The Sourcing Playbook (HTML)

Updated 25 February 2026

Foreword by Alex Chisholm

Delivering outstanding public services is a critical function of government.

The introduction of the Outsourcing Playbook in 2019 set out a series of simple guidelines and rules to achieve this by improving our decision making and how we deliver public services.

Through the publication of version two of the Playbook in June 2020, the playbook was rebranded as the ‘Sourcing Playbook’, and through continued updates we are committed to ensuring they are successfully embedded in everything we do.

The fourth update of the Sourcing Playbook continues to focus on the same key commercial principles and is focused on choosing the best model for delivering public services. The Sourcing Playbook now includes updates and renewed focus on themes where consultations with industry and contracting authorities identified updated content would prove most useful, including managing inflation.

The Cabinet Office has acted together with colleagues across the Civil Service to strengthen capability, provide additional support and hold projects to account through stronger governance frameworks and controls processes. More needs to be done but there are positive signs of progress.

Practical guidance to support delivery and drive improvement on the following key policies remains:

- Publication of Commercial/ procurement Pipelines

- Market Health and Capability Assessments

- Project Validation Reviews (PVR)

- Delivery Model Assessments (also known as ‘Make versus Buy assessments’)

- Should Cost Modelling and Estimating

- Requirement for Pilots

- Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)

- Risk Allocation

- Pricing and payment mechanisms

- Assessing the Economic and Financial Standing of Suppliers

- Resolution Planning

The updated Sourcing Playbook continues to emphasise that the delivery of public services is a collaborative endeavour involving colleagues from Commercial/ Procurement, Finance, Project Delivery, Policy and other professions. Embedding the Sourcing Playbook into our ways of working is a journey the whole of government must continue to walk together.

As Chief Operating Officer of the Civil Service I am delighted to support the Sourcing Playbook and its continued implementation.

Introduction – Right at the start

The original Outsourcing Playbook, and its subsequent iterations, were endorsed by Ministers, industry and senior civil servants as crucial steps to improve both our decision making and the quality of contracts we place with industry. Importantly, implementation activities continue at pace.

For this fourth iteration, we continue to focus on the 11 key policies to get projects right at the start. This applies whether we decide to outsource and deliver a service in partnership with the private and third sector, insource and use in‑house resources, or a mix of both. The Playbook supports a range of delivery models that should be carefully considered as part of a ‘mixed economy’ approach to service delivery.

We have continued our joint working with suppliers, including small businesses, voluntary and community sector organisations, and colleagues across central government to capture further best practice and lessons learnt. This feedback has driven how we have refined our approach and policies in this iteration of the playbook, focusing on key challenges for contracting authorities and suppliers, whilst maintaining focus on achieving better outcomes and greater value for money.

When we do decide to work with the market, including small businesses, voluntary and community sector organisations, we will build successful relationships to drive innovation and maximise social value. By following the guidance, rules and principles set out in this Playbook we can expect to:

- get more projects right from the start

- develop robust procurement strategies

- engage with healthy markets

- contract with suppliers that want to work with us

- be ready for the rare occasions when things go wrong

And in doing so, we will continue to build the trust between the government, suppliers and the public. Both suppliers and departments are encouraged to highlight if either party falls short of the expectations in the Supplier Code of Conduct or this Playbook which has been updated and refreshed as part of the most recent iteration of the Sourcing playbook.

The Sourcing Playbook is aimed at Commercial/Procurement, Finance,

Project Delivery, Policy, and any professionals across the public sector who are responsible for the planning and delivery of insourcing and outsourcing services. It sets out how we make sourcing decisions, and deliver public services in partnership with the private and third sectors.

What is new?

Version 4 of the Sourcing Playbook builds on previous iterations to provide refreshed and refined content on:

- TUPE

- Embedding Playbook Policies in Frameworks and Guidance for Call‑offs

- Making the Playbook more accessible to Local Government and Wider Public Sector colleagues

- Pipelines and the impact of bid delays

- Refreshed Supplier Code of Conduct

- Financial Viability Assessments

- How to deal with inflation, including Contract Indexation

Procurement Reform

The new rules that will be introduced as a result of the enactment of the Procurement Bill and its associated regulations (which is currently going through Parliament) will have implications for the policies set out within this Playbook for contracting authorities in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, and reserved procurements undertaken in Scotland. The details of these changes cannot be known until that process has completed (likely to be towards the end of 2023) but we have attempted here to highlight what effect the proposed rule changes may have. Please note that this is still subject to change. The Playbooks will be updated to reflect the new regulations in due course.

Contacts

For further information or to provide feedback on the Sourcing Playbook please contact the Markets, Sourcing and Suppliers team at markets-sourcing-suppliers@cabinetoffice.gov.uk

Playbook flow diagram

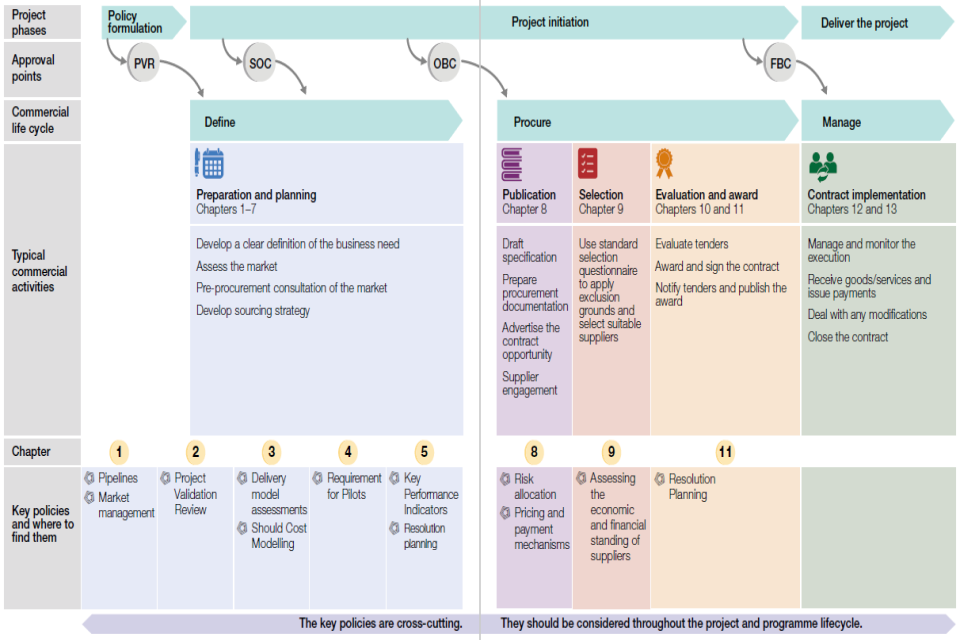

Figure 1: Where this Playbook fits within a typical procurement process

Summary of the 11 key policies

Publication of commercial / procurement pipelines

All central government departments shall publish their commercial pipelines.

This helps suppliers to understand the public sector’s long‑term demand for services and prepare themselves to respond to contract opportunities and allow the time and confidence to invest in innovative solutions.

Market health and capability assessments

All potential outsourcing projects shall conduct an assessment of the health and capability of the market early on during the preparation and planning stage. This will enable project teams to identify potential limitations in the market and consider whether actions such as contract disaggregation could increase competition and improve market health or whether better outcomes can be achieved through economies of scale.

Project Validation Review (PVR)

Previously only government major projects required a PVR assurance review.

Now, all complex outsourcing projects shall go through this important ‘policy to delivery’ gateway.

Brings together the full weight of functional expertise at the early stages of the project to help assure deliverability, affordability and value for money.

Delivery model assessments

(Previously known as the ‘make versus buy assessments’)

Central government departments should conduct a proportional delivery model assessment before deciding to outsource, insource or re‑procure a service.

They are mandatory in certain scenarios, as outlined on page 22.

This drives evidence‑based, analytical decisions and can help address the different challenges that come from outsourcing or insourcing a service, or one of its components.

Should Cost Modelling and Estimating

In central government, all complex outsourcing projects shall produce a Should Cost Model Estimate as part of the delivery model assessment.

Outside of central government, production of a Should Cost Model is considered best practice.

A Should Cost Model Estimate provides a better understanding of the costs associated with different service delivery models and helps to protect government from ‘low cost bid bias’.

Requirement for pilots

Where a service is being outsourced for the first time, a pilot should be run as part of a programme of testing.

Piloting a service delivery model is the best way to understand the environment, constraints, requirements, risks and opportunities relating to a procurement.

Pilots also provide a wealth of quality data and can help inform technical specifications.

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)

All new projects should include performance measures that are relevant and proportionate to the size and complexity of the contract.

In line with the government’s transparency agenda, three KPIs from each of the government’s most important contracts shall be made publicly available.

Getting this right will form the foundation of smarter contracts that are designed to incentivise delivery of the things that matter and provide clarity to the public about how the service is working for them.

Risk allocation

Proposals for risk allocation shall be subject to consideration and scrutiny to ensure they have been informed by genuine and meaningful market engagement.

Inappropriate risk allocation has been a perennial concern of suppliers looking to do business with the public sector and a more considered approach will make us a more attractive client to do business with and allow the public sector to achieve greater value for money.

Pricing and payment mechanisms

The pricing and payment mechanism approach goes hand in hand with risk allocation and should similarly be subject to greater consideration and scrutiny to ensure it incentivises the desired behaviours or outcomes.

This change is fundamental to making the outsourcing sector a thriving and dynamic market that is sustainable in the long term.

Assessing the economic and financial standing of suppliers

All outsourcing projects should comply with a minimum standard when assessing the risk of a supplier going out of business during the life of a contract.

Consistently applying a minimum standard of testing will provide a better understanding of financial risk and leave us better able to safeguard the delivery of public services.

Resolution planning

Suppliers of critical public service contracts shall be obliged by their contracts to provide resolution planning information. Although major insolvencies are infrequent, resolution planning information will help to ensure government is prepared for any risk to the continuity of critical public services posed by the insolvency of critical suppliers.

About this document

Key terms

- Outsourced service means any public service obtained by contract from an outside supplier.

- Outsourcing project refers to the project to outsource a service or any project considering an alteration to an existing delivery model.

- Complex outsourcing refers to any of the following: first generation outsourcing; significant transformation of service delivery; obtaining services from markets with limited competition or where government is the only customer; and any service obtained by contract that is considered novel or contentious.

- Department refers to any central government department or arm’s length body (ALB).

- ‘Contracting authority’ refers to any public sector organisation with a contractual relationship with a supplier. This could include, for example, a government department or local authority.

- Critical service contracts are contracts for outsourced services where significant disruption would occur should services be interrupted. These can be identified using the Cabinet Office Contract Tiering Tool, which considers factors such as the potential impact of service failure; service continuity; the speed and ease of switching suppliers; and the contract value.

- Critical suppliers are providers of critical service contracts. Critical suppliers are required to provide resolution planning information (see Chapter 11).

- Public sector dependent suppliers are supplier groups with over £50 million pa revenue of which over 50% is derived from public sector work. They may also be required to provide resolution planning information (see Chapter 11).

- Should, as defined in the government commercial functional standard, denotes a recommendation: an advisory element.

- Shall, as defined in the government commercial functional standard, denotes a requirement: a mandatory element to be implemented by departments and associated ALBs on a comply or explain basis.

What is the purpose of the Sourcing Playbook?

The Sourcing Playbook aims to provide commercial/procurement, legal, finance, project delivery, policy and other professionals with guidelines, rules and principles that will help them to avoid the most common errors observed in sourcing services, and get more projects right from the start.

The Sourcing Playbook describes what should or shall be done. How things should be done is described in a series of supporting guidance notes referenced out from this document. The refreshed guidance notes are:

- delivery model assessments

- bid evaluation

- Should Cost Modelling and Estimating

These complement the second addition Outsourcing Playbook guidance notes, which remain up to date and provide the latest guidance on:

- market management

- risk allocation and pricing approaches

- benefit measurement

- resolution planning

- testing and piloting services

- competitive dialogue and competitive procedure with negotiation

- assessing and monitoring the economic and financial standing of suppliers

- approvals

The standards that people should work to are specified within GovS 008 Commercial, GovS 002 Project Delivery and GovS 006 Finance respectively.

Who is the Sourcing Playbook for?

The Sourcing Playbook is aimed at commercial, finance, project delivery, policy and any professionals across the public sector who are responsible for the planning and delivery of insourcing and outsourcing services.

The Sourcing Playbook has been co‑developed with input from public officials and industry stakeholders, and is aimed primarily at central government departments and associated ALBs, who shall always apply the Playbook’s principles, guidelines and rules when considering service delivery. Nevertheless, the policies and principles are relevant to and should be considered by all public sector contracting authorities, who will need to apply judgment in adopting the Playbook based on the scale, scope, complexity, novelty and risk attached to their procurements.

Sourcing a service has in many cases been seen as an entirely commercially‑led enterprise. Experience has shown us that the delivery of a successful project whether in‑house, in partnership with the private and third sector, or a mix of the two requires appropriate cross‑functional expertise. It is expected that a number of the policies in this Playbook will be led by non‑commercial/procurement professionals. The key is ensuring we have joined‑up teams with the right functions inputting early into policy and projects.

Pipeline reviews can help to facilitate early planning and identify opportunities for more collaborative working.

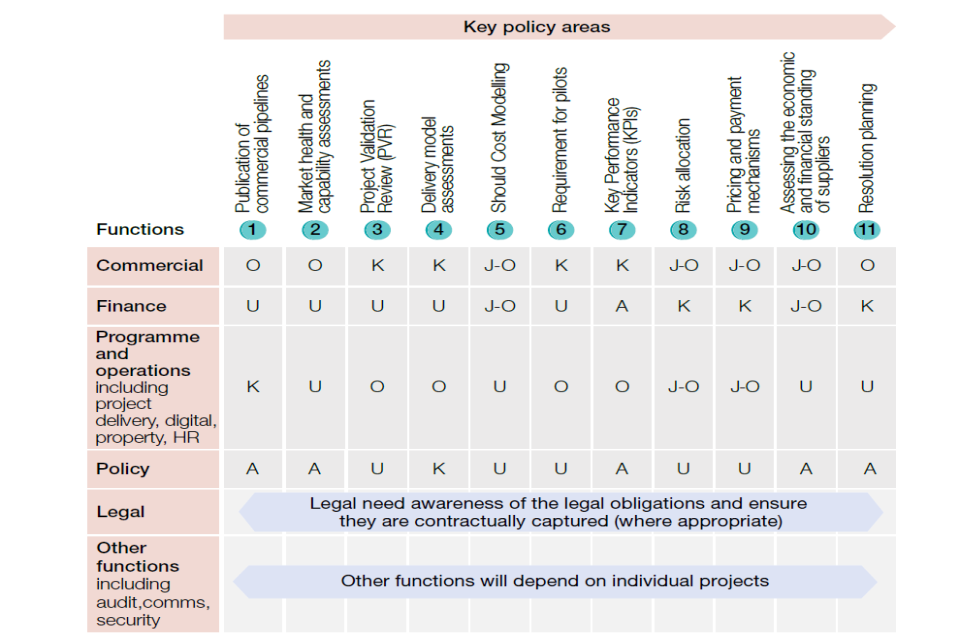

Figure 2 provides an analysis of the 11 key policies mapped against functional groups. This should be considered a guide to support department’s in implementing the Sourcing Playbook and may vary in different organisations depending on their structure.

Permanent secretaries, accounting officers, commercial directors, project sponsors and senior responsible owners will also find the guidance useful when acting as decision makers or approvers, or when conducting checks within the capacity of scrutiny and assurance. OKUA stands for:

- Ownership. Individuals within the function lead the activity and have overall responsibility for it.

- Knowledge. Individuals within the function are the subject matter experts on at least one element of the activity.

- Understanding. Individuals within the function understand what the activity is and what good looks like.

- Awareness. Individuals within the function know what activities are required and who is responsible.

Figure 2: Analysis of roles and responsibilities across the 11 key policies

What is the scope of the Sourcing Playbook?

The Sourcing Playbook shall always be applied by central government departments and ALBs when sourcing or contracting for services. All public sector contracting authorities should consider the Playbook’s guidelines, rules and principles, which can be considered good practice for any procurement.

Additionally, the Government Digital Service sets out in the service manual how to deliver IT and digital services. The DDaT Playbook provides guidance when sourcing and contracting for these digital services.

The Construction Playbook shall be considered when sourcing and contracting public works projects and programmes.

The Consultancy Playbook shall be considered when considering going to market for any consultancy services.

Framework agreements (and dynamic purchasing systems) for outsourced services are in‑scope of the Sourcing Playbook, and should be set up in accordance with the guidelines, rules and principles. Call‑off contracts from frameworks (and dynamic purchasing systems) need to be fully understood for complex outsourced services and the Crown Commercial Service can provide advice on whether a framework is suitable. Guidance on how the playbook policies apply to framework providers and contracting authorities.

This guidance details where there is responsibility for ensuring compliance with Playbook policies when a framework is being used to provide public services.

For setting up and managing government grants in central government, the Cabinet Office’s Grants Centre of Excellence provides expert advice.

The diagram in Table 1 summarises the key principles that apply to all services and the additional requirements that apply to complex outsourced services.

Compliance with the Sourcing Playbook for central government departments and associated ALBs is being assured through departments’ governance processes and central Cabinet Office controls (projects over £20 million total value). Where a supplier has any concerns about public procurement practice or compliance with government policy, the Public Procurement Review Service is available.

The Public Procurement Review Service (PDF, 115 kb) provides a clear, structured and direct route for suppliers to raise concerns anonymously about public procurement practice and provides feedback to enquirers on their concerns.

Table 1: Scope of the Sourcing Playbook

The Sourcing Playbook guidelines, rules and principles

All sourcing projects

- Are included in published departmental pipelines.

- Complete a market health and capability assessment.

- Conduct early market engagement

- Undertake a proportional delivery model assessment.

- Engage with end‑users, have clear aims and understand long‑term implications of decisions.

- Consider the value of running an initial pilot.

- Collect and maintain quality and data and allow subsequent validation of that data.

- Provide bidders with a clear articulation of the service in a well‑written technical specification.

- Design KPIs that are relevant and proportionate to the contract and make three of them publicly available.

- Conduct meaningful formal engagement of the market.

- Allocate risk to the party best able to manage it.

- Adopt a pricing and payment mechanism that complements the approach to risk transfer.

- Assess and monitor the economic and financial standing of bidders.

- Follow resolution planning guidance to help ensure continuity of critical public services.

- Plan early for what happens at the end of the contract.

- Ensure suppliers warrant data back to the contracting authority.

Complex outsourcing projects

- Go through a Project Validation Review (PVR) for central government. Outside of central government an independent peer review is considered best practice.

- Include embedded support from the Complex Transactions Team (CTT), or other Cabinet Office commercial team.

- Produce a Should Cost Model Estimate.

- Are subject to a pilot before full procurement.

- Consider the need for dialogue and negotiation.

- Apply low cost bid bias criteria.

1. Pipelines and market management

Getting it right starts by having clear and transparent commercial/procurement pipelines and a good understanding of the market.

Pipelines

One of the most important things we can do is prepare and maintain comprehensive pipelines of current and future government contracts and commercial/ procurement activity.

The expectation of commercial/procurement practitioners is set out in section 3.3 of the government commercial functional standard. Publishing commercial/procurement pipelines enables suppliers to understand the likely future demand across government. This is particularly important for Small and medium‑sized enterprises (SMEs), and Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprises (VCSEs) who may have fewer procurement resources. By sharing early insights on planned activities, we can attract a greater range of suppliers, creating more competitive pricing and greater value for money. Pipelines allow suppliers to forecast investment decisions they need to take in advance of demand. Suppliers will look across all the pipelines published by all their target clients to spot trends that might signpost emergent areas to focus on. Additionally, publishing pipelines can lead to greater innovation as the more notice that is given by the buyer, then the more likely it is that suppliers can start investing in relevant innovation ahead of the procurement coming to market in order to position themselves to win it.

Moreover, If suppliers know there are opportunities continuing into the future they will have confidence to invest in apprenticeship provision and other training, and in wider priorities specified in contracts, such as social value and building long‑term relationships with SME supply chains.

Suppliers understand that early‑stage pipelines are subject to change, However, the pipeline should be updated and enriched as the contracting authority moves through the business case and procurement process.

Published commercial/procurement pipelines should look ahead three to five years to be truly effective, but Central Government Departments must ensure their pipelines meet the minimum requirement of 18 months in length. At a minimum, pipelines should be updated every 6 months. However, contracting authorities should strive to update pipelines as frequently as possible to allow better signposting for any sudden and immediate work requirements.

Complex outsourcing projects can require at least this period in preparation and planning to get them right. Allowing insufficient time for commercial activities is frequently flagged by the National Audit Office (NAO) as an indicator of project failure.

Procurement Reform

The current intention under the Procurement Bill is that the requirement to publish information on governmental procurement pipelines will be expanded to all government bodies who expect to spend over £100million in a financial year for all contracts (exemptions apply, such private utilities and national security contracts) over £2million within 56 days of the start of the relevant financial year. It is envisaged that this information will be provided on a pipeline notice and be available on the single, central platform.

Market management

Healthy, competitive markets matter because they support our ability to achieve value for money for taxpayers and drive innovation in delivering public services.

Good market management is about looking beyond individual contracts and suppliers. It is about designing commercial strategies and contracts that promote healthy markets over the short, medium and long term.

First generation outsourcing decisions can have a profound effect on market development. For example, those winning early contracts may acquire first mover incumbency advantages, accepting that they also take on increased risk. We should adopt models that promote competition and contestability over time, so that those that win the initial contracts know that they must deliver value for money and perform to the standards required for the delivery of the service or risk contracting authorities taking their business elsewhere in future.

Mixed economies represent one way of broadening competition in a market and can therefore help drive value for money.

However, where mixed economies are used, care is required to create a level playing field between public, private and third sector providers. The expectation of commercial practitioners for managing markets is set out in section 5.1.3 of the government commercial functional standard.

All potential outsourcing projects should include an assessment of the market early on during the preparation and planning stage. These assessments should then be kept under review through the life of a contract. Where potential weaknesses are identified, consider whether actions such as contract disaggregation could increase competition and improve market health.

Guidance for how to do this is contained within the market management guidance note. Contracting authorities can also request access to supplementary market intelligence collected by commercial teams in the Cabinet Office and Crown Commercial Service (CCS). Advice can also be sought from the Competition and Market Authority (CMA) in relation to more complex or substantial competition issues.

Innovation and social value

Adopting innovative solutions and emerging technologies enables the government to improve our ways of working and achieve better public service outcomes. Innovation comes in a number of forms and starts with being open to new ways of thinking and creating forums where these ideas can be considered and assessed. Projects should engage in innovative thinking from the start through early dialogue with potential suppliers and understanding new technologies.

Projects should also consider research and innovation‑based procedures which go beyond market engagement into inviting the market to suggest novel solutions to problems.

Social value can promote innovation in the way contracts are delivered, through encouraging inclusive employment and supply chain practices, addressing skills gaps, promoting co‑design and community integration, and improving environmental sustainability. The public sector shall maximise social value effectively and comprehensively through its procurement and account for social value in the evaluation criteria. Furthermore, by valuing the social, economic and environmental benefits that the UK’s small businesses, voluntary, community and social enterprise organisations and responsible businesses can offer, we can contribute to further diversifying public supply chains. In central government and ALBs, the Social Value Model should be used to explore and identify social value opportunities during early engagement with supply markets and service users. It sets out government’s social value priorities for procurement across five key themes: COVID‑19 recovery, tackling economic inequality, fighting climate change, equal opportunity and wellbeing. Considering these key themes in our procurements will allow us to mitigate against the risk of modern slavery in our supply chains, contribute to our 2050 net zero commitment and further our wider ‘levelling up’ agenda.

Procurement Reform

The Procurement Bill requires that all contracting authorities have due regard to a set of national strategic priorities set out in a published National Procurement Policy Statement. The first version was published in PPN 05/21 and set out national priority actions for Social Value. It places emphasis on creating new businesses, new jobs and new skills; tackling climate change and reducing waste, and improving supplier diversity, innovation and resilience, all themes within the social value model.

Early engagement

We aren’t afraid to talk to the market. We do it regularly – recognising the benefits to both contracting authorities and suppliers. It can help promote forthcoming procurement opportunities and provide a forum to discuss delivery challenges and risks associated with the project. Through this process, we are able to understand the deliverability of our requirements, the feasibility of alternative options and whether there is appetite (within the market and the public sector) to consider innovative solutions that could help us deliver better public services.

Preliminary market engagement should actively seek out suppliers that can help to improve service delivery, including Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprises (VCSEs) who are experts in the needs of service users and widely involved in the delivery of public services across the country.

When carrying out early market engagement it is recommended that the proposed approach to inflation is clearly articulated.

This is especially important as this will directly impact risk allocation and pricing.

To enable inclusive economic growth that works for all, assessments of the market and pre‑market engagement should consider opportunities for wider social, economic and environmental ‘social value’ benefits to staff, supply chains and communities that can be achieved through the performance of the contract.

Early market engagement should also be used to inform the development of the delivery model assessment approach, testing and pilots, the potential procurement procedure, possible bid evaluation criteria, and overall project timetable to ensure that when going to the market, potential suppliers have sufficient time to respond to tenders.

Potential outsourcing and IT services are tested at the Strategic Outline Case (SOC) stage to ensure that engagement has been sufficiently early for suppliers to understand the requirement and for the contracting authority to reflect on any feedback received.

All preliminary market consultation shall observe the principles of public procurement and be handled in such a way that no supplier gains a preferential advantage.

In practice, this means not setting the technical specification to suit a particular bidder and making sure any information shared is also available during the tender procedure. It is good practice to openly announce any preliminary market consultation by publishing a Prior Information Notice (PIN) and early market engagement notice or future opportunity notice on Contracts Finder.

Procurement Reform

The principles around early engagement with the market ‑ to improve understanding of suppliers’ capabilities and risk appetite, and to identify new potential suppliers ‑ remain the same under the Procurement Bill. However, the introduction of the Preliminary Market Engagement Notice makes it clear that the assumption is that this market engagement will take place, with contracting authorities required to note any decision not to publish a PME notice within their Tender Notice. Contracting authorities will also be required to actively consider whether there are any barriers to small and medium sized enterprises bidding for a particular contract and assess how these can be overcome.

Transparency

Transparency and accountability of public service delivery data and information builds public trust and confidence in public services.

It enables citizens to see how taxpayers’ money is being spent and allows the performance of public services to be independently scrutinised. It also supports the functioning of competitive, innovative and open markets by providing all businesses with information about public sector purchasing and service providers’ performance.

Buyers should explain transparency requirements to potential suppliers as early as possible in the procurement process, and set out clearly in tender documentation the types of information to be disclosed on contract award and thereafter.

Procurement Reform

Transparency is a stated objective of the new regime and it is embedded by default throughout the Bill. With the new rules, the government is committed to increasing transparency within public procurement, for suppliers, buyers and the general public alike. This is intended to improve competition, widen the supplier base and to hold contracting authorities and suppliers to account for their actions and performance.

As a result, you will notice many changes to the required notices (and their names) as follows. Further detail on what information each notice must contain will be included within the detailed secondary legislation which is yet to be published:

- Pipeline Notice ‑ a contracting authority anticipating spending over £100million in the following financial year is statutorily obliged to publish a notice setting out all of its planned contracts over £2million within the next 18 months. This must be published within 56 days of the start of the financial year.

- Planned Procurement Notice ‑ this provides suppliers with advance notice that a contracting authority intends to run a competition and, like the current PIN, allows timescales to be reduced.

- PME Notice ‑ the preliminary market engagement notice is to be published before the Tender Notice and used by contracting authorities to provide information on upcoming or past preliminary market engagement.

- Tender Notice ‑ this notice invites suppliers to either submit a tender or a request to participate in a competitive procurement process.

- Transparency Notice ‑ a new notice requiring contracting authorities to inform the market and the public of their intention to direct award a contract (this isn’t applicable for user choice contracts).

- Assessment Summary ‑ this is provided to bidders at the end of a competitive process and will contain information about the winning bid and the assessment of the bid of the supplier who is receiving the summary. This will help suppliers improve their bids in future and increase the quality of the market

- Award Notice ‑ the Award Notice is notification that a contract is about to be entered into. It is required for competitive and non‑competitive contracts and will usually mark the start of an 8 working day standstill period before which the contract can not be entered into.

- Contract Change Notice ‑ a new notice which is to be published advertising the contracting authority’s intention to modify an existing contract.

- Contract Details Notice ‑ to be published within 30 days of the contract being entered into.

Key points

- Publish commercial/procurement pipelines so suppliers understand likely future demand for services across government.

- Assess the health and capability of the market you will be dealing with and consider how your commercial strategy and contract design can be adapted to address potential weaknesses.

- Consult widely and encourage broad participation, particularly with SMEs and VCSEs.

- Engage early with the market and be ready to demonstrate in your Strategic Outline Case (SOC) that your proposals have been informed by both your market health and capability assessment and feedback from potential suppliers.

- Consider how you will drive innovation and social value through the procurement.

Want to know more?

1. GovS008 Commercial Functional Standard.

2. Market management guidance note.

4. For civil servants, weekly newsletters on government strategic suppliers can be requested from marketsandsuppliers@cabinetoffice.gov.uk.

Supplier factsheets and market reports for common goods and services can be requested from ci@crowncommercial.gov.uk.

5. Advice from the CMA can be sought by contacting advocacy@cma.gov.uk.

6. Guidance on transparency and the publication of tender and contract documents.

7. Procurement Policy Note 02/17: Promoting Greater Transparency and in Procurement Policy Note 01/17: Update to Transparency Principles.

8. Commercial Pipeline Guidance.

9. Procurement Policy Note 05/21: National Procurement Policy Statement.

2. Approval process

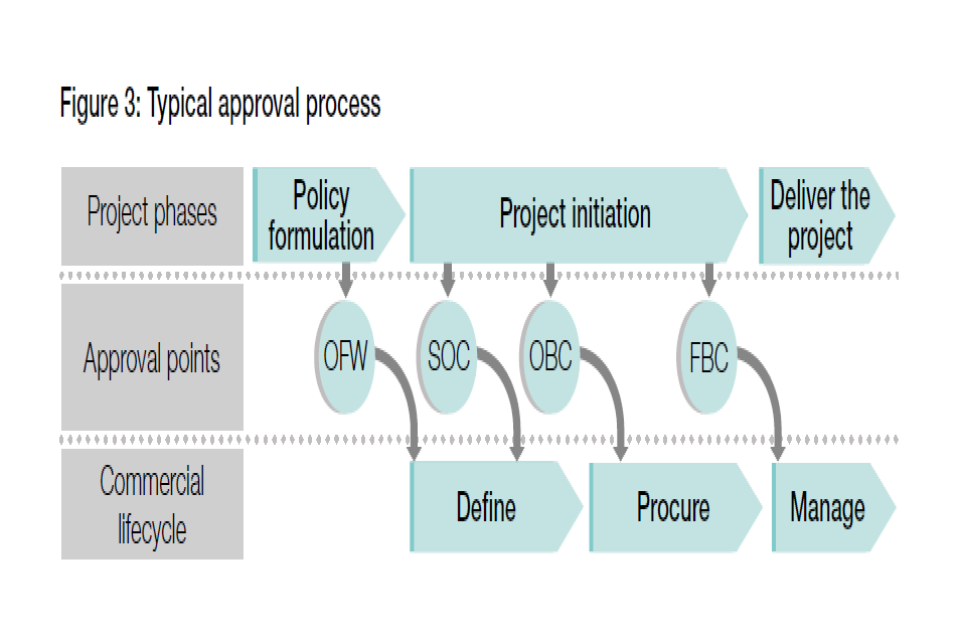

To ensure a smooth transition through the approval process, it is critical to engage early with assurance teams and processes.

Project Validation Reviews

Any new initiative that is likely to result in a major project, shall go through a Project Validation Review (PVR). This also now applies to all complex outsourcing projects.

If the value of a standard outsourcing project is greater than the departmental delegated expenditure limit or it is considered to be strategically significant, then a PVR may still be required. Departments should consult the Cabinet Office Commercial Continuous Improvement Team.

The PVR shall occur during the early stages of preparation and planning, and before any public commitment is made. It consists of independent peer reviews that take place ahead of the transition from policy to delivery. Further information can be found in the approvals guidance.

For all projects over £20 million (total contract value), additional controls are applied by the Cabinet Office. Departments are encouraged to engage with the Cabinet Office Commercial Continuous Improvement team (controls) as early as possible.

If the outsourcing project is considered to be complex, a member of the Complex Transactions Team, or another Cabinet Office team, should also be embedded.

At the Outline Business Case (OBC) stage, senior responsible owners should also have identified KPIs that align with and will support delivery of overarching project goals. These can then be further refined through piloting and market engagement (see later sections).

The benefit of applying the full weight of cross-government expertise to outsourcing projects is realised in the deliverability, affordability and value for money of the project. Getting all teams on the same page from day one puts us in a position to make good decisions, right from the start. The expectation of commercial practitioners is set out in section 3.4 of the government commercial functional standard.

The commercial conversation continues after the PVR and SOC. Departments are encouraged to make use of available resources and knowledge from across their own organisation, wider government and in the central commercial teams throughout the approval process.

Figure 3: Typical approval process

Key points

- All complex outsourcing projects shall go through a Project Validation Review (PVR).

- The benefit of applying the full weight of cross‑government expertise to outsourcing projects is realised in the deliverability, affordability and value for money of the project.

- Contracting authorities are encouraged to continue the commercial conversation through Outline Business Case (OBC) and Final Business Case (FBC) approval stages.

Want to know more?

1. A short ‘plain English’ guide to assessing business cases.

2. Approvals process guidance note.

3. For advice on engaging the HMT Spending Teams, contact your departmental approval and scrutiny lead.

4. If you have any questions regarding Cabinet Office controls, contact commercialcontinuousimprovement@cabinetoffice.gov.uk.

5. For central commercial support on a complex outsourcing project in central government, contact the Complex Transactions team: cttbusinessoperations@cabinetoffice.gov.uk.

6. Contact the Crown Commercial Service if you wish to procure common goods and services.

3. Delivery model assessments

A delivery model assessment can help address the different challenges that come from outsourcing or insourcing a service, or one of its components.

A delivery model assessment (formerly known as a ‘make versus buy assessment’) is an analytical, evidenced‑based approach to reach a recommendation on whether a contracting authority should deliver a service or part of a service in‑house, procure from the market or adopt a hybrid solution.

It is a strategic decision that should be given consideration with an appropriate level of attention and foresight. This should take place early enough to inform the Strategic Outline Case (SOC).

How the decision should be made

To determine which service delivery model offers best value for money, a detailed analysis of the costs and benefits of each option is required. This should include a comprehensive evaluation of the risks, and the possible consequences – economic, human and technological – of outsourcing, insourcing, and / or adopting a mixed economy approach. The Orange Book provides further detail on how to assess and manage risks.

Figure 4 provides a structured framework to assess these factors, consistent with the options appraisal approach prescribed in the Green Book. For complex projects, departments should consult the Cabinet Office before beginning the delivery model assessment for expert support and independent facilitation.

6 When is a delivery model assessment required?

Delivery model assessments are mandatory in the following scenarios and are generally good practice for all projects:

- Upon the introduction of new public services.

- Where the identification of a significant new development to an existing service (such as a new technology requirement) has been identified.

- Where there is a need to re‑evaluate the delivery model of existing services, for example because of deteriorating quality of delivery, a major policy or regulatory change, departmental cost reduction, technological advancement, significant change in strategic direction or transformation programmes.

Figure 4: Delivery model assessment approach

1. Frame the challenge

Clarify the programme objectives, timescales and drivers of change. Identify stakeholders and set up working teams and governance approach.

2. Define the service, delivery model options and data inputs

Identify the service components and the options for how they might be delivered, including how service components might be combined or disaggregated to best deliver the desired outcomes.

3. Establish strategic and operational evaluation criteria

There are many potential issues to consider in the selection of a delivery model. Evaluation criteria will be specific to each programme but the following areas give some examples of the potential key issues that might determine the most appropriate strategic approach for delivery and the relationships you will need to develop with the supply chain.

Strategy and policy

Consider how well the delivery model aligns with departmental and government strategies and policies. How will it ensure delivery of strategic objectives, such as SME engagement, equalities or social value?

Transition and mobilisation

Consider how easy it will be to transfer existing services into the new model.

If this is a new service, what challenges will you face setting up and mobilizing the service? Consider issues such as recruitment (or TUPE implications), timescales and systems developments.

People and assets

Consider the capabilities and skillsets needed and existing capacity (internal or in the external market). What flexibility will you need (e.g. if volumes change) and how well can the delivery option meet these needs? What will the training and recruitment impact be? What other investments may be required and who will own any assets (including intellectual property)?

Service delivery

Consider how the delivery model will guarantee ongoing service quality, innovation and continuous improvement. What management structures will be required, whether insourced or outsourced? How will you manage SLAs and KPIs?

Risk and impact profile

Identify the commercial and operational risks that may impact the delivery of services.

Who is best placed to manage these risks and how might they be mitigated by the delivery option?

4. Assess the whole life cost of the project

Use your strategic approach and service definition to identify the cost drivers for the transition and mobilisation phase and a period of running.

All projects should develop an appropriate Should Cost Model.

5./6. Conduct the evaluation and align the analysis

The cross-functional team should assess each of the evaluation criteria against the agreed weightings.

Learn from objective evidence, past projects and colleagues across the public and private sector (this may include engaging with the market) to test and sense-check your findings.

Consider a red team review to validate your findings.

7. Recommendations and approvals

Develop and document your recommendations and ensure approval via the project board.

8. Piloting and implementation

Build your commercial strategy and identify any requirements to pilot the outcome of your assessment (see guidance note).

The delivery model assessment should be proportional to the criticality, complexity and size of the project, and completed early in the preparation and planning stage in order to inform the development and recommendation of options in the SOC.

Delivery model assessments are expected to be iterated over time in‑line with the business case development process set out in the Green Book. The contracting authority should then reassess the delivery model assessment ahead of the Outline Business Case and ensure that any assumptions have been validated and factored into the Full Business Case.

The process to run a delivery model assessment is set out in detail in the additional Guidance Note.

Using Should Cost Model Estimates to understand whole life costs

Having a clear understanding of the whole life cost of delivering a service, and/or the cost of transforming a service is best achieved by producing a Should Cost Model Estimate.

As summarised below, a Should Cost Model Estimate can be used to help evaluate different delivery model options:

- In‑house – This is the whole life cost to deliver a service in‑house using internal resources and expertise. It includes the cost of acquiring assets and the necessary capability. This should be used early in the procurement to compare costs against the ‘expected market cost’ and / or ‘mixed economy’ options at a high level to inform your delivery model assessment.

- Expected Market Cost ‑ This is the expected whole life cost of procuring a service from an outside supplier. It includes the cost of additional market factors such as risk and profit. Use early market engagement to help ensure that the model structure can be evolved to enable comparison to the bids you expect to receive from the market.

- Mixed economy – A delivery model will often be a combination of insourcing and outsourcing different components of the service. In these cases, a combination of the ‘in‑house’ and ‘expected market cost’ options, referred to as a ‘mixed economy’ option, can be used to calculate the cost of the service.

It is good practice to produce a Should Cost Model Estimate for all procurements. Where a complex service is being considered, a Should Cost Model shall be produced.

Should Cost Model Estimates should be used early in the procurement process to:

- inform the delivery model assessment (initial Should Cost Model Estimates may be at high level)

- drive a better understanding of the financial risks and opportunities associated with different service delivery options and scenarios

- drive more realistic budgets by providing greater understanding of the impact of risk and uncertainty

- inform the first business case (SOC for departments and ALBs)

- inform engagement with bidders and the appropriate commercial strategy, including methods to incentivise the supply chain to deliver whole life value

Should Cost Model Estimates can be used throughout the procurement lifecycle and can help to support wider requirements, such as demonstrating value for money or helping to protect government from ‘low cost bid bias’. As requirements change and more information becomes available, for example, the anticipated costs linked to the proposed KPI targets, they will evolve and the level of detail, which can vary significantly, should be iteratively developed over time. Further information is available in the Should Cost Modelling guidance note and HM Treasury’s guidance on producing quality analysis for government.

Inflation and Indexation

It is essential that contracting authorities assess and manage the risk of inflation and look to implement an agreed approach at the pre‑procurement stage to maximise value for money. Using indexation is a transparent way of allowing calculations and reimbursements to be made in line with the underlying costs of a project. This will avoid suppliers pricing in an expensive risk premium due to the risk of inflation, resulting in poor value for money.

The starting point is understanding the cost drivers of a contract and developing a Should Cost Model Estimate will be central to this.

The contracting authority should consider the supplier’s ability to manage these costs, and only consider indexing costs that are outside the control of the supplier. The resulting contractual index should be the index that best represents the cost drivers subject to inflation. In services with several cost drivers, the contractual index may be a ‘composite index’ that is a weighted average of the individual indices of those specific cost drivers, weighted according to the proportion of their contribution to the total cost of the good or service.

Alternatively contracting authorities can apply indices to specific cost lines within their pricing schedule. Either of these approaches should be used to ensure that the impact the index has on a contract’s pricing is proportional to the contract’s exposure to the costs that the index is linked to. This contractual index will shield suppliers from costs outside their control and incentivise them to manage costs that they can control. Contracting authorities should use indices from published and reputable sources, such as the ONS, government departments and potentially other bodies aligned to specific commodities or industries.

Open Book Contract Management (OBCM) can complement the operation of a contractual index. It is a structured process for the sharing and management of charges and costs and operational and performance data between the supplier and the authority.

The use of OBCM, provided that it is proportionate to do so, will provide transparency that the chosen indexation approach is appropriate such that inflationary increases do not either unfairly penalise the supplier or enable them to make excessive profits.

When considering insourcing a service

Insourcing commonly refers to the process of transferring part or all of a service that was previously outsourced to an in‑house service delivery model. Insourcing is a substantial transformation in service delivery model, and should have additional care and consideration applied before being undertaken.

There are a number of specific considerations before insourcing a service including:

- ability to acquire or build and maintain the required expertise and assets

- impact of TUPE regulations and pension liabilities

- organisational governance, processes and capability, including senior management and backroom functions

- potential increase to risk exposure

- impact on market health and other public services

- interdependencies with other public services

- accessing required service information and intellectual property

Characteristics of services that may be particularly challenging to insource include where:

- there is a lack of required specialist capability internally (e.g. specific technical capabilities) or assets

- there is reliance on specific intellectual property that sits with a supplier (or number of suppliers)

- the market has scale that is driving greater efficiencies

- the market is continuously innovating and an in‑house solution may not have the scale or expertise to replicate that

- there is currently a lack of senior management capacity or capability to transition, integrate and manage the insourced services

When delivering a service in‑house

Delivering a service using internal resources and expertise should be based on the same robust expectations set out in the Playbook for outsourced services.

This includes setting and monitoring performance against clear objectives and outcomes managed by appropriately qualified individuals. This is set out in detail in the government’s project delivery standards.

To help achieve these standards, you should consult the following sections in the Playbook:

- Piloting the delivery of a service (see Chapter 4: Piloting delivery of a Service): Testing a service on a small scale before full‑scale implementation can provide organisations with valuable data on a service and / or test best practice approaches.

- Quality data and asset registers (see Preparing to go to market): We should be collecting and maintaining data about our assets and services to enable us to make informed decisions when we need to.

- KPIs and baselines (see Chapter 5: Preparing to go to market): Ongoing monitoring linked to intended benefits in a proportionate and appropriate way is essential for all public services.

Where similar services are insourced and outsourced by a contracting authority, comparable KPIs should be set to enable fair and consistent comparison of delivery models and service levels.

The Infrastructure and Projects Authority offers expertise in all aspects of project delivery including training, guidance and resources.

When considering outsourcing a service

Some services will carry more risk than others when outsourcing, for example, complex outsourcing services present the contracting authorities with more commercial, operational and reputational risk, not all of which can or should be transferred to the supplier (see risk allocation guidance note).

It can be more challenging to fully outsource services that have any of the following characteristics:

- are core to your organisation’s purpose and objectives

- are complex (as defined on page 13) or high‑risk services where there is limited or no proven market capability

- are novel services that have a limited market to source from

- have experienced many operational difficulties in the past

- are poorly understood and / or not well defined

- there will be disproportionate effort and cost to bring services back in‑house in future

TUPE

TUPE stands for the Transfer of Undertakings (Protection of Employment) Regulations 2006. TUPE can apply in instances where there is a requirement to outsource, reprocure or insource a service. Where TUPE applies, the employment of those employees doing work that is outsourced or insourced will transfer automatically by operation of law from their current employer to the new supplier (on an outsourcing or reprocurement) or to the Department or other public sector organisation (on an insourcing), if a number of conditions specified under TUPE are satisfied. Those employees who transfer under TUPE will do so on their pre‑existing contractual terms and conditions of employment, which generally cannot be changed by the new employer if the sole or principal reason for the change is the transfer itself.

Whether TUPE applies, and the protection it affords to employees where it does apply, can give rise to complex legal, commercial, HR, pensions and operational challenges, so obtaining specialist advice and support at the earliest opportunity is vital. TUPE is not discretionary and contracting authorities should strive wherever possible, to keep clear, accurate and detailed information on employee roles to ensure that if a TUPE action were to take place, there is a clear set of reliable data to inform the process. TUPE is particularly important for labour intensive contracts. It should be considered throughout the whole commercial lifecycle.

In particular, whether TUPE applies or not and the current quality and availability of the data should be considered in the early, planning phases of a procurement, re‑procurement or insourcing process. It can take significant time for data to be in a usable and reliable state for a tender.

There are many advantages to both buyers and suppliers of collating and updating TUPE information. For example, if bidders are not provided with accurate and appropriately detailed information, they may include risk pricing within their bids. This is because they cannot be confident that the information presented to them reflects the reality of the situation when the service goes live. Suppliers may add in initial costs to protect their bottom line. For example, in the event that TUPE costs are higher than the data provided by the authority at bid stage suggested. By providing accurate TUPE information, buyers will be able to limit supplier risk pricing. This means bidders can compete on the basis of their actual price for providing the goods or service and results in better value for money outcomes for the taxpayer.

Full and accurate TUPE information should be shared with bidders at the tender stage of the procurement phase. Buyers should note that updating TUPE information too late during the procurement process can be unhelpful to bidders as they may not have the time to amend their bid before it is due to be submitted. This is where tools, such as allowable assumptions, could be used to allow bidders to update their TUPE costs in light of new information, as detailed below.

Seek TUPE Guidance from Suitability Qualified People

TUPE is a highly complex and specialised area and requires a collaborative approach where, for example, commercial, legal, commercial finance, strategic finance and HR all may need to be involved. Consequently, you should seek advice from suitably qualified personnel as early as possible and before taking any action. In the first instance, departmental or equivalent internal specialists should be contacted. For central government departments and some other public bodies, the GLD Employment Group’s TUPE Hub can be contacted for additional support and expert advice in relation to complex or difficult matters. The TUPE Hub can be reached at: EmploymentGroupTupe@ Governmentlegal.gov.uk

Additional guidance on how to get high quality data from incumbent suppliers

It is important that bidders are provided with accurate and suitably detailed TUPE information to use in their bids. This enables a better transition of suppliers and will mitigate risks associated with risk pricing.

Commercial/procurement professionals should be aware of the exit provisions provided under the Model Services Contract (MSC) which should be consulted when considering appropriate TUPE related clauses when contracting.

Data should be entered into a template to aid in completion. An example template for TUPE information is provided under the Model Services Contract. However, buyers may need to tailor this information based on their individual contractual needs. Alternatively, suppliers will likely have their own templates for TUPE data to be entered into. Buyers could use early market engagement to test this and devise an appropriate template for TUPE data to be entered into and shared with the bidders at tender stage.

Exit provisions should be used in contracts to require the outgoing supplier to provide accurate and up to date information required for retendering. This will aid in the exit phase from contracts as the incumbent supplier is contractually bound to provide TUPE data in instances of a new supplier taking over the service. Buyers should ensure that contractual mechanisms or obligations do not prevent TUPE information from being shared with bidders. For example, if relevant TUPE data is covered by a confidentiality obligation. Further clauses relating to TUPE can be found in the Model Services Contract. In cases of first generation outsourcing, the contracting authority is solely responsible for the quality of the TUPE data and cannot rely on exit provisions within an existing contract.

GDPR should be always considered when contracting with suppliers, however, GDPR considerations should not prevent contracting authorities from sharing relevant and accurate TUPE information with suppliers and bidders. For example, TUPE data can be anonymised.

Mitigating Risk Pricing

Contracting authorities should consider using allowable assumptions to mitigate the risk of supplier’s risk pricing. These can be defined as assumptions which allow the Supplier to set out any identifiable risks and ensures that the contract price changes only if those risks materialise. When considering allowable assumptions, buyers should consult the Model Services Contract (MSC).

The Cabinet Office produces template contracts for use by contracting authorities during their procurements and one of these is the Model Services Contract. This document is a set of standard terms and conditions for service contracts which can be a useful reference in the context of TUPE. The MSC Section 6 (Allowable Assumptions) of

Schedule 15 (Charges and Invoicing) permits suppliers to submit a register of allowable assumptions. In relation to TUPE information, this allows suppliers to clearly outline the potential impact of inaccuracy in the TUPE data and a defined period of verification.

Section 6 also clearly outlines the process for assessment and implementation of allowable assumptions if they occur, including ensuring that any allowable assumption which is exceeded is subject to the change control procedure. This enables contracting authorities to have a clear view of any assumptions around TUPE inaccuracy and to financially assess TUPE data impact within their financial model more accurately. It also enables suppliers to manage risk transparently with the authority, and ensures that any material inaccuracies are subject to the same requirements as any change within the contract terms. Lastly, the allowable assumptions mechanism is already integrated within the Model Services Contract, ensuring that the obligations and rights of contracting authorities and suppliers operate without conflict.

Another way to manage the risk of suppliers risk pricing is to include a specific TUPE true up mechanism as part of the procurement, whereby actual TUPE data is assessed against that provided during the procurement. This is not recommended policy in most cases. But if contracting authorities wish to include a true‑up mechanism, it is key that they take legal advice to ensure that the TUPE true up approach properly integrates into the contract mechanisms, obligations and rights, reducing the risk of a conflict in terms.

Asset Condition Handover

Additionally, commercial professionals should ensure that accurate asset data is available to bidders during the procurement process. The principles set out above in relation to TUPE data apply to asset data also. Contracting authorities should provide accurate data to bidders to avoid them risk pricing and provide means to update data should it be found to be inaccurate.

Key points

- The delivery model assessment should take place early in the preparation and planning stage of an outsourcing project before the Strategic Outline Case.

- Conduct a thorough analysis of value for money to determine whether services are best delivered ‘in‑house’, with the support of an outsourcer or through a mixed model.

- All complex outsourcing projects shall produce a Should Cost Model Estimate.

- Put in place the right resources and engage with key stakeholders to fully understand the environment, constraints, requirements, risks and opportunities.

- Consider the additional challenges on insourcing a previously outsourced service and the expectations when delivering a service ‘in‑house’.

Want to know more?

- The Green Book: appraisal and evaluation in central government.

- Review of quality assurance of government models.

- The Aqua Book: guidance on producing quality analysis for government.

- Market management guidance note.

- Delivery model assessment guidance note.

- Should Cost Model Estimating guidance note.

- For central commercial support on a complex outsourcing project, contact the Complex Transactions team: cttbusinessoperations@cabinetoffice.gov.uk.

- For advice on potential commercial models for your service, contact the Commercial Models team: commercialmodels@cabinetoffice.gov.uk.

4. Piloting first generation outsourcing

When we choose to outsource something for the first time, we treat it as a special case and apply additional scrutiny and assurance.

Piloting delivery of a service

Where government is outsourcing a service for the first time, a pilot should be run first as part of a robust programme of testing, in recognition of the inherent uncertainty of first‑generation outsourcing, before deciding on a long‑term delivery model. We will take a pragmatic approach to this presumption and exemptions can be agreed where it isn’t practical or beneficial to run a pilot.

Options for running pilots

Across the public sector, the concept of ‘piloting’ new services has come to mean many different things. We recognise that pilots are only one form of a range of testing approaches which provide insight and evidence into what works. Other methods of testing include:

- Trial programmes and proofs of concept: The theoretical or live testing of policies or processes to check that they will deliver their intended outcomes.

- Scoping phases, agile approach and innovation partnerships: Processes that help to develop and build the final requirements using structured, iterative ways of working. These may involve theoretical testing or take place in a live environment.

- Test and learns: The testing of one or more delivery options to identify which will best achieve the objectives.

- Pilots: The final stages of testing a preferred option usually on a small scale to ensure that all the ‘rough edges’ and logistical issues can be addressed before a full‑scale rollout.

In many instances it will be appropriate for contracting authorities to use one or more testing approaches at earlier stages of project development, with the pilot being the final testing stage prior to a full‑scale rollout of services. The testing and piloting services guidance note sets out when certain tests may be more appropriate in a project lifecycle.

Early testing enables contracting authorities to understand the viability of a project or outcome at its various stages of development. This allows the contracting authority the opportunity to change the course of action, limiting cost and time where it becomes apparent that the project will not deliver the required outcome. Tests can also be used to explore new technologies and delivery innovations for services that are already outsourced.

When to test and pilot

Not all testing approaches will be required for every project. Testing approaches should be proportionate to the size, complexity and level of uncertainty in delivering a service.

Planning which testing approaches to include and whether to include a pilot should begin at the earliest strategic stages of a project, before the start of any procurement process, and should be incorporated into the delivery model assessment, sourcing strategy, bid documents and evaluation processes.

Ensure you communicate the likelihood that a pilot phase will be used through early market engagement to seek feedback from the market to inform the procurement.

The testing programme should align to key project milestones throughout the lifecycle of the project up to full implementation.

Designing effective tests and pilots

Tests, including pilots, should be developed to ensure success and the most value is obtained to mitigate potential risks prior to scaled implementation. There are a number of factors to take into consideration in designing effective tests and pilots, and detailed guidance is provided in the testing and piloting services guidance note.

Key considerations include:

- set clear, measurable objectives and success criteria

- identify the scope and scale of what will be tested, and where they will be run

- put in place the right resources

- establish clear timescales and embed these in the overall project plan

- ensure the right commercial mechanisms are in place

- allow sufficient time at the end of tests for due consideration of the results

Procurement Reform

The Bill does not change the policy on testing and piloting but the new Competitive Flexible Procedure will provide greater flexibility for contracting authorities to design procedures which use testing and piloting as formal parts of the procurement and to set out clear rules in advance about how the results of any pilots will be used and down‑select decisions made.

Key points

- Services that are being outsourced for the first time that are considered complex should be subject to a pilot before advancing to full procurement.

- Pilots may also be helpful where an outsourced service is undergoing a transformation, where there is poor competition in the market and / or to test new technology or innovation.

- Pilots are one form of test, and other testing approaches should also be considered as part of a robust testing programme.

Want to know more?

- Testing and piloting guidance note.

- The Magenta Book: Guidance for evaluation.

5. Preparing to go to market

Preparation is the key to achieving flexible and efficient procurement processes that encourage broad participation and are open and accessible to all.

Publication

Make use of the options available to publicise your early engagement activity. This can be done via a Prior Information Notice on Find a Tender Service (FTS), or a future opportunity or early engagement notice on Contracts Finder, as appropriate.

If calling off a framework, Crown Commercial Service can support early engagement activity.

Ensure that legal and policy requirements for advertising your procurement are met. This includes the publication of the tender documents.

Procurement Reform

Under the future regime, contracting authorities will be able to publicise new opportunities and engage with the market through a Planned Procurement Notice or a Preliminary Market Engagement Notice (or both).

Quality data and asset registers

We should be collecting and maintaining sufficient data and information about our assets and services to enable us to make informed decisions when we need to.

This includes early delivery model assessments; those that shape commercial strategies; decisions that promote market health; and designing fair contracts and making good deals. All of these depend on the quality of information and data.

Suppliers are dependent on us having good data. The only way they can assess whether the delivery model and pricing structure that we take to market is deliverable and sustainable is if it is based on quality data.

We are committed to providing accurate data and / or building in flexibility to allow for subsequent validation of data (consistent with procurement legislation), particularly with first generation contracts, and expect pilots to be used to generate this information.

Where we are carrying out second (or subsequent) generation procurements, we rely on data provided by the incumbent.

Good contract management throughout the life of the contract is essential to ensure that the incumbent consistently provides and updates this information.

It is only once we have these elements in place that we can engage the market in a fair and open way and provide sufficient information for bidders to make an informed decision about whether they want to bid.

Clear specifications

A precursor to fair and open market engagement is a clear technical specification, which shall provide sufficient information for bidders to make an informed decision about whether they want to bid.

Without this shared understanding, we cannot expect to be able to relate the price offered by bidders to our own understanding of costs. And if we cannot do that, then we will always be open to risk that we will not get the outcomes we want at the price we need.

Contracting authorities shall ensure compliance with the Equality Act 2010 and its associated Public Sector Equality Duty. This should include consideration of the end‑user early in the preparation and planning stage of procurement to ensure the service being specified is fit‑for‑purpose and promotes equality of opportunity in a way that is consistent with the government’s value for money policy and relevant public procurement law.

KPIs and baselines

KPIs stands for key performance indicators, a measure of performance for a specific objective. Appropriate specifications and performance measures are the foundation of a good contract. With the right KPIs in place, it should follow that contracts are designed to incentivise delivery of the things that matter, to minimise perverse or unintended incentives and to promote good relationships.

In preparing to go to market, contracting authorities should develop a robust set of well‑structured KPIs that are relevant and proportionate to the size and complexity of the contract. Getting this wrong can create confusion and tension. For instance, having too many KPIs (i.e. more than 10 to 15 per service) will lead to overcomplicated contracts and ambiguity with suppliers. KPIs should also be set to align with the intended benefits to be realised during contract delivery (e.g. working within cost thresholds; achieving minimum performance outputs; and / or maintaining a minimum level of customer satisfaction).

Misunderstandings about how KPIs work or how they are measured can make it difficult for bidders to price them, and can result in unintended outcomes and / or service failures. It is important to work closely with your bidders and suppliers to ensure KPIs are jointly shaped and understood.

In line with the government’s transparency agenda, four KPIs from each of the government’s most important contracts shall be made publicly available.

This includes, but is not limited to, services contracts. These should be the three most relevant to demonstrating whether the contract is delivering its objectives and one social value KPI, and they should be measured regularly.

A specific review of the benefits being realised during contract delivery should be initially done at the 12‑month stage of a contract, and every 12 months thereafter on a ‘comply or explain’ basis. A sample of projects are routinely checked by central approvals and scrutiny. KPIs should also be developed to align with the project’s broader social value outcomes to help ensure that identified social, economic and environmental benefits are delivered through the contract. (For specific guidance on social value KPIs, see Guide to using the Social Value Model, section 4 (PDF, 279 kb).)

Procurement Reform

The Bill states that all contracting authorities (i.e. including local authorities) will be required to publish 3 KPIs and associated performance annually on all contracts with a value, or expected value, over £5million. (This will not apply to overarching frameworks, private utilities, concession contracts and those covered by Light Touch rules.) The plan is that this will be published on the single, central platform. The focus on setting appropriate KPIs and properly monitoring and recording performance will intensify because the performance data could grant contracting authorities discretionary rights to exclude suppliers who are perennial poor performers and have not responded to calls to improve.

Designing evaluation criteria and avoiding a bias towards low cost bids

To help avoid a bias towards low cost bids, the following should be considered when designing evaluation criteria:

- Pre‑market engagement to test that suppliers can deliver the required services at an affordable cost.

- A ‘Should Cost Model’ has been developed to help understand what the right cost (or cost‑range) is and what financial elements should form the whole life cost calculation.

- The approach to evaluating quality, including objective criteria that are relevant to the service requirement, weightings applied according to the importance of the criteria and a scoring approach that promotes effective differentiation.

The evaluation model should be developed iteratively by refining versions over time, with outline evaluation criteria tested with potential bidders as part of early market engagement. See the bid evaluation guidance note for further information.

Resolution planning

Standard clauses dealing with resolution planning should be included in draft contracts.

Where we are procuring a critical service contract, we will want the successful bidder to provide us with resolution planning information during the life of the contract and should make this clear in the contract notice.

More information on resolution planning can be found on pages 68 to 71.

Protecting against supply chain risk

The Model Services Contract (MSC) includes various protections against supply chain risk.

These include step‑in rights, the approval of key sub‑contractors and assignment and novation provisions.