who probably acquired HIV through injecting drug use, new HIV diagnoses remain stable at around 100 per year. Of the 60 people diagnosed in 2019 who acquired HIV through mother to child transmission, only 5 (aged under 15 years) were born in the UK. However, we need to remain vigilant and monitor all routes of transmission, maintain high rates of HIV ante-natal testing and scale up testing in areas of high prevalence of HIV across the country including in drug and alcohol services, prisons and abortion services.

See Figure 1: new HIV diagnoses first made in England by probable exposure route, 2015 to 2019 [footnote 1]

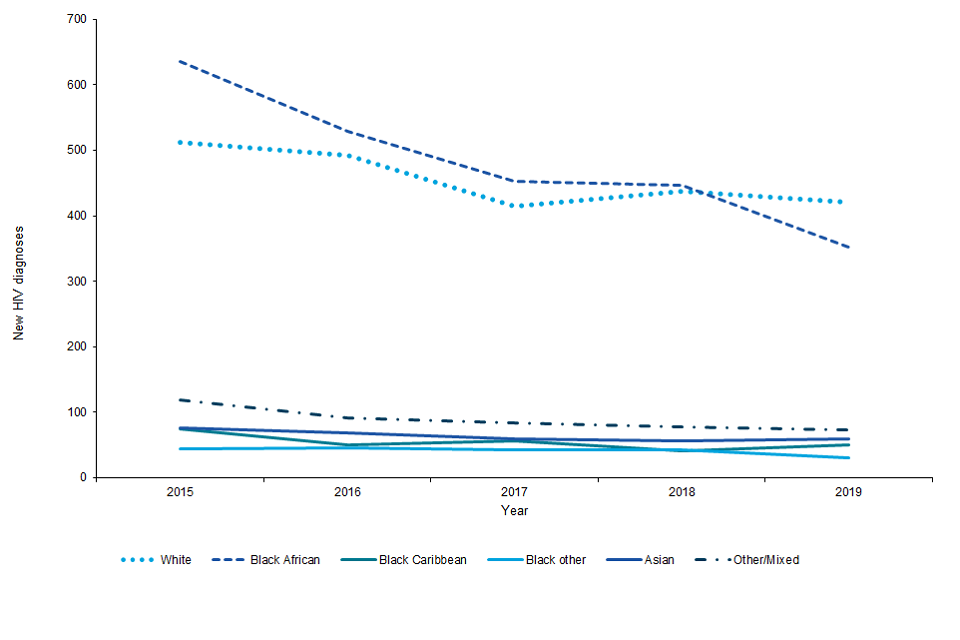

Between 2015 and 2019 there have been greater declines in new HIV diagnoses in gay and bisexual men in London compared to the rest of England, and in younger, white and UK-born men compared to those who are older, from other ethnic groups, and not born in the UK (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: new HIV diagnoses among gay and bisexual men first diagnosed in England, by region of residence, age group, ethnicity and country of birth, 2015 to 2019[footnote 1]

Figure 2 comprises 4 line graphs showing new HIV diagnoses among gay and bisexual men first diagnosed in England by region of residence, age group, ethnicity and country of birth, 2015 to 2019. Graph a shows that new HIV diagnoses are decreasing both within London and outside London, but to a greater extent in London. Graph b shows that new HIV diagnoses are decreasing most steeply in those aged under 50 years. Graph c shows that new HIV diagnoses have decreased at the fastest rate among white gay and bisexual men with much shallower reductions also seen across those of ‘Asian/other’, black African and black Caribbean ethnicity. Graph d shows HIV diagnoses have decreased over time for those born in the UK.

Among heterosexual people, there is a disproportionate impact of new HIV diagnoses on black Africans (see Figure 3). We need to do more to ensure equitable access to and uptake of HIV prevention programmes across England.

Figure 3: new HIV diagnoses among heterosexual adults first diagnosed in England by ethnicity 2015 to 2019[footnote 1]

Figure 3 is a line graph showing new HIV diagnoses among heterosexual adults first diagnosed in England by ethnicity 2015 to 2019. The graph shows that a slight decreasing trend in new HIV diagnoses over time that is steepest for black African and white people compared to people of other/mixed, Asian, and black Caribbean ethnicity.

Undiagnosed infections

In England, an estimated 96,200 people were living with HIV in 2019 including 5,900 with an undiagnosed HIV infection, equivalent to 6% of the total[footnote 2]. Of these it is estimated that there are 2,800 gay and bisexual men living with undiagnosed HIV and 2,900 heterosexuals. If untreated, the time from HIV infection to AIDS and death is a decade on average. Reducing the number of people unaware of their HIV infection is a crucial element of our plan to get to zero infections.

Late diagnosis

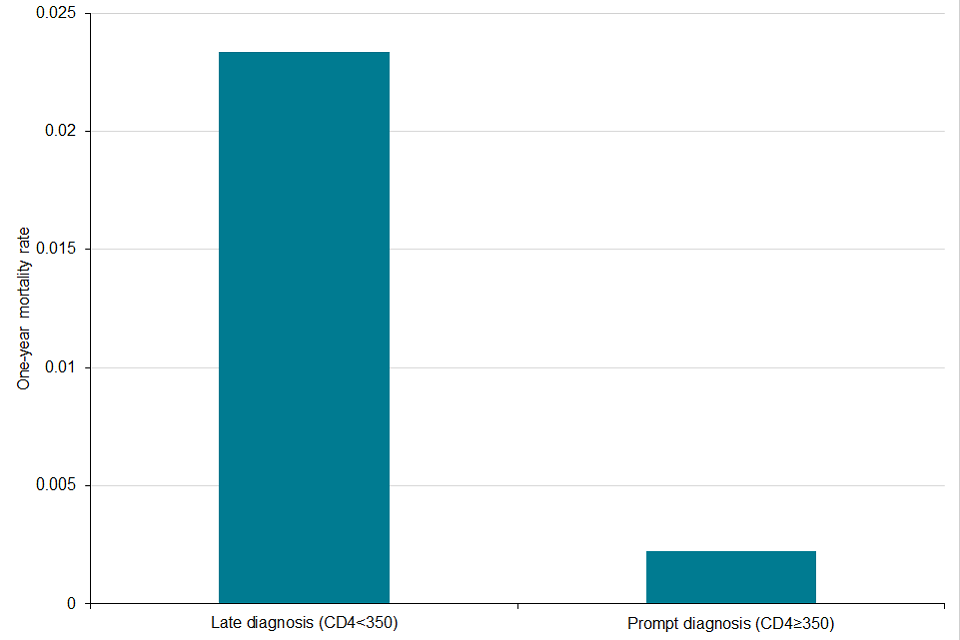

Figure 4: death within a year of HIV diagnosis among people first diagnosed in England by timelines of diagnosis, persons diagnosed in 2018[footnote 1]

Figure 4 is a bar chart showing death within a year of HIV diagnosis among people first diagnosed in England by timeliness of diagnosis, persons diagnosed in 2018. The chart shows that one year mortality rate for those with a late HIV diagnosis (CD4<350) is 8-fold greater than those with a prompt diagnosis (CD4 ≥350).

Late diagnosis (a person diagnosed with a CD4 count under 350 within 3 months[footnote 5]) is the most important predictor of morbidity and premature mortality among people with HIV infection (see Figure 4). The overall number of persons diagnosed late decreased from 1,700 in 2015 to 1,160 in 2019; equivalent to 39% and 41% of all new diagnoses respectively. The total number of people with AIDS at HIV diagnosis[footnote 6] decreased in England from 290 in 2015 to 220 in 2019 (160 males and 60 females). While this is welcome progress, we must do better if we are to achieve our ambitions on HIV. We need to Make Every Contact Count and ensure that across the health and care system there is recognition of those groups at higher risk of HIV and who should be offered a HIV test. More work also needs to be done to raise the profile of HIV and AIDS indicator conditions to ensure that when people present with these, action is taken to test for HIV at the earliest possible stage.

Prompt treatment and retaining people in HIV care, quality of life and stigma

To meet our ambition, we cannot only focus on preventing and diagnosing people living with HIV. As part of our combination prevention approach, we must also ensure that people who are diagnosed are referred into care promptly and stay in care, because with effective antiretroviral therapy (ART), HIV can be supressed below detectable and transmittable levels (Undetectable = Untransmittable). Therefore, supressing the virus in those diagnosed mean they cannot pass it on, further reducing overall transmission.

In England, using the UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets approach, 11% (10,580) of people had transmissible levels of virus. Further analyses by UKHSA showed an estimated that up to 18,160 people living with HIV in England had potentially transmissible levels of virus, equivalent to 19% of people living with HIV in England. Of these 18,160, an estimated 5,930 (CrI 4,430 to 8,710) (33%) were undiagnosed, 3,890 (21%) were diagnosed but not referred to specialist HIV care or retained in care, 1,630 (9%) attended for care but were not receiving treatment, and 2,110 people (12%) were on treatment but not virally supressed. The remaining 4,600 (25%) had attended for care but were missing evidence of viral suppression.

All these numbers need to be brought as close to zero as possible, which will require action along the HIV care pathway including improving data capture and reporting. In addition to direct HIV care, people living with HIV may also need other support from health and other services to maintain their quality of life. HIV-associated stigma remains a significant factor in people’s experience of living with HIV and significantly inhibits testing and prevention interventions. The 2021 ‘HIV: Public Attitudes and Knowledge’ report found that only a third of the public completely agree they have sympathy for all people living with HIV, regardless of how it was acquired.

1.3 Next steps including leadership and governance

This Action Plan will be supported and driven forward by a national HIV Action Plan Implementation Steering Group which will link into governance arrangements that will be established to support delivery of the Sexual and Reproductive Health Strategy. All national organisations will have a named lead with responsibility and accountability for taking forward relevant actions.

There are other existing structures in place for HIV, including those places designated as Fast-Track Cities. In other areas activity is led by Directors of Public Health and their teams. It is recommended that this existing infrastructure is developed to support implementation of this plan at a place-based level (for example, local authorities, regional structures and emerging successor organisations to CCGs) to review local epidemiology, understand existing practices, address gaps at a local level and share learnings. Regional work will be led by OHID/NHSEI Regional Directors of Public Health and supported by UKHSA.

Parliament will be updated annually on progress by the Secretary of State. If sufficient progress is not being made, we will consider what additional action may be required to remain on track.

UKHSA in collaboration with academics, commissioners, clinicians, and community partners will develop a set of indicators and targets and publish a monitoring and evaluation framework of this Action Plan in 2022. This will set out timeframes for delivering the actions in this plan and key indicators with which the actions can be monitored at the national, regional and local level, with the aim of supporting both national developments as well as informing local programme delivery and service improvement. The data will be disaggregated by key population characteristics where relevant to enable variations between key groups to be identified and addressed. UKHSA and OHID will lead on national reports on the progress of this Action Plan.

1.4 Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Dame Inga Beale for chairing the HIV Oversight Group, and for the Group’s expertise which helped inform and shape the Action Plan and for their passionate support, leadership, and engagement in tackling HIV. See the full terms of reference, membership, and summaries of meetings held by the Oversight Group. We look forward to working together to continue to drive toward our shared goals and ambitions.

Government is also grateful to the huge range of other organisations and individuals, including local authorities, health organisations, and charities who shared their views through meetings or correspondence. We also thank the All-Party Parliamentary Group on HIV/AIDS for their continued focus in this area and for their recent reports which were also considered as part of policy development.

2. Objective 1: ensure equitable access and uptake of HIV prevention programmes

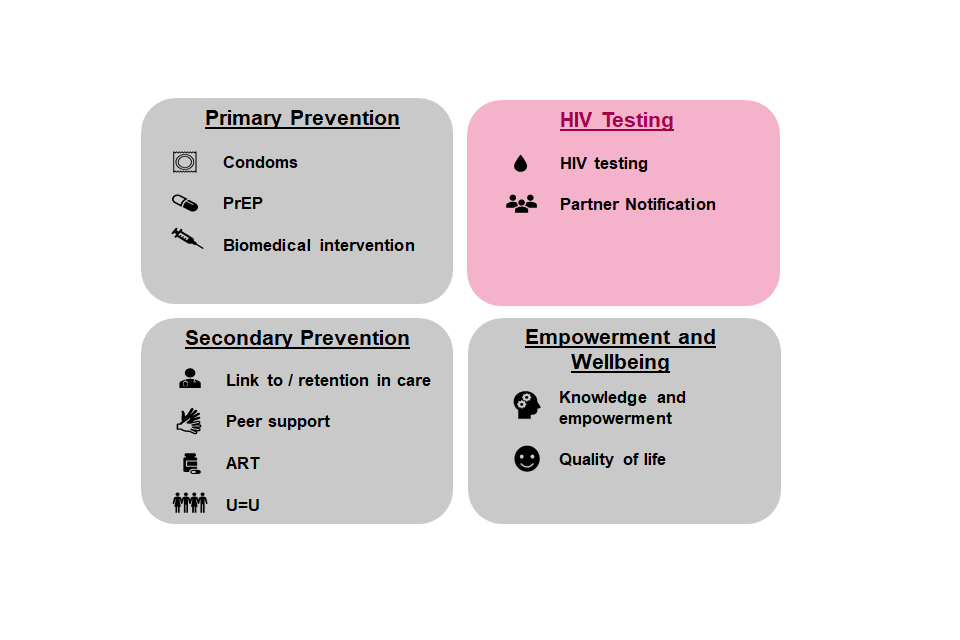

The image for objective 1 shows 4 units, each of which demonstrates a stage of a HIV pathway; primary prevention, HIV testing, secondary prevention and empowerment and wellbeing. The primary prevention unit is highlighted, and contains 3 graphics representing condoms, PrEP and biomedical interventions.

The need - objective 1

HIV prevention programmes are critical in ensuring that people are aware of how HIV is transmitted, how they can protect themselves, how and where to have an HIV test and developments in HIV treatment. Condoms prevent HIV, other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and unwanted pregnancies. HIV PrEP has been proven to be highly effective at preventing HIV transmission and is now routinely commissioned through specialist sexual health services.

Nonetheless the evidence suggests that awareness, accessibility, availability and uptake of primary prevention initiatives is variable in different demographics and addressing this disparity is key to HIV prevention. We also need to make up any lost ground due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and understand how it has affected HIV prevention.

What we know - objective 1

Social marketing campaigns

Social marketing campaigns have proved to be a cost-effective, scalable, and impactful tool for normalising and increasing HIV testing, reducing stigma and providing information on HIV to at-risk communities. Campaigns should consider cultures, social norms, messaging, multiple communication channels and digital exclusion in their design.[footnote 1]

Condoms

Condoms are an effective method of preventing the onward transmission of HIV with a ‘real world’ effectiveness[footnote 7] of between 70% to 80% for heterosexual couples and 70% to 92% for gay male couples. Free condom distribution schemes are widely commissioned by local authorities through a variety of outlets including community pharmacies. Condom distribution schemes have been shown to successfully reach communities and groups at greater risk such as young people including those aged 16 to 19 years, individuals of ethnic minority backgrounds and those living in deprived areas (see Annex A section 2.5).

Biomedical interventions

There are several established and emerging biomedical interventions for HIV prevention. Current options include the use of Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) by people without HIV before or after exposure to the virus (pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis, respectively). There are ongoing studies investigating the use of vaccines for HIV prevention and treatment.

- Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) – is the use of ART by people without HIV to reduce their risk of acquiring HIV. Following government investment and action by providers, local authorities, and NHSEI, from October 2020, oral PrEP is now provided in specialist sexual health services in England. Oral emtricitabine and tenofovir (F/TDF) has been shown to be highly effective at reducing the risk of acquiring HIV among all key population groups including men who have sex with men, transgender men and women, heterosexual men and women and injecting drug users.[footnote 1]

- Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) – is the use of ART by people without HIV to reduce their risk of acquiring HIV after a potential exposure to the virus. Currently, PEP is available through hospital accident and emergency departments, sexual assault referral centres and specialist sexual health services in England.

The actions required to deliver on objective 1

Action 1: we will continue to invest in evidence-based national HIV prevention campaigns and provide additional cross-system support for local HIV prevention activities.

-

OHID will invest over £3.5 million to deliver a National HIV Prevention Programme over 2021 to 2024. This programme makes an important contribution to efforts to reduce HIV transmission by improving awareness of combination HIV prevention and increasing access to HIV testing through a number of different initiatives, ensuring that more people in England are aware of their HIV status (established by independent external evaluation). This unique programme is a crucial component of our plans to end new transmissions of HIV in England by 2030. The specific components of the National HIV Prevention Programme 2021 to 2024 are:

- deliver the annual national HIV Testing Week with the aim of getting 20,000 higher risk people to test for HIV (with syphilis opt-out)

- deliver ‘always on’ health promotion activity in addition to an agreed number of health promotion campaigns and interventions each year, using a range of different types of media including digital and social media

- provision of relevant information materials, using simple and appropriate messaging on a variety of accessible media including print and digital, aimed at the main target groups of black African heterosexuals and gay and bisexual men

- with the endorsement and approval of local authorities, work alongside local HIV prevention activities in order to maximise joint investment by reducing duplication (such as sharing campaign materials)

- provide support to the broader HIV and STI prevention sector and organisations who work with people most at risk of HIV, developing local effective practice and knowledge and supporting the development of skills, capacity and leadership

- disseminate evidence and promising practice across the wider HIV prevention community

- OHID has commissioned an independent review to assess the impact of the Sexual Health, Reproductive Health and HIV Innovation Fund which has funded local voluntary sector prevention projects targeted at higher risk groups (including campaigns, condom uptake, PrEP, PEP and other interventions) since 2015. Based on the findings from the review we will consider the next steps for this fund in 2022.

- UKHSA will develop an HIV prevention toolkit to support local authority and NHS partners drive improvements in prevention delivery and outcomes.

- OHID and UKHSA, working with regional sexual health and other relevant networks, will ensure sexual health promotion messages are promoted outside sexual health services, such as drug and alcohol settings.

Action 2: we will continue to invest in HIV PrEP (funded at £11 million in financial year 2020 to 21 and £23.4 million in financial year 2021 to 2022) through the Public Health Grant, and will support the system to continue to improve access to PrEP for key population groups and monitor progress through a monitoring and evaluation framework.

- Data from the PrEP Impact trial shows that heterosexual women and men, trans populations, older age groups and black and ethnic minority populations were under-represented compared to white, young gay and bisexual men[footnote 1]. UKHSA will publish a PrEP monitoring and evaluation framework in 2022 that will use existing data sources to inform service improvement in PrEP commissioning and delivery, and to help identify and initiate ways to reduce health inequalities.

- We will develop a plan for provision of PrEP in settings beyond sexual and reproductive health services. This will be based on the findings of work which the English HIV and Sexual Health Commissioners’ Group are commissioning with potential PrEP users to explore the acceptability of delivering PrEP in settings such as drug and alcohol services and pharmacies. NHSEI are also taking forward a pilot for accessing PrEP in prisons.

- We know that PrEP is highly effective when taken as prescribed. However, taking a pill regularly can be challenging for some people. Provision of a wider choice of PrEP methods, including injectable versions may improve uptake, acceptability, and adherence. OHID will work with NHSEI and partners to monitor the potential use of new methods such as injectable PrEP as the evidence to support their effectiveness becomes available.

3. Objective 2: scale up HIV testing in line with national guidelines

The image for objective 2 shows 4 units, each of which demonstrates a stage of a HIV pathway; primary prevention, HIV testing, secondary prevention and empowerment and wellbeing. The HIV testing unit is highlighted and contains 2 graphics representing HIV testing and partner notification.

The need - objective 2

HIV testing is essential so that everyone with an HIV infection can be offered lifesaving treatment, which also prevents onward HIV transmission by reducing viral load to undetectable and untransmittable levels. If people test negative for HIV, this also provides an important opportunity for information provision or conversations about HIV prevention, and the prevention options that might best suit an individual.

However, some people are still being missed by HIV testing. In England in 2019, an estimated 5,900 people were estimated to be living with an undiagnosed HIV infection[footnote 8] and while the number of people diagnosed at a late stage of HIV infection[footnote 9] in England decreased from 1,950 in 2014 to 1,160 in 2019, it remains high at 41% of all new diagnoses.

Testing rates must be increased, especially in settings and areas where they are most likely to find positive cases. Testing must be made more accessible, particularly for those groups being under-diagnosed. We must tackle the stigma or other barriers which can stop someone taking up a test when offered.

What we know - objective 2

Overall coverage of HIV testing in sexual health services was 65% in 2019. Of those who did not get tested, 46% were not offered a test and the remainder declined. While HIV testing coverage remains high in sexual health services, too many black Africans, especially heterosexual women attendees, are not tested. An 18% increase in gay and bisexual men tested for HIV in England was observed from 103,300 in 2015 to 122,010 in 2019, whereas the number of black African heterosexuals tested for HIV only increased by 3% from 43,490 in 2015 to 44,910 in 2019.[footnote 10]

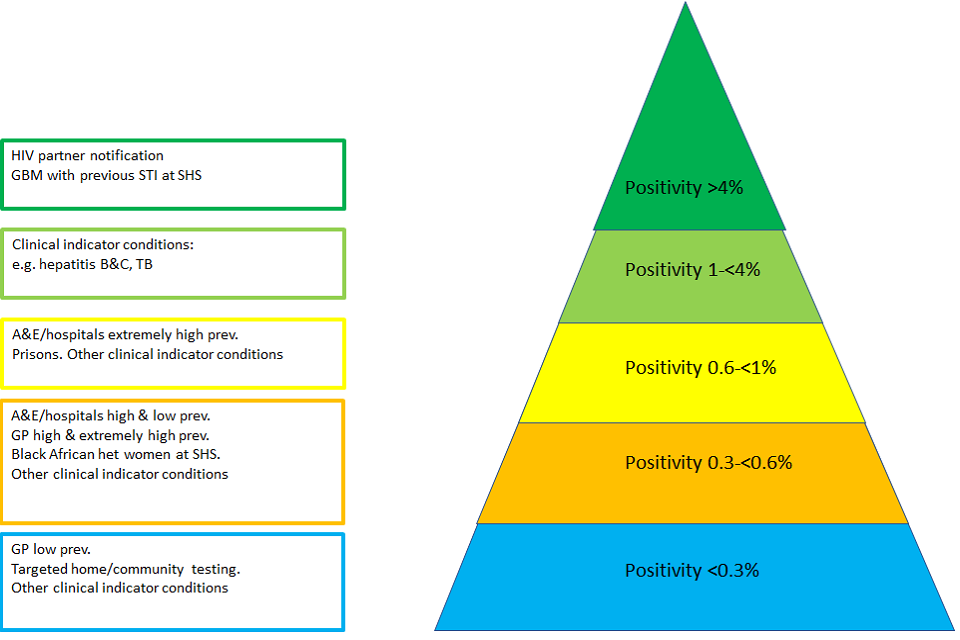

Figure 5: HIV testing positivity pyramid, England 2019[footnote 1]

Figure 5 shows a HIV testing positivity pyramid, England 2019. Figure 5 is a pyramid with 5 layers. Each layer represents a different rate of HIV testing positivity in England. Areas with a positivity of <0.3% occur in settings such as testing via GP in low prevalence areas, targeted home/community testing and for other clinical indicator conditions. Areas with a positivity of 0.3-<0.6% include testing via A&E/hospitals in areas of high and low prevalence, via GP in high and extremely high prevalence areas, for black African heterosexual women at sexual health services and for other clinical indicator conditions. Areas with a positivity of 0.6-<1% include testing via A&E/hospitals in areas of extremely high prevalence, prisons and for other clinical indicator conditions. Areas with a positivity of 1-<4% include examples such as testing for clinical indicators conditions, like hepatitis B, hepatitis C and tuberculosis. Areas with a positivity of >4% relate to HIV partner notification and for testing for gay, bisexual and men who have sex with men with a previous STI at a sexual health service.

England has robust, evidence-based HIV testing guidelines produced by The British HIV Association (BHIVA), The British Infection Association (BIA), The British Association of Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH) and The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) that set out recommendations for HIV testing in sexual health services and as well as other settings. These guidelines set out recommendations for HIV testing in sexual health services and as well as other settings. They are designed to target people at greatest risk of undiagnosed HIV infection through focussing on HIV indicator conditions and those living in areas where prevalence is highest.

Figure 5 shows the relative HIV testing positivity rates for different settings and population groups. It demonstrates, for example, the need for effective HIV partner notification and testing for gay and bisexual men previously diagnosed with an STI. It is important to identify where there are missed opportunities for testing and gaps in testing provision.[footnote 11] Opt-out HIV testing coverage for pregnant women remains high at over 99% and has been highly effective in reducing mother to baby transmissions. More could be done elsewhere on opt-out testing in geographic areas of high or very high HIV diagnosed prevalence,[footnote 12] for example in primary care, emergency departments, prisons and termination of pregnancy services. Recent developments suggest that HIV testing in different settings is acceptable to patients; for example, tests via self-sampling and testing kits ordered online have expanded by 63% from 2018 to 2019, comprising 18% of all HIV tests in 2019. This expansion has further accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Late HIV diagnoses

In 2019, 41% of adults diagnosed England were diagnosed at a late stage of HIV infection.[footnote 13] Being diagnosed late increases the risk of dying by 8-fold and it is estimated that someone who is diagnosed very late with HIV has a life expectancy at least 10 years shorter than someone who starts treatment earlier. Certain population subgroups such as heterosexual black African men are more likely to be diagnosed late and therefore suffer worse outcomes.[footnote 14]

Partner notification (PN)

PN is a voluntary process where trained health workers ask people diagnosed with HIV about their sexual partners or drug injecting partners, and with their consent offer these partners HIV testing. PN allows us to uncover a linked chain of people (including mother to child transmission) unaware they are living with HIV and refer them to care. PN is also important in identifying HIV negative partners who may be at higher risk of HIV and would benefit from effective HIV prevention (for example, PrEP). The overall HIV test positivity of PN contacts was 4.6%, substantially higher than the HIV test positivity in specialist sexual health services (0.2%),[footnote 11] demonstrating the potential impact of consistent PN.

The actions required to deliver on objective 2

Action 3: we will scale up HIV testing, focusing on those populations and settings where testing rates must increase

- NHSEI will expand opt-out testing in emergency departments in the highest prevalence local authority areas, a proven effective way to identify new cases, and will invest £20m over the next three years to support this activity.

- We will share learning from those areas who have successfully implemented opt-out HIV testing in emergency services in high and very high prevalence areas. Those areas which need to make the most progress will be supported by OHID and UKHSA.

- Local authority commissioners should set a standard for sexual health services to achieve a 90% testing offer rate to first time attendees, as per BHIVA guidelines. UKHSA will monitor and report on progress towards this standard.

- Local authorities, NHS, and other commissioners must consider testing in a wider range of services such as prisons, drug and alcohol services, pharmacies and abortion services and include opportunities for assessing integrated STI testing where relevant. This will be supported by data from UKHSA and OHID, which local authorities should use in joint strategic needs assessments and Health Equity Audits (HEAs) to actively consider how key population groups in their area are accessing community and HIV self-testing services.

Action 4: we will reduce missed opportunities for HIV testing and late diagnosis of HIV

- UKHSA and OHID will work with professional bodies and community groups to identify the key reasons why some people may not be offered or decline the offer of a HIV test in sexual health services.

- OHID and UKHSA will work with partner organisations to review all relevant indicator conditions guidelines/Clinical Knowledge Summaries and identify opportunities to include routine HIV testing. Individuals with undiagnosed HIV often present to primary care or emergency departments with indicator conditions that that are linked to HIV and AIDS-defining conditions. We must reduce missed opportunities to test for HIV.

- The Deputy Chief Medical Officer will work with the range of relevant professional bodies and Royal Colleges to obtain commitments from relevant specialties to increase HIV testing among patients with clinical indicator conditions.

- OHID, UKHSA and NHSEI will work with professional bodies to review existing late diagnosis protocols, identify opportunities to strengthen these prior to national roll out.

- UKHSA will lead work to understand the circumstances surrounding recent HIV acquisition in England. This information will identify missed opportunities for prevention and inform prevention and partner notification strategies.

Action 5: we will innovate and transform capacity and capability for effective partner notification (including both digitally and for the digitally excluded)

- Partner notification is an essential opportunity to identify the sexual contacts of those newly diagnosed with HIV and to recall and regularly test those at higher risk of HIV, which is often done via digital approaches. OHID will work with Health Education England to undertake a workforce review, which will include capacity to undertake partner notification and consideration of the workforce skills required to support this specialist task (as part of the development of the Sexual and Reproductive Health Strategy).

- Building upon experiences of contact tracing for COVID-19, OHID will work with sexual health services’ providers and commissioners to identify novel, cost effective approaches, including the best technologies, to further modernise contact tracing for HIV infections. OHID will share details of recent relevant research and good practice.

- Providers of sexual health services should evaluate alternative methods of partner notification, including both digital tools and outreach/non-digital approaches for the digitally excluded, and incorporate them into policy and practice as appropriate.

4. Objective 3: optimise rapid access to treatment and retention in care

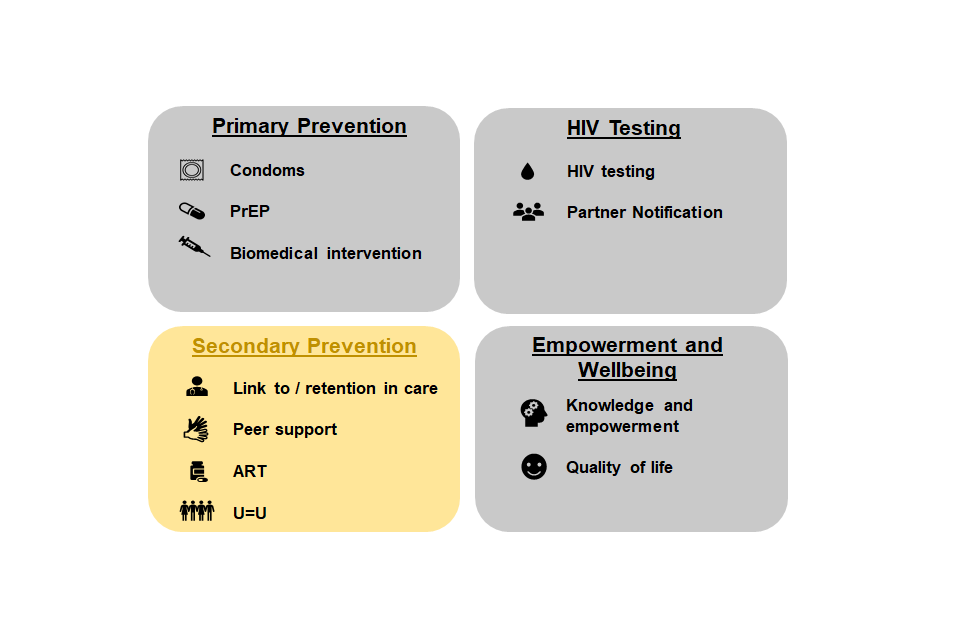

The graphic for objective 3 shows 4 units, each of which demonstrates a stage of a HIV pathway: primary prevention, HIV testing, secondary prevention, and empowerment and wellbeing. The secondary prevention unit is highlighted, and contains 4 graphics representing link to/retention in care, peer support, ART and U=U.

The need - objective 3

Rapid access to and retention in HIV treatment can support those diagnosed with HIV to maintain an undetectable viral load, meaning they cannot transmit the infection to their sexual partners (Undetectable viral load = Untransmittable levels of virus (U=U)).[footnote 15] England does very well on viral suppression and retention in care: 98% of people living with diagnosed HIV infection were on treatment, and 97% of people treated were virally suppressed in 2019.

Viral suppression was lowest among people aged 15 to 24 years (91%), people who probably acquired HIV through injecting drug use, (94%) and among people who probably acquired HIV vertically[footnote 16] (89%).

We need to ensure everyone who is diagnosed is referred to treatment rapidly and ensure that inequalities in access to and retention in treatment are tackled.

What we know - objective 3

BHIVA guidelines state 90% of people should be referred into HIV care 2 weeks after diagnosis. In 2019, 78% of adults in England who were newly diagnosed in 2019 were referred into to specialist HIV care within one month. Rapid access to HIV care must be maintained and improved where possible. In 2019 in England, 320 people were not referred into care, this number must be brought as close to zero as possible. Successful referral was highest in those diagnosed in infectious disease units (98%) and lowest in those diagnosed in settings (75%) that included blood transfusion services, prisons, home testing, drug misuse services, self-sampling services and pharmacies.

Retention in care and effective treatment

Encouragingly, people living with HIV in England in 2017 rated the quality of their HIV care as, on average, 9.3/10. However, in 2019 in England, 3,570 people were not retained in care; this number must be brought as close to zero as possible. As an increasing proportion of people living with HIV are over 50 and/or experiencing long term conditions, services must adapt to meet their potentially more complex needs. Collaborative working and system leadership over the coming years will be key to ensuring delivery of services to support the care and wellbeing of people living with HIV, particularly for those living with complex needs to avoid the risk of people being lost to follow up.

The actions required to deliver on objective 3

Action 6: we will reduce the number of people newly diagnosed with HIV who are not promptly referred to care

-

UKHSA will monitor whether people newly diagnosed meet the national standard of being referred to HIV care within 2 weeks. Service and population level information will be routinely shared with NHSEI and relevant clinical groups.

-

NHSEI will work with partners including UKHSA, HIV services and system commissioners to use data at a national, regional and local level to support and strengthen pathways for care into HIV services and the barriers that supports prompt referrals into the HIV service. Review of the national HIV service specification will support the need to understand and address any regional variations. Commissioners and providers of services that deliver HIV testing should ensure robust results pathways are in place to facilitate appropriate support around results and rapid access to treatment, such as in primary care settings or viral hepatitis outreach screening.

Action 7: we will boost support to people living with HIV to increase the number of people retained in care and receiving effective treatment

- UKHSA and NHSEI will work with professional groups to identify the key barriers to retention in care and disseminate this information to support the development of local strategies.

- UKHSA will provide routine information at service level to monitor the effectiveness of follow-up strategies for people registered with their service who become disengaged from care. Service and population level information will be routinely shared with NHSEI and relevant clinical groups.

- NHSEI and OHID will work with local government and BHIVA and BASHH to develop innovative models for the future workforce, including how current workforce roles can provide better support to retaining people in care. This includes managing the transition between young person and adult HIV care and treatment services and coordinating care among multiple clinical specialties.

- UKHSA will provide data and information to local commissioners and service providers to evaluate and adopt innovations in HIV care delivery – including those introduced in response to the COVID-19 pandemic – such as outreach settings, or via phone or video, while ensuring service accessibility and acceptability for all.

- OHID will review the current model sexual health service specification to strengthen pathways with other services, including drug and alcohol, domestic abuse and mental health services. This includes consideration of integrated services or collaborative commissioning. Regard must be given to those groups who may face additional barriers to access, such as migrants or those who are homeless or in insecure housing. The review of NHSEI’s service specification will look at the importance of services involving key communities and people living with HIV in the design and ongoing development of services.

5. Objective 4: improving the quality of life for people living with HIV and addressing stigma

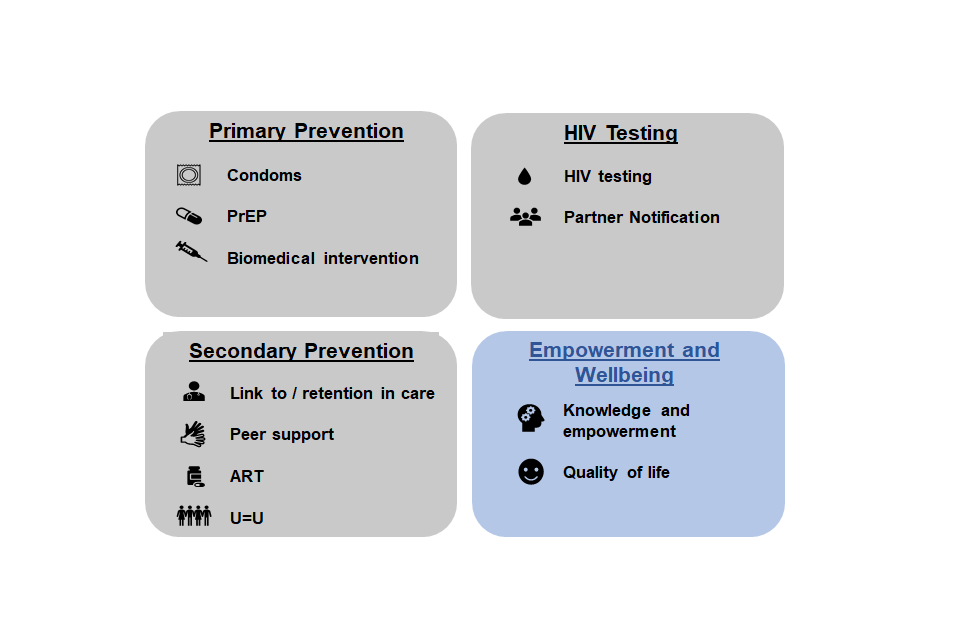

This graphic for objective 4 shows 4 units, each of which demonstrates a stage of a HIV pathway: primary prevention, HIV testing, secondary prevention, and empowerment and wellbeing. The empowerment and wellbeing unit is highlighted and contains 2 graphics representing knowledge and empowerment and quality of life.

The need - objective 4

Improving the quality of life for people with long term conditions is a well-established goal for the NHS and wider health and care system. However, for some people living with HIV it can be challenging to prioritise their HIV care and adherence to treatment if they are experiencing personal, financial, housing, immigration, or mental health difficulties. Increasing retention in, and adherence to, care supports achieving good health outcomes and reduces HIV transmission.

HIV-associated stigma remains a significant factor in people’s experience of living with HIV and significantly inhibits testing and prevention interventions. The 2021 ‘HIV: Public knowledge and attitudes’ report found that only a third of the public completely agree they have sympathy for all people living with HIV, regardless of how it was acquired.

What we know - objective 4

Support

Availability of HIV peer support, psycho-social and mental health services is variable across the country and delivered through a range of different models. Peer support models, where assistance and encouragement is provided by an individual considered equal, is not only a highly effective approach for referring to and retaining people living with HIV in care and treatment, but also meets wider individual wellbeing needs in holistic ways. Investment in peer support pathways, particularly in areas of high and very high prevalence, or for newly diagnosed and older people living with HIV and multiple other conditions, has the potential to improve wellbeing and support retention in HIV care.

Addressing HIV stigma

The Positive Voices survey found that 14% of people with HIV experienced discrimination in the NHS in one year, signalling a need to update the knowledge and understanding of HIV transmission and U=U in the healthcare workforce.

The actions required to deliver on objective 4

Action 8: we will optimise the quality of life of those living with HIV

- We will develop an audit tool to enable local areas to understand provision of availability and accessibility of HIV mental health, psycho-social and peer support services available to people living with HIV across the life-course.

- OHID and UKHSA will share emerging evidence on the effectiveness of voluntary sector-led peer support networks for local commissioners to develop similar models.

Action 9: we will tackle stigma and improve knowledge and understanding across the health and care system about transmission of HIV and the role of treatment as prevention

- OHID will work with national organisations, including HEE, to include information on HIV transmission, U=U and infection control as an element of every healthcare worker’s standard induction and regular mandatory training. OHID working with NHSEI will examine ways to assess the level of HIV awareness among healthcare staff. OHID will also request that NHSEI (and/or other relevant NHS organisations) consider including relevant questions in relation to HIV awareness and stigma in their annual staff survey and take appropriate action on the findings.

- OHID-NHSEI Regional Directors of Public Health will establish a working group with partners across local government, academia and the voluntary and community sector to modernise occupational policies on anti-HIV stigma, promoting their development and dissemination across sectors and become more proactive in ending HIV stigma.

- UKHSA, working with academic and community partners, will monitor the levels of stigma and discrimination experienced by people living with HIV within the health and social care system as well as within community settings.

- All sexual health or HIV social marketing and health promotion campaigns must raise awareness of U=U and treatment as prevention to reflect the latest developments in HIV prevention and tackling stigma as one of their objectives. OHID will share with local areas examples of campaigns where these issues have been successfully highlighted.

- To support people to live well with HIV, local authority and NHS commissioners and service providers should design and deliver culturally competent HIV and related health services. Partners should include primary care (to support HIV prevention, testing, and treatment) and social care (to develop stronger links as people age with HIV). This should be considered particularly among populations who experience one or multiple forms of discrimination, such as that based on their sex, race, sexual orientation, or gender re-assignment.

6. Independent HIV Commission recommendations mapped to HIV Action Plan

| HIV Commission Recommendation | Action Plan response | Additional comments | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Action 1 - All national and local HIV treatment and prevention initiatives should explicitly plan and evaluate how they will address HIV-related stigma, discrimination, and health inequalities. | Action 9: we will tackle stigma and improve knowledge and understanding across the health and care system about transmission of HIV and the role of treatment as prevention. | ||

| Action 2 - As more people living with HIV access non-specialised healthcare, training on HIV and sexual health should be mandatory for the entire healthcare workforce to address HIV stigma and improve knowledge of indicator conditions. | Action 9: we will tackle stigma and improve knowledge and understanding across the health and care system about transmission of HIV and the role of treatment as prevention. | ||

| Action 3 - Implement a programme of coordinated national campaigns across the decade, aiming to enable residents in England to know how to find out their HIV status and increase their awareness of combination HIV prevention. | Action 1: we will continue to invest in evidence-based national HIV prevention campaigns and provide additional cross-system support for local HIV prevention activities. | A mass campaign for all adults in England would not meet value for money criteria | |

| Action 4 - Opt-out rather than opt-in HIV testing must become routine across healthcare settings, starting with areas of high prevalence. | Action 3: we will scale up HIV testing, focussing on those populations and settings where testing rates must increase. … NHSEI will expand opt-out testing in emergency departments in the highest prevalence local authority areas, a proven effective way to identify new cases, and will invest £20m over the next 3 years to support this activity. | Our assessment is that opt-out testing across all healthcare settings would present significant challenges and evidence points to continuing targeted and geographical approaches as recommended in clinical guidelines with greater emphasis on partner notification, internet and other remote testing. | |

| Action 5 - The health and care system must be able to adopt innovations more quickly and consider equitable access to innovation at every stage of planning and implementation. This includes in telehealth, online testing, and new biomedical technologies. | Action 2: we will continue to invest in HIV PrEP (funded at £11 million in financial year 2020 to 21 and £23.4 million in financial year 2021 to 2022) through the Public Health Grant , and will support the system to continue to improve access to PrEP for key population groups and monitor progress through a monitoring and evaluation framework. … OHID will work with NHSEI and partners to monitor the potential use of new methods such as injectable PrEP as the evidence to support their effectiveness becomes available. | ||

| Action 6 - Partner notification should be prioritised by local government, particularly in relation to key populations. | Action 5: we will innovate and transform capacity and capability for effective partner notification (including both digitally and for the digitally excluded). | ||

| Action 7 - Maximise the flexibility and granularity of data collection systems to meet the changing face of HIV and tackle inequity, including reporting on all communities with over 500 cases of new transmission in the last 5 years. | In 2022, a monitoring and evaluation framework will be published. This will set out timeframes for delivering the actions in this plan and key indicators with which the actions can be monitored at the national, regional and local level, with the aim of supporting both national developments as well as informing local programme delivery and service improvement. The data will be disaggregated key population characteristics to enable variations between key groups to be identified and addressed. | ||

| Action 8 - All late HIV diagnoses must be investigated as a serious incident by the National Institute for Health Protection, working with BHIVA, NHS Trusts, local authorities, and Clinical Commissioning Groups. | Action 4: we will reduce missed opportunities for HIV testing and late diagnosis of HIV. | ||

| Action 9 - The Treasury and Department of Health and Social Care must understand the unmet need in the sexual health sector and provide a radical uplift in public health funding, particularly that invests in local sexual and reproductive health services. | Local authority spending through the public health grant will be maintained in real terms 2022 to 2025, meaning local authorities can continue to invest in prevention and essential frontline health services including £23.4 million annually for PrEP. … OHID is investing over £3.5 million to deliver a National HIV Prevention Programme over 2021 to 2024. | ||

| Action 10 - The government HIV Action Plan must include the development of a strategy for recruitment, training, and retention of the HIV workforce, in clinical settings, local government and the voluntary sector. | Action 7: we will boost support to people living with HIV to increase the number of people retained in care and receiving effective treatment … NHSEI and OHID will work with local government and BHIVA and BASHH to develop innovative models for the future workforce, including how current workforce roles can provide better support to retaining people in care. This includes managing the transition between young person and adult HIV care and treatment services and coordinating care among multiple clinical specialties. | Workforce issues will also be addressed in the SRH Strategy for England | |

| Action 12 - There must be clear financial accountability and responsibility for PrEP provision beyond sexual health clinics (for example, in GP surgeries, maternity units, gender clinics and pharmacies). This should include promotion to improve awareness and uptake for all communities who will benefit from PrEP. | Action 2: we will continue to invest in HIV PrEP, funded at £23.4 million through the Public Health Grant, and will support the system to continue to improve access to PrEP for key population groups and monitor progress through a monitoring and evaluation framework. … We will develop a plan for provision of PrEP in settings beyond sexual and reproductive health services. This will be based on the findings of work the English HIV and Sexual Health Commissioners’ Group are commissioning with potential PrEP users which will explore the acceptability of delivering PrEP in settings such as drug and alcohol services and pharmacies. NHSEI are also taking forward a pilot for accessing PrEP in prisons. | ||

| Action 13 - The Department of Health and Social Care should develop a return on investment tool for HIV prevention interventions. | Action 1: we will continue to invest in evidence-based national HIV prevention campaigns and provide additional cross-system support for local HIV prevention activities. | ||

| Action 14 - Accountability for meeting the 2030 goal should be shared by the Cabinet Office and the Department of Health and Social Care to drive the agenda. The minister must give an annual report to parliament on progress towards our goals – 80% by 2025, 100% by 2030 and England’s ability to be the first to end HIV domestic transmission. | Parliament will be updated annually on progress by the Secretary of State. If sufficient progress is not being made, we will consider what additional action may be required to remain on track. … This Action Plan will be supported and driven forward by a national HIV Action Plan Implementation Steering Group who will link into governance arrangements that will be put in place to support delivery of the Sexual and Reproductive Health Strategy. All national organisations will have a named lead with responsibility and accountability for taking forward relevant actions. | ||

| Action 15 - To ensure transparency, live granular data on progress towards our goal must be publicly available online in a simple format. | In 2022, a monitoring and evaluation framework will be published. This will set out timeframes for delivering the actions in this plan and key indicators with which the actions can be monitored at the national, regional and local level, with the aim of supporting both national developments as well as informing local programme delivery and service improvement. The data will be disaggregated key population characteristics to enable variations between key groups to be identified and addressed. | ||

| Action 16 - The government must review and assess the impact of current policies and legislation which act as a barrier to HIV progress or where performance improvement is needed. This must involve reviewing laws that criminalise HIV transmission, expanding needle exchange programmes, and improving sexual health services (including opt-out testing) provided in prisons and immigration detention centres. | We will consider this recommendation as we move forward to implement the Action Plan in line with wider government policies. | ||

| Action 17 - Local authorities should each develop their own local plan on how they will contribute to the recommendations of the HIV Commission, to ensure the 2025 and 2030 goal is met. | There are other existing structures in place for HIV, including those places designated as Fast-Track Cities. In other [local authority] areas activity is led by Directors of Public Health and their teams. It is recommended that this existing infrastructure is developed to support implementation of this plan at a place-based level (for example, local authority, regional and emerging new structures) to review local epidemiology, understand existing practices, address gaps at a local level and share learnings. Regional work will be supported by UKHSA, NHSEI and OHID. | ||

| Action 18 - NHS England and local authorities, working with the Department of Health and Social Care and its agencies, should collaborate more closely on the commissioning of sexual health and HIV services; and ensure greater integration of services to ensure seamless, patient-centred care. | We will increase support to people living with HIV to increase the number of people retained in care and receiving effective treatment … OHID will review the current model sexual health service specification to strengthen pathways with other services, including drug and alcohol, domestic abuse and mental health services. This includes consideration of integrated services or collaborative commissioning. Regard must be given to those groups who may face additional barriers to access, such as migrants or those who are homeless or in insecure housing. The review of NHSEI’s service specification will look at the importance of services involving key communities and people living with HIV in the design and ongoing development of services | Commissioning more broadly will be addressed in the SRH Strategy for England | |

| Action 19 - Commissioners should work with local providers and community organisations to ensure better co-delivery between drug and alcohol services (including sensitivity to the specificity of chemsex), domestic violence, mental health and sexual health services. | We will increase support to people living with HIV to increase the number of people retained in care and receiving effective treatment … OHID will review the current model sexual health service specification to ensure that formalised and improved pathways with other services including drug and alcohol, domestic abuse, and mental health services are sufficiently prominent. This includes encouraging commissioners, where appropriate, to consider integrated services/joint commissioning as an approach. Consideration should be given to those groups who may face additional barriers to access, such as migrants or those who are homeless or in insecure housing. | Commissioning more broadly will be addressed in the SRH Strategy for England | |

| Action 20 - The Department of Health and Social Care should provide clarity on where commissioning and funding responsibilities for HIV mental health and peer support services sit, review funding and show leadership to improve service levels and user experience for people living with HIV. | We will increase support to people living with HIV to increase the number of people retained in care and receiving effective treatment … OHID will review the current model sexual health service specification to ensure that formalised and improved pathways with other services including drug and alcohol, domestic abuse, and mental health services are sufficiently prominent. This includes encouraging commissioners, where appropriate, to consider integrated services/joint commissioning as an approach. Consideration should be given to those groups who may face additional barriers to access, such as migrants or those who are homeless or in insecure housing. | Commissioning more broadly will be addressed in the SRH Strategy for England |

-

See Annex B - Background chapter to support the Action Plan towards ending HIV transmission, AIDS and HIV-related deaths in England, 2021 ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9

-

Brizzi F BP, Plummer MT, Kirwan P, Brown AE, Delpech VC, et al. Extending Bayesian back-calculation to estimate age and time specific HIV incidence. Lifetime Data Analysis. 2019;25(4):757-80 ↩ ↩2

-

CD4 cells, also known as T cells, are white blood cells that fight infection and play an important role in the immune system. Being diagnosed with HIV and having a CD4 count of less than 350 cells/mm³ is considered a late diagnosis of HIV. ↩

-

from 2019 baseline ↩

-

CD4 cells, also known as T cells, are white blood cells that fight infection and play an important role in the immune system. Being diagnosed with HIV and having a CD4 count of less than 350 cells/mm³ is considered a late diagnosis of HIV. ↩

-

Being diagnosed with HIV and having a CD4 count of less than 200 cells/mm³ (or certain indicator health conditions) would lead to a diagnosis of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS). With effective antiretroviral treatment, very few people in the UK develop serious HIV-related illnesses. ↩

-

Laboratory effectiveness is 99.5% ↩

-

Public Health England, ‘Trends in HIV testing, new diagnoses and people receiving HIV-related care in the United Kingdom: data to the end of December 2019’, Health Protection Report, v14n20, 3rd November 2020. ↩

-

A CD4 count of less than 350 cells/mm³ ↩

-

Trends in HIV testing, new diagnoses and people receiving HIV-related care in the United Kingdom: data to the end of December 2019 Health Protection Report Volume 14 Number 20 3 November 2020 ↩

-

Public Health England, ‘Trends in HIV testing, new diagnoses and people receiving HIV-related care in the United Kingdom: data to the end of December 2019’, Health Protection Report, v14n20, 3rd November 2020 ↩ ↩2

-

A diagnosed HIV prevalence rate of more than 2 people per 1,000 people is considered high, more than 5 per 1,000 people is considered very high ↩

-

A CD4 count of less than 350 cells/mm³ ↩

-

O’Halloran C, Sun S, Nash S, Brown A, Croxford S, Connor N, Sullivan AK, Delpech V, Gill ON. HIV in the United Kingdom: Towards Zero 2030. 2019 report. December 2019, Public Health England, London. ↩

-

Rodger AJ, Cambiano V, Bruun T, Vernazza P, Collins S, Degen O, et al (2019). ‘Risk of HIV transmission through condomless sex in serodifferent gay couples with the HIV-positive partner taking suppressive antiviral therapy (PARTNER): final results of a multicentre, prospective, observational study. The Lancet, 393(10189): 2428-38 ↩

-

Mother-to-child transmission ↩